Simulation instructional design features with differences in clinical outcomes: A narrative review

Submitted: 18 November 2024

Accepted: 14 May 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 5-25

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/RA3572

Matthew Jian Wen Low1, Han Ting Jillian Yeo2, Dujeepa D. Samarasekera2, Gene Wai Han Chan1 & Lee Shuh Shing2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 2Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Effective and actionable instructional design features improve return on investment in Technology enhanced simulation (TES). Previous reviews on instructional design features for TES that improve clinical outcomes covered studies up to 2011, but updated, consolidated guidance has been lacking since then. This review aims to provide such updated guidance to inform educators and researchers.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted on instructional design features in TES in medical education. Original research articles published between 2011 to 2022 that examined outcomes at Kirkpatrick level three and above were included.

Results: A total of 30,491 citations were identified. After screening, 31 articles were included in this review. Most instructional design features had a limited evidence base with only one to four studies each, except 11 studies for simulator modality. Improved outcomes were observed with error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training. Mixed results were seen with different simulation modalities, isolated components of mastery learning, just-in-time training, and part versus whole task practice.

Conclusion: There is limited evidence for instructional design features in TES that improve clinical outcomes. Within these limits, error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training appear beneficial. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness and generalisability of these features.

Keywords: Simulation, Instructional Design, Clinical Outcomes, Review

Practice Highlights

- This review pinpoints additional beneficial instructional design features emerging since 2011.

- These include error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training.

- Further evidence from diverse task and learner contexts is needed to establish generalisability.

- Current evidence continues to suggest no clear superiority of one simulator modality over the other.

I. INTRODUCTION

Technology enhanced simulation (TES) training has been shown to be effective for skills, behaviour, and patient-related outcomes (Cook et al., 2011; McGaghie et al., 2011). Instructional design features in simulation refer to variations in aspects of simulation design that act as active ingredients or mechanisms that make simulation effective, with examples including distributed practice, mastery learning, and range of difficulty (Cook, Hamstra, et al., 2013). Effective instructional design features for TES are actionable for educators because they offer specific, implementable guidance, and an area of research interest (Issenberg et al., 2005; Nestel et al., 2011; Schaefer et al., 2011), including those that lead to transfer to authentic clinical practice (Frerejean et al., 2023; Zendejas et al., 2013).

While it is acknowledged that conducting a study to establish a causal relationship between an educational intervention and subsequent patient and clinical process outcomes is challenging (Cook & West, 2013), such studies become particularly valuable when appropriately executed (Dauphinee, 2012). These studies represent the apex of impact in Kirkpatrick’s model for program evaluation (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006), holding the highest clinical significance and representing the ultimate goal of health professions education which is to enhance patient outcomes by equipping the healthcare workforce to effectively address societal needs (Carraccio et al., 2016). Additionally, the examination of clinical outcomes, when coupled with a consideration of costs, contributes to the informed allocation of limited institutional resources to such educational approaches (Lin et al., 2018).

In prior reviews of TES including studies up to 2011, the vast majority of studies examined outcomes at the levels of reaction and learning demonstrated in written or simulation tests, with only a small body of evidence studying outcomes in workplace contexts (Cook, Hamstra, et al., 2013; Nestel et al., 2011; Zendejas et al., 2013) suggesting that clinical variation, multiple learning strategies, and increased time learning are beneficial variations. This limited evidence base for transfer to workplace contexts hinders educators in fully harnessing the potential of TES to improve patient and system outcomes and obtain the best returns on investments in simulation technology. Given the time interval since these prior reviews, further evidence would have accrued regarding these and other instructional design features.

Given the time elapsed since the last comprehensive review of TES instructional design features, the scarcity of prior studies on clinical outcomes, and the importance of these outcomes, we conducted this narrative review. The objective was to provide an updated understanding of the instructional design features in TES that are associated with enhanced clinical outcomes, thereby addressing a significant gap in the existing literature, to guide educators seeking to optimise instructional design, and provide researchers with an overview of the current state of this literature and guide further inquiry.

II. METHODS

We conducted a narrative review based on the framework proposed by Ferrari (2015). We searched MEDLINE, ERIC, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science databases for articles published from 2012 January 01 to 2022 December 06. We translated abstracts and articles not in English into English using Google Translate.

The following search terms were used: (Medical education) AND (Simulation OR Cadaver OR Simulator OR Augmented Reality OR Virtual reality OR Mixed reality).

Studies were included if they were original research articles examining instructional design variations in TES with at least one outcome at Kirkpatrick levels three or above, as described and utilised by the Best Evidence Medical Education Collaboration (Steinert et al., 2006). We included a broad range of TES modalities, such as computer based virtual reality simulators, high fidelity and static mannequins, plastic models, live animals, inert animal products, and human cadavers as stipulated in the review by Cook et al. (2011). We included augmented reality and mixed reality as they satisfied the prior definition of “materials and devices created or adapted to solve practical problems” in simulation established by Cook et al (2011). Studies where TES was utilised together with human patient actors were included. We included studies with observational, experimental, and qualitative designs.

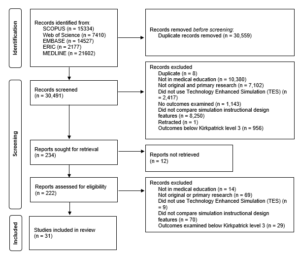

Studies were excluded if they involved only human patient actors as the sole modality of simulation, used simulation outside of health professions education, used simulation for noneducation purposes such as procedural planning or patient education, or only compared simulation with no simulation. We excluded studies involving only nurses given that there are recent and ongoing reviews addressing a similar research question (El Hussein & Cuncannon, 2022; Jackson et al., 2022), but included interprofessional studies. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review and selection process.

Three researchers (MJWL, SSL, JHTY) independently read the full text of articles that met the inclusion criteria and extracted study information including geographical origin, specialty context, type of skill studied, level of the learner, simulation modalities used, instructional design variations studied, and outcomes categorised into the highest Kirkpatrick level studied. Any differences were resolved by a discussion among researchers to arrive at a consensus.

III. RESULTS

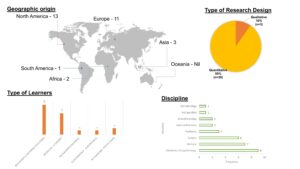

A total of 30,491 records were identified using the search strategy. From these, 31 eligible studies were identified and reviewed (Figure 1 and Table 1). Figure 2 summarises basic information on these studies. The number of studies from each geographic region were 13 from North America (42%), 11 from Europe (35%), three from Asia (10%), two from Africa (6%), and one from South America (3%). One study did not clearly state the countries involved.

28 out of 31 (90%) of the studies adopted a quantitative research design focusing on experimental design. Most simulation interventions were conducted among residents/fellows/interns, followed by medical students.

The results reported in the studies are divided into two groups:

- Evidence suggests improved outcomes

- Evidence shows mixed results

A. Improved Outcomes

Error management training was associated with improved obstetric ultrasound skills compared to error avoidance training in novices (Dyre et al., 2017). Frequent brief on-site simulation, at 40 minutes a month and three minutes a week, was associated with reduced infant mortality compared to a single day course (Mduma et al., 2015). Integrating non-technical skills (NTS) training into a colonoscopy skills curriculum with TES, without increasing time spent teaching, improved observed performance during colonoscopies on real patients, although it was unclear whether this was driven by changes in observed NTS only, or both NTS and technical skills (Walsh et al., 2020).

One qualitative study found that in situ training had greater organisational impact and provided more information for practical organisational changes (Sørensen et al., 2015). One qualitative study found that multi-professional training led to improved communication, leadership, and clinical management of post-partum haemorrhage (Egenberg et al., 2017).

1. Dyad Training

In one study of obstetric ultrasound skills (Tolsgaard et al., 2015) a larger proportion of the dyad training group (71%) scored above the criterion referenced pass fail level than the individual training group (30%) on the objective structured assessment of ultrasound skills, though the difference in mean scores on did not reach statistical significance. Other benefits included increased efficiency from greater faculty to learner ratios.

2. Complex Bundles

Three studies found improvements with complex bundles comprising multiple instructional design variations.

Medical students performed the correct sequence of steps for endotracheal intubation measured by a checklist more often when practice with a mannequin was augmented by a 10-question pre-test, hand held tablets containing scenarios, checklists, and learning algorithms, 24-hour access to the simulation laboratory, and remote review of practice recordings with feedback from teachers via email (Mankute et al., 2022).

Residents had improved observed performance in laparoscopic salpingectomy with lectures, videos, reading materials, a box trainer with pre-set proficiency benchmarks, a VR simulator for technical skills, and non-technical skills training with scripted confederates, compared to a conventional curriculum including simulation with minimal further description (Shore et al., 2016).

In one qualitative study of obstetric residents, there was improved transfer of communication and team work skills and situational awareness with simulation aligned to multiple principles including authenticity, psychological fidelity, engineering fidelity, Paivio’s dual coding, feedback, variability, and increasing complexity (de Melo et al., 2018).

B. Mixed Results

1. Simulation Modality

Eleven studies examined whether outcomes differed when different simulation modalities were used. Examples include higher versus lower technological complexity in a physical simulator (DeStephano et al., 2015; Sharara-Chami et al., 2014), cadaveric versus synthetic models (Lal et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2018; Tchorz et al., 2015), virtual reality (VR) versus physical simulators (Daly et al., 2013; Gomez et al., 2015; Orzech et al., 2012; O’Sullivan et al., 2014), and a computer based versus physical simulated operating room for student orientation (Patel et al., 2012).

Overall, there no clear pattern of superiority of a particular type of simulator. Most studies found no difference, with three exceptions: Gomez et al (2012) found that VR alone, and VR with physical simulator, led to superior performance in observed colonoscopic skills in real patients, compared to physical simulator alone; Chunharas et al (2013) found that adding practice on fellow students on top of mannequin practice improved observed performance in subcutaneous and intramuscular injection skills; Patel et al (2012) found that using a physical simulated operating room was superior to an online computer based operating room for training novice medical students in appropriate behaviour in the operating room.

To view Table 1 click here.

Abbreviations. ACS/APDS: American College of Surgeons / Association of Program Directors in Surgery; EAT: Error avoidance training; EMT: Error management training; GAGES-C: Global Assessment of Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Skills-Colonoscopy; GOALS: Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills; ISS: In situ simulation; JAG DOPS: Joint Advisory Group Direct Observation of Procedural Skills; JIT: Just in time; OSA-LS: objective structured assessment of laparoscopic salpingectomy; NTS: Non-technical skills. OSAUS: objective structured assessment of ultrasound; OSS: Off-site simulation; PGY: Post graduate year; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; VR: Virtual reality.

Kirkpatrick levels. 1: Reaction e.g. participants’ views on learning experience; 2a: Learning – Change in attitudes; 2b: Learning – Modification of knowledge or skills; 3: Behaviour – Change in behaviours; 4a: Results – Change in the system/organisational practice; 4b: Results – Change in patient outcomes.

Table 1. List of included studies and skills, instructional design variations and outcomes examined

Figure 1. Flow of studies through identification process

Figure 2. Summary of geographical origin, type of research, type of learners and disciplines studied

2. Components of Mastery Learning

Four studies examined components of mastery learning, such as progressive task difficulty and proficiency-based progression. Progressive task difficulty for TES was associated with improved rater observed colonoscopic performance on real patients (Grover et al., 2017), while the evidence was mixed for proficiency-based progression for TES, with studies finding reduced epidural failure rates (Srinivasan et al., 2018) and fewer adverse events in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (De Win et al., 2016), while another found no difference in operative performance for bowel anastomosis in real patients (Naples et al., 2022).

3. Part Versus Whole Task

Two studies compared part versus whole task training. Both found no difference, in rater observed performance in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (Hernández-Irizarry et al., 2016), and intraoperative camera navigation skills (Nilsson et al., 2017), though randomised part task training led to faster skills mastery with greater cost effectiveness compared to whole task training.

4. Increased Time Spent in Simulation Training

Two studies examined amount of time spent in simulation training. One study showed reduced incidence of malpractice claims (Schaffer et al., 2021), while another study found no difference in successful deep biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (Liao et al., 2013).

5. Just in Time (JIT) Training

Overall, there was mostly no benefit seen with JIT training with TES, across three studies. One study examined the addition of JIT video after prior TES (Todsen et al., 2013), and one study compared JIT practice alone, JIT practice with feedback from this practice, and feedback alone derived from baseline testing (Kroft et al., 2017). JIT and just-in-place physical simulator training did not improve first pass lumbar puncture success, but improved mean number of attempts and process measures such as early stylet removal (Kessler et al., 2015).

IV. DISCUSSION

We sought to provide an updated synthesis on effective instructional design features in simulation in medical education, focusing on those that produce higher level outcomes at Kirkpatrick levels three and above. A prior review searching until 2011 identified only 18 studies that examined outcomes at Kirkpatrick level three and above, out of their pool of 10,297 studies. Our review reveals a notable rise in the number of studies over the past ten years, exploring instructional design and clinical outcomes. In the discussion that follows, we synthesise the findings with existing literature and theory to extract valuable insights for medical educators.

A. Implications for Current Practice

This review underscores the necessity of directing resources towards effective instructional design features, emphasising that these need not be strictly tied to specific simulator types, as advocated by Norman. Despite the ongoing evolution and incorporation of an expanding array of TES modalities, including Virtual Reality (VR) in this review, we observed mixed results concerning simulation modality as an instructional design variation. Upon closer examination of interventions outlined in studies comparing simulation modalities, it becomes evident that confounding factors may arise due to variations in the application of training to proficiency criteria (a characteristic of mastery learning) or differences in the quality of measurement.

In the study conducted by Gomez et al (2015), training to proficiency criteria was incorporated in study arms demonstrating benefit (VR and VR plus physical simulator) and not incorporated in the remaining arm (physical simulator alone). Similarly, in the study by Orzech et al (2012) where training until proficiency criteria were reached was a shared feature of both arms, no significant difference between groups was observed. It remains unclear whether observed differences were attributable to the application of training until proficiency criteria were met or to the varied simulation modalities.

Chunharas et al (2013) and Patel et al (2012) also noted outcome differences when comparing different simulation modalities. However, the robustness of these findings is constrained using a checklist observation scale developed for individual studies with minimal validity evidence. Clinical and task variations, recognised as beneficial in prior reviews (Zendejas et al., 2013), may elucidate the advantages identified by Chunharas et al and the VR plus physical simulator arm in the study by Gomez et al.

Components of mastery learning appear mostly effective, although isolated implementation of a component without the whole may erode effectiveness. The inconsistent evidence for effectiveness of components of mastery learning in this review is surprising, given prior evidence for the effectiveness of mastery learning for translational outcomes (Griswold-Theodorson et al., 2015). The difference may lie in piecemeal rather than holistic implementation of mastery learning as a complex intervention, with seven complementary components working together (McGaghie, 2015).

Another difference is that our review only included studies comparing different TES interventions, while the review by Griswold-Theodorson et al included studies that compared mastery learning with a wider range of comparators, including no TES. Notably, a separate systematic review and meta-analysis of mastery learning found only three studies from 1984-2010 comparing mastery learning to other TES interventions for patient outcomes, with no statistically significant benefit overall and substantial heterogeneity (Cook, Brydges, et al., 2013).

Methodological issues may be another contributory factor. Naples et al (2022) postulate in their study the reasons for the lack of observed difference, including a long duration between intervention and outcome assessment, which was longer in the intervention group than the control group, biasing towards the null, and surprisingly high baseline performance with an insufficiently sensitive rater observation tool. This study had only nine participants, limiting statistical power. These represent important methodological considerations for researchers designing educational intervention studies.

The effectiveness of increased time spent in simulation training is associated with incorporation of learning conversations. Discrepancies in outcomes between the two studies assessing the impact of time spent in simulation training may be attributed to the presence of debriefing in the study conducted by Schaffer et al (2021), as opposed to un-coached practice without feedback in the study by Liao et al (2013). It is crucial to note that the advantages derived from extended training periods are not solely attributed to prolonged duration but are also influenced by the integration of learning conversations. These conversations encompass both debriefing and feedback (Tavares et al., 2020), both of which have demonstrated efficacy, as supported by existing research (Cheng et al., 2014; Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

In a systematic review by Hatala and colleagues (Hatala et al., 2014), feedback emerged as moderately effective for procedural skills simulation training. Notably, feedback from multiple sources, including instructors, proved more effective than feedback from a single source.

Distributed practice is preferred over blocked practice for TES. Frequent brief simulation (Mduma et al., 2015) essentially describes distributed rather than blocked practice. The increased effectiveness seen with distributed practice here is consistent with existing literature within (Cecilio-Fernandes et al., 2023) and outside (Dunlosky et al., 2013) of health professions education.

Dyad training is notable for being efficient with similar or better outcomes, and is consistent with existing literature on motor skills learning (Wulf et al., 2010). The optimal group size has not been clearly determined, beyond single versus dyad, and would be a productive avenue of inquiry for evidence-based determination of learner to faculty ratios, accounting for contextual factors such as task complexity and stage of learner’s development.

In situ simulation may be beneficial in generating participant insights that feed into systems-based improvements through quality improvement mechanisms (Calhoun et al., 2024; Nickson et al., 2021). This combines multiple mechanisms by which TES can produce meaningful impact: through changing individual learner behaviour and changing systems processes.

Error management training appears beneficial for transfer outcomes in novices. This is congruent with literature outside of medical education (Keith & Frese, 2008). The limited evidence base within medical education makes this ripe for further study across task and learner types.

In summary, the features mentioned above are predominantly drawn from previous studies, primarily conducted at Kirkpatrick level two. This review contributes by offering an updated synthesis of evidence, outlining the extent to which this evidence can be extrapolated to higher Kirkpatrick levels, and highlighting features that were previously unexplored at clinical process and outcome levels. Collectively, evidence spanning these levels serves as a guide for those designing TES with the goal of achieving educational and clinical impact.

B. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Studies that examine Kirkpatrick levels three and above continue to constitute a relatively small fraction of the overall research landscape. Furthermore, this limited body of research is dispersed among various instructional design features, with only a small number of studies investigating each specific feature. Consequently, drawing definitive conclusions about effectiveness becomes challenging, representing a primary constraint of this review. Despite these limitations, we have tried to extract valuable insights for health professions educators by synthesising the findings with existing literature and theory.

The limited evidence bases for most individual instructional design features, especially those demonstrating benefits at Kirkpatrick levels three and four, limits the strength of conclusions that can be drawn about their effectiveness. Further studies replicating these results would strengthen the argument that a particular instructional design feature is able to achieve clinical impact. The evidence base is also limited in the variety of task and learner contexts studied for each individual instructional design feature. Determining the generalisability of these findings requires further research applying these features across diverse TES contexts with different skills and learner groups. Future research should also continue to explore novel and promising instructional design features, such as hybrid simulations where mannequins are overlayed with animal tissue or gel-based phantoms (Balakrishnan et al., 2025).

V. CONCLUSION

There is limited evidence for instructional design features in TES that translate to improved clinical outcomes. Within these limits, error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training appear beneficial. Given the limited evidence base for these individual features, definitive determination of effectiveness and generalisability requires further research applying promising target features across different task and learner contexts.

Notes on Contributors

Matthew Low is an emergency physician at National University Hospital, Singapore, and adjunct assistant professor at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Jillian Yeo is a medical educationalist at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Dujeepa Samarasekera is senior director at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Gene Chan is an emergency physician at National University Hospital, Singapore, and adjunct assistant professor at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Shuh Shing Lee is a medical educationalist at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Matthew Low, Jillian Yeo and Shuh Shing Lee conceived of the work, collected and analysed data, and drafted the work. Gene Chan and Dujeepa Samarasekera conceived of the work and reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. All contributors gave final approval of the version to be published and are agreeable to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not applicable as this is a review paper.

Funding

There was no funding for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

Balakrishnan, A., Law, L. S.-C., Areti, A., Burckett-St Laurent, D., Zuercher, R. O., Chin, K.-J., & Ramlogan, R. (2025). Educational outcomes of simulation-based training in regional anaesthesia: A scoping review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 134(2), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.07.037

Calhoun, A. W., Cook, D. A., Genova, G., Motamedi, S. M. K., Waseem, M., Carey, R., Hanson, A., Chan, J. C. K., Camacho, C., Harwayne-Gidansky, I., Walsh, B., White, M., Geis, G., Monachino, A. M., Maa, T., Posner, G., Li, D. L., & Lin, Y. (2024). Educational and patient care impacts of in situ simulation in healthcare: A systematic review. Simulation in Healthcare, 19(1S), S23–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000773

Carraccio, C., Englander, R., Van Melle, E., Ten Cate, O., Lockyer, J., Chan, M.-K., Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., & International Competency-Based Medical Education Collaborators. (2016). Advancing competency-based medical education: A charter for clinician-educators. Academic Medicine, 91(5), 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001048

Cecilio-Fernandes, D., Patel, R., & Sandars, J. (2023). Using insights from cognitive science for the teaching of clinical skills: AMEE Guide No. 155. Medical Teacher, 45(11), 1214–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2168528

Cheng, A., Eppich, W., Grant, V., Sherbino, J., Zendejas, B., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Debriefing for technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education, 48(7), 657–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12432

Chunharas, A., Hetrakul, P., Boonyobol, R., Udomkitti, T., Tassanapitikul, T., & Wattanasirichaigoon, D. (2013). Medical students themselves as surrogate patients increased satisfaction, confidence, and performance in practicing injection skill. Medical Teacher, 35(4), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.746453

Cook, D. A., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Hamstra, S. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Mastery learning for health professionals using technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1178–1186. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a365d

Cook, D. A., Hamstra, S. J., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-based education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Teacher, 35(1), e867-898. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.714886

Cook, D. A., Hatala, R., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hamstra, S. J. (2011). Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 306(9), 978–988. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1234

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2013). Perspective: Reconsidering the focus on “outcomes research” in medical education: A cautionary note. Academic Medicine, 88(2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78

Daly, M. K., Gonzalez, E., Siracuse-Lee, D., & Legutko, P. A. (2013). Efficacy of surgical simulator training versus traditional wet-lab training on operating room performance of ophthalmology residents during the capsulorhexis in cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 39(11), 1734–1741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.05.044

Dauphinee, W. D. (2012). Educators must consider patient outcomes when assessing the impact of clinical training. Medical Education, 46(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04144.x

de Melo, B. C. P., Rodrigues Falbo, A., Sorensen, J. L., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & van der Vleuten, C. (2018). Self-perceived long-term transfer of learning after postpartum haemorrhage simulation training. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 141(2), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12442

De Win, G., Van Bruwaene, S., Kulkarni, J., Van Calster, B., Aggarwal, R., Allen, C., Lissens, A., De Ridder, D., & Miserez, M. (2016). An evidence-based laparoscopic simulation curriculum shortens the clinical learning curve and reduces surgical adverse events. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 7, 357–370. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S102000

DeStephano, C. C., Chou, B., Patel, S., Slattery, R., & Hueppchen, N. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of birth simulation for medical students. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 213(1), 91.e1-91.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.024

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Dyre, L., Tabor, A., Ringsted, C., & Tolsgaard, M. G. (2017). Imperfect practice makes perfect: Error management training improves transfer of learning. Medical Education, 51(2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13208

Egenberg, S., Karlsen, B., Massay, D., Kimaro, H., & Bru, L. E. (2017). “No patient should die of PPH just for the lack of training!” Experiences from multi-professional simulation training on postpartum haemorrhage in northern Tanzania: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0957-5

El Hussein, M. T., & Cuncannon, A. (2022). Nursing students’ transfer of learning from simulated clinical experiences into clinical practice: A scoping review. Nurse Education Today, 116, 105449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105449

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Frerejean, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Condron, C., Strauch, U., & Eppich, W. (2023). Critical design choices in healthcare simulation education: A 4C/ID perspective on design that leads to transfer. Advances in Simulation (London, England), 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-023-00242-7

Gomez, P. P., Willis, R. E., & Van Sickle, K. (2015). Evaluation of two flexible colonoscopy simulators and transfer of skills into clinical practice. Journal of Surgical Education, 72(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.08.010

Griswold-Theodorson, S., Ponnuru, S., Dong, C., Szyld, D., Reed, T., & McGaghie, W. C. (2015). Beyond the simulation laboratory: A realist synthesis review of clinical outcomes of simulation-based mastery learning. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1553–1560. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000938

Grover, S. C., Scaffidi, M. A., Khan, R., Garg, A., Al-Mazroui, A., Alomani, T., Yu, J. J., Plener, I. S., Al-Awamy, M., Yong, E. L., Cino, M., Ravindran, N. C., Zasowski, M., Grantcharov, T. P., & Walsh, C. M. (2017). Progressive learning in endoscopy simulation training improves clinical performance: A blinded randomized trial. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 86(5), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1529

Hatala, R., Cook, D. A., Zendejas, B., Hamstra, S. J., & Brydges, R. (2014). Feedback for simulation-based procedural skills training: A meta-analysis and critical narrative synthesis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 19(2), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-013-9462-8

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hernández-Irizarry, R., Zendejas, B., Ali, S. M., & Farley, D. R. (2016). Optimizing training cost-effectiveness of simulation-based laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. American Journal of Surgery, 211(2), 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.027

Issenberg, S. B., McGaghie, W. C., Petrusa, E. R., Lee Gordon, D., & Scalese, R. J. (2005). Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher, 27(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046924

Jackson, M., McTier, L., Brooks, L. A., & Wynne, R. (2022). The impact of design elements on undergraduate nursing students’ educational outcomes in simulation education: Protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01926-3

Keith, N., & Frese, M. (2008). Effectiveness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.59

Kessler, D., Pusic, M., Chang, T. P., Fein, D. M., Grossman, D., Mehta, R., White, M., Jang, J., Whitfill, T., Auerbach, M., & INSPIRE LP investigators. (2015). Impact of just-in-time and just-in-place simulation on intern success with infant lumbar puncture. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1237-1246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014 -1911

Kirkpatrick, D., & Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kroft, J., Ordon, M., Po, L., Zwingerman, N., Waters, K., Lee, J. Y., & Pittini, R. (2017). Preoperative practice paired with instructor feedback may not improve obstetrics-gynaecology residents’ operative performance. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(2), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00238.1

Lal, B. K., Cambria, R., Moore, W., Mayorga-Carlin, M., Shutze, W., Stout, C. L., Broussard, H., Garrett, H. E., Nelson, W., Titus, J. M., Macdonald, S., Lake, R., & Sorkin, J. D. (2022). Evaluating the optimal training paradigm for transcarotid artery revascularization based on worldwide experience. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 75(2), 581-589.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.08.085

Liao, W.-C., Leung, J. W., Wang, H.-P., Chang, W.-H., Chu, C.-H., Lin, J.-T., Wilson, R. E., Lim, B. S., & Leung, F. W. (2013). Coached practice using ERCP mechanical simulator improves trainees’ ERCP performance: A randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy, 45(10), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1344224

Lin, Y., Cheng, A., Hecker, K., Grant, V., & Currie, G. R. (2018). Implementing economic evaluation in simulation-based medical education: Challenges and opportunities. Medical Education, 52(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13411

Mankute, A., Juozapaviciene, L., Stucinskas, J., Dambrauskas, Z., Dobozinskas, P., Sinz, E., Rodgers, D. L., Giedraitis, M., & Vaitkaitis, D. (2022). A novel algorithm-driven hybrid simulation learning method to improve acquisition of endotracheal intubation skills: A randomized controlled study. BMC Anaesthesiology, 22(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01557-6

McGaghie, W. C. (2015). Mastery learning: It is time for medical education to join the 21st century. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1438–1441. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000911

McGaghie, W. C., Issenberg, S. B., Cohen, E. R., Barsuk, J. H., & Wayne, D. B. (2011). Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 86(6), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

Mduma, E., Ersdal, H., Svensen, E., Kidanto, H., Auestad, B., & Perlman, J. (2015). Frequent brief on-site simulation training and reduction in 24-h neonatal mortality—An educational intervention study. Resuscitation, 93, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.019

Naples, R., French, J. C., Han, A. Y., Lipman, J. M., & Awad, M. M. (2022). The impact of simulation training on operative performance in general surgery: Lessons learned from a prospective randomized trial. Journal of Surgical Research, 270, 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.10.003

Nestel, D., Groom, J., Eikeland-Husebø, S., & O’Donnell, J. M. (2011). Simulation for learning and teaching procedural skills: The state of the science. Simulation in Healthcare, 6 Suppl, S10-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e318227ce96

Nickson, C. P., Petrosoniak, A., Barwick, S., & Brazil, V. (2021). Translational simulation: From description to action. Advances in Simulation (London, England), 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-021-00160-6

Nilsson, C., Sorensen, J. L., Konge, L., Westen, M., Stadeager, M., Ottesen, B., & Bjerrum, F. (2017). Simulation-based camera navigation training in laparoscopy—A randomized trial. Surgical Endoscopy, 31(5), 2131–2139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5210-5

Orzech, N., Palter, V. N., Reznick, R. K., Aggarwal, R., & Grantcharov, T. P. (2012). A comparison of 2 ex vivo training curricula for advanced laparoscopic skills: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 255(5), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824aca09

O’Sullivan, O., Iohom, G., O’Donnell, B. D., & Shorten, G. D. (2014). The effect of simulation-based training on initial performance of ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus blockade in a clinical setting—A pilot study. BMC Anaesthesiology, 14, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2253-14-110

Patel, V., Aggarwal, R., Osinibi, E., Taylor, D., Arora, S., & Darzi, A. (2012). Operating room introduction for the novice. American Journal of Surgery, 203(2), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.03.003

Schaefer, J. J., Vanderbilt, A. A., Cason, C. L., Bauman, E. B., Glavin, R. J., Lee, F. W., & Navedo, D. D. (2011). Literature review: Instructional design and pedagogy science in healthcare simulation. Simulation in Healthcare, 6 Suppl, S30-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e31822237b4

Schaffer, A. C., Babayan, A., Einbinder, J. S., Sato, L., & Gardner, R. (2021). Association of simulation training with rates of medical malpractice claims among obstetrician-gynaecologists. Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 138(2), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004464

Sharara-Chami, R., Taher, S., Kaddoum, R., Tamim, H., & Charafeddine, L. (2014). Simulation training in endotracheal intubation in a paediatric residency. Middle East Journal of Anaesthesiology, 22(5), 477–485.

Shore, E. M., Grantcharov, T. P., Husslein, H., Shirreff, L., Dedy, N. J., McDermott, C. D., & Lefebvre, G. G. (2016). Validating a standardized laparoscopy curriculum for gynaecology residents: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 215(2), 204.e1-204.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.037

Sørensen, J. L., Navne, L. E., Martin, H. M., Ottesen, B., Albrecthsen, C. K., Pedersen, B. W., Kjærgaard, H., & van der Vleuten, C. (2015). Clarifying the learning experiences of healthcare professionals with in situ and off-site simulation-based medical education: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 5(10), e008345. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008345

Srinivasan, K. K., Gallagher, A., O’Brien, N., Sudir, V., Barrett, N., O’Connor, R., Holt, F., Lee, P., O’Donnell, B., & Shorten, G. (2018). Proficiency-based progression training: An “end to end” model for decreasing error applied to achievement of effective epidural analgesia during labour: A randomised control study. BMJ Open, 8(10), e020099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020099

Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Centeno, A., Dolmans, D., Spencer, J., Gelula, M., & Prideaux, D. (2006). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Medical Teacher, 28(6), 497–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600902976

Tan, T. X., Buchanan, P., & Quattromani, E. (2018). Teaching residents chest tubes: Simulation task trainer or cadaver model? Emergency Medicine International, 2018, 9179042. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9179042

Tavares, W., Eppich, W., Cheng, A., Miller, S., Teunissen, P. W., Watling, C. J., & Sargeant, J. (2020). Learning conversations: An analysis of the theoretical roots and their manifestations of feedback and debriefing in medical education. Academic Medicine, 95(7), 1020–1025. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002932

Tchorz, J. P., Brandl, M., Ganter, P. A., Karygianni, L., Polydorou, O., Vach, K., Hellwig, E., & Altenburger, M. J. (2015). Pre-clinical endodontic training with artificial instead of extracted human teeth: Does the type of exercise have an influence on clinical endodontic outcomes? International Endodontic Journal, 48(9), 888–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12385

Todsen, T., Henriksen, M. V., Kromann, C. B., Konge, L., Eldrup, J., & Ringsted, C. (2013). Short- and long-term transfer of urethral catheterization skills from simulation training to performance on patients. BMC Medical Education, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-29

Tolsgaard, M. G., Madsen, M. E., Ringsted, C., Oxlund, B. S., Oldenburg, A., Sorensen, J. L., Ottesen, B., & Tabor, A. (2015). The effect of dyad versus individual simulation-based ultrasound training on skills transfer. Medical Education, 49(3), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12624

Walsh, C. M., Scaffidi, M. A., Khan, R., Arora, A., Gimpaya, N., Lin, P., Satchwell, J., Al-Mazroui, A., Zarghom, O., Sharma, S., Kamani, A., Genis, S., Kalaichandran, R., & Grover, S. C. (2020). Non-technical skills curriculum incorporating simulation-based training improves performance in colonoscopy among novice endoscopists: Randomized controlled trial. Digestive Endoscopy, 32(6), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.13623

Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Motor skill learning and performance: A review of influential factors. Medical Education, 44(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03421.x

Zendejas, B., Brydges, R., Wang, A. T., & Cook, D. A. (2013). Patient outcomes in simulation-based medical education: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(8), 1078–1089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2264-5

*Matthew Low

Emergency Medicine Department,

National University Hospital

9 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Level 4,

Singapore 119085

Email: mlow@nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.