Enhancing the student experience through sustainable Communities of Practice

Submitted: 29 March 2021

Accepted: 28 September 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 102-105

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/SC2508

Mairi Scott & Susie Schofield

Centre for Medical Education (CME), School of Medicine, University of Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom

Abstract

Introduction: The switch to online off-campus teaching for universities worldwide due to COVID-19 will transform into more sustainable and predictable delivery models where virtual and local student contact will continue to be combined. Institutions must do more to replace the full student experience and benefits of learners and educators being together.

Methods: Our centre has been delivering distance blended and online learning for more than 40 years and has over 4000 alumni across five continents. Our students and alumni come from varied healthcare disciplines and are at different stages of their career as educators and practitioners. Whilst studying on the programme students work together flexibly in randomly arranged peer groups designed to allow the establishment of Communities of Practice (CoP) through the use of online Discussion Boards.

Results: We found Discussion Boards encouraged reflection on learning, sharing of ideas with peers and tutors, reduce anxiety, support progression, and enable benchmarking. This led to a highly effective student sense of belonging to each other, our educators, and the wider University, with many highlighting an excellent student experience and maintaining a thriving CoP within the alumni body.

Conclusion: Despite being based on one large postgraduate programme in medical education, our CoP approach is relevant to any undergraduate programme, particularly those that lead to professional qualification. With our mix of nationalities, we can ‘model the way’ for enabling strong CoP’s to share ideas about best practice with a strong student and alumni network which can be shared across the international healthcare community.

Keywords: Communities of Practice, Sense of Belonging, Student Experience

I. INTRODUCTION

The sudden switch to online, dual delivery and on-campus/off-campus teaching for Universities worldwide will not be reversed at the end of the current COVID-19 crisis but will transform into a more sustainable and predictable delivery model where virtual and local student contact will continue to be combined. The switch, known as Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al., 2020) achieved much in a short timeframe but institutions need to do more to truly replace the full student experience and benefits of learners and educators being together on-site. The need for this new approach is acute in professional-based courses such as medicine where students need to learn complex skills within the context of healthcare delivery. These skills are acquired through multiple interactions with clinical colleagues in the workplace which, although often brief, are focused in real-time.

Given that the learning environment is dependent on the institutional ‘personality, spirit, and culture’ (Holt & Roff, 2004, pp. 553), human interaction is necessary to create that culture. We must develop new approaches to delivering medical education by merging established educational technologies with virtual approaches to establish on-line interaction with peers and senior colleagues such as can be achieved in Communities of Practice (CoPs) (Lave & Wenger, 1991). CoPs are social structures where people can share ideas, stories, and experiences relevant to the community’s activities. They help participants make sense of new knowledge and enable novices to benefit from working with experts, thus reducing anxiety, supporting progression, and enabling benchmarking. These components lead to the creation of a rich environment for information-sharing which has become increasingly important within healthcare delivery organisations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We have built on over 40 years’ experience of delivering distance, blended and online Masters-level accredited medical education learning across five continents to ‘model the way’ to providing a strong student experience for online learners. Our students and alumni come from various interdisciplinary healthcare disciplines, at different stages of their career as educators and practitioners.

II. METHODS

Several Discussion Boards (DBs), usually one per study week plus one for assignment questions are created in each 12-week Moodle-based module. Students are randomly assigned to groups to work together flexibly within these peer groups. Each discussion has a ‘prompt’ linked to that week’s work, designed to create CoPs and a highly effective student sense of belonging (SoB) to each other and programme educators. In the first module students are actively encouraged to participate, with emphasis being on the ‘safe space’ created that allows them to learn effectively from and with each other. DB comments are used as part of programme enhancement and quality assurance. Students give informed consent to their evaluation comments within DBs being extracted for overall programme review.

III. RESULTS

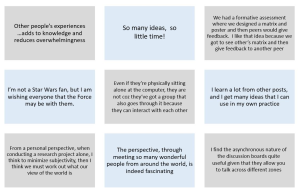

As students move from legitimate peripheral participant to experienced member, they often express increased confidence that their posts will allow them to share their view and help colleagues. The forum posts have been analysed as part of a much larger study; the following diagram (Figure 1) highlights some of the benefits.

Figure 1. Sample of comments in DBs posts

Our experience over the last four years is that student levels of interaction increase the further into the programme they go, suggesting that they value and enjoy it. Overall, when asked specifically if that assumption is correct, feedback from students is exceptionally positive and they comment on their achievement of a SoB through engagement with the DBs. Many highlight the excellent student experience. Another indirect indication of success is that student module success rate averages 93% across the modules, which is high for an online learning programme.

The benefits of using DBs are threefold:

- They allow for reflection on learning in real-time due to regular module-specific weekly activities requiring students to reflect on that week’s educational materials and post their thoughts on the DBs.

- They allow sharing with peers and tutors, establishing CoPs: The DB posts create peer-to-peer dialogue, encouraging students to practise the language of the discipline in a safe, supported environment. Learning activities are based on the principle of linking previous experience with the interpretation of new knowledge, thus enabling an escalation of the complexity of questions to enhance deeper connection and dialogue. Although essentially (and importantly) it is the students as peers who are encouraged to respond to each other’s questions and comments, the tutors do monitor posts, providing input when necessary and desirable. In some modules, students are required to give peer feedback on draft assignments using a 1:4 ratio to encourage a range of views and expertise, increasing the depth and extent of their critical thinking and analysis. This also gives them practice in giving and receiving feedback, an essential skill for future medical educators.

- CoPs build trust in colleagues and a SoB within the learning environment, leading to an excellent learning experience. Students state that they value the tutor contribution as this increases the confidence they have in their own online comments, sometimes shifting the discussion to a more profitable area for new learning in a way that was not pre-planned or even at times expected.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our approach to the creation of CoPs is based on the principle that in order to establish student trust and a SoB DBs are an essential tool. Management research describes trust within organisations as being multifaceted, with the main components being capability, well-meaning intent, and integrity (Ridings et al., 2002). It is accepted that within our programmes both tutor and student capabilities have been established. Integrity is established by clearly explaining the expected mode of student behaviour at the outset and demonstrated as students work through the programme. Well-meaning intent is demonstrated by acts of positive reciprocation built up over time by asking students to give peer feedback frequently and around increasingly complex activities. Both integrity and well-meaning intent therefore need to have a continued focus during module design and delivery and throughout the assessment process.

Now that medical education has been forced to re-evaluate the place of online learning as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis, it seems inevitable that many of the discovered benefits will lead to significant changes in the way we teach and learn. Davis (2018) explored a future medical school being one ‘without walls’ by which he meant that the artificial separation of the ‘classroom and the clinic’ would inevitably diminish as we embraced flipped classrooms and online collaborative learning.

If we adopt this approach for student learning it may also change the way we think about faculty development, as we could create extensive networks of faculty development special interest grouped CoPs beyond the ‘walls’ of our own schools. A recent study by Chan et al. (2018) in McMaster describes the creation of a Faculty Incubator – a virtual CoP which uses a longitudinal, asynchronous, online platform to deliver a one-year curriculum to support early-to mid-career educators from 30 different locations with their professional development. This widespread (geographically) collaborative approach was found to be well received, with lively interactions which broke down some of the boundaries that normally prevent early career academics from approaching unknown colleagues in different locations, colleagues they would normally never have met in person.

An additional challenge created by the COVID-19 pandemic was the necessity for healthcare professionals to make clinical decisions in an ‘evidence-poor’ disease by gathering emerging data (often by word-of-mouth) and treating patients without the certainty of a knowledge base built up over decades of robust randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence. This is described by Rosenquist (2021, pp. 8) as a kind of “Bayesian fatigue”: a stress-induced dysphoria experienced when the corpus of knowledge that is the foundation of one’s work acquired over decades, becomes less important than information being gathered from disparate sources in real time.’ The ‘disparate sources’ referred to here are groups of widely dispersed practitioners (within current and new CoPs) who are sharing individual and collective rapid learning by experience that has become necessary when treating patients with COVID-19. These CoPs are based on the collective trust healthcare professionals express in valuing the views of colleagues struggling with similar challenges. This helps reduce that ‘Bayesian’ impact when it comes to making difficult clinical decisions in real time with limited evidence. However, trust within a CoP also comes from previous positive experience of being within other CoPs, and so it is important that we as medical educators enable our students to have experience of the value of sustainable CoPs in their own learning. Despite the limitations of the range of the study comments, we believe that given the extent of the sudden switch to ERT our findings of use of DBs to establish much appreciated CoPs justifies early dissemination through this short communication.

V. CONCLUSION

As medical educators we must have the skills necessary to establish strong and sustainable CoPs to educate current and future healthcare professionals in this effective way of learning from each other. This can be done as effectively with online learning as with on-campus interaction, allowing the possibility of the widespread creation of truly effective international CoPs sustainable for years to come.

Notes on Contributors

Professor Mairi Scott reviewed the literature, selected the data, wrote the manuscript, created the presentation and presented the materials virtually to the Conference. Dr Susie Schofield reviewed the literature, advised on the selection of the data and gave critical feedback on the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approved was granted by School of Medicine & School of Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 4HN on 03/05/19. Application Number: 19/41.

Data Availability

Ethical approval specified that raw data would not be made available for others out with the Centre ‘beyond the anonymised published or reported versions within the dissemination strategy’.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Thillainathan Sathaananthan (PhD student) and Dr Linda Jones (PhD supervisor, Senior Lecturer) CME, University of Dundee, who produced some of the outcomes as part of research into student experiences with online learning and the use of Discussion Boards.

Funding

No grant or external funding was received for this work.

Declaration of Interest

Both authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Chan, T. M., Gottlieb, M., Sherbino, J., Cooney, R., Boysen-Osborn, M., Swaminathan, A., Ankel, F., & Yarris, L. M. (2018). The ALiEM faculty incubator: A novel online approach to faculty development in education scholarship. Academic Medicine, 93(10), 1497–1502. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002309

Davis, D. (2018). The medical school without walls: Reflections on the future of medical education. Medical Teacher, 40(10), 1004–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1507263

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/%20articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Holt, M. C., & Roff, S. (2004). Development and validation of the Anaesthetic Theatre Educational Environment Measure (ATEEM). Medical Teacher, 26(6), 553-558. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001711599

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Ridings, C. M., Gefen, D., & Arinze, B. (2002). Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities: The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(3-4), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-8687(02)00021-5

Rosenquist, J. N. (2021). The stress of Bayesian medicine—Uncomfortable uncertainty in the face of COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(1), 7-9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018857

*Mairi Scott

Centre for Medical Education,

University of Dundee

Email: m.z.scott@dundee.ac.uk

Submitted: 3 June 2021

Accepted: 4 October 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 76-86

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/OA2547

Nadia Greviana1,2, Dewi Anggraeni Kusumoningrum2, Ardi Findyartini1,2, Chaina Hanum1 & Garry Soloan1,3

1Medical Education Center, Indonesian Medical Education & Research Institute (IMERI) Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 2Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 3Undergraduate Program in Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction: As significant autonomy is given in a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), online self-regulated learning (SRL) ability is crucial in such courses. We aim to measure the online SRL abilities of early-career medical doctors enrolled in a MOOC.

Methods: We performed a cross-sectional study using the Self-Regulated Online Learning Questionnaire-revised version (SOL-Qr). We conducted a three-stage cross-cultural validation of the SOL-Qr, followed by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The online SRL ability of 5,432 medical doctors enrolled in a MOOC was measured using the validated SOL-Qr.

Results: The CFA of the cross-translated SOL-Qr confirmed its comparability to the original version, with excellent validity & reliability. Participants showed high levels of online SRL during their early careers. Despite high online SRL scores, MOOC completion rate was low. Male participants showed slightly better time management ability than female participants. Participants working in the primary epicentrum for COVID-19 in the country showed lower online SRL scores, while participants who graduated from higher accreditation levels showed better time management ability.

Conclusion: The SOL-Qr and its subscales are suitable and valid for measuring the online SRL abilities of medical doctors in a MOOC during their early-career period. Time management ability was associated with previous experience during the medical education period, while other online SRL subscales were mostly associated with workload. However, as the scores did not correlate with the time spent for learning in MOOC, the corresponding learning effort or time spent may be beyond just the commitment to the described MOOC.

Keywords: Self-Regulated Learning, MOOC, Online Learning

Practice Highlights

- It is important to take into account learners’ online SRL ability in MOOCs as it is dynamic across online learning contexts.

- The use of the SOL-Qr is beneficial for providing learners’ online SRL profiles in MOOC during medical doctors’ early career period.

- Understanding online SRL abilities helps MOOC developers to evaluate learning activities in MOOC and support learners’ online SRL ability.

I. INTRODUCTION

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are open academic platforms in which students can access learning resources interactively. The self-paced nature of MOOCs provides time-flexibility, facilitating deeper learning (Bullock & De Jong, 2013). MOOCs are useful for replacing direct interaction for knowledge transfer and learning processes during the ongoing pandemic because they utilise various formats, such as video lectures, reading resources, assignments, tests, and asynchronous discussion within the platform (Sandars & Patel, 2020). Because MOOC’s aim to give learners useful resources and empower teachers to provide vital knowledge, curation of the platform, with its copious information, it is beneficial for achieving high-quality content that fits the learning objectives and learners’ characteristics (Asarbakhsh & Sandars, 2013). As demand for technological solutions in education rise during the COVID-19 pandemic, MOOCs have been promoted as forms of disruption that accelerate adaptation to balance safety with the achievement of competencies by medical students and graduates (Hall et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020).

MOOCs have generally been designed as open in access, location, pace, and time of completion; therefore, learners must control their learning process. Learning goals are usually set less strictly in MOOCs than in other courses. Unlike traditional, face-to-face teaching, MOOCs require highly engaged & strategic students. Learners must plan their study, set goals, evaluate their knowledge related to the course material, adapt their learning strategies, and assess their performance. They are solely responsible for managing their time and study environment (Jansen et al., 2017).

With high enrollment rates, the majority of learners fail to complete MOOCs, for various reasons: lack of time, insufficient prior knowledge, inadequate supervision, and difficulties in understanding the course materials (Hew & Cheung, 2014). Time management, effort regulation, metacognition, and critical thinking as part of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) relate to success in online academic activities (Broadbent & Poon, 2015). Because MOOCs give students significant autonomy in completing the course, SRL is crucial for successful completion of MOOCs (Chung, 2015; Wong et al., 2018).

SRL encompasses a student’s ability to actively and constructively control their thoughts, acts, and emotions towards learning objectives (Jouhari et al., 2015), using the cycle of forethought, performance, and self-reflection phases, which should be implemented in an online learning environment (Panadero, 2017). Various external factors may interplay and affect self-regulated learning among students. This underscores the importance of a supportive family, helpful peers, and motivational, feedback-centered instruction methods; together, these factors support SRL (Jouhari et al., 2015).

Virtanen and Nevgi (2010) recognised gender as a factor affecting how SRL is perceived by students, especially during the forethought stage; they found that male students scored slightly higher on the sub-scale for self-efficacy, while female students demonstrated greater help-seeking strategies, performance anxiety, and beliefs in the value of studying. Bembenutty (2009) also found that female students perceive learning as a more valuable task in SRL than male students do.

Several instruments were developed to measure SRL, including structured interviews like the Self-Regulation Interview Schedule (SRLIS), questionnaires, teachers’ judgments, think-aloud techniques, and performance observations (Magno, 2011). The Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) is a common measure of SRL. It assesses two aspects: motivational orientation—encompassing values, expectations, and affective components—and the use of different learning strategies, e.g. cognitive and metacognitive strategies or resource management strategies (Pintrich et al., 1993). Another instrument for measuring students’ SRL in higher education is the Academic Self-Regulated Learning Scale (A-SRL-S), evaluating memory strategy, goal-setting, self-evaluation, seeking assistance, environmental structuring, learning responsibility, and planning and organising (Magno, 2011).

In the context of online learning, several instruments have been developed to measure students’ SRL, such as the Online Self-regulated Learning Questionnaire (OSLQ) and the Self-regulated Online Learning Questionnaire (SOL-Q). The OSLQ consists of six subscales: environment structuring, goal-setting, time management, help-seeking, task strategies, and self-evaluation (Barnard et al., 2009). However, this questionnaire cannot measure SRL activities in the appraisal or self-reflection phase. Meanwhile, the SOL-Q was developed by Jansen et al. (2017), using other existing SRL questionnaires to measure SRL activities, specifically in MOOCs, for all three SRL phases: preparatory, performance, and appraisal. The SOL-Q consists of five sub-scales: metacognitive skills, environmental structuring, help-seeking, time management, and persistence (Jansen et al., 2017). In 2018, a revision was made to split the metacognitive skills scale into three subscales: metacognitive activities before, during, and after a learning task. The revised questionnaire (SOL-Qr) demonstrated improved validity, usability, and reliability (Jansen et al., 2018).

Recognising the importance of learners’ during the use of MOOCs—and that SRL is affected by various factors—we attempted to measure the online self-regulated learning of early-career medical doctors enrolled in a MOOC that provides essential knowledge about COVID-19 to support medical doctors’ early careers during the COVID-19 pandemic. We seek to answer the following questions in this study:

- Is the Self-Regulated Online Learning Question (SOL-Qr) valid for use in our setting?

- What is the profile of students’ SRL scores, and are there any relationships between the SRL score, course completion, gender, respondents’ former medical school, and internship location

II. METHODS

A. Context

With approximately 270 million inhabitants across 34 provinces, Indonesia is one of the largest archipelagos in the world. According to a recent report, there is one medical doctor per 2500 people across the country (National Ministry of Health, 2020). Recently graduated medical doctors must undergo a one-year compulsory internship program upon graduation, where they serve as front-liners in primary health care settings across the country to serve in societies in very diverse sociocultural contexts and ethnicities. Those who graduated in 2020, mostly finished high school and entered medical schools in 2013–2014, completed their clinical stages and graduated from different medical schools in Indonesia at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which some of the clinical duties in teaching hospitals were suspended and amended for safety reasons (Findyartini et al., 2020). A total of 93 public and private medical schools are distributed across Indonesia, all accredited by the National Accreditation Agency for Higher Education in Health with A-level as the highest accreditation indicating that the medical school has reached an established quality in teaching-learning processes and faculty members.

Considering the need for the newly graduated medical doctors serving as front liners to learn about the current pandemic situation and the importance of safety for both patients and healthcare workers, the Ministry of Health equipped these new graduates with essential COVID-19 knowledge before their involvement in patient management during the ongoing pandemic. Given the geographical reality of the country’s archipelago and the nature of the workplace setting during the internship program, the use of a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) was preferred.

Little was known about COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic. Guidelines created by organisations (such as the CDC and WHO) are mostly amended living documents based on newly published articles, data, and clinical expertise. Studies on COVID-19 are being conducted on a massive scale worldwide, which may create information overload and overwhelm learners, especially those serving as front–liners (Poonia & Rajasekaran, 2020). A MOOC approach would facilitate a prompt response for equipping medical and health students, professionals, and the broader community to learn about the pandemic situation and prepare them to contribute to the pandemic response in community and hospital settings (Ortiz-Martìnez et al., 2021).

B. The COVID-19 MOOC Description

All internship doctors in Indonesia batch 3 and 4 in 2020, were compulsorily enrolled in an open course on COVID-19 at the beginning of their internship period. The open course was sequenced into two, sequentially accessed parts. The mandatory part A consists of fundamental knowledge on COVID-19 (such as COVID-19 screening, triage, infection control, management of patients, preventive strategy, etc); Part B consists of supplemental knowledge about COVID-19 (such as management of patients with comorbidity, ethics, and medicolegal aspects, perioperative management, etc); it is optional for participants to choose which topics to learn based on their interests and needs. Participants were encouraged to complete Part A during the first two weeks of their internship program to ensure sufficient knowledge before their service. However, participants were given full access to revisit the MOOC for up to 9–12 months of their internship programs. More details on the online course are reported elsewhere (Findyartini et al., 2021).

C. Study Design and Instruments

Our cross-sectional study uses the SOL-Qr (Jansen et al., 2018), which was adapted to Bahasa Indonesia, to assess online self-regulated learning ability in a Massive Open Online Course. Secondary data were obtained from the Moodle-based MOOC platform, including the total number of respondents, gender, internship location, former medical school, and course completion.

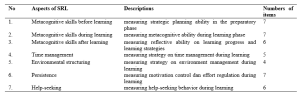

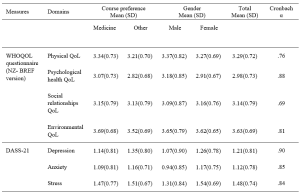

SOL-Qr measures seven aspects of SRL as mentioned in Table 1. Respondents answer each item on a 7-point Likert scale (1 for “not at all true for me” and 7 for “very true for me”). This questionnaire was translated to Bahasa Indonesia and back-translated to English to ensure similarity in meaning. Cognitive interviews with four respondents resembling the study participants were also conducted to obtain clarity of the items. The two respondents in this phase were final year medical school students from the authors’ institution (prospective participants of the national internship program) and the other two respondents were medical doctors who have just completed the national internship program.

Table 1. Descriptions of SOL-Qr (Jansen et al., 2018)

Course completion, as analysed in this study, refers to the completion rate (in percentage) of the optional topics in part B that were accessed and completed by study participants in the open course.

D. Data Collection

Data were collected from the Moodle-based MOOC platform of the COVID-19 module from January to February 2021, two months after each course had started. This study uses a total sampling approach, with a minimum sample size of 204 respondents, calculated from standard deviation of 3.43 (Yen et al., 2016) and alpha (type I error) of 0.05 and beta (type II error) of 0.20 and 10% estimated drop out level.

All study participants were National Internship Medical Doctors in the year 2020 who were enrolled in the COVID-19 Open Course on the MOOC platform.

The SOL-Qr questionnaire was embedded in the evaluation questionnaire placed at the end of Part A, before participants moved forward to Part B. The questionnaire was completed voluntarily by participants who agreed to participate in this study. They were given adequate written information about the study and assured that there were no consequences of participation in regards to the course or the internship program evaluation. All data included in this study were collected from participants who signed and agreed upon the written consent embedded in the questionnaire. This study obtained ethical clearance from Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia/ dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital Research Ethics Committee Board (KET-1395/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2020) in 2020.

E. Data Analysis

We conducted a three-stage validation process for the SOL-Qr, including the process of translation to Bahasa Indonesia by the research investigator, the back-translation process, and a review process by four newly graduated medical doctors who represented the characteristics of the study participants. This process ensured that the Bahasa Indonesia version of SOL-Qr was comparable to the original version. Furthermore, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to confirm the model proposed by Jansen et al. (2018) as a fit model in the Bahasa Indonesia version compared to the original version. The fit model of CFA analysis determined whether normality, multicollinearity, residual values, and multivariate outliers were met. Furthermore, the Two-Index Presentation Strategy, the fit index combination of at least two indicators among the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and the comparative fit index (CFI) all indicated the fit model of CFA analysis (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schreiber et al., 2006). Internal consistency analysis of the Bahasa Indonesia version of SOL-Qr was also completed. Items were concluded as valid if the corrected item-total item correlation value was higher than 0.3. The questionnaire was considered reliable if alpha Cronbach ≥ 0.700; an alpha value higher than 0.900 indicates excellent internal consistency (Blunch, 2008).

All survey data obtained from the questionnaire were statistically analysed using IBM SPSS Statistic version 21. Demographic data were processed using descriptive statistics (proportion, mean, and standard deviation). Study participants were classified into two groups according to their internship location:

- Medical doctors who serve in Java- Bali Region, which was the primary epicenter of COVID-19 in the country in 2020.

- Medical doctors who serve in Outside Java- Bali Region.

We also classified participants according to their former medical school accreditation.

Bivariate analysis using the t-independent test was used to find relationships between the online self-regulated learning scores and gender, internship location, the former medical school, and the course completion. The Pearson correlation test was also used to analyse correlations between online SRL subscales and the course completion rate.

III. RESULTS

A. Validation of the SOL-Qr

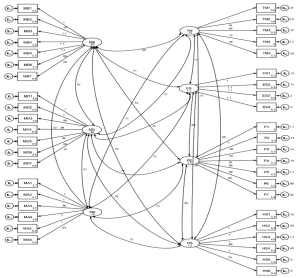

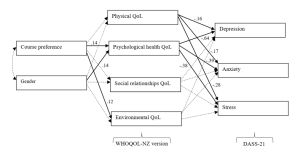

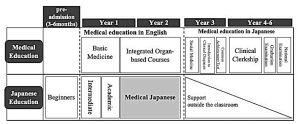

The three stages of validation were conducted in the SOL-Qr instrument to ensure the content validity of the Bahasa Indonesia version of SOL-Qr. CFA was performed on the Bahasa Indonesia version of SOL-Qr, with the results showing the goodness-of-fit according to Hu and Bentler’s Two Index Presentation; the SRMR value was 0.056 (<0.08) while RMSEA value was 0.078 (<0.08). Meanwhile, the χ2/df value was < 0.001; the CFI value was 0.874 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The model (Figure 1) also confirms the comparability of the subscales to the original SOL-Qr.

The Bahasa Indonesia version of SOL-Qr also shows excellent validity and reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.974. The reliability of each subscale ranges from 0.971 to 0.975.

Figure 1. CFA results of the National Language Version of SOL-Qr (MB: Metacognitive Before, MD: Metacognitive During, MA: Metacognitive After, TM: Time Management, ES: Environmental Structuring, P: Persistence, and HS: Help Seeking)

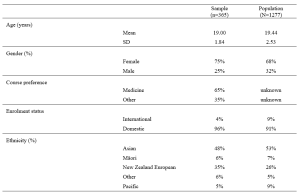

B. Profile of Participants’ Online SRL Scores

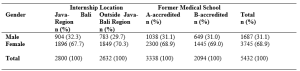

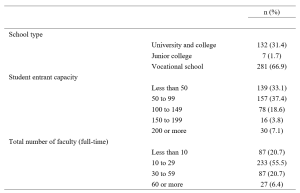

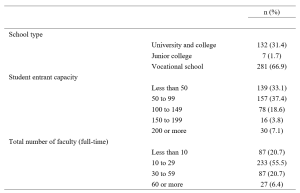

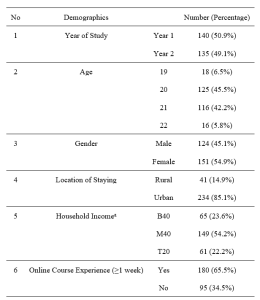

A total of 5,846 internship doctors from all 34 provinces in Indonesia were enrolled and accessed the MOOC; as many as 5,432 participants, graduated from 74 medical schools (of which 46% are A-accredited while 54% are B-accredited), agreed to participate in the study (response rate of 92.9%). Details on the study participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Study participants (N = 5,432)

C. Relationship Between Online SRL Score, Course Completion, Gender, and Internship Location

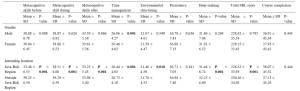

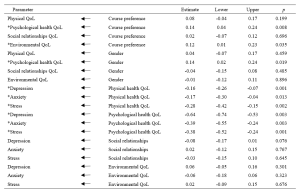

Data on the online SRL scores and course completion were analysed according to gender, internship location, and medical school accreditation. The data are described in means and standard deviations, as they were normally distributed, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Profile of online SRL and course completion according to gender, internship location, and medical school

According to Table 3, the average total scores of participants’ online self-regulated learning in all groups show high levels of online SRL (SRL score > 5). When comparing the male and female participants, the finding suggests that only the Time Management subscale shows a significant difference (p = 0.001). Male participants show higher scores in time management than female participants. Participants from the Outside Java-Bali Region had significantly higher online SRL scores in all subscales, except for the Persistence subscale (p = 0.181), than participants from the Java-Bali Region, which was the primary epicenter of COVID-19 in the country.

Meanwhile, the online SRL scores of participants who graduated from A-level versus B-level accredited medical schools mostly show similar online self-regulated learning scores, except in the time management scale (p = 0.009).

Although Table 3 shows no significant difference regarding course completion across gender, internship region, or former internship location, it does show a low course completion rate. Participants only completed less than approximately 40% of all optional topics in Part B.

The results of the Pearson correlation test show significant differences between the course completion rate and several SRL subscales, with very low correlation values (r < 0.1 in all subscales) for the SOL-Qr in the whole samples, as well as between the internship location and former medical education groups. Only the Time Management score was correlated to Course Completion in the Outside Java-Bali group, with a very low correlation value (r = 0.102). Therefore, the course completion rate does not correlate with the online SRL scores.

IV. DISCUSSION

Self-regulated learning is a dynamic process and may change while learners undergo various learning contexts (Barnard et al., 2009). The rapidly changing pandemic has accelerated the adaptation of new learning approaches and methods worldwide, including MOOCs that had gained popularity. Therefore, the use of the SOL-Qr is beneficial for providing MOOC learners’ SRL profiles (Jansen et al., 2018).

This study represents the first successful attempt to cross-culturally validate the SOL-Qr and determine the suitability of all its subscales for profiling online SRL of medical doctors in their early career. The three-stage validation process for the SOL-Qr was conducted as a form of cross-cultural adaptation of the instrument to facilitate its use in measuring self-regulated learning abilities in an online setting in the context of medical education—specifically in the MOOC used for continuing medical education and professional development programs for early-career, newly graduated medical doctors (Hambleton, 2005). The CFA conducted in this study also demonstrates a good fit, with excellent internal consistencies of the SOL-Qr and its subscales; this demonstrates the comparability of the instrument with the original SOL-Qr (Jansen et al., 2018).

The use of the SOL-Qr in this study demonstrates online SRL abilities during the transition phase in the early careers of medical doctors, from medical students to medical interns. This study demonstrates the high average level of online SRL ability among newly graduated medical doctors (SRL score > 5). Participants’ online SRL may increase due to the positive online learning experience obtained, considering that the knowledge on COVID-19 provided in this particular MOOC was vital and timely knowledge for these recent graduates. While participant perceptions of MOOCs have been reported elsewhere, it is known that positive perceptions of an online learning experience and environments are significantly correlated with the online SRL score (Abouzeid et al., 2021; Findyartini et al., 2020; Liaw & Huang, 2013).

The high scores for online SRL in our study were found in total and in most of the subscales, except for the metacognitive skills before learning (MB) scale in participants from the Java-Bali region. A similar finding on the low level of metacognitive ability was reported during the transition phase from preclinical to clinical learning, which was associated with previous clinical experience (Cho et al., 2017). Albeit being assessed using a different instrument, the decreased level of metacognitive skill in this study may also be affected by a similar factor. Since the Java-Bali Region had been the primary epicenter of COVID-19 in the country, with the greatest number of COVID-19 cases (69.41%) out of all other regions (National Ministry of Health, 2021), most interns in the Java-Bali Region may have experienced being removed from their duties at the beginning of the pandemic for safety reasons during their last clinical rotations as medical students (Findyartini et al., 2020). This may have caused discomfort because they felt useless and unable to contribute to patient care, further affecting their sense of competence and motivation, despite previous clinical experiences. Hence, this may have affected the process of goal-setting and reflecting on their prior knowledge during the transition to becoming medical interns (Dornan et al., 2014; Dubé et al., 2015).

Findings of this study demonstrate no significant correlation between online SRL and the number of optional topics achieved by participants. This result was supported by the fact that, despite the high level of online SRL ability depicted in this study, the duration of which participants accessed the compulsory Part A was lower than the expected minimum duration as estimated by course developers although we did not explore whether participants learned about COVID-19 from any other learning resources (Findyartini et al., 2021). The current study also supports the results of a previous study with similar findings regarding online SRL scores and academic achievement, although this study does report a significant relationship between online discussion and academic achievement (Abouzeid et al., 2021). The MOOC examined in this study does not provide two-way interactions among learners or between learners and instructors, which may affect the low number of optional courses completed.

Our study also shows that the online SRL scores of participants in the Outside Java-Bali Region were significantly higher (p < 0.001) across all scales than those of participants in the Java-Bali Region, except on the Persistence scale (p = 0.181). This suggests that participants in the Outside Java-Bali Region also have better time management, environmental structuring, and help-seeking abilities, which may relate to the workload at the internship locations. Participants in the Java-Bali Region face a higher workload and stress as front-liners in managing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic (as health educators, contact tracers, vaccinators, etc.). This aligns with other findings suggesting that an optimal workload determines the quality of students’ SRL in the early transition and adaptation phases (Barbosa et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the MOOC was given to the participants at the beginning of their internship programs, in which several orientations and patient management also took place. Hence, it is confirmed that the participants’ workload affected the time allocated to learn the MOOC (Eriksson et al., 2017). This study also suggests that the use of the MOOC for knowledge provision would preferably occur with sufficient time before immersion in other workplace-based learning experiences.

Hew and Cheung (2014) report few challenges in MOOC completion, including a lack of time and having other priorities to fulfill the course; therefore, time management ability remains crucial. The results of this study indicate that male participants had slightly better time management abilities than female participants. Although the absolute difference of the scores between groups is small, this study involved 5,432 respondents (much more than the minimum sample size), thus small differences in results can be statistically significant. As newly graduated doctors, study participants were interns who worked in a new environment hence new challenges regarding workplace relationships and workload may be faced. Previous studies show that female and male physicians may perceive these challenges differently (Babaria et al., 2009). Female physicians report that they feel uncertain and stressed when facing different clinical environments. Because they tend to need more time to adapt than male physicians (Malau-Aduli et al., 2020), completing a MOOC may not be their priority. Moreover, with masculinity/femininity level of cultural determinant, Indonesians have a clear cut between gender roles, thus affecting roles of female participants in most settings (Mangundjaya, 2013). Female participants may culturally face different roles in their personal lives, such as the expectation to perform housework and childcare, in addition to their internship obligation resulting in conflicting time and higher stress levels. The conflicting time and higher stress level in both work and personal life (Isaac et al., 2013) may influence female participants’ ability to commit time to learn and work and may explain the lower time management scores among female participants.

This study also highlights that, overall, the online SRL scores of participants graduating from the A-level and B-level of accredited medical schools show similar results, except on the time management scale (p = 0.009), where the participants from the higher level accredited schools show higher scores than the participants from the lower level accredited schools. Prior online learning experience has been reported as an important determinant of online learning success (Vilkova, 2019). For newly graduated doctors completing an internship program, prior online learning experience may be largely attributed to the use of online learning formally in their medical school’s curriculum. Our study suggests that the higher accredited medical schools may provide more online learning experiences, leading to better time management skills among the participants from this group. Furthermore, MOOC completion and the fulfillment of learning outcomes were determined by the forethought phase in the students’ SRL; thus, the goal-setting, self-efficacy, and task values should be emphasised by the participants and facilitated by the MOOC (Vilkova, 2019). Our study further indicates that time management in the use of the MOOC should be considered by learners in the forethought, performance, and self-reflection phases of their SRL; the planning stage of the MOOC development must determine the estimated completion time for the whole course and its sections about the course learning outcomes and the participant’s characteristics (Stracke et al., 2018).

Similar to the SRL ability in offline learning, our findings further imply the importance of accounting for learners’ online SRL abilities, which are dynamic across online learning contexts, including MOOCs. Certain characteristics of MOOCs, such as their open access and self-paced nature, stress the importance of online SRL ability, especially for MOOCs used in the transition phase in the early career of medicine. Therefore, using validated and reliable instruments, such as the SOL-Qr, to measure the online SRL abilities of MOOC participants would help course developers to identify whether the online learning context supports or hinders learners’ SRL abilities, thus helping course administrators further improve MOOC to provide further support for learners’ SRL (Barnard et al., 2009; Sandars & Patel, 2020).

V. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

We identify several limitations of this study. As this study examined online SRL ability of participants using a self-reported questionnaire, it was unable to examine the actual online SRL ability, given the poor correlation with the course completion rate. Furthermore, as the evaluation of online SRL was only conducted once, it was not possible to observe changes in SRL ability throughout the use of the MOOC or in a longer period. With the data that we obtained, we were also unable to analyse whether participants used other online resources to learn about COVID-19 before the internship program or parallel with accessing the provided module as the marker of online SRL nor to explain any causal relationships between online SRL scores and the factors under investigation. However, measurement of online SRL ability using the cross-culturally validated SOL-Qr reveals that this instrument can be used for MOOCs on continuing medical education and professional development in the early-career context.

VI. CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates the cross-cultural validity of the SOL-Qr and the suitability of its subscales for use in the medical and health fields. The results portray the online SRL ability of medical doctors as participants in a MOOC during the transition phase in their early career. We found that the time management ability was associated with previous experience during the medical education period, while other subscales were mostly associated with workload during the transition phase. However, as the scores did not correlate with the completion rate of MOOC, it can be concluded that the questionnaire is a possible valid tool to assess self-regulated learning in the MOOC environment. Yet, the corresponding learning effort or completion rate may be beyond just the commitment to the described MOOC.

Notes on Contributors

NG designed and led the study, led data collection and analysis, and led manuscript development. AF, DAK, and CH contributed in data collection, completed data analysis, and contributed to manuscript development. GS contributed in the data analysis and manuscript development. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study obtained ethical clearance from Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia/ dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital (KET-1395/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2020) in 2020.

Data Availability

Data will be available upon request to corresponding author due to conditions of consent provided by respondents in this study and that it should abide data sharing policy from the authors’ institution and the Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia for the trust that has been given to develop and organise the MOOC for the national internship program participants. We would also like to thank all national internship program participants for participation in this study and to Vernonia Yora Saki for assisting the authors with statistical analysis of the study. The preliminary results of this study were presented in Niigata Meeting 2020.

Funding

The development of MOOC and data analysis has been supported by the Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia through a direct appointment decree to our institution.

Declaration of Interest

All authors state no possible conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional, and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Abouzeid, E., O’Rourke, R., El-Wazir, Y., Hassan, N., Ra’oof, R. A., & Roberts, T. (2021). Interactions between learner’s beliefs, behaviour and environment in online learning: Path analysis. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 6(2), 38-47. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-2/OA2338

Asarbakhsh, M., & Sandars, J. (2013). E-learning: The essential usability perspective. The Clinical Teacher, 10(1), 47-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00627.x

Babaria, P., Abedin, S., & Nunez-Smith, M. (2009). The effect of gender on the clinical clerkship experiences of female medical students: Results from a qualitative study. Academic Medicine, 84(7), 859-866. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a8130c

Barbosa, J., Silva, Á., Ferreira, M. A., & Severo, M. (2018). Do reciprocal relationships between academic workload and self-regulated learning predict medical freshmen’s achievement? A longitudinal study on the educational transition from secondary school to medical school. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23, 733-748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-9825-2

Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S.-L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005

Bembenutty, H. (2009). Academic delay of gratification, self-regulation of learning, gender differences, and expectancy-value. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(3), 347-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.028

Blunch, N. J. (2008). Introduction to structural equation modelling using SPSS and AMOS. SAGE.

Broadbent, J., & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007

Bullock, A., & De Jong, P. G. M. (2013). Technology-enhanced learning. In T. Swanwick (Ed.), Understanding medical education: Evidence, theory, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 149-160). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118472361.ch11

Cho, K. K., Marjadi, B., Langendyk, V., & Hu, W. (2017). Medical student changes in self-regulated learning during the transition to the clinical environment. BMC Medical Education, 17(59). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0902-7

Chung, L.-Y. (2015). Exploring the effectiveness of self-regulated learning in massive open online courses on non-native English speakers. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 13(3), 61-73. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijdet.2015070105

Dornan, T., Tan, N., Boshuizen, H., Gick, R., Isba, R., Mann, K., Scherpbier, A., Spencer, J., & Timmins, E. (2014). How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Experience based learning (ExBL). Advances in Health Sciences Education, 19(5), 721-749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-014-9501-0

Dubé, T. V., Schinke, R. J., Strasser, R., Couper, I., & Lightfoot, N. E. (2015). Transition processes through a longitudinal integrated clerkship: A qualitative study of medical students’ experiences. Medical Education, 49(10), 1028-1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12797

Eriksson, T., Adawi, T., & Stöhr, C. (2017). “Time is the bottleneck”: A qualitative study exploring why learners drop out of MOOCs. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29, 133-146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-016-9127-8

Findyartini, A., Anggraeni, D., Husin, J. M., & Greviana, N. (2020). Exploring medical students’ professional identity formation through written reflections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health Research, 9(s1). https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2020.1918

Findyartini, A., Greviana, N., Hanum, C., Husin, J. M., Sudarsono, N. C., Krisnamurti, D. G. B., & Rahadiani, P. (2021). Supporting newly graduate medical doctors in managing COVID-19: An evaluation of Massive Open Online Course in a limited-resource setting. PLoS ONE, 16(9), e0257039. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257039

Hall, A. K., Nousiainen, M. T., Campisi, P., Dagnone, J. D., Frank, J. R., Kroeker, K. I., Brzezina, S., Purdy, E., & Oswald, A. (2020). Training disrupted: Practical tips for supporting competency-based medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical Teacher, 42(7), 756-761. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1766669

Hambleton, R. K. (2005). Issues, designs, and technical guidelines for adapting tests into multiple languages and cultures. In R. K. Hambleton, P. F. Merenda, & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment (pp. 3–38). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2014). Students’ and instructors’ use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educational Research Review, 12, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.001

Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Isaac, C., Petrashek, K., Steiner, M., Manwell, L. B., Carnes, M., & Byars-Winston, A. (2013). Male spouses of women physicians: Communication, compromise, and carving out time. The Qualitative Report, 18(52), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1423

Jansen, R. S., van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., & Kester, L. (2018). Validation of the revised self-regulated online learning questionnaire. In V. Pammer-Schindler, M. Pérez-Sanagustín, H. Drachsler, R. Elferink, & M. Scheffel (Eds.), Lifelong Technology-Enhanced Learning (pp. 116-121). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98572-5_9

Jansen, R. S., van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., Kester, L., & Kalz, M. (2017). Validation of the self-regulated online learning questionnaire. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29, 6-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-016-9125-x

Jouhari, Z., Haghani, F., & Changiz, T. (2015). Factors affecting self-regulated learning in medical students: A qualitative study. Medical Education Online, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v20.28694

Liang, Z. C., Ooi, S. B. S., & Wang, W. (2020). Pandemics and their impact on medical training: Lessons from Singapore. Academic Medicine, 95(9), 1359-1361. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003441

Liaw, S.–S., & Huang, H.–M. (2013). Perceived satisfaction, perceived usefulness and interactive learning environments as predictors to self-regulation in e-Learning environments. Computers & Education, 60(1), 14-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.07.015

Magno, C. (2011). Validating the academic self-regulated learning scale with the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) and Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI). The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 7(2), 56-73.

Malau-Aduli, B. S., Roche, P., Adu, M., Jones, K., Alele, F., & Drovandi, A. (2020). Perceptions and processes influencing the transition of medical students from pre-clinical to clinical training. BMC Medical Education, 20, 279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02186-2

Mangundjaya, W. L. H. (2013). Is there cultural change in the national cultures of Indonesia? In Y. Kashima, E. S. Kashima, & R. Beatson (Eds.), Steering the cultural dynamics: Selected papers from the 2010 Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/105/

National Ministry of Health. (2020, December 31). Health care workforce statistics database in Indonesia. Retrieved May 10, 2021, from http://bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id/info_sdmk/info/index?rumpun=101

National Ministry of Health. (2021, April 23). Current situations of the development of novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://covid19.kemkes.go.id/situasi-infeksi-emerging/situasi-terkini-perkembangan-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-23-april-2021

Ortiz-Martìnez, Y., Castellanos-Mateus, S., Vergara-Retamoza, R., Gaines-Martìnez, B., & Vergel-Torrado, J. A. (2021). Online medical education in times of COVID-19 pandemic: A focus on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), Educación Médica, 22, S40. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.edumed.2020.12.001

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & Mckeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MLSQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(3), 801-813. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013164493053003024

Poonia, S. K., & Rajasekaran, K. (2020). Information overload: A method to share updates among frontline staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 163(1), 60-62. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0194599820922988

Sandars, J., & Patel, R. (2020). The challenge of online learning for medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Medical Education, 11, 169-170. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5f20.55f2

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modelling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Stracke, C. M., Tan, E., Moreira Texeira, A., do Carmo Pinto, M., Vassiliadis, B., Kameas, A., Sgouropoulou, C., & Vidal, G. (2018). Quality Reference Framework (QRF) for the Quality of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs): Developed by MOOQ in close collaboration with all interested parties worldwide. MOOQ. http://www.mooc-quality.eu/QRF

Vilkova, K. A. (2019, May 20-22). Self-regulated learning and successful MOOC completion [Europeaan MOOCs Stakeholders Summit 2019 Conference]. Proceedings of EMOOCs: Work in Progress Papers of the Research, Experience and Business Tracks.

Virtanen, P., & Nevgi, A. (2010). Disciplinary and gender differences among higher education students in self-regulated learning strategies. Educational Psychology, 30(3), 323-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443411003606391

Wong, J., Baars, M., Davis, D., Van Der Zee, T., Houben, G.-J., & Paas, F. (2018). Supporting self-regulated learning in online learning environments and MOOCs: A systematic review. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 35(4-5), 356-373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1543084

Yen, C.-J., Tu, C.-H., Sujo-Montes, L., & Sealander, K. (2016). A predictor for PLE management: Impacts of self-regulated online learning on students’ learning skills. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 9(1), 29-48. https://doi.org/10.18785/jetde.0901.03

*Nadia Greviana

Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia,

Jalan Salemba 6 Central Jakarta, Indonesia,

Email: nadiagreviana@ui.ac.id/ nadia.greviana@gmail.com

Submitted: 19 May 2021

Accepted: 26 August 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 66-75

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/OA2521

Lay Ling Tan1, Pim W. Teunissen2, Wee Shiong Lim3, Vanessa Wai Ling Mok1 & Hwa Ling Yap1

1Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore; 2School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Maastricht University, Netherlands; 3Cognition and Memory Disorders Service, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Development of expertise and counselling skills in psychiatry can be mastered only with effective supervision and mentoring. The conceptualisations of educational supervision amongst supervisors and residents were explored in this study to understand how supervisory roles may have been affected by the adoption of competency-based psychiatry residency training.

Methods: A qualitative research approach with thematic analysis was adopted. Individual in-depth interviews using a semi-structured interview guide with a purposive sample of six supervisors and six newly graduated residents were conducted. Transcripts of the interview were analysed and coded using the Atlas Ti software.

Results: Four major themes emerged from analysis of the transcripts: (1) Meaning and definition of supervision; (2) Expectations and responsibilities of the educational supervisor; (3) Elusiveness of mentoring elements in educational supervision and (4) Personal and professional development of residents in supervision. Supervisors and residents perceived educational supervision narrowly to be transactional with acquisition of knowledge and skills, but residents yearned for more relational interactions.

Conclusion: This study showed that the roles and functions of supervisors in educational supervision were unclear. It also highlighted the lack of a mentoring orientation in supervision in the psychiatry residency training program. An emphasis on assessment of competencies might have contributed to tension in the supervisory relationship and lack of a mentoring role, with concerns on residents’ personal and professional identity development in their psychiatry training.

Keywords: Psychiatry, Mentoring, Educational Supervision, Competency-Based Medical Education, Professional Identity Development

Practice Highlights

- Supervision in psychiatry has been described to encompass more than just a teaching and learning relationship but also a supportive and mentoring one.

- Educational supervision has been purported to offer the unique opportunity for effective mentoring within supervision.

- This qualitative study highlighted significant differences in definitions, roles and expectations of educational supervision.

- The conflict between mentoring and appraisal of competency needs to be addressed.

- Roles and expectations of the educational supervisor must be articulated clearly to both supervisors and residents.

I. INTRODUCTION

Postgraduate medical education (PGME) in Singapore underwent tremendous changes in the last decade. Before 2009, Singapore’s PGME was structured around time frames and curricular processes, in contrast to competency-based medical education (CBME) (Frank et al., 2017). In 2008, Singapore’s Ministry of Health (MOH) raised concerns of the lack of clear learning objectives and absence of measurable standards of training and outcomes with the medical schools and teaching hospitals. MOH recognised a need to ensure that every PGME graduate is prepared for clinical practice with the necessary competencies. With that vision in mind, MOH collaborated with the United States (US) Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to revamp the PGME structure and accreditation system in 2009 (Chay, 2019). This move has resulted in major changes in the psychiatry postgraduate program. The 5-year National Psychiatry Residency Training Program was launched with a main teaching site and six sponsoring institutions. It also instituted the educational supervision framework where an assigned educational supervisor meets the supervisee regularly during the whole duration of training.

A. Concepts of Supervision

Supervision originated in professions outside of medicine (Launer, 2013) and is a distinct professional practice with specific articulated competence and training (Falender & Shafranske, 2007). It has been considered as a combination of various elements and is not a uniform concept (Carroll, 2006). Supervision is critical for ensuring effective professional practice of the healthcare sector (Tebes et al., 2011), particularly in psychiatry, where counselling skills can be developed only with effective supervision and mentoring.

1) Clinical supervision: Clinical supervision is subcategory to the wider concept of supervision. One definition is “provision of guidance and feedback on matters of personal, professional and educational development in the context of a trainee’s experience of providing safe and appropriate care” (Kilminster et al., 2007). There is consensual acceptance of the basic functions of clinical supervision: formative, supportive and managerial (Kilminster et al., 2007). These functions overlap depending on the context, problems emphasised and supervision goals (Kadushin, 1985).

2) Educational supervision: Educational supervision, on the other hand, has been described as regular supervision occurring in the context of a training program to determine learning needs and review progress of the supervisee (Passi, 2016). There has been extensive research done in clinical supervision (Kilminster et al., 2007; Patel, 2016) but educational supervision is under-researched with very few such studies conducted in psychiatry. It can be considered to be the most complex and challenging form of supervision as there are a number of overlapping and at times conflicting roles which need to be fulfilled (Launer, 2013). Aside from having to facilitate learning, there is also the need to evaluate the supervisee’s performance, which may result in confusion in the supervisory roles. Educational supervision has been purported to offer the unique opportunity for effective mentoring within supervision (Passi, 2016), which ideally should be recognised as an important component of the whole supervisory framework (Driessen et al., 2011).

B. Conceptual Framework for Educational Supervision in Postgraduate Psychiatry Training

Clinical and educational supervision are essential for development of health professionals and widely recognised as crucial for effective learning (Pront et al., 2016) and reflective practice (Schon, 1987). Learning in educational supervision can be conceptualised from experiential and social learning theory. Experiential learning is a key concept of the developmental-educational model of educational supervision (Kolb, 1984/2014). Learning is also a social process, where the supervisee is influenced by the cultural system of social knowledge and learns the trade with the guide of a more experienced colleague (Vec et al., 2014), a particularly important component in the field of psychiatry, a discipline closely related to the social sciences. Thus, there has been frequent reference to this apprenticeship model in supervision, although there is no clear definition of the term in the context of psychiatry training (MacDonald, 2002).

Supervision in psychiatry has its roots in psychoanalysis (Torby et al., 2015). Supervision in the context of general psychiatry training was mentioned infrequently and the concepts of supervision of the psychotherapeutic work of trainees were often transferred directly into the setting of general clinical supervision as if the two situations were identical (MacDonald, 2002). The supervisor can be seen as fulfilling the role of the analyst of the supervisee’s analytic ego (Akhtar, 2009). This necessitates a trusting relationship between the supervisor and supervisee, very much akin to that of informal mentoring, which has been described as psychosocial in nature and serves to enhance the supervisee’s self-esteem through interpersonal dynamics of the relationships, the emotional bonds they form and the work they accomplish together (Hansman, 2001). Supervision has also been frequently conceptualised as a development process or a process of identification (MacDonald, 2002). This is the transformation of a trainee through the acquisition of requisite knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and attributes; from doing the work of a psychiatrist to being a psychiatrist (Wald, 2015). This active, constructive and transformative process has been referred to as professional identity formation (Wald, 2015). This continuous process requires the fostering of personal and professional growth through mentorship and self-reflection (Holden et al., 2015). The provision of guidance and mentoring with respect to personal and professional identity development would arguably be more critical in supervision in psychiatry. The personal aspects and the development of better self-awareness in the supervisee and the ‘internalised supervisor’ has been considered by some to be the fundamental goal of supervision (Kadushin, 1985). However, this will require the training program to allow sufficient time and opportunity to build and develop the supervisor-supervisee relationship.

With ACGME setting up collaborative initiatives with other countries and a trend towards a competency-based training approach, a better understanding of the impact of CBME on the supervision process and structure will be relevant to our international educators. The mentoring element in educational supervision has the potential to ensure that learning is not guided entirely by assessment and evaluation but is supplemented by the periodic guidance of a trusted mentor and addressing the personal and professional components in clinical supervision (Kilminster et al., 2007). With the implementation of the ACGME training framework, understanding the complexity and barriers of developing a mentoring relationship in educational supervision will be crucial. The research questions which this study aimed to answer were:

1. What are supervisors’ and residents’ perceptions on the educational supervisory role in the psychiatry residency program?

2. How do supervisors and residents perceive the supervisor’s mentoring roles in their educational supervision experience?

II. METHODS

A. Design

This was a qualitative research strategy where individual in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of six supervisors and six residents were conducted, the intent of which was to understand the participants’ meanings of the phenomenon of educational supervision (Creswell, 2014). Ethics approval was sought from the Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2017/2319) and informed consent was received from all participants.

B. Setting

The residency training program instituted the educational supervision framework by ACGME where an assigned educational supervisor meets the supervisee weekly of at least an hour duration. The educational supervisor is responsible for completion of the resident’s evaluation reports based on feedback gathered from the resident’s clinical supervisors and offer recommendations for the supervisee’s training progress. Clinical supervisors in the residency program are consultants managing patients together with the residents in the ward and clinic settings. Work-placed based assessments in the form of mini-clinical evaluations (mini-cex) and 360-degree feedback evaluations are done by both the educational and clinical supervisors.

There are six teaching sites in the psychiatry residency program and the researcher’s teaching site is one of the largest, with 18 supervisors overseeing nine to 12 residents posted in their various years of training. The setting of the research was the teaching site where the PI (Principal Investigator) served as Associate Program Director (APD).

C. Subjects

Six supervisors with two each from the Associate Consultant, Consultant and Senior Consultant group, and one male and one female from each group were invited to participate. For the residents, those who had just graduated from the residency program were invited. A total of six recently graduated residents (three males and three females) were sampled. This was to minimise biases related to fear of negative evaluation or power differentials while still undergoing residency training. It was hoped that with this purposive sampling, a relevant mix of supervisory experiences from the participants would be achieved.

D. Data collection

One-to-one semi-structured interviews were conducted by the PI using an interview guide (Appendix 1). The interview guide was developed by the PI with inputs from the research team. The interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent of the participants. Due attention was paid to the content of the participants’ sharing and the emerging themes during the interview and analysis process such that consideration of including more participants in the study would be taken if there was a need for further varied views to be elicited (Creswell, 2014).

E. Analysis

A qualitative research approach with thematic analysis was adopted. The Atlas Ti (version 8) software was used to code and analyse the data. Coding of all the data was made by the PI before a coding structure was created. There was a reiterative development and re-development of the coding structure such that all the data were appropriately accounted for. Codes were added and revised as more interviews were conducted. All the data were coded according to the study objectives and were classified into categories that reflected the emerging themes. Based on further readings in medical education literatures, the themes were grouped and sub-grouped in a logical fashion to form a thematic template. The raw data were revisited regularly throughout the analytic process to ascertain that the codes and resulting themes were grounded in the data. To ensure adequate coding and to improve the research reliability, we performed investigators’ triangulation. The co-investigator (LWS) was invited to analyse the first three interviews independently. The PI and co-investigators (TLL, VM, YHL) discussed regarding the main themes developed and differences were addressed and reconciled. To further improve credibility and transferability of the research data and its analysed results, member checking was used and participants’ comments regarding the developed themes were solicited. There was general agreement with the results generated from their interviews.

III. RESULTS

Six supervisors and six supervisees completed the study. As the research progressed, there was the progressive realisation of an overarching pattern emerging around the supervisory process, namely, the heterogeneity of the concept of supervision and the tension and conflicts amongst its various roles and functions.

Four major themes emerged:

- Meaning and definition of supervision

- Expectations and responsibilities

- Elusiveness of mentoring elements in educational supervision

- Personal and professional development in supervision

A. Meaning and Definition of Supervision

1) Supervisor’s perspectives: Supervisors defined supervision as “observing”, “helping”, “guiding”, “teaching”, “grading” and “assessing” the residents such that they could be certified to fulfil the program requirements. These descriptors suggested a supervisor-centric definition.

“Someone in a position of experience or age supervises, in other words…observe…teaches, impact knowledge and skills to the supervisee…is like watching somebody”

(S1)

2) Residents’ perspectives: Residents referred to supervision as an “apprenticeship”, “guiding and checking on progress” and promoting the “maturation as a clinician”. There was the repeated emphasis on the supervisor attending to the resident’s “growth”, “personal well-being” and to “encourage” and “commend”.

“…essentially is in line with the whole practice of medicine where there is apprenticeship, someone has to guide…to encourage, commend, growth…”

(R1)

B. Expectations and Responsibilities

1) Supervisor’s perspectives: Supervisors expected residents to be able to exhibit the attitude of being “able to talk about things and not being afraid of being judged”; “to pay attention to personal development so that the resident is more real as a person”; “to be ready to give feedback about supervision” and “being comfortable, open and trusting of the supervisor’s intentions”.

In practice, however, faculty observed that residents were “not expecting beyond helping them with clinical work”; “does not talk about struggles and frustrations” and were “not used to opening up”. Although engaging the resident with regards to their struggles was identified to be important, it was highlighted as “not the culture or consistently practiced” and that “residents may not appreciate why we want them to talk about their feelings”.

Faculty viewed discussing about resident’s personal issues as intrusive and a violation of the boundaries in supervision.

“We also have to keep some boundaries… we are careful not to go beyond certain boundary especially if it is something which the supervisee is not very comfortable with”

(S1)

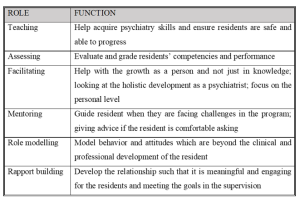

Table 1 illustrates our faculty’s understanding of the roles and functions of the educational supervisor.

Table 1: Faculty’s understanding of the roles and functions of the educational supervisor

2) Residents’ perspectives: Residents’ expected the educational supervisor to be “approachable and open”, “easy to talk to”, “relaxed”, “able to attend to personal growth”, “helping to reflect” and “build rapport”. Residents thus expected a more relational as opposed to transactional interaction with the supervisor.