Why foreign medical students seek abroad elective experience in Japan: The German case

Submitted: 4 February 2023

Accepted: 19 April 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 53-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/CS3003

Maximilian Andreas Storz1 & Rintaro Imafuku2

1Department of Internal Medicine II, Center for Complementary Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Freiburg University Hospital, University of Freiburg, Germany; 2Medical Education Development Center, Gifu University, Japan

I. INTRODUCTION

International medical electives are a central component of the academic curriculum in many medical schools and universities worldwide (Storz, 2022). As short-term clinical immersion experiences, abroad electives are essential in connecting medical faculties and academic hospitals around the globe. They foster cross-cultural exchange, medical skill training, as well as professional identity formation (Imafuku et al., 2021; Storz, 2022). From a global health perspective, abroad electives provide medical students with an opportunity to gain a better understanding of healthcare and medical education in an international context.

Historically, some countries cultivate close relationships in this regard. One example is the bilateral relation between Japan and Germany, which is characterised by a strong economic cooperation and close political dialogue (Hook et al., 2011). As pluralistic democracies, both share fundamental values and are closely tied in many socioeconomic aspects. Traditionally, there has also been a strong partnership in medical sciences between both countries (Horowski, 2018).

Japan is traditionally a popular destination for German-speaking medical students (Storz et al., 2021), and the most frequently reported elective destination in Asia. Nevertheless, little is known about student’s elective experiences in Japan. To address this gap, we reviewed four German open-access online-databases cataloguing elective testimonies and extrapolated key elective characteristics that may allow for a better understanding of abroad elective experience in Japan.

II. METHODS

The employed analysis method with its strengths and drawbacks has been described elsewhere (Storz et al., 2021). In brief, we analysed the 4 largest German open-access clinical elective reports databases called “Famulatur-Ranking” (www.famulaturranking.de), “PJ-Ranking” (www.pj-ranking.de), “ViaMedici” (https:// www.thieme. de/viamedici/medizin-im-ausland-ausland saufenthalt-allgemein-1627.htm), and “Medizinernach-wuchs” (www.medizinernachwuchs.de). Databases allow students to anonymously rate medical electives and to share their experience by uploading reports on a voluntary basis. Key information necessary to upload a report include the precise elective destination (e.g. country, city, hospital name), the elective year, the elective discipline and duration, a subjective elective rating (ranging from 1 to 6, whereby 1 is the best and 6 is the worst grade), and a short comment allowing a brief narrative summary of the elective experience. Generally, elective ratings refer exclusively to a subjective “overall elective experience”, and are not based on a clear rubric to guide students in their rating process. The databases’ search function was used to filter Japan-specific electives. For this particular analysis, all electives from 2005 onwards were considered. Databases were reviewed in September 2022 and data pertaining to any kind of clinical elective experience in Japan was then extrapolated to a Microsoft Excel-File.

III. RESULTS

We extrapolated n=36 Japan elective reports uploaded until 2020. Tokyo was the most frequently reported elective destination, accounting for 47% of reports (n=17), followed by Kyoto (11%, n=4). The remaining elective destinations are shown in Figure 1, which displays regions (coloured) and prefectures of Japan.

Figure 1. Elective destinations in Japan: An overview. Modified from TUBS (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Regions_and_Prefectures_of_Japan_no_labels.svg), based on a license under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

General surgery was the most frequently reported discipline (30.56%, n=11), followed by internal medicine (22.22%, n=8). Surgical disciplines accounted for 45% of reported electives (n=16), whereas internal medicine (including subspecialties) accounted for 1/3 of reports (n=12). The following disciplines accounted for n=3 reports each: Gastroenterology, Gynaecology, Neurology and Radiology.

Thirty-three students shared organisational details of their electives. More than 60% of electives were self-organised (n=20). Thirty-nine percent of electives (n=13) were organised through a bilateral international elective exchange program where a Japanese university partnered with a German university based on a signed memorandum of understanding.

Eight students possessed Japanese language skills to a varying degree (22.22%). Three students reported learning Japanese for one year, while one student learned Japanese for more than two years. The remaining four students did not share any information about their level of Japanese language skills. Despite the rather low percentage of students speaking Japanese, the vast majority of students rated their overall experience in Japan as excellent (grade: A, n=26). Of 28 students, two students rated their elective with the grade B.

Students reported a diverse set of gratifying elective experiences. The large majority of reports (n=33, 97.22%) highly appreciated the Japanese hospitality and the high level of social manners. More than half of students (n=19, 52.78%) reported the impression that students were generally highly respected in Japan. Frequent high-quality teaching and a thorough elective organisation were frequently mentioned (n=27 and n=29 mentions, respectively). Students also valued that they received clear instructions on the first elective day, often receiving in the form of a timetable or schedule, detailing their assignments, classes and teaching opportunities. Fourteen reports explicitly mentioned that a contact person at the international office was always available for questions, and reported their elective to be first-class in terms of organisation and structure.

Many students were surprised that students are denied hands-on experience in Japan by law prior to graduation, although this is usually explicitly mentioned on the elective program homepages. Almost 42% of students (n=15) valued that their hosting institution organised social and cultural events, including get-togethers and language courses. Eating-out after work with other hospital staff was considered an important and highly appreciated team-building strategy.

One third of students (n=12) stated that they received enough free time to explore the Japanese culture. Finally, n=5 students (13.89%) expressed their appreciation for the high technical standard in Japanese hospitals, particularly in terms of medical equipment and workflow.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our descriptive analysis allows for various helpful insights into German medical students’ destinations and experiences during their Japan elective. Students reported gratifying experiences and emphasised the very good organisation of electives in Japan.

Such information may be of paramount importance for host institutions because incoming students may be a double-edged sword. Hosting elective students is time-consuming and requires human resources. In some cases, international elective students may negatively impact the local community in terms of patient care and resource allocation (Storz et al., 2021), Then again, well-structured electives may also increase the reputation of hosting institutions and help foster bidirectional and transnational academic exchange.

As in most cases, benefits and downsides of electives are context-specific, and depend on local elective program structures. Here, students valued their electives and reported a substantial amount of gratifying experiences. Several students explicitly mentioned that their Japan elective was the “best elective during [their] entire time at medical school”. Understanding incoming students’ perspectives is vital for host institutions, and may benefit them in multiple dimensions, e.g. when tailoring elective programs. This may apply in particular to the post-COVID-19 era, where an increase in international student mobility is expected (Storz, 2022). In this context, it is worthy to mention that the majority of electives in our sample was self-organised. Host institutions should be prepared for receiving an increasing amount of elective applications in the post-pandemic years, where the elective landscape will likely be characterised by a more competitive seat-to-applicant ratio.

The reservation must be made that our analysis builds on a small convenience sample (n=36) that is not representative of German medical students in general (Storz et al., 2021). Additional interesting aspects, for example as to whether clinical experiences in Japan affected students’ career or future goals, were not ascertainable from our data. In addition, we were unable to measure whether Japan electives strengthened student’s clinical skills. Our data predominately suggested an increase in cultural competences but due to the cross-sectional nature of our data no reliable statementa can be made. For this, an interview-based approach utilising focused interviews with returnee students would have been more suitable. Regrettably, such an approach was hardly realisable during the past pandemic years.

V. CONCLUSION

Our results enable hosts to understand why foreign students seek electives at their institutions. Said information might be of paramount importance for elective organisers, since well-structured electives may increase the reputation of hosting institutions and help fostering transnational academic exchange.

Notes on Contributors

Maximilian Andreas Storz conceputalised the study, collected the data, performed the formal analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and approved the final version submitted.

Rintaro Imafuku contributed to the project administratition, supported the visualisation and criticially revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the the final version submitted.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Hook, G. D., Gilson, J., Hughes, C. W., & Dobson, H. (2011). Japan’s International Relations: Politics, economics and security (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203804056

Horowski, R. (2018). Japanese medicine and Berlin: A very special and successful relationship. Journal of Neural Transmission, 125(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-017-1800-1

Imafuku, R., Saiki, T., Hayakawa, K., Sakashita, K., & Suzuki, Y. (2021). Rewarding journeys: Exploring medical students’ learning experiences in international electives. Medical Education Online, 26(1), Article 1913784. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2021.1913784

Storz, M. A., Lederer, A.-K., & Heymann, E. P. (2021). German-speaking medical students on international electives: An analysis of popular elective destinations and disciplines. Globalization and Health, 17(1), Article 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00742-z

Storz, M. A. (2022). International medical electives during and after the COVID-19 pandemic – current state and future scenarios: A narrative review. Globalization and Health, 18(1), Article 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00838-0

*Maximilian Andreas Storz

Hugstetter Str. 55

79106 Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

+49 15754543852

Email: maximilian.storz@uniklinik-freiburg.de

Submitted: 20 October 2022

Accepted: 3 January 2023

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 65-67

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/CS2906

Hiroshi Kawahira1, Yoshitaka Maeda1, Yoshihiko Suzuki1, Yuji Kaneda1, Yoshikazu Asada2, Yasushi Matsuyama2, Alan Kawarai Lefor3 & Naohiro Sata3

1Medical Simulation Center, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 2Medical Education Center, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 3Department of Surgery, Jichi Medical University, Japan

I. INTRODUCTION

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has a significant impact on medical education, forcing changes in the curriculum (Rose, 2020). Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, governments and authorities in many countries have imposed online learning on medical students and in many institutions, medical students were not permitted to participate in in-person clinical clerkships or other practical training at university hospitals (Mian & Khan, 2020). Although the surgical clerkship is an important contributing factor to nurture student interest in a surgical career (Khan & Mian, 2020), medical students were excluded from the operating room due to lack of personal protective equipment, and participation in ward duties and training facilities were restricted (Calhoun, et al., 2020).

The purpose of this study is to analyse how the lack of in-person surgical experience and ward duties (online clerkship), among the most important components of a surgical clerkship, affected student interest in a career in surgery. The impact on student perceptions of surgery comparing online learning and onsite clinical clerkship (typical in-person clerkship) was assessed by comparing student satisfaction with the surgical clerkship, changes in interest in a career in surgery, and changes in the image of surgery at the beginning and end of rotations for online and onsite training groups.

II. METHODS

This study was reviewed by the Ethical Review Committee of Jichi Medical University, and no ethical review was required (Reference No. 20-186). A total of 133 fifth-year medical students, all in the same academic year, participated in surgery clerkships from April 2020 to February 2021. All 133 medical students completed clerkships in internal medicine during the previous academic year. The 133 students were divided into eight groups, with 16 or 17 students per group, rotating in surgery every three weeks. The first five groups of that academic year had online lectures only and the last three groups had onsite practice (typical clerkship experience).

Of the 133 students, 124 who provided consent were included in this study. Of these, 79 received online training from April through September 2020, and 45 received onsite clerkship training from October 2020 through February 2021. Moodle, an online learning management system, was used as the platform for online learning, and designed content to be studied on demand. An orientation and lecture with a comprehensive explanation of each aspect of surgical training were synchronous, and online communication with individual students was also conducted. Faculty also communicated online with individual students using Moodle, and individual questions were answered via email as appropriate.

Questionnaires for students in the clerkship were administered using the Moodle platform regardless of whether the clerkship was onsite or online. Questionnaire items addressed: 1. anxiety about surgery, 2. Opinion about difficulty of surgery compared to internal medicine, and 3. interest in surgery. Responses were given as a single choice and were scored using a four-point scale: 1: disagree, 2: somewhat disagree, 3: somewhat agree, and 4: agree.

Comparisons between responses at the beginning and end of the three-week clerkship for all participants were made with the Wilcoxon signed rank test. After calculating differences between the beginning and end of the clerkship, the online and onsite groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cohen’s d was used as an index of effect size, with 0.2 as a small effect size, 0.5 as a medium effect size, and 0.8 as a large effect size. The statistical software used was R 3.6.1 with GUI 1.70 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna).

III. RESULTS

The results for the 124 students enrolled in this study showed that after three weeks of practice compared to the beginning of the study, they were less anxious about surgery (p<0.00001, effect size 0.43), less likely to find surgery difficult compared to study in other departments (p<0.00001, effect size 0.57), and were more interested in surgery as a career (p<0.0001 and effect size 0.38) (See Table 1).

The onsite clinical clerkship resulted in less anxiety about surgery (p = 0.017, effect size 0.41) compared with the online clerkship. There was no significant difference in change of the image of surgery as hard compared to other departments (p = 0.293, effect size 0.21) or change of interest in surgery (p = 0.407, effect size 0.09) in comparing the onsite and the online groups, and the effect size on change of image and interest were also small (See Table 1).

|

|

|

Average |

p* |

p# |

Cohen’s d |

||

|

|

|

Beginning |

Ending |

Beginning – End |

|||

|

How anxious are you about the surgery rotation? |

Total (n=124) |

3.31 |

2.99 |

– |

< 0.00001 |

– |

0.43 |

|

online clerkship (n=79) |

3.38 |

3.19 |

0.19 |

– |

0.017 |

0.41 |

|

|

onsite clerkship (n=45) |

3.20 |

2.64 |

0.56 |

||||

|

How difficult is the surgery rotation compared to other departments? |

Total (n=124) |

3.40 |

2.99 |

– |

< 0.00001 |

– |

0.57 |

|

online clerkship (n=79) |

3.62 |

2.99 |

0.63 |

– |

0.293 |

0.21 |

|

|

onsite clerkship (n=45) |

3.53 |

3.00 |

0.53 |

||||

|

How interested do you feel in surgery as a career? |

Total (n=124) |

3.06 |

3.32 |

– |

< 0.0001 |

– |

0.38 |

|

online clerkship (n=79) |

3.00 |

3.29 |

-0.29 |

– |

0.407 |

0.09 |

|

|

onsite clerkship (n=45) |

3.16 |

3.38 |

-0.22 |

||||

Table 1. Changes in the results of responses at the beginning and end of online and onsite clerkships

p*: Wilcoxon signed rank test, p#: Mann-Whitney U test

IV. DISCUSSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical schools have established integrating digital technology and novel pedagogy (Tan, et al., 2022). Regardless of the clerkship format, three weeks of surgical clinical clerkship resulted in less anxiety about surgery than initially felt, a less daunting image of surgery in comparison to other departments, and significantly higher interest in surgery. However, the effect sizes were moderate (0.43, 0.57, and 0.38), suggesting a positive change in the image of surgery, especially in comparison with other departments. The onsite clinical clerkship group showed a greater decrease in change in anxiety about surgery than the online clinical clerkship at the end of the surgical clinical clerkship (effect size 0.41). The effect size was moderate, suggesting the effectiveness of the onsite clinical clerkship. This study also shows that there were no statistical differences in the feeling of difficulty or interest in a surgical career between the onsite and the online groups. We believe that online content via Moodle was attractive for medical students. Also, medical students could feel the realism of the surgical workplace using Moodle.

V. CONCLUSION

Face-to-face communications with senior physicians are essential to foster an image of the role of physicians to medical students. It is desirable to develop a hybrid type of clinical clerkship that takes advantage of the advantages of the realism of surgery provided by an onsite clinical clerkship and the easy accessibility of educational content of an online clinical clerkship.

Notes on Contributors

Kawahira, Maeda and Suzuki designed the study. Asada and Kawahira constructed the Moodle platform. Kaneda, Lefor and Sata conducted surgical clinical practice. Kawahira and Maeda analyzed data. Kawahira and Lefor wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Yasuko Saikai who did the administrative contact for the students, and all the staffs and surgeons of the Department of Surgery for instructing the students on the clinical clerkship.

Funding

This research was funded by the education and research expenses from Jichi Medical University.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA, 323(21), 2131-2132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Mian, A., & Khan, S. (2020). Medical education during pandemics: a UK perspective. BMC Medicine, 18, Article 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01577-y

Khan, S., & Mian, A. (2020). Medical education: COVID-19 and surgery. British Journal of Surgery, 107(8), Article e269. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11740

Calhoun, K. E., Yale, L. A., Whipple, M. E., Allen, S. M., Wood, D. E., & Tatum, R. P. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on medical student surgical education: Implementing extreme pandemic response measures in a widely distributed surgical clerkship experience. American Journal of Surgery, 220(1), 44-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.04.024

Tan, C. J., Cai, C., Ithnin, F., & Eileen, L. (2022). Challenges and innovations in undergraduate medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic – A systematic review. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 7(3), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/OA2722

*Hiroshi Kawahira

Medical Simulation Center

Jichi Medical University

3311-1 Yakushiji, Shimotsuke, Tochigi

Japan 329-0498

Email: kawahira@jichi.ac.jp

Submitted: 22 July 2022

Accepted: 5 December 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 93-96

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/CS2849

Mian Jie Lim1, Jeremy Choon Peng Wee2, Dana Xin Tian Han2 , Evelyn Wong2

1SingHealth Emergency Medicine Residency Programme, Singapore Health Services, Singapore; 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Singapore raised its Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) from yellow to orange on the 7th of February 2020 after it is first reported unlinked community COVID-19 case on the 6th of February 2020.

The Department of Emergency Medicine (DEM) of Singapore General Hospital (SGH) hosted clinical rotations for medical students (MS) from Duke-NUS Medical School. Their clinical rotations lasted four weeks, during which MS were expected to achieve competence in history taking, physical examination, formulating a management plan, and performing minor procedures.

The local curriculum relies heavily on clinical rotations, during which MS directly contacts patients to fulfil their learning objectives. During DO, clinical postings were postponed, and the term break was brought forward (Ashokka et al., 2020). Restricting MS from entering hospitals and having face-to-face interactions with patients resulted in significant changes to clinical learning. Learning sessions involving direct contact that could not be held over remote platforms were cancelled.

We aimed to discover how MS felt excluded from clinical teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic and how teaching could be improved to support their learning.

II. METHODS

A mixed method of qualitative content analysis and quantitative analysis was performed for this study. Purposive sampling was conducted among all the Duke-NUS MS whose clinical postings to SGH DEM were affected during the COVID-19 outbreak. The link for the online survey form was sent via email or WhatsApp® to 60 MS. Their preferences in learning were assessed by a simple descriptive quantitative analysis of the responses to multiple-choice questions and were followed by an open-ended question whereby template analysis was performed. The consent of each participant was obtained as part of the online survey. The sample of the survey is attached in Appendix A.

III. RESULTS

A. Quantitative Result

Twenty-five MS (42%) were keen to participate in all learning activities at all department areas during normal times if they were trained to wear adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). Twenty-one MS (35%) felt that all learning activities should only be in safe areas of the department with appropriate PPE. Twelve MS (20%) were not keen on having any patient contact.

B. Qualitative Results

1) What other areas of improvement department could introduce about learning during the current pandemic?

Identified main themes, subthemes, and quotes from the open-ended questionnaire questions are presented in Table 1.

|

Main themes /subthemes |

Quotes |

|

1) Balance of training needs with infection control Patient contact is integral to medical education, but it had to be balanced during this pandemic by reducing infection transmission risk. |

“… there is simply no substitute for actually seeing patients for the best learning….” “I think it would be more dangerous to let the students into the wards with a false sense of security (i.e., anticipating limited exposure) than to be fully prepared for all situations.” |

|

2) Respecting medical students’ choice Some respondents felt that MS are all adult learners and should be given the liberty o weigh the risk of infection and benefit of learning through direct patient contact and decide if they want full clinical exposure to patients. |

“should be allowed to choose – whether or not they wish to see patients.”

|

|

2.1) Competency and training needs By preventing all MS from seeing the patients, some felt that this would result in MS not achieving adequate competency as a doctor, subsequently affecting the future healthcare workforce. |

“…We should be allowed to participate in national efforts to quell this disease and to learn as part of this job the national defence expects of us in the future.” |

|

2.2) Compromise in patient safety If patients were to be managed by doctors who lack sufficient clinical exposure during their MS training, their care would be compromised. |

“…It’s helping no one and least of all the patients who will encounter a fresh batch of HOs [House Officers] with little practical experience.” |

|

3) Risk reduction methods Training MS to wear PPE correctly can reduce the risk of transmission significantly and prepare them for future pandemics. |

“To teach and equip students adequately as it would help students with clinical posting and understand the basic importance of PPE in the future as well be well prepared.” |

|

3.1) Remote learning is good but should be engaging and interactive One of the challenges of remote learning is the difficulty faced by MS in maintaining a constantly high level of attentiveness. Hence, it is crucial that remote learning is engaging and interactive. |

“interactive digital simulations” “using polls was a good way to interact.” |

Table 1. Themes, subthemes and medical students’ responses

IV. DISCUSSION

A multi-centre quantitative study was done in the USA by Harries et al. (2021) which showed that 83.4% of MS agreed to return to the clinical environment. These results were comparable with our study’s quantitative result, which showed that 77% of MS were willing to return to the clinical environment during a pandemic.

Spencer et al. (2000) showed that direct patient contact is essential for developing clinical reasoning, communication skills, professional attitudes, and empathy. The findings of this study showed that MS felt that not having direct clinical contact with patients during the pandemic had adverse effects on their learning. Although actual patient contact is desired, this may be countered by the risk of COVID-19 infection, reflected in the first theme of “balance of training needs with infection control” only if adequate risk reduction can patient contact be achieved within a low-risk environment.

MS are all adult learners and should be given liberty on the need for full clinical exposure to patients. However, barring MS from clinical areas also occurred in other countries, especially with the shortage of PPE during the initial emergence of COVID-19 (Rose, 2020).

PPE and infection control training for MS is crucial to ensure clinical teaching can be conducted safely during a pandemic outbreak. Norton et al. (2021) suggested that to avoid injury to patients and healthcare providers and reduce COVID-19-related anxiety among MS, better PPE and infection control training was essential.

A. Limitation

As our study is a mixed qualitative content analysis and quantitative analysis study of a single centre, it is therefore affecting the generalisability of our results. More multi-centre research could be conducted to understand MS’s opinions across Singapore better.

Secondly, another limitation is that our data was collected via an online survey, and we could not follow up with in-depth questions, unlike face-to-face interviews.

The study was done during the early phase of the COVID outbreak and was designed as an initial exploratory study. The results could be used to establish initial information that can help guide future studies.

V. CONCLUSION

From this study, it is essential that medical education needs to be more versatile in future pandemics and consider MS’s opinions. We recommend the incorporation of PPE and infection control training in the undergraduate curriculum, as well as the set-up of an effective online learning platform.

Notes on Contributors

Lim Mian Jie performed the literature review and the template analysis of the data and wrote the manuscript.

Wee Choon Peng Jeremy developed the methodological framework, performed the template analysis of the data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript.

Dana Han Xin Tian submitted the CIRB application, recruited the participants, and collected the data.

Evelyn Wong conceptualised the study, collected the data, advised on the study’s design, and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

IRB exemption for this study was obtained (SingHealth CRIB reference number 2020/2134).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of all the participants.

Funding

No funding is required for this study.

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

Ashokka, B., Ong, S. Y., Tay, K. H., Loh, N. H. W., Gee, C. F., & Samarasekera, D. D. (2020). Coordinated responses of academic medical centres to pandemics: Sustaining medical education during COVID-19. Medical Teacher, 42(7), 762–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1757634

Harries, A. J., Lee, C., Jones, L., Rodriguez, R. M., Davis, J. A., Boysen-Osborn, M., Kashima, K. J., Krane, N. K., Rae, G., Kman, N., Langsfeld, J. M., & Juarez, M. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: A multi-centre quantitative study. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), Article 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02462-1

Norton, E. J., Georgiou, I., Fung, A., Nazari, A., Bandyopadhyay, S., & Saunders, K. E. A. (2021). Personal protective equipment and infection prevention and control: A national survey of UK medical students and interim foundation doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health, 43(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa187

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA, 323(21), 2131. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Spencer, J., Blackmore, D., Heard, S., McCrorie, P., McHaffie, D., Scherpbier, A., Gupta, T. S., Singh, K., & Southgate, L. (2000). Patient-oriented learning: A review of the role of the patient in the education of medical students. Medical Education, 34(10), 851–857. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00779.x

*Lim Mian Jie

Singapore General Hospital,

Outram Road,

169608, Singapore

Email: mianjie.lim@mohh.com.sg

Submitted: 9 May 2022

Accepted: 11 October 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 89-92

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/CS2806

Vidya Kushare1,2, Bharti M K1, Narendra Pamidi1, Lakshmi Selvaratnam1, Arkendu Sen1 & Nisha Angela Dominic3

1Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine & Health Sciences (JCSMHS), Monash University, Malaysia; 2Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 3Clinical School Johor Bahru (CSJB), Monash University, Malaysia

I. INTRODUCTION

For safe practice of medicine, proficiency in anatomy is important. Anatomy is mainly taught in the pre-clinical years. Knowledge retention decreases over time and this will affect clinical and practical application during clinical years (Jurjus et al., 2014; Zumwalt et al., 2007). Literature shows that integrating relevant anatomy with clinical teaching will reinforce the basic concepts and fill these knowledge gaps. Rajan et al. (2016) in their study show that integrating neuroanatomy refresher sessions to clinical neurological case discussions was effective in building relevant knowledge.

Monash University practices a vertically integrated curriculum to promote meaningful learning. In a vertically integrated curriculum, clinical and basic sciences are integrated throughout the program, to provide relevance to basic sciences for clinical practice (Malik & Malik, 2010; Wijnen-Meijer et al., 2020).

As part of the clinical skills development, the Women’s Health (WH) team at Monash university Malaysia in 2010 started episiotomy workshops. Episiotomy is a procedural skill, as future doctors working in Malaysia are expected to know. To perform and repair this surgical procedure safely as well as to identify potential complications, an in-depth knowledge of perineal anatomy is essential.

In 2019, the Anatomy and WH team came together to integrate a refresher anatomy component to the ongoing episiotomy workshops. The objective was to reinforce anatomy relevant to the episiotomy procedure to promote meaningful and lifelong learning.

The anatomy component was integrated virtually because the clinical and preclinical campus are located at different sites about 300km apart. The preclinical Sunway campus is located at Bandar Sunway and the Clinical School Johor Bharu (CSJB) campus is located at Johor Bahru.

Our aim was to see if this approach of virtually integrating refresher anatomy components with the episiotomy workshops will be relevant and beneficial to student learning.

II. METHODS

This cross-campus, blended learning approach, a combination of online (anatomy review session) and face-to-face (episiotomy workshops) sessions, was started in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic. These integrated sessions were conducted for year 5 medical students during their O&G rotation with each group attending the session only once. The anatomy sessions were remotely conducted by the anatomy team. All practical hands-on training workshops were conducted in the clinical skills lab (CSJB campus) by the WH team for the students attending onsite. The two sites were connected via a web conferencing platform/ application (Zoom).

Before the pandemic, the online anatomy sessions and the hand-on workshops were conducted synchronously. The anatomy session was in the form of a 30-minute lecture demo-presentation using various models, cadaveric plastinated specimens and images. This lecture-demo was broadcast virtually from the Monash Anatomy and Pathology e-Learning (MAPEL) Lab in Sunway campus to the clinical skills lab at CSJB. This was followed by the practical training on performing and repairing episiotomy on mannequins supervised by the WH team (see Appendix A).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we altered the delivery format of the anatomy component due to the restrictions. The real time virtual anatomy demo-presentation was replaced by a pre-recorded video lecture uploaded to a Moodle learning management system for students to view asynchronously, before attending the workshop. During the workshop, a knowledge assessment quiz (using online polling application) was remotely conducted by the anatomy team. Each question was discussed in detail with explanation and feedback provided by both teams. This was followed by the practical, hands-on training for students attending onsite in the clinical skills lab at CSJB (see Appendix A).

At the end of the sessions, students responded to a voluntary, anonymised online survey questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of both quantitative questions based on 5-point Likert scale and qualitative open-ended questions.

III. RESULTS

In 2021, we conducted seven integrated workshops, with a total of 59 students attending. Thirty-two students (54%) responded to the survey questionnaire, out of whom the majority (87.5%) had either observed or assisted an episiotomy procedure on real patients. Based on their feedback, most students had viewed the pre-recorded video lectures and found them useful.

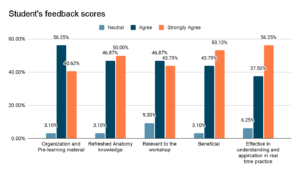

As shown in Figure 1 below, 96% agreed that organization and content of pre-learning materials were effective in achieving the learning outcomes, 96% agreed that this approach refreshed their anatomy knowledge, 91% felt that the anatomy sessions were relevant to the episiotomy workshop, 96% agreed that this approach of integrating anatomy was beneficial and 93% found that this approach was effective in their understanding and application in real time practice.

Figure 1. Student responses in evaluating impact (based on a 5-point Likert scale) of virtual integration of relevant anatomy in the episiotomy workshop

Qualitatively, the responses to open-ended questions were grouped as either most or least beneficial. Most beneficial to the students was that it helped them to revise and correlate relevant anatomy, consolidate and highlight the important concepts. Least beneficial to students were the non-clinical aspects, overlapping content between the uploaded lecture video and the real time zoom session, insufficient models and the lack of online engagement. Overall, the students responded positively towards this learning approach.

IV. DISCUSSION

Based on student feedback, more than 90% responded positively towards this virtual integrated approach of reviewing relevant anatomy during the hands-on workshop. This just-in-time’ review approach, even when conducted virtually, allows them to focus on applying only pertinent knowledge to the hands-on session and subsequently when dealing with real-time episiotomy repair on patients.

The limitations of the study include the internet network bandwidth at the two distant sites and the restrictions posed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Replacing the live anatomy demonstrations, time constraints, social distancing and the use of face shields/face masks made online interactions more challenging.

V. CONCLUSION

This is an ongoing project, requiring further evaluation to assess the impact of this pre-internship training strategy on key procedural skills learning and future practice that is expected in obstetrics.

To conclude, incorporating relevant, refresher anatomy sessions into clinical teaching, even when held virtually, can benefit students to review the core concepts of basic sciences and apply it to clinical practice. This allows for the development of clinical skill competency and ultimately safe patient care.

Notes on Contributors

Vidya Kushare initiated and designed the project, conducted the virtual anatomy review sessions, prepared the video, the quiz and the feedback questionnaire, performed the data collection and data analysis, wrote the manuscript and presented this in a conference.

Bharti M K was involved in the design of the project, conducted the virtual anatomy review sessions, prepared the video and edited the manuscript.

Narendra Pamidi was involved in the design of the project, editing the manuscript and providing references.

Lakshmi Selvaratnam was involved in the planning and development of the project, providing references, providing feedback, writing and editing the manuscript.

Arkendu Sen was involved in the design of the project, providing feedback, editing the manuscript and providing references.

Nisha Angela Dominic initiated and designed the project, conducted the hands-on workshop sessions, prepared the quiz and the feedback questionnaire, performed the data collection, editing the manuscript and providing references.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the technical teams from both campuses: Mr Mah, Ms Nurul, Ms Zafrizal & Mr Abisina.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

Jurjus, R. A., Lee, J., Ahle, S., Brown, K. M., Butera, G., Goldman, E. F., & Krapf, J. M. (2014). Anatomical knowledge retention in third-year medical students prior to obstetrics and gynecology and surgery rotations. Anatomical Sciences Education, 7(6), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1441

Malik, A. S., & Malik, R. H. (2010). Twelve tips for developing an integrated curriculum. Medical Teacher, 33(2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.507711

Rajan, S. J., Jacob, T. M., & Sathyendra, S. (2016). Vertical integration of basic science in final year of medical education. International Journal of Applied & Basic Medical Research, 6(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516X.186958

Wijnen-Meijer, M., van den Broek, S., Koens, F., & ten Cate, O. (2020). Vertical integration in medical education: The broader perspective. BMC Medical Education, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02433-6

Zumwalt, A. C., Marks, L., & Halperin, E. C. (2007). Integrating gross anatomy into a clinical oncology curriculum: The oncoanatomy course at Duke University School of Medicine. Academic Medicine, 82(5), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31803ea96a

*Vidya Kushare

Jln Profesor Diraja Ungku Aziz,

50603 Kuala Lumpur,

Wilayah Persekutuan, Malaysia

+60162440142

Email: vidyakusharee@gmail.com / vidyakushare@um.edu.my

Submitted: 4 May 2022

Accepted: 16 August 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 86-88

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/SC2804

Sok Mui Lim1,2 & Chun Yi Lim2,3

1Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD), Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2 Health and Social Sciences, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 3Department of Child Development, KKH Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Interactive oral assessment has been identified as a form of authentic assessment that enables students to develop their professional identity, communications skills, and helps promote employability (Sotiriadou et al., 2020). It simulates authentic scenarios where assessors can engage students in genuine and unscripted interactions that represents workplace experiences (Sotiriadou et al., 2020). Unlike written examinations, interactive oral questions are not rigidly standardised as students and assessors role-play using workplace scenarios, enabling students to respond to the conversational flow and achieve authenticity (Tan et al., 2021). Using Villarroel et al. (2018) four-step ‘Model to Build Authentic Assessment’, this paper will present the use of oral interactive with first year occupational therapy students. This is within the context of a module named “Occupational Performance Across Lifespan” and students learn about children’s developmental milestones.

II. METHODS

The first step of the Model by Villarroel et al. (2018) is to consider the workplace context. It is important to identify key transferable skills that are needed at typical workplace scenarios. In the job of occupational therapists, they need to meet with caregivers and address their concerns. The key transferable skills include determining whether there is delay in a child’s developmental milestones, communicating with empathy and articulating practical suggestions for caregivers. Thinking critically and communicating persuasively and empathetically, especially in dynamic situations, are important graduate attributes for our students to prepare themselves for the clinical workforce.

The second step of the Model is to design authentic assessment, which involves (1) drafting a rich context; (2) creating a worthwhile task; and (3) requiring higher order skills. In our assessment, students were given a scenario and asked to discuss developmental milestones with parents, identify whether there were areas of concerns from what was reported and provide suggestions if appropriate.

To do this, we trained standardised “actors” / “parents” to share their concerns and correspond with the student individually. As the assessment took place during the pandemic, we used Zoom for corresponding, like therapists conducting teleconsultations. To promote employment opportunities, we included persons with disability as standardised parents. The students were unaware of the disability such as spinal cord injury, as it was conducted on an online platform. We followed the guide on inclusion of persons with disabilities as standardised patients (Lim et al., 2020). The academic staff took the role of the examiner and focused on listening in to the answers provided and writing down feedback for each student.

The third step involves developing the assessment criteria and standard in the form of rubrics and familiarising students with them. To prepare the students, five weeks before the actual assessment, we explained what oral interactive assessments were and introduced the rubrics. They watched videos of one high performing student and one who struggled from previous cohort (with permission sought). They discussed what went well and where the gaps were, followed by pairing up to practice. This helped the students to understand the expected standard, visualise how the oral interactive will take place and learn to evaluate. Three weeks before the assessment, students were given some mock scenarios to practice, and suggestions from the previous cohort on how best to prepare for the assessment.

The fourth step relates to feedback. Feedback can enable students to judge future performances and make improvements within the context of individual assessment. After the assessment, each student was given individual written feedback. The cohort was given group feedback on what they did well and some of the common mistakes. Students who needed more detailed feedback were also given the opportunity to be coached by the Module Lead. At coaching-feedback sessions, the student will watch their video, pause, coached on what they notice, what was done well, and how they can do differently in future. Such feedback sessions are viewed as a coachable moment for educators to develop students in their competency (Lim, 2021).

III. RESULTS

We conducted oral interactive assessments with persons with disability as standardised parents for two cohorts of students (n>200). From the anonymous module feedback, we learnt that students appreciated the assessment as it has real world relevance and enable them to gain professional skills. Some appreciated the opportunity to experience what it felt like interacting with caregivers at their future workplaces. We also noted some students expressed they were more anxious preparing for the oral interactive compared to other forms of assessments. Students shared that they prepared the assessment by remembering the developmental milestones and practise verbalising the concepts out loud with their peers.

IV. DISCUSSION

Students need time to be prepared for a new form of assessment as they may be more familiar with pen and paper examination or report. A few recommendations are suggested:

1) To reduce their anxiety, early preparation is important. Performance anxiety was a common stumbling block. Supporting students in learning strategies to manage performance anxiety can help.

2) For the assessment conversation to be natural, it is important to train the standardised actors on reactions for hit and missed responses from the students.

3) To maintain integrity of the assessment, different scenarios of similar level of difficulties were needed. Educators emphasised the value of learning from the assessment and individualised feedback, such that experience itself becomes intrinsically rewarding.

4) The educator plays the role of the examiner and concentrates to note down the quality of the answers and writes down feedback for each student.

5) Scaffolding students for continuous practice towards workplace competence is important. It is recommended to plan other authentic assessments in the later years of the curriculum such as OSCE.

V. CONCLUSION

Oral interactive assessment provides students with the opportunity to practice and be assessed on workplace competency. While students find themselves more anxious in preparing, they appreciate the real-world relevance and the opportunity to gain professional skills. It is worthwhile to spend effort in designing the assessment in detail, planning authentic scenarios, and preparing students for the experience. As an educator, it is rewarding to witness students developing the ability to demonstrate their competency in a professional manner.

Notes on Contributors

Associate Professor Lim Sok Mui (May) contributed to the conception, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Dr Lim Chun Yi contributed to the execution of the assessment, drafting and reviewing the manuscript.

All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the help of Mr Lim Li Siong, Dr Shamini d/o Logannathan and Miss Elisa Chong for their help in supporting the oral interactive assessments and Miss Hannah Goh for assisting to proofread this manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Lim, S. M. (2021, May 27). The answer is not always the solution: Using coaching in higher education. THE Campus Learn, Share, Connect. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/answer-not-always-solution-using-coaching-higher-education

Lim, S. M., Goh, Z. A. G., & Tan, B. L. (2020). Eight tips for inclusion of persons with disabilities as standardised patients. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(2), 41-44. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/SC2134

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., & Guest, R. (2020). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skill development and employability. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 2132–2148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Tan, C. P., Howes, D., Tan, R. K., & Dancza, K. M. (2021). Developing interactive oral assessments to foster graduate attributes in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.2020722

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., & Herrera-Seda, C. (2018). Authentic assessment: Creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5): 840–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

*May Lim Sok Mui

Singapore Institute of Technology,

10 Dover Drive,

Singapore 138683

+65 6592 1171

Email: may.lim@singaporetech.edu.sg

Submitted: 28 June 2022

Accepted: 16 August 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 54-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/CS2833

Ying Ying Koh* & Caitlin Alsandria O’Hara*

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

*Both authors contributed equally as first authors.

I. INTRODUCTION

Increasing attention has been given to the role of medical humanities in both clinical care as well as in medical education. Medical humanities is defined as an “interdisciplinary perspective that draws on both creative and intellectual methodological aspects of disciplines such as anthropology, art, bioethics, drama and film, history, literature, music, philosophy, psychology, and sociology” (Hoang et al., 2022).

While 80% of health outcomes are related to the social determinants of health (Magnan, 2017), traditional medical education has largely focused on clinical knowledge and skills. Only in recent years have medical schools recognised the importance of medical humanities (Smydra et al., 2021). The strength of medical humanities is the ability to foster a more humanistic clinical practice and build professional social accountability (Pfeiffer et al., 2016).

In Singapore, the Office of Medical Humanities was set up in the SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre to encourage the growth of the medical humanities in the local medical field (Ong & Anantham, 2019). This highlights the growing interest in medical humanities in Singapore.

This paper aims to highlight an innovative approach for medical humanities education through student-led discussion groups, called ‘MedTalks’, conducted in the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Singapore.

II. A GROUND-UP APPROACH TO THE MEDICAL HUMANITIES

MedTalks was started as a student-led platform for medical students to gain exposure to the medical humanities social issues relating to healthcare. Through Socratic seminar-style discussion among students across all three medical schools in Singapore, MedTalks provides a safe space to learn from each others’ thoughts, and crystallise their own ideas and values. In the long term, MedTalks hopes to empower students to take actionable steps towards addressing the social determinants of health in their future clinical practice.

The initiative was inspired by a yearlong liberal arts non-degree programme in a liberal arts university in the United States which the two student-founders of MedTalks had experienced. This yearlong exposure to the liberal arts–particularly medical anthropology, medical history and political science–also informed the approach and development of the content of sessions. For specific sessions, experts or persons with lived experience were invited to be guest co-facilitators. While the liberal arts exposure provided a foundation, the facilitators themselves have made clear during sessions that they are not subject matter experts, but students who are learning from fellow students through discussion.

III. FORMAT OF SESSIONS

MedTalks runs as a series of discussion sessions, which have three key features. Firstly, they are centred around a theme with accompanying pre-session reading materials for participants. These materials consist of excerpts from book abstracts, journal articles, and multimedia sources (e.g speeches, news sites or videos); these act as a primer on the topic and promote questions or ideas which can be raised in the discussions. Preliminary discussion questions are provided for students to ponder and reflect on prior to the session. Secondly, sessions are facilitated by the student-organisers of the programme. These student-organisers also curate the session themes and pre-reading materials prior to the session. Curation of session themes and materials is done based on themes encountered during clinical rotations, national current affairs, and suggestions from student-participants. Thirdly, participants are not required to speak up during the session; they can choose to simply sit in for the discussion. The fact that sessions are student-led and verbal participation is non-obligatory facilitates a more comfortable environment for students in the discussion and allows them to participate in a way that suits their learning.

MedTalks discussions are varied in scope, with several broad subtypes as follows in Table 1:

|

Introductory discussions These provide a first step towards exploring a discipline in the medical humanities. |

Examples of previous introductory discussions include: – An Introduction to Medical History – An Introduction to Medical Anthropology |

|

Sessions which address key ideas, concepts, and theories These explore a concept in greater detail, sometimes through case studies. |

Examples of previous sessions themed around a key concept include: – Social Determinants of Health – Stigma and Health – Intersectionality and Medicine |

|

Sessions which focus on a specific group of patients These dive deeper into a subgroup of patients or an area of health and wellbeing. Guest participants from the patient group are invited to provide their perspective on their lived experience. |

Examples of previous sessions such as these include: – Disability and Medicine – The History of Psychiatry in Singapore |

|

Sessions about the nature of medical practice These explore cultures, norms, and values within medical practice. |

Examples of previous sessions include: – Empathy in Medicine – The Culture of the Medical Profession |

Table 1. Types and formats of MedTalks discussion sessions

IV. A SAFE SPACE TO ENGAGE: OUTCOMES

Since its inception in May 2020, MedTalks has organised 25 peer-to-peer discussion groups, addressing topics which have not been routinely included in the medical school syllabus. Each discussion session is attended by 5 to 15 medical students. Feedback indicated that MedTalks provides an approachable platform for them to engage with topics that they might be new to and which may seem daunting at first, aided by the student-led nature of the sessions and the lack of pressure to verbally participate. Feedback also included that the takeaways from discussions help to shape the way participants understand the patients they encounter in the hospital–to view them in a more holistic manner beyond their presenting medical complaints, and to consider systemic factors that shape their health and wellbeing. In addition, feedback from the programme also demonstrated that participants’ experience with MedTalks contributed to them starting up new community projects to address barriers to healthcare for marginalised groups.

V. TAKEAWAYS AND THE ROAD AHEAD

MedTalks serves as an example of how the medical humanities can be made accessible to medical students, by medical students themselves. MedTalks’ model can be well-replicated by other interested student bodies, to create a culture of discussion and spark interest in the medical humanities among the medical student community. Potential also exists for discussion sessions to be combined with students from other disciplines, such as allied health, the social sciences, or public health, to bring interdisciplinary and interprofessional perspectives to the table and enrich the discussions shared.

Notes on Contributors

Ms Koh Ying Ying is a founding member of the student initiative, MedTalks. She conceptualised this manuscript, and drafted the first and last sections of the manuscript. She read and approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Ms Caitlin O’Hara is a founding member of the student initiative, MedTalks. She conceptualised this manuscript, and drafted the middle sections of the manuscript. She read and approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to sincerely thank their mentors for caringly supporting MedTalks as a student-led initiative.

Funding

There are no funding sources to declare for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Hoang, B. L., Monrouxe, L. V., Chen, K.-S., Chang, S.-C., Chiavaroli, N., Mauludina, Y. S., & Huang, C.-D. (2022). Medical humanities education and its influence on students’ outcomes in Taiwan: A systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, Article 857488. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.857488

Magnan, S. (2017). Social determinants of health 101 for health care: Five plus five. NAM Perspectives, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.31478/201710c

Ong, E. K., & Anantham, D. (2019). The medical humanities: Reconnecting with the soul of medicine. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 48(7), 233–237. Retrieved from https://annals.edu.sg/the-medical-humanities-reconnecting-with-the-soul-of-medicine/

Pfeiffer, S., Chen, Y., & Tsai, D. (2016). Progress integrating medical humanities into medical education: A global overview. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(5), 298–301. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000265

Smydra, R., May, M., Taranikanti, V., & Mi, M. (2021). Integration of arts and humanities in medical education: A narrative review. Journal of Cancer Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-021-02058-3

*Ying Ying Koh

10 Medical Dr,

Singapore 117597

Email: kohyingying@u.nus.edu

Submitted: 12 April 2022

Accepted: 19 August 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 57-60

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/CS2791

Caitlin Hsuen Ng, Siaw May Leong, Arumugam Rajesh Kannan & Deborah Khoo

Department of Anaesthesia, National University Hospital (NUH), Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Airway management is critical for any anaesthetist. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought such skills to the forefront over the last three years. Yet, the outbreak has also disrupted traditional methods of airway skills training and limited the chances of in-person workshops and conferences due to social distancing requirements and demanding manpower needs. To lower the incidence of airway-related morbidity (Joffe et al., 2019), regular and effective instructional methods are needed to maintain airway providers’ skills.

Our Department of Anaesthesia at the National University Hospital (NUH) of Singapore shares our experience conducting small-group refresher sessions, and how that has changed during a pandemic.

II. ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT LEARNING PROGRAMME AND TRAINING NEEDS

Since 2013, our department has been conducting quarter-yearly intra-departmental mini-workshops for airway training. This was to address the airway component of our patient safety strategy, and the unmet need to maintain and upskill airway management techniques for as many anaesthesia providers as possible, who come with an uneven range of seniority and experience with difficult airways. We were challenged to achieve this goal, yet without overly impacting manpower and daily operations. Each session was led by in-house faculty and was open to anaesthesia providers of every level. On occasion, external faculty were invited if they had specific expertise in certain aspects. The syllabus aligned with Difficult Airway Guidelines (Rosenblatt & Yanez, 2022) and was done in a sequential, repeating manner.

III. INTERVENTION: REFRESHER WORKSHOPS IN THE PANDEMIC

As the COVID pandemic came to Singapore around early 2020, our department training was disrupted in many ways. Nationwide social-distancing measures meant that in-person teachings and elective operations were suspended. The increased patient load from the pandemic also meant more manpower redeployed to the frontlines and Intensive Care Units, with an increased focus on infection control and personal protection. In the event airway intervention was required for a patient, the procedure carried significant risks from the aerosol-generating procedures of intubation and mechanical ventilation to both staff and patients. As a result, clinical exposure for airway providers-in-training was severely hampered.

Hence, alterations were made to our existing regular airway training regime. The didactic segment was smoothly transitioned to the videoconferencing platform, Zoom. This had the added benefit of widening the audience to providers who would otherwise have not been able to physically attend. We continued with the hands-on component of the session, but limited participants in the room at any one time in accordance with the room size, ensuring at least one meter between personnel. Strict personal protection was adhered to, requiring all participants to wear N95 masks and perform hand hygiene before and after each station. Participants also assisted in maintaining the cleanliness of the equipment by using Isopropyl Alcohol 70% wipes to decontaminate all surfaces after use. Given the restricted participant size, a call-back system was used when participants had to be turned away. Attendance was tracked using a manual sign-in system. There were no incidences of transmission of COVID-19 because of these workshops.

We focused on airway management while wearing Personal Protective Equipment to better simulate clinical scenarios, bearing in mind the extra physical and cognitive load that airway providers bear in such circumstances (Foong et al., 2020). Specific skills such as how to safely transfer an intubated patient from one ventilator to another were also practiced and video laryngoscope intubation with a limited field of vision. Figure 1 outlines the suggested format, syllabus, and rationale of our mini-workshops, with the intent that it can be modified as needed and replicated in institution-specific settings.

Figure 1. Suggested template and syllabus of in-house refresher workshops

*added from 2020 onwards

IV. EVALUATION OF INTERVENTION DURING THE PANDEMIC

After almost 10 years, we review our airway training refresher sessions, including its adaptation to the COVID pandemic.

Firstly, the sessions were logistically manageable, using pre-existing equipment and a realistic number of faculty. The intimate number of participants not only complied with safe distancing measures but also encouraged more detailed guidance and supervision of practical skills tailored to the participant’s skill level. Flexibility in attendance allowed for continued participation without significantly affecting manpower during the ongoing pandemic.

Simulation-based mini-workshops allowed for continued honing of skills when authentic clinical scenarios were limited. While simulation is unable to replace the actual experience, it has a positive impact on healthcare systems and their patients during times of a pandemic (Santos et al., 2021). The equipment and techniques covered kept abreast of the latest developments and content was curated to help cope with the pandemic by facilitating familiarity and identification of otherwise unexpected problems in managing a COVID airway, prior to real-life encounters and emergent patient care situations. These measures ensure that such high-risk airways are handled in a safe, accurate, and swift manner, maximising first-pass success, and minimising risks to patients and airway providers in the actual situations (Cook et al., 2020).

The workshops were also able to touch on the softer skills required in airway management. The sessions catered to a mix of staff to build teamwork and coordination in a multidisciplinary airway crisis team. Having a shared plan and proper forms of communication are critical in crisis airway situations, even more so with the additional barrier of PPE. Our in-house training has received positive feedback in increasing staff confidence and preparedness for facing airway crises during times of the pandemic.

V. CONCLUSION

As with any skill, practice is essential. During these times of a public health crisis, we need to be adaptable in our instructional methods of continuing training. We believe that our hands-on refresher sessions have been beneficial in enhancing the accessibility of airway management practice even during a pandemic and suggest a syllabus and method that can be replicated and modified to suit the needs and resources of various settings.

Notes on Contributors

Caitlin Ng took lead in drafting and revising of the manuscript, along with aiding in data collection and analysis.

Leong Siaw May contributed to the conceptualisation of the study and revision of the manuscript and was faculty at some of these workshops.

Arumugam Rajesh Kannan contributed to the conceptualisation of the study and revision of the manuscript and was faculty at some of these workshops.

Deborah Khoo conceptualised of study, led the data collection, was faculty at some of these workshops, and contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Our team would like to thank the department of Anaesthesia, NUH, for the provision of equipment, participation, and facilitation of the faculty in the workshops. We were fortunate to have the equipment and facilities at our disposal to conduct such workshops at our convenience. We understand that this privilege may not be generalisable elsewhere.

Funding

There was no funding received for this project, beyond that of the department’s resources.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

Cook, T. M., El-Boghdadly, K., McGuire, B., McNarry, A. F., Patel, A., & Higgs, A. (2020). Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia, 75(6), 785-799. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15054

Foong, T. W., Hui Ng, E. S., Wee Khoo, C. Y., Ashokka, B., Khoo, D., & Agrawal, R. (2020). Rapid training of healthcare staff for protected cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 125(2), e257-e259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.081

Joffe, A. M., Aziz, M. F., Posner, K. L., Duggan, L. V., Mincer, S. L., & Domino, K. B. (2019). Management of difficult tracheal intubation: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology, 131(4), 818-829. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000002815

Rosenblatt, W. H., & Yanez, N. D. (2022). A decision tree approach to airway management pathways in the 2022 Difficult Airway Algorithm of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 134(5), 910-915. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000005930

Santos, T. M., Pedrosa, R. B. S., Carvalho, D. R. S., Franco, M. H., Silva, J. L. G., Franci, D., Jorge, B., Munhoz, D., Calderan, T., Grangeia, T. A. G., & Cecilio-Fernandes, D. (2021). Implementing healthcare professionals’ training during COVID-19: A pre and post-test design for simulation training. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 139(5), 514-519. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2021.0190.R1.27052021

*Caitlin Ng

5 Lower Kent Ridge Road,

Singapore 119074

Email: caitlin_ng97@hotmail.com

Submitted: 27 July 2022

Accepted: 21 September 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 61-63

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/CS2852

Janaka Eranda1, Hewapathirana Roshan2 & Karunathilake Indika3

1Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka; 2Department of Anatomy, Genetics and Biomedical Informatics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka; 3Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

I. INTRODUCTION

Anatomy is considered as one of the key components of undergraduate medical education. Hence, it is important to have a sound knowledge in anatomy to proceed into clinical medicine. Didactic lectures, textbooks, prosected specimens, and cadaveric dissection are the most frequently used anatomy teaching methods. However, with the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic, conventional teaching and learning were challenged. Technology integration for medical education has been increased during COVID-19 in many countries. With the integration of new technologies to the anatomy teaching, the traditional ‘directed self-learning’ started to move towards ‘self-directed learning’. This transformation however, was not without various challenges, especially in low-resource settings such as Sri Lanka (Karunathilake et al., 2020). Augmented reality (AR), Virtual reality (VR), and principles of gamification play an important role in motivation and engagement in medical teaching and learning by enhancing interactivity (Moro et al., 2021). Such technologies also found to have positive impact on students’ spatial understanding and 3D comprehension of anatomical structures.

The objectives of this case study were to identify the context-specific factors in designing AR/VR-based anatomy instructional materials and to assess the student motivation and engagement to use gamification in their studies. The instructional systems design model ADDIE (Molenda, 2003), which is an acronym for Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate, was used to develop the instructional materials in this study since it found to ensure the appropriateness of the materials used in an optimal manner to bring the maximum educational outcome.

II. METHODS

During the study, mixed-method tradition was followed in a Sri Lankan medical faculty from September 2020 to February 2021. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo where the study was exempted from the review process. Purposive sampling was the method adhered recruiting 92 undergraduate medical students and 20 lecturers with the informed consent of the participants. The methodology was phased out according to the ADDIE model.

A. Analysis

A qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with the lecturers. The interviews were informed by the six dimensions of the Hexagonal E-Learning Assessment Model – HELAM (Ozkan & Koseler, 2009) which consists of students’ attitudes, teachers’ attitudes, technology-enhanced learning, content quality, service quality and supportive factors in designing effective E-learning materials. This phase revealed lecturers’ suggestions to develop AR/VR contents in terms of graphical user interfaces, modes of navigation, interactivity, and strategies in incorporating modes of gamification into learning materials.

B. Design

The results of the analysis phase were used to develop a blueprint of the instructional materials integrating the modes of gamification. These were instrumentalised to enhance the motivation and engagement in developed learning materials.

C. Development

An AR/VR application was developed using Unity game engine using 3D anatomy models to project 3D anatomy models over 2D reference images to be used with smart phones and generic VR boxes.

D. Evaluation

This phase consisted of a quantitative study offered to undergraduate students. The self-administered questionnaire with 40 questions of the type 5-point Likert-scale was used to assess participants’ self-reported perceptions of motivation and engagement in self-directed learning. The questionnaire assessed the gamification approach, teaching materials, user interfaces, practicability, physical discomfort, student attitudes on PC-based games, AR/VR apps. The developed apps were used by the students prior to complete the survey.

III. RESULTS

A. Qualitative Study

Lecturers expressed their interest in AR/VR technology with gamification and suggested to link the new AR/VR contents to the existing Learning Management System as the students already have a good engagement with it. They highlighted different modes of gamification such as interactive quizzes, animated interactive 3D anatomy models, teleport targets for VR navigation and video clips to enhance interactivity. Furthermore, they emphasized the importance of the quality of the content, reliability of the information technology services and course administration related factors to improve the overall quality of the learning experience and the sustainability of the new approach.

B. Quantitative Study

The results were organized along the dimensions, gamification, teaching materials, user interfaces, practicability, students’ attitudes toward the technology-enhanced learning and AR/VR apps. The gamification dimension indicated the overall acceptance for the AR/VR techniques and tools and adapting the technology-enhanced learning in formal medical curricula. The highest mean value (4.20 out of the scale ranging from 1 to 5) was observed for the use of the augmented reality app indicating that medical students participated were satisfied with the offered interactivity in the AR/VR apps. The average satisfaction score for gamification, practicability, physical discomfort, teaching materials, user interfaces, student attitudes on the technology-enhanced game and AR/VR app were above satisfactory level (score ≥ 4). The student’s satisfaction on the physical discomfort showed the lowest average score compared to the rest of the dimensions. Further to this, the students had lesser variation in the satisfaction score about the dimension attitudes on the technology-enhanced learning (SD 0.41) compared to the other dimensions. The questionnaire included six questions to measure the level of motivation and engagement. On average, 88% of the students have expressed their willingness to engage with the AR/VR learning style and confirmed that the technology-enhanced learning is a beneficial learning style.

IV. DISCUSSION

The study was conducted to identify the measures to improve motivation and engagement in learning anatomy when integrating technology-enhanced interactive learning contents into the undergraduate medical curriculum. The importance of having a systematic approach is necessary when designing instructional content to obtain a better outcome. The use of principles of gamification improved motivation and engagement which is in line with previous studies (Moro et al., 2022). Sustainability of the technology-enhanced learning was a key concern among the lecturers.

V. CONCLUSION