Embracing doctors as teachers: Evaluating the student-led near-peer teaching at transnational campus

Submitted: 31 July 2024

Accepted: 24 February 2025

Published online: 1 July, TAPS 2025, 10(3), 37-48

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-3/OA3473

Kevin Xuan Hong Tang1, Koon Kee Teo1 & Kye Mon Min Swe2

1Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia (NUMed), Malaysia; 2Department of Research, Faculty of Medicine, Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia (NUMed), Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: Every medical graduate is expected to fulfil the teaching responsibilities stated by the General Medical Council (GMC). It is beneficial to nurture both teaching motivation and skills early in the undergraduate program. This study aims to evaluate the outcomes of final-year medical students as near-peer teachers in a student-led near-peer teaching program and their fulfilment of the educational responsibilities stated by the GMC.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among the year 5 medical students who participated in the Peer Teaching Program. A structured post-participation 6-point Likert scale questionnaire with written consent was distributed to the near-peer teachers to assess their perspectives on skills enhancement, motivation, and career direction. Additionally, the Peer Tutor Assessment Instrument questionnaires were distributed to the near-peer students to evaluate the performance of the near-peer teachers in five areas: responsibility and respect, information processing, communication, critical analysis, and self-awareness.

Results: There were 28 near-peer teachers, and 49 near-peer students participated in the study. The near-peer teachers score the highest in skills (5.36 ± 0.53), followed by motivation (5.16 ± 0.60) and career direction (4.79 ± 0.82). Three quarters of the near-peer teachers considered teaching to be their future primary career path after experiencing this teaching experience (4.36 ±1.34). Generally, the near-peer teachers were highly evaluated by the near-peer students across all domains (5.06 ± 0.51).

Conclusion: Overall, the near-peer teaching programme likely improved the final-year medical students in fulfilling the “Doctors as Teachers” responsibilities outlined by the GMC.

Keywords: Near-peer Teaching, Medical Students, Undergraduate Medical Education, General Medical Council, Doctors as Teachers

Practice Highlights

- Near-peer teachers are likely improved in skills enhancement, motivation and career direction.

- Sex and students’ background are not associated with the perceived outcomes of near-peer teachers.

I. INTRODUCTION

One of the aspects of Good Medical Practice outlined by the General Medical Council (GMC) for all medical professionals is to “be willing to offer professional support to colleagues, including students, through teaching” (General Medical Council, 2023). The role of doctors as teachers has been widely recognised as they need to teach and educate juniors, students and even patients (General Medical Council, 2011, 2015, 2023). On average, junior doctors spend around 80 minutes per day teaching medical students (Busari et al., 2002). This task is daunting for every new medical graduate who has just begun their UK foundation programme. They need to assume this responsibility with minimal formal training and preparations (Pierce et al., 2024; Qureshi et al., 2013).

Therefore, it is beneficial to motivate medical graduates to teach and equip them with appropriate teaching skills as early as their undergraduate programme (General Medical Council, 2011; Knobloch et al., 2018). Near-peer teaching involves students one or more academic years ahead teaching their peers or junior students (De Menezes & Premnath, 2016; Ten Cate & Durning, 2007; Yu et al., 2011). This has long been thought of as a programme to be incorporated into the medical curriculum to optimise teaching qualities and to produce more competent and knowledgeable doctors in the future (Botelho et al., 2022; Burgess et al., 2014; Zheng & Wang, 2022). Generally, medical schools provide a safe space for medical students to practice, correct and improve their teaching and pedagogical skills (Hardie et al., 2022). Most medical students feel less daunted and more supported involved in teaching their near-peer students (Yu et al., 2011).

To address this gap of insufficient teaching opportunities, most medical schools provide near-peer teaching programmes for their medical student (Frearson & Gale, 2017). However, most of the near-peer teaching programmes are carried out formally with structured guidance and training (General Medical Council, 2011), be it in the form of the Peer Assisted Learning Scheme (PALS) student-selected components (SSC) (Furmedge et al., 2014; Hettle & Morgan, 2019; Ross & Cameron, 2007; Ten Cate & Durning, 2007) or Doctors as Teachers and Educators training course (Cook et al., 2010; General Medical Council, 2011). Little is known about the outcomes of the student-led, student-run, near-peer teaching (NPT) programme in medical schools.

In the academic year 2023/2024, the Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia (NUMed) final-year medical students were involved as near-pear teachers in an NPT programme. This study thus aims to evaluate the outcomes of participation of the final year medical students as near-peer teachers in the student-led near-peer teaching programme and to determine whether the soon-to-be medical graduates can fulfil the “Doctors as Teachers” responsibilities stated by the GMC.

II. METHODS

The NPT Programme was a purely student-led, student-run 3-month teaching programme which provided additional focus on the learning outcomes of the third-year medical curriculum. This programme functioned as an adjunct to the formal curriculum and provided precious opportunities for final-year medical students to improve their teaching skills.

Before the academic year started, invitation email was sent out to recruit final-year medical students to participate voluntarily as the near-peer teachers and the year 3 medical students as the near-peer students. A total of 51 final-year medical students and 100 year 3 medical students signed up for this programme. The near-peer students were randomly assigned to groups of 5 to 6 each, and each group was guided by 3 near-peer teachers. Before the programme commenced, all near-peer teachers were required to attend a mandatory online training course conducted by the lecturers to enhance their presentation and teaching skills.

This programme comprised a total of twelve teaching sessions spanning twelve weeks, covering four sessions of Essential Clinical Placement teaching sessions, four sessions of Case-Based Discussion, one surgical teaching topic and case-based session, one Single Best Answer practice session, one Written Prescribing Exam (WRISKE) session and one Objective Structural Clinical Examination (OSCE) session. Most sessions were delivered virtually (Zoom) or physically, depending on students’ preferences, except for the OSCE session, which was always conducted physically. The teaching materials were prepared by the near-peer teachers beforehand and distributed to the students after each teaching session. The NPT programme coordinator supervised and provided necessary support to both near-peer teachers and near-peer students throughout the entire programme.

The near-peer teachers and near-peer students consented to participate in this study via written consent. A structured post-participation Likert 6-point scale “Peer Tutors Own Assessment” questionnaire with written consent, which was adopted from Liew et al. (2015), was sent to the near-peer teachers after this Near-Peer Teaching Programme via Google form to explore their perceived benefits in three components which are 1) Skills Enhancement, 2) Motivation and 3) Career Direction [Expectation]. This questionnaire (Appendix 1) contains 14 items, with responses scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.801, 0.714, and 0.814 for the domains of skills enhancement, motivation, and career direction.

Similarly, all the near-peer students who participated in this near-peer teaching programme were given the Peer Tutor Assessment questionnaire adopted from Liew et al. (2015), to fill in via Google form (Appendix 2). This questionnaire is to assess the acceptability of the teachings of the near-peer teachers. It contains 16 items that evaluate five domains: (1) Responsibility and Respect, (2) Information Processing, (3) Communication, (4) Critical Analysis, and (5) Self-Awareness. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate whether sex and student background affect self-perceived outcomes of near-peer teachers using independent T-test. Each participant was given 3 weeks to complete the questionnaire. Several reminders were sent via email throughout these 3 weeks to each participant to encourage them to fill in the questionnaire. Both near-peer teachers and near-peer students’ data were checked for normality. The asymmetry fell between -1 and +1 and assumed relatively symmetrical and mesokurtic.

III. RESULTS

A total of 51 medical students in their final year signed up as near-peer teachers. Of these, 28 near-peer teachers completed the questionnaire (response rate 54.9%), while 49 out of 100 near-peer students who joined this NPT programme responded in this study (response rate 49.0%). Among those near-peer teachers who responded, there were 9 (32.1%) males and 19 (67.9%) females. More local students responded in this study than international students (75% vs 25%). The overall mean age ± SD of the near-peer teachers is 23.75 ±1.21 years old. For the near-peer students, the overall mean age ± SD is 21.69 ± 0.74 years old. The number of international and local near-peer students who responded was similar. The data of the responses of both near-peer teachers and near-peer students that supports the findings of this study is openly available at Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26886517.v1 (Tang et al., 2024a) and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26886514.v1 (Tang et al., 2024b).

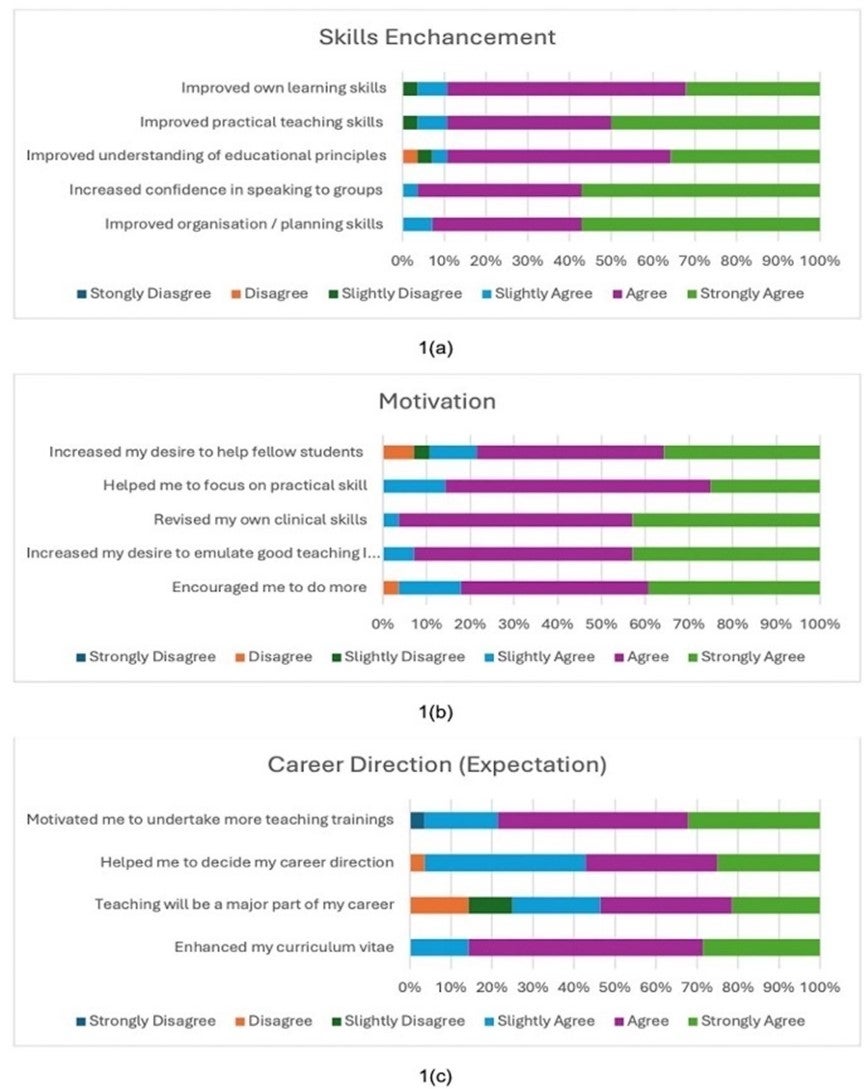

Table 1 showed peer review findings to ensure their voices were represented. To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, actions were taken to address credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and reflexitivity are outlined in Table 2. Figure 1 indicates the near-peer teachers view of the benefits of involving in the student-led near-peer teaching program.

|

Demographic |

Near-peer Teachers (n,%) |

Near-peer Students (n,%) |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

9 (32.1) |

27 (55.1) |

|

Female |

19 (67.9) |

22 (44.9) |

|

Age (Mean ± SD) |

23.75 ±1.21 |

21.69 ± 0.74 |

|

Student background |

||

|

Local |

21 (75) |

28 (57.1) |

|

International |

7 (25) |

21 (42.9) |

Table 1. Demographic data of the near-peer teachers

|

Skills Enhancement |

Mean score +/- SD |

|

Improved own learning skills |

5.21 ± 0.63 |

|

Improved practical teaching skills |

5.39 ± 0.69 |

|

Improved understanding of educational principles |

5.14 ± 0.93 |

|

Increased confidence in speaking to groups |

5.54 ± 0.58 |

|

Improved organisation/planning skills |

5.50 ± 0.64 |

|

Total Mean Score |

5.36 ± 0.53 |

|

Motivation |

|

|

Increased my desire to help fellow students |

4.96 ± 1.14 |

|

Helped me to focus on practical skills |

5.07 ± 0.60 |

|

Revised my own clinical skills |

5.36 ± 0.56 |

|

Increased my desire to emulate good teaching I have had |

5.32 ± 0.61 |

|

Encouraged me to do more |

5.11 ± 0.92 |

|

Total Mean Score |

5.16 ± 0.60 |

|

Career Direction (Expectation) |

|

|

Motivated me to undertake more teaching trainings |

4.96 ± 1.04 |

|

Helped me to decide on my career direction |

4.71 ± 0.94 |

|

Teaching will be a major part of my career |

4.36 ± 1.34 |

|

Enhanced my curriculum vitae |

5.14 ± 0.65 |

|

Total Mean Score |

4.79 ± 0.82 |

|

Total mean score for all domains |

5.11± 0.58 |

Table 2. The mean score (± SD) for the self-evaluation of near-peer teachers in relation to (1) skills enhancement, (2) motivation and (3) career direction (expectation)

Figure 1. Near-peer teachers view of the benefits of involving in the student-led NPT program: Analysis of post-participation questions responses (n=28) in Likert 6-point scale in relation to (a) skills enhancement, (b) motivation and (c) career direction (expectation)

Based on the responses to the questionnaire, the near-pear teachers widely agreed that the NPT programme positively impacted them (5.11 ± 0.58), with the highest score in the domain of skills enhancement (5.36 ± 0.53), followed by motivation (5.16 ± 0.60) and career direction (4.79 ± 0.82). Most of the near-peer teachers considered this programme improved their skills in terms of teaching, organising, communicating and understanding educational principles (Table 2). 100% of them agreed that this NPT programme increased their confidence in speaking to groups and enhanced their planning and organising skills. Furthermore, all 28 respondents (100%) reported being more motivated to revise their own clinical skills and focus more on their practical skills after teaching near-peer students to address the

knowledge gap. A significant proportion of near-peer teachers felt more encouraged to participate in more teaching programmes in the future (n=27, 96.43%) and more inclined to help fellow students next time (n=25, 89.28%). It is noteworthy that 96.43% of near-peer teachers agreeing that this NPT programme helped in deciding their career direction and motivated them to undertake more trainings. Besides, three quarters of them would consider teaching as their major career pathway in the future, with a mean score of 4.36 ± 1.34. Lastly, all 28 respondents (100%) agreed that joining the NPT programme had enhanced their curriculum vitae (100%).

Table 3 shows the mean score of near-peer students’ evaluation of near-peer teachers in five domains after joining the near-peer teaching programme.

|

Responsibility and Respect |

Mean Score +/- SD |

|

Completed all assigned tasks to the appropriate level |

5.27 ± 0.73 |

|

Completed all assigned tasks on time |

5.08 ± 0.67 |

|

Participated actively in the session |

5.14 ± 0.76 |

|

Showed behaviour and input that facilitated learning |

5.16 ± 0.66 |

|

Was punctual to the session |

5.08 ± 0.89 |

|

Listened and showed respect for the opinions of others |

5.16 ± 0.66 |

|

Total Mean Score |

5.15 ± 0.57 |

|

Information Processing |

|

|

Brought in new information to share with the group |

5.16 ± 0.71 |

|

Provided information that was relevant and helpful |

5.10 ± 0.77 |

|

Seemed to use a variety of resources to obtain the information |

5.10 ± 0.82 |

|

Total Mean Score |

5.12 ± 0.66 |

|

Communication |

|

|

Was able to communicate ideas clearly |

5.10 ± 0.68 |

|

Made comments and responses that were not confusing |

4.92 ± 0.84 |

|

Total Mean Score |

5.01 ± 0.65 |

|

Critical analysis |

|

|

Gave input that was focused and relevant to the case |

4.94 ± 0.75 |

|

Gave a summary of the session |

4.90 ± 0.82 |

|

Gave a summary of the session that showed evidence of reflection and evaluation |

4.94 ± 0.83 |

|

Total Mean Score |

4.93 ± 0.66 |

|

Self-awareness |

|

|

Appeared to be able to acknowledge his/her own strengths and weaknesses |

5.12 ± 0.73 |

|

Accepted and responded to criticism gracefully |

5.10 ± 0.74 |

|

Total Mean Score |

5.11 ± 0.62 |

|

Total mean score for all domains |

5.06 ± 0.51 |

Table 3. The mean score (± SD) for the near-peer students’ evaluation of near-peer teachers after the NPT programme in relation to (1) responsibility and respect, (2) information processing, (3) communication, (4) critical analysis and (5) self-awareness

When asked to evaluate the teaching of their near-peer teachers, the near-peer students considered the near-peer teachers demonstrating positive outcomes in all five domains (5.06 ± 0.51). The near-peer teachers were thought to have a high degree of professionalism in terms of responsibility and respect (5.15 ± 0.57) and self-awareness (5.11 ± 0.62). The most outstanding attribute demonstrated was the ability to complete assigned tasks appropriately (5.27 ± 0.73). Besides, the near-peer teachers performed satisfactorily to process information (5.12± 0.66), communicate (5.01± 0.65) and analyse critically (4.93 ± 0.66). However, the near-peer teachers were identified to score slightly lower in making non-confusing comments and responses (4.92 ± 0.84) as well as giving a summary of the session (4.90 ± 0.82).

|

Variables |

Independent T- test |

|

|

Mean difference (95% CI) |

P-value |

|

|

Sex (Male vs Female) |

||

|

Skills |

-0.101 (-0.549, 0.348) |

0.649 |

|

Motivation |

0.118 (-0.385, 0.621) |

0.634 |

|

Career Direction (Expectation) |

0.507 (-0.154, 1.169) |

0.127 |

|

Students’ background (Local vs International) |

||

|

Skills |

-0.210 (-0.688, 0.268) |

0.376 |

|

Motivation |

-0.276 (-0.810, 0.258) |

0.297 |

|

Career Direction (Expectation) |

0.280 (-0.439, 1.034) |

0.414 |

Table 4. Comparison of self-perceived outcomes of near-peer teachers between male and female, local and international students (Independent t-test)

The independent t-test were performed to find out the association between sex and perceived outcomes of the near-peer teachers. Our study revealed that it is statistically insignificant between male and female in the perceived benefits for skills (P = 0.649), motivation (P = 0.549) and career direction (P = 0.127).

Besides, there is no correlation between students’ background and the three measured outcomes. There is statistically insignificant between local and international students in term of skills (P = 0.376), motivation (P = 0.397) and career direction (P = 0.414).

IV. DISCUSSION

This study provides valuable insights into the background and characteristics of the final-year medical students who voluntarily participated in a student-led, student-run NPT programme. The outcomes of their participation concerning their perceived benefits in terms of skills, motivation, and expectations were investigated. Overall, the near-peer teachers reported that this NPT programme helped them tremendously to improve their skills in terms of learning and teaching, which might be driven by their primary motive for joining this programme. This finding was similar to previous studies, which showed skills enhancement in volunteer near-peer teachers (Buckley & Zamora, 2007; Liew et al., 2015). Our study further reaffirms the plausibility of a student-run NPT programme to enhance teaching and learning skills. However, due to the voluntary nature of participation in this near-peer teaching programme, the students who are likely most in need of skill enhancement may have been omitted from this programme, and they might be less equipped to teach after they graduate. Some studies recommended more incentives to be given to such students to encourage them to make use of the opportunities offered (Buckley & Zamora, 2007).

The motivation evaluated includes both self-actualising inner motivations to improve their clinical and practical skills and the external, tangible desire to help fellow students. The high motivation score suggests the reinforcement of a desirable attitude towards future educational and teaching responsibilities, which matches the GMC’s emphasis on the teaching role of doctors (General Medical Council, 2015). A couple of reasons may explain this: firstly, the near-peer teachers are final-year medical students, who will sit for their final examinations very soon and are desperately finding ways to improve their learning. The process of teaching, which requires extensive preparation, a comprehensive understanding of the content, dynamic synthesis, and anticipation of the questions that may be asked of them, forms an efficient learning strategy. Secondly, the near-peer teachers, inspired by the excellent teaching they once had, wish to impart good teaching to the near-peer students going through the same journey.

Although many near-peer teachers are more motivated to be involved in more teaching and even take up teaching training courses in the future, the influence is not apparent in the long-term career direction. This could be explained well by the brief intervention of this NPT programme that lasted 3 months. However, the lucrative income opportunities in other medical specialities and the limited exposure to medical education pathways in undergraduate medical schools are some factors that may sway them away from considering medical education as their primary career pathway (Puri et al., 2021; Sarikhani et al., 2021). Therefore, more effort should be directed to increase teaching opportunities and to raise awareness of medical education career options in the undergraduate medical school programme. This includes developing Student Selected Components focusing on medical education and giving opportunities to shadow clinical teaching staff (Liew et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2008).

After participating in this study, the near-peer students evaluated the near-peer teachers highly in all the domains. This provides a strong indication of the recognition and acceptance of the teaching skills of the near-peer teachers. In addition, the ability of the near-peer teachers to demonstrate responsibility and respect throughout this programme shows their preparedness to work under the GMC with desirable attitudes and professionalism. Previous studies have also shown that near-peer teachers gain more subjectively and objectively than students (Liew et al., 2015; Ten Cate & Durning, 2007). This can be related to the underpinning of the psychological and social theories behind the dynamics between near-peer teachers and near-peer students (Loda et al., 2019). The theoretical model of cognitive and social congruence explains the positive evaluation of the near-peer teachers (Loda et al., 2019; Rollmann et al., 2023). The proximity of age between the near-peer teachers and the near-peer students enables them to share similar knowledge frameworks, language and social roles. Besides, near-peer teachers are perceived to be more approachable and understanding of the needs and struggles of the near-peer students. This may be because the near-peer teachers have had similar experiences themselves. Therefore, near-peer teachers are better able to process difficult concepts and frameworks, emphasize the key points, and communicate the information using familiar and non-confusing language to ensure that near-peer students comprehend better (Loda et al., 2019; Loda et al., 2020). The perceived barrier to providing feedback to near-peer teachers is also lower compared to faculty-led staff, as the age difference between them is much smaller. This might suggest why near-peer teachers feel less offended by criticism and are more likely to accept and respond to criticism gracefully (Loda et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the near-peer students thought that some near-peer teachers experienced some difficulties in giving relevant input and summary of the sessions, thus necessitating more structured pedagogical training for near-peer teachers in this aspect. Mastering these teaching skills would allow the near-peer students to appreciate better the big picture and key takeaway points of each lesson (Khaw & Raw, 2016).

One of the focuses of this study is to analyse the sex-specific difference of the perceived outcomes of the near-peer teachers. Although there is an appropriate twice female near-peer teachers who responded to this study compared to male near-peer teachers, the results shows that the sex-specific difference in the perceived improvement in motivation, skills and career direction is not significant. There is no sex-specific difference in term of enthusiasm and motivation to involve in near-peer teaching (Messerer et al., 2021). Throughout the whole process, they receive similar gender-equitable support and guidance without any discrimination.

V. LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As few studies have reported outcomes for a purely student-led student-run NPT programme, this study offers valuable insights concerning the perceived benefits for near-peer teachers. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, given the relatively small sample size of the near-peer teachers and the subjective nature of the self-reported questionnaire, the results may benefit from further objective testing, such as correlation with examination results. Secondly, this study is only carried out in a single medical school, with a slight variation in the implementation of the NPT compared to other institutions. Verification of these results across various medical schools would strengthen these findings. This study thus calls for more structured student-led peer teaching programmes to be implemented in more medical schools and to be assessed longitudinally to evaluate the association between the student-led peer teaching programme and the outcomes of participation of the near-peer teachers. It may also be worthwhile to investigate and assess the perspective of near-pear teachers who demonstrated interest in medical education, as well as to evaluate the long-term outcomes in career direction for medical graduates who once participated in near-peer teaching programmes.

VI. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this purely student-led, student-run near-peer teaching programme likely improved the final-year medical students in fulfilling the “Doctors as Teachers” responsibilities outlined by the GMC. Besides, the near-peer teachers also reported having positive outcomes in their skills and career direction. Likewise, from the perspective of the near-peer students, the near-peer teachers demonstrated outstanding skills and professionalism in all five domains: responsibility and respect, information processing, communication, critical analysis and self-awareness. Possessing the skills and professionalism fulfils the expectations of GMC for healthcare professionals to provide the right care at the right time with the right skills for the good of patients.

Notes on Contributors

Kevin Xuan Hong Tang was a final year medical student who conceptualised and designed the study, reviwed the literature, conducted the data collection and analysis, prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript.

Koon Kee Teo was a final year medical student who reviewed the literature, collected and analysed the data, prepared the figures and helped in writing the manuscript.

Kye Mon Min Swe is an Associate Professor in Education Research in NUMed. She participated in conceptualising the study, performed statistical analysis and drafted, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manusript.

Ethical Approval

This study titled “Embracing Doctors as Teachers: Evaluating the Student-led Near-Peer Teaching at Transnational Campus” was approved by the Research Management Committee and the Newcastle University Ethics Committee (Approval number 45070/2023).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare repository, as below,

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26886517.v1 (Tang et al., 2024a) and

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26886514.v1 (Tang et al., 2024b).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the NUMed Medical Education Society for carrying out this programme. The authors are grateful for Professor Vishna Devi Nadarajah for her support and feedback in this research.

Funding

The authors declare that there is no funding received in this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Botelho, M. G., Boubaker, B., & Wong, I. B. (2022). Near‐peer teaching for learning clinical photography skills: Perceptions of students. European Journal of Dental Education, 27(3), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12831

Buckley, S., & Zamora, J. (2007). Effects of participation in a cross year peer tutoring programme in clinical examination skills on volunteer tutors’ skills and attitudes towards teachers and teaching. BMC Medical Education, 7(1), Article 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-20

Burgess, A., McGregor, D., & Mellis, C. (2014). Medical students as peer tutors: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), Article 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-115

Busari, J. O., Prince, K. J., Scherpbier, A. J., Van Der Vleuten, C. P., & Essed, G. G. (2002). How residents perceive their teaching role in the clinical setting: A qualitative study. Medical Teacher, 24(1), 57-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00034980120103496

Cook, V., Fuller, J. H., & Evans, D. E. (2010). Helping students become the medical teachers of the future – The Doctors as Teachers and Educators (DATE) programme of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London. Education for Health, 23(2), 415. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.101487

De Menezes, S., & Premnath, D. (2016). Near-peer education: A novel teaching program. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, 160–167. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5738.3c28

Frearson, S., & Gale, S. (2017). Educational opportunities on a ward round; utilising near-peer teaching. Future Healthcare Journal, 4(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.4-1-19

Furmedge, D. S., Iwata, K., & Gill, D. (2014). Peer-assisted learning – Beyond teaching: How can medical students contribute to the undergraduate curriculum? Medical Teacher, 36(9), 812–817. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2014.917158

General Medical Council. (2011, February). Developing teachers and trainers in undergraduate medical education. Retrieved June 2, 2024, from https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/developing-teachers-and-trainers-in-undergraduate-medical-education—guidance-0815_pdf-56440721.pdf

General Medical Council. (2015, July). Outcomes for graduate (Tomorrow’s doctors). Retrieved June 2, 2024, from https://www.gmcuk.org//media/documents/Outcomes_for_graduates_ Jul_15_1216.pdf_61408029.pdf

General Medical Council. (2023, August 22). Good medical practice. Retrieved June 2, 2024, from https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice-2024—english-102607294.pdf

Hardie, P., O’Donovan, R., Jarvis, S., & Redmond, C. (2022). Key tips to providing a psychologically safe learning environment in the clinical setting. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), Article 816. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03892-9

Hettle, D., & Morgan, J. (2019 December 2-3). “Teaching and Training for the future”: Final-year students’ perspectives on their role as near-peer teachers” [Conference presentation abstract]. Developing Excellence in Medical Education, Manchester. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344439487_Teaching_and_Training_for_the_future_Finalyear_students’_perspectives_on_their_role_as_near-peer_teachers

Khaw, C., & Raw, L. (2016). The outcomes and acceptability of near-peer teaching among medical students in clinical skills. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, 189–195. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5749.7b8b

Knobloch, A. C., Ledford, C. J., Wilkes, S., & Saperstein, A. K. (2018). The impact of near-peer teaching on medical students’ transition to clerkships. Family Medicine, 50(1), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.22454/fammed.2018.745428

Liew, S., Sow, C., Sidhu, J., & Nadarajah, V. D. (2015). The near-peer tutoring programme: embracing the ‘doctors-to-teach’ philosophy – A comparison of the effects of participation between the senior and junior near-peer tutors. Medical Education Online, 20(1), 27959. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v20.27959

Loda, T., Erschens, R., Loenneker, H., Keifenheim, K. E., Nikendei, C., Junne, F., Zipfel, S., & Herrmann-Werner, A. (2019). Cognitive and social congruence in peer-assisted learning – A scoping review. PloS One, 14(9), e0222224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222224

Loda, T., Erschens, R., Nikendei, C., Giel, K., Junne, F., Zipfel, S., & Herrmann-Werner, A. (2020). A novel instrument of cognitive and social congruence within peer-assisted learning in medical training: construction of a questionnaire by factor analyses. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), Article 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02129-x

Messerer, D. A. C., Kraft, S. F., Horneffer, A., Messerer, L. A. S., Böckers, T. M., & Böckers, A. (2021). What factors motivate male and female Generation Z students to become engaged as peer teachers? A mixed‐method study among medical and dental students in the gross anatomy course. Anatomical Sciences Education, 15(4), 650–662. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2114

Pierce, H., Kermack, A., & Foley, V. (2024). What training do foundation doctors feel they require to develop as clinical teachers? Journal of Education and Training Studies, 12(2), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v12i2.6714

Puri, P., Landman, N., Smoldt, R. K., & Cortese, D. (2021). Quantifying the financial value of clinical specialty choice and its association with competitiveness of admissions. Curēus, 13(2), e13272. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.13272

Qureshi, Z., Gibson, K., Ross, M., & Maxwell, S. (2013). Perceived tutor benefits of teaching near peers: Insights from two near peer teaching programmes in South East Scotland. Scottish Medical Journal, 58(3), 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0036933013496935

Rollmann, I., Lauter, J., Kuner, C., Herrmann-Werner, A., Bugaj, T. J., Friederich, H., & Nikendei, C. (2023). Tutors ́ and students’ agreement on social and cognitive congruence in a Sonography peer-assisted-learning scenario. Medical Science Educator, 33(4), 903–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01814-y

Ross, M. T., & Cameron, H. S. (2007). Peer assisted learning: A planning and implementation framework: AMEE Guide no. 30. Medical Teacher, 29(6), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701665886

Sarikhani, Y., Ghahramani, S., Bayati, M., Lotfi, F., & Bastani, P. (2021). A thematic network for factors affecting the choice of specialty education by medical students: A scoping study in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), Article 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02539-5

Tang, K. X. H., Teo, K. K., & Swe, K. M. M. (2024a). The evaluation of near-peer teachers in five domains completed by near-peer students after joining peer teaching program (Version 1) [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26886517.v1

Tang, K. X. H., Teo, K. K., & Swe, K. M. M. (2024b). Near-peer teachers self-evaluation data after joining peer teaching program (Version 1) [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.fig share.26886514.v1

Ten Cate, O., & Durning, S. (2007). Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Medical Teacher, 29(6), 546–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701583816

Wilson, S., Denison, A. R., & McKenzie, H. (2008). A survey of clinical teaching fellowships in UK medical schools. Medical Education, 42(2), 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02933.x

Yu, T. C., Wilson, N. C., Singh, P. P., Lemanu, D. P., Hawken, S. J., & Hill, A. G. (2011). Medical students-as-teachers: A systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 2, 157–172. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s14383

Zheng, B., & Wang, Z. (2022). Near-peer teaching in problem-based learning: Perspectives from tutors and tutees. PloS One, 17(12), e0278256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278256

*Kye Mon Min Swe

1, Jalan Sarjana 1, Educity,

79200 Iskandar Puteri, Johor, Malaysia

Email: kye-mon.min-swe@newcastle.edu.my

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.