Insights for medical education: via a mathematical modelling of gamification

Submitted: 28 March 2020

Accepted: 23 September 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 9-24

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/OA2242

De Zhang Lee1, Jia Yi Choo1, Li Shia Ng2, Chandrika Muthukrishnan1 & Eng Tat Ang1

1Department of Anatomy, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Otolaryngology, National University Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Gamification has been shown to improve academic gains, but the mechanism remains elusive. We aim to understand how psychological constructs interact, and influence medical education using mathematical modelling.

Methods: Studying a group of medical students (n=100; average age: 20) over a period of 4 years with the Personal Responsibility Orientation to Self-Direction in Learning Scale (PRO-SDLS) survey. Statistical tests (Paired t-test) and models (logistic regression) were used to decipher the changes within these psychometric constructs (Motivation, Control, Self-efficacy & Initiative), with gamification as a tool. Students were encouraged to partake in a maze (10 stations) that challenged them to answer anatomical questions using potted human specimens.

Results: We found that the combinatorial effects of the maze and Script Concordance Test (SCT) resulted in a significant improvement for “Self-Efficacy” and “Initiative” (p<0.05). However, the “Motivation” construct was not improved significantly with the maze alone (p<0.05). Interestingly, the “Control” construct was eroded in students not exposed to gamification (p<0.05). All these findings were supported by key qualitative comments such as “helpful”, “fun” and “knowledge gap” by the participants (self-awareness of their thought processes). Students found gamification reinvigorating and useful in their learning of clinical anatomy.

Conclusion: Gamification could influence some psychometric constructs for medical education, and by extension, the metacognition of the students. This was supported by the improvements shown in the SCT results. It is therefore proposed that gamification be further promoted in medical education. In fact, its usage should be more universal in education.

Keywords: Psychometric Constructs, Medical Education, Motivation, Initiative, Self-efficacy

Practice Highlights

- Student’s enjoyment (interest) of the curriculum will determine the eventual academic outcome.

- Metacognition (defined as the “learning of learning”, “knowing of knowing” and/ or the awareness of one’s thought processes) was improved with SCT and gamification.

- Gamification is useful as a form of augmentation for didactic teaching but should never replace it.

- Different type of psychometric scale (e.g. LASSI versus PRO-SDLS) used in your research will produce varying results.

- Gamification is resource intensive and needs extra time to prepare compared to didactic approaches.

I. INTRODUCTION

Psychology is integral to healthcare and education but has often been overshadowed, compared to the other basic disciplines (Choudhry et al., 2019; Pickren, 2007). This is ironical because human psyche needs to be properly understood in order to manage them effectively (Wisniewski & Tishelman, 2019). Presently, the study of psychology does not feature prominently in the medical curriculum (Gallagher et al., 2015) with the exception of psychiatry (Douw et al., 2019). This gap needs to be addressed (Paros & Tilburt, 2018). In this research, we seek to understand the constructs for good medical learning via gamification which has wide ranging effects (Mullikin et al., 2019). The psychometric constructs to be analysed were as follows: 1) “Motivation”; define as the desire to learn out of interest or enjoyment (Yue et al., 2019). 2) “Initiative”; refers to how proactive a student is to learning (Boyatzis et al., 2000). 3) “Control”; is how much influence one has over the circumstances (Sheikhnezhad Fard & Trappenberg, 2019). 4) “Self-Efficacy”; relates to how confident one is, to do what needs to be done (Michael et al., 2019). We believe that these constructs contribute to the student’s awareness of their own thought processes (metacognition) towards their medical education.

Gamification” is defined as a process of adding game-like elements to something so as to encourage more participation (Rutledge et al., 2018; Van Nuland et al., 2015). The idea of using games to “lighten up” medical education in the clinical setting was first proposed in 2002 (Howarth-Hockey & Stride, 2002). The authors observed increased engagement and participation during lunchtime medical quizzes in the hospital. They therefore concluded that medical education could be fun, and since then, gamification has been taken seriously by the community (Evans et al., 2015; Nevin et al., 2014). In essence, gamification could be something as simple as having board games (Ang et al., 2018) but importantly, its impact on students’ learning must be evaluated and validated. Most studies in the literature did not fulfil this requirement (Graafland et al., 2012). The impact of games on the behavioral and/or psychological outcomes should be studied (Graafland et al., 2017; Graafland et al., 2014).

A PubMed search would reveal that there are numerous self-reporting tools such as LASSI (Learning and Strategies Study Inventory (Muis et al., 2007), MSLQ (Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Villavicencio & Bernardo, 2013), and the SRLPS (Self-regulated Learning Perception Scale) (Turan et al., 2009) etc. Given the choices, how does one decide which one to adopt for their studies? In our research, we chose to use the PRO-SDLS survey questions with some modifications. The choice was both serendipitous and practical, as we have previously validated it via the Cronbach alpha (>0.7). In our earlier work, feedback scores and results yielded inconclusive evidence to support enhanced motivation among our students. Furthermore, was this due to gamification? With the current endeavour, we aim to prove via mathematical modelling that there are indeed alterations to the psychometric constructs. Hence, we re-analyse the old data set together with additional new information, using statistical analysis tools such as the logistic regression model, Wilcoxon tests, and the Paired t-test.

Medical teaching and learning is a complex endeavour based on an apprenticeship model (Cortez et al., 2019), which may or may not be an ideal arrangement (Sheehan et al., 2010). Furthermore, the decision making is often delegated to the seniors (Chessare, 1998). Conversely, gamification could empower the students to take charge of one’s learning, including decision making (Shah et al., 2013). Furthermore, one needs to understand what works from what is empirical (Cote et al., 2017). While our initial research addressed the impact of the games on academic performance, we now sought to further understand its effects on the psychometric dimensions. This will help to understand the psychology of self-directed (or regulated) learning. We hypothesize that the amount of gamification will impact these constructs. In summary, we hope to achieve the following:

Aims:

- Understanding the role of psychometric constructs and gamification in medical education via suitable mathematical modelling.

- To decipher the interaction of different psychometric constructs (Motivation, Self-efficacy, Control and Initiatives) in producing desired learners’ behaviours (metacognition) via the anatomy maze.

II. METHODS

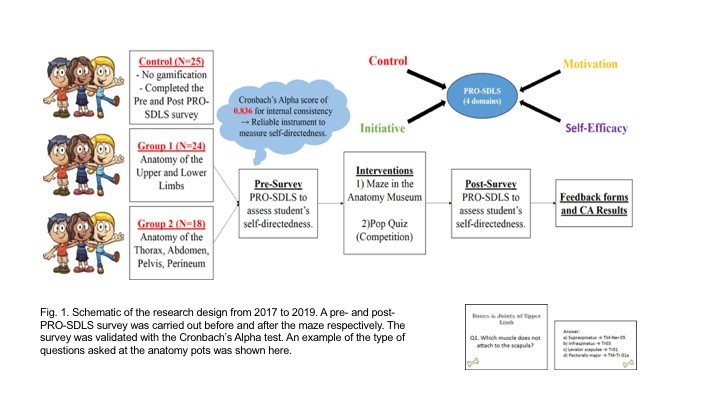

First-year medical students (M1) took part in this retrospective analytical research. Two randomised groups of medical students (n=75, median age: 20 years) consented to the study (Group 1 & 2). A randomised group of students (n=25) exposed to no gamifications (Group 0) served as the control. Every student was required to complete a pre- and post- PRO-SDLS for the research. There were no penalties for withdrawing from the IRB-approved project (See IRB: B-16-205).

Gamification was carried out according to the scheme in Figure 1. Each group was divided into 3 to 4 subgroups that would enter the maze with a clue card (see example in Figure 1) linked to a specific pot specimen. They were required to explore the museum for the next clue and had to answer the hidden questions (see examples in Appendix) which would provide further directions. At the conclusion, students were given a competitive pop quiz that had no impact on their summative academic grades.

The main purpose was to assess formative knowledge acquisition. The validated PRO-SDLS include the following psychometric constructs: “Motivation” (7 questions), “Initiative” (6 questions), “Control” (6 questions) and “Self-Efficacy” (6 questions). (See Sup. Materials). The responses are then collapsed into an average accordingly. A higher score indicated more agreeability towards that construct for self-directed learning (Ang et al., 2017). The survey was designed with backward scoring to ensure accuracy. For quantification purposes, we subtracted the pre-feedback from the post-feedback scores for each question. An increased score for a particular construct suggests improvement (Cazan & Schiopca, 2014). Furthermore, students in Group 2 were given Script Concordance Test (SCT) quizzes (See Sup. Materials) as part of gamification (Lubarsky et al., 2013; Lubarsky et al., 2018; Wan et al., 2018). SCT were meant to enhance clinical reasoning. All data were analysed from two perspectives:

- The magnitude of score increase (or decrease) of the post- PRO-SDLS survey responses, with respect to the pre- responses.

- The odds of a student reporting an increased score in the post- PRO-SDLS survey responses.

In (a), the paired differences for each student’s response were studied using a parametric approach (paired t-test). In (b), we studied the odds of increased score for each construct, and investigate if grouping affected these odds. More formally, for each construct k (where k is one of the four constructs), we define variable as the probability of a student from group showing an increase in score for construct (and hence, as the probability that the student’s score decreased or remained unchanged). The value of can be estimated by dividing the number of students from group with an increased score for construct by the total number of students from group . If the interventions are unsuccessful, we would expect to be around since a student’s score would likely either increase or decrease at random, with an equal probability. This can be tested using the t-test.

An alternative approach would be to study the odds of success, which can be written as . A common mathematical model used to study these odds is the logistic regression model. For each construct, the logistic regression model studies the odds of a student from a given group showing an increased or decreased score. The overall significance of the model can be tested using the p-value obtained from the likelihood ratio test, while the significance of the individual odds can be tested using the t-test. For more details on the logistic regression model, we refer the reader to (Agresti, 2003).

We utilised the open source software R (Team, 2019) to perform our statistical analysis.

III. RESULTS

Participation rate in the gamification endeavour was consistently 90±5%, and there was zero withdrawal from it, accompanied by reported favourable qualitative comments.

A. Studying the Absolute Scores

The average change in scores across all the groups for each construct is given in Table 1. From these scores, we believe that our gamification exercises may have had a positive impact on “Self-Efficacy” and “Initiative”. To visualize the spread of responses, we have prepared box plots of the post – pre scores (available in Supplementary Materials).

|

Groups |

Constructs |

|||

|

Self-Efficacy |

Initiative |

Motivation |

Control |

|

|

0 |

0.07 |

-0.05 |

0.11 |

0.03 |

|

1 |

0.13 |

0.26 |

0.05 |

0.01 |

|

2 |

0.13 |

0.20 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

Table 1: Average post-pre scores

To determine if the construct scores pre and post intervention were different, we used the paired t-test, under the null hypothesis that there is no change. The p-values obtained are summarized in Table 2.

|

Groups |

Constructs |

|||

|

Self-Efficacy |

Initiative |

Motivation |

Control |

|

|

0 |

0.46 |

0.57 |

0.43 |

0.79 |

|

1 |

0.07 |

0.00 |

0.54 |

0.86 |

|

2 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.09 |

0.14 |

Table 2: p-values of t-test (to 2 decimal places)

We observe that the null hypothesis of no difference between pre and post intervention levels for all constructs are not rejected (under p=0.05) for the control group. Both tests also failed to show any significant change for the “Control” construct.

There is strong evidence that the classroom interventions employed by Groups 1 and 2 had an impact on “Initiative” levels of students, reflected by the small p-values obtained using both tests. The average increase in “Initiative” scores for students in Groups 1 and 2 are 0.71 and 0.67, respectively, which are similar. Recall that the students in Group 2 participated in the SCT, in addition to the maze which is common across both groups. This suggests that the SCT has a negligible impact on “Initiative”.

There is also strong evidence (p=0.05) to show that the games enhanced the “Self-Efficacy” levels among the students. The t-test also gives strong evidence (p=0.05) that there is a significant change in Group 2, and milder evidence for Group 1 (p=0.10). The average increase in “Self-Efficacy” levels for Groups 1 and 2 are 0.63 and 0.56, respectively. Again, the differences are negligible, and this suggests that the SCT has a negligible impact. Finally, there is mild evidence (p=0.10) of a significant change in “Motivation” for Group 2, but no such evidence for Group 1. The average increase in “Motivation” score for Group 2 is 0.55. This time, the SCT might have helped to improve students’ motivation.

B. Studying the Odds of Score Improvement

We will now turn our attention to modelling the odds of a student reporting an increase in construct score. Earlier, we defined as the probability of a student from group showing an increase in score for construct , and explained why we would expect to be around if the games have no impact on the odds of “success”. The t-test was used to test this, under the null hypothesis that for all groups and constructs. The p-values obtained are summarised in Table 3.

|

Groups |

Constructs |

|||

|

Self-Efficacy |

Initiative |

Motivation |

Control |

|

|

0 |

0.56 |

0.56 |

0.85 |

0.07 |

|

1 |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.78 |

0.25 |

|

2 |

0.57 |

0.08 |

0.57 |

0.85 |

Table 3: p-values of t-test (to 2 decimal places)

We first notice that the p-values reported using both tests are almost identical. Interestingly, there is mild evidence (p=0.10) that the value of “Control” construct for Group 0 deviates significantly from 0.5, and it is estimated to be 0.32. This means that the students in the control group reported a drop in “Control” levels.

There is also mild evidence (p=0.10) that the probability of a student reporting an increase in “Self-Efficacy” for Group 1 deviates significantly from 0.5. This probability is estimated to be 0.63, which indicates that the odds of a student from Group 1 reporting an increase in “Self-Efficacy” levels is higher compared to the others.

Finally, there is evidence that the probability of reporting an increase in “Initiative” levels for students from Groups 1 and 2 deviates significantly from 0.5. The probabilities for Group 1 and Group 2 are 0.71 and 0.67, respectively.

Next, we will model our data using the logistic regression model. We will fit four models, one for each construct. For each model, we calculate the odds of a student from a given group showing an increased or decreased score. An odds of greater than 1 means that the student is more likely to show an increased score, while an odds of less than 1 means the opposite. An odds of exactly 1 means that the student is neither more nor less likely to show a changed score. The statistical significance of the individual odds and the overall model fit for each construct was computed using the t-test, and likelihood ratio test, respectively. The results are summarised in Table 4, with the statistically significant (p=0.10) odds highlighted in blue, together with their respective p-values.

|

Odds |

Constructs |

|||

|

Self-Efficacy |

Initiative |

Motivation |

Control |

|

|

Group 0 |

0.92 |

0.79 |

1.27 |

0.47 (0.08) |

|

Group 1 |

1.08 |

2.41 (0.02) |

1.67 |

0.72 |

|

Group 2 |

1.25 |

1.99 (0.10) |

1.26 |

0.93 |

|

|

Constructs |

|||

|

Self-Efficacy |

Initiative |

Motivation |

Control |

|

|

p-value |

0.93 |

0.01 |

0.22 |

0.29 |

Table 4: (top) Coefficients for each construct (significant odds in blue, p-values in brackets) (bottom) p-values to assess logistic regression model fit using likelihood ratio test

Under the logistic regression model, not rejecting the null hypothesis for a given odds means that we assume it takes on the value 1. It should be noted that the individual coefficients should be examined when the model is determined to be significant under the likelihood ratio test, as the coefficients obtained under a poor model fit may not be meaningful.

We notice that the significant terms flagged out by the t-test (Table 3) largely agree with the significant terms of the logistic regression model, except for the “Self-Efficacy” odds for Group 1. However, the “Self-Efficacy” model was not determined to be a good fit using the likelihood ratio test.

The only model which was deemed to be a good fit was the one for the “Initiative” construct. The odds for Group 0 is deemed to be insignificant (and hence assumed to be 1), while the odds for Groups 1 and 2 are statistically significant. We can interpret this model as follows,

- Since the odds for Group 0 is statistically insignificant under the t-test, we assume the odds to be 1. In other words, it is equally likely for a student from the control group to show an increase or decrease in score.

- The odds for both Group 1 and 2 are statistically significant. The odds of success of Group 1 is 2.41, which can be translated to a roughly 7 in 10 chance (probability of 0.71) for a student in this group showing an improved score. A similar interpretation can be made for Group 2, which showed an odds of 1.99. This translates to a slightly lower probability of 0.67 for a student from Group 2 displaying an improved score.

With this, we have presented a logistic regression approach of mathematically modelling these odds. A search on Google Scholar and PubMed yielded no previous work which made us of this mathematical modelling approach on the PRO-SDLS survey data. With the derived odds, we can compare the degree of success of the various classroom interventions. The logistic regression modelling approach is therefore, proposed as a complement of the t-test approach, which is restricted to detecting the presence of statistically significant differences.

C. Qualitative Comments (underlined words underpinning for metacognition)

1) Positive feedbacks:

- “The maze games were the most helpful as they helped me to consolidate my learning, and also enables me to ask the tutor any questions that I have from class. They allowed me to learn anatomy in a fun, enjoyable and memorable way”

- “It allowed me to visualize the things that I was learning and helped with clarifying doubts”

- “The extra question posted at each station was helpful”

- “Wanting to be able to identify things in the museum makes me more motivated to prepare beforehand”

- “Allows me to identify the knowledge gap so that I can work on it”

- “I like the quiz as it motivates me to study beforehand and shows me the gaps in my knowledge”

- “The clinically relevant questions made me think a lot”

2) Negative feedbacks:

- “I prefer didactic teaching”

- “We did not interact much with the exhibits”

- “The maze was more of a mini quiz or test to check if we remember anything”

- “Perhaps we could go into more complex concepts”

- “More challenging questions”

- “Students just follow each other around the anatomy museum and it defeats the purpose of the maze”

- “The maze could have a competitive element to make it more exciting. Maybe more MCQ questions per model so we can make use of it more”

IV. DISCUSSION

We undertook this research to decipher how gamification as a concept helps medical students learn a basic subject like human anatomy. We also want to understand how psychometric constructs interact to produce behavioural changes towards self-directed learning. This was done by analysing the data from the PRO-SDLS via statistical tests. Put simply, one needs to understand that medical education is a very complex process that demands balance between apprenticeship (fellowship) (Sheehan et al., 2010), and a dose of self-directed learning (van Houten-Schat et al., 2018). With our initial research into gamification of anatomy education (Ang et al., 2018), there were other studies suggesting similar benefits (Felszeghy et al., 2019; Nicola et al., 2017; Van Nuland et al., 2015). We are therefore convinced that gamification could help to engage students and improve academic gains. However, the notion of gaming can be very broad (Virtual Reality, board games, digital apps etc.), so there is a need to understand the underlying psychology. With that in mind, we re-analyse our previous data with the existing, using proven statistical tools to decipher the learning psychology of these medical students, and their awareness of their own thought processes (metacognition).

We earlier hypothesised that gamification would influence these dependent constructs differently and indeed this was the outcome. In our analysis, we found that the combinatorial effects of the maze and SCT resulted in a significant improvement for “Self-Efficacy” and “Initiative”. While the maze alone did not significantly improve “Motivation”, we saw mild evidence of an improvement in terms of psychometric scores, when the SCT and maze were used in combination. In lay terms, the maze encouraged these students to learn on their own. By extension, one could also argue that gamification will help the students in making decisions since “Motivation” and “Initiatives” are key attributes (Vohs et al., 2008). The ability to make a simple clinical judgement, and the courage to act on them, are the virtues that we should be imbuing in the medical students, and some junior doctors. Interestingly, there is mild evidence that the “Control” construct was undergoing erosion in the students not exposed to gamification, as the course progresses. This adverse result is not seen in both groups exposed to the games. Perhaps the more relaxed classroom setting with gamification helped students to feel more in control of their learning process. Logically, this made a lot of sense across the education landscape.

A follow up question would be, does the feedback confirm the results given in our qualitative analysis? Recall that in our logistic regression model, students from both non-control groups displayed a statistically significant improvement in “Initiative” levels. This is supported by some of the positive feedback received for our endeavours, such as being “motivated to prepare beforehand”, “identify the knowledge gap” and work on them, as well as helping them to “think a lot” about the course content. Furthermore, some of the negative feedback, such as requests for more challenging questions, or more questions in general, suggests that the students are taking the initiative to learn more. This certainly adds credence to the findings of our proposed logistic regression model, as well as highlighting the importance of studying both qualitative and quantitative feedback.

There are caveats that one should be aware when implementing gamification. The formative part of the endeavour could be variable, and dependent on numerous factors such as the tutor involved, and the type of games, interventions, and reporting scales used. In the feedback, 76% of the participants felt that the maze should continue as an adjunct but not to totally replace didactic tutorials. In other words, introducing gaming elements into the curriculum should be done judiciously. With reverse scoring, it was shown that “Self-Efficacy” fell as the level of gamification is increased. In lay terms, students might be feeling that the maze trivialize the learning of the subject. As a counter measure, and to maintain quality assurance, we could introduce video lectures from previous years to allay these fears. In summary, we now confirmed that gamification works, and it influences learning outcomes as demonstrated by others (Burgess et al., 2018; Goyal et al., 2017; Kollei et al., 2017; Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij et al., 2017; Kurtzman et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2017; Savulich et al., 2017). Separately, there were criticisms as to why SCT was introduced into the research. We believed that such augmentation will add “fun” for the pre-clinical students to tackle the various clinical scenarios and clinical anatomy.

V. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Our research necessitated that the students take part in the maze and the SCT. Although it was not compulsory, no students opted out of it. Some critics would misconstrue this to be a form of forced play. According to Jane McGonigal, gamification should ideally not be mandated (Roepke et al., 2015).

VI. CONCLUSION

Through statistical modelling, we have shown how the “Initiative”, “Motivation”, and “Self-Efficacy” constructs could potentially benefit from gamification. The before-after experimental set up allowed for powerful comparisons to be made. Studying the odds of construct score improvement, alongside the raw scores, allowed us to study the data from different perspectives. Though this approach, we discovered how the potential benefits of our gamification exercises outweigh the potential adverse effects. Gamification had resulted in improved “Initiative” in these medical students. We believe that their decision-making skills will also be boosted if existing culture allows for more self-discovery (to improve “Initiative”, “Control” and “Self-efficacy”) and autonomy. If these recommendations are duly considered and implemented thoughtfully, there is little doubt that our future doctors will be better equipped to serve humanity. This may also help to avoid possible burnout in residents (Hale et al., 2019).

Stronger conclusion and potential for applications are as follows: In a continuum, we started gamifying anatomy education and proven that academic grades could be improved by the process (Ang et al., 2018). We then asked a fundamental question in how exactly it happened. This was done by carrying out a psychometric analysis on the participants. We discovered that psychometric constructs were important, and this was proven in this manuscript. The impact of gamification is now elevated given the COVID-19 pandemic that necessitated more online teaching. Moving forward, we believe that gamification should move towards creating an electronic application that the students may access 24/7. This will ensure that medical teaching will be fortified and be somewhat protected from further disruptions.

Notes on Contributors

Lee De Zhang graduated with a degree in Statistics and Computer Science. He reviewed the literature, analysed the data and wrote part of the manuscript.

Eng Tat Ang, Ph.D., is a senior lecturer in anatomy at the Department of Anatomy at the YLLSoM, NUS. He reviewed the literature, designed the research, collected and analysed the data. He developed the manuscript.

Choo Jiayi, BSc (Hons) graduated with a degree in life sciences. She executed the research, and help collected the data. She contributed to the development of the manuscript.

M Chandrika, MBBS, DO, MSc is an instructor at the Department of Anatomy at the YLLSoM, NUS. She helped to execute the research and collected the data.

Ng Li Shia, MBBS, Master of Medicine (Otorhinolaryngology), MRCS(Glasg) is a consultant at the Department of Otolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery (ENT), National University Hospital. She developed the SCT questions.

Ethical Approval

This project has received full IRB and Ethical clearance (NUS IRB: B-16-205).

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to all students who took part in the research, and to the CDTL, NUS, for providing a teaching enhancement funds to support this research. Appreciation also due to Dr Patricia Chen (Dept. of Psychology, NUS) for her helpful advice.

Funding

NUS TEG AY2017/2018 was awarded to help the investigators pay Mr De Zhang Lee for the statistical modelling that gamification drove medical education via a MAZE.

Declaration of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Agresti, A. (2003). Categorical data analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Ang, E. T., Abu Talib, S. N., Samarasekera, D., Thong, M., & Charn, T. C. (2017). Using video in medical education: What it takes to succeed. The Asia Pacific Scholar. 2(3), 15-21.

Ang, E. T., Chan, J. M., Gopal, V., & Li Shia, N. (2018). Gamifying anatomy education. Clinical Anatomy, 31(7), 997-1005. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23249

Boyatzis, R. E., Murphy, A. J., & Wheeler, J. V. (2000). Philosophy as a missing link between values and behaviour. Psychological Reports, 86(1), 47-64. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2000.86.1.47

Burgess, J., Watt, K., Kimble, R. M., & Cameron, C. M. (2018). Combining Technology and Research to Prevent Scald Injuries (the Cool Runnings Intervention): Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(10), e10361. http://doi.org/10.2196/10361

Cazan, A. M., & Schiopca, B. A. (2014). Self-directed learning, personality traits and academic achievement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences (127), 640-644.

Chessare, J. B. (1998). Teaching clinical decision-making to pediatric residents in an era of managed care. Pediatrics, 101(4 Pt 2), 762-766; discussion 766-767. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9544180

Choudhry, F. R., Ming, L. C., Munawar, K., Zaidi, S. T. R., Patel, R. P., Khan, T. M., & Elmer, S. (2019). Health literacy studies conducted in australia: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071112

Cortez, A. R., Winer, L. K., Kassam, A. F., Hanseman, D. J., Kuethe, J. W., Quillin, R. C., 3rd, & Potts, J. R., 3rd. (2019). See none, do some, teach none: An analysis of the contemporary operative experience as nonprimary surgeon. Journal of Surgical Education, 76(6), e92-e101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.05.007

Cote, L., Rocque, R., & Audetat, M. C. (2017). Content and conceptual frameworks of psychology and social work preceptor feedback related to the educational requests of family medicine residents. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(6), 1194-1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.01.012

Douw, L., van Dellen, E., Gouw, A. A., Griffa, A., de Haan, W., van den Heuvel, M., Hillebrand, A., Van Mieghem, P., Nissen, I. A., Otte, W. M., & Reijmer, Y. D. (2019). The road ahead in clinical network neuroscience. Network Neuroscience, 3(4), 969-993. https://doi.org/10.1162/netn_a_00103

Evans, K. H., Daines, W., Tsui, J., Strehlow, M., Maggio, P., & Shieh, L. (2015). Septris: a novel, mobile, online, simulation game that improves sepsis recognition and management. Academic Medicine, 90(2), 180-184. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000611

Felszeghy, S., Pasonen-Seppänen, S., Koskela, A., Nieminen, P., Härkönen, K., Paldanius, K. M., Gabbouj, S., Ketola, K., Hiltunen, M., Lundin, M., & Haapaniemi, T. (2019). Using online game-based platforms to improve student performance and engagement in histology teaching. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 273. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1701-0

Gallagher, S., Wallace, S., Nathan, Y., & McGrath, D. (2015). ‘Soft and fluffy’: medical students’ attitudes towards psychology in medical education. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 91-101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313499780

Goyal, S., Nunn, C. A., Rotondi, M., Couperthwaite, A. B., Reiser, S., Simone, A., Katzman, D. K., Cafazzo, J. A., & Palmert, M. R. (2017). A mobile app for the self-management of Type 1 Diabetes among adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research mHealth and uHealth, 5(6), e82. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.7336

Graafland, M., Bemelman, W. A., & Schijven, M. P. (2017). Game-based training improves the surgeon’s situational awareness in the operation room: a randomized controlled trial. Surgical Endoscopy, 31(10), 4093-4101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5456-6

Graafland, M., Schraagen, J. M., & Schijven, M. P. (2012). Systematic review of serious games for medical education and surgical skills training. British Journal of Surgery, 99(10), 1322-1330. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8819

Graafland, M., Vollebergh, M. F., Lagarde, S. M., van Haperen, M., Bemelman, W. A., & Schijven, M. P. (2014). A serious game can be a valid method to train clinical decision-making in surgery. World Journal of Surgery, 38(12), 3056-3062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2743-4

Hale, A. J., Ricotta, D. N., Freed, J., Smith, C. C., & Huang, G. C. (2019). Adapting Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a Framework for Resident Wellness. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 31(1), 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1456928

Howarth-Hockey, G., & Stride, P. (2002). Can medical education be fun as well as educational? British Medical Journal, 325(7378), 1453-1454. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1453

Kollei, I., Lukas, C. A., Loeber, S., & Berking, M. (2017). An app-based blended intervention to reduce body dissatisfaction: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(11), 1104-1108. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000246

Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij, T. A., Robroek, S. J., Ling, S. W., van Rosmalen, J., van Rossum, E. F., Burdorf, A., & Hunink, M. G. (2017). A blended web-based gaming intervention on changes in physical activity for overweight and obese employees: Influence and usage in an experimental pilot study. Journal of Medical Internet Research Serious Games, 5(2), e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/games.6421

Kurtzman, G. W., Day, S. C., Small, D. S., Lynch, M., Zhu, J., Wang, W., Rareshide, C. A., & Patel, M. S. (2018). Social incentives and gamification to promote weight loss: The lose it randomized, controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(10), 1669-1675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4552-1

Lubarsky, S., Dory, V., Duggan, P., Gagnon, R., & Charlin, B. (2013). Script concordance testing: from theory to practice: AMEE guide no. 75. Medical Teacher, 35(3), 184-193. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.760036

Lubarsky, S., Dory, V., Meterissian, S., Lambert, C., & Gagnon, R. (2018). Examining the effects of gaming and guessing on script concordance test scores. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7(3), 174-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0435-8

Michael, K., Dror, M. G., & Karnieli-Miller, O. (2019). Students’ patient-centered-care attitudes: The contribution of self-efficacy, communication, and empathy. Patient Education and Counseling. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.004

Muis, K. R., Winne, P. H., & Jamieson-Noel, D. (2007). Using a multitrait-multimethod analysis to examine conceptual similarities of three self-regulated learning inventories. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(Pt 1), 177-195. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X90876

Mullikin, T. C., Shahi, V., Grbic, D., Pawlina, W., & Hafferty, F. W. (2019). First year medical student peer nominations of professionalism: A methodological detective story about making sense of non-sense. Anatomical Sciences Education, 12(1), 20-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1782

Nevin, C. R., Westfall, A. O., Rodriguez, J. M., Dempsey, D. M., Cherrington, A., Roy, B., Patel, M., & Willig, J. H. (2014). Gamification as a tool for enhancing graduate medical education. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1070), 685-693. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-132486

Nicola, S., Virag, I., & Stoicu-Tivadar, L. (2017). vr medical gamification for training and education. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 236, 97-103. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28508784

O’Connor, D., Brennan, L., & Caulfield, B. (2018). The use of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) for managing the complications of ageing related to reduced exercise participation. Maturitas, 113, 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.009

Paros, S., & Tilburt, J. (2018). Navigating conflict and difference in medical education: insights from moral psychology. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 273. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1383-z

Patel, M. S., Benjamin, E. J., Volpp, K. G., Fox, C. S., Small, D. S., Massaro, J. M., Lee, J. J., Hilbert, V., Valentino, M., Taylor, D. H., & Manders, E. S. (2017). effect of a game-based intervention designed to enhance social incentives to increase physical activity among families: The BE FIT randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 177(11), 1586-1593. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3458

Pickren, W. (2007). Psychology and medical education: A historical perspective from the United States. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(3), 179-181. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.37318

Roepke, A. M., Jaffee, S. R., Riffle, O. M., McGonigal, J., Broome, R., & Maxwell, B. (2015). Randomized controlled trial of superbetter, a smartphone-based/internet-based self-help tool to reduce depressive symptoms. Games for Health Journal, 4(3), 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2014.0046

Rutledge, C., Walsh, C. M., Swinger, N., Auerbach, M., Castro, D., Dewan, M., Khattab, M., Rake, A., Harwayne-Gidansky, I., Raymond, T. T., & Maa, T. (2018). Gamification in action: Theoretical and practical considerations for medical educators. Academic Medicine, 93(7), 1014-1020. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002183

Savulich, G., Piercy, T., Fox, C., Suckling, J., Rowe, J. B., O’Brien, J. T., & Sahakian, B. J. (2017). Cognitive training using a novel memory game on an ipad in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI). International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 20(8), 624-633. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx040

Shah, A., Carter, T., Kuwani, T., & Sharpe, R. (2013). Simulation to develop tomorrow’s medical registrar. The Clinical Teacher, 10(1), 42-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00598.x

Sheehan, D., Bagg, W., de Beer, W., Child, S., Hazell, W., Rudland, J., & Wilkinson, T. J. (2010). The good apprentice in medical education. New Zealand Medical Journal, 123(1308), 89-96. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20201158

Sheikhnezhad Fard, F., & Trappenberg, T. P. (2019). A novel model for arbitration between planning and habitual control systems. Frontiers in Neurorobotics, 13, 52. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbot.2019.00052

Team, R. C. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Turan, S., Demirel, O., & Sayek, I. (2009). Metacognitive awareness and self-regulated learning skills of medical students in different medical curricula. Medical Teacher, 31(10), e477-483. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903193521

van Houten-Schat, M. A., Berkhout, J. J., van Dijk, N., Endedijk, M. D., Jaarsma, A. D. C., & Diemers, A. D. (2018). Self-regulated learning in the clinical context: A systematic review. Medical Education, 52(10), 1008-1015. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13615

Van Nuland, S. E., Roach, V. A., Wilson, T. D., & Belliveau, D. J. (2015). Head to head: The role of academic competition in undergraduate anatomical education. Anatomical Sciences Education, 8(5), 404-412. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1498

Villavicencio, F. T., & Bernardo, A. B. (2013). Positive academic emotions moderate the relationship between self-regulation and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(Pt 2), 329-340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02064.x

Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B. J., Twenge, J. M., Nelson, N. M., & Tice, D. M. (2008). Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: A limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(5), 883-898. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.883

Wan, M. S., Tor, E., & Hudson, J. N. (2018). Improving the validity of script concordance testing by optimising and balancing items. Medical Education, 52(3), 336-346. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13495

Wisniewski, A. B., & Tishelman, A. C. (2019). Psychological perspectives to early surgery in the management of disorders/differences of sex development. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 31(4), 570-574. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000784

Yue, P., Zhu, Z., Wang, Y., Xu, Y., Li, J., Lamb, K. V., Xu, Y., & Wu, Y. (2019). Determining the motivations of family members to undertake cardiopulmonary resuscitation training through grounded theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(4), 834-849. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13923

*Ang Eng Tat

Department of Anatomy

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

MD10, National University of Singapore

Singapore 117599

Email address: antaet@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 4 August 2020

Accepted: 14 October 2020

Published online: 4 May, TAPS 2021, 6(2), 1-8

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/RA2370

Tow Keang Lim

Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Clinical diagnosis is a pivotal and highly valued skill in medical practice. Most current interventions for teaching and improving diagnostic reasoning are based on the dual process model of cognition. Recent studies which have applied the popular dual process model to improve diagnostic performance by “Cognitive De-biasing” in clinicians have yielded disappointing results. Thus, it may be appropriate to also consider alternative models of cognitive processing in the teaching and practice of clinical reasoning.

Methods: This is critical-narrative review of the predictive brain model.

Results: The theory of predictive brains is a general, unified and integrated model of cognitive processing based on recent advances in the neurosciences. The predictive brain is characterised as an adaptive, generative, energy-frugal, context-sensitive action-orientated, probabilistic, predictive engine. It responds only to predictive errors and learns by iterative predictive error management, processing and hierarchical neural coding.

Conclusion: The default cognitive mode of predictive processing may account for the failure of de-biasing since it is not thermodynamically frugal and thus, may not be sustainable in routine practice. Exploiting predictive brains by employing language to optimise metacognition may be a way forward.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Bias, Dual Process Theory, Predictive Brains

Practice Highlights

- According to the dual process model of cognition diagnostic errors are caused by bias reasoning.

- Interventions to improve diagnosis based on “Cognitive De-biasing” methods report disappointing results.

- The predict brain is a unified model of cognition which accounts for diagnostic errors, the failure of “Cognitive De-biasing” and may point to effective solutions.

- Using appropriate language as simple rules or thumb, to fine-tune predictive processing meta-cognitively may be a practical strategy to improve diagnostic problem solving.

I. INTRODUCTION

Clinical diagnostic expertise is a critical, highly valued, and admired skill (Montgomery, 2006). However, diagnostic errors are common and important adverse events which merit research and effective prevention (Gupta et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2014; Skinner et al., 2016). Thus, it is now widely acknowledged and recognized that concerted efforts are required to improve the research, training and practice of clinical reasoning in improving diagnosis (Simpkin et al., 2017; Singh & Graber, 2015; Zwaan et al., 2013). The consensus among practitioners, researchers and preceptors is that most preventable diagnostic errors are associated with bias reasoning during rapid, non-analytical, default cognitive processing of clinical information (Croskerry, 2013). The most widely held theory which accounts for this observation is the dual process model of cognition (B. Djulbegovic et al., 2012; Evans, 2008; Schuwirth, 2017). It posits that most diagnostic errors reside in intuitive, non-analytical or systems 1 thinking (Croskerry, 2009). Thus, the logical, practical and common sense implication which follows from this assumption is that we should activate and apply analytical or system 2 thinking to counter-check or “De-bias” system 1 errors (Croskerry, 2009). This is a popular notion and it has facilitated the emergence of many schools of clinical reasoning based on training methods designed to deliberately understand, recognise, categorise and avoid specific diagnostic errors arising from system thinking 1 or cognitive bias (Reilly et al., 2013; Rencic et al., 2017; Restrepo et al., 2020). However, careful research on the merits of these interventions under controlled conditions do not show consistent nor clear benefits (G. Norman et al., 2014; G. R. Norman et al., 2017; O’Sullivan & Schofield, 2019; Sherbino et al., 2014; Sibbald et al., 2019; J. N. Walsh et al., 2017). Moreover, even the recognition and categorization of these cognitive error events themselves are deeply confounded by hindsight bias itself (Zwaan et al., 2016). Perhaps, at this juncture, it might be appropriate to consider alternative models of cognition based on advances in multi-disciplinary neuroscience research which have expanded greatly in recent years (Monteiro et al., 2020).

Over the past decade the theory of predictive brains has emerged as an ambitious, unified, convergent and integrated model of cognitive processing from research in a large variety of core domains in cognition which include philosophy, meta-physics, cellular physics, thermodynamics, Associative Learning theory, Bayesian-probability theory, Information theory, machine learning, artificial intelligence, behavioural science, neuro-cognition, neuro-imaging, constructed emotions and psychiatry (Bar, 2011; Barrett, 2017a; Barrett, 2017b; Clark, 2016; Friston, 2010; Hohwy, 2013; Seligman, 2016; Teufel & Fletcher, 2020). It may have profound and practical implications on how we live, work and learn. However, to my knowledge, there is almost no discussion of this novel proposition in either medical education pedagogy or research. Thus, in this presentation I will review recent developments in the predictive brain model of cognition, map its key elements which impacts on pedagogy and research in medical education and propose an application in the training of diagnostic reasoning based on it.

An early version of this work had been presented as an abstract (Lim & Teoh, 2018).

II. METHODS

This is a critical-narrative review of the predictive brain model from Friston’s “The free energy principle” proposition a decade ago to more recent critical examination of the emerging supportive evidence based on neurophysiological studies over the past 5 years (Friston, 2010; K. S. Walsh et al., 2020).

III. RESULTS

A. The Brain is a Frugal Predictive Engine

The Brain Is A Frugal Predictive Engine (General references (Bar, 2011; Barrett, 2017a; Barrett, 2017b; Clark, 2013; Clark, 2016; Friston, 2010; Gilbert & Wilson, 2007; Hohwy, 2013; Seligman, 2016; Seth et al., 2011; Sterling, 2012).

In contrast with traditional top-down, feed-forward models of cognition, the predictive brain model reverses and inverts this process. Perception is characterised as an entirely inferential rapidly adaptive, generative, energy-frugal, context-sensitive action-orientated, probabilistic, predictive process (Tschantz et al., 2020). This system is governed by the need to respond rapidly to ever changing demands from the external environmental and our body’s internal physiological signals (intero-ception) and yet minimise free energy expenditure (or waste) (Friston, 2010; Kleckner et al., 2017; Sterling, 2012). Thus, it is not passive and reactive to new information but predictive and continuously proactive. From very early, elemental and sparse cues it is continuously generating predictive representations based on remembered similar experiences in the past which may include simulations. It performs iterative matching of top down prior representations with bottom up signals and cues in a hierarchy of categories of abstractions and content specificity over scales of space and time (Clark, 2013; Friston & Kiebel, 2009; Spratling, 2017a). This matching process is also sensitive to variations in context and thus enable us to make sense of rapidly changing and complex situations (Clark, 2016).

Cognitive resource, in terms of allocating attention, is only focused on the management of errors in prediction or the mismatch between prior representations and new emergent information. It seeks to minimise prediction errors (PEs) and there is repetitive, recognition-expectation-based signal suppression when this is achieved. Thus, this is a system which only responds to the unfamiliar situation or what it considers as news worthy. This is analogous to Claude Shannons’s classic analysis of “surprisals” in information theory (Shannon et al., 1993). Learning is based on the generation and neural coding of a new predictive representations in memory. The most direct and powerful evidence for this process comes from optogenetic experiments with their exquisitely high degree of resolution in the monitoring and manipulations over space-time of neuronal signalling and behaviour in freely forging rats which show causal linkages between PE, dopamine neurons and learning (Nasser et al., 2017; Steinberg et al., 2013).

The brain intrinsically generates representations of the world in which it finds itself from past experience which is refined by sensory data. New sensory information is represented and inferred in terms of these known causes. Determining which combination of the many possible causes best fits the current sensory data is achieved through a process of minimising the error between the sensory data and the sensory inputs predicted by the expected causes, i.e. the PE. In the service of PE reduction, the brain will also generate motor actions such as saccadic eye movement and foraging behaviour. The prediction arises from a process of “backwards thinking” or inferential Bayesian best guess or approximation based simultaneously on sensory data and prior experience (Chater & Oaksford, 2008; Kersten et al., 2004; Kwisthout et al., 2017a; Kwisthout et al., 2017b; Ting et al., 2015). It is a hierarchical predictive coding process, reflecting the serial organization of the neuronal architecture of cerebral cortex; higher levels are abstract, whereas the lowest level amounts to a prediction of the incoming sensory data (Kolossa et al., 2015; Shipp, 2016; Ting et al., 2015). The actual sensory data is compared to the predicted sensory data, and it is the discrepancies, or ‘error’ that ascends up the hierarchy to refine all higher levels of abstraction in the model. Thus, this is a learning process whereby, with each iteration, the model representations are optimised and encoded in long term memory as the PEs minimise (Friston, FitzGerald, Rigoli et al., 2017; Spratling, 2017b).

This system of neural responses is regulated and fine-tuned by varying the gains on the weightage of the reliability (or precision) of the PE estimate itself. In other words, it is the level of confidence (versus uncertainty) in the PE which determines the intensity of attention allocated to it and strength of coding in memory following its resolution (Clark, 2013; Clark, 2016; Feldman & Friston, 2010; Hohwy, 2013). This regulatory, neuro-modulatory process is impacted by the continuous cascade of action relevant information which is sensitive to both external context and internal interoceptive (i.e. from perception of our own physiological responses) and affective signals (Clark, 2016). This metacognitive capacity to effectively manipulate and re-calibrate the precision of PE itself may be a critical aspect of decision making, problem solving behaviour and learning. (Hohwy, 2013; Picard & Friston, 2014).

B. Clinical Reasoning is Predictive Error Processing and Learning is Predictive Coding

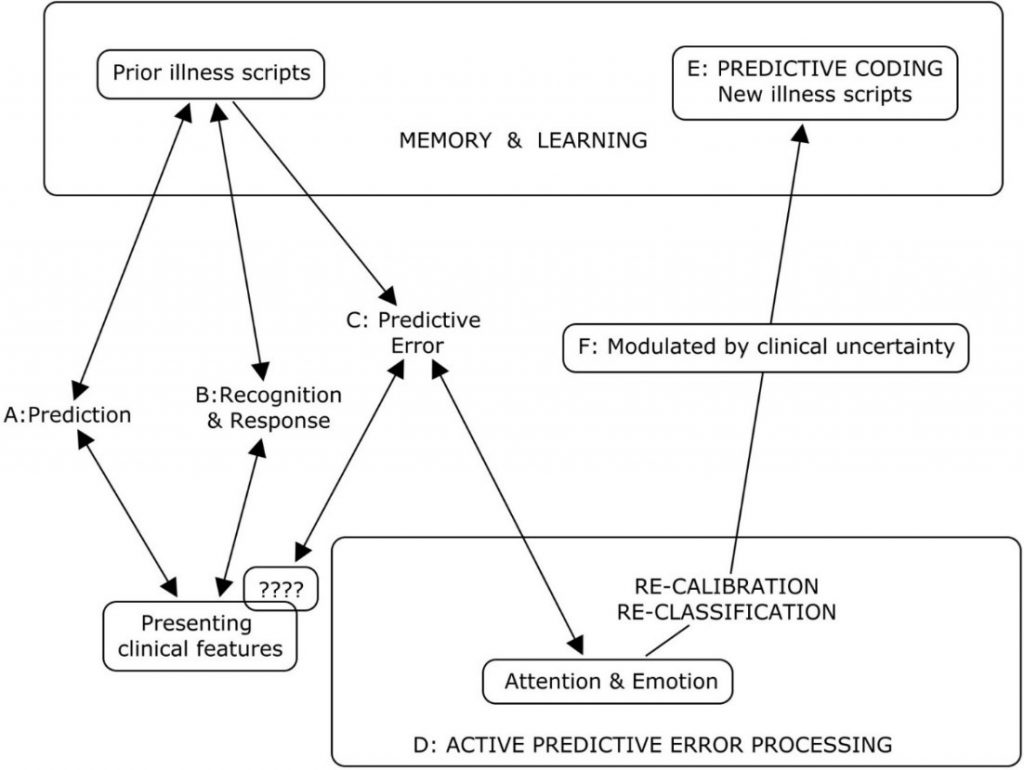

The core processes of the predictive brain which are engaged during diagnostic reasoning are summarised in Table 1 and Figure 1.

|

Core features of the predictive brain model |

Clinical reasoning features and processes |

|

The frugal brain and free energy principle(Friston, 2010) |

Cognitive load in problem solving (Young et al., 2014)

|

|

Iterative matching of top down priors Vs bottom up signals |

Inductive foraging (Donner-Banzhoff & Hertwig, 2014; Donner-Banzhoff et al., 2017) |

|

Predictive error processing |

Pattern recognition in diagnosis |

|

Recognition-expectation-based signal suppression |

Premature closure (Blissett & Sibbald, 2017; Melo et al., 2017) |

|

Hierarchical predictive error coding as learning |

Development of illness scripts (Custers, 2014) |

|

Probabilistic-Bayesian inferential approximations |

Bayesian inference in clinical reasoning |

|

Context sensitivity |

Contextual factors in diagnostic errors(Durning et al., 2010) |

|

Action orientation |

Foraging behaviour in clinical diagnosis (Donner-Banzhoff & Hertwig, 2014; Donner-Banzhoff et al., 2017) |

|

Interoception and affect in prediction error management |

Gut feel and regret (metacognition) |

|

The precision(reliability/uncertainty) of prediction errors |

Clinical uncertainty (metacognition) (Bhise et al., 2017; Simpkin & Schwartzstein, 2016) |

Table 1: Core features of the predictive brain model of cognition manifested as clinical reasoning processes

Legend to Figure 1

A summary of the cognitive processes engaged by the predict brain model during clinical diagnosis

A: Active search for diagnostic clues based on prior experience of similar patients in similar situations.

B: Recognition of key features will activate a series of familiar illness script from long term memory to match with the new case. If this is successful, a diagnosis made and any prediction error signals are rapidly silenced.

C & D: When the illness scripts do not match the presenting features (????), cognition slows down, attention is heightened and further searches are made for additional matching clues and illness scripts. This is iterated until a satisfactory match is found or a new illness script is generated to account for the mismatch.

E: A new variation in the presenting features for that disease is then encoded in memory as a new illness script in memory and thus, a valuable learning moment.

F: The degree of uncertainty or level of confidence in matching key presenting features to a diagnosis is a meta-cognitive skill and a critical expertise in clinical diagnosis. This corresponds to the precision or gain/weightage of prediction errors (Meta cognition) in the predictive brain model.

Figure 1: A summary of the cognitive processes engaged by the predict brain model during clinical diagnosis

Thermodynamic frugality is a central feature of the predictive brain model and in this system, the primacy of attending only to surprises or PEs is pivotal (Friston, 2010). This might be regard as an energy efficient strategy in coping with cognitive load which has been long recognised as an important consideration in clinical problem solving and learning (Young et al., 2014; Van Merrienboer & Sweller, 2010).

From the first moments of a diagnostic encounter the clinician is alert to clues which might point to the diagnosis and begins to generate possible diagnosis scenarios and simulations based upon her prior experience of similar patients and situations (Donner-Banzhoff & Hertwig, 2014). This is iterative and, from a scanty set of presenting features, a plausible diagnosis may be considered within a few seconds to minutes (Donner-Banzhoff & Hertwig, 2014; Donner-Banzhoff et al., 2017). Thus, a familiar illness script is activated from long term memory to match with the new case (Custers, 2014). If this is successful, a particular diagnosis is recognised and any PE signal is rapidly silenced. Functional MRI studies of clinicians during this process showed that highly salient diagnostic information, reducing uncertainty about the diagnosis, rapidly decreased monitoring activity in the frontoparietal attentional network and may contribute to premature diagnostic closure, an important cause of diagnostic errors (Melo et al., 2017). This may be considered a form of diagnosis or recognition related PE signal suppression analogous to the well know phenomenon of repetitive suppression (Blissett & Sibbald, 2017; Bunzeck & Thiel, 2016; Krupat et al., 2017).

In cases where the illness scripts do not match the presenting features, a PE event is encountered, cognition slows down, attention is heightened and further searches are made for additional matching clues and illness scripts (Custers, 2014). This is iterated until a satisfactory match is found or a new illness script is generated to account for the mismatch. This is then encoded in memory as a new variation in the presenting features for that disease and thus, a valuable learning moment. Bayesian inference is a fundamental feature of both clinical diagnostic reasoning and the predictive brain model (Chater & Oaksford, 2008).

As in the predictive brain model, external contextual factors and internal emotional and physiological responses such as gut feeling and regret, exert profound effects on clinical decision making (M. Djulbegovic et al., 2015; Durning et al., 2010; Stolper & van de Wiel, 2014; Stolper et al., 2014). Also active inductive foraging behaviour in searching for diagnostic clues described in experienced primary physicians is analogous to behaviour directed at reducing PEs (Donner-Banzhoff & Hertwig, 2014; Donner-Banzhoff et al., 2017). The precision or gain/weightage of PEs is manifested metacognitively as uncertainties or levels of confidence in clinical reasoning (Sandved-Smith et al., 2020). Metacognition is a critical capacity and expertise in effective decision making. (Bhise et al., 2017; Fleming & Frith, 2014; Simpkin & Schwartzstein, 2016).

C. Why Applying the Dual Process Model May Not Improve Clinical Reasoning

Recent studies which have applied the popular dual process model to improve diagnostic performance by “cognitive de-biasing” in clinicians have yielded disappointing results (G. R. Norman et al., 2017). Cognitive processing of the predictive brain as the dominant default network mode of operation may account for this setback since de-biasing is not naturistic, requires retrospective “off line” processing after the monitoring salience network has already shut off (Krupat et al., 2017; Melo et al., 2017). It is not thermodynamically frugal and thus, may not be sustainable in routine practice (Friston, 2010; Young et al., 2014). Even Daniel Kahneman himself admits that, despite decades of research in cognitive bias he is unable to exert agency of the moment and de-bias himself (Kahneman, 2013). This will be more so in novice diagnosticians in the training phase who have scanty illness scripts and limited tolerance of any further cognitive loading (Young et al., 2014). The failure to even identify cognitive biases reliably by clinicians due to hindsight bias itself suggests that this intervention will be the least effective one in improving diagnostic reasoning (Zwaan et al., 2016).

D. Using Words to Fine Tune the Precision of Diagnostic Prediction Error

Daniel Kahneman, the foremost expert on cognitive bias, cautions that, contrary to what some experts in medical education advice, avoiding bias is ineffective in improving decision making under uncertainty (Restrepo et al., 2020). By contrast he suggested that we apply simple, common sense, rules of thumb (Kahneman et al., 2016). I hypothesise that instructing clinical trainees to use appropriate words to self in the diagnostic setting during active, naturalistic PE processing before the diagnosis is made and not as a retrospective counter check to cognition afterwards may be a way forward (Betz et al., 2019; Clark, 2016; Lupyan, 2017). In a multi-center, iterative thematic content analysis of over 2,000 cases of diagnostic errors with a structured taxonomy, Schiff and colleagues identified a limited number of pitfall themes which were overlooked and predisposed physicians to reasoning errors (Reyes Nieva H et al., 2017). These pitfall themes included three which are of particular interest in relation to naturalistic PE processing namely: (1) counter diagnostic cues, (2) things that do not fit and (3) red flags (Reyes Nieva H et al., 2017). Thus, we instructed our student interns and internal medicine residents to pay particular attend to these three diagnostic pitfalls during review of new patients and clinical problems (Lim & Teoh, 2018). They were required to append the following sub-headings to their clerking impression in the patient’s electronic health record (eHR): (a) Counter diagnostic features; (b) Things that do not fit; (c) Red flags. This template was added after the resident had entered his or her numerated list of diagnoses or issues. “Counter diagnostic features” was defined as symptoms, signs or investigations which were inconsistent with the proposed primary diagnosis. “Things that do not fit” was defined as any finding that could not be reasonably accounted for taking into account the main and differential diagnoses. “Red flags” were defined as findings which raised the possibility of a more serious underlying illness requiring early diagnosis or intervention. The attending physicians were required, during bedside rounds, to give feedback on these points and make amendments to the eHR as appropriate. This exercise may give us an opportunity to see if we can improve diagnostic accuracy by using pivotal words-to-self in the appropriate setting to maintain cognitive openness, flexibility and thus, avoid premature (Krupat et al., 2017). It is also a valuable critical, metacognitive thinking habit to inculcate in tyro diagnosticians (Carpenter et al., 2019).

IV. CONCLUSION

The theory of predictive brains has emerged as a major narrative in the understanding of how our mind works. It may account for the limitations of interventions designed to improve diagnostic problem solving which are based on the dual process theory of cognition. Exploiting predictive brains by employing language to optimise metacognition may be a way forward.

Note on Contributor

Lim designed the paper, reviewed the literature, drafted and revised it.

Ethical Approval

There is no ethical approval associated with this paper.

Funding

No funding sources are associated with this paper.

Declaration of Interest

No conflicts of interest are associated with this paper.

References

Bar, M. (2011). Predictions in the brain using our past to generate a future (pp. xiv, 383 p. ill. (some col.) 327 cm.).

Barrett, L. F. (2017a). How emotions are made: the secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Barrett, L. F. (2017b). The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw154

Betz, N., Hoemann, K., & Barrett, L. F. (2019). Words are a context for mental inference. Emotion, 19(8), 1463-1477. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000510

Bhise, V., Rajan, S. S., Sittig, D. F., Morgan, R. O., Chaudhary, P., & Singh, H. (2017). Defining and measuring diagnostic uncertainty in medicine: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4164-1

Blissett, S., & Sibbald, M. (2017). Closing in on premature closure bias. Medical Education, 51(11), 1095-1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13452

Bunzeck, N., & Thiel, C. (2016). Neurochemical modulation of repetition suppression and novelty signals in the human brain. Cortex, 80, 161-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2015.10.013

Carpenter, J., Sherman, M. T., Kievit, R. A., Seth, A. K., Lau, H., & Fleming, S. M. (2019). Domain-general enhancements of metacognitive ability through adaptive training. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 148(1), 51-64. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000505

Chater, N., & Oaksford, M. (2008). The probabilistic mind : prospects for Bayesian cognitive science. Oxford University Press.

Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12000477

Clark, A. (2016). Surfing uncertainty : Prediction, action, and the embodied mind: Oxford University Press.

Croskerry, P. (2009). Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: Applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 14 Suppl 1, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-009-9182-2

Croskerry, P. (2013). From mindless to mindful practice–cognitive bias and clinical decision making. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368(26), 2445–2448. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1303712

Custers, E. J. (2014). Thirty years of illness scripts: Theoretical origins and practical applications. Medical Teacher, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.956052

Djulbegovic, B., Hozo, I., Beckstead, J., Tsalatsanis, A., & Pauker, S. G. (2012). Dual processing model of medical decision-making. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 12, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-94

Djulbegovic, M., Beckstead, J., Elqayam, S., Reljic, T., Kumar, A., Paidas, C., & Djulbegovic, B. (2015). Thinking styles and regret in physicians. Public Library of Science One, 10(8), e0134038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134038

Donner-Banzhoff, N., & Hertwig, R. (2014). Inductive foraging: Improving the diagnostic yield of primary care consultations. European Journal of General Practice, 20(1), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814788.2013.805197

Donner-Banzhoff, N., Seidel, J., Sikeler, A. M., Bosner, S., Vogelmeier, M., Westram, A., & Gigerenzer, G. (2017). The phenomenology of the diagnostic process: A primary care-based survey. Medical Decision Making, 37(1), 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X16653401

Durning, S. J., Artino, A. R., Jr., Pangaro, L. N., van der Vleuten, C., & Schuwirth, L. (2010). Perspective: redefining context in the clinical encounter: Implications for research and training in medical education. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 85(5), 894–901. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d7427c

Evans, J. S. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

Feldman, H., & Friston, K. J. (2010). Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2010.00215

Fleming, S. M., & Frith, C. D. (2014). The cognitive neuroscience of metacognition. Springer.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

Friston, K., FitzGerald, T., Rigoli, F., Schwartenbeck, P., & Pezzulo, G. (2017). Active inference: A process theory. Neural Computation, 29(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1162/NECO_a_00912

Friston, K., & Kiebel, S. (2009). Predictive coding under the free-energy principle. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 364(1521), 1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0300

Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351-1354. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144161

Gupta, A., Snyder, A., Kachalia, A., Flanders, S., Saint, S., & Chopra, V. (2017). Malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors in the hospital. BMJ Quality and Safety, 27(1), 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006774

Hohwy, J. (2013). The predictive mind. Oxford University Press..

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, fast and slow (1st pbk. ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., Rosenfield, A. M., Gandhi, L., & Blaser, T. O. M. (2016). NOISE: How to overcome the high, hidden cost of inconsistent decision making. (cover story). Harvard Business Review, 94(10), 38-46. Retrieved from http://libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=118307773&site=ehost-live

Kersten, D., Mamassian, P., & Yuille, A. (2004). Object perception as bayesian inference. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 271–304. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142005

Kleckner, I. R., Zhang, J., Touroutoglou, A., Chanes, L., Xia, C., Simmons, W. K., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2017). Evidence for a large-scale brain system supporting allostasis and interoception in humans. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 0069. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0069

Kolossa, A., Kopp, B., & Fingscheidt, T. (2015). A computational analysis of the neural bases of Bayesian inference. Neuroimage, 106, 222-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.007

Krupat, E., Wormwood, J., Schwartzstein, R. M., & Richards, J. B. (2017). Avoiding premature closure and reaching diagnostic accuracy: Some key predictive factors. Medical Education, 51(11), 1127-1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13382

Kwisthout, J., Bekkering, H., & van Rooij, I. (2017a). To be precise, the details don’t matter: On predictive processing, precision, and level of detail of predictions. Brain and Cognition, 112, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.02.008

Kwisthout, J., Phillips, W. A., Seth, A. K., van Rooij, I., & Clark, A. (2017b). Editorial to the special issue on perspectives on human probabilistic inference and the ‘Bayesian brain’. Brain and Cognition, 112, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.12.002

Lim T.K., & Teoh, C. M. (2018). Exploiting predictive brains for better diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl), 5(3), eA40. Retrieved from https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/dx/5/3/article-peA1.xml

Lupyan, G. (2017). Changing what you see by changing what you know: The role of attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00553

Melo, M., Gusso, G. D. F., Levites, M., Amaro, E., Jr., Massad, E., Lotufo, P. A., & Friston, K. J. (2017). How doctors diagnose diseases and prescribe treatments: An fMRI study of diagnostic salience. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1304. http://observatorio.fm.usp.br/handle/OPI/19951

Monteiro, S., Sherbino, J., Sibbald, M., & Norman, G. (2020). Critical thinking, biases and dual processing: The enduring myth of generalisable skills. Medical Education, 54(1), 66-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13872

Montgomery, K. (2006). How doctors think: Clinical judgement and the practice of medicine. Oxford University Press.

Nasser, H. M., Calu, D. J., Schoenbaum, G., & Sharpe, M. J. (2017). The dopamine prediction error: Contributions to associative models of reward learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00244

Norman, G., Sherbino, J., Dore, K., Wood, T., Young, M., Gaissmaier, W., & Monteiro, S. (2014). The etiology of diagnostic errors: A controlled trial of system 1 versus system 2 reasoning. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(2), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000105

Norman, G. R., Monteiro, S. D., Sherbino, J., Ilgen, J. S., Schmidt, H. G., & Mamede, S. (2017). The Causes of Errors in Clinical Reasoning: Cognitive Biases, Knowledge Deficits, and Dual Process Thinking. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 92(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

O’Sullivan, E. D., & Schofield, S. J. (2019). A cognitive forcing tool to mitigate cognitive bias – A randomised control trial. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1444-3

Picard, F., & Friston, K. (2014). Predictions, perception, and a sense of self. Neurology, 83(12), 1112-1118. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000798

Reilly, J. B., Ogdie, A. R., Von Feldt, J. M., & Myers, J. S. (2013). Teaching about how doctors think: A longitudinal curriculum in cognitive bias and diagnostic error for residents. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(12), 1044–1050. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001987

Rencic, J., Trowbridge, R. L., Jr., Fagan, M., Szauter, K., & Durning, S. (2017). Clinical reasoning education at us medical schools: Results from a national survey of internal medicine clerkship directors. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(11), 1242–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4159-y

Restrepo, D., Armstrong, K. A., & Metlay, J. P. (2020). Annals Clinical Decision Making: Avoiding Cognitive Errors in Clinical Decision Making. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(11), 747–751. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-3692

Reyes Nieva H., V. M., Wright A, Singh H, Ruan E, Schiff G. (2017). Diagnostic Pitfalls: A New Approach to Understand and Prevent Diagnostic Error. In Diagnosis (Vol. 4, pp. eA1). https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/dx/5/4/article-peA59.xml

Sandved-Smith, L., Hesp, C., Lutz, A., Mattout, J., Friston, K., & Ramstead, M. (2020, June 10). Towards a formal neurophenomenology of metacognition: Modelling meta-awareness, mental action, and attentional control with deep active inference. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5jh3c

Schuwirth, L. (2017). When I say … dual-processing theory. Medical Education, 51(9), 888–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13249

Seligman, M. E. P. (2016). Homo Prospectus. Oxford University Pres.

Seth, A. K., Suzuki, K., & Critchley, H. D. (2011). An interoceptive predictive coding model of conscious presence. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00395

Shannon, C. E., Sloane, N. J. A., Wyner, A. D., & IEEE Information Theory Society. (1993). Claude Elwood Shannon : Collected Papers. IEEE Press.

Sherbino, J., Kulasegaram, K., Howey, E., & Norman, G. (2014). Ineffectiveness of cognitive forcing strategies to reduce biases in diagnostic reasoning: A controlled trial. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.2310/8000.2013.130860

Shipp, S. (2016). Neural Elements for Predictive Coding. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1792. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01792

Sibbald, M., Sherbino, J., Ilgen, J. S., Zwaan, L., Blissett, S., Monteiro, S., & Norman, G. (2019). Debiasing versus knowledge retrieval checklists to reduce diagnostic error in ECG interpretation. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 24(3), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09875-8

Simpkin, A. L., & Schwartzstein, R. M. (2016). Tolerating uncertainty – The next medical revolution? The New England Journal of Medicine, 375(18), 1713–1715. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1606402

Simpkin, A. L., Vyas, J. M., & Armstrong, K. A. (2017). Diagnostic Reasoning: An endangered competency in internal medicine training. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(7), 507–508. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0163

Singh, H., & Graber, M. L. (2015). Improving diagnosis in health care- The next imperative for patient safety. The New England Journal of Medicine, 373(26), 2493–2495. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1512241

Singh, H., Meyer, A. N., & Thomas, E. J. (2014). The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: Estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(9), 727–731. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002627

Skinner, T. R., Scott, I. A., & Martin, J. H. (2016). Diagnostic errors in older patients: A systematic review of incidence and potential causes in seven prevalent diseases. International Journal of General Medicine, 9, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S96741

Spratling, M. W. (2017a). A hierarchical predictive coding model of object recognition in natural images. Cognitive Computation, 9(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-016-9445-1

Spratling, M. W. (2017b). A review of predictive coding algorithms. Brain and Cognition, 112, 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2015.11.003

Steinberg, E. E., Keiflin, R., Boivin, J. R., Witten, I. B., Deisseroth, K., & Janak, P. H. (2013). A causal link between prediction errors, dopamine neurons and learning. Nature Neuroscience, 16(7), 966–973. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3413

Sterling, P. (2012). Allostasis: A model of predictive regulation. Physiology & Behavior, 106(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.0044

Stolper, C. F., & van de Wiel, M. W. (2014). EBM and gut feelings. Medical Teacher, 36(1), 87-88. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.835390