Empowering students in co-creating eLearning resources through a virtual hackathon

Submitted: 14 March 2023

Accepted: 22 July 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4),84-87

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/CS3263

Hooi Min Lim1, Chin Hai Teo1,2, Wei-Han Hong3, Yew Kong Lee1,2, Ping Yein Lee2 & Chirk Jenn Ng1,4,5

1Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 2E-Health Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 3Medical Education & Research Development (MERDU), Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 4Department of Research, SingHealth Polyclinics, Singapore; 5Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Recommended strategies for the development of eLearning resources have largely focused on teachers rather than students. Co-creating eLearning resources with students has received increasing attention driven by learner-centric design and dialogical learning models (Gros & López, 2016). Engaging students as co-creators is beneficial, leading to better engagement and academic performance as students take ownership of the learning experience (McDonald et al., 2021). However, challenges to engaging students as creators include the lack of clear processes, the lack of content expertise among students, students feeling threatened or uncomfortable with an unfamiliar role, power relations between learners and teachers, and teachers feeling insecure about giving up control of curricular elements.

Hackathons began as computer programming competitions which aimed to solve problems through intensive collaboration over a short time. In healthcare, they have been used to spur innovation in mHealth and surgery. In this paper, we report an innovative approach to engaging students as co-creators in eLearning resource development by using a virtual hackathon as well as the evaluation outcomes of this approach.

II. METHODS

A hackathon approach was used to develop reusable learning objects (RLOs). RLOs are open-access, interactive, multimedia web-based resources based on a single learning objective (Lim et al., 2022). A one-day hackathon was organised to create storyboards on patient safety topics. There were two phases: Stakeholder Engagement and Hackathon Day.

Phase 1 was stakeholder engagement where we engaged the university management and obtained funding support for the program. Next, we engaged the faculty’s Medical Education & Research Development Unit (MERDU), educators (as mentors) and students (as storyboard creators) to join the hackathon.

Phase 2 was the Hackathon Day was held as an online event (via Zoom) during the COVID-19 pandemic. It started with a briefing of RLO co-creation and storyboarding. Students were divided into groups to create their storyboards using an online platform called MURAL (https://www.mural.co/). The mentors were present to provide guidance. The students presented their storyboards to a panel of judges at the end.

We used a pre-post questionnaire survey method to evaluate students’ experience. The pre-hackathon questionnaire examined students’ knowledge and confidence in co-creation using Likert scale. The post-hackathon questionnaire had additional questions examining students’ perception about the hackathon using a Likert scale and open-ended questions (Appendix is available in Figshare repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26502910.v1).

All quantitative data were analysed descriptively using proportion and means. The qualitative data obtained were analysed using the thematic analysis approach. HML coded the answers to the open-ended questions and discussed with the team. The codes were then categorised into themes. Both analyses were conducted using Excel.

III. RESULTS

We reached out to 726 medical and nursing students (Appendix). 22 students participated and were assigned to 7 groups with 2 mentors per group. Seven storyboards were created (Appendix).

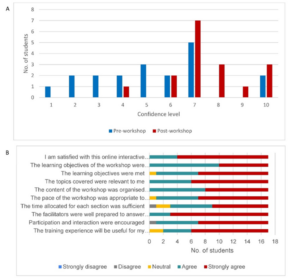

Figure 1. (A) Students’ confidence level in using the co-creation approach to develop digital educational resources (B) Students’ feedback on the hackathon

Only 15.8% (n=3) of students rated their knowledge about co-creation as ‘Good’ or ‘Excellent’ pre-hackathon compared to 82.4% (n=14) students post-hackathon. There was an increasing trend in the students’ confidence level in using the co-creation approach after the hackathon (Figure 1A). Students were satisfied with the hackathon (Figure 1B). They agreed that the learning objectives were clearly defined and met, the topics covered were relevant and the content of the hackathon was organised and easy to follow.

Students expressed their enthusiasm to be co-creators. They liked the interaction with educators and found the guidance helpful.

“Gave me the chance to build something, feels like I’m contributing something positive plus being creative for once in medical school.”

“An exciting one! Looking forward to more hackathons in the medical world, with close interaction and guidance from lecturers!”

Students liked how the online hackathon was conducted using a collaborative tool. “Awesome online tools (Mural)!”. They enjoyed the teamwork between students and educators in co-creating the storyboard.

“And I really enjoy when the teammates and facilitators come together and discuss how to make our topics better as an online learning material.”

Students expressed that they embraced the use of eLearning materials to enhance their learning. They were more encouraged to co-create and use the digital resources.

“I am more encouraged to utilise online resources to increase my knowledge.”

Students expressed that they would carry out more self-directed learning using eLearning objects and technology to strengthen their learning experience.

“I will conduct more self-directed learning and improve my technology skills for better e-learning and view e-learning as a good alternative for face-to-face teaching.”

IV. DISCUSSION

Our case study demonstrated that the hackathon method is feasible for co-creation in learning, fostering partnership between the teachers and learners and offering meaningful and fun learning experiences to the students.

Our results showed that students had an increased level of knowledge and confidence in using the co-creation approach. Students expressed their enthusiasm and appreciated the added values of co-creation in medical education as students played the role of teaching material developers, fostering a positive learning culture. The collaborative effort between teachers and students enhances mutual agreement, partnership, creativity, originality and valuable shared meaning in the development of materials (Bovill, 2020).

The RLOs co-creation process enhanced student teamwork, communication and self-directed learning. Compared to traditional methods of engaging students such as student-led teaching sessions and problem-based learning, the hackathon method added the values of joy and fun of creating learning resources that can be used by their peers. Also, co-creating eLearning resources provided an opportunity to reflect on their learning style, how they use technology as a tool to learn and how they appraise and select high-quality eLearning resources (Bringman-Rodenbarger & Hortsch, 2020).

Our case study had several limitations. The relatively short training and co-creation sessions limited the ability to develop actual RLOs. There was a small sample size with potential selection bias towards already-interested students.

V. CONCLUSION

The co-creation activity using the hackathon method can be an approach to promote interprofessional collaboration and enhance student-educator partnerships in eLearning resource development.

Notes on Contributors

All authors conceptualised and wrote the paper. HML, CHT, WHH and CJN contributed to designing methods and data collection. HML analysed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

We have obtained research ethics approval from the University Malaya Medical Centre Medical Research Ethics Committee for our case study (MREC No: 2024319-13606).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Othniel Panyih, Dr Zahiruddin Fitri Abu Hassan and Mr. Kuhan Krishnan for their assistance in conducting the hackathon. We thank all the educators and students who participated in this hackathon.

Funding

The organisation of this hackathon was funded by the Quality Management and Enhancement Centre (QMEC), Universiti Malaya.

Declaration of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

References

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creation in learning and teaching: the case for a whole-class approach in higher education. Higher Education, 79(6), 1023-1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w

Bringman-Rodenbarger, L., & Hortsch, M. (2020). How students choose e-learning resources: The importance of ease, familiarity, and convenience. FASEB BioAdvances, 2(5), 286-295. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2019-00094

Gros, B., & López, M. (2016). Students as co-creators of technology-rich learning activities in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0026-x

Lim, H. M., Ng, C. J., Wharrad, H., Lee, Y. K., Teo, C. H., Lee, P. Y., Krishnan, K., Abu Hassan, Z. F., Yong, P. V. C., Yap, W. H., Sellappans, R., Ayub, E., Hassan, N., Shariff Ghazali, S., Jahn Kassim, P. S., Nasharuddin, N. A., Idris, F., Taylor, M., … Konstantinidis, S. (2022). Knowledge transfer of eLearning objects: Lessons learned from an intercontinental capacity building project. PLOS ONE, 17(9), Article e0274771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274771

McDonald, A., McGowan, H., Dollinger, M., Naylor, R., & Khosravi, H. (2021). Repositioning students as co-creators of curriculum for online learning resources. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 102-118. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6735

*Lim Hooi Min

Department of Primary Care Medicine,

Faculty of Medicine,

Universiti Malaya

50603 Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia

Email: hmlim@ummc.edu.my

Submitted: 28 August 2023

Accepted: 12 July 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4),81-83

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/CS3229

Tayzar Hein1, Nilar Lwin2 & Ye Phyo Aung1

1Department of Medical Education, Defence Services Medical Academy, Myanmar; 2Department of Child Health, Defence Services Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Children’s Hospital, Myanmar

I. INTRODUCTION

Portfolios, as structured collections of documentation, not only showcase a student’s learning progress and achievements but also foster a self-directed approach to assessing their own performance and setting future goal (Birgin & Adnan, 2007). Existing literature predominantly addresses the broader usage of portfolios across various disciplines, underscoring their role in enhancing reflective practice and competency-based assessments (David et al., 2001). Although portfolios in paediatrics department provide advantages, their implementation encounters substantial obstacles. These include the substantial time and effort required to maintain them, the need for clear guidelines from faculty, and a varying degree of acceptance among students and faculty, who may prefer traditional assessment methods. This study specifically aims to address these challenges by exploring the perceptions of postgraduate students on the use of portfolios in the paediatrics department at the Defence Services Medical Academy.

II. METHODS

Ethical permission for this study was granted in July 2022. The research was conducted over a six-month period from September 2022 to February 2023 within the Paediatrics Department at the Defence Services Medical Academy. To explore the experiences and perceptions of portfolio use in paediatric education, we employed purposive sampling to select six postgraduate paediatric students. We acknowledge the limitations of a small sample size. However, the focus was to gain a preliminary understanding and not to reach data saturation. The study utilised a qualitative research design (Creswell & Creswell, 2017), incorporating focus group discussions to facilitate in-depth dialogue and collect rich qualitative data. Although initially described as employing a ‘grounded theory’ approach, it is more accurate to characterise the methodology as exploratory qualitative research. Data collection involved structured focus group discussions, which were carefully designed to prompt reflection on the students’ experiences with portfolio learning. Data analysis was conducted using manual coding in conjunction with MAXQDA software, facilitating the organisation and thematic analysis of focus group transcripts.

III. RESULTS

The data analysis revealed four key themes regarding the use of portfolios in assessing competencies in the paediatrics department.

A. Theme 1: Value of Portfolios in Assessing Competencies

One participant stated, “Portfolios allowed me to reflect on my learning and track my progress towards meeting my competencies.” Another participant added, “It was helpful to have a structured way of documenting my experiences and reflecting on my strengths and areas for improvement.” The participants also noted that the use of portfolios provided an opportunity for self-directed learning and development.

B. Theme 2: Time and Effort Required

One participant stated, “It was challenging to find the time to update my portfolio regularly, especially with other demands on my time.” Another participant added, “The process of compiling evidence and reflecting on my experiences was more time-consuming than I anticipated.” The participants noted that clear guidelines and expectations were necessary to ensure the success of the portfolio assessment process.

C. Theme 3: Need for Feedback and Support

One participant stated, “I appreciated receiving feedback from my supervisors on my portfolio, as it helped me to identify areas for improvement and set goals for the future.” Another participant added, “It was helpful to have regular check-ins with my supervisors to discuss my progress and receive support and guidance.” The participants noted that faculty members needed to be trained in providing feedback and support to ensure the success of the portfolio assessment process.

D. Theme 4: Limited Impact on Career Development

One participant stated, “While portfolios were helpful in documenting my progress towards meeting my competencies, they did not have a significant impact on my career development.” Another participant added, “Portfolios were a useful assessment tool, but they did not provide me with opportunities for networking or career advancement.” The participants noted that additional career development opportunities were necessary to complement the use of portfolios.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Implications for Practice

Building on the insights from this study, the paediatrics department is encouraged to integrate portfolio assessment into its curriculum. The findings corroborate with a study who noted that portfolio use enhances self-directed learning and the documentation of competencies (Jimoyiannis & Tsiotakis, 2016). The comprehensive nature of portfolios allows students to systematically track their progress and reflect on their learning journey, fostering a deeper engagement with educational content. Implementing such assessments can not only enhance learning autonomy but also promote critical reflection among postgraduate paediatric students. This could lead to more personalised educational experiences and potentially improve competency acquisition.

B. Implications for Research

While this study provides preliminary insights into the effectiveness of portfolio assessments, it also underscores a significant gap in the literature regarding long-term impacts on learning outcomes and career progression within paediatric education. To provide a thorough assessment of the practical advantages and drawbacks of portfolio-based learning, studies could use longitudinal designs to follow the professional development of those who have participated in it.

C. Addressing Limitations and Strengthening the Argument

The study is limited by its focus on a small cohort of postgraduate students within one department, which restricts the generalisability of the findings. Moreover, the exploratory nature of the research calls for cautious interpretation. The enthusiasm and perceived benefits reported by participants align with broader educational theories emphasising active learning and continuous assessment (Trowler, 2010).

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study has provided valuable insights into the perceptions of postgraduate students on the use of portfolios in the paediatrics department. The findings suggest that portfolios can be a valuable assessment tool, but clear guidelines and expectations, as well as feedback and support from faculty members, are necessary to ensure its success.

Notes on Contributors

Dr. Tayzar Hein has played a pivotal role as the main author in this research study, contributing significantly to the conception, design, and execution of the investigation into the perceptions of postgraduate students regarding the use of portfolios in the paediatrics department.

In the early stages of the research, Dr. Nilar Lwin played a crucial role in conceptualising and designing the study. Her insights and experience contributed to shaping the research questions and methodology, ensuring a comprehensive exploration of the subject matter.

As a co-author, Dr. Yephyo Aung has been actively involved in the ethical approval process, emphasising the importance of adhering to ethical standards in research. His commitment to ethical considerations has been instrumental in maintaining the credibility and integrity of the study.

Acknowledgement

We extend our sincere appreciation to all those who contributed to the completion of this research study, particularly acknowledging individuals and organisations whose support, guidance, and contributions were instrumental in the research process.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of the DSMA, Ethical Review Board (2/ ERB/ 2022).

Funding

This research is entirely self-funded, as there is currently no external financial support available for the project, necessitating the coverage of all expenses independently.

Declaration of Interest

The authors of this research study declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could potentially influence or bias the outcomes, interpretations, or conclusions of the study. A conflict of interest is defined as any financial, consultant, institutional, or other relationships that may pose a risk of bias or conflict with the objectivity and integrity of the research.

References

Birgin, O., & Adnan, B. (2007). The use of portfolio to assess student’s performance. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 4(2), 75-90. https://www.tused.org/index.php/tused/article/view/673

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications. https://spada.uns.ac.id/pluginfile.php/510378/ mod_resource/content/1/creswell.pdf

David, M. F. B., Davis, M., Harden, R., Howie, P., Ker, J., & Pippard, M. (2001). AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 24: Portfolios as a method of student assessment. Medical Teacher, 23(6), 535-551. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590120090952

Jimoyiannis, A., & Tsiotakis, P. (2016). Self-directed learning in e-portfolios: Analysing students’ performance and learning presence. EAI Endorsed Transactions on e-Learning, 3(10), e7. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.10-3-2016.151120

Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review. The Higher Education Academy, 11(1), 1-15.

*Tayzar Hein

No.94, D-1, Pyay Road,

Mingaladon Township,

Yangon, Myanmar

Postal code – 11021

+95 95188093

Email: dr.tayzarhein@gmail.com

Submitted: 14 December 2023

Accepted: 14 May 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 76-80

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/CS3215

Vanda Wen Teng Ho1 & Kay Choong See2

1Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 2Division of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Residents are vital to the medical workforce, especially for overnight call duties. Transitioning from junior roles to handling overnight calls as senior residents (SRs) can be anxiety-inducing, leading to decline in cognitive performance and fatigue (Weiss et al., 2016). These pose concerns for patient safety and quality of supervision, as SRs often serve as the most senior staff on-site overnight. However, calls offer valuable training opportunities, fostering autonomy, decision-making skills, and preparation for future consultant roles. The challenge is to ensure that overnight calls are safe for both patients and physicians while being conducive to learning.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the health system’s reallocation of manpower substantially increased the workload. While there remains conflicting evidence on the optimal on-call arrangement, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education stipulates a maximum of 24 consecutive hours of direct patient care to safeguard against negative effects of chronic sleep deprivation (Nasca et al., 2010). In our tertiary hospital, two medical SRs performed stay-in overnight calls ranging from 15 to 21 hours (1700-0800h on weekdays and 1100-0800h on weekends). Before each call, SRs started work at 0700h. One SR was in-charge of the intensive care unit (ICU) and the other was on the general medicine floor. During each call, the ICU SR was responsible for supervising 2 stay-in junior residents, 2-5 new patient admissions and 20 existing ICU patients; the general medicine SR was responsible for supervising a team of four stay-in junior residents, 30-50 new patient admissions, and 100-150 existing inpatients. After each call, SRs would continue with the morning ward rounds before ending work. SRs could seek help by calling the duty consultant, who stayed out of hospital.

With limited data on SRs’ call experiences during the pandemic, understanding their perceptions and attitudes would be essential for system improvement and preparation for future challenges. Therefore, we aimed to explore the perceptions, attitudes, and practices of SRs with regards to overnight stay-in calls during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as avenues for improvements in the call system.

II. METHODS

An electronic survey was conducted via monthly email invitation to SRs in the internal medicine department of a 1,200-bed tertiary university hospital between November 2021 and January 2022. All SRs approached had at least three calls per month. Each email invitation was sent to 40 SRs who consisted of the hospital’s on-call medicine pool. Consent was exempt as this was an anonymised survey (NHG DSRB reference number: 2021/00413). Participants were asked to provide their opinions on various aspects of these calls using a 5-point Likert scale. Monthly prompts to complete the survey were issued.

III. RESULTS

Out of the 40 medical SRs surveyed, 20 responded (50% rate). Their education backgrounds were split between the United Kingdom (n=7) and Singapore (n=13). All trained and worked as SRs in the same hospital group for 4-9 years (median 5 years). The specialties represented included advanced internal medicine (4 respondents), endocrinology (4 respondents), geriatric medicine (3 respondents), neurology (2 respondents), rheumatology (2 respondents), and one respondent each from respiratory and critical care medicine, haematology, infectious diseases. Two participants declined to state their specialty.

In terms of perception, SRs generally agreed that calls contributed to their development as specialists and were essential to their training. They found the learning experience during calls to be valuable for exposure to diverse cases, different from their specialist training which mostly occurred during daytime clinical work. In terms of attitude, most SRs felt prepared and confident for their calls. However, around one-quarter expressed doubts about handling difficult call situations. Many SRs believed that the patient experience overnight could be greatly improved. Nearly half perceived overnight patient care quality as compromised, with 95% noting a decline post-call. While the majority felt safe on-call, fifteen SRs agreed that they would ask for help on-call. Worryingly, only 55% were comfortable doing so and 60% preferred having more supervision during calls.

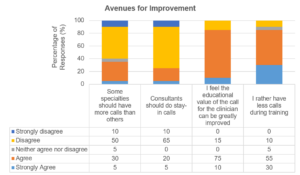

For potential improvements (Fig 1), SRs were asked to rank various choices on a 5-point Likert scale. These choices were specific to overnight calls. Most SRs agreed that the educational value of calls could be enhanced, and they would prefer to have fewer calls during their training. Around two-thirds disagreed with the idea that certain specialties should have more calls or that consultants should perform stay-in calls. Detailed results can be found in the Appendix.

Figure 1. Avenues for improvement for senior residents’ call experience

IV. DISCUSSION

Our survey indicates that SRs felt prepared and recognised the educational value of overnight calls, but there is a clear need for enhanced learning experiences and supervision. Research on junior residents had shown that having in-house overnight hospitalists led to fewer barriers in contacting supervising physicians (Catalanotti et al., 2021) and improved the educational quality of calls (Trowbridge et al., 2010). However, SRs have varying preferences for such supervision, suggesting a need to explore the most suitable form of oversight.

Concerns about compromised patient care during and post-call periods suggest the negative impact of sleep deprivation on performance. Sleep deprivation can impact performance, and the debate around optimal work hours and call types continues, as shorter calls have not demonstrated improved outcomes (Schuh et al., 2011). Alternatives like increasing SRs on call each night should be considered while balancing frequency and stress levels. A larger survey on more hospitalists and SRs from other specialties is needed to confirm these findings and develop appropriate improvements to the on-call system.

V. CONCLUSION

Although the survey was relatively small and limited to one internal medicine department, the findings provide valuable insights for efforts to enhance SRs’ call experiences. Overall, SRs feel confident and safe during overnight calls, but further research is needed to explore and improve three areas: (1) call supervision; (2) learning value of calls; and (3) quality of patient care during and post-call. Graduate medical education programs must prioritise training excellence, resident well-being, and patient care. Our survey revealed challenges associated with overnight calls during a period of high workload marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, which we hope can stimulate the development and study of appropriate interventions.

Notes on Contributors

VWTH and KCS jointly conceptualised this study. VWTH conducted the study, wrote the manuscript, and analysed the data. KCS provided oversight during the study conduct and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study has been approved by the National Health Group Domain Specific Review Board (reference number: 2021/00413).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the participating SRs for their responses.

Funding

This study has no funding sources.

Declaration of Interest

There are no interests to declare.

References

Catalanotti, J. S., O’Connor, A. B., Kisielewski, M., Chick, D. A., & Fletcher, K. E. (2021). Barriers to accessing nighttime supervisors: A national survey of internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(7), 1974-1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06516-4

Nasca, T. J., Day, S. H., & Amis, E. S., Jr. (2010). The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME task force. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363(2), e3. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb1005800

Schuh, L. A., Khan, M. A., Harle, H., Southerland, A. M., Hicks, W. J., Falchook, A., Schultz, L., & Finney, G. R. (2011). Pilot trial of IOM duty hour recommendations in neurology residency programs: Unintended consequences. Neurology, 77(9), 883-887. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c61c3

Trowbridge, R. L., Almeder, L., Jacquet, M., & Fairfield, K. M. (2010). The effect of overnight in-house attending coverage on perceptions of care and education on a general medical service. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 2(1), 53-56. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-09-00056.1

Weiss, P., Kryger, M., & Knauert, M. (2016). Impact of extended duty hours on medical trainees. Sleep Health, 2(4), 309-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2016.08.003

*Dr Vanda Ho

Division of Geriatric Medicine,

Department of Medicine,

National University Health System ,

Tower Block Level 10, 1E Kent Ridge Rd

Singapore 119228

Email: vanda_wt_ho@nuhs.edu.sg

Submitted: 25 October 2023

Accepted: 3 April 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 71-75

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/CS3161

Sulthan Al Rashid1, Syed Ziaur Rahman2, Santosh R Patil3 & Mohmed Isaqali Karobari4

1Department of Pharmacology, Saveetha Medical College and Hospital, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), India; 2Department of Pharmacology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, India; 3Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Chhattisgarh Dental College & Research Institute, India; 4Dental Research Unit – Centre for Global Health Research, Saveetha Medical College and Hospital, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), India

I. INTRODUCTION

Concept maps serve as teaching and learning tools that appear to assist medical students in cultivating critical thinking skills. This is attributed to the adaptability of the tool, acting as a facilitator for knowledge integration and a method for both learning and teaching. The extensive array of contexts, purposes, and approaches in utilising Concept maps and tools to evaluate critical thinking enhances our confidence in the consistent positive effects (Fonseca et al., 2023).

In the realm of medical education, employing concept maps as a learning strategy can prove to be beneficial (Torre et al., 2023). Concept maps, visual representations of learners’ understanding of a set of concepts, have proven to be valuable tools in medical education (Novak & Cañas, 2008). The integration of concept maps as a teaching strategy allows for the depiction and exploration of the relationships among various medical concepts (Ruiz-Primo & Shavelson, 1996). In our instructional approach, instructors employ concept maps during lectures (Appendix 1), emphasising the interconnectedness of key concepts. Students actively participate in creating their own concept maps, facilitating collaborative learning. This flexible approach accommodates diverse learning styles, with students using both concept map notes and textbooks. The final evaluation includes an assessment of students based on their application of concepts outlined in the concept maps, contributing to a well-rounded and adaptable learning experience in medical education.

In this study, we aimed to assess the impact of utilising the concept map teaching technique in conjunction with concept map notes on the academic performance of students.

II. METHODS

In the field of medical education, the adoption of Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) introduced by the National Medical Commission (NMC) for the MBBS 2019 batch has led to the implementation of various innovative teaching approaches. This research, conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) under the reference number 020/09/2023/Faculty/SRB/SMCH, focuses on comparing the academic outcomes of two MBBS batches of Saveetha Medical College and Hospital.

We evaluated the first-year results of the 2020 MBBS batch, which did not receive concept map teaching, and compared them with the first-year results of the 2021 MBBS batch, where concept map teaching was implemented. Students are encouraged to create concept map notes on A3 white sheets, as illustrated in Appendix 2. Furthermore, “subject-wise Saveetha Maps” were developed, incorporating handwritten notes taken by students on each topic.

Generally, it was advised to all the included students to carry on with the books and concept map notes. Furthermore, if they encounter any difficulty in referring the books, they are advised to make use of the concept map notes. In our educational setup, we promoted the combined use of concept maps notes and books for all the students. All students received their compiled handwritten notes, which include all the topics included in their particular subject, as a part of the final evaluation during summative assessment at the end of academic year, and their performance was examined by the examiners.

III. RESULTS

Performance of both the 2020 MBBS batch and the 2021 MBBS batch was assessed. To compare the percentages of first-year results of the 2020 MBBS batch (without concept map) and first-year results of the 2021 MBBS batch (with concept map), a t-test was used, and the results were highly significant (P <0.001) (Table 1 and Appendix 3).

|

Percentage |

N |

Mean |

SD |

t value |

P value |

|

First-year results of the 2021 MBBS batch (with concept map) |

248 |

75.7100 |

7.70000 |

14.953 |

<0.001* |

|

First-year results of the 2020 MBBS batch (without concept map) |

249 |

62.7800 |

11.25000 |

Table 1. Mean comparison for percentages of first-year results of the 2021 MBBS batch (with concept map) and the first-year results of the 2020 MBBS batch (without concept map)

IV. DISCUSSION

For students and physicians who are pursuing a career in medicine, teaching via concept maps has been proven to be an effective tool. However, there has been a lack of exploration regarding its integration with students’ personally crafted concept map notes. The initial year of the curriculum encompasses subjects such as anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry. Our investigation revealed that the average percentage of first-year results for the 2021 MBBS batch, which had been exposed to the concept mapping teaching technique, was 75.7%. In contrast, the mean percentage of first-year results for the 2020 MBBS batch, which had not been exposed to the concept mapping technique, was 62.8%. The disparity in results proved to be statistically significant (P <0.001) as indicated in Table 1 and Appendix 3.

This shows the very good effectiveness of the concept map teaching technique supplemented with students handwritten notes over conventional teaching methods like PowerPoint lectures on students’ academic performance (Niamtu, 2001).

Based on our experience, we wish to emphasise that elucidating key concepts through concept map lectures may prove beneficial for slow learners. Given the extensive topics in the MBBS curriculum, this approach may enable slow learners to prepare for exams more efficiently. Further research should be conducted to see the effect of concept maps on the learning capacity of slow learners. On the other hand, quick learners may leverage the advantage of quickly summarising and identifying main points from these handwritten concept map notes, complementing their book reading efforts. Substituting conventional teaching methods with the concept map teaching approach, enhanced by students’ handwritten concept map notes, significantly improves academic performance.

V. CONCLUSION

According to the findings of our study, we deduce that substituting conventional teaching methods with the concept map teaching approach, enhanced by students’ personally crafted concept map notes, leads to a more significant enhancement in students’ academic performance. In future studies, students may be classified into slow learners and fast learners depending upon the results of the previous year’s final examination and the feedback should be collected from the students in regards to the concept maps teaching approach.

Note on Contributors

Sulthan Al Rashid contributed to the concept, scientific content, data collection, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Syed Ziaur Rahman helped with the manuscript writing, editing, and proofreading.

Santosh R Patil helped with the review and editing of the manuscript.

Mohmed Isaqali Karobari helped with the review and editing of the manuscript.

The final manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted after IRB approval (020/09/2023/Faculty/SRB/SMCH).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the director and medical education unit of Saveetha Medical College and Hospital for providing the details of MBBS students exam results to do this educational research.

Funding

For this study, the authors were not given any funding.

Declaration of Interest

The authors claim to have no conflicts of interest.

References

Fonseca, M., Marvão, P., Oliveira, B., Heleno, B., Carreiro-Martins, P., Neuparth, N., & Rendas, A. (2023). The effectiveness of concept mapping as a tool for developing critical thinking in undergraduate medical education – A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 81. Medical Teacher, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2281248

Niamtu, J. (2001). The power of PowerPoint. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 108(2), 466-484. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200108000-00030

Novak, J. D., & Cañas, A. J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition, 1-36.

Ruiz-Primo, M. A., & Shavelson, R. J. (1996). Problems and issues in the use of concept maps in science assessment tasks [Doctoral dissertation, Brigham Young University]. Provo UT.

Torre, D., German, D., Daley, B., & Taylor, D. (2023). Concept mapping: An aid to teaching and learning: AMEE Guide No. 157. Medical Teacher, 45(5), 455-463. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2182176

*Sulthan Al Rashid

Department of Pharmacology,

Saveetha Medical College and Hospital,

Saveetha Institute of Medical & Technical Sciences (SIMATS),

Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

+919629696523

Email: sulthanalrashid@gmail.com

Submitted: 19 October 2023

Accepted: 25 March 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 58-60

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/CS3159

Wing Yee Tong1, Bin Huey Quek1, Arif Tyebally2 & Cristelle Chow3

1Department of Neonatology, KK Women and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 2Emergency Medicine, KK Women and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 3Department of Paediatrics, KK Women and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Neonatology is considered a ‘niche’ paediatric subspecialty. Most junior doctors posted to the department have limited prior exposure to the neonatal population, and require quick and effective training to help them function safely on the clinical floor. In recent years, postgraduate medical teaching has found the use of blended learning to be effective (Liu et al., 2016). Blended learning is defined as a combination of classroom face-time with online teaching approaches, and there is currently paucity of literature on its efficacy in ‘up-skilling’ relatively inexperienced healthcare professionals in a subspecialty setting. Hence, the aim of this study was to design and evaluate the efficacy of a blended-learning orientation programme in improving neonatal clinical knowledge and procedural skills amongst junior doctors.

II. METHODS

A. Study Setting and Participants

This study was set in the largest academic tertiary paediatric hospital in Singapore.

B. Curriculum Development

We adopted the Kern’s six-step approach for curriculum development (Thomas et al., 2022), as it systematically identifies and addresses learner needs, and its cyclical nature also allows for constant modifications and improvements.

1) Step 1: Problem identification and general needs assessment

We conducted a quantitative survey to identify the general issues with our current programme, which consisted of daily face-to-face, largely didactic lectures over the first month of the posting. We noticed that many junior doctors missed teaching sessions due to work obligations, resulting in ‘piecemeal’ and ineffective learning. The one-month programme was also considered excessively lengthy.

2) Step 2: Targeted needs assessment

Most junior doctors considered themselves to be ‘novice’ learners in neonatology. This emphasised the importance of starting with foundational teaching concepts to avoid overwhelming them. Junior doctors also preferred interactive learning methods.

3) Step 3: Goals and objectives

Our main objective was for the junior doctors to be competent and safe members of the clinical team, with basic neonatal clinical knowledge and the ability to perform and assist in neonatal procedures.

4) Step 4: Educational strategies: Course content development

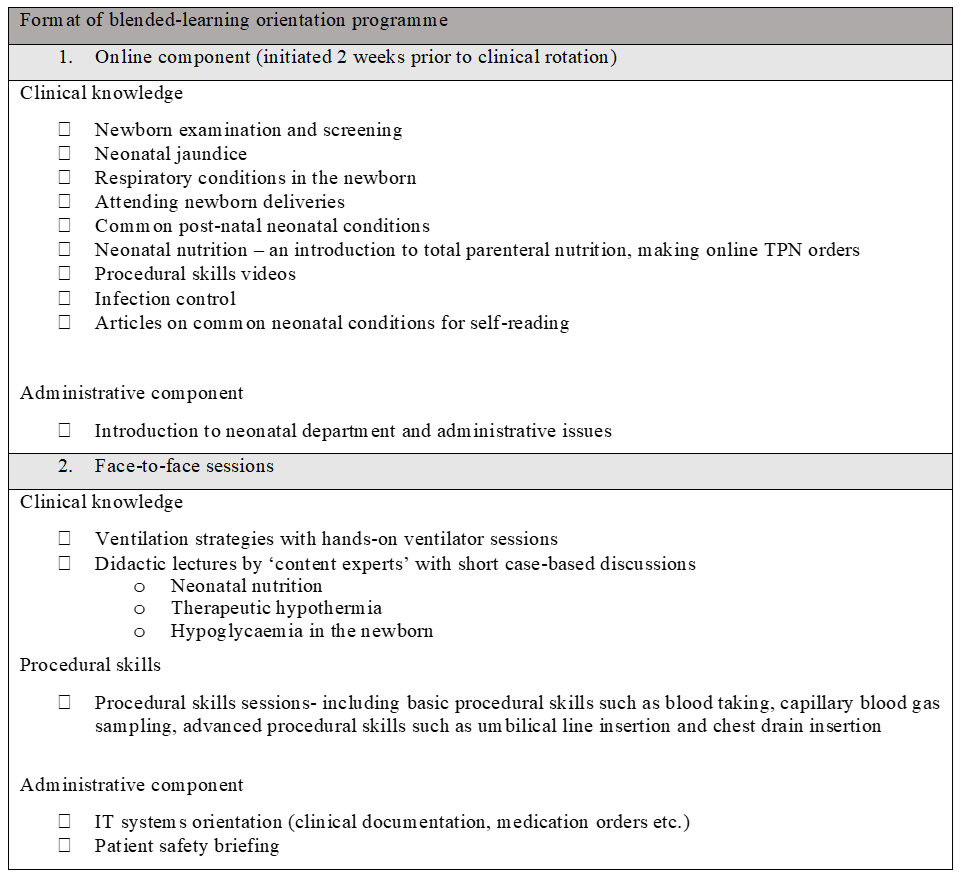

We identified a list of core topics and procedural skills which formed the programme curriculum (Figure 1).

The teaching format was changed from mainly didactic lectures to case-based scenarios in both online and face-to-face sessions, as this has been shown to better motivate students towards self-directed learning and develop problem-solving skills. Case-based scenarios would also facilitate greater peer discussion and interactivity amongst learners in the face-to-face sessions.

We worked with IT specialists to convert specific topics to six online learning modules, and included interactive components such as clickable elements and narration to better engage learners (Choules, 2007). Each module was designed to be completed within 30 minutes.

For neonatal procedural skills, learners were expected to watch online demonstration videos created by the department prior to attending hands-on practical sessions.

Figure 1. Outline of blended-learning orientation programme

5) Step 5: Implementation

The blended learning programme was implemented with junior doctors across two batches from July 2022 to January 2023. Majority were from post-graduate year three to five, with approximately half having no prior working experience in neonatology. All participated in the face-to-face sessions and completed the online modules.

We used our institution’s online learning management system to deliver the e-learning modules, and department faculty members conducted the face-to-face sessions. Designated ‘protected teaching time’ was implemented to facilitate attendance during office hours.

6) Step 6: Evaluation and feedback

We designed a pre-and-post-programme assessment consisting of 24 multiple-choice questions covering the following aspects – (1) clinical scenarios with interpretation of laboratory and radiological results, (2) factual knowledge and (3) questions on procedural skills.

The junior doctors also completed an online survey which assessed the learners’ perceptions on blended learning. Consent for the survey data to be used for research was implied in their participation.

III. RESULTS

The junior doctors had a positive experience with blended learning. All participants agreed that the learning content was relevant and appropriate for their level of experience. Almost all participants felt that there was ease of access to the online learning modules, with minimal technical issues. Learners also found specific online modules such as respiratory conditions ‘useful’, but enjoyed the face-to-face nature of sessions such as ventilatory strategies, as it gave them the opportunity to clarify doubts with their facilitator. Overall, the duration of the face-to-face orientation sessions was halved, and there was a significant improvement in the mean MCQ score.

IV. DISCUSSION

A blended learning programme designed for novice learners in Neonatology is effective in preparing junior doctors for clinical work.

Learning theories suggest that adult learners are motivated to invest time in learning if they understand its relevance (Taylor & Hamdy, 2013). The shift towards case-based learning bridges theory and practice, and motivates participation in clinical decision-making. This is an effective form of learning as demonstrated by an improvement in the mean post-test MCQ score of the participants. The experience was also deemed a positive one in qualitative feedback. In addition, the accessibility of online modules provided learners with autonomy to control their pace of learning. However, it is important to strike the right balance between online and classroom teaching, as learners still value the interactivity offered by face-to-face teaching.

We should work to create a supportive infrastructure to support blended learning methods by training more clinician-educators in online learning approaches and designing ‘reusable’ learning resources, which can be modified and integrated into other medical courses in future (Singh et al., 2021).

The limitations of our study include reliance on multiple choice tests to assess knowledge, and a lack of formal evaluation of procedural skills. Competency-based evaluations, as well as practical skills evaluations can be implemented in future runs to evaluate the efficacy of the courses.

V. CONCLUSION

Technology enhanced learning is fast becoming an integral part of medical education. Through this study, we demonstrate that blended learning programmes can be successfully integrated into the training of junior doctors in a subspecialty setting.

Notes on Contributors

WT led the design and conceptualisation of this work, implemented the education programme, and drafted the manuscript. BQ provided feedback and guidance on creating the content of the education programme. CC provided guidance on the evaluation of teaching programme. CC, AT and BQ provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors approve the publishing of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors received a Singhealth Duke-NUS Academic Medicine Education Institute Education Grant 2021 (funding number EING2205) to support the development of curriculum content for our programme.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Choules, A. P. (2007). The use of elearning in medical education: A review of the current situation. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 83(978), 212-216. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.05 4189

Liu, Q., Peng, W., Zhang, F., Hu, R., Li, Y., & Yan, W. (2016). The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), e2.

Singh, J., Steele, K., & Singh, L. (2021). Combining the best of online and face-to-face learning: Hybrid and blended learning approach for COVID-19, post vaccine, & post-pandemic world. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(2), 140-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472395211047865

Taylor, D. C., & Hamdy, H. (2013). Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Medical Teacher, 35(11), e1561-e1572. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2013.828153

Thomas, P. A., Kern, D. E., Hughes, M. T., Tackett, S. A., & Chen, B. Y. (Eds.). (2022). Curriculum development for medical education: A six-step approach. Johns Hopkins University Press.

*Tong Wing Yee

100 Bukit Timah Road

Singapore 229899

Email: tong.wing.yee@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 19 September 2023

Accepted: 9 January 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 61-63

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/CS3137

Yoshikazu Asada1, Chikusa Muraoka2, Katsuhisa Waseda3 & Chikako Kawahara4

1Medical Education Center, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 2School of Health Sciences, Fujita Health University, Japan; 3Medical Education Center, Aichi Medical University, Japan; 4Department of Medical Education, Showa University, Japan

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 epidemic has prompted the spread of ICT-based education, with many university classes being conducted remotely. Some education systems use asynchronous tools such as learning management systems (LMSs); others use synchronous tools such as web conference systems. This trend has affected not only lectures but also exercises among students and clinical practice. Game-based education is no exception, and classes that require direct face-to-face interaction have become difficult to implement. Escape rooms (ERs) are one example of game-based education.

ERs are defined as “live-action team-based games where players discover clues, solve puzzles, and accomplish tasks in one or more rooms in order to accomplish a specific goal (usually escaping from the room) in a limited amount of time” (Nicholson, 2015). Originally intended for entertainment purposes, ERs now also serve educational purposes (Davis et al., 2022). As an educational tool, ERs are mainly used for teaching specific content knowledge and content-related skills, general skills, and affective goals (Veldkamp et al., 2020). In addition, since ERs are categorised as game-based education, they are also useful for motivating students.

ERs may be conducted either face-to-face or online. Online-based ERs, known as “Digital Educational Escape Rooms” (DEERs), have become common since the COVID-19 pandemic (Makri et al., 2021). DEERs combine the (1) possibility of digital and analog hybrid style, (2) the potential to provide immediate feedback, and (3) the suitability for some learning objectives such as social skills.

This study is intended to design and develop DEERs based on Moodle and Zoom for teaching basic professionalism, with a focus on peer collaboration for medical students.

II. METHODS

The authors made an online-based DEER with Moodle LMS and used it for teaching team communication and reviewing basic CPR knowledge for second-year undergraduate medical students. In this case, students solve asynchronous DEER challenges in Moodle through synchronous discussion in Zoom breakout rooms.

The learning objectives were to “learn collaboratively with peers” and to “understand concepts related to interpersonal relationships and interpersonal behaviour.” Before the class, students submitted a short report on the important elements that are required for team medicine, which they had learned as first-year students. The class was 100 minutes in length. The first 10 minutes were used for orientation. The next 60 minutes were used for DEERs. Within 60 minutes, a hint for solving DEERs was provided via Google Documents; authors added the hint as time went on. After the game, 30 minutes were used for reflection, including the explanation of the DEER answers and the basic lectures. Despite the existence of two aforementioned learning objectives, the time limits made it particularly hard to assess students’ achievement. Therefore, after the class, a report was assigned on the topic “points to keep in mind when sharing information and communicating with your team online through the game experience.”

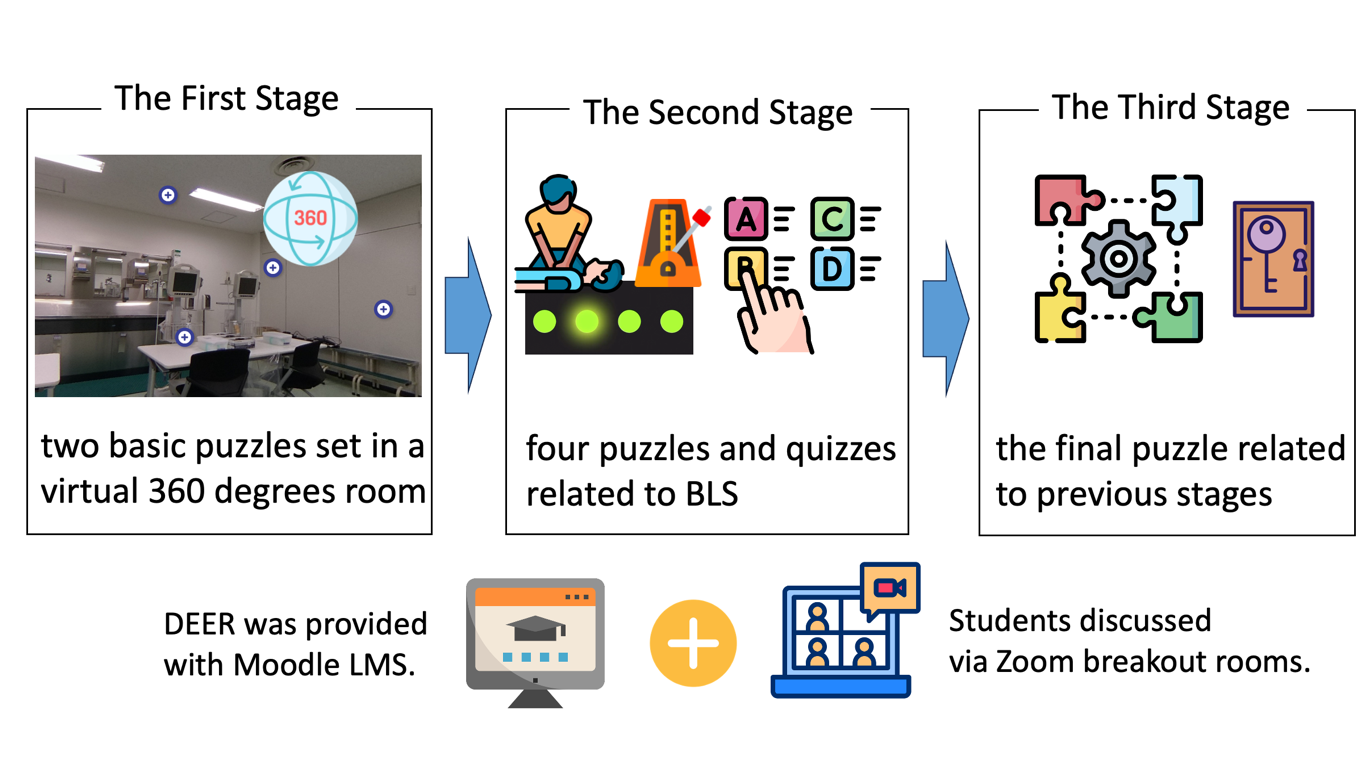

There were three stages to the DEER. A total game design is shown in Figure 1. The first stage consisted of a 360o virtual room. Students had to explore the virtual room and solve two riddles. In this stage, some hints were hidden on the ceiling or the floor. Students had to find them by looking around the room. After solving the riddles, students inputted the answer to Moodle. If the answer was wrong, they had to wait one minute before inputting another answer. The second stage began after the two riddles. This stage had four puzzles related to CPR, such as concerning the placement of AED or metronome tempo of chest compression. Since the students learned about CPR when they were first-year students, these four puzzles were reviewed their understanding. The third stage was after the four CPR puzzles. In the third stage, students had to gather all the clues to clear the game.

Figure 1. A total game design

Program evaluation was based on students’ achievement results from the Moodle log and their comments from the questionnaires.

III. RESULTS

There were 29 groups, and each one had three to four students. While five groups were able to solve the riddle completely, one group could not even reach stage two. Moodle log data and questionnaires suggested that the difficulty of the riddles was appropriate, since only 8% of participants answered that the first stage was difficult, and other groups used about 15 minutes for the first stage from the logs.

In some groups, students turned off their cameras and solved the riddles individually. In this case, they shared almost nothing but the answers, and very little about the process for solving puzzles and riddles. In other groups, students turned on their cameras and shared the screen. In contrast to the previous groups, they solved the puzzles and riddles through live discussions.

IV. DISCUSSION

Some groups could not complete the DEERs, and one group could not reach stage two. In the group that could not finish stage one, students did not share the process of solving riddles. Moreover, they turned off their cameras, which made it difficult to define how they were approaching the tasks. The communication style of students potentially affects their achievement level. It is also connected to their learning objectives.

Despite the difficulty of teaching skills and attitude only with asynchronous distance learning, some scope exists for interactive content, for example, by having the students choose the correct tempo for chest compressions by sound with live discussion and feedback from others. Of course, it will be more effective to use face-to-face simulations to check psychomotor skills.

In this case, gathering students’ learning logs was easy since DEER was provided with Moodle. In addition, observing how students discuss in online was possible, since Zoom can track the activity status in breakout rooms. Although the design, development, and implementation of the DEERs will be complicated, the hybrid-style DEER, such as using LMS with synchronous classes, might make DEERs more attractive. Furthermore, it makes collection of a variety of data, such as the timestamp of answer, pattern of the failure, and manner of online communication, possible. These data would be useful to assess students and provide feedback to them.

V. CONCLUSION

DEERs are potentially useful for engaging student communication and discussion even in the online synchronous class. In the future, it will be possible to provide an integrated learning experience with a more appropriate difficulty level by accumulating Moodle log data and student recognition data.

Notes on Contributors

YA and CM designed and developed DEER. They also analysed the results.

KW and CK managed the class and facilitated the breakout room.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of all participants.

Funding

This work was supported by FOST (Foundation for the Fusion of Science and Technology) 2019 and 2022 Research Grants.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Davis, K., Lo, H. Y., Lichliter, R., Wallin, K., Elegores, G., Jacobson, S., & Doughty, C. (2022). Twelve tips for creating an escape room activity for medical education. Medical Teacher, 44(4), 366–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1909715

Makri, A., Vlachopoulos, D., & Martina, R. A. (2021). Digital escape rooms as innovative pedagogical tools in education: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(8), Article 4587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084587

Nicholson, S. (2015, May 24). Peeking behind the locked door: A survey of escape room facilities. http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/erfacwhite.pdf

Veldkamp, A., van de Grint, L., Knippels, M. P. J., & van Joolingen, W. R. (2020). Escape education: A systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educational Research Review, 31, Article 100364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100364

*Yoshikazu Asada

Medical Education Center

Jichi Medical University

3311-1, Yakushiji, Shimotsuke,

Tochigi, Japan

+81-285-58-7067

Email: yasada@jichi.ac.jp

Submitted: 13 September 2023

Accepted: 4 March 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 64-66

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/CS3138

Jayabharathi Krishnan, Sara Kashkouli Rahmanzadeh & S. Thameem Dheen

Department of Anatomy, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

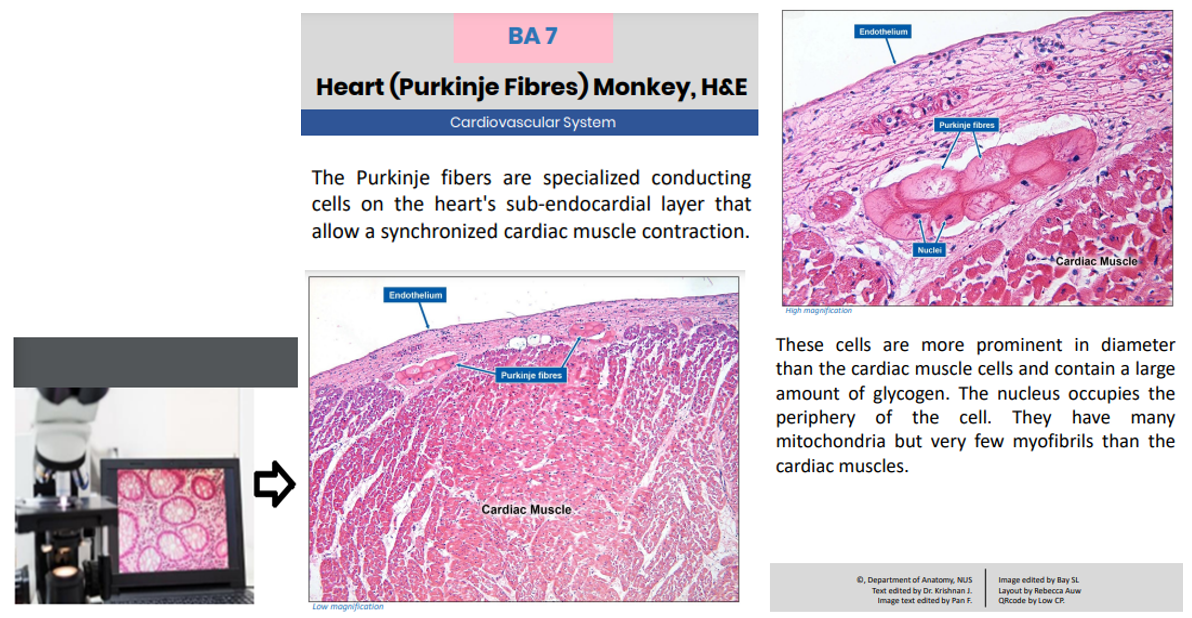

In preclinical years, histology, which is the study of the microscopic structures of tissue and organs, aids students in understanding the normal morphology of cell and tissue organisation in organs and differentiating their pathological changes (Hussein & Raad, 2015). The study of histology is important as it provides the fundamental basis of anatomical knowledge. Students have adapted to a new learning environment, particularly after the COVID-19 outbreak, by utilising autonomous learning strategies, including online and digital learning, as histology requires visual interpretation that is developed by continuous practice (Yohannan et al., 2019). Given this, we have created a virtual histology platform using our existing tool: the National University of Singapore – Human Anatomy Learning resOurce (NUS-HALO). NUS- HALO is an online platform with digital images and videos and has emerged as a novel tool in transforming anatomy teaching and learning. By integrating cutting-edge, high-definition histology images and relevant learning materials, the histology component of NUS-HALO offers a platform that aids students to excel in histology (Darici et al., 2021).

The NUS-HALO platform aids student learning of histology. Histology resources are organised systematically, along with pertinent teaching resources and explanations, to help students better comprehend each histological slide. Furthermore, during their third year of medical school, when students are introduced to pathology, they must use their earlier understanding of normal histology to identify pathological changes.

II. METHODS

Our team included three technical and five academic staff members. The digitisation of histology sections, selected from our existing collection in the Department, was done using Aperio software, and the digital images were saved on a server to be accessed later for teaching. Overall, images from 160 histology slides comprising 13 organ systems were digitised, each taking about 90 minutes to digitise. These images were clustered with the previously saved images (200 images from seven organ systems) and selected for NUS-HALO’s histology arm. The histology slides were carefully chosen to obtain low- and high-magnification images. The images were labelled to give students a clear understanding of each organ system and its critical features.

III. DISCUSSION

NUS-HALO offers a platform that aids student learning of histology. Histology resources are organised systematically, along with pertinent teaching resources and explanations, to help students better comprehend each histological slide. Furthermore, during their third year of medical school, when students are introduced to pathology, they must use their earlier understanding of normal histology to identify pathological changes.

HALO’s histology resources can be seamlessly integrated with what students learn during their anatomy and physiology classes. The use of this tool allows for a holistic understanding where students are able to correlate the microscopic histological structures with macroscopic anatomical features and physiological functions. Informal feedback that has been obtained from both staff and students has been overwhelmingly positive, highlighting the ease of use and quality of the resources available on the platform. A notable outcome has been the informal feedback received by students, stating that the platform has aided their examination preparation. However, continued and more formal gathering of feedback is essential for the platform’s ongoing improvement.

Future enhancements of the platform include using more diverse slide samples, and more interactive elements such as self-evaluation guides to enhance student’s experience and the effectiveness of NUS-HALO. Self-evaluation guides that are currently being considered include identification exercises, where students name structures on slides, and interpretive questions that can test their understanding of how histological changes might relate to pathological conditions. These tools will reinforce learning and enable students to track their progress.

A. Pedagogical Framework of Digital Histology on NUS-HALO

The resources on the NUS-HALO webpage were organised as follows:

1) Categorisation of Histology Images:

Images were organised based on the organ system they belong to (e.g., respiratory, digestive). Each image was annotated with labels and identification markers highlighting fundamental structures and features.

2) Integration of Teaching Resources:

Short notes describing salient features of the sections were embedded alongside the corresponding histology images to provide students with further explanations.

3) Navigation and User Interface:

The resources were organised to facilitate easy navigation, with a search function, intuitive m menus, and clear headings.

Figure 1: Showing high-quality images captured and uploaded for student access (leftmost). Image showing information available to students when they select digitised slides.

IV. CONCLUSION

The advent of computer-aided digital media and images has significantly impacted medical education, including image-intensive histology. Digitising histology slides appears cost-effective as it reduces the need for microscope maintenance and preparation of glass slides when damaged and manpower costs. This tool serves as an additional learning resource that students can access in conjuction with their existing histology lectures or practical lessons.

In the future, digital histology can be enhanced by incorporating augmented and virtual reality and artificial intelligence to provide students with an enhanced, immersive, and interactive learning experience.

Note on Contributors

Dr. Jayabharathi Krishnan, Dr. Sara Kashkouli Rahmanzadeh, and Professor S. Thameem Dheen are content experts on the Histology aspect of NUS-HALO. All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical staff: Ms . Pan Feng, Ms. Bay SL, Ms. Rebecca Auw, and Mr. Low CP from the Department of Anatomy, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, for their technical support. The authors would sincerely like to thank the Department of Pathology for contributing to developing the digitalised images.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

Darici, D., Reissner, C., Brockhaus, J., & Missler, M. (2021). Implementation of a fully digital histology course in the anatomical teaching curriculum during covid-19 pandemic. Annals of Anatomy – Anatomischer Anzeiger, 236, Article 151718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2021.151718

Hussein, I. H., & Raad, M. (2015). Once upon a microscopic slide: The story of histology. Journal of Cytology & Histology, 6(6), Article 1000377. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7099.1000377

Yohannan, D. G., Oommen, A. M., Umesan, K. G., Raveendran, V. L., Sreedhar, L. S., Anish, T. S., Hortsch, M., & Krishnapillai, R. (2019). Overcoming barriers in a traditional medical education system by the stepwise, evidence-based introduction of a modern learning technology. Medical Science Educator, 29(3), 803–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-019-00759-5

*DR K JAYABHARATHI

Department of Anatomy

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

MD10, 4 Medical Drive

Singapore 117594

Email: antkj@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 11 December 2023

Accepted: 18 March 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 67-69

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/CS3189

Galvin Sim Siang Lin1, Wen Wu Tan2, Yook Shiang Ng1 & Kelvin I. Afrashtehfar3

1Department of Restorative Dentistry, Kulliyyah of Dentistry, International Islamic University Malaysia, Malaysia; 2Department of Dental Public Health, Faculty of Dentistry, Asian Institute of Medicine, Science and Technology (AIMST) University, Malaysia; 3Evidence-Based Practice Unit, Clinical Sciences Department, College of Dentistry, Ajman University, United Arab Emirates

I. INTRODUCTION

The landscape of health profession education, particularly dental education, is evolving to equip students with essential contemporary knowledge and skills for competent dental practice. Within this context, dental materials science plays a pivotal role in undergraduate dental programs, providing the foundation for understanding the materials used in clinical dentistry. However, traditional teaching approaches relies on didactic lectures, often rendering this multidisciplinary subject seem dry and challenging (Soni et al., 2021). Students also face difficulties in grasping the practical applications of materials science in clinical dentistry within the confines of passive didactic lectures.

Recognising these limitations, there is a growing need for innovative pedagogical strategies shifting from teacher-centred to student-centred approaches, fostering active learning. Problem-based learning (PBL), case-based learning (CBL), and team-based learning (TBL) emerge as alternatives. While PBL involves open-inquiry scenarios, it can be time-consuming. CBL, a guided inquiry method, recreates clinical settings, with the teacher as a facilitator. Meanwhile, TBL, introduced in the 1970s, is a teacher-centred approach fostering active learning through student engagement (Michaelsen et al., 2004). Despite their efficacy, their application in dental materials science courses remains underrepresented. This gap represents a significant deficiency in dental education, especially given the critical role of dental professionals in selecting and justifying the use of appropriate materials in clinical cases. This study addresses this gap by comparing the academic performance of undergraduate dental students in dental materials science courses, utilising a hybrid TBL-CBL approach against traditional didactic lectures.

II. METHODS

The study received approval from the local institutional ethics committee (approval code AUHEC/FOD/ 2022/28). The preclinical course comprised four modules taught over two semesters (One academic year consists of 2 semesters). A quasi-experimental design involved 74 second-year dental students, comparing continuous assessment scores between didactic lectures (pre-test) and hybrid TBL-CBL (post-test) introduced in the third module. Excluding the first module and final assessment in the fourth module, only scores from modules 2 and 3 were compared. Content validation involved group discussion and consensus among faculty members ensuring question difficulty alignment with learning outcomes. Hybrid TBL-CBL was conducted in seminar rooms with students randomly assigned to groups. Pre-reading materials, including PowerPoint slides from prior lectures were given. The process encompassed a 15-minute introduction, Readiness Assurance Process (iRAT and tRAT), application activities, and a debriefing session. Data collection involved an unbiased faculty member anonymously obtaining consent for module 2 and module 3 assessment scores, evaluated against grading criteria. Descriptive statistics analysed demographic background, while the Wilcoxon test assessed academic performance using IBM SPSS software with a significance level set at 0.05.

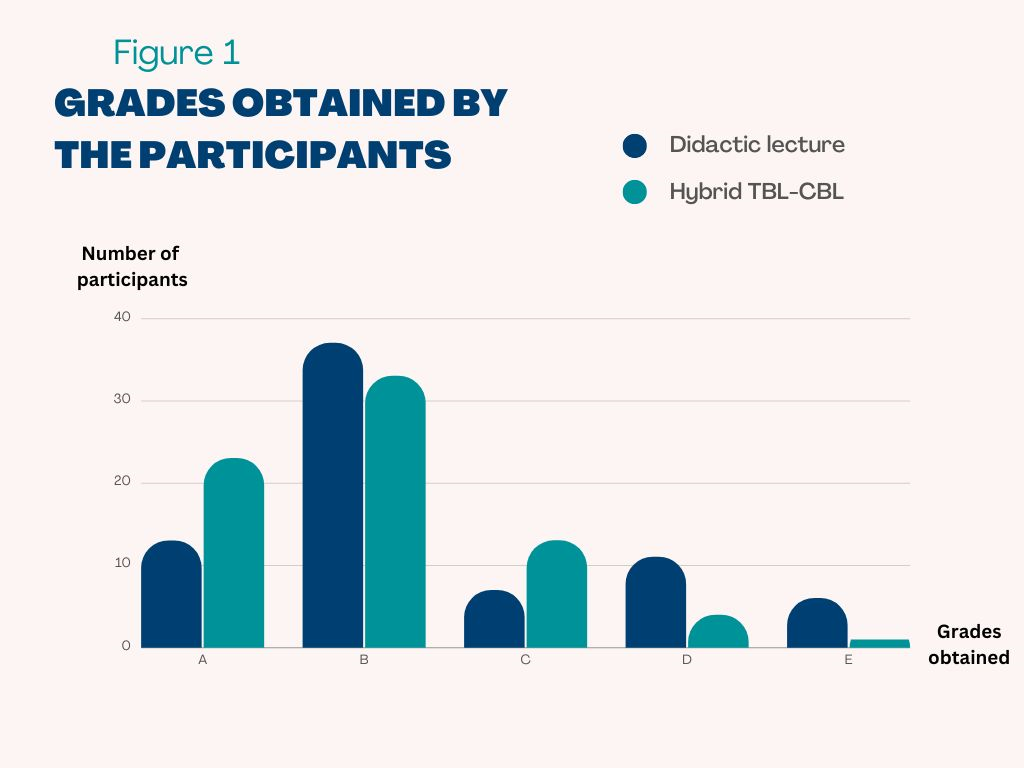

III. RESULTS

54 females (73%) and 20 males (27%) consented to assessment score collection. Mean scores increased significantly (p=0.001) from 61.89±15.67 to 67.35±12.57 after hybrid TBL-CBL, with both female and male scores rising. However, male academic improvement was not statistically significant (p=0.130). Following hybrid TBL-CBL, 13 initially failing students in traditional lectures passed (p=0.020). Assessment grades depicted a notable increase in ‘A’ grades (8.1% to 20.3%) and a decrease in ‘D’ and ‘F’ grades (23.0% to 6.7%). These findings underscore the positive impact of hybrid TBL-CBL on academic outcomes and the successful remediation of initially struggling students.

Figure 1. Assessment grades of students before and after the implementation of hybrid TBL-CBL

IV. DISCUSSION

In contrast to traditional didactic lectures, the hybrid TBL-CBL approach requires active student participation in group discussions, case analysis, and feedback sessions. After implementing hybrid TBL-CBL in module 3, significant improvement in students’ comprehension of dental materials science was observed through higher assessment scores. This finding is consistent with other research suggesting that both TBL and CBL improve students’ knowledge retention and learning experiences through active group learning, leading to better academic performance (Ulfa et al., 2021). Students are expected to participate more actively in group discussions and learn better from the prior knowledge they gained through pre-reading materials, which helps them perform well in collaborative learning. Both TBL and CBL involve dividing students into small groups, which provides the opportunity to be more interactive and engage in discussion among each other. Unlike the passive nature of large lecture-based teaching, which often leads to “lecture ennui” among students due to one-way communication.

The current study revealed that both male and female students showed improvement in their mean assessment scores following the implementation of hybrid TBL-CBL approach. However, the improvement was not significant among male students. It is plausible that female students perceived the hybrid TBL-CBL sessions more positively, leading to increased engagement and learning (Das et al., 2019). Conversely, male students frequently attend TBL sessions less prepared and feel that their assessment scores do not accurately represent their level of knowledge. Nevertheless, female students tend to learn in a collaborative, dependent, and participatory manner, whereas male students lean towards independent and competitive ways (Mahamod et al., 2010). Thus, the authors postulated that female students would benefit more from peer learning in hybrid TBL-CBL sessions than male students.

One limitation of the present study is that a comparison of assessment scores among higher-performing and low-performing students were not performed. Although there was no statistically significant increase in the academic performance of male students, it is important to note that this may be because there were fewer male students than female students, which may hinder our ability to detect significant differences. Since the present study utilised a one-group pre- and post-test research design, it is likely that students’ interactions with teachers and learning styles may have an impact on their assessment scores. Moreover, the effectiveness of the present hybrid TBL-CBL would be further supported by randomised control research including a larger sample size in different institutions across the nation.

V. CONCLUSION

The hybrid TBL-CBL enhanced academic performance over traditional lectures, particularly benefiting female students. While promising for dental materials science education, future studies are needed to assess its efficacy across healthcare fields and diverse health professional student populations.

Notes on Contributors

Galvin Sim Siang Lin designed the study, performed data collection, drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Wen Wu Tan performed data analysis, drafted and approved the final manuscript.

Yook Shiang Ng drafted, read and approved the final manuscript.

Kelvin I. Afrashtehfar gave critical feedback, read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The present study was approved by the Asian Institute of Medicine, Science and Technology (AIMST) University Human Ethics Committee (AUHEC) with ethical approval code AUHEC/FOD/2022/28.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, but raw data of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study.

Funding

The study received no funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

Das, S., Nandi, K., Baruah, P., Sarkar, S. K., Goswami, B., & Koner, B. C. (2019). Is learning outcome after team based learning influenced by gender and academic standing? Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 47(1), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21197

Mahamod, Z., Embi, M. A., Yunus, M. M., Lubis, M. A., & Chong, O. S. (2010). Comparative learning styles of Malay language among native and non-native students. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1042-1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.283

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (2004). Team-based Learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching. Stylus Pub. https://books.google.com.my/books?id=Hj OdPwAACAAJ

Soni, V., Kotsane, D. F., Moeno, S., & Molepo, J. (2021). Perceptions of students on a stand-alone dental materials course in a revised dental curriculum. European Journal of Dental Education, 25(1), 117-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12582

Ulfa, Y., Igarashi, Y., Takahata, K., Shishido, E., & Horiuchi, S. (2021). A comparison of team-based learning and lecture-based learning on clinical reasoning and classroom engagement: A cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 444. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02881-8

*Galvin Sim Siang Lin

Department of Restorative Dentistry,

Kulliyyah of Dentistry,

International Islamic University Malaysia,

25200, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia

Email: galvin@iium.edu.my

Submitted: 15 September 2023

Accepted: 17 November 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2),101-104

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/CS3140

Claudia Ng & Aishah Moore

Medical Education Unit, National School of Medicine (Sydney Campus), University of Notre Dame, Australia

I. INTRODUCTION

Despite agreement on the importance of Interprofessional education (IPE) for health professional education (HPE), best practice in developing and implementing IPE remains ambiguous. Students are important stakeholders and can be allies in IPE, but much of their potential in the development of curricula remains untapped.

In 2022, the University of Notre Dame, Australia (UNDA) partnered with the University of Tasmania (UTAS) to engage students in the co-design, implementation, and delivery of a program to support the development of interprofessional practice for preclinical medical students from the Doctor of Medicine (MD) and final year paramedicine students. The COVID-19 pandemic was a catalyst to re-imagine different ways of learning and teaching in this area. This paper aims to describe the process of and opportunities for involving students as partners (SaP).

II. METHODS

Expressions of interest were invited from student cohorts attending a previous iteration of the program. Four student partners across the professions were recruited.

A collaborative workshop provided an initial opportunity for student and staff partnership. The workshop intended to nurture relationships through dialogue and reflection. Student evaluations from previous programs were reviewed and themes were highlighted for discussion. Opportunities were provided for students and educators from both professions to express individual opinions and perspectives from their own experiences of the program.

The major themes that arose from the student experience were the importance of experiential learning through simulation and the importance of having dedicated time for clinical skills practice. The opportunity to engage in interprofessional education was a consistent theme. Educators and student partners discussed the meaning of “success” in an interprofessional program and whether certain pedagogical models and program design could enhance learner outcomes.

III. OUTCOMES

Engagement of students occurred in various ways (Figure 1) and resulted in co-developed learning outcomes for an updated Rural Trauma week (RTW), focusing on the assessment and management of the patient, understanding the differing roles of each profession, and the impact of communication and teamwork of interprofessional teams on patient outcomes.

Students co-designed and reviewed the sequence of program elements. The program commenced with building the learner’s knowledge base through online delivery of lectures and pre-reading materials.