Novice physiotherapists’ perceived challenges in clinical practice in Singapore

Submitted: 5 June 2024

Accepted: 30 October 2024

Published online: 1 April, TAPS 2025, 10(2), 71-81

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-2/OA3424

Mary Xiaorong Chen1, Meredith Tsz Ling Yeung1, Nur Khairuddin Bin Aron2, Joachim Wen Jie Lee3 & Taylor Yutong Liu4

1Health and Social Sciences Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2Rehabilitation Department, Jurong Community Hospital, Singapore; 3Rehabilitation Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 4Clinical Support Services Department, National University Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Transitioning from a novice physiotherapist (NPT) to an independent practitioner presents significant challenges. Burnout becomes a risk if NPTs lack adequate support for learning and coping. Despite the importance of this transition, few studies have explored NPTs’ experiences in Singapore. This study aims to investigate the transitional journey of NPTs within this context.

Methods: Conducted as a descriptive phenomenological study, researchers collected data through semi-structured online interviews with eight NPTs from six acute hospitals across Singapore. Simultaneous data analysis during collection allowed for a reflexive approach, enabling the researchers to explore new facets until data saturation. Thematic analysis was employed and complemented by member triangulation.

Results: The challenges NPTs encountered include seeking guidance from supervisors, managing fast-paced work and patients with complex conditions. Additionally, NPTs grappled with fear of failure, making mistakes and self-doubt. They adopted strategies such as assuming responsibility for learning, developing patient-focused approaches, and emotional resilience. However, a concerning trend emerged with the growing emotional apathy and doubts about their professional choice.

Conclusion: This study provides a nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by NPTs during their transition. The workplace should be viewed as a learning community, where members form mutual relationships and support authentic learning. Recommendations include augmenting learning along work activities, fostering relationships, ensuring psychological safety, and allowing “safe” mistakes for comprehensive learning.

Keywords: Novice Physiotherapist Transition in Practice, Clinical Learning and Supervision, Mentoring, Emotional Resilience and Support, Safe Learning Environment

Practice Highlights

- Gradual assumption of responsibilities helps Novice Physiotherapists (NPTs) build competence.

- Learning should be augmented along with work activities.

- It is important to support NPTs to overcome the fear of failure and self-doubt.

- NPTs’ ability to negotiate learning and emotional resilience are essential.

- Trusting relationships and a safe learning environment are essential to NPTs’ learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

Novice Physiotherapists (NPTs) are physical therapy graduates with two years or less of clinical practice, and during this transition to independent practitioners in clinical settings, they face significant challenges (Martin et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2018). Despite the expectation of competence, concerns persist regarding NPTs’ abilities in various aspects of their practice.

It was reported that the persistent challenges faced by NPTs include managing workload, handling patients with complex conditions, seeking adequate guidance, and navigating relationship dynamics (Latzke et al., 2021; Mulcahy et al., 2010). One critical issue is the oversight of NPTs’ “new” status, leading to their assignment of patient loads comparable to experienced practitioners. Consequently, NPTs find themselves under tremendous stress in managing patients with complex conditions and diverse sociocultural backgrounds beyond their abilities (Stoikov et al., 2021; Wells et al., 2021). Workloads and time constraints hinder the development of meaningful connections between NPTs and supervisors, affecting teaching and coping abilities (Rothwell et al., 2021). In the busy clinical environment, NPTs cannot solely rely on their assigned supervisors, the support from senior colleagues around them along their developmental journey is necessary. Unfortunately, studies suggest that inadequate support and guidance from senior colleagues exacerbate these challenges (Forbes et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2021; Phan et al., 2022; Stoikov et al., 2020; Te et al., 2022).

Additionally, as NPTs are inexperienced, communicating with patients, their families, and other healthcare professionals present a significant hurdle in clinical decision-making (Atkinson & McElroy, 2016). The pressure to make informed clinical decisions, drawing upon extensive knowledge and experience, contributes to job-related stress and feelings of inadequacy among NPTs (Adam et al., 2013).

Job stress-related symptoms, including exhaustion, self-doubt, and depression, further impact NPTs’ well-being. These symptoms, akin to burnout, result from a mismatch between the worker’s performance and job expectations (Brooke et al., 2020; Pustułka-Piwnik et al., 2014). Studies reveal that burnout affects approximately 65% of physiotherapists in Spain (Carmona-Barrientos et al., 2020). This is a concern as burnout was found to be correlated positively with intentions to leave the profession (Cantu et al., 2022), leading to low morale, and compromised patient service quality (Evans et al., 2022; Lau et al., 2016).

Studies suggest that ill-prepared PTs may feel inadequate and lack confidence in making decisions which can negatively influence their clinical management and support for patients’ needs. For example, PTs who lack the ability to adopt a person focused approach might not be able to manage patients with chronic lower back pain effectively (Gardner et al., 2017). Furthermore, such impacts are subtle, difficult to pinpoint, and can result in poor care quality, low patient satisfaction and staff morale (Gardner et al., 2017; Holopainen et al., 2020; Marks et al., 2017).

In Singapore, the healthcare system is bifurcated into public and private sectors. Public hospitals, which fall under government ownership (Ministry of Health, 2023), are pivotal in delivering healthcare services. These hospitals are organised into three distinct clusters, each serving specific regions within the country. Table 1 for a comprehensive list of public hospitals categorised by their respective clusters.

|

Healthcare Clusters |

Hospitals |

|

National Healthcare Group (NHG) |

Tan Tock Seng Hospital |

|

|

Khoo Teck Puat Hospital IMH (Institute of Mental Health) |

|

National University Health System (NUHS) |

National University Hospital |

|

|

Ng Teng Fong General Hospital |

|

|

Alexandra Hospital |

|

SingHealth |

Singapore General Hospital |

|

|

Changi General Hospital |

|

|

Sengkang General Hospital |

|

|

National Heart Centre |

|

|

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital |

Table 1. Public hospitals in Singapore

At the beginning of 2022, Singapore had 165 physiotherapists under conditional registration, with 97 (59.51%) employed by public hospitals (Allied Health Professions Council, 2022). Novice Physiotherapists (NPTs) require close supervision and guidance from their clinical mentors/supervisors. During their initial phase, all NPTs undergo a 13-month conditional registration before qualifying for a full registration status. With an average 200 PT students graduate from the Singapore Institute of Technology each year, coupled with the NPTs under conditional registration, the supervisory tasks shared by the limited pool of PT Supervisors are tremendous. Besides their supervisory roles, PT supervisors are also clinically responsible to managing patients and workplace administrations.

A recent study conducted in Singapore explored the perspectives of allied health practitioners, including physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and radiographers, regarding clinical supervision in tertiary hospitals (Lim et al., 2022). The findings revealed that newly qualified allied health practitioners often faced challenges related to insufficient clinical supervision, emotional support, and professional guidance from their supervisors. Contributing factors included time constraints and staffing limitations (Lim et al., 2022). These findings underscore the need for a deeper understanding of the experiences encountered by NPTs during their early clinical practice.

Despite the significance of this issue, no further research has specifically explored the clinical experiences of NPTs in Singapore. Among NPTs, those working in acute public hospitals constitute a compelling subgroup, representing 59.51% of the NPT workforce. Additionally, acute public hospitals provide multidisciplinary services, making them ideal settings for studying the challenges faced by NPTs. Therefore, this study aims to delve into the experiences of NPTs within Singapore’s acute public hospitals.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design

The study employed a descriptive phenomenological approach to understand participants’ lived experiences (Neubauer et al., 2019). In this approach, researchers intentionally set aside their preconceptions and assumptions in this method, allowing the data to speak for itself (Shorey & Ng, 2022). Giorgi (1997) highlights that descriptive phenomenology is particularly well-suited for phenomena that lack extensive literature evidence. Given the limited research on NPTs’ transitional experiences in Singapore, adopting descriptive phenomenology is appropriate for this study.

B. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board (Approval number: 2022033). The participant information sheet was emailed to prospective participants for recruitment. Written informed consent was obtained. All researchers had no authoritative relations with the participants. Participants were assured that their participation was anonymous and voluntary.

C. Participant Recruitment

Adopting a convenient and snowballing sampling approach, the researchers approached NPTs and sought referrals for further recruitment. The inclusion criteria were: (1) NPTs who had less than two years of clinical practice after graduation; (2) NPTs who were working in acute public hospitals. The exclusion criteria were: (1) NPTs who had prior working experience in healthcare; (2) NPTs who were not working in acute public hospitals.

The recruitment email sought voluntary return of information such as place of practice, date of employment, alma mater, and previous work experience in healthcare. A follow-up email was sent to arrange for the online semi-structured interview. Eight participants from six acute public hospitals were included in the study.

|

Participant* |

Gender |

Race |

Age (Years) |

Hospital * |

Length of Employment |

|

Alpha |

Female |

Chinese |

26 |

Hospital G |

348 days |

|

Beta |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital E |

419 days |

|

Charlie |

Male |

Malay |

27 |

Hospital I |

310 days |

|

Delta |

Female |

Chinese |

27 |

Hospital K |

432 days |

|

Epsilon |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital G |

452 days |

|

Foxtrot |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital G |

515 days |

|

Golf |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital E |

531 days |

|

Hotel |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital A |

531 days |

Table 2. Participant demographic information

* Participants’ names and hospitals are given pseudonyms to maintain anonymity.

D. Data Collection

Data were collected by researchers NK, JL and TL, who were final-year physiotherapy students. The interview guide was developed based on the literature review and validated by MC and MY, both are experienced in clinical supervision. The researchers conducted pilot interviews to test the interview guide and their approaches. The interview guide is presented in Appendix 1.

With the semi-structured approach, the researchers had the flexibility to follow up on questions. Open-ended questions were used to mitigate the potential issues of over-leading the discussion (Green & Thorogood, 2018). MC provided feedback to NK, JL and TL after each interview. The researchers kept a reflexive journal to record their thoughts, feelings, knowledge and perceptions of the research process (Chan et al., 2013).

Interviews were conducted between July and November 2022 over Zoom. The interview recordings were transcribed. The research team reviewed the video recordings and the aspects needed to follow up with the next interview (Ryan et al., 2009). Data saturation was reached by the fifth interview. Three more interviews were done to ensure no new findings. Each interview lasted between 33 to 110 minutes, with a mean duration of 77 minutes.

E. Data Analysis

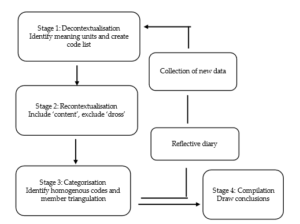

The data were analysed using an inductive approach with no predetermined structure, framework, or theory simultaneously with data collection (Burnard et al., 2008). The four stages include decontextualisation, recontextualisation, categorisation, and compilation (Bengtsson, 2016) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data analysis process (Adapted from Bengtsson, 2016)

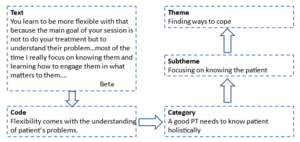

For decontextualisation, NK, JL and TL read interview transcripts and code the text into smaller meaning units independently. A meaningful unit is the smallest unit that can be defined as sentences or paragraphs containing aspects related to one another and addressing the aim of the study (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. An example of the analysis process

For recontextualisation, the researchers read the original text alongside the final list of codes. The unmarked text was included if it was relevant to the research question. For unrelated text, it was labelled as “dross” and excluded (Bengtsson, 2016). Discrepancies were resolved through consulting MC and MY. Codes were reviewed to identify patterns and similarities and then categorised into themes and sub-themes. The rigor of analysis was ensured through researcher triangulation (Lao et al., 2022). Qualitative data analysis software Quirkos was used to assist with the analysis.

III. RESULTS

From the data analysis based on the dataset (Chen, 2023), two themes were synthesised as shown in Table 3.

|

Themes |

Subthemes |

|

Challenges from multiple aspects |

Challenges in getting guidance from the Supervisors |

|

Challenges from the pace and nature of the work |

|

|

Challenges from patient |

|

|

Fear and self-doubt |

|

|

Finding ways to cope |

Be intentional and responsible in learning |

|

Focusing on knowing the patient and managing time |

|

|

Emotional resilience and emotional apathy |

Table 3. Themes and subthemes

These themes are supported by subthemes depicting the multiple dimensions of challenges and NPTs’ coping strategies.

A. Challenges from Multiple Aspects

This theme is supported by four sub-themes, indicating NPTs encountered challenges from many aspects of their practice context.

1) Challenges in getting guidance from the supervisors: NPTs reported that they were scheduled to manage patients independently soon after their orientation, often at a different location from their supervisors. Working in different locations to manage different groups of patients posed difficulties for NPTs to learn from their supervisors. Even if the clinics were nearby, their supervisors had to stop their clinics temporarily to guide the NPTs, which caused the accumulation of patients on the waiting list and prolonged clinical hours. Knowing this would happen, NPTs were reluctant to consult their supervisors.

Furthermore, NPTs might not be familiar with the patient’s medical conditions, posing challenges for them to ask questions. Some of them had been ridiculed for asking questions deemed “inappropriate”. For example, the supervisor might pass a remark such as “This kind of question you also ask!” or the supervisor ignores their questions. As a result, NPTs felt they were left alone to struggle with the feeling of inadequacy and anxiety.

2) Challenges from the pace and nature of the work: NPTs operated within a tight timeframe, similar to the experienced colleagues’ schedule, with only 20 minutes allocated for each patient. This brevity limited their ability to build rapport with patients and to discuss treatment options. The rapid succession of patients, where one consultation immediately followed another, left NPTs mentally exhausted and hindered effective patient management.

Meanwhile, NPTs were required to record their consultations with patients promptly. However, unfamiliarity with the items on the documentation often led to incomplete records. The accumulation of unfinished document recordings throughout the day left NPTs with a backlog to address during their shifts. By the end of the day, recalling specific patient details became challenging.

Additionally, NPTs as the “gatekeepers”, must assess patients’ fitness for discharge. Balancing medical guidelines, patient readiness and family expectations are delicate. NPTs occasionally found themselves at odds with doctors’ decisions when they believed a patient’s condition was not ready for discharge. This stance can lead to stress and feelings of being disregarded. NPT Hotel shared:

“We do have our reasoning and know why we do certain things. So sometimes it is frustrating when you bring it across for the doctor, and they don’t take you seriously.”

3) Challenges from patients: Many patients, particularly the elderly, communicate primarily in dialects in Singapore. For NPTs who are educated in English, understanding these dialects could be akin to deciphering a foreign language, hindering accurate assessment and treatment planning. This challenge creates another layer of stress for NPTs to understand the patients and tailor the interventions. Understandably patients’ outcomes were not always predictable. However, NPTs could be blamed when patients experience setbacks after discharge. The weight of unjust accusations took a toll on NPTs’ mental well-being. NPT Charlie shared such an encounter:

“I assessed the patient, and he met all the outcome measures for discharge. The day he went home, he fell! The patient’s family was angry and made a complaint. It wasn’t my fault. He didn’t take his medication, and he is suffering from Parkinson’s Disease…it is a very mentally taxing job…You know, when I called the family, they yelled at me… it is emotionally draining…”

4) Fear and self-doubt: NPTs realised that their knowledge was but a drop in the vast ocean of medical expertise and they started to question their abilities. Each patient encounter became a tightrope walk – a delicate balance between thoroughness and efficiency. Fearing they might miss crucial details, NPTs reported to work early and pored over each patient’s medical record to prepare themselves. Yet, despite their diligence, inadequacy gnawed at their confidence.

Practicing under a conditional license, the aim to achieve competence is like a ticking clock, NPTs must prove their worth within a limited timeframe. The fear of failure loomed large and each misstep felt like a step toward the abyss. NPT Golf shared his feeling of inadequacy:

“You take a long time to read the patient’s medical record to screen them, much slower than your seniors, but you will still miss out important things… you see each patient a bit longer…you spend longer time on documentation (recording), then you have many days with extended working hours…”

B. Finding ways to cope

NPTs adopted various approaches to cope with their work demand, some of the methods helped while some were not so.

1) Be intentional and responsible in learning: Recognising the limitations of case scenario-based classroom learning, some NPTs proactively learn through their daily work. NPT Golf shared the importance of such learning:

“Discharge planning and prognostication required a lot of clinical reasoning, which is very difficult to teach in a lecture. You have to see the real patient to know their background and the cause of the condition and to discuss with the patient their rehab potential.”

NPTs learned to present their clinical reasoning when asked questions, to show that they were proactive in learning. Some NPTs maintained a question log throughout the day and negotiated a dedicated time slot to consult their supervisors after work. Another strategy was to review the next day’s patient list, anticipate difficulties they might encounter, and seek opportunities to see the selected patients with supervisors. With this arrangement, NPTs can learn on the job and get immediate feedback.

2) Focusing on knowing the patient and managing time: NPTs acknowledged that patient care extends beyond physical assessment. They delved into patients’ medical records to know the medications the patient is on, their side effects, and the underlying conditions. By meticulously assessing patients, NPTs gained a holistic understanding of their health status. This knowledge informs treatment decisions and ensures patient safety. Delta’s example underscores this approach:

“Knowing a patient’s medication regimen and potential side effects allows us to anticipate complications. For instance, abdominal bloating from a specific medication may impact diaphragm movement, leading to patient agitation.”

Meanwhile, NPTs recognised the pivotal role of families in patient care. They actively sought input from family members to understand cultural nuances and contextual factors. As each patient comes with unique physical limitations and emotional stressors, understanding patients’ goals, fears, and preferences is paramount. Beta emphasises:

“Our sessions aren’t solely about treatments. We invest time in understanding patients’ problems and engaging them and their families in meaningful conversations…most of the time I focus on knowing them and learning how to engage them…(know) what matters to them.”

NPTs recognise that time is a precious resource. They make deliberate choices to maximise their time at work. For example, they shorten their lunch breaks to catch up with workload demands. They took quick notes or used visual reminders (such as photographs) to aid memory in recording. NPTs also learned to quickly jot down relevant details before the next patient consultation to ensure the accuracy of document recording and continuity of care.

3) Emotional resilience and emotional apathy: NPTs need to go through a series of skills competency assessments. When faced with assessment failure, being resilient is helpful. Delta explained:

“I think a good mindset would be to ask myself ‘Why did I fail this competency (assessment)? Was it because I did not maintain sterility? Did I do something wrong?’…the next time I will remember to correct my mistakes…then I realised that ‘oh, it (failure) doesn’t matter. I can learn and do (it) again…”

Some, like NPT Foxtrot, experience sadness and grief when the patients they care for deteriorate and die. To maintain emotional resilience, NPTs used strategies such as “letting go”, “emotional detachment” and “getting enough sleep” to avoid intense emotions. They also get support from peers, friends, and family.

However, some NPTs worried about the loss of enthusiasm and became too detached emotionally by “seeing every patient as a condition or a case” and transformed patient encounters into mechanical routines. They called it “emotional apathy” or “turned off”.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study is the first to explore the experiences of newly graduated physiotherapists (NPTs) during their initial two years of clinical practice in Singapore. The findings indicate that NPTs encounter several challenges during this transition, such as obtaining adequate guidance from supervisors, managing patients with complex conditions, and coping with demanding workloads. These findings align with existing literature evidence, suggesting that the challenges faced by NPTs in Singapore are comparable to those encountered in other countries.

Furthermore, this research provides a nuanced understanding of the factors contributing to NPTs’ transitional challenges. Workplace learning can be difficult due to tight schedules, and multiple members in the process with various roles and responsibilities. According to Billett et al. (2018), the workplace is the most authentic learning place and workplace learning has to be intentional. Firstly, there is a need to set up the curriculum. This happens only when learning is viewed as an integral part of work where the use of knowledge, roles, and processes are continuously negotiated. Therefore, NPTs, their supervisors, and coworkers need to discuss learning opportunities along the pathways of work to plan activities that augment learning.

Secondly, there is a need to enable effective learning facilitated by experts within the workplace. This means the workplace is a learning community where all members share a common purpose and are willing to help one another learn. The responsibility of teaching and guiding the NPTs are shared responsibilities, members can take part in teaching in their expertise.

Thirdly, there is a need to consider individual factors and construct learning according to what learners know, can do and value. For this to happen, clinical experts, such as supervisors and senior members need to have conversations with the NPTs to help them identify learning needs, as NPTs sometimes do not know what they do not know.

However, revealing one’s learning needs can leave one feeling vulnerable; thus, trust relationships and psychological safety are crucial in the workplace. Sellberg et al. (2022) suggested that supervisors can initiate meetings to get to know NPTs and share their own learning experiences as novices. NPTs need to feel safe to share what they know, can do, and need to learn.

Initial placement of NPTs in the same clinic with their supervisors can foster relationships, confidence, and learning. Several clinical supervision strategies, including understanding clinical situations, aligning learning objectives with roles, discussing goals with learners, and actively observing and debriefing learners (Hinkle et al., 2017), can be recommended to NPTs’ supervisors and senior members in the community. Additionally, dedicated time for supervisors and NPTs to discuss and reflect on work and learning, or even engage in social activities, can help boost relationships.

Clinical supervisors should be carefully selected and trained in supervision skills. A research study suggested that they should be knowledgeable, good communicators, approachable, interested in building relationships with learners, and capable of providing feedback and tailored guidance (Alexanders et al., 2020). A meta-analysis by Nienaber et al. (2015) suggests that supervisor attributes, subordinate attributes, interpersonal processes, and organisational characteristics influence relationship building. Therefore, efforts for relationship building should not only be at the individual level but also the organisational level. Organisations can provide targeted training to supervisors to empower them with the knowledge and skills to mentor NPTs.

This study also highlights the dilemma NPTs face between the fear of making mistakes and the responsibility of learning. Such fear is not unique to NPTs as studies suggest novice nurses also report similar anxieties during the transition (Cowen et al., 2016; Ten Hoeve et al., 2018). Singapore studies on novice nurses (Chen et al., 2021) and nursing students (Leong & Crossman, 2016) highlighted similar fear, as making mistakes in healthcare is taboo. In their effort to avoid mistakes, NPTs adopt a “safe” approach and avoid opportunities that could significantly enhance their competence and abilities.

Fear of failure limits learning, while comprehensive learning requires a degree of autonomy and the safety to make mistakes. There is a need to change attitudes towards “safe” mistakes. Harteis et al. (2008) suggested that allowing workers to learn from mistakes at work can maximise learning and cooperativeness. Eskreis-Winkler and Fishbach (2019) reviewed five studies on learning from failure, emphasising that effective learning happens from the feedback of mistakes and such feedback must separate failure from personal judgment. Creating a psychologically safe learning environment, where learners feel safe to ask questions and learn from mistakes, is essential (Edmondson, 2023).

NPTs also faced challenges in their interactions with other healthcare professionals and patients. Patton et al. (2018) highlighted that the clinical setting is a multidimensional learning space where environmental factors, the nature of the work, and member interactions shape clinical learning. Hence educators at higher learning institutes can design learning using role play by engaging students, clinical supervisors, other healthcare professionals, and standardised patients to learn different roles and perspectives.

This study is the first to explore the transitional experiences of newly graduated physiotherapists (NPTs) in Singapore. It is important to note that NPTs from community and private settings were not represented. Future research should investigate the transitional experiences of NPTs in tertiary and community care settings to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

This study highlighted several critical aspects of NPTs’ transition, including fear, emotional apathy, intention in learning, and relationship building with supervisors and patients. However, these areas warrant further exploration to deepen our understanding. Additionally, incorporating the perspectives of clinical supervisors could complement the current findings in facilitating NPTs’ learning in transition.

V. CONCLUSION

This study provides a nuanced understanding of the challenges encountered by newly graduated physiotherapists (NPTs) and their coping strategies during their transition. The findings underscore the necessity for a well-structured clinical supervision setting, a safe learning environment, well-trained clinical supervisors, an emotional support framework for NPTs and clinical roleplay training in schools. It is also crucial to cultivate NPTs’ abilities to learn and to develop meaningful relationships with supervisors and patients.

Notes on Contributors

Author MC provided research conceptualisation and methodology guidance, performed data analysis, validated findings and wrote the manuscript. Author MY provided methodology guidance, validated findings and provided feedback to the writing of the manuscript. Author NK, JL and TL reviewed the literature, developed the methodological framework for the study, and performed data collection and data analysis as their final-year project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Singapore Institute of Technology Ethics Committee (Project 2022033).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://figshare.com/s/4f1ecf288001750e72 e4

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the physiotherapists who participated in the study.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Declaration of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest. Participation in the research was voluntary and anonymous. Novice Physiotherapists were assured that their participation or nonparticipation would not affect their work performance appraisal.

References

Adam, K., Peters, S., & Chipchase, L. (2013). Knowledge, skills and professional behaviours required by occupational therapist and physiotherapist beginning practitioners in work-related practice: A systematic review. Australian Ooccupational Therapy Journal, 60(2), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12006

Allied Health Professions Council. (2022). Allied Health Professions Council Annual Report 2022. AHPC. https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/announcements/2022_ahpc-annual-report_v7-(final).pdf

Alexanders, J., Chesterton, P., Gordon, A., Alexander, J., & Reynolds, C. (2020). Physiotherapy student’s perceptions of the ideal clinical educator [version 1]. MedEdPublish, 9(254). https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000254.1

Atkinson, R., & McElroy, T. (2016). Preparedness for physiotherapy in private practice: Novices identify key factors in an interpretive description study. Manual Therapy, 22, 116-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.10.016

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8-14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Billett, S., Harteis, C., & Gruber, H. (2018). Developing occupational expertise through everyday work activities and interactions. In K. A. Ericsson, R. R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, & A. M. Williams (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (2 ed., pp. 105-126). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316480748.008

Brooke, T., Brown, M., Orr, R., & Gough, S. (2020). Stress and burnout: Exploring postgraduate physiotherapy students’ experiences and coping strategies. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), Article 433. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02360-6

Burnard, P., Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Analysing and presenting qualitative data. British Dental Journal, 204(8), 429-432. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

Cantu, R., Carter, L., & Elkins, J. (2022). Burnout and intent-to-leave in physical therapists: A preliminary analysis of factors under organisational control. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 38(13), 2988-2997. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2021.1967540

Carmona-Barrientos, I., Gala-León, F. J., Lupiani-Giménez, M., Cruz-Barrientos, A., Lucena-Anton, D., & Moral-Munoz, J. A. (2020). Occupational stress and burnout among physiotherapists: A cross-sectional survey in Cadiz (Spain). Human Resources for Health, 18, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00537-0

Chan, Z. C. Y., Fung, Y.-l., & Chien, W.-t. (2013). Bracketing in phenomenology: Only undertaken in the data collection and analysis process? Qualitative Report, 18(30), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1486

Chen, M. X. (2023). Novice physiotherapists’ first-year clinical practice in Singapore [Data set]. Figshare. https://figshare.com/s/4f1ecf288001750e72e4

Chen, M. X., Newman, M., & Park, S. (2021). Becoming a member of a nursing community of practice: Negotiating performance competence and identity. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 76(1), 164-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2021.2015715

Cowen, K. J., Hubbard, L. J., & Hancock, D. C. (2016). Concerns of nursing students beginning clinical courses: A descriptive study. Nurse Education Today, 43, 64-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt. 2016.05.001

Edmondson, A. C. (2023). Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well. Simon and Schuster.

Eskreis-Winkler, L., & Fishbach, A. (2019). Not learning from failure—the greatest failure of all. Psychological Science, 30(12), 1733-1744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619881133

Evans, K., Papinniemi, A., Vuvan, V., Nicholson, V., Dafny, H., Levy, T., & Chipchase, L. (2022). The first year of private practice – New graduate physiotherapists are highly engaged and satisfied but edging toward burnout. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 40(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2022.2113005

Forbes, R., Lao, A., Wilesmith, S., & Martin, R. (2021). An exploration of workplace mentoring preferences of new‐graduate physiotherapists within Australian practice. Physiotherapy Research International, 26(1), Article e1872. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1872

Gardner, T., Refshauge, K., Smith, L., McAuley, J., Hübscher, M., & Goodall, S. (2017). Physiotherapists’ beliefs and attitudes influence clinical practice in chronic low back pain: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Journal of Physiotherapy, 63(3), 132-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.20 17.05.017

Giorgi, A. (1997). The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 28(2), 235-260. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916297X00103

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research. Sage.

Harteis, C., Bauer, J., & Gruber, H. (2008). The culture of learning from mistakes: How employees handle mistakes in everyday work. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(4), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2008.07.003

Hinkle, L. J., Fettig, L. P., Carlos, W. G., & Bosslet, G. (2017). Twelve tips for just in time teaching of communication skills for difficult conversations in the clinical setting. Medical Teacher, 39(9), 920-925. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1333587

Holopainen, R., Simpson, P., Piirainen, A., Karppinen, J., Schütze, R., Smith, A., O’Sullivan, P., & Kent, P. (2020). Physiotherapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: A systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Pain, 161(6), 1150-1168. https://journals.lww.com/pain/fulltext/2020/06000/physiotherapists__perceptions_of_learning_and.5.aspx

Jones, A., Ingram, M. E., & Forbes, R. (2021). Physiotherapy new graduate self-efficacy and readiness for interprofessional collaboration: A mixed methods study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(1), 64-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13 561820.2020.1723508

Lao, A., Wilesmith, S., & Forbes, R. (2022). Exploring the workplace mentorship needs of new-graduate physiotherapists: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice, 38(12), 2160-2169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2021.1917023

Latzke, M., Putz, P., Kulnik, S. T., Schlegl, C., Sorge, M., & Mériaux-Kratochvila, S. (2021). Physiotherapists’ job satisfaction according to employment situation: Findings from an online survey in Austria. Physiother Research International, 26(3), e1907. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1907

Lau, B., Skinner, E. H., Lo, K., & Bearman, M. (2016). Experiences of physical therapists working in the acute hospital setting: Systematic Review. Physical Therapy, 96(9), 1317-1332. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20150261

Leong, Y. M. J., & Crossman, J. (2016). Tough love or bullying? New nurse transitional experiences. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(9-10), 1356-1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13225

Lim, B., Cook, K., Sutherland, D., Weathersby, A., & Tillard, G. (2022). Clinical supervision in Singapore: Allied health professional perspectives from a two-round delphi study, 20(1), Article 12. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2022.2103

Marks, D., Comans, T., Bisset, L., & Scuffham, P. A. (2017). Substitution of doctors with physiotherapists in the management of common musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review. Physiotherapy, 103(4), 341-351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio. 2016.11.006

Martin, R., Mandrusiak, A., Lu, A., & Forbes, R. (2020). New‐graduate physiotherapists’ perceptions of their preparedness for rural practice. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28(5), 443-452. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12669

Ministry of Health. (2023). Health Facilities. Ministry of Health. https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/health-facilities

Mulcahy, A. J., Jones, S., Strauss, G., & Cooper, I. (2010). The impact of recent physiotherapy graduates in the workforce: A study of Curtin University entry-level physiotherapists 2000-2004. Australian Health Review, 34(2), 252-259. https://doi.org/10.1071/ AH08700

Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T., & Varpio, L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

Nienaber, A.-M., Romeike, P. D., Searle, R., & Schewe, G. (2015). A qualitative meta-analysis of trust in supervisor-subordinate relationships. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(5), 507-534. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2013-0187

Patton, N., Higgs, J., & Smith, M. (2018). Clinical learning spaces: Crucibles for practice development in physiotherapy clinical education. Physiother Theory Practice, 34(8), 589-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2017.1423144

Phan, A., Tan, S., Martin, R., Mandrusiak, A., & Forbes, R. (2022). Exploring new-graduate physiotherapists’ preparedness for, and experiences working within, Australian acute hospital settings. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 39(9), 1918-1928. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2022.2059424

Pustułka-Piwnik, U., Ryn, Z. J., Krzywoszański, Ł., & Stożek, J. (2014). Burnout syndrome in physical therapists – Demographic and organisational factors. Medycyna pracy. Workers’ Health and Safety, 65(4), 453-462. https://doi.org/10.13075/mp.5893.00038

Rothwell, C., Kehoe, A., Farook, S. F., & Illing, J. (2021). Enablers and barriers to effective clinical supervision in the workplace: A rapid evidence review. BMJ open, 11(9), e052929. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052929

Ryan, F., Coughlan, M., & Cronin, P. (2009). Interviewing in qualitative research: The one-to-one interview. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 16(6), 309-314. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.6.42433

Sellberg, M., Halvarsson, A., Nygren-Bonnier, M., Palmgren, P. J., & Möller, R. (2022). Relationships matter: A qualitative study of physiotherapy students’ experiences of their first clinical placement. Physical Therapy Reviews, 27(6), 477-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2022.2106671

Shorey, S., & Ng, E. D. (2022). Examining characteristics of descriptive phenomenological nursing studies: A scoping review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(7), 1968-1979. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15244

Stoikov, S., Gooding, M., Shardlow, K., Maxwell, L., Butler, J., & Kuys, S. (2021). Changes in direct patient care from physiotherapy student to new graduate. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 37(2), 323-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2019.1628138

Stoikov, S., Maxwell, L., Butler, J., Shardlow, K., Gooding, M., & Kuys, S. (2020). The transition from physiotherapy student to new graduate: Are they prepared? Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 38(1), 101-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1744206

Te, M., Blackstock, F., Liamputtong, P., & Chipchase, L. (2022). New graduate physiotherapists’ perceptions and experiences working with people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 38(6), 782-793. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1799459

Ten Hoeve, Y., Kunnen, S., Brouwer, J., & Roodbol, P. F. (2018). The voice of nurses: Novice nurses’ first experiences in a clinical setting. A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7-8), e1612-e1626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14307

Wells, C., Olson, R., Bialocerkowski, A., Carroll, S., Chipchase, L., Reubenson, A., Scarvell, J. M., & Kent, F. (2021). Work readiness of new graduate physical therapists for private practice in Australia: Academic faculty, employer, and graduate perspectives. Physical Therapy, 101(6), pzab078. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab078

Wright, A., Moss, P., Dennis, D. M., Harrold, M., Levy, S., Furness, A. L., & Reubenson, A. (2018). The influence of a full-time, immersive simulation-based clinical placement on physiotherapy student confidence during the transition to clinical practice. Advances in Simulation, 3(1), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-018-0062-9

*Mary Xiaorong Chen

10 Dover Drive

Singapore 138680

Email: Mary.chen@singaporetech.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.