A comparison of four models of professionalism in medical education

Submitted: 25 May 2020

Accepted: 30 December 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 24-31

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/RA2314

Maria Isabel Atienza

Curriculum and Instruction, College of Medicine, San Beda University, Philippines

Institute of Pediatrics & Child Health, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Global City, Philippines

Abstract

Introduction: The prevailing consensus is that medical professionalism must be formally included as a programme in the undergraduate medical curriculum.

Methods: A literature search was conducted to identify institutions that can serve as models for incorporating professionalism in medical education. Differences and similarities were highlighted based on a framework for the comparison which included the following features: Definition of professionalism, curricular design, student selection, teaching and learning innovations, role modelling and methods of assessment.

Results: Four models for integrating professionalism in medical education were chosen: Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM), University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM), University of Queensland (UQ) School of Medicine, and Mayo Clinic and Mayo Medical School. The task of preparing a programme on medical professionalism requires a well-described definition to set the direction for planning, implementing, and institutionalising professionalism. The programmes are best woven in all levels of medical education from the pre-clinical to the clinical years. The faculty physicians and the rest of the institution’s staff must also undergo a similar programme for professionalism.

Conclusion: The development of all scopes of professionalism requires constant planning, feedback and remediation. The students’ ability to handle professionalism challenges are related to how much learning situations the students encounter during medical school. The learning situations must be adjusted according to the level of responsibilities given to students. The goal of learning is to enable students to grow from a novice to a competent level and afterwards to a proficient and expert level handling professionalism challenges in medicine.

Keywords: Medical Professionalism, Medical Curriculum, Role Modelling in Medical Education, Culture of Medical Professionalism

Practice Highlights

- A programme on medical professionalism in education starts with a working definition of the term.

- The culture of professionalism must be articulated in the school’s vision and mission.

- The professionalism programme must be woven through the four years of medical education.

- Role models are essential in teaching medical professionalism.

- For teaching medical professionalism, a nurturing environment is preferable over punitive actions.

I. INTRODUCTION

There is a prevailing sentiment that professionalism must be taught formally and explicitly in all medical schools (Cruess & Cruess, 2006). This review aims to highlight some exceptional models for incorporating professionalism in the curriculum of medical education. The models were chosen based on the consensus among medical educators that medical schools need to respond to the following observations and recommendations from the vast literature on this subject:

1. Society expects physicians to act professionally (Lynch et al., 2004; Mueller, 2009; O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

2. There is a link between unprofessional behaviour in medical school and subsequent practice (Mueller, 2009; O’Sullivan et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2008).

3. Professionalism is associated with improved medical outcomes (Mueller, 2009).

4. Professionalism needs to be taught in the undergraduate medical institutions (O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

5. The teaching and learning must be coupled with a carefully constructed means of assessment of professionalism and professional behaviour (O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

6.Students must be supported in developing the skills for continuing professional development throughout their career (O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

This review aims to utilise these assumptions as a framework for reviewing and comparing models for the incorporation of medical professionalism in the curriculum of medical schools. This paper aims to provide answers to this question: Among medical schools that have incorporated professionalism in the medical curriculum, what are the salient features of the programmes that may be adopted by other institutions in need of such curricular innovations?

II. METHODOLOGY

A literature search was conducted to search for relevant institutions that have established a programme for incorporating professionalism in their medical schools. There was no attempt to review all published reports but to focus on the schools that can serve as models for other institutions in need of such curricular innovations. All information concerning the programmes were taken from the published journal articles which were authored by the faculty members in charge of the respective programmes on professionalism. An independent appraisal was done using a framework adopted from a systematic review by Passi and co-workers which included the following criteria: institutional definition of professionalism, curricular design, student selection, teaching and learning innovations, role modelling and assessment (Passi et al., 2010).

III. RESULTS

The review of literature on undergraduate medical programmes on professionalism revealed four notable models that describe how their institutions have integrated the teaching and assessment of professionalism among medical students, namely, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM), University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM), University of Queensland (UQ) School of Medicine, and Mayo Clinic School of Medicine.

A. Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM)

A model applied at the VUSM focused on an Academic Leadership Programme (ALP) established to address unprofessional and disruptive behaviours of students (Hickson et al., 2007). The ALP is a programme designed for leaders and administrators tasked to identify and tackle unprofessional behaviours. A four-level graduated intervention programme was designed to deal with the incident cases occurring in the school. The tenets of professionalism are introduced to the medical students through a discussion of case vignettes dealing with unprofessional behaviour. The faculty are also asked to sign a creed and a commitment to be role models of professional behaviour for graduates and medical students.

A so-called “disruptive behaviour pyramid” serves as a guide for identifying and assessing variable degrees of unprofessional behaviour with their corresponding intervention. Surveillance systems have also been put in place to detect unprofessional behaviour of students and physicians from patients, visitors, and health care team members (Hickson et al., 2007).

B. University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM)

The UWSOM introduced their professionalism curriculum through the development of the Colleges programme for the preclinical medical students. Outstanding faculty-clinicians are selected and trained to teach and model clinical skills with small groups of students at the bedside from the second-year level until the time of their graduation. The institution recognises these faculty as role model physicians working closely with students in the care of patients (Goldstein et al., 2006).

The school promotes an “ecology of professionalism” in the campus and provides an environment for group discussions, role modelling and reflection among the different year levels of medical education. Professionalism is an institution wide concern such that both students and the faculty are required to undergo training on professionalism. In order to make the programme more meaningful, the institution added the “Patients as Teachers” project whereby the patients are asked to provide feedback and to offer advice to the medical students. The loop of learning involving the faculty, the students, and the patient is deemed as a “safe” and respectful educational environment that encourages professionalism as an institutional-wide responsibility (Goldstein et al., 2006).

C. University of Queensland (UQ) School of Medicine

The programme of the University of Queensland integrates medical ethics, law and the professionalism curriculum with a “Personal and Professional Development” process (Parker et al., 2008). Throughout the four-year levels of undergraduate medical education, topics of ethics and professional development are taught and assessed through written tests and objective structured clinical examinations. A document called “Commitment to Professionalism” is signed by every student at the start of their first-year level to reinforce the principles and their acceptance of the expectations of the school, including attendance.

A “Pyramid of Professionalism” serves as a model to identify the students that require supervision and eventually pass or fail the programme. Students are assessed at several levels with a committee providing support, feedback and remediation. Professional conduct ultimately affects the student’s promotion to the next year level (Parker et al., 2008).

D. Mayo Clinic School of Medicine

The Mayo Clinic incorporated professionalism into medical education by first articulating its culture through a statement of the institution’s primary value: “The needs of the patient come first”. Their mission statement declares that “Mayo will provide the best care to every patient every day through integrated clinical practice, education, and research.” This culture is expressed in all the institution’s policies and procedures (Mueller, 2009).

Mayo has adopted a framework for professionalism which places clinical competence, communication skills and sound understanding of ethics at its foundation (Mueller, 2015). Built on this foundation are the pillars or the key attributes of accountability, altruism, excellence and humanism. With this framework and the culture that Mayo promotes, professionalism teaching and assessment programmes have been implemented involving all levels of learners of the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine. An intensive bioethics courses and a leadership and professionalism course is given to the first-year medical students. For the second-year level, the “Advance Doctoring” professionalism reflective writing programme is given. For the third-year level, the “Safe Harbor” professionalism programme and an intensive bioethics course is applied (Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015).

More professionalism and ethics teaching are incorporated into different courses and clinical rotations throughout the four-year curriculum. Other interesting features include an elective course in Professionalism and Ethics related to the students’ career interest. Professionalism assessments are carried out by way of formative and summative feedback and professionalism “portfolios” which are summarized for their future applications for further training (Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015).

The Mayo Clinic faculty physicians also have their share of professionalism modules. The new physician staff are required to attend a complete series of professionalism courses. All faculty physicians have to take a complete web-based, interactive module on professionalism in order to maintain their status as practicing physicians. They also undergo a 360-degree review to identify and address lapses in professionalism. The non-physician allied healthcare staff of the institution also have their own professionalism programme to support Mayo’s service philosophy (Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015).

The core value of professionalism continues to guide the clinic in its leadership practices and management strategies. The value-based culture serves as a positive hidden curriculum that promotes the achievement of desired educational outcomes among the health care professionals (Viggiano et al., 2007).

E. Institutional Definitions of Medical Professionalism

The lack of a universal definition of medical professionalism has resulted in medical schools formulating what is suitable to their context (O’Sullivan et al., 2012). Among the four curricular models, Mayo clearly expounded on their definition of medical professionalism. This institution defined professionalism by embracing seven patient care-related and seven practice environment-related attributes as summarised in the Mayo Clinic Model of Care (Mueller, 2009).

In the case of UQ, while no clear-cut definition of professionalism was described in the journal article, the institution instead presented a list of topics of medical ethics and professional development for formal training and instruction. A review of the UQ listing shows that most of the elements of professionalism covered were related to the theme of public or societal professionalism, such as Medical Practice and the Law, Accountability and Self-Regulation, Inappropriate Practice and Medical Over servicing, and Commercialization of Medicine (Parker et al., 2008).

A second list of elements of professionalism was prepared by the UQ faculty, and this list contained attributes related to intrapersonal and interpersonal professionalism. This list served as their guide to identify students who required support, feedback or remediation through the process called the Pyramid of Professionalism (Parker et al., 2008).

The VUSM also did not state the elements of professionalism in their model. Instead, the institution focused on defining the unprofessional or disruptive behaviours that required case discussions in particular year levels of medical education. These were the same unacceptable behaviours that were used to identify students who needed immediate intervention ranging from non-punitive interventions up to the imposition of disciplinary processes if needed (Hickson et al., 2007).

The UWSOM developed a list of elements of professionalism that served as benchmarks for preclinical students, namely, the principles of altruism, honour and integrity, compassion, communication, respect, accountability and responsibility, scholarship, excellence and leadership. Despite this listing, the faculty received feedback from the students that the idea of professionalism and cultural competency remained unclear to them. This feedback came with a request from the students that the teaching of professionalism should be “more specific, clinically relevant, and challenging” (Goldstein et al., 2006).

F. Comparison of Programme Implementation

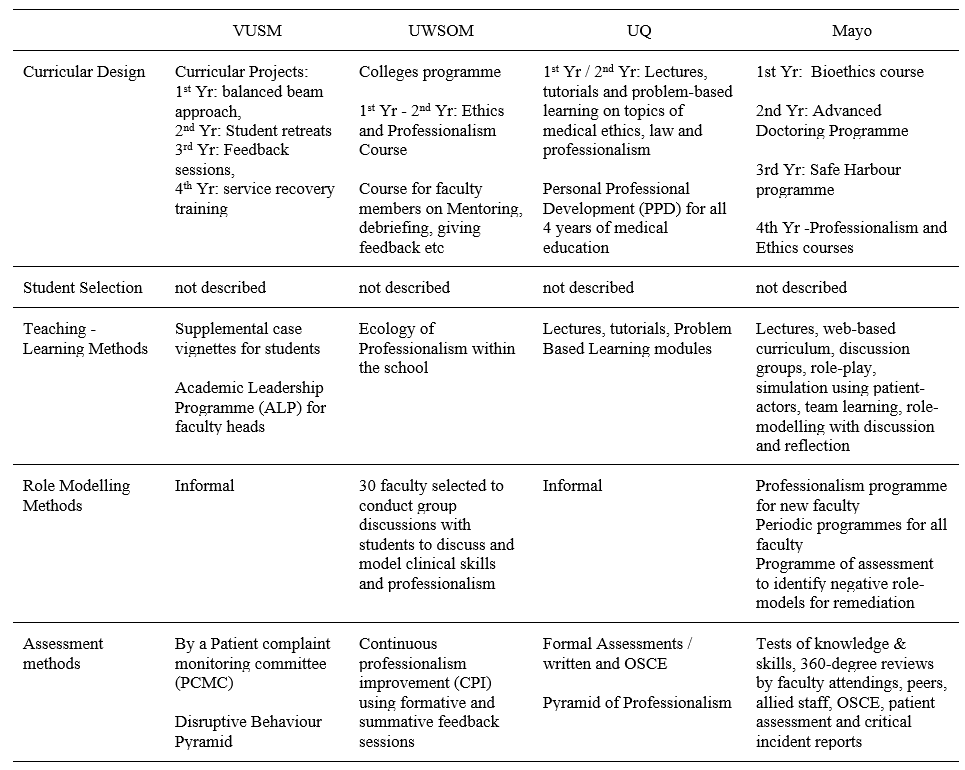

A systematic review (Passi et al., 2010) was done with the aim to summarise the evidence on methods used by medical schools to promote medical professionalism. Five main strategic areas to promote the development of professionalism in medical education were identified from the review: Curriculum design, student selection, teaching and learning methods, role modelling and assessment methods. These five areas can be used as guideposts in reviewing school programmes on professionalism. Table 1 shows a comparison of the four models presented earlier.

G. Similar Features in the Four Models

These are the features common to all four models: (1) Commitment of the leadership of the institution to embark on integrating professionalism into the curriculum, (2) Built-in programme for training of faculty for teaching and modelling of clinical skills, and (3) Vertical integration of the programme of professionalism from preclinical to clinical years.

These features are significant means to heighten the attention of both students and faculty to the need for growth in the area of professionalism. This will also help institutionalize professionalism. The journals on the models did not mention any policy regarding the screening for unprofessional behaviour during the student selection process.

H. Differences in the Four Models

Major differences are evident in the approach to teaching professionalism in the four curricular models.

1) The formal teaching and learning experience of the students of the four schools were varied in terms of duration and delivery of instruction: UWSOM and Mayo incorporates a formal course throughout the four years of medical education. In Mayo, all faculty physicians are trained and involved in the training of students for professionalism. UWSOM, on the other hand, has a select group of thirty faculty assigned for this purpose. UQ described a formal course on professionalism in the first two years of medical education. After the first 2 years, UQ proceeds to the clinical years of medical education using the personal and professional development (PPD) process of identifying personal and professional shortcomings among the students.

The approach taken by VUSM is more interventional in nature. Although short problem-based discussions are provided in the four-year levels of medical education, the main thrust of the programme is on identifying and rectifying incident cases of unprofessional behaviour. Its basis rests on the idea that “failing to address unprofessional behaviour simply promotes more of it.” The VUSM model mentions four graduated interventions as a disciplinary measure to address unprofessional behaviour.

2) The four schools also differed in their assessment methods: VUSM focuses on immediate recognition and grading using the “disruptive behaviour pyramid” to determine the appropriate intervention. UWSOM uses reflection and feedback in the preclinical years followed by a “closed loop” system of obtaining feedback from patients and faculty. Deficiencies in professional behaviour are identified so that remediation may be provided to ensure that only students who are ready will graduate or advance to the next year (Hickson et al., 2007).

(Goldstein et al., 2006; Hickson et al., 2007; Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015; Parker et al., 2008)Table 1. Comparative Summary of Four Models of Educational Programme for Teaching Medical Professionalism

UQ focuses more on written tests and objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE) in the preclinical years. Because the school recognises that these assessment methods may not necessarily measure actual attitudes, the personal and professional development (PPD) process serves as a means directed towards identifying students with problems who are then referred to a committee for support and remediation (Parker et al., 2008).

Mayo has a more comprehensive assessment method by including a 360-degree review from faculty attendings, peers, allied staff and patients to complement the written tests and OSCE (Mueller, 2009).

3) Role modelling: On the area of role modelling, UWSOM has developed a formal programme to train select faculty members to promote role modelling as a means of teaching students. The programme to promote an “ecology of professionalism” within the institution is unique to UWSOM. This is the school’s way of making professionalism an institution-wide responsibility and yet maintains a “safe” educational environment for learning and improvement (Goldstein et al., 2006).

Mayo, on the other hand, has required all faculty and staff physicians to attend and successfully complete a series of modules on professionalism, physician-patient communication, self-awareness, and diversity. Maintaining the culture of professionalism in the Mayo Clinic is a result of a continuing process of allowing ethics and professionalism to be woven into the courses and clinical rotations (Mueller, 2009).

I. Professionalism in Medical Education in the Future

Much progress has been attained in the last decade when various models for incorporating professionalism in medical education have been disseminated in various journals. The Bioethics Core Curriculum introduced by the UNESCO also declared that bioethical principles and human rights must be taught early to medical students and that Medical Ethics, which is a branch of Bioethics, must be taught in all levels of education (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2008).

The Medical Ethics Manual released by the World Medical Association (WMA) provided a basic and universally used curriculum for the teaching of medical ethics. The WMA curriculum includes professionalism as a key component needed for the inclusion of Medical Ethics and Human Rights as an obligatory course for medical schools worldwide (Williams, 2015).

It has been observed that professionalism taught through time-based training might not be sufficient to address the changing healthcare environment and new learners. For the current generation of learners, specialty training must now be aligned with global standards such as that of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The ACGME standards incorporates professionalism and system-based practice as core components of the curriculum that begins with acquisition of medical knowledge and clinical skills.

Moving forward to the future necessitates the development of methods of assessment of professionalism as a means to successfully teach these professional behaviours (Chay, 2019).

Another key step in the future includes the teaching of professionalism as part of health professions education. Future academic health centres will need more medical educators who can pursue further education and help foster an environment that supports educator development. This key step will help in the attainment of long-term goals and to adapt to the changes in medical education (Dickinson et al., 2020).

Providing doctors with professional models as they move from novice to expert in their professional career will be instrumental as a framework for education. One clear example is the professional identity model that incorporated leadership, followership and team-working roles A more rounded and mature professional identity eventually develops that would set these doctors as models of professionalism for other health workers (McKimm et al., 2017).

IV. CONCLUSION

The unresolved definition of medical professionalism has made the incorporation of programmes on professionalism quite challenging. Any programme that will be implemented must be well thought of and tailored to the needs of the institution and all stakeholders. Analysing unique contexts of the curricular programme will be the key to keep any programme on professionalism relevant and viable.

The fact is that there are few curricular models for the incorporation of medical professionalism into the medical curriculum. This process is not an easy task and needs a strong institutional commitment and resolve for it to be successfully implemented. The four models were amazing attempts to incorporate professionalism in medical education. No formal evaluation has been published concerning this. Based on the comparative analysis of the four models, certain aspects should be highlighted so that we could possibly learn from them:

1. The task of preparing a programme on medical professionalism would be more systematic if the institution starts with a working definition of professionalism. This was seen in Mayo where a well-described definition set the direction for planning, implementing and institutionalising professionalism.

2. The culture of professionalism needs to be articulated institutionally and incorporated in the institution’s vision, mission, goals and policies. Mayo’s declaration of its primary value that “the needs of the patient come first” sets the stage for an atmosphere that is conducive to serving with professionalism.

UWSOM also opened its door to a culture of professionalism by declaring an “ecology of professionalism”. However, its implementation may have been limited when the Colleges programme for the purpose of institutionalising professionalism was limited to thirty designated faculty and role models.

3. The professionalism programme must be woven in all levels of medical education from the pre-clinical to the clinical years. Just like any competency, acquiring the values and skills and putting it into practice requires constant learning and reinforcement throughout the years of education.

Mayo and VUSM have prepared programmes for all the four years of medical education. Both institutions have crafted programmes for the pre-clinical years and have provided teaching and learning activities such as lectures, problem-based learning, small group discussions and feedback. Mayo engaged their students in the clinical years in elective experiences in professionalism and ethics and a “professionalism portfolio” for all students. VUSM designed a programme for the clinical year that was limited to a service recovery training for the purpose of addressing actual patient complaints.

4. Role models are essential in teaching professionalism because they can greatly influence attitudes and behaviours. Unprofessional physician behaviours such as disrespect and abuse of medical personnel, and refusal to complete duties must be corrected. If left unchecked, the observing medical students may consider such behaviours as normal (Mueller, 2009). These are among the ill effects of a hidden curriculum that occurs when an institution lacks role models. For a programme on professionalism to be successful, the faculty physicians and the rest of the healthcare team and institution’s staff need to undergo professionalism programmes applicable to their needs and roles.

In the case of UWSOM, a group of 30 selected faculty underwent training while in Mayo, all faculty underwent a professionalism programme.

5. Based on the curricular models described, it appears that a nurturing environment is preferable over punitive actions. The development of all scopes of professionalism from the intrapersonal to interpersonal to societal professionalism requires constant discussion, feedback and remediation. Although repetitive unprofessional behaviours may have consequences, the medical trainee will need to go through the nurturing process in order to fully imbibe the heart and soul of a medical professional.

6. The ability to handle professionalism challenges follows a learning curve as well. The levels of difficulty of professionalism challenges are related to how much learning situations a student may have encountered. The goal is to move from novice to competent to proficient and hopefully to an expert level of handling professionalism challenges just like all other aspects of learning in medicine.

The ability of the future generation of physicians to serve society ultimately rests on how professionalism has been woven into the curriculum in medical education. How to incorporate professionalism will be a continuing challenge for all medical educators.

Note on Contributor

Dr. Maria Isabel M. Atienza, Professor, San Beda University College of Medicine, Philippines and Head, Institute of Pediatrics & Child Health, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Global City developed the methodological framework for the study and performed data collection and data analysis as part of her PhD research, and wrote and approved the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This review article was not submitted for IRB/ethical approval.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the insightful suggestions of the Vice Dean of San Beda University College of Medicine: Dr Noel Atienza.

Funding

This review article did not receive any funding.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Chay, O. M. (2019). Transformation of medical education over the years – A personal view. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 4(1), 59-61. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2019-4-1/pv1076

Cruess, R. L., & Cruess, S. R. (2006). Teaching professionalism: General principles. Medical Teacher, 28(3), 205-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600643653

Dickinson, B. L., Chen, Z. X., & Haramati, A. (2020). Supporting medical science educators: A matter of self-esteem, identity, and promotion opportunities. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(3), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2020-5-3/pv2164

Goldstein, E. A., Maestas, R. R., Fryer-Edwards, K., Wenrich, M. D., Oelschlager, A.-M. A., Baernstein, A., & Kimball, H. R. (2006). Professionalism in medical education: An institutional challenge. Academic Medicine, 81(10), 871-876. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.acm.0000238199.37217.68

Hickson, G. B., Pichert, J. W., Webb, L. E., & Gabbe, S. G. (2007). A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: Identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Academic Medicine, 82(11), 1040-1048. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3185761ee

Lynch, D. C., Surdyk, P. M., & Eiser, A. R. (2004). Assessing professionalism: A review of literature. Medical Teacher, 26(4), 366-373. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001696434

McKimm, J., Vogan, C., & Mannion, H. (2017). Implicit leadership theories and followership informs understanding of doctors’ professional identity formation: A new model. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 2(2), 18-23. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2017-2-2/oa1022

Mueller, P. S. (2009). Incorporating professionalism into medical education: The Mayo clinic experience. The Keio Journal of Medicine, 58(3), 133-143. https://doi.org/10.2302/kjm.58.133

Mueller, P. S. (2015). Teaching and assessing professionalism in medical learners and practicing physicians. Ramban Maimonides Medical Journal, 6(2), e0011. https://doi.org/10.5041/rmmj.10195

O’Sullivan, H., van Mook, W., Fewtrell, R., & Wass, V. (2012). Integrating professionalism into the curriculum. Medical Teacher, 34(2), 155-157. https://doi.org/10/3109/0142159x.2011.595600

Parker, M., Luke, H., Zhang, J., Wilkinson, D., Peterson, R., & Ozolins, I. (2008). The pyramid of professionalism: Seven years of experience with an integrated program of teaching, developing, and assessing professionalism among medical students. Academic Medicine, 83(8), 733–741. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31817ec5e4

Passi, V., Doug, M., Peile, E., Thistlewaite, J., & Johnson, N. (2010). Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Education, 1, 19-29. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4bda.ca2a

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2008). Bioethics core curriculum. Syllabus section 1: Ethics education programme. UNESCO. http://www.unesco-chair-bioethics.org/?mbt_book=bioethics-core-curriculum

Viggiano, T. R., Pawlina, W., Lindor, K. D., Olsen, K. D., & Cortese, D. A. (2007). Putting the needs of the patient first: Mayo clinic’s core value, institutional culture, and professionalism covenant. Academic Medicine, 82(11), 1089-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181575dcd

Williams, J. R. (2015). Medical ethics manual (3rd ed.). World Medical Association. https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/education/medical-ethics-manual/

*Maria Isabel Maniego Atienza

San Beda University

College of Medicine,

Mendiola Street,

City of Manila,

Philippines 1005

Tel: 6329178668751

Email: mmatienza@sanbeda.edu.ph

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.