Implicit leadership theories and followership informs understanding of doctors’ professional identity formation: A new model

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2017, 2(2), 18-23

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-2/OA1022

Judy McKimm, Claire Vogan & Hester Mannion

Swansea University Medical School, Swansea University, United Kingdom

Abstract

Aims: The process of becoming a professional is a lifelong, constantly mediated journey. Professionals work hard to maintain their professional and social identities which are enmeshed in strongly held beliefs relating to ‘selfhood’. The idea of implicit leadership theories (ILT) can be applied to professional identity formation (PIF) and development, including self-efficacy. Recent literature on followership suggests that leaders and followers co-create a dynamic relationship and we suggest this occurs commonly in the clinical setting. The aim of this paper is to describe a new model which utilises ILT and followership theory to inform our understanding of doctors’ PIF.

Methods: Following a literature review, we applied the core concepts of ILT and followership theories to theories underlying PIF by developing a mapping framework. We identified core themes, similarities and differences between the three perspectives and constructed a new model of PIF incorporating elements from ILT and followership. The model can be used to explain and inform understanding of medical practice and leadership situations.

Conclusion: The model offers insight into how concepts such as self-efficacy, prototypicality, implicit theories of self, power, authority and control and cultural competence result in PIF. Bringing together the theoretical frameworks of ILT and followership theory with PIF theories helps us understand and explain the unique dynamic of the clinical environment in a new light; prompting new ways of thinking about teams, interprofessional working, leadership and social identity in medicine. It also offers the potential for new ways of teaching, curriculum design, learning and assessment.

Keywords: Followership; Leadership; Professional Identity; Self Efficacy

Practice Highlights

- Doctors have a deep rooted professional and social identity that is closely connected with notions of leadership.

- New insight into professional identity formation can be achieved by applying the theoretical frameworks of implicit leadership theories, followership, and self efficacy.

- A better understanding of professional identity formation could potentiate new ways of approaching medical education and curriculum design.

I. INTRODUCTION

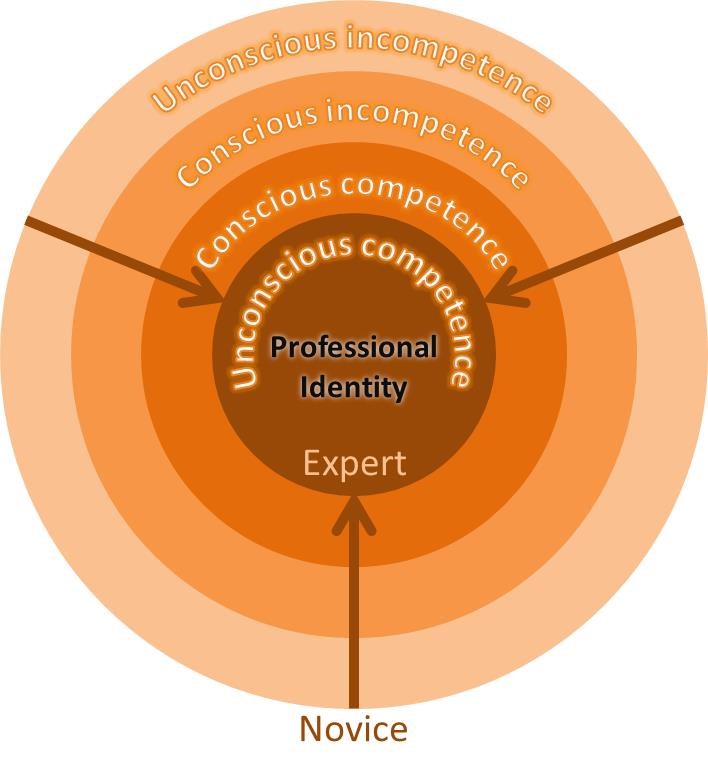

Doctors’ professional identity formation (PIF) is informed by many factors in the professional environment and is also inextricably linked to social status and personal identity. The professional identity of a doctor is a personal one before it is a group one. The emphasis on personal career progression, competition with peer group and relative autonomy in senior positions starts at medical school, this risks a prevailing attitude amongst physicians that they are ‘lone healers’ (Lee, 2010), causing inevitable problems with team-working. An understanding of how professional identity formation comes about is vital to an understanding of how doctors function in leadership, followership and team-working roles. Our model aligns this for practical developmental purposes with the ‘inbound trajectory’ adapted from the ‘novice to expert model of professional competence’ (Flower, 1999) (see Fig 1).

This model identifies that professional competence develops over time with feedback and reflection. Individuals become part of a ‘community of practice’ as they move along an ‘inbound trajectory’ towards being ‘expert’ (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015). In terms of professional identity formation in ‘becoming a doctor’, a ‘novice’ would not be really aware of the ‘reality’ of medicine, what being a doctor is about or how medicine is positioned vis a vis other professionals. Gradually, through trial and error, observation, conversations and ‘heat experiences’ (significant learning events)(Petrie, 2014), a more rounded and mature professional identity develops so that by the time the doctor is seen as ‘expert’ by others, they also see themselves as proficient, competent professionals distinct from other health workers. The following sections discuss followership theory; implicit leadership theory and implicit theories of the self and conclude by offering suggestions as to how our integrated model of professional identity formation can be used to develop doctors’ leadership, followership and team working skills.

Figure 1. Development of professional identity: A diagrammatic representation of desired inbound trajectory along the ‘novice to expert model of professional competence’ (Flower, 1999).

Figure 1. Development of professional identity: A diagrammatic representation of desired inbound trajectory along the ‘novice to expert model of professional competence’ (Flower, 1999).

II. FOLLOWERSHIP THEORY

Followership theory provides a much needed alternative perspective in a world of leadership-centric models. Leadership, management and followership form an interlinked triad of activities (Till & McKimm, 2016). A consideration of followership informs our understanding of leadership by describing the influence that followers have on their leaders and the process of ‘co-creation’ that occurs as a result of the impact that followers have on leaders and leadership styles (Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe & Carsten, 2014). In leadership-centric thinking, followers are often described in terms of subordination or even derogation. Followership thinking, by contrast, highlights the importance of followership behaviour in facilitating and forming leadership. Followership describes individuals who are more than just those who are ‘not-leading’ or ‘not-leading right now’. Followership practice varies as much as leadership practice, ranging from star-followers who represent an engaged and dynamic influence to those who make effort to be obstructive to team progress and challenge leaders’ authority. Followers can therefore have positive or negative powerful impact on the direction of a team and leadership efficacy. The identity of ‘leader’ and ‘follower’ must be considered fluid, all followers lead and all leaders follow in different contexts.

Doctors who follow are often seen (and see themselves) as ‘leaders in waiting’, ready to move along the ‘inbound trajectory’ by engaging in ‘small ‘l’’ activities (Bohmer, 2012) and moving up the medical hierarchy. Medical schools encourage students to compete with one another, to stand out and win prizes. This continues in the working environment where recognition and reward is for those who can show their personal contribution to service provision and improvement. As a result, it becomes culturally acceptable and desirable to aspire to leadership roles and to place personal career progression over team success, this has profound implications for team working in health services. Real team working in UK hospitals has been described as no more than an ‘illusion’ (West & Lyubovnikova, 2013), with groups of people working in ‘pseudo-teams’. Effective team work requires clear, defined and shared goals, when there is no meaningful team dynamic, quality of patient care must suffer. Although many Medical Councils highlight the importance of team-working in their professional standards, the notion of aspiring to outstanding followership is countercultural in medicine, partly because it is potentially threatening to professional identity.

III. IMPLICIT LEADERSHIP SOCIAL IDENTITY THEORY

One follower-centric approach encompasses the Implicit Leadership Theories (ILTs), which state that followers hold pre-conceived beliefs (almost stereotypes) about what makes a good or a bad leader. The ILTs are often based on a range of generic characteristics (such as height, gender, ethnic or professional background) and played out in practice through unconscious biases. Given the central role that followers play in creating and facilitating leadership, those leaders whose ‘faces don’t fit’ (for whatever reason) may have a difficulty persuading their followership to follow. Those who do not fit the pre-conceived implicit criteria may have to work much harder to gain the trust of a followership, this is regardless of the leader’s expertise and ability to lead. A followership of doctors has deep-seated pre-conceived beliefs about what their clinical leaders should look like. On an individual level these are created by past experiences and personal needs, on a group level these are created by professional culture, which, in turn, creates and is created by professional identity. Celebrated leaders in the world of medicine are usually those who are clinically excellent or high flying researchers, and who have personal charisma (the stereotypical ‘hero leader’), not necessarily those who display exceptional leadership, management and followership qualities in an everyday context. This may be because of the centrality of clinical ability in the professional and personal identity of doctors and may also help explain the relative reluctance of many doctors to move to the ‘dark side’ of healthcare management.

Social identity theory describes followers who identify closely with a leader as ‘high-identifiers’, the extent to which the leader represents the group they lead is referred to as their ‘prototypicality’.

Doctors, who commonly have aspirations to lead, are likely to be ‘high-identifiers’, closely identifying with the leader and the rest of the group, both socially and professionally. High-identifiers are more likely to be affected by group level behaviour but also have high expectations of procedural fairness in their leader and are more likely to be openly critical of leadership decisions. Prototypicality is also very important in clinical leadership, as doctors who follow identify closely with their leaders, they also expect them to look and sound like them, and most importantly they expect them to maintain a successful clinical role. Leaders in health services who do not have a clinical role are often viewed by doctors as an ‘out-group’, a good example of this might be non-clinical managers who are frequently mistrusted and blamed for health service failings. Problems may also arise in multi-disciplinary team settings where doctors, nurses and allied health professionals are required to work closely together. Doctors in this context may struggle to take leadership initiatives from those who are not doctors, however appropriate it is for that person to lead and how ever well qualified they are to do so (Barrow, McKimm & Gasquoine, 2011). Doctors who lead with the full support of their followership may not, therefore, be the most appropriate or able to lead, as their leadership expertise and ability is rarely that which is under scrutiny, rather it is their prototypicality that ensures loyalty. From this perspective, professional identity formation is therefore tied very closely to identifying with prototypical doctors and learning how to be like them. Whilst it can be helpful for individuals who ‘fit’, it can perpetuate a ‘people like us’ mentality and reluctance to welcome people seen as part of an ‘out-group’ into the profession (McKimm & Wilkinson, 2015) or into teams, which runs counter to inclusive leadership and celebration of diverse communities of practice.

IV. IMPLICIT THEORIES OF THE SELF AND SELF-EFFICACY

Implicit theories of the self-relate to domain specific ideas about identity and ability (Molden & Dweck, 2006). This framework divides people into two groups: ‘entity’ theorists who see their professional or social identity as rigid and fixed, and ‘incremental’ theorists who view their professional or social identity as malleable and developmental. In the clinical environment, doctors who hold entity theories regarding their professional identity are likely to find challenges to their professional identity difficult to manage. Such challenges may come in the form of non-doctors taking leadership roles, making a mistake or having a poor clinical outcome. Conversely, a doctor who holds incremental theories regarding professional identity is more likely to embrace and engage with challenges to preconceived identities, whether that is with new ways of working or in looking critically at long established systems. The question of whether doctors are more likely to be entity or incremental theorists in their professional lives is important. The study and practice of medicine can be lucrative and rewarding, but the lengthy training is rigid and prescriptive in many ways. It is reasonable to suggest that there may by a higher percentage of entity theorists amongst doctors than in other professions, not least because of the solid professional and social identity that it conveys. How fixed or fluid a follower feels about their own professional identity will directly impact how fixed or fluid they might feel about their leader, those who hold entity theories about their own professional identity are more likely to have a fixed idea about whether their leaders are fit for the job with little tolerance of those that do not meet their expectations. They are also likely not to appreciate the fluid nature of followership and leadership, with certain ‘types’ being deemed appropriate for simply one or the other.

‘Self-efficacy’ is a domain specific description of self-esteem (which can be understood as global) (Burnette, Pollack & Hoyt, 2010), high self-efficacy in the professional environment implies high professional self-confidence. For doctors with entity theories, high or low self-efficacy will impact their response to their own failings in the clinical environment. For example, those with inflexible entity theories and high self-efficacy (or high professional self-esteem) are likely to view mistakes as somebody else’s fault, alternatively, a doctor with low self-efficacy will be badly affected and possibly debilitated by a mistake. An incremental theorist is more likely to turn their attention to the detail of mistakes made, address them head on without fear and change future practice in light of them. Self-efficacy also effects desired protoypicality. If a doctor has low professional self-efficacy, they will desire leaders who do not look like them, those with high self-efficacy will be a high-identifier and the more prototypical the leader, the more effective they will be perceived to be.

V. AN INTEGRATED MODEL OF PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY FORMATION

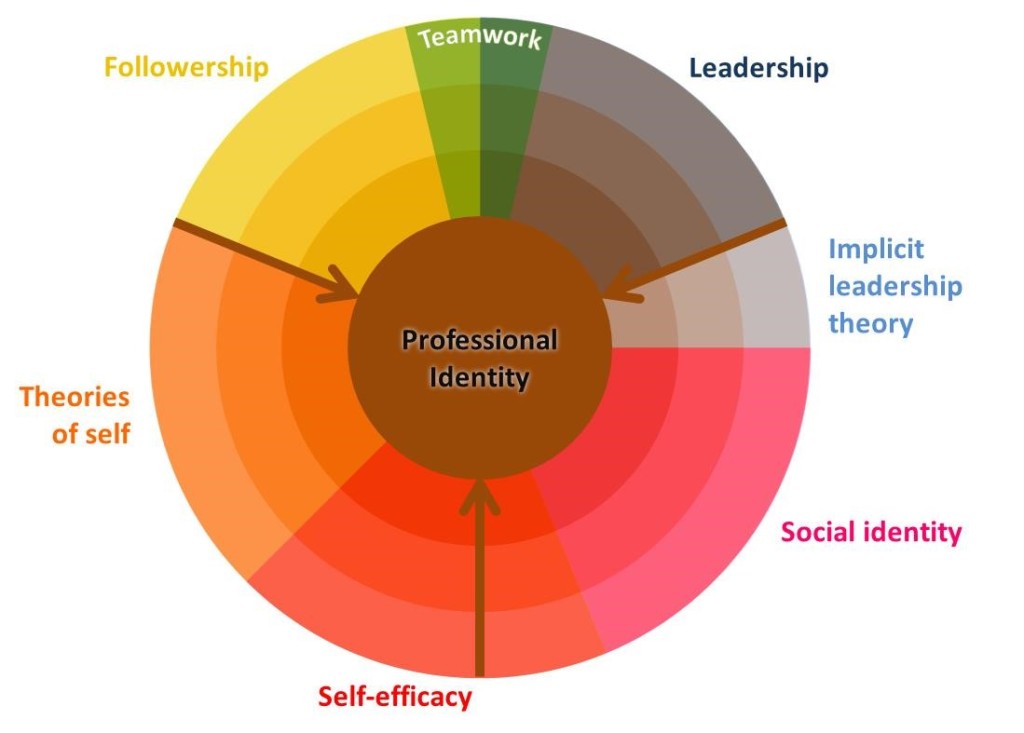

So, how do these theories help our understanding of doctors’ professional identity formation in terms of their leadership, followership and team working approaches and skills? The model (Fig 2) maps the theoretical domains discussed in this paper onto the ‘novice to expert model’ which we suggest can be aligned with ‘becoming a doctor’. We have discussed how engagement in a range of activities can help doctors move along the inbound trajectory towards expertise. Such expertise has at its centre a professional identity which is fully aligned with social and self-identity, underpinned by accurate understanding of self-efficacy. These ‘experts’ belong firmly in their community of practice, however that is defined. We suggest also that an explicit focus on specific development activities, underpinned by the theories discussed here, will help develop doctors to function more effectively in multi-cultural and diverse health services and in interprofessional teams. An example of this in undergraduate training would be to give medical students opportunities to work with nursing students early on, this would help both groups to better understand each other and ‘normalize’ interprofessional teamwork at a formative stage.

Specifically, the model provides a framework for educators, supervisors and individuals to plan activities and development opportunities in three key areas of activity: leadership, followership and team working to support students and doctors to become ‘expert professionals’. Whilst some of the techniques are similar to that used in coaching, education or mentoring, the theoretical perspectives described here integrate the literature on team working, followership, leadership, (including implicit leadership theories), theories of self (including self-efficacy) and social and professional identity theory in a unique way. For example, when working with students and doctors in groups and teams (in real or simulated environments), teachers could set activities aimed towards developing shared team goals, ensuring leadership happens and the outcomes are effective. As part of the process, teachers should make explicit reference to and facilitate discussion about team roles, personality preferences and how to take both leadership and followership roles. Educational leaders might facilitate activities that focus on exploring and surfacing unconscious biases about other professional groups, patients or families or by giving and obtaining multi-source feedback on self-efficacy in interprofessional groups and teams. Such activities need to be carefully facilitated in an inclusive environment as much of this work relates directly to people’s views and feelings about ‘self’. This can be quite threatening if not carried out in a safe psychological and physical environment. Using structured debriefs, role modelling inclusive leadership behaviours, sharing appropriate aspects of teachers’ own development, experiences and difficulties will help learners gain self-knowledge and interpersonal skills and reap great benefits for practice.

Within the model, reflective practice plays a key role in challenging unhelpful behaviours and restrictive ways of thinking. As reflection becomes a normal part of training, so might doctors become more comfortable with the process of critically examining choices and learning needs. Universities and post-graduate training programmes can highlight the importance of reflective practice in the development of a well-rounded practitioner by rewarding personal development as well as attainment. Recognizing and rewarding those who show the ability to adapt and evolve will raise the profile of the softer but vital skill of reflection.

Figure 2. An integrated model that shows the development of a doctors’ professional identity formation, on an inbound trajectory (see Fig 1), through experience and gaining knowledge and understanding of leadership, followership, team working, implicit leadership theory, social identity, self-efficacy and theories of self

Figure 2. An integrated model that shows the development of a doctors’ professional identity formation, on an inbound trajectory (see Fig 1), through experience and gaining knowledge and understanding of leadership, followership, team working, implicit leadership theory, social identity, self-efficacy and theories of self

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Followership, leadership and team-working in medicine are all directly impacted by professional identity formation. Doctors develop as professionals to hold respected positions, to aspire to a degree of autonomous decision making and leadership roles; they are encouraged to compete with their peers and to put their energies in to personal career progression. A better understanding of the culture within medicine and professional identity formation may not only help us to understand the complex dynamic between leaders and followers, but also enable better team working among health professionals. Providing doctors at all stages of training with specific development opportunities designed to enable the acquisition of team working, leadership and followership skills will help more effective team working and improve healthcare. This model provides a structured framework for designing such development activities.

Notes on Contributors

Judy McKimm is Professor of Medical Education, Director of Strategic Educational Development and Director of the MSc in Leadership for the Health Professions at Swansea University. She runs clinical and educational leadership programmes around the world and publishes widely on leadership and education.

Claire Vogan is an Associate Professor at Swansea University Medical School and the Director of Student Support and Guidance for Graduate Entry Medicine. She specialises in the support of students in difficulty and teaches on the Leadership, Medical Education and Graduate Entry Medicine programmes in Swansea.

Hester Mannion graduated from the University of Exeter with a 1st class degree in English Literature and went on to gain a PGCE from King’s College London. She has graduated from Swansea University Medical School in 2016 and now working as a doctor in Wales.

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest, including no financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

References

Barrow, M., McKimm, J., & Gasquoine, S. (2011). The policy and the practice: Early-career doctors and nurses as leaders and followers in the delivery of health care. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9239-2.

Bohmer, R. (2012). The instrumental value of medical leadership. White Paper-The King’s Fund, London, England. Retrieved from

http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/instrumental-value-medical-leadership-richard-bohmer-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., & Hoyt, C. L. (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of leadership ability and self‐efficacy: Predicting responses to stereotype threat. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 46-56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.20138.

Flower, J. (1999). In the Mush. Physician Executive, 25(1), 64–66.

Lee, T.H. (2010). Turning doctors into leaders. Harvard Business Review, 88(4), 50-58.

McKimm, J., & Wilkinson, T. (2015). “Doctors on the move”: Exploring professionalism in the light of cultural transitions. Medical Teacher, 37(9), 837-843. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1044953.

Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Finding “meaning” in psychology: a lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192.

Petrie, N. (2014). Future trends in leadership development. Center for Creative Leadership white paper. Retrieved from http://insights.ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/futureTrends.pdf

Till, A, & McKimm, J. (2016). Leading from the frontline. BMJ, in press.

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 83-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007.

Wenger-Trayner, E, & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice a brief introduction. Retrieved from http://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

West, M. A., & Lyubovnikova, J. (2013). Illusions of team working in health care. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 27(1), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777261311311843.

*Judy McKimm

Grove Building, Swansea University

Singleton Park, Swansea, SA2 8PP

Tel: (01792) 606854

Email: j.mckimm@swansea.ac.uk

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2017, 2(2), 8-17

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-2/OA1004

Wee Shiong Lim1,2, Kar Mun Tham3, Fadzli Baharom Adzahar, Han Yee Neo4, Wei Chin Wong1 & Charlotte Ringsted5

1Department of Geriatric Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; 2Health Outcomes and Medical Education Research, National Healthcare Group, Singapore; 3Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 4Department of Palliative Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; 5Centre for Health Science Education, Faculty of Health, Aarhus University, Denmark

Abstract

Background: Medical education research should aspire to illuminate the field beyond description (“What was done?”) and justification (“Did it work?”) research purposes to clarification studies that address “Why or how did it work?” questions. We aim to determine the frequency of research purpose in both experimental and non-experimental studies, and ascertain the predictors of clarification purpose among medical education studies presented at the 2012 Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC).

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of all eligible original research abstracts from APMEC 2012. Abstracts were classified as descriptive, justification or clarification using the framework of Cook 2008. We collected data on research approach (Ringsted et al., 2011), Kirkpatrick’s learner outcomes, statement of study aims, presentation category, study topic, professional group, and number of institutions involved. Significant variables from bivariate analysis were included in logistic regression analyses to ascertain the determinants of clarification studies.

Results: Our final sample comprised 186 abstracts. Description purpose was the most common (65.6%), followed by justification (21.5%) and clarification (12.9%). Clarification studies were more common in non-experimental than experimental studies (18.3% vs 7.5%). In multivariate analyses, the presence of a clear study aim (OR: 5.33, 95% CI 1.17-24.38) and non-descriptive research approach (OR: 4.70, 95% CI 1.50-14.71) but not higher Kirkpatrick’s outcome levels predicted clarification studies.

Conclusion: Only one-eighth of studies have a clarification research purpose. A clear study aim and non-descriptive research approach each confers a five-fold greater likelihood of a clarification purpose, and are potentially remediable areas to advance medical education research in the Asia-Pacific.

Keywords: Research Purpose; Research Approach; Medical Education Research; Asia-Pacific

Practice Highlights

- The hallmark of clarification research is the presence of a conceptual framework or theory that can be affirmed or refuted by the study results.

- We should aspire towards clarification studies that address “Why or how did it work?” questions.

- Only one-eighth of studies have a clarification research purpose.

- A clear study aim and non-descriptive research approach are potentially remediable areas to promote clarification studies.

I. INTRODUCTION

There is much debate about how to ensure that medical education research is not perceived as the poor relation of Biomedical research (Shea, Arnold, & Mann, 2004; Baernstein, Liss, Carney, & Elmore, 2007; Todres, Stephenson, & Jones, 2007).Some have proposed that if medical education were to fulfil its research potential and enjoy academic legitimacy, the discipline must develop a clearer sense of purpose and more rigorously follow the scientific line of enquiry characterized by a cycle of observation; formulation of a model or hypothesis to explain the results; prediction based on the model or hypothesis; and testing of the hypothesis (Cook, Bordage, & Schmidt, 2008a; Bordage, 2009). In particular, medical educators often focus on the first step (observation) and the last step (testing), but omit the intermediate steps (model formulation or theory building, and prediction), and perhaps more importantly, fail to maintain the cycle by building upon previous results. Some authorities attribute this lack of a conceptual framework as a major reason for the paucity of impactful research questions that can illuminate and magnify the body of knowledge to advance the field of medical education (Albert, Hodges, & Regehr, 2007; Cook et al., 2008b; Eva & Lingard, 2008).

Conceptual frameworks represent ways of thinking about an idea, problem, or phenomenon by relating to theories, models, evidence-based best practices or hypotheses (Rees & Monrouxe, 2010; Gibbs, Durning, & Van der Vleuten, 2011). The framework assists in formulating the research question, choosing an appropriate study design, and determining appropriate outcomes to answer the research question. Situating the research question within a conceptual framework elevates and transforms the research purpose from a study which is focused on local issues, into a clarification study of general interest by engendering generalizable knowledge which can be transferable to new settings and future research (Bordage, 2009; Bunniss & Kelly, 2010). Conceptual frameworks are also essential in interpreting the results. Their inter-dependent relationship is underscored by the fact that results are interpreted in light of the existing theories and conversely, existing boundaries of the theoretical framework may limit interpretation of the findings (Wong, 2016). For instance, in the field of observation-based assessments, there is a gradual theoretical shift from a more psychometric (based on large numbers of random elements) to a more expert judgement (based on fewer observation of well-informed opinions) framework (Hodges, 2013)

A. Cook’s Framework of Research Purpose

To better delineate this problem, Cook et al. (2008a) proposed a framework for classifying the purposes of research, namely description, justification and clarification. Description studies focus on the first step in the scientific method (observation) by addressing the question: “What was done?” Justification studies focus on the last step in the scientific method (testing) by asking: “Did it work?” However, without prior model formulation and prediction, the results may have limited application to future research or practice. In contrast, clarification studies seek to answer the question: “Why or how did it work?” The hallmark of clarification research is the presence of a conceptual framework that can be affirmed or refuted by the study results (Cook et al., 2008a; Ringsted, Hodges, & Scherpbier, 2011). Such research is often performed using classic experiments, but non-experimental methods such as correlation research, comparisons among naturally occurring groups, and qualitative research, are also applicable (Shea et al., 2004; Cook et al., 2008a).

Applying this framework in a systematic survey of 850 experimental and non-experimental studies on problem-based learning, Schmidt (2005) reported a paucity of clarification studies (7%) vis-à-vis description (64%) and justification (29%) studies. More recently, García-Durán et al. (2011) reported the predominance of description studies (92.8%) with very few justification (6.8%) studies and just one (0.4%) clarification study among research presentations at a medical education meeting in Mexico. These results are consistent with the seminal study of 105 articles describing education experiments in 6 major journals by Cook et al. (2008a), which noted that clarification studies were uncommon (12%) relative to justification (72%) and description (16%) studies. In this study, inter-rater agreement for these classifications was only moderate at 0.48, with disagreements largely occurring in the classification of less clear-cut single-group pre-test/post-test studies; this discrepancy has since been clarified in the revised definitions.

B. Gaps in Current Knowledge

Cook et al. (2008a) proposed expanding the use of their framework beyond the limited genre of experimental studies to incorporate non-experimental study designs. This input is sorely needed, as studies with a purely descriptive design (which may not qualify as research by some authorities) historically constituted a significant proportion of the literature in medical education (Reed et al., 2008; García-Durán et al., 2011). There is a unifying call for the use of stronger study designs in the field beyond cross-sectional descriptive approaches to enhance the quality of medical education research (Gruppen, 2007; Colliver & McGaghie, 2008).

The opportunity to extend the study of research purpose beyond experimental studies, was afforded by the research compass framework described by Ringsted et al. (2011). Core to the model is the conceptual framework, which is central to any research approach taken. The compass depicts four main quadrants of research approaches in the conduct of medical education research: (1) Explorative studies, aimed at modelling by seeking to identify and explain elements of phenomena and their relationships; (2) Experimental studies, with the main aim of justification to define appropriate interventions and outcomes; (3) Observational studies, aimed at predicting outcomes by the study of natural or static groups of people; and (4) Translational studies, which focus on implementing knowledge and findings from research in complex real-life settings.

Furthermore, predictors of a clarification research purpose in medical education scholarship have hitherto not been studied. Factors that are associated with better quality of medical education research include number of institutions studied (Reed et al., 2007; Reed et al., 2008), outcomes based on the widely-used hierarchy of Kirkpatrick (1967), and the presence of a clear statement of study intent (Cook et al., 2008b). However, the association between these factors with research purpose has not been previously examined.

C. Aims and hypothesis

In recent years, there is a surge of interest in research scholarship in medical education in the Asia-Pacific region. Concomitantly, regional forums such as the Asia-Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC) have emerged for the sharing of medical education research, along with ongoing discussions about how to propel the field forwards in conducting meaningful research that can inform educational practice (Gwee, Samarasekera, & Chong, 2012). Determining the prevalence of research purpose of medical education studies from the Asia-Pacific region would be of immediate relevance in ascertaining whether there is a similar lack of clarification studies and research approaches beyond descriptive study designs.

Building upon the earlier work of Cook et al. (2008a) in experimental studies, we developed an empirical operational model that combined the frameworks of Cook and Ringsted to broaden the evaluation of research purpose to include non-experimental studies. The objectives of our study are: (1) to determine the frequency of research purpose in both experimental and non-experimental studies, and (2) to ascertain the predictors of a clarification research purpose among original research abstracts presented at APMEC 2012. In light of the findings in earlier studies of the relative paucity of clarification studies (Schmidt 2005; Cook et al., 2008a; García-Durán et al., 2011), we hypothesize that the proportion of clarification studies would likewise be comparatively lower.

II. METHODS

A. Study setting

This review drew from research abstracts submitted to APMEC 2012. This study is part of a larger piece of work that aims to contribute to the research agenda in the Asia-Pacific region by determining the trends in research purpose and approach in the last 5 years (2008 to 2012). The APMEC is an established regional conference held in Singapore that serves as an accessible “clearinghouse” providing a timely and comprehensive snapshot of research in the Asia Pacific region. The theme for the 9th APMEC in 2012 was “Towards transformative education for healthcare professionals in the 21st century – nurturing lifelong habits of mind, behaviour and action.” The National Healthcare Group Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from review.

B. Study eligibility

All original research abstracts from APMEC 2012 were considered. Original research was defined as an educational intervention or trial; implementation of evidence based practice or guidelines; curriculum evaluation with subjective or objective outcomes; evaluation of an educational instrument or tool; qualitative research; and systematic reviews. We excluded abstracts from plenary lectures, workshops, special interest group meetings and discussions. Among 210 eligible abstracts, we excluded 24 that were not original research, thus yielding a final sample of 186 abstracts.

C. Data extraction

We performed a pilot study using randomly selected abstracts from APMEC 2011 conference in order to fine-tune definitions of study variables and to refine the data collection form. Four reviewers were involved in data collection. After training and harmonization in the pilot phase, the four raters achieved good to excellent agreement in the coding (overall percentage agreement: 80-87%; ACI-statistic: 0.73 – 0.82) (Gwet, 1991). For the study proper, each abstract was rated independently and in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and if no consensus was reached, via adjudication by a third independent reviewer.

D. Data collection

1) Study design

We classified abstracts into 2 broad categories based upon the “research compass” framework proposed by Ringsted et al. (2011): (1) Experimental, defined as any study in which researchers manipulated a variable (also known as the treatment, intervention or independent variable) to evaluate its impact on other (dependent) variables, including evaluation studies with experimental designs (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2003); and (2) Non-experimental, defined as all other studies that do not meet criteria for (1). Studies using mixed methods (for instance, an experimental design with a qualitative component) were classified according to the methodology that was deemed to be predominant.

Experimental studies were further sub-classified as experimental, quasi-experimental or pre-experimental according to established hierarchies of research designs (Creswell, 2013). We defined experimental studies by the presence of randomization; examples included factorial design, crossover design and randomized controlled trials. In contrast, for quasi-experimental studies, experimental and control groups were selected without random assignment of participants (Colliver & McGaghie, 2008). Pre-experimental studies, namely single group pre-post and post-only designs, did not have a control group for comparison.

Non-experimental studies were further sub-classified as descriptive, qualitative, psychometric, observational (comprising associational, case-control and cohort studies), and translational. Descriptive studies typically provide descriptions of phenomena, new initiatives or activities, such as curriculum design, instructional methods, assessment formats, and evaluation strategies (Ringsted, Hodges, & Scherpbier, 2011). Because pure descriptive study designs may not strictly qualify as research by some authorities, they are ranked by default as lowest in the hierarchy of study designs (Crites et al., 2014). Hence, when two study designs were identified within the same study with one being descriptive, we coded based upon the “higher” non-descriptive study design.

2) Research purpose

Research purpose is classified as description, justification or clarification based upon modified definitions of the Cook framework (Table 1). We further sub-classified clarification studies into whether they relate to theory, model/evidence-based practices, or hypothesis. Because the original definitions pertain only to experimental studies, several modifications were necessary in order to accommodate non-experimental studies in the integrated frameworks of Cook and Ringsted (Table 2). In the process, we were mindful to adhere to the original spirit of the definitions as far as possible. For instance, even though the original definition of justification studies merited a comparison group, we waived this requirement for good quality psychometric studies for which we deemed that there was sufficient rigor in the measures of validity and reliability to answer the question “Does this assessment tool work?” This was motivated by the intention to not “penalize” these studies and spuriously inflate the proportion of description studies in this category. Many validation studies of assessment tools often involve a single group design to determine whether a tool works via implicit comparison with an unknown ‘good enough’ criterion. The dominance of the psychometric views on assessment would also mean that many assessment studies are unlikely to have included an explicit statement of the underlying theoretical (Classical Test Theory, G-theory or Item Response Theory) framework.

Similarly, prompted by the observation that certain categories of approaches would be incongruent with a justification design, such as qualitative and observational studies, we delinked where appropriate the hierarchy of purpose from description to justification. Thus, a well-conducted observational study underpinned by a conceptual framework that explains the relationship between independent and dependent variables, would still qualify as a clarification study. Lastly, in response to difficulties encountered in coding during the pilot phase, we further modified the definition of clarification studies to specify the presence of a conceptual framework that fulfilled 3 crucial elements: 1) A theory, model, or hypothesis that asks “Why or how does it work?” 2) Transferability to new settings and future research; and 3) Confirmed or refuted by the results and/or conclusions of the study.

| A) Description | Describes what was done or presents a new conceptual model. Asks: “What was done?” There is no comparison group. May be a description without assessment of outcomes, or a “single-shot case study” (single-group, post-test only experiment). |

| B) Justification | Makes comparison with another intervention with intent of showing that 1 intervention is better than (or as good as) another. Asks: “Did it work?” (Did the intervention achieve the intended outcome?). Any experimental study with a control group or single-group with pre-post intervention assessment would qualify. Good quality psychometric studies with measures of validity and reliability are exempt from the need for a comparison group, since justification that the tool “works” typically does not involve a comparison group in these studies. Justification studies generally lack a conceptual framework or model that can be confirmed or refuted based on results of the study. |

| C) Clarification | Clarifies the processes that underlie observed effects. Asks: “Why or how did it work?” Often a controlled experiment, but could also use a case–control, cohort or cross-sectional research design. Much qualitative research also falls into this category. Its hallmark is the presence of a conceptual framework that can be transferable to new settings and future research, and which can be confirmed or refuted by the results and/or conclusions of the study. Further sub-classified into whether the conceptual framework pertains to a theory, model/evidence-based practice, or hypothesis. |

Table 1: Definitions of research purposes (modified from Cook et al.5)

| Study Design* | Descriptive | Justification | Clarification |

| (I) Experimental | |||

| – Experimental | Ö | Ö | Ö |

| – Quasi-experimental | Ö | Ö (no randomization) | Ö |

| – Pre-experimental | Ö | Ö (pre-post only) | Ö |

| (II) Non-experimental | |||

| (1) Explorative | |||

| – Descriptive | Ö | X | +/- |

| – Qualitative | Ö | X | Ö |

| – Psychometric | Ö | Ö (validity, reliability) | Ö |

| (2) Observation | |||

| – Associative | Ö | X | Ö |

| – Case control | Ö | X | Ö |

| – Cohort | Ö | X | Ö |

| (3) Translational | |||

| – Knowledge creation | |||

| Narrative | Ö | +/- | X |

| Quantitative review | Ö | Ö | +/- |

| Realist review | Ö | Ö | Ö |

| – Implementation | Ö | Ö | Ö |

| – Efficiency | Ö | Ö | Ö |

Table 2: Conceptual framework for possible classifications of research purpose when analyzed by research approach

*Modified from: Ringsted, C., Hodges, B., & Scherpbier, A. (2011). Medical Teacher, 33(9), 695-709.

3) Other variables

We extracted data on other variables which may affect the quality of medical education research. These included presentation category, topic of medical education addressed, professional group being studied, country of the study population, number of institutions involved, Kirkpatrick’s learner outcomes (if applicable), and statement of study intent. We measured learner outcomes on 4 levels based upon Kirkpatrick’s expanded outcomes typology, namely learner reactions (level 1), modification of attitudes/perceptions (level 2a), modification of knowledge/skills (level 2b), behavioural change (level 3), change in organizational practice (level 4a) and benefits to patients or healthcare outcome (level 4b) (Kirkpatrick, 1967; Reeves, Boet, Zierler, & Kitto, 2015). If a study reported more than one outcome, the rating for the highest-level outcome was recorded, regardless of whether this was a primary or secondary outcome. Although the validity of `hierarchical application of Kirkpatrick’s levels as a standard critical appraisal tool has been questioned, it still remains widely used in assessing the impact of interventions in medical education (Yardley & Donan, 2012). The research question is arguably the most important part of any scholarly activity and is framed as a statement of study intent often in the form of a purpose, objective, goal, aim or hypothesis (Cook et al., 2008b). We therefore collected data on whether there is an explicit statement of study intent, and if present, its quality as judged by correct location in the aims section; representation of study goals as opposed to mere stating of educational objectives; and completeness of information (i.e. whether any important objective was omitted).

E. Data Analysis

Results were summarized using descriptive statistics. Preplanned subgroup analyses were conducted with Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test using research purpose (description, justification or clarification) as the dependent variable. Significant variables from bivariate analysis (P<.10) were included in logistic regression analysis to ascertain which of these factors were associated with a clarification study purpose. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical tests were two-tailed and conducted at 5% level of significance.

III. RESULTS

A. Abstract characteristics

Our sample of 186 original research abstracts comprised 38 (20.4%) oral communications, 20 (10.8%) best posters, and 128 (68.8%) poster presentations. All abstracts employed the AMRaC (Aims, Methods, Results and Conclusion) format, with the exception of two unstructured abstracts that were presented in the symposiums. The most common topics covered were in the areas of curriculum (N=54, 29.0%), teaching and learning (N=53, 28.5%), assessment (N=19, 10.2%), and e-learning (N=14, 7.5%). Besides Singapore (N=62, 33.3%), there was a good mix of abstracts from other countries in the South-East Asian region such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines and Myanmar (N=19, 10.2%), and other parts of Asia (N=88, 47.3%). Most of the studies involved a single institution (N=169, 90.9%). Kirkpatrick’s learner outcomes were applicable in approximately half (N=94, 50.5%) of the abstracts, with level one (satisfaction, attitudes and opinions of the learners) accounting for 50 (53.2%) of eligible outcomes, followed by knowledge/skills (N=32, 34.0%). An explicit statement of study intent was absent in 29 (15.6%) of abstracts. Among the remaining abstracts with an aims statement, 8 (4.3%) were incorrectly sited in the methods sections, 20 (10.8%) stated educational objectives instead of study goals, and 10 (5.4%) were incomplete.

B. Prevalence of research purpose (Table 3)

Description research purpose was the most common (N=122, 65.6%), followed by justification (N=40, 21.5%) and clarification (N=24, 12.9%). The majority of clarification studies pertain to models (N=20, 83.3%), with the reminder involving theory (N=3, 12.5%) or hypothesis (N=1, 4.2%). The prevalence of clarification studies was higher in non-experimental (N=17, 18.3%) compared with experimental (N=7, 7.5%) studies. Conversely, for justification studies, the prevalence is higher for experimental (N=36, 38.7%) compared with non-experimental (N=4, 4.3%) studies.

| Study | N | Nature of abstracts | Descriptive N(%) | Justification N(%) | Clarification N(%) |

| Lim et al, 2016 | 186 | APMEC 2012 conference abstracts, not limited to particular study type | 122 (65.6) | 40 (21.5) | 24 (12.9)* |

| Experimental | 93 | 50 (53.8) | 36 (38.7) | 7 (7.5) | |

| Non-experimental | 93 | 72 (77.4) | 4 (4.3) | 17 (18.3) | |

| Schmidt, 2005 | 850 | Studies on problem-based learning, not limited to particular study type | 543 (63.9) | 248 (29.2) | 59 (6.9) |

| Cook et al, 2008 | 105 | Experimental studies from 6 major journals published in 2003-4 | 17 (16.2) | 75 (71.4) | 13 (12.4) |

| Garcia-Duran et al, 2011 | 265 | UNAM 2008 and 2010 conference abstracts, not limited to particular study type | 246 (92.8) | 18 (6.8) | 1 (0.4) |

APMEC: Asia-Pacific Medical Education Conference; UNAM: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

*Comprises 83.3% Models, 12.5% theory and 4.2% hypothesis.

Table 3. Comparison of research purpose among various studies

C. Relationship of variables with research purpose (Table 4)

There was no significant association between research purpose with research category, professional group, country of study, and number of institutions (Table 4). Learner outcomes of Kirkpatrick’s level 2 and above were more likely to have a justification or clarification research purpose (c2 [4, N=186] = 67.12, p<.001), as were studies with a clear statement of study objectives (c2 [2, N=186] = 10.51, p=.005). Experimental studies were less likely than non-experimental to involve a description purpose (c2 [2, N=186] = 29.26, p=<.001) even though the frequency of clarification studies was comparatively lower (7.5% vs 18.3%). Non-descriptive studies were more likely to have a justification or clarification purpose (c2 [2, N=186] = 71.70, p=<.001).

D. Logistic Regression (Table 5)

We included in the model three independent variables (statement of study intent, Kirkpatrick’s outcome levels and descriptive research approach) which were significant in bivariate analysis. Experimental design was not included due to multicollinearity resulting from high correlation with Kirkpatrick’s levels. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was non-significant (c2 [5, N=186] = 1.78, p=.881), indicating goodness of fit of the final model. The presence of a clear study aim [Odds ratio (95% CI) = 5.33(1.17 – 24.38)] and non-descriptive research approach [Odds ratio (95% CI) = 4.70(1.50 – 14.71)] but not higher Kirkpatrick’s outcome levels, independently predicted a clarification research purpose.

| Characteristic | Description N (%) | Justification N (%) | Clarification N (%) | P |

| Study category | .765 | |||

| Poster | 88 (68.8) | 25 (19.5) | 15 (11.7) | |

| Best Poster | 12 (60.0) | 5 (25.0) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Orals | 22 (57.9) | 10 (26.3) | 6 (15.8) | |

| Professional Group | .143 | |||

| Postgraduate Medical | 35 (74.5) | 9 (19.1) | 3 (6.4) | |

| Undergraduate Medical, Clinical | 49 (62.0) | 18 (22.8) | 12 (15.2) | |

| Undergraduate Medical, Basic Science | 20 (64.5) | 8 (25.8) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Nursing | 7 (53.8) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (38.5) | |

| Allied Health | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Country of study | .492 | |||

| Singapore | 39 (62.9) | 16 (25.8) | 7 (11.3) | |

| South-East Asia, excluding Singapore | 11 (57.9) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Asia, excluding South-East Asia | 61 (69.3) | 14 (15.9) | 13 (14.8) | |

| Europe | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) | 1 (11.1) | |

| North America | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Number of institutions studied | .857 | |||

| 1 | 111 (65.7) | 37 (21.9) | 21 (12.4) | |

| 2 | 4 (57.1) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | |

| >2 | 7 (70.0) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Kirkpatrick’s learner outcomes | <.001 | |||

| Not applicable | 73 (79.3) | 5 (5.4) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Kirkpatrick’s level 1 | 40 (80.0) | 7 (14.0) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Kirkpatrick’s level 2 and above | 9 (20.5) | 28 (63.6) | 7 (15.9) | |

| Aims statement | .005 | |||

| Absent or unclear | 52 (77.6) | 13 (19.4) | 2 (3.0) | |

| Present, clear aims | 70 (58.8) | 27 (22.7) | 22 (18.5) | |

| Experimental study | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 50 (53.8) | 36 (38.7) | 7 (7.5) | |

| No | 72 (77.4) | 4 (4.3) | 17 (18.3) | |

| Descriptive study | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 94 (92.2) | 3 (2.9) | 5 (4.9) | |

| No | 28 (33.3) | 37 (44.0) | 19 (22.6) |

Table 4. Relationship of variables with research purpose

| b | S.E. | Wald | P | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Clear study aims | 1.67 | .78 | 4.66 | .031* | 5.33

(1.17 – 24.38) |

| No outcomes^ | -.17 | .73 | .06 | .815 | 1.19

(0.29 – 4.94) |

| K2 outcomes and above^ | -.10 | .82 | .02 | .900 | 0.90

(0.18 – 4.52) |

| Non-Descriptive study | 1.55 | .58 | 7.09 | .008** | 4.70

(1.50 – 14.71) |

Table 5. Logistic regression predicting likelihood of clarification research purpose

*P < .05; **P < .01

^Reference group: Kirkpatrick level one outcomes

Nagelkerke R square: 0.197

IV. DISCUSSION

The seminal study by Cook et al. (2008a) ushered in a series of studies that examined research quality through the lenses of research purpose. The underlying premise is that situating the research question and the accompanying study design, methods and analysis within a strong conceptual framework, facilitates the conduct of quality research that transcends the local context, allows transferability of findings, and can lead to new programmes of research (Bordage, 2009; Gill & Griffin, 2009; Beran, Kaba, Caird, & McLaughlin, 2014). By integrating the frameworks of Cook and Ringsted, this systematic review of APMEC 2012 original research abstracts contributes to this conversational turn by extending the Cook framework to include non- experimental studies. The strengths of our study include duplicate review at all stages; standardized definitions of coding categories; clear and detailed description of the methods/procedures involved; and high inter-rater reliability among the coders.

The distribution of research purpose in our study is broadly in line with earlier studies. Only around one-eighth of original research studies have a clarification research purpose. Around two-thirds of studies focused on “What was done?” description purposes which are not readily transferable beyond the immediate context of the individual study. Nonetheless, the relatively higher proportion of clarification purpose in our cohort vis-à-vis the 0.4-12.0% reported in earlier studies (Schmidt, 2005; Cook et al., 2008a; García-Durán et al., 2011) is reassuring (Table 3). Similar to Cook et al. (2008a), experimental studies account for the majority of justification studies. This is unsurprising, given the inherent nature of experimental studies in answering “Does it work?” question. Conversely, because research approaches such as qualitative and observational studies tend to ask “Why?” or “How?” questions, non-experimental designs have a higher proportion of clarification purpose compared with experimental studies (18.3% vs. 7.5%). To promote the further development of medical education scholarship in the Asia-Pacific region, we propose tapping upon regional initiatives like the Asia Pacific Medical Education Network (APME-Net), the Asian Medical Education Association, as well as regional journals such as The Asia-Pacific Scholar, to emphasize clarification studies that promote the wider application of theory which can be affirmed or refuted by the study results.

Our study also highlighted that a non-descriptive study design, in concert with a clear statement of study aims, each predicted a 5-fold increased odds of a clarification research purpose. Similar to developments in outcomes-based research within the field, we advocate a “design-balanced” approach whereby the best study design is one that best answers the research question within a given context (Lim, 2013). While descriptive study designs retain a role in the sharing of innovations and preliminary ideas, we should encourage the greater use of more rigorous non-descriptive study designs where appropriate (Ringsted et al., 2011). For experimental studies, quasi-experimental designs with a control group and true experimental designs characterized by randomization are less likely to overestimate effect size compared with single group pre-/post-test studies (Cook, Levinson, & Garside, 2011). In non-experimental studies, the plurality of non-descriptive approaches includes qualitative, psychometric, observational and translational research designs (Cheong et al., 2015; Ong et al., 2016).

Given the fundamental importance of the research question, it is disconcerting that around one-sixth of abstracts lack an explicit objective statement of study aims, whilst another one-fifth have an aims statement that is either incorrectly sited, confused with educational objectives, or incomplete. This may be indicative of poor reporting quality, or more ominously, the lack of a clear research question underpinning the research study (Cook, 2016). A systematic review that evaluates the quality of abstracts of 110 experimental studies reported that essential elements of an informative abstract were often under-reported, especially in unstructured abstracts (Cook et al., 2007b). There is evidence that structured formats improve the quality of reporting of research abstracts (Taddio et al., 1994; Wong et al., 2005; Cook et al., 2007a). Reporting quality is positively associated with superior methodological quality (Cook et al., 2011), which in turn is associated with funding for medical education research (Reed et al., 2007). There is thus a case to be made for the consistent use of structured abstracts with relevant and thoughtful headings beyond the IMRaD (Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion) format. Where relevant, separate headings for background and aims would neatly cater to the need for both literature review plus an explicit statement of study objectives. In addition, we propose a separate heading for conceptual framework or study hypothesis to spur the development of higher-order clarification studies, and a “limitations” heading to prompt researchers to think about more rigorous study designs and outcomes through consideration of the limitations of their current research (Cook et al., 2007b).

Some limitations are worth highlighting. Our research is based upon conference abstracts, which has a significant word constraint as compared to full-length papers. The validity of our findings is highly dependent on the reporting quality of the abstracts, such that the quality of a research (as judged by research purpose and approach) may be more a reflection of the reporting quality rather than the actual quality of research. Notwithstanding, evidence affirming the positive relationship between reporting and methodological quality lends credence to the validity of assessing conference abstracts as an indirect quality indicator of research (Cook et al., 2011). Moreover, our research involved fairly objective and essential elements of reporting such as study aims and outcomes. Secondly, we choose to focus on specific aspects of quality rather than a more comprehensive evaluation of methodological quality using validated scales such as the medical education research study quality instrument (MERSQI) (Reed et al., 2007). Our approach is compatible with the ongoing debate about what constitutes quality in medical education research, which highlights the pre-eminence of the conceptual framework in framing meaningful research questions that can advance the field (Eva, 2009; Monrouxe & Rees, 2009).

V. CONCLUSIONS

Taken together, our study identified gaps that will, hopefully, serve to promote further discourse among medical education scholars in the region about the purpose and approach of their research inquiry. To advance the research agenda of the Asia-Pacific region, we should tap upon regional platforms to promote clarification studies that employ more rigorous research approaches beyond cross-sectional descriptive study designs. The thoughtful use of structured abstracts to facilitate ancillary factors such as a clear aims statement that makes explicit the underlying conceptual framework, and study design, can also pave the way towards addressing gaps in research purpose and approach.

Notes on Contributor

W. S. Lim planned and executed the study, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. K. M. Tham, F. B. Adzahar, H. Y. Neo, and W. C. Wong contributed to acquisition of data. C. Ringsted contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the paper and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by an educational research grant from the National Healthcare Group Health Outcomes and Medical Education Research office.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Albert, M., Hodges, B., & Regehr, G. (2007). Research in Medical Education: Balancing Service and Science. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 12(1), 103-115.

Baernstein, A., Liss, H. K., Carney, P. A., & Elmore, J. G. (2007). Trends in study methods used in undergraduate medical education research, 1969-2007. JAMA, 298(9), 1038-1045.

Beran, T. N., Kaba, A., Caird, J., & McLaughlin, K. (2014). The good and bad of group conformity: a call for a new programme of research in medical education. Medical Education, 48(9), 851-859.

Bordage, G. (2009). Conceptual frameworks to illuminate and magnify. Medical Education, 43(4), 312-319.

Bunniss, S., & Kelly, D. R. (2010). Research paradigms in medical education research. Medical Education, 44(4), 358-366.

Cheong, C.Y., Merchant, R.A., Ngiam, N.S.P. & Lim, W.S. (2015). Case-based simulated patient sessions in Mental-State Examination teaching. Med Education, 49(11), 1147-8.

Colliver, J. A., & McGaghie, W. C. (2008). The reputation of medical education research: quasi-experimentation and unresolved threats to validity. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 20(2), 101-103.

Cook, D. A., Beckman, T. J., & Bordage, G. (2007a). Quality of reporting of experimental studies in medical education: a systematic review. Medical Education, 41(8), 737-745.

Cook, D. A., Beckman, T. J., & Bordage, G. (2007b). A systematic review of titles and abstracts of experimental studies in medical education: Many informative elements missing. Medical Education, 41(11), 1074-1081.

Cook, D. A., Bordage, G., & Schmidt, H. G. (2008a). Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education. Medical Education, 42(2), 128-133.

Cook, D. A., Bowen, J. L., Gerrity, M. S., Kalet, A. L., Kogan, J. R., Spickard, A., & Wayne, D. B. (2008b). Proposed standards for medical education submissions to the Journal of General Internal Medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(7), 908-913.

Cook, D. A., Levinson, A. J., & Garside, S. (2011). Method and reporting quality in health professions education research: a systematic review. Medical Education, 45(3), 227-238.

Cook, D. A. (2016). Tips for a great review article: crossing methodological boundaries. Medical Education, 50(4), 384-387.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Crites, G. E., Gaines, J. K., Cottrell, S., Kalishman, S., Gusic, M., Mavis, B., & Durning, S. J. (2014). Medical education scholarship: An introductory guide: AMEE Guide No. 89. Medical Teacher, 36(8), 657-674.

Eva, K. W., & Lingard, L. (2008). What’s next? A guiding question for educators engaged in educational research. Medical Education, 42(8), 752-754.

Eva, K. W. (2009). Broadening the debate about quality in medical education research. Medical education, 43(4), 294-296.

Fraenkel, J.R., & Wallen, N.E. (2003). How to design and evaluate research in education. New York: NY: McGraw-Hill.

García-Durán, R., Morales-López, S., Durante-Montiel, I., Jiménez, M., & Sánchez-Mendiola, M. (2011). Type of research papers in medical education meetings in Mexico: an observational study. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Medical Education in Europe, Vienna, Austria.

Gibbs, T., Durning, S., & Van Der Vleuten, C. (2011). Theories in medical education: Towards creating a union between educational practice and research traditions. Medical teacher, 33(3), 183-187.

Gill, D., & Griffin, A. E. (2009). Reframing medical education research: let’s make the publishable meaningful and the meaningful publishable. Medical Education, 43(10), 933-935.

Gruppen, L.D. (2007). Improving medical education research. Teaching and learning in medicine, 19(4), 331-335.

Gwee, M. C., Samarasekera, D. D., & Chong, Y. (2012). APMEC 2013: In Celebration of Innovation and Scholarship in Medical and Health Professional Education. Medical Education, 46(s2), iii-iii.

Gwet, K. (1991). Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability. STATAXIS Publishing Company.

Hodges, B. (2013). Assessment in the post-psychometric era: Learning to love the subjective and collective. Medical Teacher, 35(7), 564-568.

Kirkpatrick, D.L. (1967). Evaluation of training. In Training and development handbook, edited by R. L. Craig and L. R. Bittel. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 87-112.

Lim, W. S. (2013). More About the Focus on Outcomes Research in Medical Education. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1052.

Monrouxe, L.V., & Rees, C. E. (2009). Picking up the gauntlet: constructing medical education as a social science. Medical Education, 43(3), 196-198.

Ong, Y.H., Lim, I., Tan, K.T., Chan, M. & Lim, W.S. (2016). Assessing Shared Leadership in Interprofessional Team Meetings: A Validation Study. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 1(1), 10-21.

Reed, D. A., Cook, D.A., Beckman, T. J., Levine, R. B., Kern, D. E., & Wright, S. M. (2007). Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA, 298(9), 1002-1009.

Reed, D. A., Beckman, T. J., Wright, S. M., Levine, R. B., Kern, D. E., & Cook, D. A. (2008). Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s Medical Education Special Issue. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(7), 903-907.

Rees, C. E., & Monrouxe, L. V. (2010). Theory in medical education research: how do we get there?. Medical Education, 44(4), 334-339.

Ringsted, C., Hodges, B., & Scherpbier, A. (2011). ‘The research compass’: An introduction to research in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 56. Medical Teacher, 33(9), 695-709.

Reeves, S., Boet, S., Zierler, B., & Kitto, S. (2015). Interprofessional Education and Practice Guide No. 3: Evaluating interprofessional education. Journal of interprofessional care, 29(4), 305-312. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.1003637.

Schmidt, H.G. (2005). Influence of research in practices in medical education: the case of problem-based learning. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Medical Education in Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Shea, J. A., Arnold, L., & Mann, K. V. (2004). A RIME perspective on the quality and relevance of current and future medical education research. Academic Medicine, 79(10), 931-938.

Taddio, A., Pain, T., Fassos, F. F., Boon, H., Ilersich, A. L., & Einarson, T. R. (1994). Quality of nonstructured and structured abstracts of original research articles in the British Medical Journal, the Canadian Medical Association Journal and the Journal of the American Medical Association. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 150(10), 1611.

Todres, M., Stephenson, A., & Jones, R. (2007). Medical education research remains the poor relation. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 335(7615), 333.

Wong, G. (2016). Literature reviews in the health professions: It’s all about the theory. Medical education, 50(4), 380-382.

Wong, H. L., Truong, D., Mahamed, A., Davidian, C., Rana, Z., & Einarson, T. R. (2005). Quality of structured abstracts of original research articles in the British Medical Journal, the Canadian Medical Association Journal and the Journal of the American Medical Association: a 10-year follow-up study. Current Medical Research and Opinion®, 21(4), 467-473.

Yardley, S., & Dornan, T. (2012). Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence’. Medical Education, 46(1), 97-106.

*Wee Shiong Lim

Department of Geriatric Medicine

Tan Tock Seng Hospital

11 Jalan Tan Tock Seng, TTSH Annex 2, Level 3

Singapore 308433

Tel: +65 6359 6474

Email: Wee_Shiong_Lim@ttsh.com.sg

Published online: 5 September, TAPS 2017, 2(3), 15-21

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-3/OA1034

Eng-Tat Ang1, Siti Nabihah Binte Abu Talib1, Mark Thong2 & Tze Choong Charn2

1Department of Anatomy, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore; 2Department of Otolaryngology, Sengkang Hospital, Singhealth, Singapore

Abstract

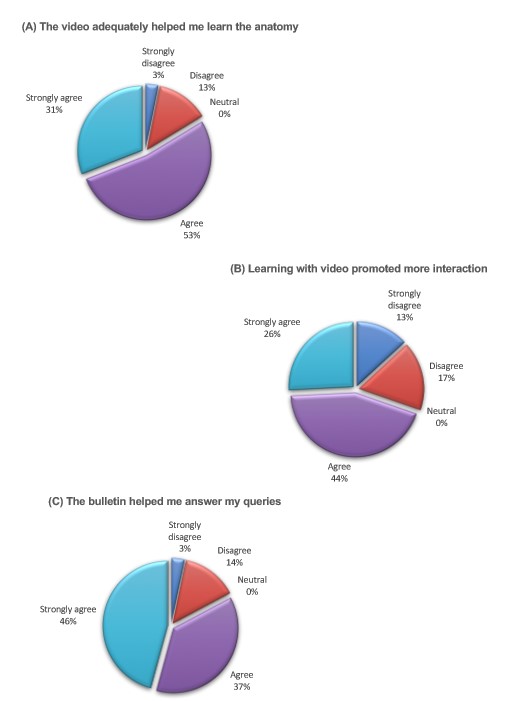

Videos when properly embedded within the curriculum might make learning the basic sciences such as human anatomy much more engaging for medical students. It is unclear how the use of video is advantageous. Possible scientific causations for such an observation include visual and auditory stimulation, coupled with ease of access for the learner. Video usage empowers the medical students to learn in an active manner. However, this cannot happen if motivation for self-directed learning is lacking. This research aims to 1) Elucidate qualitative and quantitative comments on how videos help to enhance anatomy learning. 2) Quantify the level of motivation for self-directedness in order for videos to be impactful amongst medical students. A short video was embedded into selected part of the 1st year anatomy curriculums (pharynx and larynx) for selected medical students (n=100). Separately, all students in the cohort (n=300) were assessed for their attitude towards active learning via a survey on motivation levels. This was done using the modified PRO-SDLS. Results showed that 85% of the participants enjoyed learning the anatomy of the pharynx and larynx with embedded videos (P<0.05). Specifically, they liked the Q&A sessions, the virtual chat platform, and the mode of delivery. Participants perceive it to be clearer, and more structured (P<0.05). Concomitantly, all medical students surveyed exhibited unusually high motivation for self-directed learning (³ agreeing with probe questions in the PRO-SDLS) (P<0.05). This allows videos to be impactful. In conclusion, with videos, medical students appreciated the relevance of basic regional anatomy more in a statistically significant manner compared to controls. However, a threshold motivation is required for active learning to be successful.

Keywords: Video; ENT Anatomy; Feedback; Medical Education

Practice Highlights

- Medical students are generally an intrinsically self-driven group so didactic lectures may not be the optimal way to teach them.

- An appropriate short video embedded in the curriculum will trigger active learning amongst medical students.

- A certain threshold for Self-directedness (motivation) must be present for videos to be impactful.

I. INTRODUCTION

The use of video is fast becoming popular within medical education (Baldwin et al., 2016; Dong & Goh, 2015). In the larger scheme of academic medicine, the advent of media such as YouTube and Dailymotion coupled with ease of access to electronic gadgets and the internet is threatening the traditional way of learning (Egle, Smeenge, Kassem, & Mittal, 2015; Hansen et al., 2016; Pusz & Brietzke, 2012). Furthermore, expectations of millennial medical students, and the teaching-learning environments in general, are slowly but surely evolving (Lim & Seet, 2008; Youm & Wiechmann, 2015). More importantly, the learning and resource gathering habits of medical students and residents are also changing, as they depend increasingly on audio-visuals to score better in examinations (Ahmad, Sleiman, Thomas, Kashani, & Ditmyer, 2016). Specifically in the context of anatomy education, millennials often resort to YouTube videos to further enhance their learning (Barry et al., 2016). Taken together, medical education as we once know is under considerable pressure to change. In the face of these developments, teachers need to adopt newer teaching-learning techniques and delivery methods. One such modality is the usage of videos. So what does it take to make this endeavour really successful? The scientific basis for this observation is unclear. It could be the result of an array of factors but was recently explained using the science of learning (Mayer, 2010). All things considered, it is crucial that faculty members reinvent themselves to stay on top of the challenges, and to customise their institution´s curriculum to match and complement student´s needs. This will ensure accurate and proper dissemination of relevant knowledge, as well as scholarly information (Egle et al., 2015; Pusz & Brietzke, 2012; Volsky, Baldassari, Mushti, & Derkay, 2012). Traditionally, at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM), National University of Singapore (NUS), medical students have learnt human anatomy from a well-wrought system of lectures, practical classes and small group tutorials (Ang et al., 2012). In recent times, due to curricular reforms, lecture times are proposed to be shortened, and in place of it, more interactive sessions. One initiative is the use of videos to trigger active learning, leaving more time for interactions, questions and answers (Q&A), and for reflections. A quick literature review shows that the use of multimedia (videos) to achieve such aims has been attempted in other parts of the world, with fairly convincing outcomes (Catling, Williams, & Baker, 2014; Soh, Reed, Poulos, & Brennan, 2013). These include drug prescriptions, detecting radiological lesions, and in general pathology education (Thakore & McMahon, 2006). We hope to emulate this pedagogy to teach medical students basic anatomy of the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) in a clinically-orientated manner at this institution. We believe this endeavour will help medical students in their anatomy education, and to help teachers understand the values of videos, and to further encourage buy-ins from key stake holders (Calaman et al., 2016; Choi-Lundberg, Low, Patman, Turner, & Sinha, 2016). We hypothesize that students will enjoy learning from videos in class, and its success hinges on having a high level of self-directedness (motivation) in learning.

II. METHODS

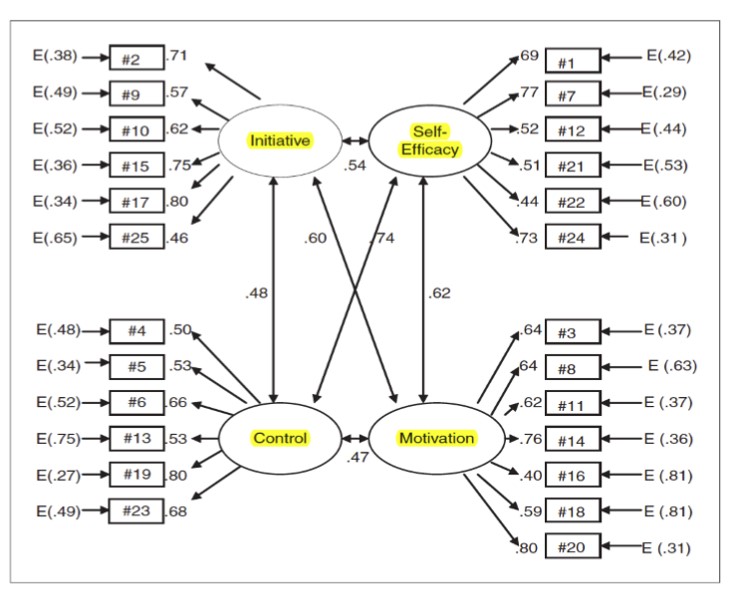

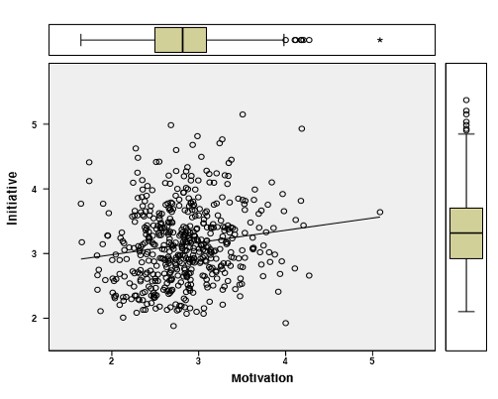

The entire first year medical students cohort (M1) from the YLLSoM (n=300) was recruited for the research, and surveyed using the Personal Responsibility Orientation to Self-Direction in Learning Scale (PRO-SDLS) (Stockdale & Brockett, 2011). This is to ascertain, and assess the level of baseline self-directedness/ motivation in their daily learning. They were polled on how much they agree with a list of statements provided in the modified scale (See Appendix). The responses are categorised by a Likert scale involving 5 options – “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Sometimes”, “Disagree” and “Strongly disagree” (Komorita, 1963). This is to quantify the 4 domains, namely: 1) Initiatives; 2) Control; 3) Self-efficacy; 4) Motivation.

A. Participants

In the research, selected medical students from the M1 cohort (n = 100; equal number of males and females; 19-21 years old) were asked to provide qualitative and quantitative feedback with regards to videos in ENT anatomy education. As a pre-requisite, it is assumed that these students would have also already attended all lectures and practical classes pertaining to the anatomy of the pharynx and larynx.

1) Without video: All students in the cohort were educated through a system of lectures, practical classes, and tutorials based on a prescribed list of objectives outlined at the beginning of the class. The lecture was covered in a didactic manner, and the tutorials manned by different tutors (n=16) using varying techniques in engaging these students. However, there was no active learning using any prescribed videos.

2) With video: The following links were provided for these students:

(1)http://vidcast.nus.edu.sg/camtasiarelay/Pharynx_Larynx_-_20150211_183654_26.html

A video was embedded into the tutorial teaching the head and neck anatomy (Dr. Ang’s group), and students were instructed to view them before coming to class. Controls for the intervention were the rest of the cohorts. The video (~15 minutes duration), features an introduction, learning objectives, demonstrations, self-tests using plastic anatomical models, clinical anatomy via endoscopy and fluoroscopy images. After tackling the questions individually, the group received feedback, and was given the opportunity to raise questions via an electronic bulletin board. During the class, participants were further directed to other learning resources in the Internet. To consolidate the learning, students were allowed to review the videos ad libitum, interact with classmates, and post questions to their tutor via the bulletin board. Both qualitative and quantitative feedback were obtained and tabulated from the surveys and observations based on best practice (Kelley, Clark, Brown, & Sitzia, 2003; Tai & Ajjawi, 2016), and this was carried out before and at the end of the intervention. At the end of session, all participants need to fill up the post-PRO-SDLS survey.

B. Data Analysis