Impact of Scholarly Project on students’ perception of research skills: A quasi-experimental study

Submitted: 22 January 2022

Accepted: 4 May 2022

Published online: 4 October, TAPS 2022, 7(4), 50-58

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-4/OA2748

Nguyen Tran Minh Duc, Khuu Hoang Viet & Vuong Thi Ngoc Lan

University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Abstract

Introduction: The Scholarly Project provides medical students with an opportunity to conduct research on a health and health care topic of interest with faculty mentors. Despite the proven benefits of the Scholarly Project there has only been a gradual change to undergraduate medical education in Vietnam. In the academic year of 2020-2021, the University of Medicine and Pharmacy (UMP) at Ho Chi Minh City launched the Scholarly Project as part of an innovative educational program. This study investigated the impact of the Scholarly Project on the research skills perception of participating undergraduate medical students.

Methods: A questionnaire evaluating the perception of fourteen research skills was given to participants in the first week, at midterm, and after finishing the Scholarly Project; students assessed their level on each skill using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (lowest score) to 5 (highest score).

Results: There were statistically significant increases in scores for 11 skills after participation in the Scholarly Project. Of the remaining three skills, ‘Understanding the importance of “controls”’ and ‘Interpreting data’ skills showed a trend towards improvement while the ‘Statistically analyse data’ skill showed a downward trend.

Conclusion: The Scholarly Project had a positive impact on each student’s perception of most research skills and should be integrated into the revamped undergraduate medical education program at UMP, with detailed instruction on targeted skills for choosing the optimal study design and follow-up assessment.

Keywords: Study Skills, Scholarly Project, Undergraduate, Medical Education, Self-Assessment

Practice Highlights

- The Scholarly Project is an essential component of the undergraduate medical education curriculum.

- Targeted researching skills is a valuable method to optimise competency-based criteria.

- The initial choice of study design is important to the overall research skill self-perceptive improvement.

I. INTRODUCTION

Scholarly Project has emerged as an essential component of the modern undergraduate medical curriculum. This entails mentored study in a single topic area and may include classical hypothesis-driven research, literature reviews, or the creation of a medically-related product (Boninger et al., 2010). By researching a topic, designing and implementing experiments and analysing the results, students not only gain knowledge and experience but also essential skills including critical thinking, time management, collaboration, information technology and confidence, all of which benefit their academic endeavours and result in higher undergraduate graduation rates (Bickford et al., 2020; Carson, 2007). Furthermore, the Scholarly Project program, which allows students to learn about research, was rated positively by most undergraduates. In addition, it provides faculty members with assistance in their research projects and the chance to influence future generations (Dagher et al., 2016). It has also been noted that the process of exposing undergraduate students to research benefits the researchers who take part as instructors by refining and shaping their scientific minds (Zydney et al., 2002).

The number of research studies with Vietnamese authorship published in ISI-indexed journals increased considerably between 2001 and 2015, with an annual growth rate of 17%. However, the majority of this growth (77%) was accounted for by international collaboration research rather than domestic-only projects, especially in the clinical medicine area. Thus, scientific research in Vietnam had not changed considerably or achieved independence in this field (Nguyen et al., 2016).

In the academic year of 2020-2021, the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (UMP), Vietnam, pioneered the launch of a one-year Scholarly Project for all fifth-year medical students. This medical student population is the first generation to learn under the refreshed Undergraduate Medical Curriculum of the UMP and the first class to experience the Scholarly Project. Undergraduate research experiences are characterised by four features: mentorship, originality, acceptability, and dissemination (Kardash, 2000). Assessment of undergraduate research experience, which determines whether students gained any research skills (such as identifying the research question, collecting data, thinking independently and creatively) is best performed after completing the research program (Blockus et al., 1997; Manduca, 1997). The quasi-experimental work presented here provides one of the first investigations into how the Scholarly Project at the UMP, Vietnam, impacted on the participating students’ perception of how their medical research skills improved in the academic year of 2020-2021.

II. METHODS

A. Description of the Scholarly Project

The Scholarly Project is a compulsory academic module that aims to enable fifth-year medical students to conduct medical research early in their careers. It provides these students with an active experience in conducting a research project with faculty members starting at the beginning of the fifth academic year. The data reported here were collected from medical students and mentors who participated during the 2020-2021 academic year.

For most medical students, the Scholarly Project provides the first exposure to the field of research. There are 48 groups of nine medical students, including one team leader, one secretary, and team members, with one faculty mentor. Medical students are expected to contribute actively to the best of their ability in committed teamwork and an ethical manner.

Members of the faculties of Medicine and Public Medicine who have active ongoing research projects are eligible to participate in the Scholarly Project. Faculty members act as mentors to the students and facilitate the students’ learning process by providing supervision, guidance, and support. In addition, members should allocate suitable tasks for each student based on their skills, expertise, interests, and background.

B. Scholarly Project Steps

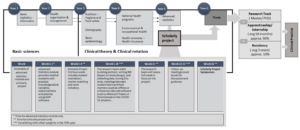

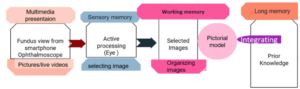

1) Student orientation: Student orientation occurred in the first week, informing students of the program’s procedure, and their roles and responsibilities (Figure 1). Also, in the first week, the medical student curriculum included a medical research course, describing the formation of research ideas, study design and statistics, literature searching and referencing, and research ethics. Students were also provided with important dates and deadlines for the Scholarly Project stage.

2) Matching: Matching is the process of pairing students with project mentors. From the first weeks of the Scholarly Project, each student team is required to create a team profile on the university website, including the scientific interest, skill, and research fields of interest for each team member. Each medical student team then chose a mentor from a provided list, taking into account medical research fields and their research curriculum vitae. Each team picked up to 2 mentors, in order of preference. After the deadline, mentors chose which team they would like to work with based on the students’ choice; this process continued until all teams were paired.

3) Work initiation: Students were expected to initiate contact with the faculty member after being notified via the university website that they have been matched to a project. During the second week of the Scholarly Project, faculty members and students discussed the research project, and the roles and responsibilities. Upon finalising the agreement between the two parties, students completed a meeting report form, which was signed by both the mentor(s) and the team leader. During online learning periods due to COVID-19, online meetings were encouraged, along with completion of the meeting report form. This meeting report form included information about topics discussed during the meeting, future work, each student’s role in the research project, and confirmed the next appointment date. Student teams and faculty members scheduled meetings based on the design of their study. In follow-up meetings, faculty mentors continued to discuss and evaluate the medical students’ work, and further plans were discussed. There was no upper limit for the number of meetings. However, there was a second required meeting at the third week of the Scholarly Project, which was nearly the end of the modules, for the research team to update the collected data, trouble-shooting solutions, or feedback.

4) Presentation: In the final week of the fifth-year curriculum, a Scholarly Project Symposium provided the opportunity for research teams to present their project findings. This allowed the scientific committee to evaluate both the performance of each student and the research project in general. Another aim of the symposium was for medical students to learn and share their findings with other teams, and the presentation also provides a valuable reference for the subsequent classes.

Figure 1. Integration of the Scholarly Project into the new reformed undergraduate and postgraduate medical curriculum in Vietnam.

C. Study Setting and Participants

This one-group pretest-posttest study had a quasi-experimental design. Research skills assessed were chosen based on fourteen individual research skills (Kardash, 2000). The questionnaire has been used previously, with a Cronbach’s alpha calculated at 0.9 and item-total correlation varied between 0.49 to 0.76 (Kardash, 2000). The questionnaire was translated into Vietnamese, then the local language version was pre-tested and the final text was amended as necessary. The translation process was undertaken in accordance with Guidelines for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process (Beaton et al., 2000). Translations were evaluated and compared with the original questionnaire by the Education and Research Council of the UMP to ensure accuracy of the Vietnamese version prior to study initiation. Medical student surveys were administered during the first week of the Scholarly Project and students were asked to indicate their current level of performance for each skill and the extent to which they hoped that the project would develop each skill on a 5-point Likert scale from 1–5 (where higher scores indicate greater skill level). Surveys were repeated at midterm and during the last week of the Scholarly Project module; at these times the students used the same scale to rate the extent to which they felt capable of performing each skill and how they believed the internship had developed their skills in general. Medical students had to provide informed consent on the first page of the electronic form before accessing the rest of the questionnaire.

D. Statistical Analysis

Raw data were extracted from the online survey link for each participating medical student and saved in Excel sheets. R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) was applied to analyse data. First, scores for each skill at baseline were compared with those obtained after project completion using a paired t-test (Student’s t-test). The same method was used to compare expected skill level evaluated at baseline and the actual skill level rating at the end of the Scholarly Project. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

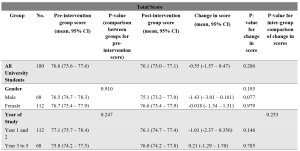

III. RESULTS

A. Response Rate and Participant Data

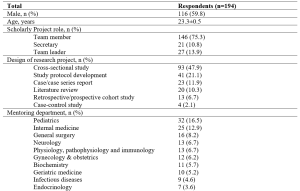

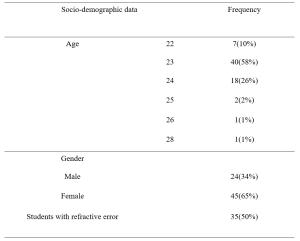

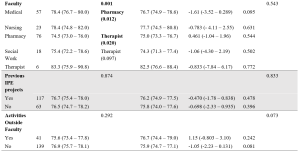

Of 384 students participating in the Scholarly Project, 194 (50.5%) completed the survey. The majority of participants were male (60%) and had the role of project team member (75.3%) (See Table 1). The most common Scholarly Project design was a cross-sectional study (47.9%), followed by study protocol development (21.1%), case/case series report (11.9%), and literature review (10.3%) (Table 1). Twenty-one different departments with a wide range of specialties provided scientific mentors for the Scholarly Projects undertaken by 48 research groups (See Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and project characteristics for survey respondents.

Values are mean ± standard deviation, or number of respondents (%).

B. Research Skills at Baseline, Midterm and Project Completion

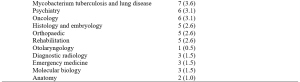

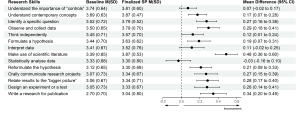

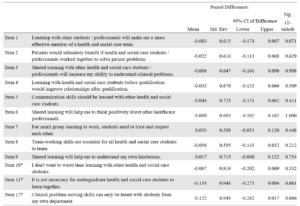

At baseline, self-rated competency was highest for ‘Understand the importance of “controls”’, ‘Understand contemporary concepts’, ‘Identify a specific question’, and ‘Observe and collect data’ (Figure 2). All skills had self-evaluating levels above “moderate” (score of >3), except for ‘Write research for publication’ (mean score 2.696). Students expected that all skills would increase after participating in the Scholarly Project (p<0.001).

In the midterm survey, five skill groups showed significant improvement from baseline (Figure 2). These were ‘Make use of scientific literature’, ‘Identify a specific question’, ‘Observe and collect data’, ‘Relate results to the “bigger picture”’, and ‘Orally communicate research project skills’. Conversely, there was a significant decrease in self-rated skill for ‘Statistically analyse data’ and ‘Interpret data skills’, while other skill ratings were stable (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Change in self-rated medical research skills of 194 participants from baseline to the midterm of the Scholarly Project

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval

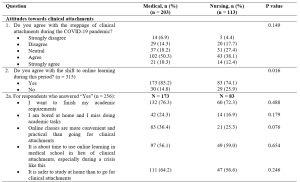

At the completion of the Scholarly Project, the five skills that showed improvement at the midterm assessment showed continued improvement, and another six skills had also improved significantly compared with baseline (Figure 3). However, scores for ‘Understand the importance of “controls”’, ‘Interpret data’ and ‘Statistically analyse data” did not change significantly from baseline, and the mean score for the latter parameter was actually slightly below baseline (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Change in self-rated medical research skills of 194 participants from baseline to completion of the Scholarly Project (SP)

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval.

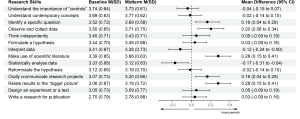

Looking more closely at analytical skills relating to six types of study design showed that self-rated skill for the ability to interpret data for a literature review decreased significantly, as did self-rated skill scores for statistically analyse data in relation to study protocol development and literature review (Table 2). In contrast, there was a significant improvement in self-rated skill for data interpretation for cross-sectional studies and for statistical analysis of data in cohort studies (Table 2).

Table 2. Self-evaluated skill level scores for ‘Interpret data’ and ‘Statistically analyse data’ from baseline to completion of the Scholarly Project

Values are mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.05 vs baseline.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Impact of Scholarly Project on Students’ Perception of Research Skills

Our results show that ratings for most skills increased during and after the Scholarly Project. Increases in ratings for ‘Identifying a specific question’, ‘Orally communicate research projects’, and ‘Relate results to the “bigger picture”’ in our study were consistent with data from Schor et al. (2005), who reported that the Scholarly Project could be beneficial by fostering analytical thinking skills, improving oral communication skills, and enhancing skills for evaluating and applying new knowledge to their profession (Schor et al., 2005). A significant increase in ‘Make use of scientific literature’ in our study reflects the idea-forming process at the study design stage of the Scholarly Project, during which students could practice the ability to read and critically evaluate medical literature. These are essential components of undergraduate medical education, irrespective of whether students intend to pursue a career in academic medicine or in public or private clinical practice (Holloway et al., 2004).

B. Data-related Skills and the Concept of a Control Group

The two skills of ‘Statistically analyse data’ and ‘Interpret data’ are introduced mainly in the Advanced Statistics Module with a training period of 2 weeks before starting the Scholarly Project, and briefly presented in the ‘Basic statistics informatics’ module during the first year of training and in the ‘Basic epidemiology’ module during the third year of the undergraduate curriculum. Therefore, baseline assessments in our study took place after the Advanced Statistics Module, which could have influenced ratings on the above skills. Given that our midterm assessment was performed at a time when most students had not had the opportunity to practice these skills, there may have been a negative impact on self-evaluation. The change in scores for ‘Statistically analyse data’ and ‘Interpret data’ at the midterm assessment was therefore influenced by an external factor (the Advanced Statistics Module) and an internal factor (the Scholarly Project). Therefore, future assessments of the impact of the Scholarly Project on learning should not have the quasi-experimental design used here, but instead, use an interrupted time-series design. This will mean that several surveys would be conducted before starting the Advanced Statistics Module, with the aim of eliminating confounding factors.

The final assessment showed significant improvements in scores for ‘Statistically analyse data’ and ‘Interpret data skills’ compared with the midterm survey. When applied in students’ projects, the improvement of these two skills indirectly supported the aforementioned context. This highlights the value of active learning compared with passive learning. It has conclusively been shown that cramming statistical knowledge means that students do not understand basic concepts to apply appropriately (Leppink, 2017). As noted by Leppink, statistics should be integrated into medical subjects; familiarity with these subjects and the repeated use of these skills provides opportunities to develop statistical skills. The Scholar Project is a typical example of this trend. However, only the ‘Statistically analyse data skill’ showed a downward pattern, while the ‘Interpret data skill’ increased slightly, suggesting that the Scholarly Project should focus more on these skills. Additional studies that take these variables into account are needed.

The control group concept is taught in Basic Epidemiology during the third year of Basic Science and the first sessions of the Scholarly Project. The control group has a pivotal role in study design should have elements that match the experimental group’s characteristics, except for the intervention/variable applied to the latter (Kinser & Robins, 2013). This scientific control group enables the experimental study of one variable at a time, and it is an essential part of the scientific method. Two identical experiments are carried out in a controlled experiment: in one of them, the treatment or tested factor is applied (experimental group), whereas in the other group (control), the tested factor is not applied (Pithon, 2013). However, due to the limitation that only four respondents had a project with a case-control study design, the ‘Understand the importance of “controls”’ skill only showed a modest improvement, despite having been taught previously, which is similar to a previous undergraduate research study (Kardash, 2000). Compared with cross-sectional study design, which was the most popular design for studies in this Scholarly Project, case-control studies often required a greater amount of human and facility resources. We suggest that a case-control study with a small sample size of 10–20 could be a suitable study design for medical students to understand how best to conduct research with a control group.

Of the 194 respondents in our study, 56.7% of the cohort should have been able to fully experience all fourteen of the skills assessed. In contrast, those who participated in study protocol development, literature review, and case/case series report projects had limited opportunities to practice analytical skills. Similar to our findings, a previous study demonstrated that only 13% of 475 projects conducted by medical students contained four main research skill areas, including research methods, information gathering, critical analysis and review, and data processing (Murdoch-Eaton et al., 2010). Furthermore, the COVID-19 outbreak during the academic year 2020-2021 significantly impacted the originally planned Scholarly Project data collection process. As a result, some research teams switched to more feasible design studies such as study development or literature review, which potentially influenced the two skills of statistical analysis and data interpretation skills. Therefore, it could be hypothesised that these conditions are less likely to occur if participants recognise the skills required for research before designing the study protocol. Thus, there is room for further progress in determining the optimal project descriptions provided to medical students participating in the Scholarly Project to allow them to benefit from the research opportunities and fully develop essential skills.

C. The Role of Scholarly Project in Medical Education in Vietnam

This Scholarly Project is an essential step in curriculum reform for Vietnam’s medical education system. In the last two decades, medical educators in Vietnam have collaborated to promote the social trend for undergraduate medical education, and identify the goals and outcomes of learning from medical graduates in expected knowledge, attitudes, and skills (Hoat et al., 2009). Furthermore, Vietnamese policymakers created an environment that enabled academic innovation by implementing the necessary changes to national university autonomy policies (Duong et al., 2021). These policies enable public universities to be financially independent, manage their operation and human resources, prioritise technology, and develop new curricula. The Scholarly Project helps to train physicians who are better prepared to meet patient requirements and health needs (Fan et al., 2012). Based on competency in medical education, the Scholarly Project focuses on outcomes, emphasises the application of knowledge and practice, and promotes greater learner-centeredness (Carraccio et al., 2002; Frank et al., 2010; Iobst et al., 2010). In addition, the Scholarly Project helps to reduce the time spent in passive lectures, which can negative affect medical students (Deslauriers et al., 2019; Schwartzstein et al., 2020; Schwartzstein & Roberts, 2017). Instead, students are encouraged to explore research topics based on their interests, human and institutional resources, and university mentors’ guidance and follow-up. Compared with the large class sizes from Vietnam’s traditional teaching method, the Scholarly Project (with an average of eight students and one mentor) provides low faculty-to-students ratios, creating desired small group learning. Starting for the first time in the 2020-2021 school year, Scholarly Project had to adapt to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with two periods of online learning required in September 2020 and May 2021 due to local COVID-19 outbreaks. To help manage this, the university applied for technical assistance from Microsoft Office 365 with a full-access subscription to maintain the scheduled small group meetings between students and their mentors while optimising social distancing (Duong et al., 2021).

We recommend introducing the 14-skill questionnaire as a tool for medical students to self-monitor their improvement during participation in the Scholarly Project. From the mentors’ perspective, the questionnaire provides a reliable and convenient reference for providing feedback to students and suggestions about areas that need further improvement. These approaches could also be utilised in other institutions, either locally or internationally, who include a Scholarly Project for a number of reasons: (1) the Scholarly Project is a lengthy module that could be impacted by unexpected events (e.g. COVID-19); (2) the need for routine self-check and mentor feedback to facilitate the required research skills improvement; and (3) because the questionnaire is a validated, convenient and accessible method for both medical students and mentors.

D. Study Limitations

Although the survey was sent to all medical students participating in the Scholarly Project, only just over half of students responded. Therefore, the impact of the Scholarly Project on non-responding medical students may not reflect the trends reported here, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Nonresponse bias is another potential limitation, although this is not necessarily associated with a lower response rate (Davern, 2013; Halbesleben and Whitman, 2012). Participants might perceive that self-evaluation about how much their research skills had improved could indirectly reflect their level of participation in Scholarly Project, the contribution of their mentor, and the level of their academic performance, leading to social desirability bias in their responses. We attempted to reduce nonresponse and social desirability bias, and any perception that responses could impact on academic assessments, by making survey responses anonymous and keeping the study survey completely separate from any academic assessments (e.g. grade-point average). Another limitation is the lack of a control group of medical students, but this is difficult because participation in the Scholarly Project is mandatory for all students. Using a control group would have strengthened the study from a methodological perspective and allowed investigation of the impact of specific aspects of the Scholarly Project.

Respond shift bias is inevitable while conducting this research. To reduce this, instead of completing self-evaluation for all fourteen skills initially and then after the completion of the whole project, students should assess their skill level immediately after the completion of each Module. However, response shift bias happened because respondents perceived the purpose of the survey as assessing the program’s effectiveness. In the context of our research, even if assessments were completed after each Module, students would realise the aim of the survey meaning that respond-shift bias would not decrease considerably.

V. CONCLUSION

Scholarly Project is an excellent learning opportunity for medical students in the refreshed undergraduate medical curriculum. Participating in a Scholarly Project provides students with research experience, including the knowledge, structure, and support needed to engage in scholarly work. By providing the foundations for scholarly work, medical students can enter the health care workforce with solid clinical expertise and the basic skills required to conduct high-quality projects that improve the safety and quality of care delivered to patients. We suggest integrating the Scholarly Project curriculum throughout the undergraduate medical education curriculum in Vietnam. This is important in terms of early experience of medical research and fostering a good understanding of medical scientific research for all future doctors, regardless of their ultimate career destination.

Notes on Contributors

N.T.M.D. and K.H.V. drafted and revised the manuscript. V.T.N.L. helped in reviewing the manuscript. All authors (N.T.M.D., K.H.V., V.T.N.L.) have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The authors declare that this study did not require human ethics approval and did not include experiments on animal or human subjects. This study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. This project was determined to be exempt from IRB review. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Respondents were informed that their participation in the survey was completely voluntary and there were no risks associated with their participation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available for reasons of data protection but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgement

The authors would very much like to acknowledge Ms. Le Minh Chau, Mr. Ung Nguyen Vu Hoang, Ms. Duong Kim Ngan, Mr. Nguyen Hai Dang, Ms. Tran Thi Hong Ngoc, Mr. Giang Luu Thanh Hoang, and Mr. Nguyen Hoang Nhan (University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) for their support of this study.

Funding

No funding has been received for the study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186-3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Bickford, N., Peterson, E., Jensen, P., & Thomas, D. (2020). Undergraduates interested in STEM research are better students than their peers. Education Sciences, 10(6), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10060150

Blockus, L., Kardash, C. M., Blair, M., & Wallace, M. (1997). Undergraduate internship program evaluation: A comprehensive approach at a research university. Council on Undergraduate Research, 18, 60–63.

Boninger, M., Troen, P., Green, E., Borkan, J., Lance-Jones, C., Humphrey, A., Gruppuso, P., Kant, P., McGee, J., Willochell, M., Schor, N., Kanter, S. L., & Levine, A. S. (2010). Implementation of a longitudinal mentored scholarly project: An approach at two medical schools. Academic Medicine, 85(3), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181ccc96f

Carraccio, C., Wolfsthal, S. D., Englander, R., Ferentz, K., & Martin, C. (2002). Shifting Paradigms. Academic Medicine, 77(5), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200205000-00003

Carson, S. (2007). A new paradigm for mentored undergraduate research in molecular microbiology. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 6(4), 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.07-05-0027

Dagher, M. M., Atieh, J. A., Soubra, M. K., Khoury, S. J., Tamim, H., & Kaafarani, B. R. (2016). Medical Research Volunteer Program (MRVP): Innovative program promoting undergraduate research in the medical field. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), Article 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0670-9

Davern, M. (2013). Nonresponse rates are a problematic indicator of nonresponse bias in survey research. Health Services Research, 48(3), 905–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12070

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251–19257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Duong, D. B., Phan, T., Trung, N. Q., Le, B. N., Do, H. M., Nguyen, H. M., Tang, S. H., Pham, V. A., Le, B. K., Le, L. C., Siddiqui, Z., Cosimi, L. A., & Pollack, T. (2021). Innovations in medical education in Vietnam. BMJ Innovations, 7(Suppl 1), s23–s29. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2021-000708

Fan, A. P., Tran, D. T., Kosik, R. O., Mandell, G. A., Hsu, H. S., & Chen, Y. S. (2012). Medical education in Vietnam. Medical Teacher, 34(2), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2011.613499

Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., Cate, O. T., Holmboe, E. S., Carraccio, C., Swing, S. R., Harris, P., Glasgow, N. J., Campbell, C., Dath, D., Harden, R. M., Iobst, W., Long, D. M., Mungroo, R., Richardson, D. L., Sherbino, J., Silver, I., Taber, S., Talbot, M., & Harris, K. A. (2010). Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 638–645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.501190

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Whitman, M. V. (2012). Evaluating survey quality in health services research: A decision framework for assessing nonresponse bias. Health Services Research, 48(3), 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12002

Hoat, L. N., Lan Viet, N., van der Wilt, G., Broerse, J., Ruitenberg, E., & Wright, E. (2009). Motivation of university and non-university stakeholders to change medical education in Vietnam. BMC Medical Education, 9(1), Article 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-49

Holloway, R., Nesbit, K., Bordley, D., & Noyes, K. (2004). Teaching and evaluating first and second year medical students’ practice of evidence-based medicine. Medical Education, 38(8), 868–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01817.x

Iobst, W. F., Sherbino, J., Cate, O. T., Richardson, D. L., Dath, D., Swing, S. R., Harris, P., Mungroo, R., Holmboe, E. S., & Frank, J. R. (2010). Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.500709

Kardash, C. M. (2000). Evaluation of undergraduate research experience: Perceptions of undergraduate interns and their faculty mentors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.191

Kinser, P. A., & Robins, J. L. (2013). Control group design: enhancing rigor in research of mind-body therapies for depression. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/140467

Leppink, J. (2017). Helping medical students in their study of statistics: A flexible approach. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.08.007

Manduca, C. (1997). Broadly defined goals for undergraduate research projects: A basis for program evaluation. Council on Undergraduate Research, 18(2), 64–69.

Murdoch-Eaton, D., Drewery, S., Elton, S., Emmerson, C., Marshall, M., Smith, J. A., Stark, P., & Whittle, S. (2010). What do medical students understand by research and research skills? Identifying research opportunities within undergraduate projects. Medical Teacher, 32(3), e152–e160. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421591003657493

Nguyen, T. V., Ho-Le, T. P., & Le, U. V. (2016). International collaboration in scientific research in Vietnam: An analysis of patterns and impact. Scientometrics, 110(2), 1035–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2201-1

Pithon, M. M. (2013). Importance of the control group in scientific research. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics, 18(6), 13–14. https://doi.org/10.1590/s2176-94512013000600003

Schor, N. F., Troen, P., Kanter, S. L., & Levine, A. S. (2005). The scholarly project initiative: Introducing scholarship in medicine through a longitudinal, mentored curricular program. Academic Medicine, 80(9), 824–831. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200509000-00009

Schwartzstein, R. M., Dienstag, J. L., King, R. W., Chang, B. S., Flanagan, J. G., Besche, H. C., Hoenig, M. P., Miloslavsky, E. M., Atkins, K. M., Puig, A., Cockrill, B. A., Wittels, K. A., Dalrymple, J. L., Gooding, H., Hirsh, D. A., Alexander, E. K., Fazio, S. B., & Hundert, E. M. (2020). The Harvard Medical School pathways curriculum: Reimagining developmentally appropriate medical education for contemporary learners. Academic Medicine, 95(11), 1687–1695. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003270

Schwartzstein, R. M., & Roberts, D. H. (2017). Saying goodbye to lectures in medical school — Paradigm shift or passing fad? New England Journal of Medicine, 377(7), 605–607. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1706474

Zydney, A. L., Bennett, J. S., Shahid, A., & Bauer, K. W. (2002). Impact of undergraduate research experience in engineering. Journal of Engineering Education, 91(2), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2002.tb00687.x

*Nguyen Tran Minh Duc

217 Hong Bang Street, Ward 11,

District 5, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

+84 988 127 948

Email: ntmduc160046@ump.edu.vn

Submitted: 13 January 2022

Accepted: 9 May 2022

Published online: 4 October, TAPS 2022, 7(4), 35-49

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-4/OA2699

Yuan Kit Christopher Chua1*, Kay Wei Ping Ng1*, Eng Soo Yap2,3, Pei Shi Priscillia Lye4, Joy Vijayan1, & Yee Cheun Chan1

1Department of Medicine, Division of Neurology, National University Hospital Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Haematology-oncology, National University Cancer Institute Singapore, Singapore; 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, National University Hospital Singapore, Singapore; 4Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, National University Hospital Singapore, Singapore

*Co-first authors

Abstract

Introduction: In-class engagement enhances learning and can be measured using observational tools. As the COVID-19 pandemic shifted teaching online, we modified a tool to measure the engagement of instructors and students, comparing in-person with online teaching and different class types.

Methods: Video recordings of in-person and online teachings of six identical topics each were evaluated using our ‘In-class Engagement Measure’ (IEM). There were three topics each of case-based learning (CBL) and lecture-based instruction (LLC). Student IEM scores were: (1) no response, (2) answers when directly questioned, (3) answers spontaneously, (4) questions spontaneously, (5) initiates group discussions. Instructor IEM scores were: (1) addressing passive listeners, (2) asking ≥1 students, (3) initiates discussions, (4) monitors small group discussion, (5) monitoring whole class discussions.

Results: Twelve video recorded sessions were analysed. For instructors, there were no significant differences in percentage time of no engagement or IEM scores when comparing in-person with online teaching. For students, there was a significantly higher percentage time of no engagement for the online teaching of two topics. For class type, there was overall less percentage time of no engagement and higher IEM scores for CBL than LLC.

Conclusion: Our modified IEM tool demonstrated that instructors’ engagement remained similar, but students’ engagement reduced with online teaching. Additionally, more in-class engagement was observed in CBL. “Presenteeism”, where learners were online but disengaged was common. More effort is needed to engage students during online teaching.

Keywords: Engagement, Observational Tool, Online Learning, E-learning, COVID-19, Medical Education, Research

Practice Highlights

- Lectures to large class (LLC) and case-based learning (CBL) are associated with lower levels of student engagement when conducted on a virtual platform.

- Instructors’ engagement during online teachings remained similar to that of in-person teachings.

- LLC is associated with reduced student engagement than CBL.

I. INTRODUCTION

Educational theories suggest that learning should be an active process. According to social constructivist theory, learning can be better achieved by social interactions in the learning environment (Kaufman, 2003). Active learning strategies fostering the students to interact with each other and the instructor such as discussions, talks, questions, may yield desirable learning outcomes in terms of knowledge, skills, or attitudes (Rao & DiCarlo, 2001). Therefore, using in-class learner engagement as an important keystone of active learning strategies is known to stimulate and enhance the learner’s assimilation of content and concepts (Armstrong & Fukami, 2009; Watson et al., 1991).

There is good evidence for the importance of engagement in online learning and use of an engagement metric has been advocated to better understand student online interactions to improve the online learning environment (Berman & Artino, 2018). While medical literature suggests that virtual education games foster engagement (McCoy et al., 2016), the level of engagement and learning fostered by online methods for group discussion and teaching is unknown. Teleconferencing is among some of the methods suggested for maintaining education during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chick et al., 2020).

Possible methods of quantifying student engagement include direct observation and student self-report. O’Malley et al. (2003) has published a validated observation instrument called STROBE to assess in-class learner engagement in health professions without interfering with learner activities. This observation instrument is used to document observed dichotomized types of instructor and student behaviors in 5-minute cycles and quantify the number of questions asked by the instructor and students in different class subtypes. This instrument as well as revised forms of this instrument has since been used as “in-class engagement measures” to compare instructor and student behaviors in different class types (Alimoglu et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2005).

In our institution, a hybrid curriculum of case-based learning as well as lecture-style courses is used to teach the post graduate year one (PGY-1) interns. We had video recordings of these courses performed in-person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. With the advent of the pandemic, these courses were shifted onto Zoom teleconferencing platform, but delivered by the same instructors, in the same class format.

We therefore aimed to determine and compare in-class learning engagement levels via observing instructor and student behaviours in different platforms of learning (either observed online or in-person retrospectively via video recording) delivered by the same instructor before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also aimed to compare instructor and student behaviours in different class types (either case-based learning or lecture style instruction). To do this, we planned to modify a known in-person observational tool for student engagement – “STROBE” (O’Malley et al., 2003) for use in analysing and recording the behaviours of students in both online and in-person teaching.

II. METHODS

A. Observed Class Types

In this study, we observed two different class types, case-based learning (CBL), as well as lecture-based instruction to teach basic medical/surgical topics to a large classroom (LLC) of PGY-1 interns. Video recordings of these in-person teachings were made in 2017. Both these class types were replicated in the same format on an online Zoom teleconferencing platform and were delivered by nearly all of the same tutors using the same content and Powerpoint slides during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. We aimed to view the 2017 video-recordings of the in-person teachings and compare them with the 2020 online teaching of PGY-1 interns. Written consent was obtained from the tutors and implied consent from the students. Students were informed beforehand via email that the sessions were going to be observed and they were again reminded at the start of each session where they had the chance to opt out. Subsequently, all student feedback and observation scores were amalgamated and de-identified. This study was approved by the institution’s ethics board.

Three topics each of case-based learning as well as lecture-style instruction were selected in chronological order as scheduled for students. Each topic of instruction was allotted up to a maximum of 90 minutes of time, but the instructor could choose to end the class earlier if the session was completed. Description of both class types are below.

1) Description of case-based learning in large classroom

The content of the learning was designed by the instructor, and consisted of clinical cases involving patient scenarios, where the main pedagogy was problem-solving and answering case-based questions relating to the patient scenario (e.g., diagnosis, reading clinical images or electrocardiograms, creating an investigation or treatment plan). Each case would typically take about 15 to 20 minutes to complete, and there would typically be five to six cases. Students were expected to answer the questions, and the instructor gave feedback on the answers and provided additional information, sometimes via additional Powerpoint slides. Class discussions were encouraged where students were encouraged to debate and discuss with each other over their classmates’ answers. The titles of the case-based learning were “ECG – tachydysrhythmias”, “Approach to a confused patient” and “Approach to chest pain”.

2) Description of lecture in large classroom

This is a typical lecture-style instruction performed with participation of around 86 PGY1-interns and one instructor. The instructor delivers information via a Powerpoint slide presentation and rarely adds clinical case-based questions into the slides to invite student discussion. The titles of the lectures were “Cardiovascular health – hypertensive urgencies”, “Trauma – chest, abdomen and pelvis” and “Stroke”.

B. Instructor and Student Characteristics

The instructors all had at least ten years of teaching experience in medical education, and all had been teaching the same topics to the PGY-1 interns for at least the last five years. Student feedback scores on their teaching activities have been satisfactorily high (mean 4.63 for 2019, the year prior to the shift to online learning for the pandemic). All the tutors (except for one instructor who taught “Stroke”) had taught the same topics using the same content and Powerpoint slides in 2017 via in-person teaching which was caught on camera.

The students were all PGY-1 interns, who have been asked by the institution to attend at least 70% of a mandatory one-year long teaching program where they are given weekly instruction on various medical or surgical topics. The teaching program commences from May of each year. There were 86 PGY-1 interns commencing their rotations in our institution and attending the teaching program from May 2020. There were 75 PGY-1 interns attending the teaching program in the video recordings caught in 2017.

C. Observation Tool

A revised form of STROBE (O’Malley et al., 2003) was used to analyze and record the behaviors of the instructor and students in classes, to provide a more objective third-person measure of student engagement. The original STROBE tool was an instrument that was developed to objectively measure student engagement across a variety medical education classroom settings. The STROBE instrument consists of 5-minute observational cycles repeated continuously throughout the learning session with relevant observations recorded on a data collection form. Within each cycle, observers record selected aspects of behavior from a list of specified categories that occur in each interval recorded. Observations include macrolevel elements such as structure of class, major activity during time, and a global judgment of the proportion of class members who appear on task, as well as microlevel elements such as instructor’s behavior and the behaviors of four randomly selected students. Observers also record who the behaviours of instructors and students were directed at. After which, observers tally the number of questions asked by the students and instructor in the remainder of the 5 minutes. The revision of this tool was made by the 3 Clinician-educators from the research team (CYC, YES, KN), having discussed what kind of instructor and student behaviors were considered as “active student engagement”, keeping the main statements and principles of the original STROBE tool. The scale was modified to make it suitable for use in an online learning setting, where the observers may not be able to observe the student’s body language cues when the student does not turn on his/her video function. We called this modified scale our ‘In-class engagement measure’. The modified scales were as follows:

A 5-item list of instructor and student behaviors was therefore created and rated from 1 to 5 each, with different scales for instructor and student. For the student behavior scale, each item was to show progressively increasing levels of interaction, and perceived engagement, both with the instructor and with each other. For the instructor behavior list, each item was also about progressively interactive behaviors by the instructor to get the students to engage. We called these scales our “In-class Engagement Measure (IEM)”. The scales were as follows:

Student:

- No response even when asked

- Answers only when directly questioned

- Answers questions spontaneously

- Speaks to instructor spontaneouslyg.,Poses questions, discusses concepts

- Speaks to instructor and 1 or more other student during a discussion

Instructor:

- Talking to entire class while all the students are passive receivers

- Telling/asking to one or a group of students, or teaching/showing an application on a student

- Starting or conducting a discussion open to whole class, or assigning some students for some learning tasks

- Listening/monitoring actively discussing one or a group of students

- Listening/monitoring actively discussing entire class

For the student behaviour list, we also sub-categorized the student behaviour item “1”, where “1*” was defined as no response when a question was posed to a specific student and not just the whole class, where the student-in-question would have his/her name called by the tutor.

D. Observation Process

Drawing from the described process for the STROBE observation tool (O’Malley et al., 2003), as well as other described modifications of the STROBE tool (Alimoglu et al., 2014), we used the same observation units and cycles. Modifications to the original described process for the STROBE observation tool was made to make it suitable for not being in-person when observing a large group of students and their instructor. Three observers from the research team (CYC, YES, KN) observed and recorded the instructor and student behaviors for the three case-based learning and three lecture-style learning conducted live online in 2020, and as a video recording of in-person teaching in 2017. A total of 12 lectures were therefore analyzed. One observation unit was a 5-minute cycle. The 5-minute cycle would proceed as such: The observer would write the starting time of the cycle and information about the class (number of students, title of session). The observer would select a student from the class and observe that student for 20 seconds and mark the type of engagement observed according to the IEM scale created. As the observers were not in-person for the teaching at either the 2017 video recording, and for the 2020 online learning, students who responded to the instructor or posed questions were marked at the same time by all the three observers. The 5-minute cycle would consist of four 20-second observations of individual learners, so marking of student engagement would be performed four times within that cycle with different students in succession. The observer would also observe the instructor for that 5-minute cycle and similarly mark the instructor’s behavior once for that 5-minute cycle. For the remainder of the modified STROBE cycle, the observer would tally the number of questions asked by all the students and the instructor.

Observers independently and separately observed and marked the students’ and instructors’ behaviors. Due to the lack of in-person observation, students who responded or posed questions during the session were uniformly chosen for marking by the three observers. If a student had already been marked once during that cycle, the same student was not used for remaining three observations within the same cycle. At the end of the marking, two observers (KN and YES) compared their scores for both students and instructor. The marks given by the third observer (CYC) was used to validate the final score awarded and used as the tiebreaker when there was a discrepancy in the marks given by the first two observers.

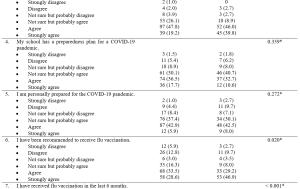

E. Collation of Post Teaching Survey Feedback

Apart from the data derived from our modified observational tool, we also reviewed data from surveys conducted by the educational committee after each of these teaching sessions (see Table 1). These were general surveys used to solicit student feedback on the teaching sessions. They were distributed in-person in 2017, with the same forms distributed to the students online in 2020. Responses from the students were in response to five statements, with scoring 0 to 5 (1 for Strongly disagree, 2 for disagree, 3 for neither agree nor disagree, 4 for agree, and 5 for Strongly agree). These feedback forms had an overall feedback score marked by the student, as well as a score marked by the student in response to a question assessing for self-reported engagement – “The session was interactive and engaging”. The other questions were “The session has encouraged self-directed learning and critical thinking”, “The session was relevant to my stage of training”, “The session helped me advance my clinical decision-making skills”, and “The session has increased my confidence in day-to-day patient management”. Means of the feedback scores were taken as a qualitative guide, and we analyzed the overall feedback scores (“Overall feedback score” in Table 1), and the scores in response to the question assessing for self-reported engagement (“Self-reported engagement feedback score” in Table 1).

F. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to determine frequencies and median number of questions asked, as well as mean student feedback scores and absolute duration of each teaching session. Fisher exact test was also performed to analyze the differences in scores between different lectures and case-based learning, and the scores in the 2017 in-person learning versus that of the 2020 online learning. For analysis of the scores, we dichotomized our scores using the cut-off of “1”, or our first item on the behavior list for both students and instructors, as we felt that the first item reflected an extreme non-participation for both student and instructor, which if left to continue, can result in negative learning and teaching behaviors.

III. RESULTS

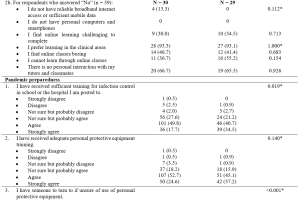

A. Class Types, Characteristics, Feedback Scores

A total of 12 sessions were observed, consisting of in-person and online teaching sessions of six topics (Table 1). There were 3 topics of CBL and LLC each. Duration of the class sessions range from 30-55 minutes for the in-person sessions and 40-90 minutes for the online sessions. Total number of PGY-1 students eligible to attend the in-person teaching sessions in 2017 was 82, and 86 for the online teaching sessions in 2020. Student attendance for the in-person sessions ranged from 11 (13.4%) to 31 (37.8%) and that for the online session ranged from 28 (32.6%) to 77 (89.5%). Median (range) of feedback scores for in-person sessions were 4.57 (4.25 to 4.72) vs 4.32 (4.04 to 4.61) for online sessions. Median (range) of self-reported engagement scores for in-person sessions were 4.55 (4.25 to 4.79) vs 4.34 (4.00 to 4.67) for online sessions (Table 1).

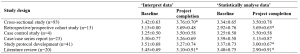

Table 1. Class types and characteristics (*Different tutors, but using same content)

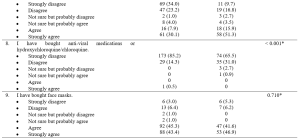

B. Instructors’Engagement Behaviour

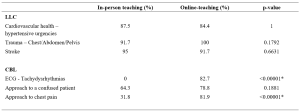

1) Comparing in-person vs online teaching: Percentage time during which there is no engagement/interaction (or scoring “1” on the IEM score). This ranges from 0-80% for in-person teaching vs 0-100% for online teaching (Table 2A). For each topic, there is no significant difference between percentage time of no engagement.

Most frequent IEM scores. Most frequent IEM scores for each 5-minute segment were 3 for in-person teaching (48.9%) and online teaching (52.9%) (Table 2B).

2) Comparing CBL vs LLC: Percentage time during which there is no engagement/interaction. This ranges from 0-23.1% for CBL vs 50-100% for LLC (Table 2A).

Most frequent IEM scores. Most frequent IEM score was 3 for CBL (77.3%) and 1 for LLC (71.4%). (Table 2B).

Table 2A. Comparison of instructors’ behaviour showing percentage time with no engagement (scoring “1” on the IEM score)

Table 2B. Numbers (percentages) of a particular IEM score received for a 5-minutes segment of teaching – for instructors

C. Students’ Engagement Behaviour

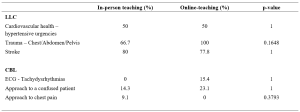

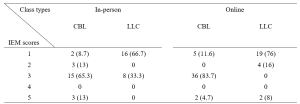

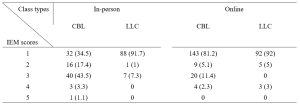

1) Comparing in-person vs online teaching: Percentage time during which there is no engagement/interaction. This ranges from 0-95% for in-person teaching vs 78.8-100% for online teaching (Table 3A). There is significant difference in percentage time of no engagement in two topics (ECG, chest pain), where there is higher percentage of no engagement time with online teaching.

Most frequent IEM scores. Most frequent IEM scores were 1 for both in-person teaching (63.8%) and online teaching (85.1%) (Table 3B).

2) Comparing CBL vs LLC: Percentage time during which there is no engagement/interaction. This ranges from 0-81.9% for CBL vs 84.4-100% for LLC (Table 3A).

Most frequent IEM scores.

Most frequent IEM scores were 1 for both CBL (65.3%) and LLC (91.8%) (Table 3B).

Presence of 1* scores, where “1*” was defined as no response when a question was posed to a specific student called by name. There was no 1* IEM score for in-person teaching for either CBL or LLC, and 8.4% (12/143) of the “1” responses were 1* for online-teaching for CBL and 6.5% (6/92) of the “1” responses were 1* for LLC.

Table 3A. Comparison of students’ behaviour showing percentage time with no engagement (scoring “1” on the IEM score)

Table 3B. Numbers (percentages) of a particular IEM score received for a 5-minutes segment of teaching – for students

D. Number of Questions Asked Per 5-minute Cycle

Median number of questions asked by instructors ranged from 0-2 for in-person teaching and 1-3 for online teaching (See Appendix 1). These range from 1-3 for CBL vs 0-1 for LLC.

Median number of questions asked by students in all sessions were 0.

The results for this study can be derived from the dataset uploaded onto the online repository accessed via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.18133379.v1 (Chua et al., 2022).

IV. DISCUSSION

We modified the known STROBE instrument (O’Malley et al., 2003) to create an observational tool “IEM” which could be used to quantify instructor and student engagement despite the observer not being present in-person. Our IEM scores were derived by taking scores that were in agreement when independently scored by two main observers (YES and KN). The third observer (CYC) was used as the validator of the scores by the two main observers. When there was a discrepancy in the scores awarded by the two observers, the score which was in agreement with the score awarded by CYC was used. To give an indication of the IEM tool’s effectiveness where the observer is not present in-person, we postulated that our modified IEM score should still demonstrate the well-documented difference in engagement between lecture-style learning and case-based learning sessions (Kelly et al., 2005). Our modified IEM score did indeed show more frequent higher scores as expected for case-based learning sessions (Tables 2B and 3B). We also compared our IEM scores with the students’ self-reported engagement scores (Table 1) that had been collected as part of student feedback. The general correlation in the trend of observed IEM scores with that of the students’ self-reported engagement scores also suggest the usefulness of our modified STROBE tool in situations where the observer is not present in-person, although this needs to be further validated in prospective studies.

Our initial study hypothesis was that students may find themselves more engaged in online teaching sessions and open to posing questions to the instructor and their peers, due to the presence of the “chat”, “likes” and “poll” functions available on the Zoom tele-conferencing platform, which may be more familiar to a younger generation accustomed to using social media. We had postulated that live online lectures would encourage further engagement from students who would not otherwise participate in-person, due to the less intimidating online environment where they can ask and answer questions more anonymously (Kay & Pasarica, 2019; Ni, 2013). In an Asian-pacific context, video conferencing had been found to be able to improve access for participation for more reticent participants who prefer written expression, through alternative communication channels like the ‘chat box’, although there was a potential trend to reduced engagement. (Ong et al., 2021).

Our data, shows, that Zoom teleconferencing during the COVID-19 pandemic can be associated with reduced student engagement. The percentage time where there was no engagement was significantly higher with online sessions (Table 3A) and the most frequent IEM score was lower (1 for online vs 3 for in-person), for CBL sessions (Table 3B). This phenomenon in medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic has previously been described. Using student and instructor feedback, students were more likely to have reduced engagement during virtual learning (Longhurst et al., 2020; Dost et al., 2020), and would have increased difficulties maintain focus, concentration and motivation during online learning (Wilcha, 2020).

Our data also suggests that for the instructor to even try to achieve close to the same levels of engagement as before, a longer duration of time was spent by each instructor per topic when executing CBL (Table 1). This may include time where the instructor needs multiple attempts at questioning and discussion before there is a student response. It is also possible that for in-person learning, the instructor relies greatly also on non-verbal cues (e.g., body language, nods of the head, collective feel of the room) to determine if a question has been satisfactorily answered, and therefore can move on quicker than when on a Zoom platform where one cannot see most, or even every student.

The higher number of attendees for online learning compared to in-person attendance (see Table 1) highlights one of the strengths of online learning, which is where online learning is more easily accessible for students who would save on time getting to a designated lecture room and provides flexibility for students to enter and exit (Dost et al., 2020). Unfortunately, this also likely encourages the phenomenon of “presenteeism”, where students are not focused on the learning session, but instead engage in other tasks simultaneously, e.g., reading or composing emails, or completing work tasks instead of having dedicated protected teaching time. Resident learners have been described to participate in nearly twice as many non-teaching session related activities per hour during an online session than when in-person (Weber & Ahn, 2020). This has likely contributed to the number of 1* scores we had, where the student has logged into the Zoom platform, but is not available to even respond in the negative when called upon to answer a question. This presenteeism, however, is not just a problem for online learning, but even for in-person learning, where pretending to engage has been found to be a significant unrecognized issue (Fuller et al., 2018).

The main implication that our study highlights that to improve student engagement when using online learning, a face-to-face platform cannot simply be transposed into a virtual platform. It had been suggested that engagement during live virtual learning could be enhanced with the use of interactive quizzes with audience polling functions (Morawo et al., 2020) and possibly other methods such as “gamification” (Nieto-Escamez & Roldan-Tapia, 2021). Our instructors for the CBL sessions had used both poll functions and live questioning for their sessions, but without increased success in engagement. Smaller groups are likely required to enhance student engagement, but this would lead to the need for increased time and teaching manpower. Increasing the opportunity for interaction via a virtual platform would also require the need to create additional online resources, which would take up more faculty time where creating new resources can take at least three times as much work compared to a traditional format (Gewin, 2020). Online resources would need to be modified in such a way that increases student autonomy to increase student engagement in medical education (Kay & Pasarica, 2019). Our study also shows that as a first step, in time and resource-limited settings, a case-based approach to teaching would be more ideal to enhance student engagement than lecture style teaching.

A culture of accountability also needs to be fostered within the online teaching sessions, where students need to be educated on how Zoom meetings can be more enriching when cameras are on (Sharp et al., 2021). PGY-1 interns, as recent graduates, also need to be educated on the aspect of professionalism when entering the medical work force, where they can be called upon to answer questions during meetings or conferences. When initial questions are not voluntarily answered, our tutors often practice “cold-calling”, which can help keep learners alert and ready (Lemov, 2015). Unfortunately, these evidence-based teaching methods that work well when the student is in-person, ultimately will fail if online students are not educated on their need to be accountable to the instructor or their peers.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the level of student engagement may also be affected by external factors, such as a different physical learning environment, class size and avenues of communication. The stresses of the on-going pandemic may also have affected student engagement, as a decrease in quality of life and stress would negatively impact student motivation (Lyndon et al., 2017). Secondly, the topics for lecture to large class and case-based learning were not identical as these topics were picked in chronological order and there were no topics in the curriculum that had material for both the lecture and case-based learning class types. This difference in topics may have potentially contributed to confounding when we try to make direct comparisons between the two class types, although, we have attempted to mitigate this by including a variety of topics in each class type. Thirdly, the improved student engagement and feedback scores for in-person learning may also have had some bias given the smaller student size for in-person learning. It is also possible that only the more motivated, and hence more likely to be engaged students, would turn up for in-person learning. Fourthly, due to the online nature as well as the retrospective viewing of the video recordings, the observers were not present in-person to observe the non-verbal cues of the students or instructors. The tool, however, was modified to take into account only the verbal output that could be observed online or via video recording. Lastly, our IEM tool will benefit from more studies and research to further confirm its validity in observing students when the observer is not present in-person.

V. CONCLUSION

Lectures are associated with reduced student engagement than case-based learning, while both class types are associated with lower levels of student engagement when conducted on a virtual platform. Instructor levels of engagement, however, remain about the same. This highlights that a face-to-face platform cannot simply be transposed into a virtual platform, and it is important to address this gap in engagement as this can lower faculty satisfaction with teaching and ultimately result in burnout. Blended teaching or smaller group teaching as the world turns the corner in the COVID-19 pandemic may be one way to circumvent the situation but is also constrained by faculty time and manpower. Our study also shows that as a first step, in time and resource-limited settings, a case-based approach to teaching would be more ideal to enhance student engagement than lecture style teaching.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Ng Wei Ping Kay and Dr Chua Yuan Kit Christopher are co-first authors and contributed to conceptual development, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. They contributed to drafting and revising the work and approved the final version to be published. They agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Lye Pei Shi Priscillia contributed to conceptual development, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. She contributed to drafting and revising the work and approved the final version to be published. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Joy Vijayan contributed to conceptual development, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. He contributed to drafting and revising the work and approved the final version to be published. He agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Yap Eng Soo contributed to conceptual development, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. He contributed to drafting and revising the work and approved the final version to be published. He agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Chan Yee Cheun contributed to conceptual development, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. He contributed to drafting and revising the work and approved the final version to be published. He agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

I confirm that the study has been approved by Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB), National Healthcare Group, Singapore, an institutional ethics committee. DSRB reference number: 2020/00415.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.fig share.18133379.v1.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Jacqueline Lam for her administrative support in observing the recordings and online-teaching.

Funding

There was no funding for this research study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Alimoglu, M. K., Sarac, D. B., Alparslan, D., Karakas, A. A., & Altintas. (2014). An observation tool for instructor and student behaviors to measure in-class learner engagement: A validation study. Medical Education Online, 19(1), 24037. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v19.24037

Armstrong, S. J., & Fukami, C. V. (2009). The SAGE Handbook of Management Learning, Education and Development. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://www.doi.org/10.4135/9780857021038

Berman, N. B., & Artino, A. R. J., (2018). Development and initial validation of an online engagement metric using virtual patients. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1322-z

Chick, R. C., Clifton, G. T., Peace, K. M., Propper, B. W., Hale, D. F., Alseidi, A. A., & Vreeland, T. J. (2020). Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(4), 729–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Chua, Y. K. C., Ng, K. W. P., Yap, E. S., Lye, P. S. P., Vijayan, J., & Chan, Y. C. (2022). Evaluating online learning engagement (Version 1) [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.18133379.v1

Dost, S., Hossain, A., Shehab, M., Abdelwahed, A., & Al-Nusair, L. (2020). Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open, 10(11), e42378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378

Fuller, K. A., Karunaratne, N. S., Naidu, S., Exintaris, B., Short, J. L., Wolcott, M. D., Singleton, S., & White, P. J. (2018). Development of a self-report instrument for measuring in-class student engagement reveals that pretending to engage is a significant unrecognized problem. PLOS ONE, 13(10), e0205828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205828

Gewin, V. (2020). Five tips for moving teaching online as COVID-19 takes hold. Nature, 580(7802), 295–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00896-7

Kaufman, D. M. (2003). Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ, 326(7382), 213–216. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7382.213

Kay, D., & Pasarica, M. (2019). Using technology to increase student (and faculty satisfaction with) engagement in medical education. Advances in Physiology Education, 43(3), 408–413. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00033.2019

Kelly, P. A., Haidet, P., Schneider, V., Searle, N., Seidel, C. L., & Richards, B. F. (2005). A comparison of in-class learner engagement across lecture, problem-based learning, and team learning using the STROBE classroom observation tool. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 17(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1702_4

Lemov, D. (2015). Teach like a champion 2.0: 62 techniques that put students on the path to college. (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Longhurst, G. J., Stone, D. M., Dulohery, K., Scully, D., Campbell, T., & Smith, C. F. (2020). Strength, weakness, opportunity, threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1967

Lyndon, M. P., Henning, M. A., Alyami, H., Krishna, S., Zeng, I., Yu, T.-C., & Hill, A. G. (2017). Burnout, quality of life, motivation, and academic achievement among medical students: A person-oriented approach. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6(2), 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-017-0340-6

McCoy, L., Pettit, R. K., Lewis, J. H., Allgood, J. A., Bay, C., & Schwartz, F. N. (2016). Evaluating medical student engagement during virtual patient simulations: A sequential, mixed methods study. BMC Medical Education, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0530-7

Morawo, A., Sun, C., & Lowden, M. (2020). Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Medical Education, 54(12), 1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

Ni, A. Y. (2013). Comparing the effectiveness of classroom and online learning: Teaching research methods. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19(2), 199-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2013.12001730

Nieto-Escamez, F. A., & Roldan-Tapia, M. D. (2021). Gamifica- tion as online teaching strategy during COVID-19: A mini-review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648552

O’Malley, K. J., Moran, B. J., Haidet, P., Seidel, C. L., Schneider, V., Morgan, R. O., Kelly, P. A., & Richards, B. (2003). Validation of an observation instrument for measuring student engagement in health professions settings. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 26(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278702250093

Ong, C. C. P., Choo, C. S. C., Tan, N. C. K., & Ong, L. Y. (2021). Unanticipated learning effects in videoconference continuous professional development. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 6(4), 135-141. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/SC2484

Rao, S. P., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2001). Active learning of respiratory physiology improves performance on respiratory physiology examinations. Advances in Physiology Education, 25(2), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1152/advances.2001.25.2.55

Sharp, E. A., Norman, M. K., Spagnoletti, C. L., & Miller, B. G. (2021). Optimizing synchronous online teaching sessions: A guide to the “new normal” in medical education. Academic Pediatrics, 21(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.009

Watson, W. E., Michaelsen, L. K., & Sharp, W. (1991). Member competence, group interaction, and group decision making: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(6), 803–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.6.803

Weber, W., & Ahn, J. (2020). COVID-19 conferences: Resident perceptions of online synchronous learning environments. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 22(1), 115–118. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.11.49125

Wilcha, R. J. (2020). Effectiveness of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 crisis: Systematic review. JMIR Medical Education, 6(2), e20963. https://doi.org/10.2196/20963

*Chua Yuan Kit Christopher

5 Lower Kent Ridge Road,

National University Hospital,

Singapore 119074

+65 7795555

Email: christopher_chua@nuhs.edu.sg

Submitted: 6 January 2022

Accepted: 4 May 2022

Published online: 4 October, TAPS 2022, 7(4), 22-34

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-4/OA2735

Amelah Abdul Qader1,2, Hui Meng Er3 & Chew Fei Sow3

1School of Postgraduate Studies, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2University of Cyberjaya, Faculty of Medicine, Cyberjaya, Malaysia; 3IMU Centre for Education, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: The direct ophthalmoscope is a standard tool for fundus examination but is underutilised in practice due to technical difficulties. Although the smartphone ophthalmoscope has been demonstrated to improve fundus abnormality detection, there are limited studies assessing its utility as a teaching tool for fundus examination in Southeast Asian medical schools. This study explored the perception of medical students’ toward using a smartphone ophthalmoscope for fundus examination and compared their abilities to diagnose common fundal abnormalities using smartphone ophthalmoscope against direct ophthalmoscope.

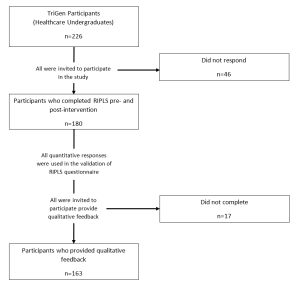

Methods: Sixty-nine Year-4 undergraduate medical students participated in the study. Their competencies in using direct ophthalmoscope and smartphone ophthalmoscope for fundus examination on manikins with ocular abnormalities were formatively assessed. The scores were analysed using the SPSS statistical software. Their perceptions on the use of smartphone ophthalmoscopes for fundus examination were obtained using a questionnaire.

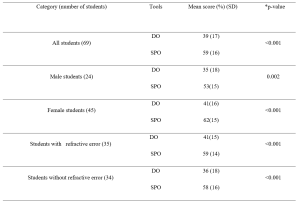

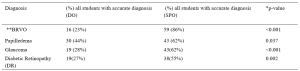

Results: The students’ competency assessment scores using the smartphone ophthalmoscope were significantly higher than those using the direct ophthalmoscope. A significantly higher percentage of them correctly diagnosed fundus abnormalities using the smartphone ophthalmoscope. They were confident in detecting fundus abnormalities using the smartphone ophthalmoscope and appreciated the comfortable working distance, ease of use and collaborative learning. More than 90% of them were of the view that smartphone ophthalmoscopes should be included in the undergraduate medical curriculum.