Case write-ups and reflective journal writing in early clinical years – Have these been “worthy” educational tools?

Submitted: 16 December 2022

Accepted: 25 June 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 6-13

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/OA2928

Pooja Sachdeva & Derrick Chen-Wee Aw

Department of General Medicine, Sengkang General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Case write-ups and reflective journals have been used as assessment tools of learning in clinical rotations in Yong Loo Lin school of medicine. It is timely to review the current process of conducting these assessments and effectiveness as an assessment tool. This study aims to understand faculty outlook towards these assessments.

Methods: This is a study that involves a survey-based questionnaire with both closed and open-ended questions, sent out to faculty marking the students’ assignments. This survey was anonymous & voluntary and was disseminated by administrative assistants. The purpose of this survey was to collect the feedback from faculty about current process with intentions of improving the effectiveness of these assessments. The suggestions for improvement were incorporated in the survey and faculty was invited to comment over these suggestions and provide further suggestions if any.

Results: Fifty-two responses from faculty were collected and analysed. Ninety percent of respondents thinks that this is an effective tool to assess and promote self-directed learning. Qualitative feedback was received about need of improvement in a) alignment of the submissions timings with rotation postings b) marking rubric to incorporate factors such as case complexity and weightage to different components of case write-ups, c) timely feedback to students, and d) follow up on action plans.

Conclusion: Case write-ups and reflective journals are still effective learning and assessment tools. They promote self-directed learning and clinical analysis in students. Feedback and action plans are the backbone of these assessments and optimal utilisation of these is recommended.

Keywords: Undergraduate Medical Education, Case Write-ups, Medical Assessments, Reflective Journals

Practice Highlights

- Case write-ups promote critical analysis & clinical judgement and reflection develops metacognition.

- Students should be guided and encouraged to choose cases to promote self-directed learning.

- Marking rubrics need revising and faculty development on how to utilise them.

- Timing of submission needs to be improved to facilitate feedback and follow-up.

- Direct and timely feedback to students and follow up on actions plans improve utility.

I. INTRODUCTION

The medical curriculum has many assessments designed over professional years to assess the knowledge and competence of medical students such as OSCE, Mini CEX, Case write ups, Reflective Journals, multiple choice questions (MCQs), portfolios etc (Miller, 1990). Few assessments such as Mini-CEX and OSCE have gained popularity over last few decades as there is robust evidence in support of these assessments as a tool to promote and assess students’ learning. Patrício et al. (2013) and Mortaz Hejri et al. (2020) have explored the utility of OSCE and Mini CEX respectively in undergraduate & postgraduate education and concluded that reliability, flexibility, and validity of these assessments are the strengths that make them widely acceptable. With growing research in field of medical education assessments, it is important and wisely to seek understanding of current written assessments such as case write-ups and reflective journals in terms of their effectiveness and processes in conducting them. McLeod (1989) surveyed the students and faculty about the effectiveness of case write-ups and written assignments in the undergraduate medical curriculum. There was broader agreement among students and faculty that these assessments were useful educational tools, however, there were concerns about the variability of marking criteria and standard of evaluation (Fortson A, (n.d.); Larsen et al., 2016). Over the years, these assessments have been standardised by using an assessment template that guides the students and marking rubric to assist assessors to mark students to reduce interrater variability (McGlade et al., 2012; McLeod, 1987).

Written assignments on patient cases in which a student had participated in clinical care have been a de rigueur component of posting assessments in the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, the National University of Singapore (NUS) for decades. Although the assessment template and marking rubrics have evolved through the years, their objectives have remained unchanged: to encourage deep analysis and reflection on the medical and biopsychosocial aspects of a patient’s clinical problems, investigations, and management; to promote self-directed learning on knowledge gaps, and to enhance confidence in clinical reasoning and practical approaches. Tutors benefit by gaining greater insight into their student’s learning experiences and the effectiveness of their clinical teaching. By providing timely interventions with feedback, tutors promote learning and reflection and contribute to the summative evaluation of the posting. In recent years, tutors are required to provide written feedback to students.

Throughout the years, informal feedback on the value of such written assignments has been sporadically provided by students in their end-of-posting comments, and periodically gathered from teachers at annual get-together discussions. An internal audit was conducted via a formal survey for tutors and students in 2012-13 concerning the learning value and feasibility within a year of launching the latest iteration of these written assignments. Overall sentiments were mixed from both faculty and students regarding its utility and effectiveness as a learning exercise. Therefore, it is time to perform an evaluation to determine if these written assignments should continue as usual or be refined to better reflect the program objectives as well as the requirements of a good clinical assessment.

II. BACKGROUND

Phase three medical students from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine in their Medicine rotations in various healthcare institutions are required to submit one outpatient case write-up and two inpatient reflective journals at the sixth to eighth weeks of their 12-week posting. The assessment is standardised as submission needs to follow a format as per assessment template with each component carrying a certain weightage. A marking rubric is also designed to guide the assessor to mark students to make it objective, reliable, and reproducible. The core tutors will mark and provide written feedback on these submissions based on a rubric provided by the school. Face-to-face feedback is encouraged but not mandated. The scores of these written assignments form 30% of the overall posting assessment, and the latter contributes a maximum of 9.4% to the final phase 3 MBBS examination.

Our study was conducted to identify faculty’s viewpoint toward these written assignments as an assessment tool and if it is being conducted in a manner where it promotes learning. Constructive feedback was also collected to seek ways to improve this further. A questionnaire, including mostly closed-end questions with recommended suggestions for improvements with some open-ended questions was prepared and disseminated to faculty through administrative support. The results of this questionnaire are discussed in this paper.

III. METHODS

In this study, we prepared a knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) questionnaire for faculty assessing students’ assignments. The faculty constituted associate consultants and above in public institutions in Singapore who have tutored the students in Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine in their clinical rotations and have marked their written assessments. There were no inclusion criteria, hence all faculty members who have tutored the students and have marked these assessments were invited to answer this survey. The survey was sent out through administrative assistants in respective departments of public institutions for ease of dissemination and to avoid pressurising the participants. The responses from faculty who have not marked these assessments were not counted towards final analysis. The author aimed to collect constructive feedback from faculty about the current process and suggestions for improvement in this assessment tool. The study was conducted over a period of three months from Sep 2020 to Dec 2020 in Singapore for Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

The questionnaire was anonymous, and it included eighteen questions, designed to understand the strengths and limitations of these case write-ups and reflective journals based on the Context, Input, Process, and Product (CIPP) method of program evaluation, developed by Stufflebeam (2002) with the aim of providing suggestions for improvement in current delivery or content. The questions included objectives of these assessments, frequency, process, and standardisation training for marking them. It also included the questions regarding familiarity of faculty with these assessments in terms of numbers of these assessments marked per year, marking rubrics and their expectations from the students. Lastly, there were open ended questions regarding feedback for improving the current process and strengthening these assessments for serving the purpose of assessment of students’ learning. An implied consent was obtained from study participants as questionnaire was voluntarily answered. The responses to this survey were collected, collated, and analysed for the understanding of faculty viewpoint and outlook towards these assessments. Feedback was analysed and recommendations were formulated to improve current process of these assessments.

IV. RESULTS

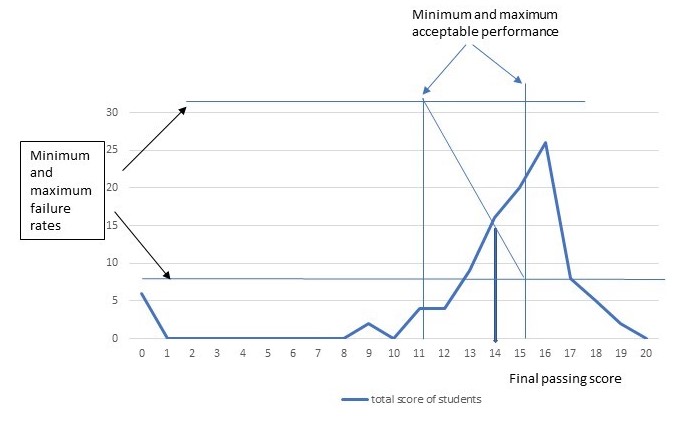

The survey was disseminated to 150 faculty members, and it collected a total of 52 responses (n=52) from two public health clusters over a period of three months with a response rate of 34%. The survey was sent out in September 2020 and monthly reminders were sent till December 2020. The faculty who marked at least one assignment was offered to participate, but there was low response rate, due to lack of inducement or survey fatigue. About 88% (n=46) of respondents had marked 2 to 6 assignments in an academic year while 4% (n=2) had marked more than 10. Ninety percent (90%) (n=47) of faculty think that these written assignments are tools to promote and assess learning. Factors that make them useful were the opportunity for students to choose their cases in outpatient and inpatient settings thus, promoting self-directed learning (29%, n=15) and for assessors to provide feedback and an action plan (30%, n=16). Although when approached by students for a choice of cases, faculty mostly assigned the cases themselves (56%, n=29). The complexity of the selected case (47%, n=24) and common vs uncommon case (30%, n=16) were the principal factors that influenced the marking by assessors. The discussion and reflection sections in these write-ups provided insight into students’ understanding of the case that influenced the overall passing scores (12%, n=6). Marking rubric provided to faculty was used only about half of the time (48%, n=25) faculty used the rubric. Of the 48% (n=25) of assessors who used rubrics for marking, most of them found the rubric to be user-friendly (40%, n=10). Although the same write-up assessment is used to assess learning at distinct phases of the MBBS curriculum (Phase III and Phase IV), 89%, (n=46) of assessors marked it against the expected level of students’ training.

While 60% (n=31) of the assessors provided the overall score, feedback, and action plans directly to the students, either in personal meetings or by email or phone, 40% (n=20) handed over the assessment to an educational administrative assistant. Faculty in the survey responded that face-to-face meetings provided “clearer discussion” and “personal engagement with the student” and were “faster and more effective,” yet the organisation such as “timing of submission mostly at the end of the posting” or “busy schedules of both assessors and students” made it harder to meet students personally. Most of the assessors (69%, n=36) provided action plans which included looking up literature for deeper learning and similar case review for expanding understanding of the patient’s presentation. In a few instances, it also involved rewriting of write-ups (11%, n=5). However, these actions were not followed up very actively. Only a few assessors (10%, n=5) made phone calls or emailed the students to follow up.

Faculty feedback was sought about improvement in the current Input and Process of these assessments. 40% (n=20) of faculty think that weightage to the different components of these write-ups should be flexible and adjusted. 53% (n=28) of assessors suggested that analysis of the case with clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis should bear higher weightage than the clinical presentation, management, or student’s reflection. The number of submissions (16%, n=8) and timing of submissions during a rotation (22%, n=11) should be made uniform and aligned with the training weeks so that timely and face-to-face feedback can be arranged. In our survey, 40 % (n=20) of faculty’s feedback was a written statement to the educational administration. The results of the study are in the data repository and can be accessed by readers if they wish to see detailed responses from faculty in Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24471661.v1 (Sachdeva & Aw, 2023).

V. DISCUSSION

Clinical rotations are the placements planned by universities for medical students to have real-time patient encounters in public hospitals. This is the continuation of the undergraduate medical education curriculum whereby students learn to apply their medical knowledge acquired in initial foundation years and continue to learn bedside manners, verbal and nonverbal communication, eye contact, and body language to prepare them for their future roles as doctors.

Assessments during these rotations must include all the areas of learning such as the patient’s clinical presentation, diagnostic approach for the patient’s symptoms, the analytic ability of students, and communication with the patient and his management. A variety of assessment tools to perform a comprehensive holistic evaluation of a student’s performance are undertaken in clinical rotations such as Mini CEX, Case logbooks, student portfolios, and written assignments such as case write-ups and reflective journals. While Mini CEX has gained its popularity over last few decades due to its rapid results, synchronous feedback and direct observation of encounter, other assessments such as case write-ups, reflective journals do contribute to learning and supplements the medical education assessments and have been the part of curriculum.

Assessments such as Mini-CEX (clinical encounter) are assessor-observed case presentations that assess the student’s ability to ask history questions and perform a clinical examination to formulate a list of differentials and thus develop a diagnostic approach (Kogan et al., 2002). It also assesses skills such as bedside manners, verbal and nonverbal communication, use of jargon, and speed of speech. There is a provision for giving feedback to the students about their learning and agreeing on an action plan to improve upon the student’s learning gaps at the end of the encounter. This assessment does not provide the opportunity for reflection-on-action and in-depth patient management (Schon, 1984).

Case write-ups on the other hand are akin to a case presentation but the focus is on identifying knowledge gaps by students themselves. Students collect data on patients’ clinical presentation and investigations performed that help in formulating a diagnostic plan (McLeod, 1989). They analyse the information to reach a final diagnosis. Students refer to literature for common and uncommon presentations of the patient’s condition and learn management based on the evidence. It also provides the opportunity to learn details about a certain medical disease. However, this literature then needs to be individualised for the patient based on his comorbidities and social factors. In the end, students are asked to submit this write-up along with their reflections on their learning from the patient and assessment.

Reflective journals are like case write-ups however, the emphasis is on learning and evolution alongside the clinical encounter. Boyd & Fales (1983) have explained reflective writing as an internal experience that is triggered by an encounter which results in changed perspective. Students are expected to write about the patient encounter, their interpretation about clinical outcome and management and their learning along the encounter as per stages in cycle of reflection (Gibbs, 1998). Mello & Wattret (2021) highlighted reflection as a skill that prepares students for lifelong learning.

|

Assessment |

Mini CEX |

Case write-ups and reflective Journals |

|

Directly observed |

Yes |

No |

|

Case presentation and differentials |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Access to investigations |

Provided by accessor on request |

Access is granted |

|

Management plan |

Proposed by learner |

Assessed and discussed by learner |

|

Reflection-in-action |

Yes |

No |

|

Reflection-on action |

No |

Yes |

|

Literature review |

No |

Yes |

|

Feedback to learners |

Yes, communicated directly at end of encounter |

Yes, communicated directly or indirectly* |

|

Action Plan |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Resources required |

The patient, learner and accessor must be present at same time (synchronous learning) (Kunin et al., 2014) |

The patient, learner and accessor need not be present at same time (asynchronous learning) (Kunin et al., 2014) |

|

Assessment focus |

Communication skills, bedside manners, professionalism, case presentation and diagnosis and approach to diagnosis (Kogan et al., 2002) |

Clinical reasoning, in depth understanding of disease presentation, Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) practice and learner’s reflection (McLeod, 1989). Reflective journals focus more on learning evolution based on one’s experience. |

|

Marking |

More objective (valid, reproducible) |

More subjective (assessor guided) ** |

|

Assessment tool |

Formative (Joshi et al., 2017) |

Summative (Bussard, 2015) |

Table 1. Comparison of Mini CEX and case write-ups as assessment tools

*For direct feedback, assessor needs to have follow up communication with the student.

**it can be made objective with descriptors provided in the, marking template for each domain that is being assessed.

Evidence has shown that case write-ups do provide assessors the ability to understand students’ learning and analytical skill (McLeod, 1989) and unlike Mini CEX, it involves reflections by students that deepen learning and memory (Fortson & Sisk, 2007). Similarly, Bjerkvik & Hilli (2019) emphasised that reflective journals promote deeper understanding, critical analysis, metacognition and promotes self-development. Onishi (2008) noted that case presentations during clinical rotations promote the assessor’s understanding of student learning which is consistent with our faculty response as most of our faculty (n=47, 90%) agree that case write-ups are important tools to assess learning. However, since these are not observed assessments at the bedside and require submission, there is no face-to-face contact with the student to give instant feedback and discuss action plans, if any. The discussion of feedback and action plan requires separate communication such as a meeting or phone calls or emails between the assessor and student. If appropriate feedback is not provided or communicated, it is a lost opportunity for improvement in students’ learning.

Results from our survey have highlighted a few areas that needed the attention in optimal utilisation of these assessments. First is, the choice of cases, either by faculty or by students is not uniform. The case selection by students promotes self-directed learning. Presently, students are given a list of cases that may help them select one, but the enlisted cases may not be encountered during their rotation. In such situations, faculty suggesting the choice of cases can provide directions to students. Lee et al. (2010) demonstrated that students who were encouraged to choose their cases based on their knowledge gaps, learning strategies, and study time, were more inclined towards self-directed learning. Self-directed learning has been a cornerstone of adult learning, and it provides learners autonomy and control over their learning and prepares them for lifelong self-management outside educational institutions (Goldman, 2009; Lee et al., 2010). Understandably, students’ choice of cases is influenced by the curriculum, tutorials, and objectives of a particular rotation. Case write-ups and Reflective Journals in our context included both inpatient and outpatient encounters hence providing the choice for both acutely sick vs stable chronic patients. Since the students were encouraged to choose their cases for these assessments on their own, it provided them the opportunity to meet their personal goals and learning deficits. However, if asked for guidance, slightly more than half the faculty (56%, n=29) would assign the cases themselves, and of note, such selection of cases, in various forms of frequency and complexity, did affect the marking by faculty by a considerable amount (about 30 to 45%). Nonetheless, the reflective journals involve writing about one’s learning evolution about a case from preset knowledge to acquired knowledge after encounter. Hence, both these written assignments, case write-ups and reflective journals on any encounter tend to improve learning by making students do literature search and individualise this current evidence-based management search in context of the chosen patient. It still serves the purpose of learning, although personal selection of patients encourages students to work on their own interest, at their own pace and promotes deeper understanding tailored to one’s own pre-existing gaps or deficiencies in knowledge. The authors think that faculty assigning cases will inadvertently compromise the extent of self-directed learning to a significant degree and adjusting the marking based on the frequency and complexity is a qualitative component that warrants further investigation. We recommend the school generate a simple set of guidelines to help students to make an informed and wise selection of suitable cases for their written assignments. Focus group discussions with tutors who regularly mark students on such assignments may provide useful directions in the guidelines’ construction.

Results of this survey also raised the inconsistency in faculty use of marking rubrics. McLeod (1989) raised the major concerns about the variability of criteria and standards of evaluation of these written assessments.

Kogan & Shea (2003) addressed these concerns and assessed the evaluation of write-ups against a pre-set evaluation form that increased the validity and reliability of scoring these write ups. Peggy (2014) also highlighted the use of standardised scoring rubric for case write-ups to reduce the interrater variability and improve the reliability of these assessments. Hence, the scoring rubrics must have descriptors for faculty to mark the students against their performances and it not only makes the assessment fair, but also contributes to individualised and appropriate feedback for students for further improvement in respective domains (Cyr et al., 2014; Kogan & Shea, 2005). Thus, the author recommends that universities or schools must emphasise on faculty training and thereby its use in marking these assignments.

This also brought about the feedback, provided by faculty in this survey about components of this rubric. Reflective journals and case reports assess similar yet different components of learning. While case reports accounts more for critical analysis, clinical judgement, evidence-based management for a particular patient, the reflective journals assess the student’s ability to assimilate an encounter with new acquired knowledge and reflect on their individual learning and growth (Sandars, 2009). Hence, rubric should be tailored to these assessments’ subcomponents accordingly. A small fraction of faculty (12%, n=6) in our survey responded that the discussion and analysis of information by students influenced their marking of the write-up as it provided them invaluable insight into students’ clinical reasoning. In line with this, half of the faculty (53%, n=27) recommended that analytic skills be ranked higher in weightage as compared to data collection on patient history and examination. Hence, marking rubric should emphasise more on clinical judgement and critical analysis in case write-ups than components such as history taking and examination as latter can be assessed in detail with other assessments such as Mini CEX or OSCE examinations. At the same time, complexity of the case and atypical presentation must also account for separate marks to encourage students for choosing challenging and difficult cases. Similarly, for reflective journals rubrics must have weightage on self-reflection cycle, changes in attitudes and perception and how the encounters have changed one’s learning and future practice. The role of rubric in standardisation of these written assessments is paramount as former provides a structure of written submissions for students and reliable and valid scoring tool for faculty.

Results of our survey also highlighted pertinent inadequacy in these assessments that is inability to provide the face-to-face feedback to the students in timely fashion, contributed by timing of submissions of these assessments towards the end of rotation. There is ample literature to support that feedback is a backbone of any formative assessment (Clynes & Raftery, 2008; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006) as it promotes self-regulation of training and highlights the discrepancies in the trainee’s current vs expected learning outcome. Hence like every other assessment, the templates of case write-ups are imbued with spaces for feedback and action plans which the majority of faculty (60%, n=31) have personally communicated to the students. Face-to-face feedback has a higher impact on performance improvement than written indirectly communicated or no feedback as the former provides two-way engagement, however, this impact depends upon the supervisor’s training and content & organisation of feedback (Johnson et al., 2020; Pelgrim et al., 2012). The final stage of providing any feedback as per Pendleton’s rule (Pendleton, 1984). Pendleton’s rule is an agreement between the learner and assessor for a joint action plan for improvement. Presently, there is no timeline for students to submit these written assignments to their core supervisor, hence if these are submitted towards the end of the rotation, the opportunity for face-to-face feedback and discussion on action plans is underutilised. Hence, it would be worthwhile to align the submission with weeks of rotation so that timely and personal feedback can be provided and agreed action plans can be followed within the rotation.

This study highlighted that though an action plan was agreed upon, it was not actively followed up with students 90% (n=47) of the time – as such, the accountability of this assessment is reduced. The most common reason for the inability to follow up on action plans was coordination (having to schedule a meeting between the assessor and student when the student may have moved on to the next rotation). This can be modified if students are instructed to submit their assignments at least one or two weeks before the end of posting to allow ample time for both parties to schedule a meet-up. Alternatively, there could be an end-of-posting mandatory meet-up with the clinical supervisor to provide overall feedback for rotation and to discuss action plans. Additionally, the school could also mandate a follow-up meeting, over an interactive online platform if a face-to-face meeting is not feasible, for a supervisor to review the outcomes of the actions undertaken by the student. The school may even consider recruiting student mentors to follow up instead.

Overall, this survey has provided useful insight into these assessments’ conduct and has highlighted the factors that limit the utility of these written assessments. With the faculty agreeing that these assessments are still worthy educational and learning assessment tools, there is a need to improve marking standardisation of these assessments and like other assessments, formative feedback to students on gaps in knowledge must be provided. These assessments have been part of curriculum for decades and their role in students learning must be utilised to its full potential.

There are limitations in our study such as lower number of respondents and qualitative feedback. As survey is voluntary and anonymous, it is limited in its research capability for recommendations and qualitative feedback as latter is respondent dependent. Hence, further qualitative research such as focussed group discussions is required to understand the ways, these assessments can be utilised to their full potential as learning and assessment tools.

VI. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, written assignments are still worthy and useful tools to assess the learning of students during clinical rotations. It promotes self-directed learning by allowing students to select their case and provides the opportunity for the assessor to assess the knowledge gaps of students about case management. Since the case choice affects the marking by the assessor, authors recommend that students are given free reign, within a set of recommended guidelines.

Marking and scoring should be adjusted to include variables such as case selection and complexity in the marking rubric provided to the assessors, hence authors also recommend updating marking rubrics in consultation with faculty, with subsequent faculty development for compulsory use of this rubric.

For these assessments to be more effective, structured, timely and direct feedback should be given to students with action plans that must be followed. The hurdles in following up on action plans such as change of rotations can be dealt with by adjusting the timing of submission of these assessments during a posting and creating opportunities for follow-up. Hence, authors also recommend face-to-face feedback by ensuring adequate timing of assessments and appropriate follow up for action plans to maximise educational improvement opportunities.

Notes on Contributors

Dr. Pooja Sachdeva has contributed to the conceptual development of this study, survey questionnaire development, dissemination of the survey to faculty, data collection, and analysis. This manuscript has been written, read, and finally approved by her.

Dr. Derrick Aw has contributed to the conceptual development of this study, survey questionnaire development, and student and faculty engagement. This manuscript was read, edited, and finally approved by him.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Singhealth Institutional Review Board (IRB) with reference no 2020/2688.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24471661.v1 (Sachdeva & Aw, 2023).

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the contributions of Dr Shweta Rajkumar Singh for editing the final manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding received for the study.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

Bjerkvik, L. K., & Hilli, Y. (2019). Reflective writing in undergraduate clinical nursing education: A literature review. Nurse Education in Practice, 35, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.11.013

Boyd, E. M., & Fales, A. W. (1983). Reflective learning: Key to learning from experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 23(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167883232011

Bussard, M. E. (2015). Clinical judgment in reflective journals of prelicensure nursing students. The Journal of Nursing Education, 54(1), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20141224-05

Clynes, M., & Raftery, S. (2008). Feedback: An essential element of student learning in clinical practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 8(6), 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2008.02.003

Cyr, P. R., Smith, K. A., Broyles, I. L., & Holt, C. T. (2014). Developing, evaluating and validating a scoring rubric for written case reports. International Journal of Medical Education, 5, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.52c6.d7ef

Fortson, A. (n.d.). Reflective journaling as assessment and teaching. http://www.reap.ac.uk

Gibbs, G. (1998). Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford Brookes University.

Goldman, S. (2009). The educational kanban: Promoting effective self-directed adult learning in medical education. Academic Medicine, 84(7), 927–934. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a8177b

Johnson, C. E., Weerasuria, M. P., & Keating, J. L. (2020). Effect of face-to-face verbal feedback compared with no or alternative feedback on the objective workplace task performance of health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 10(3), e030672. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030672

Joshi, M., Singh, T., & Badyal, D. (2017). Acceptability and feasibility of mini-clinical evaluation exercise as a formative assessment tool for workplace-based assessment for surgical postgraduate students. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 63(2), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.4103/0022-3859.201411

Kogan, J. R., Bellini, L. M., & Shea, J. A. (2002). Implementation of the mini-CEX to evaluate medical students’ clinical skills. Academic Medicine, 77(11), 1156–1157. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200211000-00021

Kogan, J. R., & Shea, J. A. (2003). An assessment measure to evaluate case write-ups in a medicine core clerkship. Medical Education, 37(11), 1035–1036. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01660.x

Kogan, J. R., & Shea, J. A. (2005). Psychometric characteristics of a write-up assessment form in a medicine core clerkship. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 17(2), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1702_2

Kunin, M., Julliard, K. N., & Rodriguez, T. E. (2014). Comparing face-to-face, synchronous, and asynchronous learning: Postgraduate dental resident preferences. Journal of Dental Education, 78(6), 856–866.

Larsen, D. P., London, D. A., & Emke, A. R. (2016). Using reflection to influence practice: Student perceptions of daily reflection in clinical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 5(5), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-016-0293-1

Lee, Y.-M., Mann, K. V., & Frank, B. W. (2010). What drives students’ self-directed learning in a hybrid PBL curriculum. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 15(3), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-009-9210-2

McGlade, K., Cargo, C., Fogarty, D., Boohan, M., & McMullin, M. (2012). Handwritten undergraduate case reports. The Clinical Teacher, 9(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2011.00494.x

McLeod, P. J. (1987). Faculty assessments of case reports of medical students. Journal of Medical Education, 62(8), 673–677. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198708000-00008

McLeod, P. J. (1989). Assessing the value of student case write-ups and write-up evaluations. Academic Medicine, 64(5), 273–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198905000-00016

Mello, L. V., & Wattret, G. (2021). Developing transferable skills through embedding reflection in the science curriculum. Biophysical Reviews, 13(6), 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-021-00852-3

Miller, G. E. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine, 65(9), S63.

Mortaz Hejri, S., Jalili, M., Masoomi, R., Shirazi, M., Nedjat, S., & Norcini, J. (2020). The utility of mini-clinical evaluation exercise in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education: A BEME review: BEME Guide No. 59. Medical Teacher, 42(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1652732

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Onishi, H. (2008). The role of case presentation for teaching and learning activities. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 24(7), 356–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70132-3

Patrício, M. F., Julião, M., Fareleira, F., & Carneiro, A. V. (2013). Is the OSCE a feasible tool to assess competencies in undergraduate medical education? Medical Teacher, 35(6), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.774330

Pelgrim, E. A. M., Kramer, A. W. M., Mokkink, H. G. A., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2012). The process of feedback in workplace-based assessment: Organisation, delivery, continuity. Medical Education, 46(6), 604–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04266.x

Pendleton, D. (1984). The consultation: An approach to learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

Sachdeva, P. & Aw D. C. W. (2023). Case write-ups survey responses [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24471661.v1

Sandars, J. (2009). The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Medical Teacher, 31(8), 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903050374

Schon, D. A. (1984). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Stufflebeam, D. (2002). The CIPP model for evaluation. In The International Handbook of Educational Evaluation, 49, 279–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47559-6_16

*Pooja Sachdeva

110 Sengkang East Way,

Singapore 544886

96170342

Email address: pooja.sachdeva@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 3 July 2023

Accepted: 18 June 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 61-64

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/SC3071

Victoria Scudamore, Sze Yi Beh, Adam Foster & Michaela Goodson

School of Medicine, Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: This study compares online and in-person delivery of a weekly clinical reasoning seminar for fourth-year medical students at a Malaysian medical school. During the easing of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, the initial eight seminars took place online, followed by eleven in-person seminars. This study looks at student preference for online or in-person delivery and how these reasons differ due to gender.

Methods: An online questionnaire was sent to fourth-year medical students after returning to in-person seminars. The response rate was 60/128 (46.88%) and the data was analysed using SPSS software.

Results: 65% of students preferred in-person seminars and a larger proportion of female students (71.43%) preferred in-person sessions compared to male students (50.00%), although this was not statistically significant (p=0.11). A significantly larger proportion of female students preferred in-person seminars for the following reasons compared to male students: enjoyment (p=0.041), developing history-taking skills (55.56%) and for formulating differential diagnoses (p=0.046). Students were asked whether online or in-person seminars were most appropriate for eighteen reasons, they felt in-person seminars were most appropriate for 16/18 of these reasons.

Conclusions: More students preferred in-person clinical reasoning seminars and a higher proportion of these students were female. A significantly larger proportion of female students felt in-person seminars were better for; enjoyment and for developing history-taking skills and formulating differential diagnoses, compared to male students. The students preferred online seminars for home comforts and ease of travel, but they preferred in-person seminars for the other 16/18 reasons listed including all reasons linked to learning skills and interreacting with others.

Keywords: Online Teaching, In-person Teaching, Gender, Clinical Reasoning, Medical Students

I. INTRODUCTION

Fourth-year medical students at Newcastle Medical School Malaysia attend weekly clinical reasoning seminars as part of their ‘Clinical Decision Making’ (CDM) module. Each week of CDM covers a different medical speciality and students attend a seminar where the group works through a presentation with patient cases and they discuss how to diagnose, investigate and manage the patient. The sessions are attended by eleven students and the groups remain the same throughout the year. In 2021-22 the initial eight seminars took place online using Zoom video conferencing software and as COVID-19 restrictions eased in Malaysia the final eleven sessions took place in-person.

The academic performance of students undertaking online and in-person clinical reasoning seminars has been researched and third-year medical student academic performance was comparable in both settings (Babenko et al., 2022). However, there is currently no research regarding medical student preference for online or in-person delivery of clinical reasoning seminars. Medical student preference for online or in-person delivery of all parts of the curriculum has been analysed and second-year medical students at a US medical school had a preference for online lectures and there was a correlation between these students and those who felt online lectures reduced stress (Altaf et al., 2022).

A cohort study analysed participation in a teaching programme for US graduate physicians and this showed female students asked and answered less questions during in-person sessions compared to online sessions (Cromer et al., 2022). The results of this study are contrasting with my observations whereby female students participated less in online seminars and their participation increased when seminars returned to an in-person setting. This could be due to differences in the research environments or due to the group of observed students being small with less statistical significance.

My first research question was to understand medical student preference and reason for preference of online or in-person delivery of clinical reasoning seminars. My second research question was to establish if student preference differed due to gender and why.

II. METHODS

The data was collected using survey methodology with a self-developed questionnaire made using Microsoft forms. The questionnaire was emailed to all fourth-year medical students after they had experienced both session deliveries. Students were provided with a consent form and informed the research project was optional and were asked to provide voluntary consent before participating. Participants were informed they could withdraw from the project at any time up until the data was anonymised during data collection.

The survey response rate was 60/128 (46.88%), the low participation numbers are likely due to the data collection being optional and undertaken in the students own time. This could lead to a nonresponse bias, as it is likely the more engaged students participated and students with less motivation who did not participate may have responded differently. The data was analysed using SPSS software. Chi-squared tests were used to cross-tabulate the results and to calculate p-values to indicate data with statistical significance.

III. RESULTS

Overall 65% of students preferred in-person seminars and 71.43% (30/42) of female students preferred in-person sessions compared to 50.00% (9/18) of male students (p=0.11). The students were asked if they felt online or in-person seminars were best for eighteen different reasons (see table 1). There were three statistically significant reasons female students preferred in-person sessions more than male students (p<0.05). These were Enjoyment (p=0.041), developing history-taking skills (p=0.011) and formulating differential diagnoses (p=0.046).

The students felt in-person sessions were most appropriate for 16/18 of the reasons listed in (table 1). The reasons with the highest proportion of students feeling in-person were the most appropriate were; interaction with friends (95.00%), interaction with the facilitator (91.67%), and developing clinical reasoning skills (91.67%). There were only two reasons students felt online sessions were most appropriate, these were home comforts (98.33%) and ease of travel (91.67%).

Original data can be accessed in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23616627.v1 and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23616630.v1

Results are ranked from reasons with the highest proportion of students thinking in-person was most appropriate for that reason. P-values have been calculated to establish if there is statistical significance between the results for male and female students, significant results are highlighted in bold.

|

|

All students |

Female students |

Male students |

P-value |

|

Interaction with friends |

57/60 (95.00%) |

39/42 (92.86%) |

18/18 (100.00%) |

0.245 (>0.05) |

|

Interaction with the facilitator |

55/60 (91.67%) |

39/42 (92.86%) |

16/18 (88.89%) |

0.610 (>0.05) |

|

Developing clinical reasoning skills |

55/60 (91.67%) |

39/42 (92.86%) |

16/18 (88.89%) |

0.610 (>0.05) |

|

Learning from the facilitator |

51/60 (85.00%) |

35/42 (83.33%) |

16/18 (88.89%) |

0.581 (>0.05) |

|

Flow |

47/60 (78.33%) |

33/42 (78.57%) |

14/18 (77.78%) |

0.945 (>0.05) |

|

Developing history-taking skills |

46/60 (76.67%) |

36/42 (85.71%) |

10/18 (55.56%) |

0.011 (<0.05) |

|

Developing knowledge |

45/60 (75.00%) |

33/42 (78.57%) |

12/18 (66.67%) |

0.329 (>0.05) |

|

Ease of sharing opinions |

45/60 (75.00%) |

33/42 (78.57%) |

12/18 (66.67%) |

0.329 (>0.05) |

|

Enjoyment |

44/60 (73.33%) |

34/42 (80.95%) |

10/18 (55.56%) |

0.041 (<0.05) |

|

Learning from peers |

41/60 (68.33%) |

28/42 (66.67%) |

13/18 (72.22%) |

0.672 (>0.05) |

|

Formulating differential diagnoses |

41/60 (68.33%) |

32/42 (76.19%) |

9/18 (50.00%) |

0.046 (<0.05) |

|

Interpreting clinical data |

40/60 (66.67%) |

29/42 (69.05%) |

11/18 (61.11%) |

0.550 (>0.05) |

|

Formulating management plans |

39/60 (65.00%) |

29/42 (69.05%) |

10/18 (55.56%) |

0.315 (>0.05) |

|

Better for mental health |

36/60 (60.00%) |

26/42 (61.90%) |

10/18 (55.56%) |

0.645 (>0.05) |

|

Developing communication skills |

35/60 (58.33%) |

22/42 (52.38%) |

13/18 (72.22%) |

0.153 (>0.05) |

|

Interpreting investigations |

35/60 (58.33%) |

27/42 (64.29%) |

8/18 (44.44%) |

0.153 (>0.05) |

|

Ease of travel |

5/60 (8.33%) |

5/42 (11.90%) |

0/18 (0.00%) |

0.126 (>0.05) |

|

Home comforts |

1/60 (1.67%) |

1/42 (2.38%) |

0/18 (0.00%) |

0.509 (>0.05) |

|

Table 1. The proportion of medical students who felt in-person sessions were the most appropriate for the listed reasons. |

||||

IV. DISCUSSION

Overall, more students in our cohort preferred in-person clinical reasoning seminars and a larger proportion of these students were female than male, however, the difference in preference based on gender did not show statistical significance. This could be due to a smaller cohort of male respondents (18/60) compared to female respondents (42/60). However, even in a study of 488 medical and dental students there was no significant difference in preference for online or in-person delivery when asked about all sessions in the curriculum (Al-Azzam et al., 2020). A larger sample size of medical students will need to be analysed to establish if gender significantly influences student preference for online or in-person delivery of clinical reasoning seminars.

Students felt in-person seminars were better for 16/18 of the listed reasons. This included all reasons pertaining to interaction with other students and staff and all reasons regarding learning a variety of skills. The only two reasons students felt online sessions were better were ease of travel and home comforts. Therefore, this data suggests the only reasons the medical students preferred online seminars were due to the convenience of the setting, and they felt the learning and interaction were superior in in-person seminars.

Of these eighteen reasons, three reasons showed a significant difference in response based on gender, with more female students preferring in-person seminars for the following reasons: enjoyment, development of history-taking skills and formulating differential diagnoses. History-taking and formulating differential diagnoses are more commonly undertaken by doctors within in-person environments. Therefore, female medical students may have a stronger preference for learning skills in the same setting they will be undertaken in when they are doctors.

This study helps to identify the components of clinical reasoning seminars male or female students prefer to undertake online or in-person. Future research could try to identify the reasons for these preferences and to establish if female students have a stronger preference for learning a skill in the same environment it would be undertaken in when they become a doctor.

This research will have most transferability to educators designing clinical reasoning modules to undergraduate students. It may also have some transferability to any undergraduate seminars and to postgraduate medical education. Also, understanding the environment each gender prefers to learn in and why, could help to designing future educational programmes. Especially if these programmes have previously shown differing participation or attainment based on gender.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, students preferred in-person clinical reasoning seminars compared to online seminars and a higher percentage of female students preferred in-person compared to male students, although this was not statistically significant. Students had the strongest preference for in-person sessions due to interaction with friends and the facilitator and for developing clinical skills. Students had the strongest preference for online sessions due to home comforts and ease of travel. Female students preferred in-person seminars compared to male students for the following statistically significant reasons: enjoyment, developing history-taking skills and formulating differential diagnoses.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Victoria Scudamore was involved in data collection, data analysis and wrote this manuscript in full.

Dr Sze Yi Beh was involved in data collection and data analaysis.

Dr Adam Foster was involved in data collection and data analysis.

Dr Michaela Goodson supervised and advised on data collection and analysis.

Ethical Approval

Research and ethics approval was granted by the research committee at Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia on 08/02/2022 (Approval number: 18547/2022).

Data Availability

The data used in this paper is available in the Figshare repository through the following links with associated DOI’s https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23616627.v1 and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23616630.v1. The data is shared on the Figshare repository under the CC0 licence (no rights reserved) as there is no copywritten information included.

Funding

No additional funding was used to undertake this project.

Declaration of Interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Al-Azzam, N., Elsalem, L., & Gombedza, F. (2020). A cross-sectional study to determine factors affecting dental and medical students’ preference for virtual learning during the COVID-19 outbreak. Heliyon, 6(12), 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05704

Altaf, R., Kling, M., Hough, A., Baig, J., Ball, A., Goldstein, J., Brunworth, J., Chau, C., Dybas, M., & Jacobs, R. J. (2022). The association between distance learning, stress level, and perceived quality of education in medical students after transitioning to a fully online platform. Cureus, 14(4), 3. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.24071

Babenko, O., Ding, M., & Lee, A. S. (2022). In-person or online? The effect of delivery mode on team-based learning of clinical reasoning in a family medicine clerkship. Medical Sciences, 10(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci10030041

Cromer, S. J., D’Silva, K. M., Phadke, N. A., Lord, E., Rigotti, N. A., & Baer, H. J. (2022). Gender differences in the amount and type of student participation during in-person and virtual classes in academic medicine learning environments. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.43139

*Dr Victoria Scudamore

Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia

No. 1 Jalan Sarjana 1,

Kota Limu, EduCity@Iskandar,

Iskandar Puteri, Johor, Malaysia, 79200

Email: victoria.scudamore@nhs.net

Submitted: 5 July 2023

Accepted: 12 December 2023

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 1-14

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/OA3045

Dujeepa D Samarasekera1, Shuh Shing Lee1, Su Ping Yeo1, Julie Chen2, Ardi Findyartini3,4, Nadia Greviana3,4, Budi Wiweko3,5, Vishna Devi Nadarajah6, Chandramani Thuraisingham7, Jen-Hung Yang8,9, Lawrence Sherman10

1Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care/ Bau Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 3Medical Education Center, Indonesia Medical Education & Research Institute (IMERI), Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 4Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia/Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia; 6IMU Centre of Education and School of Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 7Department of Family Medicine, School of Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 8Medical Education and Humanities Research Center and Institute of Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; 9Department of Dermatology, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 10Meducate Global, LLC, Florida, USA

Abstract

Introduction: Continuing medical education and continuing professional development activities (CME/CPD) improve the practice of medical practitioners and allowing them to deliver quality clinical care. However, the systems that oversee CME/CPD as well as the processes around design, delivery, and accreditation vary widely across countries. This study explores the state of CME/CPD in the East and South East Asian region from the perspective of medical practitioners, and makes recommendations for improvement.

Methods: A multi-centre study was conducted across five institutions in Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan. The study instrument was a 28-item (27 five-point Likert scale and 1 open-ended items) validated questionnaire that focused on perceptions of the current content, processes and gaps in CME/CPD and further contextualised by educational experts from each participating site. Descriptive analysis was undertaken for quantitative data while the data from open-ended item was categorised into similar categories.

Results: A total of 867 medical practitioners participated in the study. For perceptions on current CME/CPD programme, 75.34% to 88.00% of respondents agreed that CME/CPD increased their skills and competence in providing quality clinical care. For the domain on pharmaceutical industry-supported CME/CPD, the issue of commercial influence was apparent with only 30.24%-56.92% of respondents believing that the CME/CPD in their institution was free from commercial bias. Key areas for improvement for future CME/CPD included 1) content and mode of delivery, 2) independence and funding, 3) administration, 4) location and accessibility and 5) policy and collaboration.

Conclusion: Accessible, practice-relevant content using diverse learning modalities offered by unbiased content providers and subject to transparent and rigorous accreditation processes with minimal administrative hassle are the main considerations for CME/CPD participants.

Keywords: Medical Education, Health Profession Education, Continuing Professional Development, Continuing Medical Education, Accreditation

Practice Highlights

- Identifying professional practice gaps of clinicians should be the first step.

- The state of CME/CPD varies among countries and addressing relevant needs is crucial.

- Clinicians agreed that CME/CPD improves their skills and knowledge but lacked time to participate.

- Potential improvements include relevant content free from commercial bias and delivery mode.

- Systematic governance and aligned regulations by physician credentialing agencies is recommended.

I. INTRODUCTION

Lifelong learning is an essential skill for all healthcare professionals. This is particularly true when new models of healthcare delivery are being implemented and there is increased focus on outcomes and values such as shorter hospital stay, greater accountability and transparency and emphasis on patient engagement (Sachdeva, 2016; Vinas et al., 2020). Recent literature highlights that continuing medical education and continuing professional development programs (CME/CPD) are crucial in providing current contextually relevant educational and developmental activities in maintaining knowledge, skills, and performance for clinicians and have proven to be effective (Cervero & Gaines, 2015; Drude et al., 2019; Forsetlund et al., 2009). CME is defined as “educational activities which serve to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance and relationships that a physician uses to provide services for patients, the public, or the profession” (Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, n.d.), while CPD is usually a broader and more inclusive term referring to the combination of formal CME and other activities type that are designed to assist healthcare professionals to acquire skills and knowledge essential for their professional growth (Sherman & Chappell, 2018). Critical systematic reviews of the literature have shown that CME/CPD improves practice and support professional activities of medical practitioners to deliver best patient care (Cervero & Gaines, 2015; Sachdeva, 2016).

Although CME/CPD has undergone enormous changes and growth over the past 25 years, the advancement in CPD still considerably lag behind as compared to undergraduate and graduate medical education (Sachdeva et al., 2016). Goals and objectives in CME/CPD are often poorly defined and there is a paucity of the curricular structure for medical practitioners (Sachdeva, 2016). Despite consistent evidence sharing that formal CME/CPD activities, such as conferences and workshops, have little or no long-lasting effect on medical practitioners, many CME/CPD providers continue to include these approaches as their major educational offerings while clinicians continue to attend to improve their practice (Mann, 2002). Additionally, there are environments where CME/CPD is not mandatory, and in some instances, non-existent (Sherman & Nishigori, 2020).

Despite CME/CPD’s importance, the state of CME/CPD varies widely across regions and countries. Unlike Europe and the United States, there is no parallel accreditation system for CME/CPD in Asia. CME/CPD does not follow a standard process in all countries and the requirements are also different. A short summary of the CME/CPD system in the countries which are studied in this article is provided in Appendix 1. However, there is still a lack of empirical data in understanding the CME/CPD in Asia. Only one study was conducted in Japan to assess the state of CPD in the country and to identify the gaps in the understanding of the medical practitioners’ needs (Sherman & Nishigori, 2020). Hence, this study aims to explore the state of CME/CPD in the East and South East Asian region from the perspective of medical practitioners, and make recommendations for improvement.

A. Theoretical Framework

Researchers have been proposing few theoretical frameworks which are related to CME/CPD. For this study, we will be using the Process of Change and Learning framework by Fox et al. (1989) to provide an overarching view on the process of change and learning among medical practitioners. This will be further enhanced by using adult learning theory (Knowles, 1989).

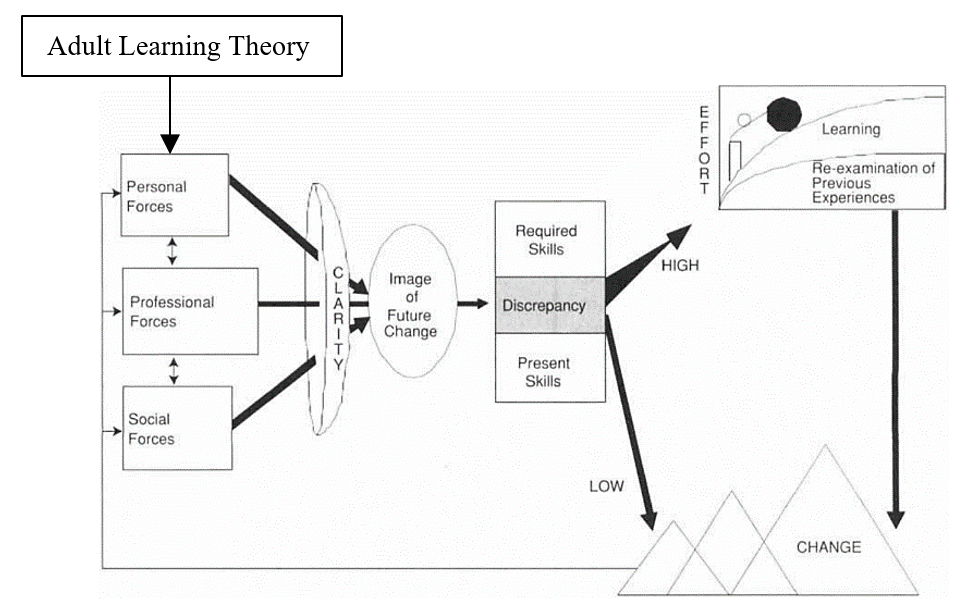

No discussion of practice informing theory in CME could exclude the work of Fox et al. (1989), who studied the process of change and learning in the lives of medical practitioners. They interviewed more than 350 medical practitioners to find out the types of learning activities that clinicians undertake and the important factors in the process of learning and change. The framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework related to CME/CPD using the process of change and learning (Fox et al., 1989) and adult learning theory (Knowles, 1989)

This framework clearly illustrated how change and learning occurs through several processes and how these changes were influenced by three forces. The actual process of change involves three iterative steps – preparing for the change, making the change, and sustaining or implementing the change in practice.

Through validated studies, we understand that there are three forces to prepare for the change, mainly personal, professional and social forces. Professional forces were found to be the most frequently motivated change. Personal forces, such as the desire for personal well-being, were infrequent and usually not the sole force for change. More often they were combined with professional forces, e.g. the desire to further one’s career. Social forces were also cited, usually combined with professional forces, e.g. relationships with colleagues.

Once the image of change has been developed, medical practitioners will evaluate the discrepancy between what new knowledge and skills are needed to achieve the change and estimate their current capacities. As shown in Figure 1, the perceived discrepancy is positively correlated with the effort that a medical practitioner will put in in learning. Therefore, the next step may involve attending a formal CME event if the discrepancy is high – to understand what is required and to assess or verify one’s own capabilities.

Although the Process of Change and Learning Framework provides us a big picture on how medical practitioners engaged in change and learning, it is insufficient to understand the humanist approach in understanding learning for human growth. It is widely recognised that autonomy and self-directed learning are the developmental nature for human desire to learn (Personal Forces). This behaviour is usually motivated by a mixture of external and internal motivation. This is important for the development of individuals toward autonomy, the self-directed learning, reflective practice and critical reflection, experiential learning, and transformative learning.

II. METHODS

This is a multi-centred study which employed a survey using a validated questionnaire and the section below will describe the data collection process, sampling of participants and data analysis coupled with a qualitative data gathering focus group with educational experts from each place participating. Five sites were involved in this study: Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan. Ethical approval was obtained from the respective Institutional Review Board [Reference Number: DSRB-2019-0449 (Singapore), UW 19-840 (HKU/HA HKW IRB) (Hong Kong), KET-1035/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPMetc.00.02/2019 (Indonesia), (CCH-IRB-200425) (Taiwan), IMU 467/2019 (Malaysia)].

The same questionnaire that was used and validated previously in Japan was modified for use in this region (Nishigori and Sherman, 2018). The questionnaire is a self-administered, 28-item test comprising 27 single or multiple-choice questions and an open-ended question for comments. Respondents were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree) for some of the questions. Demographic questions were included at the start of the survey (e.g. specialty, years of practice, prior participation in CME/CPD activities) followed by the following domains:

- Perceptions and satisfaction of clinicians with regard to current CME/CPD available for them

- Adequacy of the current CME/CPD available

- Impacts of CME/CPD in content coverage, evaluation, and development of learning

- Gaps in CME/CPD

- Future areas to focus on

The items were finalised following a group of experts’ meeting held in Singapore (March 2019) whereby the representatives (medical educationalists and medical practitioners) from participating sites discussed and went through the questions thoroughly. The meeting was moderated by an expert with over 28 years of experience in CME/CPD, and who designed the original study questionnaire. To add more local context and ensure that respondents were able to answer accurately, the questionnaire was translated into the native language and terms by the representatives in some locations.

Medical practitioners were invited to participate in the study. The study was conducted from July 2019 until May 2020. Voluntary, convenience, and snowball sampling was used and the representatives either disseminate the questionnaire link to their mailing list or through the various national organisation/institutions (Table 1) who then informed their members/faculty, in accordance with the ethics protocol guidelines. Reminders were sent until the response rate no longer increased. Implied consent was obtained from the participants when they proceeded to complete the survey after reading the information about the study on the first page.

|

Hong Kong |

Invitations sent by the local study investigators to members of the specialty colleges of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, academic colleagues and doctors who teach medical students [Note: There was no institutional dissemination] |

|

Malaysia |

|

|

Indonesia |

|

|

Singapore |

|

|

Taiwan |

|

Table 1. Organisations/Institutions in each site which disseminated the questionnaire

A. Data Analysis

The investigators from Singapore collated the anonymised raw data file from the five locations and did the first round of analysis. For quantitative data, descriptive analysis was done using Microsoft Excel to compare the data across the 5 locations. For qualitative data (1 open-ended question related to future improvements), a content analysis was used to analyse the data by grouping comments with similar concepts and assigning an appropriate category. These processes were discussed and verified by 3 coders.

III. RESULTS

A. Demographics

The number of responses received is shown in Appendix 2, together with the data from key demographic questions. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Figshare repository – https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22345111 (Samarasekera et al., 2023).

In Malaysia and Singapore, Family Physicians made up the majority of their responses, with 43.86% and 44.29% respectively. Internal Medicine clinicians were the main participants in Hong Kong (60.00%) while 42.44% of the respondents in Indonesia were General Physicians.

As for primary practice setting, the majority of respondents from 4 of the sites were from university hospital/academic health centre – Singapore (34.29%), Hong Kong (40.0%), Indonesia (29.76%) and Taiwan (94.66%). For Malaysia, government/municipal hospital (26.96%) and government health clinic (based on the responses from “Others” field) were the most common work settings.

Moving to years in medical practice, many respondents from Indonesia and Malaysia (31.22% and 48.89% respectively) were relatively younger with only 6 – 10 years of practice. Conversely, Hong Kong had the most experienced pool of respondents with 44.00% having more than 25 years of practice.

The majority of the participants had prior medical education training – Singapore (75.71%), Indonesia (85.37%) and Malaysia (78.87%). However, the reverse was observed in Hong Kong (21.74%) and Taiwan (6.85%), which may be related to not catching meaning of the item.

B. Perceptions of the Current CME/CPD System

Regarding the CME/CPD status of the respondents and the system in their place, most were aware of the system, with over 90.00% for Singapore (95.38%), Hong Kong (92.00%) and Malaysia (99.52%). Indonesia (62.44%) and Taiwan (75.34%) had lower awareness.

Regarding the understanding the need for Inter-professional Continuing Education (IPCE) [involving more than one healthcare professions) CPD in their place, more than half of the respondents (Singapore – 75.38%, Hong Kong – 56.00%, Indonesia – 87.80%, Malaysia -72.01%, Taiwan- 69.86%) were aware.

Respondents from Singapore attended more CME/CPD events compared with the others in the year leading to the survey (35.38% attended 41-50 hours; 24.62% attended more than 50 hours). However, Indonesia had 24.10% of the clinicians who did not participate in any activity at all in the last 12 months while 54.97% participated between 11-30 hours. A similar pattern was noted in Taiwan with 13.70% of the participants having not attended and 52.06% participating between 11-30 hours.

Respondents strongly agreed and agreed that participating in some form of CME/CPD would increase their skills and competence (Singapore – 83.08%, Hong Kong – 88.00%, Indonesia -81.46%, Malaysia – 89.71%, Taiwan – 75.34%) and thereby ensuring that they have current knowledge that helps to provide the best care for their patients (Singapore – 84.62%, Hong Kong – 88.00%, Indonesia – 86.34%, Malaysia – 91.38%, Taiwan – 71.23%).

When considering whether participation in CME/CPD should be mandatory for all clinicians, there were 2 distinct groups– those whereby most respondents strongly agreed and agreed (Singapore – 80.00%, Hong Kong – 88.00%, Malaysia – 83.02%) compared to Indonesia (55.61%) and Taiwan (53.42%).

C. Perceptions of Industry-supported CME/CPD

Only 30.24% in Indonesia believed that the CME/CPD in their place is free from commercial bias. However, the number is slightly higher in Hong Kong (48.00%), Malaysia (42.11%) and Taiwan (45.21%) while those from Singapore (56.92%) were more confident that CME/CPD is free from bias.

The majority of the respondents knew that pharmaceutical companies commercially supported some of these programmes that were developed by an independent education provider (Singapore – 81.54%, Hong Kong – 80.00%, Indonesia – 82.44%, Malaysia – 79.67%, Taiwan – 72.60%). Despite these, a large number had participated in these programmes (Singapore – 87.69%, Hong Kong – 68.00%, Indonesia – 64.39%, Malaysia – 84.93%) except Taiwan (57.53%).

When asked about what they think about CME/CPD that is developed by an independent CME/CPD provider with financial support from the pharmaceutical industry, these were the top 3 responses, and the first two are actually misperceptions reported regarding independent CME/CPD:

- The pharmaceutical company can suggest speakers

- The pharmaceutical company works with the educational provider to develop content

- The content is developed independently by the education company to address the needs of the learners

The proportion of respondents who selected these 3 were quite comparable across all sites It is worth noting that none from Indonesia selected “the pharmaceutical company has no influence on the content and speaker selection”. Appendix 3 shows the full data for this question along with other key questions regarding perceptions of respondents to CME/CPD funded by industry.

While approximately 75% of the respondents in Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia and Malaysia strongly agreed and agreed that CME/CPD developed by independent CME/CPD providers and supported by the pharmaceutical industry would be beneficial to provide current and clinically important information, the number is smaller in Taiwan (61.64%). As to whether such programmes could be counted towards CME requirement, at least two-third of the respondents in Singapore (80.00%), Hong Kong (68.00%), Indonesia (75.61%), Malaysia (69.61%) agreed and strongly agreed, while only close to half from Taiwan (49.32%) felt that it should be counted. Taiwan’s practicing clinicians suggest CME/CPD is more appropriate to be developed by independent CME/CPD providers rather than supported by the pharmaceutical industry.

D. Future CME/CPD Programme

The survey also had a question comprising 7 options to find out more about clinicians’ preferences. In all 5 locations, the more common reason is that physician will choose an activity based on the relevance of the education to their practice (Singapore – 30.00%, Hong Kong – 26.44%, Indonesia – 31.16%, Malaysia – 31.22%, Taiwan – 23.76%) or their clinical specialty (Singapore – 23.50%, Hong Kong – 26.44%, Indonesia – 21.38%, Malaysia – 29.46%, Taiwan – 27.23%). The next common reason is curiosity for the topic (but not necessarily related to practice) – Singapore (18.50%), Hong Kong (17.24%), Indonesia (15.89%), Malaysia (16.59%), Taiwan (18.81%).

To have a better understanding on the needs of the clinicians regarding CME/CPD activities, respondents were asked on the items that is missing from the CME/CPD currently available to them. The lack of a variety of educational formats such as live, online/web-based, experiential program, preceptorships (Singapore – 17.58%, Hong Kong – 14.29%, Indonesia – 12.35%, Malaysia -13.33%, Taiwan – 20.37%) and shortage of innovative learning environments and new creative formats (Singapore – 18.18%, Hong Kong – 18.57%, Indonesia – 14.74%, Malaysia – 14.35%, Taiwan – 17.28%) were the top 2 choices selected by the respondents in each place. Appendix 4 shows the full data for this question. Among the comments given for “Others”, many respondents from Indonesia felt that current courses are pricy and free courses are scarce thus would like to see more of these. It should be noted that data collection was prior to COVID-19 and thus online learning was uncommon at that time.

Key barriers to participation included courses not offered at convenient times (Singapore – 36.00%, Hong Kong – 29.41%, Indonesia – 21.46%, Malaysia – 31.34%, Taiwan – 27.03%), followed by courses not covered in their budget and topics not relevant/clinically important. For those who selected “Others”, most of them re-emphasised one of the choices (not offered at convenient time) that they did not have time.

Finally, Singapore and Malaysia respondents preferred (1) authoring medical papers and books, (2) serving as a supervisory physician in undergraduate and post-graduate clinical training programs and (3) reading journal-based or other printed materials as their top 3 weighted average mode of CME/CPD. On the other hand, those from Indonesia, Malaysia and Taiwan preferred (1) hands-on learning, (2) live regional educational activities, including lectures, seminars, workshops, and conferences and (3) attending national and international conferences/symposia (in different order among the 3 locations).

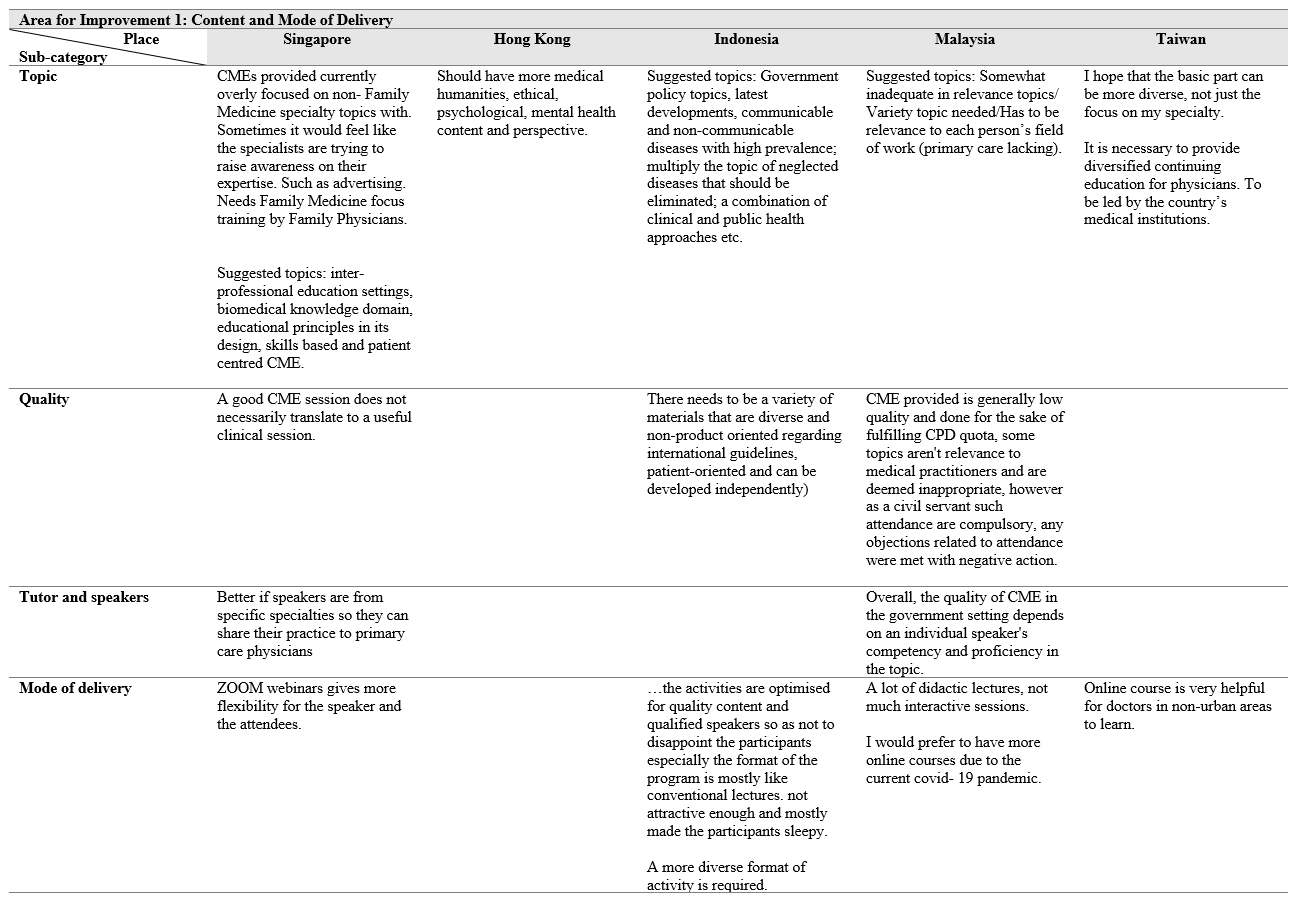

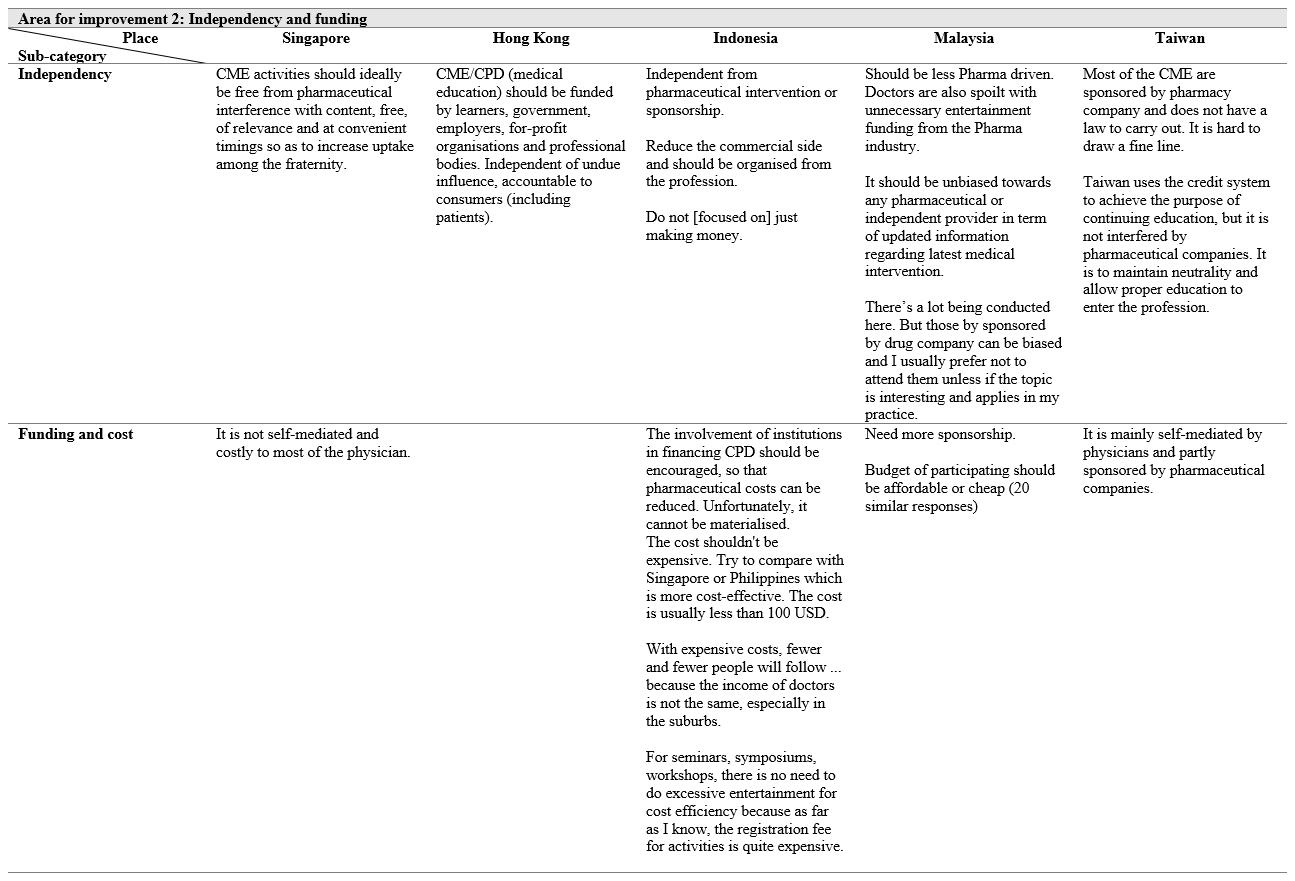

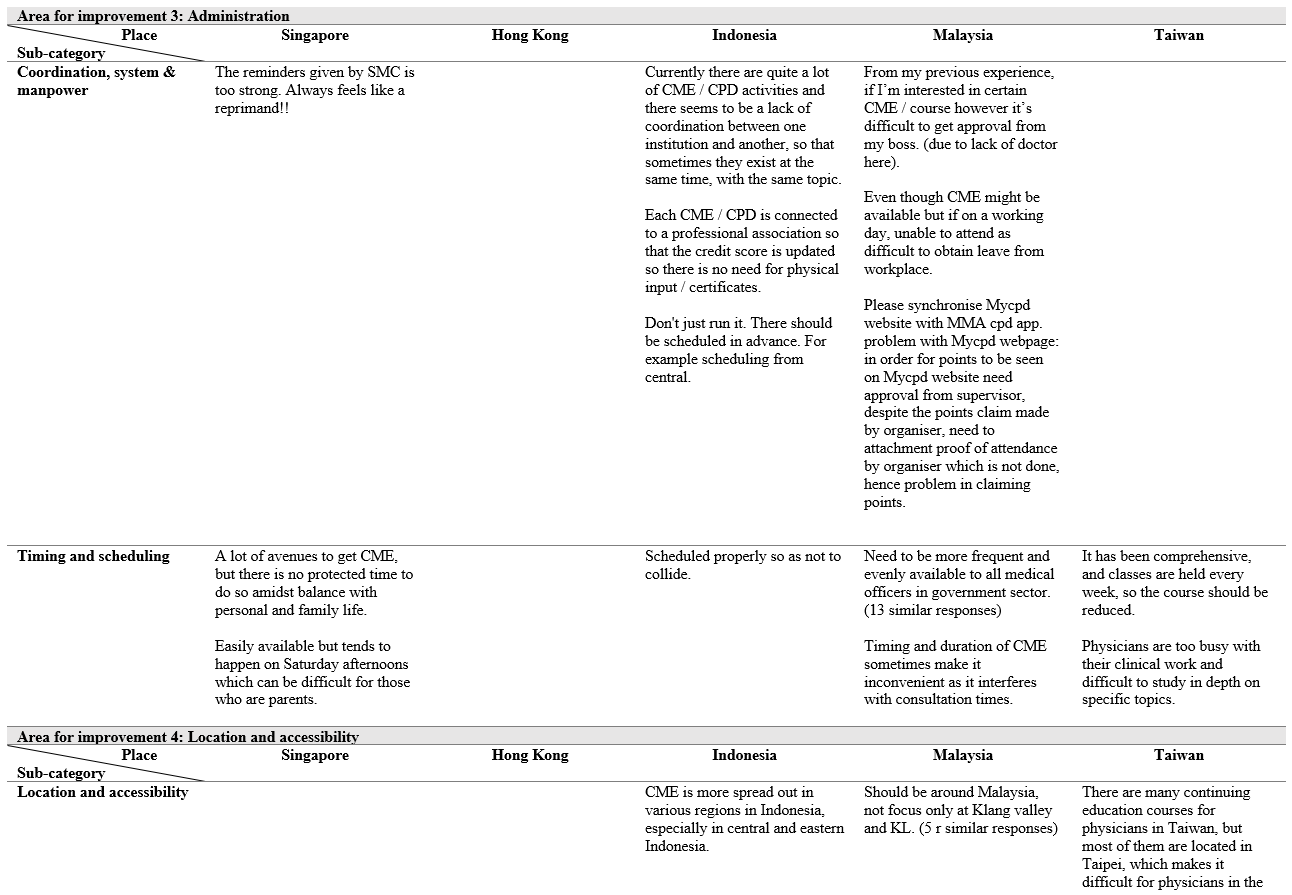

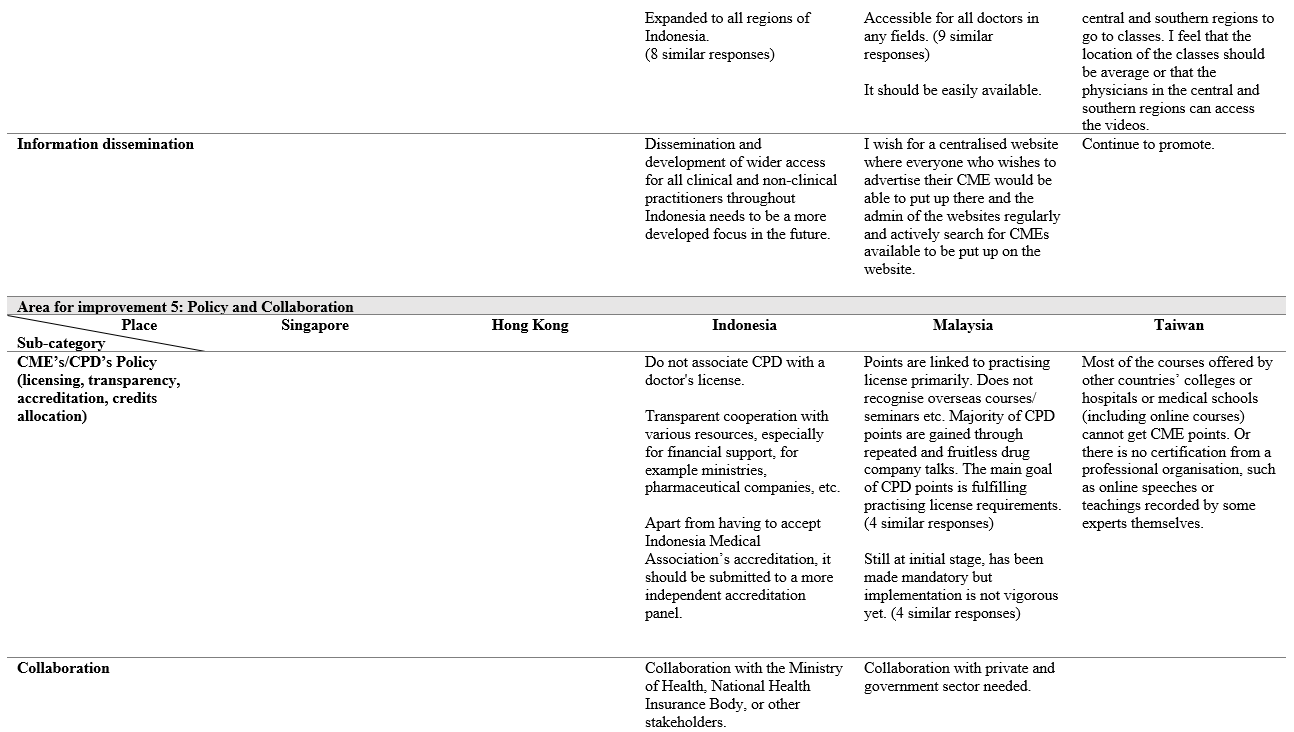

Although only one open-ended question was gathered from the participants, it had revealed rich data on the issues and challenges of CME/CPD in their own respective area. The positive comments received were quite generic. Mostly mentioned that the CME/CPD has been running well (Indonesia), acceptable and adequate, relevant and well-structured (Malaysia), still meeting the needs, adequate and organised (Taiwan) and comprehensive, structured CME for every month and good and adequate system in place with little bias in public institution (Singapore). The content analysis revealed 6 categories of areas of improvement as follows:

- Area for improvement 1: Content and mode of delivery

- Area for improvement 2: Independency and funding (includes cost)

- Area for improvement 3: Administration

- Area for improvement 4: Location and accessibility

- Area for improvement 5: Policy and collaboration

- Area for improvement 6: Others (motivation and evaluation)

IV. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to survey the state of the CME/CPD systems in this region including clinicians’ perceptions on the involvement of the pharmaceutical industry and to see whether their perceptions are aligned with that of the accreditation organisations. These would allow the organisations to come up with relevant policies to improve the CME/CPD systems.

The survey seeks to explore several domains and first looked at their perceptions of the current CME/CPD programme. It is unsurprising that a large proportion of the respondents from all five areas were aware of the CME/CPD programme in their place and most strongly agreed and agreed that participating in some form of CME/CPD would increase their skills and competence (between 75.34% and 88.00%) and thereby ensuring that they have current knowledge that helps to provide the best care for their patients. This is higher than that of Japan whereby only 41% felt that their skills and competence has increased (Sherman and Nishigori, 2018).