A comparison of four models of professionalism in medical education

Submitted: 25 May 2020

Accepted: 30 December 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 24-31

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/RA2314

Maria Isabel Atienza

Curriculum and Instruction, College of Medicine, San Beda University, Philippines

Institute of Pediatrics & Child Health, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Global City, Philippines

Abstract

Introduction: The prevailing consensus is that medical professionalism must be formally included as a programme in the undergraduate medical curriculum.

Methods: A literature search was conducted to identify institutions that can serve as models for incorporating professionalism in medical education. Differences and similarities were highlighted based on a framework for the comparison which included the following features: Definition of professionalism, curricular design, student selection, teaching and learning innovations, role modelling and methods of assessment.

Results: Four models for integrating professionalism in medical education were chosen: Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM), University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM), University of Queensland (UQ) School of Medicine, and Mayo Clinic and Mayo Medical School. The task of preparing a programme on medical professionalism requires a well-described definition to set the direction for planning, implementing, and institutionalising professionalism. The programmes are best woven in all levels of medical education from the pre-clinical to the clinical years. The faculty physicians and the rest of the institution’s staff must also undergo a similar programme for professionalism.

Conclusion: The development of all scopes of professionalism requires constant planning, feedback and remediation. The students’ ability to handle professionalism challenges are related to how much learning situations the students encounter during medical school. The learning situations must be adjusted according to the level of responsibilities given to students. The goal of learning is to enable students to grow from a novice to a competent level and afterwards to a proficient and expert level handling professionalism challenges in medicine.

Keywords: Medical Professionalism, Medical Curriculum, Role Modelling in Medical Education, Culture of Medical Professionalism

Practice Highlights

- A programme on medical professionalism in education starts with a working definition of the term.

- The culture of professionalism must be articulated in the school’s vision and mission.

- The professionalism programme must be woven through the four years of medical education.

- Role models are essential in teaching medical professionalism.

- For teaching medical professionalism, a nurturing environment is preferable over punitive actions.

I. INTRODUCTION

There is a prevailing sentiment that professionalism must be taught formally and explicitly in all medical schools (Cruess & Cruess, 2006). This review aims to highlight some exceptional models for incorporating professionalism in the curriculum of medical education. The models were chosen based on the consensus among medical educators that medical schools need to respond to the following observations and recommendations from the vast literature on this subject:

1. Society expects physicians to act professionally (Lynch et al., 2004; Mueller, 2009; O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

2. There is a link between unprofessional behaviour in medical school and subsequent practice (Mueller, 2009; O’Sullivan et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2008).

3. Professionalism is associated with improved medical outcomes (Mueller, 2009).

4. Professionalism needs to be taught in the undergraduate medical institutions (O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

5. The teaching and learning must be coupled with a carefully constructed means of assessment of professionalism and professional behaviour (O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

6.Students must be supported in developing the skills for continuing professional development throughout their career (O’Sullivan et al., 2012).

This review aims to utilise these assumptions as a framework for reviewing and comparing models for the incorporation of medical professionalism in the curriculum of medical schools. This paper aims to provide answers to this question: Among medical schools that have incorporated professionalism in the medical curriculum, what are the salient features of the programmes that may be adopted by other institutions in need of such curricular innovations?

II. METHODOLOGY

A literature search was conducted to search for relevant institutions that have established a programme for incorporating professionalism in their medical schools. There was no attempt to review all published reports but to focus on the schools that can serve as models for other institutions in need of such curricular innovations. All information concerning the programmes were taken from the published journal articles which were authored by the faculty members in charge of the respective programmes on professionalism. An independent appraisal was done using a framework adopted from a systematic review by Passi and co-workers which included the following criteria: institutional definition of professionalism, curricular design, student selection, teaching and learning innovations, role modelling and assessment (Passi et al., 2010).

III. RESULTS

The review of literature on undergraduate medical programmes on professionalism revealed four notable models that describe how their institutions have integrated the teaching and assessment of professionalism among medical students, namely, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM), University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM), University of Queensland (UQ) School of Medicine, and Mayo Clinic School of Medicine.

A. Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM)

A model applied at the VUSM focused on an Academic Leadership Programme (ALP) established to address unprofessional and disruptive behaviours of students (Hickson et al., 2007). The ALP is a programme designed for leaders and administrators tasked to identify and tackle unprofessional behaviours. A four-level graduated intervention programme was designed to deal with the incident cases occurring in the school. The tenets of professionalism are introduced to the medical students through a discussion of case vignettes dealing with unprofessional behaviour. The faculty are also asked to sign a creed and a commitment to be role models of professional behaviour for graduates and medical students.

A so-called “disruptive behaviour pyramid” serves as a guide for identifying and assessing variable degrees of unprofessional behaviour with their corresponding intervention. Surveillance systems have also been put in place to detect unprofessional behaviour of students and physicians from patients, visitors, and health care team members (Hickson et al., 2007).

B. University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM)

The UWSOM introduced their professionalism curriculum through the development of the Colleges programme for the preclinical medical students. Outstanding faculty-clinicians are selected and trained to teach and model clinical skills with small groups of students at the bedside from the second-year level until the time of their graduation. The institution recognises these faculty as role model physicians working closely with students in the care of patients (Goldstein et al., 2006).

The school promotes an “ecology of professionalism” in the campus and provides an environment for group discussions, role modelling and reflection among the different year levels of medical education. Professionalism is an institution wide concern such that both students and the faculty are required to undergo training on professionalism. In order to make the programme more meaningful, the institution added the “Patients as Teachers” project whereby the patients are asked to provide feedback and to offer advice to the medical students. The loop of learning involving the faculty, the students, and the patient is deemed as a “safe” and respectful educational environment that encourages professionalism as an institutional-wide responsibility (Goldstein et al., 2006).

C. University of Queensland (UQ) School of Medicine

The programme of the University of Queensland integrates medical ethics, law and the professionalism curriculum with a “Personal and Professional Development” process (Parker et al., 2008). Throughout the four-year levels of undergraduate medical education, topics of ethics and professional development are taught and assessed through written tests and objective structured clinical examinations. A document called “Commitment to Professionalism” is signed by every student at the start of their first-year level to reinforce the principles and their acceptance of the expectations of the school, including attendance.

A “Pyramid of Professionalism” serves as a model to identify the students that require supervision and eventually pass or fail the programme. Students are assessed at several levels with a committee providing support, feedback and remediation. Professional conduct ultimately affects the student’s promotion to the next year level (Parker et al., 2008).

D. Mayo Clinic School of Medicine

The Mayo Clinic incorporated professionalism into medical education by first articulating its culture through a statement of the institution’s primary value: “The needs of the patient come first”. Their mission statement declares that “Mayo will provide the best care to every patient every day through integrated clinical practice, education, and research.” This culture is expressed in all the institution’s policies and procedures (Mueller, 2009).

Mayo has adopted a framework for professionalism which places clinical competence, communication skills and sound understanding of ethics at its foundation (Mueller, 2015). Built on this foundation are the pillars or the key attributes of accountability, altruism, excellence and humanism. With this framework and the culture that Mayo promotes, professionalism teaching and assessment programmes have been implemented involving all levels of learners of the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine. An intensive bioethics courses and a leadership and professionalism course is given to the first-year medical students. For the second-year level, the “Advance Doctoring” professionalism reflective writing programme is given. For the third-year level, the “Safe Harbor” professionalism programme and an intensive bioethics course is applied (Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015).

More professionalism and ethics teaching are incorporated into different courses and clinical rotations throughout the four-year curriculum. Other interesting features include an elective course in Professionalism and Ethics related to the students’ career interest. Professionalism assessments are carried out by way of formative and summative feedback and professionalism “portfolios” which are summarized for their future applications for further training (Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015).

The Mayo Clinic faculty physicians also have their share of professionalism modules. The new physician staff are required to attend a complete series of professionalism courses. All faculty physicians have to take a complete web-based, interactive module on professionalism in order to maintain their status as practicing physicians. They also undergo a 360-degree review to identify and address lapses in professionalism. The non-physician allied healthcare staff of the institution also have their own professionalism programme to support Mayo’s service philosophy (Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015).

The core value of professionalism continues to guide the clinic in its leadership practices and management strategies. The value-based culture serves as a positive hidden curriculum that promotes the achievement of desired educational outcomes among the health care professionals (Viggiano et al., 2007).

E. Institutional Definitions of Medical Professionalism

The lack of a universal definition of medical professionalism has resulted in medical schools formulating what is suitable to their context (O’Sullivan et al., 2012). Among the four curricular models, Mayo clearly expounded on their definition of medical professionalism. This institution defined professionalism by embracing seven patient care-related and seven practice environment-related attributes as summarised in the Mayo Clinic Model of Care (Mueller, 2009).

In the case of UQ, while no clear-cut definition of professionalism was described in the journal article, the institution instead presented a list of topics of medical ethics and professional development for formal training and instruction. A review of the UQ listing shows that most of the elements of professionalism covered were related to the theme of public or societal professionalism, such as Medical Practice and the Law, Accountability and Self-Regulation, Inappropriate Practice and Medical Over servicing, and Commercialization of Medicine (Parker et al., 2008).

A second list of elements of professionalism was prepared by the UQ faculty, and this list contained attributes related to intrapersonal and interpersonal professionalism. This list served as their guide to identify students who required support, feedback or remediation through the process called the Pyramid of Professionalism (Parker et al., 2008).

The VUSM also did not state the elements of professionalism in their model. Instead, the institution focused on defining the unprofessional or disruptive behaviours that required case discussions in particular year levels of medical education. These were the same unacceptable behaviours that were used to identify students who needed immediate intervention ranging from non-punitive interventions up to the imposition of disciplinary processes if needed (Hickson et al., 2007).

The UWSOM developed a list of elements of professionalism that served as benchmarks for preclinical students, namely, the principles of altruism, honour and integrity, compassion, communication, respect, accountability and responsibility, scholarship, excellence and leadership. Despite this listing, the faculty received feedback from the students that the idea of professionalism and cultural competency remained unclear to them. This feedback came with a request from the students that the teaching of professionalism should be “more specific, clinically relevant, and challenging” (Goldstein et al., 2006).

F. Comparison of Programme Implementation

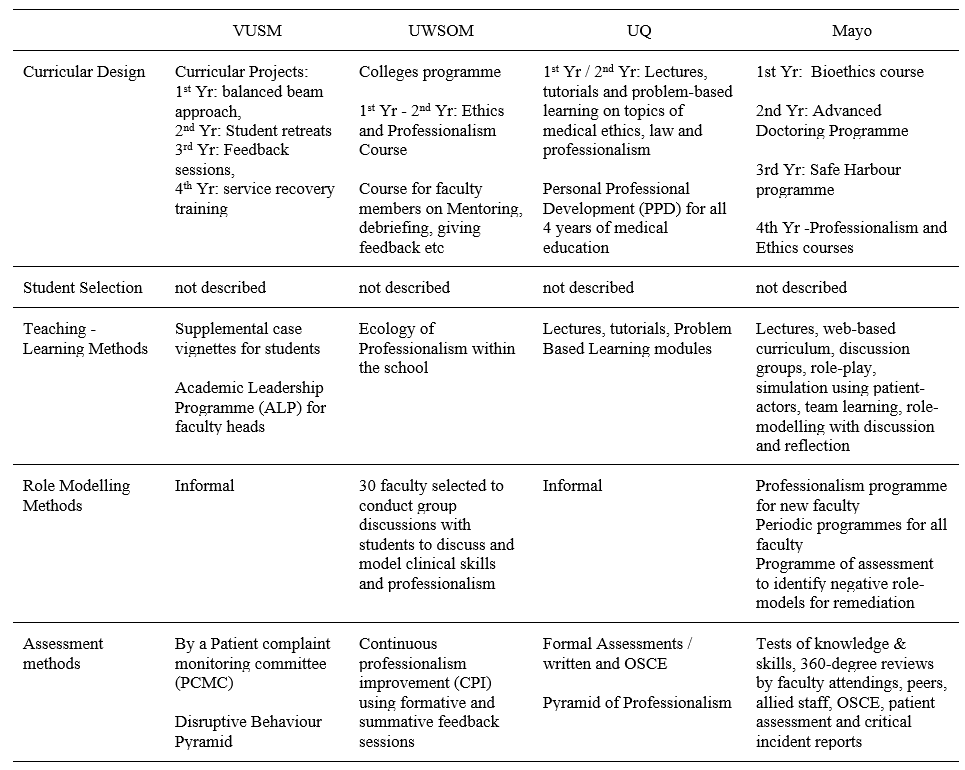

A systematic review (Passi et al., 2010) was done with the aim to summarise the evidence on methods used by medical schools to promote medical professionalism. Five main strategic areas to promote the development of professionalism in medical education were identified from the review: Curriculum design, student selection, teaching and learning methods, role modelling and assessment methods. These five areas can be used as guideposts in reviewing school programmes on professionalism. Table 1 shows a comparison of the four models presented earlier.

G. Similar Features in the Four Models

These are the features common to all four models: (1) Commitment of the leadership of the institution to embark on integrating professionalism into the curriculum, (2) Built-in programme for training of faculty for teaching and modelling of clinical skills, and (3) Vertical integration of the programme of professionalism from preclinical to clinical years.

These features are significant means to heighten the attention of both students and faculty to the need for growth in the area of professionalism. This will also help institutionalize professionalism. The journals on the models did not mention any policy regarding the screening for unprofessional behaviour during the student selection process.

H. Differences in the Four Models

Major differences are evident in the approach to teaching professionalism in the four curricular models.

1) The formal teaching and learning experience of the students of the four schools were varied in terms of duration and delivery of instruction: UWSOM and Mayo incorporates a formal course throughout the four years of medical education. In Mayo, all faculty physicians are trained and involved in the training of students for professionalism. UWSOM, on the other hand, has a select group of thirty faculty assigned for this purpose. UQ described a formal course on professionalism in the first two years of medical education. After the first 2 years, UQ proceeds to the clinical years of medical education using the personal and professional development (PPD) process of identifying personal and professional shortcomings among the students.

The approach taken by VUSM is more interventional in nature. Although short problem-based discussions are provided in the four-year levels of medical education, the main thrust of the programme is on identifying and rectifying incident cases of unprofessional behaviour. Its basis rests on the idea that “failing to address unprofessional behaviour simply promotes more of it.” The VUSM model mentions four graduated interventions as a disciplinary measure to address unprofessional behaviour.

2) The four schools also differed in their assessment methods: VUSM focuses on immediate recognition and grading using the “disruptive behaviour pyramid” to determine the appropriate intervention. UWSOM uses reflection and feedback in the preclinical years followed by a “closed loop” system of obtaining feedback from patients and faculty. Deficiencies in professional behaviour are identified so that remediation may be provided to ensure that only students who are ready will graduate or advance to the next year (Hickson et al., 2007).

(Goldstein et al., 2006; Hickson et al., 2007; Mueller, 2009; Mueller, 2015; Parker et al., 2008)Table 1. Comparative Summary of Four Models of Educational Programme for Teaching Medical Professionalism

UQ focuses more on written tests and objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE) in the preclinical years. Because the school recognises that these assessment methods may not necessarily measure actual attitudes, the personal and professional development (PPD) process serves as a means directed towards identifying students with problems who are then referred to a committee for support and remediation (Parker et al., 2008).

Mayo has a more comprehensive assessment method by including a 360-degree review from faculty attendings, peers, allied staff and patients to complement the written tests and OSCE (Mueller, 2009).

3) Role modelling: On the area of role modelling, UWSOM has developed a formal programme to train select faculty members to promote role modelling as a means of teaching students. The programme to promote an “ecology of professionalism” within the institution is unique to UWSOM. This is the school’s way of making professionalism an institution-wide responsibility and yet maintains a “safe” educational environment for learning and improvement (Goldstein et al., 2006).

Mayo, on the other hand, has required all faculty and staff physicians to attend and successfully complete a series of modules on professionalism, physician-patient communication, self-awareness, and diversity. Maintaining the culture of professionalism in the Mayo Clinic is a result of a continuing process of allowing ethics and professionalism to be woven into the courses and clinical rotations (Mueller, 2009).

I. Professionalism in Medical Education in the Future

Much progress has been attained in the last decade when various models for incorporating professionalism in medical education have been disseminated in various journals. The Bioethics Core Curriculum introduced by the UNESCO also declared that bioethical principles and human rights must be taught early to medical students and that Medical Ethics, which is a branch of Bioethics, must be taught in all levels of education (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2008).

The Medical Ethics Manual released by the World Medical Association (WMA) provided a basic and universally used curriculum for the teaching of medical ethics. The WMA curriculum includes professionalism as a key component needed for the inclusion of Medical Ethics and Human Rights as an obligatory course for medical schools worldwide (Williams, 2015).

It has been observed that professionalism taught through time-based training might not be sufficient to address the changing healthcare environment and new learners. For the current generation of learners, specialty training must now be aligned with global standards such as that of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The ACGME standards incorporates professionalism and system-based practice as core components of the curriculum that begins with acquisition of medical knowledge and clinical skills.

Moving forward to the future necessitates the development of methods of assessment of professionalism as a means to successfully teach these professional behaviours (Chay, 2019).

Another key step in the future includes the teaching of professionalism as part of health professions education. Future academic health centres will need more medical educators who can pursue further education and help foster an environment that supports educator development. This key step will help in the attainment of long-term goals and to adapt to the changes in medical education (Dickinson et al., 2020).

Providing doctors with professional models as they move from novice to expert in their professional career will be instrumental as a framework for education. One clear example is the professional identity model that incorporated leadership, followership and team-working roles A more rounded and mature professional identity eventually develops that would set these doctors as models of professionalism for other health workers (McKimm et al., 2017).

IV. CONCLUSION

The unresolved definition of medical professionalism has made the incorporation of programmes on professionalism quite challenging. Any programme that will be implemented must be well thought of and tailored to the needs of the institution and all stakeholders. Analysing unique contexts of the curricular programme will be the key to keep any programme on professionalism relevant and viable.

The fact is that there are few curricular models for the incorporation of medical professionalism into the medical curriculum. This process is not an easy task and needs a strong institutional commitment and resolve for it to be successfully implemented. The four models were amazing attempts to incorporate professionalism in medical education. No formal evaluation has been published concerning this. Based on the comparative analysis of the four models, certain aspects should be highlighted so that we could possibly learn from them:

1. The task of preparing a programme on medical professionalism would be more systematic if the institution starts with a working definition of professionalism. This was seen in Mayo where a well-described definition set the direction for planning, implementing and institutionalising professionalism.

2. The culture of professionalism needs to be articulated institutionally and incorporated in the institution’s vision, mission, goals and policies. Mayo’s declaration of its primary value that “the needs of the patient come first” sets the stage for an atmosphere that is conducive to serving with professionalism.

UWSOM also opened its door to a culture of professionalism by declaring an “ecology of professionalism”. However, its implementation may have been limited when the Colleges programme for the purpose of institutionalising professionalism was limited to thirty designated faculty and role models.

3. The professionalism programme must be woven in all levels of medical education from the pre-clinical to the clinical years. Just like any competency, acquiring the values and skills and putting it into practice requires constant learning and reinforcement throughout the years of education.

Mayo and VUSM have prepared programmes for all the four years of medical education. Both institutions have crafted programmes for the pre-clinical years and have provided teaching and learning activities such as lectures, problem-based learning, small group discussions and feedback. Mayo engaged their students in the clinical years in elective experiences in professionalism and ethics and a “professionalism portfolio” for all students. VUSM designed a programme for the clinical year that was limited to a service recovery training for the purpose of addressing actual patient complaints.

4. Role models are essential in teaching professionalism because they can greatly influence attitudes and behaviours. Unprofessional physician behaviours such as disrespect and abuse of medical personnel, and refusal to complete duties must be corrected. If left unchecked, the observing medical students may consider such behaviours as normal (Mueller, 2009). These are among the ill effects of a hidden curriculum that occurs when an institution lacks role models. For a programme on professionalism to be successful, the faculty physicians and the rest of the healthcare team and institution’s staff need to undergo professionalism programmes applicable to their needs and roles.

In the case of UWSOM, a group of 30 selected faculty underwent training while in Mayo, all faculty underwent a professionalism programme.

5. Based on the curricular models described, it appears that a nurturing environment is preferable over punitive actions. The development of all scopes of professionalism from the intrapersonal to interpersonal to societal professionalism requires constant discussion, feedback and remediation. Although repetitive unprofessional behaviours may have consequences, the medical trainee will need to go through the nurturing process in order to fully imbibe the heart and soul of a medical professional.

6. The ability to handle professionalism challenges follows a learning curve as well. The levels of difficulty of professionalism challenges are related to how much learning situations a student may have encountered. The goal is to move from novice to competent to proficient and hopefully to an expert level of handling professionalism challenges just like all other aspects of learning in medicine.

The ability of the future generation of physicians to serve society ultimately rests on how professionalism has been woven into the curriculum in medical education. How to incorporate professionalism will be a continuing challenge for all medical educators.

Note on Contributor

Dr. Maria Isabel M. Atienza, Professor, San Beda University College of Medicine, Philippines and Head, Institute of Pediatrics & Child Health, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Global City developed the methodological framework for the study and performed data collection and data analysis as part of her PhD research, and wrote and approved the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This review article was not submitted for IRB/ethical approval.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the insightful suggestions of the Vice Dean of San Beda University College of Medicine: Dr Noel Atienza.

Funding

This review article did not receive any funding.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Chay, O. M. (2019). Transformation of medical education over the years – A personal view. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 4(1), 59-61. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2019-4-1/pv1076

Cruess, R. L., & Cruess, S. R. (2006). Teaching professionalism: General principles. Medical Teacher, 28(3), 205-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600643653

Dickinson, B. L., Chen, Z. X., & Haramati, A. (2020). Supporting medical science educators: A matter of self-esteem, identity, and promotion opportunities. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(3), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2020-5-3/pv2164

Goldstein, E. A., Maestas, R. R., Fryer-Edwards, K., Wenrich, M. D., Oelschlager, A.-M. A., Baernstein, A., & Kimball, H. R. (2006). Professionalism in medical education: An institutional challenge. Academic Medicine, 81(10), 871-876. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.acm.0000238199.37217.68

Hickson, G. B., Pichert, J. W., Webb, L. E., & Gabbe, S. G. (2007). A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: Identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Academic Medicine, 82(11), 1040-1048. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3185761ee

Lynch, D. C., Surdyk, P. M., & Eiser, A. R. (2004). Assessing professionalism: A review of literature. Medical Teacher, 26(4), 366-373. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001696434

McKimm, J., Vogan, C., & Mannion, H. (2017). Implicit leadership theories and followership informs understanding of doctors’ professional identity formation: A new model. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 2(2), 18-23. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2017-2-2/oa1022

Mueller, P. S. (2009). Incorporating professionalism into medical education: The Mayo clinic experience. The Keio Journal of Medicine, 58(3), 133-143. https://doi.org/10.2302/kjm.58.133

Mueller, P. S. (2015). Teaching and assessing professionalism in medical learners and practicing physicians. Ramban Maimonides Medical Journal, 6(2), e0011. https://doi.org/10.5041/rmmj.10195

O’Sullivan, H., van Mook, W., Fewtrell, R., & Wass, V. (2012). Integrating professionalism into the curriculum. Medical Teacher, 34(2), 155-157. https://doi.org/10/3109/0142159x.2011.595600

Parker, M., Luke, H., Zhang, J., Wilkinson, D., Peterson, R., & Ozolins, I. (2008). The pyramid of professionalism: Seven years of experience with an integrated program of teaching, developing, and assessing professionalism among medical students. Academic Medicine, 83(8), 733–741. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31817ec5e4

Passi, V., Doug, M., Peile, E., Thistlewaite, J., & Johnson, N. (2010). Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Education, 1, 19-29. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4bda.ca2a

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2008). Bioethics core curriculum. Syllabus section 1: Ethics education programme. UNESCO. http://www.unesco-chair-bioethics.org/?mbt_book=bioethics-core-curriculum

Viggiano, T. R., Pawlina, W., Lindor, K. D., Olsen, K. D., & Cortese, D. A. (2007). Putting the needs of the patient first: Mayo clinic’s core value, institutional culture, and professionalism covenant. Academic Medicine, 82(11), 1089-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181575dcd

Williams, J. R. (2015). Medical ethics manual (3rd ed.). World Medical Association. https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/education/medical-ethics-manual/

*Maria Isabel Maniego Atienza

San Beda University

College of Medicine,

Mendiola Street,

City of Manila,

Philippines 1005

Tel: 6329178668751

Email: mmatienza@sanbeda.edu.ph

Submitted: 23 July 2020

Accepted: 21 October 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 121-123

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/CS2361

Sandra E Carr, Katrine Nehyba & Bríd Phillips

Division of Health Professions Education, School of Allied Health, The University of Western Australia, Australia

I. INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 has caused a major disruption to medical education with many educators making rapid shifts to online teaching (Sandars et al., 2020). Many have had to make critical changes in their instructional delivery (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020; Perkins et al., 2020). These changes may have lasting effects on the shape of educational delivery impacting generations to come (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020). It is important to share these changes and innovations as “Students and educators can help document and analyse the effects of current changes to learn and apply new principles and practices to the future” (Rose, 2020, p. 2132). Our case study examined the transition of small group teaching from blended learning to an emergency remote teaching environment.

II. CONTEXT

At the University of Western Australia, medical students undertake a scholarly activity during the third and final years of their Doctor of Medicine that enables specialisations in research or coursework. Of these students, 27% (n=65) choose a specialisation in Medical Education and graduate having completed 75% of a graduate certificate in health professions education. The first unit, Principles of Teaching and Learning offers an introduction to educational theory, curriculum design, teaching and assessment with a focus on developing teaching skills in small and large group settings and applies blended learning strategies. The final assignment assesses small group teaching techniques and the application of peer assisted learning and feedback. This group assignment requires students to:

a. Develop, plan and deliver a face to face small group teaching activity.

b. Describe and assess the group work processes using an audio journal and group assessment rating.

c. Engage in Peer Observation of Teaching.

With the advent of COVID-19 a change in the assessment was required. The 65 students were informed that the group work would have to occur on line and the small group teaching activity would now be an online Video Presentation. Within the Blackboard learning management system, each group had access to a Discussion Board and a virtual meeting tool to support collaboration and teamwork. The marking rubric was not adjusted so the focus on application of small group teaching techniques remained. The video of the developed small group teaching activity was uploaded along with the audio journal and peer observation of teaching components of the assessment.

III. STUDENT EXPERIENCE

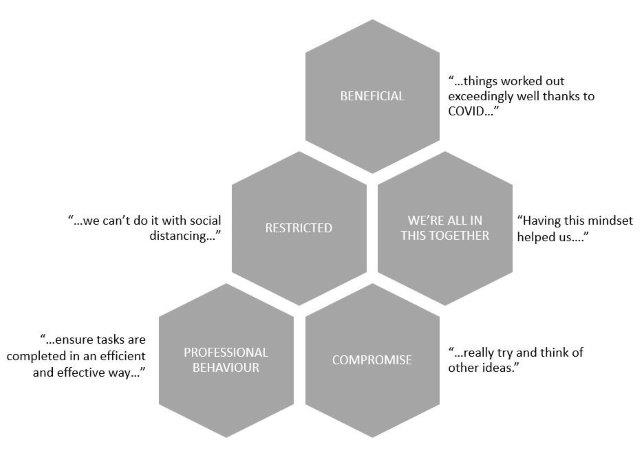

We undertook a thematic analysis of students’ audio journals and written responses to describe their experience in five broad themes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Student experiences of an online group assignment

Thirty percent of students reported aspects of working online as beneficial, and in some ways an improvement on face-to-face contact. For example, students who otherwise could have experienced difficulty meeting in person were able communicate and meet more easily:

“…we have already managed to organise our first meeting quite swiftly and with ease…”

(S1)

They also reported learning new skills:

“This group project taught me valuable skills when working in an online environment, including how to utilise and contribute in video meetings, share resources and regularly update the group…”

(S25)

“I have also learnt that filming or video is a great medium to communicate messages…once it is done, it can be a very effective tool.”

(S5)

However, not unexpectedly, some of the changes were seen as restrictions. The students talked of being “…banned from entering the hospital…” and of “…having no access…” to equipment or rooms, and “…we can’t do it with social distancing…” This led to feelings of disappointment and frustration, as they tried to find feasible options for the assignment.

“…all four of us were trying to actively brainstorm for an hour, trying to think of something…”

(S60)

“…we had fantastic plans…but unfortunately we didn’t have any of these options…”

(S25)

The perceived restrictions challenged the students’ persistence and adaptability (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020) and led them to compromise. One student, after their group changed their assignment idea from venepuncture to handwashing, said “…we…decided to try and make this idea work the best we could.” (S18). This adjustment and negotiation of ideas led to some innovative and varied submissions, using, for example, dolls; online role-plays; on-screen debate and custom virtual backgrounds.

Another theme that emerged was that of a shared experience, and a sense of we’re all in this together. The use of online communication platforms such as Zoom and Facebook Chat, and the use of shared documents meant that “…everyone could be involved, regardless…” There was evidence of a supportive environment and shared accountability, to ensure that they were “…giving everyone a chance…” and “…everyone seemed equally invested…”

Finally, despite the changes, restrictions and compromise, the students remained task-focussed and were able to plan, allocate, collaborate and communicate in their new online environment. The spread of grades for this assignment was consistent with previous cohorts, suggesting that the change in method was not detrimental to their performance. They were aware of potential dangers of working in this new, unknown way.

“…it will be important for us to be mindful of the risk of losing a professional mindset during our meetings, and divert away from the task at hand.”

(S1)

However, they described the same professional behaviours that would be expected in a face-to-face assignment, such as planning; delegation; effective communication; setting and meeting deadlines; and providing constructive feedback to other team members.

“…our team worked really well together. I suspect things worked out exceedingly well thanks to COVID and lockdown, which forced us to work online.”

(S8)

IV. CONCLUSION

Sklar states that during these unprecedented times “…it is important that our voices are loud about what we have experienced and learned” (Sklar, 2020, p. 9). In this case study we have described an experience of emergency remote teaching, in which a face-to-face small group teaching assignment was moved online. Our experience suggests that, even with its challenges, it was a success. Despite restrictions and compromise the students reported beneficial aspects to working online, and demonstrated a sense of comradery and professionalism while developing digital learning skills that are proving essential for learners and applicable for health professionals in the 21st century.

Notes on Contributors

Sandra Carr conceived the idea of the case study and contributed to the design of the work, gathered the qualitative data and interpretation of the findings. Katrine Nehyba contributed to the design of the case study, searched the supporting and relevant literature, undertook the thematic analysis of the data and constructed the Figure. Bríd Phillips contributed to the design of the work, searched the supporting and relevant literature to construct the rationale and introduction and contributed to the interpretation of the findings. All contributed to confirmation of the themes, the Discussion and Conclusion. All reviewed and contributed to each draft of the paper and approval the final submission.

Acknowledgement

This project was subject to ethical approval by the human ethics committee of the University of Western Australia. Consent was waived in line with the ethical approval obtained.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Ferrel, M., & Ryan, J. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Curēus, 12(3), e7492–e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Perkins, A., Kelly, S., Dumbleton, H., & Whitfield, S. (2020). Pandemic pupils: COVID-19 and the impact on student paramedics. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 17(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.17.811

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(21), 2131–2132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Sandars, J., Correia, R., Dankbaar, M., de Jong, P., Goh, P., Hege, I., Masters, K., Oh, S., Patel, R., Premkumar, K., Webb, A., & Pusic, M. (2020). Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

Sklar, D. (2020). COVID-19: Lessons from the disaster that can improve health professions education. Academic Medicine, 95(11), 1631–1633. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003547

*Sandra Carr

Division of Health Professions Education

The University of Western Australia

35 Stirling Hwy,

Crawley WA 6009, Australia

Tel: +61 64886892

Email: Sandra.carr@uwa.edu.au

Submitted: 20 July 2020

Accepted: 6 November 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 14-23

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/RA2346

Claude Jeffrey Renaud1, Zhi Xiong Chen2,6, Heng-Wai Yuen3, Lay Ling Tan4, Terry Ling Te Pan5 & Dujeepa D. Samarasekera6

1Department of Medicine, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore; 2Department of Physiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Changi General Hospital, Singapore; 4Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore; 5Department of Anaesthesiology, National University Health System, Singapore; 6Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: The Coronavirus-19 pandemic has had profound effects on health professions education (HPE) posing serious challenges to the continued provision and implementation of undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing medical education (CME). Across these HPE domains, the major disruptions included the exclusion of undergraduate learners from clinical learning environments, restricted intra-, inter-institutional and overseas movement of medical professionals, termination of face-to-face learner-educator interactions, deployment of postgraduate learners into non-scope service settings, and CME postponement.

Methods: In this review we report on how in Singapore various adaptive measures were instituted across the 3 HPE domains at institutional and national level to maintain adequate resources at the frontline to meet service exigencies, promote healthcare professionals’ wellbeing and safety as well as mitigate the spread of the pandemic.

Results: We identified several strategies and contingencies developed to address these challenges. These involved the use of online learning platforms, distributed and asynchronous learning, an undergraduate Pathway Programme, and use of innovative hands-on technology like simulation. Robust, well pre-planned pandemic preparedness, effective communication, as well as provision of psychological support resources ensured maintenance of service and academic continuity, trust and resilience within HPE. However, several challenges remain, namely the timing and manner of conducting formative and summative assessments, cybersecurity, and the indispensable hands-on, in-person experiential learning for surgical training.

Conclusion: Strong leadership with vision and planning, good communication, prioritising learners’ and educators’ wellbeing and safety, and harnessing existing and emerging online learning technologies are crucial elements for effective contingencies for HPE disruption during pandemics.

Keywords: Pandemic Preparedness, COVID-19, Curriculum Development, Online Learning and Assessment, Learner Wellbeing and Safety, Health Profession Education

Practice Highlights

- COVID-19 pandemic has caused profound disruption to medical education and Singapore is no exception.

- Health professions education community (undergraduate, residency and continuous professional development) had to rethink traditional learning approaches.

- There is a need for contingencies that integrate service and academic continuity and safety.

- Implementing contingencies requires coordinated national and institutional pandemic pre-preparedness.

- There remain uncertainties as to the long-term effectiveness of these contingencies on learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

Singapore had its first case of Coronavirus 19 (COVID-19) on 23rd January 2020 and scaled up its response from DORSCON (Disease Outbreak Response System Condition) Yellow to Orange 2 weeks later as the crisis evolved to pandemic proportion (Ashokka et al., 2020; J.E.L. Wong et al., 2020). This involved setting up a suite of strategies aimed at containing community transmission (Lee et al., 2020).

At the healthcare service and health profession education (HPE) level, these strategies centred on mobilising adequate resources at the frontline, mandating use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in high-risk areas and restricting healthcare workers’ movement (Ashokka et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; C. Wong et al., 2020; J.E.L. Wong et al., 2020). In addition, undergraduate medical education put a stop to clinical clerkships and large and small on-campus learning and restructured formative and summative assessments.

As the very stakeholders and resources required for HPE were diverted to fighting the pandemic, HPE faced extraordinary disruption. Educators and learners had to delicately balance service continuity, patients’ and learners’ wellbeing and safety versus maintaining a business-as-usual approach to learning. Moreso, the entire HPE community had to critically relook at the applicability of competency-based learning which is traditionally predicated on the principles of authentic supervised patient experience, programmatic assessment, learners as part of a community of practice and continuous professional development (CPD) (Harris et al., 2010; Iobst et al., 2010).

Previous public health emergencies like Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) have taught that such disruptions can provide unique opportunities for contingency planning in HPE especially when there is little time for wholesale programme redesign (Lim et al., 2009; Patil & Yan, 2003). This report thus describes the experience of 3 HPE domains in Singapore in mitigating the dissonance between optimal pandemic preparedness, unconstrained academic continuity and learners’ and educators’ well-being.

II. METHODS

A comprehensive review of the adaptive contingency strategies adopted at 1 undergraduate (Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine), Singapore residency programmes and across the CPD was made by looking at institutional and governmental programmes during the early phase of the pandemic and prevalent COVID-19 related literature on HPE. As this research is a description of events that have already happened and did not involve HPE stakeholders’ directly and interventionally, participants’ informed consent and internal review board approval were not required for its conduct.

III. RESULTS

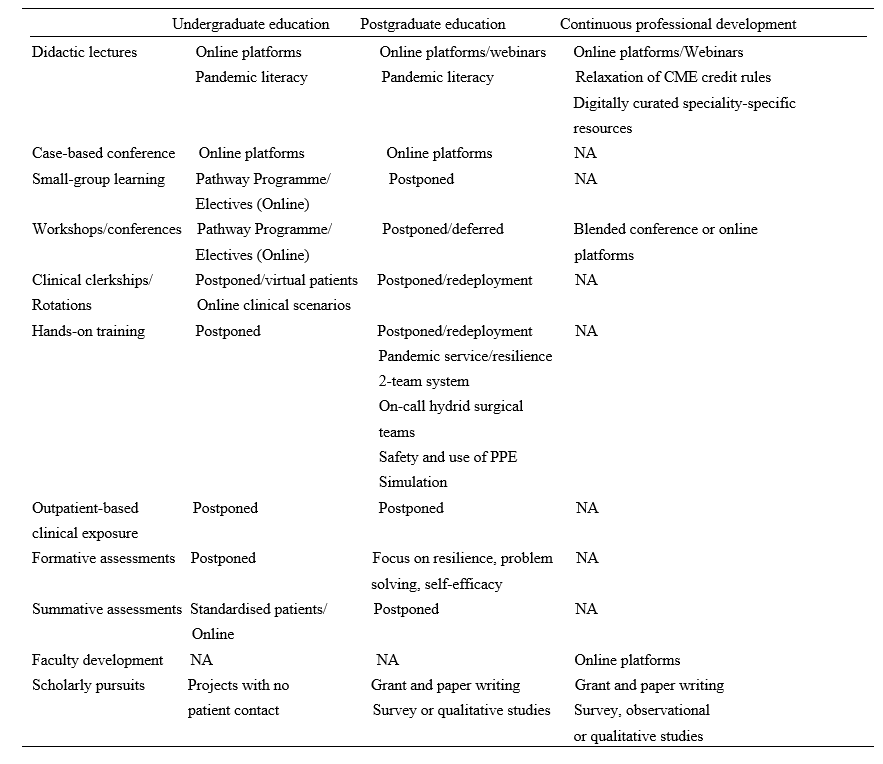

Herein, is a detailed outline of the contingencies implemented across the 3 HPE domains which are also summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of disruptions and contingences across the health profession education spectrum during COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore.

Note: NA=not applicable; PPE= personal protective equipment

A. Contingencies in Undergraduate Medical Education: Experience of Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

At the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine which is the largest of the three medical schools in Singapore, the Education Team led by the Vice Dean (Education) started preparing in February 2020 for the possibility of loss of clinical teaching. Those most affected would be Phase 3 and 4 (Year 3 and 4) medical students. Phase 5 (Year 5) students were preparing for their Final Professional Examinations even though assessment was significantly disrupted across all Phases. Phase 1 and 2 (Year 1 and 2) students have relatively less clinical learning exposure and assessments, and were finishing their curricula and preparing for exams. Focusing on the Phase 3 and 4 students, first, their vacation and elective periods were brought forward respectively. Next, to give students meaningful learning opportunities that do not require patient contact, the Pathway Programme which had been launched before the pandemic was paced up (National University Singapore, Yong Yoo Lin School of Medicine, 2020).

The Pathway Programme consists of six Pathways. They are Health and Humanity, Health Informatics, Inquiry and Thinking, Medical Education and Medical Innovation and Entrepreneurship all led by a team of trained educationists. In addition, a non-Pathway initiative called Education Innovation completed the suite of new education offerings for the students. The sixth Pathway Behavioural and Implementation Science was partially offered under Inquiry and Thinking through a series of lectures on Health Economics. Below we describe what each Pathway is about.

1) Behavioral and implementation science: This pathway exposes medical students to principles of behavioural and implementation science, and applies this knowledge to effectively design and deliver healthcare in real-world settings, and lays the foundation for them to become active agents of change in clinical practice.

2) Health and humanity: This pathway aims to nurture emotionally resilient, socially conscious and globally minded health leaders through rekindling one’s love for medicine and humanity. Through experiential activities, inspirational workshops and hands-on project work in the community, students develop critical thinking skills in global health, teamwork and leadership skills to inspire health for all.

3) Health informatics: This pathway aims to enable students to gather and critically evaluate research and health informatics data, equipping them with the skills necessary to apply the principles of health informatics, summarise and visualise datasets to perform basic analyses, so they become data-science competent clinicians who can identify and analyse medical data to address clinical issues.

4) Inquiry and thinking: This pathway aims to inspire and motivate our medical students to develop a sense of curiosity so as to foster a habit of inquiry that is able to dynamically utilise a range of thinking methods, processes and skillsets to tackle questions and problems. The end goal of this pathway is to groom a pipeline of thinking doctors who can advance healthcare in any aspect they desire.

5) Medical education: This pathway exposes medical students to concepts and principles in HPE, to equip them with foundational skills in HPE, with a focus on educational innovation and scholarship of teaching and learning, so as to groom future clinical educators.

6) Medical innovation and entrepreneurship: This pathway aims to nurture medical students with the 6Cs attributes: Curiosity, Creativity, Compassion, Collegiality, Collaboration, and Commercial Intelligence. The programme gradually exposes medical students to concepts and principles in innovation, and the selective elements equip students with foundational skills in innovation and entrepreneurship.

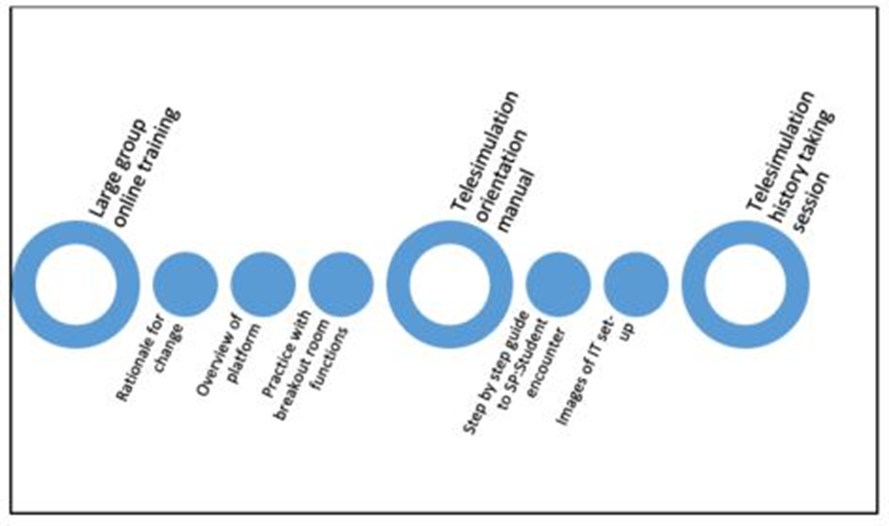

With the elective period brought forward, Phase 4 students were exposed to the Pathway Programme from early-March to early-May 2020 through two weeks of front-loading online lectures, followed by four to eight weeks of projects. Most Pathways followed the general structure with slight variations between them. For Phase 3 students, they enjoyed an early vacation before encountering a shortened Pathway Programme from early-April to early-May 2020, comprising of 2 weeks of front-loading online lectures and 2 weeks of projects, which students had the option of continuing into Phase 4.

Using Inquiry and Thinking Pathway as an example, topics of front-loading online lectures included ‘Complexity and Systems Thinking’, ‘Habits of Inquiry and Critical Thinking’ and ‘Evidence-based Medicine and Search Methods’. More than 80 projects were offered by prospective supervisors with more than 70 students getting involved in projects. Each student was guided in the project by the supervisor as well as engaged in a one to two-hour weekly reflection sessions with a separate mentor or the supervisor who doubled up as a mentor. Students were required to submit a weekly reflection write-up of 50 words or more. At the end of the Pathway Programme, students submitted a single slide of their projects for evaluation. Top two projects from each Pathway were selected to present and compete in a Grand Finale on 8 May 2020 before the School’s leadership, a panel of judges, their peers and overseas observers. The Grand Finale attracted over 200 participants. Single slides of all projects were compiled into an e-book to be shared with students and faculty members.

B. Postgraduate Training: Experience of Residency Programmes across Singapore Three Sponsoring Institutions (SIs)

Since SARS, Singapore has steadily been bolstering critical resource reserves and expertise in pandemic preparedness, culminating in the setup of the 330-bed purpose-built National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID) at the National Healthcare Group (NHG) Novena campus (Lee et al., 2020; Seah, 2020). Concurrently, postgraduate medical education underwent significant transformation with the adoption of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) styled competency-based learning, culminating in the setup of three residency SIs of which NHG is one (Huggan et al., 2012; Khoo et al., 2014). Thus during the build-up to COVID-19 pandemic, NCID, residents and faculty at NHG 27 residency programmes formed the initial frontliners in managing the pandemic before being later joined by the other two SIs (C. Wong et al., 2020).

Care delivery and learning had to be restructured so that adequate manpower could be redeployed at screening centres, emergency departments, outbreak wards and critical care units. Frontline residents had to endure long and exhausting shifts wearing PPEs and prolonged time away from family, not to mention postponed leaves. Residents and faculty also had to be segregated into independent two-team system with phased two-weekly rotations to avoid manpower attrition and service disruption as a result of staff infection, quarantine or burnout. Elective surgeries, continuity clinics, grand rounds, face-to-face case conferences, cross-institutional elective rotations, in-person programme selection interviews as well as summative assessment had to be deferred. Postgraduate specialty conferences, courses and workshops, whether local or international, also had to be postponed or cancelled due to travel restrictions, further limiting opportunities for learning.

As a result of these changes several resourceful strategies were implemented to balance the palpable tensions between service, wellbeing and learning.

The first was maintaining open and transparent communication between institutional and academic leaders, faculty and residents so that the rationale for a pandemic-mode centralised command-control leadership model could be accepted. This allowed residents to grasp the real sense of urgency brought in by COVID-19, thus facilitating speedier buy-in and compliance to ever changing human resource and education policies. In addition, this strategy helped build up trust in the institutional support structure and contain the spread of parallel distracting infodemics, allowing residents to focus on service delivery, learning and well-being.

The second strategy was the promotion of residents’ physical and psychological safety and wellbeing. This entailed ensuring all residents had adequate orientation to the proper use of PPEs and could easily access them. Well-being and resilience support resources like in-person or anonymous virtual outreach psychological crisis intervention counselling and peer support through online debriefing and feedback were put in place across all hospitals under the three SIs. The ancillary effect was that residents felt their safety, their families’ and patients’ was valued and that there was fair and equitable work and rest allocation. Further, ACGME cancelled all accreditation and Clinical Learning Environment Review site visits and took steps to reframe and relax some accreditation criteria (Nasca, 2020). This went a long way in allaying residents’ anxieties regarding clinical progression.

The third strategy was leveraging existing online tools to maintain some element of learning continuity without the need to invest in significantly expensive technologies, curricular redesign or faculty re-development. Programmes transferred their core didactic lectures, journal clubs and case-based discussions onto distributed learning platforms such as Zoom, Go to meeting, Google meet or WebEx for synchronous learning. Access to Webinars had the added advantage of providing opportunities for asynchronous learning. Zoom teleconferencing in particular, remains the most popular due to its affordable subscription, large participant capacity and easier accessible collaborative interface and a breakout feature that enables mounting learning models like team-based learning.

Residents from surgical residency programmes who rely on direct-patient encounter and hands-on experience for learning were more significantly impacted. Importantly, because non-emergency visits to hospitals were halted, elective procedures and surgeries were postponed or cancelled and, the number of patients and learning opportunities was thus greatly reduced. This was further aggravated by the shift of many training institutions and teaching hospitals to pandemic service (Liang et al., 2020). In many instances, surgical residents were redeployed to frontline areas, like screening centres, which are beyond their usual scope of practice (C. Wong et al., 2020).

Curriculum development contingencies thus went beyond online didactic content dissemination to embrace enhanced distributed learning approaches like videos, podcasts, virtual reality and simulated learning (C. Wong et al., 2020). Some programmes improvised by forming on-call hybrid surgical teams, which allowed surgical residents some measure of hands-on exposure to generic emergency or semi-elective cases during on calls but not necessarily within the scope of their area of interest.

C. Contingencies for Continuous Professional Development (CPD)

The disruption brought on by closure of higher educational institutions, scaling down of healthcare organisations and travel restrictions, compelled educators and health care professionals to adapt and embrace curricular changes and transition to virtual learning and use of technology for simulated learning.

Continuing medical education (CME) and CPD are integral parts of the development of a healthcare professional in providing optimal clinical care for his/her patient. CME is aimed at maintaining or updating the requisite knowledge, skills, professional performance and relationships and crucially, is a requirement for maintenance of certification in the discipline or specialty of the healthcare profession (Davis et al., 2008). CPD on the other hand caters to a broader range of competencies that reflect the healthcare profession attitudes towards learning and learning needs (Filipe et al., 2018). Every specialty and governing medical body has its stipulated requirements. In Singapore, the Singapore Medical Council (SMC) states that all fully and conditionally registered doctors are required to meet the compulsory CME requirements of 50 core points for the qualifying period before their practising certificate can be renewed (Singapore Medical Council, 2020a). While most CME activities involve attendance at local, regional or international scientific meetings or conferences, self-study, review and authorship of articles are also considered core CME points. Most hospitals hold regular Grand Ward Rounds, journal clubs and peer review learning sessions at departmental and institutional levels, which also contribute towards core CME points.

However, with Singapore moving to DORSCON Orange, many of these learning activities were immediately suspended as staff scrambled to reorganise clinical services amidst the pandemic imperative for team separation and safe distancing. Thus, traditional face-to-face meetings were replaced by online meetings and webinars facilitated by virtual platforms mentioned previously. In tandem the SMC relaxed requirements for CME credits by allowing healthcare professionals to log in attendance to online sessions, including webinars (Singapore Medical Council, 2020b). There was also an increase in allocation of CME credits for self-study (e.g., reading of referenced journals listed in PubMed). COVID-19-related CME activities were also considered core points for all doctors (Singapore Medical Council, 2020b).

While, much of the recent global CME content has primarily focused on increasing understanding of COVID-19 and its infectious nature across various medical disciplines, there has been lesser emphasis on its medical and psychological impact to health. It has nonetheless enabled healthcare professionals to better provide optimal care for patients while adopting best available evidenced practice relating to all aspects of this rapidly contagious disease. Thus, online information dissemination has been at an unprecedented high with multiple local, regional and international webinars and resource websites being made readily accessible. Professional societies have also made available to their members regularly curated digital speciality-specific resources on best practices pertaining to COVID-19 management (Academy of Medicine Singapore, 2020).

In addition to CME, healthcare professionals have traditionally relied on annual live face-to-face local, regional and international scientific conferences, symposiums, and educational workshops to network as a learning community and keep abreast of domain-specific advances. With strict travel restrictions these have been cancelled, postponed or moved online as webinars, interactive content, forums and chats.

Some conference organisers decided to still proceed to issue notices of acceptance of abstract submissions as ‘proof’ of scholarly work or allowed online presentation. Other creative ways of continuing with international conferences have included a “blended conference” approach with a mix of face-to-face and online content to support those attending onsite and online (Nadarajah et al., 2020). With careful attention paid to safe distancing for onsite participants, such “blended conferences” provide the all-important human face-to-face interactions which online webinars and conferences, though functional in most parts, sorely lack. They also provide the best of both worlds and may indeed be the new normal in the foreseeable future as COVID-19 further changes the HPE landscape relating to international travel and social interaction.

Similarly, Singapore’s three medical school curriculum development centres rapidly transited in-person to virtual faculty development sessions. This allowed educators openly dispersed by social distancing and clinical exigencies to continue tapping on the best pedagogic practices, interact and engage in interprofessional learning.

IV. DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic disruptions have reinforced the need for agency and adaptation in HPE. We have shown that through well-coordinated, multisectoral efforts, solutions can be harnessed to minimise their negative impact on learning. However COVID-19, unlike other recent coronavirus epidemics like SARS and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) seems a more formidable crisis (Jones, 2020; Peeri et al., 2020). It may not go away quickly without the advent of effective vaccines and sustained infection control measures. These contingencies are therefore aimed at promoting service and academic continuity, safety and resilience. Whilst they are useful blueprints for pandemic preparedness and responsiveness in the short term, they may not be applicable in all contexts or in a crisis of attrition. Further, they have their own strengths and limitations.

A major strength is institutional and academic leaders’ sense of long-term planning and commitment to educators’ and learners’ safety through effective communication, being visible and providing programme and system support. In a rapidly evolving disruptive environment, this is crucial, as stakeholders remain engaged and trusting without having to anguish over under-resourcing or abandonment. Recent publications have alluded to the social capital returns of such an “integrative resilience approach” that amplifies individual and system wellbeing and minimises burn-out and contagion (Neufeld & Malin, 2020; Samarasekera et al., 2020; Schwartz et al., 2020; Wald, 2020).

Another strength is the adoption of adaptive online technologies which not only ensures academic continuity but also allows a smooth and rapid quarantine and pandemic curriculum development. Large virtual communities of learners can thus be rapidly mobilised without fundamentally affecting content, quality and institutional bottom lines. Indeed, this may have had the unintended consequences of unprecedentedly boosting attendance rates in medical schools, residency programmes and CPD sessions. Online migration also facilitates quick and mass standardised training and deployment of untrained or returning retired healthcare professionals in general and critical care medicine, allowing healthcare institutions to boost capacity in those critical areas during pandemics (Brunner et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). More so, these emergent technologies hold a lot of promise for post-pandemic medical education and replication of authentic patient experiences. It is envisioned that they can be interfaced onto learning management systems (LMS) and into areas like virtual patient consults, telemedicine, adaptive learning and extended reality or avatar-like high fidelity simulation (Goh & Sandars, 2020). They are also important as a source of asynchronous learning whereby learners who are too busy with clinical duties or for surgical residents when there is a lack of critical hands- on training (Tolu et al., 2020).

A third strength, is that such crisis can open unintended opportunities for learners to develop competencies outside the core curricular knowledge and procedural skills sphere. For instance, the mere exposure of undergraduate learners not directly involved in patient care to pandemic-related content, volunteering in contact tracing or public awareness centres or restructuring of learning experiences like the Pathway Programme can nurture professional identity, pandemic literacy and doctor-ready qualities like service prioritisation, altruism and resilience (Bauchner & Sharfstein, 2020; Rose, 2020; Stetson et al., 2020). Indeed, the Pathway Programme succeeded in meaningfully engaging medical students at a time when clinical teaching and clinical elective opportunities were frozen. It gave time for the medical school to work out a safe and calibrated approach to resume clinical training in consultation with the relevant government bodies. The fact that it was conceptualised pre-pandemic demonstrates an extraordinary sense of prescience by the academic leadership. The advent of COVID-19 served to accelerate its implementation. It thus not only helped undergraduate medical education to cope with the pandemic but enrich the medical curriculum by catering to the diverse strengths and interests of each learner in order to nurture future-ready doctors for a post-COVID world.

As to residents’ learning, negotiating challenging pandemic duty rosters, making personal choices and sacrifices, navigating processes like resource allocation and public health measures and being deployed into non-core areas, can be just-in-time learning platforms for more nuanced ACGME competencies like professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, system-based practice and practice-based learning (Hall et al., 2020; Nasca, 2020; Schwartz et al., 2020; Tolu et al., 2020; C. Wong et al., 2020). For surgical residents, there is also an added learning and safety benefit when hitherto straightforward surgical procedures like tracheostomy suddenly come with a myriad of precautions, criteria, and protocols (Givi et al., 2020). Clinic and elective surgery postponement can provide ample opportunities for self-directed learning, exit exams preparation and scholarly pursuits like grant, research ventures and quality improvement projects writing (Schwartz et al., 2020; Tolu et al., 2020). Additionally, prioritisation of public health emergency response training across the HPE spectrum can render healthcare institutions better prepared at handling future pandemics and burn-out (Yang et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, these contingencies have a number of limitations. Namely, moving medical education from the bedside to the ‘web-side’ cannot replace the real patient-centred clinical experience and case-mix learners derive from ward rounds, grand rounds and continuity clinics. Even the Pathway Programme was not without its challenges. With Singapore entering into Circuit Breaker phase of DORSCON Orange on 3rd April 2020, some projects were disrupted as access and movement became more limited (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2020).

Secondly, the utility of online learning is very much predicated on the vagaries of internet penetration and connectivity which makes this approach not always transferable to all socio-economic contexts (Cecilio-Fernandes et al., 2020). More so, for surgical residents, online learning or high-fidelity simulation cannot substitute for in-person learning. The technical skills, haptic feedback, the realism of live surgery, the experiential and contextual learning of ‘being there’ in a surgical team, and the non-cognitive domain skills like collaboration and resilience can be hard to simulate. Reduced contact time between residents and faculty also impacts adversely on opportunities for mentoring, role modelling and supervision. There is also always a danger of breaching learning principles such as cognitive overload when online content design is outside the hands of curriculum developers and programme directors (Kachra & Ma, 2020). As to health professionals, most of these online CME resources represent rather an amalgam of available information that may not have been well curated and pre-approved by accreditation organisations for relevancy.

Thirdly, the contingencies fail to address the enormous challenges in conducting clinical workplace-based assessments, without compromising their validity, reliability, defensibility and educational impact. Although high-stakes OSCE can be successfully conducted in a pandemic environment, its implementation comes with tremendous logistical and political manoeuvring to ensure students’, examiners’ and patients’ safety and assessment integrity are preserved (Boursicot et al., 2020). Cancelling both formative and summative assessments can delay learners’ progression or completion unless adjustments are made to previously established competency criteria. Undergraduates may fail to graduate on time to join the vital pool of medical workforce and residents may not be able to practise as independent practitioners. This can create anxiety and concern to both learners and educators about how to catch up post-pandemic with piling assessment and case and portfolio backlogs.

Lastly, reliance on third party software entities for online content dissemination contrary to institution-designed LMS or whole-sale programme information technology infrastructure redesign carries cybersecurity, privacy and data ownership risks (Fawns et al., 2020; Sandars et al., 2020). Not all faculty are tech savvy to handle the technical intricacies and the many options in the market. Predatory providers may thus seek to peddle behaviourist tactics onto users for their own corporate gains.

V. CONCLUSION

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major threat to HPE in Singapore but it has also created opportunities for adaptive and flexible contingencies so that learning goes on safely with minimum constraints. While there is a need to celebrate these early successes, it is also imperative that we assess and learn from their limitations so that we can further refine and more successfully, collaboratively and iteratively apply them in a prolonged crisis. Furthermore, these experiences can serve as templates for adaptive and value-added learning at both regional and international HPE settings beset by larger service and academic disruption. But most importantly they foreshadow the resilience, reimagining and resourcefulness that are expected of HPE as it transits from the new normal of pandemic crisis management to the post-pandemic next normal of innovative technology-based learning.

Notes on Contributors

Adj Associate Professor Claude J Renaud is a senior consultant nephrologist at Khoo Teck Puat hospital Singapre and Associate Programme Director at the National Healthcare Group Renal Residency Programme. He conceptualised, drafted and revised article and wrote introduction, postgraduate medical education (PGME), discussion and conclusion sections.

Dr Zhi Xiong Chen is a Senior Lecturer in Physiology and Assistant Dean for Education at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. He conceptualised article and wrote the undergraduate medical education section.

Adj Associate Professor Heng Wai Yuen is senior consultant in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Changi General Hospital, Singapore and Campus Director, SingHealth Duke-NUS Institute for Medical Simulation (SIMS). He wrote abstract and post graduate medical education sections and revised article.

Adj Associate Professor Tan Lay Ling is senior consultant in the Department of Psychological Medicine, Psychogeriatric Service, at Changi General Hospital (CGH). She wrote the section on continuous professional development and revised article overall.

Dr Terry Ling Te Pan is a Senior Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia, National University Hospital and Advisor, Education Technology Unit, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. He co-wrote the section on continuous professional development and revised article overall.

Dr Dujeepa D. Samarasekera, director at Centre for Medical Education (CenMED) Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. conceptualised and revised article.

Ethical Approval

This study is a description of events and practices and therefore did not require approval from institutional review boards.

Funding

There is no external funding involved in this study.

Declaration of Interest

Other than Dr Dujeepa D Samarasekera who is Editor of TAPS, all authors have no conflict of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

References

Academy of Medicine Singapore (AMS) (2020, June 2). Resource site on COVID-19. https://www.ams.edu.sg/policy-advocacy/covid-19-resource-page

Ashokka, B., Ong, S. Y., Tay, K. H., Loh, N. H. W., Gee, C. F., & Samarasekera, D. D. (2020). Coordinated responses of academic medical centres to pandemics: Sustaining medical education during COVID-19. Medical Teacher, 42(7), 717-720. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1757634

Bauchner, H., & Sharfstein, J. (2020). A bold response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Medical students, national service, and public health. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(18), 1790-1791, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6166

Boursicot, K., Kemp, S., Ong, T. H., Wijaya, L., Goh, S. H., Freeman, K., & Curran, I. (2020). Conducting a high-stakes OSCE in a COVID-19 environment. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000054.1

Brunner, M., Vogelman, B., & Smith, J. (2020). Rapid development of an outpatient‐to‐inpatient crash curriculum for COVID providers. Medical Education. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14244

Cecilio-Fernandes, D., Parisi, M. C. R., Santos, T. M., & Sandars, J. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and the challenge of using technology for medical education in low and middle income countries. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000074.1

Davis, N., Davis, D., & Bloch, R. (2008). Continuing medical education: AMEE education guide No 35. Medical Teacher, 30(7), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802108323

Fawns, T., Jones, D., & Aitken, G. (2020). Challenging assumptions about “moving online” in response to COVID-19, and some practical advice. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000083.1

Filipe, H. P., Golnik, K. C., & Mack, H. G. (2018). CPD? What happened to CME? CME and beyond. Medical Teacher, 40(9), 914–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1471200

Givi, B., Schiff, B. A., Chinn, S. B., Clayburgh, D., Iyer, N. G., Jalisi, S., Moore, M. G., Nathan, C. A., Orloff, L. A., O’Neill, J. P., Parker, N., Zender, C., Morris, L., & Davies, L. (2020). Safety Recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of the American Medical Association Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, 146(6),579-584. https://doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780

Goh, P. S., & Sandars, J. (2020). A vision of the use of technology in medical education after the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000049.1

Hall, A. K., Nousiainen, M. T., Campisi, P., Dagnone, J. D., Frank, J. R., Kroeker, K. I., Brzezina, S., Purdy, E., & Oswald, A. (2020). Training disrupted: Practical tips for supporting competency-based medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical Teacher, 42(7), 756-761. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1766669

Harris, P., Snell, L., Talbot, M., & Harden, R. M. (2010). Competency-based medical education: Implications for undergraduate programs. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 646–650. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500703

Huggan, P. J., Samarasekara, D. D., Archuleta, S., Khoo, S. M., Sim, J. H. J., Sin, C. S. P., & Ooi, S. B. S. (2012). The successful, rapid transition to a new model of graduate medical education in Singapore: Academic Medicine, 87(9), 1268–1273. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182621aec

Iobst, W. F., Sherbino, J., Cate, O. T., Richardson, D. L., Dath, D., Swing, S. R., Harris, P., Mungroo, R., Holmboe, E. S., & Frank, J. R. (2010). Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500709

Jones, D. S. (2020). History in a crisis—Lessons for Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(18), 1681–1683. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2004361