Experiential learning in clinical pathology using Design Thinking Skills (DTS) approach

Submitted: 14 April 2022

Accepted: 3 August 2022

Published online: 4 October, TAPS 2022, 7(4), 76-82

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-4/CS2780

Eusni RM Tohit1, Fauzah A Ghani1, Hizmawati Madzin3, Intan N Samsudin1, Subashini C Thambiah1, Siti Z Zakariah2 & Zainina Seman1

1Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia; 2Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia; 3Department of Multimedia, Faculty of Computer Science & Information Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

I. INTRODUCTION

Twenty first century learning requires analytical thinking and problem solving; hence, medical educators must design suitable model to prepare learners for challenges in future. Medical teaching and learning are moving towards this direction and use of technology in education is embedded in the process. The role of laboratory testing in patients care is recognised as a critical component of modern medical care (Smith et al., 2010). Ability of practicing physicians to appropriately order and interpret laboratory tests is declining and little attention was given to appropriate medical student education in pathology (Smith et al., 2010).

Clinical Pathology (CP) is a module recently introduced in our medical programme. In depth learning of pathology requires learners to identify appropriate tests and specimen containers, interpret patients’ results with consideration of other factors that may influence them.

Design thinking skills (DTS) is a guided process of thinking where learners’ work in a team and work through to identify problems (patient case), analyse through collaborative learning, provide justification for investigation, interpretation of results, and outline relevant effective management. Experiential learning emphasises the central role of the learners in the educational process by allowing the learner to draw own conclusions and ruminate on meaning of the learned material (Clem et al., 2014). Blending DTS and experiential learning creates a holistic approach to the learning of CP.

II. METHODS

A pilot study was executed amongst year 3 medical students in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. The study was approved by Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects, Universiti Putra Malaysia, (JKEUPM-2019-387). It was conducted over a span of two months outside students’ formal teaching and learning. Inclusion criteria include students who in clinical years and never been expose to Clinical Pathology module. Students were divided into small groups of either 4 or 5 students, and all were equipped with the CP app (Appendix 1) in Android smartphone together with DTS task book. Each group had a clinical pathologist facilitating the four hybrid sessions (physical and online) due to the global pandemic. In brief, phases involved introduction to CP (empathy), case findings (define), laboratory workup (ideation), results interpretation (solution), case approach (prototype), critical analysis (reflection and post-mortem). [Details in Appendix 2]. These were then presented in the final phase of DTS in a simulated grand ward round. Learners went through pre and post-test in CP and were asked to evaluate their experiences using a modified 28 items questionnaire (Appendix 3) using Likert scale score; adapted from a validated experiential learning questionnaire (Clem et al., 2014).

III. RESULTS

Twenty students from Medicine and Surgery posting participated in this pilot study, conducted from 27th April 2021 to 26th June 2021. In general, students were very satisfied with the experiential learning project. Responses of experiential learning and score marks were tabulated in Table 1. The 28 items were divided into 4 subheadings; as for the type of environment used, 66% agreed to the hybrid approach used in running of the project. Seventy-five percent agreed on the active participation in different phases of DTS. Eighty-six percent agreed with the relevance of the content of CP in their teaching and learning towards being a medical professional. Over two third of respondents agreed on utility of the CP learning experience be adapted in their future learning. As per for students’ performance (n=20) in pre and post-test OSCE in pathology, students scored significantly higher mark in all items evaluated as seen in Table 1.

Encouraging responses were recorded from some of the respondents as stated below:

“I enjoyed it very much. I received a lot of clarity on how important clinical pathology is after the session. Even after all these sessions, I even read again and again the clinical pathology notes that I have. I feel I can slowly relate my prior knowledge when it comes to clinical.”

Respondent 1

“In my opinion, I think this research project has given me a lot of benefits such as I can know how to correctly fill in the form to order the lab investigation, understand how to choose the correct tube for each lab investigation. I like this project very much as it can help me in this medical field”

Respondent 2

“I am grateful for being part of this research since I learnt a lot from the sessions. I have learnt about the type of lab investigations and blood tube, the sequence of taking blood as well as the phlebotomy techniques from the sessions which may help me in my future medical career.”

Respondent 3

|

Subheading I |

Agree (%) |

Neutral (%) |

Disagree (%) |

|

|

On the environment of Clinical Pathology used in the experiential learning |

66 |

15 |

19 |

|

|

On the active participation and learning of Clinical Pathology |

75 |

14 |

11 |

|

|

On the relevance of the content of Clinical Pathology module |

86 |

3 |

11 |

|

|

On the utility of Clinical Pathology experience in future learning |

68 |

3 |

29 |

|

|

Subheading II |

Pre-test (/5) |

Post-test (/5) |

||

|

Correct selection of specimen container |

0.6 |

3.5 |

||

|

Correct order of blood draw |

2.5 |

4.0 |

||

|

Correct preanalytical variables identified |

0.3 |

3.0 |

||

|

Relevant information in the laboratory form |

2.3 |

4.0 |

||

|

Interpretation of laboratory tests |

3.5 |

4.5 |

||

Table 1. Responses to the questionnaire, pre and post-test score for OSCE in Clinical Pathology

IV. DISCUSSION

The pilot study conducted has shown to be beneficial for the clinical students who participated in the research.

Using Kirkpatrick model (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2021), students in this pilot study achieved level 2 of the model outcome. As Clinical Pathology is a new subject in the amended curriculum, ‘sensitising’ the students to the importance of Clinical Pathology (CP) is achieved.

Small group teaching practised in this pilot study is in line with other schools who used small group teaching which resulted in close relationship between students & facilitator (Smith et al., 2010). The CP app provided self-directed learning on information about laboratory tests which able to improve students’ performance (Smith et al., 2010). When students worked through their own clinical case, this create inquisitive learners as they were able to do clinical correlation with the laboratory findings of their patients.

Disagreement showed by some of the students’ implied the need to improve implementation and running of the project. Students’ learning preferences varies from visual, aural, reading, and kinaesthetic (VARK) and a suitable approach need to be designed to suit spectrum of students.

Post-test OSCE scores showed improvement in common pathology knowledge required from students. This general knowledge will assist them in other clinical postings in future. CP app provided earlier will be useful as self-directed learning. However, there’s still challenges in developing a standardised approach to assessing students’ knowledge and skills in this area (Smith et al., 2010) which is an avenue for future research.

V. CONCLUSION

Students developed more confidence in CP which is useful for future learning experience in other disciplines and future career.

Notes on Contributors

ERT designed the research, developed the CP app storyboard, created the DTS task book, analysed the results, wrote the manuscript. HM developed the CP application, edited the manuscript. FAG, INS, SCT, SZZ, ZS revised the protocol, CP app story board, DTS task book, facilitated the project, edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Sufi Firdaus and Rubhan AL Chandran on technical help in assisting the development of CP application and DTS task book.

Funding

This work was supported by Geran Inovasi Pengajaran Pembelajaran2018 /Universiti Putra Malaysia/ Centre of Academic Development (800-2/2/15).

Declaration of Interest

All authors declared there is no conflict of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Clem, J. M., Mennicke, A. M., & Beasley, C. (2014). Development and validation of the experiential learning survey. Journal of Social Work Education, 50, 490-506. https://doi.org/10.1080/1043 7797.2014.917900

Kirkpatrick, J., & Kirkpatrick, W. K. (2021). Introduction to the New World Kirkpatrick model. Kirkpatrick Partners. Retrieved June 7, 2022, from https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Introduction-to-the-Kirkpatrick-New-World-Model.pdf

Smith, B. R., Aguero-Rosenfeld, M., Anastasi, J., Baron, B., Berg, A., Bock, J. L., Campbell, S., Crookston, K. P., Fitzgerald, R., Fung, M., Haspel, R., Howe, J. G., Jhang, J., Kamoun, M., Koethe, S., Krasowski, M. D., Landry, M. L., Marques, M. B., Rinder, H. M., . . . Wu, Y. (2010). Educating medical students in laboratory medicine: A proposed curriculum. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 133(4), 533–542. https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCPQCT9 4S FERLNI

*Eusni Rahayu binti Mohd.Tohit

Department of Pathology,

Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences,

University Putra Malaysia,

43400 Serdang, Selangor

+60397692379

Email: eusni@upm.edu.my

Submitted: 11 March 2022

Accepted: 10 June 2022

Published online: 4 October, TAPS 2022, 7(4), 73-75

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-4/CS2783

Kiyotaka Yasui, Maham Stanyon, Yoko Moroi, Shuntaro Aoki, Megumi Yasuda, Koji Otani & Yayoi Shikama

Centre for Medical Education and Career Development, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan

I. INTRODUCTION

Educational strategies that are effective in one culture may not elicit the expected response when transferred across cultures. For instance, discussion-based learning methods such as problem-based learning, which were developed in Western contexts to foster self-directed lifelong learning (Franbach et al., 2019), are not easy for Asian students to adapt to. The quietness of Asian students, noted in multi-national contexts, is not always due to linguistic or cultural literacy barriers (Remedios et al., 2008) and requires contextual deconstruction to enable effective solution generation. In a Japanese context, we have observed how quietness manifests through insufficient question generation and a lack of spontaneous opinion expression in class. Such attitudes may be interpreted by western standards as lacking initiative and critical thinking (Tavakol & Dennick, 2010) but are in line with Japanese social norms and traditional views of learning. Because effective learning through discussion requires cognitive conflict to facilitate conceptual transformation (De Grave et al., 1996), it is necessary to ease the psychological burden experienced by our students when deviating from inherited cultural habits so that they can comfortably express opinions to embrace such conflicts. In this case study we share how we created a supportive environment to enable Japanese medical students to embrace this behavioural change.

Through our understanding of Japanese cultural norms, we hypothesised that student quietness could be attributed to the following: 1) belief that their question is insignificant and a desire not to impose on the time of others; 2) reluctance to express different opinions which might cause conflict; and 3) risk aversion to making incorrect statements. Reasons 1) and 2) reflect Japanese social norms requiring people to always act with consideration for others, while 3) is related to a Confucian-affected traditional view of learning that values humility for one’s imperfection as a driving force to self-cultivation which potentially reinforces embarrassment when giving incorrect statements. We aimed to address the above points by introducing environmental changes to boost student confidence in the significance of their questions and minimise the psychological burden of expressing their opinions during a class on ethical dilemmas.

II. METHODS

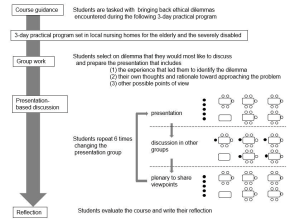

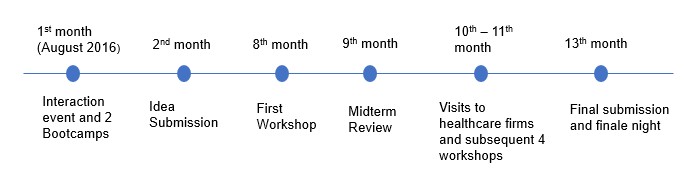

The class was undertaken by 256 first-year medical students at Fukushima Medical University in 2018 and 2019, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram explaining the class: The closed circles represent the presenting group members and their interaction with the rest of the class (open circles) during the discussion and plenary session

A. Building Student Confidence

To minimise the risk aversion and associated anxiety of voicing incorrect opinions, we tasked students to reflect on ethical dilemmas with no clear answer, that they encountered during a 3-day placement in local nursing homes which was presented in groups of 5-6 to the rest of the class. Through removing the expectation of a right answer from the start, we created an atmosphere where students felt comfortable in generating multiple questions rather than being focused on reaching a single ‘correct’ answer.

B. A Conducive Environment for Cognitive Conflict

To break down the barriers of students seeking conformity and agreement during their presentations, we refocused the objective of the session onto the reasoning process of how they considered their ethical dilemma. This reframing supported students to embrace conflicting perspectives without worrying about achieving a consensus.

C. Nurturing a Diversity of Opinions

To facilitate the voicing of minority opinions, we harnessed a positive psychological trait in Japanese culture where pleasure is felt in acting as a collective. Therefore, when opinions were presented to the class, the entire group embraced ownership of the discussion, allowing the individuals who raised the points to remain anonymous. This reduced the potential for personal conflict and allowed diverse opinions to be aired without a loss of face.

At the end of the class, students were asked to evaluate the class using a 4-point Likert scale (good, fairly good, not so good, not good) and to write a reflection on the experience in one to two lines.

III. RESULTS

Out of the 245 students who submitted ratings, 89.9% evaluated the course as “good” or “fairly good”. About half mentioned their surprise at the diversity of opinions and their satisfaction with hearing them, acknowledging that hearing the different perspectives deepened their thoughts, broadened their perspectives, and created new ideas. Satisfaction with being able to express one’s thoughts was stated by a small number of students. Some of the students who chose “not so good” or “not good” pointed out that discussion was tough and required getting used to.

IV. DISCUSSION

When adopting a teaching method developed in a different culture, it should be delivered in the context of one’s own culture to optimise student learning. Once given a supportive environment, Japanese students, previously more content to listen than to actively contribute to discussions, exchanged their ideas and positively encountered cognitive conflict, rather than suffer from low confidence and an aversion to personal conflict. This demonstrates their potential to assimilate different perspectives and advance their thinking, akin to undergoing conceptual transformation. Through this work, we show that the standardisation of teaching methods does not equate to the globalisation of education, but how teaching must be adapted with clear implementation strategies and outcome definition, grounded in the culture to which the learners belong.

V. CONCLUSION

Generalising our adaptations outside of a Japanese context is limited, because of the cultural diversity within Asian countries that brings different challenges to discussion-based learning methods. However, vast numbers of students migrate across cultures in higher education and healthcare training. For universities and clinical training institutions with international students, understanding the barriers and supporting ‘quiet’ students to learn effectively through discussion alongside inherited cultural norms is a priority. This study aids in this understanding by providing an example from a Japanese medical undergraduate context.

Notes on Contributors

Kiyotaka Yasui designed and conducted the course, analysed the student reflections and wrote the manuscript.

Maham Stanyon analysed student reflctions and wrote the manuscript.

Yoko Mori conducted the course facilitation and supported the contextualisation of the results and discussion.

Shuntaro Aoki conducted the course facilitation and supported the contextualisation of the results and discussion.

Megumi Yasuda conducted the course facilitation and supported the contextualisation of the results and discussion.

Koji Otani conducted the course facilitation and supported the contextualisation of the results and discussion.

Yayoi Shikama planned and conducted the course as a course supervisor, analysed the student course ratings and reflections, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Rintaro Imafuku (Gifu University, Gifu, Japan) for constructive advice given during the medical education and research mentoring program sponsored by the Japan Society of Medical Education and Oliver Stanyon for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

De Grave, W. S., Boshuizen, H. P. A., & Schmidt, H. G. (1996). Problem based learning: Cognitive and metacognitive processes during problem analysis. Instructional Science, 24, 321-341. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00118111

Franbach, J. M., Talaat, W., Wasenitz, S., & Martimianakis, M. A. (2019). The case for plural PBL: An analysis dominant and marginalized perspectives in the globalization of problem-based learning. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 24, 931-942. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09930-4

Remedios, L., Clarke, D., & Hawthorne, L. (2008). The silent participant in small group collaborative learning contexts. Active Learning in Higher Education 9(3), 201-216. http://doi.org/10.1177/1469787408095846

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2010). Are Asian international medical students just rote learners? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15, 369-377. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-009-9203-1

*Kiotaka Yasui

1 Hikarigaoka,

Fukushima 960-1295,

Japan

Email: taka-y@fmu.ac.jp

Submitted: 16 July 2020

Accepted: 4 November 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 118-120

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/CS2392

Wai Keung Chui, Han Kiat Ho, Li Lin Christina Chai & Paul J. Gallagher

Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science, National University of Singapore, Singapore

I. THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE IN PHARMACY PRACTICE

Pharmacy practice in Singapore is rapidly evolving with the advent of technological innovations and changes in patient demographics. For instance, the dispensing process in hospitals have been automated; telepharmacy has made access to pharmaceutical services more convenient in the community; an aging population has brought along complex co-morbidities, chronic diseases, polypharmacy and community-based pharmaceutical care services that will require clinical interventions by pharmacists. These examples have raised the question of the “relevance of pharmacists” in the evolving health system. To stay relevant, pharmacists must move from the traditional medication supply (product focus) role to curating the optimal use of medicines by patients (patient focus) in a technology and informatics driven health system. This paradigm shift can only be enabled if the education of pharmacists is suitably re-constructed with outcomes that will future-roof their capabilities in the new healthcare ecosystem. This prompted the Department of Pharmacy at the National University of Singapore (NUS) to make a commitment to review its present programme thereby turning the threats into opportunities for its future pharmacy graduates. This case study reports the approach taken by the Department to re-engineer its curriculum for modern pharmacy practice in the twenty-first century.

II. NEEDS ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In late 2018, a needs analysis was conducted by the Department to inform the design strategies. This was done through structured interviews by informed consent of key opinion leaders, and focused group discussions with alumni and students. The data collected were coded and analysed thematically. Some main themes about the graduates that came through were the weakness in applying their knowledge, their lack of an understanding of the health system and their reluctance to take leadership role. Feedback on the present curriculum included a lack of connectivity between modules that were taught in silos and the structured experiential learning was scheduled too late in the curriculum. It was recommended that a competency-based and integrated curriculum (Husband et al., 2014; Pearson & Hubball, 2012) would help students achieve the necessary competence as a health professional and apply the multidisciplinary knowledge holistically to problem solve. An introduction of systems thinking, and a longitudinal experiential learning programme across the four years will help students understand their future work environment better.

III. PROGRAMME DESIGN

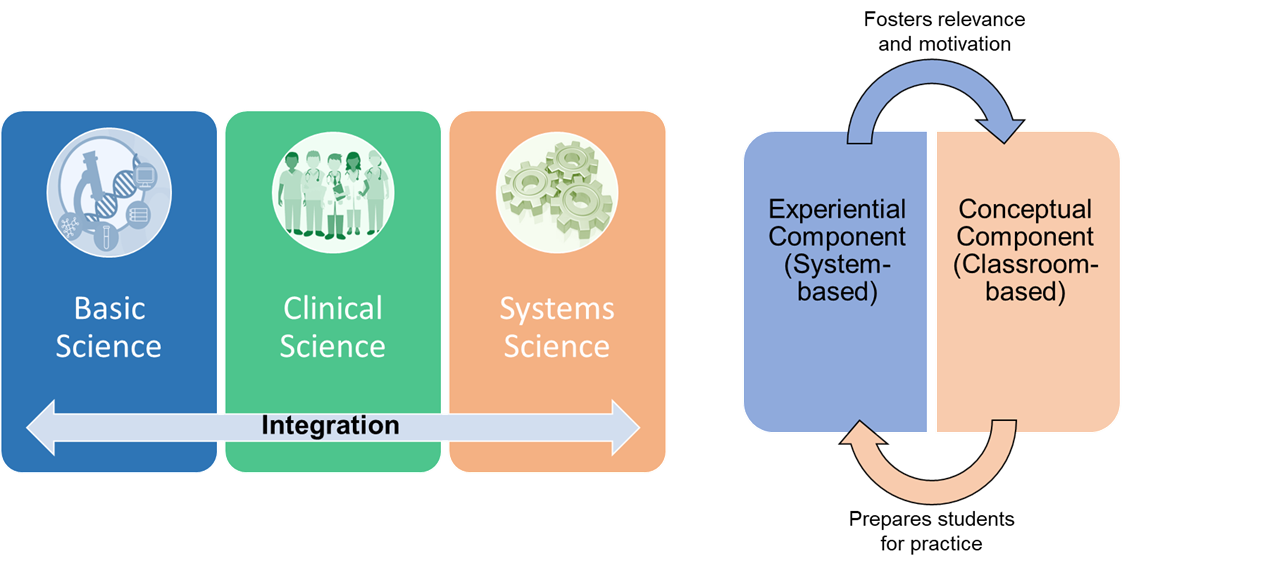

Based on these recommendations, the department had to deconstruct and re-organise the current traditional teaching approach where basic sciences are taught in separate modules in years 1 to 2 while topics in pharmacy practice and therapeutics are introduced from years 3 to 4; with work-place learning happening only after year three. A Curriculum Design Group (CDG) was established to dissect and develop the curriculum. The CDG adapted the key competencies listed in the Association of Faculties of Pharmacy in Canada Educational Outcomes for First Professional Degree Programs in Pharmacy (Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada, 2017) as the basis for the competency-based curriculum. The students will learn to approach pharmacy practice by skilfully integrating sub-competencies of communicator, collaborator, leader-manager, scholar-innovator, health advocate and professional roles into an overarching care provider role. The scholar role is expanded to scholar-innovator role as innovation aligns well with the core value of NUS and is also a critical attribute to safeguard against future disruptions. The key competencies under each role are carefully mapped onto the learning outcomes of themed modules. The themed modules (based on physiological systems) are designed using a theoretical framework of integrating basic, clinical and systems sciences (Gonzalo et al., 2017) (Figure 1). To help students make sense of what they learn, experiential learning is incorporated longitudinally across the four years so that students can apply their theoretical studies at the workplace when they go on clinical placements (Figure 1). This 3-pillar educational framework has been successfully applied in medical education in the US to develop medical competencies and systems thinking among the physicians (Gonzalo et al., 2017); the CDG believed that the same framework would work for pharmacists in Singapore.

Pharmacy graduates must be prepared for a health system that is driven by informatics and technology. Joseph Aoun in his book “Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence” (Aoun, 2017) recommended undergraduate students to acquire technical, data and human literacies, which he collectively refers to as the “humanics”, for them to stay ahead of the technological revolution. Therefore, subjects such as medical sociology, computational thinking, health informatics are included to cultivate the humanics in the pharmacy students. It is envisaged that this approach can better prepare the graduates to work with patients, co-workers, data and technologies in providing quality care. Furthermore, instilling characteristics of a transformational leader and familiarising students to implementation science will take a step closer to grooming the student pharmacists into future leaders.

Figure 1: The theoretical framework of curricular integration. Adapted from Gonzalo et al. (2017) and Pearson and Hubball (2012).

In the new programme, students are made accountable of their own learning through pre-class preparations and interactive team-based learning (TBL) in the classroom. TBL sessions are facilitated by a scientist and a clinician who help students to use integrative thinking to solve the cases. In the laboratory, students will also work in teams to gather scientific data for inquiry-based learning. The impact of the new educational approach will be evaluated against all the four levels of the new world Kirkpatrick Model to determine the effectiveness of the curriculum.

IV. TRANSFORMING PHARMACY EDUCATION IN RESPONSE TO THREATS

The fourth industrial revolution has indeed caused disruptions to pharmacy practice. Pharmacists will have to step forward and be leaders of change when it comes to any matter related to medicines, be it optimising drug use, identifying drug-related problems or recommending cost-effective therapy. Therefore, it is the mission of NUS Department of Pharmacy to respond to the threats by transforming its professional pharmacy programme to one that can future proof its graduates who will be ready to seize new opportunities in a dynamic health system.

Notes on Contributors

Professor Christina Chai is the Head of the Pharmacy Department at NUS. She initiated the EduRx project by calling for the need to redesign the professional pharmacy degree curriculum to better prepare the graduates for the evolving healthcare landscape in Singapore.

Associate Professor Ho Han Kiat, in the capacity of the Deputy Head (Education), supported the curriculum design group in ensuring that the new pharmacy curriculum is closely aligned to both the NUS educational philosophy and the educational outcomes for pharmacy graduates.

Professor Paul Gallagher and Associate Professor Chui Wai Keung are co-leaders of the EduRx project who under their co-leadership worked with the curriculum design group to develop the competency-based and integrative pharmacy programme.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions made by the curriculum design group that comprises the following members: Chng Hui Ting, Fan Wenjie, Han Zhe, Priscilla How, Law Hwa Lin, Eugene Lim Zi Jie, Anson Lim Zong Neng, Tan Bee Jen, Matthias Gerhard Wacker, and Yeo Shao Jie.

Funding

There is no research funding source for the programme review project.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest concerning any aspect of this case study.

References

Aoun, J. (2017). Robot-proof: Higher education in the age of artificial intelligence. The MIT Press.

Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada. (2017). AFPC educational outcomes for first professional degree programs in pharmacy in Canada 2017. https://afpc.info/system/files/public/AFPC-Educational%20Outcomes%202017_final%20Jun2017.pdf

Gonzalo, J. D., Haidet, P., Papp, K. K., Wolpaw, D. R., Moser, E., Wittenstein, R., & Wolpaw, T. (2017). Educating for the 21st-century healthcare system: An interdependent framework of basic, clinical and systems sciences. Academic Medicine, 92 (1), 35-39. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000951

Husband, A. K., Todd, A., & Fulton, J. (2014). Integrating science and practice in pharmacy curricula. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 78 (3), 63. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe78363

Pearson, M. L., & Hubball, H. T. (2012). Curricular Integration in Pharmacy Education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 76 (10), 204. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7610204

*Wai Keung Chui

Department of Pharmacy,

Faculty of Science,

Block S4A, 18 Science Drive 4,

Singapore 117543.

Tel: +65 6516 2933

Email: phacwk@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 23 July 2020

Accepted: 21 October 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 121-123

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/CS2361

Sandra E Carr, Katrine Nehyba & Bríd Phillips

Division of Health Professions Education, School of Allied Health, The University of Western Australia, Australia

I. INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 has caused a major disruption to medical education with many educators making rapid shifts to online teaching (Sandars et al., 2020). Many have had to make critical changes in their instructional delivery (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020; Perkins et al., 2020). These changes may have lasting effects on the shape of educational delivery impacting generations to come (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020). It is important to share these changes and innovations as “Students and educators can help document and analyse the effects of current changes to learn and apply new principles and practices to the future” (Rose, 2020, p. 2132). Our case study examined the transition of small group teaching from blended learning to an emergency remote teaching environment.

II. CONTEXT

At the University of Western Australia, medical students undertake a scholarly activity during the third and final years of their Doctor of Medicine that enables specialisations in research or coursework. Of these students, 27% (n=65) choose a specialisation in Medical Education and graduate having completed 75% of a graduate certificate in health professions education. The first unit, Principles of Teaching and Learning offers an introduction to educational theory, curriculum design, teaching and assessment with a focus on developing teaching skills in small and large group settings and applies blended learning strategies. The final assignment assesses small group teaching techniques and the application of peer assisted learning and feedback. This group assignment requires students to:

a. Develop, plan and deliver a face to face small group teaching activity.

b. Describe and assess the group work processes using an audio journal and group assessment rating.

c. Engage in Peer Observation of Teaching.

With the advent of COVID-19 a change in the assessment was required. The 65 students were informed that the group work would have to occur on line and the small group teaching activity would now be an online Video Presentation. Within the Blackboard learning management system, each group had access to a Discussion Board and a virtual meeting tool to support collaboration and teamwork. The marking rubric was not adjusted so the focus on application of small group teaching techniques remained. The video of the developed small group teaching activity was uploaded along with the audio journal and peer observation of teaching components of the assessment.

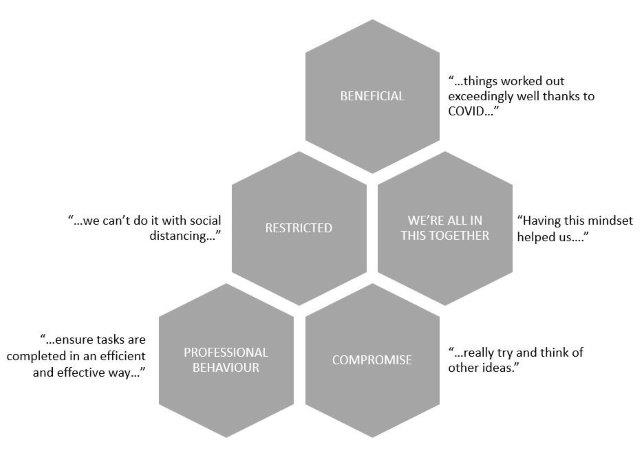

III. STUDENT EXPERIENCE

We undertook a thematic analysis of students’ audio journals and written responses to describe their experience in five broad themes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Student experiences of an online group assignment

Thirty percent of students reported aspects of working online as beneficial, and in some ways an improvement on face-to-face contact. For example, students who otherwise could have experienced difficulty meeting in person were able communicate and meet more easily:

“…we have already managed to organise our first meeting quite swiftly and with ease…”

(S1)

They also reported learning new skills:

“This group project taught me valuable skills when working in an online environment, including how to utilise and contribute in video meetings, share resources and regularly update the group…”

(S25)

“I have also learnt that filming or video is a great medium to communicate messages…once it is done, it can be a very effective tool.”

(S5)

However, not unexpectedly, some of the changes were seen as restrictions. The students talked of being “…banned from entering the hospital…” and of “…having no access…” to equipment or rooms, and “…we can’t do it with social distancing…” This led to feelings of disappointment and frustration, as they tried to find feasible options for the assignment.

“…all four of us were trying to actively brainstorm for an hour, trying to think of something…”

(S60)

“…we had fantastic plans…but unfortunately we didn’t have any of these options…”

(S25)

The perceived restrictions challenged the students’ persistence and adaptability (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020) and led them to compromise. One student, after their group changed their assignment idea from venepuncture to handwashing, said “…we…decided to try and make this idea work the best we could.” (S18). This adjustment and negotiation of ideas led to some innovative and varied submissions, using, for example, dolls; online role-plays; on-screen debate and custom virtual backgrounds.

Another theme that emerged was that of a shared experience, and a sense of we’re all in this together. The use of online communication platforms such as Zoom and Facebook Chat, and the use of shared documents meant that “…everyone could be involved, regardless…” There was evidence of a supportive environment and shared accountability, to ensure that they were “…giving everyone a chance…” and “…everyone seemed equally invested…”

Finally, despite the changes, restrictions and compromise, the students remained task-focussed and were able to plan, allocate, collaborate and communicate in their new online environment. The spread of grades for this assignment was consistent with previous cohorts, suggesting that the change in method was not detrimental to their performance. They were aware of potential dangers of working in this new, unknown way.

“…it will be important for us to be mindful of the risk of losing a professional mindset during our meetings, and divert away from the task at hand.”

(S1)

However, they described the same professional behaviours that would be expected in a face-to-face assignment, such as planning; delegation; effective communication; setting and meeting deadlines; and providing constructive feedback to other team members.

“…our team worked really well together. I suspect things worked out exceedingly well thanks to COVID and lockdown, which forced us to work online.”

(S8)

IV. CONCLUSION

Sklar states that during these unprecedented times “…it is important that our voices are loud about what we have experienced and learned” (Sklar, 2020, p. 9). In this case study we have described an experience of emergency remote teaching, in which a face-to-face small group teaching assignment was moved online. Our experience suggests that, even with its challenges, it was a success. Despite restrictions and compromise the students reported beneficial aspects to working online, and demonstrated a sense of comradery and professionalism while developing digital learning skills that are proving essential for learners and applicable for health professionals in the 21st century.

Notes on Contributors

Sandra Carr conceived the idea of the case study and contributed to the design of the work, gathered the qualitative data and interpretation of the findings. Katrine Nehyba contributed to the design of the case study, searched the supporting and relevant literature, undertook the thematic analysis of the data and constructed the Figure. Bríd Phillips contributed to the design of the work, searched the supporting and relevant literature to construct the rationale and introduction and contributed to the interpretation of the findings. All contributed to confirmation of the themes, the Discussion and Conclusion. All reviewed and contributed to each draft of the paper and approval the final submission.

Acknowledgement

This project was subject to ethical approval by the human ethics committee of the University of Western Australia. Consent was waived in line with the ethical approval obtained.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Ferrel, M., & Ryan, J. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Curēus, 12(3), e7492–e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Perkins, A., Kelly, S., Dumbleton, H., & Whitfield, S. (2020). Pandemic pupils: COVID-19 and the impact on student paramedics. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 17(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.17.811

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(21), 2131–2132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Sandars, J., Correia, R., Dankbaar, M., de Jong, P., Goh, P., Hege, I., Masters, K., Oh, S., Patel, R., Premkumar, K., Webb, A., & Pusic, M. (2020). Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

Sklar, D. (2020). COVID-19: Lessons from the disaster that can improve health professions education. Academic Medicine, 95(11), 1631–1633. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003547

*Sandra Carr

Division of Health Professions Education

The University of Western Australia

35 Stirling Hwy,

Crawley WA 6009, Australia

Tel: +61 64886892

Email: Sandra.carr@uwa.edu.au

Submitted: 16 July 2020

Accepted: 12 August 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 124-127

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/CS2344

Kirsty J Freeman, Weiren Wilson Xin & Claire Ann Canning

Office of Education, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

The Duke-NUS Medical School Simulated Patient programme is instrumental in the development of clinical and behavioural skills in the future medical workforce of Singapore. Starting with a group of 20 passionate individuals in 2007, the Simulated Patient programme currently engages over 100 individuals, of which 58% are Female, 42% are Male; with 46% over 50 years of age. Simulated Patients (SPs) are individuals who are trained to portray a real patient in order to simulate a set of symptoms or problems used for healthcare education, evaluation, and research (Lioce et al., 2020). The SPs are engaged across the curriculum and are specifically trained to provide realistic and convincing patient-centred encounters, as well as identify and give feedback on key elements of interpersonal and communication skills in face-to-face interactions for a unique educational experience.

Medical students at Duke-NUS engage with SPs from their first year, as they learn the fundamental skills of clinical practice (FOCP), the skill of history taking being one of the cornerstones of the programme. Keifenheim et al. (2015) define history taking as “a way of eliciting relevant personal, psychosocial and symptom information from a patient with the aim of obtaining information useful in formulating a diagnosis and providing medical care to the patient”. Several studies have reported on the impact of engaging SPs to teach history taking (Hulsman et al., 2009; Nestel & Kidd, 2003).

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the delivery of on-campus education, requiring medical educators to adapt teaching methods to reflect governmental and institutional restrictions. Whilst journals have been expedient in their ability to publish the experience of educators and students during the COVID-19 pandemic, the experience of other stakeholders are lacking. This paper will describe the experience of simulated patients in adopting telesimulation during a pandemic.

II. ADOPTING TELESIMULATION DURING A PANDEMIC

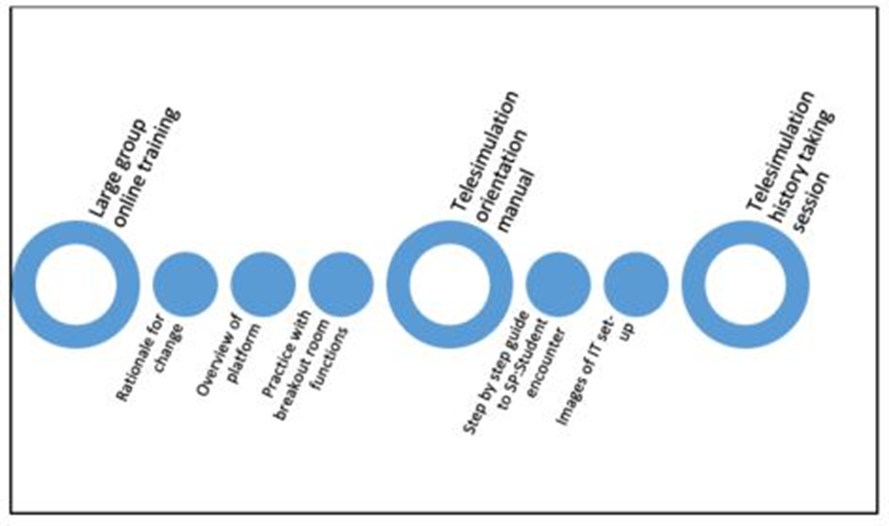

McCoy et al. (2017) define telesimulation as “a process by which telecommunication and simulation resources are utilised to provide education, training, and/or assessment to learners at an off-site location” (McCoy et al., 2017, p. 133). With staff, students and SPs in numerous off-site locations (their own homes), the telecommunication platform adopted for this experience was Zoom. The main reason behind this was it was the platform of choice by the institution when face-to-face teaching was shifted to e-learning, therefore staff and students were familiar with the functionality. To effectively engage our simulation resources, i.e. our SPs, it was essential that we provide an orientation programme that would educate them on the use of telesimulation. Through an online training session, seen in Figure 1, the SPs were introduced to the rationale behind the adoption of telesimulation and the functionality of the Zoom platform. Topics such as how to use the video and audio effectively to build rapport during the interaction as well as functions such as moving between breakout rooms were covered. A telesimulation orientation manual was emailed to all SPs after the session, summarising the online training session, with step by step instructions and screenshot examples on how to use Zoom. See Figure 2 for summary of the orientation programme.

Figure 1. Simulated patient large group telesimulation training

Figure 2. Summary of SP orientation to history taking telesimulation encounter

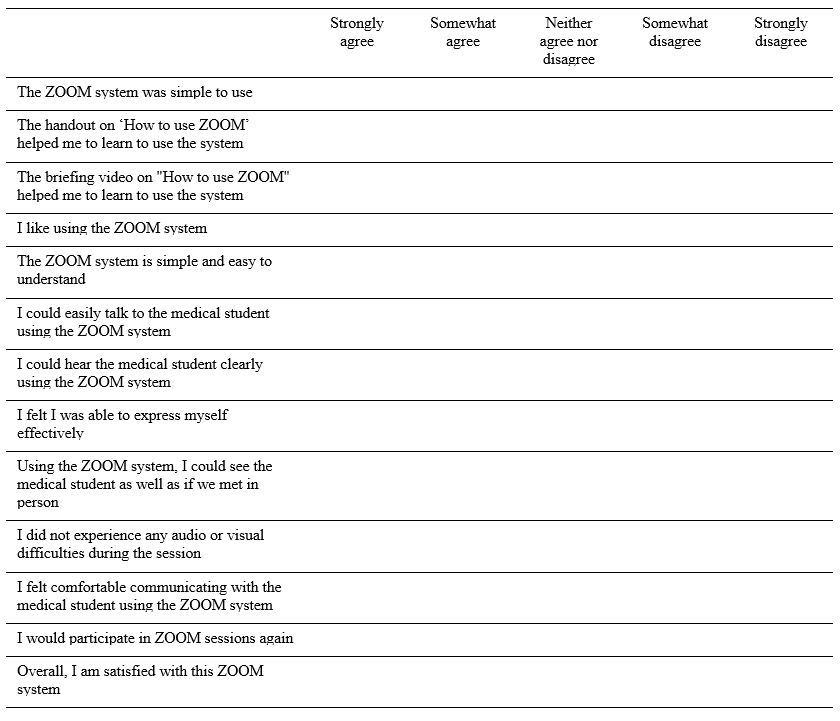

45 SPs participated in a series of tele-simulated history taking encounters for the class of 82 students. All SPs were invited to participate in a post tele-simulation history taking electronic questionnaire. Using a 5-point Likert scale SPs were asked to indicate their agreement on 13 items as seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Likert scale items form post-telesimulation evaluation questionnaire

III. THE SP EXPERIENCE

Of the 45 respondents 64% were male, 36% were female, with 93% stating that they had participated in previous face-to-face sessions with students. Aged between 21 and 71 years, half of the respondents were over 50. To participate in the telesimulation the majority of SPs (67%) utilised a laptop or desktop computer, with 71% reporting that they used a headset. 80% of the SPs had previous experience with video-based calls prior to this session.

Key to the history taking encounters is the ability to communicate clearly. While 11% of SPs did report some technical difficulties related to Wi-Fi connectivity, the majority of SPs (91%) could hear the student clearly and 89% felt they could express themselves effectively. 96% felt they could communicate easily with the student. On whether they could see the medical student as well as they would in a face-to-face interaction, responses were mixed, with SPs acknowledging that the limitations of the telesimulation experience is the non-verbal communication component of the interaction:

“Sometimes, the lighting is not good enough to see the expression on the student’s face”, and “I was not able to observe students’ body posture via zoom as such, I was unable to comment fully on students’ non-verbal communication skills”.

One of the themes that arose in the written feedback was that many SPs appreciated the travelling time saved by being off-site during the telesimulation:

“I used to take 45-60mins to arrive/return at/from a SP rehearsal/session. Now it only takes 15mins to be in the meeting – saves a lot of traveling time; and all is done in the comfort of my home :)”.

Whilst it was acknowledged that telesimulation could not replace the authenticity of face-to-face interactions, the SPs overwhelmingly rated the experience as extremely positive, noting that the online training session and handout helped in learning how to negotiate the online platform. An unexpected benefit that was shared was the sense of connection that the telesimulation experience provided the SPs during a time of lockdown, as they “got to see other SPs”. One respondent shared how they were able to integrate these new skills to maintain social connections:

“…even it has broadened my experience and now been using this app for communication with friends during this CB (circuit breaker)”.

IV. CONCLUSION

As the restrictions around face-to-face teaching due to COVID-19 continues to impact how health professional educators engage SPs in teaching and assessing, this paper demonstrates how to safely and effectively engage the SP workforce during a pandemic. By describing the experience of SPs in adopting telesimulation to teach history taking, we hope that fellow educators across the region can continue to engage SPs in their curriculum.

Notes on Contributors

Kirsty J Freeman is the main author, conceptualised, wrote and revised the manuscript based on comments and suggestions from the other authors. She contributed to the development and facilitation of the simulated patient telesimulation training programme, and conducted the data collection.

Xin Weiren Wilson developed and conducted the simulated patient telesimulation training programme, assisted with data collection, performed the data analysis, and developed the manuscript.

Claire Ann Canning assisted with data collection, and contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript, reviewed and revised drafts.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the simulated patients who took part in the telesimulation programme and were willing to share their experiences. We also wish to acknowledge the Clinical Faculty and Administrative Coordinators of the FOCP programme for adopting telesimulation into the programme.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Hulsman, R. L., Harmsen, A. B., & Fabriek, M. (2009). Reflective teaching of medical communication skills with DiViDU: Assessing the level of student reflection on recorded consultations with simulated patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 74(2), 142-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.009

Keifenheim, K., Teufel, M., Ip, J., Speiser, N., Leehr, E., Zipfel, S., & Herrmann-Werner, A. (2015). Teaching history taking to medical students: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 15(159), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0443-x

Lioce L., Lopreiato J., Downing D., Chang T.P., Robertson J.M., Anderson M., Diaz D.A., Spain A.E., & Terminology and Concepts Working Group (2020). Healthcare Simulation Dictionary (2nd Ed.). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://doi.org/10.23970/simulationv2

McCoy, C. E., Sayegh, J., Alrabah, R., & Yarris, L. M. (2017). Telesimulation: An innovative tool for health professions education. Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training, 1(2), 132-136. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10015

Nestel, D., & Kidd, J. (2003). Peer tutoring in patient-centred interviewing skills: Experience of a project for first-year students. Medical Teacher, 25(4), 398-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159031000136752

*Kirsty J Freeman

Duke-NUS Medical School

8 College Rd,

Singapore 169857

Email: kirsty.freeman@duke-nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 17 May 2020

Accepted: 2 September 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 91-93

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/CS2263

K. Anbarasi1 & Kasim Mohamed2

1Department of Dental Education, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, India; 2Department of Maxillofacial Prosthodontics, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, India

I. INTRODUCTION

Dental practitioners often encounter situations that require customising the prosthesis to satisfy the needs of patients. Artificial devices called dental appliances or prosthesis is custom fabricated for the functional, aesthetic, and psychological wellbeing of patients (Chu et al. 2013). The patient’s complaints may vary from missing natural teeth to extensive maxillofacial defects, and there is no single best rehabilitative therapy for these conditions. Designing our product is the choice, and this demands adaptive expertise, i.e., the ability to generate potential solutions (Mylopoulos et al. 2018). Maxillofacial Prosthodontics applies a variety of learning methods like systematic simulation laboratory exercises, See One, Do One, Teach One (SODOTO method), and supervised clinical practice to train the routine technical skills and clinical practice. To maximise the outcomes in the complex prosthetic treatment, the course specialists designed an “Interdisciplinary Device Development program (IDDP)”—a value-added course for the postgraduates in collaboration with the Biomedical Instrumentation Engineering Faculty of our Institution. IDDP is the first of its kind challenge-based learning model in Dentistry that uses innovations to deal with rehabilitation care beyond routine practice. This paper aims to present our IDDP model and programme outcomes.

II. METHODS

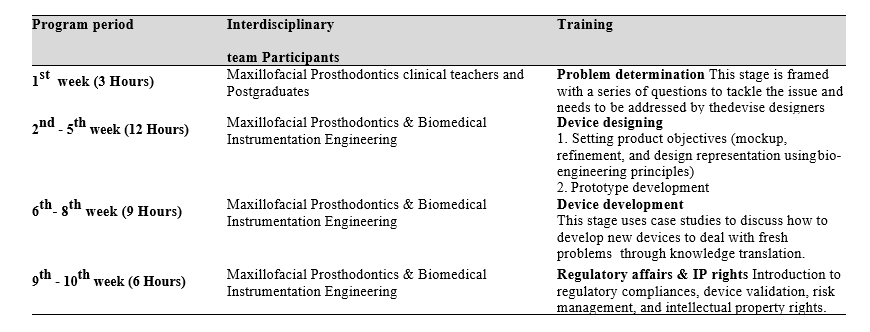

IDDP is structured in three stages referring to problem determination, design, and development. An abstract idea about the essential requirements and intellectual property protection is also included and is scheduled for 3 hours per week for 10 weeks’ (Table 1). The IDDP concept and curriculum were presented in the College Council meeting and subsequently in the Board of Studies and Academic Council. The proposal was approved and permitted implementation.

Table 1: IDDP curriculum framework

Participation in IDDP is mandatory for all postgraduates (PGs) of Maxillofacial Prosthodontics, but knowledge translation into practice is expected only when patients present with unique/challenging conditions. Chances of treating these patients are given for all PGs, but priority is given to those who showed valuable accomplishments in their regular clinical works. Once get allotted with such cases, the PG needs to work with their faculty in-charge, the primary consultant, a faculty member from biomedical engineering, and laboratory technicians.

The device designing demands advanced prosthodontic techniques and the attainment of competency depends on repeated practice. Skill assessment before accustoming it is not a safe practice hence the IDDP is not emphasising on assessments that reflect on summative grade, but performance assessment was made for the postgraduates who have undertaken the task to appraise their diligence, completeness, and problem-solving ability in a standard template, and supporting them to improve their learning.

III. INVENTIONS IN THE CLINICAL GROUNDS

A. Cheek Bumper

A Von Recklinghausen’s disease patient reported with a nodule on the left buccal mucosa and chewing difficulty. The patient expected non-surgical management, and there was a need for invention. Relieving the contact between the mucosal nodule and teeth was suggested as a solution and one PG student turned out the novel idea as an acrylic cheek bumper, an intraoral device that separated the growth 5mm away from the teeth surface. Wearing this appliance at mealtime solved the patient’s problem.

B. Training Pad for Jaw Reposition

A patient has undergone hemimandibulectomy on the right side. After a month, he reported aesthetic concern because of the deviation of the lower third of the face during jaw movements. Denture rehabilitation with a flange is a routine treatment to improve aesthetics. In our discussion, a PG student proposed to reposition the jaws before denture treatment to achieve the jaw compatibility for receiving the denture, hence optimising the success. The team accepted to transform the vision into reality. A prototype was prepared, and an intraoral acrylic pad with retainers was developed. Later the patient was treated with a prosthesis and he expressed his happiness in gaining back the chewing efficiency and confidence

C. Modified Impression Tray to Make Ear Prosthesis

To avoid the shape distortion and to get the adequate fine details in the replica, a postgraduate student in the existing tray pattern did a design modification and got an excellent result.

D. Compression Stent

A patient was referred for the management of a hypertrophic scar following ear piercing. The literature search revealed a solution of stent fabrication to cover the affected ear completely and wearing it full time for a year. The drawbacks like patient discomfort and long-time follow-up were highlighted and a PG student suggested redesigning the compression sent to cover only the scar region using claw type hair clip model. The patient was instructed to wear the stent for 10 to 12 hours per day. At the end of the fifth month, the scar was completely disappeared and she regained the ear lobe shape.

The devices in the process include:

- Mouth opening assisting device to treat trismus.

- Impression tray with size adjustable screws.

- Custom designed intraoral radio-productive device for patients receiving radiotherapy.

IV. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

A supportive curriculum always opens an avenue for innovation. Integration of Biomedical engineering solved the clinical problem by applying engineering principles, formulas, and materials in device designing as the dental specialty lacks the potential to practice the engineering domain. IDDP inspired our postgraduates to take part actively in treatment planning sessions. There is a positive shift in their clinical reasoning skill, describing the treatment options with their pros and cons, and finally specifying the target device by solving the limitations on the existing model or developing an alternative model.

The unresolved factors of IDDP include the struggle to tap the inventive potential of graduate students, their level of commitment, and time allocation. Formal assessment, patient satisfaction survey, student perception, and feedback should be considered.

V. MOVING FORWARD

Incorporating IDDP in the dental curriculum at the national level is the way forward.

VI. CONCLUSION

Our experience in IDDP evidences the innovation that happened on academic grounds. The structured training and opportunity to transform the learning into practice enhanced the confidence level of the clinicians to think out of the box, act as problem solvers, and shape the future health care industry.

Notes on Contributors

Dr. K. Anbarasi, MDS, PhD, devised the presented concept, framed the theoretical framework, wrote the manuscript, and agreed on its final form for submission.

Dr. Kasim Mohamed, MDS, involved in curriculum planning, conducted the programme, contributed to the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to its final form for submission.

Acknowledgment

The authors like to acknowledge the programme coordinators of IDDP.

Funding

The program was supported by the authors’ institution as an academic event.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

Chu, K. Y., Yang, N. P., Chou, P., Chi, L. Y., & Chiu, H. J. (2013). Dental prosthetic treatment needs of inpatients with schizophrenia in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health, 13(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-482

Mylopoulos, M., Kulasegaram, K., & Woods, N. N. (2018). Developing the experts we need: Fostering adaptive expertise through education. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 674-677. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12893

*K. Anbarasi

Faculty of Dental Sciences,

Sri Ramachandra Institute of

Higher Education and Research,

Chennai, India.

Email: anbarasi815@gmail.com

Submitted:5 September 2020

Accepted: 11 January 2021

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 94-96

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/CS2449

Y.G. Shamalee Wasana Jayarathne1,2, Riitta Partanen2 & Jules Bennet2

1Medical Education Unit, Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka; 2Rural Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Australia

I. INTRODUCTION

The mal-distributed Australian medical workforce continues to result in rural medical workforce shortages. In an attempt to increase rural medical workforce, the Australian Government has invested in the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) program, involving 21 medical schools (RHMT program, 2020). This funding requires participating universities to ensure at least 25% of domestic students attend a year-long rural placement during their clinical years and 50% of domestic students experience a short-term rural clinical placement for at least four weeks.

Multiple factors influence selecting a rural medical career pathway. Four basic truths presented by Talley (1990) USA on successful medical career pathways are still pertinent today.

1. Students from rural origin are more likely to return to rural areas of practice.

2. Medical graduates who trained in rural areas are more likely to choose rural practice.

3. General practice is the key discipline of rural health care.

4. Doctors practice close to where they train.

The evidence shows the longer a student spends training in rural area, the more likely they are to work in a rural

area (Kwan et al., 2017; Talley, 1990). Repeated exposure of rural clinical practice promotes rural living and practice, enabling the development of professional and social networks within rural communities (Eley et al., 2008). However, there is a dearth of empirical data on whether brief rural clinical learning experiences increases medical students’ rural medical career intent.

We report a case study on the pilot project of Objective Simulated Bush Engagement Experience (OSBEE), a novel approach to promote rural medical careers to medical students, where second year (of a four year program) medical students participated in a series of rurally themed scenarios and skills stations set in a rural location, with near peer supervisors (The term bush in OSBEE refers to the forested setting where the stations were undertaken).

II. OBJECTIVE AND METHODS

The objective was to evaluate the introduction of a one day immersive rural clinical learning experience in the form of the OSBEE. Metropolitan-based students travelled 280km to attend OSBEE, set in a forested area on a large farm. The students rotated through a series of simulated rural emergency scenarios and skills stations with predominantly third and fourth year medical students as supervisors.

The participants of the study were second year medical students of The University of Queensland (UQ). These students would all be attending a UQ Rural Clinical School (UQRCS) for their third year. To evaluate the influence of this program on their rural medical career intent, on peer-assisted learning and the program itself, a mixed study using a focus group and questionnaire. A focus group discussion conducted by the principal investigator, where informed written consent was obtained from all participants, was audio recorded, verbatim transcribed and thematically analysed. All correspondence was anonymous, and confidentiality maintained. The online questionnaire was administered two weeks after the OSBEE. Frequencies were calculated for questionnaire items. Themes were identified for open ended questions.

III. RESULTS

Identified key themes and quotes from the focus group and open-ended questionnaire questions are presented in Table 1.

|

Key Themes |

Quotes |

|

“Overall a positive impression on OSBEE program”

|

“Awesome learning environment, everyone was so positive and enthusiastic” “I really liked – overall it was good, …” “I think this today is quite eye-opening for me to see what approaches to take when it comes to different scenarios” “For me it was a very collaborative, We could ask questions, it was very friendly” “It kind of was an exam scenario I suppose. But not in a bad way” |

|

About the OSBEE stations |

“I think it’s a lot of real-life scenarios that you could potentially face out in the bush,” “Snake bite was pretty fun” “I don’t know if you guys have heard, where students are actually thrown into these scenarios and they can actually practice their skills.” “There was a lot of clinical practice, but not much clinical reasoning” |

|

“Positive learning during OSBEE”

|

“So I think that really – the most useful part of the day was the similar-ish things but different problems and different contexts and different patients to facilitate memory retention…” “Supervisors were very supportive. Learned a lot from them.” “I feel like the debrief session is enough of a learning. Just enough to know what to do.” |

|

“Positive impression of rural practice” |

“Yeah, it really paints a picture of the typical things, the different situations you might find in a rural scenario.” |

Table 1: Key themes with quotes

The questionnaire response rate by the six study participants was 100 %. All students agreed: “OSBEE was a positive learning experience” and “enjoyed the program”. And 2/3 (4 students) felt “OSBEE encouraged them to consider working in rural context”.

IV. DISCUSSION

Maldistribution of medical workforce is a global concern. Different strategies to address this have been implemented and described in the global literature. Medical schools play an important role in implementing initiatives that best promote rural medical career to grow the rural medical workforce. The OSBEE program provided an enjoyable peer-assisted rural contextualised learning experience and inspired participants to consider rural practice. Although brief rural clinical immersions alone are unlikely to significantly increase rural practice intent, they may enhance the impact of short-term and year-long rural clinical placements on future rural medical workforce.

V. MOVING FORWARD

Whilst our study group was small, and limits the generalisability of our findings, we believe our findings infer brief immersive clinical learning experiences play a role in the promotion of rural medical careers, thus have continued to offer the OSBEE program to early program medical students. However further evaluations of brief (and frequent or repeated) immersive rural clinical learning experiences, on student perceptions of rural medical careers would be useful. Tracking of students involved in these brief rural experiences, as well as short-term and year-long clinical placements would provide valuable insights, to see if participants of the various rural learning experiences do subsequently work in rural areas. Our program and findings may help other medical schools focused on increasing rural medical workforce.

Notes on Contributors

YGSW Jayarathne, MBBS, PG Dip in MEd, MD in MEd was involved the conceptual development, ethics application, data collection including focus group facilitator for the OSBEE evaluation, analysis of the quantitative data, thematic analysis of the qualitative data and the development of the manuscript, including the final approval.

Riitta Partanen, MBBS, FRACGP, DRACOG, General Practitioner, Head of UQRCS was involved in the conceptual development, ethics application, data collection including focus group facilitator for the near peer supervisors, analysis of the quantitative data, thematic analysis of the qualitative data and the development of the manuscript, including the final approval.

Jules Bennet, RN, Masters of Clin Ed, Grad Cert Emerg Nursing, Grad Cert Healthcare Simulation, Lead Clinical Educator – Clinical Skills & Simulation, UQRCS Hervey Bay was involved the conceptual development, ethics application, quantitative data collection, analysis of the quantitative data and the development of the manuscript and final approval.

Funding

This study was supported by funding received from the RHMT grant.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interests related to the content presented in the paper.

References

Australian Government Department of Health. Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program. Retrieved February 20, 2020, from https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/rural-health-multidisciplinary-training

Eley, D. S., Young, L., Wilkinson, D., Chater, A. B., & Baker, P. G. (2008). Coping with increasing numbers of medical students in rural clinical schools: Options and opportunities. Medical Journal of Australia, 188(11), 669-671.

Kwan, M. M., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S., Ranmuthugala, G., Toombs, M. R., & Nicholson, G. C. (2017). The rural pipeline to longer-term rural practice: General practitioners and specialists. PLoS One, 12(7), e0180394

Talley, R. C. (1990). Graduate medical education and rural health care. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 65(12 Suppl), S22-5.

*Y G Shamalee Wasana Jayarathne

Medical Education Unit,

Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences,

Rajarata University of Sri Lanka

Email: wasana@med.rjt.ac.lk

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 54-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/CS2150

Julian Azfar & Rayner Kay Jin Tan

Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

The notion of interdisciplinary health(care) education is an emerging, though not novel concept (Allen, Penn, & Nora, 2006). The module Social Determinants of Health was introduced in the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health in 2018. The module covered important foundational concepts in the study of social determinants of health and explored examples of such determinants over 13 weeks. The module adopted an interdisciplinary approach to public health, drawing from biomedical, psychological and sociocultural perspectives informed by both the natural and social science disciplines. Coursework took the form of student-led seminars, opinion editorial (Op-Ed) and reflective essays, and a fieldwork project involving a chosen group in the community. While the adoption of such an interdisciplinary approach, or the use of the chosen pedagogical approaches are not novel, we present our reflections on the implementation of a novel, interdisciplinary course in public health for undergraduates in Singapore who do not have prior knowledge or expertise in the subject area.

II. AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FRAMEWORK

Past literature on interdisciplinary pedagogies have highlighted the importance of introducing interdisciplinary subjects in the curriculum, drawing on students’ varying backgrounds or disciplines in collaborative learning, and the focus on problems or issues instead of concepts (Friedow, Blankenship, Green, & Stroup, 2012), which have been incorporated in the present module. For example, module content was divided into three sections: “Environments and Communities”, “Globalisation and Work” and “Culture and Being”, providing opportunities for the exploration of public health issues from diverse perspectives. In addition, the focus on student-led seminars and essays, which emphasised the application of concepts to case studies or real-world contexts, helped further students’ understanding of the social determinants of health.

III. ASSESSMENT AND PEDAGOGICAL APPROACHES

The module’s teaching and learning approach was anchored in three main principles – constructivism, critical thinking and questioning, and experiential learning.

A. Constructivism

Constructivism, as a learning theory, posits that individuals engage in meaning-making through interactions between new and their pre-existing knowledge (Piaget, 1971). Each lesson began with a student seminar exploring a guiding question related to the week’s topic, followed by a lecture. Students were given an opportunity to construct their own understandings of the topics based on the assigned readings and compare these interpretations to those of the teacher. In addition, as part of individual written assessment, the Op-Ed and reflective essays further built on the constructivist approach by enabling students to formulate and defend their own judgments in response to other author’s arguments in the Op-Ed essay, as well as synthesising content meaningfully for the reflective essay.

B. Experiential Learning

Experiential learning, which emphasises the role of engagement with real-life experiences and consequences for learning (Kolb, 1984), was also a key feature of the course. To encourage preliminary insights into the necessity for experiential learning in the understanding of social determinants of health, guest speakers such as academics, non-governmental organisation representatives, researchers and even Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioners provided students with first-hand insight into their work and the social contexts of health in Singapore and beyond. The end-of-semester fieldwork project was also an opportunity for students to apply concepts in a relevant way by exploring how social determinants implicated health outcomes for a chosen community in Singapore.

C. Critical Thinking and Questioning

Critical thinking and questioning was an approach that undergirded the conduct of lessons, as well as the different modes of assessment in the module. Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956), for example, was used to scaffold questioning in teacher-led discussions and student seminar presentations. Particularly, in presenting their fieldwork projects, students were also assessed on the types of questions they fielded to presenting groups and the ability to defend their own arguments. Students were tasked with the responsibility of driving the process of class discussions, with the teacher only playing the role of a facilitator.

IV. REFLECTIONS ON COURSE EFFECTIVENESS

Both quantitative and qualitative feedback were obtained from students following the end of the course. Of the 73 students who had taken the course and were invited to provide feedback, a total of 32 students responded (43.8% response rate). Quantitative feedback focused largely on the effectiveness of the course instructors and did not yield rich insights into the effectiveness of the course relative to the qualitative feedback, and thus are omitted here. Qualitatively, students were asked to provide feedback on what they felt were positive aspects of learning in the course. Thematic analysis of the qualitative feedback generated three specific areas where students felt they were positively impacted; firstly, opportunities for creative thinking via assessment methods were favourable; secondly, real-world application of content helped to sharpen knowledge, skills, values; and lastly, flexibility in assessment and choice of topics engaged students more. A summary of these themes and corresponding quotes may be found in Table 1.

|

Themes |

Corresponding quotes |

|

Opportunities for creative thinking via assessment methods were favourable |

“Creativity as a point of marking for presentations, I feel that it stretched our brains and allowed me to think out of the box.” |

|

Real-world application of content helped to sharpen knowledge, skills, values |

“Raised my social awareness of many issues… applicable to our daily lives.”

“Something about health we can share with family and friends…” |

|

Flexibility in assessment and choice of topics engaged students more |

“Seminar-style… presentations were interesting…”

“The module is interesting because it allowed me to explore various aspects of health.” |

Table 1. Themes and corresponding quotes from qualitative responses as positive feedback on design, pedagogy and assessment of the course

V. CONCLUSION

Social Determinants of Health is establishing itself as a popular course amongst undergraduates from different backgrounds. This stems from the constructivist approach that has informed course design, as well as opportunities for critical thinking and questioning, and authentic experiences in teaching, learning and assessment. It is envisioned that by making more disciplinary connections and scaffolding critical thinking and communication throughout the module, the course will continue to enrich the learning experiences of undergraduates from an even more diverse range of specialisations.

Notes on Contributors

Julian Azfar is currently an instructor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. He teaches courses related to the health humanities and is interested in using interdisciplinary curricula to promote critical thinking, perspective-taking and an appreciation of diversity in his courses.

Rayner Kay Jin Tan is a PhD student at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. He has assisted in the planning and teaching of Social Determinants of Health and has been a key facilitator of learning activities throughout the entire duration of the course.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all students, guest lecturers, and coordinators who have contributed to the design and management of the course. The authors would also like to thank the staff at Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health for their support.

Funding

There is no funder for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors confirm that the manuscript is original work of authors which has not been previously published or under review with another journal. The authors confirm that all research meets legal and ethical guidelines and that all possible conflict of interest for this paper has been explicitly stated even if there is none. The authors are not using third-party material that requires formal permission.

References

Allen, D. D., Penn, M. A., & Nora, L. M. (2006). Interdisciplinary healthcare education: Fact or fiction? American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 70(2), 39. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1636929/

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York, NY: Longman.

Friedow, A. J., Blankenship, E. E., Green, J. L., & Stroup, W. W. (2012). Learning interdisciplinary pedagogies. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 12(3), 405-424. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-1625235

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Piaget, J. (1971). Psychology and epistemology: Towards a theory of knowledge. New York, NY: Grossman.

*Julian Azfar

Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health,

National University of Singapore,

12 Science Drive 2, #10-01,

Singapore 117549

Email: ephjam@nus.edu.sg

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2019, 4(1), 65-68

DOI:https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-1/CS2047

Jian Yi Soh

Department of Paediatrics, Khoo Teck Puat-National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

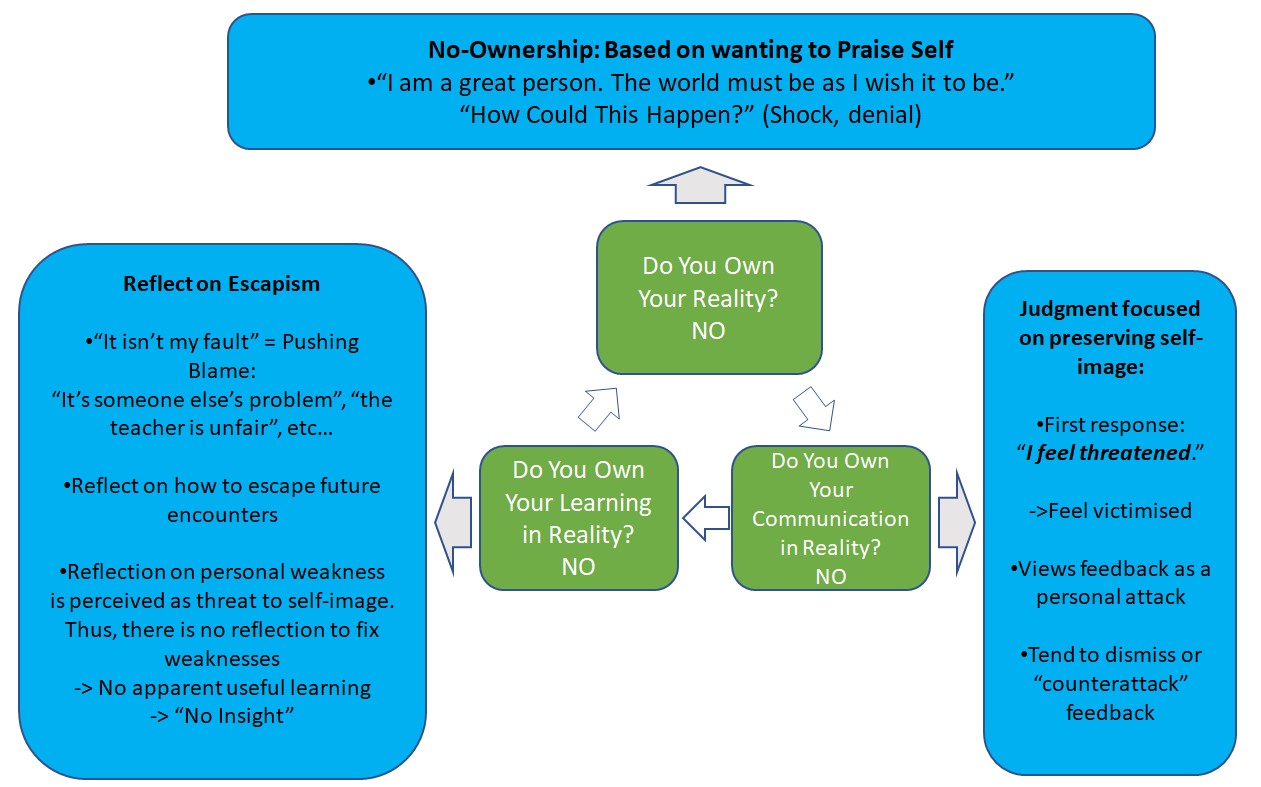

Teachers in various settings worldwide meet with a variety of learners. Some are adept and master their lessons quickly; some less so; and some have persistent difficulties with their lessons. The difficulties can extend beyond the academic; conduct, professionalism and resilience are all important, especially in undergraduate and postgraduate learners. Inability to accept poor results, to admit failure so as to learn from it, can create learners who become withdrawn and resistant to constructive feedback and sincere attempts to help them. “No insight” and “unmotivated” are common terms used in the hallways and discussion rooms to describe these learners. Based on these twin assumptions, teachers strive to extend more help, more resources and more constructive feedback to these learners, and often find that there is little or no improvement despite the vast amounts of energy and time expended.

Although lack of insight may contribute to poor performance, the presence of insight does not correlate with good performance (Carr and Johnson, 2013). It can be deduced that having insight is a requirement for good performance, but insight alone is insufficient for good performance. There are likely other factors, such as behaviour, that may determine final performance.

It is commonly acknowledged that self-regulated learning is an important trait for learners to acquire(Boekaerts, 1997). Taking charge of one’s life, one’s learning, one’s mistakes and learn from these, and be able to balance and sustain that learning journey long-term after leaving formal school. There is great interest in instilling this in learners, just as it is acknowledged that doing so is a complex process that is not yet fully understood(Boekaerts, 1997; Cho, Marjadi, Langendyk, & Hu, 2017).