Assessment of medical professionalism using the Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX): A survey of faculty perception of relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness

Submitted: 17 April 2020

Accepted: 05 August 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 114-118

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/SC2358

Warren Fong1,3,4, Yu Heng Kwan2, Sungwon Yoon2, Jie Kie Phang1, Julian Thumboo1,2,4 & Swee Cheng Ng1

1Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 2Programme in Health Services and Systems Research, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 3Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 4Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to examine the perception of faculty on the relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the Professionalism Mini Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX) in the assessment of medical professionalism in residency programmes in an Asian postgraduate training centre.

Methods: Cross-sectional survey data was collected from faculty in 33 residency programmes. Items were deemed to be relevant to assessment of medical professionalism when at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8 on a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant). Feedback regarding the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX assessment was also collected from the faculty through open-ended questions.

Results: In total, 555 faculty from 33 residency programmes participated in the survey. Of the 21 items in the P-MEX, 17 items were deemed to be relevant. For the remaining four items ‘maintained appropriate appearance’, ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’, ‘solicited feedback’, and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’, the percentage of faculty who gave a rating of ≥8 was 78%, 75%, 74%, and 69% respectively. Of the 333 respondents to the open-ended question on feasibility, 34% (n=113) felt that there were too many questions in the P-MEX. Faculty also reported that assessments about ‘collegiality’ and ‘communication with empathy’ were missing in the current P-MEX.

Conclusion: The P-MEX is relevant and feasible for assessment of medical professionalism. There may be a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality and empathetic communication in the P-MEX.

Keywords: Professionalism, Singapore, Survey, Assessment

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical professionalism is one of the core Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies and forms the basis of medicine’s contract with society. Unprofessional behaviour during training of junior doctors has been shown to result in future unprofessional behaviour. Assessment of professionalism not only allows for timely feedback to residents to help them improve, but also allows for development of better curriculum to prevent lapses in medical professionalism. The Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX) had previously been identified as a potential observer-based assessment tool (Kwan et al., 2018), but it has not been validated in a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural Asian context such as Singapore. According to International Ottawa Conference Working Group on the Assessment of Professionalism, professionalism varies across cultural contexts, and therefore cross-cultural validation of the assessment tool for medical professionalism is imperative (Hodges et al., 2011). The current assessment tools adopted in local institutions may not cover the entire continuum of medical professionalism. For example, in the Ministry of Health Holdings (MOHH) C1 form which is currently being used for the assessment of residents on a 6-monthly basis, the assessment of professionalism is summative and consists of only three items (1) Accepts responsibility and follows through on tasks, (2) Responds to patient’s unique characteristics and needs equitably, (3) Demonstrates integrity and ethical behaviour.

We aimed to (1) examine faculty perception of the relevance of the P-MEX for assessment of medical professionalism in the local context, and (2) determine the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX as an assessment tool for medical professionalism in Singapore.

II. METHODS

A. Design and Participants

We invited faculty in the SingHealth residency programmes to participate in the study by completing an online anonymous questionnaire in July 2018 to August 2018. Participants were given one week to complete the survey, with three reminder emails sent at one-week, two-weeks and one-month after the deadline for submission. SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study (Reference Number: 2016/3009). Implied informed consent was provided by participants before completing the online anonymous questionnaire.

B. Survey Questionnaire

The P-MEX consists of four domains (Doctor-patient relationship skills, Reflective skills, Time management and Inter-professional relationship skills) and 21 sub-domains. Faculty were asked to rate the relevance of each item in P-MEX using a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant). The faculty were also asked the following open-ended questions to determine the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX- (1) “In your opinion, is a P-MEX form with 21 items too long, making it not feasible for routine use? If so, which items should be removed?” and (2) “In your opinion, are there any missing items (observable actions of a medical professional) that should be included in this form? If so, what new items should be added?” The questionnaire also included additional questions related to demographic characteristics (age, gender, specialty and number of years since becoming a specialist).

C. Analysis

Items were deemed to be relevant to the assessment of medical professionalism when at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8. This was determined by expert judgement and prior literature (Avouac et al., 2011). For the open-ended questions on feasibility and comprehensiveness, responses were categorised and the number of the respondents who deemed the 21-item P-MEX to be not feasible (too long) or not comprehensive (there were missing items that should be included) are presented.

III. RESULTS

In total, 555 faculty from 33 residency programmes participated in the survey (response rate 44%). The respondents were 59% male, median age 43 years old, age ranged from 30 to 78 years old. Specialists from medical and surgical disciplines made up 39% and 27% of the respondents respectively, with the remaining respondents coming from diagnostic radiology/nuclear medicine, anaesthesiology, paediatrics and emergency medicine (12%, 11%, 6% and 5% of the respondents respectively).

A. Relevance

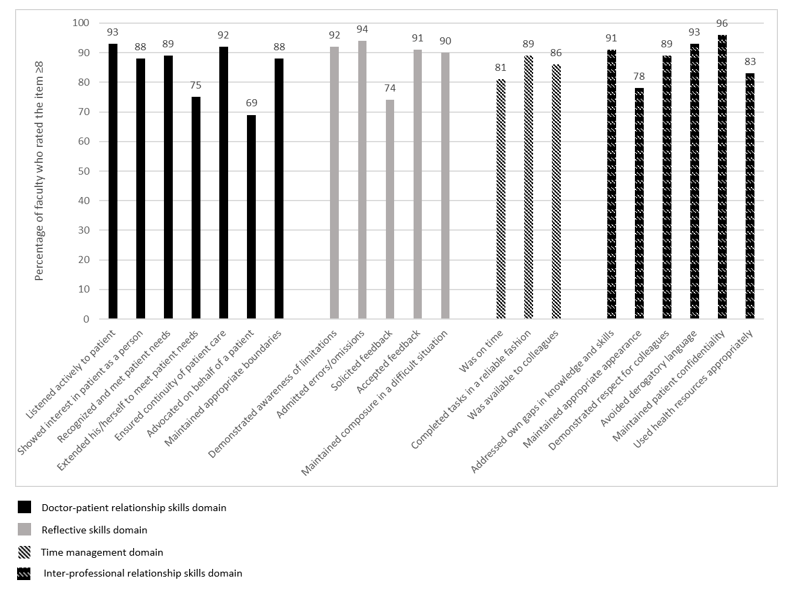

Of the 21 items in P-MEX, 17 items were deemed to be relevant (at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8). For the remaining four items ‘maintained appropriate appearance’, ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’, ‘solicited feedback’, and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’, the percentage of faculty who gave a rating of ≥8 was 78%, 75%, 74%, and 69% respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of faculty (n=555) who rated the item ≥8 on the relevance of the item in assessment of medical professionalism using a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant).

B. Feasibility

There were 333 respondents for the question “In your opinion, is a P-MEX form with 21 items too long, making it not feasible for routine use? If so, which items should be removed?”, of which 34% (n=113) felt that there were too many questions in the P-MEX assessment form. The top four items chosen to be removed were “solicited feedback” (n=36), “extended his/herself to meet patient needs” (n=27), “advocated on behalf of a patient” (n=25), and “maintained appropriate appearance” (n=23). 208 (62%) respondents felt that the number of questions in the P-MEX assessment form was appropriate.

C. Comprehensiveness

There were 307 respondents to the question “In your opinion, are there any missing items (observable actions of a medical professional) that should be included in this form? If so, what new items should be added?”, of which 28% (n=85) faculty felt that there were missing items. The most frequently mentioned missing items were regarding assessment of ‘collegiality’ (n=54) and assessment of ‘communication with empathy’ (n=12).

Examples of ‘collegiality’ provided by faculty— “Collaboration with other healthcare professionals in the patients’ best interest”, “Demonstration of collaborative behaviour”

Examples of ‘communication with empathy ‘provided by faculty— “Communicate with empathy and effectively to patient and family, taking into account their level of understanding, education and socioeconomic background”, “Communication skills…should embrace empathy, listening skills, discretion, sensitivity and intelligence… sufficient information, counselling, planning and advice regarding medical condition and options.”

207 respondents (67%) felt that the P-MEX was comprehensive for the assessment of medical professionalism.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study provides preliminary evidence on the relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX in the assessment of medical professionalism in an Asian city state. The current study is part of a larger project to culturally adapt and validate the P-MEX. Based on our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the faculty perception on relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX in the assessment of medical professionalism in a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic context.

There were four items that were deemed to be less relevant (extended his/herself to meet patient needs, advocated on behalf of a patient, solicited feedback, maintained appropriate appearance). These findings were also similar in a validation study performed in Canada, where the items ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’ and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’ were also frequently marked as ‘not applicable’, suggesting that the two items may be less relevant (Cruess, McIlroy, Cruess, Ginsburg, & Steinert, 2006). Qualitative methods can be used to explore the reasons why these items were deemed to be less relevant. About one-third of faculty felt that P-MEX was too long. Further study is warranted to evaluate the possibilities for shortening the P-MEX to reduce response burden and enhance routine use of the P-MEX.

In addition, our study revealed a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality. Some faculty felt that ‘collegiality’ was missing in the P-MEX despite the presence of items such as ‘demonstrated respect for colleagues’ and ‘avoided derogatory language’. This suggests that collegiality may encompass actions other than demonstrating respect and avoiding derogatory language in the local context, and further reinforces the emphasis of interprofessional collaborative practice.

Faculty also felt that there was also a lack of assessment of ‘communication with empathy’ in the P-MEX. The importance of empathetic communication is also supported by a study in Indonesia, a country in the same region, which found that patients considered communication as the most important attribute of medical professionalism (Sari, Prabandari, & Claramita, 2016).

This study has some limitations. The non-response rate raises concern about possible selection bias. Non-responders may have been less enthusiastic about the assessment of medical professionalism. Medical professionalism is affected by socio-cultural factors, therefore the findings from this study may not be entirely generalizable to another socio-cultural context. In addition, we were unable to elucidate the reasons for disagreement with the relevance of some of the items in the P-MEX as many faculty did not provide feedback and comments. Nevertheless, the findings of this study can serve as basis for future research, especially in countries with similar multicultural backgrounds.

V. CONCLUSION

Faculty agreed that most of the items in the P-MEX were relevant in the assessment of medical professionalism. Majority of the faculty also felt that the P-MEX was feasible to be used routinely in the assessment in medical professionalism. There may be a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality and communication with empathy in the modified P-MEX.

Notes on Contributors

Warren Fong reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Yu Heng Kwan reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Sungwon Yoon advised the design of study, analysed data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. Jie Kie Phang collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Julian Thumboo advised the design of study, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. Swee Cheng Ng advised the design of study, collected data, analysed data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this was granted by the SingHealth Institutional Review Board (Reference Number: 2016/3009).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank all the study participants for contributing to this work.

Funding

This research was supported by SingHealth Duke-NUS Medicine Academic Clinical Programme Education Support Programme Grant (Reference Number: 03/FY2017/P2/03-A47). Funder was not involved in the design, delivery or submission of the research.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Avouac, J., Fransen, J., Walker, U., Riccieri, V., Smith, V., Muller, C., … Matucci-Cerinic, M. (2011). Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: Results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 70(3), 476-481. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.136929

Cruess, R., McIlroy, J. H., Cruess, S., Ginsburg, S., & Steinert, Y. (2006). The professionalism mini-evaluation exercise: A preliminary investigation. Academic Medicine, 81(10), S74-S78.

Hodges, B. D., Ginsburg, S., Cruess, R., Cruess, S., Delport, R., Hafferty, F., . . . Ohbu, S. (2011). Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Medical Teacher, 33(5), 354-363.

Kwan, Y. H., Png, K., Phang, J. K., Leung, Y. Y., Goh, H., Seah, Y., . . . Lie, D. (2018). A systematic review of the quality and utility of observer-based instruments for assessing medical professionalism. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10(6), 629-638.

Sari, M. I., Prabandari, Y. S., & Claramita, M. (2016). Physicians’ professionalism at primary care facilities from patients’ perspective: The importance of doctors’ communication skills. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(1), 56-60. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.184624

*Warren Fong

SingHealth Rheumatology,

Senior Residency Programme,

20 College Road,

Singapore 169856

Tel: +6563214028

Email: warren.fong.w.s@singhealth.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.