From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon

Submitted: 19 May 2021

Accepted: 7 October 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 21-32

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/RA2537

Kirsty J Freeman1, Sandra E Carr2, Brid Phillips2, Farah Noya3 & Debra Nestel4,5

1Office of Education, Duke NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore; 2Division of Health Professions Education, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia; 3Faculty of Medicine, Pattimura University, Ambon, Indonesia; 4School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Australia; 5Austin Precinct, Department of Surgery, University of Melbourne, Heidelberg, Australia

Abstract

Introduction: As healthcare educators undergo a career transition from providing care to providing education, their professional identity can also transition accompanied by significant threat. Given their qualifications are usually clinical in nature, healthcare educators’ knowledge and skills in education and other relevant theories are often minimal, making them vulnerable to feeling fraudulent in the healthcare educator role. This threat and vulnerability is described as the impostor phenomenon. The aim of this study was to examine and map the concepts of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators.

Methods: The authors conducted a scoping review of health professions literature. Six databases were searched, identifying 121 relevant articles, eight meeting our inclusion criteria. Two researchers independently extracted data, collating and summarising the results.

Results: Clinicians who become healthcare educators experience identity ambiguity. Gaps exist in the incidence and influence of impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators. Creating communities of practice, where opportunities exist for formal and informal interactions with both peers and experts, has a positive impact on professional identity construction. Faculty development activities that incorporate the beliefs, values and attributes of the professional role of a healthcare educator can be effective in establishing a new professional identity.

Conclusion: This review describes the professional identity ambiguity experienced by clinicians as they take on the role of healthcare educator and solutions to ensure a sustainable healthcare education workforce.

Keywords: Professional Identity, Impostor Phenomenon, Healthcare Educators, Health Professions Education, Scoping Review

Practice Highlights

- Professional identity ambiguity experienced when a clinician transitions to the role of healthcare educator is understudied relative to other professions.

- Professional identity ambiguity experienced when a clinician transitions to the role of healthcare educator is understudied relative to other professions.

- Creating communities of practice, whereby healthcare educators can interact with peers and experts, in both formal and informal settings, has a positive impact on professional identity construction.

- Faculty development activities that incorporate the beliefs, values and attributes of the professional role of a healthcare educator are effective in establishing a new professional identity or aligning multiple professional identities.

I. INTRODUCTION

Educating the current and future healthcare workforce relies on clinicians sharing their knowledge, skills and experience by teaching others. Some clinicians have a passion to educate and seek out this role. For others it is often their high level of clinical expertise that results in requests to take on an education role. This may result in an expansion of their current role as a clinician, or a transition from one role to another. There are many terms used to describe those teaching in healthcare including educator, teacher, and faculty. The term healthcare educators is used throughout this paper to describe clinicians educating in any environment. Changes in work roles can pose a threat to an individual’s identity (Barbulescu & Ibarra, 2008; Becker & Carper, 1956), as this requires the individual to develop a new sense of self (Conroy & O’Leary-Kelly, 2014). With this change in role comes a transition in professional identity.

Professional identity is defined as “the relatively stable and enduring constellation of attributes, beliefs, values, motives, and experiences in terms of which people define themselves in a professional role” (Ibarra, 1999, pp. 764). The formation of professional identity is centred on how an individual perceives themselves as a professional, their relationship with the profession, and how their knowledge, skills and attitudes align with the norms and culture of that profession (Sethi et al., 2018). Within healthcare there has been a call for professional identity formation to be explicitly addressed in the curriculum of future healthcare professionals, addressing both what it is to think, act and feel like a healthcare professional, and the processes by which that identity is formed (Cruess et al., 2019).

Individuals manage numerous identities during their lifespan, across personal, vocational, social and professional spheres. Van Gennep’s theory of rites of passage, where-by an individual transitions through three phases 1) ‘separation’ – letting go of the old self, 2) ‘liminality’ – middle phase, and 3) ‘aggregation’ – establishing a new identity, has been cited in the literature to describe career transition and formation of a new identity (Kulkarni, 2019; Mayrhofer & Iellatchitch, 2005; Petersen, 2017). It is in this middle phase of liminality where a clinician taking on the role of a healthcare educator may experience identity ambiguity. Given that literature from other industries show that professional identity can influence job satisfaction, feelings of accomplishment, and employment retention (Canrinus et al., 2012; Hutchins et al., 2018), it is essential that the formation of professional identity and potential identity ambiguity in healthcare educators is examined.

The term impostor phenomenon, also known as impostor syndrome, is used to describe negative feelings an individual experiences, despite achieving a level of competence, and the fear of being ‘found out’ by those around them (Clark et al., 2014). The concept of being exposed as a ‘fraud’ was coined impostor phenomenon by clinical psychologists Clance and Imes (1978). Literature suggests that despite external evidence of their competence, those exhibiting the phenomenon remain convinced that they are frauds and do not deserve the success they have achieved (Leonhardt et al., 2017; Neureiter & Traut-Mattausch, 2016; Vergauwe et al., 2015).

In their seminal work from the late 1970’s, Clance and Imes (1978) reported that impostor phenomenon is more prevalent in specific female populations. Recent studies however have shown that impostor phenomenon impacts individual regardless of gender, and occurs in a variety of contexts (Bernard et al., 2018; Chae et al., 1995). Prominent among high performing individuals, impostor phenomenon is experienced on a continuum from the occasional concern that the individual is not up to the task, to an extreme fear of being ‘found out’ as a fraud (Hibberd, 2019). Studies suggest that impostor phenomenon can have significant negative effects including an increase in work-family conflict (Crawford et al., 2016), and decreased job satisfaction (Cowman & Ferrari, 2002), with studies also reporting a link between impostor phenomenon and burnout (Villwock et al., 2016).

With impostor phenomenon well described in professions outside of healthcare, most literature published on impostor phenomenon within the healthcare professions has focused on students transitioning from study to the workplace (Aubeeluck et al., 2016; Dudău, 2014; Robinson-Walker, 2011), with very few studies examining current working professionals (Gottlieb et al., 2019; Hutchins et al., 2018). The aim of this study was to examine and map the concepts of professional identity and implications of impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators. By furthering our understanding of impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators and how it impacts professional identity, both individuals and organisations will be able to implement strategies that will assist in the development of a sustainable healthcare education workforce, addressing workforce capability, capacity, resilience and culture.

II. METHODS

The aim of a scoping review is to examine evidence, identify gaps in the literature, and clarify key concepts (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). The objective of this scoping review is to examine and map the concepts of professional identity and impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators.

A. Review Questions

The primary review question was ‘how is professional identity and impostor phenomenon described in the literature about healthcare educators?’, with the secondary review question being ‘how is professional identity of healthcare educators influenced by imposter phenomenon?’. Tricco et al. (2016) identified 25 knowledge synthesis methods used across the health fields. We selected a scoping review methodology as it is the most appropriate to address our aim to map and summarise the literature, clarify working definitions and identify gaps. The framework that will guide the process is the five-step approach proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). The steps are 1) identify the research question; 2) identify the relevant articles; 3) select the articles; 4) chart the data; and 5) collate and summarise the results.

B. Identifying Relevant Articles

Adopting the population, concept, and context (PCC) framework (Peters et al., 2020) informed the development of the search strategy as demonstrated in Table 1.

|

|

Main concepts |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Population |

Concept 1 |

Concept 2 |

Context |

|||

|

|

Healthcare educators |

Professional identity |

Impostor phenomenon |

Healthcare education |

|||

|

Search Terms |

“healthcare educator.ti,ab,kw.” “nursing educator.ti,ab,kw.” “medical educator.ti,ab,kw.” “allied health educator.ti,ab,kw” “faculty.ti,ab,kw.” “facilitator.ti,ab,kw.” “educator.ti,ab,kw.” “*faculty, medical/ or *faculty, nursing/ or *health educators/” “clinical educator.ti,ab,kw.” “clinical teacher.ti,ab,kw.” |

“Professional identity.ti,ab,kw.” “Professional role*.ti,ab,kw.” “Professional competence.ti,ab,kw.” “Professional sociali*ation.ti,ab,kw.” “Professional identity formation.ti,ab,kw.” “*Professional Competence/” “*Professional Role/” “*Professionalism/” |

“impostor.ti,ab,kw.” “imposter.ti,ab,kw.” “fraud.ti,ab,kw.” “fake.ti,ab,kw.” “impost*rism.ti,ab,kw.” “intellectual fraud*.ti,ab,kw.” “(impost*r adj3 syndrome).ti,ab,kw.” “(impost*r adj3 phenomenon).ti,ab,kw.” “*Adaptation, Psychological/” “*Self Concept/” “*social identification/” “Self concept.ti,ab,kw.” |

“education, medical/ or *education, medical, continuing/ or *education, medical, graduate/ or *education, medical, undergraduate/” “*Education, Nursing/” “*Education, Allied Health/” “*Education, Clinical/” “education, medical/ or education, nursing/ or education, pharmacy/ or education, public health professional/” |

|||

Table 1: Key search terms

Note: ti = title; ab = abstract; kw = keyword

To identify potentially relevant articles, a literature search of six online databases was conducted on the November 6, 2020. These included MEDLINE, EMBASE, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and ERIC. The search strategies were drafted in collaboration with an experienced librarian and further refined by the researchers. The search strategy conducted in MEDLINE is detailed in Table 2. The final search results were exported into Covidence systematic review software, a screening and data extraction tool (Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2019).

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

1 |

healthcare educator.ti,ab,kw. |

5 |

|

2 |

nursing educator.ti,ab,kw. |

51 |

|

3 |

medical educator.ti,ab,kw. |

164 |

|

4 |

allied health educator.ti,ab,kw. |

7 |

|

5 |

faculty.ti,ab,kw. |

46912 |

|

6 |

facilitator.ti,ab,kw. |

6518 |

|

7 |

educator.ti,ab,kw. |

5586 |

|

8 |

*faculty, medical/ or *faculty, nursing/ or *health educators/ |

14624 |

|

9 |

clinical educator.ti,ab,kw. |

119 |

|

10 |

clinical teacher.ti,ab,kw. |

279 |

|

11 |

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

66130 |

|

12 |

Professional identity.ti,ab,kw. |

1917 |

|

13 |

Professional role*.ti,ab,kw. |

2643 |

|

14 |

Professional competence.ti,ab,kw. |

1267 |

|

15 |

Professional sociali*ation.ti,ab,kw. |

376 |

|

16 |

Professional identity formation.ti,ab,kw. |

241 |

|

17 |

*Professional Competence/ |

11751 |

|

18 |

*Professional Role/ |

6495 |

|

19 |

*Professionalism/ |

836 |

|

20 |

12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 |

24196 |

|

21 |

impostor.ti,ab,kw. |

169 |

|

22 |

imposter.ti,ab,kw. |

148 |

|

23 |

fraud.ti,ab,kw. |

4102 |

|

24 |

fake.ti,ab,kw. |

1772 |

|

25 |

impost*rism.ti,ab,kw. |

16 |

|

26 |

intellectual fraud*.ti,ab,kw. |

7 |

|

27 |

(impost*r adj3 syndrome).ti,ab,kw. |

57 |

|

28 |

(impost*r adj3 phenomenon).ti,ab,kw. |

63 |

|

29 |

*Adaptation, Psychological/ |

43405 |

|

30 |

*Self Concept/ |

25641 |

|

31 |

*social identification/ |

5255 |

|

32 |

Self concept.ti,ab,kw. |

5240 |

|

33 |

21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 |

80945 |

|

34 |

20 and 33 |

597 |

|

35 |

education, medical/ or *education, medical, continuing/ or *education, medical, graduate/ or *education, medical, undergraduate/ |

108815 |

|

36 |

*Education, Nursing/ |

24454 |

|

37 |

*Education, Allied Health/ |

0 |

|

38 |

*Education, Clinical/ |

0 |

|

39 |

education, medical/ or education, nursing/ or education, pharmacy/ or education, public health professional/ |

96076 |

|

40 |

35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 |

147396 |

|

41 |

11 and 34 and 40 |

17 |

Table 2: Search strategy conducted in Ovid MEDLINE on November 6, 2020

C. Eligibility Criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the study, articles were required to satisfy the following criteria:

1. Population: This scoping review will consider literature that included educators within the healthcare context. Educators can include those of any age, gender, culture or geography.

2. Concept: There are two concepts that will be examined in this review, transition in professional identity and impostor phenomenon. This review will include the definition of the concepts, the theoretical, conceptual and the measurement of both concepts.

3. Context: This review will consider literature written in English, from any healthcare context with no restrictions on geographical location, or cultural factors.

D. Selection of Articles

One hundred and twenty-one articles were collated and citations, title and abstract were retrieved. An initial check identified one duplicate, which was removed. Titles and abstracts of the 120 articles were screened by three independent reviewers (KF, FN, BP) for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. Thirty-three articles were found to meet the inclusion criteria and progressed to full text review. Two researchers (KF, BP) conducted a full text review, recording reasons for exclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and consensus. Based on the Joanna Briggs Institute recommendations on scoping review methods, no critical appraisal of methodological quality was undertaken (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017).

E. Charting the Data

A data-charting form to determine which data to extract was jointly developed by two researchers (KF, SC). Two researchers (KF, BP) independently charted the data, then discussed the results and edited the data-charting form as required. A third researcher (FN) verified the data.

F. Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Data

Data was abstracted on article characteristics including country of publication, population of interest, study aim, sample size, study design, data collection methods, and findings related to the concepts of professional identity and impostor phenomenon.

III. RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-one abstracts were identified from six databases, 33 full text articles were reviewed, and 8 full text articles were analysed (See Figure 1). Of the included articles five were conducted in the USA (Cranmer et al., 2018; Heinrich, 1997; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002; Talisman et al., 2015), and one in each of Australia (Higgs & McAllister, 2007), Canada (Lieff et al., 2012), and the United Kingdom (Andrew et al., 2009) (Table 3). In relation to the population of healthcare educators, four articles involved those working in medicine (Cranmer et al., 2018; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002; Talisman et al., 2015), two in nursing (Andrew et al., 2009; Heinrich, 1997), one in speech pathology (Higgs & McAllister, 2007), and one involving healthcare educators from multiple professions (Lieff et al., 2012). Five studies adopted a qualitative approach, such as interviews or narrative responses, (Andrew et al., 2009; Higgs & McAllister, 2007; Lieff et al., 2012; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002), one employing a quantitative approach (Cranmer et al., 2018), one mixed methods (Talisman et al., 2015), and one article was a program description (Heinrich, 1997).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

|

Article |

Country |

Population |

Study aim |

Sample size (n) |

Study design |

Data collection method |

Findings |

|

Andrew et al. (2009) |

UK |

Nursing |

To explore online communities for novice educators to develop professional identity |

14 |

Qualitative content analysis |

Web blog |

Communities of practice can help in the development of professional identity |

|

Talisman et al. (2015) |

USA |

Medicine |

To explore the impact of teaching the mind-body medicine course on course facilitator’s professional identity |

50 |

Mixed Methods cross sectional design |

Survey including the FMI & PSS tools, & open-ended questions |

Participation as a facilitator in a mind-body medicine program has tangible positive outcomes for the professional identity of facilitators through improved communication, connection, empathy, and self-confidence. |

|

Stone et al. (2002) |

USA |

Medicine |

To examine factors that preceptors perceive as important to their identity as teachers |

10 |

Qualitative |

Semi-structured interviews |

Preceptors associate strong feelings with their identity as teacher. Four aspects of teacher identity are as follows: humanitarianism; adult learning principles; benefits and drawbacks, and image of self as teacher. Teacher identity was not associated with student learning. Faculty development can foster preceptor identity as teacher. |

|

O’Sullivan and Irby (2014) |

USA |

Medicine |

To examine identity formation of part time faculty developers |

29 |

Qualitative |

Semi-structured interviews |

Professional identity is fluid, and evolves over time. Faculty development, particularly developing others has a direct impact on this. |

|

Lieff et al. (2012) |

Canada |

Multiple professions |

To understand the factors that relate to the formation and growth of academic identity |

43 |

Qualitative case study approach |

Reflective paper and focus groups |

Academic identity formation is influenced by personal, relational and contextual factors, and that this identity the motivation, satisfaction, and productivity of health professional educators. |

|

Higgs and McAllister (2007) |

Australia |

Speech Pathology |

To examine the preparation and professional development of clinical educators based on research into the experiences of being a clinical educator |

5 |

Qualitative approach using hermeneutic phenomenology and narrative inquiry |

Interviews |

The model of The Experience of Being a Clinical Educator, emphasising six dimensions: a sense of self, of self-identity; a sense of relationship with others; a sense of being a clinical educator; a sense of agency or purposeful action; dynamic self-congruence; and the experience of growth and change, can be used as the basis for helping clinical educators to reflect on what it means to be a clinical educator Faculty development activities that include reflective strategies can assist the educator transition from novice to expert. |

|

Heinrich (1997) |

USA |

Nursing |

To describe an educational interventional designed to assist nurses who experience impostor phenomenon as they negotiate professional transitions |

Not stated |

Program description |

Faculty/author observation |

Impostor phenomenon is prevalent among nurses as they negotiate professional identity transformation, and that the use of metaphors in faculty development programs can be effective in aiding this transition. |

|

Cranmer et al. (2018) |

USA |

Medicine |

To describe the impact of a faculty mentoring program on the retention, promotion and professional fulfilment of junior faculty members |

23 |

Quantitative |

Survey |

Participation in a mentoring program has a positive effect on confidence, self-efficacy and skills, and that participation can assist new academic s develop their academic role and achieve professional fulfilment by fostering strong collegial and social relationships, ultimately leading to career satisfaction. |

Table 3. Summary of extracted data from the included articles

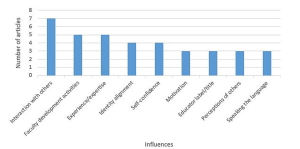

Articles identified several key influences when describing the professional identity of healthcare educators (Figure 2). Seven articles describe the healthcare educator’s interaction with others as having a positive influence on professional identity (Andrew et al., 2009; Heinrich, 1997; Higgs & McAllister, 2007; Lieff et al., 2012; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002; Talisman et al., 2015). Interactions with peers was identified as being key to clinicians successfully adopting an educator professional identity. One study found that by providing opportunities for informal discussions and social interactions amongst peers, healthcare educators reported a sense of belonging which was found to be essential in identity formation (Lieff et al., 2012). These findings were supported by Andrew et al. (2009) who found that online communities of practice were effective in supporting new educators in developing their professional identity.

Figure 2. Key influences of professional identity

Interactions between the novice and expert educators were reported to have both a positive and negative influence on healthcare educators as they construct their educator identity. Two studies described the positive impact of formal mentoring programs, one as a means of maintaining a link to their clinical identity (Andrew et al., 2009), and the other as a tool to successfully negotiate the role transition (Cranmer et al., 2018). Lieff et al. (2012) reported that whilst certain individuals are motivated by experts, seeing them as role models, others were intimidated, discouraged, and overwhelmed by the interaction with the expert. Comparing oneself to others has the potential to reinforce or inhibit the development of the healthcare educator identity (Lieff et al., 2012).

The role of faculty development activities on educator professional identity was reported by five studies (Cranmer et al., 2018; Heinrich, 1997; Higgs & McAllister, 2007; Lieff et al., 2012; Stone et al., 2002). Three studies recommended that faculty development programs include content on fostering the development of identity as a healthcare educator (Higgs & McAllister, 2007; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002). One study recommended using faculty development activities to remind clinicians of their existing role as educators to patients as a means of increasing their confidence and enhance educator identity (Stone et al., 2002). Another study identified the importance of faculty development programs in facilitating interactions with other healthcare educators with varying levels of expertise, that foster a sense of belonging (Lieff et al., 2012).

The perceptions of others was found to have an influence on professional identity (Andrew et al., 2009; Lieff et al., 2012; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014). One study reported that an evolving identity can be strengthened when the educator was seen by others as an educator, validating the new identity. The opposite was also found to be true where the perceptions of others that one is an educator could place a high level of anxiety on the emerging identity not yet fully embraced (Lieff et al., 2012). The influence which holding the title of healthcare educator had on an emerging identity is also linked to the perceptions of others. When labelled and referred to by others as an educator two studies found that professional identity as an educator was reinforced (Lieff et al., 2012; Stone et al., 2002).

Three studies found that the ability to learn and speak the language of the healthcare educator influenced how individuals developed their professional identity (Lieff et al., 2012; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002). O’Sullivan and Irby (2014) found that sharing a common healthcare educator language increased deeper relationship between educators, with Lieff et al. (2012) reporting that acquiring the right language provided credibility and legitimacy. A strong sense of professional identity was linked to motivation to educate, with one study suggesting that a desire to teach correlated with satisfaction in the role (Stone et al., 2002).

Aspects of identity alignment was found to be key in a healthcare educator’s professional identity formation (Andrew et al., 2009; Lieff et al., 2012; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002). One study of novice nurse educators described the tension experienced when managing the dual identities of clinician and educator, and the stress that maintaining dual roles places on these nurses (Andrew et al., 2009). Another study looking at multiple healthcare professions highlighted this struggle, with participants facing the dilemma of how they can excel in both identities simultaneously (Lieff et al., 2012). Exploring physician educators, the study by Stone et al. (2002) found that the identities of clinician and educator were interwoven.

Four studies reported that as self-confidence developed so too did professional identity (Cranmer et al., 2018; Heinrich, 1997; Lieff et al., 2012; Talisman et al., 2015). Data from the study by Lieff et al. (2012) revealed that just as self-confidence ebbed and flowed during a healthcare educator’s role transition, so too did their identity, resulting in feeling like an impostor. Talisman et al. (2015) found that as self-confidence grew fear of rejection by colleagues became less, and that self-confidence in ones’ professional identity opened up opportunities to develop as a healthcare educator.

Only one study (Heinrich, 1997) made specific reference to the concept of impostor phenomenon, describing an educational program using metaphors as a corrective tool for those who experience feeling like a fraud. The authors do not provide any data on the prevalence of impostor phenomenon in the population of healthcare educators, nor do they provide any results on the impact of the educational program described.

IV. DISCUSSION

Healthcare educators manage multiple identities, from social and cultural, to gender and religious, however professional identity tends to contribute a large part of an individual’s overall identity. A change in professional identity brings with it inconsistencies between the old and the new, producing anxiety and discomfort, as the individual navigates this transition phase through which identity is reconstructed (Beech, 2010). In answering the review question, ‘How is professional identity and impostor phenomenon described in the literature about healthcare educators?’ the findings indicate that in relation to professional identity, clinicians who become educators experience identity ambiguity, in line with the theory of rites of passage described by Van Gennep (Kulkarni, 2019; Petersen, 2017). Characteristics of impostor phenomenon include anxiety, lack of self-confidence, depression, and frustration (Heinrich, 1997; Hibberd, 2019). While the literature describes the experiences of healthcare educators as they strive to solidify their professional identities, this review suggests that despite impostor phenomenon being described since the 1970’s, the reporting of the phenomenon in the healthcare literature has only occurred in recent years, impostor phenomenon is not being measured amongst healthcare educators.

For the secondary question in this review ‘How is professional identity of healthcare educators influenced by imposter phenomenon?’ we found that there are key influences (Figure 2) that can be harnessed, through faculty development activities, to assist individual’s transition to Van Gennep’s third phase, aggregation, which is the final step in transitioning to a new career and establishing a new professional identity.

Creating opportunities for interactions with others, both peers and experts, through formal and informal interactions, has a positive impact on professional identity construction (Lieff et al., 2012; O’Sullivan & Irby, 2014; Stone et al., 2002). A community of practice has been described as a collection of individuals who have a shared interest and who wish to deepen their knowledge, where participation provides members an opportunity to learn from one another (Wenger, 2010). The opportunity to engage in a community of practice enables the novice healthcare educator to construct their identity by comparing themselves with others, “boosting their confidence and solidifying their identities as educators” (Lieff et al., 2012; Wenger, 2010).

Communities of practice have been used in the healthcare sector in a variety of forms and with varying purposes (Dickinson et al., 2020; Ranmuthugala et al., 2011). Elements of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and social comparison theory (Bonifield & Cole, 2008) underpin the outcomes that result from participating in a community of practice, whereby members learn through observing the behaviour of others. If the purpose of a community of practice is to assist in professional identity formation, membership needs to be carefully cultivated as the findings of this study acknowledge the potential negative influence ‘experts’ can have, as other members compare themselves, possibly viewing themselves as inadequate (Lieff et al., 2012).

The formation of single-disciplinary communities of practice should be considered given that this study has revealed healthcare educators from nursing and medicine experience their identity alignment differently. Nurses were reported as struggling with managing the dual identities of clinician and educator (Andrew et al., 2009), whereas the physicians viewed them as interwoven (Stone et al., 2002).

Faculty development activities traditionally focus on providing healthcare educators with the knowledge and skill required to perform a new role. Adopting a new professional identity as a healthcare educator involves more than acquiring new skills, but also new behaviours and attitudes (Ibarra, 1999). The findings of this review support the addition of a specific focus on fostering professional identity as part of any faculty development program for new healthcare educators (O’Sullivan et al., 2021). Such inclusions to faculty development activities could be used to emphasize the skills that clinicians have as educators, skills that are transferable to their role in teaching emerging or current clinicians (Stone et al., 2002).

This review has revealed the tension that healthcare educators may experience as they transition from one professional identity to another, as well as the struggles in balancing dual identities. The impact of this identity misalignment on the individual could result in levels of stress that see the individual reverting to their clinical professional identity and withdrawing from the healthcare educator workforce. Healthcare training organisations need to ensure that strategies such as developing communities of practice and faculty development activities are engaged to support healthcare educators on their rite of passage to developing their healthcare educator identity.

Whilst several tools to measure impostor phenomenon exist, including the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS), Harvey Impostor Scale, Perceived Fraudulence Scale and Leary Impostor Scale, Mak et al. (2019) report that no scales have been validated for use with healthcare educators, a finding supported by this review.

Our findings indicate a paucity of articles on the influence of impostor phenomenon on healthcare educators as they align their clinical and educator identities. This review has described the influences on professional identity that can be harnessed to address identity ambiguity, resulting in improved job satisfaction, employment retention, ensuring a sustainable healthcare education workforce.

A. Limitations of the Review

Six databases across health and education were included; it is possible that additional articles may have been identified if different databases were searched. We did not comprehensively search the gray literature beyond conference abstracts, protocols, and dissertations. By limiting our coverage of articles only published in English we may have missed important studies published in other languages, potentially resulting in a regional bias. As no critical appraisal of methodological quality was undertaken the reliability of some findings may be limited. With the ever-changing use of language the search terms selected related to the concepts of professional identity and impostor phenomenon may not be exhaustive.

V. CONCLUSION

The influence of impostor phenomenon on the professional identity alignment in healthcare educators has the potential to negatively impact the education of the current and future healthcare workforce. This review is a starting point for individuals and organisations involved in health professions education, and faculty development. It offers insight to the under examined understudied but potentially important prevalence and impact of impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators and the professional identity ambiguity experienced by clinicians as they take on the role of healthcare educator. This review highlights the need for further research into the prevalence of impostor phenomenon in healthcare educators across different settings, as well as exploring the experience and influence of impostor phenomenon on professional identity.

Notes on Contributors

KF led the design and conceptualisation of this work, drafted the protocol, developed the search strategy, and conducted the search, data extraction, analysis, discussion and conclusion. SC and DN were involved in the conceptualisation of the review design, specifically in establishing the review question as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria, provided feedback on the manuscript. BP, FN and SC guided the conceptualisation and design of the study and participated in data analyses and have revised all drafts of the manuscript. All authors approve the publishing of this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee: RA/4/20/5061.

Data Availability

All relevant quantitative data are within the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Terena Solomons, Faculty Librarian, for her support and guidance in the development of the search strategy.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Andrew, N., Ferguson, D., Wilkie, G., Corcoran, T., & Simpson, L. (2009). Developing professional identity in nursing academics: The role of communities of practice. Nurse Education Today, 29(6), 607-611. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.01.012

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methods, 8, 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/136455703200011961

Aubeeluck, A., Stacey, G., & Stupple, E. J. N. (2016). Do graduate entry nursing student’s experience ‘Imposter Phenomenon’?: An issue for debate. Nurse Education in Practice, 19, 104-106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.06.003

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Barbulescu, R., & Ibarra, H. (2008). Identity as narrative: Overcoming identity gaps during work role transitions. INSEAD Working Papers Collection, 27, 1-39.

Becker, H. S., & Carper, J. W. (1956). The development of identification with an occupation. The American Journal of Sociology, 61(4), 289-298. https://doi.org/10.1086/221759

Beech, N. (2010). Liminality and the practices of identity reconstruction. Human relations (New York), 64(2), 285-302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710371235

Bernard, D. L., Hoggard, L. S., & Neblett, E. W. (2018). Racial discrimination, racial identity, and impostor phenomenon: A profile approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(1), 51-61. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000161

Bonifield, C., & Cole, C. A. (2008). Better him than me: Social comparison theory and service recovery. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 36(4), 565-577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0109-x

Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2012). Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation and commitment: Exploring the relationships between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 115-132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0069-2

Chae, J. H., Piedmont, R. L., Estadt, B. K., & Wicks, R. J. (1995). Personological evaluation of Clance’s imposter phenomenon scale in a Korean sample. Journal of personality assessment, 65(3), 468-485. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy, 15(3), 241-247. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

Clark, M., Vardeman, K., & Barba, S. (2014). Perceived inadequacy: A study of impostor phenomenon among college and research librarians. College & Research Libraries, 75(3), 255-271. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-423

Conroy, S. A., & O’Leary-Kelly, A. M. (2014). Letting go and moving on: Work-related identity loss and recovery. The Academy of Management review, 39(1), 67-87. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0396

Covidence Systematic Review Software. (2019). Veritas Health Innovation. https://covidence.org

Cowman, S. E., & Ferrari, J. R. (2002). “Am I for real?” Predicting impostor tendencies from self-handicapping and affective components. Social Behavior and Personality, 30(2), 119-125. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2002.30.2.119

Cranmer, J. M., Scurlock, A. M., Hale, R. B., Ward, W. L., Prodhan, P., Weber, J. L., Casey, P. H., & Jacobs, R. F. (2018). An adaptable pediatrics faculty mentoring model. Pediatrics, 141(5), Article e20173202. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3202

Crawford, W. S., Shanine, K. K., Whitman, M. V., & Kacmar, K. M. (2016). Examining the impostor phenomenon and work–family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(2), 375-390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-12-2013-0409

Cruess, S. R., Cruess, R. L., & Steinert, Y. (2019). Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Medical Teacher, 41(6), 641-649. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.153626

Dickinson, B., Chen, Z. X., & Haramati, A. (2020). Supporting medical science educators: A matter of self-esteem, identity, and promotion opportunities. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(3), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-3/PV2164

Dudău, D. P. (2014). The relation between perfectionism and impostor phenomenon. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 127, 129-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.226

Gottlieb, M., Chung, A., Battaglioli, N., Sebok‐Syer, S. S., & Kalantari, A. (2019). Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: A scoping review. Medical Education, 54(2), 116-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13956

Heinrich, K. T. (1997). Transforming impostors into heroes. Metaphors for innovative nursing education. Nurse educator, 22(3), 45-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-199705000-00018

Hibberd, J. (2019). The Imposter Cure: How to stop feeling like a fraud and escape the mind-trap of imposter syndrome. Aster.

Higgs, J., & McAllister, L. (2007). Educating clinical educators: Using a model of the experience of being a clinical educator. Medical Teacher, 29(2-3), e51-e57. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590601046088

Hutchins, H. M., Penney, L. M., & Sublett, L. W. (2018). What imposters risk at work: Exploring imposter phenomenon, stress coping, and job outcomes. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 29(1), 31-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21304

Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 764-791. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667055

Kulkarni, M. (2019). Holding on to let go: Identity work in discontinuous and involuntary career transitions. Human Relations, 73(10), 1415-1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719871087

Leonhardt, M., Bechtoldt, M. N., & Rohrmann, S. (2017). All impostors aren’t alike – Differentiating the impostor phenomenon. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01505

Lieff, S., Baker, L., Mori, B., Egan-Lee, E., Chin, K., & Reeves, S. (2012). Who am I? Key influences on the formation of academic identity within a faculty development program. Medical Teacher, 34(3), e208-215. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.642827

Mak, K. K. L., Kleitman, S., & Abbott, M. J. (2019). Impostor phenomenon measurement scales: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00671

Mayrhofer, W., & Iellatchitch, A. (2005). Rites, right? The value of rites de passage for dealing with today’s career transitions. Career Development International, 10(1), 52-66. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430510577628

Neureiter, M., & Traut-Mattausch, E. (2016). Inspecting the dangers of feeling like a fake: An empirical investigation of the impostor phenomenon in the world of work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1445. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01445

O’Sullivan, P. S., & Irby, D. M. (2014). Identity formation of occasional faculty developers in medical education: A qualitative study. Academic Medicine, 89(11), 1467-1473. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000374

O’Sullivan, P. S., Steinert, Y., & Irby, D. M. (2021). A faculty development workshop to support educator identity formation. Medical Teacher, 43(8), 916-917. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1921135

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Scoping Reviews. In E. Aromataris., & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Petersen, N. (2017). The liminality of new foundation phase teachers: Transitioning from university into the teaching profession. South African Journal of Education, 37(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n2a1361

Ranmuthugala, G., Plumb, J. J., Cunningham, F. C., Georgiou, A., Westbrook, J. I., & Braithwaite, J. (2011). How and why are communities of practice established in the healthcare sector? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Services Research, 11, 273. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-273

Robinson-Walker, C. (2011). The imposter syndrome. Nurse Leader, 9(4), 12-13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2011.05.003

Sethi, A., Schofield, S., McAleer, S., & Ajjawi, R. (2018). The influence of postgraduate qualifications on educational identity formation of healthcare professionals. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23(3), 567-585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-9814-5

Stone, S., Ellers, B., Holmes, D., Orgren, R., Qualters, D., & Thompson, J. (2002). Identifying oneself as a teacher: The perceptions of preceptors. Medical Education, 36(2), 180-185. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01064.x

Talisman, N., Harazduk, N., Rush, C., Graves, K., & Haramati, A. (2015). The impact of mind-body medicine facilitation on affirming and enhancing professional identity in health care professions faculty. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 780-784. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000720

The Joanna Briggs Institute (Ed.). (2017). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

Tricco, A. C., Soobiah, C., Antony, J., Cogo, E., MacDonald, H., Lillie, E., Tran, J., D’Souza, J., Hui, W., Perrier, L., Welch, V., Horsley, T., Straus, S. E., & Kastner, M. (2016). A scoping review identifies multiple emerging knowledge synthesis methods, but few studies operationalize the method. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 73, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.030

Vergauwe, J., Wille, B., Feys, M., De Fruyt, F., & Anseel, F. (2015). Fear of being exposed: The trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 565-581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9382-5

Villwock, J. A., Sobin, L. B., Koester, L. A., & Harris, T. M. (2016). Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: A pilot study. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, 364-369. https://dx.doi.org/10.5116%2Fijme.5801.eac4

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and Social Learning Systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice (pp. 179-198). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11

*Kirsty J Freeman

Duke-NUS Medical School

8 College Road,

Singapore 169857

Tel: +65 89219676

Email: kirsty.freeman@duke-nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.