Translation of non-technical skills and attitudes to practice after undergraduate interprofessional simulation training

Submitted: 6 May 2024

Accepted: 12 September 2024

Published online: 7 January, TAPS 2025, 10(1), 48-52

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-1/SC3349

Craig S. Webster1,2, Antonia Verstappen1, Jennifer M. Weller1 & Marcus A. Henning1

1Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; 2Department of Anaesthesiology, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Introduction: We aimed to determine the extent to which non-technical skills and attitudes acquired during undergraduate interprofessional simulation in an Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) course translated into clinical work.

Methods: Following ACLS simulation training for final-year nursing and medical students, we conducted a 1-year follow-up survey, when graduates were in clinical practice. We used the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS – higher scores indicate better attitudes to interprofessional practice), and nine contextual questions with prompts for free-form comments. RIPLS scores underwent repeated-measures between-groups (nurses vs doctors) analysis at three timepoints (pre-course, post-course and 1-year).

Results: Forty-two surveys (58% response) were received, demonstrating translation of non-technical skills and attitudes to clinical practice, including insights into the skills and roles of others, the importance of communication, and improved perceptions of preparedness for clinical work. However, RIPLS scores for doctors decreased significantly upon beginning clinical work, while scores for nurses continued to increase, demonstrating a significant interaction effect (reduction of 5.7 points to 75.7 versus an increase of 1.3 points to 78.1 respectively – ANOVA, F(2,76)=5.827, p=0.004). Responses to contextual questions suggested that reductions in RIPLS scores for doctors were due to a realisation that dealing with emergency life support was only a small part of their practice. However, the prevailing work cultures of nurses and doctors in the workplace may also play a part.

Conclusion: We demonstrated the translation of non-technical skills and attitudes acquired in undergraduate simulation to the clinical workplace. However, results are tempered for junior doctors beginning practice.

Keywords: Work Culture, Translation, RIPLS, Simulation, Advanced Cardiac Life Support, Undergraduate Education, Skills and Attitudes, Patient Safety

I. INTRODUCTION

Preparing undergraduate healthcare students for their future roles in the clinical workplace is a central concern for modern healthcare educators and is of critical importance for the maintenance of adequate healthcare services throughout the world (Barnes et al., 2021). Modern healthcare is inherently multidisciplinary, yet much of the training received by healthcare practitioners remains siloed within professional groups, and this is particularly the case at the undergraduate level. The use of simulation in healthcare has become increasingly important in recent years as a way to offer safe and immersive training. Conducting simulation with interprofessional healthcare teams allows those who will work together to be trained together, and can have the double benefit of promoting the acquisition of technical and non-technical skills in participants, while also allowing insight into the skills, roles and knowledge of other team members from different professional groups (Jowsey et al., 2020).

We previously reported on the development and evaluation of an interprofessional Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) course for undergraduate nursing and medical students in their final year at the University of Auckland, aimed at increasing technical resuscitation and non-technical teamwork skills (Webster et al., 2018). The evaluation study, using a mixed-methods design and recruiting 69% of the entire year’s student cohort, demonstrated significant improvements in scores on the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) over the course of the training day, and important interprofessional and attitudinal insights into the skills and knowledge of other team members related to communication, teamwork, leadership, realism, and professional roles. Medical and nursing students both reported that such insights would not have occurred during uniprofessional simulation and felt that the course had better prepared them for work in the clinical context. At the end of the training day we invited participants to take part in a further follow-up survey timed to occur approximately one year later, at a time when participants would typically be working clinically.

Our aim in the present study was to determine the extent to which the non-technical skills and attitudes acquired during the undergraduate interprofessional ACLS simulation course translated into the clinical work of the former course participants.

II. METHODS

We conducted a 1-year follow-up survey comprising a further RIPLS questionnaire and nine additional contextual questions, with quantitative response scales and prompts for explanatory free-form comments (see Supplementary Table 1). The survey was mailed to participants who had elected to supply their contact information, along with a post-paid return envelope. All participants gave written informed consent to participate. One postal and one email reminder was also sent if a reply was not forthcoming.

The RIPLS is a validated questionnaire comprising 19 questions using 5-point Likert response scales (anchors, 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree), and yielding a possible total score from 19 to 95 points where higher scores indicate a greater willingness to engage in interprofessional practice (Parsell & Bligh, 1999). In the present analysis, RIPLS responses from each participant in the 1-year follow-up survey were paired with their own corresponding RIPLS scores at two previous time points and underwent repeated-measures between-groups (nurses vs doctors) analysis at three timepoints (pre-course, post-course and 1-year). Responses to quantitative ratings on contextual questions used identical 5-point Likert scales and were summarised along with exemplar quotations from the free-form comments (Supplementary Table 1).

III. RESULTS

Between August 2014 and November 2015, 42 survey responses were received, representing a 58% response rate from the 73 participants who elected to give contact information for the follow-up survey. Two nurses were not working clinically at the time of the survey, and their responses were excluded from analysis – resulting in a total of 14 nurses and 26 doctors being included in the present study. All doctors were working in hospitals at the time of the 1-year survey, as were 71% of nurses. The remaining nurses were working in primary healthcare or general practice. RIPLS data did not significantly depart from a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test, p=0.22), therefore parametric analysis was conducted using SPSS v.27 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, New York).

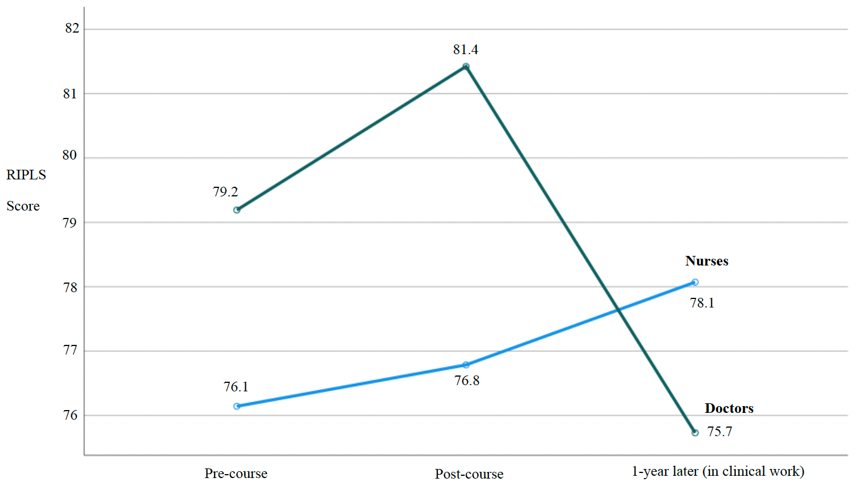

A one-way repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant interaction effect between time point and professional group (F(2, 76)=5.827, p=0.004), demonstrating that at the 1-year time point mean RIPLS scores for doctors fell significantly by 5.7 points, while mean RIPLS scores for nurses continued to increase by 1.3 points (Figure 1).

Figure 1. RIPLS scores for nurses and doctors paired over three time points

The results of the contextual questions in the present study (1-year time point) demonstrated strong support by nurses and doctors for the value of the interprofessional ACLS course in general terms and more specifically in terms of feeling part of the team, better understanding the skills and roles of others, and feeling more confident in clinical practice – with all mean responses ranging from high 3’s to >4 (see Supplementary Table 1 for complete summary). Participants strongly agreed that the interprofessional ACLS course should continue to be offered (with an overall mean score of 4.68 out of 5). The single reverse-scored question asking whether ACLS training would have been more effective if conducted uniprofessionally demonstrated strong disagreement with an overall mean score of 1.65. Exemplar quotations from free-form comments provided a context for the quantitative results in terms of demonstrating that the ACLS training better prepared doctors and nurses for emergencies, helped to improve their communication, and was a realistic form of training – for example, stating “Much more ‘real life’ when other professions involved” (doctor) and “Interdisciplinary teamwork is huge in the real world…” (nurse).

Despite the largely positive findings, exemplar quotations also allowed some insight into why doctors’ RIPLS scores were high at the end of the ACLS course, but then fell significantly upon entry into clinical practice at the 1-year time point. Exemplar quotations suggested that once in the clinical workplace junior doctors better appreciated that the technical skills in the ACLS course made up only a small part of their scope of practice, stating that there “are many things… you are unable to do and it is important to know what level of knowledge and ability other individuals may have” and that ACLS “does not make up a large part of my clinical practice” (Supplementary Table 1).

IV. DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate the translation of non-technical skills and attitudes acquired during undergraduate interprofessional simulation training to the clinical workplace. Our findings show particular benefits for nurses, and reinforce the value of the interprofessional ACLS course as an important part of the undergraduate curriculum. While the overall evaluation of the ACLS course was positive, the differential response in RIPLS scores between nurses and doctors upon entry into the clinical workplace is an intriguing result which clearly warrants further research.

We know of no previous study that has followed the same cohort of undergraduate participants after an interprofessional simulation course up to the point where they have entered the clinical workplace. The ability to pair responses for the same participants across all three time points in our study is a strength, as this avoids the variability that would be present if there were different participants at each time point, and so gives us more confidence in our findings.

Our results suggest that the significant reduction in RIPLS scores upon entry into the clinical workplace for junior doctors may be due to a realisation that the technical skills learnt in the ACLS course make up only a small part of a doctor’s domain of practice. However, recent research into the experiences of junior doctors during interprofessional collaboration suggests that the interaction effect in RIPLS scores across professional groups may also be a consequence of the different work cultures of nurses and doctors. Evidence suggests, including from our own University, that doctors typically believe that they should take individual responsibility for their clinical work, while nurses have a more collective view of patient care (Horsburgh et al., 2006; van Duin et al., 2022). Thus, the prevailing workplace cultures could reinforce and promote nurses’ willingness to work interprofessionally (hence explaining the increase in their RIPLS scores), while for doctors the prevailing individualistic work culture may reduce their willingness to work interprofessionally (hence contributing to the reduction in their RIPLS scores, Figure 1).

Further work to investigate this intriguing interaction effect, and the dynamics of work cultures and professional identity formation, would likely involve mixed-method research, perhaps using observation, interviews or focus groups and quantitative measures such as RIPLS (Jowsey et al., 2020). In addition, such studies conducted with clinicians at various levels of experience within a hospital could potentially yield insight into the state of the prevailing clinical work cultures and may allow some estimate of whether incoming graduates with interprofessional training could change these cultures, and when a critical mass of such graduates may allow this to happen. In the meantime, our results suggest that prevailing work cultures may represent a challenge for interprofessional teamwork initiatives, at least in medicine.

V. CONCLUSION

Our follow-up study demonstrated the translation of the non-technical skills and attitudes acquired during undergraduate interprofessional simulation training to the clinical workplace in terms of insights into the skills and roles of others, the importance of communication, and perceptions of preparedness to deal with emergencies. However, these results appear to be tempered for junior doctors beginning clinical work likely due to realisations around the applicability of ACLS training to their scope of practice and the influences of their prevailing workplace culture.

Notes on Contributors

Craig S. Webster was involved in the conceptualisation of this study, data analysis, writing and revision.

Antonia Verstappen was involved in data collection and analysis, writing and revision.

Jennifer M. Weller was involved in the conceptualisation of this study, writing and revision.

Marcus A. Henning was involved in the writing and revision of this paper.

Ethical Approval

This study was carried out in accordance with all regulations of the host organisation and with the approval of the Human Participants Ethics Committee of the University of Auckland (reference number 9073). All participants gave written informed consent to participate.

Data Availability

The complete data set for this study is openly available on the Figshare repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25750230

Funding

This study was conducted without funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Barnes, T., Yu, T. W., & Webster, C. S. (2021). Are we preparing medical students for their transition to clinical leaders? A national survey. Medical Science Educator, 31(1), 91-99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01122-9

Horsburgh, M., Perkins, R., Coyle, B., & Degeling, P. (2006). The professional subcultures of students entering medicine, nursing and pharmacy programmes. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 20(4), 425-431. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820600805233

Jowsey, T., Petersen, L., Mysko, C., Cooper-Ioelu, P., Herbst, P., Webster, C. S., Wearn, A., Marshall, D., Torrie, J., Lin, M. P., Beaver, P., Egan, J., Bacal, K., O’Callaghan, A., & Weller, J. (2020). Performativity, identity formation and professionalism: Ethnographic research to explore student experiences of clinical simulation training. PLoS One, 15(7), e0236085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236085

Parsell, G., & Bligh, J. (1999). The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Medical Education, 33(2), 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x

van Duin, T. S., de Carvalho Filho, M. A., Pype, P. F., Borgmann, S., Olovsson, M. H., Jaarsma, A. D. C., & Versluis, M. A. C. (2022). Junior doctors’ experiences with interprofessional collaboration: Wandering the landscape. Medical Education, 56(4), 418-431. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14711

Webster, C. S., Hallett, C., Torrie, J., Verstappen, A., Barrow, M., Moharib, M. M., & Weller, J. M. (2018). Advanced cardiac life support training in interprofessional teams of undergraduate nursing and medical students using mannequin-based simulation. Medical Science Educator, 28(1), 155-163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-017-0523-0

*Craig Webster

Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education

School of Medicine, University of Auckland

Private Bag 92-019

Auckland 1142, New Zealand.

Email: c.webster@auckland.ac.nz

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.