Fixing the leaky pipeline: Tips to promote gender equity in Academic Medicine

Submitted: 18 December 2020

Accepted: 12 April 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 1-6

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/GP2451

Dora J. Stadler1,2, Halah Ibrahim3,4, Joseph Cofrancesco Jr4 & Sophia Archuleta5,6

1Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, Doha, Qatar; 2Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, United States of America; 3Department of Medicine, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 4Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, United States of America; 5Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 6Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Gender equity in academic medicine is a global concern. Women physicians lag behind men in salary, research productivity, and reaching top academic rank and leadership positions.

Methods: In this Global Perspective, we provide suggestions for overcoming gender bias, drawn from a multidisciplinary literature and personal experiences working as clinician educators in the international academic arena. These suggestions are not exhaustive but inform a tool kit for institutions and individuals to support the advancement of women in academic medicine.

Results: Barriers include limited access to same gender role models and mentors, fewer networking opportunities, fewer nominations for awards and speakership opportunities, as well as implicit gender bias. Institutional interventions can address disparities along the career continuum focusing on scholarship, promotion and leadership opportunities. Women faculty can also seek out professional development programmes and mentorship to support their own advancement. Informal and formal networking opportunities, using a variety of platforms, including social media, can help build relationships to enhance career development and success, and provide social, emotional and professional support to women at all stages of their career. The National University Health System’s Women in Science and Healthcare project is an example of a successful group formed to empower women and foster personal and professional development.

Conclusion: Successful incentives and policies need to consider local institutional and cultural contexts, as well as approaches to mitigate implicit bias. Achieving gender parity in academic medicine will promote a personally and professionally fulfilled global healthcare workforce to improve patient care and clinical outcomes worldwide.

Practice Highlights

- The gender gap in academic medicine persists worldwide, especially at higher academic rank & leadership positions.

- Institutions should develop strategies to address gender equity in faculty recruitment, retention & advancement.

- Female faculty can help to advance themselves and each other through seeking self-development, mentorship and networking opportunities, utilising local as well as global resources available through a variety of channels, including social media.

- Women faculty groups can facilitate networking opportunities and create a critical mass of individuals, who can provide effective personal and professional support.

I. THE STATE OF GENDER EQUITY IN INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC MEDICINE

Gender inequity in academic medicine has been a global concern for several decades. Although the enrolment of women in medical schools has reached or exceeded parity in many parts of the world, disparities remain in academic rank, career advancement, and leadership positions internationally (Stadler et al., 2017). Women faculty lag behind their male colleagues in several domains, including salaries, research productivity, and resource allocation. Various terminologies have been used to describe this phenomenon, including the leaky pipeline, sticky floor, broken rungs, and glass ceiling. Regardless of the phrasing, the outcome remains the same – the gender gap persists, particularly at the highest academic ranks and in medical leadership positions. As recent studies have linked physician female gender to improved patient clinical outcomes, hospitals and academic institutions now have additional incentives to train and retain a diverse workforce.

Though much of the literature on gender disparity in academic medicine is Western-based, global studies also document ongoing inequity. For example, a comparative study in Scandinavian countries found significantly fewer women in higher income specialties and in leadership positions, despite policies and cultural attitudes that support and promote work-life balance. Even in countries, such as Russia, where the majority of the physician workforce is comprised of women, the authors found significantly fewer women in prestigious specialties, tertiary care and academic medicine. In a multinational study of newly accredited postgraduate training programs in Singapore, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, women comprised 25% of the clinician educator workforce and only 18% of hospital CEO/ CMOs, and were significantly less likely to hold an academic appointment (Stadler et al., 2017).

There are multiple barriers to female physician advancement, including limited access to same gender role models and mentors, fewer networking opportunities, lower salaries, less funding and resources (administrative staff, laboratory space), and fewer nominations for awards and conference speakership opportunities (Ibrahim et al., 2019a). These disadvantages start early in a female physician’s career and continue throughout her education, training and employment and, ultimately, impact her career trajectory. The cause is multifactorial, but there is a large body of literature that suggests that implicit gender biases play a significant negative role in the recruitment, retention and promotion of female physicians. Gender stereotype threat, which goes beyond how women are perceived and evaluated, and affects how they actually perform, could further augment disparity. There is currently a dearth of literature on successful initiatives to improve gender equity in the international arena and further research is needed to identify effective interventions in local contexts. Given the complexity of the underlying causes of gender inequity, initiatives to advance women in academic medicine should be comprehensive and multi-pronged, and include both institutional and individual interventions.

II. INSTITUTIONAL INITIATIVES

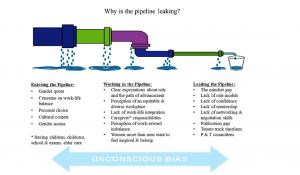

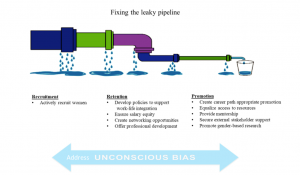

International academic institutions can vary considerably in faculty gender composition, resources available, and institutional culture. International medical education is evolving, and now is the time for healthcare institutions to assess the diversity of their faculty and review policies and protocols for any evidence of systemic bias, as well as formally assess organisational climate. The leaky pipeline model offers a framework to address these issues along the continuum of a female physician’s career. First, explicit policies to recruit, hire and retain more female academic faculty are necessary. Institutions need to analyse their current status and set goals for improvement (Ibrahim et al., 2019b), and need to ensure equity in advancement, with a focus on success in scholarship, promotion and leadership. Contributors to the leaky pipeline and a summary of possible approaches to resolve issues are described in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1. Barriers to recruitment, retention, and advancement

Figure 2. Institutional strategies to support female faculty recruitment, retention and promotion

Implicit or unconscious bias affects all aspect of this process; therefore, continued training to recognise and mitigate its effects is vital to success. Effective institutional policies for recruitment of a diverse faculty have included bias training for members of search and promotion committees, ensuring committee diversity (representative of gender, minorities and clinical tracks), as well as accountability through tracking of female faculty applicants and hires. Successful initiatives for retention of faculty have focused on development of policies that facilitate work-life balance and integration, such as part-time work, job sharing, and on-site childcare. The facilitation of an institutional culture that makes these options accessible without fear of stigma or penalty is crucial for these programs to succeed. Transparency in policies and salaries, systematic review and adjustment of pay structure, as well as offering negotiation workshops for female faculty, have all been shown to be successful in equalising the salary gap. Formal institutional support in terms of funding, space, time allotment, and interdepartmental activities to foster collaboration can boost research productivity and decrease isolation reported by female academic faculty. Structured professional development for faculty at all career levels, with a family friendly schedule, can be a positive factor in women physicians’ career satisfaction and retention.

Institutional review and focus on parity in advancement can help to identify and fix the ‘broken rungs’ on the ladder to promotion and leadership positions for women. Adjusted promotion and tenure guidelines to account for childcare and part-time work are also integral to advancement. While many of these recommendations are based on literature from Western academic institutions, the overall framework and guiding principles can be adapted globally. Further, gender-based research in international academic institutions is needed to better address inequity and barriers in local contexts.

III. INDIVIDUAL INITIATIVES

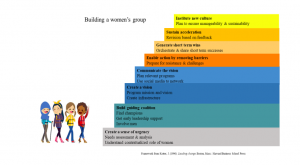

Institutional change is a long-term process and transforming institutional culture can take time. Despite the systemic gender bias, women physicians can take proactive steps to advancement. Women physicians face a set of internal challenges such as their own implicit bias, susceptibility to gender stereotype threat that can affect performance, and higher rates of imposter syndrome. Individual faculty members can seek out and request to participate in faculty development programs that support addressing these topics, as well those that support career advancement. Women can seek mentors and sponsors at their own or other institutions through local, regional and national networks. In addition to structured faculty development and formal mentorship processes, networking, a less formal relationship, can be utilised to support female faculty. Networking, a process used to build, maintain and use relationships to enhance career development and success, can provide social, emotional and professional support to women at all stages of their career. It can also combat professional and personal isolation often experienced by female faculty. In today’s globally dispersed and pandemic affected medical communities, the power of social media cannot be undervalued. Social media platforms can be used to form communities to share knowledge, address isolation, facilitate networking, and provide mentoring (Ibrahim et al., 2020). These platforms also serve as effective venues to broadcast and celebrate accomplishments. Networking can occur through individual channels and through grassroots efforts to build a community of women with shared goals and interests. A useful guide to building an international women’s group to facilitate and support female physician networking is illustrated in Figure 3 and exemplified through the following project.

Figure 3. Framework for building a women’s group

IV. AN EXAMPLE OF SUCCESS IN THE LOCAL ARENA: THE WISH PROJECT

Solutions to achieve meaningful change require multidimensional and comprehensive strategies. However, there is limited information in the medical literature about developing or running an academic women’s group, especially in the international arena where policies and support systems for gender parity may be lacking. Often, a “bottom-up” approach, by women for women, is needed. Therefore, in 2017, to help the advancement of women at our institution, we formed the National University Health System Women in Science and Healthcare (NUHS WISH), dedicated to empowering and supporting women in healthcare and science fields in the NUHS ecosystem (Yoong et al., 2019). We viewed this group as more than a social opportunity, but rather as a vehicle for women’s empowerment. Borrowing from a multidisciplinary literature on group formation and change management, we structured our initiative according to John Kotter’s 8-step process of transformational change, as seen in Figure 3. First, we assembled a small team of passionate and dedicated women who served as transformation leaders. With the simple mission of supporting the personal and professional advancement of women in healthcare, the team communicated their vision through word of mouth and social media. Next, the transformation leaders worked with institution leadership to highlight and address barriers to female advancement in healthcare. We shared short-term wins, and planned for the future. Viewing the women’s group as an opportunity for culture change, rather than a single initiative, encourages sustainability and innovation. We deliberately alternated informal social gatherings and formal structured events. Workshops were planned for women at all career stages, with specific focus on the development of skills essential for success in healthcare, including leadership and mentorship. Given the varied professions and career stages of the members, we provided early career professionals the opportunity to network with experienced women, who offered career-related and other advice. Senior members benefitted from interacting with individuals in key leadership positions. WISH is now in partnership with senior leadership, and has grown to be a strong group of empowered female health professionals. We believe this network of developmental relationships is critical for the retention and success of women in academic medicine.

In conclusion, ensuring gender equity should be an important goal for academic medicine institutions worldwide. Our recommendations are based on personal experiences, as well as a review of best practices. The suggestions are not exhaustive and we are cognisant that no single model fits all institutions; culture and context must always be considered. Nonetheless, we believe that multilevel, institution-wide approaches to support the advancement of female faculty will benefit the institution as a whole, and help to foster inclusivity and equality in the international medical workforce. Women can also create structures to help support their advancement. By supporting all healthcare professionals to reach their full potential, we can strive for a personally and professionally fulfilled global healthcare workforce to improve patient care and clinical outcomes worldwide.

Notes on Contributors

Dora J. Stadler conceived the manuscript design, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. Halah Ibrahim reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript, Joseph Cofrancesco Jr. advised the manuscript design and gave critical feedback to the manuscript. Sophia Archuleta conceived the manuscript design, reviewed the literature and gave critical feedback to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Siok Ching Chia, BS, National University Hospital for her assistance in preparing the manuscript for submission.

Funding Statement

There were no funding sources for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Ibrahim, H., Abdel-Razig, S., Stadler, D. J., Cofrancesco, J., Jr., & Archuleta, S. (2019a). Assessment of gender equity among invited speakers and award recipients at US annual medical education conferences. JAMA Network Open, 2(11), e1916222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16222

Ibrahim, H., Stadler, D. J., Archuleta, S., Anglade, P., & Cofrancesco, J., Jr. (2019b). Twelve tips for developing and running a successful women’s group in international academic medicine. Medical Teacher, 41(11), 1239-1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1521954

Ibrahim, H., Anglade, P., & Abdel-Razig, S. (2020). The use of social media by female physicians in an international setting: A mixed methods study of a group WhatsApp chat. Women’s Health Reports, 1(1), 60-64. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2019.0015

Stadler, D. J., Archuleta, S., Ibrahim, H., Shah, N. G., Al-Mohammed, A. A., & Cofrancesco J., Jr. (2017). Gender and international clinician educators. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 93(1106), 719-724. http://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134599

Yoong, J., Alonso, S., Chan, C. W., Clement, M.-V., Lim, L. H. K., & Archuleta, S. (2019). Investing in gender equity in health and biomedical research: A Singapore perspective. The Lancet, 393(10171), e21-e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32096-8

*Sophia Archuleta

1E Kent Ridge Road

NUHS Tower Block, Level 10

Singapore 119228

Tel: +65 6772 6188

Email: sophia@nus.edu.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.