Supporting paediatric residents as teaching advocates: Changing students’ perceptions

Submitted: 16 October 2019

Accepted: 11 February 2020

Published online: 1 September, TAPS 2020, 5(3), 62-70

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-3/OA2204

Benny Kai Guo Loo1, Koh Cheng Thoon2, Jessica Hui Yin Tan1, Karen Donceras Nadua2 & Cristelle Chu-Tian Chow1

1General Paediatric Service, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 2Infectious Diseases Service, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Residents-as-teachers (RAT) programmes benefit both medical students and residents. However, common barriers encountered include busy clinical duties, congested lesson schedules and duty-hour regulations.

Methods: The study aimed to determine if providing a structured teaching platform and logistic support, through the Paediatric Residents As Teaching Advocates (PRATA) programme, would enhance residents’ teaching competencies and reduce learning barriers faced by medical students. The programme was held over 23 months and participated by 502 medical students. Residents were assigned as intervention group tutors and conducted bedside teachings. The evaluation was performed by medical students using paper surveys with 5-point Likert scales at the start and end of the programme.

Results: We found that students in the intervention groups perceived residents to be more competent teachers. The teaching competencies with the most significant difference were residents’ enthusiasm (intervention vs control: 4.34 vs 3.92), giving constructive feedback (4.23 vs 3.83) and overall teaching effectiveness (4.27 vs 3.89). Higher scores indicated better teaching competency. Similarly, the intervention groups perceived fewer barriers. More improvement was noted in the intervention groups with regards to busy ward work as a teaching barrier as the scores improved by 0.49, compared to 0.3 in the control groups.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that providing a structured teaching platform could enhance residents’ teaching competencies and logistic support could help overcome common barriers in RAT programmes. This combination could enhance future RAT programmes’ effectiveness.

Keywords: Paediatric, Resident-As-Teacher, Teaching Competency, Barrier, Clinical Duty, Lesson Schedule, Duty-Hour Regulation

Practice Highlights

- RAT programme with structured, dedicated teaching platforms can improve residents’ teaching competencies.

- Assigning tutor responsibilities to residents can increase their level of enthusiasm and perception of self-importance as a tutor.

- Busy work commitment, congested lesson schedules and duty-hour regulations are barriers in RAT programmes.

- Logistic support is effective in overcoming common barriers in RAT programmes.

I. INTRODUCTION

Residents play a vital role in the education of medical students. They spend up to 25% of their time teaching and research has shown that they can improve medical students’ knowledge and examination scores (McKean, & Palmer, 2015). With the shift of postgraduate medical training in Singapore to the residency system under Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education-International (ACGME-I) in 2011, teaching is recognised as an important competency for residents (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2017).

Studies have demonstrated the benefits of residents-as-teachers (RAT) programmes for both residents and medical students (Hill, Yu, Barrow, & Hattie, 2009). A controlled trial of RAT programme involving 24 obstetrics and gynaecology residents showed that their teaching skills have improved via objective structured teaching examination (Gaba, Blatt, Macri, & Greenberg, 2007). Subjectively, residents feel that teaching improves their clinical knowledge (Post, Quattlebaum, & Benich III, 2009). A successful RAT programme also enhances the students’ perception of the resident as a physician (Wamsley, Julian, & Wipf, 2004), as well as higher overall satisfaction with the clinical posting (Huynh, Savitski, Kirven, Godwin, & Gil, 2011). Furthermore, effective resident teachers can influence the students’ future career choices (Musunuru, Lewis, Rikkers, & Chen, 2007).

Although residents acknowledge that teaching is part of their duty and have the desire to teach, there are also many barriers encountered. A common problem is the heavy burden of clinical duties and lack of uninterrupted time (Wamsley et al., 2004). The limitation of time was further worsened by the introduction of duty-hour regulations (Brasher, Chowdhry, Hauge, & Prinz, 2005). The residents understandably prioritise clinical work and are exhausted after completion of clinical duties, leaving little time or energy to focus on education. Other challenges include a lack of confidence and insufficient training as an educator (Yedidia, Schwartz, Hirschkorn, & Lipkin, 1995). A survey of paediatric residents indicated that prior training in teaching can benefit the residents in teaching students (Busari, Scherpbier, Van Der Vleuten, & Essed, 2000).

A. Conceptual Framework

As learning involves knowledge organisation through the continuous addition and modification of concepts and relations over time, it is understandable that experts would have a more complex knowledge structure compared to novices (Meller, M. Chen, R. Chen, & Haeseler, 2013). The difference in knowledge structure between the experts and novices would be significant. Intermediate learners, such as paediatric residents, in this case paediatric residents, with a knowledge structure more similar to novices, would, therefore, be able to better appreciate and address the cognitive problems encountered by the medical students. Paediatric residents would be in an optimal position to minimise the distance between what the novice already knows and what needs to be learned, also referred to as the “zone of proximal development” (Ten Cate, Snell, Mann, & Vermunt, 2004).

Engaging residents as teachers utilise the principles of near-peer teaching. Social and cognitive congruence, demonstrated by Schmidt and Moust (1995), as well as Lockspeiser, O’Sullivan, Teherani, and Muller (2008), supports the near-peer teaching relationship. Social congruence enables residents to communicate with students in an informal, empathic way which in turn encourages student engagement and drives learning (Schmidt & Moust, 1995). Cognitive congruence, whereby residents have a better appreciation of students’ deficits in knowledge, enables residents to clarify problems at a level appropriate and relevant to students (Lockspeiser et al., 2008).

Utilising these principles, we have developed the RAT programme, Paediatric Residents As Teaching Advocates (PRATA), for our residents to engage in formal, structured teaching duties. The authors believe that residents can teach more effectively with a structured teaching platform, and medical students will experience fewer barriers with logistic support from RAT programme.

II. METHODS

A controlled, prospective, pre-post study was carried out at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH), Department of Paediatric Medicine, from June 2014 to April 2016. As this study was categorised as an education quality improvement, Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) indicated that formal IRB review was not required. Implied informed consent was obtained from participants during a briefing prior to the data collection.

A. Study Setting and Participants

KKH is the largest academic paediatric medical centre in Singapore, with a capacity of more than 800 inpatient beds. The paediatric residency programme also trains more than half of the paediatric residents nationwide.

Third-year medical students from the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine are attached to KKH for 1-month clinical posting as part of their paediatric training. Every batch of students consists of 6 tutorial groups and each group has 5 to 6 students. Each tutorial group is assigned to a ward team for the entire posting. The students are also required to evaluate and provide feedback on their tutors at the end of the posting.

Four to five paediatric consultants are assigned to each tutorial group as their dedicated tutors. These consultants are paediatric specialists who have completed a recognised training programme and are accredited by the Specialist Accreditation board. Every consultant has more than 3 years’ experience of teaching medical students.

All paediatric residents in their first 3 years of training (n=49) had attended workshops on “Effective Bedside Teaching using the Five-Minute Preceptor” (half-day programme with lectures and practice sessions on microteaching skills for effective clinical teaching) and “Giving Effective Feedback” (half-day programme with lectures and role-play sessions on a 4-step model for constructive feedback). These residents were invited to take part in the PRATA programme through email and participation was voluntary. Thirty-three paediatric residents (67%) participated in the PRATA programme.

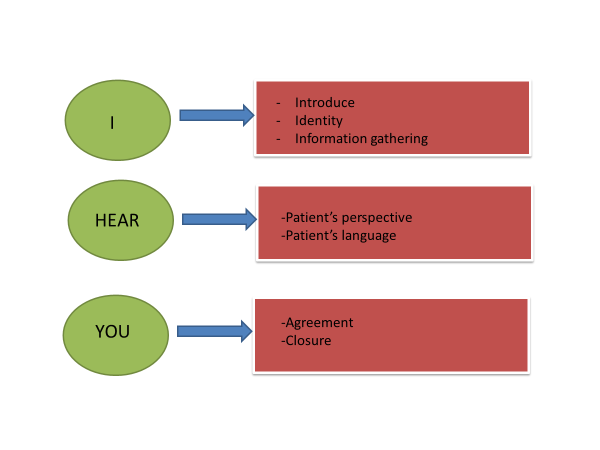

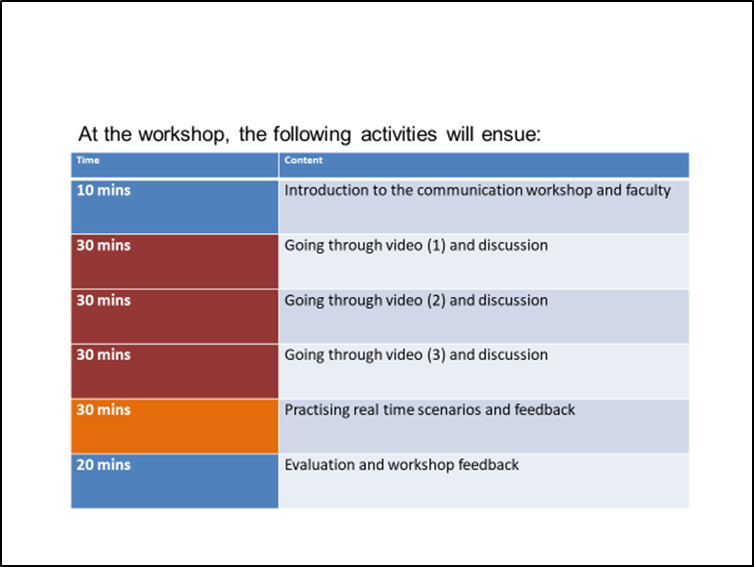

B. Study Implementation

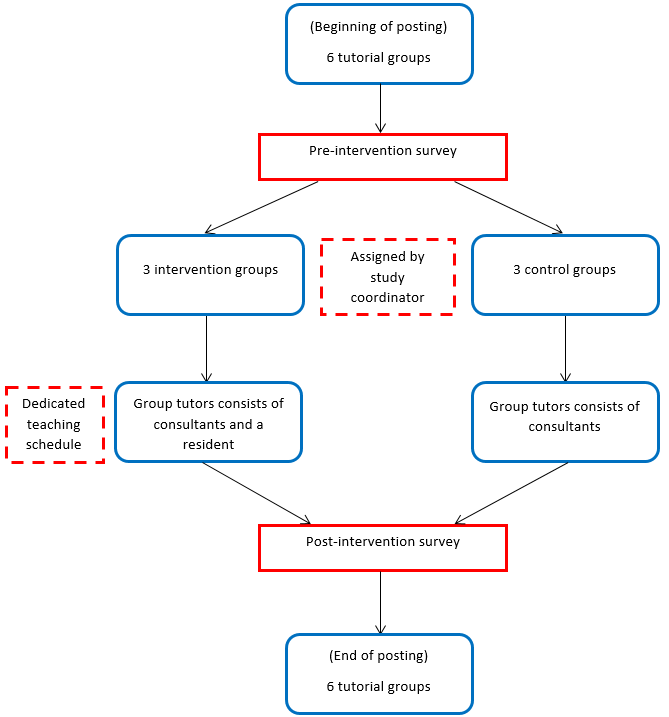

The study coordinators randomly assigned 3 medical student tutorial groups to be intervention groups and the remaining 3 groups as controls at the beginning of each posting. A total of 51 intervention and 51 control groups were assigned over 17 batches of students. The intervention included assigning 1 resident to the tutor group with a structured teaching schedule to assist with logistics coordination (Figure 1). The resident was to conduct 2 bedside teaching sessions, focusing on history taking and physical examination techniques. Two administrators from the education office were involved in the scheduling of the teaching roster according to the residents’ ward roster and work commitments, and in line with ACGME-I duty-hour restrictions. This ensured that the arrangements were specifically catered for the respective residents as they were often in different areas of work and thus have varying work commitments.

Note: A total of 17 batches of students with 51 intervention and 51 control groups participated in the programme.

Figure 1. PRATA programme protocol diagram (per batch)

For comparison, the existing teaching interactions between residents and medical students in the wards were evaluated in the control groups. As the students were attached to the same ward team for the posting, the residents in the ward team could teach the medical students. Often, these teaching sessions were unplanned, brief and limited by the burden of clinical work.

Apart from the additional resident tutor in the intervention groups, both groups of students received the same standard of medical education, comprising of the same series of planned lectures, the number of bedside tutorials by the consultants, and the duration of ward and clinic attachments.

C. Survey Forms

Paper surveys were given to all students at the beginning (9-question survey) and the end of the posting (18-question survey). These surveys were anonymised and collected by the study coordinators. The survey design was based on 2 studies by Copeland and Hewson (2000), and Hill et al. (2012). These rating instruments were chosen as they were widely used in assessing RAT programmes, applicable in a variety of clinical setting and frequently cited to date. To suit the local context, relevant questions were extracted by the study coordinators based on residents’ feedback and modified accordingly. A 5-point Likert scale was used for the questions, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. A free-text box was included for any comments on both surveys.

|

Effectiveness of Resident Teaching |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

My medical knowledge and/or clinical skills have improved significantly during the clerkship after being taught by residents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

We received adequate teaching from residents during the clerkship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident established a good learning environment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident stimulated me to learn independently |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident offered regular and constructive feedback (both positive and negative) in a timely manner and in an appropriate setting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident clearly specified what we were expected to know and do for the tutorial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident was able to adjust the teaching according to my needs (experience, competence, interest) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident asked questions that promoted learning (e.g. clarification, reflective questions) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident gave clear explanations or reasons for his/her opinions, advice and actions etc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident was able to effectively coach me on my clinical skills |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident taught or demonstrated effective patient and/or family communication skills |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The residents are enthusiastic about teaching |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resident made teaching relevant to patient care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overall, the resident was an effective teacher |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Barriers to Resident Teaching |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

Ward work was too busy and residents had no time for teaching |

|

|

|

|

|

|

There were too many lectures and tutorials outside of the ward to allow for resident teaching |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal Impact of Resident Teaching |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|

The resident tutor was a positive role model for me |

|

|

|

|

|

|

After being taught and interacting with my resident teacher, it would make me more likely consider/select Paediatrics as my choice for future residency training |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Any other comments:

|

The pre-programme survey (Appendix) asked the students about their expectations of residents as teachers, as well as the perceived barriers to receiving resident teachings. The post-programme survey (Table 1) focused on the students’ evaluation of residents’ teaching competencies, the impact of resident teachings and the barriers encountered. For the post-programme survey, the intervention groups evaluated the resident from their tutor group, whereas the control groups evaluated the resident from the ward team.

D. Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean scores with standard deviations. For questions about residents’ teaching competencies, post-programme differences were evaluated between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. For questions on barriers to receiving resident teachings, pre and post-programme differences were evaluated within and between groups using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and the Mann-Whitney U test respectively. A p-value of less than 0.05 was taken to be significant for all tests. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.

III. RESULTS

A. Participant Demographics

A total of 502 medical students from 17 batches participated in the PRATA programme over 23 months. Overall, there was 100% pre-programme and 81% (410 students) post-programme participation. The post-programme participation was 74% in the control group and 88% in the intervention group. The baseline demographics were comparable between the groups.

B. Resident Teaching Competencies

A higher score indicated better teaching competency. The intervention group students gave significantly better scores across all aspects for the residents’ teaching competencies as compared to the control groups (Table 2). The biggest difference was noted in the question of the enthusiasm shown by the residents. The intervention groups scored 4.34 and the control groups scored 3.92. The next greatest difference was from the question of residents giving regular and constructive feedback. The scores for the intervention and control groups were 4.23 and 3.83 respectively. The overall assessment of residents as effective teachers showed a similar trend as the intervention groups scored 4.27 and the control groups scored lower at 3.89. The differences in these competencies were all statistically significant.

|

Post-programme survey questions on resident teaching competencies |

Control (n = 188) |

Intervention (n = 222) |

P# |

|

Mean* (SD) |

Mean* (SD) |

||

|

My medical knowledge and/or clinical skills have improved significantly during the clerkship after being taught by residents |

3.92 (0.53) |

4.05 (0.65) |

0.01 |

|

We received adequate teaching from residents during the clerkship |

3.62 (0.79) |

3.94 (0.75) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident established a good learning environment |

3.94 (0.59) |

4.27 (0.57) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident stimulated me to learn independently |

3.88 (0.61) |

4.10 (0.62) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident offered regular and constructive feedback (both positive and negative) in a timely manner and in an appropriate setting |

3.83 (0.66) |

4.23 (0.61) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident clearly specified what we were expected to know and do for the tutorial |

3.72 (0.68) |

4.09 (0.68) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident was able to adjust the teaching according to my needs (experience, competence, interest) |

3.91 (0.64) |

4.22 (0.66) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident asked questions that promoted learning (e.g. clarifications, probes, reflective questions) |

3.94 (0.62) |

4.24 (0.61) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident gave clear explanations or reasons for his/her opinions, advice and actions etc. |

3.95 (0.58) |

4.28 (0.58) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident was able to effectively coach me on my clinical skills |

3.84 (0.68) |

4.17 (0.65) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident taught or demonstrated effective patient and/or family communication skills |

3.89 (0.69) |

4.20 (0.62) |

<0.01 |

|

The residents are enthusiastic about teaching |

3.92 (0.65) |

4.34 (0.67) |

<0.01 |

|

The resident made teaching relevant to patient care |

3.90 (0.61) |

4.26 (0.59) |

<0.01 |

|

Overall, the resident was an effective teacher |

3.89 (0.63) |

4.27 (0.67) |

<0.01 |

Note: *Higher mean score indicates better competency.

#Mann-Whitney U test used for between-group comparisons.

Table 2. Results of survey questions relating to resident teaching competencies

C. Barriers to Resident Teachings

A lower mean score indicated less significant barrier to receiving resident teachings. Generally, the mean scores on barriers reported by the intervention groups decreased more than the control groups after the programme. For the question on busy ward work as a barrier for residents to teach, both groups started with the same mean score of 3.52. At the end of the posting, more improvement was noted in the intervention groups as the mean score decreased to 3.03, as compared to 3.22 in the control groups. Although the difference was statistically significant within the groups, it was not significant when comparing the post-programme difference between the groups (Table 3). For the question about too many lectures and tutorials as a barrier for students to attend resident teachings, the score decreased from 2.90 to 2.59 in the intervention groups. In contrast, the scored increased from 2.90 to 3.07 in the control groups, which meant that the barrier remained significant throughout their posting. The difference in the intervention groups and the post-programme difference between the groups were both statistically significant (Table 3).

|

Survey questions on barriers to resident teaching |

Control group (n = 188) |

Intervention group (n = 222) |

Control vs Intervention |

||||

|

Pre-programme Mean* (SD) |

Post-programme Mean* (SD) |

Pre-Post Difference P# |

Pre-programme Mean* (SD) |

Post-programme Mean* (SD) |

Pre-Post Difference P# |

Post Difference P^ |

|

|

Ward work was too busy and residents had no time for teaching |

3.52 (0.81) |

3.22 (0.89) |

<0.01 |

3.52 (0.79) |

3.03 (1.01) |

<0.01 |

0.42 |

|

There were too many lectures and tutorials outside of the ward to allow for resident teaching |

2.90 (0.76) |

3.07 (0.87) |

0.31 |

2.90 (0.82) |

2.59 (0.95) |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

Note: *Lower mean score indicates less severe barrier.

#Wilcoxon signed-rank test used for within-group comparisons.

^Mann-Whitney U test used for between-group comparisons.

Table 3. Results of survey questions relating to barriers to receiving resident teachings

IV. DISCUSSION

RAT programmes have demonstrated improvement in residents’ teaching competencies and contribute significantly to the education of medical students (Hill et al., 2009). Although barriers to resident teachings such as excessive workload and duty hour regulations have been identified (Wamsley et al., 2004), there is limited literature on overcoming these obstacles in RAT programmes.

The main aims of the PRATA programme are to provide paediatric residents with a structured teaching platform to improve their teaching competencies and logistic support to overcome common barriers in RAT programmes. The residents in the PRATA programme had the added elements of a dedicated environment for teaching and assuming the role and responsibility as a teaching faculty. The education office also provided these residents with logistic support to reduce scheduling conflicts and duty-hour violations.

This study revealed that the PRATA programme improved the students’ perceptions of the residents’ teaching competencies. This is consistent that RAT programmes enhance resident teaching skills (Zackoff, Jerardi, Unaka, Sucharew, & Klein, 2015). The residents in the intervention groups achieved higher scores in all teaching competency domains, and this included innate characteristics (displaying enthusiasm), techniques (giving constructive feedback) and bedside skills (demonstrating effective communication). A higher score indicated better proficiency in that domain. Although both groups of residents were equipped with the same set of teaching skills, those in the PRATA programme were provided with a structured teaching platform as compared to the unpredictable and potentially chaotic ward setting in the control groups. Furthermore, assigning the residents responsibility as the group tutors possibly increased their level of enthusiasm and perception of self-importance as a tutor. Our study demonstrated that residents in RAT programmes that provide structure to apply their teaching skills can be perceived as better educators.

The results also showed that students from both student groups were very worried about the barriers to receiving resident teachings before the programme. They were more concerned about the residents’ busy work commitments as compared to their congested lesson schedules. Our programme was able to reduce the impact of these barriers as both scores improved significantly in the intervention groups. In contrast, the control groups continued to perceive after the posting that their lesson schedules did not permit residents to teach. Overall, the students from the intervention groups seemed to have a more positive learning experience as there were 20% more students who considered working in Paediatric Medicine in the future. The PRATA programme highlighted that logistic support was an important factor to decrease the students’ concerns of these barriers, which could impede them seeking learning opportunities from the residents.

We have identified some limitations of our study. Firstly, the residents participated in the programme voluntarily, therefore we could have recruited residents who were more passionate or more experienced in teaching. Therefore, we aim to recruit all residents and stratify them by their level of training for the subsequent studies. Secondly, there was no standardisation of the teaching topics. The residents in the intervention groups could have taught in the areas they were more confident in, whereas the residents in the control group could only teach about the patients in the ward. For future studies, we can assign the same teaching topics when evaluating the residents’ teaching competencies. Lastly, the improvement of scores in the intervention groups, although statistically significant, can be complex to interpret in the practical setting. A qualitative study on these aspects can give more insight, such as the specific traits or techniques that residents in the programme displayed, or the practical burden of the barrier on the students’ learning.

V. CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that providing a structured teaching platform could enhance residents’ teaching competencies. This was an important factor as existing resident teachings commonly occur while performing clinical work and in the chaotic ward setting. The study also showed that logistic support could help overcome common barriers in RAT programmes, such as busy work commitments. We believe this combination is important to include in future RAT programmes.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Benny Kai Guo Loo is an Associate Consultant in General Paediatric Service at KK Women’s and Children’s hospital. He has a keen interest in medical education and is currently a Co-ordinator for Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, NUS and Physician Faculty for Singhealth Paediatric Residency Programme.

A/Prof Koh Cheng Thoon is the Head and Senior Consultant of Infectious Diseases Service at KK Women’s and Children’s hospital. He is also the Academic Vice-Chair for Education in Singhealth Duke-NUS Paediatric Academic Clinical Programme and he was awarded the Wong Hock Boon Society-SMA Charity Fund Outstanding Mentor Award in 2016.

Dr Jessica Hui Yin Tan is a Senior Resident in General Paediatrics Service at KK Women’s and Children’s hospital. She is also a clinical lecturer at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, NUS.

Dr Karen Donceras Nadua is an Associate Consultant in Infectious Diseases Service at KK Women’s and Children’s hospital. She is also a clinical teacher at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine.

Dr Cristelle Chu-Tian Chow is a Consultant in General Paediatrics Service at KK Women’s and Children’s hospital. She obtained her Master of Health Professions Education from Maastricht University and is currently the Associate Programme Director for Singhealth Paediatric Residency Programme.

Ethical Approval

The study was categorised as an education quality improvement hence formal Singhealth Centralised Institutional Board review is not required.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Paediatric Graduate Medical Education and Academic Clinical Programme secretariat, faculty and residents who have helped to make PRATA programme a success. We would also like to thank Prof Sandy Cook, Senior Associate Dean in Duke-NUS, for her guidance in the writing of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors report no funding source for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (2017). Common program requirements. Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf.

Brasher, A. E., Chowdhry, S., Hauge, L. S., & Prinz, R. A. (2005). Medical students’ perceptions of resident teaching: Have duty hours regulations had an impact? Annals of Surgery, 242(4), 548.

Busari, J. O., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Essed, G. E. (2000). Residents’ perception of their role in teaching undergraduate students in the clinical setting. Medical Teacher, 22(4), 348-353.

Copeland, H. L., & Hewson, M. G. (2000). Developing and testing an instrument to measure the effectiveness of clinical teaching in an academic medical center. Academic Medicine, 75(2), 161-166.

Gaba, N. D., Blatt, B., Macri, C. J., & Greenberg, L. (2007). Improving teaching skills in obstetrics and gynecology residents: Evaluation of a residents-as-teachers program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 196(1), 87-e1.

Hill, A. G., Srinivasa, S., Hawken, S. J., Barrow, M., Farrell, S. E., Hattie, J., & Yu, T. C. (2012). Impact of a resident-as-teacher workshop on teaching behavior of interns and learning outcomes of medical students. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 4(1), 34-41.

Hill, A. G., Yu, T. C., Barrow, M., & Hattie, J. (2009). A systematic review of resident‐as‐teacher programmes. Medical Education, 43(12), 1129-1140.

Huynh, A., Savitski, J., Kirven, M., Godwin, J., & Gil, K. M. (2011). Effect of medical students’ experiences with residents as teachers on clerkship assessment. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 3(3), 345-349.

Lockspeiser, T. M., O’Sullivan, P., Teherani, A., & Muller, J. (2008). Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: The value of social and cognitive congruence. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 13(3), 361-372.

McKean, A. J. S., & Palmer, B. A. (2015). Psychiatry resident-led tutorials increase medical student knowledge and improve national board of medical examiners shelf exam scores. Academic Psychiatry, 39(3), 309-311.

Meller, S. M., Chen, M., Chen, R., & Haeseler, F. D. (2013). Near-peer teaching in a required third-year clerkship. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 86(4), 583.

Musunuru, S., Lewis, B., Rikkers, L. F., & Chen, H. (2007). Effective surgical residents strongly influence medical students to pursue surgical careers. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 204(1), 164-167.

Post, R. E., Quattlebaum, R. G., & Benich III, J. J. (2009). Residents-as-teachers curricula: A critical review. Academic Medicine, 84(3), 374-380.

Schmidt, H. G., & Moust, J. H. (1995). What Makes a Tutor Effective? A Structural Equations Modelling Approach to Learning in Problem-Based Curricula. Academic Medicine, 70(8), 708-714

Ten Cate, O., Snell, L., Mann, K., & Vermunt, J. (2004). Orienting teaching toward the learning process. Academic Medicine, 79(3), 219-228.

Wamsley, M. A., Julian, K. A., & Wipf, J. E. (2004). A literature review of “resident-as-teacher” curricula. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(5), 574-581.

Yedidia, M. J., Schwartz, M. D., Hirschkorn, C., & Lipkin, M. (1995). Learners as teachers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 10(11), 615-623.

Zackoff, M., Jerardi, K., Unaka, N., Sucharew, H., & Klein, M. (2015). An observed structured teaching evaluation demonstrates the impact of a resident-as-teacher curriculum on teaching competency. Hospital Paediatrics, 5(6), 342-347.

*Benny K. G. Loo

Division of Paediatric Medicine

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 229899

Tel: +65 62255554

Email: benny.loo.k.g@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 7 July 2019

Accepted: 30 January 2020

Published online: 1 September, TAPS 2020, 5(3), 54-61

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-3/OA2170

Kieng Wee Loh1, Jerome Ingmar Rotgans2, Kevin Tan3, Nigel Choon Kiat Tan3

1National Healthcare Group, Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore; 2Office of Medical Education, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; 3Office of Neurological Education, Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Clinical reasoning is the cognitive process of weighing clinical information together with past experience to evaluate diagnostic and management dilemmas. There is a paucity of literature regarding predictors of clinical reasoning at the postgraduate level. We performed a retrospective study on internal medicine residents to determine the sociodemographic and experiential correlates of clinical reasoning in neurological localisation, measured using validated tests.

Methods: We recruited 162 internal medicine residents undergoing a three-month attachment in neurology at the National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore, over a 2.5 year period. Clinical reasoning was assessed on the second month of their attachment via two validated tests of neurological localisation–Extended Matching Questions (EMQ) and Script Concordance Test (SCT). Data on gender, undergraduate medical education (local vs overseas graduates), graduate medical education, and amount of clinical experience were collected, and their association with EMQ and SCT scores evaluated via multivariate analysis.

Results: Multivariate analysis indicated that local graduates scored higher than overseas graduates in the SCT (adjusted R2 = 0.101, f2 = 0.112). Being a local graduate and having more local experience positively predicted EMQ scores (adjusted R2 = 0.049, f2 = 0.112).

Conclusion: Clinical reasoning in neurological localisation can be predicted via a two-factor model–undergraduate medical education and the amount of local experience. Context specificity likely underpins the process.

Keywords: Clinical Reasoning, Context Specificity, Extended Matching Questions, Neurological Localization, Script Concordance Test

Practice Highlights

- Clinical reasoning is a combination of two concurrent processes–pattern recognition in familiar circumstances (illness scripts); and deliberate analysis in unfamiliar scenarios (hypothetico-deductive approach).

- Validated tools exist to assess aspects of clinical reasoning–Script Concordance Tests (SCTs) for illness scripts; and Extended Matching Questions (EMQs) for hypothetico-deductive reasoning.

- Doctors who (a) were educated locally; and (b) worked locally for a longer period, tend to reason more similarly to local expert clinicians in the area of neurological localization.

- Development of clinical reasoning in neurology appears to be specific to a given clinical context

- To optimize the development of clinical reasoning in neurology, internal medicine residency programmes could consider maximizing trainees’ exposure to the local medical context before rotating them to a neurology posting.

I. INTRODUCTION

Clinical reasoning is the cognitive process of integrating and weighing clinical information together with past experiences to evaluate diagnostic and management dilemmas (Monteiro & Norman, 2013). Together with an appropriate knowledge base, this is central to clinical competence (Elstein, Shulman, & Sprafka, 1990; Groen & Patel, 1985), Clinical reasoning is especially important for the skill of neurological localisation (Gelb, Gunderson, Henry, Kirshner, & Jozefowicz, 2002; Nicholl & Appleton, 2015), which involves interpreting clinical signs and symptoms to identify the site of neuroanatomical abnormalities–a crucial first step in making a neurologic diagnosis. Accurate clinical reasoning is an important core competency (Connor, Durning & Rencic, 2019), and is essential in minimising diagnostic errors (Durning, Trowbridge, & Schuwirth, 2019).

The ‘dual process’ paradigm of clinical reasoning proposes that a combination of rapid intuition and deliberate analysis is employed in clinical decision making (Elstein, 2009; Eva, 2005; Monteiro & Norman, 2013). In familiar circumstances, relevant clinical information is compared with past experiences to arrive at a diagnosis (Elstein, 2009), akin to pattern recognition. This content-specific knowledge is organised into mental networks (‘illness scripts’) for easy retrieval (Boushehri, Arabshahi, & Monajemi, 2015; Norman, Young, & Brooks, 2007). In unfamiliar situations, however, a ‘hypothetico-deductive’ approach is utilised instead, where hypotheses are formulated through conscious deliberations and later tested (Boushehri et al., 2015; Elstein, 2009; Monteiro & Norman, 2013). These reasoning processes work in parallel, but experts are more adept at switching between both approaches whilst maintaining a higher performance level in each (Boushehri et al., 2015; Eva, 2005; Monteiro & Norman, 2013).

Several studies have examined predictors of academic performance in medical undergraduates (Ferguson, James, & Madeley, 2002; Hamdy et al., 2006; Kanna, Gu, Akhuetie, & Dimitrov, 2009). Previous studies have examined sociodemographic characteristics and educational background as potential predictors, as these have practical relevance in reviewing admission criteria and teaching methods for undergraduate programmes. Female gender (Adams et al., 2008; Ferguson et al., 2002; Guerrasio, Garrity, & Aagaard, 2014; Stegers-Jager, Themmen, Cohen-Schotanus, & Steyerberg, 2015; Woolf, Haq, McManus, Higham, & Dacre, 2008), ethnic majority status (Stegers-Jager et al., 2015; Vaughan, Sanders, Crossley, O’Neill, & Wass, 2015; Woolf, Cave, Greenhalgh, & Dacre, 2008; Woolf & Haq et al., 2008; Woolf, Potts, & McManus, 2011) and older age (Kusurkar, Kruitwagen, Ten Cate, & Croiset, 2010) were found to be significant predictors; educational background (Kusurkar et al., 2010) and past academic performance (Ferguson et al., 2002; Hamdy et al., 2006; Kanna et al., 2009; Stegers-Jager et al., 2015; Woloschuk, McLaughlin, & Wright, 2010) also showed positive associations. However, academic performance does not solely reflect reasoning skill, especially in postgraduates (Woloschuk et al., 2010; Woloschuk, McLaughlin, & Wright, 2013).

The ‘dual process’ theory also identifies clinical experience as important for clinical reasoning, especially in the formation of illness scripts (Elstein, 2009; Eva, 2005; Monteiro & Norman, 2013). Yet this is seldom explored, with few studies on postgraduates, a group where clinical experience might be more relevant.

The current Singapore postgraduate training system is based on the United States’ residency system (Huggan et al., 2012). Medical graduates, whether local or overseas-trained, must first register with the Singapore Medical Council (SMC) to start practising medicine locally. They can then apply for graduate medical education programmes (‘residency’) in various sponsoring institutions to train in a speciality; residency entry can occur immediately after or several years after graduation.

In Singapore, internal medicine residents rotate between subspecialty departments (such as cardiology or neurology) in no fixed order, hence two residents rotated to neurology may differ in the amount of working experience as a resident, as a clinician practising locally, and as a doctor in general. Moreover, experiences may differ between the various sponsoring institutions, and also between disparate undergraduate medical programmes. These differences might influence clinical reasoning.

Additionally, most Singaporean male graduates defer their medical careers to complete a two-year stint with the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), as part of their compulsory National Service. Within the SAF, medicine is rarely practised in conventional clinical settings, and the quality of clinical experience may be affected. Clinical experience may hence differ between genders.

Several instruments have been designed to assess clinical reasoning (Amini et al., 2011; Boushehri et al., 2015), but these were infrequently used in studies (Groves, O’rourke, & Alexander, 2003; Postma & White, 2015). Some studies utilised unvalidated questionnaires (Groves et al., 2003); others did not specifically assess clinical reasoning (Postma & White, 2015). Moreover, the focus of each instrument varies–Extended Matching Questions (EMQ; Beullens, Struyf, & Van Damme, 2005) on ‘hypothetico-deductive’ reasoning; Script Concordance Test (SCT; Lubarsky, Charlin, Cook, Chalk, & van der Vleuten, 2011) on illness scripts (Amini et al., 2011; Boushehri et al., 2015). As both approaches are complementary, it may thus be prudent to employ multiple instruments to better evaluate clinical reasoning as an outcome measure, especially for the important skill of neurological localisation (Gelb et al., 2002; Nicholl & Appleton, 2015).

Given the gaps in the extant literature, we thus aimed to determine predictors of postgraduate performance in clinical reasoning tests, within the context of neurological localisation.

II. METHODS

A. Subjects

Subjects comprised 162 internal medicine residents from two sponsoring institutions (National Healthcare Group and Singapore Health Services). Each resident completed a three-month neurology rotation at the National Neuroscience Institute (NNI), Singapore, from January 2014 to June 2016. Waiver of further ethical deliberation was granted by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) for this education program improvement project; subjects were anonymised and implied informed consent was obtained from all participants. We excluded 17 subjects who failed to complete the required assessments, leaving 145 (90%) subjects for eventual analysis.

B. Predictor Variables

We investigated three sociodemographic characteristics–gender, undergraduate medical education (UME) and graduate medical education (GME). UME denotes the location of undergraduate training institution, and was classified into local (Singapore) and overseas. GME refers to the residency programmes of the two sponsoring institutions, anonymised as ‘A’ and ‘B’.

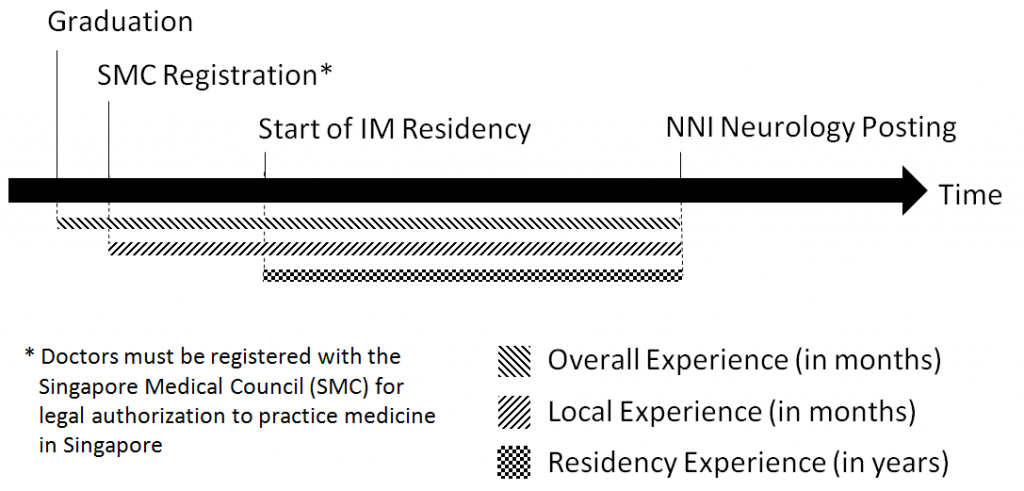

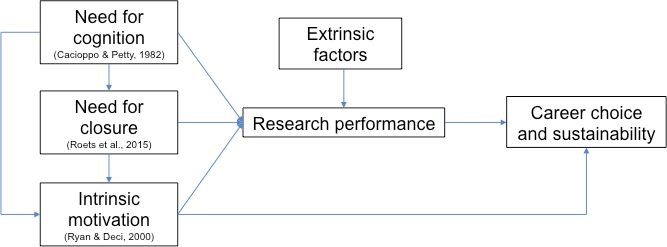

Clinical experience was judged by three metrics–overall experience (OE), local experience (LE) and residency experience (RE; Figure 1). OE and LE were calculated as the number of months from graduation and SMC registration respectively, to the month of test attempt. RE, defined as the residency training year, was categorised as ‘Year 1’, ‘Year 2’ and ‘Year 3’.

Figure 1. Measures of clinical experience

We obtained data on gender, GME and RE from our institution records; UME and month of SMC registration were obtained from the SMC Registry of Doctors. Graduation month was derived from our institution records for local graduates and estimated for overseas graduates from the dates of their alma mater’s most recent graduation ceremony, available online.

C. Outcome Measures

We used two validated methods of assessment, Script Concordance Test (SCT; Lubarsky et al., 2011) and Extended Matching Questions (EMQ; Beullens et al., 2005), to evaluate clinical reasoning in neurological localisation. We specifically selected the SCT and EMQ tests that had previously demonstrated construct validity and reliability in our Singapore context (Tan, Tan, Kandiah, Samarasekera, & Ponnamperuma, 2014; Tan et al., 2017).

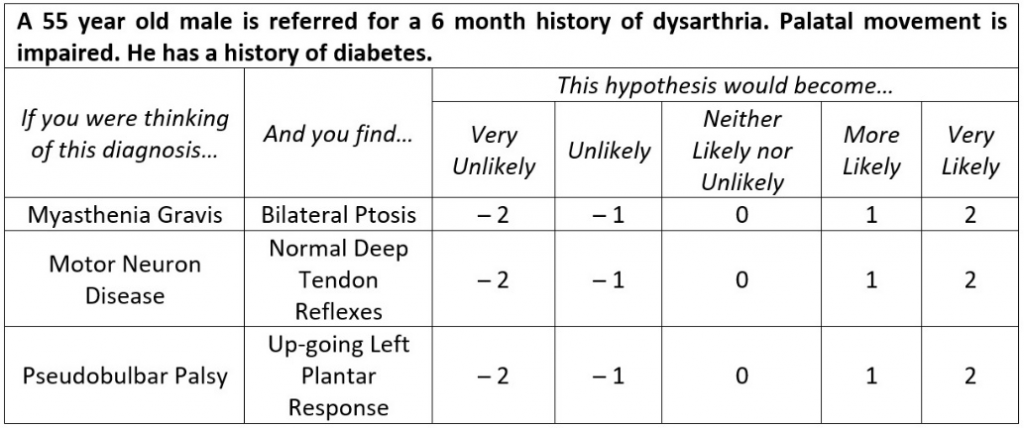

An SCT contains case scenarios with 3-5 part questions (Fournier, Demeester, & Charlin, 2008; Figure 2)–a relevant diagnostic or management option; a new clinical finding; and a five-point Likert Scale indicating the new finding’s effect on the initial option. A scoring key is derived from scores by an expert panel; subsequent test-takers are then scored for degree of concordance to the experts (Fournier et al., 2008; Wan, 2015).

Our locally-validated SCT (Tan et al., 2014) contained 14 scenarios, each with 3–5 question items, totalling 53 items; reliability and generalisability were acceptable (Cronbach α 0.75, G-coefficient 0.74). Questions and scoring keys were derived from local experts. We analysed only the neurological localisation component (7 scenarios).

Figure 2. Script Concordance Test (SCT)–Sample questions (Tan et al., 2017)

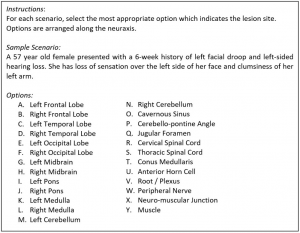

EMQs are multiple-choice questions consisting of case scenarios, each with a single answer drawn from a shared list of at least 7 options (Case & Swanson, 1993; Fenderson, Damjanov, Robeson, Veloski, & Rubin, 1997). Our locally-validated EMQ (Tan et al., 2017) contained 45 scenarios with a shared answer list of 25 options (Figure 3); reliability and generalisability were excellent (Cronbach α 0.85, G-coefficient 0.85).

Figure 3. Extended Matching Questions (EMQ)–Sample questions (Tan et al., 2014)

Subjects completed both timed closed-book tests via an online portal during the second month of their three-month neurology rotation, done as a formative assessment. Scores were expressed in percentages. Subjects had no prior exposure to the SCT or EMQ during their neurology rotation or as practising doctors, and were introduced to the test format on the day of assessment. One worked example of the SCT and EMQ was provided to the subjects before the test.

D. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to test assumptions of normality before proceeding with multivariate analysis. We used SPSS Statistics version 20, and considered p-values <0.05 as statistically significant; all tests were two-tailed.

Multivariate stepwise linear regression models were used to assess the relationship between predictor variables (gender, UME, GME, OE, LE and RE) and outcome measures (SCT and EMQ scores). Tolerance values were computed to assess multicollinearity, with values below 0.60 considered problematic (Chan, 2004). Overall model performance was assessed using Nagelkerke’s R2, and effect sizes measured with Cohen’s f2. Effect sizes of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 were considered low, medium and large respectively (Cohen, 1988).

III. RESULTS

The majority of the 145 subjects were female, local graduates and belonged to residency ‘B’ (Table 1).Mean and standard deviation of SCT and EMQ scores were 68.03 ± 8.24% and 81.84 ± 12.17% respectively. Population statistics did not reveal a need for non-parametric tests.

|

|

|

n |

% |

|

Sociodemographic Characteristics |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

61 |

42.07 |

|

Female |

84 |

57.93 |

|

|

Undergraduate Medical Education (UME) |

Local |

87 |

60.00 |

|

Overseas |

58 |

40.00 |

|

|

Graduate Medical Education (GME) |

Residency ‘A’ |

46 |

31.72 |

|

Residency ‘B’ |

99 |

68.28 |

|

|

Clinical Experience (months)* |

|||

|

Overall Experience (OE) |

38.34 ± 21.32 |

||

|

Local Experience (LE) |

33.43 ± 16.50 |

||

|

Residency Experience (RE) |

Year 1 |

55 |

37.93 |

|

Year 2 |

55 |

37.93 |

|

|

Year 3 |

35 |

24.14 |

|

|

Test Scores (%)* |

|||

|

Script Concordance Test (SCT) |

68.03 ± 8.24 |

||

|

Extended Matching Question (EMQ) |

81.84 ± 12.17 |

||

|

* Values expressed in Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|||

Table 1. Characteristics of subject population (n = 145)

Since both EMQ and SCT assess clinical reasoning, albeit different aspects, their inclusion in Multivariate analysis (Table 2, Model A) were potentially contentious. Additional models excluding these were therefore created (Model B).

|

Model |

Outcome |

Co-Variable |

B |

95% CI‡ |

SE |

Sig. |

Adjusted R2 |

f2 |

|

1A |

SCT Score |

UME* |

4.5 |

2.0 – 7.0 |

1.3 |

0.001 |

0.204 |

0.256 |

|

EMQ Score |

0.2 |

0.1 – 0.3 |

0.1 |

< 0.001 |

||||

|

1B |

SCT Score |

UME |

5.5 |

2.9 – 8.1 |

1.3 |

< 0.001 |

0.101 |

0.112 |

|

2A |

EMQ Score |

LE† |

0.1 |

0.0 – 0.2 |

0.1 |

0.025 |

0.164 |

0.196 |

|

SCT Score |

0.5 |

0.3 – 0.8 |

0.1 |

< 0.001 |

||||

|

2B |

EMQ Score |

UME |

4.7 |

0.7 – 8.7 |

2.0 |

0.021 |

0.049 |

0.052 |

|

LE |

0.1 |

0.0 – 0.2 |

0.1 |

0.041 |

||||

|

* Undergraduate Medical Education, Overseas (reference) vs Local (comparator) † Local Experience ‡ All Tolerance values >0.89 |

||||||||

Table 2. Multivariate correlation of outcome measures with predictor variables

Local graduates and better EMQ performers tended to have higher SCT scores (adjusted R2 = 0.204, f2 = 0.256; Model 1A). Residents with more local experience and higher SCT scores also had higher EMQ scores (adjusted R2 = 0.164, f2 = 0.196; Model 2A).

In the additional models, UME remained as the sole association for SCT scores (adjusted R2 = 0.101, f2 = 0.112; Model 1B). However, UME became significant for EMQ scores (adjusted R2 = 0.049, f2 = 0.052), with local graduates scoring higher (Model 2B).

IV. DISCUSSION

As there is a paucity of literature about postgraduate performance in clinical reasoning, this study provides a unique opportunity to evaluate its predictors, especially clinical experience. We used validated instruments to measure clinical reasoning skills in neurological localisation, and elucidated multivariate associations between clinical reasoning, clinical experience, and sociodemographic characteristics of our subjects.

Our results suggest that local graduates tend to score better in both clinical reasoning tests. Consistent with the existing literature (Postma & White, 2015), this indicates that educational background plays an important role in the development of clinical reasoning skills. Since SCT performance reflects the degree of concordance with verdicts made by local experts (Tan et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2017), this suggests that being educated locally may promote a similar outcome of reasoning. It is also possible that local undergraduate programmes provide better training in neurological localisation, as local graduates performed better in the EMQ, an instrument where scoring is independent of local experts’ views.

Interestingly, we found no significant associations between clinical experience and SCT performance. The accumulation of context-specific experiential knowledge is crucial for developing effective illness scripts (Elstein, 2009), hence SCT scores were expected to rise with increasing clinical experience (Boushehri et al., 2015; Kazour, Richa, Zoghbi, El-Hage, & Haddad, 2017; Lubarsky, Chalk, Kazitani, Gagnon, & Charlin, 2009; Norman et al., 2007). However, heuristics also play an important role (Boushehri et al., 2015; Elstein, 2009; Norman et al., 2007), suggesting that efficiency of knowledge organisation may be independent of clinical exposure. Alternatively, the study period may be insufficient for subjects to fully develop their illness scripts.

In contrast, more experienced doctors performed better at the EMQ, validating the premise that expertise is at least partially linked to experience and acquiring a strong knowledge base (Elstein et al., 1990; Monteiro & Norman, 2013; Neufeld, Norman, Feightner, & Barrows, 1981). Interestingly, only local experience was a significant predictor, but not overall experience. This suggests that overseas experience may not significantly improve clinical reasoning skills in neurological localisation and that the acquisition of such skills is a context-specific process (Durning, Artino, Pangaro, van der Vleuten, & Schuwirth, 2011; Durning et al., 2012; McBee et al., 2015).

Our findings have two potential implications for graduate medical education in Singapore. Firstly, the design of internal medicine residency programmes. To optimise the development of clinical reasoning in neurology, programmes could maximise local experience by assigning residents with less local experience to neurology only in the final year of the three-year residency. However, as local experience may also influence clinical reasoning in other subspecialties, further research is necessary to ascertain the optimal posting configuration that maximises clinical reasoning development across all disciplines.

Secondly, context appears to influence clinical reasoning in neurological localisation. Our results suggest that training location plays a role at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. This might be due to context specificity, which attributes performance variations to situational factors (Durning et al., 2011; Durning et al., 2012; McBee et al., 2015). Since local exposure appears to be beneficial, it implies that overseas graduates and clinicians may require more time to acclimatise or familiarise themselves with the Singapore clinical context.

Our study has several strengths. We used validated, reliable tests to specifically assess clinical reasoning skills for neurological localisation. Homogeneity of the subject cohort, along with the consistent time-frame of test attempts, also allowed us to minimise confounders such as intrinsic motivation (Ferguson et al., 2002; Kusurkar et al., 2010; Vaughan et al., 2015), instructional design (Postma & White, 2015), and duration of neurology exposure.

There were also limitations. This is a single-centre, single subspecialty study with moderate sample size, and our results may not be applicable to other aspects of neurology besides neurological localisation. Further studies are needed to validate whether the results are generalisable beyond the neurology SCT and EMQ, and to other postgraduate populations. The study design was also limited due to the nature of secondary data analysis, thus information on other potentially important variables such as ethnicity (Adams et al., 2008; Guerrasio et al., 2014; Stegers-Jager et al., 2015; Woolf & Cave et al., 2008; Woolf & Haq et al., 2008), age (Woolf et al., 2011) and previous academic performance (Ferguson et al., 2002; Hamdy et al., 2006; Kanna et al., 2009; Stegers-Jager et al., 2015; Woloschuk et al., 2010) could not be fully obtained for evaluation. There is thus a possibility that other confounding variables may influence the findings in this study. Test questions may also intrinsically favour local graduates as they were formulated by local experts, but this is less likely as globally relevant clinical scenarios were tested.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study suggests that local clinical experience and site of undergraduate education predict postgraduate clinical reasoning skill in validated tests of neurological localization. We believe context specificity likely underpins a significant part of clinical reasoning. Our findings have practical implications on residency programme design and highlight the need to provide overseas graduates and clinicians time to adapt to the local clinical context.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Loh Kieng Wee is a Medical Officer under the Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore.

Jerome Ingmar Rotgans is an Assistant Professor at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Dr Kevin Tan is Education Director, Vice-Chair (Education) and a Senior Consultant at the Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore.

Dr Nigel Choon Kiat Tan is Deputy Group Director Education (Undergraduate), Singapore Health Services, and a Senior Consultant at the Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore.

Ethical Approval

Ethical exemption has been granted from the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board A, CIRB Ref: 2020/2228.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance & support provided by the Office of Neurological Education, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore.

Funding

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interest, including financial, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

References

Adams, A., Buckingham, C. D., Lindenmeyer, A., McKinlay, J. B., Link, C., Marceau, L., & Arber, S. (2008). The influence of patient and doctor gender on diagnosing coronary heart disease. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30(1), 1–18.

Amini, M., Moghadami, M., Kojuri, J., Abbasi, H., Abadi, A. A., Molaee, N., & Charlin, B. (2011). An innovative method to assess clinical reasoning skills: Clinical reasoning tests in the second national medical science Olympiad in Iran. BMC Research Notes, 4(1), 418.

Beullens, J., Struyf, E., & Van Damme, B. (2005). Do extended matching multiple-choice questions measure clinical reasoning? Medical Education, 39(4), 410–417.

Boushehri, E., Arabshahi, K. S., & Monajemi, A. (2015). Clinical reasoning assessment through medical expertise theories: Past, present and future directions. Medical Journal of The Islamic Republic of Iran, 29(1), 222.

Case, S. M., & Swanson, D. B. (1993). Extended‐matching items: A practical alternative to free‐response questions. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 5(2), 107–115.

Chan, Y. H. (2004). Biostatistics 201: Linear regression analysis. Singapore Medical Journal, 45(2), 55–61.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Connor, D. M., Durning, S. J., & Rencic, J. J. (2019). Clinical reasoning as a core competency. Academic Medicine. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003027

Durning, S., Artino, A. R., Pangaro, L., van der Vleuten, C. P., & Schuwirth, L. (2011). Context and clinical reasoning: Understanding the perspective of the expert’s voice. Medical Education, 45(9), 927–938.

Durning, S. J., Artino, A. R., Boulet, J. R., Dorrance, K., van der Vleuten, C., & Schuwirth, L. (2012). The impact of selected contextual factors on experts’ clinical reasoning performance (Does context impact clinical reasoning performance in experts?). Advances in Health Sciences Education, 17(1), 65–79.

Durning, S. J., Trowbridge, R. L., & Schuwirth, L. (2019). Clinical reasoning and diagnostic error: A call to merge two worlds to improve patient care. Academic Medicine. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003041

Elstein, A. S. (2009). Thinking about diagnostic thinking: A 30-year perspective. Advances in Health Science Education, 14(sup1), 7–18.

Elstein, A., Shulman, L., & Sprafka, S. (1990). Medical problem solving: A ten-year retrospective. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 13, 5–36.

Eva, K. W. (2005). What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 39(1), 98–106.

Fenderson, B. A., Damjanov, I., Robeson, M. R., Veloski, J. J., & Rubin, E. (1997). The virtues of extended matching and uncued tests as alternatives to multiple choice questions. Human Pathology, 28(5), 526–532.

Ferguson, E., James, D., & Madeley, L. (2002). Factors associated with success in medical school: Systematic review of the literature. British Medical Journal, 324(7343), 952–957.

Fournier, J. P., Demeester, A., & Charlin, B. (2008). Script concordance tests: Guidelines for construction. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 8, 18.

Gelb, D. J., Gunderson, C. H., Henry, K. A., Kirshner, H. S., & Jozefowicz, R. F. (2002). The neurology clerkship core curriculum. Neurology, 58(6), 849–852.

Groen, G. J., & Patel, V. L. (1985). Medical problem solving: some questionable assumptions. Medical Education, 19(2), 95–100.

Groves, M., O’rourke, P., & Alexander, H. (2003). The association between student characteristics and the development of clinical reasoning in a graduate-entry, PBL medical programme. Medical Teacher, 25(6), 626–631.

Guerrasio, J., Garrity, M. J., & Aagaard, E. M. (2014). Learner deficits and academic outcomes of medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians referred to a remediation program, 2006-2012. Academic Medicine, 89(2), 352–358.

Hamdy, H., Prasad, K., Anderson, M. B., Scherpbier, A., Williams, R., Zwierstra, R., & Cuddihy, H. (2006). BEME systematic review: Predictive values of measurements obtained in medical schools and future performance in medical practice. Medical Teacher. 28(2), 103–116.

Huggan, P. J., Samarasekara, D. D., Archuleta, S., Khoo, S. M., Sim, J. H., Sin, C. S., & Ooi, S. B. (2012). The successful, rapid transition to a new model of graduate medical education in Singapore. Academic Medicine, 87(9), 1268–1273.

Kanna, B., Gu, Y., Akhuetie, J., & Dimitrov, V. (2009). Predicting performance using background characteristics of international medical graduates in an inner-city university-affiliated Internal Medicine residency training program. BMC Medical Education, 9, 42.

Kazour, F., Richa, S., Zoghbi, M., El-Hage, W., & Haddad, F. G. (2017). Using the script concordance test to evaluate clinical reasoning skills in psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry, 41(1), 86-90.

Kusurkar, R., Kruitwagen, C., Ten Cate, O., & Croiset, G. (2010). Effects of age, gender and educational background on strength of motivation for medical school. Advances in Health Science Education, 15(3), 303–313.

Lubarsky, S., Chalk, C., Kazitani, D., Gagnon, R., & Charlin, B. (2009). The script concordance test: A new tool assessing clinical judgement in neurology. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 36, 326-331.

Lubarsky, S., Charlin, B., Cook, D. A., Chalk, C., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2011). Script concordance testing: A review of published validity evidence. Medical Education, 45(4), 329–338.

McBee, E., Ratcliffe, T., Picho, K., Artino, A. R., Schuwirth, L., Kelly, W., … Durning, S. J. (2015). Consequences of contextual factors on clinical reasoning in resident physicians. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 20(5), 1225–1236.

Monteiro, S. M., & Norman, G. (2013), Diagnostic reasoning: Where we’ve been, where we’re going. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 25(sup1), S26–S32.

Neufeld, V. R., Norman, G. R., Feightner, J. W., & Barrows, H. S. (1981). Clinical problem-solving by medical students: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Medical Education, 15, 315–322.

Nicholl, D. J., & Appleton, J. P. (2015). Clinical neurology: Why this still matters in the 21st century. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 86(2), 229–233.

Norman, G., Young, M., & Brooks, L. (2007). Non-analytical models of clinical reasoning: The role of experience. Medical Education, 41(12), 1140–1145.

Postma, T. C., & White, J. G. (2015). Socio-demographic and academic correlates of clinical reasoning in a dental school in South Africa. European Journal of Dental Education, 10, 1–8.

Stegers-Jager, K. M., Themmen, A. P. N., Cohen-Schotanus, J., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2015). Predicting performance: Relative importance of students’ background and past performance. Medical Education, 49(9), 933–945.

Tan, K., Chin, H. X., Yau, C. W. L., Lim, E. C. H., Samarasekera, D., Ponnamperuma, G., & Tan, N. C. K. (2017). Evaluating a bedside tool for neuroanatomical localization with extended-matching questions. Anatomical Sciences Education, 11(3), 262-269.

Tan, K., Tan, N. C. K., Kandiah, N., Samarasekera, D., & Ponnamperuma, G. (2014). Validating a script concordance test for assessing neurological localization and emergencies. European Journal of Neurology, 21(11), 1419–1422.

Vaughan, S., Sanders, T., Crossley, N., O’Neill, P., & Wass, V. (2015). Bridging the gap: The roles of social capital and ethnicity in medical student achievement. Medical Education, 49(1), 114–123.

Wan, S. H. (2015). Using the script concordance test to assess clinical reasoning skills in undergraduate and postgraduate medicine. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 21(5), 455–461.

Woloschuk, W., McLaughlin, K., & Wright, B. (2010). Is undergraduate performance predictive of postgraduate performance? Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 22(3), 202–204.

Woloschuk, W., McLaughlin, K., & Wright, B. (2013). Predicting performance on the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Exam Part II. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 25(3), 237–241.

Woolf, K., Cave, J., Greenhalgh, T., & Dacre, J. (2008). Ethnic stereotypes and the underachievement of UK medical students from ethnic minorities: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal [Internet], 377, a1220. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1220

Woolf, K., Haq, I., McManus, I. C., Higham, J., & Dacre, J. (2008). Exploring the underperformance of male and minority ethnic medical students in first year clinical examinations. Advances in Health Science Education, 13(5), 607–616.

Woolf, K., Potts, H. W. W., & McManus, I. C. (2011). Ethnicity and academic performance in UK trained doctors and medical students: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal [Internet], 342, d901. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d901

*Nigel Choon Kiat Tan

Office of Neurological Education,

Department of Neurology,

National Neuroscience Institute

11 Jalan Tan Tock Seng,

Singapore 308433

Email: nigel.tan@alumni.nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 1 July 2019

Accepted: 17 December 2019

Published online: 1 September, TAPS 2020, 5(3), 42-53

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-3/OA2166

Eng Lai Tan1, Sook Yee Gan1, Wei Meng Lim1, Peter C. K. Pook1 & Vishna D. Nadarajah2

1Institute for Research, Development & Innnovation, School of Pharmacy, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2IMU Centre for Education, School of Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

This study measures the impact of the implementation of a dedicated research semester on various perceived competencies related to research. In 2016, surveys were conducted on final undergraduate Pharmacy students in regard to appraisal and critical thinking skills. Students’ perceptions of the impact of research in enhancing their employment potential were investigated. Our evaluation included students’ self-assessment of their writing, presentation, critical thinking and research skills. To assess qualitative parameters, the data obtained were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A total of 113 responses was received. A majority of students indicated that the research semester prepared them in undertaking their research projects. They acknowledged that research helped in building confidence and to acquire the ability to work independently. Most students perceived that the experience gained in research would enhance their employment potential. Overall, students developed critical thinking skills through their respective research project.

Keywords: Undergraduate Research, Pharmacy Programme, Critical Thinking, Research Ethics, Scientific Communication

Practice Highlights

- Competencies from research projects need to be transparent to both students and supervisors.

- Diversity of research projects should reflect the different career pathways of pharmacists.

- Ethical and professional dilemmas from research projects is opportunity for reflective learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Pharmacy profession has undergone tremendous changes over the years, and its scope has expanded. The roles of Pharmacists have extended beyond the traditional boundaries of drug preparation and distribution to ensuring that optimal therapeutic outcomes are achieved through patient-centred cognitive services (Bond, 2006; van Mil & Fernandez-Llimos, 2013). Pharmacists play increasing roles in patient education and counselling, health promotion and disease prevention, disease state management as well as being engaged in inter-professional consultation with other healthcare professionals in specialised patient settings (Holland & Nimmo, 1999; Tsuyuki & Schindel, 2008). The new roles for pharmacists evolve in parallel with evidence-based medicine (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996). Therefore, research skills are essential for both the practice and advancement of the pharmacy profession. In pharmacy, as in all undergraduate science programmes, research is a critical and essential component of the curriculum, although for pharmacy, being a professional degree, competency for practice takes precedence in the priority of the curriculum (Nykamp, Murphy, Marshall, & Bell, 2010). Nevertheless, there is a need to build a strong research program and culture within a pharmacy degree curriculum through sustainable educational initiatives that complement rather than compromise competencies needed for practice. Research being a critical part of scholarship is necessary for inculcating the attributes related to professional competency such as creative and critical thinking as well as problem-solving. Moreover, research also improves student learning skills and encourages the pursuit of research-related careers (Banks, Haynes, & Sprague, 2009; Nykamp et al., 2010).

The implementation of research in pharmacy curricula varies between institutions. Many colleges and universities require students to undertake coursework in research methodology, biostatistics, drug information, and literature evaluation, but only a small fraction of them chose to complete an extensive project with data collection, analysis, and reporting research findings (Murphy, Peralta, & Kirking, 1999). However, increasing emphasis and proportion of time allocated for actual data collection and analyses over the years attest to the recognition of research experience in pharmacy training (Murphy, Slack, Boesen, & Kirking, 2007). Undergraduate or first-degree research training requires a supportive environment and intellectual partnership amongst students and their faculty mentors. Through research, these students are able to apply knowledge gained in the classroom as they define new problems and formulate new research questions (Ash Merkel, 2003). Incorporating research into the curriculum is important as a means of inculcating scholarship in the community of learning, to motivate undergraduates to become independent thinkers and to prepare students for graduate programs (Adamsen, Larsen, Bjerregaard, & Madsen, 2003). A study by Tan revealed that undergraduate students who were guided by suitable research mentors experienced improved thinking, communication, and interpersonal skills. They also manifested heightened levels of self-confidence, resourcefulness, goal-consciousness, creativity and responsibility towards others. These were in contrast to the general feeling of insecurity and uncertainty at the beginning of the research endeavour (Tan, 2007).

Investing in research is often regarded as a costly endeavour which involves dedicated time from faculty members (Nykamp et al., 2010). Furthermore, providing research opportunities for undergraduate students inevitably involves internal funding as well as the involvement of considerable time and proportion of the faculty member. Several major barriers to implementing undergraduate research have been reported. Among these include a lack of faculty members with appropriate expertise and sufficient time for research supervision; other major impediments include the lack of dedicated time for data collection, opportunities, funding, training and support (Nykamp et al., 2010; Paalman, 2002). The logistics of managing research projects for a large number of students have been reported in some studies to be difficult or impossible. Universities have the option of eliminating laboratory experience from their undergraduate research project because of costs associated with maintaining laboratory personnel and the acquisition of expendable laboratory supplies and major equipment (Brandenberger, 1990).

Literature and contextual delivery of pharmacy programs across the world suggest the need to determine the impact of incorporating a research program for an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum (Awaisu & Alsalimy, 2015; Bunnett, 1984; Chopin, 2002; Doerschuk, 2004; Osborn & Karukstis, 2009; Warner, 1998). Will a semester dedicated to entirely research help students achieve the graduate competencies for the pharmacy profession through experiential learning? Hence, this study was conducted to evaluate the impact of a dedicated semester-long research program in an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum.

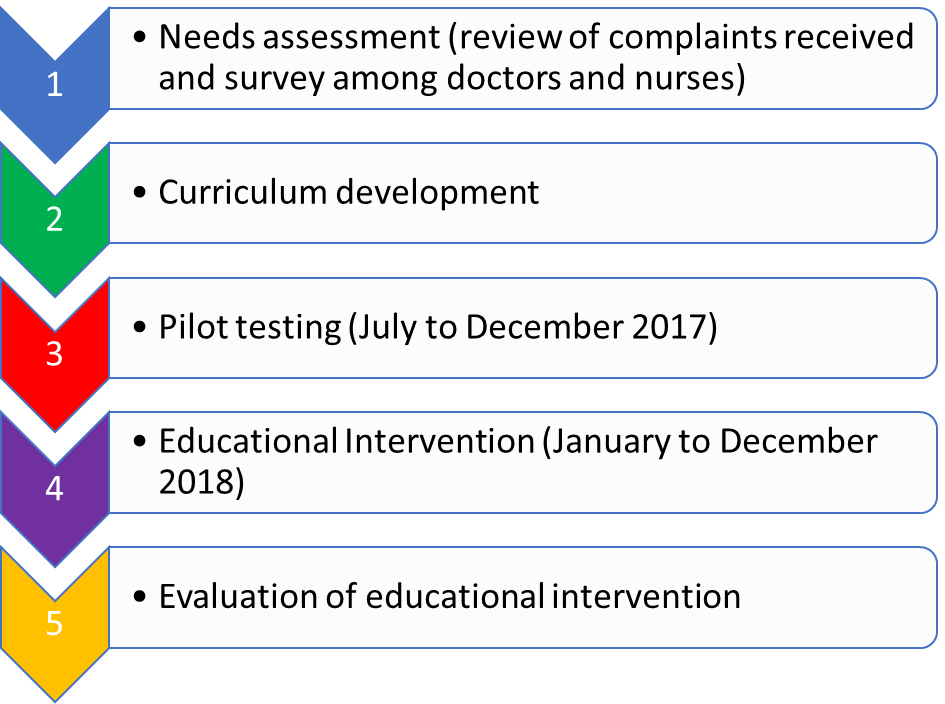

Before the commencement of the research semester, students select their research projects from a range of areas relevant to Pharmacy that include pharmacy practice, pharmaceutical technology, pharmacy chemistry and life sciences. These projects could be further categorised as laboratory-based, community-based or education research. Through the student mobility program and unique research partnership with other local and overseas institutions, students have opportunitiesto conduct their research projects in these external institutions. Students then defend their project proposals in the Research and Ethics Management Committee which ensures the quality, suitability and ethical aspects of a research project. In the Research Methodology module, students are given theoretical instructions in conducting a literature review, scientific writing and research ethics as well as training in statistics. The research semester spans a period of 16 weeks and should, therefore, be designed to provide an immersive experience in the rigours of research. This study measures the impact of the implementation of dedicated research semester on students’ perceived competencies related to research writing, presentation and critical thinking skills, ethical knowledge and preparedness to undertake research.

II. METHODS

This study is part of the regular programme audit conducted by the School of Pharmacy, the findings of which had been reported to the school’s curriculum and examination committee for quality assurance purpose. Student feedback was sought from final year undergraduate pharmacy students at the International Medical University in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in the second half of 2016. Students’ participation was on a voluntary basis after informed consent was obtained and was also a part of the periodic curriculum assessment conducted by the School of Pharmacy. Feedback was obtained from students using an online questionnaire before and after the research project. The questions were developed to measure a student acquiescence of specific perceived competencies relevant to pharmacists as informed by the literature. The face and content validity of the questionnaire were conducted with a small cohort of undergraduate pharmacy students prior to the survey. The pre-research online questionnaire consisted of questions related to the nature, types and placement sites of the projects as well as factors affecting students’ project preference. Ranking questions were also included for students’ self-assessment of their writing, presentation, critical thinking and research skills. In addition, there were also open questions that solicit information pertaining to students’ perceptions about their preparedness to undertake a research project, their knowledge about ethics in research and their anticipated career options. Where Likert-scale was used, the scores from each respondent were added up to achieve the final total. Wilcoxon sign-ranked test was used to compare all ranked data pertaining to students’ perception of their competencies. The post-research survey consisted of similar questions found in the pre-research questionnaire but with an additional section on evaluating the impact of research projects that the students have undertaken. It contained questions to solicit students’ perceptions on the enhancement of their knowledge in specific subject matter, the achievement of research objectives, the challenges they faced during the implementation of research project, skills developed and gained through the research project as well as the aspects of research ethics which are applicable to their future profession as pharmacists and the impact of research experience on their employment potential. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS Statistics and Microsoft Excel.

III. RESULTS

A. Study Population

Out of 180 students, a total of 113 responses was received in surveys conducted prior to and after the commencement of their research projects in the year 2016. These students were supervised by academic staff from all the four departments of the School of Pharmacy, namely life sciences (31%), pharmaceutical chemistry (21%), pharmaceutical technology (10%), pharmacy practice (22%) as well as the School of Dentistry (2%) and the School of Medicine (14%). Eighteen students were involved in community-based or education research while 95 students conducted lab-based research including those who were attached to other local institutions (eight students) or international partner universities (seven students) through collaborative research.

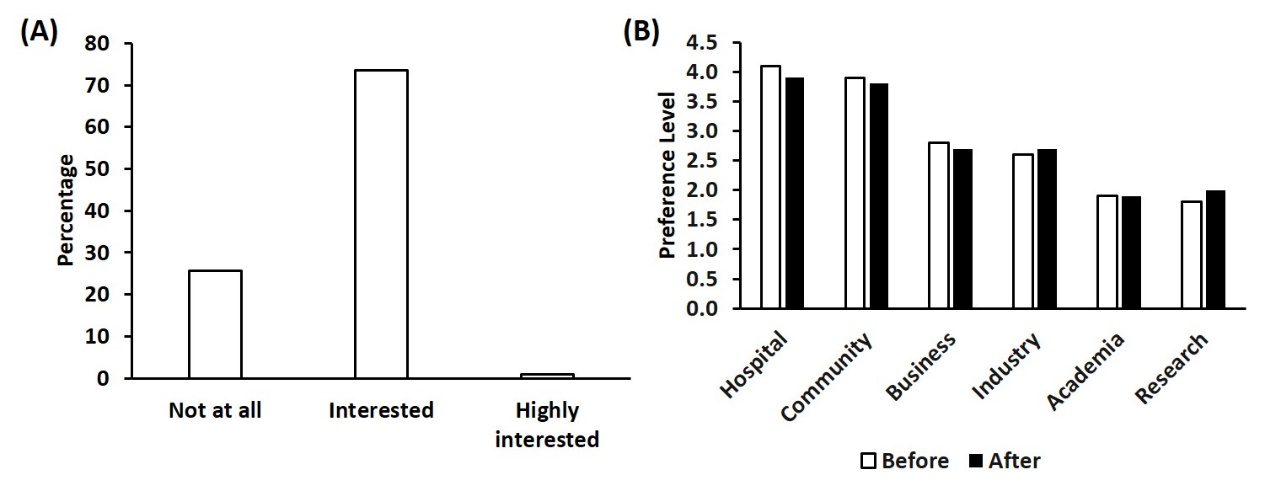

Most students of the cohort were successfully allocated to the project which was their first (61%), second (20%) or third choice (6%) although some (13%) were not allocated to the project of their choice. Interestingly, the main factor affecting the pharmacy students’ preference was research interest (61%). Some students selected the project based on their choice of supervisors (19%), their peer’s choice (10%) while other did not have a specific preference (10%).

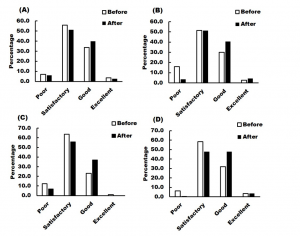

B. Students’ Ratings on Preparedness, Ethics Understanding, Writing and Presentation Skills

In quantitative measures, we evaluate the percentage distribution of student ratings before and after the implementation of research projects pertaining to preparedness to undertake a research project, understanding of research ethics, writing skill and presentation skill. For preparedness to undertake a research project, students are more prepared to undertake a research project in the future, the percentage rating for good had increased from 30.1% to 40.7% (Appendix). However, the frequency distribution of the outcome measures of students’ preparedness after the project implementation was quite similar without any significant difference to before project implementation (p=0.472) (Figure 1A).