Combination of Teddy Bear Hospital and Virtual Reality Training increases empathy of medical students

Submitted: 5 January 2022

Accepted: 24 February 2022

Published online: 5 July, TAPS 2022, 7(3), 33-41

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/OA2739

Javier Zheng Huan Thng1, Fion Yun Yee Tan1, Marion Margaret Hui Yong Aw1,2 & Shijia Hu3

1Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Paediatrics, Khoo Teck Puat-National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Health System, Singapore; 3Faculty of Dentistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: In paediatric practice, healthcare professionals are required to connect with the child and interact at his/her level. However, it can be very difficult for medical students to put themselves in the shoes of the young child, to empathize and understand how a child actually feels while being treated. The Teddy Bear Hospital (TBH) can serve as a platform for medical students to learn how to communicate and empathise with children. Additionally, virtual reality (VR) can be used to portray a child’s viewpoint. This study aims to assess how TBH and VR can improve learning outcomes for medical students.

Methods: A cohort study was conducted on 20 first-year medical students taking part in TBH sessions. The medical students did a Pre-, Post- and 1-year Post-intervention Jefferson Scale of Empathy to assess their empathy levels. They also completed a 1-year Post-intervention quantitative and qualitative survey on their experience.

Results: There was a significant increase in Jefferson score compared to Pre-intervention (116.95 ± 8.19) for both Post-intervention (121.65 ± 11.03) and 1-year Post-intervention (123.31 ± 8.86). More than 80% believed that participating in TBH improved their confidence and ability to interact with children, while 50% felt that VR scenarios helped prepare them for the TBH. Thematic analysis of qualitative responses described (1) Personal development, (2) Insights into interacting with children, and (3) Structure and curriculum.

Conclusion: TBH improved empathy and communication with children among pre-clinical medical students and the use of VR can be used to augment sessions.

Keywords: Education, Medical Student, Simulation Training, Teddy Bear Hospital, Virtual Reality

- The Teddy Bear Hospital sessions, consisting of physical simulation of medical scenarios with children, increased empathy of medical students.

- The use of virtual reality scenarios to portray the viewpoint of a child can augment the teaching of the Teddy Bear Hospital.

- The Teddy Bear Hospital and virtual reality sessions improved the comfort, increased confidence, and self-perceived ability of interacting with children in medical students.

I. INTRODUCTION

In paediatric practice, healthcare professionals are required to connect with the child and interact at his/her level. This is especially important, when the child is encountering new and unfamiliar situations or when they are unwell and face potentially challenging and painful procedures (Mead & Bower, 2002). However, it can be very difficult for new practitioners to put themselves in the shoes of the young child, to empathise and understand how a child actually feels while being treated (Dwamena et al., 2012). This is particularly true for medical students, who not only have to grapple with the unfamiliar medical aspects of pediatric disease, but may also need to manage a frightened and uncooperative child at the same time (MacDonald-Wicks & Levett-Jones, 2012). Furthermore, having limited interaction with children means that most medical students have a difficult time empathising with them.

Empathy is an important element in a physician-patient relationship, as it has shown to improve communication and therapeutic goals (Mercer & Reynolds, 2002). However, several studies have shown significant decrease in empathy over the course of medical school (Neumann et al., 2011). Although there have been numerous methods and approaches developed to enhance empathy in medical students (Batt-Rawden et al., 2013), including interventions based around the patient narrative (e.g. creative writing, blogging, drama, poetry, fiction, and film), problem-based learning, interpersonal skills training, patient interviews, and experiential learning (simulation of patient experience). Among these interventions, experiential (immersive) learning experiences have shown promising results (Halton & Cartwright, 2018). These scenarios can be conducted either physically or virtually. It can involve the learner completing a simulated task or experience a scenario from the point of view of someone else so as to put themselves in someone else’s shoes.

The advent and advancement of virtual reality (VR) media provide the opportunity for the portrayal of different viewpoints (Lok et al., 2006). A recent study found that empathy in medical students was improved with VR portraying the viewpoint of an older patient with conditions such as macular degeneration and hearing loss (Dyer et al., 2018). However, there has not been any research done on the use of VR to simulate the point of view of a child in a medical setting. The power of immersive media can be harnessed to simulate interactions between a child and healthcare professionals, exhibiting both positive and negative examples. More importantly, it can be used to introduce an inexperienced practitioner to the viewpoint of a child patient. This will help foster empathy and drive home the effectiveness of behaviour management skills (Stewart et al., 2013).

The Teddy Bear Hospital (TBH) is an international initiative, carried out by students from Medical Faculties, aimed at reducing children’s anxiety around medical environments, procedures and professionals (Bloch & Toker, 2008; Santen & Feldman, 1994; Siegel et al., 2018). TBH simulates the different medical environments and clinical situations which children may encounter in a friendly manner using they own toys (such as teddy bears). This simulation takes the form of multi-station role-plays, which could include a check-up by the doctor, watching a doctor applying a cast for a limb fracture or performing a procedure (e.g., taking a blood sample), or receiving an injection (all performed on teddy bears, who are the patients). In addition to reducing anxiety in young children, the TBH has also been used to teach medical students communication with children in a medical setting (Nheu et al., 2018; Ong et al., 2018). Although the qualitative feedback from medical students have been generally positive (Nheu et al., 2018; Ong et al., 2018), there have not been objective measures of the effect of the TBH on the empathy of medical students.

Both VR and TBH are immersive interventions that can potentially increase the empathy of medical student, they can also improve the learning experience by allowing students to experience effective techniques to interact with children and practice those techniques. However, each intervention has inherent disadvantages. VR usually follows a scripted scenario that does not allow students to practice and interact in real-time. While TBH is time and resource intensive, and cannot be conducted is situations such as a pandemic. Therefore, evaluating the effects of a combination of the 2 techniques can inform on the individual effectiveness as well as in combination.

This study aims to determine the effect of virtual and physical simulation on the empathy and learning experience of medical students. This will be done through a combination of VR instruction and practical simulation in a TBH experience, in which medical students are exposed to and educated on the positive interactions with a child patient in various medical scenarios.

II. METHODS

This is a cohort study of first year medical students who took part in TBH sessions in January 2020 and were followed up in January 2021. Subjects were recruited from volunteers who signed up to participate in TBH sessions. Subjects were reassured that their responses are strictly confidential and will have no impact on their grades or teaching received. Medical students who have participated in previous TBH sessions were excluded. Written informed consent was taken prior to participation. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB Reference Number: S-19-151) and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

As this was a pilot study, no sample size calculation was conducted prior to study initiation.

A. Survey Content and Timing

The Jefferson Scale of Empathy (Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, PA, USA) was used to assess the level of empathy (Hojat et al., 2018). It is a 20-item scale that was developed specifically to measure empathy in health professions education, including medical students. The S-version of the survey, for medical students, was administered in this study. The survey forms were purchased from Thomas Jefferson University, Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care. The Jefferson scores were calculated out of a maximum of 140. The survey was conducted in its original English version as the language medium for education in Singapore is English and all participants are proficient.

1) Pre-intervention: Prior to the TBH session, the subjects completed the Jefferson Scale of Empathy to assess baseline empathy scores. The subjects then underwent a small group teaching session of one hour including viewing of two VR scenarios, conducted by the same instructors (JT & FT). The small group teaching sessions covered topics pertaining to doctor-patient relationship, and the developmental and psycho-affective challenges of interacting with children. The two VR scenarios depicted a child’s point of view in the setting of getting an injection (mooc vid, Scenario 1, 2019) and visiting the dentist (mooc vid, Scenario 2, 2019). The scenarios are interactive and the point of view can be manipulated by the viewer. After watching the VR scenarios, discussions where subjects can critique the healthcare providers’ actions and share their learning points were carried out. During this session, the subjects were also briefed about the different scenarios in the TBH session, including the content to be covered.

2) TBH session: The TBH session consisted of 5 scenarios namely: (1) Orthopedic Specialist: Meet Mr. Bones, (2) Respiratory Therapist: Help Teddy Breathe, (3) Family Medicine: Help Teddy Stay Healthy, (4) Personal Hygiene: Help Teddy Stay Clean, (5) Operating Theatre: Teddy has a Painful Tummy. The injection process and dental procedures were incorporated into scenarios 3 and 4 respectively. The medical students were divided into teams of 2 to 3, each interacting with a group of 5 to 8 children of the same age. Each team rotated through the different scenarios for 10 minutes. At each scenario, the medical students explained the task to the children and conducted hands-on simulation.

3) Post-intervention: After their first TBH session, the subjects completed a second Jefferson Scale of Empathy.

4) 1-year Post-intervention: One year after the TBH session, students completed a third Jefferson Scale of Empathy, along with a self-administered survey regarding the long-term impact of TBH sessions and the effectiveness of the VR scenarios.

To assess the long-term impact of TBH sessions and the effectiveness of the VR scenarios, a 1-year Post-intervention survey was administered in December 2020. The survey was adapted from a previous study (Ong et al., 2018) and piloted for understanding and readability.

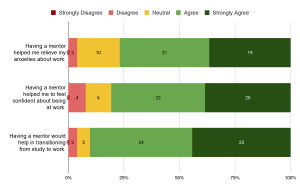

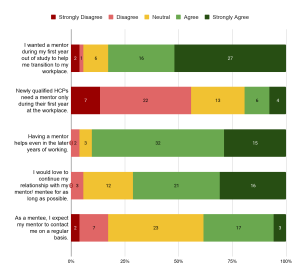

The 1-year Post-intervention impact of TBH sessions was assessed using five questions on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree) regarding the effect of TBH sessions on improving the medical student’s ability, confidence and comfort level in communicating with children, and ability to empathize with children’s fear in the healthcare environment. Similarly, the effectiveness of the VR scenarios was assessed using three questions on a 5-point Likert scale, regarding the effect of the VR scenarios on preparation for TBH session, as well as improving the comfort level and confidence in engaging children. The remaining two questions obtained qualitative feedback regarding any difficulties faced as well as takeaways obtained during the TBH session.

B. Data Collection

The subjects completed the TBH sessions in small groups of up to eight volunteers, with up to 30 children, aged between 4 to 8 years old, in each session. It was explained to the children that they were participating in an activity to teach them about what happens during visits to a doctor. These sessions were conducted at the participating pre-schools with medical instruments and teddy bears as simulated patients.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation and restrictions, the survey was collected via an online survey, instead of a planned Focused Group Discussion.

C. Data Analysis

Normality of data was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test, data analysis of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy score was done via Paired samples correlation, Cohen’s d score and Paired Samples T test using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (IBM SPSS Statistics 26, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented for the survey on learner experience.

Qualitative analysis was done on the medical students’ open-ended responses regarding the long-term impact of TBH sessions and the effectiveness of the VR scenarios. Using thematic content analysis and a qualitative descriptive framework (Creswell & Poth, 2019), emerging themes and illustrative quotes for each theme were extracted. The codes and themes were first done independently by two of the authors (JT & FT), any discrepancies were discussed and reconciled. After which, 2 other authors (SH & MA) reviewed and verified the finalised codes and themes, which were mapped for interpretation. Descriptive summaries and illustrative quotes were used to describe each theme.

III. RESULTS

A. Study Demographics

In total, 20 first time participants were recruited and consent was taken. All 20 were first year medical students; 9 males and 11 females. All participants (n=20) completed the Pre-intervention and Post-intervention survey while 16 completed the 1-year Post-intervention survey, with 4 participants declining to participate in the follow-up. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17973662 (Hu, 2022).

B. Jefferson Scale of Empathy

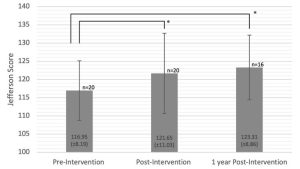

There was a significant (p=0.026) increase in the Jefferson score between the Pre-intervention (116.95 ± 8.19) and Post-intervention (121.65 ± 11.03). Similarly, there was a significant (p=0.002) increase from the Pre-intervention to 1-year Post-intervention (123.31 ± 8.86). (Figure 1) However, there was no difference between the Post-intervention and 1-year Post-intervention scores.

Cohen’s d score was used to determine the effect size of the intervention on the mean difference between the Pre- and Post-intervention score (0.48), and the Pre- and 1-year Post-intervention score (0.72). This corresponds to a medium effect of the intervention on the mean differences.

Figure 1. Jefferson Scale of Empathy Score before, immediately after and 1 year after TBH. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisk (*) indicate significant differences between the groups, p<0.05.

C. Quantitative Survey

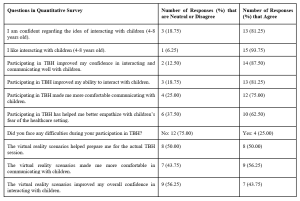

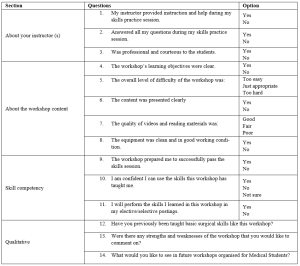

Quantitative responses from the survey on learner experience were categorised into positive responses (agree, strongly agree) and negative/neutral responses (neutral, disagree, strongly disagree). The total number of responses collected was 16 at 1-year Post-intervention (Table 1).

Table 1. Subject’s perception towards their TBH experience

The subjects were generally confident (75%) and enjoyed interacting with young children (94%). More than 80% believed that participating in TBH improved their confidence and ability to interact with children, and 75% felt that participating in TBH made them more comfortable communicating with children. 63% felt that TBH helped improve their ability to empathize with children’s fears of the healthcare setting. Overall, 75% of subjects did not face difficulties during the TBH sessions. In terms of the VR scenarios, around 50% felt that it was effective in preparing for the actual TBH session, with 56% feeling more comfortable and 44% feeling more confident interacting with children.

D. Qualitative Survey

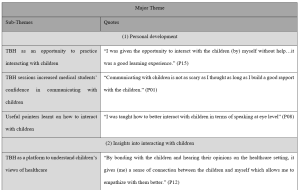

Three major themes were generated from the analysis of the open-ended responses from 16 of the 20 subjects: (1) Personal development, (2) Insights into interacting with children and (3) Structure and curriculum of TBH. These themes were further categorised into sub-themes as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Major themes, sub-themes and transcript highlights of qualitative survey

1) Personal development

TBH provided an opportunity for medical students in this study to interact with children in a safe and stress-free environment. These students would otherwise have limited experience communicating with children in that age-group, until actual clinical interactions with sick children.

“I was given the opportunity to interact with the children (by) myself without help…it was a good learning experience.” (P15)

The experience gave these medical students more confidence and reduced their anxiety about interacting with children, as they realized that it was not as difficult as they thought to communicate with children.

“Communicating with children is not as scary as I thought as long as I build a good rapport with the children.” (P01)

Medical students also learnt useful pointers on how to interact and communicate with children, which alleviated their worries and improved their confidence. These pointers include using simpler words, hand actions, speaking at eye level and being more expressive.

“(TBH) allowed me to practice how I interact with children (by) using easier words (and) hand actions” (P01)

“I was taught how to better interact with children in terms of speaking at eye level” (P08)

2) Insights into interacting with children

TBH was a unique platform to understand children’s learning needs and empathize with their views towards healthcare. This was achieved via interactions with the children.

“By bonding with the children and hearing their opinions on the healthcare setting, it gives (me) a sense of connection between the children and myself which allows me to empathize with them better.” (P12)

These interactions allowed medical students to learn how to adapt their teaching styles to suit the different needs of each individual child.

“I learnt to interact with different groups of children with different learning abilities and TBH taught me how to cater to the different needs and abilities of the kids instead of treating them as a homogenous group.” (P07)

These interactions also taught medical students that the children have different levels of fear towards healthcare. While some children were apprehensive, others were unafraid of the TBH sessions.

“The children shared their fears about healthcare providers and I think the bulk of this fear comes from not being able to see the benefit of receiving these ‘painful’ treatments.” (P09)

“The children seemed to be really excited during the TBH sessions, I don’t recall that the children expressed any fear about their experiences” (P16)

In addition to understanding the children’s fears towards healthcare, medical students learnt how to manage these fears by acknowledging them and putting themselves in the children’s shoes.

“We should never downscale a child’s fear towards healthcare. There is a need to try to understand where they are coming from, (and) to comfort and encourage them to the best of our ability.” (P13)

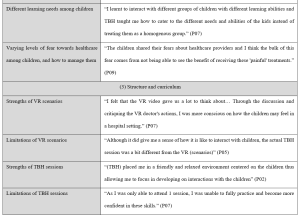

3) Structure and curriculum

To understand the impact of the newly added VR scenarios, feedback regarding its strengths and limitations were collated. One strength is that the students experienced various case studies through the VR scenarios. This allowed them to be better prepared for the TBH sessions and become more aware of the children’s emotions during their interaction.

“I felt that the VR video gave us a lot to think about… Through the discussion and critiquing the VR doctor’s actions, I was more conscious on how the children may feel in a hospital setting.” (P07)

Another strength is that during the training, medical students were also asked how they would respond to the hypothetical scenarios. By putting them in the hot seat, they were able to exchange ideas and learn from one another.

“The volunteer trainers asked us questions during the volunteer training, when I answered correctly it gave me more confidence and when I listen to other people’s answers, I feel more equipped to handle different situations too” (P15)

The VR scenarios were limited in terms of application to the actual TBH sessions. The scenarios only showed how to engage an individual child, which was different from actual TBH sessions, in which medical students had to teach a group of children.

“Although it did give me a sense of how it is like to interact with children, the actual TBH session was a bit different from the VR (scenarios)” (P05)

Feedback was also collated regarding the strengths and limitations of the TBH sessions.

One strength was the established curriculum so participants did not have to worry about the content but can instead focus on honing their communication skills. The fact that this was a student-run program, and that medical students had their peers as fellow participants, put them at ease and made it a more conducive environment.

“(TBH) placed me in a friendly and relaxed environment centred on the children thus allowing me to focus in developing on interactions with the children” (P02)

A limitation of the TBH sessions was that it was challenging for participants to balance teaching the children and empathising with them.

“I think it’s … difficult to see from the children’s perspective during the session… We are usually more focused on imparting rather than listening because of the inability to elicit responses from all of them.” (P13)

Another limitation of the TBH sessions was that participants are usually able to attend only one session. This may have held them back from being fully adept in their interactions with children.

“As I was only able to attend 1 session, I was unable to fully practice and become more confident in these skills.” (P07)

Finally, there were disagreements about whether the ratio of medical students to children was suitable. While some felt that it was appropriate, others had trouble managing the children.

“The ratio (of) facilitators to children were just nice (and) not overwhelming for either parties” (P15)

“It was just too chaotic and hard to manage so many of them especially since they’re so bubbly and curious” (P16)

IV. DISCUSSION

This was the first study to examine objectively and subjectively, the effect of TBH and VR training on the empathy levels of medical students. There was a statistically significant improvement in the medical student’s level of empathy immediately after the TBH session, which persisted 1 year after the TBH session. The outcomes of this study revealed that the medical students who participated in TBH augmented by VR training assisted them to better empathize with the children they worked with.

Compared with the previous work by Ong et al in the same institution, involving only traditional lecture preparation for TBH (Ong et al., 2018), it appears that the addition of VR training showed an increase in medical students’ perceived improvement in both interacting and teaching children. In that study conducted without the use of VR scenarios, 53% reported improvement in interacting with children and 39% reported improvement in teaching children, compared to the present study of 88% and 75% respectively. Moreover, VR training alone achieved improvements of 44% and 50% which is similar to TBH session alone. A recent study found that VR simulation alone improved the empathy of dental students when managing children (Hu & Lai, 2022), this is encouraging since the VR intervention was not as time and resource intensive as the TBH. Although the cohorts of medical students were different, each cohort is from the same year of training (i.e., first year medical students) and the TBH teaching was done with a standardised protocol and thus relatively similar across the cohorts. It appears that a combination of the 2 methods of training provided a greater magnitude to the student’s perceived improvement in interacting and teaching children. This suggests that although the VR training cannot replace the real TBH interaction with children, it can be used to augment the learning experience of students in communicating with children. Moreover, it can be deployed on a much larger scale to the entire cohort, instead of smaller groups like the labour intensive TBH teaching.

According to the qualitative analysis, the TBH is a good platform for medical students to practice and develop their communication skills with children. Through TBH, they pick up techniques on how to better communicate with children both from the trainers and their peers. Similar to previous studies, TBH has also been described to be a useful avenue to gain insights into children’s perspectives of the healthcare setting and therefore trains them to be better attuned to the needs and feelings of children (Nheu et al., 2018; Ong et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the medical students suggested some areas of improvements. For example, it was pointed out that the VR scenarios did not depict the actual TBH session, as such, it did not help in teaching children during TBH. However, the goal of the TBH session is to increase medical student’s empathy through teaching rather than training them to be educators. Therefore, the VR scenarios can still bring the desired benefits in terms of the medical student’s ability to empathize and communicate with children. Additionally, some felt that they are unable to fulfil both a teaching and learning role simultaneously and were overwhelmed. This may hinder them from achieving the desired outcome of increasing their empathy. A potential solution would be to expand the existing course material to further help those who struggle with engaging the children or having fewer children paired to each medical student teacher.

There were some limitations to this study. As there was no control group to compare against, it was difficult to determine if the improvements seen from Pre-intervention to Post-intervention were due to the VR training and participation in the TBH session alone. Future studies could consider including a control group in addition to the intervention group. The observed maintenance of the level of empathy from Post-intervention to 1-year Post-intervention could have been confounded by factors such as varying levels of clinical exposure. Additionally, the quantitative survey on learner experience was done 1 year after the TBH session and may be at risk for recall bias, future studies should consider collecting data at multiple time points to evaluate any difference between immediate and long-term effects of the interventions. However, all respondents provided feedback that were very detailed and informative, suggesting that they were able to recall the experience well. Moreover, due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation and restrictions, the survey was collected via an online survey, instead of the planned Focused Group Discussion, resulting in the inability to ask follow-up or clarifying questions. Lastly, the study was conducted on a small group of volunteers who may have biases due to interest in the discipline. However, a significant improvement was still noted in this small pilot study. Expansion of the program into the general curriculum to include a more diverse group of students will be needed to ascertain the effect of TBH on medical students in general.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the TBH experience for medical students was effective in increasing their levels of empathy and confidence in interacting and teaching children as it provides an opportunity for medical students to interact with children and understand their views of healthcare. The use of VR can augment the TBH experience or be used in situations where the student is unable to attend TBH sessions in person.

Notes on Contributors

JT and FT are considered co-first authors. JT participated in data collection, conducted the data analysis and interpretation, led the writing, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. FT participated in data collection, conducted the data analysis and interpretation, led the writing, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MA conceived the idea and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SH conceived the idea, conducted the data analysis and interpretation, led the writing, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB Reference Number: S-19-151) and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17973662.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Lee Shuh Shing and Ms Lim Yih Lin for their help with the statistical analysis and Manzalab for the help in creating the virtual reality scenarios.

Funding

This work was supported by the USPC-NUS Joint Innovative Projects in Higher Education grant (USPC-NUS 2018 SoM).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Batt-Rawden, S. A., Chisolm, M. S., Anton, B., & Flickinger, T. E. (2013). Teaching empathy to medical students: An updated, systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1171-1177. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3

Bloch, Y. H., & Toker, A. (2008). Doctor, is my teddy bear okay? The “Teddy Bear Hospital” as a method to reduce children’s fear of hospitalization. Israel Medical Association Journal, 10(8-9), 597-599.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2019). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE.

Dwamena, F., Holmes‐Rovner, M., Gaulden, C. M., Jorgenson, S., Sadigh, G., Sikorskii, A., Lewin, S., Smith, R. C., Coffey, J., & Olomu, A. (2012). Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12).

Dyer, E., Swartzlander, B. J., & Gugliucci, M. R. (2018). Using virtual reality in medical education to teach empathy. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(4), 498-500. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2018.518

Halton, C., & Cartwright, T. (2018). Walking in a patient’s shoes: An evaluation study of immersive learning using a digital training intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02124

Hojat, M., DeSantis, J., Shannon, S. C., Mortensen, L. H., Speicher, M. R., Bragan, L., LaNoue, M., & Calabrese, L. H. (2018). The Jefferson Scale of Empathy: a nationwide study of measurement properties, underlying components, latent variable structure, and national norms in medical students. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23(5), 899-920.

Hu, S. (2022). Raw Jefferson Scores. [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17973662

Hu, S., & Lai, B. W. P. (2022). Increasing empathy for children in dental students using virtual reality. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12957

Lok, B., Ferdig, R. E., Raij, A., Johnsen, K., Dickerson, R., Coutts, J., Stevens, A., & Lind, D. S. (2006). Applying virtual reality in medical communication education: Current findings and potential teaching and learning benefits of immersive virtual patients. Virtual Reality, 10(3-4), 185-195.

MacDonald-Wicks, L., & Levett-Jones, T. (2012). Effective teaching of communication to health professional undergraduate and postgraduate students: A systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 10(28), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2012-327

Mead, N., & Bower, P. (2002). Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient education and counseling, 48(1), 51-61.

Mercer, S. W., & Reynolds, W. J. (2002). Empathy and quality of care. British Journal of General Practice, 52(Suppl), S9-S12.

mooc vid. (2019, September 13). Scenario 1 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4f6bZ_Kc2xw

mooc vid. (2019, September 13). Scenario 2 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oz4dm45Imkw

Neumann, M., Edelhäuser, F., Tauschel, D., Fischer, M. R., Wirtz, M., Woopen, C., Haramati, A., & Scheffer, C. (2011). Empathy decline and its reasons: A systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Academic Medicine, 86(8), 996-1009. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

Nheu, L., Uahwatanasakul, W., & Gray, A. (2018). Medical students’ experience of a Teddy Bear Hospital as part of a paediatric curriculum. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-disciplinary Journal, 19(3), 40.

Ong, L., Chua, K. H., Soh, J. Y., & Aw, M. M. H. Y. (2018). Healthcare encounters in young children: Impact of Teddy bear Hospital, Singapore. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 3(3), 24-30. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-3/OA1055

Santen, L., & Feldman, T. (1994). Teddy bear clinics: a huge community project. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 19(2), 102-106.

Siegel, B., Lewis, H., Bryan, L., & Batisky, D. (2018). The Teddy Bear Hospital as an outreach tool for reducing medical anxiety: A randomized trial. (2018). Pediatrics, 142(1_MeetingAbstract), 783. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.142.1MA8.783

Stewart, M., Brown, J. B., Weston, W., McWhinney, I. R., McWilliam, C. L., & Freeman, T. (2013). Patient-centered medicine: Transforming the clinical method. CRC press.

*Shijia Hu

Faculty of Dentistry,

National University of Singapore

9 Lower Kent Ridge Road #10-01

National University Centre for Oral Health,

Singapore 119085

Email: denhus@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 10 January 2022

Accepted: 22 April 2022

Published online: 5 July, TAPS 2022, 7(3), 23-32

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/OA2742

Tun Tun Naing1, Yuriko Minamoto2, Ye Phyo Aung1 & Marlar Than1

1Department of Medical Education, Defence Services Medical Academy, Myanmar, 2Meiji University, Tokyo

Abstract

Introduction: With the evolution of healthcare needs for the community and the changing trends in medical education in the 21st century, medical educators need to be prepared for their tasks in the coming decades. Medical educator training is crucial but other factors can also affect the development of their competency. This study aims to measure the impact of the medical educators’ training course and find out the key challenges encountered by the medical educators in Myanmar.

Methods: A retrospective quantitative design was conducted on 45 respondents by four levels of Kirkpatrick’s model assessment consisting of 39 statements and 9 items of key challenges, using five-point Likert scale. The item scores were analysed as mean and standard deviation, ‘t’ test and ANOVA were used for relationship between impact of training and demographic background.

Results: There was significant association between the impact of training and the educational background (p=0.03), job position (p=0.02), and academic year attended (p=0.03). The respondents distinctly agreed that the training increased their knowledge and attitudes and that they could apply the learnt lessons practically in their workplace (minimum 3.75±0.60 and maximum 4.28±0.50). Regarding the key challenges, respondents viewed that their institution needed to support more scholarship opportunities and academic recognition; encourage networking and strengthen ICT-based medical education system (minimum 2.55±0.84 – maximum 4.17±0.71).

Conclusion: This study indicates that enhancing the competency of medical educators with medical educator training programs is effective and useful; but inadequacy of institutional support for faculty development and internet facilities posed challenges in the overall faculty development.

Keywords: Medical Education, Faculty Development, Impact of Medical Educator’s Training, Kirkpatrick’s Model, Key Challenges

Practice Highlights

- Medical educator training program is crucial for enhancing competency in medical educators.

- Medical educator training program inspires medical educators to apply their knowledge and skills in their daily departmental activities.

- Beyond training, medical schools must address a balance of capacity for teaching, research and service functions for their faculty.

- Encouraging institutional support such as reward, recognition, and appreciation for their performance should be encouraged as an admirable institutional culture.

- Inadequacy of institutional support for faculty development and internet facilities posed challenges in the overall faculty development.

I. INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, with the evolution of healthcare needs for the community and changes in medical education trends, faculty development in medical education is challenging. Sheets and Schwenk (1990) explained that any activity that enhances the knowledge and skills of individual faculty members are very fundamental to their performance in a department or residency program such as teaching skills, clinical skills, research and administrative skill (Sheets & Schwenk, 1990). Developing the skills of faculty members is not effortless. The ability to teach is not inborn, although the graduate from medical school is supposed to be capable of teaching (McLean et al., 2008). Besides content, teaching involves ‘process,’ and to develop the ‘art’ of teaching, academics required to support (Benor, 2000).

The present-day teacher must be aware of and become part of the far- reaching changes taking place in medical education. Accordingly, in the 21st century, many changes can be found, such as teachers’ conventional roles being shifted to different roles, such as facilitators, curriculum planners, resource developers, educational administrators, and researchers (Crosby, 2000). Significant trends in underpinned theories of medical education are now focusing on patient-centred and culturally competent medical doctors and the ultimate aim of medical education is to improve the patient and community outcomes by promoting competent and caring practitioners (competent medical doctors) (McLean et al., 2008).

According to Harden and Laidlaw (2017), the competencies and attributes expected of an effective teacher includes not only mastery of the content area but also the technical competencies necessary to serve as an information provider, a role model, a facilitator of learning, a curriculum planner, an assessor, a manager and a scholar” (p. 9). Most medical schools worldwide have been implementing specific training for medical educators to develop the necessary skills as medical educators. The study conducted by Steinert (2014), pointed out that nowadays, most medical schools and educational organisations offer various programs and activities in response to educational trends in teaching and assessment for helping faculty members improve their skills as teachers and educators. Additionally, the World Federation of Medical Education (WFME) entails that for a basic standard of staff development: “the medical school must have a staff policy that addresses a balance of capacity for teaching, research and service functions. It also encourages ensuring recognition of meritorious academic activities, with appropriate emphasis on both research attainment and teaching qualifications” (World Federation for Medical Education, 2015).

In Myanmar, there are five civilian medical schools and one military medical school (Defence Services Medical Academy); however, no private medical school exists yet. Defence Services Medical Academy (DSMA), was established on 19th November 1992 in Mingalodon, Yangon and is listed in the World Directory of Medical Schools. The Ministry of Health and Sports, Myanmar, established a medical educator’s training program in 2003 for the medical educators from the civilian medical schools; likewise, the Directorate of Medical Services under the Ministry of Defence also started the medical educator training program for the military medical school in 2011. Both these medical educators’ training programs emphasize on developing the competent skills of medical educators.

Although medical educator training is crucial to improve medical educators’ quality in medical school, other influencing factors can affect the competency of medical educators. The impact of training depends not only on the program design of the training program but also on other factors such as learner characteristics and educational environment (Iqbal & AlSheikh, 2018). In a study conducted by Peeraer and Van Petegem (2012), the faculty members were able to apply teaching strategies and methods in their teaching activities after the faculty development training. Nevertheless, they faced some challenges, such as time constraints and scarce resources that impede their behavioural changes from becoming sustainable.

The medical educator training program in DSMA is a distance learning, diploma course with four face-to-face hands-on workshops. Individual written assignments are given on 10 fundamental modules that provide medical educators with the knowledge and skills about educational psychology, curriculum design and planning, objectives and contents, teaching-learning strategy, teaching-learning media, assessment and evaluation, educational leadership, communication skills, as well as conducting an educational workshop and educational research: throughout the one-year course. Since 2011, nine successive medical educator training courses have been conducted, and approximately 200 medical teachers from DSMA have successfully completed these courses and graduated.

Currently, there is no published evidence-based research investigating the crucial issues to develop competent medical educators in Myanmar. This study intends to focus on the training perspectives and the commitment of institutional support for the development of the medical skills. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to find out the impact of the medical educator’s training course conducted in the military medical school and to explore the key challenges encountered by the trainees.

II. METHODS

A. Research Design

A retrospective design was used to investigate the impact of the medical educator training course and the medical educators’ perception regarding their key challenges. By applying the program theory, a logic model for training program was applied, illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Logic model for training evaluation Adapted from (Rossi, et al., 2004)

B. Kirkpatrick’s Model

To investigate the impact of the training, the Kirkpatrick evaluation measurement tool was utilized (Appendix 1). The four-levels in the Kirkpatrick’s model are: 1) Reaction evaluation, Learning evaluation Behaviour evaluation and Result evaluation (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006).

C. Research Framework

Figure 2. Research framework

D. Data Collection

Survey questionnaires were formulated in three sections. The first session aimed to get demographic information, the second one intended for Kirkpatrick’s evaluation by 39 evaluation questions, and the last was constructed by nine items to explore the critical challenges for medical educators. Questionnaires were developed based on the contents and expected outcomes of the medical educator training course that has been to delivered throughout the courses. These are related to the knowledge, attitude and skills that gained after the course regarding educational psychology, curriculum design and planning, objectives and contents, teaching-learning strategy & media, assessment and evaluation, educational leadership, communication skills, conducting an educational workshop and educational research. Moreover, questionnaires attributed to possible challenges that have been encountered by medical educators were adapted from the research outcomes of Huwendiek et al. (2010). All evaluation questions were self-administered and had the five-point Likert scale items ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). Informed verbal consent was obtained from the respondents in respective of respondents’ autonomy before data collection. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Defence Services Medical Academy, Yangon, Myanmar.

E. Sampling Procedure

Every medical educator is eligible if they had already completed the training and currently engaging in the undergraduate and postgraduate medical education programs at the military medical school, in Myanmar. Among the 120 persons who meet eligibility, approximately 30% of the population (45 participants) responded to the evaluation survey and convenience sampling was practiced.

F. Data Analysis

Data obtained from the survey was entered in Microsoft Excel files and analysed by SPSS software. The item scores of each evaluation were analysed as descriptive analysis such as mean and standard deviation to compare the response rate. The t-test and ANOVA analysis were used to determine the relationship between respondents’ demographic characteristics and Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation results. Descriptive analysis was used to explore the key challenges of medical educators.

III. RESULTS

Forty-five medical educator attendees who satisfactorily completed one of the medical education courses held at DSMA between 2011 and 2019, individually expressed their views on the impact of the medical educator training courses and disclosed the key challenges regarding faculty development in medical education. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17074637 (Naing et al., 2021).

There were 39 evaluation questions, and each evaluation level has specific items, respectively. The internal consistency of each of the scales was examined by using Cronbach’s alpha. The alpha score was satisfactory: 0.65 for reaction evaluation (11 items), 0.86 for learning evaluation (10 items), 0.81 for behavioral evaluation (11items), and 0.84 for result evaluation (7 items).

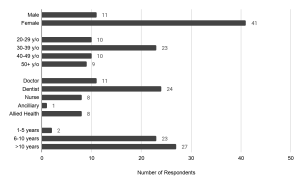

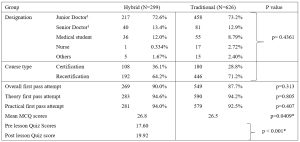

A. Demographic Characteristics

Of the demographic characteristics, three factors (age, gender, and expertise), had no significant association with the impact of the training, but the respondents’ educational background (p=0.03), job’s position (p=0.02), academic year they attended (p=0.03) showed statistically significant association with the impact of training (Table 1). However, the proportionally unequal number of respondents in each group may affect the results.

|

Demographic Characteristics |

Reaction Evaluation |

Learning Evaluation |

Behavioral evaluation |

Result Evaluation |

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

|

|

Age(N=45) |

||||

|

<=40 (N=26) |

4.05±0.20 |

4.08±0.27 |

3.93±0.26 |

4.00±0.35 |

|

41-50 (N=11) |

4.10±0.27 |

4.30±0.44 |

3.99±0.22 |

4.22±0.39 |

|

>= 50 (N=8) |

4.06±0.28 |

4.12±0.38 |

4.01±0.44 |

4.10±0.40 |

|

‘F’ value |

0.17 |

1.55 |

0.28 |

1.30 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.83 |

0.22 |

0.75 |

0.28 |

|

Gender(N=45) |

||||

|

Male(N=33) |

4.06±0.23 |

4.10±0.31 |

3.93±0.26 |

4.07±0.39 |

|

Female(N=12) |

4.09±0.24 |

4.26±0.41 |

4.04±0.36 |

4.08±0.33 |

|

‘t’ value |

-0.474 |

-1.44 |

-1.16 |

-0.07 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.63 |

0.15 |

0.24 |

0.94 |

|

Education(N=45) |

||||

|

Master(N=31) |

4.05±0.27 |

4.09±0.31 |

3.90±0.27 |

3.99±0.37 |

|

Doctoral(N=14) |

4.09±0.20 |

4.25±0.39 |

4.09±0.28 |

4.25±0.32 |

|

‘t’ value |

-0.50 |

-1.49 |

-2.18 |

-2-23 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.61 |

0.14 |

0.03* |

0.03* |

|

Expertise in medical Sciences(N=45) |

|

|||

|

Basic Sciences(N=14) |

4.04±0.26 |

4.10±0.33 |

3.86±0.30 |

4.06±0.33 |

|

Paraclinical(N=16) |

4.09±0.19 |

4.25±0.33 |

4.09±0.24 |

4.20±0.36 |

|

Clinical(N=9) |

4.02±0.28 |

4.03±0.33 |

3.90±0.29 |

3.96±0.40 |

|

Others(N=6) |

4.15±0.21 |

4.10±0.41 |

3.90±0.32 |

3.92±0.45 |

|

‘F’ value |

0.45 |

0.95 |

1.94 |

1.19 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.71 |

0.42 |

0.13 |

0.32 |

|

Job Position (N=45) |

|

|||

|

Assistant lecturer(N=27) |

4.04±0.21 |

4.07±0.27 |

3.93±0.26 |

3.99±0.35 |

|

Lecturer(N=11) |

4.04±0.24 |

4.16±0.35 |

3.90±0.18 |

4.12±0.38 |

|

Associate Professor(N=3) |

4.33±0.29 |

4.70±0.30 |

4.33±0.29 |

4.38±0.35 |

|

Professor(N=4) |

4.11±0.30 |

4.15±0.52 |

4.02±0.56 |

4.25±0.45 |

|

‘F’ value |

1.49 |

3.47 |

2.02 |

1.47 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.23 |

0.02* |

0.12 |

0.23 |

|

Teaching experience (N=45) |

|

|||

|

< = 5 Years(N=17) |

4.02±0.24 |

4.11±0.37 |

3.88±0.27 |

4.13±0.45 |

|

(6-10) Years(N=15) |

4.15±0.19 |

4.12±0.24 |

4.03±0.23 |

4.01±0.32 |

|

(11-15) Years(N=7) |

4.00±0.23 |

4.11±0.28 |

3.90±0.44 |

4.08±0.29 |

|

> = 6 Years(N=6) |

4.07±0.28 |

4.31±0.54 |

4.06±0.24 |

4.04±0.39 |

|

‘F’ value |

1.00 |

0.55 |

1.05 |

0.24 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.41 |

0.64 |

0.37 |

0.86 |

|

Year of Services (N=45) |

|

|||

|

< = 10 Years(N=5) |

4.05±0.13 |

4.16±0.15 |

3.96±0.18 |

4.08±0.27 |

|

(11-15) Years(N=16) |

4.08±0.23 |

4.04±0.29 |

3.90±0.29 |

3.96±0.37 |

|

(16-20) Years(N=12) |

4.08±0.28 |

4.25±0.39 |

4.01±0.27 |

4.16±0.39 |

|

> = 21 Years(N=12) |

4.04±0.23 |

4.16±0.40 |

3.98±0.35 |

4.13±0.40 |

|

‘F’ value |

0.08 |

0.83 |

0.35 |

0.77 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.97 |

0.48 |

0.78 |

0.51 |

|

Academic Year (N=45) |

|

|

|

|

|

2011-2013(N=11) |

4.03±0.25 |

4.25±0.35 |

4.00±0.31 |

4.10±0.32 |

|

2014-2016(N=9) |

4.00±0.34 |

3.93±0.35 |

3.78±0.34 |

3.79±0.45 |

|

2017-2019(N=25) |

4.11±0.17 |

4.17±0.32 |

4.00±0.24 |

4.16±0.33 |

|

‘F’ value |

0.94 |

2.47 |

2.09 |

3.64 |

|

‘p’ value |

0.40 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

0.03* |

(*) means 0.05 level of significant

Table 1. Relationship between demographic characteristics and Kirkpatrick’s evaluation

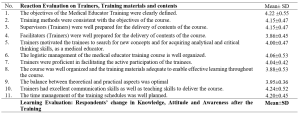

B. Kirkpatrick’s Four Level of Evaluation

When looking at the reaction evaluation, most of the respondents gave favourable agreement on the management of training, teaching skills of the trainers, and training methods, however, there was relatively weakness in the proper preparation of training contents by facilitators (3.86±0.45), providing training materials (3.88±0.53). Looking upon the learning evaluation responses, all of the respondents expressed a high level of satisfaction on their understandings and awareness. Regarding learning behaviour, majority agreed that they can apply their learning to their workplace but comparatively lower response score was found in planning educational research (3.84±0.56), how to apply educational theories in medical education practices (3.84±0.52) and arrange an educational workshop programme (3.75±0.60). Although the medical educator training affects the respondents to get better improvement in most faculty development activities, there is still a need to develop the participation of respondents in research development activities with comparatively lowest evaluation scores of (3.80±0.66).

Table 2. Kirkpatrick’s Four Level of Evaluation of Medical Educator Training

C. Key Challenges in Faculty Development

It was found that majority of the evaluation scores for the statement items in the faculty development area were much lower than the scores for the items in the training’s impact. The most noticeable and lowest scores were found in the item of financial investment of medical educators (2.68±0.73), research collaboration in other universities (2.60±0.88) and networking with the international university for career development of medical educators (2.55±0.84). However, they agreed that the currently used undergraduate curriculum of the institution is appropriate for them to practically apply their pedagogic skills gained from the training course(4.17±0.71).

|

No. |

Statement |

Mean±SD |

|

1. |

Depending on the performance in faculty development activities, our institution appreciates rewards for medical educators as an institutional policy. |

2.80±0.75 |

|

2. |

Medical educators in our university have the opportunity to apply the Institutional scholarship program for research and carrier development. |

2.84±0.79 |

|

3. |

The financial investment for medical educators in our institution is acceptable in the current situation. (e.g. teaching-learning materials, research facilities, ICT based technology) |

2.68±0.73 |

|

4. |

There are adequate networks and collaboration with an international university to promote the carrier development of medical educators. (e.g. MOU) |

2.60±0.88 |

|

5. |

ICT based medical education system in our university is well functioned and applicable. |

2.73±0.80 |

|

6. |

The number of medical educators in our university is sufficient to achieve the mission of our university. |

2.71±0.84 |

|

7. |

The institutions’ current undergraduate curriculum is appropriate for us to practically apply the pedagogic skills gained from the training course. |

4.17±0.71 |

|

8. |

Research development activities of our university, including research funding, research skills of medical educators, and research facilities, are well functioning. |

2.80±0.78 |

|

9. |

The research collaboration with other universities or research centers to promote research innovation is acceptable. |

2.55±0.84 |

Table 3. Key Challenges in faculty development in medical education by respondents

IV. DISCUSSION

This study investigates the medical educator training program, which aims to develop the competency skills of medical educators who are involved in the faculty development activities at DSMA, Myanmar. Regarding the overall impact of the training, the respondents expressed their positive perception on the organisation of the program; the training improved their knowledge and attitudes as a medical educator; and it was practically applicable in their daily work. The positive perception of the training was not surprising because most of the trainees voluntarily attended the course and were highly motivated to accomplish self- improvement after attending the course. The findings are consistent with another study where ‘overall satisfaction with faculty development programs was high, and they consistently found the program helpful, enjoyable and relevant to their objectives’ (Steinert et al., 2016, p.779). Similarly, another study done by Yolsal et al. (2003) showed that the participants who enrolled in the similar training of trainers (TOT) course explored positive perception, and they agreed it was required to be acquainted with those kinds of instructional practices (Yolsal et al., 2003). The possible reason for the respondents’ satisfaction with the impact of training in the current study, could also be due to the organized training preparation and training context and, the course itself used mainly a distance learning format with flexible training schedules for them when compared to other full-time courses in other specialties. It was also found that significant improvements in self-efficacy of medical educators in the domain of the teaching relevant subject contents and developing creative ways to cope with system constraints after experiencing 12 months faculty development program in Bhutan (Tenzin et al., 2019).

In this study, for learning evaluation, most respondents believed that they gained in terms of knowledge, attitude, and skills and that it had an impact on the teaching effectiveness. It revealed that most of the medical educators gained benefits after the training, and the increase in confidence facilitated them to become more involved in participating in faculty development activities and curriculum planning activities. Similarly, F.J. Ciller and N. Herman explained that as a goal of an educational development program, changes in attitudes and perception serves as a foundation for further changes in behaviour (Cilliers & Herman, 2010).Even more, the review articles of Steinert et al. (2016) highlighted most of the faculty development interventions focus on teaching effectiveness by improving their teaching skills, assessment skills, designing curriculum, and educational leadership skills (Steinert et al., 2016).

When analysing the relationship between the various demographic background and impact of the training, it was revealed that the job position, educational background, and difference in academic year among the respondents were significantly associated with the impact of training. There might be many possible reasons why this was significant. For example, the course preparation, the changes in placement of trainers in several years might also be a possible issue, and variation in individual performance also considered. However, in this survey, those factors were not explored. Fishbein et al. (2003) explained that interpersonal variation and the organization’s favorable situation could be impact factors for behavioural change at the organization level (Fishbein et al., 2003).

In this study, although the self-reported changes showed self-actualization in individual performance to some extent, respondents are not contented with their learning environment in terms of institutional support. Institutional support plays a vital role in faculty development in medical education and every institution can meet its institutional mission and goals by enabling its faculty member to fulfil their particular purposes as teachers, scholars, and leaders according to the research outcome (Boucher et al., 2006). Moreover, Steinert pointed out that many factors are impeding the faculty development, such as unsupportive leadership, resistance to change, lack of faculty motivation, and the unwillingness of faculty to acquire the teaching skills and knowledge (Steinert, 2000).

On exploring the critical challenges of the medical educators, all the respondents believed that their institution should support more scholarship opportunity, academic recognition, networking with other universities in terms of research and professional development, and ICT-based medical education system. According to the survey of (Huwendiek et al., 2010) 806 medical educators from Association for Medical Education Europe (AMEE) revealed that the critical challenges of medical education were lack of academic recognition (40%), funding (36%), faculty development (24%), time for medical education issues (22%), and institutional support (21%) (Huwendiek et al., 2010).

Therefore, to accelerate the faculty development as a holistic approach, it is needed to consider not only training for faculty members but also other factors reward and recognition, ICT system, and networking. This requisite is not only in a military medical school, but internationally most medical schools are trying to support their faculty in accordance with the staff policy requirements as stated in the WFME Global standards for Quality improvement. However, the current research could gather only some self-reported changes in behaviour and whether the changes actually occurred in the workplace has not been proven by observation. Nevertheless, as the opinions were obtained from closed ended questionnaire statements, a further exploratory qualitative study is needed to obtain accurate information on the magnitude of the problem and the specific areas that needed further support from the institution.

V. CONCLUSION

This study revealed the medical educator training could improve their required knowledge, attitude, and skills to practice in the teaching environment, the fundamental need for educational leadership, educational research, and communication skills in the health-care setting. The medical educators who need to be competent could not be motivated only from the training without institutional support. The respondents believed that their institution should encourage institutional support in terms of reward, recognition, scholar allowance, and collaboration with other academic institutions to promote research culture and professional development, ICT-based medical education.

To conclude, the findings of this study exclusively show that military medical schools in Myanmar still need to emphasize the professional identities of medical educators by encouraging institutional support, not just by only focusing on the faculty development training as a mandatory by institutional policy.

Notes on Contributors

Tun Tun Naing reviewed the literatures and developed the conceptual framework and conducted the data analysis and wrote the discussion and conclusion. Finally, he developed the manuscript to submit to TAPS.

Yuriko Minamoto was involved in the formulation of research question and research framework to conduct the research systematically, application of evaluation tools and technique and, proofreading of original thesis and the manuscript.

Ye Phyo Aung participated in the research in the writing of research methodology session, conducted the data collection, and supported choosing research design, proper sampling methods and data collection tools and technique and proofreading of manuscript.

Marlar Than supported the construction of survey questionnaires which is the back bone of the evaluation research and contribute to proofreading of current manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of the Defence Services Medical Academy, Yangon, Myanmar. (7 / Ethics 2019).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare repository, http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17074637

Acknowledgement

I would also like to express my gratitude to Japanese Government through the Japan International Cooperation Center (JICE) for their support to conduct this research project for completion of master thesis program at Meiji University.

I would like to express my special thanks to my colleagues, and without their support, the survey of my research would not have been achieved. I am indebted to all medical educators from Military Medical Service, Myanmar, who help me respond to my survey sharing with their valuable opinions and experience.

Funding

Conducting the research was operated during the study period supported by JDS Program under the JICA. For this publication , it is conducted for personal and professional development and no funding is involved.

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in the current research.

References

Benor, D. (2000). Faculty development, teacher training and teacher accreditation in medical education: Twenty years from now. Medical Teacher, 22(5), 503-512. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590050110795

Boucher, B., Chyka, P., Fitzgerald, W., Hak, L., Miller, D., Parker, R., Phelps, S., Wood, G., & Gourley, D. (2006). A comprehensive approach to faculty development. American Journal of Pharma- ceutical Education, 70(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj700227

Cilliers, F., & Herman, N. (2010). Impact of an educational development programme on teaching practice of academics at a research‐intensive university. International Journal for Academic Development, 15(3), 253-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144x.2010.497698

Crosby, R. (2000). AMEE Guide No 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer – the twelve roles of the teacher. Medical Teacher, 22(4), 334-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/014215900409429

Fishbein, M., Hennessy, M., Yzer, M., & Douglas, J. (2003). Can we explain why some people do and some people do not act on their intentions? Psychology, Health &Amp; Medicine, 8(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354850021000059223

Harden, R. M., & Laidlaw, J. M. (2017). Essential Skills for a Medical Teacher (2nd ed., pp. 9). Elsevier.

Huwendiek, S., Mennin, S., Dern, P., Ben-David, M., Van Der Vleuten, C., Tönshoff, B., & Nikendei, C. (2010). Expertise, needs and challenges of medical educators: Results of an international web survey. Medical Teacher, 32(11), 912-918. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.497822

Iqbal, M., & AlSheikh, M. (2018). Factors affecting the transfer of training to the workplace after a faculty development programme: What do trainers think? Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 13(6), 552-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2018.11.001

Kirkpatrick, D., & Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels (3rd ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publisher.

McLean, M., Cilliers, F., & Van Wyk, J. (2008). Faculty development: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Medical Teacher, 30(6), 555-584. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802109834

Naing, T. T., Minamoto, Y., Aung, Y. P., & Than, M. (2021). Faculty development of medical educators: Training evaluation and Key Challenges. [Dataset].

Figshare. http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17074637

Peeraer, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2012). The limits of programmed professional development on integration of information and communication technology in education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(6), 1039-1056. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.809

Rossi, P., Lipsey, M., & Freeman, H. (2004). Evaluation: A Systematic Approach (7th ed.). Sage.

Sheets, K., & Schwenk, T. (1990). Faculty development for family medicine educators: An agenda for future activities. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 2(3), 141-148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401339009539447

Steinert, Y. (2000). Faculty development in the new millennium: key challenges and future directions. Medical Teacher, 22(1), 44-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590078814

Steinert, Y. (2014). Faculty Development in Health Profession: A Focus on Research and Practice (1st ed.). Springer.

Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Anderson, B., Barnett, B., Centeno, A., Naismith, L., Prideaux, D., Spencer, J., Tullo, E., Viggiano, T., Ward, H., & Dolmans, D. (2016). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Medical Teacher, 38(8), 769-786. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2016.1181851

Tenzin, K., Dorji, T., Choeda, T., & Pongpirul, K. (2019). Impact of faculty development programme on self-efficacy, competency and attitude towards medical education in Bhutan: A mixed-methods study. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 468. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1904-4

World Federation for Medical Education. (2015, January 1). Basic medical education WFME global standards for quality improvement. https://wfme.org/download/wfme-global-standards-for-quality-improvement-bme/.

Yolsal, N., Bulut, A., Karabey, S., Ortayli, N., Bahadir, G., & Aydin, Z. (2003). Development of training of trainer’s programmes and evaluation of their effectiveness in Istanbul, Turkey. Medical Teacher, 25(3), 319-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159031000092779

*Tun Tun Naing

No. 94, D-1, Pyay Road,

Mingaladon Township

Yangon, Myanmar

Postal code – 11021

+95 95053402

Email: tuntunnaing@dsma.edu.mm, drhtun1984@gmail.com

Submitted: 30 May 2021

Accepted: 8 April 2022

Published online: 5 July, TAPS 2022, 7(3), 10-22

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/OA2539

Hanyi Li1, Elaine Li Yen Tan1,3, Mun Loke Wong2 & Marianne Meng Ann Ong1,3

1National Dental Centre Singapore, Singapore; 2Faculty of Dentistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Oral Health Academic Clinical Programme, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: As young healthcare professionals (HCPs) enter the workforce, they find challenges adapting as academic training and workplace settings often do not mirror each other. Mentorship is a possible solution to help bridge this transition. The aim of this study was to gather information from HCPs with regards to their views towards mentorship as a strategy to help in the transition of newly qualified HCPs from study to work.

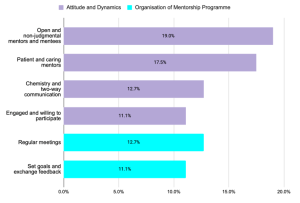

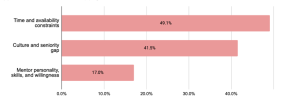

Methods: Two 3-hour interactive workshops entitled “Bridging the Study-Work Chasm” were organised, and participants were invited to complete a survey voluntarily after the workshop. The survey comprised questions regarding the benefits of mentorship, qualification of mentors, time commitment for mentoring, elements of an effective mentorship programme, and barriers to its effectiveness. The anonymised responses were analysed descriptively.

Results: Fifty-two out of 62 participants from various healthcare backgrounds completed the survey. 96.2% of respondents felt a study-work chasm exists in the healthcare workplace with 90.4% indicating that a mentorship programme would help to bridge the chasm. More than 70% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that mentoring would boost confidence, reduce anxiety, and aid in study-work transition. It was identified that to produce a more effective mentorship programme, time commitment, training, and proper organisation of the programme would be necessary.

Conclusion: It was perceived that a mentorship programme can help to bridge the study-work chasm in the healthcare landscape in Singapore, and will best serve mentors and mentees by committing the proper time and training to ensure its effectiveness.

Keywords: Training-Work Transition, Graduate, Healthcare Professionals, Mentorship

Practice Highlights

- Despite receiving extensive training during their education, healthcare professionals still experience many challenges as they enter the workforce.

- Globally it has been reported that differences in training and workplace demands, coupled with the need to take direct responsibility for patients, propagate anxiety and perceived incompetence in fresh graduates. This could result in compromised work performance and patient outcomes.

- A study-work chasm exists in the healthcare work space, and should be addressed.

- Mentorship was shown to be accepted as a popular solution amongst healthcare workers in Singapore, and the benefits were discussed.

- Elements of a good mentorship programme as well as challenges in setting one up were identified, laying the groundwork for future implementation of such programmes in local public healthcare institutions.

I. INTRODUCTION

Healthcare professionals (HCPs) are known to receive extensive training during their pre-qualification education. However, there still exists many challenges as they enter the workforce. These include increasing workload, encountering patients with more complex conditions, generational diversity in the workforce, performance anxiety, and bullying when transitioning to the workforce (Hofler & Thomas, 2016). While facing these challenges in a new working environment marks the beginning of a fresh process of learning, there are indications that this may be more than what newly qualified professionals can cope with (Teunissen & Westerman, 2011).

There are several contextual differences between pre-employment learning in the university and post-employment learning in the workplace. Fundamentally, the focus of education and real-world practice are different. The commonplace practice of test-taking in school focuses on knowledge retention, with minimal consideration for practical value in the workplace (Lave & Wenger, 1991). A good example of this is the learning of ethical guidelines, which can be easy to regurgitate in school assignments and tests, but are far more difficult to apply on the job (Le Maistre & Paré, 2004). In school, tasks and assignments follow a certain syllabus and scope, which are more structured and predictable than what is expected at the workplace. Similarly, these tasks and assignments in school are indicators of performance and avenues for feedback, while at the workplace such similar opportunities are limited (Wendlandt & Rochlen, 2008).

Healthcare training has had elements of practical application, but the adequacy of these exposures is questionable. Clinical shadowing and observation are known to be helpful, but cannot take the place of actual hands-on clinical experience (Brennan et al., 2010). With increased patient safety concerns, there has also been a shift towards simulation, which reduces meaningful contact with patients and poses challenges when students are expected to ultimately transfer their learning to real-life practice (Bleakley & Bligh, 2008).

The security of observing from a distance and the safe environment for experimentation and reflection that students experience in school have to be left behind as they enter the workplace, apply textbook knowledge in real-life situations, and deal with workplace systems and politics (Le Maistre & Paré, 2004). Efforts to prepare for this transition are misplaced (Kilminster et al., 2011), and the training and educational opportunities aimed to help with this transition, such as those in the transitional year, have been lacklustre and ineffective (Lambert et al., 2013). Therefore, a study-work chasm exists in many places, and is a pertinent and critical issue that requires addressing.

Among efforts to help in the transition of students to new HCPs at the workplace, mentorship has been seen as a possible solution (Andrews & Wallis, 1999; Dalgaty et al., 2017). Mentorship, as previously defined by The Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education in the United Kingdom, is the guidance in “the development and re-examination of their own ideas, learning, and personal and professional development” by “listening and talking in confidence to the mentee” (Oxley & Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education, 1998). It has also been built into medical practice guidelines, such as that in the UK (General Medical Council, 2012), as a key element in training and professional development.

Mentorship has been seen as a viable approach not only to address any gaps in professional skills, but also aid junior healthcare workers in personalised professional development in the workplace, to enhance job satisfaction, motivation, and self-esteem (Souza & Viney, 2014). The role of a mentor in medical education is to help mentees identify areas of strength and weaknesses in a comfortable and safe learning environment, offer guidance and advice, and motivate and support them to work towards their personal long-term goals (Burgess et al., 2018). Mentors have roles overlapping that of coaches and advisors in medical education. However, coaches tend to focus more on skills or knowledge-based content, and may have a relationship that is of shorter duration and of less depth than between mentors and mentees (Lin & Reddy, 2019). Advisors often oversee a group of individuals in an organisation. Therefore, they develop a more structured relationship compared to that between mentors and mentees, and tend to work towards an outcome based on the needs of the organisation (Hastings & Kane, 2018). Thus, mentoring has been a widely recognised method of helping young people learn, demonstrate their abilities and potential, as well as develop their identity (Fuller & Unwin, 1998). This is extensively explored and studied in many healthcare institutions and systems today.

The aim of this study was to gather information from HCPs about their views towards mentorship as a strategy to help in the transition of newly qualified HCPs from study to work.

II. METHODS

This was a descriptive study on the perceptions of the study-work chasm by HCPs. The protocols were sent to SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (References: 2017/2687 and 2021/2044) and they were deemed exempt from review.

Two three-hour interactive workshops, entitled “Bridging the Study-Work Chasm”, were held in September 2017 and 2018. The workshops invited participation from HCPs in SingHealth, one of the three public healthcare clusters in Singapore.

Each 3-hour workshop comprised two short talks on ‘Is there a Chasm?’ and ‘Bridging the Chasm’, followed by small-group discussions, then sharing and discussions with the large workshop group. A round-up and summary was done by the respective facilitator after each large-group discussion.