Lived experiences of mentors in an Asian postgraduate program: Key values and sociocultural factors

Submitted: 21 February 2024

Accepted: 16 July 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 26-32

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/OA3255

Aletheia Chia1, Menghao Duan1 & Sashikumar Ganapathy2,3

1Paediatric Medicine, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 2Department of Emergency Medicine, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 3Paediatric Academic Clinical Programme, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Mentoring is an essential component of post-graduate medical training programs worldwide, with potential benefits for both mentors and mentees. While factors associated with mentorship success have been described, studies have focused on intrapersonal characteristics and are largely based in Western academic programs. Mentorship occurs in a broader environmental milieu, and in an Asian context, cultural factors such as respect for authority, hierarchy and collectivism are likely to affect mentoring relationships. We aim to explore the lived experience of mentors within an Asian postgraduate medical training program, and thus identify challenges and develop best practices for effective mentoring.

Methods: 14 faculty mentors from a post-graduate paediatric residency program were interviewed between October 2021 to September 2022. Data was collected through semi-structured one-on-one interviews, with participants chosen via purposeful sampling. Qualitative analysis was done via a systematic process for phenomenological inquiry, with interviews thematically coded separately by 2 independent reviewers and checked for consistency.

Results: 4 main thematic concepts were identified: “professional, but also personal”, “respect and hierarchy”, “harmony and avoidance of open conflict” and the “importance of trust and establishing a familial relationship”. Mentors also highlighted the value of structure in Asian mentoring relationships.

Conclusion: Cultural factors, which are deeply rooted in social norms and values, play an important role in shaping mentoring relationships in an Asian context. Mentoring programs should be tailored to leverage on the unique cultural norms and values of the region in order to promote career growth and personal development of trainees and mentors.

Keywords: Medical Education, Graduate Medical Education, Professional Development

Practice Highlights

- Cultural factors are key in shaping Asian mentoring relationships.

- This includes being ‘professional, but also personal’, ‘respect and hierarchy’, ‘harmony and avoidance of open conflict’ and the “importance of trust and establishing a familial relationship’.

- Mentoring programs should be tailored to leverage on the unique local cultural norms and values.

I. INTRODUCTION

Mentoring is an essential component of post-graduate medical training programs worldwide. Mentorship is a reciprocal, interdependent relationship between a mentor (often a faculty member who is senior and experienced) and a mentee (beginner or protégé in the field) (Sambunjak et al., 2006). Benefits for mentees include aiding career preparation, development of clinical and communication skills, independence, and preventing burnout (Flint et al., 2009; Ramanan et al., 2006; Spickard et al., 2002). Mentors derive satisfaction from aiding the next generation, motivation for ongoing learning and institutional recognition (Burgess et al., 2018).

Variables associated with mentoring success have been described. Key components identified by mentors and mentees are communication and accessibility, caring personal relationship, mutual respect and trust, exchange of knowledge, independence and collaboration, and role modelling (Eller et al., 2014). Personality differences, lack of commitment, conflict of interests and mentor’s lack of experience can contribute to unsuccessful mentoring relationships (Straus et al., 2013).

However, mentorship occurs in a broader environmental milieu. Sambunjak (2015) described an ecological model of mentoring in academic medicine, with a first societal level of cultural, economic and political factors; a second institutional level of system- and organisation-related factors, and a third level of intrapersonal and interpersonal characteristics. Studies on mentorship have mainly focused on the latter and are situated in Western academic programs. In an Asian context, cultural factors such as respect for authority, hierarchy and collectivism may affect mentoring relationships (Chin & Kameoka, 2019). Trainees may show more deference to their mentors, and mentors may be more directive than collaborative. An Asian study surveying Doha’s postgraduate paediatric program found 75% mentees unsatisfied in their mentoring relationship (Khair et al., 2015).

We aim to explore the lived experience of mentors within an Asian postgraduate medical training program, and thus identify the challenges faced by trainees and mentors and develop best practices for effective mentoring.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design

This qualitative study is based on an interpretive phenomenological approach of participants’ lived experiences in their mentoring relationships. Through close examination of individual experiences, phenomenological analysis seeks to capture the meaning and common features, or essences, of an experience (Starks & Trinidad, 2007).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted. The interview guide was designed to follow a pre-determined structure whilst allowing for flexibility in probing. It was based on insights from literature on key socio-cultural determinants of successful mentoring relationships. Data was collected until saturation, with no new themes emerging.

B. Setting

We studied a paediatric residency program of a tertiary academic centre in Singapore, with 47 residents and 180 faculty members.

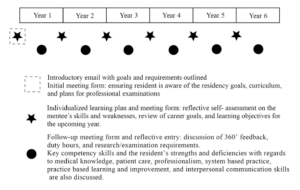

A formal mentorship program (Figure 1) has been in place since 2010. Residents indicate preferred faculty mentors at the start of residency, and are advised to consider specialty of interest, characteristics, and gender. Matches are subject to availability, review by the residency program, and mentor acceptance. Residents have one formal mentor throughout the 6 years unless the mentorship is terminated by mutual agreement between mentor and mentee.

Figure 1. Mentorship program structure, with suggested meeting timings and requisite forms. Meetings are required minimally 6-monthly and are scheduled on an ad-hoc basis by the mentor and mentee.

C. Participants

Purposive sampling to identify mentors in the residency program who would provide comprehensive and relevant insights. Considerations included age, gender, race, and years of mentorship and faculty experience. Study members and their mentors were excluded.

Study information sheets were provided to participants with assurance of confidentiality, and written informed consent obtained from each participant. The study was approved by the SingHealth Institution Review Board.

D. Analysis

Qualitative analysis was done via a systematic process for phenomenological inquiry (Creswell & Creswell, 2022), whereby statements were analysed and categorised into clusters of meaning that represent phenomenon of interest. Transcripts were interpreted independently by 2 reviewers (AC, MD) and reviewed by a 3rd study member (SG). Iterative data analysis and collection was performed, with coding done after each interview to identify new themes and inform further interviews.

III. RESULTS

We interviewed 14 mentors from October 2021 to September 2022. 8 were male and 6 were female. 12 were Chinese, 1 Indian, and 1 of other ethnicity. This was representative of faculty demographics. Mentors had two to eleven years of mentorship experience within the program, and one to five existing and prior mentees.

Mentors described their lived experiences in their mentoring journey, providing insights into key values and their relationships’ evolution. 4 main thematic concepts were identified: “professional, but also personal”, “respect and hierarchy”, “avoidance of open conflict” and the “importance of trust”. Mentors also highlighted the value of structure in Asian mentoring relationships.

A. Professional, but also Personal

All mentors agreed that the relationship was predominantly professional, with their key role being that of professional and career guidance. They described their roles as:

“Guidance through difficult decisions or challenges” (#1), “leaning the real world of medicine” (#2), “driving professional development” (#12) and providing “timely and wise advice to support the journey” (#13)

Relationships “predominantly focused on professional or educational aspects… as that’s what it was meant to be” (#10), and were “mainly limited to career-related matters (#11)”.

However, many also identified personal connection as key. While the focus was primarily professional, awareness of personal or emotional aspects aided in understanding their mentors to further professional development and psycho-emotional growth. This included sharing of family lives, and emotional difficulties faced at work.

As the journey progresses it becomes a lot more about the psycho-emotional aspect, and about their mental health and personal well-being. (#1)

A lot of time is spent discussing family issues. If we knew more about the personal life of our mentee it’s so much easier to tailor the advice based on the individual’s unique circumstances. (#3)

A minority of mentors kept their relationship strictly professional and preferred not to talk about aspects outside of work, as it was ‘easier’ (#10) and shared concerns of ‘overstepping certain norms’ (#11).

B. Respect and Hierarchy

Respect was a key factor brought up when exploring the socio-cultural aspects of mentoring in our Asian community. Mentors varied in their opinion as to the extent that this resulted in a hierarchical relationship, and if this had a negative or positive impact on the relationship.

All agreed that respect is a key value in mentoring relationships:

Culturally there’s a large part to play as we’re taught to respect our elders. (#1)

Respecting elders – definitely it’s more prominent in our Asian culture. (#2)

Many mentors highlighted that this resulted in a hierarchical relationship. This manifested in the way senior doctors were addressed strictly by title, polite communication, and consideration of what would be ‘proper’ to discuss or ask a mentor to do.

The hierarchical kind of mindset is still very strong, and is something that is not necessarily healthy. (#4)

You would always see your mentor as someone higher than you. It’s similar to the way in our Asian context we see our parents. a certain sense of distance (#11).

The way medicine is a 师傅徒弟 kind of thing (‘master and disciple’) (#13)

Many shared that this could be a barrier to open communication with juniors wanting to “respect and agree” with their mentors (#14), slowing the growth of some relationships.

No matter how much honesty and trust there is. If they want to say something that their mentor is not happy to hear, or strikes them as being a bit rude or disrespectful – they won’t say it. (#1)

Our culture does say to respect your senior, don’t argue and don’t disagree with your senior. Sometimes they’re not very vocal, ‘ok sir ok sir’. And then later you find out they have certain issues. (#9)

One mentor felt that hierarchy did not play a large part in his mentoring relationships. This was possibly personality related, describing himself as naturally “quite informal”.

Mentors also highlighted factors that mitigated the hierarchical nature of their relationship. This included time, and setting clear boundaries and goals of the relationship.

When we give… a clear boundary and aim with no go zones, then culture may not necessarily be that important anymore (#10)

A minority of mentors felt that hierarchy and respect was not a limiting factor in their relationships:

If the primary aim is having someone to offer you guidance and a different point of view, even if the mentee sees you as someone who is not equal, you can still have that effectiveness. (#11)

C. Harmony, Avoiding Open Conflict and Confrontation

Another socio-cultural concept highlighted was the avoidance of confrontation. While some of this was linked to avoiding disagreements given the hierarchical nature of the relationship, avoiding open conflict and striving for harmony was also a key factor.

Rather than openly bringing up something, to avoid being confrontational we have evolved other means of trying to work our way through that conflict. There is a conscious and deliberate effort to avoid open and confrontational conflict. (#3)

When I was in the UK, they really questioned their mentors quite a lot – almost like a quarrel. That kind of questioning style may not be that well received in our own culture. (#2)

When mentees had differing opinions from their mentors “they would rather not talk about the topic again, or just ask someone else” in order to preserve the relationship (#1).

Within our program, this resulted in difficulties in exiting the relationship to avoid “offending” the mentor:

When the mentor-mentee relationship is breaking down, culturally it can be more difficult for mentees to request to swap. That’s very detrimental to both the mentor and the mentee in the long run. (#1)

This also manifested in avoiding overly ‘emotional’ discussions, with discussion often being more “superficial”, “reserved” (#7) and “factual” (#5) in nature.

Conversely, one mentee shared that younger mentees being of a “younger generation” were more open to speaking their mind, and that this would continue to evolve.

D. Importance of Trust and Establishing a Familial Relationship

In exploring key values for successful mentoring relationships, many highlighted the importance of trust and building up an established relationship.

Chemistry and compatibility when starting out was key. Mentors often felt more comfortable if there was a pre-existing relationship they had their mentors and had “shared commonalities and chemistry”. Honesty and trust were key in enabling the relationship to progress. This included respecting each other’s confidentiality. Relationships without trust was difficult as mentors “had to keep guessing what they want”, and “whatever you plan may not be the real goals of what they actually want” (#2). Over time, establishing the relationship made it easier to confide in each other, overcoming boundaries brought on by hierarchy.

It’s about forming relationships before you can start reflecting with the person. Over time we get to know each other, and seeing that what is shared is truly kept private and confidential. Once we have trust among each other it (reservations) doesn’t become a barrier. (#7)

There must be a certain comfort and trust level before one readily does share vulnerabilities. (#2)

This can be enabled by being approachable, and creating safe environments where mentors can share their difficulties without consequence. However, this could be compromised if mentors have to take up a supervisory role or be involved in remediation processes.

Mentors who developed close and trusting relationships with their mentees described it as familial in nature. This could be as a big brother or sister who would give advice to their younger siblings in non-threatening and neutral ways. It was also described by one mentor as parental in nature.

One interviewer highlighted that whilst Asian cultural factors may limit mentoring, there were also potential benefits:

We must find the best of both worlds. The independence that the Western systems have is good, but Asians tend to be better at teamwork and team spirit. (#13)

E. Value of Structure in an Asian Mentorship Relationship

Many mentors highlighted the value of having a framework for their mentoring relationship. Formalisation of the relationship and having a structure provided a foundation for discussions and enabled them to set boundaries. This prevented it from becoming awkward or “random and situation-based” (#15), and also helped faculty who were “still learning the whole journey of mentoring” (#7).

When we don’t know what to talk about it becomes quite awkward and uncomfortable. But if in the Asian context the mentor brings to it some structure, and they respect that structure, that structure is helpful. (#10)

A minority of mentors felt having a framework was too rigid or unnecessary.

The structure must be there to guide the mentors, but the mentors chosen must also be of a certain maturity so they can find their own way. We must not be too prescriptive or rigid. (#13)

IV. DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the lived experiences of mentors within an Asian paediatric postgraduate training program. Existing studies have explored characteristics of effective and ineffective mentor relationships, but less is known about the impact of sociocultural factors. Key thematic concepts identified such as “respect and hierarchy” and “avoidance of open conflict” highlighted the importance of cultural factors in shaping mentoring relationships in an Asian context. These are deeply rooted in social norms and values of the region.

Hierarchy is a fundamental aspect of many Asian cultures, where individuals are expected to show respect and deference to their ‘elders’ or those in positions of authority. This was also observed in other Asian communities. A study in postgraduate medicine in Japan found that mentees had an inner desire to “respect the mentor’s ideas”, with both mentees and mentors embracing “paternalistic mentoring” (Obara et al., 2021). In our interviews, this was most apparent in the way mentees addressed their mentors: by title and respectfully. On a deeper level, this was a barrier to open communication. Open sharing was identified as crucial for a constructive mentoring relationship (Burgess et al., 2018), with the lack of it a cause of failed mentoring relationships (Straus et al., 2013). The willingness to share personal experiences by both mentors and mentees is key for effective mentoring and career growth. Additionally, this is not conducive to fostering creativity and innovation, which are increasingly important in the medical profession.

Communication was also affected by avoidance of open conflict and confrontation. Asian cultures have been described as collectivist, where the needs of the group take precedence over that of the individual, and intragroup harmony is paramount (Chin & Kameoka, 2019). In mentoring relationships, this translates to prioritising a successful and harmonious relationship over personal goals. Indirect communication styles are also more common in many Asian cultures. This has been described as high-context communication, whereby “most of the information is either in the physical context or internalised in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message” (Hall, 1976). Relying on indirect language nonverbal cues rather than explicitly stating one’s thoughts and feelings can hinder open communication.

Hierarchy and a lack of open communication may result in mentors taking on the role of advisors or coaches rather than true mentors. While there is no universal definition of mentorship, key features are that of a long-term dyadic relationship that encompasses educational, training and professional aspects that is personal and reciprocal (Sambunjak & Marusic, 2009). This is in contrast to tutors or coaches that primarily exhibit educational functions, or counsellors that exhibit personal functions. If the mentor-mentee relationship if influenced by hierarchical norms, mentors may be seen as figures of authority rather than partners in development. Cultural respect for authority figures and an emphasis on conformity may also discourage mentees from questioning or having open conversations with their mentors, limiting mutual learning.

Challenges with hierarchy and communication can be overcome with the aid of a structured program, and eventually establishment of trust and ‘familial’ relationships. A structured program can guide mentors and mentees in having open communication. In an Asian context, mentors may initially play a more authoritative role in guiding and directing their mentees with the aid of a structured guide, from which more two-way communication may open up as the relationship becomes more established. Whilst desirable mentors have characteristically been described as not “bossy” or authoritative (Sambunjak & Marusic, 2009), a study of Japanese physician-scientist mentor-mentees viewed more paternalistic mentoring as favourable (Obara et al., 2021). However, this will need to be individualised, as a highly directive mentoring style may not be well-suited to those who prefer a more collaborative and participatory mentoring relationship. Communication and learning styles may also continue to evolve with as incoming trainee physicians belong increasingly to Generation Z (1997-2012) instead of Generation Y/Millennials (1981-1996). A study of the mentorship experiences of Gen Z women medical students by Li et al (2024) described how current society had afforded them more opportunities for empowerment and expression, and emphasised the importance of tailored mentorship that considered the mentee’s identify and intersectionality.

Having mutual respect and trust were also key. The mentee and mentor having a pre-existing relationship and familiarity helped, and was more common in our context given that mentees could indicate their mentor of interest. Mutual respect and having a personal connection were also identified as key components in effective mentoring relationships by Eller (2014) and Straus (2013).

Whilst we had initially hypothesised that Asian sociocultural concepts would limit mentorship relationships to be largely professional, mentors shared that mutual respect, trust, and time enabled the relationship to also extend to sharing of personal matters and psychosocial wellbeing. Successful relationships were even described as ‘familial’, with a sense of fulfilment from both parties. A family-like relationship and a sense of loyalty to the mentor and organisation was also described in Japanese mentoring relationships (Obara et al., 2021). Such relationships may be more common in more collectivist cultures. These can be furthered by fostering a sense of community amongst mentees and mentors, such as through group activities, peer support, and shared learning experiences.

A. Limitations

This study was conducted in one of the two paediatric training centres in Singapore. Future studies should expand to other postgraduate programs to improve applicability of the results.

The investigators were participants in the program as mentees or mentors, with potential for bias in analysis. To minimise this, transcripts were analysed independently by two investigators followed by review by the third investigator. While our study focused on the lived experience of mentors, examining the perspective of mentees would be able to provide a more balanced and comprehensive understanding of mentoring relationships and highlight gaps where they can be better supported, and should be considered in future studies.

Our study did not delve into gender dynamics. Female medical trainees may face unique challenges, and male mentors may be stereotypically less nurturing and more process-oriented. Existing studies are varied: a survey of American cardiologists found sex concordance to be beneficial (Abudayyeh et al., 2020), whereas Jackson (2003) did not find same-gender matching to be important in an US academic program. In our initial interviews, gender did not come up as a significant factor and was hence not a focus subsequently. The role of gender in our program may have been minimised by a balanced gender ratio, with 59% of faculty female.

B. Future Research and Practical Implications

Given the significant influence of sociocultural factors on mentoring relationships, mentoring programs should be tailored to reflect the unique cultural norms and values of the region. In Asian cultures, this would include methods to reduce hierarchy, ensuring accessibility to mentors, and having a structured program. Training on mentorship for mentors and mentees would be beneficial to promote characteristics of effective mentoring relationships, and should include a focus on culturally sensitive mentoring with a recognition of how culturally-shaped beliefs can affect mentorship. This is particularly important in multicultural societies where cross-cultural mentorship is more common.

V. CONCLUSION

Cultural factors play an important role in shaping mentoring relationships in an Asian context. Whilst such these may be limiting to a degree, these can be also be leveraged on to further effective mentoring programs. Mentoring programs should be tailored to reflect the unique cultural norms and values of the region to promote career growth and personal development of trainees and mentors.

Notes on Contributors

AC, MD and SG contributed to study conception and design. Participant interviews were conducted by AC. Analysis and thematic interpretation were done by AC, MD with review by SG. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and reviewing it critically, and all read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the SingHealth Institution Review Board (IRB number 2021/2542).

Data Availability

The data of this qualitative study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the participants.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Abudayyeh, I., Tandon, A., Wittekind, S. G., Rzeszut, A. K., Sivaram, C. A., Freeman, A. M., & Madhur, M. S. (2020). Landscape of mentorship and its effects on success in cardiology. JACC: Basic to Translational Science, 5(12), 1181-1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.09.014

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., & Mellis, C. (2018). Mentorship in the health professions: A review. The Clinical Teacher, 15(3), 197-202. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12756

Chin, D., & Kameoka, V. A. (2019). Mentoring Asian American scholars: Stereotypes and cultural values. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(3), 337-342. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000 411

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE Publications.

Eller, L. S., Lev, E. L., & Feurer, A. (2014). Key components of an effective mentoring relationship: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), 815-820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt. 2013.07.020

Flint, J. H., Jahangir, A. A., Browner, B. D., & Mehta, S. (2009). The value of mentorship in orthopaedic surgery resident education: The residents’ perspective. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 91(4), 1017-1022. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00934

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor Press/Double Day.

Jackson, V. A., Palepu, A., Szalacha, L., Caswell, C., Carr, P. L., & Inui, T. (2003). “Having the right chemistry”: A qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Academic Medicine, 78(3), 328-334. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020

Khair, A. M., Abdulrahman, H. M., & Hammadi, A. A. (2015). Mentorship in pediatric Arab board postgraduate residency training program: Qatar experience. Innovations in Global Health Professions Education. https://doi.org/10.20421/ighpe2015.6

Li, C., Veinot, P., Mylopoulos, M., Leung, F. H., & Law, M. (2024). The new mentee: Exploring Gen Z women medical students’ mentorship needs and experiences. The Clinical Teacher, 21(3), e13697. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13697

Obara, H., Saiki, T., Imafuku, R., Fujisaki, K., & Suzuki, Y. (2021). Influence of national culture on mentoring relationship: A qualitative study of Japanese physician-scientists. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02744-2

Ramanan, R. A., Taylor, W. C., Davis, R. B., & Phillips, R. S. (2006). Mentoring matters: Mentoring and career preparation in internal medicine residency training. Journal of General Intermal Medicine, 21(4), 340-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.20 06.00346.x

Sambunjak, D. (2015). Understanding wider environmental influences on mentoring: Towards an ecological model of mentoring in academic medicine. Acta Medica Academica, 44(1), 47-57. https://doi.org/10.5644/ama2006-124.126

Sambunjak, D., & Marusic, A. (2009). Mentoring: What’s in a name? JAMA, 302(23), 2591-2592. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama. 2009.1858

Sambunjak, D., Straus, S. E., & Marusic, A. (2006). Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA, 296(9), 1103-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103

Spickard, A., Gabbe, S. G., & Christensen, J. F. (2002). Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. JAMA, 288(12), 1447-1450. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.12.1447

Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372-1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

Straus, S. E., Johnson, M. O., Marquez, C., & Feldman, M. D. (2013). Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: A qualitative study across two academic health centers. Academic Medicine, 88(1), 82-89. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0

*Dr Aletheia Chia

Department of Paediat,

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

100 Bukit Timah Road

Singapore 229899

Email: aletheia.chia@mohh.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.