Perspectives of the Asian standardised patient

Submitted: 19 June 2020

Accepted: 21 October 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 25-30

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/OA2327

Nicola Ngiam1,2 & Chuen-Yee Hor1

1Centre for Healthcare Simulation, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Khoo Teck Puat-National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Standardised patients (SPs) have been involved in medical education for the past 50 years. Their role has evolved from assisting in history-taking and communication skills to portraying abnormal physical signs and hybrid simulations. This increases exposure of their physical and psychological domains to the learner. Asian SPs who come from more conservative cultures may be inhibited in some respect. This study aims to explore the attitudes and perspectives of Asian SPs with respect to their role and case portrayal.

Methods: This was a cohort questionnaire study of SPs involved in a high-stakes assessment activity at a university medical school in Singapore.

Results: 66 out of 71 SPs responded. Racial distribution was similar to population norms in Singapore (67% Chinese, 21% Malay, 8% Indian). SPs were very keen to provide feedback to students. A significant number were uncomfortable with portraying mental disorders (26%) or terminal illness (16%) and discussing Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS, 14%) or Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs, 14%). SPs were uncomfortable with intimate examinations involving the front of the chest (46%, excluding breast), and even abdominal examination (35%). SPs perceive that they improve quality of teaching and are cost effective.

Conclusion: The Asian SPs in our institution see themselves as a valuable tool in medical education. Sensitivity to the cultural background of SPs in case writing and the training process is necessary to ensure that SPs are comfortable with their role. Additional training and graded exposure may be necessary for challenging scenarios and physical examination.

Keywords: Standardised Patients, Perspective, Asian, Medical Education, Survey

Practice Highlights

- The Asian SPs in our institution see themselves as a valuable tool in medical education.

- Sensitivity to the cultural background of SPs in case writing and the training process is necessary to ensure that SPs are comfortable with the roles that they portray.

- Additional training and graded exposure for SPs may be necessary for challenging scenarios and physical examination in the Asian context.

I. INTRODUCTION

Standardised patients (SPs) have been involved in medical education since the 1960s (Barrows & Abrahamson, 1964). SP methodology has been widely used in North America and Europe. By the 1990s, majority of American medical schools were using the SP methodology in teaching clinical skills, assessments and for providing feedback to learners (Anderson et al., 1994). The prevalence of employing SP methodology in medical education in Asia is presumed to be less ubiquitous. It is therefore imperative to understand the views of Asian SPs so that the SP methodology can be fostered.

SPs started out simulating medical symptoms and patient concerns as well as evaluating medical interviewing skills in 1976 (Barrows & Abrahamson, 1964; Stillman et al., 1976). Their role has evolved to demonstrating abnormal physical signs, providing feedback on medical interviewing skills and being involved in hybrid simulations. This increases their exposure to the medical environment and to different medical experiences that they may not have experienced before. Certain experiences may potentially cause psychological distress. The SP could be in a vulnerable position and personal attitudes and beliefs towards illness should be taken into consideration when engaging SPs to portray these roles.

This is particularly true in Asian SPs. For example, patients may not be willing to discuss mental health issues for fear of social stigma and shame (Kramer et al., 2002). Asian SPs are also likely to be more conservative and modest with regards to physical examination. This can be extrapolated from findings that cultural attitudes toward breast cancer screening tests and modesty are some reasons why Asian women are reluctant to seek out breast cancer screening (Parsa et al., 2006).

In the past, SPs were routinely employed in objective structured clinical examinations at our medical school. They were not required to provide any form of feedback to the learners. We endeavoured to develop a more structured SP training program at our institution. In the initial phase, this study was conducted to survey the attitudes of the SPs who work at our institution towards case portrayal and the value of SP methodology.

II. METHODS

This was an anonymous cohort questionnaire study. An online questionnaire was administered to standardized patients who were recruited to work at a high-stakes objective structured clinical examination at a university medical school. Participants were sent a link to an electronic survey by email after the event. Participation was voluntary. Questions about race, age, gender and years of experience as an SP were asked. The importance of the contribution of an SP to medical education and their comfort with discussing medical conditions, portraying abnormal signs and undergoing different physical examinations were evaluated. A Likert scale of 1-5 was used where appropriate. This questionnaire study is covered by the institutional review board approval (Study Reference Number: 09-288) of the standardised patient program in our institution. Being an anonymous, voluntary survey, the consent was implied when the participants filled and returned the completed survey.

Descriptive statistics and the electronic survey were generated using Vovici software version 6 (Vovici Corp, Dulles, Virginia, United States).

III. RESULTS

66 out of 71 SPs (93%) responded. 40% of the SPs were aged 31-40 years (Figure 1) and 72% were female. Racial distribution was similar to population norms in Singapore (67% Chinese, 21% Malay, 8% Indian, 4% others).

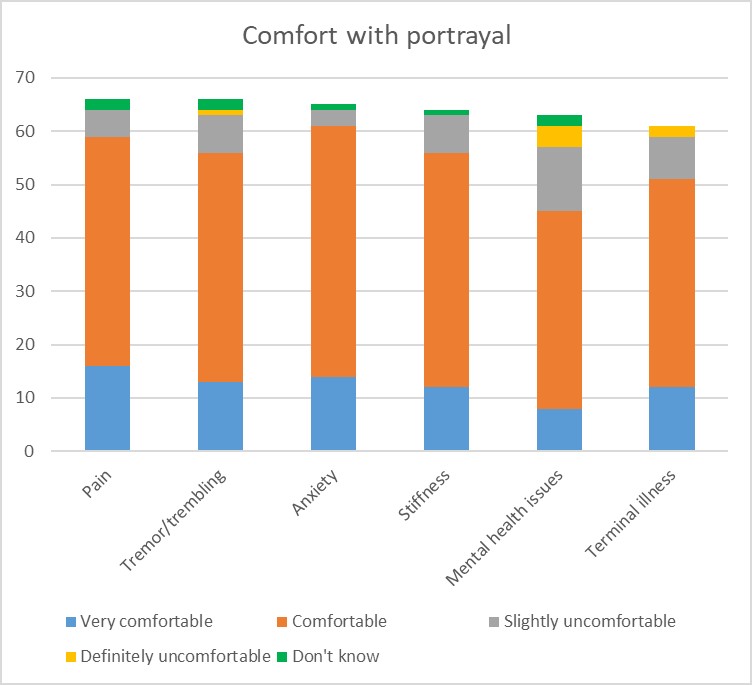

Figure 1: SP comfort with portrayal

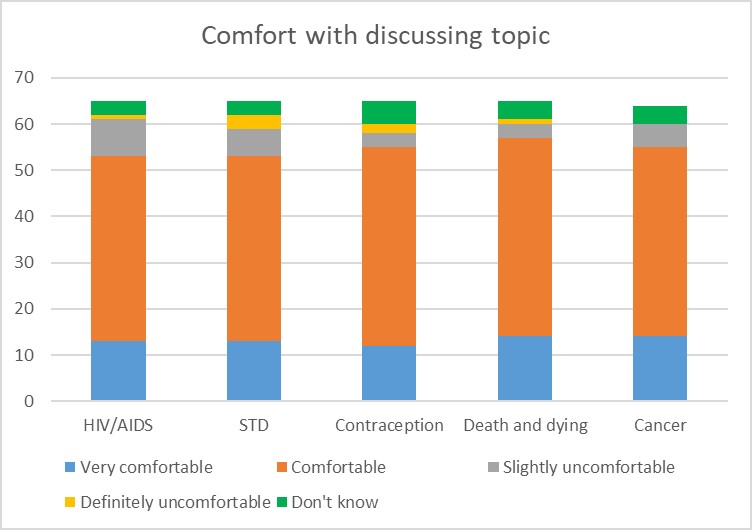

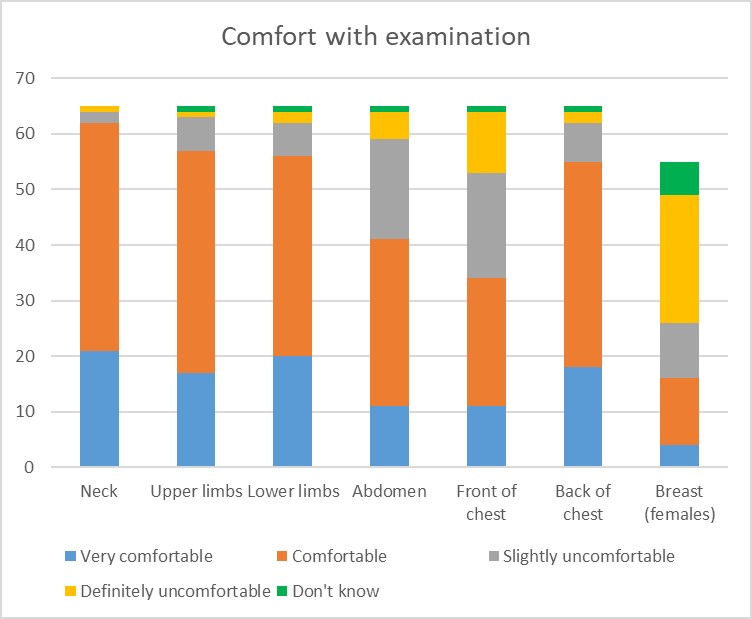

With regards to their role, 95% of SPs felt it was important for them to be involved in teaching students and providing feedback. A significant number were uncomfortable with portraying mental disorders (26%) or terminal illness (16%) (Figure 1) and discussing HIV/AIDS (14%) or sexually transmitted diseases (14%) (Figure 2). With regards to death and dying, 6% of SPs were uncomfortable discussing this while another 6% were unsure about it. As expected, SPs were uncomfortable with examinations involving the front of the chest (46%, excluding breast examination) and even abdominal examination (35%). The 60% of the female SPs surveyed were uncomfortable with breast examination (Figure 3). SPs perceive themselves to improve the quality of teaching (98%) and to be cost effective (98%). The majority of this group of SPs (83%) felt that this was a viable option for sustainable employment.

Figure 2: SP comfort with discussing topic

Figure 3: SP comfort with physical examination

IV. DISCUSSION

The benefits of SP methodology in providing a safe environment for practice and experiential learning are well established. In an effort to expand the use of SP methodology at our institution, information regarding the acceptability and feasibility were required. In the past, SPs were mainly employed in summative assessment activities and did not provide learners with feedback. Before pushing the boundaries of the SP job description, it was important to understand the perspectives of our SPs and which areas of SP work they would feel comfortable or uncomfortable with.

The areas of interest were comfort with portraying roles that involved taboo topics such as mental health issues, sexually transmitted disease, death and dying. In many Asian cultures, mental illness is stigmatizing; it reflects poorly on family lineage and can influence others’ beliefs about the suitability of an individual for marriage. (Kramer et al., 2002). Many people of Asian descent view people with mental illnesses as dangerous and aggressive (Lauber & Rössler, 2007) and believe that mental illness is a punishment from God (Fogel & Ford, 2005). In China, mental health problems are believed to be a result of weak character, having evil spirits, or punishment for not respecting ancestors (Lam et al., 2006). Asian American women avoid seeking treatment for depression and suicide ideation because of Asian family and community stigma associated with mental health issues (Augsberger et al., 2015). With regards to sexual practices and sexually transmitted disease, literature shows that Chinese men regard homosexual-related stigma and discrimination as major barriers to HIV testing. Most men were reluctant to obtain an HIV test in fear that their homosexual identity would be exposed, and they sometimes encountered discrimination even from medical personnel (Wei et al., 2014). Living with HIV in an Asian society is fraught with difficulty in the context of fear and disapproval (Ho & Goh, 2017). Death and dying are generally considered taboo in Asian cultures. Open discussions about death are regarded as a bad omen (Hall & Hall, 1976). Even for those who are dying, discussion about death is avoided because it is believed that such talk may hasten the dying process or even cause death prematurely (Xu, 2007). The avoidance if discussion about death and dying in traditional Chinese culture has been found to impede the ability to discuss advanced care planning (Cheng, 2018). These cultural beliefs were reflected in the discomfort expressed by some study participants with portrayal of roles involving mental health issues, HIV or sexually transmitted diseases, terminal illness and death and dying. This is evidence that some of our SPs do have traditional Asian perspectives regarding these sensitive issues but it is encouraging that a larger proportion are comfortable with these issues. This informs us that SPs should be given advanced notice regarding the content of the case that they are expected to portray so that they can make an informed choice when accepting roles. This is especially important when taboo or sensitive content is involved. SPs should also be given an option to withdraw from the assignment if they feel uncomfortable with the content of the case after they have been trained for the case.

In view of the more conservative nature of Asians, the hypothesis was that there could be areas of the body that SPs would not be willing to have examined by students. Asian women seem to be more conservative as only 53% of respondents in a study did breast self-examinations (Sim et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2005) reported that, between 2000 and 2003, 21.5% of women in Singapore presented with stage III or IV breast cancer which may potentially be due to cultural attitudes toward breast cancer screening tests and modesty, which inhibit Asian women from participating in breast cancer screening (Parsa et al., 2006). Spiritual and religious beliefs were found to act as a barrier to breast cancer screening in Singaporean Malay women (Shaw et al., 2018). As expected, more than half of our female SPs were uncomfortable with breast examination. When both genders were considered, examination of the front of chest (excluding breast) and abdominal examination were also flagged as concerns. This made us aware of the hesitance of some SPs in this area and the need to explore this further while trying to expand the role of the SP. In developing our SP program, consent for physical examination needs to be explained in detail and comfort of the individual SP with any physical examination must be taken into consideration.

The SPs in our study perceived themselves to be of value in medical education. Standardized patients in a study in Switzerland felt motivated, engaged, and willing to invest effort in their task and did not mind the increasing demands of their work as long as the social environment in SP programs was supportive (Schlegel et al., 2016). This is encouraging for a developing SP program to know as we feel confident to expand the job scope of our SPs as long as adequate explanation and training is provided to support the SPs. With more structured coaching and exposure, we expect that SPs will become more comfortable with more challenging roles and would be willing to push the boundaries of their comfort zone.

One limitation of this study is the large majority of female participants. This was a convenience sample to optimize response rate. Further studies should aim to include a more balanced gender representation. Another limitation would be that only quantitative data was collected. In exploring perspectives, focused interviews with qualitative analysis would have provided a more in-depth understanding of the beliefs and values of the SPs.

V. CONCLUSION

This study provides initial insights into the perspectives of Asian SPs at a university medical school in an Asian country. They see themselves as a valuable tool in medical education and are willing to expand their role in the curriculum. Faculty and trainers need to be sensitive to the cultural background of our SPs in case writing and the training process to ensure that SPs are comfortable with the roles that they portray. This is of particular relevance to SP programs that employ predominantly Asian SPs. There is evidence from this study of discomfort with portraying patients with mental health issues, terminal illness and sexually transmitted diseases. The areas of exposure required in physical examination also need to be carefully considered. Additional training and graded exposure may be necessary for SPs willing to be involved in these scenarios and certain types of physical examination. Concerns about the scenario from the SPs may not be immediately apparent. The results presented here will make SP trainers more aware of the possibility of SP discomfort. Future research will be required on what type of training and what other factors will promote comfort with these scenarios as well as the impact of taking on such roles on the SPs.

Notes on Contributors

Nicola Ngiam conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data and interpreted the results, wrote the manuscript draft, revised it, read it and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Hor Chuen-Yee developed the methodological framework for the study, performed data collection and data analysis, revised the manuscript, read it and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study is covered by the institutional review board approval (Study Reference Number: 09-288).

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Dimple Rajgor for her assistance in editing, formatting, reviewing, and in submitting the manuscript for publication.

Funding

No funding source required.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Anderson, M. B., Stillman, P. L., & Wang, Y. (1994). Growing use of standardized patients in teaching and evaluation in medical education. Teaching and Learning in Medicine: An International Journal, 6(1), 15-22.

Augsberger, A., Yeung, A., Dougher, M., & Hahm, H. C. (2015). Factors influencing the underutilization of mental health services among Asian American women with a history of depression and suicide. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 542-542. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1191-7.

Barrows, H. S., & Abrahamson, S. (1964). The programmed patient: A technique for appraising student performance in clinical neurology. Academic Medicine, 39(8), 802-805.

Cheng, H. W. B. (2018). Advance care planning in Chinese seniors: Cultural perspectives. Journal of Palliative Care, 33(4), 242-246.

Fogel, J., & Ford, D. (2005). Stigma beliefs of Asian Americans with depression in an internet sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(8), 470-478.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, E. (1976). How cultures collide. Psychology Today, 10(2), 66-74.

Ho, L. P., & Goh, E. C. L. (2017). How HIV patients construct liveable identities in a shame based culture: The case of Singapore. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 1333899. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2017.1333899

Kramer, E., Kwong, K., Lee, E., & Chung, H. (2002). Cultural factors influencing the mental health of Asian Americans. The Western Journal of Medicine, 176(4), 227-231.

Lam, C. S., Tsang, H., Chan, F., & Corrigan, P. W. (2006). Chinese and American perspectives on stigma. Rehabilitation Education, 20(4), 269-279. https://doi.org/10.1891/088970106805065368

Lauber, C., & Rössler, W. (2007). Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(2), 157-178.

Parsa, P., Kandiah, M., Abdul, H. R., & Zulkefli, N. (2006). Barriers for breast cancer screening among Asian women: A mini literature review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 7(4), 509-514.

Schlegel, C., Bonvin, R., Rethans, J., & der Vleuten Van, C. (2016). Standardized patients’ perspectives on workplace satisfaction and work-related relationships: A multicenter study. Simulation in Healthcare: Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 11(4), 278-285.

Shaw, T., Ishak, D., Lie, D., Menon, S., Courtney, E., Li, S. T., & Ngeow, J. (2018). The influence of Malay cultural beliefs on breast cancer screening and genetic testing: A focus group study. Psycho‐Oncology, 27(12), 2855-2861.

Sim, H., Seah, M., & Tan, S. (2009). Breast cancer knowledge and screening practices: A survey of 1,000 Asian women. Singapore Medical Journal, 50(2), 132-138.

Stillman, P. L., Sabers, D. L., & Redfield, D. L. (1976). The use of paraprofessionals to teach interviewing skills. Pediatrics, 57(5), 769-774.

Tan, E., Wong, H., Ang, B., & Chan, M. (2005). Locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer in a tertiary hospital. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 34(10), 595-601.

Wei, C., Yan, H., Yang, C., Raymond, H., Li, J., Yang, H., Zhao, J., Huan, X., & Stall, R. (2014). Accessing HIV testing and treatment among men who have sex with men in China: A qualitative study. AIDS Care, 26(3), 372-378.

Xu, Y. (2007). Death and dying in the Chinese culture: Implications for health care practice. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 19(5), 412-414.

*Nicola Ngiam

Department of Medicine

National University Health System

1E Kent Ridge Rd,

Singapore 119228

Email address: nicola_ngiam@nuhs.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.