The use of creative writing and staged readings to foster empathetic awareness and critical thinking

Submitted: 28 July 2020

Accepted: 3 December 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 75-82

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/OA2366

Kirsty J Freeman1 & Brid Phillips2

1Office of Education, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 2Health Professions Education Unit, The University of Western Australia, Australia

Abstract

Introduction: Healthcare requires its practitioners, policymakers, stakeholders, and critics to have empathetic awareness and skills in critical thinking. Often these skills are neglected or lost in current educational programs aimed at those interested in the field of health. Health humanities and, in particular narrative medicine, aim to redress this omission.

Methods: We used a mixed methods approach to explore the experience of health humanities students in creative writing and staged readings to foster empathic awareness and critical thinking. Data was collected from 20 second-year students enrolled in an undergraduate health humanities unit via a post-assessment survey, and thematic analysis of a reflective paper.

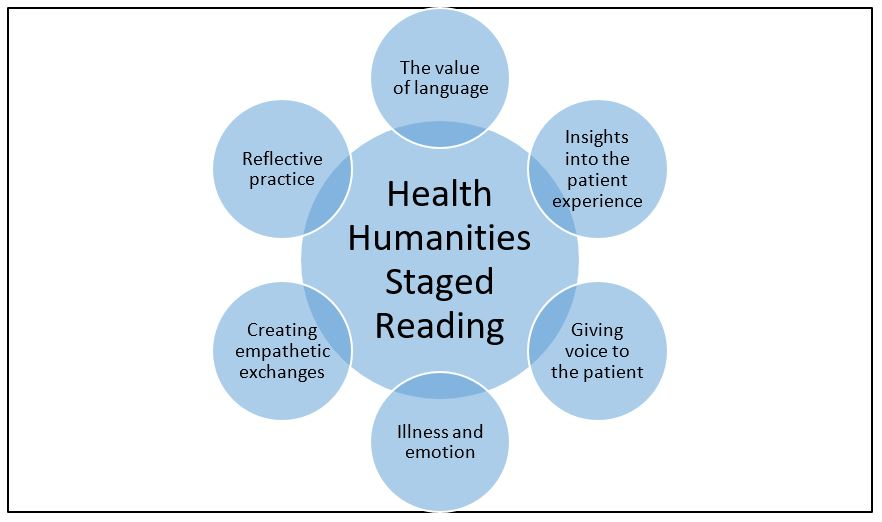

Results: 92.9% of the students felt that writing a creative piece helped them to understand the health topic from a different perspective, with 85.7% reporting that the use of creative writing helped to create emotional connections. From the reflective paper, six themes were elicited through the thematic data analysis: (1) The value of language; (2) Insights into the patient experience; (3) Giving voice to the patient; (4) Creating empathic exchanges; (5) Illness and emotion; and (6) Reflective practice.

Conclusion: By offering a mode of experiential learning involving both creative writing and staged readings, students develop empathic ways of thinking and being while deepening their critical engagement with a range of health topics. Students were able to understand the need to make humanistic sense of the health and well-being narrative, providing them with a range of transferable skills which will be an asset in any workplace.

Keywords: Narrative Medicine, Empathy, Critical Thinking, Staged Reading, Health Humanities

Practice Highlights

- Creative writing and staged readings are effective in fostering empathetic awareness and critical thinking.

- Narrative medicine techniques result in greater understanding about the perspectives of others.

- Developing creative language leads to enhanced communication skills and nuanced ways of thinking.

- Staged readings delivered online provide effective teaching and learning opportunities.

I. INTRODUCTION

Health humanities, and the attendant field of medical humanities, refer to the application of the creative or fine arts (visual arts, performing arts etc.) and humanities disciplines (literary studies, law, history, philosophy, etc.) to discussions and explorations on the nature of human health and well-being (Crawford et al., 2010). Within this broad umbrella lies the discipline of narrative medicine. The application of humanities to health has had a long pedigree, but the distinct disciplines of both narrative medicine and health humanities only began to emerge over the first decade of the 21st Century. In part, they emerged from a growing concern about an increasing lack of empathy in health professionals (Dean & McAllister, 2018; Lai, 2020). Narrative medicine with its interest in creativity and ambiguity strives to address this concern. Through narrative medicine, skills in thinking reflectively, listening actively, observing more closely and writing creatively can be developed. It has been shown that there is a positive impact on empathy and communication following narrative medicine education (Barber & Moreno-Leguizamon, 2017). This is important as the empathy conveying physician is more successful in promoting better clinical outcomes for patients. However, ‘[d]espite the centrality of stories to many of the tasks that clinicians perform it remains that explicit and formal teaching of knowledge and methods in narrative is relatively novel’ (Boudreau et al., 2012, p. 152).

One of the educational techniques embraced in narrative medicine is staged readings. A staged reading is an event which may have some rehearsal time, but the readers use scripts on stage. There is minimal staging, costuming, and props. This is pertinent as the use of theatre in academic teaching represents a new model of education that reminds students of the humanity of people (Baker et al., 2019). This form of engagement involves an emotional transaction through the spectacle of theatre which, as the Greeks understood it, was an occasion that provided recognition, catharsis, and release for both the individual and the wider community (Shapiro & Hunt, 2003). Health topics are also more easily understood through the medium of performance (Ünalan et al., 2009). Ünalan et al. (2009) also surmised that theatrical performance could increase empathy levels. There are similar benefits to be had from staged medical readings which foster introspection and reflection (Matharu et al., 2011). The purpose of this study was to determine whether the use of creative writing and staged readings could develop empathy and critical thinking in second year university students enrolled in an undergraduate health humanities unit of study. Student enrolment information confirms majority of students are on a pathway to studying medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, ophthalmology, or global health.

A. Context

In semester one of 2020, 20 second-year students were enrolled in a narrative medicine unit, as part of their undergraduate bachelor’s degree. By delivering an undergraduate unit in narrative medicine, the goal is to give students the opportunity:

- To dip their toes into the world of literary fiction.

- To present their own creative pieces relating to health topics.

- To gain an understanding of health issues from the perspective of others as this increases empathetic awareness.

Through a series of scaffolded assessments, students have a unique opportunity to develop empathetic awareness and critical thinking skills through creative presentations mimicking staged readings.

Two of the three assessments related to the staged reading, the second assessment was a creative piece and the third was a reflection on process of creating the piece and the health topic to which it related. The purpose of these assessments was to demonstrate different modes of narrative writing. This was achieved through the construction of a creative piece that explored a health topic using narrative medicine techniques including but not limited to short story writing, poetry, and play writing.

The unit involved supporting students to devise a short creative writing piece. Within the piece, themes of empathy, communication, cultural difference, and societal biases and assumptions around the students’ chosen health topics were explored. The piece was then to be presented as a staged reading by the students for an invited audience. The audience would include the wider university community of undergraduate and postgraduate students, staff, and invited guests such as health professionals to the reading. Immediately following their reading, the students, supported by academic staff, were to hold a guided discussion on the significance of health topics in the piece. This discussion would bring biases and assumptions into focus and heighten the individual’s awareness of emotional dynamics at work in the healthcare context while also offering insights into the perspective of others. Similar programs have been used to educate bioethical students, help them to develop discussion questions, and enhance their critical self-reflection (Kerr et al., 2020; Robeson & King, 2017).

Students were required to read a literary fiction novel, Extinctions (Wilson, 2020). The act of reading itself has demonstrated benefits of improving processing of experiences and developing empathy. Reading literature also improves our social awareness and our ability to see the perspectives of others (Fennelly, 2020; Kaptein et al., 2018). In the novel Extinctions, there are many discernible health topics such as traumatic brain injury, drug use, ageing, mobility issues, death and dying, and loss of independence. There is also a range of characters involved in these issues from a young girl with a drug problem to the protagonist, Fred, a man in his declining years. It was important to foster student engagement with the project by offering a fully scaffolded experience to allay performance anxieties. Scaffolding has been shown to support students as they negotiate a challenging environment and allow them to make meaning for themselves rather than have it imposed on them from an autocratic perspective (Wilson, 2016). Each week from the first week of semester, the seminar included both a close reading exercise and a creative writing exercise. The scaffolding also included several resource folders addressing the main genres the students were encouraged to explore – short story, poetry, drama. The folders contained videos, book chapters, blog posts, and journal articles that introduced the students to ways of writing creatively. There was also a dedicated workshop which explored these techniques and answered any questions the students had on creative writing.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions on social gatherings and the cancellation of face-to-face interactions, the presentation aspect had to be cancelled at short notice and instead, presentations took place online without the wider audience participation. The creative pieces were read in an online forum limited to students and the unit coordinator. The students had the opportunity to read their work to other participating students and to lead a short discussion on their health topic. This sharing is important as ‘representation is always a dialogue, in which, the receiver of the work contributes a necessary response to the creator of the work’ (Charon et al., 2016, p. 347). As the students based their pieces on fully rounded characters from the novel, this process shares similarities with verbatim theatre. Verbatim theatre has been shown to allow positive exploration of emotional behaviours (Scott et al., 2017). After this process, students were encouraged to incorporate feedback from the presentations into their pieces before submission of the creative piece.

The third assessment component of the unit required the students to submit a reflective essay on the experience where they discuss the creative process and their representation of the health topic which they had chosen. They had to discuss the significance of the health topic and examine their personal responses to the topic and how it was influenced by their research, the creative process, and the discussions which took place following the presentation of the piece. To support the reflective process, we developed a reflective writing toolkit which illustrates both the process and its importance.

II. METHODS

A cross-sectional mixed methods design was used to evaluate the experience of health humanities students in creative writing and staged readings to foster empathic awareness and critical thinking. 20 second-year students who were enrolled in a narrative medicine unit between January and June 2020 were invited to participate.

A. Data Collection and Analysis

Data was collected at two points over the semester, an online survey in week 10, and a reflective paper at the end of semester in week 13.

1) Creative writing and staged reading assessment student experience survey: All 20 undergraduate students enrolled in the unit in semester one, 2020, were invited to participate in an online survey examining the student experience of participating in the creative writing and staged reading assessment. The survey tool curated by author one (KF) was designed to collect basic demographic data about the student, along with information about their current enrolment. The survey was designed to evaluate the first two level of Kirkpatrick’s model of program evaluation, level one being reaction and level two learning (Frye & Hemmer, 2012). Given that this is the first time the program had been offered, the authors felt that the data collected would provide a baseline upon which further detailed evaluations can build upon. Students were asked to rate their experience with the staged reading project using a five-point Likert scale, as well as responding to open-ended questions designed to further expand on the students’ experience. A statement of voluntary consent was included at the start of the survey and the participant had to agree to the consent before the survey could commence. Thus participation in the anonymized online evaluation indicates consent. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographic data. Categorical data are presented as number and percentage. The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0. Thematic analysis of the open-ended questions was then undertaken. Researcher bias was minimised by having author one (KF), who was not involved in delivering the course, undertake the analysis of the survey data.

2) Staged reading reflective essay: The second data collection point was a reflective essay (n=20). Thematic analysis of the text was undertaken by both authors. Each author reviewed the transcripts separately, making note of key phrases, outline possible categories or themes. Discussion of our interpretations took place over teleconference, as we then jointly rearranged and renamed the codes, developing higher order themes. NVivo 12™ was used to manage the qualitative data (QSR International., 2018). This mixed methods design combines quantitative and qualitative data to provide a richer source of information about the experience of staged readings.

III. RESULTS

A. Creative Writing and Staged Reading Assessment Student Experience Survey

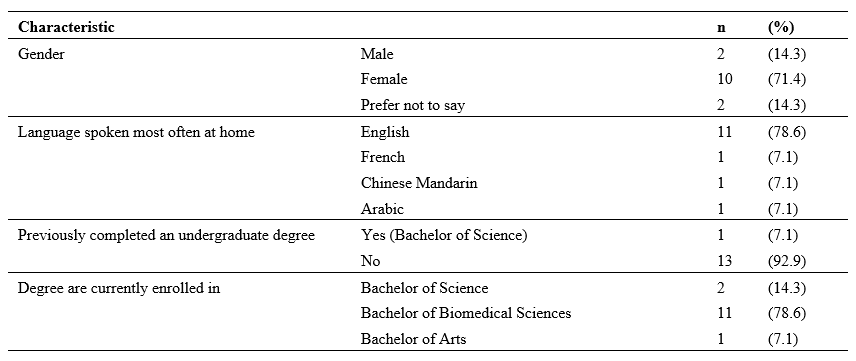

Of the 20 students enrolled in the unit, 14 completed the student experience survey, a response rate of 70%. Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the respondents. As can be seen in Table 1, the students were enrolled in one of three bachelor degrees. The degree enrolled by majority of students in is science based, with only 1 respondent studying an Arts based degree. 92.8% of respondents had not previously completed an undergraduate degree. Three respondents spoke languages other than English at home.

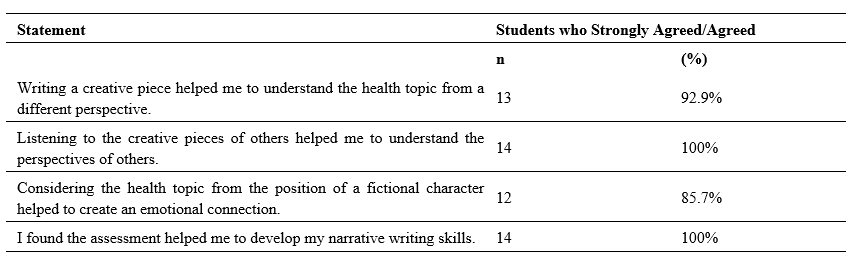

When asked to rate their experience in the staged reading project 92.9% of the respondents felt that writing a creative piece helped them to understand the health topic from a different perspective; with 85.7% reporting that the use of creative writing helped to create emotional connections (Table 2).

Table 1. Summary of demographic characteristics of respondents

Table 2. Student rating of creative writing and staged reading assessment

When asked to describe their experience of the staged reading assessment in the free text survey questions students reported feeling daunted, nervous and apprehensive about the prospect of writing a creative piece, as many of them shared that they had little or no experience with creative writing. With several students describing to task as challenging, on reflection they expressed feeling fulfilled, enriched, sharing that they found the task rewarding.

A. Staged Reading Reflective Essay

The qualitative data analysis resulted in six themes being identified: (1) The value of language; (2) Insights into the patient experience; (3) Giving voice to the patient; (4) Creating empathic exchanges; (5) Illness and emotion; and (6) Reflective practice (Figure 2). These themes are described in this section, illustrated with representative quotes.

Figure 1. Overview of the staged reading themes

1) The value of language: as they worked through their creative piece, students discovered the value and power of language as a tool for expression and communication. Students commented on their appreciation of language:

Since I wanted to create a powerful and emotional piece, I experimented using literacy techniques to achieve a desperate and anxious tone.

Student 2

I learnt that the use of language is also vital in writing a creative piece, emphasising the importance of communication between the author and readers.

Student 14

2) Insights into the patient experience: Students developed an awareness of the value of research when trying to understand the issues surrounding health topics. Better equipped with quality knowledge and research, they were able to give more nuanced accounts of health experiences. Students learned the value of looking beyond the symptom to see the whole person and, thus the value and importance of person-centred care:

Acknowledging that my research and reflections had resulted in greater understandings of both the health topic and the importance of seeing a patient beyond their physical disease.

Student 2

It is very important to take into consideration all aspects of what a person is experiencing in order to make the best assessment and to come up with the best route of action to help the patient overcome whatever it is they are suffering from.

Student 1

3) Giving voice to the patient: Students gained an insight into the need to give a voice to patients in order to gain better understanding of the perspectives of others. They reflected on the powerlessness and silence that often surrounds certain conditions and situations:

I felt that I was able to give Katie an authentic voice, through which readers were then able to empathise with, and better understand, her struggles.

Student 4

Furthermore, the narratives of victims can empower them by giving them a voice in times when they are often silenced.

Student 7

4) Creating empathetic exchanges: Students gained an understanding of empathetic exchanges and in some instances understood the need to create opportunities for the development of empathy. The students did not always articulate the word empathy but instead alluded to the concept by talking about experiencing and understanding the emotions and perspectives of others:

I felt increased levels of empathy towards individuals dealing with the disorder as I now understand the many other challenges and hurdles that accompany eating disorders that I didn’t know prior to this assignment.

Student 8

When using these descriptions, I felt that I was able to build an emotional connection with Katie’s character, thus encouraging readers to also empathise with her situation.

Student 4

5) Illness and emotion: Students discovered that emotional transactions and states are intertwined with health and illness. They understood, through their work, the interconnectiveness of emotional responses and illness. Some of their observations included:

I have become more sensitive to the idea that human beings are inherently emotional and can be affectively moved when provided with an impetus.

Student 3

The purpose of the piece was unearthing the complex thoughts and emotions individuals with eating disorders and substance abuse go through.

Student 8

6) Reflective Practice: On topics where students previously had felt knowledgeable, deeper reflection and considerations revealed their own misconceptions and lack of knowledge. Within this paradigm, they also showed a maturation of habits and behaviours. Their comments were insightful:

I entered a phase of reflection where I realised that I would have previously contributed to these harmful views.

Student 2

I learnt and later researched further the differences in the perception of STEM women in both Western and Asian populations. This is something I would attempt to change. It was really interesting for me to discover that I had this unconscious bias forcing me to further expand my learning and knowledge in the area.

Student 18

IV. DISCUSSION

While the use of creative writing and staged readings is a developing area in health humanities, the findings of this study suggest that they are effective in fostering emotional awareness and critical thinking. McDonald et al. (2015) found that ‘[a]nalysis of the student’s writing showed that they demonstrated the ability to “stand in another’s shoes” and, interestingly, the students’ comments on their own writing showed that their ability to relate to characters they initially felt little affinity for deepened’ (McDonald et al., 2015, p. 9).

By taking part in the creative writing project and the accompanying reflection piece, students were exposed to an innovative and experiential form of learning that provided a unique pedagogical experience. Whilst the students reported being daunted at the thought of constructing a creative piece, the self-reflective processes and actively engaging with the perspectives of others, ensured students were able to enhance their critical thinking skills. In the creative writing and staged reading assessment student experience survey, 100% of students agreed, “Listening to the creative pieces of others helped me to understand the perspectives of others”. This accords with the work of Deloney and Graham who note “[e]xperiential learning activities increase student engagement and are a helpful tool to connect abstract ideas with concrete knowledge” (Deloney & Graham, 2003, p. 249).

The findings of this study highlight the value of language as a tool for expression and communication. Educators need to be mindful of their student population when contemplating incorporating creative writing and staged readings into their programs. For students to be accepted for enrolment at The University of Western Australia they must demonstrate a minimum level of English language proficiency necessary for academic studies. Whilst there has been several studies examining what Hyland calls “linguistics disadvantage in terms of a Native/non-Native divide” (Hyland, 2016, p. 61) in academic writing (Badenhorst et al., 2015; Bocanegra-Valle, 2014; Zhao, 2017), the impact of this linguistic divide in creative writing and staged readings has not been fully explored.

The students gained insights into holistic care relating to both themselves and others. As these are undergraduate students, many on a pathway to a career in health, insights into holistic care and self-care are valuable life lessons. There was also an indication that the process contributed to the social and cultural well-being of themselves and others. Nagji et al. (2013) note that theatre based programs/novel humanities based curriculum items contribute to student well-being, an increasingly important area for universities to address particularly during a pandemic. Although the student population participating in this unit are studying science-based degrees where creative writing is not commonplace, the learning strategies were structured in a way that enabled development of narrative writing skills.

By integrating the narrative medicine techniques of creative writing and staged readings the students were able to give more nuanced accounts of health experiences. Students learned the value of looking beyond the symptom to see the whole person and, thus the value and importance of person-centred care. This gave them valuable insights into the patient experience. During this process, students gained an insight into the need to give a voice to patients in order to gain better understanding of the perspectives of others. They learnt about the powerlessness and silence that often surrounds certain conditions and situations. In their responses, the students did not always articulate the word empathy but instead alluded to the concept by talking about experiencing and understanding the emotions and perspectives of others. Students gained an understanding of the power of empathetic exchanges and in some instances understood the importance of creating empathetic exchanges opportunities. Another important theme which was uncovered, was a growing awareness amongst students that emotional transactions and states are intertwined with health and illness. They understood, through their work, the interconnectiveness of illness and emotion. On topics where students previously had felt knowledgeable, deeper reflection and considerations revealed their own misconceptions and lack of knowledge. Within this paradigm, they also showed a maturation of habits and behaviours leading to improved reflective practices.

There were limitations with the project as we had to move from face-to-face to online teaching due to constraints placed upon teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the online format did have some unexpected benefits, with a number of students feeling less intimidated when presenting online compared to a face-to-face workshop. Despite the move to online teaching, the cohort remained present and engaged in the project. Many expressed regrets at losing physical contact and the incidental discussions that happen before and after classes but overall with support they adapted well.

V. CONCLUSION

This study has described the experience of students engaging in creative writing and staged readings as part of a narrative medicine unit. Students completing the unit and its attendant assessments developed useful life skills including critical thinking, understanding the perspectives of others, and the positive use of narrative in appreciating the experiences of others. The work engaged them in new and innovative ways evidenced by some statements which noted that their experience in this unit was unique in their university journey. Having autonomy over the health topic they chose, the character they explored, and the creative medium they used to express their thinking, enhanced the learning experience and allowed them to meet the learning outcomes of the unit.

Notes on Contributors

Kirsty J Freeman crafted the paper with her co-author, performed the data collection and analysis of the survey, and undertook thematic analysis of the reflective essays. Dr Brid Phillips crafted the paper with her co-author, conducted the literature search, and undertook thematic analysis of the reflective essays. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee: HREC RA/4/20/5254.

Data Availability

All relevant quantitative data are within the manuscript. The qualitative data collected for this manuscript originates from assessment items submitted as part of the participants’ academic studies. The authors do not have consent to upload this data into a data repository.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thanks the students who participated in this unit and their willingness to adapt to the online platform with grace and enthusiasm.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Badenhorst, C., Moloney, C., Rosales, J., Dyer, J., & Ru, L. (2015). Beyond deficit: Graduate student research-writing pedagogies. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.945160

Baker, H. F., Moreland, P. J., Thompson, L. M., Clark-Youngblood, E. M., Solell-Knepler, P. R., Palmietto, N. L., & Gossett, N. A. (2019). Building empathy and professional skills in global health nursing through theatre monologues. The Journal of Nursing Education, 58(11), 653-656. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20191021-07

Barber, S., & Moreno-Leguizamon, C. J. (2017). Can narrative medicine education contribute to the delivery of compassionate care? A review of the literature. Medical Humanities, 43(3), 199-203. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2017-011242

Bocanegra-Valle, A. (2014). ‘English is my default academic language’: Voices from LSP scholars publishing in a multilingual journal. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13(1), 65-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.10.010

Boudreau, J. D., Liben, S., & Fuks, A. (2012). A faculty development workshop in narrative-based reflective writing. Perspectives on Medical Education, 1(3), 143-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-012-0021-4

Charon, R., Hermann, N., & Devlin, M. J. (2016). Close reading and creative writing in clinical education: Teaching attention, representation, and affiliation. Academic Medicine, 91(3), 345-350. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000827

Crawford, P., Brown, B., Tischler, V., & Baker, C. (2010). Health humanities: The future of medical humanities? Mental Health Review Journal, 15(3), 4-10. https://doi.org/10.5042/mhrj.2010.0654

Dean, S., & McAllister, M. (2018). How education must reawaken empathy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(2), 233-234. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13239

Deloney, L. A., & Graham, C. J. (2003). Wit: Using drama to teach first-year medical students about empathy and compassion. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(4), 247-251. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1504_06

Fennelly, B. A. (2020, May 15). What’s the use of reading? Literature and empathy [Video] . https://youtu.be/9nJv8sxpUKU

Frye, A. W., & Hemmer, P. A. (2012). Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Medical Teacher, 34(5), e288-299. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.668637

Hyland, K. (2016). Academic publishing and the myth of linguistic injustice. Journal of Second Language Writing, 31, 58-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.01.005

Kaptein, A., Hughes, B., Murray, M., & Smyth, J. (2018). Start making sense: Art informing health psychology. Health Psychology Open, 5(1), 205510291876004. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102918760042

Kerr, A., Biechler, M., Kachmar, U., Palocko, B., & Shaub, T. (2020). Confessions of a reluctant caregiver palliative educational program: Using readers’ theater to teach end-of-life communication in undergraduate medical education. Health Communication, 35(2), 192-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1550471

Lai, C.-W. (2020). “Booster shots” of humanism at bedside teaching. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(2), 45-47. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/PV1085

Matharu, K. S., Howell, J., & Fitzgerald, F. (2011). Drama and empathy in medical education: Drama and empathy. Literature Compass, 8(7), 443-454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2011.00778.x

McDonald, P., Ashton, K., Barratt, R., Doyle, S., Imeson, D., Meir, A., & Risser, G. (2015). Clinical realism: A new literary genre and a potential tool for encouraging empathy in medical students. BMC Medical Education, 15(1), 112-112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0372-8

Nagji, A., Brett-MacLean, P., & Breault, L. (2013). Exploring the benefits of an optional theatre module on medical student well-being. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 25(3), 201-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2013.801774

QSR International. (2018). NVivo 12 [Software]. In https://qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products/

Robeson, R., & King, N. (2017). Performable case studies in ethics education. Healthcare, 5(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5030057

Scott, K. M., Berlec, Š., Nash, L., Hooker, L., Dwyer, P., Macneill, P., River, J., & Ivory, K. (2017). Grace under pressure: A drama-based approach to tackling mistreatment of medical students. Medical Humanities, 43(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2016-011031

Shapiro, J., & Hunt, L. (2003). All the world’s a stage: The use of theatrical performance in medical education. Medical Education, 37(10), 922-927. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01634.x

Ünalan, P. C., Uzuner, A., Ifçili, S., Akman, M., Hancolu, S., & Thulesius, H. O. (2009). Using theatre in education in a traditional lecture oriented medical curriculum. BMC Medical Education, 9(1), 73-73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-73

Wilson, J. (2020). Extinctions. UWA Publishing.

Wilson, K. (2016). Critical reading, critical thinking: Delicate scaffolding in english for academic purposes (EAP). Thinking Skills and Creativity, 22, 256-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.10.002

Zhao, J. (2017). Native speaker advantage in academic writing? Conjunctive realizations in EAP writing by four groups of writers. Ampersand, 4, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2017.07.001

*Kirsty J Freeman

Duke-NUS Medical School

8 College Road, Singapore 169857

Tel:+65 89219676

Email: kirsty.freeman@duke-nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.