Report of the 12th ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS)

Submitted: 6 May 2024

Accepted: 28 August 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, SP01, 22-24

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-SP01/SP008

Jamuna Vadivelu1, Wei-Han Hong1 & April Camilla Roslani2

1Medical Education & Research Development Unit (MERDU), Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 2Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia

I. INTRODUCTION

The ASEAN Medical Schools Network (AMSN) was established in 2012 with the aims of promoting friendship and collaboration among the leading medical schools in ASEAN. In line with the ASEAN Vision 2020, we work as one community, sharing resources and building capacity to achieve excellence in medical education and healthcare. The 12th ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS), held from 28-29 July 2023 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, focused on capacity building initiatives for an ASEAN healthcare workforce that can work across borders, facilitating mobility of healthcare professionals who are trained to adapt to local cultural practices and sensitivities.

Internationalisation of higher education across regions is a multidimensional process. To promote the development of a regional integrated higher education space, the 12th AMDS was delivered in the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, as a two-day programme over three sessions and a workshop, with each school sharing their best practices regarding preparation of practice-ready graduates, assessments and learner-centred coaching.

II. ACTIVITIES DURING THE 12TH AMDS

A diverse group of medical educators presented current initiatives at their respective schools in Sessions 1, 2 and 3. They were then asked to define strategies for multicentre collaboration to advance the current state of preparing future-ready healthcare professionals who can work across ASEAN through medical education initiatives by harnessing the power of collective expertise.

Session 1, moderated by AMSN President, Professor Charlotte Chiong (Philippines), addressed the preparation of graduates who are ready for practice. Professor Yang Faridah Abdul Aziz (Malaysia) focused on the shift to competence-based education in Malaysia, while Adjunct Professor Lau Tang Ching (Singapore) shared on how developing common curricula for healthcare adjacent fields could facilitate interprofessional education. The design and implementation of competence-based medical curricula was further developed by Professor Nguyen Huu Tu (Vietnam), while the experience of Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital in non-compensatory evaluation & Pi-shape education was shared by Associate Professor Tripop Lertbynnaphong (Thailand).

Session 2 focused on teaching, mentoring and coaching in medical education, moderated by Associate Professor Marion Aw (Singapore). The need to refine the roles of trainers in postgraduate clinical programmes was presented by Professor Shahrul Bahyah (Malaysia), further illustrated by the PGH experience of supporting medical trainees during the pandemic shared by Associate Professor Dionne Sacdalan (Philippines). Presentations on the importance of coaching in a learner-centered approach, by Professor Dwiana Ocviyanti (Indonesia), and the transformative impact of problem-based learning by Professor Khin Aung Htun (Yangon), rounded off the session.

Assistant Professor Kanokwaroon Watananirun (Thailand) moderated Session 3, on best practices in assessments. While Professor Christina Tan (Malaysia) tackled the thorny issue of hawks and doves impacting assessments, Dr Nurhanis Syazni Roslan (Malaysia) showed how standard setting in high-stakes assessments provided evidence of validity. The theme was further developed by Dr Dujeepa Samarasekera (Singapore) who spoke on performance-based assessments, while assessment implementation of interprofessional health education across the Faculties of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing were described by Assoc Prof Ahmad Hamim Sadewa (Indonesia).

In Session 4, the workshop on harmonisation of curricula across ASEAN moderated by Associate Professor Prapat Wanitpongpan (Thailand), participants were divided into four groups to discuss different strategic approaches. The discussion on the ASEAN graduate profile was led by Dr Hong Wei-Han (Malaysia), Professor Ari Fahrial Syam (Indonesia) steered the group on ASEAN Collaborative Learning, the discussant for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) was Prof. Bernadette Heizel M. Reyes (Phillipines) while ASEAN Faculty development was chaired by Dr Dujeepa Samarasekera (Singapore). Participants were led through presentations and structured discussions about the challenges of initiatives in future-proofing health care professional who could work across borders with increased mobility and the opportunities offered through international collaboration.

Led by Professor Muhammad Yazid Jalaludin (Malaysia), the AMSN Student Chapter Programme was aimed to encourage networking and leadership, through discussions on current local medical education initiatives and brainstorming on proposed improvements amongst medical students. In preparation for the meeting, the student representatives met online prior to the event and had discussion on Comprehensive Assessment for Future-ready Medical Practitioners. The student representatives from each institution prepared and presented a poster amongst their peers. The students presented on Authentic Assessments, Assessment of Professionalism and Simulation Based Assessment during the Student Dialogue Session, in the presence of the educators. During the summit dinner, students also presented cultural performances and attended the event with all the delegates. The educators and students also had the opportunity to engage with each other through joint academic and social activities such as Faculty of Medicine UM Tour (Centrepoint, Pathology Museum, Anatomy Dissection Hall), Campus Tour which includes Dewan Tunku Canselor and Rimba Ilmu, and KL City Tour around Central Market, Merdeka Square and the Sultan Abdul Samad building.

III. STRATEGIC INITIATIVES

The workshop focused on developing strategies for harmonisation of curricula across ASEAN. All the members present were allocated into four different groups to consider international strategies in future-proofing healthcare professionals for the region. Four strategic initiatives were discussed, which included, creating a generic ASEAN graduate profile, collaborative learning in the region, addressing diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and a robust ASEAN Faculty development.

Summarised below are the working group’s recommendations for consideration.

- To use the graduate profile that was developed through consensus in the Tuning Academy – South East project (TA-SE). This meta-profile consisted of common regional competencies (core and subject-specific) for medicine programme in this region. A review of the competencies with potential challenges were discussed with the aim to promote development of common goals in human resource capacity, curriculum development recognition of professional qualifications and academic credentialing within the region.

- To develop a standardised medical curriculum for medical schools within countries in the ASEAN region. Assure that these curricula are comprehensive, but also allow for geographic/regional variability—knowing that analysing the effect of curricula on learners requires some variability and because different courses will have different goals (research, education, clinical, public health, etc.). To foster best practices in development and implementation of these curricula.

- To develop database of ASEAN Experts to formulate an ASEAN Framework for Faculty Development. To review processes, policies, bureaucracies which may restrict mobility and sharing.

- Develop standardised evaluation tools that could give rise to large-scale qualitative and quantitative data sets from learners’ global health experiences. Develop multi-institutional, multidisciplinary research networks to compile and share data. Investigate methods to improve coordination of efforts between global health GME programs and research networks to facilitate above recommendations.

IV. CONSENSUS STATEMENT

Recommendations and priority areas for the development of future ready ASEAN health professionals across this region will be based on the outcomes of discussions on the four strategies for the future-proofing of healthcare professionals in the region. A developmental and implementation plan will be designed at future meetings.

Notes on Contributors

JV was responsible for conceptualisation the paper. All authors were responsible for the discussion. JV was responsible for the first draft of the manuscript. HWH and ACR provided their opinions and suggestions. All authors revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the organising committee, all speakers, all members of the AMSN and all medical students who have participated actively in the discussion during the AMDS.

Funding

There was no funding allocated for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

*Jamuna Vadivelu

Medical Education & Research Development Unit (MERDU),

Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

+603-7967 5739

Email: jamuna@ummc.edu.my

Submitted: 31 March 2024

Accepted: 26 August 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, SP01, 19-21

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-SP01/SP007

Yodi Mahendradhata

Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia

I. INTRODUCTION

The Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at Universitas Gadjah Mada (FMPHN UGM) has a rich and illustrious history dating back to its establishment in 1946. Originally known as the Faculty of Medicine, it predated establishment of Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM), which was founded in 1949 as Indonesia’s first national university. From its inception, FMPHN UGM has been dedicated to training healthcare professionals and conducting research to address the health needs of Indonesia. Over the years, the Faculty has expanded its scope to include Public Health, Nutrition and Nursing programs, reflecting a commitment to an interprofessional approach to healthcare education and practice.

Throughout its history, FMPHN UGM has played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of healthcare and healthcare professionals’ education in Indonesia. It has produced generations of doctors, public health experts, nutritionists/dietitians and nurses who have gone on to serve their communities and contribute to advancements in health policy, research, and practice. The Faculty has also been at the forefront of addressing key health challenges facing Indonesia, such as infectious diseases, maternal and child health, non-communicable diseases, and disasters (e.g. tsunami, volcanic eruptions, pandemic). Its research initiatives have led to the development of innovative interventions and solutions to improve health outcomes and promote wellbeing across the nation.

Today, we are poised to elevate to the Southeast Asian region our initiatives for training healthcare professionals, conducting cutting-edge research, and working collaboratively with communities to improve health and wellbeing. In line with this commitment, FMPHN UGM is looking forward to work through the ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS) on three proposed strategic areas: (1) promoting social accountability of academic medical institutions in the region; (2) strengthening capacity of academic medical institutions in the region for disaster health management; (3) enhancing the role academic medical institutions to promote evidence-informed policy in the region.

II. PROMOTING SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY

Social accountability in medical education can be defined as: “The obligation to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region, and/or nation they have a mandate to serve. The priority health concerns are to be identified jointly by governments, health care organisations, health professionals, and the public” (Boelen & Heck, 1995). This definition emphasises the responsibility of medical schools to align their activities with the health needs and priorities of the communities they serve, as identified through collaborative efforts involving various stakeholders. It underscores the importance of education, research, and service in addressing these priority health concerns and promoting the overall wellbeing of society. Promoting social accountability in medical education is essential for ASEAN Medical Deans to fulfil their mandate of producing competent, compassionate, and socially responsible healthcare professionals who can effectively address the health needs of the Southeast Asian region.

For many decades, FMPHN UGM has demonstrated a strong commitment to promoting social accountability in health professionals’ education through various experiences and achievements: (1) implementing community-based education programs that provide students with opportunities to engage directly with communities and address their health needs; (2) establishing partnerships with local communities, government agencies, and non-governmental organisations to identify and address priority health concerns; (3) integrating social accountability principles into the curricula of medical, public health, nutrition and nursing programs; (4) conducting research that addresses pressing health issues facing Indonesian communities. Overall, the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at Universitas Gadjah Mada has demonstrated a strong commitment to promoting social accountability in medical education through its community-based education programs, partnerships with communities, curricular integration, research for social impact, service-learning initiatives, and advocacy efforts. These experiences and achievements serve as examples of best practices in promoting social accountability within medical education in the Southeast Asian region. These achievements have led to the recent award of certificate of merit in social accountability by AMEE International Association for Health Professions Education as part of the ASPIRE to excellence award.

III. STRENGTHENING CAPACITY FOR DISASTER HEALTH MANAGEMENT

Disaster health management can be defined as: “The organisation, coordination, and management of health sector response and recovery efforts in the event of disasters. It involves preparedness, response, relief, and recovery activities aimed at minimising the health impact of disasters on affected populations” (World Health Organization, 2020). This definition underscores the importance of a coordinated and integrated approach to managing health sector response efforts during all phases of a disaster, from preparedness and response to relief and recovery. It emphasises the need for proactive planning, effective coordination, and timely interventions to minimise the health impact of disasters and support the wellbeing of affected populations. ASEAN Medical Deans have a unique opportunity and responsibility to contribute to strengthening the capacity of medical schools for disaster health management in the Southeast Asian region. By leveraging their expertise, resources, and networks, they can play a critical role in preparing future healthcare professionals, advancing research and innovation, enhancing institutional preparedness, fostering community engagement, and advocating for policy change to build resilience and mitigate the health impact of disasters.

The Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) has a strong track record of experiences and achievements in disaster health management and building capacity for disaster health management. Some of these notable experiences and achievements include: (1) participated in disaster response and relief efforts during various natural disasters, including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods, and tsunamis; (2) conducted research and innovation projects focused on disaster health management; (3) engaged with local communities to raise awareness about disaster preparedness and response; (4) integrated disaster health management into its education and training programs for students, healthcare professionals, and community members. Overall, the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at Universitas Gadjah Mada has demonstrated significant experiences and achievements in disaster health management and building capacity for disaster health management. Through its research, education, community engagement, policy advocacy, and international collaboration efforts, the Faculty continues to play a critical role in strengthening disaster resilience, reducing health risks, and improving health outcomes for vulnerable populations in Indonesia and beyond. These achievements have led to the recent appointment of FMPHN UGM as the Secretariat of the ASEAN Institute for Disaster Health Management and the ASEAN Journal of Disaster Health Management.

IV. ENHANCING EVIDENCE-INFORMED HEALTH POLICIES

Evidence-informed policy making can be defined as: “a systematic and transparent approach that draws on the best available data, research and other forms of evidence and knowledge” (World Health Organization, 2024). This definition emphasises the importance of utilising high-quality scientific knowledge and research evidence to inform policy-making processes. It underscores the need for policymakers to rely on evidence-based practices and data-driven approaches to develop and implement policies that effectively address health challenges and contribute to achieving desired health outcomes. ASEAN Medical Deans have a unique opportunity and responsibility to contribute to strengthening the capacity of medical schools for enhancing evidence-informed policy in the Southeast Asian region. By leveraging their expertise, resources, and networks, they can play a vital role in promoting evidence-based approaches to policy-making and driving positive changes in health systems and outcomes across the region.

The Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) has demonstrated several experiences and achievements in enhancing evidence-informed policy and building capacity for evidence-informed policy. Some notable examples include: (1) strong track record of conducting high-quality research, which contributes valuable evidence to inform policy-making processes; (2) actively engage in policy advocacy efforts to promote evidence-informed policy-making; (3) collaborates closely with government agencies, non-governmental organisations, and other stakeholders to strengthen evidence-informed policy-making processes; (4) provides training and capacity-building programs to enhance the skills and competencies of students, researchers, and policymakers in evidence-informed policy-making; (5) actively engages in knowledge translation and dissemination activities to ensure that research findings reach policymakers, practitioners, and other relevant stakeholders. Overall, the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at UGM has made significant contributions to enhancing evidence-informed policy and building capacity for evidence-informed policy-making. Through its research excellence, policy advocacy, collaboration with stakeholders, curricular integration, capacity-building efforts, and knowledge translation activities, the faculty continues to play a vital role in promoting evidence-based approaches to improving health policies and outcomes in Indonesia and beyond. These achievements led to the recent appointment of the Dean of FMPHN UGM as member of the Global Steering Group of WHO Evidence to Policy Network (EvipNet) and initation of the ADVISE (Advancing Evidence-Informed Policy In South East Asia region) initiative supported by WHO Evidence to policy and impact unit in collaboration with the TDR, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases.

V. EPILOGUE

Our commitment to training the next generation of healthcare professionals, conducting groundbreaking research, and fostering community partnerships resonates with the core values of AMDS. As we look forward to contributing to the advancement of AMDS, we are poised to champion social accountability, ensuring that academic medical institutions across the region prioritise the needs of the communities they serve. We are steadfast in our resolve to strengthen the capacity of academic medical institutions for disaster health management, equipping future healthcare leaders with the tools and knowledge needed to respond effectively to crises. Moreover, we are committed to promoting evidence-informed policy, harnessing the power of research and innovation to shape policies that improve health outcomes and enhance the wellbeing of individuals and communities throughout the ASEAN region. Together, united in purpose and vision, AMDS will continue to lead, inspire, and drive positive change for the betterment of healthcare and humanity in the region and beyond.

Notes on Contributors

The author confirms sole responsibility for conception and manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgement

The author received no specific technical help, financial, material support or contributions for the writing of this article.

Funding

The author received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for the writing of this article.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares no known competing financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

Boelen, C., & Heck, J. E. (1995). Defining and measuring the social accountability of medical schools. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/defining-and-measuring-the-social-accountability-of-medical-schools

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO glossary of health emergency and disaster risk management terminology. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003699

World Health Organization. (2024). Citizen engagement in evidence-informed policy-making: A guide to mini-publics. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081413

*Yodi Mahendradhata

Faculty of Medicine,

Public Health and Nursing

Universitas Gadjah Mada,

Sekip Utara, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia

Email: ymahendradhata@ugm.ac.id

Submitted: 21 June 2024

Accepted: 20 August 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, SP01, 1-3

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-SP01/SP001

Dujeepa D. Samarasekera1 & Dow Rhoon Koh2

1Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2International Relations, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

In anticipation of the development of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) by 2015, the ASEAN Medical Schools Network (AMSN) was established in 2012 by Clinical Professor Udom Kachintorn during his tenure as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University. The AMSN aims to promote friendship and collaboration among leading medical schools in the ASEAN region, achieve excellence in medical education and healthcare, share human resources, and assist in capacity building in medical education and research. Through the AMSN, the ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS) establishes a platform for deans and leadership of the regional medical schools to meet to discuss, share and brainstorm over key challenges in medical education and health care, creating a cohesive framework and leading to a unified action and solutioning among ASEAN nations. This flagship summit of the AMSN seeks to share research development in common areas of interest and develop common basic global standards in medical education and healthcare systems through cooperative efforts and strategic partnerships. The summit also provides opportunities to explore student exchange cooperative student projects across the region.

II. HISTORIC GATHERING

In a landmark event for the ASEAN community, the 1st summit marked the first-ever assembly of medical education leaders, including Deans and Rectors, from the 10 ASEAN member states: Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Brunei. This historic convergence took place in September 2012 at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, serving as a pivotal platform for these leaders to share their visions, exchange collaborative ideas, and set the stage for future joint initiatives. In the spirit of ASEAN centrality, the summit underscored the importance of collective action to address the healthcare needs of the 600 million people within the ASEAN community, highlighting the potential for significant advancements through shared expertise and resources.

III. DIVERSE PARTICIPATION

The inaugural summit witnessed the active participation of 12 renowned medical schools from various ASEAN countries, enriching the collaborative discussions with a wide array of perspectives and experiences. The founding institutions included:

- PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam

- Faculty of Medicine, University of Health Sciences, Cambodia

- International University, Cambodia

- Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia

- Faculty of Medicine, University of Health Sciences, Lao PDR

- Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia

- University of Medicine, Yangon, Myanmar

- University of Medicine, Mandalay, Myanmar

- University of Philippines College of Medicine

- Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore

- Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand

- Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand

- Hanoi Medical University, Vietnam

These institutions played a critical role in the success of the summit, contributing their unique insights and expertise to the collective dialogue aimed at enhancing medical education and healthcare across the region. Since inception, other ASEAN institutions have also joined the group adding diversity and new perspectives to the AMSN. The newer schools include:

- Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia

- Universiti Sains Malaysia. Malaysia

- University of Santo Thomas, Philippines

- University of East Ramon Magsaysay, Philippines

- Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand

- University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam

- Hue Medicine and Pharmacy University, Vietnam

IV. ASEAN MEDICAL SCHOOLS NETWORK ORGANISATION

The establishment of the AMSN during the inaugural AMDS provided the organisational structure to facilitate sustained collaboration and strategic planning for the network. The AMSN is chaired by a rotating President decided by consensus during the AMSN board meeting, and each President term runs for 2 years. The President is supported by a secretariat that leverages on the administrative structure of the institution the President comes from. The annual AMDS is also hosted by rotation across the member institutions of the AMSN and decided by consensus at the board meeting. Institutions can tap on financial support from a generous donation by the China Medical Board if needed to host the annual meeting. Through early discussions, the network established four specialised working groups to realise its mission: each tasked with addressing key areas essential for the advancement of medical education and healthcare systems within ASEAN. The working groups are:

- Education Work Group: Focused on standardising and enhancing medical education curricula across member institutions to ensure high-quality training for future healthcare professionals.

- Student Exchange Work Group: Aimed at promoting student mobility and exchange programs to foster cross-cultural learning and collaboration, thereby enriching the educational experience and broadening the perspectives of medical students.

- Research Work Group: Dedicated to advancing collaborative research efforts, sharing resources and expertise, and addressing regional health challenges through joint research projects and initiatives.

- Accreditation Work Group: Tasked with developing and implementing accreditation standards and processes to ensure that medical schools within the ASEAN network meet basic globally recognised benchmarks of excellence.

V. KEY ACTIVITIES AND MILESTONES

In the early years, the AMSN supported student-led collaborative project – ASEAN Student Collaborative Project (ASCP) where student groups from the respective institutions come together to share and collaborate in joint projects. The students would run their programme in parallel to that of the main AMDS. Where appropriate, the students are also given opportunities to present to the Deans a summary of their discussions. The student meetings also included student dialogue sessions guided by local faculty and later evolved to a formal student chapter within the AMSN in 2022 and an addendum was appended to the AMSN charter.

The research working group fostered a spirit of sharing and collaboration across a range of areas from public health, infectious diseases (HIV, dengue, TB, COVID-19) and non-communicable diseases (cancer, biomarkers, cardiovascular and aging). In order to facilitate greater collaboration, an ASEAN Research Collaborative Fund (ARCF) was set up with a funding provided by the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS) and administered by a committee chaired by the University of Malaya. The ARCF provides support for travel grants, joint symposia and meetings.

For education, discussions over curricular harmonisation, transfer of credits, faculty development, consolidation of local journals on the web and student exchange were made. The covid pandemic accelerated the use of IT and virtual platforms across the region and spurred the conception of 2 webinar series in the region hosted by the Centre for Medical Education (CenMED), YLL School of Medicine, NUS. A 7-part webinar series in 2021 on “Lessons learnt during the pandemic and strategies in the new normal” provided a platform for many in the region to share their experiences and best practices. This was followed in 2022 with the AMSN “Webinar series 2” which focused on key education issues using a panel discussion format. To continue the regional spirit of sharing, the Global Classroom project was developed and anchored by Siriraj Hospital to share lecture videos on the CenMED Scholar platform.

Through a process of discussion and a regional institutional survey, a set of basic medical education quality indicators for the ASEAN region was developed. The indicators were refined by a pilot application of the indicators through an internal assessment of the key member institutions. It was felt that the indicators would be useful as a benchmark for developing schools in the region. However, further developments were paused with the advent of the WFME review and use of the WFME global standards.

VI. CONCLUSION

The ASEAN Deans’ Summit represented a historic milestone in the journey towards collaborative advancement in medical education and healthcare within the ASEAN region. By bringing together leaders from across the region and establishing a structured network, the summit laid the groundwork for collective action and continuous quality improvement. The collaborative efforts initiated at this summit have the potential to significantly enhance the quality of medical education and healthcare delivery, ultimately benefiting the vast population of the ASEAN community. As the network continues to grow and evolve, it stands as a testament to the strength of diverse perspectives in the region and power of collective action in achieving shared goals and addressing common challenges.

Submitted: 8 May 2024

Accepted: 26 August 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, SP01, 8-10

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-SP01/SP003

Ari Fahrial Syam

Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia

I. INTRODUCTION

The history of medical education development in Indonesia could not be separated from the establishment of Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (FMUI) as the first medical school in the country. The name of the institution itself was established in 1950, yet the first medical school was established in 1898 under the name STOVIA (School tot Opleiding voor Indische Artsen). For more than a century, FMUI has constantly been the centre of medical education and research in Indonesia. FMUI has borne more than twenty percent of medical doctors in Indonesia which is aligned with its vision to be the centre of medical knowledge and technology so that it can contribute to national and global development (Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, 2022).

FMUI has such a complete educational program varying from medical doctor to doctorate degree. There are four masters, 32 specialist doctors, 7 subspecialists, and 3 doctorate study programs to date. FMUI also has international class study programs in collaboration with University of Melbourne, Monash University, and University of Newcastle Upon Tyne so the students are able to achieve a double degree at the end. With more than 120 active professors, more than 5,000 students per year, and more than tens of thousands alumni, FMUI stays consistent being the best medical institution in Indonesia to date. FMUI is ranked 201-250 based on QS World University Ranking by Subject Medicine 2024, 501-600 based on THE World University Ranking by Subject Clinical and Health 2024, and 588th World Rank EduRank Subject Medicine 2024 (Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, 2022).

II. ASEAN MEDICAL DEANS’ SUMMIT (AMDS)

The Southeast Asian Medical School Network Initiative is a collaboration between Medical Faculties in Southeast Asian countries to create excellence in medical education and increase biomedical research capabilities that can compete globally. To reach that goal, there are several activities such as development of harmonised curricula, collaborative networks in biomedical research, and academic exchange programs for students and faculty. Annually to discuss the progress of their goal, ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit is held annually at member faculties (ASEAN Medical School Network, 2024).

The ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS) has significance since it serves as the catalyst for advancing medical education in the member states of ASEAN in terms of quality, relevance, and accessibility. The summit helps to enhance excellence in healthcare delivery throughout the area and harmonise standards for medical education by promoting conversations on research, faculty training, curriculum development, and healthcare delivery. Additionally, it gives medical institutions a venue for networking and cooperation, creating alliances that promote innovation and progress in the field of healthcare (ASEAN Medical School Network, 2024).

III. FACULTY OF MEDICINE, UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA (FMUI) CONTRIBUTIONS

FMUI is one of the founders of ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS) which initially was established in 2012 at Faculty of Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok. Along with other deans of ten ASEAN countries, FMUI consistently participates in annual deans’ summits to establish and reinforce a network of collaborations among all participating medical schools from this region. FMUI also contributed as a host for the 5th AMDS and the 1st ASEAN Students Collaborative Project (ASCP) which was held on 26th – 28th July 2016. In this AMDS’ edition, there were several collaboration agreements on medical education and research formulation, including development of medical education curricula, academic quality assurance, prevalence disease mapping research, and initiation of various studies toward health status and policy (Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, 2016).

At that meeting, FMUI dean former, Prof. Dr. dr. Ratna Sitompul, SpM(K), also presented a report regarding the 1st ASCP event. FMUI initiated this research-based event which was done by students. This effort was done in order to encourage all medical students from 12 best universities in ASEAN to be capable of identifying their contribution in various systematic, planned, and structured community services and to collaborate in community-based research projects. The students were asked to produce a community-based project in their respective countries, thereafter assigned to create the emerging health issues mapping. It was expected that through this event, medical student collaboration in the ASEAN region would keep improving. The results of the project were then presented at the peak of the ASCP event which took place on 26-28 July 2016 at Hulu Cai Camp, Ciawi, Bogor. In general, this event was expected to be part of preparations for the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) era and increase the competitiveness of both medical education institutions and medical students as prospective medical graduates in the future. Prof Ari also become the President of the ASEAN Medical Schools Network from 2018 to 2020 (Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, 2016).

On the 12th AMDS which was held in 2023 at Universiti Malaya, FMUI Dean, Prof. Dr. dr. Ari Fahrial Syam, SpPD-KGEH presented a topic concerning ASEAN Collaborative Learning. Vice Dean Prof. Dr. dr. Dwiana Ocviyanti, SpOG(K) also participated at the meeting by presenting a topic regarding “Coaching in Learner-centered Medical Education”. (Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, 2016).

Along with FMUI contributions in AMDS, FMUI actively participated in the AAHCI Association of Academic Health Centres International. In 2023, the Executive Director of AAHCI awarded Prof. Ari with the AAHCI Distinguished Service Award for his contributions as Regional Ambassador from 2018 until 2013. FMUI also participates in the China-ASEAN Medical Education Symposium & Roundtable Discussion on Establishing China-ASEAN University Consortium on Medical Education, Research, and Healthcare, which aims to strengthen medical and health cooperation for countries along the Belt and Road Initiative.

IV. IMPACT OF FMUI’S CONTRIBUTIONS

FMUI is actively involved in the development of medical education and research in the Southeast Asia region. The real form that can be seen is the formation of the FKUI Medical Education Department which was established with the aim of becoming a centre for science, technology and culture in the field of medical education and health professions that is superior and competitive, through efforts to educate the life of the nation to improve the welfare of society so as to contribute to development. Indonesia and the world. This department also routinely publishes scientific journals which have helped the development of medical education in Indonesia (IMERI FKUI, 2022).

Furthermore, FKUI also built the Indonesian Medical Education and Research Institute (IMERI) Building as a means for academics and researchers to develop transdisciplinary research. The purpose of building this building is to answer the challenges that will arise in the future, especially in the health and medical fields. Currently, IMERI FKUI provides various facilities such as the Big Data Center, Bio Bank, Bio Informatica, Animal Research Facilities, and Molecular Biology and Proteomics Facilities (FKUI, 2021). The other form of commitment to the development of science, FKUI has published 4560 Scopus indexed publications from the last 5 years (FKUI, 2023).

V. CONCLUSION

ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit emphasises how vital it is for the medical communities of the ASEAN countries to maintain the relations between medical faculties and working together. FMUI commits to actively participate in these platforms. For the development of medical curriculum and the benefit of the people living in the ASEAN, AMDS must work together to face healthcare challenges, raise the bar for medical education, and improve healthcare delivery through collaboration, exchanging best practices, and using collective expertise.

Notes on Contributors

Ari Fahrial Syam pitched the idea, wrote the draft, and actively revised the draft. This manuscript is built on the previous collaboration and cited from the official institutional website.

Acknowledgement

No technical help and/or financial and material support or contributions were received in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

No funding source to declare.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares that there are no possible conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional, and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

ASEAN Medical School Network. (2024). About us. https://ASEANmedschool.com/index.php/about-us/

IMERI Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia. (2022). Core Facilities. https://imeri.fk.ui.ac.id

Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia. (2023). Rekapitulasi Scopus.

Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia. (2021). Departemen Pendidikan Kedokteran. https://fk.ui.ac.id/departemen/departemen-pendidikan-kedokteran.html

Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia. (2022). Sejarah. https://fk.ui.ac.id/sejarah.html

Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia. (2022). FKUI Dalam Angka. https://fk.ui.ac.id/fkui-dalam-angka.html

Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia. (2016). FKUI Tuan Rumah The 5th ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit dan The 1st ASEAN Students Collaborative Project. https://fk.ui.ac.id/berita/fkui-tuan-rumah-the-5th-ASEAN-medical-deans-summit-dan-the-1st-ASEAN-students-collaborative-project.html

*Ari Fahrial Syam

Jl. Salemba Raya No.6,

Kenari, Kec. Senen, Kota Jakarta Pusat,

Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 10430

+62 21 3929651

Email: ari.fahrial@fk.ui.ac.id

Submitted: 1 April 2024

Accepted: 20 August 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, SP01, 4-7

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-SP01/SP002

Coralie Therese Dimacali

College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Philippines

I. INTRODUCTION

The Philippine Medical School was established by virtue of a legislative act passed by the Second Philippine Commission in 1905. It opened in 1907 predating the establishment of the University of the Philippines (UP) in 1908 and the Philippine General Hospital (which is the training hospital for the school) in 1910. In 1923, the name was changed to University of the Philippines College of Medicine (UPCM) (University of the Philippines Manila, 2019).

Re-organisation of the UP led to the establishment of the UP Health Sciences Centre in 1967 to provide training and research in various health sciences. It became an autonomous member of the University of the Philippines System in 1979 and was renamed and re-organised as the University of the Philippines Manila (UPM) in 1982. The UPCM is one of nine colleges of the UPM, the others being the UP College of Nursing, UP College of Dentistry, UP College of Pharmacy, UP College of Public Health, UP College of Allied Medical Professions, UP College of Arts and Sciences in Manila, UP School for Health Sciences, and the National Teacher Training Centre for the Health Professions.

The UPCM currently has about one thousand medical students trained by 750 academic staff members while its teaching hospital, the Philippine General Hospital (PGH), caters to 600,000 patients annually. There are currently twenty-two residency and seventy-eight specialty and subspecialty fellowship training programs. The UPCM has been accredited by the Philippine Accrediting Association of Schools, Colleges, and Universities (PAASCU), the organisation tasked to visit medical schools for accreditation in the Philippines. Currently the UPCM holds a Level IV accreditation status as conferred by the Federation of Accrediting Agencies of the Philippines (FAAP) valid until 2026. It was declared a Commission on Higher Education (CHED) Centre of Excellence for Medicine in 2015, and it is due for revisit by the ASEAN University Network Quality Assurance in 2026.

II. ASEAN MEDICAL SCHOOLS NETWORK

The ASEAN Medical Schools Network (AMSN) was established in 2012 to promote collaboration among the leading medical schools in the ASEAN region to achieve excellence in medical education and healthcare, share human resources, assist one another in capacity building in medical education and research, and to work as one community as part of the ASEAN Economic Community. To this end, an annual ASEAN Medical Deans’ Summit (AMDS) has been organised and has been hosted by an ASEAN country on rotation basis. (Special Issue ASEAN Medical Schools Network) (Mahidol University, n.d.). The University of the Philippines Manila College of Medicine (UPCM) is a founding member of the AMSN and has been an active participant in this endeavour. This paper chronicles the contributions and participation of the UPCM in the AMSN.

III. ACCREDITATION

In its initial meeting, the AMSN identified four working groups: Medical Education curriculum, Medical Electives Exchange, Research and Accreditation. The UPCM volunteered to participate in the Working Group on Accreditation, which was convened by Dean Prasit Watanapa, head of the Working Group on Accreditation, in Siriraj Hospital, Thailand on July 25, 2014. Each country representative shared a presentation on the status of accreditation of medical schools in their country. After the meeting, the group representatives resolved that:

- Accreditation of medical schools ensures quality assurance.

- Each country’s representative is obliged to meet with other medical institutions within his/her respective country to disseminate information regarding this meeting.

- Presentations will be reviewed to identify common standards of accreditation for consensus.

- Each country will work towards identifying or establishing an accrediting agency for medical schools within the country.

The Accreditation Group will conduct regular meetings to share and learn how to use accreditation to leverage the standards of medical education.

As reported in the 3rd AMDS in Singapore on September 12-14, 2014, only six out of ten respondents had some form of external accreditation, five were mandatory and one was voluntary. Accreditation was mandatory for publicly funded schools and more commonly applied to postgraduate medical education. Most accreditations at that time utilised local guidelines. The World Federation for Medical Education (WFME) guidelines were not widely used. The WFME is a global organisation dedicated to enhancing the quality of medical education worldwide. WFME accreditation guarantees that the accredited medical institutes uphold the highest standards of education and training in medicine. and international medical schools would need to be accredited by an agency recognised by the WFME. During the 4th AMDS in the Philippines, the AMDS acknowledged the establishment of the Association for Medical Education Accreditation (AMEAc), an autonomous entity based in Thailand to serve as an accrediting agency for medical schools in Thailand and ASEAN countries where accreditation was not yet available. In the recent 13th AMDS in Bangkok, Thailand, the UPCM announced that the Philippine Accrediting Association of Schools, Colleges, and Universities (PAASCU), the accreditation body of medical schools in the Philippines, is now recognised by the WFME as an accrediting agency effective April 2023 to 2033 (PAASCU, 2023). Malaysia and Indonesia likewise have agencies accredited by WFME.

The UPCM was host for the 4th ASEAN Medical Deans Summit from June 23-24, 2015. During the meeting, the AMSN Charter was presented and approved by nine deans/representatives from ASEAN medical schools who were present in the meeting. Dr. Jose Cueto, member of the Board of Medicine, Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) gave a clear exposition on the challenges of harmonisation of medical schools in the ASEAN region. He emphasised that harmonisation should focus on identifying equivalence among curricular systems rather than standardisation or uniformity of curricula. The ASEAN medical school deans agreed to:

- Work towards harmonising qualifications to make educational programs comparable to allow greater mobility and exchange of professionals and students in the ASEAN region.

- Support the ASEAN Students’ Collaborative Project spearheaded by the Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia designed to improve students’ skills in developing health projects in a community within a collaborative framework.

- Recognise the importance of research on TB in the ASEAN with TRUNCATE-TB trial as lead trial, establish the ASEAN TB data base, and participate in research on dengue control.

- Establish a healthy campus initiative by generating evidence and intervention through survey of healthy lifestyle practices in campus, development of validated tools, and implementation of intervention appropriate to setting, and

- Participate in medical education research involving mapping of learning outcomes of ASEAN medical graduates, interprofessional education, and accreditation and quality assurance.

IV. MAPPING LEARNING OUTCOMES FOR ASEAN MEDICAL GRADUATES

The 5th ASEAN Medical Deans Summit was held in Bogor, West Java in Indonesia from July 26-28, 2016. Results of the first phase of the survey on Mapping out Learning Outcomes of the ASEAN medical graduates were presented. Six of seven schools had an outcome-based curriculum which was developed in varied ways, e.g., by consensus building with relevant stakeholders, through a review of health outcomes data from Ministries of Health, or as defined by a national qualification agency or higher body of education. Common learning outcomes were identified. Through a Delphi technique, these learning outcomes went through another round of comments on operational definitions, ranking according to importance and relevance, and a listing of competencies and standards for each learning outcome.

On March 28, 2018, Dr. Coralie Dimacali (UPCM) convened with Dr. Suwannee Suraseranivongse (Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University) and Dr. Cherdsak Iramaneerat (Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University) to finalise the competencies of an ASEAN medical graduate based on feedback from respondents (See Figure 1). These were then presented by Dr. Suwannee in the 7th AMDS meeting in Hanoi, Vietnam on August 23, 2018.

Figure 1. Common competencies for ASEAN Doctors (as compiled by Dr Coralie Dimacali, Dr Cherdsak Iramaneerat and Dr Suwannee Suraseranivongse)

Prior to the 6th AMDS meeting, schools were tasked to assess their medical education programs according to quality indicators developed in Thailand. Results based on eleven respondents representing ten ASEAN countries were presented in the 6th AMDS meeting held in Myanmar on July 27-28, 2017. Although the general scores were average, three areas needed improvement: Student, Curriculum and Program evaluation. They were identified as topics for discussion in subsequent AMDS meetings. The remainder of the meeting was spent on discussing updates on the Student Collaboration projects and research initiatives on tuberculosis, dengue, and healthy campus initiatives.

V. VIRTUAL PARTICIPATION

During the COVID 19 pandemic, the UPCM continued to participate in the AMSN webinar series, the Global classroom initiatives on Alzheimer’s Disease and Ischemic Heart Disease, and the AMDS virtual conference hosted by University of Cambodia with the assistance of staff from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS).

VI. SUMMARY

This article has detailed the participation of the UPCM as an active member of the ASEAN Medical Schools Network. The UPCM will host the 14th AMDS in Manila, Philippines on June 12-14, 2024.

Funding

There is no direct funding for this manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest for this publication.

References

PAASCU (2023, September 7). PAASCU is now WFME Recognized. https://paascu.org.ph/index.php/2023/04/14/paascu-is-now-wfme-recognized

Mahidol University. (n.d.). Special issue ASEAN Medical Schools Network. Mahidol University. Retrieved 2024, from https://www2.si.mahidol.ac.th/en/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Special-Issue-ASEAN-Medical-Schools-Network.pdf

University of the Philippines Manila. (2019). UP Manila catalogue of information 2019. University of the Philippines Manila.

*Coralie Therese D. Dimacali

College of Medicine,

University of the Philippines Manila,

Philippines

Email: cddimacali@up.edu.ph

Submitted: 21 June 2024

Accepted: 17 July 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 90-91

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/LE3444

Tomoko Miyoshi1,2, Masaki Chuuda3 & Fumio Otsuka2

1Center for Medical Education and Internationalization, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 2Department of General Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama University, Okayama, Japan; 3Department of Clinical Laboratory, Japanese Red Cross Okayama Hospital, Okayama, Japan

Advance care planning (ACP) enables individuals to define their goals and preferences for future treatment and care, discuss them with their families and healthcare providers, and record and review their preferences if appropriate (Rietjens, et al., 2017). In Japan, guidelines for ACP were developed in 2007, and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) promoted it. However, whether the COVID-19 pandemic, which infected many people and led to the deaths of many, affected ACP practices needs to be explored.

Before and after the pandemic, the MHLW conducted a national survey on ACP in Japan among individuals aged 20-80 years. It was found that 2.8% and 39.4% of the 2179 citizens discussed ACP in detail before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2012, whereas 3000 citizens showed a downward trend of 1.5% and 28.4% after the pandemic in 2022, respectively. The most common reason for not discussing the issue was a lack of opportunity to discuss it (62.8%), followed by lack of knowledge and not knowing what to discuss (31.0%), not feeling the need to discuss it (21.8%), and not wanting to discuss it (2.1%). The most common events that might trigger relevant discussions were family illness (54.8%), own illness (47.7%), caring for a family member (40.7%), and death of a family member (31.1%), while the spread of coronavirus infections was only 5.2%. Thus, it was found that the public may face barriers to ACP practices unless someone close to them is ill or is dying.

Cinemeducation, which uses films as a method of medical education, is one of the most effective educational strategies for medical ethics and professionalism education (Shankar, et al., 2019). In this study, we used the Cinemeducation method to conduct a public lecture on thinking about what to value in life after watching a short film on end-of-life care following the COVID-19 pandemic. Twenty people attended the lecture and 18 completed the questionnaire. Fourteen (77.8%) had previously practiced ACP, while three (16.7%) showed interest in practising it.

Hence, the COVID-19 pandemic did not motivate the public to practice ACP. This lack of ACP awareness could be mitigated by Cinemeducation for the public and encourage its practice. As the field of medical care advances and life expectancy grows, it is essential to maintain ongoing awareness and implementation of ACP to improve the quality of life.

Notes on Contributors

TM conceptualised the study, analysed the literature, and wrote the manuscript.

MC conceptualised the study and revised the manuscript.

FO conceptualised the study and revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Sun Daisuke for his lecture on ACP.

Funding

No funding was received.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Rietjens, J. A. C., Sudore, R. L., Connolly, M., van Delden, J. J., Drickamer, M. A., Droger, M., van der Heide, A., Heyland, D. K., Houttekier, D., Janssen, D. J. A., Orsi, L., Payne, S., Seymour, J., Jox, R. J., & Korfage, I. J. (2017). Definitions and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncology 18, e543-e551.

Shankar, P. R. (2019). Cinemeducation: Facilitating educational sessions for medical students using the power of movies. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 7(1), 96-103.

*Tomoko Miyoshi

Yoshida Konoe-cho,

Sakyo-ku, Kyoto City,

Japan, 606-8501

+81-75-753-9454

Email: miyoshi.tomoko.7z@kyoto-u.ac.jp

Submitted: 14 March 2023

Accepted: 22 July 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4),84-87

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/CS3263

Hooi Min Lim1, Chin Hai Teo1,2, Wei-Han Hong3, Yew Kong Lee1,2, Ping Yein Lee2 & Chirk Jenn Ng1,4,5

1Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 2E-Health Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 3Medical Education & Research Development (MERDU), Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 4Department of Research, SingHealth Polyclinics, Singapore; 5Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Recommended strategies for the development of eLearning resources have largely focused on teachers rather than students. Co-creating eLearning resources with students has received increasing attention driven by learner-centric design and dialogical learning models (Gros & López, 2016). Engaging students as co-creators is beneficial, leading to better engagement and academic performance as students take ownership of the learning experience (McDonald et al., 2021). However, challenges to engaging students as creators include the lack of clear processes, the lack of content expertise among students, students feeling threatened or uncomfortable with an unfamiliar role, power relations between learners and teachers, and teachers feeling insecure about giving up control of curricular elements.

Hackathons began as computer programming competitions which aimed to solve problems through intensive collaboration over a short time. In healthcare, they have been used to spur innovation in mHealth and surgery. In this paper, we report an innovative approach to engaging students as co-creators in eLearning resource development by using a virtual hackathon as well as the evaluation outcomes of this approach.

II. METHODS

A hackathon approach was used to develop reusable learning objects (RLOs). RLOs are open-access, interactive, multimedia web-based resources based on a single learning objective (Lim et al., 2022). A one-day hackathon was organised to create storyboards on patient safety topics. There were two phases: Stakeholder Engagement and Hackathon Day.

Phase 1 was stakeholder engagement where we engaged the university management and obtained funding support for the program. Next, we engaged the faculty’s Medical Education & Research Development Unit (MERDU), educators (as mentors) and students (as storyboard creators) to join the hackathon.

Phase 2 was the Hackathon Day was held as an online event (via Zoom) during the COVID-19 pandemic. It started with a briefing of RLO co-creation and storyboarding. Students were divided into groups to create their storyboards using an online platform called MURAL (https://www.mural.co/). The mentors were present to provide guidance. The students presented their storyboards to a panel of judges at the end.

We used a pre-post questionnaire survey method to evaluate students’ experience. The pre-hackathon questionnaire examined students’ knowledge and confidence in co-creation using Likert scale. The post-hackathon questionnaire had additional questions examining students’ perception about the hackathon using a Likert scale and open-ended questions (Appendix is available in Figshare repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26502910.v1).

All quantitative data were analysed descriptively using proportion and means. The qualitative data obtained were analysed using the thematic analysis approach. HML coded the answers to the open-ended questions and discussed with the team. The codes were then categorised into themes. Both analyses were conducted using Excel.

III. RESULTS

We reached out to 726 medical and nursing students (Appendix). 22 students participated and were assigned to 7 groups with 2 mentors per group. Seven storyboards were created (Appendix).

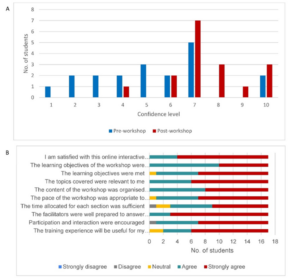

Figure 1. (A) Students’ confidence level in using the co-creation approach to develop digital educational resources (B) Students’ feedback on the hackathon

Only 15.8% (n=3) of students rated their knowledge about co-creation as ‘Good’ or ‘Excellent’ pre-hackathon compared to 82.4% (n=14) students post-hackathon. There was an increasing trend in the students’ confidence level in using the co-creation approach after the hackathon (Figure 1A). Students were satisfied with the hackathon (Figure 1B). They agreed that the learning objectives were clearly defined and met, the topics covered were relevant and the content of the hackathon was organised and easy to follow.

Students expressed their enthusiasm to be co-creators. They liked the interaction with educators and found the guidance helpful.

“Gave me the chance to build something, feels like I’m contributing something positive plus being creative for once in medical school.”

“An exciting one! Looking forward to more hackathons in the medical world, with close interaction and guidance from lecturers!”

Students liked how the online hackathon was conducted using a collaborative tool. “Awesome online tools (Mural)!”. They enjoyed the teamwork between students and educators in co-creating the storyboard.

“And I really enjoy when the teammates and facilitators come together and discuss how to make our topics better as an online learning material.”

Students expressed that they embraced the use of eLearning materials to enhance their learning. They were more encouraged to co-create and use the digital resources.

“I am more encouraged to utilise online resources to increase my knowledge.”

Students expressed that they would carry out more self-directed learning using eLearning objects and technology to strengthen their learning experience.

“I will conduct more self-directed learning and improve my technology skills for better e-learning and view e-learning as a good alternative for face-to-face teaching.”

IV. DISCUSSION

Our case study demonstrated that the hackathon method is feasible for co-creation in learning, fostering partnership between the teachers and learners and offering meaningful and fun learning experiences to the students.

Our results showed that students had an increased level of knowledge and confidence in using the co-creation approach. Students expressed their enthusiasm and appreciated the added values of co-creation in medical education as students played the role of teaching material developers, fostering a positive learning culture. The collaborative effort between teachers and students enhances mutual agreement, partnership, creativity, originality and valuable shared meaning in the development of materials (Bovill, 2020).

The RLOs co-creation process enhanced student teamwork, communication and self-directed learning. Compared to traditional methods of engaging students such as student-led teaching sessions and problem-based learning, the hackathon method added the values of joy and fun of creating learning resources that can be used by their peers. Also, co-creating eLearning resources provided an opportunity to reflect on their learning style, how they use technology as a tool to learn and how they appraise and select high-quality eLearning resources (Bringman-Rodenbarger & Hortsch, 2020).

Our case study had several limitations. The relatively short training and co-creation sessions limited the ability to develop actual RLOs. There was a small sample size with potential selection bias towards already-interested students.

V. CONCLUSION

The co-creation activity using the hackathon method can be an approach to promote interprofessional collaboration and enhance student-educator partnerships in eLearning resource development.

Notes on Contributors

All authors conceptualised and wrote the paper. HML, CHT, WHH and CJN contributed to designing methods and data collection. HML analysed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

We have obtained research ethics approval from the University Malaya Medical Centre Medical Research Ethics Committee for our case study (MREC No: 2024319-13606).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Othniel Panyih, Dr Zahiruddin Fitri Abu Hassan and Mr. Kuhan Krishnan for their assistance in conducting the hackathon. We thank all the educators and students who participated in this hackathon.

Funding

The organisation of this hackathon was funded by the Quality Management and Enhancement Centre (QMEC), Universiti Malaya.

Declaration of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

References

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creation in learning and teaching: the case for a whole-class approach in higher education. Higher Education, 79(6), 1023-1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w

Bringman-Rodenbarger, L., & Hortsch, M. (2020). How students choose e-learning resources: The importance of ease, familiarity, and convenience. FASEB BioAdvances, 2(5), 286-295. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2019-00094

Gros, B., & López, M. (2016). Students as co-creators of technology-rich learning activities in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0026-x

Lim, H. M., Ng, C. J., Wharrad, H., Lee, Y. K., Teo, C. H., Lee, P. Y., Krishnan, K., Abu Hassan, Z. F., Yong, P. V. C., Yap, W. H., Sellappans, R., Ayub, E., Hassan, N., Shariff Ghazali, S., Jahn Kassim, P. S., Nasharuddin, N. A., Idris, F., Taylor, M., … Konstantinidis, S. (2022). Knowledge transfer of eLearning objects: Lessons learned from an intercontinental capacity building project. PLOS ONE, 17(9), Article e0274771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274771

McDonald, A., McGowan, H., Dollinger, M., Naylor, R., & Khosravi, H. (2021). Repositioning students as co-creators of curriculum for online learning resources. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 102-118. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6735

*Lim Hooi Min

Department of Primary Care Medicine,

Faculty of Medicine,

Universiti Malaya

50603 Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia

Email: hmlim@ummc.edu.my

Submitted: 25 April 2024

Accepted: 29 May 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4), 88-89

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/LE3340

Virak Sorn

Faculty of Health Science and Biotechnology, University of Puthisastra, Cambodia

Dear Editor,

Healthcare professionals are crucial for achieving universal health coverage (UHC) and ensuring public health for all citizens. However, disparities in healthcare services are prevalent in rural areas, particularly in lower-middle-income countries like Cambodia. In 2021, with a population of 17 million and an annual health expenditure of $122 per capita, the country faces challenges due to an inadequate and unevenly distributed healthcare workforce. Cambodia had only 1.4 health workers per 1000 people, falling below the WHO critical shortage threshold in 2012. In addition, 3/4 of people live in rural areas, while approximately 2/4 of physicians and 3/4 of specialists work in Phnom Penh, the country’s capital (Ozano et al., 2018). This disparity results in a three-fold higher infant mortality rate in rural areas compared to urban centers.

Cambodia’s healthcare system comprises the public and private sectors, with 34 national and provincial-municipal level hospitals, 92 referral hospitals, 1222 health centers (HC), and 128 health posts. However, outpatient services utilisation is low in public sectors, while 2/4 of people seeking care from private providers (World Health Organization, 2016), highlighting the need for strengthening the public health sector through infrastructure, training, and resource allocation.

Cambodia is addressing the shortage of medical professionals by focusing on medical education and training for nurses and midwives. However, challenges persist, such as limited access to medical universities and limited training opportunities for rural healthcare workers. Many young nurses leave rural facilities due to insufficient salaries, long working hours, and challenging environments. Improvements in financial support, working conditions, and social factors are essential to retain healthcare workers in rural areas.

The Cambodian government is committed to improving healthcare access and quality, despite challenges such as high out-of-pocket expenditures and a poorly regulated private sector. Initiatives like Health Equity Funds and voucher schemes provide financial risk protection for the poor. Still, challenges remain in access to and quality of healthcare services, highlighting the need for continued efforts to enhance healthcare access.

To improve rural healthcare, investing in the referral system between public and private sectors could be a strategic approach. This would enhance collaboration and ensure that all residents, especially those in rural areas, have access to essential health services, including emergency care and NCD treatment, at their nearest HC. By prioritising investments in HC services, which include financial investments, improvements in infrastructure and training, and policy reforms, Cambodia can better care for its rural residents and move closer to achieving UHC.

Notes on Contributor

Sorn, V. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Sorn, V. would like to thank Menghourn Pin and Bella Virak, who have always provided care and support over the years.

Funding

There is no grant or funding involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Ozano, K., Simkhada, P., Thann, K., & Khatri, R. (2018). Improving local health through community health workers in Cambodia: Challenges and solutions. Human Resources for Health, 16(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0262-8

World Health Organization. (2016). Cambodia–WHO, Country Cooperation Strategy 2016–2020. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/246102/WPRO_2016_DPM_004_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

*Virak Sorn

#55, St. 184-180,

Sangkat BoeungRaing,

Khan Daun Penh,

Phnom Penh, Cambodia 12211

Faculty of Health Science and Biotechnology

University of Puthisastra

Email: viraksorn2013@gmail.com

Submitted: 28 August 2023

Accepted: 12 July 2024

Published online: 1 October, TAPS 2024, 9(4),81-83

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-4/CS3229

Tayzar Hein1, Nilar Lwin2 & Ye Phyo Aung1

1Department of Medical Education, Defence Services Medical Academy, Myanmar; 2Department of Child Health, Defence Services Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Children’s Hospital, Myanmar

I. INTRODUCTION

Portfolios, as structured collections of documentation, not only showcase a student’s learning progress and achievements but also foster a self-directed approach to assessing their own performance and setting future goal (Birgin & Adnan, 2007). Existing literature predominantly addresses the broader usage of portfolios across various disciplines, underscoring their role in enhancing reflective practice and competency-based assessments (David et al., 2001). Although portfolios in paediatrics department provide advantages, their implementation encounters substantial obstacles. These include the substantial time and effort required to maintain them, the need for clear guidelines from faculty, and a varying degree of acceptance among students and faculty, who may prefer traditional assessment methods. This study specifically aims to address these challenges by exploring the perceptions of postgraduate students on the use of portfolios in the paediatrics department at the Defence Services Medical Academy.

II. METHODS

Ethical permission for this study was granted in July 2022. The research was conducted over a six-month period from September 2022 to February 2023 within the Paediatrics Department at the Defence Services Medical Academy. To explore the experiences and perceptions of portfolio use in paediatric education, we employed purposive sampling to select six postgraduate paediatric students. We acknowledge the limitations of a small sample size. However, the focus was to gain a preliminary understanding and not to reach data saturation. The study utilised a qualitative research design (Creswell & Creswell, 2017), incorporating focus group discussions to facilitate in-depth dialogue and collect rich qualitative data. Although initially described as employing a ‘grounded theory’ approach, it is more accurate to characterise the methodology as exploratory qualitative research. Data collection involved structured focus group discussions, which were carefully designed to prompt reflection on the students’ experiences with portfolio learning. Data analysis was conducted using manual coding in conjunction with MAXQDA software, facilitating the organisation and thematic analysis of focus group transcripts.

III. RESULTS

The data analysis revealed four key themes regarding the use of portfolios in assessing competencies in the paediatrics department.

A. Theme 1: Value of Portfolios in Assessing Competencies

One participant stated, “Portfolios allowed me to reflect on my learning and track my progress towards meeting my competencies.” Another participant added, “It was helpful to have a structured way of documenting my experiences and reflecting on my strengths and areas for improvement.” The participants also noted that the use of portfolios provided an opportunity for self-directed learning and development.

B. Theme 2: Time and Effort Required

One participant stated, “It was challenging to find the time to update my portfolio regularly, especially with other demands on my time.” Another participant added, “The process of compiling evidence and reflecting on my experiences was more time-consuming than I anticipated.” The participants noted that clear guidelines and expectations were necessary to ensure the success of the portfolio assessment process.

C. Theme 3: Need for Feedback and Support

One participant stated, “I appreciated receiving feedback from my supervisors on my portfolio, as it helped me to identify areas for improvement and set goals for the future.” Another participant added, “It was helpful to have regular check-ins with my supervisors to discuss my progress and receive support and guidance.” The participants noted that faculty members needed to be trained in providing feedback and support to ensure the success of the portfolio assessment process.

D. Theme 4: Limited Impact on Career Development

One participant stated, “While portfolios were helpful in documenting my progress towards meeting my competencies, they did not have a significant impact on my career development.” Another participant added, “Portfolios were a useful assessment tool, but they did not provide me with opportunities for networking or career advancement.” The participants noted that additional career development opportunities were necessary to complement the use of portfolios.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Implications for Practice

Building on the insights from this study, the paediatrics department is encouraged to integrate portfolio assessment into its curriculum. The findings corroborate with a study who noted that portfolio use enhances self-directed learning and the documentation of competencies (Jimoyiannis & Tsiotakis, 2016). The comprehensive nature of portfolios allows students to systematically track their progress and reflect on their learning journey, fostering a deeper engagement with educational content. Implementing such assessments can not only enhance learning autonomy but also promote critical reflection among postgraduate paediatric students. This could lead to more personalised educational experiences and potentially improve competency acquisition.

B. Implications for Research

While this study provides preliminary insights into the effectiveness of portfolio assessments, it also underscores a significant gap in the literature regarding long-term impacts on learning outcomes and career progression within paediatric education. To provide a thorough assessment of the practical advantages and drawbacks of portfolio-based learning, studies could use longitudinal designs to follow the professional development of those who have participated in it.

C. Addressing Limitations and Strengthening the Argument

The study is limited by its focus on a small cohort of postgraduate students within one department, which restricts the generalisability of the findings. Moreover, the exploratory nature of the research calls for cautious interpretation. The enthusiasm and perceived benefits reported by participants align with broader educational theories emphasising active learning and continuous assessment (Trowler, 2010).

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study has provided valuable insights into the perceptions of postgraduate students on the use of portfolios in the paediatrics department. The findings suggest that portfolios can be a valuable assessment tool, but clear guidelines and expectations, as well as feedback and support from faculty members, are necessary to ensure its success.

Notes on Contributors