Using a consensus approach to develop a medical professionalism framework for the Sri Lankan context

Submitted: 15 April 2020

Accepted: 5 June 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 49-59

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/OA2248

Amaya Tharindi Ellawala1, Madawa Chandratilake2 & Nilanthi de Silva2

1Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka; 2Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Introduction: Professionalism is a context-specific entity, and should be defined in relation to a country’s socio-cultural backdrop. This study aimed to develop a framework of medical professionalism relevant to the Sri Lankan context.

Methods: An online Delphi study was conducted with local stakeholders of healthcare, to achieve consensus on the essential attributes of professionalism for a doctor in Sri Lanka. These were built into a framework of professionalism using qualitative and quantitative methods.

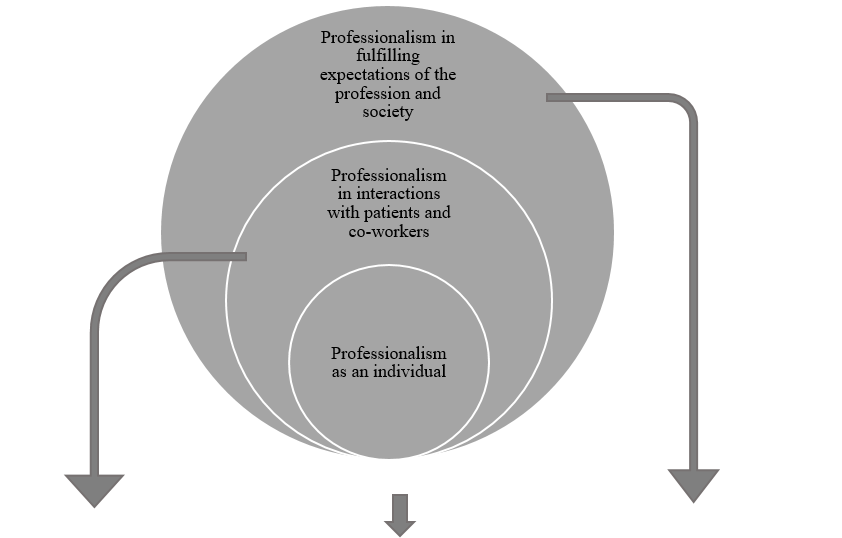

Results: Forty-six attributes of professionalism were identified as essential, based on Content Validity Index supplemented by Kappa ratings. ‘Possessing adequate knowledge and skills’, ‘displaying a sense of responsibility’ and ‘being compassionate and caring’ emerged as the highest rated items. The proposed framework has three domains: professionalism as an individual, professionalism in interactions with patients and co-workers and professionalism in fulfilling expectations of the profession and society, and displays certain characteristics unique to the local context.

Conclusion: This study enabled the development of a culturally relevant, conceptual framework of professionalism as grounded in the views of multiple stakeholders of healthcare in Sri Lanka, and prioritisation of the most essential attributes.

Keywords: Professionalism, Culture, Consensus

Practice Highlights

- Medical professionalism is recognised as a culturally dependent entity.

- This has led to the emergence of definitions unique to socio-cultural settings.

- List-based definitions provide operationalisable means of portraying its meaning.

- A Delphi study was conducted to achieve consensus on locally relevant professionalism attributes.

- Using quantitative and qualitative methods, a conceptual framework of professionalism was developed.

I. INTRODUCTION

There is no single definition of medical professionalism that encompasses its many subtle nuances (Birden et al., 2014). The realisation that professionalism is a dynamic, multi-dimensional entity (Van de Camp, Vernooij-Dassen, Grol, & Bottema, 2004), significantly dependent on context (Van Mook et al., 2009), and cultural backdrop (Chandratilake, Mcaleer, & Gibson, 2012), has led to the emergence of definitions specific to cultures and socio-economic backgrounds.

Many of the current definitions originate from Western societies. Certain Eastern cultures have embraced such definitions, though they are undeniably in conflict with local traditional views (Pan, Norris, Liang, Li, & Ho, 2013). In parallel however, countries such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Japan, China and Taiwan have explored how professionalism is conceptualised within their contexts (Al-Eraky, Chandratilake, Wajid, Donkers, & Van Merrienboer, 2014; Leung, Hsu, & Hui, 2012; Pan et al., 2013). Such studies have portrayed the interplay between cultural, socio-economic and religious factors in shaping perceptions on professionalism, further fuelling the notion that professionalism must be “interpreted in view of local traditions and ethos” (Al-Eraky et al., 2014, p. 14).

Culture is the embodiment of elements such as attitudes, beliefs and values that are shared among individuals of a community and is therefore, an entity that distinguishes one group of people from another (Hofstede, 2011). Various cultural theories provide insight into inter-cultural differences across the globe (Hofstede, n.d.; Schwartz, 1999). The Sri Lankan cultural context, while aligned with those of its closest geographical neighbours in South Asia in some ways, differs from them in other important aspects.

Certain attempts have been made to explore the meaning of professionalism in Sri Lanka. Chandratilake et al. (2012) provided a degree of insight while comparing cultural similarities and dissonances in conceptualising professionalism among doctors of several nations. Monrouxe, Chandratilake, Gosselin, Rees, and Ho (2017) built on this work with their analysis of professionalism as viewed by local medical students. The sole regulatory authority of the medical profession in the country, the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC, 2009) has delineated what it expects in terms of professionalism, by outlining the constituents of ‘good medical practice’, many of which converge with elements of professionalism described in the literature.

While the work mentioned here has shed some light on the topic, to our knowledge, there were no studies that focused solely on the local conceptualisation of professionalism, drawing on the views of diverse stakeholders of healthcare.

There exist two schools of thought on how professionalism can be defined: as a list of desirable attributes (Lesser et al., 2010), or as an over-arching, value-laden entity that transcends such lists (Irby & Hamstra, 2016; Wynia, Papadakis, Sullivan, & Hafferty, 2014). Unlike the latter, a list may not address the “foundational purpose of professionalism” (Wynia et al., 2014, p. 712); however, it will provide a tangible, operationalisable portrayal (Lesser et al., 2010). It is possibly for this reason that many studies have opted for list-based definitions, an approach that is supported in the East (Al-Eraky & Chandratilake, 2012; Al-Eraky et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2013).

The aim of this study was to develop a culturally appropriate conceptual framework of medical professionalism in Sri Lanka using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. We envisioned that identifying a list of desirable attributes would be appropriate, providing a definition that could readily be operationalised for teaching/learning, assessment and research purposes (Wilkinson, Wade, & Knock, 2009).

II. METHODS

A. The Approach

We followed a consensus approach, and opted for the Delphi technique as it was imperative to involve a large number of participants not limited by geographical location (Humphrey-Murto et al., 2017). The method offered the further advantage of providing participants with equal opportunity to express their opinions (De Villiers, De Villiers, & Kent, 2005), thereby negating the possible drawbacks of face-to-face interactions and resulting in a ‘process gain’ (Powell, 2003).

B. Participant Panel

The panel comprised nation-wide stakeholders of healthcare (Table 1), from both rural and urban regions who were presumably exposed to diverse forms of medical services and geographical variations in their distribution.

|

Stakeholder group |

Description |

Number |

|

Medical teachers |

Four Medical Faculties (nation-wide) |

69 (44%) |

|

Medical students |

Four Medical Faculties (nation-wide) – fourth and final years |

36 (23%) |

|

Hospital doctors |

Four Teaching Hospitals (nation-wide) |

14 (9%) |

|

Healthcare staff |

Selected secondary and tertiary hospitals |

5 (3%) |

|

General practitioners |

Selected GP practices around the country |

2 (1%) |

|

Medical administrators |

Selected secondary and tertiary hospitals |

5 (3%) |

|

Policy makers in healthcare |

Ministry of Health, professional associations and regulatory bodies |

2 (1%) |

|

General public |

Employees of selected private and state banks Non-academic staff of four Medical Faculties Teachers of selected private and state schools |

25 (16%) |

Table 1. Composition of the Delphi panel

1) Delphi Round I: The question posed in the first round was ‘What are the attributes of professionalism you would expect in a doctor working in the Sri Lankan context?’. No limitation was posed on the number of answers to this open-ended question. This was piloted among a group comprising local medical educationists, medical officers and members of public and edited based on their feedback. Invitations to participate were emailed and informed consent was obtained through an online link. Participants were then automatically granted access to the online questionnaire. An email reminder was sent to the initial mailing list after one week. The questionnaire was accessible for three weeks from the date of launch. Invitations were emailed to 920 individuals, of which 158 (17.2%) responded.

To analyse the data of Round I, we used conventional content analysis, which is employed when literature and theory on a phenomenon is limited, thereby allowing themes to emerge from and be grounded in the data itself (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Initially, individual responses – considered as meaning units – were listed out verbatim, removing exact duplicates. Meaning units varied from single word responses to longer phrases, and were therefore divided into short and long meaning units. The latter were shortened into condensed meaning units, while preserving the original meaning. Finally, condensed and short meaning units were coded. Similar phrases were assigned the same code. A final scrutiny of the codes allowed the removal of synonymous items and coupling of items with similar meaning. We followed this process iteratively till the items had been refined to the maximum extent possible.

With two additional experts, we reviewed the appropriateness of items. Four common misconceptions of professionalism (distractors) were added, in order to prevent inattentive responses to the large number of items included in the subsequent round (Meade & Craig, 2012). A search of literature also revealed a number of evidenced-based items that had not emerged in the data. Three of these were agreed to be relevant and important to the local context, and were therefore added to the list, to ensure that a comprehensive coverage of items was achieved.

2) Delphi Round II: The attributes of professionalism were compiled into another online survey and emailed to all individuals initially invited to participate in the study, three weeks after completion of the first round; 118 of the initial sample (dropout rate = 25.3%) participated in Round II. Respondents were asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not important’ to ‘very important’, according to perceived importance in the local context. An email reminder was sent out after one week. The form was accessible for three weeks.

The aim of this second round was to select the attributes considered most essential. Content Validity Index (CVI) was chosen for this purpose, over less rigorous methods such as prioritisation by mean. The CVI is the proportion of respondents rating an item as essential (Polit & Beck, 2006). Responses ‘4’ and ‘5’of the Likert scale were determined as reflecting ‘essentialness’. The general acceptance is that in a study with a large number of raters (as in this case), a CVI > 0.78 will indicate that an item is essential (Lynn, 1986).

To avoid the possibility of agreement being due to chance, Kappa statistics – a measure of inter-rater agreement and the probability of chance responses – were computed. K-values can range from -1 to +1; -1 indicating perfect disagreement below chance, +1, perfect agreement above chance and 0, agreement equal to chance (Randolph, n.d.). A K-value ≥0.7 indicates acceptable inter-rater agreement.

As the final step, the prioritised list of attributes was emailed to participants requesting further comments; however, none were received. The Delphi study concluded at this stage.

In order to organise the attributes in a more meaningful manner, we attempted to identify the emerging domains of professionalism. Initially this was performed through an Exploratory Factor Analysis, a method which allows identification of underpinning, latent ‘factors’ that are inferred from the variables. Scholars have recommended however, that quantitative analysis of studies with a social science perspective be complemented with qualitative methods (Tavakol & Sandars, 2014). Therefore, a panel of experts individually sorted the attributes into themes using the constant comparison technique; data was sorted, systematically compared and the emergence of a theme was acknowledged when many similar items appeared across the data set (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). The results were compared with those of the Factor Analysis and by identifying common domains, a final framework of professionalism was formulated. As an additional measure, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) within each domain was computed to determine close clustering of items. The framework developed was vetted by a group of reviewers.

III. RESULTS

A. Profile of Participant Panel

The response rates of the different participant groups are depicted in Table 1. As demographic details were not re-obtained in Round II, the profile of this group could not be determined.

B. Results of Round I

A total of 288 items were initially documented, and condensed to 53 attributes following content analysis. The three evidence-based items and four distractors were added to make a final inventory of 60 items (Table 2).

C. Results of Round II

1) Essential Attributes of Professionalism: Forty-six items achieved a CVI > 0.78 and were therefore labelled as ‘essential’. The attributes are arranged in descending order of importance in Table 2. The Kappa value was 0.77, confirming that rating of items was not due to chance.

|

Attribute of professionalism |

CVI |

|

Possessing adequate medical knowledge and skills |

0.99 |

|

Displaying a sense of responsibility |

0.98 |

|

Being compassionate and caring |

0.97 |

|

Managing limited resources for optimal outcome |

0.97 |

|

Ensuring confidentiality and patient privacy |

0.97 |

|

Being punctual |

0.97 |

|

Maintaining standards in professional practice |

0.97 |

|

Displaying effective communication skills |

0.97 |

|

Displaying honesty and integrity |

0.97 |

|

Displaying commitment to work |

0.97 |

|

Being empathetic towards patients |

0.96 |

|

Being able to work as a member of a team |

0.96 |

|

Being reliable |

0.96 |

|

Displaying professional behaviour and conduct |

0.96 |

|

Being accountable for one’s actions and decisions |

0.96 |

|

Being available |

0.95 |

|

Being responsive |

0.95 |

|

Being clear in documentation |

0.95 |

|

Being patient |

0.94 |

|

Displaying effective problem-solving skills |

0.94 |

|

Understanding limitations in professional competence |

0.94 |

|

Being respectful and polite |

0.94 |

|

Ability to effectively manage time |

0.93 |

|

Being a committed teacher/supervisor |

0.92 |

|

Being open to change |

0.92 |

|

Commitment to continuing professional development |

0.91 |

|

Having scientific thinking and approach |

0.91 |

|

Being accurate and meticulous |

0.91 |

|

Maintaining work-life balance |

0.91 |

|

Displaying self confidence |

0.91 |

|

Ability to provide and receive constructive criticism |

0.90 |

|

Non-judgmental attitude and ensuring equality |

0.90 |

|

Engaging in reflective practice |

0.90 |

|

Respecting patient autonomy |

0.90 |

|

Being accessible |

0.88 |

|

Avoiding substance and alcohol misuse* |

0.86 |

|

Working towards a common goal with the health system |

0.85 |

|

Providing leadership |

0.84 |

|

Being humble |

0.84 |

|

Advocating for patients |

0.83 |

|

Maintaining professional relationships |

0.83 |

|

Adhering to a professional dress code |

0.82 |

|

Avoiding conflicts of interest |

0.82 |

|

Displaying sensitivity to socio-cultural and religious issues related to patient care |

0.81 |

|

Being composed |

0.80 |

|

Stands for professional autonomy** |

0.79 |

|

Being amiable |

0.77 |

|

Displaying sensitivity to socio-cultural and religious issues in dealing with colleagues and students* |

0.76 |

|

Being assertive |

0.75 |

|

Being creative in work related matters |

0.74 |

|

Not money minded |

0.73 |

|

Willingness to work in rural areas |

0.72 |

|

Respecting professional hierarchy** |

0.69 |

|

Possessing knowledge in areas outside of medicine |

0.68 |

|

Being altruistic |

0.65 |

|

Adhering to socio-cultural norms* |

0.64 |

|

Fluency in multiple languages |

0.62 |

|

Abiding by religious beliefs |

0.32 |

|

Displaying self-importance** |

0.19 |

|

Using professional status for personal advantage** |

0.07 |

Note: *Evidence-based items sourced from the literature **Distractors

Table 2. Attributes of professionalism arranged in order of perceived importance

The highest rated attributes were, ‘possessing adequate medical knowledge and skills’, followed by ‘displaying a sense of responsibility’ and ‘being compassionate and caring’. Five items were mentioned collectively across the main stakeholder groups:

- Being empathetic towards patients

- Possessing adequate knowledge and skills

- Displaying effective communication skills

- Displaying honesty and integrity

- Being respectful and polite

2) Development of a Professionalism Framework: The main themes of professionalism identified by the expert panel and through exploratory factor analysis are summarised in Table 3.

|

Panelist 1 |

Panelist 2 |

Panelist 3 |

Factor Analysis |

|

Professionalism in interactions with patients (1) |

Interpersonal (1,2) |

Competency – Competency in managing patients and clinical reasoning (3) |

Qualities required to effectively work within the healthcare team (2) |

|

Professionalism in interactions in the workplace (2) |

Intrapersonal (4)

|

Accountability – Taking responsibility for work performed as a doctor in the clinical context and in interactions with co-workers (2) |

Clinical competency, excellence and continuous development (3)

|

|

Professionalism in fulfilling expectations of the profession and society (3) |

Societal/public (3)

|

Attitude – Thought process, internal qualities of the doctor (4) |

Equal and fair treatment of patients (1)

|

|

|

|

Behaviour – External actions of the doctor (1) |

Humane qualities in dealing with patients (1) |

Table 3. Themes of professionalism identified quantitatively and qualitatively*

Based on the convergence of these domains, a framework was developed, which portrayed professionalism as encompassing three main elements: individual traits, inter-personal interactions and responsibilities to the profession and community (Figure 1). Cronbach Alpha values for the three domains were 0.882, 0.918 and 0.755, thereby confirming the relevance of the constituents to each overarching element.

|

Professionalism in interactions with patients and co-workers |

Professionalism as an individual |

Professionalism in fulfilling expectations of the profession and society |

|

Ensuring confidentiality and patient privacy |

Displaying a sense of responsibility |

Managing limited resources for optimal outcome |

|

Displaying effective communication skills |

Being punctual |

Maintaining standards in professional practice |

|

Being empathetic towards patients |

Displaying honesty and integrity |

Displaying professional behaviour and conduct |

|

Being able to work as a member of a team |

Displaying commitment to work |

Working towards a common goal with the health system |

|

Being available |

Being reliable |

Adhering to a professional dress code |

|

Being responsive |

Being accountable for one’s actions and decisions |

Avoiding conflicts of interest |

|

Being respectful and polite |

Being clear in documentation |

Stands for professional autonomy |

|

Being a committed teacher/supervisor |

Displaying effective problem-solving skills |

Possessing adequate medical knowledge and skills |

|

Respecting patient autonomy |

Understanding limitations in professional competence |

Maintaining work-life balance |

|

Being accessible |

Ability to effectively manage time |

Avoiding substance and alcohol misuse |

|

Providing leadership |

Being open to change |

|

|

Advocating for patients |

Commitment to continuing professional development |

|

|

Maintaining professional relationships |

Having scientific thinking and approach |

|

|

Displaying sensitivity to socio-cultural and religious issues related to patient care |

Being accurate and meticulous |

|

|

Being compassionate and caring |

Displaying self confidence |

|

|

Being patient |

Non-judgemental attitude and ensuring equality |

|

|

Ability to provide and receive constructive criticism |

Engaging in reflective practice |

|

|

Being humble |

|

|

|

|

Being composed |

|

Figure 1. A framework of medical professionalism for Sri Lanka

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Framework of Professionalism Attributes

The framework depicts a progressively widening circle, with desirable individual traits at its core, expanding into interactions within the workplace and finally, responsibilities as a professional in wider society. It thus depicts the fundamental areas that must be addressed in aspiring towards professionalism. The three domains are largely congruent with the broad areas of professionalism described by Van de Camp et al. (2004) and Hodges et al. (2011). Though portrayed as distinct entities however, we emphasise that the domains should not be interpreted as evolving in sequential stages; professional development should ideally occur in these areas simultaneously.

Frameworks developed in other Eastern cultures have highlighted significant tenets of local traditions and ethos that have shaped perceptions on professionalism. Confucian values in Taiwan (Ho, Yu, Hirsh, Huang, & Yang, 2011), principles of Bushido in Japan (Nishigori, Harrison, Busari, & Dornan, 2014), and Islamic teachings within Egypt (Al-Eraky et al., 2014), have been shown to be deeply entrenched within such understandings.

Sri Lanka possesses a rich and diverse cultural heritage. British ideologies in particular appear to influence local medical education (Uragoda, 1987), and the conceptualisation of professionalism (Babapulle, 1992; Monrouxe et al., 2017), resulting in a strong emphasis on ethical behaviour. Sri Lanka is widely acknowledged to have a ‘religious’ background. Theravada Buddhism, the religion followed by the majority of Sri Lankans, as well as less widespread religions such as Christianity, Hinduism and Islam, exert a significant influence on local culture (Gildenhuys, 2004). Virtues collectively upheld by these doctrines, such as generosity, impartiality, honesty and peace are thought to be central to the development of professionalism (Keown, 2002). Of these, honesty, impartiality (equality) and peace (composure) were echoed within the theme ‘professionalism as an individual’, as were responsibility, reliability and accountability. These characteristics, built on a foundation of integrity, are fundamental tenets of Sri Lanka’s socio-cultural framework. Thus, we reasoned that ‘professionalism as an individual’ was ideally depicted as central to the local concept of professionalism, highlighting the importance of building a solid foundation of fundamental characteristics.

We also drew on elements of the ‘cultural dimension’ (Hofstede, n.d.) and ‘cultural value’ (Schwartz, 1999) theories in developing the framework. Accordingly, the collectivist nature of local culture provides the basis for qualities that enable harmonious interactions with others, as depicted in the second domain. The hierarchical disposition of local society dictates that the doctor is duty-bound to ensure that responsibilities to the profession and community are met.

B. Essential Attributes of Professionalism

Among the essential items, broad areas encompassing competence, humanism, interpersonal skills and ethics were prioritised. Qualities most consistently mentioned in literature – accountability, integrity and respect – received high ratings (Van de Camp et al., 2004). Reflective practice, understanding limitations in practice, accepting constructive criticism and continuous professional development – ‘cornerstones’ of the medical profession – were also labelled as significant (Chandratilake et al., 2012; Wynia et al., 2014), in contrast to other Eastern settings (Adkoli, Al-Umran, Al-Sheikh, Deepak, & Al-Rubaish, 2011). The striking omission was altruism, which was intriguingly rated as non-essential. Altruism has been named as one of the most consistently valued attributes of professionalism worldwide (Van de Camp et al., 2004), and would assumedly be espoused in the local collectivist culture. Our findings suggest that even qualities accepted as key tenets of professionalism may not be equally valued cross-culturally. However, it has been claimed that altruism is traditionally a Western concept (Nishigori et al., 2014), and the acceptance of altruism as a composite of professionalism has been challenged in recent years, on the premise that selflessness may in fact be causing considerable harm (Harris, 2018; Nishigori, Suzuki, Matsui, Busari, & Dornan, 2019).

Participants rated ‘possessing adequate medical knowledge and skills’ as the most essential professionalism attribute. This coincides with findings from Canada (Brownell & Cote, 2001) and Asia (Leung et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2013), though conflicting with a school of thought that considers competence to be the foundation of professionalism, rather than an integral part of it (Stern, 2006). The primacy afforded to knowledge and skills most likely stems from the significance placed on education, which is upheld in Sri Lanka as the primary means of elevating one’s socio-economic status. The emphasis on responsibility and compassion – the second and third highest rated items – as well as morality and empathy, can be attributed to the deeply religious background of the country. It was unsurprising that respectfulness was prioritised, being a cardinal virtue embraced by Sri Lankans, as in other Eastern settings (Nishigori et al., 2014).

A comparison of professionalism attributes hailed as important in various contexts, with the highest rated qualities locally, revealed a convergence of several items (Table 4). This provides assurance that the local conceptualisation of professionalism reflects the ‘core’ principles of medical professionalism and shows considerable alignment with definitions provided by professional bodies around the world (General Medical Council [GMC], 2013; Medical Professionalism Project, 2002).

|

Sri Lanka |

USA (American Board of Internal Medicine, 2001) |

Western countries (Hilton & Slotnick, 2005) |

Canada (Steinert, Cruess, Cruess, Boudreau, & Fuks, 2007) |

Taiwan (Ho et al., 2011) |

China (Pan et al., 2013) |

|

Knowledge and skills |

|

|

Competence |

Clinical competence |

Clinical competence |

|

Responsibility |

Accountability |

Accountability Social responsibility |

Responsibility |

Accountability |

Accountability |

|

Compassion and caring |

|

|

|

Humanism |

Humanism |

|

Managing limited resources for optimal outcome |

|

|

|

|

Economic consideration |

|

Confidentiality and patient privacy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Punctuality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maintaining standards in professional practice |

Excellence |

|

|

Excellence |

Excellence |

|

Effective communication skills |

|

|

|

Communication |

Communication |

|

Honesty and integrity |

Integrity |

|

Honesty Integrity |

Integrity |

|

|

Commitment to work |

Duty |

|

Commitment |

|

|

|

|

Altruism |

|

Altruism |

Altruism |

Altruism

|

|

|

Respect |

Respect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self-awareness Reflection |

Self-regulation |

|

Self-management |

|

|

|

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

|

Teamwork |

|

|

|

Ethical practice |

Ethics |

Ethics |

Ethics |

|

|

|

|

Morality |

|

Morality |

|

|

Honour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Autonomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Health promotion |

Table 4. Comparison of main attributes of professionalism identified locally with those of Western and Eastern contexts

Interestingly, certain items globally recognised as insignificant in terms of professionalism (work-life balance, leadership, professional appearance and composure) (Chandratilake et al., 2012), were highlighted as essential locally. The local expectation that professionals maintain an appearance befitting of their social status and the high power-distance between doctor and patient (Hofstede, n.d.), could have contributed to the emphasis on appearance. Similarly, power distance could explain the significance placed on leadership, a crucial skill required to handle subordinates and patients at the ‘lower end’ of the power spectrum. A promising finding was the importance placed on ‘work-life balance’, complementing the lack of emphasis on altruism and coinciding with recommendations of multiple professional bodies that underscore the value of personal well-being (GMC, 2013). The significance assigned to composure can be attributed to Sri Lanka’s conservative nature (Schwartz, 1999), where cultural norms dictate that public displays of intense emotion be suppressed.

It was intriguing to note that of the four distractors—which were expected to be rated as non-essential— ‘stands for professional autonomy’ achieved a CVI just above the baseline. In Sri Lanka, political influence is known to permeate into the workplace; therefore, this attribute can be viewed in light of being able to perform one’s duties in the midst of such pressures. The paternalistic nature of the doctor-patient relationship common to many Eastern cultures, could also underpin the significance afforded to professional autonomy (Ho & Al-Eraky, 2016; Susilo, Marjadi, van Dalen, & Scherpbier, 2019). Incidentally, this item was not corroborated elsewhere in the literature and was therefore, unique to this study. Other items that were exclusive to the Sri Lankan context were clarity in documentation, patience, time management and maintaining professional relationships.

As a whole, it is evident that the local conceptualisation of professionalism—while including areas unique to the Sri Lankan context—greatly coincides with the perceptions representing professionalism shared by the global medical community.

C. Strengths and Limitations

The study has responded to calls for culture-specific discourse on professionalism (Monrouxe et al., 2017) and prioritisation of essential qualities in terms of professionalism (Jha, Bekker, Duffy, & Roberts, 2007). Many studies seeking to define professionalism have drawn on the views of particular stakeholder groups in isolation; few have attempted to collate the views of the many groups (Ho et al., 2011; Leung et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2013). Scholars have challenged the medical profession to determine who should define professionalism, with the belief that this onus should not be placed solely on doctors (Wear & Kuczewski, 2004). The assimilation of views of multiple stakeholder groups therefore, was a significant strength of this study.

Although the initial list of 920 individuals who were invited to participate in the study was representative of all groups of stakeholders, the majority of those who responded were medical teachers and students. Thus, the study results predominantly reflect the views of these two groups. This may have precluded identification of attributes considered essential by the less represented groups, especially the public.

Another limitation of the study was the exclusive use of English, which though widely used in Sri Lanka, is not the first language of the majority of the population. The decision was justified as all potential participant groups were posited to be adequately fluent in English to participate. However, we recognise that providing the option of Sinhalese and Tamil translations may have increased participation in certain groups (healthcare staff and the public).

Finally, we acknowledge that while this framework reflects the current perception regarding medical professionalism, this notion is far from static, and will undeniably evolve with time. We therefore propose that future research involve repeated discussions that may inform the evolution of the current framework with time, being mindful of achieving a fair balance of stakeholder representation to this end.

V. CONCLUSION

This study has enabled us, through a consensus seeking approach, to paint a picture of medical professionalism as grounded in the views of the multiple stakeholders of healthcare in Sri Lanka. The conceptual framework that represents these opinions, reflects how perceptions on professionalism are shaped by cultural, societal, religious, economic and other factors. Moreover, it has enabled identification of individual elements of professionalism that are expected of a doctor in the local context, and prioritisation of those most essential among them.

Notes on Contributors

Amaya Ellawala MBBS, PGDME, MD, is a Lecturer in Medical Education in the Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka. Amaya Ellawala reviewed the literature, developed the methodological framework for the study, performed data collection, analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Madawa Chandratilake MBBS, MMed, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education at the Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. Madawa Chandratilake contributed to the development of the methodological framework, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Nilanthi de Silva MBBS, MSc, MD, is a Senior Professor in the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. Nilanthi de Silva contributed to the development of the methodological framework, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya (P/15/01/2016).

Funding

This study was not funded.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Adkoli, B. V., Al-Umran, K. U., Al-Sheikh, M., Deepak, K. K., & Al-Rubaish, A. M. (2011). Medical students’ perception of professionalism: A qualitative study from Saudi Arabia. Medical Teacher, 33(10), 840–845.

Al-Eraky, M. M., & Chandratilake, M. (2012). How medical professionalism is conceptualised in Arabian context: A validation study. Medical Teacher, 34(S1), S90–S95.

Al-Eraky, M. M., Chandratilake, M., Wajid, G., Donkers, J., & Van Merrienboer, J. G. (2014). A Delphi study of medical professionalism in Arabian Countries: The Four-Gates Model. Medical Teacher, 36, S8–S16.

American Board of Internal Medicine. (2001). Project Professionalism. Philadelphia, USA: American Board of Internal Medicine.

Babapulle, C. J. (1992). Teaching of medical ethics in Sri Lanka. Medical Education, 26(3), 185–189.

Birden, H., Glass, N., Wilson, I., Harrison, M., Usherwood, T., & Nass, D. (2014). Defining professionalism in medical education: A systematic review. Medical Teacher, 36(1), 47–61.

Brownell, A. K. W., & Cote, L. (2001). Senior residents’ views on the meaning of professionalism and how they learn about it. Academic Medicine, 76(7), 734–737.

Chandratilake, M., Mcaleer, S., & Gibson, J. (2012). Cultural similarities and differences in medical professionalism: A multi-region study. Medical Education, 46(3), 257–266.

De Villiers, M. R., De Villiers, P. J. T., & Kent, A. P. (2005). The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Medical Teacher, 27(7), 639–643.

General Medical Council. (2013). Good Medical Practice. London, UK: GMC.

Gildenhuys, J. S. H. (2004). Ethics and Professionalism. Stellenbosch. South Africa: Sun Press.

Harris, J. (2018). Altruism: Should it be included as an attribute of medical professionalism? Health Professions Education, 4, 3–8.

Hilton, S. R., & Slotnick, H. B. (2005). Proto-professionalism: How professionalisation occurs across the continuum of medical education. Medical Education, 39, 58–65.

Ho, M., & Al-Eraky, M. (2016). Professionalism in context: Insights from the United Arab Emirates and beyond. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 8(2), 268–270.

Ho, M., Yu, K., Hirsh, D., Huang, T., & Yang, P. (2011). Does one size fit all? Building a framework for medical professionalism. Academic Medicine, 86(11), 1407–1414.

Hodges, B. D., Ginsburg, S., Cruess, R., Cruess, S., Delport, R., Hafferty, F., … Wade, W. (2011). Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Medical Teacher, 33(5), 354–363.

Hofstede, G. (n.d.). Cultural Dimensions. Retrieved from http://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Reading in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26.

Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Humphrey-Murto, S., Varpio, L., Wood, T. J., Gonsalves, C., Ufholz, L., Mascioli, K., … Foth, T. (2017). The use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research. Academic Medicine, 92(10), 1491–1498.

Irby, D. M., & Hamstra, S. J. (2016). Parting the clouds: Three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Academic Medicine, 91(12), 1606–1611.

Jha, V., Bekker, H. L., Duffy, S. R. G., & Roberts, T. E. (2007). A systematic review of studies assessing and facilitating attitudes towards professionalism in medicine. Medical Education, 41, 822–829.

Keown, D. (2002). Buddhism and medical ethics. Principles of Practice, 7, 39–70.

Lesser, C. S., Lucey, C. R., Egener, B., Braddock, C. H., Linas, S. L., & Levinson, W. (2010). A behavioral and systems view of professionalism. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(24), 2732–2737.

Leung, D. C., Hsu, E. K., & Hui, E. C. (2012). Perceptions of professional attributes in medicine: A qualitative study in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 18(4), 318–324.

Lynn, M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research, 35, 382–385.

Maykut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide. London, UK: Falmer Press.

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 437-455.

Medical Professionalism Project. (2002). Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physicians’ charter. The Lancet, 359, 520-522.

Monrouxe, L. V., Chandratilake, M., Gosselin, K., Rees, C. E., & Ho, M. J. (2017). Taiwanese and Sri Lankan students’ dimensions and discourses of professionalism. Medical Education, 51(7), 1-14.

Nishigori, H., Harrison, R., Busari, J., & Dornan, T. (2014). Bushido and medical professionalism in Japan. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 560–563.

Nishigori, H., Suzuki, T., Matsui, T., Busari, J., & Dornan, T. (2019). A two-edged sword: Narrative inquiry into Japanese doctors’ intrinsic motivation. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 4(3), 24-32.

Pan, H., Norris, J. L., Liang, Y., Li, J., & Ho, M. (2013). Building a professionalism framework for healthcare providers in China: A Nominal Group technique study. Medical Teacher, 35, e1531–e1536.

Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing and Health, 29, 489–497.

Powell, C. (2003). The Delphi Technique: Myths and realities – Methodological issues in nursing research. Journal of Advances in Nursing, 41(4), 376–382.

Randolph, J. (n.d.). Online Kappa Calculator. Retrieved from http://justusrandolph.net/kappa/

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48(1), 23–47.

Sri Lanka Medical Council. (2009). Guidelines on Ethical Conduct for Medical and Dental Practitioners Registered with the Sri Lanka Medical Council. Colombo, Sri Lanka: SLMC.

Steinert, Y., Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., & Fuks, A. (2007). Faculty development as an instrument of change: A case study on teaching professionalism. Academic Medicine, 82(11), 1057-1064.

Stern, A. (2006). Measuring Professionalism. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

Susilo, A. P., Marjadi, B., van Dalen, J., & Scherpbier, A. (2019). Patients’ decision-making in the informed consent process in a hierarchical and communal culture. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 4(3), 57-66.

Tavakol, M., & Sandars, J. (2014). Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part II. Medical Teacher, 36(10), 838–848.

Uragoda, C. (1987). A History of Medicine in Sri Lanka – From the Earliest Times to 1948. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka Medical Association.

Van de Camp, K., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., Grol, R. P. T. M., & Bottema, B. J. A. M. (2004). How to conceptualize professionalism: A qualitative study. Medical Teacher, 26(8), 696–702.

Van Mook, W. N. K. A., Van Luijk, S. J., O’Sullivan, H., Wass, V., Schuwirth, L. W., & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2009). General considerations regarding assessment of professional behaviour. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 20(4), e90–e95.

Wear, D., & Kuczewski, M. G. (2004). The professionalism movement: Can we pause? American Journal of Bioethics, 4(2), 1–10.

Wilkinson, T. J., Wade, W. B., & Knock, L. D. (2009). A blueprint to assess professionalism: Results of a systematic review. Academic Medicine, 84(5), 551–558.

Wynia, M. K., Papadakis, M. A., Sullivan, W. M., & Hafferty, F. W. (2014). More than a list of values and desired behaviors: A foundational understanding of medical professionalism. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 712–714.

*Amaya Ellawala

Department of Medical Education,

Faculty of Medical Sciences,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura,

Sri Lanka

Email address: amaya@sjp.ac.lk

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.