Simulated patients’ experience of adopting telesimulation for history taking during a pandemic

Submitted: 16 July 2020

Accepted: 12 August 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 124-127

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/CS2344

Kirsty J Freeman, Weiren Wilson Xin & Claire Ann Canning

Office of Education, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

The Duke-NUS Medical School Simulated Patient programme is instrumental in the development of clinical and behavioural skills in the future medical workforce of Singapore. Starting with a group of 20 passionate individuals in 2007, the Simulated Patient programme currently engages over 100 individuals, of which 58% are Female, 42% are Male; with 46% over 50 years of age. Simulated Patients (SPs) are individuals who are trained to portray a real patient in order to simulate a set of symptoms or problems used for healthcare education, evaluation, and research (Lioce et al., 2020). The SPs are engaged across the curriculum and are specifically trained to provide realistic and convincing patient-centred encounters, as well as identify and give feedback on key elements of interpersonal and communication skills in face-to-face interactions for a unique educational experience.

Medical students at Duke-NUS engage with SPs from their first year, as they learn the fundamental skills of clinical practice (FOCP), the skill of history taking being one of the cornerstones of the programme. Keifenheim et al. (2015) define history taking as “a way of eliciting relevant personal, psychosocial and symptom information from a patient with the aim of obtaining information useful in formulating a diagnosis and providing medical care to the patient”. Several studies have reported on the impact of engaging SPs to teach history taking (Hulsman et al., 2009; Nestel & Kidd, 2003).

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the delivery of on-campus education, requiring medical educators to adapt teaching methods to reflect governmental and institutional restrictions. Whilst journals have been expedient in their ability to publish the experience of educators and students during the COVID-19 pandemic, the experience of other stakeholders are lacking. This paper will describe the experience of simulated patients in adopting telesimulation during a pandemic.

II. ADOPTING TELESIMULATION DURING A PANDEMIC

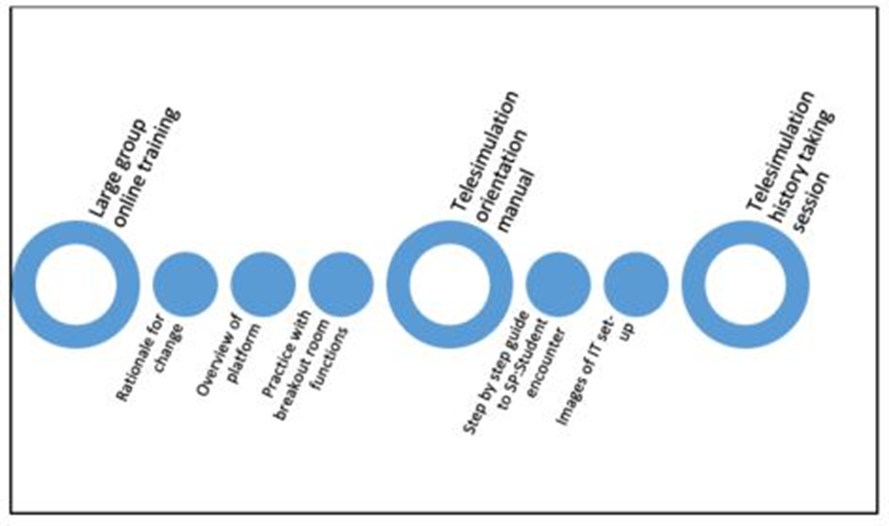

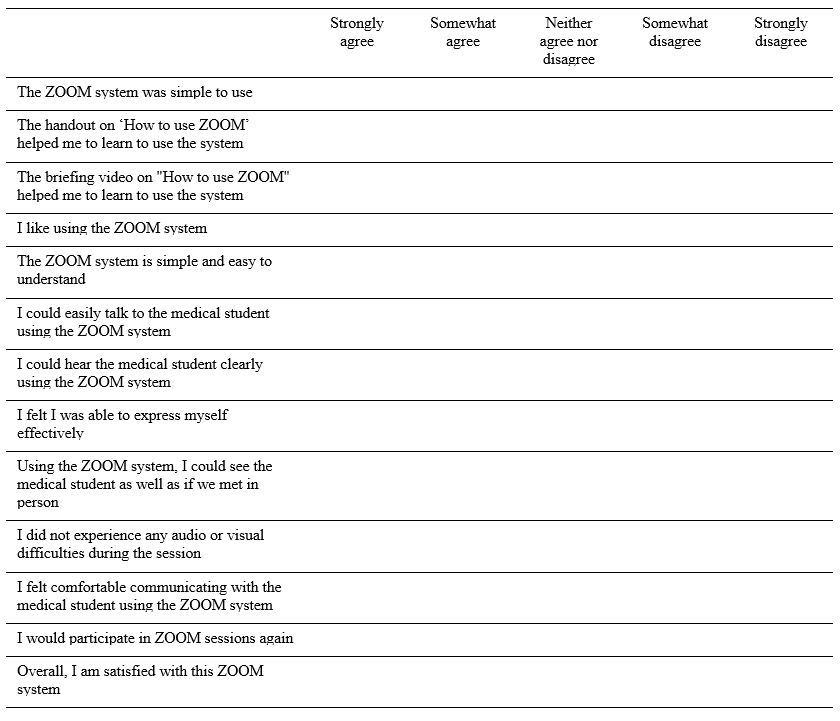

McCoy et al. (2017) define telesimulation as “a process by which telecommunication and simulation resources are utilised to provide education, training, and/or assessment to learners at an off-site location” (McCoy et al., 2017, p. 133). With staff, students and SPs in numerous off-site locations (their own homes), the telecommunication platform adopted for this experience was Zoom. The main reason behind this was it was the platform of choice by the institution when face-to-face teaching was shifted to e-learning, therefore staff and students were familiar with the functionality. To effectively engage our simulation resources, i.e. our SPs, it was essential that we provide an orientation programme that would educate them on the use of telesimulation. Through an online training session, seen in Figure 1, the SPs were introduced to the rationale behind the adoption of telesimulation and the functionality of the Zoom platform. Topics such as how to use the video and audio effectively to build rapport during the interaction as well as functions such as moving between breakout rooms were covered. A telesimulation orientation manual was emailed to all SPs after the session, summarising the online training session, with step by step instructions and screenshot examples on how to use Zoom. See Figure 2 for summary of the orientation programme.

Figure 1. Simulated patient large group telesimulation training

Figure 2. Summary of SP orientation to history taking telesimulation encounter

45 SPs participated in a series of tele-simulated history taking encounters for the class of 82 students. All SPs were invited to participate in a post tele-simulation history taking electronic questionnaire. Using a 5-point Likert scale SPs were asked to indicate their agreement on 13 items as seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Likert scale items form post-telesimulation evaluation questionnaire

III. THE SP EXPERIENCE

Of the 45 respondents 64% were male, 36% were female, with 93% stating that they had participated in previous face-to-face sessions with students. Aged between 21 and 71 years, half of the respondents were over 50. To participate in the telesimulation the majority of SPs (67%) utilised a laptop or desktop computer, with 71% reporting that they used a headset. 80% of the SPs had previous experience with video-based calls prior to this session.

Key to the history taking encounters is the ability to communicate clearly. While 11% of SPs did report some technical difficulties related to Wi-Fi connectivity, the majority of SPs (91%) could hear the student clearly and 89% felt they could express themselves effectively. 96% felt they could communicate easily with the student. On whether they could see the medical student as well as they would in a face-to-face interaction, responses were mixed, with SPs acknowledging that the limitations of the telesimulation experience is the non-verbal communication component of the interaction:

“Sometimes, the lighting is not good enough to see the expression on the student’s face”, and “I was not able to observe students’ body posture via zoom as such, I was unable to comment fully on students’ non-verbal communication skills”.

One of the themes that arose in the written feedback was that many SPs appreciated the travelling time saved by being off-site during the telesimulation:

“I used to take 45-60mins to arrive/return at/from a SP rehearsal/session. Now it only takes 15mins to be in the meeting – saves a lot of traveling time; and all is done in the comfort of my home :)”.

Whilst it was acknowledged that telesimulation could not replace the authenticity of face-to-face interactions, the SPs overwhelmingly rated the experience as extremely positive, noting that the online training session and handout helped in learning how to negotiate the online platform. An unexpected benefit that was shared was the sense of connection that the telesimulation experience provided the SPs during a time of lockdown, as they “got to see other SPs”. One respondent shared how they were able to integrate these new skills to maintain social connections:

“…even it has broadened my experience and now been using this app for communication with friends during this CB (circuit breaker)”.

IV. CONCLUSION

As the restrictions around face-to-face teaching due to COVID-19 continues to impact how health professional educators engage SPs in teaching and assessing, this paper demonstrates how to safely and effectively engage the SP workforce during a pandemic. By describing the experience of SPs in adopting telesimulation to teach history taking, we hope that fellow educators across the region can continue to engage SPs in their curriculum.

Notes on Contributors

Kirsty J Freeman is the main author, conceptualised, wrote and revised the manuscript based on comments and suggestions from the other authors. She contributed to the development and facilitation of the simulated patient telesimulation training programme, and conducted the data collection.

Xin Weiren Wilson developed and conducted the simulated patient telesimulation training programme, assisted with data collection, performed the data analysis, and developed the manuscript.

Claire Ann Canning assisted with data collection, and contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript, reviewed and revised drafts.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the simulated patients who took part in the telesimulation programme and were willing to share their experiences. We also wish to acknowledge the Clinical Faculty and Administrative Coordinators of the FOCP programme for adopting telesimulation into the programme.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Hulsman, R. L., Harmsen, A. B., & Fabriek, M. (2009). Reflective teaching of medical communication skills with DiViDU: Assessing the level of student reflection on recorded consultations with simulated patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 74(2), 142-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.009

Keifenheim, K., Teufel, M., Ip, J., Speiser, N., Leehr, E., Zipfel, S., & Herrmann-Werner, A. (2015). Teaching history taking to medical students: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 15(159), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0443-x

Lioce L., Lopreiato J., Downing D., Chang T.P., Robertson J.M., Anderson M., Diaz D.A., Spain A.E., & Terminology and Concepts Working Group (2020). Healthcare Simulation Dictionary (2nd Ed.). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://doi.org/10.23970/simulationv2

McCoy, C. E., Sayegh, J., Alrabah, R., & Yarris, L. M. (2017). Telesimulation: An innovative tool for health professions education. Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training, 1(2), 132-136. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10015

Nestel, D., & Kidd, J. (2003). Peer tutoring in patient-centred interviewing skills: Experience of a project for first-year students. Medical Teacher, 25(4), 398-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159031000136752

*Kirsty J Freeman

Duke-NUS Medical School

8 College Rd,

Singapore 169857

Email: kirsty.freeman@duke-nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.