The COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on interns in a paediatric rotation

Submitted: 21 August 2020

Accepted: 12 November 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 57-65

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/OA2378

Nicholas Beng Hui Ng1,2, Mae Yue Tan1,2, Shuh Shing Lee3, Nasyitah binti Abdul Aziz3, Marion M Aw1,2 & Jeremy Bingyuan Lin1,2

1Khoo Teck Puat-National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Health System Singapore; 2Department of Paediatrics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Centre for Medical Education (CenMED), Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought about additional challenges beyond the usual transitional stresses faced by a newly qualified doctor. We aimed to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on interns’ stress, burnout, emotions, and implications on their training, while exploring their coping mechanisms and resilience levels.

Methods: Newly graduated doctors interning in a Paediatric department in Singapore, who experienced escalation of the pandemic from January to April 2020, were invited to participate. Participants completed the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Maslach’s Burnout Inventory (MBI), and Connor Davidson Resilience Scale 25-item (CD-RISC 25) pre-pandemic and 4 months into COVID-19. Group interviews were conducted to supplement the quantitative responses to achieve study aims.

Results: Response rate was 100% (n=10) for post-exposure questionnaires and group interviews. Despite working through the pandemic, interns’ stress levels were not increased, burnout remained low, while resilience remained high. Four themes emerged from the group interviews – the impacts of the pandemic on their psychology, duties, training, as well as protective mechanisms. Their responses, particularly the institutional mechanisms and individual coping strategies, enabled us to understand their unexpected low burnout and high resilience despite the pandemic.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that it is possible to mitigate stress, burnout and preserve resilience of vulnerable healthcare workers such as interns amidst a pandemic. The study also validated a multifaceted approach that targets institutional, faculty as well as individual levels, can ensure the continued wellbeing of healthcare workers even in challenging times.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stress, Burnout, Resilience, Junior Doctor, Intern

Practice Highlights

- Intern doctors face additional and unique challenges in a pandemic, besides the usual stresses of their school-to-work transition.

- Our study shows that a multi-faceted approach that target institution, faculty and individual can lead to reduced burnout and preserved resilience in these doctors.

I. INTRODUCTION

With the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there are new stressors contributing to burnout in healthcare workers. We were particularly interested in evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on newly qualified doctors doing their internship, also known as House Officers or post-graduate year 1 doctors in Singapore. This is a particularly vulnerable group of healthcare workers as the school-to-work transitional year is traditionally a challenging period with high reports of burnout (Low et al., 2019; Sturman et al., 2017).

In Singapore, our first case of COVID-19 was on 23 January 2020. By February 2020, Singapore had one of the highest numbers of cases out of China (Chia & Moynihan, 2020). A global pandemic was declared on 12 March 2020. In early April 2020, the government tightened local measures with a ‘Circuit Breaker’, akin to the lockdowns in many countries (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2020).

Newly graduated doctors in Singapore complete a 12-month training period (4-month rotations in 3 different disciplines) prior to full medical registration. The period of January to April 2020 was during their third block and coincided with the full evolution of the pandemic, which came with multiple unexpected changes in work within the hospital. These included new protocols for personal protection, team segregation and mechanisms to cope with the increase in COVID-19 cases. In our department, interns and residents were divided into active and passive teams rotating fortnightly, where the active team had to shoulder the responsibility of caring for at risk or COVID-19 paediatric patients, with an intense overnight call duty schedule, different from the weekly frequency in the non-pandemic setting. In addition to work changes, there were also cancellation of overseas leave as well as cessation of scheduled teaching sessions.

With these changes, we aimed to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on interns in our department, focusing on their psychological well-being in terms of stress and burnout, and impact on clinical training. Our secondary aim was to explore the interns’ resilience, coping mechanisms and identify systemic measures they perceived as helpful during this pandemic.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design and Sample

This was a mixed-methods quantitative and qualitative study involving interns who worked from January to April 2020, in a paediatric department at a tertiary academic hospital that actively admitted COVID-19 patients. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for both the quantitative and qualitative components of the study.

B. Quantitative Data Methodology

Pre-pandemic data on perceived stress, burnout and resilience levels were collected a priori in early January 2020, when the interns first joined the department. This was part of a baseline evaluation of a separate study. We employed validated scales: the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983), the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) for Health Services Survey (Maslach & Leiter, 2016), and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 25-item (CD-RSIC 25) (Connor & Davidson, 2003) to measure stress, burnout and resilience respectively. The PSS measures the perception of stress, and is designed to tap how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives. Scores ranging from 0-13, 14-26, and 27-40 are mild, moderate, and high perceived stress, respectively. The MBI is a 22-item inventory with scores in 3 domains of burnout: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal accomplishment (PA) based on multiple questions for each of these subscales. We used a strict definition of burnout as having fulfilled criteria in all 3 domains of the MBI (i.e. high EE ≧ 27, high DP ≧ 10, and low PA ≦ 33). A liberal definition (i.e. high EE ≧ 27 and high DP ≧ 10 with or without a low PA) was also measured as both definitions are widely adopted in literature (Rotenstein et al., 2018). The CD-RISC 25-item (English version) is a validated scale to measure resilience. It gives a score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience. On completion of the posting in end April 2020, the interns repeated the same set of questionnaires.

C. Qualitative Data Methodology: Group Discussions

We conducted group interviews to further evaluate the responses obtained from the questionnaires and to better understand the impact on the interns. Invitation emails were sent to all interns; participation was voluntary. The questions were developed to explore the challenges, emotions, psychological states and reflections of their coping mechanisms and supportive measures of the interns while working in the pandemic. The questions were developed and refined by the authors after discussion and consensus (Appendix 1). Two group interviews were conducted on separate days by the same interviewer, to maintain team segregation and physical distancing. Each group had 5 participants. The sessions were recorded and subsequently transcribed by an independent party.

D. Data Analysis

Quantitative data on the validated scales were scored according to the corresponding manuals. Descriptive and comparative analysis was done with SPSS, Version 23. For the interviews, thematic analysis was conducted. Two of the authors (SS & NAA) read the transcripts to understand fully the data, generated the initial codes independently. Next, codes with consistently similar content were grouped into sub-categories, and similar sub-categories were then combined into categories to form themes. In the event there were differing views on the coding or theme, they re-examined the primary data and further discussed to achieve consensus.

III. RESULTS

A. Quantitative Results

We had a 90% response rate (n=9) for the pre-exposure and 100% (n=10) for the post-exposure questionnaires. There was no change in PSS scores among the interns despite the pandemic, with both median scores in the moderate stress category at 17.5 post-exposure and 17 pre-exposure. There was no high perceived stress in all interns post-exposure. Using the strictest definition of burnout, burnout remained low at 20% post-exposure, compared to 11.1% pre-exposure (Table 1). When a more liberal definition of burnout is used as discussed in the methodology section, only 20% of participants were burnout post-exposure, compared to 66.7% of participants pre-exposure. High resilience levels were maintained, with median score of 74 pre-exposure and 72.5 post-exposure.

|

Measures |

Pre-exposure, (n=9) |

Post-exposure, (n=10) |

p value |

|

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) |

|||

|

Median (SD) |

17 (6.75) |

17.50 (5.70)

|

N.A |

|

Low stress, n (%) |

4 (44.4%) |

3 (30%)

|

0.65 |

|

Moderate stress, n (%) |

4 (44.4%) |

7 (70%)

|

0.37 |

|

High stress, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

0 (0%)

|

0.474 |

|

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) |

|||

|

No burnout, n (%) |

3 (33.3%) |

4 (40.0%) |

0.999 |

|

Strict definition of burnout, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

2 (20.0%)

|

0.999 |

|

Liberal definition of burnout, n (%) |

6 (66.7%) |

2 (20%) |

0.09 |

Table 1: Quantitative results showing scores on the Perceived Stress Scale and Maslach Burnout Inventory of the interns pre-pandemic, compared with scores post-exposure. (SD= Standard Deviation).

B. Qualitative Results

We had 100% participation in the group interviews (n=10). Four themes emerged from the qualitative analysis – psychological impact (feelings), impact on duties, impact on teaching and learning as well as preventive measures and support system. These are summarised in Table 2.

|

Key Theme 1: Psychological Impact (Feelings) |

|

|

Sub-themes |

Sample of quotations |

|

a) Loss of control coping with many changes

b) Emotional exhaustion (fear, burnout, uncertainty, loneliness)

c) Positive feelings |

“…throughout the pandemic, there were a lot of unexpected changes and uncertainty among the junior doctors especially the PGY1s (referring to interns)…”

“…COVID gives people much stress due to the uncertainty in a lot of things…” “the thought of COVID patients is scary” “…if I really contract this (COVID-19) I wouldn’t have too much concern (but) I was more scared I would pass it on to my family “…stress stemming from fear” “… cannot help but experienced feelings of isolation and loneliness… I avoided my mother, who is immunocompromised as I worry about passing the infection to her even when I am off active COVID-care duty…” “feeling of being protected alleviated stress and concerns related to contracting the virus” “…months during pandemic (in the posting) were enriching and enjoyable…” “working during pandemic is deemed as “a badge of honour” “felt the months during pandemic situation was a ‘good learning experience’”

|

|

Key Theme 2: Impact on Duties |

|

|

Sub-themes |

Sample of quotations |

|

a) Changes in clinical duties

b) Dealing with rapidly changing protocols

|

“felt that manpower shortage coupled with more frequent on-call duties within two weeks causes early burnout”

“…I think on the ground level the protocol is always bleak, for example who to swab and when…” “delayed updating of protocol online led to a bit of confusion” “not getting updated instantaneously and lack of accessible to the information” |

|

Key Theme 3: Impact on Teaching and Learning |

|

|

Sub-themes |

Sample of quotations |

|

a) Clinical exposure

b) Changes in teaching approaches |

“…in terms of the variety of cases in posting, it is significantly affected due to pandemic that changed demographic of attendees”

“…there wasn’t much teaching on-going until recently when we got the online platforms which I do feel is more helpful…” “due to having lesser patients, feels consultants have more time to teach” “while there is no group teaching, there is more teaching of cases on wards” |

|

Theme 4: Protective Measures and Support System |

|

|

Sub-themes |

Sample of quotations |

|

a) Rotation system which ensured sufficient manpower and rest

b) Institutional measures for personal protection against COVID-19 infection

c) Seniors, Peers and Staff support

d) Self-adaptability and resilience

|

“…we have enough manpower to actually toggle between the rotations for COVID-care and non-COVID services…”

“…PGY1s (Interns) are protected as we don’t swab the patients and we don’t have to expose ourselves to the possible aerolisation of the secretions, so I think that really protected us and relieved our stress…”

“… regular meetings (with) seniors that sat down to uncover our worries… seniors were open to taking feedback about rostering and manpower…” “…I really think it’s the support that has been given by the department and the institution, and the seniors especially have been very supportive…”

“…think of the hardships faced by other health professionals, one’s situation will not compare to theirs” “…stay strong, persevere, and that everyone will get through it together by supporting each other” “…remember that it was a choice and that it is also a privilege to be in medicine…” |

Table 2: Summary of key themes and sub-themes as well as verbatim quotations from our interns, from the group interviews.

1) Theme 1 – Psychological Impact (Feelings): Most interns perceived that the pandemic had caused drastic changes in their personal and work lives, with various psychological impacts. They expressed increased emotional exhaustion such as stress and burnout, that is mainly related to changes in their clinical duties (Theme 2). The interns also shared about risks of COVID-19 infection to self and especially to family and loved ones, increasing their worries and stress. Interns followed physical distancing measures and team segregation at work, but several interns avoided their loved ones at home, especially the elderly and immunocompromised. For these interns, they further shared feelings of isolation and loneliness. Positive emotions such as feeling secure, valued and protected existed simultaneously and were mainly associated with the protective measures and support systems (Theme 4) in the workplace. Some also reported that the posting was still enjoyable and felt proud to be working in the pandemic.

2) Theme 2 – Impact on Duties: The interns highlighted there were many changes in institutional work processes and their duties due to the pandemic. Due to manpower changes, there were pervasive reports of physical fatigue. There were however those who felt the workload was still manageable. Interns also raised the issue of non-timely information and unclear protocols which often led to confusion and uncertainty in their work.

3) Theme 3 – Impact on Teaching and Learning: There were mixed comments on this. As a result of strict physical distancing and team segregation, initial planned teaching sessions on general paediatrics were cancelled and the interns felt they “missed out” on their clinical training. Sessions were subsequently conducted using web-based platforms, which many found helpful. All interns felt that learning was restricted in the pandemic. Although it was beneficial to learn about pandemic response and management of suspected or affected COVID-19 patients, they felt their exposure to general paediatrics was reduced due to the limited variety of ward cases. However, there were some who felt there was better quality of teaching on the ward rounds as consultants had more time to teach with fewer elective and non-urgent cases in the rotations of non-COVID care.

4) Theme 4 – Preventive Measures and Support Systems: Despite the impacts on the interns’ psychology, duties and learning, they also shared on the various protective measures and support systems they perceived helped them cope. This was also the main reason for reported positive feelings of protection and support. Departmental and institutional work processes were implemented to take care of the interns’ physical and psychological welfare such as a rotational system of team segregation, which they reported provided a strict work-rest cycle as well as respite from COVID-care. In addition, seniors and faculty also ensured interns were competent and comfortable dealing with COVID-19 patients prior to taking on high risk duties such as swabbing patients. Support from multiple levels (seniors, department, institution) helped them through. In particular, the seniors and faculty provided support to the interns through regular “check-in” meetings where they could share concerns and provide feedback. The interns also shared that as a result of the strong support received, they were able to develop adaptability, perseverance and resilience, and they were even grateful to be in healthcare at this time.

IV. DISCUSSION

According to the demand-control-support model (Thomas, 2004), occupational stress causes burnout when job demands are high, individual autonomy is low and when job stress interferes with home life (Campbell et al., 2001; Linzer et al., 2001). On that note, we hypothesised that with the COVID-19 pandemic, interns would have increased stress and burnout, in addition to their routine difficulties in the transition from student to doctor. The pandemic-related concerns our interns had were similar to many healthcare workers globally – including the fear of contracting COVID-19 and more so transmitting it to vulnerable loved ones (Chen et al., 2020). Physical fatigue was also seen in our interns given the more intensive work schedule (Sasangohar et al., 2020). Although the total amount of admissions during the period was reduced to 40% of the usual load, the need for team segregation had led to a smaller pool of interns covering each clinical area. In addition, each intern had to do more in-house night calls while on active service. Segregation also meant that there would be less cross-coverage of duties where interns would receive less support from peers who would otherwise have been able to help with the workload on the ground. Another important aspect that had led to reported stress among many was the frequent changes in clinical workflows coupled with the lack of timely and reliable information (Wu et al., 2020). Many interns also highlighted concerns with regards to compromise and interference with their paediatric internship training (Liang et al., 2020). Despite all these, objectively the interns’ perceived stress was maintained without increase in burnout.

Burnout is known to be inversely related to resilience – this pattern is also reflected in our results. Resilience is the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or even significant sources of stress (Southwick et al., 2014). Our interns had high resilience scores, above what has previously been published among physicians (McKinley et al., 2020). One reason for this may be the development of resilience through a time of crisis, a phenomenon well encapsulated by the Crisis Theory: during a crisis or disequilibrium such as the current pandemic, people make attempts to adapt and seek solutions to restore stability. (Brooks et al., 2017; Caplan, 1964). The development of resilience is increasingly emphasised as an integral strategy to combat burnout. Potentially, the mitigating factors, coping mechanisms and support shared by our interns in the interviews, could explain their low burnout and high resilience.

Our interns perceived many systemic measures helped them cope with the pandemic – giving testament to the importance of institutional leadership in implementing safeguards for psychological health (Dewey et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Protocols relating to staff protection, availability of personal protective equipment (Rasmussen et al., 2020) were some of the measures common to institutions worldwide. Furthermore, interns being the most junior member of the team, were spared from doing aerosolising procedures such as intubation, nebulisation administration and airway suctioning that were deferred to clinicians with prior experience and training. This allowed interns time to learn and improve in their competency and confidence prior to assuming these responsibilities. The interns were also thankful for the protected work-rest cycles (Wu et al., 2020), and that they were allowed to take paid leave – which is essential, more so in the pandemic to reduce fatigue and allowed time for rejuvenation.

Other than institutional support, direct support from seniors and faculty were significant in our interns’ responses in helping them, supporting the importance of mentorship (Ramanan et al., 2006). Despite feeling that they might not have reliable and timely access to important updates, they felt supported under the direct guidance of seniors who took the lead on the ground. Regular fortnightly ‘check-in’ sessions were conducted to elicit concerns, obtain feedback, and ensure continual wellbeing. This channel of communication was well received by interns: they appreciated the faculty’s concerns, had the autonomy of being able to input and contribute to the care of patients, the opportunity to air grievances confidentially and importantly, had closure on concerns they have raised regarding their rotations and training (Fischer et al., 2019). The enhanced collegiality between interns, support from seniors and improved cooperation among healthcare workers during this time of crisis naturally also contributed to reduced burnout levels, a finding well established in literature.(Li et al., 2013)

In terms of the impact of training, teaching sessions were initially discontinued to maintain physical distancing. Moreover, the interns had a higher proportion of time spent in the provision of COVID-19 care, which meant traditional general paediatric exposure was compromised. However, within 4 weeks of the pandemic, departmental teaching activities were restored via web-based sessions which interns found useful. The role of faculty in persisting with academic continuity, is again important in mitigating the impact of the pandemic on learning – some interns felt they had more teaching on the wards as consultants had more time to teach for each patient.

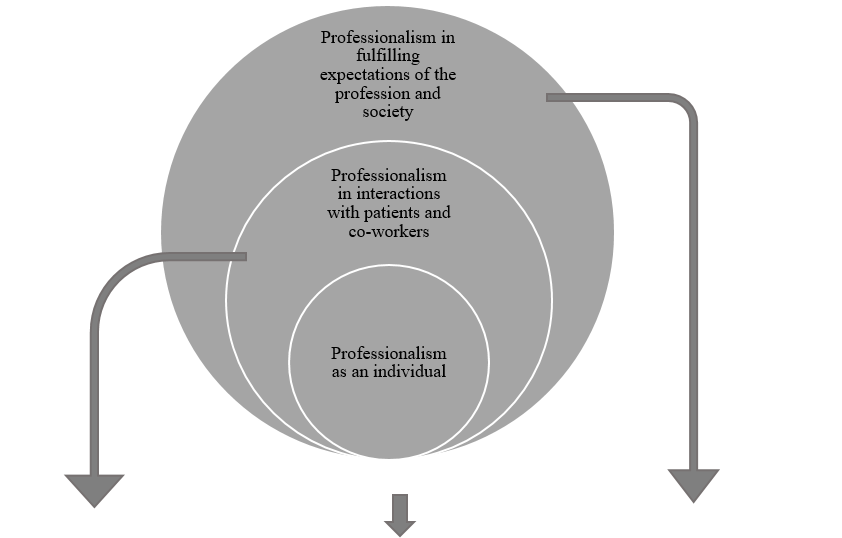

We believe that the perceived continual institutional and senior support for our interns allowed them to maintain high personal resilience, that could have mitigated their stress and burnout. In this pandemic, interns demonstrated adaptability and perseverance to the many changes, ability to persevere as well as finding gratitude amidst the challenges and focusing on their goal to help patients and fight the pandemic, which are all known features of resilience (Bird & Pincavage, 2016; Zwack & Schweitzer, 2013).

To our knowledge, this is the first research study in the pandemic that objectively evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 on interns’ psychological state, resilience and training. However, we recognise our study limitations. The small population would mean that it would be difficult to derive statistical comparisons in the pre- and post-exposure results. However, we believe the temporal exposure of the pandemic for this group of interns during their posting, made the pre- and post-pandemic results valid. The results were further supported by qualitative findings from a good group interview participation (100%) and in-depth discussion, that provided substantial explanations to the trend of results. We recognise that 2-4 months might be a short duration for negative psychological effects such as stress, and burnout to set in. Nonetheless, the amount of unprecedented changes and intensity of work for the interns involved within this period, were undoubtedly high. Another study limitation is the inclusion of Paediatric interns only and the possible lower exposure to COVID-19 as compared to their adult counterparts due to decreased disease morbidity and mortality in children. Although this factor could potentially result in less impact on the psychological factors studied, we believe other interns are likely to face similar concerns and challenges in the pandemic, due to their similar backgrounds and job scopes across most departments and disciplines.

This study elucidated the impact of the pandemic on interns in terms of their stress, burnout, as well as clinical duties and training. Despite increasing concerns on the psychological well-being of healthcare workers in the pandemic, our study has demonstrated that it is possible to mitigate their stress, burnout and preserve resilience, even in vulnerable new medical graduates. Our findings objectively validated the importance and effectiveness of the multi-faceted approach that target institution, faculty as well as the individual level, to build resilience and combat burnout in healthcare providers in this pandemic and beyond.

Notes on Contributors

Nicholas BH Ng contributed to conception and design of study, interpretation of data, drafting and critical revising of the article. Mae Yue Tan contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revising of the article. Shuh Shing Lee contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revising of the article. Nasyitah bte Abdul Aziz contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the article. Marion M Aw contributed to interpretation of data, drafting and critical revising of the article. Jeremy BY Lin contributed to conception and design, interpretation of data, drafting and critical revising of the article. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Data Availability

The data for this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12924029.v1. The access to these datasets are available for use subject to approval of the authors of this article.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the NHG Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB), with NHG DSRB reference number of 2020/00392.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the interns who participated in this study.

Funding

Funding for this study was obtained from NUHS Fund Limited – Medical Affairs (Education) Fund.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Bird, A., & Pincavage, A. (2016). A curriculum to foster resident resilience. MedEdPORTAL, 12, 10439. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10439

Brooks, S. K., Dunn, R., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., & Greenberg, N. (2017). Social and occupational factors associated with psychological wellbeing among occupational groups affected by disaster: A systematic review. Journal of Mental Health, 26(4), 373-384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294732

Campbell, D. A., Jr., Sonnad, S. S., Eckhauser, F. E., Campbell, K. K., & Greenfield, L. J. (2001). Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery, 130(4), 696-702; discussion 702-695. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.2001.116676

Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventive psychiatry. Basic Books.

Chen, Q., Liang, M., Li, Y., Guo, J., Fei, D., Wang, L., He, L., Sheng, C., Cai, Y., Li, X., Wang, J., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e15-e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30078-x

Chia, R., & Moynihan, Q. (2020, February 20). This alarming map shows where the coronavirus has spread in Singapore, one of the worst-hit areas outside of China Business Insider Singapore. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-singapore-map-shows-spread-worst-hit-outside-china-2020-2?IR=T.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 24(4), 385-396.

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76-82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Dewey, C., Hingle, S., Goelz, E., & Linzer, M. (2020). Supporting clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(11), 752-753. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1033

Fischer, J., Alpert, A., & Rao, P. (2019). Promoting intern resilience: Individual chief wellness check-ins. MedEdPORTAL, 15, 10848. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10848

Li, B., Bruyneel, L., Sermeus, W., Van den Heede, K., Matawie, K., Aiken, L., & Lesaffre, E. (2013). Group-level impact of work environment dimensions on burnout experiences among nurses: A multivariate multilevel probit model. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(2), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.001

Liang, Z. C., Ooi, S. B. S., & Wang, W. (2020). Pandemics and their impact on medical training: Lessons From Singapore. Academic Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003441

Linzer, M., Visser, M. R., Oort, F. J., Smets, E. M., McMurray, J. E., & de Haes, H. C. (2001). Predicting and preventing physician burnout: results from the United States and the Netherlands. The American Journal of Medicine, 111(2), 170-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00814-2

Low, Z. X., Yeo, K. A., Sharma, V. K., Leung, G. K., McIntyre, R. S., Guerrero, A., Lu, B., Lam, C. C. S. F., Tran, B. X., Nguyen, L. H., Ho, C. S., Tam, W. W., & Ho, R. C. (2019). Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091479

Maslach, C. J. S., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Maslach burnout inventory manual. Mind Garden Inc.

McKinley, N., McCain, R. S., Convie, L., Clarke, M., Dempster, M., Campbell, W. J., & Kirk, S. J. (2020). Resilience, burnout and coping mechanisms in UK doctors: A cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 10(1), e031765. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031765

Ministry of Health (MOH), Singapore. (2020). Circuit breaker to minimise further spread of COVID-19. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19. (Retrieved April 3, 2020)

Ng, N. B. H (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Paediatric Postgraduate Year One Doctors [Data set]. Figshare. https://figshare.com/s/74c81ca193638a553ea2

Ramanan, R. A., Taylor, W. C., Davis, R. B., & Phillips, R. S. (2006). Mentoring matters. Mentoring and career preparation in internal medicine residency training. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(4), 340-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00346.x

Rasmussen, S., Sperling, P., Poulsen, M. S., Emmersen, J., & Andersen, S. (2020). Medical students for health-care staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10234), e79-e80. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30923-5

Rotenstein, L. S., Torre, M., Ramos, M. A., Rosales, R. C., Guille, C., Sen, S., & Mata, D. A. (2018). Prevalence of burnout among physicians: A systematic review. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 320(11), 1131-1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12777

Sasangohar, F., Jones, S. L., Masud, F. N., Vahidy, F. S., & Kash, B. A. (2020). Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 131(1), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000004866

Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5,(1), 25338. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

Sturman, N., Tan, Z., & Turner, J. (2017). “A steep learning curve”: Junior doctor perspectives on the transition from medical student to the health-care workplace. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0931-2

Thomas, N. K. (2004). Resident burnout. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(23), 2880-2889. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.23.2880

Wu, P. E., Styra, R., & Gold, W. L. (2020). Mitigating the psychological effects of COVID-19 on health care workers. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(17), E459-e460. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200519

Zwack, J., & Schweitzer, J. (2013). If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Academic Medicine, 88(3), 382-389. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b

*Jeremy Bingyuan Lin

1E Kent Ridge Road,

NUHS Tower Block Level 12,

Singapore 119228

Tel: (65) 6772 4847

Email: jeremy_lin@nuhs.edu.sg

Submitted: 28 July 2020

Accepted: 18 November 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 48-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/OA2367

Oscar Gilang Purnajati1, Rachmadya Nur Hidayah2 & Gandes Retno Rahayu2

1Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana, Yogyakarta, Indonesia; 2Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction: Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) examiners come from various backgrounds. This background variability may affect the way they score examinees. This study aimed to understand the effect of background variability influencing the examiners’ score agreement in OSCE’s procedural skill.

Methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted with explanatory sequential design. OSCE examiners (n=64) in the Faculty of Medicine Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana (FoM-UKDW) took part to assess two videos of Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) competence to get their level of agreement by using Fleiss Kappa. One video portrayed CPR according to performance guideline, and the other portrayed CPR not according to performance guidelines. Primary survey, CPR procedure, and professional behaviour were assessed. To confirm the assessment results qualitatively, in-depth interviews were also conducted.

Results: Fifty-one examiners (79.7%) completed the assessment forms. From 18 background categories, there was a good agreement (>60%) in: Primary survey (4 groups), CPR procedure (15 groups), and professional behaviour (7 groups). In-depth interviews revealed several personal factors involved in scoring decisions: 1) Examiners use different references in assessing the skills; 2) Examiners use different ways in weighting competence; 3) The first impression might affect the examiners’ decision; and 4) Clinical practice experience drives examiners to establish a personal standard.

Conclusion: This study identifies several factors of examiner background that allow better agreement of procedural section (CPR procedure) with specific assessment guidelines. We should address personal factors affecting scoring decisions found in this study in preparing faculty members as OSCE examiners.

Keywords: OSCE Score, Background Variability, Agreement, Personal Factor

Practice Highlights

- The examiners’ background variability influences the OSCE scoring agreement results.

- The reason for assessment inaccuracy remains unclear regarding the score agreement.

- The absence of assessment instruments that could provide a loophole for examiners to improvise.

- Personal factors affecting scoring decisions found in this study should be addressed in preparing OSCE examiners.

I. INTRODUCTION

To assess medical students’ competencies in a variety of skills, most medical schools in Indonesia implement the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) both as a clinical skills examination at the undergraduate stage and as a national exit exam (Rahayu et al., 2016; Suhoyo et al., 2016). Most OSCE stations test both communication domains and specific clinical skills that will be assessed based on rubrics and scoring checklists which relies on examiners’ observations (Setyonugroho et al., 2015). The OSCE has a challenge in its complexity to standardise the scores, which are very depend on OSCE examiners’ perceptions (Pell et al., 2010). In a well-designed OSCE the examinees performance should only influence the examinees’ score, with minimal effects from other sources of variance (Khan et al., 2013). Research showed that there are influences of examiner’s background variability on OSCE results although they have been asked to standardise their behaviour (Pell et al., 2010) The decision and behaviour of OSCE examiners will affect the quality of assessment, including making a pass or fail decision, considering the complexity of knowledge, skill, and attitude in medical education (Colbert-Getz et al., 2017; Fuller et al., 2017).

Examiners’ observations also rely on their clinical practice experience, OSCE examining experience, and gender conformity (Mortsiefer et al., 2017). Even in OSCE that is held in the most standard conditions, the examiner factor has the biggest role in scoring inaccurately (Mortsiefer et al., 2017). However, the reason for this inaccuracy remains unclear since there are concerns regarding the scoring agreement of examiners in OSCE and how the result might be affected by this issue. There is a need to consider the influence of examiners’ background variability (gender, educational level, clinical practice experiences, length of clinical practice experiences, OSCE experience, and OSCE training experience) when preparing teachers as OSCE examiners. This study aimed to understand background variability as a factor influencing examiners’ scoring agreement in assessing students’ performance in procedural skill, as the first step of faculty development program to ensure the standard quality for examiners.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design

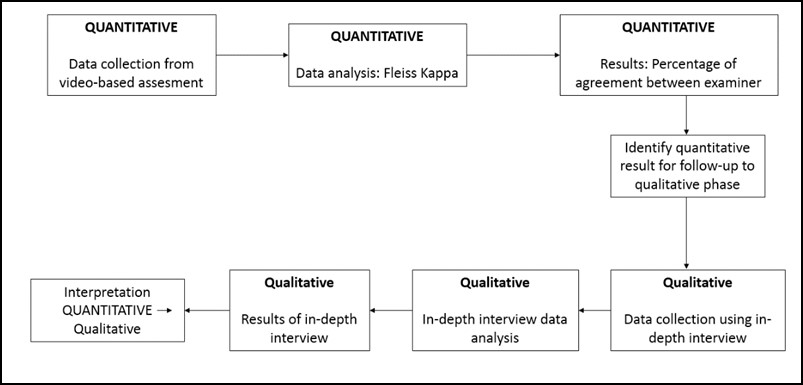

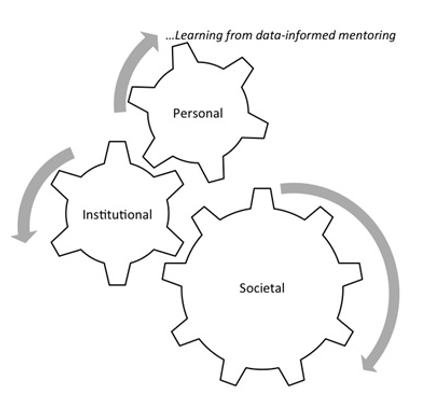

This mixed-method study used a sequential explanatory design. This mixed-method approach is expected to provide more comprehensive results and better understanding than using a separated method (Creswell & Clark, 2018).

This study comprised of 2 sequential phases of data collection and analysis (QUANTITATIVE: qualitative) using sequential design. First, quantitative data were collected as a cross-sectional study of the examiners’ strength of agreement using Fleiss Kappa while assessing the clinical skill performance recorded in the 2 videos: one video portrayed CPR according to performance guideline and the other portrayed CPR not according to performance guideline. We used these 2 videos in order to portray more comprehensively how the consistency of OSCE examiner agreement both on good and poor clinical skill performance.

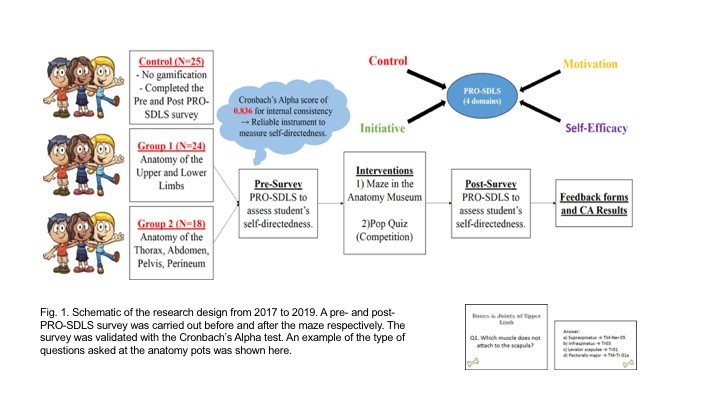

Figure 1 Mixed method explanatory design

In the second phase, in-depth interviews were used to complement the quantitative results to gain more information and a detailed confirmation about how the scores were decided (Stalmeijer et al., 2014). In this stage of study, researchers explored and explained the examiners’ OSCE experiences and behaviour when they give a score on a clinical skill examination and the influences on their scoring regarding their backgrounds.

B. Materials and/or Subjects

The strength of agreement of the videos’ score came from 64 OSCE examiners FoM UKDW. Mortsiefer et al., (2017), explained that more subjects are better when investigate examiner characteristics associated with inter-examiner reliability (Mortsiefer et al., 2017). In the second phase, in-depth interviews were conducted with 6 examiners of FoM UKDW, selected by purposive sampling regarding their scores and how they represented their own unique background (Table 1).

Researcher (OGP) provided all the participants with written information about this research and addressed ethical issues in an informed consent form. Researcher ensured participants understand the research protocol and clarified any questions regarding this study. Participants who agreed to take part, sign the informed consent form prior to the data collection.

We held interviews in FoM UKDW with maximum 30 minutes of duration each interview. The inclusion criteria for examiners who were selected for this study were involved as full-time faculty members, had over 4 times OSCE examination experience, and had done OSCE examiner training, expecting that they had enough interaction with other faculty members and had influences from medical doctor education (Park et al., 2015). The exclusion criteria were participant did not answer the research invitation and did not fill the assessment form completely. Main researcher (OGP) conducted the interview. Main researcher was a male, student of Master of Health Profession Education Universitas Gadjah Mada, and the staff of FoM UKDW.

C. Statistics

1)Quantitative data analysis: We grouped examiners into 18 groups based on their background which were gender, educational level, clinical practice experiences, length of clinical practice experiences, OSCE experience, and OSCE training experience as shown in Table 1. We analysed all gathered data using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and Microsoft Office Excel 365 (IBM Corp., Chicago). We presented quantitative data as a strength of agreement in percentage. The strength of agreement was calculated using Fleiss Kappa to determine the agreement between each group of each examiner background on whether CPR performances (primary survey, CPR Procedure, and professional behaviour), that portrayed in those 2 videos, were exhibiting score either “0”, “1”, “2”, or “3” based on the assessment guideline and rubric’s criteria (Purnajati, 2020). Based on recent research, agreement above 60% was considered as a substantial and adequate agreement (Stoyan et al., 2017; Vanbelle, 2019).

2) Qualitative data analysis: In-depth interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. We prepared a structured list of questions. It consisted of one key question: What was your experience in scoring the OSCE? The other additional questions evaluated the experiences of examiners in OSCE scoring including: the use of other references, differences in assessment weighting, use of own decision, clinical practice experience affecting the decision, and gender related decision making. Next, the collected data resulting from in-depth interviews were recorded using audio file recorder, read, and categorised into themes whenever they were related. The transcripts and identified themes were then given to an external coder in this study. This step was followed by our agreement for each theme. There was no repeated interview.

III. RESULTS

A. Quantitative Data Result

We deposited both quantitative and qualitative data in an online repository (Purnajati, 2020). The study participants in this quantitative phase were 64 OSCE examiners who are full-time faculty members. Twelve participants were excluded because did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Fifty-one (79.7%) examiners who returned the completed assessment form are described below in Table 1.

|

Quantitative Phase Participant |

|||

|

Background |

Groups |

Number of Participant (N=51) |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

22 (43%) |

|

|

Female |

29 (57%) |

||

|

Education |

Bachelor undergraduate |

19 (37%) |

|

|

Master’s degree |

16 (31%) |

||

|

Doctoral degree |

3 (6%) |

||

|

Specialist doctor |

13 (25%) |

||

|

Clinical Practice Experience |

General practitioner |

28 (55%) |

|

|

Specialist |

14 (27%) |

||

|

No clinical practice |

9 (18%) |

||

|

Duration of clinical practice experience |

< 2 years |

9 (18%) |

|

|

2-5 years |

17 (33%) |

||

|

>5 years |

25 (49%) |

||

|

OSCE experience |

< 2 years |

9 (18%) |

|

|

2-5 years |

24 (47%) |

||

|

>5 years |

18 (35%) |

||

|

OSCE examiner training |

< 3 times |

21 (41%) |

|

|

3-5 times |

17 (33%) |

||

|

>5 times |

13 (25%) |

||

|

Qualitative Phase Participants. |

|||

|

a Video portrayed CPR according to performance guideline. b Video portrayed CPR not according to performance guidelines |

|||

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of participants

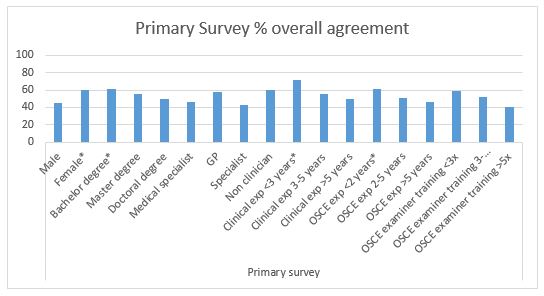

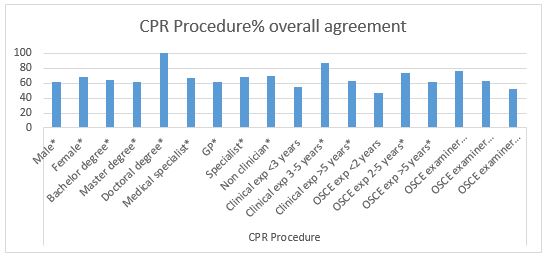

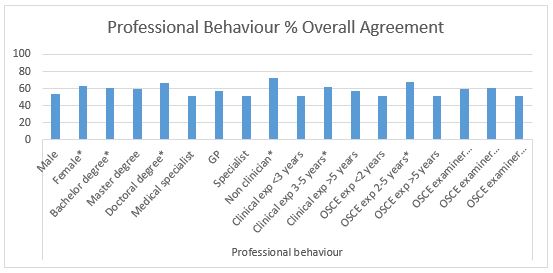

The assessment rubric was divided into three main competencies: (1) primary survey, (2) CPR procedure, and (3) professional behaviour. The results showed overall agreement on each main competency based on each examiners’ background variability by using Fleiss Kappa. The percentage of agreement is shown in Figure 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 2. Primary Survey percentage of overall agreement (n = 51). Agreement above 60% (*) is considered as a substantial and adequate agreement

Figure 3. CPR Procedure percentage of overall agreement (n=51). Agreement above 60% (*) is considered as a substantial and adequate agreement

Figure 4. Professional Behaviour percentage of overall agreement (n=51). Agreement above 60% (*) is considered as a substantial

After completing the CPR competency assessment, all examiners’ background characteristics met a cutoff of approval above 60% in assessing CPR procedure except for examiners with clinical practice experience <3 years, OSCE testing experience <2 years, and OSCE examiner training> 5 years (Figure 3). This finding showed a good strength of agreement in assessing CPR procedure regardless of examiners’ background. However, there were many instances where the cut-off point of 60% was not achieved in the aspects of primary surveys and professional behaviour (Figure 2 and 4), which showed fair strength of agreement between examiners when they examined these competencies.

B. Qualitative Data Results

Two theme categories were determined: (1) OSCE experience and (2) specific behaviour in OSCE. The first theme contains of 3 sub-themes: (1) student performance, (2) examiner background effect, and (3) using assessment instrument. The second theme consists of 5 sub-themes: (1) use of assessment references, (2) score weighting, (3) personal inferences, (4) clinical experience, and (5) gender conformity.

Theme 1: Examiners argued that they understand the difference in student performance in performing clinical skills and can distinguish from the coherent skills performed by students according to checklist.

“Very easy in giving an assessment, because everything is in accordance with the assessment rubric”

(ID 35)

“The plot is clear, well organised”

(ID 26)

“You can compare the inadequacies; it is enough to be compared”

(ID 11)

“The 2 different students are quite striking, so in my opinion it is not too difficult”

(ID 28)

Nevertheless, some examiners had difficulty to distinguish student performance when only used a checklist. Examiner background did not affect their way in scoring clinical skills performance, but some background may have the potential to affect their scoring, such as clinical practice experience.

“I am trying to avoid personal interpretations, as much as possible, but of course that cannot be 100 percent. In my opinion, the assessment rubric still gives room for subjectivity”

(ID 28)

In this research, it seemed easy for examiners to understand the assessment instrument when giving score to those 2 videos and their understanding were good.

Theme 2: Interviews revealed that: 1) Examiners use other references such as their clinical experience in assessing the skills;

“If the assessment guideline is unclear, the students are also unclear, yes I will improvise. Or when the assessment guideline is clear and the students are unclear which criteria are included, yes I will improvise”

(ID 35)

“Maybe yes, because once again the template at the beginning is not very clear”

(ID 23)

2) Examiners use different ways in giving weight of competence, for example, procedural steps are considered more important than primary survey;

“For those that I feel have a small weight because the instructions are also short, so I don’t have to look carefully”

(ID 24)

“When I feel that competence is not important, it does not get my emphasis, the more emergency that will get more attention.”

(ID 28)

3) The first impression of examinees might affect their decision in scoring their performance;

“That first impression will affect me in giving value. I will be more critical. I see more, pay more attention to the small things they do”

(ID 24)

4) Clinical practice experience drives examiners to establish a personal standard on how a doctor should be;

“Clinical experience when practice is one of the judgments”

(ID 24)

“The reference is just my instinct because it has been running as a doctor after all these years. Yes, I use my previous knowledge”

(ID 26)

And 5) Gender of examinees does not affect their decision, while their professionalism (e.g. showing respect to patients) will surely affect their decision.

“I pay more attention especially to politeness and professional behaviour”

(ID 24)

“Students of any gender still have the same standard of evaluation, a score of professionalism which is more influential”

(ID 23)

IV. DISCUSSION

Examiners’ agreement in this study was high in assessing the CPR procedure, which has a fixed and specific procedure in almost all groups of examiners. These results are consistent and can be explained by results from previous studies, which show that assessment with specific cases will provide high inter-examiner agreement (Erdogan et al., 2016). The differences in the examiner’s background will not have much influence on their agreement in giving an assessment in a specific case. This was supported by the opinions of examiners in the in-depth interviews who stated that in the CPR assessment procedure, assessment instruments are clear, easy to understand, with clear procedure flow, and performance that is easily distinguished, which made it easier for examiners to be able to distinguish student performance. A specific assessment instrument that could not provide a loophole for examiners to improvise assessment, made the opportunity for examiners to portray their subjectivity was minimised. This simplicity could lead to high agreement among examiners in specific competencies as shown in this study and based on clear evidence can increase the reliability of the assessment (Daniels et al., 2014) .

In this study, it was found in the primary survey assessment and professional behaviour which has an assessment guide that is not as specific as the CPR procedure, the percentage of agreement between examiner groups was lower, with only a few of them reaching 60% of agreement. This difference happened for reasons confirmed in the in-depth interviews which raised the issue that although the examiners tried to minimise their subjectivity in assessing, but it was said that there were still gaps in the assessment guide that still gives room for subjectivity. There are also examiners who were dissatisfied with the checklist, so they used their personal decisions in evaluating students.

According to a recent study, this could be due to the lack of specific instructions in the general assessment guidelines which will result in lower inter-examiner reliability compared to the use of more specific assessment guidelines (Mortsiefer et al., 2017). In the primary survey section and professional behaviour, there were also aspects of communication that were judged to be more susceptible to bias than physical examination skills because physical examination is more well-documented, clear instructions, and more widely accepted by examiners (Chong et al., 2018) The validity and reliability of a clinical skills assessment depend on factors including how the student’s performance on the exam, the character of the population, the environment, and even the assessment instrument itself can affect how examiners carry out the assessment (Brink & Louw, 2012). These phenomena were seen in the in-depth interviews which revealed that there were certain moments namely when the student being tested does not match the expectations written in the assessment guide and when the assessment guide is not clear so that it still gives room for subjectivity examiner. In addition, in the in-depth interviews the results also revealed that the examiners differentiated their attention on certain competencies with certain criteria such as the length of information in the assessment rubric, so that competencies that were considered not important did not get as much attention.

This finding may be in line with previous research which stated that constructs and conceptual definitions in this category that still provide a gap in the subjectivity of examiners cause shifting attention focus and weighting of their judgments to be different so that there are differences in important aspects between examiners (Schierenbeck & Murphy, 2018; Yeates et al., 2013). The difference in these important aspects can bring examiners to reorganise competency weights so that simpler and easier competencies (in this case those that have clearer and more detailed assessment guidelines) will be done first, and more complex ones (in this case, guides that have lower rigidity ratings) will be assessed later with the possibility of using more narratives (Chahine et al., 2015). This reorganisation can reflect how the examiners’ decision, allowing them to direct their attention to the more important aspects as the testers revealed in in-depth interviews with this research.

The personal factor, such as assessment references is a potential variability of the assessment conducted by the examiner. Examiners are trained and understand the use of assessment instruments, but produce varying assessments because they do not apply assessment criteria appropriately, but use personal best practice, use other test participants better as benchmarks, use patient outcomes (e.g. correct diagnosis, do patients understand, etc.), and use themselves as a comparison (Gingerich et al., 2014; Kogan et al., 2011; Yeates et al., 2013).

Another personal factors, including first impressions, can occur spontaneously unconsciously and can be a source of difference in judgment between examiners (Gingerich et al., 2011). First impressions based on observers’ observations have the same decisions and influences as social interactions, so it makes sense that first impressions are able to influence judgments, can be accurate and have a relationship with the final assessment results, but do not occur in examiners in general (Wood, 2014; Wood et al., 2017).

In providing assessments, there are gaps for examiners to give different competency weights to other examiners. Providing assessments based on targets that differ from competency standards and comparisons with the performance of other examinees will make the examiners recalibrate their own weighting and this is an explanation why there are variations in assessment and differences in the important points of the examinees’ performance among examiners (Gingerich et al., 2018; Yeates et al., 2015; Yeates et al., 2013).

The variability of personal factors between examiners can be conceptualise more as a different emphasis on building doctor-patient relationships and / or certain medical expertise rather than variations in the examiner’s background itself. The examiners’ own understanding can be conceptualized as a combination of whether what the examinees do is good enough and whether what they do is enough to build a doctor-patient relationship.

This research had some limitations such as it only used specific cases (i.e., CPR) to minimise the bias of the assessment instrument so that it would reveal more bias in the examiners themselves. In more complicated cases such as communication skills and clinical reasoning it is also necessary to provide a more complete picture of how the examiners’ scores agree in other cases. Generalization also became a limitation in this study because it only involved examiners from one medical education institution, however the study participants sufficiently described the variability of the examiner’s background.

V. CONCLUSION

This study identifies several factors of examiner background variability that influence examiners’ judgment in terms of inter-examiner agreement. Female examiners, bachelor education, less OSCE experience, and non-clinician examiners allow better agreement of procedural section (CPR procedure) with specific assessment guidelines. Cases that have unspecified assessment guidelines in this research, primary survey and professional behaviour, have lower agreement among examiners and must be examined deeper. We should note that personal factors of OSCE examiners can influence assessment discrepancies. However, the reasons for using these personal factors in scoring OSCE performance might be affected by unknown biases that require further research. Therefore, to improve clinical skills assessment such as OSCE for undergraduate medical programme, we must address personal factors affecting scoring decisions found in this study in preparing faculty members as OSCE examiners.

Notes on Contributors

Oscar Gilang Purnajati, MD was student of Master of Health Professions Education Study Program, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. He concepted the research, reviewed the literature, designed the study, acquisited funding, conducted interviews, analysed quantitative data and transcripts, and wrote the manuscript.

Rachmadya Nur Hidayah, MD., M.Sc., Ph.D is lecturer of Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She supervised author Oscar Gilang Purnajati, developed the concepted framework for the study, critically analysed the data, cured the data, and reviewed the final manuscript.

Prof. Gandes Retno Rahayu, MD., M.Med.Ed, Ph.D is professor at the Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She supervised author Oscar Gilang Purnajati, advised the design of the study, critically analysed the data, gave critical feedback to the conducted interviews, reviewed the final manuscript.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by Health Research Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana (Reference No.1068/C.16/FK/2019).

Data Availability

All data were deposited in an online repository. The data is available at Open Science Framework with DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RDP65

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Hikmawati Nurrokhmanti, MD, M.Sc for helping with the process of coding the in-depth interview transcripts. The author also would like to thank the staffs of Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana for supporting the research.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana (No. 075/B.03/UKDW/2018) as a part of study scholarship.

Declaration of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Abbreviations and specific symbols

OSCE: Objective Structured Clinical Examination.

References

Brink, Y., & Louw, Q. A. (2012). Clinical instruments: Reliability and validity critical appraisal. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice,18(6), 1126-1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01707.x

Chahine, S., Holmes, B., & Kowalewski, Z. (2015). In the minds of OSCE examiners: Uncovering hidden assumptions. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 21(3), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9655-4

Chong, L., Taylor, S., Haywood, M., Adelstein, B.-A., & Shulruf, B. (2018). Examiner seniority and experience are associated with bias when scoring communication, but not examination, skills in objective structured clinical examinations in Australia. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 15(17). https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2018.15.17

Colbert-Getz, J. M., Ryan, M., Hennessey, E., Lindeman, B., Pitts, B., Rutherford, K. A., Schwengel, D., Sozio, S. M., George, J., & Jung, J. (2017). Measuring assessment quality with an assessment utility rubric for medical education. MedEdPORTAL : The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, 13, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10588

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed method research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Daniels, V. J., Bordage, G., Gierl, M. J., & Yudkowsky, R. (2014). Effect of clinically discriminating, evidence-based checklist items on the reliability of scores from an internal medicine residency OSCE. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 19(4), 497-506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-013-9482-4

Erdogan, A., Dong, Y., Chen, X., Schmickl, C., Berrios, R. A. S., Arguello, L. Y. G., Kashyap, R., Kilickaya, O., Pickering, B., Gajic, O., & O’Horo, J. C. (2016). Development and validation of clinical performance assessment in simulated medical emergencies: An observational study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-015-0066-x

Fuller, R., Homer, M., Pell, G., & Hallam, J. (2017). Managing extremes of assessor judgment within the OSCE. Medical Teacher, 39(1), 58-66. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1230189

Gingerich, A., Kogan, J., Yeates, P., Govaerts, M., & Holmboe, E. (2014). Seeing the ‘black box’ differently: Assessor cognition from three research perspectives. Medical Education, 48(11), 1055–1068. https://doi.org /10.1111/medu.12546

Gingerich, A., Regehr, G., & Eva, K. W. (2011). Rater-based assessments as social judgments: Rethinking the etiology of rater errors. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86(10), S1-S7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822a6cf8

Gingerich, A., Schokking, E., & Yeates, P. (2018). Comparatively salient: Examining the influence of preceding performances on assessors’ focus and interpretations in written assessment comments. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 23(5), 937-959. https://doi.org /10.1007/s10459-018-9841-2

Khan, K. Z., Ramachandran, S., Gaunt, K., & Pushkar, P. (2013). The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE): AMEE Guide No. 81. Part I: An historical and theoretical perspective. Medical Teacher, 35(9), 1437-1446. https://doi.org/ 10.3109/0142159X.2013.818634

Kogan, J. R., Conforti, L., Bernabeo, E., Iobst, W., & Holmboe, E. (2011). Opening the black box of clinical skills assessment via observation: A conceptual model. Medical Education, 45(10), 1048-1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04025.x

Mortsiefer, A., Karger, A., Rotthoff, T., Raski, B., & Pentzek, M. (2017). Examiner characteristics and interrater reliability in a communication OSCE. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(6), 1230-1234. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pec.2017.01.013

Park, S. E., Kim, A., Kristiansen, J., & Karimbux, N. Y. (2015). The Influence of Examiner Type on Dental Students’ OSCE Scores. Journal of Dental Education, 79(1), 89-94.

Pell, G., Fuller, R., Homer, M., & Roberts, T. (2010). How to measure the quality of the OSCE: A review of metrics – AMEE guide no. 49. Medical Teacher, 32(10), 802-811. https://doi.org/ 10.3109/0142159X.2010.507716

Purnajati, O. G. (2020). Does objective structured clinical examination examiners’ backgrounds influence the score agreement? [Data set]. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/ 10.17605/OSF.IO/RDP65

Rahayu, G. R., Suhoyo, Y., Nurhidayah, R., Hasdianda, M. A., Dewi, S. P., Chaniago, Y., Wikaningrum, R., Hariyanto, T., Wonodirekso, S., & Achmad, T. (2016). Large-scale multi-site OSCEs for national competency examination of medical doctors in Indonesia. Medical Teacher, 38(8), 801-807. https://doi.org /10.3109/0142159X.2015.1078890

Schierenbeck, M. W., & Murphy, J. A. (2018). Interrater reliability and usability of a nurse anesthesia clinical evaluation instrument. Journal of Nursing Education, 57(7), 446-449. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20180618-12

Setyonugroho, W., Kennedy, K. M., & Kropmans, T. J. B. (2015). Reliability and validity of OSCE checklists used to assess the communication skills of undergraduate medical students: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(12), 1482-1491. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.004

Stalmeijer, R. E., McNaughton, N., & Van Mook, W. N. (2014). Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Medical Teacher, 36(11), 923-939. https://doi.org/ 10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165

Stoyan, D., Pommerening, A., Hummel, M., & Kopp-Schneider, A. (2017). Multiple-rater kappas for binary data: Models and interpretation. Biometrical Journal, 60(5), 381-394. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bimj.201600267

Suhoyo, Y., Rahayu, G. R., & Cahyani, N. (2016). A national collaboration to improve OSCE delivery. Medical Education, 50(11), 1150–1151. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/medu.13189

Vanbelle, S. (2019). Asymptotic variability of (multilevel) multirater kappa coefficients. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 28(10-11), 3012-3026. https://doi.org /10.1177/0962280218794733

Wood, T. J. (2014). Exploring the role of first impressions in rater-based assessments. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 19(3), 409-427. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10459-013-9453-9

Wood, T. J., Chan, J., Humphrey-Murto, S., Pugh, D., & Touchie, C. (2017). The influence of first impressions on subsequent ratings within an OSCE station. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 22(4), 969-983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9736-z

Yeates, P., Moreau, M., & Eva, K. (2015). Are examiners’ judgments in osce-style assessments influenced by contrast effects? Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 90(7), 975-980. https://doi.org /10.1097/ACM.0000000000000650

Yeates, P., O’Neill, P., Mann, K., & Eva, K. (2013). Seeing the same thing differently: Mechanisms that contribute to assessor differences in directly-observed performance assessments. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 18(3), 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-012-9372-1

*Oscar Gilang Purnajati

Faculty of Medicine,

Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana,

Jl. Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo No. 5-25.

Yogyakarta City,

Special Region of Yogyakarta

55224, Indonesia.55224, Indonesia.

Tel: +62-274-563929

Email: oscargilang@staff.ukdw.ac.id

Submitted: 8 July 2020

Accepted: 23 October 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 38-47

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/OA2338

Enjy Abouzeid1, Rebecca O’Rourke2, Yasser El-Wazir1, Nahla Hassan1, Rabab Abdel Ra’oof1 & Trudie Roberts2

1Faculty of Medicine, Ismailia, Egypt; 2LIME, University of Leeds, United Kingdom

Abstract

Introduction: Although, several factors have been identified as significant determinants in online learning, the human interactions with those factors and their effect on academic achievement are not fully elucidated. This study aims to determine the effect of self-regulated learning (SRL) on achievement in online learning through exploring the relations and interaction of the conception of learning, online discussion, and the e-learning experience.

Methods: A non-probability convenience sample of 128 learners in the Health Professions Education program through online learning filled-out three self-reported questionnaires to assess SRL strategies, the conception of learning, the quality of e-Learning experience and online discussion. A scoring rubric was used to assess the online discussion contributions. A path analysis model was developed to examine the effect of self-regulated learning on achievement in online learning through exploring the relations and interaction among the other factors.

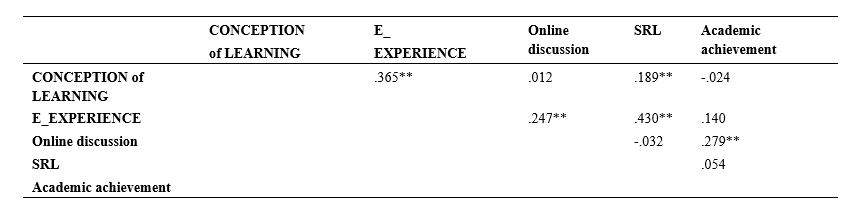

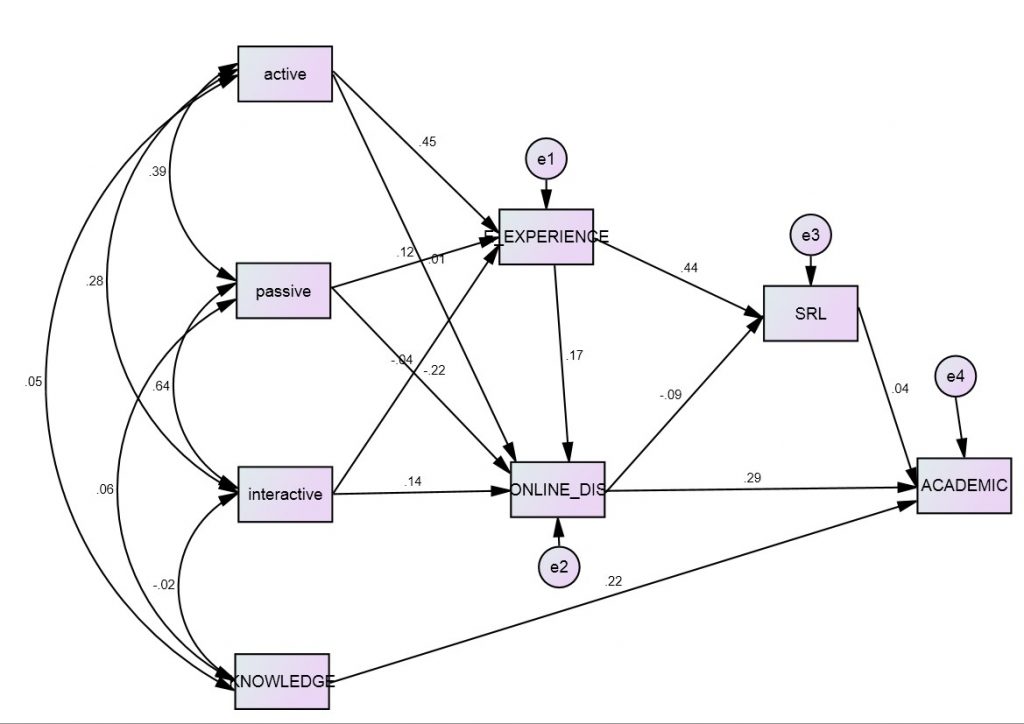

Results: Path analysis showed that SRL has a statistically significant relationship with the quality of e-learning experience, and the conception of learning. On the other hand, there was no correlation with academic achievement and online discussion. However, academic achievement did show a correlation with online discussion.

Conclusion: The study showed a dynamic interaction between the students’ beliefs and the surrounding environment that can significantly and directly affect their behaviour in online learning. Moreover, online discussion is an essential activity in online learning.

Keywords: Online Learning, Conception of Learning, E-learning Experience, Human-Computer Interface, Self-regulated Learning, Path Analysis

Practice Highlights

- The learner who views learning as a constructive process will show better use of self-regulated learning strategies.

- Learners’ beliefs and perceptions can shape the learning experience.

- Online discussion can directly and significantly affect academic achievement in online learning.

- Self-regulated learning is responsible for a small portion of the change in academic achievement.

- Online discussion may affect self-regulated learning negatively.

I. INTRODUCTION

In just a few years, online e-learning has become part of the mainstream in medical education for postgraduates in both developed and developing countries. The use of online e-learning may provide solutions for many educational problems, especially for health professions graduates. It can help them achieving their developmental and educational goals despite the lack of time and overburdened schedules. This raised the need for better understanding of learning in online learning context.

The training that most schools offer to students and instructors on online leaning is mainly limited to using technologies that allow learners to interact with instructors and other learners effectively and flexibly. However, learners in online learning are facing several and complex challenges due to the nature of this context. Online learning is a form of distance learning that represent not only the access to learning experience via the use of technology and internet but also it relies on connectivity, flexibility and ability to promote varied interactions (Hiltz & Turoff, 2005). It characterised by autonomy and relative isolation due to the lack of face-to-face support. One of these important challenges is the need for self-regulated skills. It has been reported that these skills are more important in online learning as compared to traditional one (Azevedo et al., 2008).

Self-regulation is defined as the degree to which students are metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviourally active participants in their learning process (Zimmerman, 1986). This definition focused on students’ proactive use of specific behaviours to improve their academic achievement. In short, the ability to regulate one’s learning process is a critical skill to achieve personal learning objectives in online courses due to the absence of the support and guidance that is typically available in face-to-face learning environments (e.g., an instructor setting deadlines and structuring the learning process). Therefore, online learners need to determine when and how to engage with course content without any other support than the course content and structure, which can pose a challenge for many learners (Lajoie & Azevedo, 2006).

Hence, it seems reasonable to assume that SRL may be a reliable predictor of academic performance. It has been shown that self-regulated learners are more effective learners (Toering et al., 2012), who attain higher grades in medical education (Lucieer et al., 2016). However, the effect of SRL on academic achievement in online learning is still unclear.

Several factors may interact and affect learning in online learning. However, some had received only limited discussion in the medical education literature while others had relatively little empirical testing. Although several research studies have investigated the effect of conception of learning on learners’ approaches, efforts, and motivation, however the effect of conception of learning on self-regulation is still insufficiently explored. Moreover, it can be assumed that students in online learning context may show different conceptions of learning as studies have shown that conception of learning is a context-depended construct that may differ according to the domain of the study or the surrounding context (Chiu et al., 2016; Tsai & Tsai, 2014). Additionally, SRL processes depend on both the learner and the surrounding environment (Bembenutty, 2006). As a result, we assumed that the learners’ perception of the quality of the surrounding learning environment might directly affect their behaviour and outcomes. In other words, the quality and interactivity of the learning environment may shape the learners’ attitude towards the learning experiences and influence the behavioural control of the learner (Zhao, 2016).

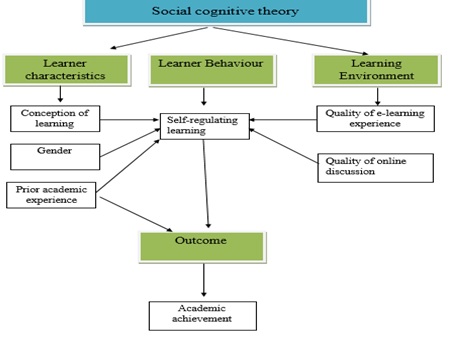

Figure 1: The study conceptual framework

Therefore, a model was hypothesized to explore the interaction between self-regulated learning, the conception of learning, online discussion, and the e-learning experience in an online environment, and how this interaction may affect academic achievement. This cross-sectional study provides an exciting opportunity to advance our knowledge about the learning process in online learning by raising the following questions:

- What is the relationship between SRL and academic achievement in online learning?

- What are the interactions between personal characteristics, beliefs, behaviours, and environment in online learning?

- Does these interactions affect academic achievement in online learning?

II. METHODS

A. Type of the Study and Setting

An observation cross-sectional study was performed at the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt. The Medical Education Department offers postgraduate online learning programs in Medical Education to the graduates of Health Professions Education specialties. The program is one of the first online programs in health professions education in the Arab region. It is a two-year program in which students submitted weekly assignments through WordPress / Eleum and receive online feedback on the same Learning Management system (LMS). Also, participate in an online discussion forum through the web-based application Listserv on Google group.

B. Participants and Sampling

‘Out of 231 learners in the online program, a non-probability convenience sample of 128 learners was recruited in the current study; of which, 88 participants had an input in the online discussion’. The subjects were selected from all the program fellows based on their approval to be included in the study sample. The participants were asked to participate in the study through a mass email composed of a detailed description of the nature of the study, the purpose of the study and its relevance to the field of medical education. In all cases, fellows were informed that any information they included in the questionnaires would be treated with confidentiality.

C. Data Collection Tools

Instruments were selected in the current study because it was constructed and used in relevant contexts and the design of the final version of the questionnaires were validated using factor; reliability and test- retest analysis.

1) Measuring learners’ self-regulated learning: The Online Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (OSLQ) was used to measure the self-regulated learning behaviours of the fellows (Barnard et al., 2008). The OSLQ consists of six subscale constructs including: environment structuring; goal setting; time management; help seeking; task strategies; and self-evaluation.

2) Measuring learners’ conception of learning: The mental model section of the Inventory of Learning Style (ILS) was used to explore the learners’ conception of learning. The questionnaire was kindly provided by J.D. Vermunt, who originally developed this inventory (Vermunt, 1998). The conception of learning section is composed of 25 items categorised under five scales: construction of knowledge, intake of knowledge, use of knowledge, stimulating education & cooperation of learning.

3) Measuring of the quality of e-learning experience: The e-Learning Experience Questionnaire was used to explore the role of the learning environment (Ginns & Ellis, 2007). The questionnaire consisted of subscales which would reflect students’ perceptions of Good Teaching, Good Resources Clear Goals and Standards, Appropriate Assessment, Generic skills, Appropriate Workload and student interaction.

4)Online discussion: The assessment of the fellows’ input in the online discussion was done by using a scoring rubric that was included in a framework proposed by Nandi et al. (2009). This framework defines several themes on which qualitative online interaction can be designed and assessed. The scoring rubric composed of three broad categories: content, interaction quality and participation.