“Exploring Milestones”: Harnessing active learning in the undergraduate paediatrics curriculum

Submitted: 25 January 2024

Accepted: 20 December 2025

Published online: 1 April, TAPS 2025, 10(2), 46-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-2/OA3228

Chhaya Divecha1, Miriam Simon2 & Ciraj Mohammed3

1Department of Paediatrics, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman; 2Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Science, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman; 3Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Oman

Abstract

Introduction: Paediatric milestones provide a structured method for observing and monitoring a child’s progress and should be part of core paediatric curriculum. However, a literature review reveals that primary care physicians and pediatricians feel inadequate about their knowledge and practice of developmental paediatrics, thus exposing the lacunae in training.

Methods: An intervention was planned amongst final-year medical undergraduate students in Oman during their paediatric rotation. A 90-minute multimodal active learning module incorporating diverse learning orientations was planned and administered as a skill-lab session. Its effectiveness in learner motivation, engagement, and faculty participation was evaluated using a questionnaire based on the ICAP (Interactive, Constructive, Active, and Passive) framework, administered to students at the end of the session.

Results: Responses of the 62 participants indicated a significant association between their overall experience and tasks related to the active, constructive, and interactive elements of the module (p=0.001). The faculty’s role in facilitating the session significantly contributed to students’ overall experience (p=0.000). On linear regression, active, constructive, and interactive components of the module were moderate to high predictors of the participants’ overall learning experience.

Conclusion: It was beneficial to base the teaching module on established learning theories. Active learning strategies proactively fostered student engagement and self-directed learning during the session. Faculty played an important role in planning and customising the content, flow, and delivery to maximise meaningful learning. Such interactive collaboration, especially for theoretical concepts in medicine, enables better student engagement, providing enhanced opportunities for learning, practice, and feedback.

Keywords: Active Learning, Child Development, Undergraduate Medical Education, Student Engagement, ICAP Framework

Practice Highlights

- Active learning strategies can foster student engagement in teaching paediatrics.

- The use of interactive collaboration for theoretical concepts in medicine is effective.

- The role of faculty is crucial to maximise meaningful student learning.

- Utilisation of learning theories to design modules is beneficial for successful content delivery.

I. INTRODUCTION

Clinical curriculum while preparing students for patient care frequently focuses on abnormal pathologies with normal development or physiology often being neglected or underemphasised (Densen, 2011). Developmental and behavioral paediatrics are integral components of pediatric clinical practice. Paediatric milestones provide a structured method to monitor a child’s progress with a comprehensive understanding of development across all domains (gross motor, fine motor, language, and social) and thus must be adequately addressed in the core paediatrics curriculum. However, review of literature reveals that primary care physicians and paediatricians feel inadequate about their knowledge and practice of developmental paediatrics, thus exposing the gaps in education and training (Bauer et al., 2009; Beggs et al., 2005; Bright et al., 2019; Chödrön et al., 2021; Comley et al., 2008; Honigfeld et al., 2012).

Large group didactic classrooms often involve passive reception, leading to lack of engagement among learners (Huggett & Jeffries, 2021). Undergraduate medical curriculum is transitioning from a passive, teacher-centered approach to a learner-centered, active learning strategy, which has demonstrated enhanced students’ understanding, retention of complex concepts, improved student motivation, and overall course satisfaction (McCoy et al., 2018; O’Sullivan et al., 2022). Innovative active learning approaches on developmental milestones largely employ live visits to community resource sites along with instructional videos, reflective reports, observing live parent-child pairs, and use of short video clips (Clark et al., 2012; Comley et al., 2008). In addition, interactive DVDs containing animated cartoons and questions, live interviews, case vignettes, case write-ups, stimulus videos, observation experiences, discussion groups, field trips, and personal experiences have been documented as teaching-learning strategies (Fox et al., 2007; Leiner et al., 2011). Digital resources such as “Beyond Milestones”, developed as free online material for medical professionals using real-life developmental assessments, have shown improved scores on knowledge, observational expertise, confidence, and learner satisfaction (Connolly et al., 2014).

Though observing children in real-life scenarios (including wards, outpatient departments, well-baby clinics, schools, community centers, etc.) creates opportunities for interactive and authentic learning, restrictions in availability of exposure, time, and faculty, especially during the COVID pandemic have compounded the woes of clinical training. The aforementioned reasons prompted us to develop an active learning module using the ICAP framework to introduce developmental milestones in the paediatric curriculum. This framework identifies four modes of cognitive engagement in active learning: Interactive (I), Constructive (C), Active (A), and Passive (P). Passive modes of cognitive engagement involve receipt of information, compared to active modes which require learners to physically manipulate information provided (Chi & Wylie, 2014). Engagement further increases in the constructive mode as students generate diagrams, questions, etc., and is maximum in the interactive mode where peers collaborate and co-construct knowledge through the process of questioning and responding during a conversation. Research reveals that learning achievement is lowest at P and increases in the order of A, C, and I (Chi & Wylie, 2014). Given that the ICAP framework involves both interactive and active learning, we hypothesised that its application to the education of developmental milestones would further promote and expand learning and performance of undergraduate medical students. Additionally, it would help identify and address gaps in their knowledge and understanding of developmental milestones.

In this study, we developed an innovative learning module for developmental milestones using the ICAP model. The module was active, interactive, experiential, and grounded in the major theories of learning (behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, humanism, and social learning theories) to maximise opportunities for learning. This pilot study aimed at testing the effectiveness of the module in terms of learner motivation, engagement, and faculty participation.

II. METHODS

The current study was conducted at a private medical college in Oman. It was a cohort study with a quantitative survey and qualitative component. Final-year undergraduate medical students doing their 6-week clinical rotation in Paediatrics were introduced to the teaching module during their skill-lab session (in groups of 6 to 8 students). Verbal consent was obtained for learner feedback.

The learning session was planned and conducted by faculty researchers with expertise in paediatrics, developmental psychology, and medical education. The learning outcomes of this module on developmental milestones were:

- To identify age-appropriate milestones in children from birth to 5 years of age.

- To apply knowledge of milestones for various domains (gross motor, fine motor, language, and social/cognitive) to assess development in various age groups (birth to 5 years).

- To differentiate between normal and delayed development in children.

The specific learning outcomes were addressed through various strategies as summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart depicting the sequence of activities mapped with specific learning objectives

The module was planned for 90 minutes and included learning activities based on principles of active and adult learning. Pre-reading material for the multimodal active learning session on developmental milestones was provided (https://aqmedia.org/filestore/2/0/3/6_83bcb34c55b2770/6302_012d2ba650720b8.pdf). Various constructs that underpin major learning theories were adopted while designing the learning approaches which are detailed here:

A. Lid Opener and Think Pair Share

Having a child with a disability can profoundly affect family dynamics, resulting in psychosocial challenges like parental stress, social isolation, mobility limitations, child behavioral issues, and difficulties in coping and adjustment (Woolfson, 2004). Students were shown a short video of a child with developmental delay and its psychosocial impact on the child and family. They were then divided into pairs/groups and asked to reflect on the video in terms of how watching the video made them feel, what they believed the child and family might be going through, and why an awareness of typical developmental milestones is important. Following group discussion, one representative from each group shared the pertinent points that emerged with the larger group.

B. Discourse

The session covered fundamentals related to detection of milestones in children from birth to 5 years of age through a lecturette by faculty from the Paediatrics Department.

C. Exploration via Self-directed Learning Activity

During this section, students were briefed about the interactive activity and divided into two sub-groups (3 to 4 members per group). An instruction sheet explaining the activity was provided. A group leader for each sub-group was identified to monitor group dynamics and ensure active participation. The ‘Paediatric Developmental Milestones Interactive Table’ from Aquifer Pediatrics website’s free student resources was shown on a smart board. The table involved a grid of milestones (gross motor, fine motor, communication/social, cognitive/adaptive) against ages (2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 15 months, 18 months, 24 months, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, 5 years). Students explored their knowledge of the milestones by clicking on each square and further reinforced it by double clicking (which would show appropriate video clips of 2 to 8 seconds). During this activity, learners engaged in self-directed learning through the use of the interactive table to compare milestones in various domains across age groups.

D. Case-Based Learning (CBL)-Trigger and Buzz Groups

Following the SDL activity, students were led into Case-Based learning, where they were shown a video of a child undergoing developmental assessment by a doctor. They were asked to identify milestones and estimate the developmental age of the child. To prompt further discussion, a buzz group format in small groups was employed to discuss their findings. The facilitator moved around to help and encourage participation in group discussions. After that, the sub-groups presented their findings to the entire group, which sparked additional discussion and feedback.

E. Game-Based Learning

The acquired knowledge of milestones was further intensified through gamification. A game of BINGO was played, where each student received a bingo ticket with pictures of milestones (sample in Figure 2). The facilitator drew cards from the bingo pile (with age and domain) and students were asked to identify the appropriate milestone picture for that age/domain on their ticket. The first one to get a line of 5 pictures (horizontal/vertical/ diagonal) was declared the winner.

Figure 2. Sample of bingo ticket with milestones

F. Scaffolding

The faculty would wrap up the case and summarise major learning points thus consolidating the knowledge about milestones. Throughout the learning session, the facilitator provided cognitive scaffolding by leading the students through different questions, prompts, tasks, and structured interactions enabling them to learn more about developmental milestones. Students had opportunities to work with their existing knowledge and build further on it through the various learning activities, group discussions and faculty-led facilitation.

G. Reflection on Action

Students were divided into groups (2 or 3 students per group) to reflect on their entire learning experience using Borton’s model of reflection (Rolfe, 2014). Their reflections elucidated the “what”- their experience of the activities, “so what”- how the module improved on their prior knowledge and understanding about the topics and “now what”- providing suggestions for improvement and preference for similar active learning strategies in future sessions. Individual sharing within groups was followed by sharing between groups via their representatives.

H. Data Collection and Analysis

Students were asked to complete a feedback form about their learning experience during the activity via an anonymised electronic feedback form administered at the end of the session. The form had 15 items evaluating their learning experience – 11 quantitative (Likert scale-based) and 4 qualitative questions. The quantitative feedback responses were analysed based on the four domains of the ICAP model- questions were framed for Interactive, Constructive, Active, and Passive engagement of students during the active learning strategies. There were 4 items (Max score=20) about the interactive components of the module, 3 items (Max score=15) based on constructive elements, and two items each (Max score=10) on the active and passive engagement of students during the module. In addition, 4 quantitative items assessed feedback on faculty involvement and students’ overall experience.

Data was analysed using IBM’s Statistical Package for Social Studies (SPSS 22; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistical methods such as percentages, mean and standard deviation were employed. Cronbach’s alpha method was used to assess internal consistency/test reliability. The Shapiro-Wilk method was used to test normality. Inferential statistical methods such as the Spearman’s correlation analysis and Chi-square test were used to explore significant associations between variables. Linear regression was also used to explore various predictors of the participants’ learning experience. Thematic analysis was performed for qualitative feedback.

III. RESULTS

A. Overview of Study Participants

A total of 62 students from the final clinical year of the MD program participated in this study; 91% were females and 9% were males. The average age of participants was 24.4 years (SD=0.707).

Results indicate high internal consistency for the survey items developed. Full scale (15 items) Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.808 was obtained. Results of the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality for all survey items (p=0.000) indicate that participant’s responses were not normally distributed. Non-parametric tests were thus employed for data analyses.

B. Analysis of Learner Feedback

In general, participants agreed that the session on developmental milestones was enjoyable.

The preference for game-based interactive/collaborative learning was high. The learner responses categorised item wise are provided in Table 1.

|

Item |

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Can’t say |

Disagree |

Strongly Disagree |

Mean |

SD |

|

The pre-reading material on developmental milestones was easily understandable

|

59.7% |

35.5% |

4.8% |

0 |

0 |

4.548 |

0.591 |

|

The session established clear learning outcomes and objectives.

|

91.9% |

8.1% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.919 |

0.274 |

|

The case-based activity on developmental milestones provided relevant opportunity to witness theory in practice.

|

83.9% |

16.1% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.839 |

0.370 |

|

Presentation of real-world contexts followed by discussion in groups helped me learn better.

|

88.7% |

9.7% |

1.6% |

0 |

0 |

4.871 |

0.383 |

|

The game-based activity enabled me to build an emotional connection to learning and the subject matter.

|

82.3% |

16.1% |

0 |

1.6% |

|

4.790 |

0.516 |

|

This session provided me opportunities for feedback and practice

|

83.9% |

16.1% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.839 |

0.370 |

|

I enjoyed the session on developmental milestones as it actively engaged me with the course material through case study and discussion.

|

87.1% |

12.9% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.871 |

0.338 |

|

The session assisted us in organising our thoughts, reflecting on our understanding, and finding gaps in our reasoning.

|

74.2% |

21% |

4.8% |

0 |

0 |

4.694 |

0.560 |

|

I prefer similar sessions to learn theoretical concepts in paediatrics and medicine.

|

88.7% |

9.7% |

1.6% |

0 |

0 |

4.871 |

0.383 |

|

Today’s session was well-planned and helped me work on my own to accomplish learning goals independently.

|

82.3% |

17.7% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.823 |

0.385 |

|

The faculty supported students in the learning process during the session.

|

98.4% |

1.6% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.984 |

0.127 |

|

The faculty regulated the level of information and maintained my ability to be responsible for my learning.

|

87.1% |

11.3% |

1.6% |

0 |

0 |

4.855 |

0.398 |

|

The session made me identify psychosocial issues associated with developmental delays

|

69.4% |

21% |

8.1% |

1.6% |

0 |

4.581 |

0.714 |

|

I found myself motivated, engaged and self-directed during the entire session.

|

82.3% |

14.5% |

3.2% |

0 |

0 |

4.790 |

0.483 |

|

Using the interactive online module to explore developmental milestones helped improve my learning in this area. |

66.1% |

25.8% |

6.5% |

1.6% |

0 |

4.565 |

0.692 |

Table 1. Analysis of survey responses based on dimensions of the ICAP Model

C. Analysis of Feedback on Faculty Involvement and Overall Experience

The mean score on the participants’ feedback on the involvement of faculty members during the session was 9.839 (SD=0.450) and their overall experience was 9.710 (SD=0.686).

D. Association among Various Survey Dimensions

Results indicated significant associations between learner’s overall experience and tasks related to the active component of the session (p=0.000), constructive engagement (p=.000), and interactive collaboration with peers (p=0.001). Results also indicated significant associations between the interactive and constructive components of the session (p=0.000), faculty’s role in facilitating the session and students’ overall experience (p=0.000), and faculty involvement with the passive component (designing the initial reading material) (p=0.000).

E. Spearman’s Correlation

Spearman’s correlation across the various survey dimensions based on the ICAP model indicated high positive inter-dimension correlation. A significant correlation was also seen between the survey dimensions and the full-scale scores.

F. Linear Regression

Linear regression analysis was carried out to explore various predictors of the participants’ learning experience. The active (R2=0.438), constructive (R2=0.718), and interactive components (R2=0.644) are moderate to high predictors of the participants’ overall learning experience.

G. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Items

The following themes and elaborations emerged on analysis of student feedback relating to their experience during the active learning module on developmental milestones which are summarised in Table 2.

|

Themes |

Elaboration of theme |

Samples of students’ feedback |

|

(i) Elevated learning experience

|

Participants expressed positive feedback regarding all components of the active learning session. They enjoyed the game-based activities, technology-integrated tasks, while at the same time enhancing their knowledge on developmental disorders from a clinical perspective.

|

“The bingo game brought a surprisingly fun twist to a boring topic and the competitiveness of the group as well as the doctors fun proctoring made it an overall pleasant and enjoyable experience. In short, this was a session I’m glad I got out of bed for.” “The smart board table was an active way of remembering.” “Encourage us to learn more and attend to skill lab. It was wonderful.” “A lot better than what I thought I would feel compared to a normal session. Confident to answer any questions related to developmental milestones.” |

|

(ii) Efficacious collaborative interactions

|

Students reported increased interest in learning as the session involved working together with their peers. Participants felt that continual interaction throughout the session strengthened learning.

|

“The group interactions really helped me retain the information. It was a fun experience and something new and out of the ordinary.” “Interactions made the information much easier to understand.” “It was interactive which made it interesting.” “I interacted throughout the session, learned quite a lot of information, very helpful.” |

|

(iii) Reflective outlook to patient care

|

Participants appreciated the inclusion of humanism in the learning experience. The incorporation of reflective practice in patient and caregiver experiences is a vital component that may impact future outcomes related to patient care. |

“Playing the video which wasn’t pure scientific as usual, it is emotional also, so it touches both the doctor and the human inside me.” “Watching the video of cerebral palsy and then reflecting over why development is very important.” |

|

(iv) Supportive learning environment

|

Student feedback highlighted the presence of a positive, non-judgmental environment that ensured improvement of learning in a relaxed/ stress-free setting. |

“We were able to make mistakes and learn from them without the fear of being criticised” “It was very fun and interactive. No pressure was there and not scary.” “It was interactive and very useful and most important comfortable and didn’t feel like we were being pressured and that surely helped us learn way better.” “Very happy and I enjoyed it a lot. My favourite session since the beginning of the year… no pressure was put on us, so we were able to actually learn instead of being terrified.” |

Table 2. Thematic analysis of qualitative feedback

IV. DISCUSSION

Monitoring a child’s development over time via milestones is a core part of paediatric curriculum and practice, as it enables early identification of delay or atypical progress, allowing timely referral. As an alternative to traditional learning through lectures as practiced routinely, we utilised active learning strategies that addressed multiple learning orientations for enhanced student engagement and learning.

A. Designing the Module and Active Learning Strategies based on Learning Theories

The developmental milestone module designed to involve multimodal active learning strategies has been described in the methods section. The session began with a novel “lid-opener” showing a real-life video of a child with developmental delay and the psychosocial impact of the disability on the child and family, followed by an active learning strategy; think pair and share (TPS). We explored the utility of “cognitive” orientations to learning by positioning learners to seek and understand the structure of knowledge for meaningful learning. TPS has been known to enhance the process of clinical learning by allowing students to experience different viewpoints on a particular problem and express as well as to listen to others as compared to a traditional classroom lecture (Ganatra et al., 2021; Linsenmeyer, 2021).

A significant proportion (91%) of students agreed that using the interactive module to explore milestones helped improve their learning on the topic which is also reflected in the qualitative feedback (Table 2). The interactive smart board allowed students to explore milestones in a self-directed activity and enabled higher-order cognition through active engagement with the course content. Technology in learning is stimulating for millennial learners and allows them to use online novel educational tools to maneuver their learning process (George & Dreibelbis, 2021). The wide availability of mobile devices, laptops, smart boards, etc. provides the teacher opportunities to use these new technologies effectively to transform learning into a more collaborative, personalised, and empowering experience that is rooted in connectivism- the learning theory of the digital era. We employed a multimodal approach integrating diverse activities such as videos, interactive smart boards, and gamification (via the BINGO game). Integrating many information sources nurtures the learner’s ability to reflect on connections between fields, ideas, and concepts, a core skill linked to the theory of connectivism. (Goldie, 2016).

Case-based learning (CBL) effectively links theory and practice and prepares students for actual clinical application of knowledge through inquiry (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). The hypothetico-deductive reasoning inherent to a “constructivist” framework was applied while designing this approach (Kalinowski & Pelakh, 2024). It increases the learner’s engagement and motivation for learning through creativity, challenge, interest, and enjoyment afforded through the case-study method. An important part of CBL involves problem-solving through free discussions and with often no correct or incorrect answers, thus broadening the students’ reasoning process (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). We used a CBL trigger in the form of a video demonstrating an assessment of a child’s development, allowed students analyse the video individually followed by buzz group discussions to share their understanding. All our students unanimously agreed that the case-based activity gave them ample opportunity to witness theory in practice. Buzz groups also provide an opportunity to apply contextual thinking to actual practice and develop collaborative skills. Studies have shown that buzz groups improve clinical reasoning and learning, promote teamwork, increase motivation to learn, improve academic performance through a conducive learning environment, and provide a chance for all members to participate and share their opinions within their sub-group (Abbasi et al., 2017; Balslev et al., 2015; Shrivastava, & Shrivastava, 2018). The elements of exploration and experimentation ensured that the theory of constructivism rooted in the connection of new knowledge to pre-existing knowledge was effectively utilised in the CBL process. Co-creation of this knowledge with peer interactions can be attributed to social learning theories of cognitivism and constructivism.

Selective and purposeful gamification has been known to increase learner motivation and engagement and, ultimately, learning (Rutledge et al., 2018). This was evident in our study where a vast majority (98%) of students agreed that the game-based activity helped them build an emotional connection with the process of learning and concepts being learned, which is also reflected in the qualitative feedback (Table 2). Game-based learning (GBL) builds emotional connections by immersing learners in engaging and interactive environments. These environments evoke emotions such as curiosity, excitement, and empathy, which enhance motivation and deepen the learning experience (Loderer et al., 2020). Based on constructivist theory, the game-based activity integrated their knowledge of age-appropriate milestones with a fun-based BINGO theme. The instant feedback that served as formative assessment in this segment had a behaviorist orientation that is specific and quantifiable.

B. Student Engagement using Multimodal Active Learning Strategies

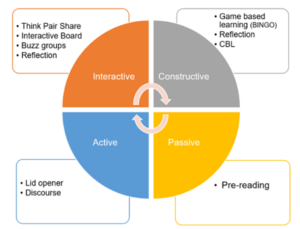

Studies have noted a preference for multi-modal learning strategies by medical students which have been shown to improve academic performance, and promote deeper learning and enquiry (Alkhasawneh et al., 2008; James et al., 2011; Lujan & DiCarlo, 2006; Nicholson et al., 2016). Different learners have different learning styles and use of a variety of strategies can engage learners synergistically. We used various active learning strategies to facilitate student engagement as shown in Figure 3 which incorporated the ICAP framework of Interactive, Constructive, Active, and Passive activities. In addition, the use of learning theories to rationalise the framing of learning objectives, selection of specific teaching-learning methods/strategies, and design of appropriate evaluation strategies ensured student engagement and meaningful learning.

Figure 3. Summary of active learning strategies used in the module based on ICAP framework

The module had more activities involving interactive and constructive domains as compared to the active and passive modes. It is known that student learning and engagement improve as they move from passive to active to constructive to interactive modes (Chi & Wylie, 2014). Significant association between overall experience and interactive collaboration with peers (p=0.001) as well as constructive engagement (p=0.000) was observed. The feedback was also structured to measure student engagement in all four behaviors. We observed high mean scores in interactive and constructive domains. Learners agreed on enough opportunities for feedback, and practice and appreciated the engagement through case studies and discussions. Effective use of multiple active learning strategies thus enabled self-directed learning and students felt that they could accomplish the learning goals independently. The results underpin the utility of behaviorism and humanism as orientations for the learning process in such activities.

C. Individual and Collaborative Learning

The combination of active learning strategies facilitated engagement at both individual and collaborative levels. Students were involved in individual learning through pre-reading, lid-opener, discourse on development, case-based learning, and game (BINGO). These activities provided opportunities to self-regulate and moderate their learning. It also allowed them to organise their thoughts and reflect on their understanding. Active learning has a positive impact on memory and knowledge transfer and hence, individual self-studying before discussion improves the effectiveness of collaboration (Beggs et al., 2005). Activities initiated with an individual thinking process were balanced by subsequent group discussions. Collaborative activities in the form of Think pair share (TPS) after lid-opener, Buzz groups after CBL learning, and interactive table enabled constructive interaction among students and exchange of information and concepts. The collaborative activities helped students work together towards problem-solving, observe both their own and another’s learning process, discover different ways of approaching a situation, and find gaps in their reasoning. It also helped to build on their team skills, leadership, clinical competence, and interpersonal communication which are core attributes of professionalism in our curriculum (Branch, 2015).

D. Faculty Involvement

Though activities in the module were planned to encourage self-directedness, faculty role in the preparation and implementation of these strategies cannot be undermined. We adopted an amalgamation of humanistic and social cognitive orientation to strengthen the relationship between quality of instructional design and outcomes, thereby influencing learning directly. Perhaps for the same reasons we found a significant association between faculty facilitation with overall learning experience (p=.000). Students felt that the faculty supported them through the learning process throughout the session (100%) and regulated information besides allowing students to be responsible for their learning (98%). There was also a significant association between faculty involvement and the passive component (pre-reading material, discourse) (p=0.00); students agreed that pre-reading material was easily understandable (95%) and clear objectives and outcomes laid down before the session facilitated their understanding (100%). It must be noted that faculty can personalise the module based on the strengths, interests, cultural competencies, and time restraints of the student. Thus, rather than delivering a “one size fits all” module, the faculty can customise the content based on the student’s needs and limitations.

Involving various sensory processes enables better processing and retention of information; thus, enhancing the learning process (Friedlander et al., 2011). As more methods are employed, they are likely to engage more senses thus improving learning. Neuroscientific rationale for constructivist cognition may be seen as a possible explanation (Dennick, 2016).

While the use of active learning techniques in undergraduate medical education is not entirely novel, our approach is distinctive in that we’ve designed an entirely active learning module addressing various orientations to student learning, which ensures individual and collaborative student engagement. The study’s primary advantage is the creation and application of a targeted educational resource to teach developmental paediatrics to undergraduate students. This not only addresses the gap in effectively integrating developmental paediatrics into the core paediatrics curriculum but also demonstrates the feasibility of using a fully active learning approach in other clinical topics. Our detailed methodology aims to assist other educators in transforming their content into interactive teaching modules. The module not only meets the institutional requirement for increasing active learning sessions in the clinical years but also addresses a broader need by offering a framework and learning strategies that can be effectively applied to different topics and courses.

We could only assess student engagement based on their perception, i.e. level 1 of the New World Kirkpatrick Model (reaction), and have not quantified their ability to learn, understand, and apply their learning which constitutes higher levels of the model (Liao & Hsu, 2019). Additional limitations include the fact that this is a pilot study, tailored to a specific context and curriculum, which may restrict its generalisability. It also does not directly compare with other learning methods and lacks long-term tracking of students.

V. CONCLUSION

Paediatric topics such as developmental paediatrics are delivered mainly through didactic orientations and fail to capture student engagement leading to poor comprehension. Our study demonstrates that medical students enjoy sessions involving multimodal active learning strategies, particularly while discussing theoretical concepts that provide opportunities for practice and feedback. Heterogeneous learning strategies which underpin various learning theories and constructs have been shown to increase student motivation and engagement, thus contributing towards retention and deep learning. The faculty have an important role in planning such modules to customise the content and delivery for successful student engagement and effective learning thereafter. The framework and active learning strategies presented in the module can be applied more broadly to other subjects adapting to the needs of other undergraduate faculty in their teaching, thus making active teaching strategies easily transferable. We recommend future research be planned to include pre- and post-session assessments or a crossover study with a control group for comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, the implementation of active learning strategies to create entirely active modules in other courses within the undergraduate medical program can be explored to assess its potential for broader applicability.

Notes on Contributors

Dr. Chhaya Divecha, Associate Professor of Paediatrics was involved in the conceptualisation and design of the study, literature search, data collection and drafting the manuscript.

Dr. Miriam Simon, Associate Professor of Behavioral Science was involved in the design of the study, analysis, interpretation of results and drafting the manuscript.

Dr. Ciraj Mohammed, Professor of Medical Education was involved in the design of the study and revised the manuscript for scientific content.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the institution’s Ethics and Biosafety Committee (NU/COMHS/EBC0036/2022).

Data Availability

Data will be made available by the authors on acceptance of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the participants for their cooperation in the study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interests.

References

Abbasi, F., Mofrad, M. N., Borhani, F., & Nasiri, M. (2017). Evaluation of the effect of training by buzz group method on nursing diagnostic skills of nursing students. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 10(1), 213-218. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-360x.2017.00045.2

Alkhasawneh, I. M., Mrayyan, M. T., Docherty, C., Alashram, S., & Yousef, H. Y. (2008). Problem-based learning (PBL): Assessing students’ learning preferences using VARK. Nurse Education Today, 28(5), 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2007.09.012

Balslev, T., Rasmussen, A. B., Skajaa, T., Nielsen, J. P., Muijtjens, A., De Grave, W., & Van Merriënboer, J. (2015). Combining bimodal presentation schemes and buzz groups improves clinical reasoning and learning at morning report. Medical Teacher, 37(8), 759–766. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.986445

Bauer, S. C., Smith, P. J., Chien, A. T., Berry, A. D., & Msall, M. (2009). Educating pediatric residents about developmental and social–emotional health. Infants & Young Children, 22(4), 309-320. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181bc4da0

Beggs, S., Sewell, J., Efron, D., & Orkin, C. (2005). Developmental assessment of children: A survey of Australian and New Zealand paediatricians. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 41(8), 444–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00664.x

Branch, W. T. (2015). Teaching professional and humanistic values: Suggestion for a practical and theoretical model. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.022

Bright, M. A., Zubler, J., Boothby, C., & Whitaker, T. M. (2019). Improving developmental screening, discussion, and referral in pediatric practice. Clinical Pediatrics, 58(9), 941–948. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819841017

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520 .2014.965823

Chödrön, G., Barger, B., Pizur-Barnekow, K., Viehweg, S., & Puk-Ament, A. (2021). “Watch Me!” Training increases knowledge and impacts attitudes related to developmental monitoring and referral among childcare providers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25(6), 980–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-03097-w

Clark, B., Andrews, D., Taghaddos, S., & Dinu, I. (2012). Teaching child development to medical students. The Clinical Teacher, 9(6), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00581.x

Comley, L., Janus, M., Marshall, D., & Niccols, A. (2008). The early years: Child development in undergraduate medical school training. Canadian Family Physician, 54(6), 876.e1-4.

Connolly, A. M., Cunningham, C., Sinclair, A. J., Rao, A., Lonergan, A., & Bye, A. M. (2014). ‘Beyond Milestones’: A randomised controlled trial evaluating an innovative digital resource teaching quality observation of normal child development. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 50(5), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12485

Dennick, R. (2016). Constructivism: Reflections on twenty-five years teaching the constructivist approach in medical education. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, 200–205. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5763.de11

Densen, P. (2011). Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 122, 48–58.

Fox, G., Katz, D. A., Eddins-Folensbee, F. F., & Folensbee, R. W. (2007). Teaching development in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 16(1), 67-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2006.07.006

Friedlander, M. J., Andrews, L., Armstrong, E. G., Aschenbrenner, C., Kass, J. S., Ogden, P., Schwartzstein, R., & Viggiano, T. R. (2011). What can medical education learn from the neurobiology of learning? Academic Medicine, 86(4), 415–420. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820dc197

Ganatra, S., Doblanko, T., Rasmussen, K., Green, J., Kebbe, M., Amin, M., & Perez, A. (2021). Perceived effectiveness and applicability of Think-Pair-Share including storytelling (TPS-S) to enhance clinical learning. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 33(2), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2020.1811094

George, D. R., & Dreibelbis, T. D. (2021). Active learning in ‘The cloud’: Using “social” technologies to expand the medical classroom. In A. Fornari & A. Poznanski (Eds.), How-to guide for active learning (pp. 85-99). Springer.

Goldie, J. G. (2016). Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Medical Teacher, 38(10), 1064–1069. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173661

Honigfeld, L., Chandhok, L., & Spiegelman, K. (2012). Engaging pediatricians in developmental screening: The effectiveness of academic detailing. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1344-4

Huggett, K. N., & Jeffries, W. B. (2021). Overview of active learning research and rationale for active learning. In A. Fornari & A. Poznanski (Eds.), How-to guide for active learning (pp. 1-7). Springer.

James, S., D’Amore, A., & Thomas, T. (2011). Learning preferences of first year nursing and midwifery students: Utilising VARK. Nurse Education Today, 31(4), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.08.008

Kalinowski, S. T., & Pelakh, A. (2024). A hypothetico-deductive theory of science and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 61(6), 1362–1388. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21892

Leiner, M., Krishnamurthy, G. P., Blanc, O., Castillo, B., & Medina, I. (2011). Comparison of methods for teaching developmental milestones to pediatric residents. World Journal of Paediatrics, 7(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-011-0269-5

Liao, S. C., & Hsu, S. Y. (2019). Evaluating a continuing medical education program: New world Kirkpatrick model approach. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences, 8(4), 266-279.

Linsenmeyer, M. (2021). Brief activities: Questioning, brainstorming, think-pair-share, jigsaw, and clinical case discussions. In A. Fornari & A. Poznanski (Eds.), How-to guide for active learning (pp. 39-66). Springer.

Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Plass, J. L. (2020). Emotional foundations of game-based learning. In J. L. Plass, R. E. Mayer, & B. D. Homer (Eds.), Handbook of game-based learning (pp. 111–151). MIT Press.

Lujan, H. L., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2006). First-year medical students prefer multiple learning styles. Advances in Physiology Education, 30(1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00045.2005

McCoy, L., Pettit, R. K., Kellar, C., & Morgan, C. (2018). Tracking active learning in the medical school curriculum: A learning-centered approach. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 5, 2382120518765135. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120518765135

Nicholson, L. L., Reed, D., & Chan, C. (2016). An interactive, multi-modal anatomy workshop improves academic performance in the health sciences: A cohort study. BMC Medical Education, 16, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0541-4

O’Sullivan, S., Campos, L. A., & Baltatu, O. C. (2022). “Involve Me and I Learn”: Active learning in a hybrid medical biochemistry first year course on an American-style MD program in the UAE. Medical Science Educator, 32(3), 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01545-6

Rolfe, G. (2014). Reach touch and teach: Terry Borton. Nurse Education Today, 34(4), 488–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.11.003

Rutledge, C., Walsh, C. M., Swinger, N., Auerbach, M., Castro, D., Dewan, M., Khattab, M., Rake, A., Harwayne-Gidansky, I., Raymond, T. T., Maa, T., & Chang, T. P. (2018). Gamification in action: Theoretical and practical considerations for medical educators. Academic Medicine, 93(7), 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002183

Shrivastava, S. R., & Shrivastava, P. S. (2018). Exploring the scope of introducing buzz group in teaching community medicine to undergraduate medical students. MAMC Journal of Medical Sciences, 4(2), 109.

Thistlethwaite, J. E., Davies, D., Ekeocha, S., Kidd, J. M., MacDougall, C., Matthews, P., Purkis, J., & Clay, D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher, 34(6), e421–e444. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.680939

Woolfson, L. (2004). Family well-being and disabled children: A psychosocial model of disability-related child behaviour problems. British Journal of Health Psychology, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910704322778687

*Dr. Miriam Simon

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

College of Medicine and Health Sciences

National University of Science and Technology

PO Box 391; PC 321

Sohar, Sultanate of Oman

+96826852039

Email: miriamsimon@nu.edu.om

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.