Patients’ attitude and factors influencing the acceptance of medical students’ participation in pelvic examination

Submitted: 21 April 2021

Accepted: 7 October 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 87-97

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/OA2519

Nisakorn Deesaen1, Kongpop Sutantikorn1, Punyanuch Phonngoenchai1, Sakchai Chaiyamahapruk2 & Patcharada Amatyakul3

1Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Thailand; 2Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Thailand; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Thailand

Abstract

Introduction: Pelvic examination of patients in the department of obstetrics and gynaecology (Ob–Gyn) is an important skill for medical students. Because it involves a physical assessment of the patients’ genitalia, patients may refuse medical students to participate in the examination, affecting the medical students’ clinical skills.

Methods: This cross–sectional study was conducted at Naresuan University Hospital to determine the factors that influence the acceptance of medical student participation in the pelvic examinations. A total of 198 out–patients from the Ob–Gyn department were included. A Likert scale questionnaire was designed which featured topics on patients’ attitudes and circumstances related to medical student involvement in gynaecological procedures.

Results: The majority of outpatients (71.7%) accepted the participation of medical students in pelvic examinations. Patients with prior experiences in physical and pelvic examination by medical students had a significant impact on the patients’ acceptance (P–value<0.001). The patients’ impressions had an influence on the decision to accept students in pelvic exam participation. Approximately 40% of patients were concerned about the breach of confidentiality. However, most patients strongly agreed that allowing medical students to perform pelvic examination would benefit their medical education.

Conclusion: Most of the participants permitted medical students to participate in pelvic examinations and preferred that the medical instructor be the one to request permission. The patients’ impressions of medical students were crucial factors that significantly influence their decision whether to allow or deny them to participate in the procedure. Disclosure of confidentiality was found to be matters of concern to most patients.

Keywords: Pelvic Examination, Medical Students, Acceptance, Performance, Clinical Teaching

Practice Highlights

- Most of the patients consent to a medical student participating in a pelvic examination.

- Medical instructors should ask for patients’ permission.

- Confidentiality and privacy of patients are critical issues that must be addressed.

- Patients’ impressions and prior examination experiences by medical students influence patients’ decisions.

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical students should learn how to perform pelvic examinations on patients during clinical years. History taking, physical examination, and pelvic examination are taught during the fourth to sixth year of medical training in our curriculum. Pelvic examination is defined as the assessment of external genitalia, speculum examination of the vagina and cervix, bimanual palpation of the uterus, adnexa and sometimes rectovaginal examination. This procedure is used to screen for gynaecological diseases and cancers in asymptomatic women and to diagnose gynaecological diseases in symptomatic women. Pelvic examination differs from other physical examinations because it involves an inspection of the genitalia, which, according to studies, commonly causes anxiety, fear, embarrassment (10–80% of women), pain, and discomfort (11–60% of women) (Bloomfield et al., 2014). Some factors why patients feel uncomfortable during a physical examination by medical students are concerns about privacy, confidentiality, and embarrassment (Rizk et al., 2002). As a result, patients may refuse to allow medical students to participate in the pelvic examination, affecting the learning experience and clinical skills of medical students. Furthermore, factors related to age, race, religion, cross–cultural differences, marital status, and previous delivery may also influence the patients’ decision to allow medical students in conducting pelvic examination (Anfinan et al., 2014; McLean et al., 2010). Compared to other ethnic and religious groups, Muslim women had a higher rate of refusing medical students, particularly male students (Nicum & Karoo, 1998). During intrapartum care, approximately 50% of Hindu and Muslim patients refused to accept medical students. Sikh and Muslim patients accepted only female medical students, 41% and 40%, respectively, whereas 59% of Christian patients accepted both female and male medical students (Nicum & Karoo, 1998). However, patients’ reasons for accepting and refusing medical student participation in pelvic examination have not been established in Southeast Asia because of limited investigation.

According to the patient’s bill of rights, patients have a right to accept or refuse the medical students’ participation. They should have the opportunity to decide if they want to contribute to the medical education or decline care from medical students (Teunissen, 2018). Approximately 26% of the patients refused to have a medical student perform a pelvic examination (Fortier et al., 2006). Previous study reported that the refusal rate increased as the level of student involvement increased, from observation to history taking to examinations and procedure, particularly with digital vaginal and rectal examination (Salah et al., 2015). In contrast, some patients accepted the medical students’ participation because they wanted to contribute to the clinical training in medical education. Because of the training process, the patients felt more confident that they would receive appropriate treatments. From the literature review, most studies were conducted in developed and some Arab countries. There are limited data from women in Southeast Asia countries on the factors and attitudes that influence their decision whether they allow or refuse medical students to participate in a pelvic examination. This research aimed at studying the patients’ characteristics, influencing factors and correlation with the acceptance of medical students, which may increase the Ob–Gyn patients to participate in clinical education.

II. METHODS

This cross–sectional descriptive study was conducted at the out–patient unit of the Department (OPD) of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Naresuan University Hospital. Patients who visited Ob–Gyn department between November 2018 and May 2019 were included in the study. Patients under 20 years old, mentally or critically ill and unable to understand the questionnaire in Thai language were excluded in this study. All the participants were able to complete the consent forms and questionnaires independently, and were guaranteed anonymity.

The questionnaire was developed to evaluate 4 domains, as follows: (1) demographic and socio–economic data (age, gender, educational level, occupation and parity), (2) patient preference, (3) factors influencing patient receptivity of medical student involvement in pelvic examination (gender, hygiene, manner and demeanour, patients’ impressions of the medical students, prior experience in physical and pelvic examination), and (4) patients’ attitudes toward accepting medical students to conduct pelvic examination under supervision of medical instructors. Influencing factors and attitudes included in the questionnaire were modified based on a literature review. A 5–point Likert scale was used to determine the level of agreement (1= strongly agree; 2= agree; 3= neutral; 4= disagree; and 5= strongly disagree). The questionnaire was initially tested for content validity using the item-objective congruence (IOC) index, and then used in a pilot study on 30 patients who were not included in the study to ensure clarity and reliability.

A. Statistical Analysis

A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was created for data entry and statistical analysis. Descriptive data was presented in the form of frequency, mode, and percentage. Chi-square test was calculated for proportions. The p–value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

B. Ethical Considerations

All collected data was kept confidential, and the information was used for research only. This study was approved by Naresuan University Institutional Review Board in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

III. RESULTS

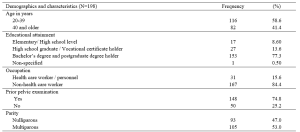

During the study period, 236 participants were recruited from the out–patient department of Ob–Gyn, but only 198 completed the questionnaire. Most of them (99.0%) were aware that Naresuan University Hospital is a primary teaching hospital of the Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University which provides clinical training for medical students and residents. The socio–demographic data of the study population are shown in Table 1. The data that supports the findings of this study are openly available at http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HBV68 (Amatyakul, 2021).

Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of the study population

From 198 participants, 71.7% accepted the medical students to participate in pelvic examination. Fifty–seven percent of the participants in the acceptor group allowed both male and female medical students, while 42.9% in the same group allowed only female medical students. The correlation between patients’ acceptance and refusal for the medical students to participate in pelvic examination showed that age, occupation and parity of the patients were not statistically different (p> 0.05). Thirty–one percent of bachelor’s degree holders and 37% of postgraduate degree holders refused the participation of medical students. The higher the patient’s educational attainment, the more likely they are to refuse a pelvic examination performed by medical students, as observed in this study. In the conduct of pelvic exam procedure, 69.3% of the patients in the acceptor group and 53.6% of the patients in the non-acceptor group felt comfortable with students present as observers. Before the students participate in a pelvic examination, most of the participants (81.4%) preferred that the medical instructors (56.6%) ask permission rather than the medical students (21.7%) or nurses (21.7%).

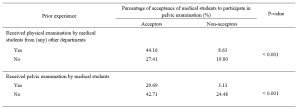

This research recorded 52.7% of the patients with prior experience of physical examination by medical students from other departments in Naresuan University Hospital. Thirty–two percent of the patients previously received pelvic examination by medical students (from our department or other medical training hospitals). Patients who had their physical examinations performed by medical students from other departments or had pelvic examinations performed by medical students had a statistically significant increase in allowing medical students to participate in pelvic examinations under the supervision of a medical instructor (Table 2).

Table 2. The correlation between the acceptance of medical student participation in pelvic examination and prior experience of pelvic examination performed by medical students.

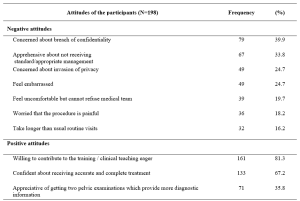

The participants’ decisions were influenced by their impressions of medical students. More than 90% of the participants believed that characteristics like manner, demeanour, cleanliness, hygiene, trustworthiness, and respect had a substantial impact on their attitudes and acceptance. Similarly, the gender of the medical students also influenced the decision of the participants (69.2%), which female students were preferred. The negative and positive attitudes of the patients related to medical student participation in pelvic examination are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. The positive and negative attitudes of the participants about medical students’ participation in pelvic examination under the supervision of medical instructors.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that 71.7% of the participants agreed to have their pelvic examinations performed by medical students. This result was comparable to the study of Western women that reported an acceptance rate ranging from 58 to 77% (Nicum & Karoo, 1998). Conversely, our acceptance rate was lower when compared to a study conducted in United Arab Emirates by Rizk et al. (2002), in which 87.1% of the out-patients in Ob-Gyn accepted the involvement of medical students. According to the results of our study, there were no statistically significant differences between acceptors and non-acceptors in terms of age, educational level, occupation, parity, or prior pelvic examination. Hartz and Beal (2000) also reported similar findings, stating that the age and education of the patients were not statistically different between the two groups. However, Rizk et al. (2002) stated that the acceptance of the patients with older age, higher parity, and higher education was statistically significant. Interestingly, there was a trend discovered in our research that patients who are highly educated were more reluctant to allow medical students in performing pelvic examination, even when supervised by medical instructors. This reluctance could be because of a strong concern for their privacy, which should be investigated further through an in-depth interview.

Prior experience of the patients receiving physical examination by medical students from other departments, and prior experience of the patients receiving pelvic examination performed by medical students significantly increased the rate of acceptance. These findings are consistent with those of Ghobain et al. (2016) who reported that a positive prior experience with a medical student was significantly related to giving medical students permission to perform a physical examination. This can be explained by the fact that these patients were already aware of the medical student involvement in performing physical examinations. Therefore, they are more likely to accept medical student participation in subsequent Ob-Gyn consultations.

One interesting finding from our study was the positive patient receptivity of medical students acting as observers during pelvic examination. Patients in approximately 70% of the acceptor group allowed other medical students to observe the examination process. Remarkably, 53.6% in the non-acceptor group was comfortable with medical students observing a pelvic examination performed by medical instructor. This would imply that even if students cannot perform pelvic examinations, they can still gain clinical knowledge through observation, and clinical instructors can take advantage of this valuable opportunity to educate their students.

Other major concern of patients is the requirement for students to obtain permission before participating in any procedures. The majority of the participants prefer that medical instructors be in charge of obtaining patient permission to allow students to perform physical examinations on their behalf. This tendency may lead to a higher rate of acceptance of student participation.

The characteristics and performance of the medical students in our study had a significant impact on patients’ decision. The external part of the female reproductive organ is a sensitive and the most private area for every woman, and patients would only allow medical students who practice good hygiene and cleanliness to participate in the examination. Furthermore, the appropriate manner and demeanour, including respectfulness and politeness toward patients, and trustworthiness of the medical students during the clinical procedure may increase the patients’ receptivity of medical students to conduct pelvic examination. Professional appearance reflecting cultural backgrounds also impacts patient preference and acceptance; therefore, medical students should dress properly (Aljoudi et al., 2016).

Several studies, including ours, found that participants felt more at ease with female students than with male students (Salah et al., 2015; Subki et al., 2018). Chang et al. (2010) reported that male students were refused by patients to participate in clinical interviews and physical examinations, including pelvic examinations. In a study conducted at Taibah University in India (Shetty et al., 2021), women significantly preferred female students during abdominal and genital examinations. As a result, it is difficult for obstetrics and gynaecology educators to consider methods of encouraging patients to accept participation of medical students, regardless of their genders.

Patients’ positive attitudes toward medical students’ participation contributed to clinical teaching, which is an important process for professional development. The patients agreed that they would receive more accurate and comprehensive treatment if they had two pelvic examinations. These details are consistent with the findings of a study conducted by Rizk et al. (2002), which revealed that 69.7% of the participants were willing to contribute to the education of students. Most participants were satisfied with the overall service because they were well informed about their care by the health care team and were actively involved in the treatment decision-making process. Like other literature (Nicum & Karoo, 1998), medical students also provided patients with useful medical information and support. Furthermore, patients strongly supported the idea that real patient encounters and practices under clinical supervision are more effective methods for improving student’s clinical skills than just mere observation or skill laboratory practice (Subki et al., 2018).

Patients’ main reasons for refusing medical students’ participation in pelvic examination were concerns about breaching their confidentiality and privacy, which were similar to a study conducted in London. According to the findings, the common reasons for patients’ uneasiness with participation of the medical students were related to privacy, receiving lower standard of care, examinations, lack of control over the student’s level of involvement, and a longer consultation time (Ryder et al., 2005). The participants in our study were also concerned about taking a longer than usual routine visit. Not only applicable in Ob-Gyn department, patients’ perceptions of students’ professionalism and respect for privacy were significantly related to the acceptance of medical students’ participation in surgical ward (Ghobain et al., 2016). Thus, all medical students must be informed about the doctor-patient relationship and the importance of maintaining patient confidentiality. Medical instructors must inform and reassure patients about their confidentiality. Before participating in any clinical teachings, medical instructors should explain to students their roles and responsibilities. To minimise patients’ feeling of discomfort, these roles and responsibilities should be conveyed and explained to them before asking for their approval.

This paper has highlighted the significance of patients’ attitudes toward medical students’ manner and demeanor, which greatly influences patients’ decision-making process. However, some limitations should be considered, such as the fact that all participants were Thai, and that the study was carried out in one of the Southeast Asia countries where data on the attitudes of female patients had not been thoroughly investigated. Since socio-demographic factors and cultural issues vary across Southeast Asia, the results of this research only represent the characteristics of the Thai population and not the entire region. Additionally, this cross-sectional study could not establish the reasons for patients’ negative attitudes toward student involvement in pelvic examination. Therefore, it is suggested that future research use in-depth interview methodology to gather more information from both the acceptor and non-acceptor groups.

V. CONCLUSION

Most of patients agreed to medical students participating in pelvic examinations and preferred medical instructors to be the persons to ask patients for permission. Essentially, patients’ confidentiality and privacy must always be safeguarded. The performance of medical students, and their observance of patient privacy and confidentiality are crucial factors in gaining the patient’s approval. Furthermore, the gender of the medical student influences the patient’s acceptance and comfort level in student’s involvement. Clinical instructors must effectively convince patients in gynaecology department to allow male medical students to perform gynaecologic procedures.

Notes on Contributors

Nisakorn Deesaen, Punyanuch Phonngoenchai, and Kongpop Sutantikorn contributed to the literature review, concept development, questionaire design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript finalisation. Sakchai Chaiyamahapruk was involved in the study design, data analysis, and manuscript finalisation. Patcharada Amatyakul contributed to the literature review, concept development, study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing and finalisation.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Naresuan University Institutional Review Board, Naresuan University, Thailand (Ethics approval number IRB 0653/60).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available in Open Science Framework repository, http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HBV68.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the nurses at the out-patient unit of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Naresuan University Hospital, for their help in distributing and collecting questionnaires from the patients.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Aljoudi, S. B., Alsolami, S. S., Farahat, F. M., Alsaywid, B., & Abuznadah, W. (2016). Patients’ attitudes towards the participation of medical students in clinical examination and care in Western Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 23(3), 172‑178. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.189133

Amatyakul, P. (2021). Proposal for patients’ attitude and factors influencing the acceptance of medical students’ participation in pelvic examination. [Data set]. Open Science Framework. http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HBV68

Anfinan, N., Alghunaim, N., Boker, A., Hussain, A., Almarstani, A., Basalamah, H., Sait, H., Arif, R., & Sait, K. (2014). Obstetric and gynecologic patients’ attitudes and perceptions toward medical students in Saudi Arabia. Oman Medical Journal, 29(2), 106-109. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2014.26

Bloomfield, H. E., Olson, A., Greer, N., Cantor, A., MacDonald, R., Rutks, I., & Wilt, T. J. (2014). Screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic, average-risk adult women: An evidence report for a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 161(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-2881

Chang, J. C., Odrobina, M. R., & McIntyre-Seltman, K. (2010). The effect of student gender on the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship experience. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(1), 87-92. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1357

Fortier, A. M., Hahn, P. M., Trueman, J., & Reid, R. L. (2006). The acceptance of medical students by women with gynaecology appointments. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 28(6), 526-530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32179-X

Ghobain, M. A., Alghamdi, A., Arab, A., Alaem, N., Aldress, T., & Ruhyiem, M. (2016). Patients’ perceptions towards the participation of medical students in their care. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 16(2), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.18295/squmj.2016.16.02.014

Hartz, M. B., & Beal, J. R. (2000). Patients’ attitudes and comfort levels regarding medical students’ involvement in Obstetrics–Gynecology outpatient clinics. Academic Medicine, 75(10), 1010-1014. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200010000-00018

McLean, M., Al Ahbabi, S., Al Ameri, M., Al Mansoori, M., Al Yahyaei, F., & Bernsen, R. (2010). Muslim women and medical students in the clinical encounter. Medical Education, 44(3), 306-315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03599.x.

Nicum, R., & Karoo, R. (1998). Expectations and opinions of pregnant women about medical students being involved in care at the time of delivery. Medical Education, 32(3), 320-324. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00205.x.

Rizk, D. E. E., Al-Shebah, A., El-Zubeir, M. A., Thomas, L. B., Hassan, M. Y., & Ezimokhai, M. (2002). Women’s perceptions of and experiences with medical student involvement in outpatient obstetric and gynecologic care in the United Arab Emirates. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecololgy, 187(4), 1091-1100. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2002.126284.

Ryder, N., Ivens, D., & Sabin, C. (2005). The attitude of patients towards medical students in a sexual health clinic. Sexually Transmitted Infection, 81(5), 437–439. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2004.014332.

Salah, A. B., Mhamdi, S. E., Bouanene, I., Sriha, A., & Soltani, M. (2015). Patients’ attitude towards bedside teaching in Tunisia. International Journal of Medical Education, 6, 201-207. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5669.ea24.

Shetty, P. A., Magazine, R., & Chogtu, B. (2021). Patient outlook on bedside teaching in a medical school. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 16(1), 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.10.002

Subki, A. H., Algethami, M. R., Addas, F. A., Alnefaie, M. N., Hindi, M. M., & Abduljabbar, H. S. (2018). Women’s perception and attitude to medical students’ participation in obstetrics and gynecology care. Saudi Medical Journal, 39(9), 902-909. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2018.9.22668

Teunissen, P. W. (2018). An inconvenient discussion. Medical education, 52(11), 1104-1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13689

*Patcharada Amatyakul

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology,

Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University,

99 Thaphoe District, Muang,

Phitsanulok, 65000 Thailand

Tel: 66-86-397-3455

Email: pamatyakul@hotmail.com

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.