Online medical interview training in preclinical medical education: Educational outcomes comparable to face-to-face training

Submitted: 24 October 2024

Accepted: 5 July 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 26-34

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/OA3552

Shoko Horita1,2, Masashi Izumiya2, Satoshi Kondo2,3,4, Junki Mizumoto2,5,6, Hiroko Mori6,7 & Masato Eto2

1Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, Teikyo University, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan; 2Department of Medical Education Studies, International Research Centre for Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan; 3Department of Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan; 4Center for Medical Education and Career Development, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan; 5Department of Family Practice, Ehime Seikyo Hospital, Matsuyama, Ehime, Japan; 6Center for General Medicine Education, School of Medicine, Keio University, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan; 7Professional Development Centre, The University of Tokyo Hospital, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Abstract

Introduction: Conventionally, face-to-face education has been prevalent in medical education because it can help medical students learn interpersonal skills, including medical interviews and physical examination. However, because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, face-to-face education was suspended to prevent the spread of the infection. As face-to-face classes in Japan were discontinued when the pandemic began in the spring of 2020, we developed an online education program to develop medical interview skills. We were interested in determining the educational outcomes between face-to-face and online medical interview classes. Therefore, we compared them before and after the pandemic.

Methods: Fourth-year students of the University of Tokyo Medical School took medical interview classes. Under consent, the score of the medical interview area of the preclinical clerkship, Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), as a high-stakes examination, which falls at the top level of the Kirkpatrick’s model, was compared by year or before and after the pandemic.

Results: The online group showed higher item-wise scores of the medical interview of the preclinical clerkship OSCE than the face-to-face group. In terms of the global score, no significant difference was observed. In the computer-based test (CBT), the online group had higher scores compared with the face-to-face group.

Conclusion: The educational outcomes of online medical interview classes were not inferior to those of conventional face-to-face classes, as revealed by high-stakes examination preclinical clerkship OSCE. Similar to face-to-face education, online education is a viable option for developing interpersonal skills.

Keywords: COVID-19 Pandemic, Medical Interview, OSCE, Educational Outcome, Online Education, Interpersonal Skills, Communication Skills

Practice Highlights

- Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we shifted medical interview classes from face-to-face to online.

- The online group had interview global OSCE scores non-inferior to those of the face-to-face group.

- The online group had higher interview elementary OSCE scores than the face-to-face group.

I. INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic severely restricted face-to-face teaching and affected almost all levels and fields of education, including undergraduate preclinical medical education (Bastos et al., 2022; Crawford et al., 2020). Moreover, it resulted in drastic changes in medical education. Globally, face-to-face learning was forcibly discontinued as part of infection control. Thus, to continue medical education, online or remote learning was rapidly introduced (Daniel et al., 2021; Gordon et al., 2020). Various instrumental trans communication devices, including video conferencing tools, simulation, virtual reality, and augmented reality, were used to facilitate online learning. However, this rather hasty shift from face-to-face to online learning brought some confusion into the field of medical education. In the UK, Dost et al. (2020) reported that medical students were unsatisfied with online classes compared with face-to-face classes.

Globally, tele-education is increasingly being encouraged around the world (American Medical Association, 2016). In the field of medical interview (Budakoğlu et al., 2021; Hammersley et al., 2019; Zaccariah et al., 2022), telemedicine is gradually becoming common, showing favourable results. However, because of technical problems, tele-education did not spread smoothly (Zaccariah et al., 2022). Additionally, the educational outcomes of both strategies have not been satisfactorily studied (Khamees et al., 2022). Recently, some reports showing that the educational outcome of online classes are equal or more effective than traditional face-to-face education, however, they are restricted mainly in knowledge-based education (Alshaibani et al., 2023; Basuodan, 2024; Saad et al., 2023). Furthermore, few studies have compared high-stakes examination, including the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), and no study has compared the educational results between face-to-face classes and tele-education (online) using the top level of Kirkpatrick’s model (Kirkpatrick, 1996).

The OSCE (Harden et al., 1975) has been widely accepted as a form to assess clinical performance in medical education. Currently, OSCEs are used worldwide to appraise medical students’ communication and clinical skills. Various educational methods have been evaluated using OSCE as one of the indicators of educational outcomes (Guetterman et al., 2019). In Japan, passing the preclinical clerkship (pre-CC) OSCE has become legally obligatory as one of the elements for promotion to the CC course since the spring of 2023. In 2023, the pre-CC OSCE in Japan is conducted in at least eight areas, which are medical interview, “Basic Clinical Procedure”, “Basic Life Support”, and physical examinations of “head and neck”, “chest”, “vital signs”, “abdomen”, and “neurological examinations”.

In the present study, we aimed to determine the educational outcomes between face-to-face and online medical interview classes. We provided medical interview classes to fourth-year medical students before taking the pre-CC OSCE, face-to-face classes before 2019, and tele-education (online) after 2020. We decided to conduct research in medical interview, other than the other areas of the pre-CC OSCE, because of the importance of the medical interview as the basis of medical practice. Moreover, it was inevitable that the medical interview classes had to be implemented as online classes to protect the simulated patients form the risk of infection, which was another main reason for selecting medical interview for this research. In another point of view, medical interview classes were able to implement via online. As mentioned above, no prior studies have compared face-to-face and online medical interview training using both high-stakes OSCE score and Kirkpatrick’s top-level outcomes, our study would have significant importance.

II. METHOD

A. Participants

This study was approved in 2021 by the ethics committee of the University of Tokyo (UTokyo) Faculty of Medicine (Approval No. 2021005NI). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Moreover, the data of students who provided consent for the secondary use of their data (Approval No. 11763) in another research approved in 2017 were included.

B. Sample Population

Students in the UTokyo Faculty of Medicine were asked if they were willing to participate in “A Study of the Educational Effectiveness of Online “Medical interviewing Practice” in the post-class reflection questionnaire of the “Online medical interview classes or the waiting period after the pre-CC OSCE. Out of 229 students (2021 and 2022), 87 students participated in this study. A summary of the annual participants is shown in Appendix 1. In early 2020 almost all the classes in UTokyo were stopped due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it difficult to contact students face-to-face and to obtain participants in the previous research (Approval No. 11763); and as this research started in 2021, it was practically difficult to obtain consent to participate in this study in 2020. In 2020 the online medical interview classes have just been launched, which significantly improved in 2021. Hence, we thought that it would be better to exclude the small participants of 2020 from the analysis to keep the validity of this study.

C. Details of Medical Interview Classes

Before 2019, the medical interview classes were performed as follows: Early in their fourth year, students joined classes introducing the outline of medical interview. A few days before the class, students watched an instructional video of a medical interview performed by the Common Achievement Tests Organization (CATO) (2005) in Japan. Afterward, students in a group of eight to nine faced the simulated patient in a classroom in the UTokyo and performed a medical interview roleplay. Thereafter, feedback about the technical factor of the medical interview as well as rapport status and nonverbal communications such as faces and gesture was provided by the students themselves, other students, simulated patients, and teachers. Since 2020, most face-to-face classrooms, including those in the present study, were closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic and were replaced with online classes. The present face-to-face class was also held online with the simulated patients and teachers using Zoom(R). Using the “Close-Up” function of Zoom(R), the simulated patient and student were faced with each other, whereas other participants (e.g., other students, other simulated patients, and the teacher) were not on the television (Appendix 2). After the roleplay was over, all students and the teacher came back on the television and provided feedback to the student, similar to face-to-face classes. Moreover, the class was recorded using the function of Zoom(R) and provided to students exclusively for review. After the class students reflected on the reflection sheet (until 2019) or the Learning Management System (from 2020) which was reviewed and commented on by teachers. The contents of the reflections were used for this study to investigate the impressions of the students.

D. Pre-CC OSCE and Computer-Based Test (CBT)

In Japan, medical students usually take the pre-CC OSCE in the fourth year, prior to the two-year CC course. Before 2022, the minimum assessment factors were medical interview, physical examinations (including head and neck, chest, abdomen, neurological examinations), basic clinical procedure, and basic life support. The examinations were administered by CATO. The evaluation criteria are not publicly available because of CATO policy. Two scores are used in the evaluation: global score (GS) which means the evaluation as a total performance and item-wise score (IS) which means scores by checklist. Before 2023, the borderline was set by each institute. At least one certified evaluator per area was responsible, and each evaluator was a faculty member. Moreover, CATO sent at least one external evaluator per area and an external supervisor. After each performance, each examinee was evaluated by two or three evaluators per room. The pre-CC OSCE is one of the examinations that students must pass to proceed to the CC course.

Aside from the pre-CC OSCE, students must also pass the CBT. The CBT corresponds to the assessment of medical knowledge prior to the CC (Horita et al., 2021). In 2023, the pre-CC OSCE and CBT have been made official, and students must pass both examinations before they can take the national board examination in Japan.

E. Data Analysis

The pre-CC OSCE scores were analysed using R, Rstudio, JMP version17.0 (SAS Institute, N.C., USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, W.A., USA). Non-paired T test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Steel-Dwass test were used respectively, for parametric or non-parametric comparisons.

III. RESULTS

A. Year-to-Year Comparison of the Pre-CC OSCE Results in the Medical Interview area and CBT Results

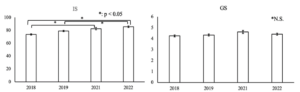

First, we compared the year-to-year results of the pre-CC OSCE in the medical interview area. Table 1 and Figure 1 shows a statistical summary of the pre-CC OSCE scores in 2022, 2021, 2019, and 2018. The results of non-parametric tests revealed that the p-values in the IS between 2022 and 2019, 2022 and 2018, and 2021 and 2018 were below 0.05, whereas no significant difference was observed in the GS.

|

Year |

IS/GS |

Average |

SD |

SE |

Bottom 95 |

Upper 95 |

|

2022 |

IS |

85.67 |

9.19 |

1.18 |

83.32 |

88.02 |

|

GS |

4.41 |

0.68 |

0.09 |

4.24 |

4.58 |

|

|

2021 |

IS |

82.69 |

9.71 |

1.90 |

78.77 |

86.61 |

|

GS |

4.62 |

0.75 |

0.15 |

4.31 |

4.92 |

|

|

2019 |

IS |

79.04 |

10.19 |

1.07 |

76.92 |

81.16 |

|

GS |

4.33 |

0.89 |

0.09 |

4.14 |

4.51 |

|

|

2018 |

IS |

73.63 |

9.94 |

1.10 |

71.43 |

75.83 |

|

GS |

4.26 |

0.79 |

0.09 |

4.09 |

4.44 |

Table 1. Averages of IS and GS of the medical interview area per the pre-CC OSCE implementation year. IS, item-wise score; GS, global score; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error

Figure 1. Average of IS and GS. The error bar shows standard error

|

Year |

Average |

SD |

SE |

Bottom 95 |

Upper 95 |

|

2022 |

566.62 |

121.03 |

15.50 |

535.63 |

597.62 |

|

2021 |

576.07 |

106.64 |

20.52 |

533.89 |

618.26 |

|

2019 |

565.02 |

119.91 |

12.71 |

539.76 |

590.28 |

|

2018 |

529.72 |

116.34 |

12.93 |

503.99 |

555.44 |

Table 2. Year-by-year score distribution of CBT (IRT score)

B. Comparison Before and After the Pandemic

The medical interview classes were held face-to-face before the pandemic (2018 and 2019) and online after the pandemic (2021 and 2022). We compared the results of pre-CC OSCE medical interview and CBT before and after the pandemic. A summary of the results is shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. The results of statistical analyses revealed a significant difference in the medical interview IS and CBT between the face-to-face group and the online group (p < 0.001 and 0.032 respectively). However, no significant difference in GS was observed.

|

|

Group |

Number |

Average |

SE |

Bottom 95 |

Upper 95 |

|

OSCE (medical interview) IS |

F-to-F |

164 |

76.18 |

0.79 |

74.62 |

77.74 |

|

online |

85 |

84.71 |

1.10 |

82.54 |

86.87 |

|

|

OSCE (medical interview) GS |

F-to-F |

164 |

4.28 |

0.06 |

4.15 |

4.40 |

|

online |

85 |

4.47 |

0.09 |

4.30 |

4.64 |

|

|

CBT (IRT score) |

F-to-F |

162 |

546.5 |

9.39 |

528.1 |

565.0 |

|

online |

86 |

569.7 |

12.9 |

544.3 |

595.1 |

Table 3. Comparison of pre-CC OSCE (IS and GS respectively) and CBT results between the face-to-face (F-to-F) group and the online group

Figure 2. Comparison of pre-CC OSCE (IS and GS respectively) and CBT results between the face-to-face (F-to-F) group and the online group. The error bar shows standard error.

IV. DISCUSSION

We found no significant negative effects in some of the important educational outcomes in medical students’ scores of the medical interview due to online education caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The quality of the medical interview after the emergence of the pandemic was no less than that before the pandemic. The same could be said for other indicators, including the CBT and other areas of the OSCE (data not shown).

One of the reasons why the scores of the online classes were not inferior to those of face-to-face classes might be because of the availability of each student to review the video recordings. We provided each student with a recording of their own performance in the class for self-review, which was not always provided in face-to-face classes. We also provided students with feedback from the teacher and other students during online classes. This is consistent with the findings of a previous study, which found that video reviewing of the OSCE performance is effective (Mookherjee et al., 2019). Moreover, the students accepted online classes well, and their motivation for learning was not affected despite the lack of face-to-face communication with simulated patients. During the reflection, some students noted that “I learned a lot in this class, though the class was held online” and that “I thought that online classes are not so bad” (data not shown). There were almost no complaints regarding online classes. We guess that in the environment that the face-to-face classes were restricted and the students experienced suspended classes the students felt satisfied for joining the classes even online. Further investigation will be needed regarding this point.

Recently, Khamees et al. (2022) pointed out the lack of control groups and poor transferability in numerous publications due to singularity of institution, department, and program. In the present study, the marks of students on high-stakes examinations before the pandemic were used as a comparison between face-to-face and online classes. Some studies have revealed that there are no significant differences in educational outcomes between face-to-face and online classes in basic medicine (Omole et al., 2023), and pharmacological education (Aoe et al., 2023). However, when it comes to high-stakes examinations, it remains unclear whether online education is not inferior to face-to-face education. Saad et al (2023) have showed that in some areas (clinical reasoning and history taking) of pre-clinical OSCE, students showed no less than comparable results, arguing that these skills are amenable to online learning in a medical school in Australia. Their results in some areas like medical interview in Japanese OSCE support our results. However, in their study, it is not clear about the details of the OSCE assessment, whether the assessment is by item-wise or global. In recent years, the pre-CC OSCE results have been recognized as an important educational outcome also for educational institutions (Hirsh et al., 2012). Our result, the educational outcome in the high-stakes examination, can be considered to fall in the top tier, the result, in the Kirkpatrick’s four-level model (Kirkpatrick, 1996). Moreover, our research is unique and important as few studies have directly compared the educational outcomes between face-to-face classes and online classes in high-stakes examination.

In Japan, the Medical Practitioners Act was revised in 2023, allowing medical students to perform some medical procedures under the supervision of a teaching physician after passing the pre-CC OSCE and CBT. This change also made the pre-CC OSCE a requirement for the national board examination. Hence, the pre-CC OSCE in Japan has become even more important, as much the responsibility for the education even greater. Our results show that online classes can contribute to the practice of “Medical interviews”.

It must be noted that online classes are not a complete alternative to face-to-face classes. Many studies have indicated that online education has some negative aspects (e.g., the need for infrastructure and devices, high cost, lack of personal interaction, etc.) (Arja et al., 2022; Mortazavi et al., 2021; Shaiba et al., 2023). One of the most significant elements that are difficult to teach in online classes is nonverbal communication. However, as Ishikawa et al. (2010) reported, although students are capable of understanding nonverbal communication despite struggling to change their performance through educational intervention, it is well recognized that nonverbal communication is difficult to teach even in face-to-face classes. Additionally, when it comes to procedural skills such as venipuncture, the educational outcomes in the online learning group were inferior to that of face-to-face learning group and students also felt that they were not taught satisfactorily (Dost et al., 2020; Saad et al., 2023). We should keep in mind that online education does not fully replace face-to-face education.

We saw a lack of significant differences in GS, both in year-by-year comparison and comparison between face-to-face and online groups. Although the tasks allocated to each university by CATO differ every year, the checkpoints are essentially common in quite a few areas; so, a comparison was made for both year by year and before and after the pandemic. GS usually reflects holistic assessment, which is difficult to produce results via technical education, whereas it might be easier for learners and teachers to deal with item-wise assessment (Govaerts et al., 2011; Jonsson & Svingby, 2007; Sadler, 2009). Moreover, in online classes, we used a checklist of the students’ performance (not shown to the students, but comments were given according to the checklist), which might have contributed to the improvement of IS. As to CBT, it is standardized by the accumulated examinations and the Item Response Theory and is assessed basically by knowledge base. The educational strategies that mainly should impact on the assessment of CBT, based on the lecture, have not changed before and after the pandemic, in the face-to-face classes or online classes. During the pandemic, the extra-curricular activities of the students were restricted, and several articles argue that self-studying time of the students increased (Barton et al., 2021; Guluma & Brandl, 2023). These might have contributed to the smaller elevation of CBT-IRT than the IS of pre-CC OSCE.

We need to take into consideration the confounding of several factors such as the curriculum changes, instructor training, student characteristics and students’ self-study time. While online classes have been a change in the curriculum, the rest remains unchanged. The instructors and students needed to become familiar with online classes, but there was no change in the educational goals of the class itself. Additionally, in the first year of the pandemic in 2020, we were unable to get enough data and the online class itself was implemented as “being built”. By 2021 and 2022, the class was almost stable. However, getting used to online classes of the instructors and students could be a confounding factor. The class tool (Zoom®) was continuously improved, which might be a minor confounding factor. Additionally, the students might have had excellent ITC skills, which might also be a confounding factor.

Some frameworks describing the evidence of online medical education outcome might contribute to generalizing our results (Martinengo et al., 2024; McGee et al., 2024; Wilcha, 2020). Needless to say, there are confrontations regarding the limitations of these generalizations, pointing out the context-depending factors, high heterogeneity among studies and “The Covid-19 Effects” (Abdull Mutalib et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2016; Martinengo et al., 2024; McGee et al., 2024). However, these frameworks will be applicable in generalizing our results; although there are some potential confounding factors such as the students, the instructors, the educational resources and the “pandemic era” itself, the online medical interview education could be an effective educational curriculum for educating medical interview skills as well as some interpersonal skills.

A. Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is that it was performed in a single institution. Hence, the generalizability of this study may be lower than that of multi-institutional studies. However, not much variation exists in the nature of students and in the educational curriculum they experience. Of course, to make the evidence more robust and further validate, multi-centred or multi-institutional studies are still needed. At the same time, these factors should not be too disparate as it is very difficult to find a suitable population for these factors. In this regard, our participants and classes can be considered as a reasonable population.

Another limitation of this study is the number of participants. In 2020, we could not obtain enough participants because of the pandemic. After the pandemic, our students and staff shifted to online classes, and the number of face-to-face classes decreased. In 2021 and 2022, we decided to obtain consent for participation in this study in the waiting time after face-to-face OSCE examination as it was difficult to obtain consent only during online classes. In this context, the participants may have a positive view of various aspects of student life including studies, which may be a potential bias of sample population. Additionally, the waiting time after the OSCE examination was short for some students, which might have made it difficult to think about understanding the concept of this research and whether consent should be given.

In this study, qualitative analyses investigating if the students were positive about the classes are limited to some extent. During the pandemic, the psychological situation and the learning behaviour of the students might have differed from that of before the pandemic. To investigate this aspect, qualitative studies will be needed.

Moreover, the evaluation criteria of the pre-CC OSCE are not open to the public due to CATO policy. This probably leads to a lack of transparency of the evaluation, causing another limitation of this study. However, Japanese OSCE evaluation criteria is similar to CANMED’s OSCE checklist (Kassam et al., 2016), which will support the validity of the results of Japanese OSCE and our results.

Finally, this study retrospectively compared the educational effect between students before and after the pandemic, which may limit the causal inferences of educational outcome effects of face-to-face versus online in medical interview OSCE. A randomized controlled trial will be needed to verify the results obtained in this study.

V. CONCLUSION

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we were forced to change our medical interview classes from face-to-face to be online. However, in high-stakes examinations such as the pre-CC OSCE and CBT, the results of the online group were not inferior to those of the face-to-face group. We consider this result extremely important because we directly compared the educational outcomes of high-stakes examinations between online and face-to-face groups who took the same medical interview classes, and because this evaluation falls in the top level of Kirkpatrick’s model. Our results suggest that online education provides a viable option in teaching interpersonal skills and support the integration of online medical interview training into preclinical curricula, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Randomized controlled trials and multi-institutional studies are needed to further validate our results.

Notes on Contributors

SH and ME conducted the whole research.

SH, MI, SK, JM, HM, and ME performed the classes and collected the data.

SH performed data analyses.

SH, MI, SK, JM, HM, and ME contributed to writing the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the UTokyo Faculty of Medicine (Approval No. 2021005NI). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Moreover, the data of students who provided consent to the secondary use of their data in another research, given by the ethics committee of the UTokyo Faculty of Medicine (Approval No. 11763), were included.

Data Availability

The data in this study are not publicly available because of confidentiality agreements with the participants, conditions obligating CATO, and confidential nature of the data.

Acknowledgement

We thank the students of the UTokyo Medical School who participated in this study. We also thank the UTokyo Staff for their cooperation.

Funding

This study was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24K06092 and ACRO incubation grants of Teikyo University.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

References

Abdull Mutalib, A. A., Md. Akim, A., & Jaafar, M. H. (2022). A systematic review of health sciences students’ online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 524. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03579-1

Alshaibani, T., Almarabheh, A., Jaradat, A., & Deifalla, A. (2023). Comparing online and face-to-face performance in scientific courses: A retrospective comparative gender study of Year-1 students. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 14, 1119–1127. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s408791

American Medical Association. (2016, June 15). AMA encourages telemedicine training for medical students, residents. AMA Press Releases.

Aoe, M., Esaki, S., Ikejiri, M., Ito, T., Nagai, K., Hatsuda, Y., Hirokawa, Y., Yasuhara, T., Kenzaka, T., & Nishinaka, T. (2023). Impact of different attitudes toward face-to-face and online classes on learning outcomes in Japan. Pharmacy, 11(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010016

Arja, S. B., Fatteh, S., Nandennagari, S., Pemma, S. S. K., Ponnusamy, K., & Arja, S. B. (2022). Is emergency remote (online) teaching in the first two years of medical school during the COVID-19 pandemic serving the purpose? Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 13, 199–211. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s352599

Barton, J., Rallis, K. S., Corrigan, A. E., Hubbard, E., Round, A., Portone, G., Kuri, A., Tran, T., Phuah, Y. Z., Knight, K., & Round, J. (2021). Medical students’ pattern of self-directed learning prior to and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic period and its implications for Free Open Access Meducation within the United Kingdom. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.5

Bastos, R. A., Carvalho, D. R. D. S., Brandão, C. F. S., Bergamasco, E. C., Sandars, J., & Cecilio-Fernandes, D. (2021). Solutions, enablers and barriers to online learning in clinical medical education during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Medical Teacher, 44(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2021.1973979

Basuodan, R. (2024). Comparisons of the academic performance of Medical and Health-Sciences students related to three learning methods: A cross-sectional study. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 15, 1339–1347. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s493782

Budakoğlu, I. İ., Sayılır, M. Ü., Kıyak, Y. S., Coşkun, Ö., & Kula, S. (2021). Telemedicine curriculum in undergraduate medical education: a systematic search and review. Health and Technology, 11(4), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-021-00559-1

Common Achievement Tests Organization (CATO). (2005). Common Achievement Tests Organization. https://www.cato.or.jp/index.html

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., Magni, P. A., & Lam, S. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

Daniel, M., Gordon, M., Patricio, M., Hider, A., Pawlik, C., Bhagdev, R., Ahmad, S., Alston, S., Park, S., Pawlikowska, T., Rees, E., Doyle, A. J., Pammi, M., Thammasitboon, S., Haas, M., Peterson, W., Lew, M., Khamees, D., Spadafore, M., … Stojan, J. (2021). An update on developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME scoping review: BEME Guide No. 64. Medical Teacher, 43(3), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1864310

Dost, S., Hossain, A., Shehab, M., Abdelwahed, A., & Al-Nusair, L. (2020). Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open, 10(11), e042378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378

Gordon, M., Patricio, M., Horne, L., Muston, A., Alston, S. R., Pammi, M., Thammasitboon, S., Park, S., Pawlikowska, T., Rees, E. L., Doyle, A. J., & Daniel, M. (2020). Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 63. Medical Teacher, 42(11), 1202–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1807484

Govaerts, M. J. B., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Muijtjens, A. M. M. (2010). Workplace-based assessment: Effects of rater expertise. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9250-7

Guetterman, T. C., Sakakibara, R., Baireddy, S., Kron, F. W., Scerbo, M. W., Cleary, J. F., & Fetters, M. D. (2019). Medical students’ experiences and outcomes using a virtual human simulation to improve communication skills: Mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e15459. https://doi.org/10.2196/15459

Guluma, K. Z., & Brandl, K. (2022). Virtual learning allows for adaptation of study strategies in a cohort of U.S. medical students. Medical Teacher, 45(1), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2022.2105690

Hammersley, V., Donaghy, E., Parker, R., McNeilly, H., Atherton, H., Bikker, A., Campbell, J., & McKinstry, B. (2019). Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: A non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 69(686), e595–e604. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19x704573

Harden, R. M., Stevenson, M., Downie, W. W., & Wilson, G. M. (1975). Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination. BMJ, 1(5955), 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.5955.447

Hirsh, D., Gaufberg, E., Ogur, B., Cohen, P., Krupat, E., Cox, M., Pelletier, S., & Bor, D. (2012). Educational outcomes of the Harvard Medical School–Cambridge integrated clerkship. Academic Medicine, 87(5), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31824d9821

Horita, S., Park, Y., Son, D., & Eto, M. (2021). Computer-based test (CBT) and OSCE scores predict residency matching and National Board assessment results in Japan. BMC Medical Education, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02520-2

Ishikawa, H., Hashimoto, H., Kinoshita, M., & Yano, E. (2010). Can nonverbal communication skills be taught? Medical Teacher, 32(10), 860–863. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421591003728211

Jonsson, A., & Svingby, G. (2007). The use of scoring rubrics: Reliability, validity, and educational consequences. Educational Research Review, 2(2), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2007.05.002

Kassam, A., Cowan, M., & Donnon, T. (2016). An objective structured clinical exam to measure intrinsic CanMEDS roles. Medical Education Online, 21(1), 31085. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.31085

Khamees, D., Peterson, W., Patricio, M., Pawlikowska, T., Commissaris, C., Austin, A., Davis, M., Spadafore, M., Griffith, M., Hider, A., Pawlik, C., Stojan, J., Grafton-Clarke, C., Uraiby, H., Thammasitboon, S., Gordon, M., & Daniel, M. (2022). Remote learning developments in postgraduate medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 71. Medical Teacher, 44(5), 466–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2022.2040732

Kirkpatrick, D. (1996). Great ideas revisited. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Revisiting Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level model. Training & Development, 50(1), 54–59. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ515660

Liu, Q., Peng, W., Zhang, F., Hu, R., Li, Y., & Yan, W. (2016). The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), e2. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4807

Martinengo, L., Ng, M. S. P., De Rong Ng, T., Ang, Y., Jabir, A. I., Kyaw, B. M., & Car, L. T. (2024). Spaced digital education for health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Preprint). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26, e57760. https://doi.org/10.2196/57760

McGee, R. G., Wark, S., Mwangi, F., Drovandi, A., Alele, F., & Malau-Aduli, B. S. (2024). Digital learning of clinical skills and its impact on medical students’ academic performance: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06471-2

Mookherjee, S., Strujik, J., Cunningham, M., Kaplan, E., & Çoruh, B. (2018). Independent and mentored video review of OSCEs. The Clinical Teacher, 16(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12755

Mortazavi, F., Salehabadi, R., Sharifzadeh, M., & Ghardashi, F. (2021). Students’ perspectives on the virtual teaching challenges in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_861_20

Omole, A. E., Villamil, M. E., & Amiralli, H. (2023). Medical education during COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative effectiveness study of face-to-face traditional learning versus online digital education of basic sciences for medical students. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35837

Saad, S., Richmond, C., King, D., Jones, C., & Malau-Aduli, B. (2023). The impact of pandemic disruptions on clinical skills learning for pre-clinical medical students: Implications for future educational designs. BMC Medical Education, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04351-9

Sadler, D. R. (2008). Indeterminacy in the use of preset criteria for assessment and grading. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801956059

Shaiba, H., John, M., & Meshoul, S. (2022). Female Saudi College students’ e-learning experience amidst COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation and analysis. Heliyon, 9(1), e12768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12768

Wilcha, R. (2020). Effectiveness of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 Crisis: Systematic review. JMIR Medical Education, 6(2), e20963. https://doi.org/10.2196/20963

Zaccariah, Z. R., Irvine, A. W., & Lefroy, J. E. (2022). Feasibility study of student telehealth interviews. The Clinical Teacher, 19(4), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13490

*Shoko Horita

2-11-1, Kaga, Itabashi-ku,

Tokyo 173-8605, Japan

Email: horitas-tky@umin.ac.jp

Submitted: 30 December 2024

Accepted: 5 July 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 63-72

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/OA3777

Chollada Sorasak1, Worayuth Nak-Ai2, Choosak Yuennan3 & Mansuang Wongsapai1

1Intercountry Centre for Oral Health, Department of Health, Thailand; 2Sirindhorn College of Public Health Chonburi, Praboromarajchanok Institute, Thailand; 3Boromarajonani College of Nursing Chiang Mai, Praboromarajchanok Institute, Thailand

Abstract

Introduction: Nutrition literacy represents a critical determinant of oral health outcomes. Guided by Social Cognitive Theory and the Nutrition Literacy Skills Framework, this study evaluated the implementation and effectiveness of a nutrition literacy programme for oral health promotion among village health volunteers (VHVs), key implementers in Thailand’s healthcare system, during January to December 2024.

Methods: A convergent parallel mixed-methods design was employed to address existing methodological gaps in nutrition literacy research. The quantitative component comprised a cross-sectional survey (N=60 VHVs trained in January 2024) and clinical outcome monitoring via electronic health records. The qualitative strand involved a multi-case study approach with purposive sampling (n=20) through in-depth interviews. Data collection occurred at 6-month post-implementation (July 2024), with clinical monitoring through December 2024. Analysis integrated descriptive and inferential statistics with thematic analysis.

Results: Post-implementation analysis revealed significantly enhanced nutrition literacy skills (M=4.14, SD=0.414), with notable improvements in communication (M=4.74, SD=0.511) and implementation (M=4.21, SD=0.440). All six nutrition literacy domains showed strong correlations (r=0.712-0.868, p<.01), supporting the framework’s interconnected nature. Clinical outcomes improved significantly: oral health check-up rates increased from 1.41% to 2.61% (p<.05), and functional teeth retention rose from 87.36% to 92.72% (p<.01). Qualitative findings revealed adaptive knowledge transfer methods and context-specific implementation strategies influenced by community readiness.

Conclusion: Through comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation, the 12-month implementation data demonstrated significant improvements in both VHVs’ nutrition literacy skills and clinical oral health outcomes. Success factors included theoretically-grounded implementation strategies and stakeholder engagement in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: Convergent Parallel, Health Literacy, Mixed Methods, Nutrition, Oral Health, Thailand, Village Health Volunteer

Practice Highlights

- Nutrition literacy among VHVs significantly improved across all six key domains.

- Oral health check-up rates increased from 41% to 2.61% post-programme implementation.

- Functional teeth retention rose from 36% to 92.72% over the 12-month period.

- VHVs used context-specific strategies for community-based nutrition education.

I. INTRODUCTION

Oral health is fundamentally linked to nutrition and dietary behaviours, yet nutritional factors affecting oral health remain a significant public health challenge worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (Peres et al., 2019; Watt et al., 2019). In Thailand, the high prevalence of dental caries and periodontal diseases related to dietary habits (Chaianant et al., 2022), underscores the urgent need for effective nutrition education strategies for oral health promotion.

Understanding the relationship between nutrition literacy and oral health behaviours requires consideration of multiple theoretical perspectives. Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2004) highlights how personal factors, dietary patterns, and environments interact to shape oral health behaviours, particularly relevant in Thailand’s family-based eating culture. The nutrition literacy skills Framework (Squiers et al., 2012) outlines how individuals develop and apply nutrition literacy competencies through interactions between dietary knowledge and social environments. Additionally, Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) demonstrates how family and societal systems influence health behaviours and programme implementation.

Within this theoretical context, nutrition literacy for oral health emerges as a critical determinant of oral health outcomes. While health literacy encompasses capacities for accessing and using health information (Sørensen et al., 2012), nutrition literacy for oral health specifically focuses on these competencies in oral healthcare. Evidence consistently shows that individuals with low nutrition literacy tend to exhibit poor oral health behaviours and outcomes (Berkman et al., 2011; Kickbusch et al., 2013). This relationship is particularly significant in reducing oral health disparities (Horowitz & Kleinman, 2012), with higher nutrition literacy correlating with improved oral hygiene practices and health outcomes (Baskaradoss, 2018).

Recent advances in nutrition literacy programmes for oral health promotion have revealed that culturally tailored, context-specific interventions can significantly enhance service accessibility and oral healthcare engagement (Macek et al., 2016). Various programme modalities have emerged, encompassing educational initiatives, community-based activities, and digital media interventions (Dickson-Swift et al., 2014). These approaches align well with Thailand’s dental public health policy, which emphasises proactive oral health promotion and community participation. Systematic review (Firmino et al., 2017) identified several critical gaps in existing research: the absence of mixed-methods studies examining both programme effectiveness and change processes, limited analysis of community-level behavioural change mechanisms, and insufficient research in resource-constrained developing countries where success factors may differ substantially from developed nations.

To address these research gaps, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a nutrition literacy programme for oral health promotion in Thailand’s context. Of particular interest is the role of VHVs as key implementation agents, given their established position in community health promotion (Kowitt et al., 2015). While previous research has demonstrated VHVs’ capacity to utilise technology for expanding health service coverage (Jandee et al., 2015), empirical evidence regarding their role in promoting nutrition literacy for oral health remains limited.

Guided by our theoretical framework, we employed a Convergent Parallel Mixed Methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017), enabling comprehensive assessment of both quantitative programme effectiveness and qualitative change mechanisms. This approach examines how social modelling, nutrition literacy skill development related to oral health, and environmental factors interact to influence programme outcomes. Ultimately, this study’s findings will contribute to developing contextually appropriate nutrition literacy strategies for oral health promotion in developing countries while aligning with Thailand’s dental public health policies.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design

This study employed a convergent parallel mixed methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017) to comprehensively evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of a nutrition literacy programme for oral health promotion. The design integrated quantitative outcomes with qualitative insights to achieve deeper understanding than single-method approaches. The quantitative component utilised a cross-sectional survey to assess nutrition literacy skills and clinical outcomes, while the qualitative component employed a multi-case study approach (Yin, 2018) to explore implementation experiences and contextual factors.

B. Population and Sampling

The quantitative phase included all VHVs who completed nutrition literacy training (N=60) in January 2024, with data collection occurring in July 2024. For the qualitative component, 20 VHVs were purposively selected using intensity sampling (Miles et al., 2013) based on four criteria: programme implementation experience exceeding six months, strong communication abilities, representation from varied performance areas, and voluntary informed consent. This sample size achieved theoretical saturation (Creswell, 2013; Guest et al., 2006). Gender distribution differed between samples (quantitative: 98.3% female; qualitative: 70% female) due to purposive sampling for diverse leadership perspectives. Sensitivity analysis confirmed no significant gender-based differences in primary outcomes (p > .05). The six-month assessment period aligned with established behaviour change evaluation timeframes (Glasgow et al., 2019), while monitoring through December 2024 captured seasonal variations and sustainability data.

C. Research Instruments

Two complementary instruments were developed and validated through pilot testing with 30 VHVs sharing similar characteristics with the target population, but excluded from the final sample. The questionnaire was designed according to Nutbeam’s health literacy framework (Nutbeam, 2000), operationalizing three literacy levels into six nutrition literacy components relevant to oral health promotion. Items utilised a five-point Likert scale (1 = “not confident at all” to 5 = “very confident”) for self-assessment of perceived competencies. A panel of five experts including community dentistry, nutrition, public health, health literacy, and health communication specialists assessed content validity, achieving a high IOC index of 0.96, while internal consistency demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.929).

The structured interview guide explored knowledge application, teaching methods, implementation challenges, outcomes, and recommendations following established qualitative research principles (Jacob & Furgerson, 2012). Qualitative trustworthiness was ensured through member checking at two stages: during interviews for immediate verification and after preliminary analysis with eight selected participants for validation and refinement.

D. Data Collection

Baseline data was collected prior to programme implementation in January 2024, establishing pre-intervention metrics through public health service records. Following six-month implementation, parallel quantitative and qualitative assessments were conducted in July 2024. Self-assessment questionnaires were administered to all VHVs, followed by in-depth interviews (45-60 minutes) with 20 purposively selected participants until data saturation was achieved (Guest et al., 2006). In accordance with Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) guidelines (Zachariah et al., 2024), participant confidentiality was maintained throughout the study, with written informed consent obtained after comprehensive briefing on study objectives and participant rights. Monthly data extraction from the Health Data Centre continued through December 2024 to capture sustained programme effects, with systematic collection on the 5th of each month ensuring complete and timely data acquisition.

E. Data Analysis

The analytical approach integrated multiple complementary methods for comprehensive understanding. Quantitative analysis included descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations) with Shapiro-Wilk normality testing. Inferential analyses comprised paired t-tests for pre-post comparisons (α = 0.05), chi-square tests for categorical outcomes, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients examining relationships between nutrition literacy domains. Effect sizes were reported using Cohen’s d with bootstrap confidence intervals (1,000 resamples). Statistical analyses utilised IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics software. Missing data patterns were examined using Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test, with multiple imputation (5 datasets) addressing missing values following Rubin’s guidelines (2004). Sensitivity analyses compared complete-case and imputed datasets (van Buuren, 2018).

Qualitative data underwent thematic analysis following established frameworks (Braun & Clarke, 2006), involving verbatim transcription, independent coding by two researchers, and iterative thematic framework development through consensus meetings. ATLAS.ti software facilitated systematic organisation and analysis. Quality assurance included investigator triangulation, member checking with eight participants, audit trail documentation, and researcher reflexivity journals.

F. Data Integration

A comprehensive integration strategy synthesised quantitative and qualitative findings through three interconnected phases (Cano & Lomibao, 2023). Joint displays facilitated systematic comparison of results, enabling identification of convergent and divergent patterns. Meta-inferences were constructed through iterative cross-method analysis, with attention to complementary insights. Pattern matching techniques examined alignments between quantitative outcomes and qualitative themes, developing integrated theoretical understandings. Conflicting findings were reconciled by contextualising quantitative results with qualitative explanations, while complementary data enriched overall interpretation, enhancing study rigor and validity.

III. RESULTS

All participants (N=60) completed quantitative assessments at baseline and a 6-month follow-up, with 20 VHVs participating in qualitative interviews. Clinical outcomes were monitored through December 2024 using complete Health Data Centre monthly data. Following convergent parallel design, quantitative and qualitative data streams were systematically merged to achieve comprehensive understanding of programme implementation and outcomes. The integrated analysis revealed that communication skills improvements were explained through qualitative evidence of adaptive teaching strategies, while regional outcome variations were illuminated by implementation challenges identified through qualitative inquiry. This systematic data merging approach provided richer insights than either quantitative or qualitative methods could offer independently.

A. Baseline Characteristics

1. Qualitative Sample (n = 20)

The qualitative sample achieved a full response rate (100%). Participants were predominantly female (70%), with males comprising 30%. The age distribution showed that 70% were between 50–60 years, while 15% each were aged 30–39 and 40–49 years. No participants were over 60. In terms of role, 65% served as Village Health Volunteers (VHVs), and 35% were Caregivers. None held dual roles.

2. Quantitative Sample (n = 60)

The quantitative sample also achieved a 100% response rate. Females constituted the vast majority (98.3%), with only one male respondent (1.7%). Most participants (70%) were aged 50–60 years, with smaller proportions aged 30–39 (11.7%), 40–49 (16.7%), and over 60 (1.7%). Regarding position, 85% were VHVs, 13.3% were Caregivers, and 1.7% held both roles.

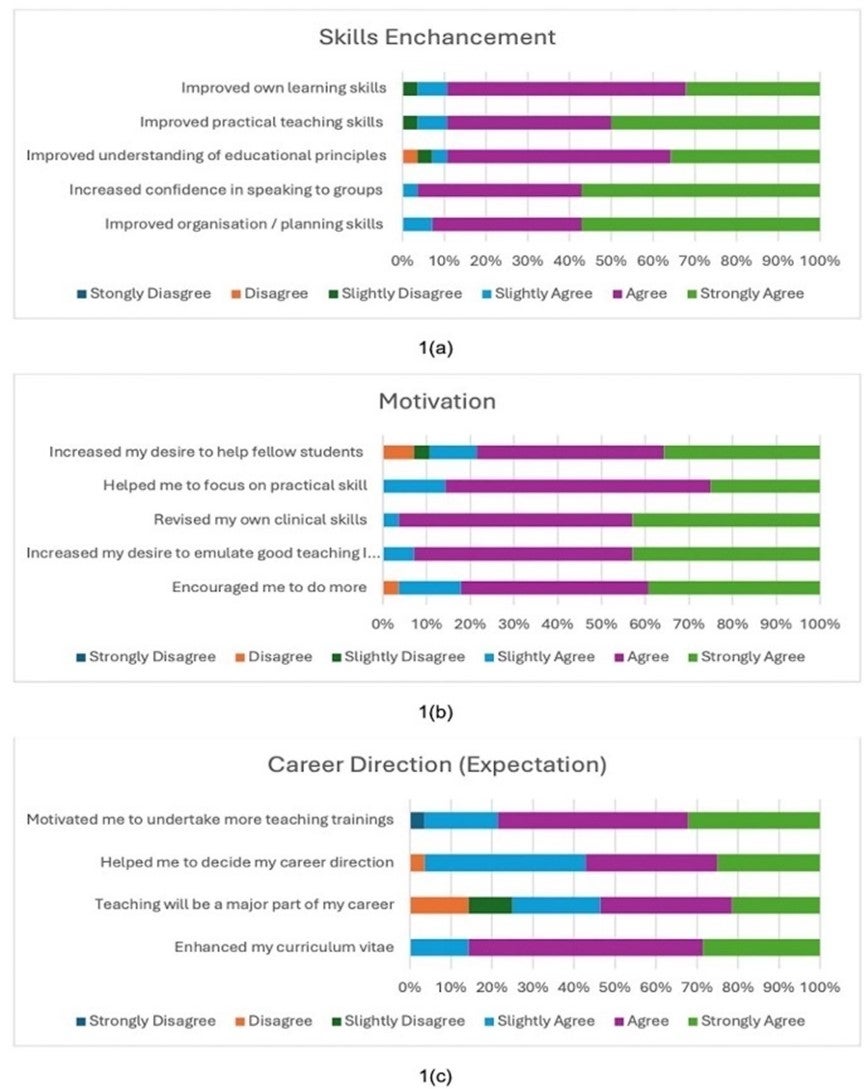

B. Programme Implementation and Nutrition Literacy Skills for Oral Health

The intervention (Table 1) demonstrated significant improvements across all six nutrition literacy domains (p< 0.001) with large effect sizes. Communication skills showed the greatest improvement (d = 1.64, mean difference: 0.84 points, 95% CI: 0.66-1.02), followed by Decision Making (d = 0.90), Critical Inquiry (d = 0.88), Understanding (d = 0.85), Application (d = 0.77), and Access (d = 0.74). Other domains improved by 0.36-0.41 points.

C. Clinical Outcomes and Programme Effectiveness

Clinical outcomes significantly improved. Dental check-up rates increased from 1.41% to 2.61% (difference: 1.20 percentage points, 95% CI: 0.90-1.50, p=0.032). Participants with ≥20 functional teeth rose from 87.36% to 92.72% (difference: 5.36 percentage points, 95% CI: 3.38-7.34, p< 0.001), indicating substantial improvements in both knowledge and oral health behaviour.

|

Outcomes |

Baseline (mean±SD) |

6-month (mean±SD) |

Mean difference (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

Nutrition Literacy Skills |

||||

|

Access |

3.80±0.50 |

4.16±0.47 |

0.36 (0.19, 0.53) |

<0.001† |

|

Understanding |

3.75±0.48 |

4.15±0.46 |

0.40 (0.23, 0.57) |

<0.001† |

|

Critical Inquiry |

3.70±0.47 |

4.11±0.46 |

0.41 (0.24, 0.58) |

<0.001† |

|

Decision Making |

3.72±0.46 |

4.13±0.45 |

0.41 (0.25, 0.57) |

<0.001† |

|

Application |

3.85±0.49 |

4.21±0.44 |

0.36 (0.19, 0.53) |

<0.001† |

|

Communication |

3.90±0.52 |

4.74±0.51 |

0.84 (0.66, 1.02) |

<0.001† |

|

Clinical Outcomes |

||||

|

Dental check-up rate (%) |

1.41 |

2.61 |

1.20 (0.90, 1.50) |

0.032‡ |

|

Functional teeth (%) * |

87.36 |

92.72 |

5.36 (3.38, 7.34) |

<0.001‡ |

Note: *Defined as having ≥20 functional natural teeth

†Statistically significant at p< 0.001, Paired t-test

‡Statistically significant at p< .05 for dental check-up rate and p< 0.001 for functional teeth, Chi-square test

Data were retrieved from the Health Data Centre database (Ministry of Public Health, 2024).

Table 1. Changes in Nutrition Literacy Skills Related to Oral Health and Clinical Outcomes After a 6-Month Training Programme (N=60)

|

Health Literacy Domain |

1. Access |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. Application |

6. Communication |

|

1. |

1 |

|||||

|

2. |

.858** |

1 |

||||

|

3. |

.753** |

.712** |

1 |

|||

|

4. |

.775** |

.817** |

.834** |

1 |

||

|

5. |

.724** |

.770** |

.797** |

.797** |

1 |

|

|

6. |

.812** |

.820** |

.822** |

.868** |

.799** |

1 |

Note: N = 60; **p < .01 (2-tailed) Pearson correlation coefficients are shown.

Table 2. Correlation Analysis of Nutrition Literacy Domains Related to Oral Health

Regional variations in dental check-up rates were substantial, ranging from 0.07% to 38.18% (p < 0.001) across participating health centres, suggesting the need to investigate factors contributing to different implementation outcomes despite similar geographical and healthcare delivery contexts.

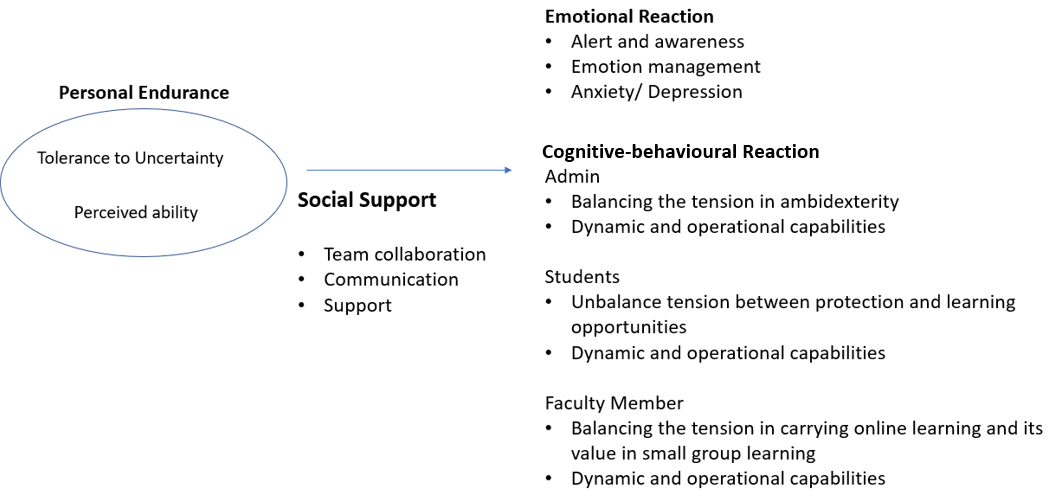

The findings support overall programme effectiveness, though the cross-sectional design indicates the need for longitudinal research to confirm long-term impacts. Future nutrition literacy programmes for oral health promotion should emphasize communication skills and context-specific implementation approaches. The qualitative analysis of 20 VHV interviews yielded four main themes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Qualitative final thematic map

D. Implementation Process and Contextual Factors

1. Knowledge Transfer Patterns

VHVs utilised multiple communication channels and diverse pedagogical approaches. Individual consultations involved direct problem assessment, with participants noting “Face-to-face, asking what problems they have, like sensitive teeth” (P15). Digital platforms expanded reach through “Online communication and inviting others to join our Line group” (P5). Teaching methods included demonstrations, mnemonics, and hands-on practice.

2. Audience Diversity

VHVs encountered heterogeneous learning populations with varying engagement levels. Successful interactions were characterised by high comprehension rates: “Everyone understood and could practice, no problems as they all understood well” (P19). However, engagement challenges persisted, with some noting “One person at home is not very interested” (P16).

3. Implementation Challenges

Communication barriers emerged as significant obstacles. VHVs identified hearing difficulties: “The listener’s hearing, they can’t hear well” (P1), language barriers: “Don’t use too many English terms, some words are not understood” (P10), and content complexity issues: “Some content is difficult to understand, takes a long time and repeated study” (P14).

4. Development Approaches

VHVs suggested practical improvements emphasising “Should practice more than theory” (P1). They recommended age-appropriate strategies: “Elderly may have difficulty learning, but if we can make content easy to understand, they will gain knowledge too” (P15), and streamlined delivery: “Shorter courses might attract more participants” (P5).

E. Integrated Results

The convergent parallel design employed a merging data integration approach to synthesise quantitative and qualitative findings systematically, providing comprehensive understanding of programme effectiveness., as presented in Table 3.

|

Major Themes |

Quantitative |

Qualitative |

Meta-inference |

|

Nutrition Literacy Skills Performance Related to Oral Health |

Overall implementation: M=4.14±0.41, p< 0.001; Highest in communication (M=4.74±0.51); Strong inter-skill correlations (r=.712-.868, p< 0.001) |

Demonstrated multiple teaching approaches: individual counselling, memory techniques, continuous monitoring |

Quantitative high scores validated by qualitative evidence of practical skill application |

|

Clinical Outcome Changes |

Dental check-up: 1.41% to 2.61% (p< .01); Functional teeth: 87.36% to 92.72% (p< .01); Regional variation: 0.07-38.18% |

Implementation variations: successful behaviour adoption, mixed community readiness, diverse response levels |

Outcome improvements linked to implementation quality and community readiness |

|

Implementation Challenges |

Highest in self-monitoring (M=4.25±0.44); Significant regional differences (p< .01) |

Identified barriers: technical language, age-related learning, practice compliance |

Statistical variations explained by specific implementation challenges identified qualitatively |

|

Support Systems |

Strong correlations between: decision-making and communication (r=.868); access and understanding (r=.858); all p< 0.001 |

Multiple support channels: digital platforms, family networks, community groups |

Integrated support systems crucial for programme effectiveness |

Table 3. Integrated Analysis of Mixed Methods Results

The systematic merging of quantitative and qualitative data through meta-inference analysis revealed four key dimensions of programme implementation and outcomes.

1. Nutrition Literacy Skills and Clinical Outcomes

Quantitative findings demonstrated high overall implementation levels (M=4.14±0.41, p< 0.001), with communication skills showing exceptional improvement (M=4.74±0.51). The strong correlation between communication and decision-making skills (r=.868, p< 0.001) was validated through qualitative evidence: “We adapted communication methods based on audience needs” (P15).

Dental check-up rates increased significantly from 1.41% to 2.61% (p< .01), while functional dentition improved from 87.36% to 92.72% (p< .01). Qualitative insights revealed implementation quality influences: “Regular follow-ups and practical demonstrations helped maintain behaviour changes” (P8). Regional outcome variations (0.07-38.18%) aligned with identified barriers and facilitators.

2. Implementation Dynamics and Support Systems

Strong correlations between access and understanding (r=.858, p< 0.001) were complemented by contextual adaptation findings. VHVs balanced cultural factors: “We needed to balance traditional beliefs with modern dental care practices” (P13). Statistical associations among nutrition literacy domains (r=.712-.868, all p< 0.001) were substantiated by interconnected support mechanisms: “The combination of in-person support and online reminders helped maintain engagement” (P5).

The meta-inference demonstrates programme effectiveness through synergy of enhanced nutrition literacy skills and context-sensitive implementation strategies, emerging through systematic integration of quantitative measurements with qualitative insights.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Programme Effectiveness and Theoretical Framework

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a Village Health Volunteers (VHVs)-led nutrition literacy programme for oral health promotion in significantly improving nutrition literacy skills and clinical outcomes. The findings align with established empirical evidence at regional and international levels regarding healthcare personnel capacity development and relationships between nutrition literacy for oral health, oral health behaviours, and preventive service utilisation (Baskaradoss, 2018; Nutbeam, 2008; Samarasekera et al., 2024; Batista et al., 2017; Baskaradoss, 2016).

The strong correlation between nutrition literacy components, particularly communication and decision-making (r = .868), reflects their interconnected nature and underscores comprehensive skill development importance (Kunathum, 2023). This finding aligns with Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2004), emphasising behavioural, personal, and environmental factor interdependence in health promotion. Results support the Nutrition Literacy Skills Framework (Squiers et al., 2012), positioning communication and decision-making as essential mediators between nutrition literacy and oral health behavioural outcomes in diverse cultural contexts.

B. Clinical Outcomes and Community Engagement

The increase in dental check-up rates from 1.41% to 2.61%, while statistically significant, represents modest absolute change. However, within rural communities where oral health service access is severely limited and baseline utilisation extremely low, even small improvements may represent important community health engagement shifts (Petersen, 2009). This suggests early evidence of improved health literacy and behaviour change among participants, particularly VHVs who played critical implementation roles.

Future interventions could incorporate community-based incentives, outreach dental services, and proactive VHV follow-up to reinforce preventive behaviours. Evidence demonstrates that community mobilisation and culturally tailored interventions effectively improve oral health behaviours in low-resource settings (Fisher-Owens et al., 2013; Watt, 2007).

C. Domain-Specific Performance and Regional Variations

Communication and skill application emerged as key behavioural change drivers in nutrition literacy for oral health (M = 4.74, SD = 0.51 and M = 4.21, SD = 0.44 respectively). The relatively lower scores in critical inquiry (M = 4.11, SD = 0.46) and decision-making (M = 4.13, SD = 0.45) skills align with identified community health worker limitations (Gall et al., 2023) and indicate the necessity of incorporating hybrid learning approaches to strengthen advanced nutrition literacy competencies (Lin et al., 2024).

Regional analysis revealed significant outcome variations across implementation areas (0.07% to 38.18%, p < .01) (Watt et al., 2019), with stronger outcomes in communities with higher social capital. This pattern aligns with systematic reviews from low- and middle-income countries (Haldane et al., 2019) and documented disparities in Thailand’s healthcare systems (Chaianant et al., 2022). These findings support Asset-Based Community Development theory (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993), emphasising the importance of leveraging existing community strengths for sustainable oral health improvements.

D. Social Support Systems and Cultural Context

Social support systems proved crucial for programme success, particularly in developing countries where social networks, family support systems, and community resources serve as primary health determinants (Kowitt et al., 2015). The strong correlation between communication and community participation (r = .799, p < .01) reflects these interconnections, aligning with Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which emphasises how multiple environmental layers influence nutrition-related oral health behaviours in developing countries where community and cultural contexts play crucial roles.

E. Gender Considerations and Methodological Considerations

The quantitative sample exhibited significant gender imbalance (98.3% female participants), potentially influencing generalisability. In Northern Thailand, approximately 83% of VHVs are female, reflecting traditional social roles where women are often a group highly motivated to engage in volunteer work aimed at assisting others. Furthermore, women’s volunteer roles frequently involve healthcare and activities related to building community resilience (Sukhampha et al., 2023). Women typically exhibit higher health awareness and more proactive health behaviours than men, which may partly explain observed positive outcomes (Tan et al., 2021).

The notably high correlations between nutrition literacy domains (r=0.712-0.868) reflect comprehensive skill development influenced by the holistic training programme and Thai VHVs’ cultural context where integrated health communication is traditionally emphasised. This finding aligns with studies in Asian contexts (Leung et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2022) suggesting important cultural influences on health literacy skill development.

F. Study Strengths and Limitations

This study demonstrates methodological strengths through its convergent parallel mixed-methods design with systematic data integration, enhancing understanding through integrated quantitative and qualitative insights. The qualitative component achieved theoretical saturation (Guest et al., 2006), while community-based implementation aligned with established nutrition literacy research practices (Kowitt et al., 2015).

Key limitations include absence of factor analysis despite high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.929), pronounced gender imbalance restricting applicability, six-month follow-up potentially inadequate for capturing long-term changes (Baskaradoss, 2018), self-reported data risks and social desirability bias (Althubaiti, 2016), geographical specificity limiting generalisability given Thailand’s varied healthcare systems (Chaianant et al., 2022), and resource constraints precluding randomised controlled design. While the dental check-up rate increase was statistically significant (p=0.032), the modest improvement suggests need for more intensive interventions.

V. CONCLUSION

The VHVs-led nutrition literacy programme for oral health promotion demonstrates clear effectiveness through significant behavioural and clinical changes. Key success factors include local context adaptation and community engagement. For broader implementation, three policy directions are suggested: (1) integration with national health promotion policies, (2) inclusion of nutrition literacy indicators related to oral health in monitoring systems, and (3) development of standardised guidelines allowing local adaptation. Long-term VHVs capacity development should incorporate continuous professional development through structured mentoring programmes, nutrition literacy skill enhancement workshops for oral health promotion, and recognition systems for advanced competencies. Digital health integration should focus on mobile learning platforms, telemedicine support, and electronic health records, while sustainable monitoring mechanisms should include automated data collection, regular feedback loops, and community-based evaluations.

Future studies should have follow-up periods of at least one year to confirm sustainability of nutrition-related oral health behaviour changes (Baskaradoss, 2018). Research priorities should analyse regional variations, conduct economic evaluations, and develop sustainability indicators while integrating diverse learning approaches to enhance effectiveness (Lin et al., 2024). This study confirms the programme’s effectiveness and provides insights into change mechanisms and success factors for future nutrition literacy programmes focused on oral health promotion and public health policy. A phased scaling approach with diverse pilot programmes is recommended to optimise outcomes through cross-regional learning and experience sharing.

Notes on Contributors

Chollada Sorasak led the research design, developed methodology, conducted formal analysis and investigation. She was responsible for writing the original manuscript draft and managing the revision process.

Worayuth Nak-Ai provided expertise in validating the research design, research methodology and supervised the overall research implementation process. He was responsible for proof the original manuscript draft and managing the revision process.

Choosak Yuennan managed the data curation process and provided supervision for data collection and analysis procedures.

Mansuang Wongsapai coordinated resource allocation and managed project administration tasks throughout the study period.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Sirindhorn College of Public Health, Chonburi (COA No. 2023/T07, dated 21 August 2023).

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study, including four tables and one figure used in the analysis, are openly available in Figshare at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28105718.

The dataset includes the complete quantitative and qualitative analysis results, tables, and figures used in this study and can be accessed without restrictions for research purposes.

Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to Dr. Kwanmuang Kaewdamkoeng, Mr. Songkat Duangkhamsawat, Ms. Jariyakorn Ditjinda, and Ms. Wilawan Tangsattayatistan for their expertise in health literacy. We thank Dr. Chalermpol Kongchit, Ms. Waenkaew Chaiararm from Chiang Mai University for communications guidance, and Ms. Umaporn Nimtrakul and the Health Centre Region 1 Chiang Mai team for networking support. We also acknowledge the institutional support from the Intercountry Centre for Oral Health, Department of Health, Thailand, Sirindhorn College of Public Health Chonburi, and Boromarajonani College of Nursing.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Intercountry Centre for Oral Health, Department of Health provided in-kind support through equipment, materials, and transportation for data collection. The remaining expenses were self-funded by the corresponding author.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial, consultant, institutional or other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Althubaiti, A. (2016). Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 9, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S104807

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behaviour, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

Baskaradoss, J. K. (2016). The association between oral health literacy and missed dental appointments. Journal of the American Dental Association, 147(11), 867–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.05.011

Baskaradoss, J. K. (2018). Relationship between oral health literacy and oral health status. BMC Oral Health, 18(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0640-1

Batista, M. J., Lawrence, H. P., & Sousa, M. D. L. R. D. (2017). Oral health literacy and oral health outcomes in an adult population in Brazil. BMC Public Health, 18, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4443-0

Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., & Crotty, K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Cano, J. C., & Lomibao, L. S. (2023). A mixed methods study of the influence of phenomenon-based learning videos on students’ mathematics self-efficacy, problem-solving and reasoning skills, and mathematics achievement. American Journal of Educational Research, 11(3), 97–115.

Chaianant, N., Tussanapirom, T., Niyomsilp, K., & Gaewkhiew, P. (2022). Factors associated with oral health check-up in working adults: The 8th Thai National Oral Health Survey 2017. Thai Dental Public Health Journal, 27(2), 112–123.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dickson-Swift, V., Kenny, A., Farmer, J., Gussy, M., & Larkins, S. (2014). Measuring oral health literacy: A scoping review of existing tools. BMC Oral Health, 14, Article 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-14-148

Duijster, D., Monse, B., Dimaisip-Nabuab, J., Djuharnoko, P., Heinrich-Weltzien, R., Hobdell, M., Kromeyer-Hauschild, K., Kunthearith, Y., Mijares-Majini, M. C., Siegmund, N., Soukhanouvong, P., & Benzian, H. (2017). “Fit for School” – A school-based water, sanitation and hygiene programme to improve child health: Results from a longitudinal study in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR. BMC Public Health, 17, Article 302. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4203-1

Firmino, R. T., Ferreira, F. M., Paiva, S. M., Granville-Garcia, A. F., Fraiz, F. C., & Martins, C. C. (2017). Oral health literacy and associated oral conditions: A systematic review. Journal of the American Dental Association, 148(8), 604–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2017.04.012

Fisher-Owens, S. A., Isong, I. A., Soobader, M. J., Gansky, S. A., Weintraub, J. A., Platt, L. J., & Newacheck, P. W. (2013). An examination of racial/ethnic disparities in children’s oral health in the United States. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 73(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00367.x

Gall, M., Schroeder, F., & Heise, G. (2023). Community health worker use of smart devices for health promotion: Scoping review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 11(1), e42023. https://doi.org/10.2196/42023

Gholami, M., Pakdaman, A., Montazeri, A., Jafari, A., & Virtanen, J. I. (2014). Assessment of periodontal knowledge following a mass media oral health promotion campaign: A population-based study. BMC Oral Health, 14, Article 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-14-31

Glasgow, R. E., Harden, S. M., Gaglio, B., Rabin, B., Smith, M. L., Porter, G. C., Ory, M. G., & Estabrooks, P. A. (2019). RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Haldane, V., Chuah, F. L. H., Srivastava, A., Singh, S. R., Koh, G. C. H., Seng, C. K., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2019). Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLOS ONE, 14(5), e0216112. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216112