Using simulation and inter-professional education to teach infection prevention during resuscitation

Submitted: 21 February 2020

Accepted: 13 July 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 93-108

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/OA2229

Kah Wei Tan1, Hwee Kuan Ong2 & Un Sam Mok3

1Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore; 2Department of Physiotherapy, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 3Division of Anaesthesiology and Peri-operative Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: During resuscitations, healthcare professionals (HCPs) find balancing the need for timely resuscitation and adherence to infection prevention (IP) measures difficult. This study explored the effects of an innovative teaching method, using in-situ simulation and inter-professional education to enhance compliance to IP through better inter-professional collaboration.

Methods: The study was conducted in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) in a 1200-beds teaching hospital. HCPs working in the SICU were conveniently allocated to the intervention or control group based on their work roster. The intervention group attended an in-situ simulated scenario on managing cardiac arrest in an infectious patient. The control group completed the standard institution-wide infection control eLearning module. Outcomes measured were: (a) attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork [TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (TAQ)], (b) infection prevention knowledge test, (c) self-evaluated confidence in dealing with infectious patients and (d) intensive care unit (ICU) audits on infection prevention compliance during actual resuscitations.

Results: 40 HCPs were recruited. 29 responded (71%) to the pre- and post-workshop questionnaires. There were no significant differences in the TeamSTEPPS TAQ and infection prevention knowledge score between the groups. However, ICU audits demonstrated a 60% improvement in IP compliance for endotracheal tube insertion and 50% improvement in parenteral medication administration. This may be attributed to the debriefing session where IP staff shared useful tips on compliance to IP measures during resuscitation and identified threats that could deter IP compliance in SICU.

Conclusion: Learning infection prevention through simulated inter-professional education (IPE) workshops may lead to increased IP compliance in clinical settings.

Keywords: Inter-Professional Education, Simulation Infection Control, Resuscitation, Inter-Professional Teamwork

Practice Highlights

- Use of a simulated scenario to improve infection prevention during resuscitation.

- Improving attitudes towards inter-professional collaboration amongst healthcare professionals.

- Evaluating the efficacy of a simulated scenario through clinical audit.

I. INTRODUCTION

Adherence to infection prevention is paramount in the intensive care unit (ICU) as hospital acquired infections in the critically ill are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, length of stay and healthcare cost (Gandra & Ellison, 2014). However, during resuscitations, healthcare professionals (HCPs) may experience difficulty in balancing the need for resuscitation and adherence to infection prevention guidelines, resulting in suboptimal compliance to basic infection prevention measures (Steinemann et al., 2016). Moreover, resuscitation is a time-critical endeavour that requires good collaboration in a team comprising of different HCPs fulfilling different roles with different priorities, and lapses in teamwork may arise in a team comprising of HCPs with different roles and priorities (Barr, Koppel, Reeves, Hammick, & Freeth, 2009).

Inter-professional education (IPE) is defined as “occasions when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and quality of care” by the Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) (Steinert, 2005). It is known to improve patient safety through improving communication, understanding and knowledge to encourage active participation from different HCPs (Oandasan, 2007; Wong, Lee, Allen, & Foong, 2020). Research has shown that active collaboration amongst HCPs in the workplace resulted in improved patient outcomes and provider satisfaction (Wagner, Parker, Mavis, & Smith, 2011). Previous studies had investigated the outcomes of using IPE workshops to teach infection prevention in non-emergency clinical settings or using standardised patients, and concluded that knowledge and confidence in infection prevention and inter-professional teamwork had improved (Mundell, Kennedy, Szostek, & Cook, 2013).

Currently, infection prevention education in our institute is didactic and web-based. Although this method is effective in disseminating information, there are no opportunities to learn with different HCPs or apply knowledge to real-life scenarios. On the basis that resuscitation is traditionally taught using simulation and has been proven to be highly effective (Perkins, 2007), we developed an IPE simulation workshop on infection prevention during resuscitation.

We hypothesised that the in-situ simulation workshop involving different HCPs will result in improved attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork and improved compliance to infection prevention guidelines, compared to our standard institutional infection control (IC) education.

II. METHODS

A. Study Population

We conducted a non-randomised experimental study amongst HCPs working in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) of the Singapore General Hospital (SGH). All HCPs working in the SICU were eligible to participate in the study. There were no exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained from all participating HCPs. Information on participants’ profession, the year they obtained their professional qualification, the number of years they had worked in critical care and prior experience in simulation training were collected. HCPs from Anaesthesiology, Nursing, Physiotherapy, Pharmacy, Speech and Language Therapy, Dietetics and Infection Prevention were involved. A working day was picked to run the workshop and HCPs on duty that day were allocated to the intervention group, while those there were not on duty were assigned to the control group.

B. In-Situ Simulation Workshop

Participants in the intervention group (n=25) underwent a two-hour in-situ simulation workshop in the SICU on the scenario of a cardiac arrest in an infectious patient (Annex A). The training faculty comprised of HCPs from various professions such as Anaesthesiology, Nursing, Physiotherapy, Pharmacy, Speech and Language Therapy, Dietetics and Infection Prevention. Each workshop consisted of HCPs from five to seven different professions. The learning outcomes of the workshop were (i) to practice infection prevention precautions for transmission-based infections during resuscitations and (ii) to improve attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork during a crisis situation.

The workshop was designed based on Kolb’s experiential learning theory (Kolb & Fry, 1975), which is a four-stage learning cycle consisting of (i) concrete experience, (ii) reflective observation, (iii) abstract conceptualisation and (iv) active experimentation. Concrete experience was facilitated through in-situ simulation where participants experienced real-life constraints of resuscitating an infectious patient. Following the simulation, a debrief was held by the faculty that facilitated reflective observation and abstract conceptualisation. Learning points discussed include (i) issues faced in adhering to infection prevention guidelines in a resuscitation setting, (ii) inter-professional teamwork and (iii) threats that could deter IC compliance in SICU. The final stage, active experimentation, was facilitated through actual application of learning points surmised from the workshop, and evaluated through real-time ICU audits.

C. Evaluation of Outcomes

Evaluation of the effectiveness and impact of the workshop was done in accordance with Kirkpatrick’s evaluation framework (Kirkpatrick, 1994), which emphasised the need to go beyond the immediate reactions of participants by assessing them on four different levels, which are (i) Reaction, (ii) Learning, (iii) Behaviour and (iv) Results. “Reaction” was evaluated through the post-workshop questionnaire and participants’ responses in the post-workshop debrief with regards to the effectiveness of simulated workshops in improving inter-professional teamwork and encouraging compliance to infection prevention guidelines. The second level, “Learning”, was evaluated by discussing learning points of the workshop in the debrief, and getting participants to note down their most important takeaways regarding infection prevention and IPE in the post-workshop questionnaire. “Behavioural changes” were assessed through a real-time observational study that assessed participants’ ability to observe proper infection prevention practices during actual resuscitations in the SICU. Results, the fourth level, were difficult to evaluate due to the small sample size that we recruited.

D. Outcomes of Study

There are two primary outcomes of this study: (i) attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork and (ii) infection prevention knowledge and practices.

Changes in attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork were assessed using the TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (TAQ 1.0), based on scores in the following subcategories; Team Structure, Leadership, Situation Monitoring, Mutual Support and Communication (Appendix 1). Qualitative comments on key learning points with regards to teamwork were also collected during the debriefing sessions.

Changes in infection prevention knowledge and practice were assessed in five ways:

- An infection prevention self-evaluation questionnaire on a 5-point Likert Scale (Appendix 2).

- A multiple-choice quiz developed by the Institutional Infection Prevention Nurse Educators (Appendix 3A and 3B).

- Questionnaire on effectiveness of the simulation (for participants in the intervention group only) (Appendix 4).

- Qualitative feedback on the learning points concerning infection prevention. (Appendix 5).

- Clinical audit data that evaluated compliance to infection prevention guidelines during resuscitations in the SICU. Two months after the simulation workshop, the data was collected by a trained hospital-based infection prevention team based on real-time observations. The audit checklist assessed proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE), hand hygiene, administration of parenteral medications and insertion of endotracheal tube (ETT).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Mac, Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were analysed using the t-test, and categorical variables were analysed using the Fisher and Chi square test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant.

III. RESULTS

The study recruited a total of 40 HCPs. Of the 40 clinical staff working in the SICU asked to rank their responses, 29 (71%) responded to the pre- and post-workshop TAQ, self-evaluation of infection prevention knowledge and infection prevention knowledge quiz. Healthcare professions represented included doctors (31%), nurses (34%), pharmacists (10%), physiotherapists (10%), speech and language therapists (10%) and dieticians (3%).

The intervention and control groups were not significantly different in terms of the number of years post-graduation, years of working experience in critical care and the number of simulated training sessions they have attended, excluding basic cardiac life support (BCLS) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). Similarly, there were no significant differences in self-evaluation of infection prevention knowledge and infection prevention scores at baseline. However, we noted significantly higher scores in the control group in Team Structure (mean difference=2.76), Leadership (mean difference =3.8), and Communication (mean difference=2.54; Table 1).

|

|

Intervention [Range] (n=16) |

Control [Range] (n=13) |

P-value |

|

|

Mean no. of years since graduation |

8.65 [4-23] |

8.67 [5-20] |

0.996 |

|

|

Mean no. of years in critical care |

3.78 [0-10] |

5.13 [0-15] |

0.413 |

|

|

Mean no. of prior simulation training sessions (excluding BCLS/ACLS) |

1.52 [0-15] |

2.33 [0-12] |

0.474 |

|

|

Self-evaluation of infection prevention knowledge |

13.3 [10-20] |

14.6 [8-19] |

0.179 |

|

|

Infection prevention baseline MCQ scores |

5.47 [5-6] |

5.78 [5-6] |

0.103 |

|

|

TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire 2.0 |

||||

|

|

Team Structure |

23.04 [19-30] |

25.80 [20-30] |

0.046* |

|

Leadership |

24.13 [18-29] |

27.93 [21-30] |

0.009* |

|

|

Situation Monitoring |

23.43 [20-30] |

25.73 [21-30] |

0.100 |

|

|

Mutual Support |

18.91 [15-26] |

19.33 [15-27] |

0.678 |

|

|

Communication |

22.39 [19-29] |

24.93 [20-30] |

0.042* |

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the Intervention and Control groups

A. Inter-Professional Teamwork

Within the intervention group, there were no significant changes between pre- and post-workshop TeamSTEPPS TAQ scores in most subcategories, with the exception of an improvement in post-workshop Mutual Support scores (mean difference=3.21), which translated to a 17.0% increase from baseline (Table 2). The lack of a significant change in most subcategories could possibly be due to the already high baseline scores prior to the workshop.

|

|

Pre-workshop mean (SD) [Range] (n=16) |

Post-workshop mean (SD) [Range] (n=16) |

Mean difference |

P-value |

Percentage increase/% |

|

Self-evaluation of infection prevention knowledge |

13.57 (3.32) [10-20] |

14.71 (1.90) [9-19] |

1.14 |

0.230 |

8.4 |

|

Infection prevention quiz scores |

5.85 (0.38) [5-6] |

4.85 (0.69) [4-6] |

-1.00 |

0.000 |

-17.1 |

|

Team Structure |

24.14 (2.69) [19-30] |

25.36 (2.50) [21-30] |

1.22 |

0.058 |

5.1 |

|

Leadership |

25.64 (2.76) [18-30] |

25.9 (2.55) [24-30] |

0.26 |

0.780 |

1.0 |

|

Situation Monitoring |

24.71 (3.29) [18-30] |

25.36 (3.10) [24-30] |

0.65 |

0.272 |

2.6 |

|

Mutual Support |

18.93 (2.43) [18-30] |

22.14 (2.03) [18-28] |

3.21 |

0.002 |

17.0 |

|

Communication |

23.43 (2.56) [20-30] |

23.86 (2.45) [22-30] |

0.43 |

0.551 |

1.8

|

Table 2. Comparison of pre- and post-workshop scores within the intervention group

The intervention group also had greater percentage increases in the TAQ 2.0 Team Structure, Leadership and Communication sub-categories compared to the control group (Table 3).

|

|

Intervention (n=16) |

Control (n=13) |

P-value |

||

|

|

Mean change (SD) |

Percentage change/% |

Mean change (SD) |

Percentage change/% |

|

|

Change in scores for self-evaluation of infection prevention knowledge |

1.14 (3.39) |

8.4 |

0.78 (0.97) |

5.2 |

0.758 |

|

Change in infection prevention scores |

-1.00 (0.71) |

-17.1 |

-1.63 (1.19) |

-29.0 |

0.145 |

|

Change in scores for Team Structure |

0.42 (1.86) |

5.1 |

0.67 (1.45) |

1.3 |

0.661 |

|

Change in scores for Leadership |

-0.42 (2.35)

|

1.0 |

-0.09 (1.38) |

-3.1 |

0.693 |

|

Change in scores for Situation Monitoring |

1.00 (2.00) |

2.6 |

0.27 (1.35) |

2.6 |

0.323 |

|

Change in scores for Mutual Support |

4.33 (2.19) |

17.0 |

3.18 (3.82) |

25.3 |

0.380 |

|

Change in scores for Communication |

0.33 (3.17) |

1.8 |

0.45 (2.34) |

1.4 |

0.919 |

Table 3. Comparison of changes in pre- and post-workshop scores between the Intervention and Control groups

The most common learning point for IPE was the importance of learning the different roles and capabilities that different HCPs can play and the need to involve other HCPs to ensure an effective resuscitation effort. The learning points listed support change in perceptions related to interprofessional roles that the quantitative scale did not capture.

“The workshop improves knowledge of the roles that other healthcare professionals are able to perform, for example, a physiotherapist being qualified to help in CPR during resuscitation.”

(Nursing participant, ID 16)

B. Infection Prevention Knowledge and Practices

Although there were no statistically significant differences between the groups, better infection prevention scores were noted in the intervention group. The intervention group had a percentage increase of 3.2% (8.4% vs 5.2%) in self-evaluated infection prevention knowledge. The questions on infection prevention knowledge were supposed to be of similar difficulty, and we avoided repeating the same set of questions, as we did not want participants to discuss or look up the answers. For both groups, there was a decrease in infection prevention knowledge scores post-workshop; however, there was a smaller decrease in the intervention group (-17.1%) compared to the control group (-29.0%) (Table 3). We speculate that this may be due to the post-workshop questions being more difficult compared to the pre-workshop questions. Another reason that may have contributed to the decrease in scores is the limited number of questions (n=6), which may have confounded our results.

The participants shared a rich diversity of infection prevention learning points during the debrief session. Examples included correct steps in the donning of personal protective equipment, strategies to clean the intravenous (IV) injection hub quickly and effectively, and identification of threats that deterred proper infection prevention compliance during the simulation such as the lack of a disposable dish on the resuscitation trolley to keep intravenous drugs and intubation equipment clean. The most common learning point for infection prevention was the importance of adhering to infection prevention practices during resuscitation such as the accurate administration of parenteral medications. The learning points listed support change in perceptions related to interprofessional roles that the quantitative scale did not capture.

“The importance of practicing infection prevention measures such as the need for changing soiled gloves in between administering parenteral medications, but yet not compromising on resuscitation.”

(Physiotherapist, ID 8)

The clinical audit conducted after the simulation workshop showed that compliance rates in accurate parenteral medication administration improved by 50%, while compliance rates in ETT insertion improved by 60% post-workshop, compared to pre-workshop performance (Table 4).

|

|

Pre-workshop |

Post-workshop |

Percentage change in compliance rates/% |

||

|

|

Number of instances of compliance |

Number of instances of non-compliance |

Number of instances of compliance |

Number of instances of non-compliance |

|

|

PPE |

24 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

24 (96%) |

1 (4%) |

-4 |

|

Hand hygiene |

10 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 |

|

Parenteral medication administration |

6 (50%) |

6 (50%) |

9 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

50 |

|

ETT insertion |

2 (40%) |

3 (60%) |

10 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

60 |

Table 4. Comparison of compliance rates to infection prevention during real-time resuscitations pre- and post-workshop

IV. DISCUSSION

The study was designed, conducted and written before the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the pandemic, there had been some changes in infection prevention guidelines in aerosol general procedures such as tracheal intubation (Perkins, et al., 2020), which was not reflected in our study. Our study had highlighted the importance of using simulation and inter-professional collaboration to enhance infection prevention education, and these were also emphasised in many publications regarding infection prevention during the pandemic (Wong, et al., 2020). For example, there had been recommendations of using a buddy system for PPE donning and doffing, and using high fidelity simulation to prepare for the COVID-19 crisis (Bricknell, Hodgetts, Beaton, & McCourt, 2016). However, many of these publications were reviews and opinions rather than research studies (Foong, et al., 2020; Lim, Wong, Teo, & Ho, 2020).

To our knowledge, there are no publications on the use of in-situ simulation to teach infection prevention during resuscitations in an IPE setting. Current literature evaluating the impact of simulated IPE workshops in teaching infection prevention had mixed results with regards to the effectiveness of such workshops in improving attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork and enhancing compliance rates to infection prevention practices. In the study by Luctkar-Flude et al. (2016), there was significant improvement in infection prevention knowledge, but little change in inter-professional teamwork. Although knowledge related to aseptic technique improved significantly immediately post-workshop, long-term retention was poorer (Wagner, et al., 2011).

A. The Utility of Simulation in Improving Infection Prevention

Our results from the clinical audit conducted during actual resuscitations in the SICU demonstrated a large improvement after the workshop in accurate parenteral medication administration and ETT insertion. This finding supports the hypothesis that an inter-professional simulated workshop is more effective than traditional didactic web-based methods in improving adherence to infection prevention practices, which could be due to three added elements present in simulated workshops.

Firstly, simulation provides interaction amongst different HCPs and enables collaborative learning in small groups (Dolmans, Michaelsen, van Merriënboer, & van der Vleuten, 2015). Secondly, the debriefing process promotes reflective learning and provides real-time feedback (Ziv, Wolpe, Small, & Glick, 2003). Thirdly, the learning is contextualized as participants learn infection prevention principles that are embedded in authentic clinical scenarios, and simulated cardiac arrest in an infectious patient is a common scenario that reflects the reality of practice (Morison & Jenkins, 2007).

Simulation also enables participants to discover innovative solutions, thereby enabling optimal adherence to infection prevention protocols while ensuring a timely resuscitation response with limited manpower. An example of one of the interesting solutions discussed include the designation of specific roles during resuscitation, such as assigning one HCP to be in charge of the airway and another to be in charge of administering intravenous drugs so as to avoid contamination.

B. Encouraging Inter-Professional Teamwork Through Simulation

Simulated scenarios with a focus on IPE also encourage active engagement and collaboration amongst participants, which had been demonstrated to result in improved attitudes towards teamwork (Huitt, Killins, & Brooks, 2015). During the debriefing process, study investigators facilitated the discussion to allow HCPs from different specialties to give feedback and volunteer information on how they could better contribute to the resuscitation effort and work more cohesively as a team, thereby enabling HCPs to discover more about the capabilities of their fellow colleagues. This discussion helps to create a sense of shared purpose within teams (Freytag, Stroben, Hautz, Eisenmann, & Kammer, 2017), which is a defining characteristic of an effective team (Drinka & Clark, 2000), and also reinforces the idea that a team can often achieve what an individual cannot.

In our debriefing, the participants noted the importance of learning the different roles and capabilities that different HCPs can play and the need to involve other HCPs to ensure an effective resuscitation effort, which can subsequently translate to a positive change in patient care and collaborative practice (Hammick, Freeth, Koppel, Reeves, & Barr, 2007). For example, the nursing and medical participants did not realise that physiotherapists, pharmacists and speech and language therapists are BCLS trained and can perform effective chest compression, and the medical participants did not realise nurses can perform cardiac defibrillation during a cardiac arrest. Better collaboration and understanding of other HCPs’ roles can improve task delegation to fully maximise available manpower, and aids in crisis resource management.

C. Debriefing–An Essential Component of a Simulated Workshop

According to the experiential learning style theory (Kolb & Fry, 1975), reflective practice is an integral component that allows learners to fully integrate the learning experience. It allows HCPs to transit from merely experiencing the simulation to deriving critical learning points (Savoldelli, et al., 2006), as constructive discussion and feedback allow participants to better understand potential areas of improvement and reinforces proper infection prevention practice (Gerolemou, et al., 2014). The importance of feedback and discussion is aptly demonstrated in our study, with participants noting that accurate parenteral medication administration was one of their main takeaways from the debriefing process, and there being a subsequent 50% improvement in parenteral medication administration in our observational study.

An effective debriefing process was facilitated through the creation of a non-threatening environment by using open-ended questions, positive reinforcement, constructive feedback and active engagement of all HCPs present (Fanning & Gaba, 2007). While there are many debriefing tools present such as the Organ Specific Autoimmune Disease (OSAD) debriefing tool (Ahmed, et al., 2012), and Advocacy Inquiry (Gururaja, Yang, Paige, & Chauvin, 2008), we believe that the cornerstone of a successful debrief is through the creation of an environment that allows participants to freely voice their queries and concerns, and subsequent discussion to tease out relevant learning points that serve as important takeaway messages.

D. Other Observations

Interestingly, we noted significant differences in Team Structure and Leadership between the Intervention and Control groups in the pre-test questionnaire. This could be due to difference in number of years that the intervention and control groups have worked in SICU, with the intervention group having worked a mean number of 3.78 years compared to the control group’s 5.13 years, although this difference was not statistically significant. Studies have shown that HCPs who have worked together for longer periods of time and on a daily basis are more likely to develop trust and confidence in their teams (Bosch & Mansell, 2015). Less-experienced healthcare staff may feel more uncomfortable with inter-professional teamwork compared to more experienced staff, further highlighting the importance of increasing exposure to IPE for younger HCPs.

E. Challenges Encountered in the Implementation of a Simulated Infection Prevention IPE Workshop

The conception and organisation of an infection control workshop that incorporates both simulation and IPE improved our understanding of existing challenges to the development of a coherent curriculum and implementation of simulated workshops (Buckley, et al., 2012). There were numerous challenges encountered in the implementation of such workshops.

Examples include:

- Simulated workshops are resource intensive. Monthly faculty meetings were held for five months before the workshop, and each workshop required the presence of a HCP from at least five different specialties. In addition, beds in the SICU had to be specially set aside for the workshop to take place.

- Learning outcomes had to be crafted carefully to ensure that all HCPs could benefit from an effective IPE session.

- Faculty development was crucial and the faculty was trained to ensure that the post-simulation debriefing could take place effectively and learning outcomes were met.

- Scheduling conflicts were encountered as implementation of the workshop required HCPs with different work schedules to be present at the same time.

The effectiveness of the workshop could be better evaluated with multiple SICU audits of resuscitations pre- and post-workshop, as this would truly demonstrate translation of learning to real-life practice. However, it is difficult to coordinate logistically. Whenever a real-time resuscitation in the SICU occurred, our hospital-based infection prevention team had to be mobilised within a few minutes without advanced notice to the SICU to conduct the audit on infection prevention compliance during resuscitation, which proved to be challenging.

Nevertheless, these challenges can be resolved if HCPs are strongly committed to better healthcare and our study showed that it is possible to overcome the above-mentioned challenges (Byakika-Kibwika, et al., 2015). We hope that our experience would help shed light on future barriers to implementation of similar in-situ simulated IPE workshops.

F. Plans for the Future

Our study showed that simulation IPE workshops encouraged mutual support amongst different HCPs and improved infection prevention practices during resuscitation. However, implementation of the workshop was costlier and more labour intensive compared to current online video infection prevention education. Currently, we now run in-situ simulations in SICU every month on crisis resource management, and infection prevention is one of the important learning outcomes.

This workshop was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic and there was no limitation on the maximum number of participants. In the future, with the SICU roster having changed to shift work, the workshop will only be conducted amongst HCPs within a particular shift to avoid cross-contamination with other shifts. A larger debrief room may be needed to allow for social distancing as well.

G. Limitations of our study

Limitations of our study include the small sample size, making it difficult to draw generalisations, as the study cannot show any statistically significant difference when comparing the control and intervention groups even though positive trends were observed. Furthermore, longer follow-up is required to evaluate long-term changes in behaviour, attitudes and retention of knowledge.

V. CONCLUSION

Our study showed that learning infection prevention through simulated IPE workshops is an innovative way to teach infection prevention and may lead to increased infection prevention compliance in clinical settings, as demonstrated by the clinical audit conducted. In light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, use of a simulated scenario may help enhance infection prevention practices to limit the spread of transmission-based infections. Simulation may also help improve attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork and collaboration, which are crucial in resuscitations.

Notes on Contributors

Kah Wei Tan is a Medical Officer working with Ministry of Health Holdings (MOHH). Kah Wei Tan performed data collection and data analysis, reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript.

Hwee Kuan Ong is a Senior Principal Physiotherapist in the Department of Physiotherapy, Singapore General Hospital. Hwee Kuan Ong performed data collection and data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

May Un Sam Mok is a Senior Consultant in the Division of Anaesthesiology and Peri-operative Medicine, Singapore General Hospital. May Un Sam Mok developed the methodological framework for the study, designed the study, reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The study is approved by SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB reference: 2016/3001).

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the SICU staff for providing assistance in conducting the survey.

Funding

Funding was obtained from the Academic Medicine Education Institute (AMEI) grant.

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Ahmed, M., Sevdalis, N., Paige, J., Paragi-Gururaja, R., Nestel, D., & Arora, S. (2012). Identifying best practice guidelines for debriefing in surgery: A tri-continental study. American Journal of Surgery, 203(4), 523-529.

Barr, H., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., Hammick, M., & Freeth, D. (2009). Effective Interprofessional Education: Arguments, Assumption & Evidence. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bosch, B., & Mansell, H. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in health care: Lessons to be learned from competitive sports. Canadian Pharmacists Journal, 148(4), 176-179.

Bricknell, M., Hodgetts, T., Beaton, K., & McCourt, A. (2016). Operation GRITROCK: The defence medical services’ story and emerging lessons from supporting the UK response to the Ebola crisis. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 162(3), 169-175.

Buckley, S., Hensman, M., Thomas, S., Dudley, R., Nevin, G., & Coleman, J. (2012). Developing interprofessional simulation in the undergraduate setting: Experience with five different professional groups. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(5), 362-369.

Byakika-Kibwika, P., Kutesa, A., Baingana, R., Muhumuza, C., Kitutu, F. E., Mwesigwa, C., … Sewankambo, N. K. (2015). A situation analysis of inter‑professional education and practice for ethics and professionalism training at Makerere University College of Health Sciences. BMC Research Notes, 8, 598.

Dolmans, D., Michaelsen, L., van Merriënboer, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2015). Should we choose between problem-based learning and team-based learning? No, combine the best of both worlds! Medical Teacher, 37(4), 354-359.

Drinka, T. J. K., & Clark, P. G. (2000). Health Care Teamwork: Interdisciplinary Practice and Teaching. Westport, CT: Auburn House.

Fanning, R. M., & Gaba, D. M. (2007). The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simulation in Healthcare: Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 2(2), 115-125.

Foong, T. W., Ng, E. S. H., Khoo, C. Y. W., Ashokka, B., Khoo, D., & Agrawal, R. (2020). Rapid training of healthcare staff for protected cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the COVID-19 Pandemic. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 125(2), e257–e259.

Freytag, F., Stroben, F., Hautz, W. E., Eisenmann, D., & Kammer, J. E. (2017). Improving patient safety through better teamwork: How effective are different methods of simulation debriefing? Protocol for a pragmatic, prospective and randomised dtudy. (2017). BMJ Open, 7(6), e015977.

Gandra, S., & Ellison, R. T. (2014). Modern trends in infection control practices in intensive care units. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 29(6), 311-326.

Gerolemou, L., Fidellaga, A., Rose, K., Cooper, S., Venturanza, M., Aqeel, A., … Khouli, S. (2014). Simulation-based training for nurses in sterile techniques during central vein catheterization. American Journal of Critical Care, 23(1), 40-48.

Gururaja, R. P., Yang, T., Paige, J. T., & Chauvin, S. W. (2008). Examining the Effectiveness of Debriefing at the Point of Care in Simulation-Based Operating Room Team Training. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

Hammick, M., Freeth, D., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., & Barr, H. (2007). A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME Guide no. 9. Medical Teacher, 29(8), 735-751.

Huitt, T. W., Killins, A., & Brooks, W. S. (2015). Team-based learning in the gross anatomy laboratory improves academic performance and students’ attitudes toward teamwork. Anatomical Sciences Education, 8(2), 95-103.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1994). Evaluation Training Programs: The Four Levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Kolb, D. A., & Fry, R. E. (1975). Toward an Applied Theory of Experiential Learning. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Lim, W. Y., Wong, P., Teo, L., & Ho, V. K. (2020). Resuscitation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learnt from high-fidelity simulation. Resuscitation, 152, 89-90.

Luctkar-Flude, M., Hopkins-Rosseel, D., Jones-Hiscock, C., Pulling, C., Gauthier, J., Knapp, A., … Brown, C. (2016). Interprofessional infection control education using standardized patients for nursing, medical and physiotherapy students. Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice, 2, 25-31.

Morison, S., & Jenkins, J. (2007). Sustained effects of interprofessional shared learning on student attitudes to communication and team working depend on shared learning opportunities on clinical placement as well as in the classroom. Medical Teacher, 29(5), 464-470.

Mundell, W. C., Kennedy, C. C., Szostek, J. H., & Cook, D. A. (2013). Simulation technology for resuscitation training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation, 84(9), 1174-1183.

Oandasan, I. (2007). Teamwork and healthy workplaces: Strengthening the links for deliberation and action through research and policy. HealthcarePapers, 7, 98-103.

Perkins, G. D. (2007). Simulation in resuscitation training. Resuscitation, 73(2), 202-211

Perkins, G. D., Morley, P. T., Nolan, J. P., Soar, J., Berg, K., Olasveengen, T., … Neumar, R. (2020). International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation: COVID-19 consensus on science, treatment recommendations and task force insights. Resuscitation, 151, 145-147.

Savoldelli, G. L., Nalik, V. N., Park, J., Joo, H. S., Chow, R., & Hamstra, S. J. (2006). Value of debriefing during simulated crisis management: oral versus video-assisted oral feedback. Anesthesiology, 105(2), 279-285.

Steinemann, S., Kurosawa, G., Wei, A., Ho, N., Lim, E., Suares, G., … Berg, B. (2016). Role confusion and self-assessment in interprofessional trauma teams. The American Journal of Surgery, 211(2), 482-488.

Steinert, Y. (2005). Learning together to teach together: Interprofessional education and faculty development. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(Suppl 1), 60-75.

Wagner, P. D., Parker, C. J., Mavis, B. E., & Smith, M. K. (2011). An interdisciplinary infection control education intervention: Necessary but not sufficient. The Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 3(2), 203-210.

Wong, J., Goh, Q. Y., Tan, Z., Lie, S. A., Tay, Y. C., Ng, S. Y., … Soh, C. R. (2020). Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: A review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 67, 732-745.

Wong, M. L., Lee, T. W. O., Allen, P. F., & Foong, K. W. C. (2020). Dental education in Singapore: A journey of 90 years and beyond. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(1), 3-7.

Ziv, A., Wolpe, P. R., Small, S. D., & Glick, S. (2003). Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Simulation in Healthcare Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 78(8), 783-788.

*Kah Wei Tan

1 Maritime Square,

#11-25 HarbourFront Centre,

Singapore 099253

Email address: kahwei.tan@mohh.com.sg

Submitted: 2 April 2020

Accepted: 3 June 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 109-113

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/SC2243

Wen Hao Chen1, Shairah Radzi1, Li Qi Chiu2, Wai Yee Yeong3, Sreenivasulu Reddy Mogali1

1Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; 3Singapore Centre for 3D Printing, School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Simulation-based training has become a popular tool for chest tube training, but existing training modalities face inherent limitations. Cadaveric and animal models are limited by access and cost, while commercial models are often too costly for widespread use. Hence, medical educators seek a new modality for simulation-based instruction. 3D printing has seen growing applications in medicine, owing to its advantages in recreating anatomical detail using readily available medical images.

Methods: Anonymised computer tomography data of a patient’s thorax was processed using modelling software to create a printable model. Compared to a previous study, 3D printing was applied extensively to this task trainer. A mixture of fused deposition modelling and material jetting technology allowed us to introduce superior haptics while keeping costs low. Given material limitations, the chest wall thickness was reduced to preserve the ease of incision and dissection.

Results: The complete thoracostomy task trainer costs approximately SGD$130 (or USD$97), which is significantly cheaper compared to the average commercial task trainer. It requires approximately 118 hours of print time. The complete task trainer simulates the consistencies of ribs, intercostal muscles and skin.

Conclusion: By utilising multiple 3D printing technologies, this paper aims to outline an improved methodology to produce a 3D printed chest tube simulator. An accurate evaluation can only be carried out after we improve on the anatomical fidelity of this prototype. A 3D printed task trainer has great potential to provide sustainable simulation-based education in the future.

Keywords: Medical Education, Chest Tube, Thoracostomy, Simulation, 3D Printing

I. INTRODUCTION

Training opportunities in procedures such as chest tube insertions are increasingly limited amidst a growing population of trainees. Yet, the deliberate practice remains essential to improving proficiency and preventing possible complications such as lung parenchymal damage (Hernandez, El Khatib, Prokop, Zielinski, & Aho, 2018). Hence, many institutions have adopted simulation-based training to provide realistic training opportunities while mitigating harm to patients.

Cadaveric and animal models are limited by access and cost, and raise religious and ethical concerns (Kovacs, Levitan, & Sandeski, 2018). In addition, commercial models tend to be very costly (e.g. Trauma-Man® at USD~$25,000). As such, new modalities are desired.

Three-dimensional (3D) printing can accurately recreate anatomical details from imaging data through precision modelling and a wide range of compatible printing materials (Mogali et al., 2018). Together with its decreasing cost, it has become an attractive technology for creating inexpensive and anatomically accurate simulation modalities.

A previous study from the Federal University of Parana, Brazil (Bettega et al., 2019) outlined the development and evaluation of a low-cost chest tube simulator. The bony structures were 3D printed, while the remainder of the model was manually assembled using silicone sheets, foam pads, and balloons.

They compared 2 groups of participants using a porcine rib model, and their 3D printed simulator respectively. They found subjective improvements in confidence and safety amongst both groups and showed no difference between the objective grades. Hence, they concluded that their 3D printed simulator was equivalent to the animal model concerning the simulation of a chest tube placement.

However, there exist many other 3D printing technologies and materials, which can potentially be applied to create superior haptics and anatomical detail. Hence, this paper aims to outline a methodology of integrating multiple 3D printing modalities to create a cost-efficient 3D printed chest tube simulator.

II. METHODS

An anonymised computerized tomography (CT) file of a healthy human thorax (2.5 mm slices thickness) in Digital Communication in Medicine (DICOM) format was downloaded from the databank provided by 3D Slicer (https://www.slicer.org/, Version 4.10.2). The CT data was available freely for research and educational use at the time of this study.

3D Slicer was employed to segment the thoracic bony structures using a radiodensity based threshold algorithm, which traces the bone based on the Hounsfield units. Due to a lack of contrast possibly from the poor resolution of the CT images, we were not able to segment the respective soft tissue layers using thresholding. Hence, the intercostal muscles were manually drawn with the paintbrush function. Intrathoracic organs were all removed to create a central cavity. From initial experimentation, we found that incision and dissection were too difficult to perform if the task trainer was printed at the true thoracic thickness. Hence, a decision was made to thin out the chest wall. At the 4th and 5th intercostal space midaxillary line, the mean chest wall thickness is 39mm (Laan et al., 2016), but our model measured at 18mm at this corresponding anatomical landmark.

Further processing was done to smoothen the contours of the model (see Appendix, A). Subsequently, the anatomical structures were saved as stereolithography (STL) file and exported into Materialise Magics (Version 20 by Materialise, Belgium).

On Magics, cut and Boolean techniques were used to create the replaceable component. This space was demarcated by the 5th to 6th intercostal space, between anterior axillary to the mid axillary line. To create a secure fit for the replaceable piece, a groove was created and reinforced using the cut and punch function which generates teething to maximise friction. The main frame measured 23cm (length) x 19.5cm (width) x 23.5cm (height), while the replaceable part measured 9cm (length x 8.1cm (width) x 0.8cm (height). The Fix Wizard and Shrink Wrap Part functions were used to repair the surface mesh and eliminate holes and loose shells. The models were then exported using IdeaMaker® (Raise3D, USA) and uploaded to the printer.

The model was printed in two parts: the main frame was printed using fusion deposition modelling (FDM). This technology extrudes a continuous filament of melted thermoplastic, repeated by layer based on the design coordinates. Bones were printed with polylactic acid (PLA) which is a rigid material while the intercostal muscles were printed with thermoplastic urethane (TPU) which is a flexible material. Support was printed using PLA. We utilised a dual nozzle extrusion printer (Raise3D Pro 2, Raise3D, USA) to allow us to print the bony and soft tissue simultaneously, thereby increasing convenience. The following settings were used: printing speeds were reduced to 25mm/s, retraction of the TPU extrusion head was disabled, nozzle temperatures were set at 200°C, and build plate temperature was at 65°C. Post-print processing was done to remove the support, with subsequent filing and sanding.

The replaceable part was printed using Objet500 Connex 3 (Stratasys Ltd, Eden Prairie, MN), a multi-material printer utilising material jetting technology. This technology drops liquid photopolymers onto the build tray and simultaneously cures the material using UV light. As such, we can mix plastic and rubber to create hybrid consistencies (Mogali et al., 2018) of varying shore hardness. Two materials were selected to achieve the desired haptics: VeroWhite (FullCure, RGD835) was the stiff plastic photopolymer used for bones, while Tango Plus (FullCure, 930) was the rubber photopolymer used for simulating soft tissue. Support resin (FullCure, 706) was also used for printing. Post-printing processing was required to remove the support resin.

Skin coloured silicone sheets of 5 mm thickness were wrapped around the model using generic superglue. The task trainer was cable tied to stainless steel supports and screwed onto a laminated wood baseplate. Cut sponges were wrapped in duct tape to simulate the lung parenchyma and placed into the central cavity created.

III. RESULTS

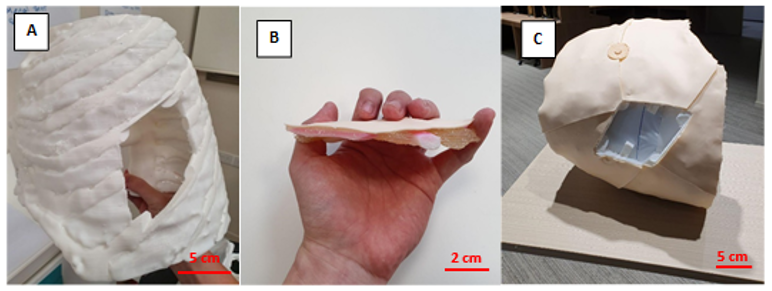

The completed task trainer is shown in Figure 1. Both the main frame and replaceable piece provided simulation for the ribs, intercostal muscles, and skin.

The 3D thoracostomy task trainer costs approximately SGD$130 (or USD$97) (excluding manpower and printer cost)–see Appendix, B). The baseplate and mount were repurposed and did not add to costs.

Note. A = completed hemithorax main frame using FDM printing; B= replaceable piece; C = task trainer without the replaceable piece. Figure 1. Photos of the completed task trainer

The main frame required 676g of polylactic acid and 114g of thermoplastic urethane. The replaceable piece required 30g of VeroWhite, 22g of Tango Plus, and 66g of Support706. It took a total of approximately 118 hours to print the entire task trainer.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our methodology addressed several issues with the model as outlined by the Brazilian team (Bettega et al., 2019). The proposed methodology here required less manual assembly of components, thereby saving time and improving fabrication. By utilising dual extrusion printing, construction was simplified while integrating an additional material for varying consistencies. The creation of a replaceable piece also meant long term savings in the cost of utilising this model. These logistical advantages would make it easier to adopt our proposed task trainer.

Secondly, simple materials such as foam pads and silicone sheets were inferior in simulating human tissue. Our utilisation of material jetting technology with the Objet500 Connex 3 (Stratasys Ltd, Eden Prairie, MN) printer allowed us to blend plastic and rubber materials to better recreate the consistency of human tissue. This technology and blend of materials have been extensively validated in other simulation models (Mogali et al., 2018).

Cost remains an important impedance to the widespread use of simulation in procedural education. We performed a surface comparison of our product against an existing commercial model in use by a local hospital in Singapore (LF03770U by Lifeform, NASCO, USA). The task trainer outlined here (~USD$97) is significantly cheaper than the commercial trainer (~USD$1,800). Also, our material blend provides superior haptics and bony structures in the replaceable component, as compared to a plain silicone insert in the Lifeform model. These should provide improvements in the quality and quantity of simulation opportunities for training physicians.

Unfortunately, we were not able to recreate the anatomical thickness of the thorax given our material limitations at the time of writing. This inaccurate depth of dissection creates a confounding variable when evaluating our task trainer against existing cadaveric or commercial simulators. Hence, an evaluation of this task trainer was withheld to address this limitation in our future prototype. Moving forward, we plan to invite physicians to validate the efficacy of our improved task trainer.

V. CONCLUSION

We have outlined the methodology for creating a 3D printed tube thoracostomy task trainer using a combination of printing technologies. The outlined task trainer could potentially provide superior haptics at a lower cost while improving fabrication. However, an equitable validation against an existing modality of simulation can only be done after we achieve a comparable anatomical fidelity.

In our continued search for sustainable simulation models, 3D printing shows great potential in reproducing anatomical detail with superior cost efficiency. The growing availability of 3D printing infrastructure makes the large-scale adoption of such task trainers ever more realistic. It makes it therefore worthwhile to invest in the creation of the perfect 3D printed task trainer.

Notes on Contributors

Mr. Wen Hao Chen is an undergraduate medical student with the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore. He was involved in the development of the task trainer, along with co-authoring the submitted manuscript.

Dr. Shairah Radzi is a research fellow with the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore. She was involved in the development of the task trainer, along with co-authoring the submitted manuscript.

Dr. Li Qi Chiu is a consultant physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine in Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore. She was involved in the development of the task trainer, along with co-authoring the submitted manuscript.

Assoc. Prof Wai Yee Yeong is the Associate Chair (Students) of the School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She was involved in the development of the task trainer, providing her technical expertise on the 3D printing process, along with co-authoring the submitted manuscript.

Asst. Prof Sreenivasulu Reddy Mogali is the Head of Anatomy and Principal Investigator in Clinical Anatomy and Medical Education at Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore. He was involved in the development of the task trainer, along with co-authoring the submitted manuscript. He serves as the principal investigator.

Ethical Approval

Approved by Nanyang Technological University’s Institutional Review Board (2019-07-017). The CT scans used were anonymised and provided free for education and research use by 3D Slicer (https://www.slicer.org/, Version 4.10.2).

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the staff and faculty of the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for supporting this research; Singapore Centre for 3D Printing, Nanyang Technological University for their technical support.

Funding

This project was funded by the Ministry of Education Research Start-Up Grant, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University Singapore.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

Bettega, A. L., Brunello, L. F. S., Nazar, G. A., De-Luca, G. Y. E., Sarquis, L. M., Wiederkehr, H. de A., … Pimentel, S. K. (2019). Chest tube simulator: Development of low-cost model for training of physicians and medical students. Revista Do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões, 46(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-6991e-20192011

Hernandez, M. C., El Khatib, M., Prokop, L., Zielinski, M. D., & Aho, J. M. (2018). Complications in Tube Thoracostomy: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 85(2), 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001840

Kovacs, G., Levitan, R., & Sandeski, R. (2018). Clinical Cadavers as a Simulation Resource for Procedural Learning. AEM Education and Training, 2(3), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10103

Laan, D. V., Vu, T. D. N., Thiels, C. A., Pandian, T. K., Schiller, H. J., Murad, M. H., & Aho, J. M. (2016). Chest Wall Thickness and Decompression Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Comparing Anatomic Locations in Needle Thoracostomy. Injury, 47(4), 797–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2015.11.045

Mogali, S. R., Yeong, W. Y., Tan, H. K. J., Tan, G. J. S., Abrahams, P. H., Zary, N., … Ferenczi, M. A. (2018). Evaluation by medical students of the educational value of multi-material and multi-colored three-dimensional printed models of the upper limb for anatomical education. Anatomical Sciences Education, 11(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1703

*Sreenivasulu Reddy Mogali

11 Mandalay Road, Singapore 308232

Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine,

Nanyang Technological University

Email: sreenivasulu.reddy@ntu.edu.sg

Submitted: 17 April 2020

Accepted: 05 August 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 114-118

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/SC2358

Warren Fong1,3,4, Yu Heng Kwan2, Sungwon Yoon2, Jie Kie Phang1, Julian Thumboo1,2,4 & Swee Cheng Ng1

1Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 2Programme in Health Services and Systems Research, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 3Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 4Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to examine the perception of faculty on the relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the Professionalism Mini Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX) in the assessment of medical professionalism in residency programmes in an Asian postgraduate training centre.

Methods: Cross-sectional survey data was collected from faculty in 33 residency programmes. Items were deemed to be relevant to assessment of medical professionalism when at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8 on a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant). Feedback regarding the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX assessment was also collected from the faculty through open-ended questions.

Results: In total, 555 faculty from 33 residency programmes participated in the survey. Of the 21 items in the P-MEX, 17 items were deemed to be relevant. For the remaining four items ‘maintained appropriate appearance’, ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’, ‘solicited feedback’, and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’, the percentage of faculty who gave a rating of ≥8 was 78%, 75%, 74%, and 69% respectively. Of the 333 respondents to the open-ended question on feasibility, 34% (n=113) felt that there were too many questions in the P-MEX. Faculty also reported that assessments about ‘collegiality’ and ‘communication with empathy’ were missing in the current P-MEX.

Conclusion: The P-MEX is relevant and feasible for assessment of medical professionalism. There may be a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality and empathetic communication in the P-MEX.

Keywords: Professionalism, Singapore, Survey, Assessment

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical professionalism is one of the core Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies and forms the basis of medicine’s contract with society. Unprofessional behaviour during training of junior doctors has been shown to result in future unprofessional behaviour. Assessment of professionalism not only allows for timely feedback to residents to help them improve, but also allows for development of better curriculum to prevent lapses in medical professionalism. The Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX) had previously been identified as a potential observer-based assessment tool (Kwan et al., 2018), but it has not been validated in a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural Asian context such as Singapore. According to International Ottawa Conference Working Group on the Assessment of Professionalism, professionalism varies across cultural contexts, and therefore cross-cultural validation of the assessment tool for medical professionalism is imperative (Hodges et al., 2011). The current assessment tools adopted in local institutions may not cover the entire continuum of medical professionalism. For example, in the Ministry of Health Holdings (MOHH) C1 form which is currently being used for the assessment of residents on a 6-monthly basis, the assessment of professionalism is summative and consists of only three items (1) Accepts responsibility and follows through on tasks, (2) Responds to patient’s unique characteristics and needs equitably, (3) Demonstrates integrity and ethical behaviour.

We aimed to (1) examine faculty perception of the relevance of the P-MEX for assessment of medical professionalism in the local context, and (2) determine the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX as an assessment tool for medical professionalism in Singapore.

II. METHODS

A. Design and Participants

We invited faculty in the SingHealth residency programmes to participate in the study by completing an online anonymous questionnaire in July 2018 to August 2018. Participants were given one week to complete the survey, with three reminder emails sent at one-week, two-weeks and one-month after the deadline for submission. SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study (Reference Number: 2016/3009). Implied informed consent was provided by participants before completing the online anonymous questionnaire.

B. Survey Questionnaire

The P-MEX consists of four domains (Doctor-patient relationship skills, Reflective skills, Time management and Inter-professional relationship skills) and 21 sub-domains. Faculty were asked to rate the relevance of each item in P-MEX using a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant). The faculty were also asked the following open-ended questions to determine the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX- (1) “In your opinion, is a P-MEX form with 21 items too long, making it not feasible for routine use? If so, which items should be removed?” and (2) “In your opinion, are there any missing items (observable actions of a medical professional) that should be included in this form? If so, what new items should be added?” The questionnaire also included additional questions related to demographic characteristics (age, gender, specialty and number of years since becoming a specialist).

C. Analysis

Items were deemed to be relevant to the assessment of medical professionalism when at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8. This was determined by expert judgement and prior literature (Avouac et al., 2011). For the open-ended questions on feasibility and comprehensiveness, responses were categorised and the number of the respondents who deemed the 21-item P-MEX to be not feasible (too long) or not comprehensive (there were missing items that should be included) are presented.

III. RESULTS

In total, 555 faculty from 33 residency programmes participated in the survey (response rate 44%). The respondents were 59% male, median age 43 years old, age ranged from 30 to 78 years old. Specialists from medical and surgical disciplines made up 39% and 27% of the respondents respectively, with the remaining respondents coming from diagnostic radiology/nuclear medicine, anaesthesiology, paediatrics and emergency medicine (12%, 11%, 6% and 5% of the respondents respectively).

A. Relevance

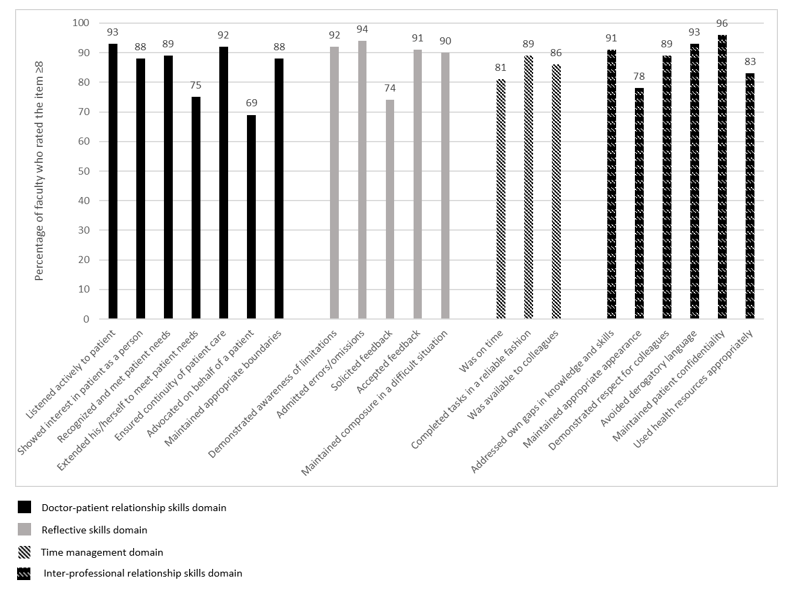

Of the 21 items in P-MEX, 17 items were deemed to be relevant (at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8). For the remaining four items ‘maintained appropriate appearance’, ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’, ‘solicited feedback’, and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’, the percentage of faculty who gave a rating of ≥8 was 78%, 75%, 74%, and 69% respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of faculty (n=555) who rated the item ≥8 on the relevance of the item in assessment of medical professionalism using a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant).

B. Feasibility

There were 333 respondents for the question “In your opinion, is a P-MEX form with 21 items too long, making it not feasible for routine use? If so, which items should be removed?”, of which 34% (n=113) felt that there were too many questions in the P-MEX assessment form. The top four items chosen to be removed were “solicited feedback” (n=36), “extended his/herself to meet patient needs” (n=27), “advocated on behalf of a patient” (n=25), and “maintained appropriate appearance” (n=23). 208 (62%) respondents felt that the number of questions in the P-MEX assessment form was appropriate.

C. Comprehensiveness

There were 307 respondents to the question “In your opinion, are there any missing items (observable actions of a medical professional) that should be included in this form? If so, what new items should be added?”, of which 28% (n=85) faculty felt that there were missing items. The most frequently mentioned missing items were regarding assessment of ‘collegiality’ (n=54) and assessment of ‘communication with empathy’ (n=12).

Examples of ‘collegiality’ provided by faculty— “Collaboration with other healthcare professionals in the patients’ best interest”, “Demonstration of collaborative behaviour”

Examples of ‘communication with empathy ‘provided by faculty— “Communicate with empathy and effectively to patient and family, taking into account their level of understanding, education and socioeconomic background”, “Communication skills…should embrace empathy, listening skills, discretion, sensitivity and intelligence… sufficient information, counselling, planning and advice regarding medical condition and options.”

207 respondents (67%) felt that the P-MEX was comprehensive for the assessment of medical professionalism.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study provides preliminary evidence on the relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX in the assessment of medical professionalism in an Asian city state. The current study is part of a larger project to culturally adapt and validate the P-MEX. Based on our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the faculty perception on relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX in the assessment of medical professionalism in a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic context.

There were four items that were deemed to be less relevant (extended his/herself to meet patient needs, advocated on behalf of a patient, solicited feedback, maintained appropriate appearance). These findings were also similar in a validation study performed in Canada, where the items ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’ and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’ were also frequently marked as ‘not applicable’, suggesting that the two items may be less relevant (Cruess, McIlroy, Cruess, Ginsburg, & Steinert, 2006). Qualitative methods can be used to explore the reasons why these items were deemed to be less relevant. About one-third of faculty felt that P-MEX was too long. Further study is warranted to evaluate the possibilities for shortening the P-MEX to reduce response burden and enhance routine use of the P-MEX.

In addition, our study revealed a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality. Some faculty felt that ‘collegiality’ was missing in the P-MEX despite the presence of items such as ‘demonstrated respect for colleagues’ and ‘avoided derogatory language’. This suggests that collegiality may encompass actions other than demonstrating respect and avoiding derogatory language in the local context, and further reinforces the emphasis of interprofessional collaborative practice.

Faculty also felt that there was also a lack of assessment of ‘communication with empathy’ in the P-MEX. The importance of empathetic communication is also supported by a study in Indonesia, a country in the same region, which found that patients considered communication as the most important attribute of medical professionalism (Sari, Prabandari, & Claramita, 2016).

This study has some limitations. The non-response rate raises concern about possible selection bias. Non-responders may have been less enthusiastic about the assessment of medical professionalism. Medical professionalism is affected by socio-cultural factors, therefore the findings from this study may not be entirely generalizable to another socio-cultural context. In addition, we were unable to elucidate the reasons for disagreement with the relevance of some of the items in the P-MEX as many faculty did not provide feedback and comments. Nevertheless, the findings of this study can serve as basis for future research, especially in countries with similar multicultural backgrounds.

V. CONCLUSION

Faculty agreed that most of the items in the P-MEX were relevant in the assessment of medical professionalism. Majority of the faculty also felt that the P-MEX was feasible to be used routinely in the assessment in medical professionalism. There may be a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality and communication with empathy in the modified P-MEX.

Notes on Contributors

Warren Fong reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Yu Heng Kwan reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Sungwon Yoon advised the design of study, analysed data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. Jie Kie Phang collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Julian Thumboo advised the design of study, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. Swee Cheng Ng advised the design of study, collected data, analysed data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this was granted by the SingHealth Institutional Review Board (Reference Number: 2016/3009).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank all the study participants for contributing to this work.

Funding

This research was supported by SingHealth Duke-NUS Medicine Academic Clinical Programme Education Support Programme Grant (Reference Number: 03/FY2017/P2/03-A47). Funder was not involved in the design, delivery or submission of the research.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Avouac, J., Fransen, J., Walker, U., Riccieri, V., Smith, V., Muller, C., … Matucci-Cerinic, M. (2011). Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: Results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 70(3), 476-481. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.136929

Cruess, R., McIlroy, J. H., Cruess, S., Ginsburg, S., & Steinert, Y. (2006). The professionalism mini-evaluation exercise: A preliminary investigation. Academic Medicine, 81(10), S74-S78.

Hodges, B. D., Ginsburg, S., Cruess, R., Cruess, S., Delport, R., Hafferty, F., . . . Ohbu, S. (2011). Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Medical Teacher, 33(5), 354-363.

Kwan, Y. H., Png, K., Phang, J. K., Leung, Y. Y., Goh, H., Seah, Y., . . . Lie, D. (2018). A systematic review of the quality and utility of observer-based instruments for assessing medical professionalism. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10(6), 629-638.

Sari, M. I., Prabandari, Y. S., & Claramita, M. (2016). Physicians’ professionalism at primary care facilities from patients’ perspective: The importance of doctors’ communication skills. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(1), 56-60. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.184624

*Warren Fong

SingHealth Rheumatology,

Senior Residency Programme,

20 College Road,

Singapore 169856

Tel: +6563214028

Email: warren.fong.w.s@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 16 April 2020

Accepted: 21 July 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 119-121

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/PV2250

Annushkha Sharanya Sinnathamby

Department of Paediatrics, Khoo Teck Puat National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

“To have striven, to have made the effort, to have been true to certain ideals – this alone is worth the struggle.”

William Osler

The word “values” is heard frequently in healthcare. From the moment we step into medical school, we are challenged to reflect what our intrinsic values are, or how we can “add value” to a department during the residency application.

With time, and in going through the system, our definitions of the word “values” may change. To me, values are those things which are right and wrong, and which are important in life. In other words, values include not only what is important to my profession and to being a good doctor, but also to what is important to being a good person.

The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre argues that one should reflect on the following three questions at the heart of moral thinking (Hinchman, 1989):

- Who am I?

- Who ought I to become?

- How ought I to get there?

In the context of understanding our values in healthcare, I wondered if the above can be translated into:

- What are my values?

- Which values should we value?

- How should we value those values?

In this article, I aim to touch on some of my view on values in the healthcare system, from the perspective of a junior doctor.

II. ARE OUR VALUES MISPLACED?

How often do we really ask ourselves what is important, what is good, or what is morally correct?

I asked a few junior doctors what values they think are important to being a good doctor. For some, the first response was classical, including “perseverance”, “compassion”, and “integrity”. However, the first thought of many others was not to be a kind or compassionate doctor, but an efficient or skilful one. I quote some of them verbatim:

“If my seniors don’t have to do anything, because I’ve done it all, then I’ve done my job.”

“No matter how much we value empathy and respect… I feel this doesn’t matter unless you have the competency to treat your patients.”

These doctors are far from unkind, dishonest, or cold. In fact, I know them personally to be some of the most good-hearted residents at work. Despite this, “typical” values such as kindness or integrity are not values which they instinctively identify with.

It is important to distinguish that being a “good” doctor may have more than one definition. “Good” as an adjective can mean being skilled and competent; on the other hand, it also means being morally upright, kind, and compassionate. Of course, it should be no argument that every doctor should be all of the above. Yet, I fear that we may be so increasingly fixated on the former, that we begin to lose sight of the latter.

As a case in point, I challenged some of our contemporaries to see how strongly they held on to an arguably core value—integrity. This value is often tested in a common daily scenario for our junior doctors: bargaining for a scan from our Radiology colleagues, where questionable tactics are sometimes employed to ensure a slot.

I asked every junior doctor working in the department two simple questions:

1) If they had ever lied to get a scan

2) If they had ever augmented the truth to get a scan

I had assumed that not a single doctor would have outright lied to get a scan, but 7.1% admitted to having done so. Furthermore, 67.9% said they would augment the truth to get a scan. This implies that there is a spectrum from an exaggeration to an outright falsehood.

When asked to elaborate on the above question, many retrospectively regretted embellishing the truth. A senior medical officer described in detail his experience lying for a particular peripherally inserted central catheter as a house officer. Even after 4 years, he could cite shame at lying to a radiologist who could almost certainly see through the lie, and perhaps depriving another patient who needed the scan more of a slot.

Ultimately, I think this boils down to our personal yardstick of our own integrity, and how willing each of us is to allow ends to justify means. Though the change of phrasing in the question I asked led to a big change in statistics, this does not change the fact that for some doctors, “augmenting the truth” strays dangerously far from what the truth really is.

Perhaps, it is then relevant to examine what would make a junior doctor re-order their priorities, and inadvertently compromise their own core values. In an increasingly busy environment, one reason we may lose sight of our core values is burnout. Studies in Singapore have described that between 55.1%-80.7% of residents reported burnout in some form, higher than their US counterparts (Lee, Loh, Sng, Tung, & Yeo, 2018; See et al., 2016). Furthermore, it was postulated that there was a negative correlation between burnout and empathy levels, and that overnight calls and low degrees of respect from colleagues were associated with increased stress levels. Burnout and emotional fatigue may cause us to erroneously weigh our values, and this could be why some junior doctors prioritise efficiency, meticulousness, or even keeping their seniors happy, to the extent of losing sight of their core values.

III. WHAT VALUES SHOULD WE VALUE?

It is no secret that a career in medicine is highly competitive. At every stage of training, medical student’s face a barrage of rigorous series of assessments that continue on into their professional careers. Therefore, it is important to examine the criteria we use to measure our doctors. Grading systems increasingly put emphasis on the softer side of medicine such as compassion and integrity, but more can be done to help our doctors value themselves and their own values more.

I recently filled up a typical grading form for my house officer. For 22 questions about his daily work, there was only one about his values and professionalism. It was a shame, as I strongly believe that an emphasis on our values should be a learning outcome, even if it is not a graded criterion. I was once taught that a patient may never remember your management, but will always remember your kindness—words that resonate with me even today.

On an institutional level, it is also important to have an emphasis on values. The institution I work in advocates the TRICEPS core values, a catchy acronym for Teamwork, Respect, Integrity, Compassion, Excellence, and Patient-Centeredness. While these values were probably established as a guideline to attract like-minded individuals to the institution, I also think these are a good set of values to emulate.

IV. HOW SHOULD WE VALUE OUR VALUES?

A system is only as great as its people. It is difficult to change a huge system, but it is easy to start the change from within ourselves, and those around us. It is also beneficial to ensure junior doctors are mindful of their values. In our daily practice, this means empowering them to self-reflect.