Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study

Submitted: 1 December 2020

Accepted: 5 April 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 49-64

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/OA2443

Yasushi Matsuyama1, Hitoaki Okazaki1, Kazuhiko Kotani2, Yoshikazu Asada3, Shizukiyo Ishikawa1, Adam Jon Lebowitz4, Jimmie Leppink5 & Cees van der Vleuten6

1Medical Education Center, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 2Center for Community Medicine, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 3Center for Information, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 4Department of General Education, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 5Hull York Medical School, University of York, United Kingdom; 6School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, The Netherlands

Abstract

Introduction: Previous studies indicate that professional identity formation (PIF), the formation of a self-identity with the internalised values and norms of professionalism, may influence self-regulated learning (SRL). However, it remains unclear whether a PIF-oriented intervention can improve SRL in clinical education. The aim of this study was to explore whether a PIF-oriented mentoring platform improves SRL in a clinical clerkship.

Methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted. Forty-one students in a community-based clinical clerkship (CBCC) used a PIF-oriented mentoring platform. They articulated the values and norms of professionalism in a professional identity essay, elaborated on future professional self-image, and reflected on their current compared to future selves. They made a study plan while referring to PIF-based self-reflection and completed it. The control group of 41 students completed CBCC without the PIF-oriented mentoring platform. Changes in SRL between the two groups were quantitatively compared using the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire. We explore how PIF elements in the platform affected SRL by qualitative analysis of questionnaire and interview data.

Results: A moderate improvement in intrinsic goal orientation (p = 0.005, ε2 = 0.096) and a mild improvement in critical thinking (p = 0.041, ε2 = 0.051) were observed in the PIF-oriented platform group. Qualitative analysis revealed that the PIF-oriented platform fostered professional responsibility as a key to expanding learning goals. Gaining authentic knowledge professionally fostered critical thinking, and students began to elaborate knowledge in line with professional task processes.

Conclusion: A PIF-oriented mentoring platform helped students improve SRL during a clinical clerkship.

Keywords: Self-Regulated Learning, Professional Identity Formation, Clinical Clerkship

Practice Highlights

- Encourage students to verbalise their future self-image as a medical professional.

- Encourage students to reflect on their current selves compared with their perceived future ones.

- Promote in-depth communication between students and role models to foster self-regulated learning.

- Train mentors to become professional role models as self-regulated learners.

I. INTRODUCTION

Rapid advances in clinical knowledge require medical professionals to update their knowledge autonomously throughout their practice. Self-regulation in life-long learning has therefore become an important competency, and competency-based undergraduate medical education has emphasised students’ self-regulated learning (SRL) (Berkhout et al., 2018; Brydges & Butler, 2012; Frank, 2005; Sandars & Cleary, 2011). SRL is defined as learners’ active participation in their own learning processes from metacognitive, motivational, and behavioural perspectives (Zimmerman, 1989). In undergraduate education, SRL has been related to academic achievements (Artino, Cleary et al., 2014; Artino, Dong et al., 2012; Song et al., 2011; Turan & Konan, 2012), clinical skills (Cleary & Sandars, 2011) and emotional management (van Nguyen et al., 2015).

Several reports have claimed that drastic changes in learning context, from structured learning in preclinical years to less-structured and complex learning in clinical clerkships, may be too challenging for students and lead to insufficient learning (Berkhout et al., 2015, 2018; Cho et al., 2017; van Houten-Schat et al., 2018). This question appears more serious in East Asian countries, including Japan, where strong teacher instruction in pre-university education and teacher-centred curricula are the norm (Iwata & Doi, 2017; Lam & Lam, 2009; Tagawa, 2008). In order to make the typically limited clinical clerkship period a fruitful learning opportunity, remediation for struggling students from the perspective of SRL might be important (Durning et al., 2011; van Houten-Schat et al., 2018).

Several reports have shown that individualised mentoring intervention is effective in fostering SRL in clinical practice. For example, Aho et al. (2015) found that mentor-assisted SRL for surgical habits of residents led to more frequent practice and improved skills compared to peers. In Stuart et al. (2005), individualised guidance on strategies and learning plans raised students’ awareness of the learning process. However, the educational interventions undertaken in this study will focus on another contextual characteristic that may facilitate SRL – Professional Identity Formation (PIF) – defined according to Cruess et al. (2014, p.1447) as “a representation of self, achieved in stages over time during which the characteristics, values, and norms of the medical profession are internalised”.

In response to advances in medical science and the increasingly diverse needs of society, “professional” attributes such as autonomy, self-regulation, and social responsibility have been emphasised, in addition to traditional moral and ethical education emphasising healer roles (Cruess & Cruess, 1997, 2019). Furthermore, formation of professional identity can result in individuals thinking, acting, and feeling like physicians (Cruess et al., 2014; Cruess & Cruess, 2019). During the formation of professional identity, medical students begin to perceive belonging to a professional community and increase attention to role models (Jarvis-Selinger et al., 2012; Kalet, Buckvar-Keltz, Harnik et al., 2017; Kalet, Buckvar-Keltz, Monson et al., 2018). Emulation of role models’ self-regulation in learning behaviour is also expected.

People are more likely to interpret difficult experiences as task important when an accessible identity feels congruent to the task (Oyserman et al., 2017). In the context of this study, growing professional identity as a ‘physician-to-be’ might strengthen the perceived importance of engaging in challenges during clinical clerkships, and in self-regulating learning behaviours. In addition, when physicians perceive their identity as professionals, they begin to view daily learning tasks as high-stakes, and to self-regulate learning behaviours as coping strategies (Matsuyama et al., 2018). Another study has suggested that an explicit future professional self-image in medical students leads to self-reflection, increased attention to learning strategies of professional role models, and diversification of learning strategies (Matsuyama et al., 2019). Given that PIF is associated with motivational states, self-reflection, and diversified learning strategies, SRL may be facilitated by introduction of a PIF-oriented intervention.

This study specifically focused on PIF as a facilitating factor for SRL, because previous studies have suggested possible benefits of PIF-oriented education even for East Asian medical students, who are generally considered to have less SRL due to influence of pre-university education, with its strong faculty instruction and in-university teacher-centred curricula (Matsuyama et al., 2018, 2019).

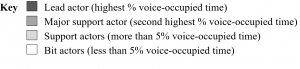

The purpose of this study was to examine whether SRL during clinical training can be fostered using a mentorship tool emphasising PIF, in addition to conventional mentorship by faculty members. In the pre- and post-clinical clerkship mentorship, students were asked to elaborate on their future self-image as professionals and compare their current and future selves to strengthen self-reflection under mentor support. Learners were aided in articulating their values and norms of medical professionalism by using the Professional Identity Essay (PIE) (Kalet, Buckvar-Keltz, Harnik et al., 2017; Kalet, Buckvar-Keltz, Monson et al., 2018), a self-administered questionnaire with 9 questions relevant to PIF. This encouraged mentors to understand the developmental stage of each learner’s professionalism and to provide individualised feedback on PIE and their future self-image. The feedback was also aimed at remediation for those whose self-images showed underdeveloped professionalism (low developmental stages in PIE). Study plans in the clinical clerkship were developed with reference to PIE-based self-images. We have named this platform ‘PIF-oriented mentoring platform for SRL (PIF-SRL)’. An overview of PIF-SRL is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the PIF-SRL and research data collection

This studied centred on two research questions:

- Does PIF-SRL improve SRL during the period around the clinical clerkship?

- If so, how does the PIF-oriented elements in PIF-SRL improve SRL?

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jichi Medical University (reference number: 19-001).

II. METHODS

A. Settings

1) Community-based clinical clerkship in Jichi Medical University: The mission of Jichi Medical University (JMU) is to educate students to become general practitioners competent in rural settings. Students are accepted per a quota system from each of Japan’s 47 prefectures. In the current curriculum at JMU, students complete lectures on almost every basic and clinical medicine area before the end of Year 3. From Year 4 to Year 6, students are permitted to participate in a clinical clerkship during which they receive training centred on taking patient histories and providing physical examination. Previously, most ward placements took place at the University’s affiliated hospital providing little opportunity for in-depth communication with role models in rural settings.

The community-based clinical clerkship (CBCC) was introduced in 1998 (Okayama & Kajii, 2011). For 2 weeks from late August to early September in Year 5, CBCC students stay at a community hospital or clinic in their home prefecture where JMU graduates work. Every year, two to five JMU graduates per prefecture are appointed to be CBCC mentors based on their motivation to teach in their prefectural communities. JMU faculty ensures the instructional quality of mentors by conducting annual face-to-face faculty development sessions. In addition, standards for learning activities are proposed, including ambulatory care, home care, hospital care, placement in mobile clinics, on-call work, rehabilitation, health education, health check-ups, vaccination, day services, and placement in welfare facilities (welfare institutions or nursing homes for the aged) (Okayama & Kajii, 2011).

Prior to the regular CBCC without PIF-SRL, students had several opportunities to communicate with mentors by telephone or e-mail. However, these communications did not provide sufficient opportunity for students to develop an image of future professionalism. We therefore felt that the communication framework in the regular CBCC did not fulfil its potential to stimulate PIF.

2) PIF-SRL for the CBCC: The PIF-SRL platform (Matsuyama et al., 2021) used an online communication platform, Google Forms. Before the CBCC began, mentors were briefed multiple times in writing and verbally on the purpose of the PIF-SRL to ensure their mentorship was PIF-oriented. They were also asked to read a manual which provided specific step-by-step responses from their first interaction with medical students on Google Forms in mid-July to their post-practice reflection in early to mid-September (Figure 1).

In the pre-clerkship phase, participants were asked to write their reflexive PIE. We used PIE because it is useful for helping learners articulate their own values and norms of medical professionalism, and for teachers providing feedback with rubrics based on Kegan’s constructive developmental theory (Kalet, Buckvar-Keltz, Harnik et al., 2017; Kalet, Buckvar-Keltz, Monson et al., 2018; Kegan, 1994). The present study used a Japanese version of the original English-language PIE form. Translation to Japanese was conducted by the main author (YM). To validate the translation accuracy, back-translation to English was conducted by a co-author (AJL), an American professor living in Japan who is literate in both English and Japanese. In accordance with in-depth talks based on PIE contents, students were encouraged to verbalise their future self-image and reflect on their current selves compared with their perceived future ones. The Question 6 of PART 2 in the PIF-SRL asked alumni mentors to describe their present self-image (Matsuyama et al., 2021). Students in PIF-SRL can also refer to this information when verbalising their future self-image.

Additionally, students in PIF-SRL were asked to create study plans for CBCC based on gaps between their current and future selves, and identify one or more learning goals. Referring to these plans, alumni mentors observed students and gave just-in-time feedback. Also, mentors provided students with learning strategies to help them overcome potential future challenges. Apart from these instructions, mentors were essentially independent in their education of the medical students. After the two-week clerkship, students were asked to re-articulate their own future image and received feedback from their mentors by Google Forms (Figure 1).

B. Subjects

First, PIF-SRL mentors were selected. In 2018 and 2019, 94 JMU graduates registered as attending rural physicians for the CBCC. Among them, 20 candidates for PIF-SRL mentors in 2018 and 2019 were randomly selected and informed consent for their contribution to PIF-SRL in this study was requested. Eventually, 17 and 13 JMU alumni agreed to participate in 2018 and 2019, respectively, 8 of whom participated in both years.

Independent of this study, the JMU Center for Community Medicine matched one alumnus with one to three students for the CBCC. The 30 PIF-SRL alumni-mentors were paired with 1 to 3 students each before informed consent was obtained. In this study, students paired with the 30 PIF-SRL alumni were chosen as candidates for the PIF-SRL group subjects. There were 22 and 20 candidates in 2018 and 2019, respectively. One candidate in 2019 declined participation. Eventually, 41 students were registered as subjects in the PIF-SRL group. Simultaneously, 41 control subjects were chosen from the same school year cohort and informed consent to participate was obtained. Control subjects experienced the regular CBCC mentorship without PIF-SRL. Because previous studies have shown that gender (Ray et al., 2003) and academic performance (Lucieer et al., 2016) might independently influence SRL development, participants in both groups were paired by gender and academic ranking from the previous year (Year 4).

C. Procedures

A convergent mixed method was chosen for the first research question ‘Does PIF-SRL improve SRL during the period around the clinical clerkship?’ to identify common data between quantitative and qualitative results (Creswell & Clark, 2017). Next, an explanatory mixed method was used to address the second research question ‘How does the PIF-oriented elements in PIF-SRL improve SRL?’. A rationale for this method is that follow-up qualitative approaches can explain quantitative results (Creswell & Clark, 2017). We conducted this mixed method study in the paradigm of pragmatism, which emphasises solutions to research questions and integrates qualitative and quantitative research results to obtain general findings (Shannon-Baker, 2016).

1) Quantitative approach: Learner SRL levels were measured with a Japanese-language version of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ-J) before (mid-July) and after (mid-September) subjects participated in CBCC with or without PIF-SRL. The MSLQ (Pintrich et al., 1991) is composed of 81 items with seven-point Likert scales quantifying levels of 9 types of SRL strategy (rehearsal, elaboration, organisation, critical thinking, metacognitive self-regulation, time and study environment, effort regulation, peer learning, and help seeking), and 6 variables of motivation states (intrinsic goal orientation, extrinsic goal orientation, task value, control of learning beliefs, self-efficacy for learning and performance, and test anxiety). All 81 items of the MSLQ were used as done previously in a medical school context (Cho et al., 2017) because it was believed the 15 SRL-related categories could multi-dimensionally identify differences between the PIF-SRL group and control group. Translation to Japanese was conducted by the main author (YM) and back-translation to English by a co-author (AJL). For the MSLQ validation, the Cronbach alpha and McDonald omega were measured for 15 categories (Matsuyama et al., 2021).

2) Qualitative approach: To explore changes in motivation, strategies and reflective behaviours from self-reflection and study during the clinical clerkship, we created a questionnaire composed of seven questions (Matsuyama et al., 2021). All participants answered the questionnaire within two weeks after post-CBCC PIF-SRL mentoring. In late September 2019, one-on-one interviews were also conducted after intensive qualitative data analysis of the questionnaire from 41 participants in 2018 and 2019. Three interviewers familiar with the CBCC but not engaged in the assessment of Year 5 students conducted interviews in order to encourage interviewees to openly articulate their own perceptions. Twelve students in the 2019 PIF-SRL group consented to participate in interviews conducted in a semi-structured manner using an interview form with similar questions to those in the questionnaire (Matsuyama et al., 2021). The interviewers were instructed beforehand by the main author (YM) to obtain data about changes in perception regarding motivation, strategies and reflective behaviours after experiencing PIF-SRL. After collecting interview data from 10 students, the two main authors (YM and HO) found no additional meaningful codes emerging and, concluding that data saturation had been reached (Hennink et al., 2017), and stopped further interview data collection.

D. Analysis

1) Quantitative approach: The 15 MSLQ-J pre-intervention subcategory scores of the PIF-SRL group and control group were compared using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). After confirming that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups, subtracted (post-pre) scores in the 15 MSLQ-J subcategories were compared between the two groups using Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA. This non-parametric method was used because of considerable skewness in distribution in the scales of several items and outliers in other scales in MSLQ-J. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The effect sizes for comparisons were also calculated using ε2 values, wherein small effect sizes ranged from 0.01 to <0.08, medium effect sizes ranged from 0.08 to <0.26 and large effect sizes ranged from ≥0.26. We used JAMOVI version 1.0.7.0 for statistical analysis.

2) Qualitative approach: Qualitative data from PIE, the questionnaire and interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. Anonymised qualitative data were analysed in accordance with the six phases proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Initial coding was conducted by the two Japanese researchers (YM and HO). YM, the lead author, was involved in the development of PIF-SRL and has previous experience with qualitative studies relevant to SRL. HO was not directly engaged in PIF-SRL but has had experience in qualitative studies relevant to SRL. The transcripts were thoroughly analysed using an inductive coding approach until agreement on coding was achieved through repetitive face-to-face meetings between the pair.

The focus was on changes in SRL (motivation, learning strategies, and reflective behaviours), and student opinion of the effects of PIF-SRL on SRL. Representative codes and statements were translated into English by an American professor literate in both English and Japanese (AJL). In the final phase, two other authors (JL and CV; education psychologists familiar with SRL) joined the discussion, and a higher-level synthesis of the codes was developed.

III. RESULTS

A. Quantitative Data

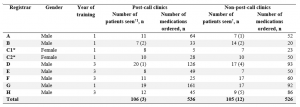

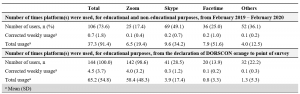

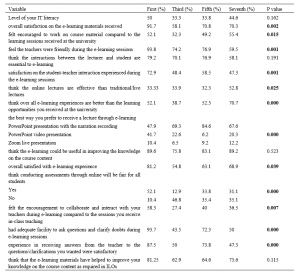

Mean averages, standard deviations, and median averages for fifteen MSLQ-J categories plus gender and academic rank data at pre-intervention are shown in Table 1. No categories significantly differed between the PIF-SRL and control groups.

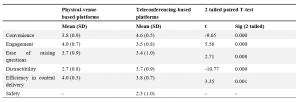

The subtracted (post- minus pre-intervention) between-group scores in the 15 MSLQ-J categories are shown in Table 2. Improvements in 1. Intrinsic goal orientation and 10. Critical thinking were significantly better in the PIF-SRL group than the control group with ε2 values 0.096 (p = .005) and 0.051 (p = .041), respectively. The quantitative data used in this study are accessible (Matsuyama et al., 2021).

|

|

|

PIF-SRL (N=41) |

Control (N=41) |

p value |

|

Gender |

Male/Female |

30/11 |

30/11 |

|

|

Academic rank in the previous school year |

Mean±SD |

43.7±33.0 |

45.3±32.4 |

0.79 |

|

Median |

36 |

37 |

||

|

1. Intrinsic goal orientation |

Mean±SD |

4.07±1.18 |

4.23±1.16 |

0.42 |

|

Median |

4.00 |

4.25 |

||

|

2. Extrinsic goal orientation |

Mean±SD |

3.67±1.46 |

3.69±1.44 |

0.95 |

|

Median |

3.75 |

3.75 |

||

|

3. Task value |

Mean±SD |

5.12±0.95 |

4.85±1.17 |

0.34 |

|

Median |

5.33 |

4.83 |

||

|

4. Control beliefs |

Mean±SD |

4.92±0.92 |

4.69±0.98 |

0.09 |

|

Median |

4.75 |

4.50 |

||

|

5. Self-efficacy |

Mean±SD |

3.52±1.11 |

3.36±1.23 |

0.72 |

|

Median |

3.38 |

3.50 |

||

|

6. Test anxiety |

Mean±SD |

3.94±1.17 |

4.35±1.03 |

0.12 |

|

Median |

4.20 |

4.40 |

||

|

7. Rehearsal |

Mean±SD |

4.38±1.07 |

4.23±0.91 |

0.81 |

|

Median |

4.25 |

4.25 |

||

|

8. Elaboration |

Mean±SD |

4.46±1.00 |

4.32±1.13 |

0.86 |

|

Median |

4.50 |

4.50 |

||

|

9. Organisation |

Mean±SD |

4.45±1.35 |

4.27±1.30 |

0.66 |

|

Median |

4.50 |

4.50 |

||

|

10. Critical thinking |

Mean±SD |

4.11±1.10 |

4.30±1.21 |

0.36 |

|

Median |

4.20 |

4.40 |

||

|

11. Metacognitive regulation |

Mean±SD |

4.23±0.70 |

4.18±0.82 |

0.89 |

|

Median |

4.25 |

4.17 |

||

|

12. Time and environment |

Mean±SD |

4.63±0.85 |

4.44±0.87 |

0.38 |

|

Median |

4.50 |

4.25 |

||

|

13. Effort management |

Mean±SD |

3.92±1.07 |

3.91±0.96 |

0.83 |

|

Median |

4.00 |

4.00 |

||

|

14. Peer learning |

Mean±SD |

4.70±1.24 |

4.40±1.24 |

0.36 |

|

Median |

4.67 |

4.67 |

||

|

15. Help seeking |

Mean±SD |

4.46±0.97 |

4.37±0.96 |

0.34 |

|

Median |

4.50 |

4.25 |

Table 1. Pre-intervention scores for the 15 categories of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire-J and descriptive gender and academic rank data

|

|

|

PIF-SRL (N=41) |

Control (N=41) |

p value |

ε2 value |

|

1. Intrinsic goal orientation |

Mean±SD |

0.48±1.02 |

-0.26±1.17 |

0.005 |

0.096 |

|

Median |

0.50 |

-0.25 |

|||

|

2. Extrinsic goal orientation |

Mean±SD |

0.31±1.36 |

-0.05±1.04 |

0.200 |

0.020 |

|

Median |

0.25 |

0.00 |

|||

|

3. Task value |

Mean±SD |

0.12±1.08 |

-0.02±1.08 |

0.587 |

0.004 |

|

Median |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|||

|

4. Control beliefs |

Mean±SD |

0.04±1.07 |

0.02±1.16 |

0.665 |

0.002 |

|

Median |

0.00 |

0.25 |

|||

|

5. Self-efficacy |

Mean±SD |

0.49±1.20 |

0.10±0.82 |

0.210 |

0.019 |

|

Median |

0.25 |

0.00 |

|||

|

6. Test anxiety |

Mean±SD |

0.30±1.07 |

-0.11±1.07 |

0.152 |

0.025 |

|

Median |

0.20 |

0.00 |

|||

|

7. Rehearsal |

Mean±SD |

0.23±1.23 |

-0.02±1.14 |

0.500 |

0.006 |

|

Median |

0.25 |

0.00 |

|||

|

8. Elaboration |

Mean±SD |

0.30±1.23 |

0.13±1.03 |

0.083 |

0.037 |

|

Median |

0.50 |

0.00 |

|||

|

9. Organisation |

Mean±SD |

0.08±1.48 |

-0.04±1.08 |

0.915 |

<0.001 |

|

Median |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|||

|

10. Critical thinking |

Mean±SD |

0.48±1.08 |

-0.06±1.21 |

0.041 |

0.051 |

|

Median |

0.60 |

0.00 |

|||

|

11. Metacognitive regulation |

Mean±SD |

0.31±0.80 |

-0.07±0.69 |

0.060 |

0.043 |

|

Median |

0.16 |

0.00 |

|||

|

12. Time and environment |

Mean±SD |

0.02±1.28 |

0.02±1.03 |

0.700 |

0.002 |

|

Median |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|||

|

13. Effort management |

Mean±SD |

0.41±0.89 |

0.10±0.85 |

0.092 |

0.035 |

|

Median |

0.25 |

0.00 |

|||

|

14. Peer learning |

Mean±SD |

0.03±1.28 |

0.03±1.03 |

0.978 |

<0.001 |

|

Median |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|||

|

15. Help seeking |

Mean±SD |

0.04±1.27 |

0.04±0.84 |

0.819 |

<0.001 |

|

Median |

0.00 |

-0.25 |

Table 2. Subtracted (post- minus pre-intervention) scores in the 15 categories of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire-J

A higher-level synthesis of the codes eventually resulted in three major themes corresponding to the second research question, ‘How does the PIF-oriented elements in PIF-SRL improve SRL?’

1) Active expansion of learning goals based on professional responsibility: The first theme consisted of subthemes which included learning motivated from responsibility, clear learning goals based on explicit self-images, and wider learning goals based on wider perceptions of professional roles.

Students viewed in-depth communication with mentors through the PIF-SRL platform with PIE helpful for imagining their future professional responsibilities in a positive and objective manner.

‘A lot of opening questions were, for example, what do you expect from work, what is the worst that can happen if you failed to live up to the expectations you have set for yourself, that’s the situation you’re working under when you’re a doctor, and the first time I really felt this was the time I really should be aware of this, it was positive, and actually although I was still just a student, I could objectively assess what I was thinking…’

(Interview, 1D-10)

During PIF-SRL mentoring, they were able to realise that knowledge beyond what they were currently learning in the curriculum was required of them as professionals. They were actively trying to set learning goals that they could connect to what they would need to learn in the future.

‘Knowing what skills and knowledge the region expects of you, you can create a working image of your future situation, and this becomes motivation to learn about new areas you weren’t aware of before.’

(Questionnaire, 2019-19)

Aside from the expansion of perceived learning goals, students also began to see that self-study was required to ensure the authenticity of medical knowledge applicable to their future professional work. This was linked to Theme 3.

‘What I got was that incomplete understanding or recall wasn’t going to cut it when actually applying knowledge in the clinic. I began to train with the awareness that I wouldn’t be useful there if I didn’t understand and remember all I learned about disease.’

(Questionnaire, 2018-21)

2) Elaboration by linking future professional task processes to daily self-study contents: The second theme was comprised of subthemes which included focus on the task processes of role models and relating daily self-study content to future roles.

After PIF-SRL, students began to imagine what they would do as professionals in future medical practice at a task process-based level. Because their vivid future professional image helped them identify deep responsibilities for their professional tasks, they began to carefully observe mentors’ complete professional tasks in the clinical clerkship and articulate task processes. This in turn encouraged students to select learning strategies which linked information in daily self-study materials (e.g. textbooks) to professional task processes, which is referred to as ‘elaboration’ in MSLQ.

‘I started to learn in terms of what I would do if it were me. I also started to think about the details and not just the general flow of things, and to apply them as much as possible to reality.’

(Questionnaire, 2018-8)

‘Since the clerkship, I’ve been able to relate and recall what I actually encountered in the clinical clerkship, and when I was actually reading textbooks in self-study, I was able to align it with my future work content, and if there were things that applied, I would emphasise them… The study method that I use to impress upon myself was strengthened in the mentoring and clerkship…’

(Interview, 1D-3)

3) Critical thinking based on the pursuit of authentic medical knowledge: The third theme was comprised of subthemes which included realisation of the significance of authenticity pursuit, access to a wide variety of educational materials, and critical reflection.

Because they began to perceive that what they were learning would affect the lives of individual patients, they recognised the significance of gaining authentic knowledge that could be applied to each patient, differentiated from textbook-based universal knowledge.

‘It’s really important to learn about disease by studying the texts and gaining comprehensive knowledge, but since that tertiary material is insufficient for responding to clinical questions and individual patient backgrounds, I’m not sure that knowledge is useful in clinical practice. For that, what’s most meaningful are secondary materials like UpToDate, or if you still have doubts then primary material research papers.

(Questionnaire, 2019-1)

After beginning to pursue authenticity of medical knowledge, students found diversity and inconsistency in information from learning materials. To deal with this, they began to formulate inquiries focusing on self-study, a variety of information resources, and different viewpoints. Through this strategic shift, critical thinking emerged in an intrinsic manner.

‘I’ve come to think opinions are going to diverge to some extent as you get down to actually asking opinions of several different doctors, and these are choices you have to make, the stages you go through when studying.’

(Interview, 1C-7)

‘Having the ability to doubt, and because it’s science not taking everything at face value, becoming sceptical, I think that’s necessary.’

(Interview, 3C-14)

IV. DISCUSSION

Regarding the first research question ‘Does PIF-SRL improve SRL during the period around the clinical clerkship?’, our findings of a moderate improvement in intrinsic goal orientation and a mild improvement in critical thinking in the PIF-SRL group compared with the control group suggested that PIF-SRL promotes SRL. The qualitative analysis supports the MSLQ-J results. With regard to intrinsic goal orientation, students’ recognition of their future ‘professional responsibility’ was a key to fostering this. Further, recognition of professional responsibility led to critical thinking — critical evaluation of learning materials or their interpretation — as a means of pursuing authenticity of information for professional task processes. The consistency between quantitative and qualitative data was notable in understanding the outcomes of the PIF-oriented mentoring on SRL.

There was no statistical significance in the difference between the PIF-SRL and the control groups regarding elaboration in MSLQ-J data. However, qualitative analysis illuminated that PIF-SRL students’ attention to professional task processes triggered a strategy toward elaboration of knowledge in accordance with their future professional task processes. Reasons for this discrepancy might include the number of participants and sensitivity of the outcome measurement (Tonkin-Crine et al., 2016). Further research is needed to address these issues. However, we believe that in order to remediate learning strategies necessary for professional tasks or professionalism, it is useful to reflect on daily self-learning in accordance with the process of professional work shown by role models.

Recent research pertaining to educational intervention for SRL emphasises analysing the learning process of a particular task in detail and remediating the individual process (Artino et al., 2014; Durning et al., 2011; Gandomkar et al., 2016). While we generally concur with this, learning tasks that take place in clinical practice are limitless, so it would be beneficial to explore a foundational intervention applicable to a variety of tasks in clinical settings. The PIF-oriented mentoring in this study is presented as a foundational SRL intervention for a variety of clinical settings wherein learners can recognise professional identities and role models can suggest learning strategies.

The major strength of this study is that the subjects were Japanese students, who are considered to engage less in self-regulation than their Western counterparts (Iwata & Doi, 2017; Matsuyama et al., 2018; Tagawa, 2008). We believe that our study can provide educators with evidence that PIF-oriented educational schemes promote better learning behaviours in institutions desiring to promote undergraduate SRL. Another strength is that there were few formal classes or training programmes – i.e., intervening confounders — except for PIF-SRL and CBCCs between pre- and post-data collection (Figure 1). We believe the study schedule, without other educational interventions, optimised learning comparison outcomes between the two groups. For instance, changes in accessing learning materials for critical thinking (e.g. UpToDate) can be attributed mostly to the experiences in PIF-oriented mentoring and the subsequent CBCCs.

This study also has some limitations. First, we did not collect one-on-one interview data from 2018 cohort. Second, we did not examine student SRL changes from the mentor’s perspective, despite the fact that mentors’ perceptions of changes in students’ SRL would be as useful as, or more useful than students’ self-administered data. Third, reference to mentors’ self-images in the PIF-SRL could help students in PIF-SRL construct their professional self-image more clearly; however, this may cause bias student statements in the PIF-SRL form regardless of their real professionalism. Future research needs to measure PIF and SRL in more multifaceted and objective manners. Lastly, we do not have long-term outcomes of PIF-SRL. According to previous studies (Cruess et al., 2014; Cruess & Cruess, 2019; Kalet et al., 2017; Oyserman et al., 2017), identity is flexibly attuned to immediate situations rather than fixed in memory. Plus, frequently and fluently cued identities form stable ones. Accordingly, we speculate that the repetitive use of PIF-SRL could strengthen learners’ SRL. Validation of this notion would require a longitudinal cohort study.

Evaluation of these results suggests that the ability of PIF-SRL to work effectively requires that the quality of mentors be guaranteed. One reason for the success of the relatively random combination of students and mentors in this PIF-SRL group is that all are future rural physicians, and their mentors are also alumni of JMU in rural practice. On the other hand, for medical students from other universities who can follow diverse specialties and career paths, use of the PIF-SRL will require pairing medical students with appropriate mentors who can respond to students’ identities or future images. Also, it is important to pair students not only by their interest in future expertise, but also by looking at the mental and physical traits of individual students as they relate to motivation and student career choices (Henning et al., 2017). Moreover, in-depth conversations that would foster professionalism might not be done only through text messages in the PIF-SRL platform, but also through video calls and in-person meetings that would convey the participants’ voices, facial expressions, and mood. We think it is important for mentors to actively provide opportunities for direct dialogue with students. In light of this challenge, the present study supports PIF-oriented intervention as a method for improvement in SRL.

V. CONCLUSION

Allowing for these limitations and the need for further research, this study indicated that PIF-oriented education in a clinical clerkship with alumni mentors increased immediate intrinsic goal orientation and promoted a shift to SRL. Their SRL was characterised as task process-based elaboration, with critical thinking emerging from the pursuit of authenticity in medical practice.

Notes on Contributors

Yasushi Matsuyama reviewed the literature, designed the study, conducted both quantitative and qualitative data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Hitoaki Okazaki conducted qualitative data analysis.

Kazuhiko Kotani designed the study, and collected both quantitative and qualitative data.

Yoshikazu Asada collected both quantitative and qualitative data.

Shizukiyo Ishikawa collected both quantitative and qualitative data.

Adam Jon Lebowitz contributed to Japanese-English translation of data collection tools and qualitative data from questionnaire and interviews.

Jimmie Leppink reviewed the literature, designed the study, conducted both quantitative and qualitative data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Cees van der Vleuten reviewed the literature, designed the study, conducted both quantitative and qualitative data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jichi Medical University (Reference number: 19-001). Consent was obtained from all participants for the research study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Adina Kalet and Dr. Verna Monson for their consultation and provision of supplementary materials. We would also like to thank Drs. Yasuko Aoyama, Yoshitaka Maeda, and Maiko Watanabe for their support in conducting one-on-one interviews. We would also like to thank Ms. Akemi Watanabe and Yasuko Koguchi for their helpful assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI [Grant number JP17K08924].

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The quantitative data used in this study, Supplemental files are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14312507

Representative qualitative data translated into English are shown in the Result section (Matsuyama et al., 2021). All qualitative data written in Japanese are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

A preprint of the previous version of our manuscript, which is not peer-reviewed, is available at https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-12667/v1

References

Aho, J. M., Ruparel, R. K., Graham, E., Zendejas-Mummert, B., Heller, S. F., Farley, D. R., & Bingener, J. (2015). Mentor-guided self-directed learning affects resident practice. Journal of Surgical Education, 72(4), 674–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.01.008o

Artino, A. R., Jr., Cleary, T. J., Dong, T., Hemmer, P. A., & Durning, S. J. (2014). Exploring clinical reasoning in novices: A self-regulated learning microanalytic assessment approach. Medical Education, 48(3), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12303

Artino, A. R., Jr., Dong, T., DeZee, K. J., Gilliland, W. R., Waechter, D. M., Cruess, D., & Durning, S. J. (2012). Achievement goal structures and self-regulated learning: Relationships and changes in medical school. Academic Medicine, 87(10), 1375–1381. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182676b55

Berkhout, J. J., Helmich, E., Teunissen, P. W., van den Berg, J. W., van der Vleuten, C. P., & Jaarsma, A. D. (2015). Exploring the factors influencing clinical students’ self-regulated learning. Medical Education, 49(6), 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12671

Berkhout, J. J., Helmich, E., Teunissen, P. W., van der Vleuten, C., & Jaarsma, A. (2018). Context matters when striving to promote active and lifelong learning in medical education. Medical Education, 52(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13463

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brydges, R., & Butler, D. (2012). A reflective analysis of medical education research on self-regulation in learning and practice. Medical Education, 46(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04100.x

Cho, K. K., Marjadi, B., Langendyk, V., & Hu, W. (2017). Medical student changes in self-regulated learning during the transition to the clinical environment. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0902-7

Cleary, T. J., & Sandars, J. (2011). Assessing self-regulatory processes during clinical skill performance: A pilot study. Medical Teacher, 33(7), e368–e374. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.577464

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications.

Cruess, R. L., & Cruess, S. R. (1997). Teaching medicine as a profession in the service of healing. Academic Medicine, 72(11), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199711000-00009

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2014). Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Academic Medicine, 89(11), 1446–1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

Cruess, S. R., & Cruess, R. L. (2019). The development of professional identity. In T. Swanwick., K. Forrest., B. C. O’Brein (Eds.), Understanding medical education; Evidence, theory, and practice (3rd ed., pp. 239–254). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119373780.ch17

Durning, S. J., Cleary, T. J., Sandars, J., Hemmer, P., Kokotailo, P., & Artino, A. R. (2011). Perspective: Viewing “strugglers” through a different lens: How a self-regulated learning perspective can help medical educators with assessment and remediation. Academic Medicine, 86(4), 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820dc384

Frank, J. R. (2005). The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Gandomkar, R., Mirzazadeh, A., Jalili, M., Yazdani, K., Fata, L., & Sandars, J. (2016). Self-regulated learning processes of medical students during an academic learning task. Medical Education, 50(10), 1065–1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12975

Henning, M. A., Krägeloh, C. U., Booth, R., Hill, E. M., Chen, J., & Webster, C. S. (2017). Profiling potential medical students and exploring determinants of career choice. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 2(1), 7-15. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-1/OA1019

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

Iwata, K., & Doi, A. (2017). Can hybrid educational activities of team and problem based learning program be effective for Japanese medical students? International Journal of Medical Education, 8, 176–178. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.591b.2bc8

Jarvis-Selinger, S., Pratt, D. D., & Regehr, G. (2012). Competency is not enough: Integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Academic Medicine, 87(9), 1185–1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

Kalet, A., Buckvar-Keltz, L., Harnik, V., Monson, V., Hubbard, S., Crowe, R., Song, H. S., & Yingling, S. (2017). Measuring professional identity formation early in medical school. Medical Teacher, 39(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270437

Kalet, A., Buckvar-Keltz, L., Monson, V., Harnik, V., Hubbard, S., Crowe, R., Ark, T. K., Hyuksoon, Song, H. S., & Yingling, S. (2018). Professional Identity Formation in medical school: One measure reflects changes during pre-clerkship training. MedEdPublish, 7(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2018.0000041.1

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Harvard University Press.

Lam, T. P., & Lam, Y. Y. (2009). Medical education reform: The Asian experience. Academic Medicine, 84(9), 1313–1317. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b18189

Lucieer, S. M., Jonker, L., Visscher, C., Rikers, R. M. J. P., & Themmen, A. P. N. (2016). Self-regulated learning and academic performance in medical education. Medical Teacher, 38(6), 585–593. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1073240

Matsuyama, Y., Nakaya, M., Okazaki, H., Leppink, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2018). Contextual attributes promote or hinder self-regulated learning: A qualitative study contrasting rural physicians with undergraduate learners in Japan. Medical Teacher, 40(3), 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1406074

Matsuyama, Y., Nakaya, M., Okazaki, H., Lebowitz, A. J., Leppink, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2019). Does changing from a teacher-centered to a learner-centered context promote self-regulated learning: A qualitative study in a Japanese undergraduate setting. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1550-x

Matsuyama, Y., Okazaki, H., Kotani, K., Asada, Y., Ishikawa, S., Lebowitz, A. J., Leppink, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2021). Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study. [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14312507

Matsuyama, Y., Okazaki, H., Kotani, K., Asada, Y., Ishikawa, S., Lebowitz, A. J., Leppink, J., & van der Vleuten, C. (2020). Education in professional identity formation enhances self-regulated learning: A mixed-method exploratory study from a community-based clinical clerkship in Japan. [Preprint]. Research Square. January 28, 2020. [cited June 10, 2020] Available from: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.22088/v1

Okayama, M., & Kajii, E. (2011). Does community-based education increase students’ motivation to practice community health care? A cross sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 11(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-19

Oyserman, D., Lewis, Jr., N. A., Yan, V. X., Fisher, O., O’Donnell, S. C., & Horowitz, E. (2017). An identity-based motivation framework for self-regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 28(2-3), 139-147. http://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2017.1337406

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Technical Report 91-B-004). The Regents of the University of Michigan. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED338122.pdf

Ray, M. W., Garavalia, L. S., & Gredler, M. E. (2003, April 21-25). Gender differences in self-regulated learning, task value, and achievement in developmental college students. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476176.pdf

Sandars, J., & Cleary, T. J. (2011). Self-regulation theory: Applications to medical education: AMEE Guide No. 58. Medical Teacher, 33(11), 875–886. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.595434

Shannon-Baker, P. (2016). Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(4), 319-334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815575861

Song, H. S., Kalet, A. L., & Plass, J. L. (2011). Assessing medical students’ self-regulation as aptitude in computer-based learning. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 16(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9248-1

Stuart, E., Sectish, T. C., & Huffman, L. C. (2005). Are residents ready for self-directed learning? A pilot program of individualized learning plans in continuity clinic. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 5(5), 298–301. https://doi.org/10.1367/A04-091R.1

Tagawa, M. (2008). Physician self-directed learning and education. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 24(7), 380–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70136-0

Tonkin-Crine, S., Anthierens, S., Hood, K., Yardley, L., Cals, J. W., Francis, N. A., Coenen, S., van der Velden, A. W., Godycki-Cwirko, M., Llor, C., Butler, C. C., Verheij, T. J., Goossens, H., Little, P., & GRACE INTRO/CHAMP consortium (2016). Discrepancies between qualitative and quantitative evaluation of randomised controlled trial results: Achieving clarity through mixed methods triangulation. Implementation Science, 11, 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0436-0

Turan, S., & Konan, A. (2012). Self-regulated learning strategies used in surgical clerkship and the relationship with clinical achievement. Journal of Surgical Education, 69(2), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.09.003

van Houten-Schat, M. A., Berkhout, J. J., van Dijk, N., Endedijk, M. D., Jaarsma, A. D. C., & Diemers, A. D. (2018). Self-regulated learning in the clinical context: A systematic review. Medical Education, 52(10), 1008–1015. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13615

Van Nguyen, H., Laohasiriwong, W., Saengsuwan, J., Thinkhamrop, B., & Wright, P. (2015). The relationships between the use of self-regulated learning strategies and depression among medical students: An accelerated prospective cohort study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.894640

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3), 329.

*Yasushi Matsuyama

3311-1

Yakushiji, Shimotsuke,

Tochigi, 329-0498

Email: yasushim@jichi.ac.jp

Submitted: 2 November 2020

Accepted: 8 February 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 37-48

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/OA2425

Stephen Bradley1, Aaron Ooi2, Kerry Stafford3, Shuvayon Mukherjee1 & Marcus A. Henning4

1Department of Paediatrics, Lakes District Health Board, New Zealand; 2Department of Paediatrics, Waikato District Health Board, New Zealand; 3Department of Paediatrics, Christchurch Hospital, New Zealand; 4Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Introduction: The paediatric team handover process is a crucial workplace practice and comprises the transfer of patient information from one shift to another involving medical professionals and students. A qualitative study was performed to analyse the feasibility, functionality, benefits and limitations of the dramaturgical approach when applied to examining a handover session.

Methods: Data relating to one handover were collected and analysed from video and audio recordings, notes created by two independent observers and a de-identified copy of the handover sheet.

Results: The dramaturgical constructs and subsequent findings allowed us to make informed inferences about the dynamics of the handover procedure. The directors/lead actors consisted of a consultant and a registrar. One consultant was transitory and the remaining 12 attendees were either major support, support or bit actors. The students (bit actors/audience) were included when a learning point was emphasised. The script was informal and improvised as the discussion emphasised certain facets of patient care or accentuated learning points. The staging involved the seating arrangement, a whiteboard, computer screen and ongoing data presentation. The performance suggested a handover of two halves: one emphasising learning and the other allocation of patient care responsibility.

Conclusion: We concluded that the real-life drama occurring within a handover was feasibly analysed, with its functionality demonstrated, using the dramaturgical investigative system. The multifaceted recordings enabled researchers to review the ‘authentic’ handover system without censorship. These findings have implications for educational and organisational research.

Keywords: Dramaturgical, Handover, Paediatric, Methodology

Practice Highlights

- Dramaturgical methodology provided a unique, authentic and detailed analysis of the handover.

- The dramaturgical research methodology used to evaluate the handover was feasible and functional.

- This research methodology can be used to analyse education within similar team based settings.

- This research methodology can be applied to the team handovers and other complex health meetings.

- This research methodology identifies important clinical/educational roles and dynamics within teams.

I. INTRODUCTION

Hospital team handovers involve effective transfer of information and responsibility from one health professional to another, ensuring continuity of patient care (Australian Medical Association Limited, 2006; Hilligoss & Cohen, 2011). The level of communication needs to be comprehensive, unambiguous and coherent so that patient information is easily understood, thus optimising patient care through the meaningful and efficient transfer of patient information (Fujikawa et al., 2021). This is crucial given the ramifications for optimising patient care and minimising potential treatment error, including miscued transfer of knowledge, insertion of faulty or misleading information, treatment delay, and poor patient outcomes (Arora et al., 2005; Bomba & Prakash, 2005). To explore the nuances occurring in handover practice from organisational behaviour and educational perspectives, different methodological approaches need to be developed.

In this paper, we propose that the dramaturgical approach can optimally analyse handover dynamics, as it is an integrated, pragmatic and multidimensional approach. This approach uses multi-source feedback from video and audio recordings, observer records, and transcripts of analysis. The dramaturgical approach argues that the individuals present in the activity assume different roles that influence the way they communicate and behave (Canary et al., 2008; Goffman, 1959; Henderson, 2005). Using this approach, the handover activity can be analysed much like a drama or element of theatre. The dramaturgical approach has the potential to offer insights into the clinical and educational handover components, much like the insights drawn when applying this approach to analysing healthcare simulations (Crea, 2017), decision-making aspects of an emergency department triage (Forde, 2014), and behaviour of radiographers and their patients (Murphy, 2009). This analytical approach enables the researcher to be present at the moment of the occurrence, rather than relying on retrospective data obtained when subsequently interviewing participants. Interviews can be a powerful means of obtaining information, but require participants to accurately retell their experiences of the activity (DiCicco‐Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). The dramaturgical approach tells it for what it is, and allows researchers the ability to see and hear the authentic process of communication (Goffman, 1959; Murphy, 2009). We surmised that the dramaturgical approach would be a more comprehensive evaluative system and thus well suited for collecting observational data that could inform training and development initiatives within hospital systems.

The research aim of this study was to explore the feasibility and functionality of the dramaturgical methodological system of analysis not yet applied to the handover procedure.

The research questions driving this study include:

- How can the dramaturgical approach feasibly be applied to the handover system?

- How does the dramaturgical approach describe the functional dynamics of the handover procedure?

- What are the benefits and limitations associated with applying this research methodology?

II. METHODS

A. Phenomenon of Interest

Feasibility, functionality and quality were informed by examples taken from one handover involving team discussion regarding patients admitted to a general paediatric ward (20 beds) and a Special Care Baby Unit (8 cots) in a New Zealand secondary-level hospital (Hensher et al., 2006).

B. Sample/Participants

All the health professionals and medical students involved in one handover were asked to volunteer for the study, with eligibility determined by consent and approval from hospital management. Informed consent was obtained after eligible participants read a detailed information sheet, provided by an administrator, followed by a consent form that they then signed.

C. Data Collection

Data were obtained from several sources.

- Five video cameras were situated in the handover room to obtain multiple angles of the handover. Two audio recorders were placed in the room and served as the primary sources of data for transcription.

- The final transcription of events was checked by all authors using data from the cameras.

- Notes on the salient aspects of handover interactions were made by two present ‘unknown’ observers (i.e., one medical student and one medical educationalist).

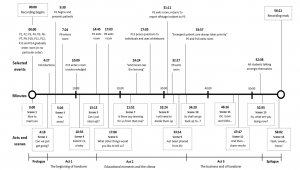

A diagram of the seating positions of each participant was constructed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Handover room layout depicting seating arrangements, participants (P1-P15, with original position participants sat in), 2 observers (Ob1 and Ob2) and equipment.

D. Ethical Considerations

Confidentiality of the key informants was maintained by the following criteria:

- All participants were given an anonymised label (P1 to P15).

- All patients discussed within the handover were anonymised (labelled 1 to 36) and identifiable information was deleted from patient reports.

- Several hospital employees involved in the study were not present at the handover and transcription was conducted by an uninvolved third party.

-

-

E. Data Analysis

To test the feasibility of the dramaturgical approach, a framework was adapted exploring the perspectives of the actors and audience, the script, the staging and the overall performance (Canary et al., 2008; Crea, 2017; Henderson, 2005). Delineation of roles within the handover (Preves & Stephenson, 2009; Schell, 2016) identified the following ‘actors’: lead, major support, support, and bit actors. The perceived director was involved in the leading and facilitation of the handover (Goffman, 1959). The audience was defined as observers or those actors minimally involved in the main discussion (Canary et al., 2008; Hays & Weinert, 2006). Other factors considered in the analysis included scripting, staging, and performance analysis (Hays & Weinert, 2006).

We scrutinised the data using a deductive thematic content analysis based on dramaturgy criteria (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The usefulness of voice-occupied time (VOT) was appraised and VOT was defined as the total time a participant spoke during the entire handover divided by the total duration of the handover, expressed as a percentage. The utility of a timeline considered the dynamics connected to scene development. Lastly, the trustworthiness of the qualitative data analysis protocol was audited (Elo et al., 2014).

III. RESULTS

The following data were used to assess the feasibility, functionality and quality of the dramaturgical process. For full data details, please refer to Figshare (2020).

A. Actors and Audience

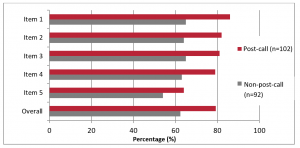

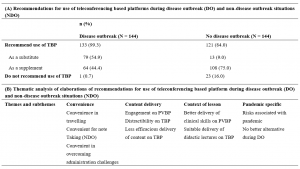

The handover involved 15 participants (Table 1).

Table 1: Roles and number of participants and observers present in handover.

The VOT analysis (see Table 2) was useful in quantifying participation as aligned with perceived roles. The participant with the highest VOT was deemed to be the lead actor, while the second highest VOT was classified as the major supporting actor. Participants with VOTs of greater than 5% were defined as supporting actors, and participants who had VOTs of less than 5% were judged to be bit actors and audience. Accordingly, the lead consultant (the initial director) (P13) and the senior registrar (P3), who each had more than 15% of the VOT, were judged to be the lead and major support actors respectively. Eight (53%) of the participants were identified to be present as bit actors or audience.

Table 2: Percentage of voice occupied time (VOT) and number of contributions per participant.

A separate analysis was conducted counting the number of contributions (clearly-heard comments) each handover participant made, with a total of 446 contributions quantified during the handover. This was correlated with the VOT and provided a point of comparison to identify crucial facets of the handover drama.

B. Roles

The utility of the dramaturgical approach was also demonstrated in identifying the roles of handover members. It was ascertained that the three consultants had distinct roles. The lead actor (P13) was the consultant on the ward that week. She led the beginning of the handover, directed the flow of discussion and took on a major teaching role. The second consultant (P9), who had been on call overnight, contributed important information and was involved in teaching. The third consultant (P8) sought information about suitable patients for teaching, but contributed little to the discussions.

A further key role identified was the senior registrar (P3), who contributed little to the handover until the dramatic time when a phone call interrupted the handover. After the departure of the lead consultant (P13), she acquired the major support actor role, but did so in a very business-like manner to ensure that all patients were discussed and a safe plan established.

Roles were highlighted participants’ costumes. The doctors and students in the handover wore smart-casual attire. Several clearly had available stethoscopes, whilst the nurse wore a uniform.

C. Script

The script was found to be a useful informal source of information. Whilst close attention was given to the handover sheet containing patient details, it was clear that participants improvised. The dramaturgical analysis established that the patients cared for by the paediatric team were the subjects of the performance. Patients were referred to respectfully, and the discussion was focused on their daily requirements.

D. Staging

The room (Figure 1) was notable for the horseshoe-shaped arrangement of tables and chairs, which enabled the researchers to evaluate visibility of participants and their access to technological equipment. The notion of staging also enabled researchers to establish the activities that occurred within the room (on-stage) as opposed to those outside the room (off-stage).

E. Props

The most significant prop was the handover sheet (or script) listing the patients’ names, demographic data, their medical issues, and initiated investigations and plan.

F. Performance

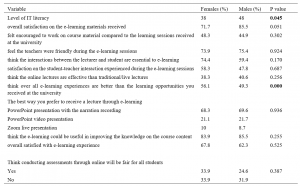

1) Scenes: The scenes could be classified as follows. These were the prologue, three acts, and an epilogue represented as 14 distinct scenes (Table 3). We were able to identify each new scene arising at the point of a significant incident in the handover discussion.

|

Act |

Scene number |

Scene name |

Major theme of scene |

Description of scene |

Actors with VOT within scene |

|

Prologue. |

1 |

“Nice to meet you.” |

Setting the scene. |

First four handover members arrive (P3, P12, P13, P14). New SHO arrives (P6) and receives brief orientation. Remaining handover members arrive (P1, P2, P4, P5, P7, P9, P10, P11). Meet member of research team (Ob 1). |

P3, P6, P12, P13, P14, Ob 1 |

|

Act 1 – The beginning of handover. |

2 |

“Can we just get going?” |

Introductions. |

Each member of team states their name and role. |

P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P9, P10, P11, P12, P13, P14 |

|

3 |

“Fire away!” |

Start of night handover. |

Lead consultant (P13) initiates handover. Night SHO (P2) utilises handover sheet as a prompt to discuss cases encountered during the night. P8 enters room. |

P2, P8, P13 |

|

|

4 |

“Patient 21, a baby.” |

Focus on a sick child. |

Case of specific child who deteriorated during the night presented, becoming a significant aspect of discussion. Four most senior members of the team (P3, P8, P9, P13) contribute to this discussion. P15 enters room. P2 completes handover of relevant patients, exits thereafter. |

P1, P2, P3, P8, P9, P13 |

|

|

Act 2 – Educational moments and the climax.

|

5 |

“Can I just interrupt?” |

Planning for assessment. |

Consultant (P8) requests patients for examination purposes (principal reason for P8 attending handover), exits thereafter. |

P8, P13 |

|

6 |

“What other things would you like to tell us?” |

Educational moment arising from handover. |

Consultant (P9) presents case of a specific child with alleged non accidental injury, with subsequent educational moment (P13 and P9 acting as prompts for discussion and sources of information respectively). |

P1, P4, P9, P13, P14 |

|

|

7 |

“Is there any learning for us from that one?” |

Further educational moment. |

Lengthy discussion focussed around a ‘difficult’ case. Consultant (P13) uses words “And herein is the learning”, stands up and uses whiteboard to discuss differentials and poses questions to individual team members. P9 serves as a source of clinical information. On-call SHO phone rings and SHO (P5) exits room, followed by senior registrar (P3) from whom help is sought. P9 exits room. |

P1, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P9, P10, P11, P12, P13, P14, P15 |

|

|

8 |

“I will need to divide them up.” |

Focus on workload for patients on inpatient ward. |

Resumption of systematically working through inpatients on the handover sheet to generate management plans, with input obtained from residents and students who had seen children the previous day. |

P1, P3, P7, P13 |

|

|

9 |

“Just been phoned from ED!” |

Dramatic intervention – a sick child in the Emergency Department (ED). |

Interruption of handover to discuss a seriously unwell child who requires specialist attention in ED (climax). P13 states: “Emergent patient care always takes priority”. Lead consultant (P13) exits with on-call SHO (P5). |

P1, P3, P5, P13, P14 |

|

|

Act 3 – The business end of handover. |

10 |

“So, shall we go back up to …?” |

Focus on workload for patients on inpatient ward. |

Resumption of systematically working through inpatients on the handover sheet to generate management plans, with input obtained from residents and students who had seen children the previous day. Senior registrar (P3) now leads the handover discussion with regular, brief contributions. |

P1, P3, P7, P11, P14 |

|

11 |

“OK. Umm and SCBU…” |

Focus on workload for neonates in the Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU). |

Systematic working through SCBU patients on the handover sheet to generate management plans, with input obtained from residents and students who had seen children the previous day. |

P3, P7, P14 |

|

|

12 |

“And then… chase results.” |

Focus on chasing up outstanding laboratory results. |

Systematic working through patients on handover sheet who have outstanding laboratory results to be followed up. |

P1, P3, P7, P14 |

|

|

Epilogue. |

13 |

“So, what are you doing now?” |

Discussion about participants’ day plans. |

Senior registrar (P3) checks with members of team their understanding of their roles for the day. |

P1, P3, P4, P6, P7 |

|

14 |

“Yeah, sweet… done!” |

Conclusion. |

Completion of handover as evidenced by verbal and body language cues as members of team exit the room. |

P3 |

Table 3: Acts and scenes within the handover

2) Entrances and exits: Easily demarcated entrance and exit points of the handover were identified. P1 arrived 5 minutes before the handover commenced, prepared the computer, and then left and returned with the remainder of the handover team. This initial entrance represented the entire group arriving, with a prologue consisting of set up and early introductions (Scene 1).

An example of a dramatic exit and re-entrance of two doctors (P3, P5) was noted during Scenes 7 and 9, which proved to be a major incident, as the phone call off-stage notified them of a critical case. Following this, the lead consultant (P13) exited with a SHO (P5) and the director role was handed to the senior registrar (P3). This altered the handover significantly and came at a time when the handover had moved from a largely educational milieu to a more work-like role.

See Figure 2 for a time-line regarding the Handover.

Figure 2: Timeline of acts, scenes and selected events

3) Additional observations: Multiple data collection methods enhanced the dramaturgical method, through clarifying inaudible audio data. Entrances and exits did not always prompt comments on the audio recording, but were noted from the video recordings. A critical incident occurred when the lead consultant established an educational role and used the whiteboard for teaching – the impact of this would not have been so apparent without a video recording.

IV. DISCUSSION

The studied handover was attended by multiple professionals and students, and had several purposes, focussing on the safe exchange of knowledge and responsibility for a group of patients with variable clinical conditions and acuity (Australian Medical Association Limited, 2006; Hilligoss & Cohen, 2011). We argued that the dramaturgical approach would be a valuable method for analysing the dynamics of this handover. To evaluate the effectiveness of this research approach, we focussed on the feasibility, functionality and quality of the dramaturgy approach.

A. Feasibility

The dramaturgical perspective argues that individuals “play different roles as ‘actors’ and engage in ‘performances’ in order to shape their ‘definition of the situation’” (Canary et al., 2008, p. 155). We applied the metaphor of ‘life as drama’ to this handover. The findings and information gleaned from this handover demonstrated that a dramaturgy approach embedded within a case study methodology can be applied to a complex team handover.

Obtaining consent from all handover attendees in a manner that did not impact on the handover itself required significant pre-planning by the research team and cooperation from the department. In their systematic review, Flory and Emanuel (2004) examined methods for improving the consent process and for increasing participant understanding. One recommendation centred on employing significant person-to-person contact as an optimal method to improve understanding. To avoid undue power dynamics, a senior consultant at this hospital involved in the study was not involved in the administrative process, and this prevented any direct involvement in the recruitment and data collection processes, thus minimising inducement and conflict of interest.

Patients are often particularly vulnerable in this type of research, as they may not fully understand their legal or ethical rights (Sankar et al., 2003). We were cognisant of this when considering our research design. To maintain confidentiality of patients, we de-identified patient details, using a numbering system and only referred to patients by their number code to minimise release of personal medical information.

We established that the dramaturgical approach was able to feasibly capture both verbal and non-verbal elements of the discourse. To capture this wide range of information, we used multiple methods of data collection creating greater accuracy of the handover. Other studies have used different research approaches. Using grounded theory and content analysis, Behara et al. (2005) studied five North American Emergency Departments using ethnographic observations, and emphasised the active participation of handover members in co-construction of their understanding about the patients who were considered in the handover. The use of ethnographic observation has some resonance with this study, although, in this study, we created an ‘a priori’ framework for analysis using the dramaturgical components. The dramaturgical method allowed us to structure our analysis. Several researchers (Donnelly et al., 2019; Ooi et al., 2020) have used inductive techniques to analyse semi-structured interview data, and these studies provided useful perceptions of team handovers in New Zealand hospitals. The advantage of using interviews is that professionals interviewed have time to reflect on the salient aspects of the handover; however, a disadvantage is that the interviewees can censor and forget key elements of the process.

B. Functionality

In this section, we address the second research question focussed on describing the functional dynamics of the handover.

We found that dramaturgical methods provided a useful lens to analyse the way the actors and their roles interacted with the staging. For example, the handover was clearly orchestrated by designated and perceived roles of the lead actor (P13) and the major support actor (P3). Our method of utilising VOT allowed us to evaluate the reasons why some actors within the handover participated more or less, with findings clearly showing that the handover was directed by P13, until she left the room and then P3 became the dominant driver of the performance. This finding is consistent with the work of Donnelly, who described the critical nature of the team handover leader’s role in ensuring safe and equitable outcomes for patients by “running meetings smoothly and respectfully” (Donnelly et al., 2019, p. 611).

The interruption caused by the critical case in Scene 9 highlighted the importance of patient safety and care in handover function (Australian Medical Association Limited, 2006), which took priority over ensuring equal voice contribution of the handover attendees. The impact of handover members having differing levels of clinical experience within a team has been noted as an important contributor to handover dynamics (Behara et al., 2005; Hilligoss & Cohen, 2011). We documented a degree of audience segregation (Canary et al., 2008; Murphy, 2009) within the handover, in that, within specific scenes, some actors were markedly involved, whilst others, particularly the bit actors, were effectively the audience and were relatively uninvolved unless prompted by the director or major support actor.

The video analysis permitted us to regard this handover as more akin to an unscripted improvisation (Sawyer, 2004; Schryer et al., 2003) based on the handover sheet. Hilligoss and Cohen (2011, p. 95) have described handovers as “routines grounded in human memory for habits”, and the handover sheet provided a routine document to be worked through. The dramaturgical framework allowed us to visually consider the layout of the room (or stage) (Goffman, 1959; Murphy, 2009). Kinahan (2017), in her qualitative analysis of seating positions within an educational context, reported that different seating positions likely yield different outcomes. The horseshoe-formation structure used in this handover likely promoted more participant engagement.

Lastly, the dramaturgical approach allowed us to segment the analysis in terms of acts and scenes (Henderson, 2005). This was useful as it allowed us to determine if there were specific activity patterns or key events arising within this handover. Hilligoss and Cohen (2011, p. 95) stated that research “examines how micro patterns of activity in [handover] are embedded in, shaped by, and ultimately produce effects on the larger system of hospital activities”. The handover had a prologue in which members had a brief period of social contact, an important element of handover (Hilligoss & Cohen, 2011; Nugus et al., 2017) which initiates formalising the community of practice (Bradley et al., 2018; Egan & Jaye, 2009).