A systematic scoping review of teaching and evaluating communications in the intensive care unit

Submitted: 4 May 2020

Accepted: 3 August 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 3-29

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/RA2351

Elisha Wan Ying Chia1,2, Huixin Huang1,2, Sherill Goh1,2, Marlyn Tracy Peries1,2, Charlotte Cheuk Yiu Lee2,3, Lorraine Hui En Tan1,2, Michelle Shi Qing Khoo1,2, Kuang Teck Tay1,2, Yun Ting Ong1,2, Wei Qiang Lim1,2, Xiu Hui Tan1,2, Yao Hao Teo1,2, Cheryl Shumin Kow1,2, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin4, Min Chiam5, Jamie Xuelian Zhou2,6,7 & Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna1,2,5,7-10

1Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Division of Supportive and Palliative Care, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore; 3Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 4Medical Library, National University of Singapore Libraries, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 5Division of Cancer Education, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore; 6Lien Centre of Palliative Care, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School, Singapore; 7Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School, Singapore; 8Centre for Biomedical Ethics, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 9Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, Academic Palliative & End of Life Care Centre, University of Liverpool; 10PalC, The Palliative Care Centre for Excellence in Research and Education, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Whilst the importance of effective communications in facilitating good clinical decision-making and ensuring effective patient and family-centred outcomes in Intensive Care Units (ICU)s has been underscored amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, training and assessment of communication skills for healthcare professionals (HCPs) in ICUs remain unstructured

Methods: To enhance the transparency and reproducibility, Krishna’s Systematic Evidenced Based Approach (SEBA) guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR), is employed to scrutinise what is known about teaching and evaluating communication training programmes for HCPs in the ICU setting. SEBA sees use of a structured search strategy involving eight bibliographic databases, the employ of a team of researchers to tabulate and summarise the included articles and two other teams to carry out content and thematic analysis the included articles and comparison of these independent findings and construction of a framework for the discussion that is overseen by the independent expert team.

Results: 9532 abstracts were identified, 239 articles were reviewed, and 63 articles were included and analysed. Four similar themes and categories were identified. These were strategies employed to teach communication, factors affecting communication training, strategies employed to evaluate communication and outcomes of communication training.

Conclusion: This SEBA guided SSR suggests that ICU communications training must involve a structured, multimodal approach to training. This must be accompanied by robust methods of assessment and personalised timely feedback and support for the trainees. Such an approach will equip HCPs with greater confidence and prepare them for a variety of settings, including that of the evolving COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Communication, Intensive Care Unit, Assessment, Skills Training, Evaluation, COVID-19, Medical Education

Practice Highlights

- The global COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of effective communications in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

- ICU communications training should adopt a longitudinal, structured and multimodal approach.

- Robust stepwise evaluation of learner outcomes via Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy is needed.

- Supportive host organisation and conducive learning environment and are key to successful curricula.

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed immense strain on intensive care units (ICU)s with healthcare teams and resources stretched to meet the sudden increased healthcare demands of critically ill patients. To further complicate the situation, ICU teams are called to not only communicate closely with colleagues in a bid to support them but also counsel families confronting acute distress and uneasy waits separated from their loved ones due to restrictions to visiting in an effort to limit the spread of this pandemic (Ministry of Health, 2020; World Health, 2020). From breaking bad news (Blackhall, Erickson, Brashers, Owen, & Thomas, 2014; J. Yuen & Carrington Reid, 2011), to conveying the need for sedation and intubation (Carrillo Izquierdo, Diaz Agea, Jimenez Rodriguez , Leal Costa, & Sanchez Exposito, 2018) and providing progress reports on critically ill patients (Curtis et al., 2005; Curtis, White, Curtis, & White, 2008; Yang et al., 2020), communication skills amongst ICU healthcare professionals (HCPs) are pivotal in reassuring anxious, emotional and stressed patients and families (Ahrens, Yancey, & Kollef, 2003; Foa et al., 2016; Kirchhoff et al., 2002). Good communication in the ICU has also been shown to improve patient-physician relationships (K. G. Anderson & Milic, 2017), patient and family-centred outcomes, quality of care, and patient and family satisfaction (Bloomer, Endacott, Ranse, & Coombs, 2017; Cao et al., 2018; Currey, Oldland, Considine, Glanville, & Story, 2015). Effective communications between HCPs in ICU also enhances clinical decision-making (Kleinpell, 2014), reduces medication and treatment errors (Clark, Squire, Heyme, Mickle, & Petrie, 2009; Happ et al., 2014; Sandahl et al., 2013), decreases physician burnout (Rachwal et al., 2018), and improves staff retention and satisfaction (Hope et al., 2015).

With evidence suggesting that poor communication skills (Downar, Knickle, Granton, & Hawryluck, 2012; Foa et al., 2016) and training (Smith, O’Sullivan, Lo, & Chen, 2013) are likely to increase patients’ (Dithole, Sibanda, Moleki, & Thupayagale ‐ Tshweneagae, 2016) and families’ (Curtis et al., 2008) stress, adversely affect care and recovery (Dithole et al., 2016), and increase healthcare costs (Kalocsai et al., 2018), some authors have suggested that effective communication skills are at least as important (Adams, Mannix, & Harrington, 2017; Cicekci et al., 2017; Van Mol, Boeter, Verharen, & Nijkamp, 2014) to good patient care as clinical acumen (Curtis et al., 2001a). Yet despite evidence of the importance of communication skills in ICU, communication skills training remains inconsistent, variable and not evidence-based in most ICU settings (Adams et al., 2017; Berlacher, Arnold, Reitschuler-Cross, Teuteberg, & Teuteberg, 2017; Bloomer et al., 2017; D. A. Boyle et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2018; Sanchez Exposito et al., 2018).

With this in mind, a systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to map current approaches to communications skills training in ICUs (Munn et al., 2018) and potentially guide design of a communications training programme. An SSR allows for systematic extraction and synthesis of actionable and applicable information whilst summarising available literature across a wide range of pedagogies and practice settings employed to understand what is known about teaching and evaluating communication training programmes for HCPs in the ICU setting (Munn et al., 2018).

II. METHODS

To overcome concerns about the transparency and reproducibility of SSR, a novel approach called Krishna’s Systematic Evidenced Based Approach (henceforth SEBA) is proposed (Kow et al., 2020; Krishna et al., 2020; Ngiam et al., 2020). This SEBA guided SSR (henceforth SSRs in SEBA) adopts a constructivist perspective to map this complex topic from multiple angles (Popay et al., 2006) whilst a relativist lens helps account for variability in communication skills training (Crotty, 1998; Ford, Downey, Engelberg, Back, & Curtis, 2012; Pring, 2000; Schick-Makaroff, MacDonald, Plummer, Burgess, & Neander, 2016).

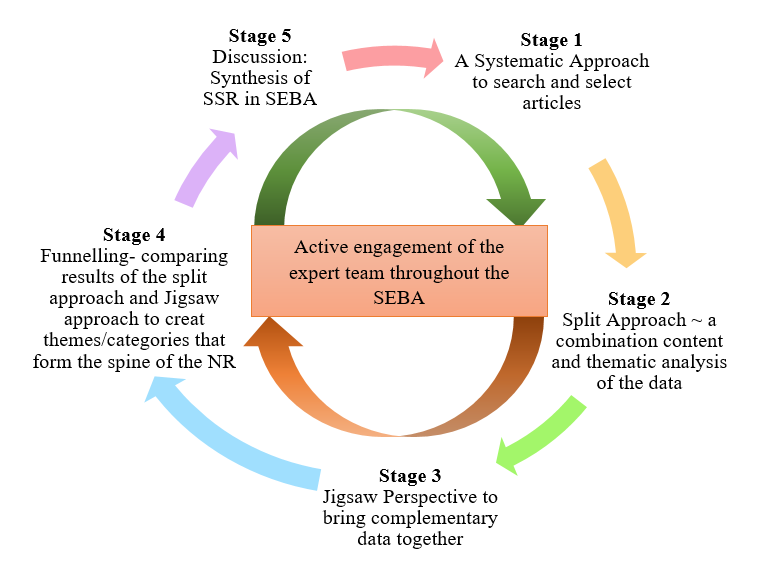

To provide a balanced review, the research team was supported by the medical librarians from the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM), the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) and local educational experts and clinicians at the NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School (henceforth the expert team). The research and expert teams adopted an interpretivist approach as they proceeded through the five stages of SEBA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The SEBA Process

A. Stage 1: Systematic Approach

1) Determining the title and research question: The research and expert teams agreed upon the goals, population, context and concept to be evaluated in this SSR. The two teams then agreed that the primary research question should be “What is known about teaching and evaluating communication training programs for HCPs in the ICU setting?” The secondary research questions were “How are communication skills taught and assessed in the ICU setting?” and “How effective have such interventions been as described in the published literature?”

2) Inclusion criteria: A Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS) format was adopted to guide the research process (Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, et al., 2015a; Peters, Godfrey, McInerney, et al., 2015b) (Table 1).

|

PICOS |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Population |

· Undergraduate and postgraduate healthcare providers (e.g. doctors, medical students, nurses, social workers) within ICU setting · ICU settings including medical, surgical, cardiology and neurology ICU · Communication between healthcare providers and patients in the ICU, or between healthcare providers in the ICU and patients’ families · Communication between or within healthcare providers’ teams in the ICU |

· Articles focusing solely on neonatal/ paediatric ICU setting · Articles focusing solely on speech therapy/ physical therapy/ occupational therapy · Non-ICU settings (e.g. general wards, emergency department) · Non-medical professions (e.g. Science, Veterinary, Dentistry) · Communication carried out over technological platforms |

|

Intervention |

· Need for/ importance of interventions to teach communication in ICU setting · Facilitators and barriers to teaching communication in ICU setting · Recommendations, interventions, methods (e.g. tools, simulations, videos), curriculum content and assessments used for teaching communication in ICU setting |

|

|

Comparison |

· Comparisons of various interventions, methods, curricula and evaluation methods used to teach or assess communication in ICU setting and its impact upon patients, healthcare providers, healthcare, and society |

|

|

Outcome |

· Impact of interventions on patients, healthcare providers, healthcare, and society · Evaluation methods to assess interventions, methods, or curriculum used to teach communication |

|

|

Study design |

· Articles in English or translated to English · All study designs including: o Mixed methods research, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, and descriptive papers o Case reports and series, ideas, editorials, and perspectives · Publication dates: 1st January 2000 – 31st December 2019 · Databases: PubMed, ERIC, JSTOR, Embase, CinaHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, Google Scholar |

|

Table 1. PICOS

Nine members of the research team carried out independent searches for articles published between 1st January 2000 – 31st December 2019 in eight bibliographic databases (PubMed, ERIC, JSTOR, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, Psycinfo and Google Scholar). The searches were carried out between 27th January 2020 and 14th February 2020. The PubMed search strategy can be found in Supplementary Material A. An independent hand search was done to identify key articles.

3) Extracting and charting: Nine members of the research team independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified and created individual lists of titles to be included which were discussed online. Consensus was achieved on the final list of articles to be included using (Sambunjak, Straus, & Marusic, 2010)’s “negotiated consensual validation” approach through collaborative discussion and negotiation on points of disagreement on online meetings.

B. Stage 2. Split Approach

Working in three independent groups, the reviewers analysed the included articles using the ‘split approach’ (Ng et al., 2020). In one group, four researchers independently reviewed and summarised all the included articles in keeping with according recommendations set out by Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, and Pawson (2013)’s “RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews” and Popay et al. (2006)’s “Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews”. The four research team members then discussed their individual findings at online meetings and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the tabulated summaries (Sambunjak et al., 2010). The tabulated summaries served to highlight key points from the included articles.

The four members of the research team also employed the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) (Reed et al., 2008) and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007) also evaluated the quality of qualitative and quantitative studies included in this review.

Concurrently, the second group of five researchers analysed all the included articles using (Braun & Clarke, 2006)’s approach to thematic analysis then discussed their individual findings at online meetings and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final themes (Sambunjak et al., 2010). The third group of four researchers employed Hsieh and Shannon (2005)’s approach to directed content analysis to independently analyse all the included articles, discussed their independent findings online and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final themes (Sambunjak et al., 2010). This split approach consisting of the tabulated summaries and concurrent thematic analysis and content analysis enhances the reliability of the analyses. The tabulated summaries also help ensure that important themes are not lost.

1) Thematic analysis: Phase 1 of Braun and Clarke (2006)’s approach saw the team ‘actively’ reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data. In phase 2, ‘codes’ were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Sawatsky, Parekh, Muula, Mbata, & Bui, 2016; Voloch, Judd, & Sakamoto, 2007) and collated into a code book to code and analyse the rest of the articles using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerged, these were associated with previous codes and concepts (Price & Schofield, 2015). In phase 3, the categories were organised into themes that best depict the data. In phase 4, the themes were refined to best represent the whole data set and discussed. In phase 5, the research team discussed the results of their independent analysis online and at reviewer meetings. “Negotiated consensual validation” was used to determine a final list of themes (Sambunjak et al., 2010).

2) Directed content analysis: Hsieh and Shannon (2005)’s approach to directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) was employed in three stages.

Using deductive category application (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Wagner-Menghin, de Bruin, & van Merriënboer, 2016), the first stage (Mayring, 2004; Wagner-Menghin et al., 2016) saw codes drawn from the article “Enhancing collaborative communication of nurse and physician leadership into two intensive care units” (D. K. Boyle & Kochinda, 2004). Drawing upon Mayring (2004)’s account, each code was defined in the code book that contained “explicit examples, definitions and rules” drawn from the data. The code book served to guide the subsequent coding process.

Stage 2 saw the four reviewers using the ‘code book’ to independently extract and code the relevant data from the included articles. Any relevant data not captured by these codes were assigned a new code that was also described in the code book. In keeping with deductive category application (Wagner-Menghin et al., 2016), coding categories and their definitions were revised. The final codes were compared and discussed with the final author to enhance the reliability of the process (Wagner-Menghin et al., 2016). The final author checked the primary data sources to ensure that the codes made sense and were consistently employed. The reviewers and the final author used “negotiated consensual validation” to resolve any differences in the coding (Sambunjak et al., 2010). The final categories were selected (Neal, Neal, Lawlor, Mills, & McAlindon, 2018) based on whether they appeared in more than 70% of the articles reviewed (Curtis et al., 2001b; Humble, 2009).

The narrative produced was guided by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide (Haig & Dozier, 2003) and the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement (Gordon & Gibbs, 2014).

III. RESULTS

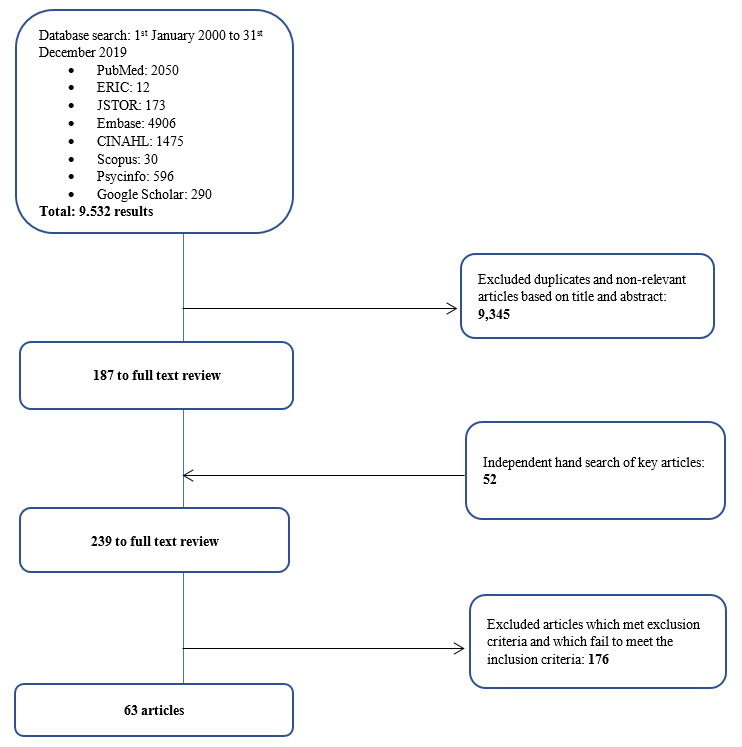

9532 abstracts were identified from ten databases, 239 articles reviewed, and 63 articles were included as shown in Figure 2 (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

Figure 2. PRISMA Flowchart

3) Comparisons between summaries of the included articles, thematic analysis and directed content analysis: In keeping with SEBA approach the findings of each arm of the split approach was discussed amongst the research and expert teams. The themes identified using Braun and Clarke (2006)’s approach to thematic analysis were how to teach and evaluate communication training in ICU and the factors affecting training.

The categories identified using Hsieh and Shannon (2005)’s approach to directed content analysis were 1) strategies employed to teach communication, 2) factors affecting communication training, 3) strategies employed to evaluate communication, and 4) outcomes of communication training. These categories reflected the major issues identified in the tabulated summaries.

These findings were reviewed with the expert team who agreed that given that the themes identified could be encapsulated by the categories identified, the categories and the themes will be presented together.

a) Strategies employed to teach communication in ICU: 61 articles described various interventions used to teach communication in the ICU. 19 involved ICU physicians, 18 involved ICU nurses, 4 saw participation of ICU physicians and nurses, 13 included the multidisciplinary team in the ICU, 1 was aimed at medical interns, 2 at medical students, 2 at nursing students, and 2 at both medical and nursing students. Given the overlap between teaching strategies, topics taught, and assessment methods employed in ICU communication training for nurses, doctors, nursing and medical students and HCPs in the literature, we discuss and generalise the results across HCPs.

In curriculum design, seven studies (D. K. Boyle & Kochinda, 2004; Hope et al., 2015; Krimshtein et al., 2011; Lorin, Rho, Wisnivesky, & Nierman, 2006; McCallister, Gustin, Wells-Di Gregorio, Way, & Mastronarde, 2015; Miller et al., 2018; Sullivan, Rock, Gadmer, Norwich, & Schwartzstein, 2016) designed a curriculum based on extensive reviews of literature on teaching communication. Brunette and Thibodeau-Jarry (2017) used Kern’s 6-step approach to curriculum development to design a structured curriculum targeted at meeting the needs identified whilst Sullivan et al. (2016) and Lorin et al. (2006) used the authors’ own experiences in tandem with existing literature to guide curriculum design. W. G. Anderson et al. (2017) designed a communication training workshop based on behaviour theories whilst McCallister et al. (2015) based their curriculum on principles of shared decision-making and patient-centred communication. Northam, Hercelinskyj, Grealish, and Mak (2015) conducted a pilot study before implementing their intervention.

Topics included in the curriculum were categorised into “core topics”, or topics essential to the curriculum, and “advanced” which may be useful to incorporate into the curriculum. Core topics were deemed as topics that were most frequently cited in the literature or are crucial across a variety of interactions in the ICU setting such as history taking, relationship skills as well as on common scenarios in the ICU such as breaking bad news and communicating difficult decisions. “Advanced’ topics, though important, are not mentioned as frequently and appeared to be more site specific and sociocultural and ethical issues. These topics are outlined in Table 2 (full table with references found in Supplementary Material B). The methods employed are outlined in Table 3 (full table with references found in Supplementary Material C).

|

|

Curriculum |

|

Core curriculum content |

Communication skills – With families (n=25) – With patients (n=5) – With HCPs (n=12) – General principles |

|

Breaking bad news |

|

|

Understanding/defining goals of care, building therapeutic relationships with families, setting goals and expectations, shared decision making |

|

|

Eliciting understanding and providing information about a patient’s clinical status |

|

|

Relationship skills – Recognising and dealing with strong emotions – Empathy Relationship skills include the “key principles” of esteem, empathy, involvement, sharing, and support |

|

|

Problem solving/conflict management/facing challenges |

|

|

Frameworks for good communication – Ask-Tell-Ask – “Tell Me More” – “SBAR” – Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation: to share information obtained in discussions with patients or family members with other HCPs – “3Ws” – What I see, What I’m concerned about, and What I want – Four-Step Assertive Communication Tool – get attention, state the concern (eg, “I’m concerned about…” or “I’m uncomfortable with…”), offer a solution, and get resolution by ending with a question (eg, “Do you agree?”) – “4 C’s” palliative communication model: a. Convening – ensuring necessary communication occurs between the patient, family, and interprofessional team; b. Checking – for understanding; c. Caring – conveying empathy and responding to emotion; and d. Continuing – following up with patients and families after discussions to provide support and clarify information. – ‘‘Communication Strategy of the Week’’ using teaching posters – PACIENTE Interview (Introduce yourself, Listen carefully, Tell you the diagnosis, Advises treatment, Exposes the prognosis, Appoints the bad news introductory phrases, Takes time to comfort empathic, Explains a plan of action involving the family) – Stages of communication (open, clarify, develop, agree, close) – Processes of communication (procedural suggestions, check for understanding) – Explain illness in clear, simple terms – Using a reference manual and pocket reference cards – How HCPs should introduce himself to patients/family members/other HCPs |

|

|

ICU decision making – Survival after CPR – DNR discussions – Prognostication – Legal and ethical issues surrounding life-sustaining treatment decisions – Withdrawing therapies |

|

|

Advanced Topics |

Ethics – Eg. Offering organ donation |

|

Cultural/spirituality/religious issues |

|

|

Leadership |

|

|

Roles and responsibilities in communication with patients and families |

|

|

Discussing patient safety incidents |

|

|

Integration of 5 common behaviour theories: health belief model, theory of planned behaviour, social cognitive theory, an ecological perspective, and transtheoretical model |

|

|

Law |

Table 2. Topics taught

|

Methods Employed |

Number of Studies |

|

Didactic Teaching, which may be employed in conjunction with other methods in a structured programme |

20 |

|

Simulated scenarios with family members/ standardised patients |

17 |

|

Role-play |

12 |

|

Use of simulation technology such as with mannequins |

6 |

|

Group discussions, group reflections and team-based learning |

7 |

|

Case presentations, case discussions and patient care conferences |

4 |

|

Online videos |

3 |

|

Online Powerpoint slides |

3 |

|

Did not specify |

9 |

Table 3. Pedagogy

b) Factors affecting communication training: Identifying facilitators and barriers are critical to the success of communication programmes. Facilitators and barriers to training may be found in Table 4 (full table with references may be found in Supplementary Material D).

|

Facilitators |

Barriers |

|

Longitudinal, structured process with horizontal and vertical integration |

Lack of time |

|

Safe learning environment |

Resource constraints |

|

Clear programme objectives and programme content |

Poor design and a lack of longitudinal support |

|

Funding for training |

Insecurity and awkwardness during simulations |

|

Simulated patients |

Disrupted training |

|

Protected time for training |

Programmes that were not pitched at the right level |

|

Faculty experts helping to plan and review curricula and implement interventions |

Training that is not learner centered |

|

Stakeholders’ engagement to facilitate interprofessional collaboration, as well as debriefing and program feedback |

Training that lacked feedback or debrief sessions |

|

Reflective practice |

Lack of a longitudinal aspect to training |

|

Timely and appropriate feedback |

A lack of a supportive environment in which HCPs can apply the skills learnt |

|

Multidisciplinary learning |

Discordance between physicians’ and nurses’ communication with families |

|

Role modeling |

|

|

Peer support |

Table 4. Facilitators and barriers to training

c) Strategies employed to evaluate communication training: Thirty-nine articles discussed evaluation methods of communication training. The assessment methods are described as follows in Table 5 (full table with references may be found in Supplementary Material E).

|

Method |

|

|

Self-assessment |

|

|

1 |

Quantitative and qualitative surveys were administered to learners to assess their knowledge, experience in the programme, and perceived preparedness, comfort and confidence in communicating |

|

1.1 |

Some programmes only used post-intervention assessments |

|

1.2 |

Others used a combination of pre- and post-intervention assessments of learners |

|

1.3 |

Some programmes adapted existing tools to conduct post-intervention surveys to evaluate learners’ experiences and skills learnt |

|

Feedback from Others |

|

|

2 |

patients, family members, peers and simulated patients was obtained through a combination of surveys and interviews that assessed their level of satisfaction with learners’ communication skills |

|

Observation |

|

|

3 |

Direct observation of HCPs’ communication skills to ascertain the frequency, quality, success and ease of communication post-intervention. This was done through the use of modified communication tools and feedback forms |

|

Debriefing Sessions |

|

|

4 |

One study used debriefing sessions to understand shared experiences of learners. |

Table 5. Assessment Methods

d) Outcomes of communication training: The outcomes of communication training may be mapped to 5 levels of the Adapted Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy (Jamieson, Palermo, Hay, & Gibson, 2019; Littlewood et al., 2005; Roland, 2015) allowing outcome measures used were also identified. Majority of the programmes achieved Level 2a and Level 2b outcomes as shown in Table 6 (full table with references may be found in Supplementary Material F). 40 articles described successes and three articles described variable outcomes of teaching communications.

|

Adapted Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy |

Items evaluated |

|

Level 1 (participation) |

Experience in the programme |

|

Assessment of programme’s effectiveness |

|

|

Trainee satisfaction |

|

|

Programme completion |

|

|

Level 2a (attitudes and perception) |

Attitudes towards/ experience with communication |

|

Self-rated confidence/ preparedness in communication |

|

|

Colleagues’ satisfaction with communication |

|

|

Trainees’ views on training programme (e.g. satisfaction, perceived effectiveness) |

|

|

Self-perceived job stress/ job satisfaction |

|

|

Level 2b (knowledge and skills) |

Self-rated skill level using Likert scales |

|

Form asking trainees to list/ indicates skills they learnt during the programme |

|

|

Self-rated knowledge level using Likert scales |

|

|

Self-evaluation of communication skills using validated tools |

|

|

Evaluation of trainees’ knowledge by faculty/ experts |

|

|

Evaluation of trainees’ communication skills by faculty/ experts |

|

|

Level 3 (behavioural change) |

Feedback from peers and facilitators on interactions with actors |

|

Records of ICU rounds |

|

|

Notes from colleagues documenting supportive environment and involvement in communication |

|

|

Frequency of usage of communication skills taught |

|

|

Workplace observations |

|

|

Evaluation of trainees’ communication skills in clinical setting by patients and colleagues |

|

|

Level 4a (increased interprofessional collaboration) |

Workplace observations |

|

Level 4b (patient benefits) |

Self-perceived quality of care |

|

Patient and family satisfaction with communication |

|

|

Family satisfaction with communication |

Table 6. Outcome Measures mapped onto Adapted Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy

Three studies compared outcomes with non-intervention arms and reported improved patient satisfaction and self-rated and third party reported improvements in communication (Awdish et al., 2017; Happ et al., 2014; McCallister et al., 2015).

C. Stage 3: Jigsaw Perspective

The jigsaw perspective builds upon Moss and Haertel’s (2016) concept of methodological pluralism and sees data from different methodological approaches as pieces of a jigsaw providing a partial picture of the area of interest. The Jigsaw perspective brings data from complementary pieces of the training process in order to paint a cohesive picture of ICU communication training. As a result, related aspects of the training structure and the working culture were studied together so as to better understand the influences each of the aforementioned have on the other.

D.Stage 4. An Iterative Process

Whilst there was consensus on the themes/categories identified, the expert team and stakeholders raised concerns that data from grey literature which is neither quality assessed nor necessarily evidenced based could bias the discussion. To address this concern, the research team thematically analysed the data from grey literature and non-research-based pieces such as letters, opinion and perspective pieces, commentaries and editorials drawn from the bibliographic databases separately and compared these themes against themes drawn from peer reviewed evidenced based data. This analysis revealed the same themes with an additional tool (PACIENTE tool) identified in the grey literature to enhance communication with patients’ families (Pabon et al., 2014).

IV. DISCUSSION

E. Stage 5. Synthesis of Systematic Scoping Review in SEBA

This SSR in SEBA reaffirms the importance of communications training in ICU and suggests that a combination of training techniques is required (Akgun & Siegel, 2012; Chiarchiaro et al., 2015; Happ et al., 2010; Happ et al., 2015; Hope et al., 2015; Lorin et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2018; Roze des Ordons, Doig, Couillard, & Lord, 2017; Sandahl, et al., 2013; D. J. Shaw, Davidson, Smilde, Sondoozi, & Agan, 2014).

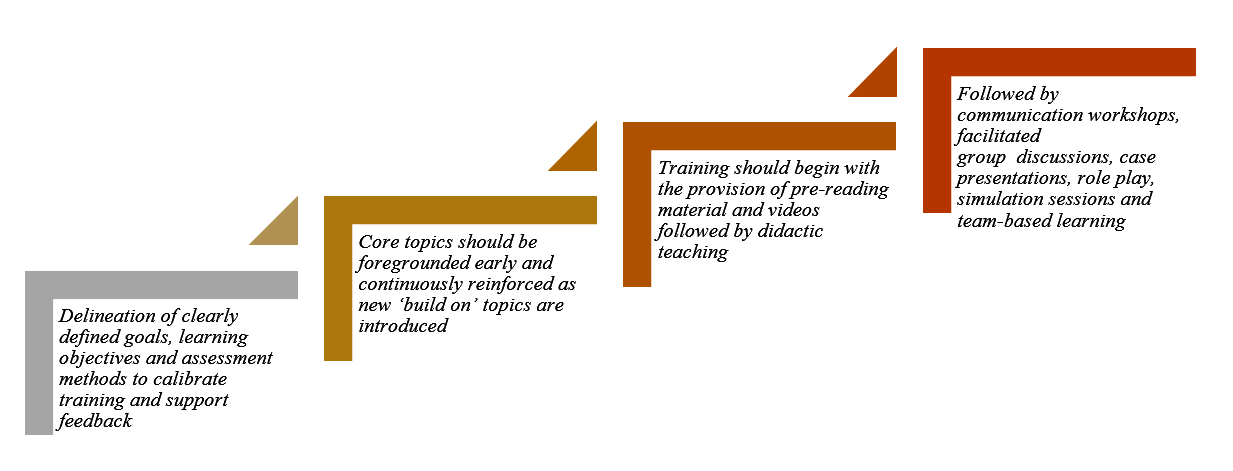

A framework for the design of a competency-based approach to ICU communications training (W. G. Anderson et al., 2017; Berkenstadt et al., 2013; D. Boyle et al., 2016; Brown, Durve, Singh, Park, & Clark, 2017; Chiarchiaro et al., 2015; Fins & Solomon, 2001; Happ et al., 2010; Hope et al., 2015; Karlsen, Gabrielsen, Falch, & Stubberud, 2017; Pabon et al., 2014; Roze des Ordons et al., 2017; Tamerius, 2013; J. Yuen & Carrington Reid, 2011) may be found in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Framework for Competency-based Approach to ICU Communication Skills Training

These findings resonate with Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy (Jamieson et al., 2019; Littlewood et al., 2005; Roland, 2015) where each level builds upon the next and the learner moves from “peripheral participation” to active “doing and internalising” in real clinical practice.

Such a competency-based programme necessitates a structured approach to holistic and longitudinal assessments of the learner’s progress. Such a structured approach must be horizontally and vertically integrated into other forms of clinical training as cogent communication is a fundamental skillset across all practice and specialties (Akgun & Siegel, 2012; Roze des Ordons et al., 2017).

Whilst Kirkpatrick’s Hierarchy offers a viable framework for assessing trainees’ progress (Boothby, Gropelli, & Succheralli, 2018; Roze des Ordons et al., 2017), ICU training programmes may also keep in mind the various outcomes measures listed previously in Table 3 when designing assessment tools. These tools should conscientiously account for perspectives offered by trainers, standardised patients and family members involved in the evaluation process and should consider benefits and repercussions of their communication abilities to patients, families and the ICU multidisciplinary team(Aslakson, Randall Curtis, & Nelson, 2014; Awdish et al., 2017; Blackhall et al., 2014; D. A. Boyle et al., 2017; DeMartino, Kelm, Srivali, & Ramar, 2016; Happ et al., 2014; Happ et al., 2015; Hope et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2018; Sanchez Exposito et al., 2018; Sullivan et al., 2016; Turkelson, Aebersold, Redman, & Tschannen, 2017).

With flexibility within training programmes highlighted as essential (Ernecoff et al., 2016), this flexibility should also extend to cover remediation and provision of additional support in areas jointly identified and agreed upon by trainees and trainers to be paramount for targeted improvement. As it is worrying that no studies have focused on the effects of remediation on ICU communication skills training thus far, this should be a critical area for future research considering its importance (Steinert, 2013).

Likewise, it is pivotal that trainers should undergo rigorous training (Berlacher et al., 2017; Roze des Ordons et al., 2017) and are granted protected time for this undertaking (Boothby et al., 2018; Happ et al., 2010; Roze des Ordons et al., 2017). In order to ensure that quality and up-to-date skills and knowledge are transferred down the line, it is posited that trainers should also be holistically and longitudinally assessed alongside their charges (Roze des Ordons et al., 2017). Whilst trainers should ideally nurture a safe, collaborative, learning environment for all (Hales & Hawryluck, 2008; Milic et al., 2015; Roze des Ordons et al., 2017; Sandahl, et al., 2013), it is clear that this can only be achieved through sustained administrative and financial support, according learners and trainers sufficient time and resources to foster cordial relationships open to mutual and honest feedback (Akgun & Siegel, 2012; Miller et al., 2018).

V. LIMITATIONS

The SSR in SEBA approach is robust, reproducible and transparent addressing many of the concerns about inconsistencies in SSR methodology and structure arising from diverse epistemological lenses and lack of cogency in weaving together context-sensitive medical education programmes. Through a reiterative step-by-step process, the hallmark ‘Split Approach’ which saw concurrent and independent analyses and tabulated summaries by separate teams of researchers allowed for a holistic picture of prevailing ICU communications training programmes without loss of any conflicting data. Consultations with experts every step of the way also significantly curtailed researcher bias and enhanced the accountability and coherency of the data.

Yet it must be acknowledged that this SSR focused on articles published in English or with English translations. Hence, much of the data comes from North American and European countries, potentially skewing perspectives and raising questions as to the applicability of these findings in the setting of other cultures. Moreover, whilst databases used were selected by the expert team and the team utilised independent selection processes, critical papers may still have been unintentionally omitted. Whilst use of thematic analysis to review the impact of the grey literature greatly improves transparency of the review, inclusion of grey literature-based themes may nonetheless bias results and provide these opinion-based views with a ‘veneer of respectability’ despite a lack of evidence to support it.

VI. CONCLUSION

In the absence of a standardised evidence-based communication training programme for HCPs in ICUs, many HCPs are left in the hope that clinical experience alone will be sufficient to ensure their proficiency in communication. This SSR provides guidance on how to effectively develop and structure a communications training programme for HCPs in ICUs and suggests that communications training in ICU must involve a structured multimodal approach to training carried out in a supportive learning environment. This must be accompanied by robust methods of assessment and personalised and timely feedback and support of the trainees. Such an approach will equip HCPs with greater confidence and preparedness in a variety of situations, including that of the evolving COVID-19 pandemic.

To effectively institute change in communication training within ICUs, further studies should look into the desired characteristics of trainers and trainees, the context and settings as well as the case scenarios used. The design of an effective tool to evaluate learners’ communication skills longitudinally, holistically, and in different settings should be amongst the primary concerns for future research.

Notes on Contributors

Dr EWYC recently graduated from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms HH is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms SG is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms MTP is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms CCYL is a nursing student at Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms LHET is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Dr MSQK recently graduated from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Dr KTT recently graduated from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. He was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms YTO is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Mr WQL is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. He was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms XHT is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Mr YHT is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. He was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms CSK is a medical student at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms AMCC is a senior librarian from Medical Library, National University of Singapore Libraries, National University of Singapore, Singapore. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ms MC is a researcher at the Division of Cancer Education, NCCS. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Dr JXZ is a Consultant at the Division of Supportive and Palliative Care, NCCS. She was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Professor LKRK is a Senior Consultant at the Division of Supportive and Palliative Care, NCCS. He was involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission.

Ethical Approval

This is a systematic scoping review study which does not require ethical approval.

Acknowledgement

This work was carried out as part of the Palliative Medicine Initiative run by the Department of Supportive and Palliative Care at the National Cancer Centre Singapore. The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study.

Funding

There is no funding for the paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Adams, A. M. N., Mannix, T., & Harrington, A. (2017). Nurses’ communication with families in the intensive care unit – A literature review. Nursing in Critical Care, 22(2), 70-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12141

Ahrens, T., Yancey, V., & Kollef, M. (2003). Improving family communications at the end of life: implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. American Journal of Critical Care, 12(4), 317-323. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2003.12.4.317

Akgun, K. M., & Siegel, M. D. (2012). Using standardized family members to teach end-of-life skills to critical care trainees. Critical Care Medicine, 40(6), 1978-1980. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182536cd1

Anderson, K. G., & Milic, M. (2017). Doctor know thyself: Improving patient communication through modeling and self-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(2), S670-S671.

Anderson, W. G., Puntillo, K., Cimino, J., Noort, J., Pearson, D., Boyle, D., . . . Pantilat, S. Z. (2017). Palliative care professional development for critical care nurses: A multicenter program. American Journal of Critical Care, 26(5), 361-371. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2017336

Anstey, M. (2013). Communication training in the ICU: Room for improvement? Critical Care Medicine, 41(12), A179. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000439963.49763.f2

Aslakson, R. A., Curtis, J. R., & Nelson, J. E. (2014). The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 42(11), 2418-2428. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000573

Awdish, R. L., Buick, D., Kokas, M., Berlin, H., Jackman, C., Williamson, C., . . . Chasteen, K. (2017). A communications bundle to improve satisfaction for critically ill patients and their families: A prospective, cohort pilot study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(3), 644-649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.024

Barbour, S., Puntillo, K., Cimino, J., & Anderson, W. (2016). Integrating multidisciplinary palliative care into the ICU (impact-ICU) project: A multi-center nurse education quality improvement initiative. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(2), 355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.203

Barth, M., Kaffine, K., Bannon, M., Connelly, E., Tescher, A., Boyle, C., … Ballinger, B. (2013). 827: Goals of care conversations: A collaborative approach to the process in a Surgical/Trauma ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 41(12), A206. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000440065.45453.3f

Berkenstadt, H., Perlson, D., Shalomson, O., Tuval, A., Haviv-Yadid, Y., & Ziv, A. (2013). Simulation-based intervention to improve anesthesiology residents communication with families of critically ill patients–preliminary prospective evaluation. Harefuah, 152(8), 453-456, 500, 499.

Berlacher, K., Arnold, R. M., Reitschuler-Cross, E., Teuteberg, J., & Teuteberg, W. (2017). The Impact of Communication Skills Training on Cardiology Fellows’ and Attending Physicians’ Perceived Comfort with Difficult Conversations. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(7), 767-769. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0509

Blackhall, L. J., Erickson, J., Brashers, V., Owen, J., & Thomas, S. (2014). Development and validation of a collaborative behaviors objective assessment tool for end-of-life communication. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(1), 68-74. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0262

Bloomer, M. J., Endacott, R., Ranse, K., & Coombs, M. A. (2017). Navigating communication with families during withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in intensive care: a qualitative descriptive study in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(5-6), 690-697. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13585

Boothby, J., Gropelli, T., & Succheralli, L. (2018). An Innovative Teaching Model Using Intraprofessional Simulations. Nursing Education Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Nep.0000000000000340

Boyle, D., Grywalski, M., Noort, J., Cain, J., Herman, H., & Anderson, W. (2016). Enhancing bedside nurses’ palliative communication skill competency: An exemplar from the University of California academic Hospitals’ qualiy improvement collaborative. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(1), S25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3209-z

Boyle, D. A., & Anderson, W. G. (2015). Enhancing the communication skills of critical care nurses: Focus on prognosis and goals of care discussions. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 22(12), 543-549.

Boyle, D. A., Barbour, S., Anderson, W., Noort, J., Grywalski, M., Myer, J., & Hermann, H. (2017). Palliative Care Communication in the ICU: Implications for an Oncology-Critical Care Nursing Partnership. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 33(5), 544-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2017.10.003

Boyle, D. K., & Kochinda, C. (2004). Enhancing collaborative communication of nurse and physician leadership in two intensive care units. Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(2), 60-70.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, S., Durve, M. V., Singh, N., Park, W. H. E., & Clark, B. (2017). Experience of ‘parallel communications’ training, a novel communication skills workshop, in 50 critical care nurses in a UK Hospital. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-017-0151-4

Brunette, V., & Thibodeau-Jarry, N. (2017). Simulation as a Tool to Ensure Competency and Quality of Care in the Cardiac Critical Care Unit. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 33(1), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.10.015

Cameron, K. (2017). Bridging the Gaps: An Experiential Commentary on Building Capacity for Interdisciplinary Communication in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU). Canadian Journal of Critical Care Nursing, 28(2), 53-54.

Cao, V., Tan, L. D., Horn, F., Bland, D., Giri, P., Maken, K., … Nguyen, H. B. (2018). Patient-Centered Structured Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds in the Medical ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 46(1), 85-92. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000002807

Centofanti, J., Duan, E., Hoad, N., Swinton, M., Perri, D., Waugh, L., . . . Cook, D. (2015). Improving an ICU daily goals checklist: Integrated and end-of-grant knowledge translation. Canadian Respiratory Journal, 22(2), 80.

Centofanti, J., Duan, E., Hoad, N., Waugh, L., & Perri, D. (2012). Residents’ perspectives on a daily goals checklist: A mixed-methods study. Critical Care Medicine, 40(12), 150. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000425605.04623.4b

Chiarchiaro, J., Schuster, R. A., Ernecoff, N. C., Barnato, A. E., Arnold, R. M., & White, D. B. (2015). Developing a simulation to study conflict in intensive care units. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 12(4), 526-532. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-495OC

Cicekci, F., Duran, N., Ayhan, B., Arican, S., Ilban, O., Kara, I., … Kara, I. (2017). The communication between patient relatives and physicians in intensive care units. BMC Anesthesiology, 17(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-017-0388-1

Clark, E., Squire, S., Heyme, A., Mickle, M. E., & Petrie, E. (2009). The PACT Project: Improving communication at handover. Medical Journal of Australia, 190(S11), S125-S127. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02618.x

Crotty, M. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Thousand Oaks, United States: Sage Publications Inc.

Currey, J., Oldland, E., Considine, J., Glanville, D., & Story, I. (2015). Evaluation of postgraduate critical care nursing students’ attitudes to, and engagement with, Team-Based Learning: A descriptive study. Intensive Critical Care Nursing, 31(1), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2014.09.003

Curtis, J. R., Engelberg, R. A., Wenrich, M. D., Shannon, S. E., Treece, P. D., & Rubenfeld, G. D. (2005). Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine, 171(8), 844-849. https://doi.org/ 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC

Curtis, J. R., Patrick, D. L., Shannon, S. E., Treece, P. D., Engelberg, R. A., & Rubenfeld, G. D. (2001a). The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Opportunities for improvement. Critical Care Medicine, 29(2 Suppl), N26-33.

Curtis, J. R., Wenrich, M. D., Carline, J. D., Shannon, S. E., Ambrozy, D. M., & Ramsey, P. G. (2001b). Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end‐of‐life care: Perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(1), 41-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00333.x

Curtis, J. R., White, D. B., Curtis, J. R., & White, D. B. (2008). Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. CHEST, 134(4), 835-843. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-0235

DeMartino, E. S., Kelm, D. J., Srivali, N., & Ramar, K. (2016). Education considerations: Communication curricula, simulated resuscitation, and duty hour restrictions. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 193(7), 801-803. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201510-2012RR

Dithole, K. S., Sibanda, S., Moleki, M. M., & Thupayagale ‐ Tshweneagae, G. (2016). Nurses’ communication with patients who are mechanically ventilated in intensive care: the Botswana experience. International Nursing Review, 63(3), 415-421. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12262

Dorner, L., Schwarzkopf, D., Skupin, H., Philipp, S., Gugel, K., Meissner, W., … Hartog, C. S. (2015). Teaching medical students to talk about death and dying in the ICU: Feasibility of a peer-tutored workshop. Intensive Care Medicine, 41(1), 162-163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3541-z

Downar, J., Knickle, K., Granton, J. T., & Hawryluck, L. (2012). Using standardized family members to teach communication skills and ethical principles to critical care trainees. Critical Care Medicine, 40(6), 1814-1819. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e0fb7

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Ernecoff, N. C., Witteman, H. O., Chon, K., Buddadhumaruk, P., Chiarchiaro, J., Shotsberger, K. J., … & Lo, B. (2016). Key stakeholders’ perceptions of the acceptability and usefulness of a tablet-based tool to improve communication and shared decision making in ICUs. Journal of Critical Care, 33, 19-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.01.030

Fins, J. J., & Solomon, M. Z. (2001). Communication in intensive care settings: The challenge of futility disputes. Critical Care Medicine, 29(2 Suppl), N10-N15.

Foa, C., Cavalli, L., Maltoni, A., Tosello, N., Sangilles, C., Maron, I., … Artioli, G. (2016). Communications and relationships between patient and nurse in Intensive Care Unit: Knowledge, knowledge of the work, knowledge of the emotional state. Acta Bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis, 87(4-s), 71-82.

Ford, D. W., Downey, L., Engelberg, R., Back, A. L., & Curtis, J. R. (2012). Discussing religion and spirituality is an advanced communication skill: An exploratory structural equation model of physician trainee self-ratings. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(1), 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0168

Gordon, M., & Gibbs, T. (2014). STORIES statement: Publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC medicine, 12(1), 143.

Haig, A., & Dozier, M. (2003). BEME Guide no 3: Systematic searching for evidence in medical education–Part 1: Sources of information. Medical Teacher, 25(4), 352-363. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/0142159031000136815

Hales, B. M., & Hawryluck, L. (2008). An interactive educational workshop to improve end of life communication skills. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 28(4), 241-248; quiz 249-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.191

Happ, M. B., Baumann, B. M., Sawicki, J., Tate, J. A., George, E. L., & Barnato, A. E. (2010). SPEACS-2: intensive care unit “communication rounds” with speech language pathology. Geriatric Nursing, 31(3), 170-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.03.004

Happ, M. B., Garrett, K. L., Tate, J. A., DiVirgilio, D., Houze, M. P., Demirci, J. R., … Sereika, S. M. (2014). Effect of a multi-level intervention on nurse–patient communication in the intensive care unit: Results of the SPEACS trial. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 43(2), 89-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.010

Happ, M. B., Sereika, S. M., Houze, M. P., Seaman, J. B., Tate, J. A., Nilsen, M. L., … Barnato, A. E. (2015). Quality of care and resource use among mechanically ventilated patients before and after an intervention to assist nurse-nonvocal patient communication. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 44(5), 408-415.e402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.07.001

Havrilla-Smithburger, P., Kane-Gill, S., & Seybert, A. (2012). Use of high fidelity simulation for interprofessional education in an ICU environment. Critical Care Medicine, 40(12), 148. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000425605.04623.4b

Hope, A. A., Hsieh, S. J., Howes, J. M., Keene, A. B., Fausto, J. A., Pinto, P. A., & Gong, M. N. (2015). Let’s talk critical: Development and evaluation of a communication skills training programme for critical care fellows. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 12(4), 505-511. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-040OC

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hughes, E. A. (2010). Crucial conversations: Perceptions of staff and patients’ families of communication in an intensive care unit. Dissertation Abstracts International, 71(5-A), 1548.

Humble, Á. M. (2009). Technique triangulation for validation in directed content analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 34-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800305

Jamieson, J., Palermo, C., Hay, M., & Gibson, S. (2019). Assessment practices for dietetics trainees: A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(2), 272-292. e223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.010

Kalocsai, C., Amaral, A., Piquette, D., Walter, G., Dev, S. P., Taylor, P., . . . Gotlib Conn, L. (2018). “It’s better to have three brains working instead of one”: a qualitative study of building therapeutic alliance with family members of critically ill patients. BMC health services research, 18(1), 533. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3341-1

Karlsen, M.-M. W., Gabrielsen, A. K., Falch, A. L., & Stubberud, D.-G. (2017). Intensive care nursing students’ perceptions of simulation for learning confirming communication skills: A descriptive qualitative study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 42, 97-104. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.005

Kirchhoff, K. T., Walker, L., Hutton, A., Spuhler, V., Cole, B. V., & Clemmer, T. (2002). The vortex: Families’ experiences with death in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 11(3), 200-209. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2002.11.3.200

Kleinpell, R. M. (2014). Improving communication in the ICU. Heart and Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 43(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.01.008

Kow, C. S., Teo, Y. H., Teo, Y. N., Chua, K. Z. Y., Quah, E. L. Y., Kamal, N. H. B. A., . . . Tay, K. T. J. B. M. E. (2020). A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3

Krimshtein, N. S., Luhrs, C. A., Puntillo, K. A., Cortez, T. B., Livote, E. E., Penrod, J. D., & Nelson, J. E. (2011). Training nurses for interdisciplinary communication with families in the intensive care unit: An intervention. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(12), 1325-1332. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0225

Krishna, L. K. R., Tan, L. H. E., Ong, Y. T., Tay, K. T., Hee, J. M., Chiam, M., … & Kow, C. S. (2020). Enhancing mentoring in palliative pare: An evidence based mentoring Framework. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 2382120520957649. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520957649

Littlewood, S., Ypinazar, V., Margolis, S. A., Scherpbier, A., Spencer, J., & Dornan, T. (2005). Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: Systematic review. The BMJ, 331(7513), 387-391. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmj.331.7513.387

Lorin, S., Rho, L., Wisnivesky, J. P., & Nierman, D. M. (2006). Improving medical student intensive care unit communication skills: A novel educational initiative using standardized family members. Critical Care Medicine, 34(9), 2386-2391. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Ccm.0000230239.04781.Bd

Mayring, P. (2004). Qualitative content analysis. A companion to qualitative research, 1(2004), 159-176.

McCallister, J. W., Gustin, J. L., Wells-Di Gregorio, S., Way, D. P., & Mastronarde, J. G. (2015). Communication skills training curriculum for pulmonary and critical care fellows. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 12(4), 520-525. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-039OC

Milic, M. M., Puntillo, K., Turner, K., Joseph, D., Peters, N., Ryan, R., … Anderson, W. G. (2015). Communicating with patients’ families and physicians about prognosis and goals of care. American Journal of Critical Care, 24(4), e56-64. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2015855

Miller, D. C., Sullivan, A. M., Soffler, M., Armstrong, B., Anandaiah, A., Rock, L., … Hayes, M. M. (2018). Teaching residents how to talk about death and dying: A mixed-methods analysis of barriers and randomized educational intervention. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 35(9), 1221-1226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118769674

Ministry of Health, Singapore. (2020). Updates on COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) local situation. Retrieved from https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269.

Moss, P. A., & Haertel, E. H. (2016). Engaging methodological pluralism. In Drew H. Gitomer & Courtney A. Bell (Eds) Handbook of Research on Teaching (5th ed., pp. 127-247). Washington, D.C: American Educational Research Association

Motta, M., Ryder, T., Blaber, B., Bautista, M., & Lim-Hing, K. (2018). Multimodal communication enhances family engagement in the neurocritical care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 46, 409. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000528859.01109.0f

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Neal, J. W., Neal, Z. P., Lawlor, J. A., Mills, K. J., & McAlindon, K. (2018). What makes research useful for public school educators? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 432-446.

Ng, Y. X., Koh, Z. Y. K., Yap, H. W., Tay, K. T., Tan, X. H., Ong, Y. T., … Shivananda, S. J. P. o. (2020). Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLOS One, 15(5), e0232511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232511

Ngiam, L. X. L., Ong, Y. T., Ng, J. X., Kuek, J. T. Y., Chia, J. L., Chan, N. P. X., … & Ng, C. H. (2020). Impact of caring for terminally ill children on physicians: A systematic scoping review. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 1049909120950301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120950301

Northam, H. L., Hercelinskyj, G., Grealish, L., & Mak, A. S. (2015). Developing graduate student competency in providing culturally sensitive end of life care in critical care environments – A pilot study of a teaching innovation. Australian Critical Care, 28(4), 189-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2014.12.003

Pabon, M. C., Roldan, V. C., Insuasty, A., Buritica, L. S., Taboada, H., & Mendez, L. U. (2014). Paciente a semi-structured interview enhances family communication in the ICU. Cirtical Care Medicine, 42(12), A1507. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000458108.38450.38

Pantilat, S., Anderson, W., Puntillo, K., & Cimino, J. (2014). Palliative care in university of California intensive care units. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(3), A15. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.9449

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015a). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. (2015b). The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., … Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme. Version, 1, b92.

Price, S., & Schofield, S. (2015). How do junior doctors in the UK learn to provide end of life care: A qualitative evaluation of postgraduate education. BMC Palliative Care, 14, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-015-0039-6

Pring, R. (2000). The ‘False Dualism’ of educational research. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 34(2), 247-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.00171

Rachwal, C. M., Langer, T., Trainor, B. P., Bell, M. A., Browning, D. M., & Meyer, E. C. (2018). Navigating communication challenges in clinical practice: A new approach to team education. Critical Care Nurse, 38(6), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn201874

Reed, D. A., Beckman, T. J., Wright, S. M., Levine, R. B., Kern, D. E., & Cook, D. A. (2008). Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s Medical Education Special Issue. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(7), 903-907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0664-3

Roland, D. (2015). Proposal of a linear rather than hierarchical evaluation of educational initiatives: The 7Is framework. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 12. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.35

Roze des Ordons, A. L., Doig, C. J., Couillard, P., & Lord, J. (2017). From communication skills to skillful communication: A longitudinal integrated curriculum for critical care medicine fellows. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92(4), 501-505. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001420

Roze Des Ordons, A. L., Lockyer, J., Hartwick, M., Sarti, A., & Ajjawi, R. (2016). An exploration of contextual dimensions impacting goals of care conversations in postgraduate medical education. BMC Palliative Care, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0107-6

Sambunjak, D., Straus, S. E., & Marusic, A. (2010). A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(1), 72-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8

Sanchez Exposito, J., Leal Costa, C., Diaz Agea, J. L., Carrillo Izquierdo, M. D., & Jimenez Rodriguez, D. (2018). Ensuring relational competency in critical care: Importance of nursing students’ communication skills. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 44, 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.08.010

Sandahl, C., Gustafsson, H., Wallin, C. J., Meurling, L., Ovretveit, J., Brommels, M., & Hansson, J. (2013). Simulation team training for improved teamwork in an intensive care unit. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 26(2), 174-188. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526861311297361

Sawatsky, A. P., Parekh, N., Muula, A. S., Mbata, I., & Bui, T. (2016). Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative study. Medical Education, 50(6), 657-669. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12999

Schick-Makaroff, K., MacDonald, M., Plummer, M., Burgess, J., & Neander, W. (2016). What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health, 3(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2016.1.172

Shannon, S. E., Long-Sutehall, T., & Coombs, M. (2011). Conversations in end-of-life care: Communication tools for critical care practitioners. Nursing Critical Care, 16(3), 124-130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-5153.2011.00456.x

Shaw, D., Davidson, J., Smilde, R., & Sondoozi, T. (2012). Interdisciplinary team training for family conferences in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 40(12), 226. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000425605.04623.4b

Shaw, D. J., Davidson, J. E., Smilde, R. I., Sondoozi, T., & Agan, D. (2014). Multidisciplinary team training to enhance family communication in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 42(2), 265-271. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a26ea5

Smith, L., O’Sullivan, P., Lo, B., & Chen, H. (2013). An educational intervention to improve resident comfort with communication at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(1), 54-59. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0173

Steinert, Y. J. M. t. (2013). The “problem” learner: Whose problem is it? AMEE Guide No. 76. 35(4), e1035-e1045. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.774082

Sullivan, A. M., Rock, L. K., Gadmer, N. M., Norwich, D. E., & Schwartzstein, R. M. (2016). The impact of resident training on communication with families in the intensive care unit resident and family outcomes. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 13(4), 512-521. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-495OC

Tamerius, N. (2013). Palliative care in the ICU: Improving patient outcomes. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(4), A19. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.9516

Thomson, N., Tan, M., Hellings, S., & Frys, L. (2016). Integrating regular multidisciplinary ‘insitu’ simulation into the education program of a critical care unit. How we do it. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 17(4), 73-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143717708966

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Turkelson, C., Aebersold, M., Redman, R., & Tschannen, D. (2017). Improving nursing communication skills in an intensive care unit using simulation and nursing crew resource management strategies: An implementation project. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 32(4), 331-339. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000241

Van Mol, M., Boeter, T., Verharen, L., & Nijkamp, M. (2014). To communicate with relatives; An evaluation of interventions in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 42(12), A1506-A1507. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000458107.38450.dc

Voloch, K. A., Judd, N., & Sakamoto, K. (2007). An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho’ola Post-Baccalaureate students at the University of Hawai’i John A. Burns School of Medicine. Hawaii Medical Journal, 66(4), 102-103.

Wagner-Menghin, M., de Bruin, A., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2016). Monitoring communication with patients: Analyzing judgments of satisfaction (JOS). Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21(3), 523-540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9642-9

Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., Buckingham, J., & Pawson, R. (2013). RAMESES publication standards: Meta-narrative reviews. BMC medicine, 11(1), 20. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20

World Health, O. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200330-sitrep-70-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=7e0fe3f8_2

Yang, X., Yu, Y., Xu, J., Shu, H., Liu, H., Wu, Y., … Yu, T. (2020). Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5

Yuen, J., & Carrington Reid, M. (2011). Development of an innovative workshop to teach communication skills in goals-of-care discussions in the ICU. Jounral of General Internal Medicine, 26, S605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1730-9

Yuen, J. K., Mehta, S. S., Roberts, J. E., Cooke, J. T., & Reid, M. C. (2013). A brief educational intervention to teach residents shared decision making in the intensive care unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(5), 531-536. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0356

*Ong Yun Ting

1E Kent Ridge Road,

NUHS Tower Block, Level 11,

Singapore 119228

Tel: +65 6227 3737

Email: e0326040@u.nus.edu

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.