Understanding the factors affecting duration in answering MCQ examination: The students’ perspective

Submitted: 6 April 2024

Accepted: 10 December 2025

Published online: 1 April, TAPS 2025, 10(2), 57-64

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-2/OA3332

Chatchai Kreepala1, Srunwas Thongsombat2, Krittanont Wattanavaekin3, Taechasit Danjittrong4, Nattawut Keeratibharat5 & Thitikorn Juntararuangtong1

1School of Internal Medicine, Institute of Medicine, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand; 2Department of Orthopedics, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand; 3Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand; 4Department of Anesthesiology, Chulabhorn Hospital, Thailand; 5School of Surgery, Institute of Medicine, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Abstract

Introduction: Factors affecting decision-making duration in MCQs can enhance assessment effectiveness, ensuring they accurately measure the intended objectives and address issues related to incomplete exams due to time constraints. The authors aimed to explore the aspects of medical student’s perspective regarding the factors influencing their decision making on MCQ assessments.

Methods: A mixed-methods explanatory sequential design was utilised. Initial surveys were conducted using percentages, mean and non-parametric analysis obtained via online questionnaires from the sample group: all 2nd – 5th year medical students from SUT, Thailand. The validity of the questionnaires was verified by three independent reviewers (IOC=0.89). This was followed by semi-structured group interviews to explore student’s perspective on the factors affecting their decision. Qualitative analysis was conducted to explore detailed information until data saturation was achieved.

Results: Data from the quantitative analysis identified four factors that students believe affect the duration of the exam: the total word count of each question, test difficulty, and images in tests. Meanwhile, the qualitative analysis provided additional insights on factors such as the examination atmosphere affecting their decisions.

Conclusion: This report indicated that data acquired from a comprehensive reading question should be distinguished from those requiring decisive reading. Apart from text length, question taxonomy-such as recall or application- and questions with given images and tables should be considered as factors determining time allocation for an MCQ. Future research based on these results should aim to develop a mathematical formula to calculate exam duration, accounting for question difficulty and length.

Keywords: MCQ, Medical Assessment, Medical Education, Testing Time Estimation, Qualitative Research, Students’ Perspective

Practice Highlights

- The multiple-choice question (MCQ) stands as one of the objective assessment methods, widely regarded as the most utilised form of assessment.

- The word-length effect has been proposed to determine the length of each examination.

- Educational theories on decision-making have posited that decision-making is a dynamic process stemming from prior experiences.

- The authors were interested in exploring the aspects of the medical student’s perspective about the factors affecting their decision on MCQs answering.

I. INTRODUCTION

The multiple-choice question (MCQ) stands as one of the available objective assessment methods, widely regarded as the most utilised form of assessment, particularly within the fields of medical sciences and technology. Evidence suggests that the recall of short words often surpasses that of longer words (Tehan & Tolan, 2007). This observation is frequently analysed within the framework of a working memory model and the role of the phonological loop in immediate recall. However, the word-length effect has also been observed in delayed tests and in lists that surpass the memory span, thereby challenging the working memory interpretation of the phenomenon. Three alternative interpretations of the word-length effect have been proposed to explain how an exam length should be determined (Arif & Stuerzlinger, 2009; Kumar et al., 2021).

Educational theories on decision-making have posited that decision-making is a dynamic process stemming from prior experiences (Phillips et al., 2004) and meaningful learning (Foley, 2019). As a result, the ability to comprehend text while reading does not automatically equate to reading for decision-making or answering questions. From the literature, the context of factors influencing medical students’ decisions on MCQs includes 1) Length or number of words: The time students need to read to gather information before making a decision on an answer (Arif & Stuerzlinger, 2009). 2) Difficulty of the questions: analytical thinking, especially calculations are involved, may increase decision-making time. This depends on the students’ prior learning experiences before the exam (González et al., 2008). 3) Language comprehension: since exams in medical schools are often in English, non-native speakers may take longer to read and understand the questions (Schenck, 2020). 4) Visuals and tables: these serve as symbols that help students retrieve information from their prior learning experiences more easily (Ziefle, 1998). It is certain that teachers want academic assessment tests, such as MCQs, to be used to distinguish between high-performing and low-performing students and to assess the knowledge and understanding they have acquired. However, these objectives may be undermined by issues such as students running out of time and resorting to guessing. This inevitably reduces the reliability of the test.

The authors were interested in exploring medical student’s aspect regarding factors affecting their decision on MCQs answering. Previous studies focused on duration required for question comprehension and understanding but not for analysis. These were also mostly done in native Englisher speakers. This study builds upon previous studies but with an emphasis on factors affecting non-native English speakers’ decision making after analysis of the provided questions to answer MCQs in English. This research should be approached from the perspective of the student to obtain appropriate data. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were analysed in conjunction with quantitative data to identify and clarify the reasons and factors that students believe influence their performance on exams.

II. METHODS

A. Study Population

The research participants were second to fifth-year Thai medical students who had taken MCQ tests during their preclinical and clinical years between the academic years 2021-2022. Questionnaires were sent to all students without sampling.

To minimise data artifacts caused by recall bias, the online questionnaires were distributed the first week after each MCQ test before the study to the students who completed the exams. All examinations in this study were computer-based, closed book, single best answer MCQs written in English. The participants were non-native English speakers of Thai nationality (as detailed in Definition of Terms). An online survey or questionnaire-based study was used to collect information from participants in this study. If the data was unsaturated, triangulated data from a group of interviews consisting of students from different rotations was included to receive as much information from students’ perspectives as possible.

B. Study Design and Data Collection

The authors employed a mixed method study comprising a quantitative approach and a sequential, explanatory approach. The literature review unveiled several factors influencing MCQ test duration, including the number of questions, question types (recall or comprehension), subject matter difficulty, calculation items, and picture identification, as outlined in the questionnaire (O’Dwyer, 2012).

An online survey or questionnaire-based study was used to collect information from participants with minimal disruption to their learning activities. The quantitative research section was managed by CK, NK and TJ. Students completed the questionnaire once, based on their experiences in medical school. This, therefore, necessitates the researcher to summarise the responses and, if required, categorise interviews into groups according to their year of study. Open-ended questions were included in the last section of the questionnaire. The open-ended questions about the factors that, in the student’s opinions, were helpful information about the other factors affecting MCQ time (Lertwilaiwittaya et al., 2019). Survey research was employed as a quantitative method, while semi-structured group interviews were utilised in qualitative data collection to gather insights from medical students’ perspectives. The interview questions were designed to investigate whether students possessed any additional insights regarding the factors influencing MCQ test duration (Carnegie Mellon University, 2019; Schenck, 2020; Wang, 2019).

There were three sections in the questionnaire. Part I consisted of the instruction and informed consent. Part II consisted of general information of the participants, including sex, age, and academic year. Part III consisted of the questionnaires covering all four constructive domains previously mentioned (the domains affecting MCQ time from the literature included: 1) the number and total word count, 2) English language questions, 3) calculation questions, 4) the analytical thinking questions and open-ended questions about the factors that, in the students’ opinions, were helpful information about the other factors affecting MCQ time. After the questions in Part One were completed, they would be taken away so that the researchers would not be able to identify whose students have answered Part II and Part III.

To prevent neutral opinions from students, each questionnaire item featured a four-point Likert scale corresponding to levels of agreement: ‘Strongly disagree,’ ‘Disagree,’ ‘Agree,’ and ‘Strongly agree.’ The researcher wanted clear opinion whether the students were trending towards which side, hence the four-point Likert scale to prevent neutral opinion which may complicate statistical analysis. Validity of the questionnaires were verified by three independent reviewers with an Index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) value of 0.89.

Semi-structured group interviews were adopted into this study as insufficient flexibility is provided by a structured interview, whereas unstructured interviews would be too flexible. Semi-structured group interviews were the combination of formal and informal interviews focusing on personal experience; this often leads to unexpected results, enhancing the quality of data collected.

These interviews would take place after class by independent interviewers without any conflict of interest. Two facilitators were present in each session, CK facilitated the conversation and NK contributed ideas. The two facilitators were known by the student participants as faculty members, but they were not actively engaged in their academic learning. Audio and written recording would be coded then decoded by the researchers (SK, KW and TD).

The interview would take around 30-45 minutes per group, with each group consisting of five to eight people. Analysis would be done after the first three groups using relevant domain analysis and further analysis done after new interviews until data saturation was achieved. Coding, theme identification, and triangulation would be undertaken following the analysis and evaluation of the quantitative and qualitative data of which the analysis could be extrapolated to form a conclusion of the study. In this study, the open-end question would be analysed, and the semi-structured interview would be done.

Triangulation helped to provide meaning and helped to gain broader and more precise understanding. It could help increase validity. Triangulation was undertaken following the analysis and evaluation of the quantitative and qualitative data of which the analysis was extrapolated to form a conclusion of the study.

C. Definition of Terms

1) Multiple choice question (MCQ): This paper exclusively focused on the Single Best Answer (SBA) Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs), which were structured as questions followed by 4 or 5 potential answers, with only one correct response per question (Coughlin & Featherstone, 2017).

2) Taxonomy MCQ: MCQs were formulated based on two assumptions: that they could be categorised into higher or lower orders according to Bloom’s taxonomy (Stringer et al., 2021). This study sought to comprehend students’ approaches to questions by examining variances in their perceptions of the Bloom’s level of MCQs regarding their knowledge and confidence. The authors employed Bloom’s taxonomy in this study, classifying questions as “recall,” “comprehension,” and “application” (Stringer et al., 2021).

3) Non-native English speakers: The term non-native English speakers was defined as those students who spoke a language other than English domestically. Non-native English speakers were inclusive of both competent bi-literate and limited English proficiency students. In addition, it is also defined as students who learn the language as older children or adults (Cassels & Johnstone, 1984).

D. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed for quantitative analysis with SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Information in the quantitative section was elaborated and displayed in and counts percentage. The qualitative data was analysed by code grouping of text fragments based on content. Subsequently, the codes were reorganised and grouped, main themes and subthemes were identified, and illustrative quotations were selected. The authors assigned other three medical teachers to undertake independent coding of the transcripts for each interview. The final coding and discussions continued until the frameworks were agreed upon and new themes were derived (CK, SK, KW and TD).

III. RESULTS

A. Demographic Information

The questionnaire was done online by the participants from second to fifth-year medical students in the academic year 2021-2022. There were 93 second-year medical students, 92 third-year medical students, 92 fourth-year medical students, and 93 fifth-year medical students, respectively, with 370 participants in total. It was found that there were 298 respondents (a return rate of 81%). 73 second-year medical students (78% response rate) answered the questions, while 70 third year (76%), 75 fourth year (81%), and 80 fifth year medical students (86%) answered the questions respectively as shown in Table 1.

|

General information |

Category |

n (%) |

|

Gender |

Male |

102(34) |

|

Female |

196(66) |

|

|

Age (year) |

Mean ± SD |

21.3 ± 1.23 |

|

Max, Min |

28, 19 |

|

|

College Year |

Second Year |

73(24) |

|

Third Year |

70(23) |

|

|

Fourth Year |

75(25) |

|

|

Fifth Year |

80(27) |

Table 1. Demographic information of student participants in the survey

Abbreviation: n= number, Max=maximum, Min= minimum

B. Students’ Perspective on Examination Time and Number of MCQs

From the questionnaires, it was found that the medical students thought that the suitable number of questions in the 1-hour examinations that consisted of the intermediate level questions was approximately 41.4±15.62 questions (min-max: 20-120 questions). Moreover, students wanted to gain some more points by guessing rather than leaving the answer blank during the final period of the examination. Regardless of the difficulty of the examinations or the time given, the students would rush to finish the examination in time. Most of the students started to guess the answers at the last 5.4±1.11 minutes (min-max: 2-10 minutes).

C. The Information from the Survey and Semi-Structured Interview

The quantitative data also indicated that various factors influenced the examination duration according to the students’ perspectives. The first three factors were identified through quantitative survey research, encompassing 1) the number of tests and total word count, 2) English language questions, and 3) test difficulty influencing time allocation (including calculation questions and analytical thinking questions) (Table 2). Concurrently, the examination environment also impacted students’ concentration during each test. The latter two pieces of information were corroborated through triangulation from the semi-structured group interviews.

|

Question |

Level of Agreement n (%) (total n =298) |

||||

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Moderate |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

|

1. Number of word count (texts) |

80(27) |

105(35) |

110(37) |

3(1) |

0(0) |

|

2. The English questions |

77(26) |

80(27) |

110(37) |

24(8) |

7(2) |

|

3. The Calculation questions |

131(44) |

60(20) |

92(31) |

11(4) |

4(1) |

|

4 Analytical thinking tests (not a comprehension test) |

105(35) |

105(35) |

77(26) |

11(4) |

0(0) |

Table 2. Evaluating Factors Affecting MCQ Test Time in Student’s Perspectives and the Rating Scores

Abbreviation: n= number

D. The Number Tests and Total Word Count

The exam questions, according to some students, were challenging and time-consuming, and the answer options were likewise lengthy. It was shown that not only the number of tests, but the length of each test item also affected the testing time.

Quote: Student B1F*; “The questions were too long. I can’t complete them in time.”

Quote: Student A2M*; “If there are too many questions in the exam, I wouldn’t be able to finish it”

* student’s code

English Language Questions and Examiners (Native Versus Non-Native English Speakers): The respondents, who were not native English speakers, believed that the English-language test took longer to finish than the Thai-language test. Accordingly, they decided to guess or answer each question slowly since they could not understand the questions. They believed that the English-language tests took longer to finish than the Thai-language tests. Accordingly, they decided to guess or answer each question slowly since they could not fully understand the English questions.

Quote: Student D1F*; “I’m not good at reading English. Sometimes I just have to guess on the exam.”

Quote: Student C1M*; “The language in the test is too hard to understand.”

* student’s code

E. Test Difficulty Determining Time Allocation

For the analysis of coding, grouping, and generating themes, the author found that the medical students paid attention to the difficulty level of the questions which affected the decision to answer the questions.

1) The Calculation and Analytical Thinking: The calculation and analytical thinking tests took students longer to read. Additionally, students believed that examinations they had never taken before or exams that required knowledge application took longer to complete, such as exams that included questions requiring the students to diagnose patients by themselves which occasionally left them unsure of how to respond.

Quote: Student C2M*; “Calculation tests take a long time to get the answers.”

* student’s code

2) Recall Question Leads to Quick Answers: Students commented that recall-type questions, including tests from previous academic years, contained duplicated sentences, pictures, or messages from textbooks that students remembered. This led to students being able to complete the test in a short thinking time.

Quote: Student K1M*; “If the teacher copied the exact words from the course sheet, I would remember and answer questions quickly.”

Quote: Student L1M*; “If the questions are the same as in the sheet provided, I can answer them.”

*student’ code

This information indicated that the taxonomy of the test (recall -compression-application) had a large effect on decision time. Applied questions, not direct or calculated questions, required more attention and time for decision-making when compared to comprehensive questions (questions about knowledge understanding). In contrast, recall questions required the least decision-making time.

F. The Visual Image and Atmosphere of the Examination: the New Derived Domains Recognised by Qualitative Analysis

1) Questions with images, graphs, or tables serve as key guides for decision-making: The students thought that the exams that consisted of graphs and tables helped them understand the questions and were better than the questions that only had descriptions. That would lead to less time consumed.

Quote: Student L2M*; “If the test got the exact same summary table from the book, I could remember and get the answers right away.”

* student’s code

2) The Atmosphere of the Examination: The environment and atmosphere of the exam were also mentioned. The student’s response time was slowed down by the distractions during the exam. The environment such as brightness, temperature, and examination devices affected the concentration of the students.

Quote: Student H1F*; “The atmosphere in the exam venue, noise, and the air quality in the room affect the exam results.”

*student’s code

IV. DISCUSSION

The results revealed that students perceived lengthy exam content or a large number of questions as time-consuming, particularly when exams were conducted in English. Studies indicated that English speakers could read up to 150 words per minute (Trauzettel-Klosinski et al., 2012). However, for non-native English speakers, the expected reading time for exams was longer. Hence, using the English reading rate as a basis for determining exam duration was deemed unsuitable for Thai students, given that English was not their primary language of communication. When compared with a previous study (Trauzettel-Klosinski et al., 2012), the increased duration may result from decision making, thus this implicates reading for decision making requires more time than reading for the context which is cumulatively longer for non-English native speakers.

Qualitative findings indicated that irrespective of the exam duration set by the administering professor, students generally completed exams within the allotted time frame. This often entailed guessing answers towards the end of the exam period, as students might not have adequate time to complete the exam thoroughly. It was observed that students tended to resort to guessing exam questions approximately five minutes before the exam conclusion, thereby minimising threats to validity posed by guessing due to time constraints during exam (Foley, 2019).

There may be limitations if the exam questions contain lengthy content that cannot be comprehended and decided upon within one minute. Furthermore, the difficulty level of the exam questions is often established as a passing criterion, prioritising validity considerations in terms of content format and achieving the intended objectives. Moreover, students naturally desire to obtain the highest possible score on the exam, regardless of the level of difficulty or length of the exam. Therefore, it is important for students to manage their time effectively to ensure they can complete all the exam questions within the given timeframe.

The qualitative results indicated that regardless of the exam duration set by the administering professor, students ultimately would complete the exam within the allotted time frame. Additionally, students agreed that application and calculation questions on the exam require more time to read and decide upon, as opposed to questions with figures and tables that aided in faster decision making. Based on these findings, it could be concluded that comprehensive reading rates may not be a reliable indicator of decision-making reading rates, particularly in the context of medical school exams. Therefore, studying decision-making reading rates within the context of medical school exams was crucial.

The researcher, therefore, examined the domain and specific factors on the characteristics of the MCQ test. Additionally, the study scope was limited to English tests administered to non-native English speakers and onsite computer-based tests, thereby eliminating unrelated factors that could impact exam duration. The analysis yielded the following results: Firstly, factors positively correlated with exam duration (negatively correlated with decision-making) included the number of questions, total word count, calculation questions, and analytical thinking questions. Secondly, factors negatively correlated with exam duration (positively correlated with decision-making) were recall questions, questions with provided images, and tables.

A factor contributing to longer reading times for decision-making purposes was when the exam contained a higher proportion of application or calculation questions, comprising over 33% of the exam questions, as evidenced by qualitative data from students. Therefore, analysing exam completion time based on reading comprehension data for decision-making purposes is not recommended. Moreover, it should be noted that these factors present internal threats to validity, but they can be managed to ensure that examination tools are effectively used and aligned with intended objectives. Incorporating data from research can lead to the identification of new themes related to factors influencing examination time.

Five constructive domains were identified: 1) the number and total word count, 2) positive difficulty factors (application/calculation questions), 3) negative difficulty factors (recall questions), 4) examiners (non-native English speakers or not), and 5) pictures/symbols in tests.

A distinctive aspect of this study was its targeted focus on Thai medical students who were non–native English speakers. While many studies have examined MCQ performance across broad and diverse populations, this research concentrated on a specific demographic, enabling a more in-depth exploration of how cultural and linguistic factors influence test-taking behaviour. The study uniquely combined quantitative survey data with qualitative insights from semi-structured group interviews. While some research utilised either quantitative or qualitative methods, this study’s integration of both provided a more holistic understanding of student perspectives and experiences (Lertwilaiwittaya et al., 2019). This methodological triangulation strengthened the validity of the findings by cross-verifying quantitative data with qualitative insights. In contrast to many existing studies that focused predominantly on performance metrics (such as scores or pass rates), this research examined the cognitive processes and decision-making strategies students employed while answering MCQs. It investigated how elements like question difficulty, language comprehension, and prior experiences shaped students’ approaches to test questions—a dimension less frequently explored in previous literature.

In conjunction with examination-related factors, students also recognised the importance of considering the test environment within the examination room which was a new finding found using qualitative analysis from this research. This was crucial for promoting student concentration and facilitating accurate response selection in line with assessment tool objectives. It aligned with existing literature, which suggested that the test environment poses a construct irrelevant threat to the validity of educational measurement. The findings from this study may have led to future research on developing a mathematical formula to tailor the exam duration for different sets of questions. This would have involved analysing factors such as the number of words, length, difficulty, and the presence of images and tables in the exam. Additionally, the impact of language proficiency on reading and decision-making time should have been considered, as there may have been differences between native and non-native speakers. The study suggested that the future research direction should include diverse populations of non-native English speakers from different countries and educational contexts. This could help identify whether the findings are consistent across various cultural backgrounds and educational systems. Moreover, conducted longitudinal studies should be used to track students’ performance and decision-making processes over time. This approach could provide insights into how experiences and familiarity with MCQs influence their strategies and confidence levels throughout their medical education.

A major limitation of this research was the variation in learning experiences, exam-taking skills, and analytical thinking among medical students at different year levels, which might lead to differing opinions. Therefore, the researcher needed to conduct qualitative analysis to examine the reasons behind these differences. However, the diversity of experiences might also introduce bias due to varying familiarity with different types of exams. The online format restricted the depth of responses, as students often did not fully articulate their thoughts without immediate follow-up questions, which limited the richness of the qualitative data. Additionally, the focus on Thai medical students constrained the applicability of the findings to other populations or contexts, thereby limiting broader conclusions about non-native English speakers in different educational settings.

V. CONCLUSION

Based on the student’s perspective, data showed questions with lengthy content required more time whilst those with tables or diagrams required less time. This report indicated that the data acquired from a comprehensive reading examination should be distinguished from a decisive reading examination.

In addition to the number of questions and the length of text, factors that should be positively correlated with the duration of the exam include the number of questions, word count, calculation-based questions, and analytical thinking questions. These factors should be considered for additional time allocation beyond the regular exam duration, particularly when the proportion of analytical thinking questions exceeds one-third of the total question set. On the other hand, recall questions, as well as questions accompanied by images and tables, should be taken into account to ensure a balanced distribution of exam time, as they can be answered more easily and quickly in terms of decision-making compared to general questions.

Notes on Contributors

CK conceived of the presented idea, developed the theory, and performed the computations and discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. ST, KW, and TD. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript with support from CK, NK, and TJ, designed the model and the computational framework and analysed the data.

Ethical Approval

All participants voluntarily signed a consent form prior to participating in the study. The participation protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Suranaree University of Technology (Issue # EC-64-102).

Data Availability

Institutional ethical clearance was given to maintain the data in the secure storage of the principal investigator of the study. The data to this study may be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. A preprint of our manuscript, which is not peer-reviewed, is available at https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3019852/v1

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study, the medical students in the Institute of Medicine, Suranaree University of Technology. Without their passionate participation and input, the validation survey could not have been successfully conducted.

Funding

This work was supported by the Grant of Suranaree University of Technology (contract number SUT-602-64-12-08(NEW)).

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Arif, A. S., & Stuerzlinger, W. (2009). Analysis of text entry performance metrics [Conference presentation]. 2009 IEEE Toronto International Conference Science and Technology for Humanity (TIC-STH), Canada. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIC-STH.2009.5444533

Cassels, J., & Johnstone, A. (1984). The effect of language on student performance on multiple choice tests in chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 61(7), 613. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed061p613

Coughlin, P., & Featherstone, C. (2017). How to write a high-quality multiple-choice question (MCQ): A guide for clinicians. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 54(5), 654-658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.07.012

Carnegie Mellon University. (2019). Creating exams Eberly Center. https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/assesslearning/creatingexams.html

Foley, B. P. (2019). Getting lucky: How guessing threatens the validity of performance classifications. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 21(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.7275/1g6p-4y79

González, H. L., Palencia, A. P., Umaña, L. A., Galindo, L., & Villafrade M, L. A. (2008). Mediated learning experience and concept maps: A pedagogical tool for achieving meaningful learning in medical physiology students. Advances in Physiology Education, 32(4), 312-316. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00021.2007

Kumar, D., Jaipurkar, R., Shekhar, A., Sikri, G., & Srinivas, V. (2021). Item analysis of multiple choice questions: A quality assurance test for an assessment tool. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 77, S85-S89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.11.007

Lertwilaiwittaya, P., Sitticharoon, C., Maikaew, P., & Keadkraichaiwat, I. (2019). Factors influencing the National License Examination step 1 score in preclinical medical students. Advances in Physiology Education, 43(3), 306-316. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00197.2018

O’Dwyer, A. (2012). A teaching practice review of the use of multiple-choice questions for formative and summative assessment of student work on advanced undergraduate and postgraduate modules in engineering. All-Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.21427/D7C03R

Phillips, J. K., Klein, G., & Sieck, W. R. (2004). Expertise in judgment and decision making: A case for training intuitive decision skills. Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, 297, 315. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470752937.ch15

Schenck, A. (2020). Examining the influence of native and non-native English-speaking teachers on Korean EFL writing. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-020-00081-3

Stringer, J., Santen, S. A., Lee, E., Rawls, M., Bailey, J., Richards, A., . . . Biskobing, D. (2021). Examining Bloom’s taxonomy in multiple choice questions: Students’ approach to questions. Medical Science Educator, 31(4), 1311-1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01305-y

Tehan, G., & Tolan, G. A. (2007). Word length effects in long-term memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 56(1), 35-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2006.08.015

Trauzettel-Klosinski, S., Dietz, K., & Group, I. S. (2012). Standardized assessment of reading performance: The new international reading speed texts IReST. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 53(9), 5452-5461. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8284

Wang, A. (2019, July 15). How to determine the best length for your assessment. Pear Deck Learning. https://www.peardeck.com/blog/how-to-determine-the-best-length-for-your-assessment

Ziefle, M. (1998). Effects of display resolution on visual performance. Human Factors, 40(4), 554-568. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872098779649355

*Assoc. Prof. Chatchai Kreepala, M.D.

Institute of Medicine

Suranaree University of Technology

Thailand

+66(93)3874665

Email: chatchaikree@gmail.com

Submitted: 17 April 2024

Accepted: 18 December 2025

Published online: 1 April, TAPS 2025, 10(2), 65-70

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-2/OA3336

Rachael Tufui Masilomani1, Sophaganie Jepsen1, Maria Lourdes Villaruel1, Aying Wang1, Alena Kotoiwasawasa1, Lusiana Naikawakawavesi1, Norman Bartolome1, Claudia Paterson2, Andrew Hill2 & Maria Concepcion Bartolome1

1Basic Clinical Medicine, Fiji National University, Fiji; 2Department of Surgery, Middlemore Hospital, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Introduction: The MBBS programme at Fiji National University reduced its teaching weeks from 18 to 14 weeks in 2018. The purpose of this study was to assess student perceptions of learning and teachers following the reduction in the number of teaching weeks from 18 to 14 weeks.

Methods: A questionnaire was created using a modified Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (mDREEM) tool (23 items). This was comprised of two subscales; Students Perception of Learning (SPL – 12 items) and Students Perception of Teachers (SPT – 11 items). This was circulated to Year 5 MBBS students through an online survey in 2020.

Results: The response rate was 96%. The students regarded their educational environment as positive in both length of teaching weeks, with an overall mDREEM mean score of 63.29 in 18 weeks and 62.03 in 14 weeks. No statistically significant differences were found between 18 week and 14 week scores across mDREEM scores, SPL scores or SPT scores. The highest scoring item over both was ‘teachers are knowledgeable’.

Conclusion: A positive perception was noted for both lengths of teaching weeks. Reducing the teaching weeks from 18 to 14 did not statistically significantly reduce students’ perception of their educational environment. Items identified with low scores will give a window of opportunity for lecturers and to improve these areas. Future studies may explore the use of the five subscales of the DREEM tool and this study can be integrated into further evaluations of educational environment at Fiji National University.

Keywords: Medical Students, Educational Learning Environment, DREEM Tool, Fiji National University, Teaching, Medical Education

Practice Highlights

- mDREEM scores did not significantly differ between 18 weeks and 14 weeks of teaching.

- The highest scoring item over both weeks was ‘teachers are knowledgeable’.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Fiji National University (FNU) was founded in 2010 by the merging of six academic institutions in the Fiji Islands, including the Fiji School of Medicine (FSM). FNU has continued the FSM’s tradition of educating and training a diverse population of students from Fiji and neighbouring Pacific Island nations. The Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) programme is a six-year course at FNU. As part of the academic year, each pre-clinical year group have a teaching week block course. During this time, students receive 2-4 hours of scheduled lectures, 2-hour tutorials twice weekly, as well as 2 hours of clinical skills and 2 hours of anatomy, 2 hours of laboratory sessions and a health centre attachment 4 hours a week.

In 2018, FNU reduced the teaching week block course in the MBBS programme from 18 weeks to 14 weeks. The teaching weeks were shortened due to the decision to move specialty courses such as Psychiatry and Public Health to their respective clinical blocks from Years 4 to 6. This adaptation was challenging for the lecturers, who had to reformat their teaching sessions, in addition to providing resources onto an online Moodle platform. It is well established that the educational environment plays an important role in determining the academic success of medical students (Prosser et al., 1999; Ramsden 2003). Therefore, it is important to evaluate the impact of any major changes to the educational environment, such as a reduction in teaching weeks from 18 weeks to 14 weeks.

Previous research has demonstrated that the duration of clinical rotations has been able to be decreased without adversely affecting the academic success of medical students. For example, one group demonstrated that a shortened four-week clinical rotation in Obstetrics and Gynaecology provided enough opportunity for final year medical students to undertake a quality improvement project in the curriculum (Kool et al., 2017).

The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) is a quantitative tool used to evaluate students’ perceptions of the educational environment in medical schools. The DREEM tool consists of 50 items, each rated on a scale from 0 to 4. It has five domains, allowing for a maximum score of 200. Higher scores indicate a positive perception of the learning environment (Roff et al., 1997).

A systematic review published in 2012 analysed 40 studies reporting DREEM scores from 20 countries. This review demonstrated that DREEM had been used internationally for various purposes, including diagnostic assessments and comparative studies across different groups (Miles et al., 2012). Five studies focused on investigating the impact of a changed curriculum, which was our area of interest (Demirören et al., 2008, Edgren et al., 2010, O’Brien et al., 2008, Riquelme et al., 2009, Till et al., 2004). We identified three key themes: 1) the DREEM tool was able to highlight areas of concern and/or remediation among students (Riquelme et al., 2009 Till et al., 2004), 2) DREEM scores were different in different phases of medical education, with year 3 students having the highest scores, and year 5 students having the lowest scores (Demirören et al., 2008, Riquelme et al., 2009), and 3) the DREEM tool identified clusters of students based on how positively they perceived the curriculum (O’Brien et al., 2008).

The aim of this research was to compare students’ perception of learning and teachers between 18 weeks and 14 weeks, using a modified DREEM (mDREEM) tool which utilises two of the five domains from the original DREEM tool. The authors’ hypothesis was that students’ perception of learning and teaching would be reduced in with a decrease in teaching weeks to 14 weeks compared to 18 weeks.

II. METHODS

A. Participants

An online survey was developed by the authors. This was distributed via email to eligible participants using Google Forms from 12th December to 17th December 2020. Eligible participants included the Year 5 MBBS cohort of 2021, as this cohort was exposed to both 18 week and 14 week teaching programmes. Participation in the survey was optional and results were anonymous. Submission of a completed survey was taken as providing informed consent to participate in this research. Full ethics approval was provided through FNU’s College Human Health Ethics Committee (ID: 292.20). Facility approval was granted to conduct the research.

B. mDREEM Tool

The authors selected two of the five domains of the DREEM tool to be included in the survey. The selected two domains included students’ perceptions of learning (SPL) and students’ perceptions of teachers (SPT). The rationale for using only these two domains was that they were the two domains of interest for the teachers, and it was thought that a survey with less questions would be more likely to be filled to completion by more of the students. Using a Likert scale, each item was scored from 0 to 4, with 4 = strongly agree, 3 = agree, 2 = not sure, 1 = disagree and 0 = strongly disagree. Six of the 23 statements in the mDREEM tool were negative statements: 1) the teaching over-emphasised factual learning; 2) the teaching is too teacher-centred; 3) teachers ridicule the students; 4) the teachers are authoritarian; 5) teachers get angry in class and 6) the students irritate the teachers. These were scored in a reverse manner.

The mDREEM tool had a maximum score of 92. The SPL domain included 12 items, with a maximum score of 48. The SPT domain included 11 items, with a maximum score of 44. This research used the following guide to interpret the overall scores:

- 0–23 = Very poor environment

- 24 – 46 = A large number of problems in the environment

- 47–69 = More positive than negative environment

- 70–92 = Excellent

C. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the collected data was by using R version 4.3.1. Mean scores were reported with standard deviations. Paired t-tests were performed to compare aspects of the mDREEM scores over 18 weeks and 14 weeks, with a statistical significance threshold of p<0.05. Reliability analysis of the mDREEM tool was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha test, where >0.7 was deemed acceptable internal consistency.

III. RESULTS

Seventy-eight out of eighty-one (96%) MBSS Year 5 students participated in the online survey. Fifty-one (65%) were females and 51% of participants were aged between 23 and 25 years old. Fijian of Indian descent students made up the majority of the responders (67%) followed by other ethnicities (18%) and i-Taueki students (15%). The majority of students resided at the FNU Hostel (69%) while 28% lived within Suva and only 3% lived outside Suva.

Table 1 illustrates the 23 individual mDREEM items with mean scores across 18 weeks and 14 weeks. The item ‘the teaching overemphasised factual learning’ scored the lowest for both 18 and 14 weeks. The item ‘teachers are knowledgeable’ scored the highest for both 18 and 14 weeks.

|

Items |

mDREEM item |

Code |

18 weeks |

14 weeks |

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

1 |

I am encouraged to participate in class |

SPL |

3.13 |

0.91 |

2.78 |

1.03 |

|

2 |

The teaching is often stimulating |

SPL |

2.79 |

1.02 |

2.65 |

0.94 |

|

3 |

The teaching is student-centred |

SPL |

2.97 |

0.95 |

2.79 |

0.92 |

|

4 |

The teaching helps to develop my competence |

SPL |

3.06 |

0.82 |

2.63 |

0.92 |

|

5 |

The teaching is well focused |

SPL |

2.67 |

1.00 |

2.55 |

1.03 |

|

6 |

The teaching helps to develop my confidence |

SPL |

2.88 |

1.01 |

2.79 |

0.94 |

|

7 |

The teaching time is put to good use |

SPL |

2.81 |

1.12 |

2.60 |

1.00 |

|

8 |

The teaching over-emphasised factual learning |

SPL |

1.85 |

0.92 |

1.91 |

0.79 |

|

9 |

I am clear about the learning objectives of the course |

SPL |

2.77 |

1.02 |

2.78 |

0.98 |

|

10 |

The teaching encourages me to be an active learner |

SPL |

2.86 |

1.16 |

2.97 |

0.88 |

|

11 |

Long term learning is emphasised over short term learning |

SPL |

2.59 |

1.13 |

2.56 |

0.98 |

|

12 |

The teaching is too teacher-centred |

SPL |

2.85 |

0.80 |

2.74 |

0.78 |

|

13 |

The teachers are knowledgeable |

SPT |

3.18 |

0.83 |

3.13 |

0.80 |

|

14 |

The teachers are patient |

SPT |

3.01 |

0.73 |

2.74 |

0.89 |

|

15 |

The teachers ridicule the students |

SPT |

2.49 |

0.97 |

2.56 |

0.97 |

|

16 |

The teachers are authoritarian |

SPT |

2.49 |

0.96 |

2.58 |

0.91 |

|

17 |

The teachers have good communication skills |

SPT |

3.04 |

0.90 |

2.99 |

0.71 |

|

18 |

The teachers are good at providing feedback to students |

SPT |

2.54 |

1.15 |

2.86 |

0.96 |

|

19 |

The teachers provide constructive criticisms |

SPT |

2.85 |

0.90 |

2.92 |

0.84 |

|

20 |

The teachers give clear examples during class |

SPT |

2.78 |

0.91 |

2.79 |

0.84 |

|

21 |

The teachers get angry in class |

SPT |

2.63 |

1.01 |

2.63 |

0.85 |

|

22 |

The teachers are well prepared for their classes |

SPT |

2.87 |

0.90 |

2.92 |

0.81 |

|

23 |

The students irritate the teachers |

SPT |

2.23 |

0.95 |

2.23 |

0.83 |

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of individual item DREEM scores for 18 and 14 teaching weeks

The mean SPL scores over 18 weeks and 14 weeks were 33.23 (SD 7.38) and 31.74 (SD 7.52), respectively, out of a maximum of 48 (SPL 18 weeks: 69.33%; SPL 14 weeks: 66.13%). The mean SPT scores over 18 weeks and 14 weeks were 30.06 (SD 6.34) and 30.28 (SD 5.74), respectively, out of a maximum of 44 (SPT 18 weeks: 68.32%; SPT 14 weeks: 68.82%). The mean mDREEM scores over 18 weeks and 14 weeks were 63.29 (SD 12.58) and 62.03 (SD 12.01), respectively, out of a maximum of 92 (mDREEM 18 weeks: 68.80%; mDREEM 14 weeks: 67.42%). These results are presented in Table 2.

|

|

SPL 18 |

SPL 14 |

SPT 18 |

SPT 14 |

mDREEM 18 |

mDREEM 14 |

|

Mean |

33.23 |

31.74 |

30.06 |

30.28 |

63.29 |

62.03 |

|

SD |

7.38 |

7.52 |

6.34 |

5.74 |

12.58 |

12.01 |

Table 2. Descriptive summary statistics for 18 and 14 teaching weeks

The mean difference in SPL scores between 18 weeks and 14 weeks was 1.48. This difference was not statistically significant (t (77) = 1.61, p = 0.11). The mean difference in SPT scores between 18 weeks and 14 weeks was -0.22, and this was also not statistically significant (t (77) = -0.43, p = 0.67). The mean difference in overall mDREEM scores between 18 weeks and 14 weeks was 1.27, which was also not statistically significant (t (77) = 1.04, p = 0.30).

The reliability analysis for both 18 and 14 teaching weeks found a Cronbach’s Alpha Test of 0.58 for SPL, which was less than the threshold of 0.7 and 0.84 for SPT, which was greater than the threshold of 0.7. For mDREEM, the Cronbach’s Alpha Test was 0.77, which was greater than the threshold of 0.7 and confirmed acceptable internal consistency for the mDREEM tool.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that a reduction in teaching from 18 to 14 weeks did not result in a significant decrease in mDREEM, SPL or SPT scores among Year 5 MBBS students at FNU in 2020. This finding refuted the authors’ hypothesis of a reduction in teaching weeks leading to student dissatisfaction of the educational environment.

Both 18 weeks and 14 weeks scored within the range of 47 to 69 out of 92, indicating a ‘more positive than negative environment’ based on predefined thresholds outlined in the methods section. The ‘excellent’ threshold of 70+ out of 92 was not obtained, indicating room for improvement. In particular, the item ‘teachers are knowledgeable’ scored the highest for both 18 and 14 weeks indicating that students perceived their teachers to have high levels of knowledge despite the reduction in teaching weeks. In contrast, ‘the teaching overemphasised factual learning’ was identified as the most significant negative statement and provides an area of focus for the lecturers.

One group used the DREEM tool to assess curriculum changes in an Irish medical school and that found that the new curriculum was associated with students reporting higher mean DREEM scores (Finn et al., 2014). While FNU’s curriculum change did not result in higher mDREEM scores, the maintenance of mDREEM scores is encouraging and provides a framework for ongoing work towards improving students’ perception of their educational environment.

This finding was similar to a previous study reviewing shortened medical education rotations previously discussed in the introduction section of this paper (Kool et al., 2017). Given the concordance with other similar research findings, the authors are of the belief that the results from this study are largely generalisable to MBBS students and lecturers worldwide, despite only being a single-centre study.

A major strength of this study was the high response rate of 96%. This ensures that data collected as part of this research is representative of the population of interest as compared to several studies with lower response rates (Al-Ansari et al., 2015; Ali et al., 2012; Hyde et al., 2018). Moreover, the results are comparable to the high response rates of other DREEM studies conducted internationally (Alraawi et al., 2020; Stormon et al., 2019; Till et al., 2004).

One limitation of this study was using only two domains of the DREEM tool, neglecting the three domains of Students’ Academic Self-Perception (SAP), Students’ Perception of Atmosphere (SPA) and Students’ Social Self-Perception (SSP). The authors selected SPT and SPL as the two key domains for this research, and thought that by selecting the two most relevant domains, that this would shorten the questionnaire and improve completion of the questionnaire amongst participants. Future research at FNU should trial the use of all five domains of the DREEM tool to assess whether this provides further insights into how teaching weeks can be improved for MBBS students. It will be of interest to see whether response rates are reduced with the use of the full DREEM tool in a questionnaire. Furthermore, future surveys should investigate perspectives of MBBS students over a range of year groups, given previous research suggesting that Year 3 MBBS students have higher DREEM scores than Year 5 MBBS students. A second limitation of this study was that the alpha value for SPL failed to achieve the threshold of >0.7, making it concerning that this domain was unable to achieve acceptable internal consistency. However, the authors note that SPT and mDREEM both achieved acceptable internal consistency. A final limitation of this study was the fully quantitative nature of the survey – the authors did not provide an option for students to add comments to this survey. Future surveys should provide an option for students to add comments, in order to provide more insights into the perspectives of MBBS students.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the students rated FNU’s MBBS programme educational environment positively. A reduction in teaching weeks from 18 to 14 did not result in a statistically significant decrease in SPL, SPT or mDREEM scores. This study identified valuable information for the authors regarding the improvement of educational environment for medical students. Utilisation of these results to guide educational development in these areas needing improvement will be of help in shaping the delivery of quality education to medical students. In addition, this research may open a door for further studies to investigate challenges faced by tutors and link it to the perceptions of medical students in their educational environment. Likewise, this study is important for future studies in evaluating the educational climate for FNU and other local and international universities.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Maria Bartolome is the corresponding author for this research. She is a PBL (problem based learning) lecturer at the School of Medicine, Fiji National University. She was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing the original draft.

Dr Norman Bartolome is a PBL lecturer at the School of Medicine, Fiji National University. He was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, and writing the original draft.

Dr Alena Kotoiwasawa is a PBL lecturer at the School of Medicine, Fiji National University, and was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, and investigation.

Dr Rachael Masilomani is a former PBL lecturer at the School of Medicine, Fiji National University. She was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, and formal analysis.

Dr Lusiana Naikawakawavesi is a PBL lecturer at the School of Medicine, Fiji National University, and was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, and investigation.

Dr Maria Villareul is a PBL lecturer at the School of Medicine, Fiji National University. She was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, and investigation.

Dr Sophaganie Jepson is a PBL lecturer at Fiji National University. She was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, investigation.

Dr Aying Wang is a former PBL Lecturer at Fiji National University. He was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, investigation.

Dr Claudia Paterson is a research fellow at The University of Auckland, New Zealand. She was involved in formal analysis, reviewing and editing.

Professor Andrew Hill is a colorectal surgeon and Professor of Surgery at Middlemore Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand. He was involved in supervision, reviewing and editing.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was provided through FNU’s College Human Health Ethics Committee (CHHREC) – reference ID: 292.20.

Data Availability

The corresponding author is able to provide researchers access to our anonymised dataset, on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the efforts of the students in participating in this study.

Funding

No funding was used for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Al-Ansari, A. A., & El Tantawi, M. M. A. (2015). Predicting academic performance of dental students using perception of educational environment. Journal of Dental Education, 79(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.00220337.2015.79.3.tb05889.x

Ali, K., Raja, M., Watson, G., Coombes, L., & Heffernan, E. (2012). The dental school learning milieu: Students’ perceptions at five academic dental institutions in Pakistan. Journal of Dental Education, 76(4), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2012.76.4.tb05281.x

Alraawi, M. O., Baris, S. A., Ahmari, N. A., Alshadidi, A. B., Abidi, N. A., & Al Moaleem, M. (2020). Analyzing students’ perceptions of educational environment in new dental colleges, Turkey using DREEM Inventory. Bioscience Biotechnology Research Communications, 13(2), 556–564. http://dx.doi.org/10.21786/bbrc/13.2/29

Demirören, M., Palaoğlu, Ö., Kemahlı, S., Özyurda, F., & Ayhan, İ. H. (2008). Perceptions of students in different phases of medical education of educational environment: Ankara University Faculty of Medicine. Medical Education Online, 13, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3885/meo.2008.Res00267

Edgren, G., Haffling, A. C., Jakobsson, U., McAleer, S., & Danielsen, N. (2010). Comparing the educational environment (as measured by DREEM) at two different stages of curriculum reform. Medical Teacher, 32(6), e233–e238. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421591003706282

Finn, Y., Avalos, G., & Dunne, F. (2014). Positive changes in the medical educational environment following introduction of a new systems-based curriculum: DREEM or reality? Irish Journal of Medical Science, 183(2), 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-013-1000-4

Hyde, S., Hannigan, A., Dornan, T., & McGrath, D. (2018). Medical school clinical placements – The optimal method for assessing the clinical educational environment from a graduate entry perspective. BMC Medical Education, 18, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1113-y

Kool, B., Wise, M. R., Peiris-John, R., Sadler, L., Mahony, F., & Wells, S. (2017). Is the delivery of a quality improvement education programme in obstetrics and gynaecology for final year medical students feasible and still effective in a shortened time frame? BMC Medical Education, 17, Article 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0927-y

Miles, S., Swift, L., & Leinster, S. J. (2012). The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM): A review of its adoption and use. Medical Teacher, 34(9), e620–e634. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.668625

O’Brien, A. P., Chan, T. M. F., & Cho, M. A. A. (2008). Investigating nursing students’ perceptions of the changes in a nursing curriculum by means of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) Inventory: Results of a cluster analysis. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 5(1), Article 25. https://doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1503

Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (1999). Understanding learning and teaching: The experience in higher education. McGraw-Hill Education.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Riquelme, A., Oporto, M., Oporto, J., Méndez, J. I., Viviani, P., Salech, F., Chianale, J., Moreno, R., & Sánchez, I. (2009). Measuring students’ perceptions of the educational climate of the new curriculum at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Performance of the Spanish translation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). Education for Health, 22(1), Article 112.

Roff, S., McAleer, S., Harden, R. M., Al-Qahtani, M., Ahmed, A. U., Deza, H., Groenen, G., & Primparyon, P. (1997). Development and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). Medical Teacher, 19(4), 295–299.

Stormon, N., Ford, P. J., & Eley, D. S. (2019). DREEM-ing of dentistry: Students’ perception of the academic learning environment in Australia. European Journal of Dental Education, 23(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12384

Till, H. (2004). Identifying the perceived weaknesses of a new curriculum by means of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) Inventory. Medical Teacher, 26(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590310001642948

*Dr Maria Concepcion Bartolome

Basic Clinical Medicine Department

School of Medical Sciences (SMS)

College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences (CMNHS),

Fiji National University

Hoodless House, Brown St. Suva, Fiji Islands

+679 3311700

Email: maria.bartolome@fnu.ac.fj

Submitted: 5 June 2024

Accepted: 30 October 2024

Published online: 1 April, TAPS 2025, 10(2), 71-81

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-2/OA3424

Mary Xiaorong Chen1, Meredith Tsz Ling Yeung1, Nur Khairuddin Bin Aron2, Joachim Wen Jie Lee3 & Taylor Yutong Liu4

1Health and Social Sciences Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2Rehabilitation Department, Jurong Community Hospital, Singapore; 3Rehabilitation Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 4Clinical Support Services Department, National University Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Transitioning from a novice physiotherapist (NPT) to an independent practitioner presents significant challenges. Burnout becomes a risk if NPTs lack adequate support for learning and coping. Despite the importance of this transition, few studies have explored NPTs’ experiences in Singapore. This study aims to investigate the transitional journey of NPTs within this context.

Methods: Conducted as a descriptive phenomenological study, researchers collected data through semi-structured online interviews with eight NPTs from six acute hospitals across Singapore. Simultaneous data analysis during collection allowed for a reflexive approach, enabling the researchers to explore new facets until data saturation. Thematic analysis was employed and complemented by member triangulation.

Results: The challenges NPTs encountered include seeking guidance from supervisors, managing fast-paced work and patients with complex conditions. Additionally, NPTs grappled with fear of failure, making mistakes and self-doubt. They adopted strategies such as assuming responsibility for learning, developing patient-focused approaches, and emotional resilience. However, a concerning trend emerged with the growing emotional apathy and doubts about their professional choice.

Conclusion: This study provides a nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by NPTs during their transition. The workplace should be viewed as a learning community, where members form mutual relationships and support authentic learning. Recommendations include augmenting learning along work activities, fostering relationships, ensuring psychological safety, and allowing “safe” mistakes for comprehensive learning.

Keywords: Novice Physiotherapist Transition in Practice, Clinical Learning and Supervision, Mentoring, Emotional Resilience and Support, Safe Learning Environment

Practice Highlights

- Gradual assumption of responsibilities helps Novice Physiotherapists (NPTs) build competence.

- Learning should be augmented along with work activities.

- It is important to support NPTs to overcome the fear of failure and self-doubt.

- NPTs’ ability to negotiate learning and emotional resilience are essential.

- Trusting relationships and a safe learning environment are essential to NPTs’ learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

Novice Physiotherapists (NPTs) are physical therapy graduates with two years or less of clinical practice, and during this transition to independent practitioners in clinical settings, they face significant challenges (Martin et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2018). Despite the expectation of competence, concerns persist regarding NPTs’ abilities in various aspects of their practice.

It was reported that the persistent challenges faced by NPTs include managing workload, handling patients with complex conditions, seeking adequate guidance, and navigating relationship dynamics (Latzke et al., 2021; Mulcahy et al., 2010). One critical issue is the oversight of NPTs’ “new” status, leading to their assignment of patient loads comparable to experienced practitioners. Consequently, NPTs find themselves under tremendous stress in managing patients with complex conditions and diverse sociocultural backgrounds beyond their abilities (Stoikov et al., 2021; Wells et al., 2021). Workloads and time constraints hinder the development of meaningful connections between NPTs and supervisors, affecting teaching and coping abilities (Rothwell et al., 2021). In the busy clinical environment, NPTs cannot solely rely on their assigned supervisors, the support from senior colleagues around them along their developmental journey is necessary. Unfortunately, studies suggest that inadequate support and guidance from senior colleagues exacerbate these challenges (Forbes et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2021; Phan et al., 2022; Stoikov et al., 2020; Te et al., 2022).

Additionally, as NPTs are inexperienced, communicating with patients, their families, and other healthcare professionals present a significant hurdle in clinical decision-making (Atkinson & McElroy, 2016). The pressure to make informed clinical decisions, drawing upon extensive knowledge and experience, contributes to job-related stress and feelings of inadequacy among NPTs (Adam et al., 2013).

Job stress-related symptoms, including exhaustion, self-doubt, and depression, further impact NPTs’ well-being. These symptoms, akin to burnout, result from a mismatch between the worker’s performance and job expectations (Brooke et al., 2020; Pustułka-Piwnik et al., 2014). Studies reveal that burnout affects approximately 65% of physiotherapists in Spain (Carmona-Barrientos et al., 2020). This is a concern as burnout was found to be correlated positively with intentions to leave the profession (Cantu et al., 2022), leading to low morale, and compromised patient service quality (Evans et al., 2022; Lau et al., 2016).

Studies suggest that ill-prepared PTs may feel inadequate and lack confidence in making decisions which can negatively influence their clinical management and support for patients’ needs. For example, PTs who lack the ability to adopt a person focused approach might not be able to manage patients with chronic lower back pain effectively (Gardner et al., 2017). Furthermore, such impacts are subtle, difficult to pinpoint, and can result in poor care quality, low patient satisfaction and staff morale (Gardner et al., 2017; Holopainen et al., 2020; Marks et al., 2017).

In Singapore, the healthcare system is bifurcated into public and private sectors. Public hospitals, which fall under government ownership (Ministry of Health, 2023), are pivotal in delivering healthcare services. These hospitals are organised into three distinct clusters, each serving specific regions within the country. Table 1 for a comprehensive list of public hospitals categorised by their respective clusters.

|

Healthcare Clusters |

Hospitals |

|

National Healthcare Group (NHG) |

Tan Tock Seng Hospital |

|

|

Khoo Teck Puat Hospital IMH (Institute of Mental Health) |

|

National University Health System (NUHS) |

National University Hospital |

|

|

Ng Teng Fong General Hospital |

|

|

Alexandra Hospital |

|

SingHealth |

Singapore General Hospital |

|

|

Changi General Hospital |

|

|

Sengkang General Hospital |

|

|

National Heart Centre |

|

|

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital |

Table 1. Public hospitals in Singapore

At the beginning of 2022, Singapore had 165 physiotherapists under conditional registration, with 97 (59.51%) employed by public hospitals (Allied Health Professions Council, 2022). Novice Physiotherapists (NPTs) require close supervision and guidance from their clinical mentors/supervisors. During their initial phase, all NPTs undergo a 13-month conditional registration before qualifying for a full registration status. With an average 200 PT students graduate from the Singapore Institute of Technology each year, coupled with the NPTs under conditional registration, the supervisory tasks shared by the limited pool of PT Supervisors are tremendous. Besides their supervisory roles, PT supervisors are also clinically responsible to managing patients and workplace administrations.

A recent study conducted in Singapore explored the perspectives of allied health practitioners, including physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and radiographers, regarding clinical supervision in tertiary hospitals (Lim et al., 2022). The findings revealed that newly qualified allied health practitioners often faced challenges related to insufficient clinical supervision, emotional support, and professional guidance from their supervisors. Contributing factors included time constraints and staffing limitations (Lim et al., 2022). These findings underscore the need for a deeper understanding of the experiences encountered by NPTs during their early clinical practice.

Despite the significance of this issue, no further research has specifically explored the clinical experiences of NPTs in Singapore. Among NPTs, those working in acute public hospitals constitute a compelling subgroup, representing 59.51% of the NPT workforce. Additionally, acute public hospitals provide multidisciplinary services, making them ideal settings for studying the challenges faced by NPTs. Therefore, this study aims to delve into the experiences of NPTs within Singapore’s acute public hospitals.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design

The study employed a descriptive phenomenological approach to understand participants’ lived experiences (Neubauer et al., 2019). In this approach, researchers intentionally set aside their preconceptions and assumptions in this method, allowing the data to speak for itself (Shorey & Ng, 2022). Giorgi (1997) highlights that descriptive phenomenology is particularly well-suited for phenomena that lack extensive literature evidence. Given the limited research on NPTs’ transitional experiences in Singapore, adopting descriptive phenomenology is appropriate for this study.

B. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board (Approval number: 2022033). The participant information sheet was emailed to prospective participants for recruitment. Written informed consent was obtained. All researchers had no authoritative relations with the participants. Participants were assured that their participation was anonymous and voluntary.

C. Participant Recruitment

Adopting a convenient and snowballing sampling approach, the researchers approached NPTs and sought referrals for further recruitment. The inclusion criteria were: (1) NPTs who had less than two years of clinical practice after graduation; (2) NPTs who were working in acute public hospitals. The exclusion criteria were: (1) NPTs who had prior working experience in healthcare; (2) NPTs who were not working in acute public hospitals.

The recruitment email sought voluntary return of information such as place of practice, date of employment, alma mater, and previous work experience in healthcare. A follow-up email was sent to arrange for the online semi-structured interview. Eight participants from six acute public hospitals were included in the study.

|

Participant* |

Gender |

Race |

Age (Years) |

Hospital * |

Length of Employment |

|

Alpha |

Female |

Chinese |

26 |

Hospital G |

348 days |

|

Beta |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital E |

419 days |

|

Charlie |

Male |

Malay |

27 |

Hospital I |

310 days |

|

Delta |

Female |

Chinese |

27 |

Hospital K |

432 days |

|

Epsilon |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital G |

452 days |

|

Foxtrot |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital G |

515 days |

|

Golf |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital E |

531 days |

|

Hotel |

Female |

Chinese |

24 |

Hospital A |

531 days |

Table 2. Participant demographic information

* Participants’ names and hospitals are given pseudonyms to maintain anonymity.

D. Data Collection

Data were collected by researchers NK, JL and TL, who were final-year physiotherapy students. The interview guide was developed based on the literature review and validated by MC and MY, both are experienced in clinical supervision. The researchers conducted pilot interviews to test the interview guide and their approaches. The interview guide is presented in Appendix 1.

With the semi-structured approach, the researchers had the flexibility to follow up on questions. Open-ended questions were used to mitigate the potential issues of over-leading the discussion (Green & Thorogood, 2018). MC provided feedback to NK, JL and TL after each interview. The researchers kept a reflexive journal to record their thoughts, feelings, knowledge and perceptions of the research process (Chan et al., 2013).

Interviews were conducted between July and November 2022 over Zoom. The interview recordings were transcribed. The research team reviewed the video recordings and the aspects needed to follow up with the next interview (Ryan et al., 2009). Data saturation was reached by the fifth interview. Three more interviews were done to ensure no new findings. Each interview lasted between 33 to 110 minutes, with a mean duration of 77 minutes.

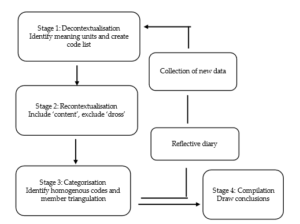

E. Data Analysis

The data were analysed using an inductive approach with no predetermined structure, framework, or theory simultaneously with data collection (Burnard et al., 2008). The four stages include decontextualisation, recontextualisation, categorisation, and compilation (Bengtsson, 2016) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data analysis process (Adapted from Bengtsson, 2016)

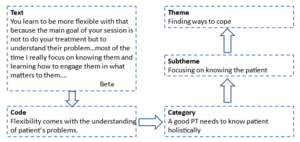

For decontextualisation, NK, JL and TL read interview transcripts and code the text into smaller meaning units independently. A meaningful unit is the smallest unit that can be defined as sentences or paragraphs containing aspects related to one another and addressing the aim of the study (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. An example of the analysis process

For recontextualisation, the researchers read the original text alongside the final list of codes. The unmarked text was included if it was relevant to the research question. For unrelated text, it was labelled as “dross” and excluded (Bengtsson, 2016). Discrepancies were resolved through consulting MC and MY. Codes were reviewed to identify patterns and similarities and then categorised into themes and sub-themes. The rigor of analysis was ensured through researcher triangulation (Lao et al., 2022). Qualitative data analysis software Quirkos was used to assist with the analysis.

III. RESULTS

From the data analysis based on the dataset (Chen, 2023), two themes were synthesised as shown in Table 3.

|

Themes |

Subthemes |

|

Challenges from multiple aspects |

Challenges in getting guidance from the Supervisors |

|

Challenges from the pace and nature of the work |

|

|

Challenges from patient |

|

|

Fear and self-doubt |

|

|

Finding ways to cope |

Be intentional and responsible in learning |

|

Focusing on knowing the patient and managing time |

|

|

Emotional resilience and emotional apathy |

Table 3. Themes and subthemes

These themes are supported by subthemes depicting the multiple dimensions of challenges and NPTs’ coping strategies.

A. Challenges from Multiple Aspects

This theme is supported by four sub-themes, indicating NPTs encountered challenges from many aspects of their practice context.

1) Challenges in getting guidance from the supervisors: NPTs reported that they were scheduled to manage patients independently soon after their orientation, often at a different location from their supervisors. Working in different locations to manage different groups of patients posed difficulties for NPTs to learn from their supervisors. Even if the clinics were nearby, their supervisors had to stop their clinics temporarily to guide the NPTs, which caused the accumulation of patients on the waiting list and prolonged clinical hours. Knowing this would happen, NPTs were reluctant to consult their supervisors.