Peer-to-peer clinical teaching by medical students in the formal curriculum

Submitted: 2 December 2022

Accepted: 24 July 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 13-22

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/OA3093

Julie Yun Chen1,2, Tai Pong Lam1, Ivan Fan Ngai Hung3, Albert Chi Yan Chan4, Weng-Yee Chin1, Christopher See5 & Joyce Pui Yan Tsang1

1Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 2Bau Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 3Department of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 4Department of Surgery, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 5School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Abstract

Introduction: Medical students have long provided informal, structured academic support for their peers in parallel with the institution’s formal curriculum, demonstrating a high degree of motivation and engagement for peer teaching. This qualitative descriptive study aimed to examine the perspectives of participants in a pilot peer teaching programme on the effectiveness and feasibility of adapting existing student-initiated peer bedside teaching into formal bedside teaching.

Methods: Study participants were senior medical students who were already providing self-initiated peer-led bedside clinical teaching, clinicians who co-taught bedside clinical skills teaching sessions with the peer teachers and junior students allocated to the bedside teaching sessions led by peer teachers. Qualitative data were gathered via evaluation form, peer teacher and clinician interviews, as well as the observational field notes made by the research assistant who attended the teaching sessions as an independent observer. Additionally, a single Likert-scale question on the evaluation form was used to rate teaching effectiveness.

Results: All three peer teachers, three clinicians and 12 students completed the interviews and/or questionnaires. The main themes identified were teaching effectiveness, teaching competency and feasibility. Teaching effectiveness related to the creation of a positive learning environment and a tailored approach. Teaching competency reflected confidence or doubts about peer-teaching, and feasibility subthemes comprised barriers and facilitators.

Conclusion: Students perceived peer teaching effectiveness to be comparable to clinicians’ teaching. Clinical peer teaching in the formal curriculum may be most feasible in a hybrid curriculum that includes both peer teaching and clinician-led teaching with structured training and coordinated timetabling.

Keywords: Peer Teaching, Undergraduate Medical Education, Bedside Teaching, Medical Students

Practice Highlights

- Peer-led teaching environment facilitates questions and answers from learners to strengthen learning.

- Training on specific skills and pre-case preparation can help improve peer teacher effectiveness.

- Clear understanding of the logistics and expectations is necessary to optimise the process.

- Formal peer teacher training may help quality assurance and encourage more participation.

I. INTRODUCTION

In accordance with the longstanding apprenticeship model of medical training, senior doctors and trainees have been responsible for teaching their junior colleagues across the continuum of medical education. Despite this accepted practice, peer teaching has not become widely formalised in undergraduate medical curricula.

Peer teaching has been shown to be beneficial at multiple levels. For students who are being taught by peers, learning is enabled by social and cognitive congruence because of the near-peer demographic which allows for a more comfortable learning environment for free flow of discussion and better understanding of the learner’s challenges including awareness of the primacy for exam success (Benè & Bergus, 2014; Rees et al., 2016). The peer teacher develops and hones teaching skills that will be useful in internship (Haber et al., 2006) and through teaching, develops higher motivation and deeper understanding of concepts and perhaps also improve their own exam performance (Burgess et al., 2014). The institution derives some practical benefit from the supplementary manpower (Tayler et al., 2015) due to the comparable effectiveness of peer teachers in teaching in certain areas such as physical examination and communication skills (Rees et al., 2016) but perhaps most importantly, it benefits from building a collaborative relationship with students in their learning process. Though the benefits of peer teaching have been noted, students remain an untapped resource as training provided for students to serve as teachers is inconsistent (Soriano et al., 2010).

Undergraduate medical curricula aim to provide a foundation for future training and the framework for such curricula are guided by the recognition that medical students must achieve certain outcomes, including being able to teach, to be prepared for future practice. Well-accepted frameworks such as the ‘Outcomes for Graduates’, from the UK General Medical Council (2015) and the ‘CanMEDS Framework’ from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (2015) expect medical graduate to teach others. In Hong Kong, similar guidance is provided in the document ‘Hong Kong Doctors’ published by the Medical Council of Hong Kong, which states that undergraduate medical education must prepare graduates to fulfil the roles of ‘medical practitioner, communicator, educator…’ (Medical Council of Hong Kong, 2017).

It is common in medical schools to have informal peer teaching, where senior students coach junior students on an ad hoc basis or organise revision sessions before exams. Zhang et al. (2011) revealed that a majority of medical students believed that informal learning approaches, including the use of past student notes, and participation in self-organised study groups and peer-led tutorials, helped them pass examinations and be a good doctor. Similarly, in our institution, these kinds of informal peer teaching are popular among students and include sharing sessions on study and exam tips, bedside sessions, and sharing of organised study notes. These activities are not subject to any formal oversight.

With the documented benefits of peer teaching, the availability of enthusiastic senior students who are willing to coach their junior peers, and the demand from junior students to learn from their seniors, there is an opportunity to harness the potential peer teaching that is already taking place. This pilot project is important as it aimed to adapt existing student-initiated peer bedside teaching into the formal bedside teaching curriculum and to examine the perspectives of participants on the effectiveness and feasibility of this initiative. It will be helpful to understand the benefits and drawbacks of formal peer bedside teaching in order to further develop this pedagogical approach in medical education.

II. METHODS

This was a descriptive qualitative study of participants in a pilot peer-teaching initiative for bedside teaching implemented in the first clinical year of study for medical students.

A. Setting

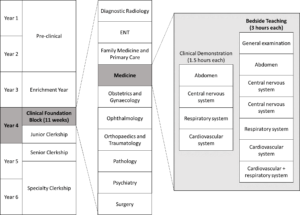

1) Small group bedside teaching for Year 4 medical students in the Clinical Foundation Block: The 11-week Clinical Foundation Block (CFB) of the MBBS Year 4 curriculum at The University of Hong Kong runs from August to October and is the first block of the first clinical year of study. It serves to prepare students for the ward- and clinic-based teaching to follow in the clinical clerkships (Figure 1). Year 4 medical students were selected for the study because it is the first clinical year of study when clinical bedside teaching begins. In addition, as the most junior clinical students, they would benefit most from learning from their senior peers. During the CFB, all Year 4 students learn basic history taking, physical examination and clinical skills as well as common clinical problems of 10 key specialty disciplines. In internal medicine, students attend whole class sessions in which the proper clinical examination of each body system is demonstrated followed by seven small group sessions at the bedside for hands-on practice led by a clinician.

Figure 1. Teaching activities under Medicine within the Clinical Foundation Block in the medical curriculum

Each small group bedside teaching session is comprised of six to eight CFB students who follow the same clinical teacher to examine 3 pre-selected ward patients over a two-hour period. In this pilot study, a peer teacher joined the clinical teacher for the bedside teaching with the first patient case taught by the clinician, the second case taught by the peer teacher under the supervision of the clinician and the final case taught by the peer teacher alone.

2) Peer teaching recruitment and training: Over the years, medical students have been organising bedside peer-teaching on their own and we identified these peer-teaching leaders to help recruit peer teachers for this initiative. Peer teachers recruited in July 2018 and comprised Year 5 students in Senior Clerkship, who were enthusiastic in teaching, and were available to join the training tutorial and take up a subsequent Year 4 CFB bedside teaching session. During the 2.5-hour tutorial, the CFB Coordinator explained the project, and three clinicians then provided a briefing on cardiovascular, neurological, respiratory and abdominal physical examination, common pitfalls, and how to give feedback. There was also time for students to raise questions both on the project and bedside teaching techniques.

B. Participants

The target participants included the three peer teachers who were recruited for this study, together with the three clinician partners and the 24 CFB students in the corresponding three bedside teaching groups. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection.

C. Data Collection

The qualitative data were collected using a dual subjective (peer teachers, clinicians and students) and objective (independent observer) approach was taken to provide a more holistic perspective of the peer teaching experience. A research assistant not involved in the teaching followed one (of the three) peer teachers as the independent observer. All peer teachers and clinicians were interviewed in-person, by phone or by email, using an interview guide (Appendix 1) by the research assistant after the session where field notes were taken and transcribed. CFB students were invited to complete an evaluation form comprised of open-ended questions and a single Likert-scale question (Appendix 2) immediately after the bedside session, to rate effectiveness and to give general feedback about the peer teaching session.

D. Data Analysis

The qualitative data comprising interview field notes, interview transcripts, email transcripts and open-ended questions from the evaluation form collected from CFB students were analysed thematically by the authors JC and JPYT. The Likert-scale question from the evaluation form was analysed using descriptive statistics. All data were anonymised.

III. RESULTS

All three peer teachers and three clinicians who participated in the pilot peer teaching sessions were interviewed. Eighteen out of 24 CFB students consented to participate and 12 completed questionnaires were collected. Three main themes were identified with two corresponding subthemes for each.

A. Teaching Effectiveness

Peer teachers were rated favourably in terms of their teaching effectiveness. From the evaluation form completed by CFB students, the mean peer teaching effectiveness rating was 4.5/5. While a few students felt the teaching effectiveness of clinicians and peer teachers was comparable, many of them felt less intimidated being taught by the peer teachers. Students also appreciated that the peer teachers understood their current level of understanding and therefore were able to make the teaching more effective by tailoring it to their needs. Students found the experience-sharing by the peer teachers an added-value as shown in Table 1 (Item 1-4). All clinicians agreed that the CFB students appeared more relaxed while the peer teachers were teaching, and the peer teachers met their standard of professionalism as shown in Table 1 (Item 3).

|

Subtheme: Learning environment |

|

1. ‘I was more willing to ask questions.’ – CFB Student 8 |

|

2. ‘I felt more comfortable and less intimidate[ed] with the peer teacher.’ – CFB Student 12 |

|

3.‘I think it is pretty well received among the CFB students – they looked like they are more comfortable and less stressed.’ – Clinician B |

|

Subtheme: Tailoring to needs |

|

4.‘We were told her past experience.’ – CFB Student 9 |

|

5.‘More exam advice from peer tutor.’ – CFB student 10 |

Table 1. Exemplar quotes from participants on teaching effectiveness

These comments were congruent with the observations of the independent observer. When the clinician was teaching, students appeared to be cautious when performing physical examination and answering questions from the clinician. On the other hand, when the peer teacher was teaching, students were asking for reassurance while performing physical examination, and appeared less hesitant when attempting to answer the questions. The peer teacher sometimes also asked the students how they would do a certain examination before they actually performed it. He also shared his own bedside experience. After the clinician ended the bedside session and left, the peer teachers stayed behind and answered further questions from the students regarding physical examination skills and examination tips.

B. Teaching Competence

For students, the teaching on physical examination skills by peer teacher appeared to be comparable to that by clinicians, with the perceived benefit of tailored instructions to student’s current level, and additional personal experience sharing as shown in Table 2 (Item 1-2).

After co-teaching with the peer teacher, clinicians had different opinions about the competency of an undergraduate student as a formal peer teacher. Two stated that it was more appropriate for senior students to do sharing instead of teaching, while the other was satisfied with the ability of the peer teachers to teach, and appreciate the opportunity to exchange ideas with peer teachers. One clinician also suggested that peer teachers might need more practice on teaching to build up confidence as shown in Table 2 (Item 3, 6 and 7).

On the other hand, all the peer teachers expressed that they felt stressed being observed by the clinicians. Two of them felt confident to teach, while one was less confident and prefer to co-teach with a clinician as shown in Table 2 (Item 4, 5 and 8).

The peer teachers also questioned their role as a peer teacher in the regular curriculum. They were unsure to teach in place of clinicians in the regular bedside sessions for the CFB students, yet were more comfortable to co-teach with the clinicians, or to teach in unofficial or supplementary peer-led sessions as shown in Table 2 (Item 4, 8 and 9).

|

Subtheme: Confidence in teaching competence |

|

1. ‘Very comprehensive teaching; detailed explanation on how to report findings.’ – CFB Student 1 |

|

2. ‘Senior students know what we need to know and what we don’t know at this stage.’ – CFB Student 5 |

|

3. ‘The peer teacher was sufficiently prepared on content knowledge and teaching skills.’ – Clinician A |

|

4. ‘I am confident with my knowledge and teaching skills. The CFB cases were easy enough for me to handle. I have been teaching student-initiated sessions anyway.’ – Peer Teacher A |

|

5. ‘Are we going to replace the clinicians? The student-initiated sessions worked just fine.’ – Peer Teacher B |

|

Subtheme: Doubts on teaching competence |

|

1. ‘It is too early for the current peer teachers to teach as they lack competency and confidence in teaching.’ – Clinician B |

|

2. ‘Tutors should be at least medical graduates who have shown evidence of proficiency and knowledge in the areas that they teach. Senior students can share their experience of learning, but not to teach.’ – Clinician C |

|

3. ‘The clinicians are definitely better at teaching and has better skills… It would work better if I was to co-teach with a clinician but not to teach solo.’ – Peer Teacher C |

|

4. ‘It isn’t appropriate to take away the proper learning opportunity to be taught by clinicians from the students.’ – Peer Teacher C |

Table 2. Exemplar quotes from participants on teaching competency

C. Feasibility

1) Barriers: One of the peer teachers was disappointed that the session did not go as planned. He suspected that the clinicians may not truly understand the purpose and the plan for the project, and hence sometimes took the lead when the peer teachers were supposed to be teaching as shown in Table 3 (Item 1).

They also mentioned that timetabling conflicts between CFB and Senior Clerkship were also an issue. For all groups, the session overran and resulted in peer teachers missing their own class, which was scheduled immediately following the intended finishing time of this bedside session.

Peer teachers also commented that there was no concrete incentive for them to join the project. With the added pressure of being observed by clinicians, most peer teachers were hesitant to volunteer again.

2) Facilitators: One peer teacher considered it as an extra learning opportunity as shown in Table 3 (Item 2). Clinicians also believed that the peer teachers could benefit since these were essentially extra tutorials and bedside exposure for them outside of the regular curriculum although students thought that the cases used for CFB were too easy for them to learn anything new. Both peer teachers and clinicians agreed that more practical training on physical examination would be beneficial to boost the confidence and competence of the peer teachers in teaching. Peer teachers suggested that to make the session more efficient, they would prefer to clerk the case themselves before the session, to be better prepared to recognise abnormal physical signs shown in Table 3 (Item 3). A pre-meeting between the peer teacher and the partner clinician would be helpful to clarify expectations and understanding of the process since the training tutorial was conducted by a different clinician. A clinician pointed out that an open call should be made for the recruitment to allow all interested students to participate.

|

Barriers |

|

1. ‘I felt like the clinician did not want to let me teach solo. Maybe he did not understand the project.’ – Peer Teacher A |

|

Facilitators |

|

2. ‘The organisation of the curriculum is weird – there were a lot to learn in the Medicine Block of the Junior Clerkship, but not much in that of Senior Clerkship. There was also a large gap of time where there was no supervised physical examination at bedside. This is a good refresher session for me.’ – Peer Teacher C |

|

3. The students and I all saw the case for the first time during the session. I felt a bit unprepared and can only comment on the physical examination skills of the students. There is no way to tell if they reported the correct findings. It would help if the peer tutors can clerk the case before the session.’ – Peer Teacher C |

Table 3. Exemplar quotes from participants on barriers and facilitators

IV. DISCUSSION

This pilot project aimed to examine the effectiveness and feasibility of adapting peer bedside teaching into the formal curriculum. Student rating has been used as the primary measure of teaching effectiveness in many schools (Chen & Hoshower, 2003). In this project, we triangulated student ratings with clinician viewpoint and also that of an independent observer to assess teaching effectiveness. All found the teaching by the peer teachers was professional and comparable to clinicians.

Their views were also congruent to the observation that peer teaching provided a more relaxed learning environment as cited in the literature (Tai et al., 2016). This is reflected in a study on problem-based learning (PBL) that showed student tutor-led tutorials were rated more highly in group functioning and supportive atmosphere, compared with faculty-led sessions (Kassab et al., 2005).

Sharing from peer teachers was also identified as a bonus feature of bedside peer teaching in our study. Sharing from senior students not only provide junior student with practical exam and ward survival tips, but also served as inspiration and motivation for students to learn. Again this has also been observed in other studies such as one in which students whose peer teachers shared real life experiences performed better in a post-training CPR knowledge test, and demonstrated more confidence and learning motivation (Souza et al., 2022).

In the next incarnation of peer teaching the barriers and facilitators noted by stakeholders need to be addressed. The difficulty in scheduling can be overcome by engaging senior students who are already on the ward to teach by embedding this requirement as part of their usual work. A clinical peer-assisted learning programme by Nikendei, et al. (Nikendei et al., 2009) had demonstrated a successful peer teaching programme at the bedside with final year medical students who were working in the wards as tutors. The comment among peer teachers that there is no ‘concrete incentive’ to being a peer teacher may be due a lack of awareness of the appreciation from peer learners as well as from faculty teachers. More regular and deliberate sharing of learner feedback and role modelling the enjoyment of teaching by teachers and experienced peer teachers can help. Reflecting on the benefits of the learning process undertaken through the preparation and ‘paying forward’ the efforts from other teachers are also less tangible (but important!) factors to emphasise to encourage future students to undertake peer-teaching.

Peer teachers and clinicians should meet before the teaching session to clarify aims and logistics, and match their expectations. To improve peer teacher confidence and to alleviate clinician concern about their competency to teach, more extensive and formal training can be provided to peer teachers, including both theoretical and practical training on physical examination, and on teaching skills. Burgess et al. (2017) had developed and implemented an interprofessional Peer Teaching Training (PTT) programme for medicine, pharmacy and health sciences students, which aimed to develop students’ skills in teaching, assessment and feedback for peer assisted learning and future practice. The PTT course design was adapted by Karia et al. (Karia et al., 2020) for medical students only. Both programmes were shown to be effective in improving students’ confidence and competence in peer teaching, and increasing intention to participate in teaching. This is encouraging and we are also developing a structured peer teaching training programme to fill this gap. Nevertheless, when attempting to include peer teachers in the formal curriculum as a complement to formal teaching by the faculty care must be taken to not over-formalise the process which may undermine the unique benefits of peer teaching (Tong & See, 2020).

A. Strengths and Limitations

This was a small-scale pilot study and the evaluation of the impact was limited to perceptions and feedback from stakeholders and did not include tangible outcomes such as academic performance and clinical competency of participants. However, the objective contemporaneous observations made during the teaching sessions by a third-party researcher strengthened the trustworthiness of the data. A 360-degree evaluation including feedback from patients and ward staff could also provide a more comprehensive evaluation.

V. CONCLUSION

This study examined the perspectives of clinicians, peer teachers and students on the effectiveness and feasibility of peer-led bedside teaching in the formal curriculum and the benefits are encouraging. Peer teaching effectiveness was comparable to clinicians with the added benefit that peer-teachers are better able to understand and meet students’ needs while creating a friendlier environment conducive to constructive learning. Concerns about peer teaching competency were expressed by clinicians and peer-teachers and all participants did not wish to have peer-teaching replace clinician-led teaching. Clinical peer teaching in the formal curriculum may be most feasible in a hybrid curriculum that includes both peer teaching and clinician-led teaching. It can be accomplished with more structured training and overcoming practical barriers of timetabling and preparation. The benefits of peer teaching and promising responses from all stakeholders support further initiatives in clinical peer teaching.

Notes on Contributors

JY Chen designed the study, performed data collection and data analysis, drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

TP Lam designed the study, gave critical feedback, read and approved the final manuscript.

IFN Hung designed the study, gave critical feedback, read and approved the final manuscript.

ACY Chan designed the study, gave critical feedback, read and approved the final manuscript.

WY Chin designed the study, gave critical feedback, read and approved the final manuscript.

JPY Tsang performed data collection and data analysis, drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

C See designed the study, gave critical feedback, read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/ Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (Reference number: UW 18-439).

Data Availability

The data of this qualitative study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the participants.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the peer teachers, students and clinicians of HKUMed for participating in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by a Teaching Development Grant funded by The University of Hong Kong (Ref No:. N/A).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Benè, K. L., & Bergus, G. (2014). When learners become teachers: A review of peer teaching in medical student education. Family Medicine, 46(10), 783-787.

Burgess, A., McGregor, D., & Mellis, C. (2014). Medical students as peer tutors: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 115.

Burgess, A., Roberts, C., van Diggele, C., & Mellis, C. (2017). Peer teacher training (PTT) program for health professional students: Interprofessional and flipped learning. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), Article 239.

Chen, Y., & Hoshower, L. B. (2003). Student evaluation of teaching effectiveness: An assessment of student perception and motivation. Assessment Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(1), 71-88.

General Medical Council. (2015). Outcomes for graduates (Tomorrow’s Doctors). Retrieved July 18, 2022 from https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/Outcomes_for_graduates_jul_15_1216.pdf_61408029.pdf

Haber, R. J., Bardach, N. S., Vedanthan, R., Gillum, L. A., Haber, L. A., & Dhaliwal, G. S. (2006). Preparing fourth‐year medical students to teach during internship. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(5), 518-520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497. 2006.00441.x

Karia, C., Anderson, E., Hughes, A., West, J., Lakhani, D., Kirtley, J., Burgess, A., & Carr, S. (2020). Peer teacher training (PTT) in action. Clinical Teacher, 17(5), 531-537.

Kassab, S., Abu-Hijleh, M. F., Al-Shboul, Q., & Hamdy, H. (2005). Student-led tutorials in problem-based learning: Educational outcomes and students’ perceptions. Medical Teacher, 27(6), 521-526.

Medical Council of Hong Kong. (2017). Hong Kong Doctors. Retrieved July 18, 2022 from https://www.mchk.org.hk/english/publications/hk_doctors.html

Nikendei, C., Andreesen, S., Hoffmann, K., & Jünger, J. (2009). Cross-year peer tutoring on internal medicine wards: Effects on self-assessed clinical competencies–A group control design study. Medical Teacher, 31(2), e32-e35.

Rees, E. L., Quinn, P. J., Davies, B., & Fotheringham, V. (2016). How does peer teaching compare to faculty teaching? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Teacher, 38(8), 829-837.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. (2015). CanMEDS Framework. Retrieved July 18, 2022 from http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e

Soriano, R. P., Blatt, B., Coplit, L., CichoskiKelly, E., Kosowicz, L., Newman, L., Pasquale, S. J., Pretorius, R., Rosen, J. M., & Saks, N. S. (2010). Teaching medical students how to teach: a national survey of students-as-teachers programs in US medical schools. Academic Medicine, 85(11), 1725-1731.

Souza, A. D., Punja, D., Prabhath, S., & Pandey, A. K. (2022). Influence of pretesting and a near peer sharing real life experiences on CPR training outcomes in first year medical students: A non-randomized quasi-experimental study. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 1-11.

Tai, J., Molloy, E., Haines, T., & Canny, B. (2016). Same‐level peer‐assisted learning in medical clinical placements: A narrative systematic review. Medical Education, 50(4), 469-484.

Tayler, N., Hall, S., Carr, N. J., Stephens, J. R., & Border, S. (2015). Near peer teaching in medical curricula: Integrating student teachers in pathology tutorials. Medical Education Online, 20(1), 27921.

Tong, A. H. K., & See, C. (2020). Informal and formal peer teaching in the medical school ecosystem: Perspectives from a student-teacher team. JMIR Medical Education, 6(2), e21869.

Zhang, J., Peterson, R. F., & Ozolins, I. Z. (2011). Student approaches for learning in medicine: What does it tell us about the informal curriculum? BMC Medical Education, 11(1), Article 87.

*Julie Chen

4/F William MW Mong Block

Faculty of Medicine Building

21 Sassoon RoadMarrakesh, Marrakesh-Safi,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Email address: juliechen@hku.hk

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.