‘Surviving to thriving’: Leading health professions’ education through change, crisis & uncertainty

Submitted: 28 August 2020

Accepted: 3 March 2021

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 32-44

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/OA2385

Judy McKimm1, Subha Ramani2 & Vishna Devi Nadarajah3

1Swansea University Medical School, United Kingdom; 2Harvard Medical School, United States of America; 3International Medical University, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has caused huge change and uncertainty for universities, faculty, and students around the world. For many health professions’ education (HPE) leaders, the pandemic has caused unforeseen crises, such as closure of campuses, uncertainty over student numbers and finances and an almost overnight shift to online learning and assessment.

Methods: In this article, we explore a range of leadership approaches, some of which are more applicable to times of crisis, and others which will be required to take forward a vision for an uncertain future. We focus on leadership and change, crisis and uncertainty, conceptualising ‘leadership’ as comprising the three interrelated elements of leadership, management and followership. These elements operate at various levels – intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational and global systems levels.

Results: Effective leaders are often seen as being able to thrive in times of crisis – the traditional ‘hero leader’ – however, leadership in rapidly changing, complex and uncertain situations needs to be much more nuanced, adaptive and flexible.

Conclusion: From the many leadership theories and approaches available, we suggest some specific approaches that leaders might choose in order to work with their teams and organisations through these rapidly changing and challenging times.

Keywords: Leadership, Followership, Management, Health Professions Education, Change, Crisis, Uncertainty, Emotional Intelligence, COVID-19 Pandemic, Universities

Practice Highlights

- In rapid change and uncertainty, different leadership approaches are needed.

- Primal leadership and emotional intelligence are essential.

- Followers need to feel safe, physically and psychologically.

- Authentic and inclusive leadership draws from diverse views.

- Adaptive and regenerative leadership acknowledges interrelated systems.

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused huge change and uncertainty for universities and their stakeholders around the world. For many health professions education (HPE) leaders, the pandemic has caused an unforeseen crisis, the ripples from which will probably be felt for years to come. Effective leaders are often seen as being able to thrive in times of crisis – the traditional ‘hero leader’ – however, leadership in rapidly changing, complex and uncertain situations need to be much more nuanced and flexible. In this article we explore leadership approaches, some of which are more applicable to times of crisis, and others which will be required to take forward a vision for the ‘new normal’ to ensure that we learn from our experiences during the pandemic.

In this article we focus on leadership and change. We start with an overview of the leadership triad, a discussion of the educational challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by detailed discussion of effective leadership styles and competencies during challenging situations, approaching these through three lenses: Intrapersonal, referring to characteristics that successful leaders possess; interpersonal, referring to leadership styles and approaches leaders can adopt when they interact with others; and system level, which refers to leadership attributes to effectively lead organisations during a crisis. We conceptualise ‘leadership’ as comprising three interrelated elements: leadership, management, and followership (see Figure 1), which we call the ‘leadership triad’ (McKimm & O’Sullivan, 2016).

Figure 1: The Leadership Triad

Note: From “When I say … leadership,” by J. McKimm, and H. O’Sullivan, 2016, Medical Education, 50(9), 896–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13119

Leadership is about change and movement, putting the power and energy into a system or initiative, whereas management provides the means of enacting the leadership vision and making change happen. Leadership is always about ‘people’ (motivating them towards goals or activities) whereas management is about systems, processes and policies and we structure the article around this approach (Scouller, 2011). Followership provides the leadership with the ‘people power’ to enact the change; without followers, leadership cannot happen as leaders cannot do everything themselves. Even the most senior leaders do not ‘lead’ all the time, in ‘real life’ we move around these three elements as we lead, manage, and follow in various situations.

As leaders in HPE ourselves (Refer to Appendix A), we reflect and ask, what can a leader do during this period to ensure the best interest of all stakeholders? What lessons can we offer from our own experiences and the experiences of other leaders to those who need guidance to weather and even thrive after the crisis? The approach we have taken is to first examine the major challenges facing health professions’ leaders during this crisis, we then offer specific leadership approaches that can effectively address these challenges, concluding with change management approaches required to prepare and sustain the new normal.

II. CRISIS AND CHALLENGES FOR HEALTH PROFESSIONS EDUCATION

2020 has been a hugely challenging year for all higher education leaders across the world. From managing the rapid switch to online learning, answering student calls for some form of refund or reduction in fees, to expanded support for students and staff including emotional support, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced educational leaders to manage a different type of crisis altogether.

HPE leadership has been hugely tested during the pandemic ‘crisis’ which is very different from leading in ‘normal’ times. How do we define a crisis? A crisis is any event that could lead to an unstable, difficult and/or dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, community, or whole society. It means that difficult or important decisions must be made amidst great uncertainty and lack of information about what the future might hold. In the middle of a crisis everything can feel like it is failing or impossible. The pandemic accelerated and exacerbated many of the challenges already being experienced in HPE, including the rising costs of operating universities, increase in tuition fees and accessibility to higher education, and competition from commercial and online learning providers. Leaders in HPE face additional and different sets of challenges, as they service and are dependent on both the education and health care sectors for student education and postgraduate training. The crisis is not only experienced at organisational or team level, but the pandemic has also impacted individuals (students, academic faculty, clinical teachers, and healthcare staff) whose normal coping mechanisms may be insufficient.

However, this is not all negative and leaders need to tap into a growth mind-set, which has been defined as one that views failure and challenges as learning opportunities (Dweck, 2016). For example, Kanter (2020) suggests that it is possible to come out of a crisis stronger than before if leaders operate with a ‘people first culture’ and pay ‘attention to three things: establish clear accountability in the leadership ranks; develop a nuts-and-bolts, collaborative plan for getting through the crisis; and appoint a separate group in charge of defining the “new normal,” when the worst is over’.

It is also important to recognise that the pandemic (set alongside climate change and causes related to systemic social injustices) has foregrounded and increased awareness on inequalities across the globe in many areas, including HPE. Leadership in these times needs to pay close attention to this and seize the moment to facilitate and mobilise real change within their institutions or communities. Perhaps more so when such institutions train future health professionals and develop future leaders, who need to believe that a positive change is possible and that their own cultural context can be celebrated.

III. WHAT SORT OF LEADERSHIP IS NEEDED TO ADDRESS THESE CHALLENGES?

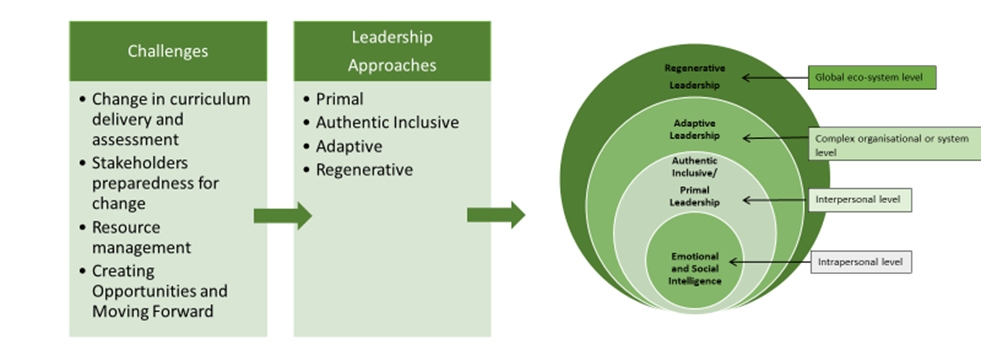

Inevitably changes are to be expected as the impact of the pandemic is unprecedented and is a matter of national security and public health. In most countries, governance and decision making during this crisis will be by National security councils with advisories or guidelines offered by ministries of health higher education, home affairs, or other relevant bodies. This means that universities and educational leaders who usually have autonomy in decision making are subject to stricter controls and frequent changes from authorities who are understandably making decisions at national and international levels. For people in leadership positions, this is unchartered territory and given the ‘traditional’ power and authority hierarchies and processes in higher education and health professions education, it is unsurprising that leaders may feel helpless during a crisis such as this. In Figure 2, we list four levels along which leadership needs to be enacted, and some suggested approaches to help leaders move out of this feeling of helplessness so that they can lead the people for whom they are responsible.

Figure 2: Four levels of leadership for addressing challenges during a crisis

Note: Drawing from “ABC of clinical leadership,” by T. Swanwick and J. McKimm, 2017, John Wiley & Sons.

A. The Intrapersonal Level: Working with Emotional and Social Intelligence

Challenging circumstances which force change, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, result in a range of emotional responses among leaders and all those for whom they are responsible.

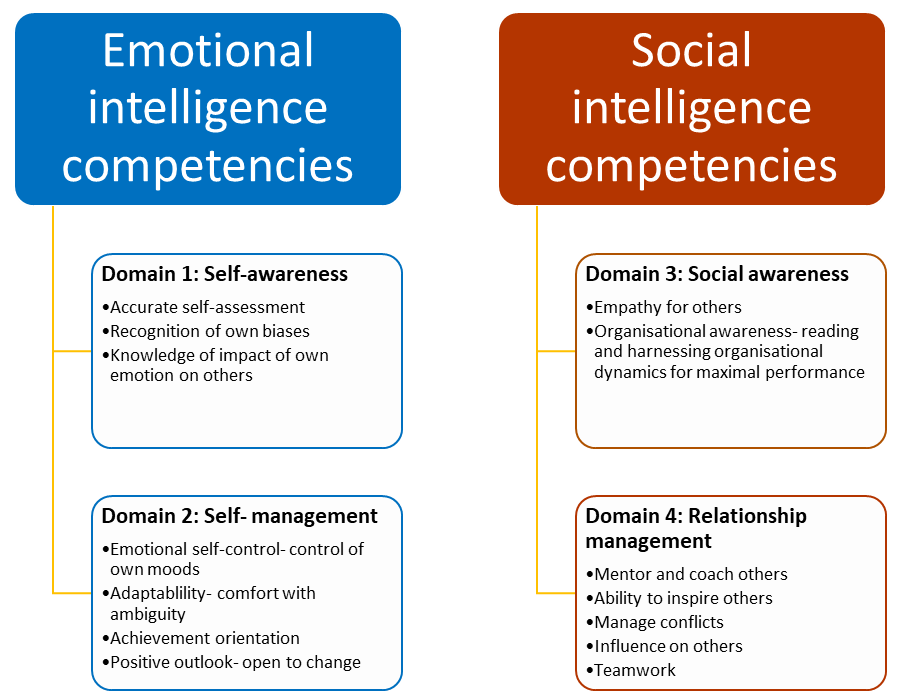

In 1998, Daniel Goleman proposed that leadership skills such as toughness, vision, determination, and intelligence alone are insufficient. He stated that the most successful leaders also possess a high degree of emotional intelligence (EI) which includes the traits of self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills (Goleman, 1998). Boyatzis and Goleman went to analyse the core attributes that were present in those identified by a variety of companies as their most successful leaders. As a result, twelve competencies of emotional and social intelligence were described under four domains and depicted in Figure 3. The four domains include: Self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management; these are critical attributes for leaders to operate effectively through own and others’ emotions during challenging circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic. These competencies and behaviours help to simplify a complex construct such as EI and can facilitate leadership development in this area.

Figure 3: Intrapersonal leadership attributes: Emotional and social intelligence competencies essential to lead and manage change during challenging circumstances.

Note: Adapted from “Competencies as a behavioral approach to emotional intelligence,” by R. E. Boyatzis, 2009, Journal of Management Development, 28(9), 749–770. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710910987647

While the construct of EI and competencies can serve as a useful guide to leaders in leading and managing change, the actual behaviours that are most effective depend on the organisational culture and the societal culture within which an organisation is situated. Moreover, at institutions which feature diversity in the composition of its leaders, staff and learners, leaders should recognise that individuals on a team might have different emotional reactions even when working towards a common goal. All four domains of EI competencies are essential for leaders to manage the groups of people they lead (See Table 1).

|

1. Self-awareness allows leaders to recognise their assumptions and biases, and how they affect their worldview. 2. Self-management promotes thought before action and ability to manage own emotions and reactions, important in reigning in negative emotion. 3. Social awareness allows leaders to understand the individuals who make up their team and recognise differences in viewpoints and personalities. 4. Relationship management is essential to welcome a variety of perspectives, nurture talent, and maximise the potential and productivity of individuals, teams, and the organisation. Mentoring and coaching skills fall under this domain.

|

Table 1: The impact of the four EI domains

A. The Interpersonal Level: Influencing Others and Drawing on Their Individual and Collective Strengths

In rapid change and uncertainty, what people want from their leaders is an authentic voice and to feel that leaders are listening, taking their concerns seriously and that they have the expertise and authority to lead and manage change. Leaders are created and maintained by how their followers see, relate to, and trust them (Uhl-Bien & Carsten, 2018). Simon Sinek talks about how followers will follow their leaders into highly unsafe situations (such as war) if they feel their leaders can keep them safe and that they are ‘in it’ together (Sinek, 2014). Whilst internally, leaders may feel as lost and at sea as those for whom they are responsible, they must draw on their own resilience and ‘grit’ (Duckworth & Duckworth, 2016) to step up and provide effective leadership. This involves displaying courage, putting personal interests aside to achieve what needs to be done and acting on convictions and principles even when it requires personal risk-taking. In crisis or uncertainty, followers need leaders who can communicate clearly, transparently, and regularly, who can make decisions (even if these are unpopular or later change) and who look out for and care for them (Paixão et al., 2020).

Primal leadership, described by EI experts, emphasises that leaders’ emotional affect and mood is a major driver of the mood and behaviours of others around them (Goleman et al., 2001). Thus, during a crisis, leaders need to be optimistic, yet, authentic and realistic. Positive emotion or resonance is critical to motivate people, allow them to be productive amidst chaos and preserve their wellbeing. As the pandemic spread around the world, some academic leaders demonstrated a highly person-centred approach in relation to staff and students, recognising their fears and anxieties, encouraging virtual education and work whenever possible, thus demonstrating primal leadership as well as cultural intelligence (Liao & Thomas, 2020; Velarde et al., 2020). If we want people to work interprofessional, pay attention to well-being and motivation, and work together to meet organisational goals, then flattening hierarchies is essential to generate ideas and functional collaboration (Barrow et al., 2011; Barrow et al., 2014) (Refer to Appendix B).

Whilst leaders may need to take a ‘command and control’ type of leadership in times of great crisis because important decisions must be taken and communicated quickly, after the immediate crisis other approaches will be helpful. For example, authentic, altruistic, person-centred, and inclusive leadership (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Cardiff et al., 2018; Hollander, 2012; Sosik et al., 2009) approaches are very much focussed on the leader drawing from their own strengths and, through awareness and acknowledgement of their own weaknesses and biases, proactively seeking a range of perspectives on issues and demonstrating that they value and listen to those around them. When leaders are trying to make impactful decisions in times of uncertainty, having a range of views and ideas is essential. Leaders may also need to show intellectual humility – admitting mistakes, learning from criticism and different points of view, and acknowledging and seeking contributions of others to overcome limitations. As tasks are defined, leaders need to empower and demonstrate their confidence in people by delegating and holding them responsible for activities they can control.

B. The Complex Organisation or System Level: Adaptive Leadership

While conventional approaches to leadership and management have their place, as the pandemic elapsed around the world leaders needed to be highly adaptive and flexible, adjusting their outcomes and approaches based on rapidly changing information. Because we live in a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous)

(Worley & Jules, 2020) and RUPT (Rapid, Uncertain, Paradoxical, Tangled) (Till, Dutta, McKimm, 2016) world, leadership is needed that is flexible and agile enough to adapt to circumstances which most HPEs have not experienced before.

Adaptive leadership (Heifetz et al., 2009; Randall & Coakley, 2007) is specifically focussed on leadership in complex systems or situations and is helpful when thinking about how to respond to change, uncertainty, and crisis. Adaptive leaders do not simply work in a technical way (by just applying familiar management processes and ways of working) but involve people throughout the organisation to help solve ‘wicked’ problems, which may not have a clear solution and may require new ways of working. Adaptive leaders create the organisational conditions that enable dynamic networks and environments to achieve agreed goals in uncertain environments. Adaptive leadership focuses on four dimensions: Navigating organisational/system environments; leading with empathy; learning through self-correction and reflection and creating win-win solutions. These dimensions have many parallels with EI competencies. One of the most useful concepts in adaptive leadership which helps leaders to make decisions, is the ability to diagnose the ‘precious’ from the ‘expendable’ (Heifetz et al., 2009). What do we mean by this? The ‘precious’ is what is vitally important to the organisation; in education this is the learners themselves, the faculty, and the quality of educational provision – you do not want to lose the focus on these as you respond to crisis and change. What is ‘expendable’? Because of campus closures due to the pandemic, suddenly the large lecture theatres, shiny new buildings, and campuses that many universities see as artefacts of success and prestige, were expendable. Once the ‘new normal’ emerges, we will no doubt see a return to campuses and utilisation of buildings again, but adaptive leaders recognise what is precious and make sure that this is looked after and nurtured. We must remember this once the immediate crises are past (Refer to Appendix C).

C. The Global Eco-System Level: A Focus on Healing and Regeneration

The pandemic has highlighted starkly that the world, its countries, people, and structures are highly interconnected. In such times what affects one country, and actions (or inactions) cause ripples across the globe. We have already alluded to the need for leaders to work collaboratively and share practices, and during the pandemic we have seen multiple examples of international collaboration and the sharing of practice by HPEs everywhere. When we are all in the same boat, we need to sail in the same direction.

As well as being willing and proactive in collaborating on finding solutions to common challenges, leaders in HPE also need to consider the wider implications of the impact of climate change and human activities on health and health care. McKimm and McLean (2020) make the case for an ‘eco-ethical’ leadership approach which focuses leaders’ minds on the need for sustainable health professions’ education and practices. Another approach that is very relevant to HPE and its response to the pandemic is that of ‘regenerative’ leadership (Hutchins & Storm, 2019). In stimulating the recovery of health professions’ education and the organisations that provide it, leaders will need to pay attention to ensuring the conditions for healing, regeneration and thriving are present, so that people (faculty and students) feel safe to return to campuses and a more ‘normal’ way of working.

IV. PREPARING FOR A ‘NEW NORMAL’

A. Planning and Implementing Change

As countries, organisations and individuals start to look forward and prepare for mass returns to campus, leaders will need to support students and faculty for a ‘new normal’. This requires managing expectations as well as physical and psychological safety as discussed above. Management is all about maintaining stability and order (as Drucker (2007) says: ‘doing the thing right’) therefore, in addition to choosing appropriate leadership approaches, leaders will need to utilise a range of management tools to help plan how universities and their research, education programmes and other activities will function.

B. Risk Assessment

In an ideal world, all changes would be able to be planned for and there would be no surprises. However, successful organisations (and individuals) also plan for unforeseen circumstances to stay resilient and help mitigate risk. There are a few ways of assessing risks, with one of the most widely used being a ‘risk matrix’ (Ni et al., 2010). This is used during risk assessment to define the level of risk by considering the category of probability or likelihood against the category of consequence severity. This simple tool helps to increase the visibility of risks and assist management decision making. At university level as well as departmental and programme levels, a risk analysis should be carried out and updated regularly. In stable times, risk analysis helps the organisation keep aware of external and internal risk factors and put plans in place, but during the pandemic it is essential.

C. Managing Change

A widely used tool to lead, accelerate and manage change is Kotter’s (2007) eight-stage process (Refer to Appendix D).

The pandemic itself provided a sense of urgency as universities and teachers scrambled to respond, and leaders needed a good understanding of organisational resources, the external environment, and educational responses worldwide to develop meaningful and realistic strategies (Schwartzstein et al., 2008). The fluidity and volatility of the pandemic situation early on made any progress along Kotter’s steps difficult to see at either individual or institutional level. Whilst it can feel very unsettling to have to return to an earlier Step, after moving a few steps forward, it is often necessary to do so and Kotter’s model acknowledges that change is iterative, not linear. Kotter’s and similar models are very useful both for planning the changes needed as well as offering a framework for analysis of where change efforts are faltering or failing. A formal communications strategy is essential which provides consistent messages, opportunities for questions to be answered for all key stakeholders and celebrates ‘quick visible wins’, such as learners returning to their studies or a successfully run online assessment or graduation ceremony.

D. Focus on Outcomes

Across the world, universities (many of which had never provided online learning or assessment) suddenly had to decide how (or whether) they would (or could) provide educational opportunities for their students. Cameron and Green (2019) suggest that leaders responding to or stimulating change need to balance their efforts across three dimensions of any change: outcomes, interests, and emotions. In terms of ‘outcomes’, they stress that clear outcomes (deliverables) must be developed and implemented. Outcomes (goals, targets or objectives) need to be SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time bound). In times of immediate crisis, some goals will need to be very short-term (e.g. ‘ensure all faculty are able and prepared to work from home by the end of next week’), whereas strategically, senior leaders have the responsibility to keep the longer terms outcomes in mind, e.g. ‘ensure that the university remains financially viable’. In terms of ‘emotions’, Cameron and Green (2019) suggest that the role of the leader is to enable people and the culture to adapt to the change and leaders also need to pay attention to (what may be competing) interests, here they need to mobilize their influence, authority and power to enact the change.

E. Planning and Implementation

McKimm and Jones (2018) suggest using project management techniques for operational planning and implementation. During the pandemic, plans will need to be devised and aligned in a range of areas (learning and teaching, student and faculty wellbeing, research, estates, finance etc.) and at many levels: whole university, department, and programme.

A project management approach sees activities as temporary, non-routine, acknowledging uncertainty and with a defined end point. Techniques taking a ‘linear’ view of change such as Lewin’s ‘freeze/unfreeze’ model (Cummings et al., 2016; Lewin, 1951) can be useful in framing the response into simple terms rather than getting bogged down in complexity. These look at the change process as comprising three steps: current state (how the university, schools and programmes ran pre-pandemic) – transitional state (how the university runs during the pandemic) – desired state (how might everything run after the pandemic, in the ‘new normal’). Once the broad elements and strategy have been agreed, then the detailed planning and implementation stages begin.

F. Sustaining Change

1) Recognising the dynamism of change: While crisis can bring about opportunities for real change, realistically there will be challenges sustaining the change. Buchanan et al. (2005) suggests organisational sustainability is contextual and dependent of various factors, including changes in market demands, financial viability, or political decisions. The drivers of sustainability will also differ based on organisational levels for example whether at the individual, managerial or leadership role. Given the uncertainties that leaders will face, an important step in sustaining change with positive outcomes would be an awareness that change, and sustainability is not static but is instead dynamic, requiring an improvement trajectory over time. This concept can also be described as dynamic stability: a process of continual, small, and possibly innovative changes that involve the modification or enhancement existing practices and business models (Hodges & Gill, 2014). When translated into practice, sustaining change requires as much attention from leaders as when developing and implementing change.

2) Supporting individuals at multiple levels: As sustainability of change is also dependent at the individual level, leaders should strongly promote and support initiatives that promote both individual professional and personal development. In the context of HPE, staff support is often interpreted as faculty development activities and more often is the form of workshops or, more recently, webinars. It is important for institutions to broaden the support activities to include non-faculty staff, provide activities other than workshops and implement initiatives for wellness and mental health wellbeing at the workplace. Another example of staff supports activities that has gained traction during this crisis are global community of practices. Given the similar challenges faced, global community of practices offer an opportunity to share strategies of mutual interest and benefit and build networks of educators across socio-cultural contexts (Thampy et al., 2020). As health professions’ leaders and educational organisations brace for the financial impact of the crisis, the case to reduce funding for staff support and investment in people maybe put forward. Leaders need to reflect and balance the impact reducing operating costs with enhancing the skills of staff to embrace, work with and sustain change.

3) Exchanging and co-creating global solutions: Sustaining change requires a vision for a new way of leadership and ways of working (McKimm & McLean, 2020). The recent COVID-19 crisis has highlighted that solutions to manage and sustain positive outcomes may not come from familiar local sources or authorities. The crisis also challenged the previously held assumptions of standards and readiness of healthcare systems and governance of it in some countries, suggesting much can be learned from successful approaches taken across the globe. Leaders in HPE should work collaboratively to acknowledge that solutions can come from across boundaries and draw from it lessons and guidelines for a global approach in the training of health professionals.

V. CONCLUSION

Although this paper provides a roadmap and suggested approaches for HPE leaders and followers alike to reflect on as they work through various waves of the pandemic, it is critical for leaders to be flexible and adaptive and adopt an emotionally intelligent and person-centred approach. Psychological safety is integral for professionals at all levels to successfully accomplish individual and institutional goals during challenging circumstances, along with leaders who provide stability and vision. What has become abundantly clear during the pandemic is that health professions’ educators from around the world have common as well as unique challenges and are increasingly seeking a diverse, multicultural global community of practice, sharing best practices and seeking to understand other cultural, regional and national educational context. These insights emphasise that health professions educators, regardless of their geographical location, cannot succeed in their leadership roles without a culturally sensitive, competent and grounded approach. No longer can experts from one group of countries impose their best practices on another region of the world without opening themselves to learning from other cultures and contexts.

Notes on Contributors

Judy McKimm conceptualised the idea for the article, wrote specific sections, and reviewed and edited the full article prior to submission.

Subha Ramani helped design the structure for this perspective, wrote content sections, edited, read and approved the final manuscript.

Vishna Devi Nadarajah helped design the structure for this perspective, wrote content sections, edited, read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

No ethics approval was required as this is an opinion piece supported by a literature review and does not relate to primary research.

Funding

No funding sources are associated with this paper.

Declaration of Interest

I confirm that the manuscript is original work of authors which has not been previously published or under review with another journal.

I confirm that all research meets the legal and ethical guidelines.

I confirm that I have stated all possible conflicts of interest in my manuscript and explicitly stated even if there is no conflict of interest.

I am not using third-party material that requires formal permission.

References

Ashokka, B., Ong, S. Y., Tay, K. H., Loh, N. H. W., Gee, C. F., & Samarasekera, D. D. (2020). Coordinated responses of academic medical centres to pandemics: Sustaining medical education during COVID-19. Medical Teacher, 42(7), 762–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1757634

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

Barrow, M., McKimm, J., & Gasquoine, S. (2011). The policy and the practice: early-career doctors and nurses as leaders and followers in the delivery of health care. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9239-2

Barrow, M., McKimm, J., Gasquoine, S., & Rowe, D. (2014). Collaborating in healthcare delivery: Exploring conceptual differences at the “bedside.” Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.955911

Boyatzis, R. E. (2009). Competencies as a behavioral approach to emotional intelligence. Journal of Management Development, 28(9), 749–770. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710910987647

Buchanan, D., Ketley, D., Gollop, R., Jones, J. L., Lamont, S. S., Neath, A., & Whitby, E. (2005). No going back: A review of the literature on sustaining strategic change. International Journal of Management Review, 7 (3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x

Cameron, E., & Green, M. (2019). Making sense of change management: A complete guide to the models, tools, and techniques of organizational change. Kogan Page Publishers.

Cardiff, S., McCormack, B., & McCance, T. (2018). Person-centred leadership: A relational approach to leadership derived through action research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(15–16), 3056–3069. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14492

Cummings, S., Bridgman, T., & Brown, K. G. (2016). Unfreezing change as three steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s legacy for change management. Human Relations, 69(1), 33-60.

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance (Vol. 234), Scribner. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12198

Dweck, C. (2016). What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harvard Business Review, 13, 213-226.

Goleman, D. (1998). The emotionally competent leader. The Healthcare Forum Journal, 41(2), 36-38.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2001). Primal leadership: The hidden driver of great performance. Harvard Business Review, 79(11), 42-53.

Heifetz, R. A., Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Press.

Hodges, J., & Gill, R. (2014). Sustaining change in organizations (1st ed.). SAGE Publications.

Hollander, E. P. (2012). Inclusive leadership: The essential leader-follower relationship (Applied Psychology Series) (1st ed.). Routledge.

Hutchins, G., & Storm, L. (2019). Regenerative Leadership: The DNA of life-affirming 21st century organizations. Wordzworth Publishing.

Kanter, R. M. (2020). Leading your team past the peak of a crisis. Harvard Business Review

Kotter, J. (2007). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, 86, 97-103.

Lazarus, G., Mangkuliguna, G., & Findyartini, A. (2020). Medical students in Indonesia: An invaluable living gemstone during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 32(3), 237–241. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2020.165

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers (D. Cartwright, Ed.). Harpers.

Liao, Y., & Thomas, D. C. (2020). Conceptualizing Cultural Intelligence. In Cultural Intelligence in the World of Work (pp. 17-30). Springer.

McKimm, J., & Jones, P. K. (2018). Twelve tips for applying change models to curriculum design, development and delivery. Medical Teacher, 40(5), 520-526.

McKimm, J., & McLean, M. (2020). Rethinking health professions’ education leadership: Developing ‘eco-ethical’leaders for a more sustainable world and future. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 855-860.

McKimm, J., & O’Sullivan, H. (2016). When I say … leadership. Medical Education, 50(9), 896–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13119

Nadarajah, V. D., Er, H. M., & Lilley, P. (2020). Turning around a medical education conference: Ottawa 2020 in the time of COVID‐19. Medical Education, 54(8), 760–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14197

Ni, H., Chen, A., & Chen, N. (2010). Some extensions on risk matrix approach. Safety Science, 48(10), 1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2010.04.005

Paixão, G., Mills, C., McKimm, J., Hassanien, M. A., & Al-Hayani, A. A. (2020). Leadership in a crisis: Doing things differently, doing different things. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 81(11), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2020.0611

Randall, L. M., & Coakley, L. A. (2007). Applying adaptive leadership to successful change initiatives in academia. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28(4), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730710752201

Schwartzstein, R. M., Huang, G. C., & Coughlin, C. M. (2008). Development and implementation of a comprehensive strategic plan for medical education at an academic medical center. Academic Medicine, 83(6), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181722c7c

Scouller, J. (2011). The three levels of leadership: How to develop your leadership presence, knowhow, and skill. Management Books 2000.

Sinek, S. (2014). Leaders eat last: Why some teams pull together and others don’t. Penguin.

Sosik, J. J., Jung, D., & Dinger, S. L. (2009). Values in authentic action. Group & Organization Management, 34(4), 395–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601108329212

Swanwick, T., & McKimm, J. (2017). ABC of clinical leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

Thampy, H. K., Ramani, S., McKimm, J., & Nadarajah, V. D. (2020). Virtual speed mentoring in challenging times. The Clinical Teacher, 17(4), 430–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13216

Till, A., Dutta, N., & McKimm, J. (2016). Vertical leadership in highly complex and unpredictable health systems. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 77(8), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2016.77.8.471

Uhl-Bien, M., & Carsten, M. (2018). Reversing the lens in leadership: Positioning followership in the leadership construct. In Leadership now: Reflections on the legacy of Boas Shamir. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Velarde, J. M., Ghani, M. F., Adams, D., & Cheah, J.-H. (2020). Towards a healthy school climate: The mediating effect of transformational leadership on cultural intelligence and organisational health. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220937311

Worley, C. G., & Jules, C. (2020). COVID-19’s uncomfortable revelations about agile and sustainable organizations in a VUCA world. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 56(3), 279–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320936263

*Judy McKimm

Swansea University Medical School,

Swansea University

Swansea, UK, SA1 8PP

Email: j.mckimm@swansea.ac.uk

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.