How do factors in fixed clinical teams affect informal learning among Emergency Medicine Residents

Submitted: 28 July 2022

Accepted: 12 October 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 25-32

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/OA2850

Choon Peng Jeremy Wee1, Mingwei Ng1 & Pim W. Teunissen2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 2School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Faculty of Health Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Abstract

Introduction: This study was performed to understand how fixed clinical teams affected informal learning in Emergency Medicine Residents. Better understanding the effects of team dynamics on informal learning may help to optimise learning and improve performance.

Methods: From 8th February 2020 till 27th September 2020, the Singapore General Hospital Emergency Department adopted a fixed team system. Zoom interviews were carried out amongst Emergency Medicine Residents who worked in the fixed team system using a semi-structured iterative interview guide. A qualitative content analysis was used for this exploratory study. The interviews were transcribed verbatim, anonymised and coding via template analysis performed. Data collection and analysis were performed until data sufficiency.

Results: The themes identified centred around relationship dynamics, team composition and motivation for learning. The first was how improved relationships led to improved trust, communications and camaraderie among team members. This improved peer learning and clinical supervision and provided a more personalised learning experience. A balanced team composition allowed learners to be exposed to experts in various subspecialties. Finally, there was an initial increase in motivation, followed by a decrease with time.

Conclusion: In postgraduate medical education, working in a fixed team system with balanced members had positive effects on informal learning by strengthening relationships and communications.

Keywords: Informal Learning, Workplace Learning, Fixed Teams, Medical Education, Postgraduate

Practice Highlights

- Fixed teams can strengthen relationships between members through better trust, familiarity and communication.

- A balanced fixed team with members having different areas of expertise allows a variety of perspectives.

- Rotation of team members may achieve a balance between the stronger relationship and familiarity of the members of fixed teams and the greater variance in perspectives from a non-fixed team system.

I. INTRODUCTION

Fixed teams (FT) and non-fixed teams (NFT) exist in medicine because of differing service requirements and manpower resources. Examples of FTs can exist in ward round teams and operating surgical teams (Eddy et al., 2016; Stepaniak et al., 2012) where personnel stay within the same work team for long periods. In other areas of healthcare like the Emergency Departments (ED), a NFT system is usually employed where teams are formed according to the personnel rostered to work on that shift and team members change every shift. This allows a more flexible system for the team members as they can request off days and leave according to their personal schedule and yet allows for 24-hour coverage in the ED.

High levels of performance are required of medical teams, both fixed and non-fixed, to achieve good patient outcomes. Therefore, team members should learn how to work effectively together to deliver the best patient care. There are studies, both within healthcare and other industries, which showed mixed results when FT were compared with NFT with regards to team performance. A systematic review on minimal invasive surgical teams found that the FTs had better teamwork and had reduced rates of technical mistakes compared to NFTs (Gjeraa et al., 2016). However, an aviation study showed that FTs made more minor errors compared to NFTs due to FT members being too familiar with each other and overlooking errors (Barker et al., 1996). Although it is unclear how transferable specific research findings from non-healthcare domains are, what is clear is that FTs and NFTs are different in the way teams were formed and the amount of time team members spend working together. There is a lack of understanding if and how these differences affect the way learning takes place in FT and NFTs; which could translate to the performance of the team and its members.

Workplace learning occurs through informal learning by experiencing work challenges and via interpersonal relationships. Informal learning can be supported through learner engagement by encouraging active participation in work activities and aligning learners’ interests with that of the organisation’s objectives towards improving the individuals’ and organisation’s capabilities (Billett, 2007). Informal learning is now widely accepted as a form of workplace learning that occurs out of a formal planned teaching program. It usually occurs during work activities which are not primarily aimed towards education, with learning objectives not planned beforehand (Callanan et al., 2011; Rogoff et al., 2016; Watkins et al., 2018). Although informal learning had been studied, there are very few studies looking at how being in FTs affects informal learning. A review on the involvement of employees in workplace learning (Kyndt & Baert, 2013) revealed that there was a paucity of literature on whether any team system improves the involvement of employees in informal learning. Thus, it remains to be studied what effects working in a FT system has on informal learning especially of the more junior team members.

An integrative literature review on informal learning found that some of the important components of informal learning within members of a team and between teams included interpersonal relationships, feedback, networking and leadership (Jeong et al., 2018). Therefore, there may be differences in interpersonal relationships and feedback between the different team systems. It is known that good interpersonal relationships include good supervisor and peer support and both affect whether what is learnt is applied at the workplace (Burke & Hutchins, 2016), there was little published data on whether supervisor and peer support or even the supervisory relationship were affected by the amount of time spent together. Within some healthcare systems both FTs and NFTs consists of members with varying levels of experience, differing expertise and roles. In a FT, the learners are only supervised by supervisors within that team; therefore, each learner’s supervised time is divided within a small group of supervisors as compared to a NFT system where each learner’s supervised time is spread amongst a larger number of supervisors. Thus, despite this increased time spent together in a FT, it is not clear if working in a FT impacts supervisory or interpersonal relationship.

Having a good trusted learner-supervisor relationship can result in the establishment of an “Educational Alliance” (Telio et al., 2015). This is because feedback from a credible trusted source was more readily accepted and feedback is another important component of effective informal learning within a team (Jeong et al., 2018).

Furthermore, a study among social work students and their supervisors in a rotational placement model, found that the longer the amount of time they spent with each other the greater the trust between them (Vassos et al., 2017). On the other hand, being in a FT could restrict networking and socialisation to a smaller group of people as contact with other teams’ members could be reduced however it is not known how this could affect informal learning.

Understanding how informal learning takes place within FT and NFT may allow optimisation of learning within each and perhaps even configure teams to enhance learning and thus ultimately improve performance. Our study aimed to fill this gap in the literature by exploring how fixed clinical teams affected the experience of informal learning for Emergency Medicine (EM) Residents. By doing so we hope to understand how informal learning can be supported via the appropriate implementation of team systems especially where high performance is expected from the teams.

II. METHODS

To study how being in fixed clinical teams affected the experience of informal learning for EM Residents we conducted an exploratory qualitative study based on a constructivism research paradigm using content analysis of individual interviews. This is because informal learning could not be quantified with specific learning outcomes.

A. Setting

EDs teams manage a large number of critically ill patients who may need time sensitive interventions. These teams would comprise of experienced Emergency Physicians (EPs) and more junior Medical Officers (MOs) and Residents. The Residents are postgraduate doctors who are training to graduate as EPs; therefore, informal workplace learning is a crucial part of their training. Hence the residents would be good study subjects to investigate the effect of team systems on informal learning.

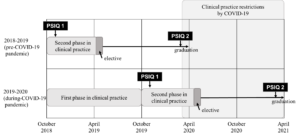

The Singapore General Hospital (SGH) ED functioned via NFTs where the composition and number of members in the team differed with each 8 hour shifts accordingly to the anticipated patient load. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a naturalistic setting where the effect of a FT system can be compared to a NFT system which had existed before hand. After COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on the 11th March 2020 (World Health Organisation, 2020). There was an emphasis on infection control to contain the pandemic. Many countries had instituted social distancing measures which included curfew-like measures and travel restrictions (Lake, 2020). Similarly, the Singapore government had instituted legislative measures to limit face-to-face interactions. In the ED of SGH, measures were put in place to limit the spread of COVID-19.

Thus, from 8th February till 27th September 2020, as part of infection control measures, doctors were organised into 5 FTs, each having between 5-7 Consultants, 3-5 EM Senior Residents, 2-3 EM Junior Residents and 7-9 non-EM Medical Officers (MO) (Liu et al., 2020; Quah et al., 2020). The Senior Emergency Physicians (SEPs) consisted of certified specialists in EM (Associate Consultants, Consultants and Senior Consultants); they played supervisory and educational roles to the junior doctors (JD) which included MOs, Junior Residents and Senior Residents. Each FT worked 12-hour shifts. Interactions between teams were kept to a minimum and members from different teams were not allowed to mingle. Thus, the residents were only supervised by their team’s SEPs. Informal learning would now occur within these FTs.

Formal learning was converted to a remote online platform because of infection control measures. Lectures and tutorials were held and recorded using software which enabled online asynchronous access e.g. Zoom (Zoom, 2016) as not all residents could be given protected learning time together. Sessions which could not be transferred onto an online platform (e.g. hands on simulation and procedure skills training) were cancelled. Formal summative examinations were also cancelled.

B. Interviews

Interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom (Zoom, 2016) to maintain social distancing. The primary investigator performed 11 interviews and a coinvestigator performed the remaining 4 out of a total of 15 interviews. A semi-structured iterative interview guide was developed based on Eraut’s typology on informal learning which included team activities, tasks and enabling/disabling factors (Eraut, 2010) was used, and the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim and anonymised. The interviews allowed positive and negative aspects to be explored and being semi structured the questions asked varied according to the interviewees’ responses. This helped to focus the interviewees to what informal learning was with examples when it could occur within team activities. The guide was iteratively amended with each interview to enhance clarity which helped to obtain more in-depth data in later interviews.

C. Participants

Twenty-four ED residents were working in the FT system in the ED of SGH during COVID-19. Fifteen were Junior Residents and 9 were Senior Residents. Purposive sampling was carried out with at least two Residents from each team being sampled. This is to ensure that there was good representation for all of the fixed clinical teams. All 24 residents were invited to participate via email and WhatsApp messaging platform with written consent being obtained. Fifteen individual interviews were conducted before data sufficiency was achieved where no new data would change the outcome of the study, thus no further interviews were conducted beyond data sufficiency (Varpio et al., 2017). Eleven interviewees were Junior Residents (4 females and 7 males) and 4 were Senior Residents (3 females and 1 male).

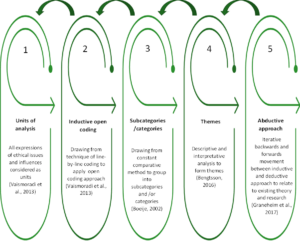

D. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed via template analysis by the primary and coinvestigator independently (Brooks et al., 2015). Eraut’s typology developed from his research on informal learning was used as a priori themes in the initial coding template (Eraut, 2010). Coding template modifications were made as the analysis of the transcripts continued. Themes were categorised into hierarchical clusters and relationships between them were studied and defined. After final modifications, the coding template was applied to the entire data set. Coding themes were compared and discussed between the primary investigator and the coinvestigator until consensus was reached.

E. Ethics

Waiver for approval was granted by the Singhealth Institutional Ethics Board. The primary investigator was a core faculty within the Singhealth Emergency Medicine Residency Program and although the interview was conducted among EM residents the primary investigator did not conduct the interviews when the interviewees were from the same team as the primary investigator. These were conducted by the coinvestigator. The coinvestigator was an EM Senior Resident who was not involved in the FT system. A reflexivity diary was kept, and peer debrief was done.

III. RESULTS

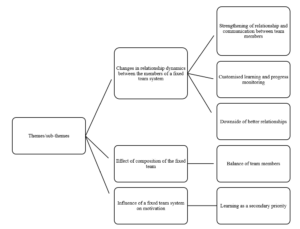

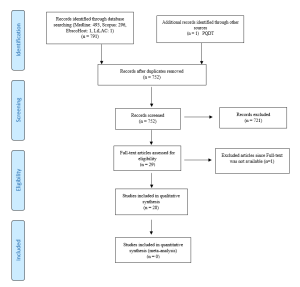

Three main themes emerged on how working in FTs affected informal learning amongst our participants (Figure 1). These included changes in relationship dynamics between members, effect of FT composition on informal learning of the participants and influence on motivation.

Figure 1. Themes and sub-themes

Theme 1: Changes in Relationship Dynamics between FT Members

From the interviews, the participants felt that the FT system resulted in more familiarity, trust, teamwork and improved communications between team members including SEPs, Residents and MOs. Interviewees felt that this strengthened the relationship dynamics between FT members as compared to a NFT. This meant that FT members were able to coordinate and exchange information better. It led to an increase in familiarity in knowing each member’s style of practice and way of thinking. The team members could understand each other better and how they reasoned.

The strengthened relationship between residents and SEPs changed with dynamics. Having a “closer rapport” and “deeper bond” allowed the residents to “tag along” with SEPs “more often” and gave the residents more insight as to why the SEPs behaved in a certain way as to “how they had practiced medicine” and the rationale behind each step was “more easily communicated to the residents who were tagging along” (Resident A), resulting in residents having a deeper understanding of why things were done in addition to how things were done. This strengthened relationship was also present between the residents and their peers. Therefore, peer learning improved within the FTs as junior residents reported feeling less reservation in asking each other questions.

Resident D felt that peer learning was better within FTs because of the improved relationship, there were less reservations which had prevented him from asking his peers questions in a NFT setting.

He elaborated:

“Fixed team [was] definitely better for peer learning. For the same reasons, because you know each other better, you’re more familiar. We don’t only talk to each other about work… after a while, when you go for meals together… or rather like resting together and no cases around you sit and talk. So there’s a lot more familiarity with the person you’re working with, and… you’re just more comfortable with asking questions… you don’t feel like this is somebody who’s going to judge you if [you] asked a stupid question”

This was not just amongst the residents but also with SEPs. Resident G felt that it was easier for the residents to speak to the SEPs because of familiarity and resulted in less workplace stress:

“Over the time as we knew each other better … the workplace stress was much lower… so I could… work with less stress at workplace… Because if you didn’t really know the consultant you tend to be afraid to talk to them; then of course your stress levels will be higher. But if you know that consultant and you know what kind of person, he or she is then you could be more comfortable to talk to them…”

“…It is more comfortable to… approach the senior because you know every day… we have a fixed team so naturally we feel that our relationship is closer…”

“… so, I won’t be too afraid to speak out or to talk to them to discuss with them.”

Contributing to additional ways of informal learning, communication within FTs even during work took on a more “friendly [and] social” form with greater congeniality and via more “communication platforms” (WhatsApp and Tiger Text) which continued even “outside of work” (Resident H). These platforms were also used as learning tools to facilitate case discussions, share learning points and experiences. This was not previously present in the NFTs. The residents felt that learning was more customised because of the change in relationship dynamics. In FTs, there was closer supervision of residents by SEPs. The residents “spent more time” with the same group of supervisors, thus the supervisors were able to better “assess both strengths, weaknesses and address any particular loopholes” of the residents (Resident A).

However, there were some adverse effects of this change in relationship dynamics. Some residents felt that with a closer relationship between team members, supervisors sometimes were more tolerant of the learners’ shortcomings and be less likely to point it out because of not wanting to affect the relationship. This closer relationship could result in residents taking “shortcuts” and “flying under the radar” because they knew the SEPs could tolerate or would not scrutinise the learners closely once “trust” was established (Resident L). Resident H gave an example of how familiarity could lead to less critical thinking by the learner:

“If… the senior always does like… [Rapid Sequence Intubation] … even though I question the first time I saw him do that… subsequently … every time I work with him I will do [it] this way. I won’t really think does the patient really need this way [of management] or will the patient benefit in a different way… if you are working with different bosses then every case you need to restart your thinking…”

Theme 2: Effect of Composition of the FT

All interviewees felt that the composition of the FT had affected informal learning, and that having a balanced team in terms of a wide range of years of practice amongst both the SEPs as well as the JDs would help improve informal learning. Having a team where the JDs were of differing seniorities of practice could help with peer learning because the senior ones could help the junior ones more. This also applied to the SEPs as that provided a wider perspective to clinical issues due to having different clinical experience and expertise in different subspecialties. Furthermore, if the JDs in a FT were of a similar level of practice, Resident C expressed that they could be “competing with each other for cases and procedures” which adversely affected informal learning with fewer opportunities to perform procedures. In a NFT the members would be constantly changing and it would be unlikely its JD would be always of the same level of practice.

The interviewees expressed concern that within a FT system that, although residents had close contact with a fixed group of supervisors, they lacked contact with the other teams’ SEPs. Many residents felt that this had adversely impacted informal learning because the SEPs were experts in different subspecialties (e.g., Trauma, Toxicology, Ultrasound, etc). By not interacting with many SEPs, residents were unable to learn from them. Furthermore, different supervisors had different perspectives and approaches to patients which the residents may not be exposed to if they were not in the same team as these seniors. However, this was mitigated by having a team with a balanced variation in the areas of specialty of the seniors. Resident F summarised this:

“…a team with… people from different seniorities are essential… (even) juniors can teach seniors… the way that my team was composed… it was a good mix… there are people from different… specialties… from different seniorities even within the juniors … like first posting to… [senior post graduate years]… offers different perspectives, learning of different things… people from different [subspecialties] can offer insight into the systems-based learning or component from other parts of the institution…”

Theme 3: Influence of a FT System on Motivation

Many residents felt that having FTs increased their motivation to learn. This resulted from their supervisors being able to inspire them and follow up with their learning progress more closely. Resident M was motivated to learn because his “friends (FT members) were very motivating” and “enthusiastic”; this encouraged him to learn more. Furthermore, resident C felt more motivated to learn in a FT because he “always sees the same senior” and this more frequent contact results in him being “more likely to take their feedback and opinion more seriously and work harder”

However, “after some time everyone is comfortable with each other” and some participants feared that their motivation “might go down” (Resident N). This was because there was a feeling of complacency as time went on within a FT, hence the motivation to learn started to dwindle after an initial increase.

Other reasons for this decline were related to COVID-19, the focus was more on facing the threat rather than learning and the priority to learn was secondary. The motivation to learn “was a bit less” as “the mood was more to survive than to learn”; Resident L was “less driven to learn” because there was a “general bleakness in the whole situation of [COVID-19] which made his “inner desire to learn… wane a bit”

IV. DISCUSSION

This study explored how working in fixed clinical teams affected informal learning for EM Residents. There are many pros and cons to fixed team rostering however the focus of this study is on informal learning. The findings highlighted the importance of having a balanced team composition where team members were able to establish trust and a strong bidirectional relationship because of the longer time spent working together. Motivation to learn increased initially; however after some time, some felt a decrease. This was consistent with prior work which highlighted team dynamics and commitment and that feedback which was given often and in a socially interactive environment were factors which helped to enable effective work-based learning (Attenborough et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2018; Kyndt et al., 2016). Unlike in Attenborough’s work where team leadership was one of the factors identified; our respondents did not mention the effect of team leadership on informal learning. Their focus was more on the relationships between the different team members. From this study the predominant factors which positively affected informal learning included teamwork, collaborative task performance, where good communication was needed between different people, and personal development especially in building interpersonal relationships and group decision making.

Limited studies were done on how FTs affect informal learning. Our study found that FTs resulted in more (informal) communication channels (e.g. WhatsApp) being formed which was not present in NFTs, resulting in more learning activities including sharing ideas, resources and experiences. These sharing activities were some of the major forms of informal learning activities identified in the literature (Lohman, 2006). FTs resulted in open communication and quality feedback which was well received, and were found to be beneficial towards informal learning (Jeong et al., 2018). Our study showed that working in a FTs led to more customised learning. Findings of improved communications and strengthened relationships in a bidirectional manner involving teacher and learner alike, supports a shift from a predominantly teacher to learner type of dynamics to a team learning dynamics where all team members can learn with and from one another. This is important because informal learning takes place effectively when learning from past mistakes and feedback exchange occurs, involving both cognitive and social interactions (Jeong et al., 2018).

FTs had negative effects on informal learning as well. Familiarity resulted in supervisors being more tolerant of shortcomings and FTs limited learners’ contact with other teams’ supervisors and adversely affected informal learning. This was because informal learning also takes place when there is sharing of ideas, expertise and experience (Lohman, 2006) and limiting the number of supervisors limits the variance of shared viewpoints.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, interviewee recall bias was possible because 6 months had passed after the FT system was stopped before the interviews. Therefore, some details may not have been accurately recalled given this period which could affect the trustworthiness of results. Secondly, the participants were likely to be comparing their experiences in the FT system during COVID-19 to a NFT system without a pandemic. Thus, some of the experienced changes may be because of the pandemic rather than purely due to the FT system. Thirdly, there are many pros and cons to FTs however the focus of this study is on informal learning thus other factors not investigated with this study may affect the feasibility of FT. Lastly there could be power differential effects between the interviewers and the interviewees because the interviewers performed supervisory and roles to the residents. However, to mitigate this, a reflexivity diary was kept, and peer debrief between the two interviewers was performed. Furthermore, the interviewers did not interview members who had been in the same team as them.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, FTs impact informal learning by building strong relationships with improved team communications and adding a social dimension for learning. A balance of team members as well as rotating the residents across different FTs may be beneficial for improving informal learning for EM Residents.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Wee Choon Peng Jeremy submitted the CIRB application, (with the help of the last author) conceptualised the study and its design. He performed the literature review, recruited and interviewed the participants, collected and transcribed the data, performed the thematic analysis of the data and wrote the manuscript.

Dr Ng Mingwei helped to recruit and interview some of the participants, transcribed and collected the data. Dr Ng helped perform the thematic analysis of the data and helped edit the manuscript.

Prof. Dr. Pim Teunissen was central to the conceptualisation of the study, advised on the design of the study and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript and edited the manuscript extensively

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

We have included the letter for waiver of CIRB via email. Ethics approval for waiver of written informed consent was obtained from the Singhealth Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2020/3114).

Data Availability

As the data set is qualitative in nature, we are not able to upload that in any public repository.

Funding

There is no funding for this paper/study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

Attenborough, J., Abbott, S., Brook, J., & Knight, R. A. (2019). Everywhere and nowhere: Work-based learning in healthcare education. Nurse Education in Practice, 36, 132-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2019.03.004

Barker, J. M., Clothier, C. C., Woody, J. R., McKinney, E. H., Jr., & Brown, J. L. (1996). Crew resource management: A simulator study comparing fixed versus formed aircrews. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 67(1), 3-7.

Billett, S. (2007). Constituting the workplace curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(1), 31-48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270500153781

Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2015). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 202-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2016). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 263-296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484307303035

Callanan, M., Cervantes, C., & Loomis, M. (2011). Informal learning. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Cognitive Science, 2(6), 646-655. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.143

Eddy, K., Jordan, Z., & Stephenson, M. (2016). Health professionals’ experience of teamwork education in acute hospital settings: a systematic review of qualitative literature. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews Implementation Reports, 14(4), 96-137. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-1843

Eraut, M. (2010). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in continuing education, 26(2), 247-273. https://doi.org/10.1080/158037042000225245

Gjeraa, K., Spanager, L., Konge, L., Petersen, R. H., & Ostergaard, D. (2016). Non-technical skills in minimally invasive surgery teams: A systematic review, Surgical Endoscopy, 30(12), 5185-5199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4890-1

Jeong, S., Han, S. J., Lee, J., Sunalai, S., & Yoon, S. W. (2018). Integrative literature review on informal learning: Antecedents, conceptualizations, and future directions. Human Resource Development Review, 17(2), 128-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318772242

Kyndt, E., & Baert, H. (2013). Antecedents of employees’ involvement in work-related learning. Review of Educational Research, 83(2), 273-313. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313478021

Kyndt, E., Vermeire, E., & Cabus, S. (2016). Informal workplace learning among nurses. Journal of Workplace Learning, 28(7), 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-06-2015-0052

Lake, M. A. (2020). What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research. Clinical Medicine, 20(2), 124-127. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2019-coron

Liu, Z., Teo, T. L., Lim, M. J., Nadarajan, G. D., Segaram, S. S. C., Thangarajoo, S., Wee, L. E., Wee, J. C. P., & Tan, K. B. K. (2020). Dynamic emergency department response to the evolving COVID-19 pandemic: The experience of a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 1(6),1395-1403. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12264

Lohman, M. C. (2006). Factors influencing teachers’ engagement in informal learning activities. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 141-156. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654577

Quah, L. J. J., Tan, B. K. K., Fua, T. P., Wee, C. P. J., Lim, C. S., Nadarajan, G., Zakaria, N. D., Chan, S. J., Wan, P. W., Teo, L. T., Chua, Y. Y., Wong, E., & Venkataraman, A. (2020). Reorganising the emergency department to manage the COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), Article 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00294-w

Rogoff, B., Callanan, M., Gutiérrez, K. D., & Erickson, F. (2016). The organization of informal learning. Review of Research in Education, 40(1), 356-401. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732×16680994

Stepaniak, P. S., Heij, C., Buise, M. P., Mannaerts, G. H., Smulders, J. F., & Nienhuijs, S. W. (2012). Bariatric surgery with operating room teams that stayed fixed during the day: A multicenter study analyzing the effects on patient outcomes, teamwork and safety climate, and procedure duration. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 115(6), 1384-1392. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826c7fa6

Telio, S., Ajjawi, R., & Regehr, G. (2015). The “Educational Alliance” as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education. Academic Medicine, 90(5), 609-614. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560

Varpio, L., Ajjawi, R., Monrouxe, L. V., O’Brien, B. C., & Rees, C. E. (2017). Shedding the cobra effect: Problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Medical Education, 51(1), 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13124

Vassos, S., Harms, L., & Rose, D. (2017). Supervision and social work students: Relationships in a team-based rotation placement model. Social Work Education, 37(3), 328-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1406466

Watkins, K. E., Marsick, V. J., Wofford, M. G., & Ellinger, A. D. (2018). The evolving Marsick and Watkins (1990) theory of informal and incidental learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2018(159), 21-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20285

World Health Organisation. (2020). World Health Organisation emergencies press conference on coronavirus disease outbreak – 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

Zoom. (2016). Security guide. Zoom Video Communications Inc.

*Wee Choon Peng Jeremy

Outram Road,

Singapore 169608

Email: jeremy.wee.c.p@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 26 November 2021

Accepted: 21 July 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 33-42

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/OA2712

Jaime Maria Tan1, Junaidah Binte Badron1 & Sashikumar Ganapathy1,2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, KK Women’s & Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 2Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Perceptions towards the working and learning environment as well as coping mechanisms have been studied across different healthcare sectors. They have shown to reduce stress and burnout. However, perceptions of the work environment in the Emergency Department (ED) setting have not been studied in depth. The literature surrounding coping mechanisms also mostly focuses on their impacts rather than the mechanisms utilised. In addition, these were often investigated using surveys. This study aimed to use a phenomenological approach to explore the perceptions and coping strategies of junior doctors working in a paediatric ED.

Methods: Sixteen junior doctors working in the Paediatric ED were recruited. Semi-structured interviews were conducted after conducting literature reviews. Data was collected until saturation point. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim manually and subsequently analysed.

Results: The greatest fears of junior doctors starting their paediatric emergency posting were lack of knowledge due to inexperience in the subspecialty; fear of the work environment due to unfamiliarity as well as workload and the intrinsic high-stress environment. The main coping strategies were ensuring clinical safety, obtaining psychosocial support from loved ones and colleagues, and placing focus on spirituality and wellbeing.

Conclusion: In this study, the perceptions and coping strategies of the junior doctors in the Paediatric ED were explored. The findings from this study will help to structure and improve the support given to future junior doctors who rotate to the department as well as better orientate them to allay their pre-conceived notions.

Keywords: Coping Behaviours, Perceptions, Paediatric Emergency Department, Stressors, Interviews

Practice Highlights

- Participants worried about knowledge, workload and responsibilities prior to starting their posting.

- Perceptions were mostly of an anticipatory nature, influenced by seniors’ past experiences.

- In work, support from senior staff was helpful in allaying their fears and increasing patient safety.

- Participants felt psychosocial support, spirituality and wellness were useful coping strategies.

- Maladpative coping strategies did not come up as a main theme in our study.

I. INTRODUCTION

Perceptions toward the work and learning environment can strongly impact experiences and even lead to large amounts of stress (Chan et al., 2016). A poorer perception of the learning environment is also associated with greater levels of burnout (Chew et al., 2019; Sum et al., 2019). Conversely, a positive perception of the work environment helps to alleviate stress (Abraham et al., 2018). Workers’ perception of their work environment contributes significantly to their overall experiences.

Main factors contributing to stress in the ED include heavy workload and critically ill patients. Workplace violence, trauma, abuse and morbidity also add to the stress and burnout experienced (Burbeck et al., 2002; Copeland & Henry, 2018; Healy & Tyrrell, 2011; Xu et al., 2019). In the paediatric setting, added stressors include dealing with sexual abuse and non-accidental injury as well as death and the inability to provide optimal care for children (Alomari et al., 2021; Basu et al., 2016; Durand et al., 2019; Greenslade et al., 2019; Shanafelt et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2019).

Given these significant stressors, individuals utilise different coping mechanisms to mediate these experiences (Howlett et al., 2015).

Some coping strategies discussed in previous studies include socialising with friends and family (Gribben et al., 2019). Focusing on physical wellbeing, clinical variety, reflectivity, and organizational activities were also helpful in alleviating burnout in other areas of healthcare (Barham et al., 2019; Koh et al., 2015).

Several studies also found that the use of maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as alcohol use and self-blame increased with the frequency of burnout (Jackson et al., 2016; Oreskovich et al., 2015; Ryali et al., 2018; Talih et al., 2018).

While many studies studied stressors and the effectiveness of the coping mechanisms used, the actual components of coping mechanisms were not well studied. In studies that did look at coping mechanisms and their effectiveness, these studies were also often done via the survey method and were only evaluated on the surface.

Most studies looked at healthcare workers in general. Few studies looked solely at the doctor population. This makes conclusively evaluating the doctor component of coping mechanisms and their effects difficult.

While other studies looked at an adult emergency perspective, there were also few studies looking at the paediatric ED. It has been reported that dealing with paediatric emergencies causes more stress compared to their adult equivalents. Some of the contributing factors are related to the nature of working with children. These, in itself, are unmodifiable (Guise et al., 2017). Therefore, it is important to study how the paediatric context can affect the experiences of the doctors who care for them.

In our study, we studied the perceptions of junior doctors at the beginning of their posting. We subsequently explored their coping mechanisms in the Singaporean context.

The element of stress in the ED among junior doctors is significant as the ED is often part of many specialist training pathways (Mason et al., 2015). During the time of training, the doctors are still learning and developing. Hence, many doctors experience sharp learning curves during their postings. This brings about more stress (McPherson et al., 2003). In some cases, the stress can even lead to doctors thinking about leaving clinical practice altogether (Degen et al., 2014).

In the Singaporean context, paediatric emergency postings are part and parcel of speciality training for junior doctors (especially for those in emergency medicine and family medicine training). Because of this, junior doctors spend the majority of their paediatric postings in the paediatric emergency. As such, a Singapore-specific context would give light on the challenges of this sizable group.

The nature of the healthcare system in Singapore is unique. Up to 60% of the consultations in the paediatric ED were for nonurgent conditions due to the overall perception of the severity of symptoms and parental preference towards paediatric specialist facilities (Ganapathy et al., 2015). This would lead to an increased workload for the paediatric ED. The distribution in workload may also differ compared to a global perspective, with the load of severe paediatric trauma in Singapore being low (Pek et al., 2019).

These subtleties in the paediatric ED in Singapore can influence the experiences of junior doctors differently. With these key differences in mind, we aimed to investigate the perceptions of junior doctors towards their paediatric ED posting in Singapore and how they subsequently coped with the challenges faced.

II. METHODS

A. Design

In this study, we examined the experiences of doctors in their paediatric ED rotation and how their thoughts and actions influenced their stress during their rotation. We deemed the phenomenological approach to be the most appropriate for this study. Phenomenology is defined as the study of how individuals see and experience a phenomenon and what this means to the individuals in their own experience (Neubauer et al., 2019; Smith, 2021).

The approach we chose was that of an interpretive phenomenological analysis in which we aimed to investigate the experience through the participants’ own experiences and perceptions. With the help of the various participants’ accounts, themes and ideas bound by their experiences were explored (Tuffour, 2017).

B. Methods

The members of the study performed a preliminary literature review on the topic and explored plausible methods of data collection. The study team decided on semi-structured interviews as it promotes sharing and would allow for sufficient privacy.

The team members included a senior consultant, a staff physician and a medical officer. Together, after discussions about concepts that the team was keen to explore, an interview guide was drawn up.

Subsequently, a proposal was submitted to the Hospital Centralised Institutional Review Board for approval.

One-on-one interviews were conducted with the participants by investigator A, a medical officer who was rotating within the department at the time of the study. This was done to reduce the power differential. Interviews were conducted at a location and time convenient to the participant.

Prior to the interviews, consent was sought and all interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. The interviews were conducted over a 1-month period in December 2019.

Questions were open-ended and allowed participants to share ideas that they were keen to raise with no restrictions to the topics brought up. Interview questions were tweaked alongside subsequent interviews so that they were easier to understand and would encourage sharing. Additional questioning in subsequent interviews was adopted to improve clarity. For example, one of the questions that featured early in the interviews was ‘What are some of the coping mechanisms you use?’ During subsequent interviews we noticed some participants utilised coping mechanisms before work to prepare themselves, some used other strategies during work to cope with the stress, while others dealt with their stressors after getting off work. We tweaked the question to include ‘during the shift or outside of the shift’ to help participants widen their perspective about certain coping methods they may have used but were not immediately conscious of when answering the questions. No new questions referring to particular themes were inserted although interviewers were aware of the themes that had been highlighted in previous interviews. This was done in addition to the initial interview guide and ensured the broad nature of questioning was not compromised and the breadth of interviews was maintained.

Themes were identified from the interviews until data saturation was reached. Data saturation was noted at the 12th interview. The team continued to learn from subsequent interviews, with interviews contributing additional depth to the issues explored. Further interviews were conducted to confirm that no new theme was being identified.

The interviews were then transcribed and de-identified. They were subsequently reviewed by 2 reviewers (Investigator A and Investigator B). Data was analysed using a step-by-step thematic analysis method (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Investigators A and B independently analysed the transcripts, identified themes and later reported the common themes. These themes were discussed for concurrence. When any differences in opinion arose, these would be reviewed by investigator C to resolve any disagreement.

C. Setting

The research was conducted within the Paediatric ED in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, a tertiary paediatric hospital.

The Children’s Emergency of KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital is the largest paediatric emergency unit in Singapore. During the time of the interviews, the department treated over 400 patients daily. The Children’s Emergency sees all children under the age of 18 years for all medical complaints.

The department is staffed by over 60 junior doctors at a single time. These junior doctors come from various backgrounds and pass through the department for varying amounts of time. Thus, their experience can be very heterogeneous.

The job scope and responsibilities of all the junior doctors are primarily the same despite the different levels of experience. They are expected to treat the patients that present to the ED. These doctors can seek advice from the senior doctors who are on the ground. However, for the majority of the time, they would be tasked to treat patients on their own.

D. Participants

Participants were recruited through an email that was circulated to all junior doctors in the department. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants were not remunerated.

A total of 16 junior doctors were recruited and interviewed over a 1-month period. Due to the busyness of the ED and the limited time frame in which the interviews were conducted, only 16 interviews were conducted. Convenience sampling was chosen for the sampling method. The first 16 volunteers who had volunteered were interviewed. However, it was noted that saturation point was reached prior to the conclusion of the interview process.

The variety within the ED was well represented. The details of participant breakdown are elaborated on in Table 1.

|

Experience & Training Information |

|

|

|

|

|

Mean post-graduate year, 3.6 (2-6)* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emergency Medicine |

Family Medicine |

Paediatric Medicine |

Not in a training program at time of study |

|

Training Program (n=16) |

5 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|

Epidemiological Data |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chinese |

|

Indian |

|

|

Race (n=16) |

13 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

Male |

|

Female |

|

|

Gender (n=16) |

6 |

|

10 |

|

Table 1: Characteristics of Participants

*Mean (Range)

E. Analysis

All transcripts were reviewed by JT and SG. Coding was done manually using Microsoft Word. During the process, themes were identified and substantiating quotes were recorded. Iterative data analysis was done so that interviewers were aware of themes that were previously mentioned. However, the themes were not specifically explored unless brought up by the subsequent interviews.

III. RESULTS

Through the interviews, we collected information about the experiences within the ED. Interview transcripts collected as a part of this study are openly available on Figshare at http://doi.org./10.6084/m9.figshare.19204761 (Tan et al., 2022). From the interviews conducted, the experience was divided into the initial perceptions and coping mechanisms.

A. Perceptions

The perceptions of the paediatric emergency rotation in the ED were largely contributed by the experiences of the individuals who had previously worked in the department. This was achieved through consultation with friends or colleagues prior to starting the posting to find out more about the rotation.

“Before I started doing the posting, I asked some people who have done or were currently doing the posting…to find out what I was getting myself into”

(P7)

The broad themes elicited about the perceptions and inherent worries of the incoming medical officers were that of being unprepared due to ‘inadequate knowledge’ or ‘unfamiliarity’, as well as the impending ‘work load’ and ‘work factors’.

1) Fear of subject matter: Participants who were not familiar with the paediatric content were worried about their competency and adequacy in treating children. Oftentimes, participants cited that exposure to the paediatric subject matter may have been inadequate or dated and as a result, resulted in fears of being unprepared or being unsafe.

“I’ve not done any paediatric postings before as a doctor so that was a bit worrying.”

(P4)

“I’ve never dealt with paediatrics before so it was quite scary to come onto the posting”

(P14)

In participants who did however have some background in paediatrics, additional fears of specialised emergency knowledge also emerged with participants feeling nervous about the posting.

“Some of the things included technical skills such as doing back slabs, manipulation and reduction, and I guess managing trauma and more complicated acute conditions such as diabetic ketoacidosis and haemophilia and oncological and metabolic related conditions.”

(P11)

“When I started I learnt about resuscitation cases which I felt was a bit nerve-wracking to start with”

(P12)

2) Unfamiliarity: Even though participants may have been at different time points in their careers during the posting, they were all expected to perform mostly the same duties and responsibilities. As a result, a section of the participants cited worries about adjusting to the roles and environment that they may have been new to. These included concerns about being new to the system used. These added to the worries that participants often had about starting a new posting and made participants even more fearful.

“Coming from the UK, this was my first job in Singapore as a MO and thus had close to 0 experience of working in Singapore”

(P8)

“I was also not very familiar with the system. It added to the fear and unpreparedness before starting the posting.”

(P9)

3) Work factors: As a place with high turnover and workload, the picture painted to many of the participants was that it may be difficult to cope with the high workload. This would result in participants being overloaded and overwhelmed. A level of uncertainty was also described. Many participants were left feeling fearful, apprehensive and unsure of what to expect during the upcoming posting. Some were also worried about the expectations they may have to live up to and the nature of the environment being extremely stressful.

“I just heard that it can be quite busy with many patients and at the beginning, it can feel a bit of a throw into the deep end as we often don’t know what to expect and the learning curve can be quite steep”

(P12)

“I was also a bit apprehensive as I heard how busy the posting could get”

(P10)

“It’s quite a stressful working environment because the seniors have a certain working expectation and if you can’t live up to the expectations.”

(P16)

Practically, participants were also worried about the potential to get sufficient rest. Many participants heard that manpower may be tight and would result in having fewer or insufficient off days and would run the risk of feeling tired and burnt out.

“I heard that it was also difficult to get leave that you want and that you would also be really tired during the posting”

(P13)

B. Coping Mechanisms

We then explored the different ways the participants utilised to cope with their experiences in the ED. Participants used a variety of means that we broadly classified into broad themes of ensuring clinical safety, psychosocial support and spirituality.

1) Clinical safety: Participants were inevitably worried about competency and had inherent fears of patient safety in their practice. Coping strategies in this realm could be divided into preparation, senior supervision and collegial opinion.

Preparation was often seen in speaking to doctors who had previously rotated through the posting to allow junior doctors to prepare themselves mentally.

“I asked around and tried to mentally prepare myself for what people told me to expect”

(P3)

In addition, the perceived knowledge gaps and lack of experience were dealt with by many participants through studying and reading up to cover these gaps as well as to prevent them from feeling out of depth.

“I had actually read the guidelines prior especially for the things that I was not familiar with.”

(P10)

On the ground, participants found the availability and approachability of help and support from senior colleagues helpful in easing the worry and anxiety experienced in the emergency department. This also helped participants feel more safe and secure in their practices in the emergency department.

“I appreciate the nice seniors. Most of the seniors are approachable and they treat us like fellow colleagues. They respect our opinions and try to keep it in mind”

(P10)

“I feel very safe at work and very well supported by the seniors. In general, it is easy to ask for help from most of the seniors.”

(P8)

In addition, many participants also felt that their fellow medical officer colleagues were also important in ensuring safety in their practice. With different levels of experience, they could bounce ideas off each other and get a second opinion from their peers. Furthermore, their colleagues also helped to pick up the workload when they felt overwhelmed.

“Everyone is willing to help out when you get stuck. Help is useful and it is easy to come by”

(P1)

“I feel like I have a good relationship with them (peers) and that helps me and I can also get second opinions from them if I’m unsure.”

(P9)

2) Psychosocial support: In the high-strung environment of the emergency department, there is a lot of stress and emotions that come with the job. We found that many participants shared about the social component involved in unpacking these emotions and relieving their stress. The components of the collegial environment and support from loved ones appeared to be crucial coping mechanisms that helped participants.

The work climate was cited to be collegial and relationships between co-colleagues were described as friendly. Many participants felt comfortable with their co-colleagues such that they could ventilate their emotions and experiences with one another. These helped participants process and debrief their experiences.

“We generally laugh about the situation together and it gets better. Sometimes they give advice based on what they have seen and how to avoid such circumstances and we try and help each other.”

(P7)

“It’s useful amongst colleagues because we go through the same things and we get to exchange ideas and I feel we get to debrief this way as well. That helps because we don’t feel like we go through it alone because we have similar experiences.”

(P8)

Apart from the work environment, supportive loved ones and close friends also helped participants cope with difficult days. Participants cited that out of work encounters helped them to get through tough days and relieve their stress.

“Sometimes I also talk about it with someone. Usually that helps and my stress doesn’t usually last beyond the same day.”

(P6)

“I guess these 3 things, my family, friends and colleagues help me with tough days.”

(P7)

3) Spirituality and wellness: Spirituality and wellbeing were also important in dealing with the experiences and stressors the participants faced. Apart from dealing with the clinical stressors and unpacking the experiences with others, participants also spoke about coming to terms with their experiences and emotions on their own. This involved components of religion and reflexivity. Participants also spoke about the role of maintaining their wellbeing with leisure and self-care activities.

Participants spoke about reflecting and reviewing the good as well as the bad moments at work. These helped the participants make sense of their experiences and as a result, helped them improve and learn.

“I usually pray and reflect on my day and think about what are the good points I can get out of the day.”

(P9)

Religion also featured as a means of coping with emotions in the sometimes chaotic environment seen in the ED. These helped participants work better and feel more focused at work.

“I feel like I’m stable when I pray … and I think more thoughts are more ordered. That helps me.”

(P15)

Focusing on physical wellbeing also helped to reduce the stress experienced. Participants cited different activities – food, sleep, exercise, self-care and hobbies that helped them take their minds off work and help them get rejuvenated before the next working day.

“Eating and relaxing help me after a tough day”

(P4)

“I find exercising is helpful, and it helps me feel fresher and less sleepy”

(P3)

“Listening to music and watching videos and just going about non-work related normal daily life.”

(P11)

“I ensure that I have a good work-life balance… I go for a massage, go for a buffet, watch a movie and enjoy myself.”

(P13)

“I draw, I paint. I learn languages. Sometimes I travel. These things help me relax and cope with stress.”

(P16)

IV. DISCUSSION

We sought to understand the perceptions of junior doctors starting out in the emergency department as well as the subsequent coping strategies they undertook for challenges that they faced. During the process, we interviewed sixteen junior doctors who spoke in detail about their experiences.

The perceptions that the junior doctors in our study described consisted mainly of their worries and concerns prior to the start of the posting. Most of the perceptions and worries were centred on knowledge, workload and responsibilities that came with the posting.

A large proportion of participants expressed worry regarding competency and personal comfort levels in managing children. As the ED is a broad one and knowledge is inexhaustible, the concerns in lack of competency are seen in the other elements of emergency care and not strictly paediatric emergency (Jelinek et al., 2013; Kennelly et al., 2012; Yong & Ng, 2016).

Many of the worries described by the participants were of an anticipatory nature, from hearing their predecessors’ experiences. Anticipation of negative experiences can lead to anxiety and stress in individuals (Carlson et al., 2010; Grupe & Nitschke, 2013). Participants had anxiety about the workload and certain work factors prior to the start of the posting. While predecessors’ recounts are helpful in preparing doctors for their upcoming experience, the anxiety that comes with this preparation may not be. Positive effects can also be seen when a positive picture is painted of the upcoming experience (Gangwal et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2018). As it is difficult to balance the negative anxiety and the positive effects of preparation, it may be helpful for junior doctors to receive a formal handover from existing doctors who themselves have had a positive experience so as to prevent excessive anxiety.

We next explored the coping strategies involved to help the participants through the difficult parts of their experiences.

In areas of safety, participants commented on how the support from the senior staff helped allay their fears and increase patient safety at work. Other studies showed similar themes with HCWs expressing the desire for support, professional help and preventive action in the ED (Mikkola et al., 2019; Povedano-Jimenez et al., 2020; Ruotsalainen et al., 2015). In situations where support was provided, these corresponded to higher levels of satisfaction at work (Hunsaker et al., 2015). This is especially so in HCWs who were exposed to traumatic situations (Zhao et al., 2015).

Social support is an important factor in dealing with stressful situations (Gribben et al., 2019). In our cohort, our participants also engaged in social interactions with family, friends and colleagues in an attempt to deal with stressors in the ED. The collegial environment was also beneficial in dealing with stress and helping participants better process their experiences (Povedano-Jimenez et al., 2020).

Apart from expressing emotions and stressors, participants also sought to ensure mental and physical wellness of oneself. This was done by focusing on their spirituality as well as physical wellness and self-care. These strategies utilised were similar to those seen in other studies (Gribben et al., 2019; Hoonpongsimanont et al., 2013; McPherson et al., 2003; Palmer Kelly et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019).

Maladaptive coping strategies did not come up as a main theme in our interviews.

A. Limitations

The study was conducted in a single ED at a single time point. Efforts were taken to diversify the population interviewed with participants experiencing different durations within the department. However, interviews of participants who had experienced the ED at different time points could have brought about different views and themes.

The primary investigator was also working within the same department during the time of the study. As the investigator was also a junior doctor during the study, a power dynamic effect was minimised.

The setting was limited to a single centre in the Singapore setting and thus, was extremely specific. Singapore is a city-state with easy access to healthcare. In addition, due to strict legislation, violence is minimal compared to other areas. As such, the patient load and patient type may differ from other ED and may raise the question of applicability in a different setting.

In addition, this study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the findings were representative of the climate at that time. The pandemic has led to multiple changes in workflow and work culture in the paediatric ED, and these may affect the applicability of our findings.

B. Future Research and Practical Implications

The study is the first qualitative in-depth study looking at perceptions and coping strategies in a paediatric emergency setting among junior doctors in a single centre. It is the first study to explore the individual perceptions and coping mechanisms of doctors, with a focus on the subset of junior doctors. The group was relatively small and conducted at a single time point. As such, the study can be expanded to include a larger group of participants across different time points and centres to illustrate a bigger picture.

Many of the participants also talked about the challenges they experienced in the paediatric emergency. They also raised possible improvements that could be made to help with stressors and challenges in the ED. This could be studied further and future research could focus on how we could target these factors and how effective these adjustments can be.

The findings of this research echoed the findings of prior studies. This study also sheds light and gives us more depth in terms of the early perceptions prior to the start of the postings and the coping strategies that were used.

These findings can also help future doctors rotating through the ED picture the experience. This would give doctors an opportunity to decide how best to prepare themselves. It could also help the doctors feel united with their current colleagues and predecessors in their challenges. And that they are not alone in their experiences.

V. CONCLUSION

In this study, the perceptions of junior doctors and coping strategies of junior doctors in an Asian Paediatric ED were studied. We looked at the perceptions and coping strategies utilised. Many factors were established in contributing to the experience. Improvements and suggestions to improve the experience were also brought up. Other HCWs can also understand how to best work with the junior doctors to facilitate an effective and pleasant working environment.

Notes on Contributors

Jaime Tan undertook literature reviews, conducted and analysed interviews and drafted the manuscript. Junaidah Badron reviewed the interviews and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. Sashikumar Ganapathy conceived the idea of the study, reviewed and analysed interview transcripts and advised the manuscript design. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This project was submitted to the Centralised Institutional Review Board for approval (CIRB Ref 2019.2772). All participants consented to the research study.

Data Availability

All data collected in this study are openly available on Figshare repository, http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19204761

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all participants for volunteering their time and agreeing to participate in this study.

Funding

No funding was involved in this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

Abraham, L. J., Thom, O., Greenslade, J. H., Wallis, M., Johnston, A. N., Carlström, E., Mills, D., & Crilly, J. (2018). Morale, stress and coping strategies of staff working in the emergency department: A comparison of two different-sized departments. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 30(3), 375-381. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.12895

Alomari, A. H., Collison, J., Hunt, L., & Wilson, N. J. (2021). Stressors for emergency department nurses: Insights from a cross‐sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(7-8), 975-985. https://doi.org10.1111/jocn.15641

Barham, D., De Beer, W., & Clark, H. (2019). The role of professional supervision for palliative care doctors in New Zealand: A quantitative survey of attitudes and experiences. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 132(1501), 10–20.

Basu, S., Yap, C., & Mason, S. (2016). Examining the sources of occupational stress in an emergency department. Occupational Medicine, 66(9), 737–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqw155

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burbeck, R., Coomber, S., Robinson, S. M., & Todd, C. (2002). Occupational stress in consultants in accident and emergency medicine: A national survey of levels of stress at work. Emergency Medicine Journal, 19(3), 234–238. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.19.3.234

Carlson, J. M., Greenberg, T., Rubin, D., & Mujica-Parodi, L. R. (2010). Feeling anxious: Anticipatory amygdalo-insular response predicts the feeling of anxious anticipation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 6(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq017

Chan, C. Y. W., Sum, M. Y., Lim, W. S., Chew, N. W. M., Samarasekera, D. D., & Sim, K. (2016). Adoption and correlates of Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) in the evaluation of learning environments – A systematic review. Medical Teacher, 38(12), 1248–1255. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2016.1210108

Chew, Q. H., Ang, L. P., Tan, L. L., Chan, H. N., Ong, S. H., Cheng, A., Lai, Y. M., Tan, M. Y., Tor, P. C., Gwee, K. P., & Sim, K. (2019). A cross-sectional study of burnout and its associations with learning environment and learner factors among psychiatry residents within a National Psychiatry Residency Programme. BMJ Open, 9(8), e030619. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030619

Copeland, D., & Henry, M. (2018). The relationship between workplace violence, perceptions of safety, and professional quality of life among emergency department staff members in a Level 1 Trauma Centre. International Emergency Nursing, 39, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2018.01.006

Degen, C., Weigl, M., Glaser, J., Li, J., & Angerer, P. (2014). The impact of training and working conditions on junior doctors’ intention to leave clinical practice. BMC Medical Education, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-119

Durand, A. C., Bompard, C., Sportiello, J., Michelet, P., & Gentile, S. (2019). Stress and burnout among professionals working in the emergency department in a French university hospital: Prevalence and associated factors. Work, 63(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-192908

Ganapathy, S., Lim, S. Y., Kua, J. P., & Ng, K. C. (2015). Non-urgent paediatric emergency department visits: Why are they so common? A Singapore perspective. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 44(7), 269–271. https://doi.org/10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.v44n7p269

Gangwal, R. R., Rameshchandra Badjatia, S., & Harish Dave, B. (2014). Effect of exposure to positive images of dentistry on dental anxiety among 7 to 12 years old children. International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry, 7(3), 176–179. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1260

Greenslade, J. H., Wallis, M., Johnston, A. N. B., Carlström, E., Wilhelms, D. B., & Crilly, J. (2019). Key occupational stressors in the ED: an international comparison. Emergency Medicine Journal, 37(2), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2018-208390

Gribben, J. L., Kase, S. M., Waldman, E. D., & Weintraub, A. S. (2019). A cross-sectional analysis of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in paediatric critical care physicians in the United States*. Paediatric Critical Care Medicine, 20(3), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000001803

Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3524

Guise, J. M., Hansen, M., O’Brien, K., Dickinson, C., Meckler, G., Engle, P., Lambert, W., & Jui, J. (2017). Emergency medical services responders’ perceptions of the effect of stress and anxiety on patient safety in the out-of-hospital emergency care of children: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 7(2), e014057. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014057

Healy, S., & Tyrrell, M. (2011). Stress in emergency departments: Experiences of nurses and doctors. Emergency Nurse, 19(4), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.7748/en2011.07.19.4.31.c8611

Hoonpongsimanont, W., Murphy, M., Kim, C. H., Nasir, D., & Compton, S. (2013). Emergency medicine resident well-being: Stress and satisfaction. Occupational Medicine, 64(1), 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqt139

Howlett, M., Doody, K., Murray, J., LeBlanc-Duchin, D., Fraser, J., & Atkinson, P. (2015). Burnout in emergency department healthcare professionals is associated with coping style: A cross-sectional survey. Emergency Medicine Journal, 32(9), 722–727. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2014-203750

Hunsaker, S., Chen, H. C., Maughan, D., & Heaston, S. (2015). Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12122

Jackson, E. R., Shanafelt, T. D., Hasan, O., Satele, D. V., & Dyrbye, L. N. (2016). Burnout and alcohol abuse/dependence among U.S. medical students. Academic Medicine, 91(9), 1251–1256. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001138

Jelinek, G. A., Weiland, T. J., Mackinlay, C., Gerdtz, M., & Hill, N. (2013). Knowledge and confidence of Australian emergency department clinicians in managing patients with mental health-related presentations: Findings from a national qualitative study. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 6, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1865-1380-6-2

Kennelly, S. P., Morley, D., Coughlan, T., Collins, R., Rochford, M., & O’Neill, D. (2012). Knowledge, skills and attitudes of doctors towards assessing cognition in older patients in the emergency department. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 89(1049), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131226

Koh, M. Y. H., Chong, P. H., Neo, P. S. H., Ong, Y. J., Yong, W. C., Ong, W. Y., Shen, M. L. J., & Hum, A. Y. M. (2015). Burnout, psychological morbidity and use of coping mechanisms among palliative care practitioners: A multi-centre cross-sectional study. Palliative Medicine, 29(7), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315575850

Luo, Y., Chen, X., Qi, S., You, X., & Huang, X. (2018). Well-being and anticipation for future positive events: Evidences from an fMRI Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02199

Mason, S., O’Keeffe, C., Carter, A., & Stride, C. (2015). A longitudinal study of well-being, confidence and competence in junior doctors and the impact of emergency medicine placements. Emergency Medicine Journal, 33(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2014-204514

McPherson, S., Hale, R., Richardson, P., & Obholzer, A. (2003). Stress and coping in accident and emergency senior house officers. Emergency Medicine Journal, 20(3), 230–231. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.20.3.230

Mikkola, R., Huhtala, H., & Paavilainen, E. (2019). Development of a coping model for work‐related fear among staff working in emergency department in Finland – Study for nursing and medical staff. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(3), 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12658

Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T., & Varpio, L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

Oreskovich, M. R., Shanafelt, T., Dyrbye, L. N., Tan, L., Sotile, W., Satele, D., West, C. P., Sloan, J., & Boone, S. (2015). The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12173

Palmer Kelly, E., Hyer, M., Payne, N., & Pawlik, T. M. (2020). A mixed-methods approach to understanding the role of religion and spirituality in healthcare provider well-being. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12(4), 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000297

Pek, J. H., Ong, Y. K. G., Quek, E. C. S., Feng, X. Y. J., Allen, J. C., Jr., & Chong, S. L. (2019). Evaluation of the criteria for trauma activation in the paediatric emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal, 36(9), 529–534. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2018-207857

Povedano-Jimenez, M., Granados-Gamez, G., & Garcia-Caro, M. P. (2020). Work environment factors in coping with patient death among Spanish nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 28. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.3279.3234

Ruotsalainen, J., Verbeek, J., Mariné, A., & Serra, C. (2015). Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(4), CD002892. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd002892.pub5

Ryali, V. S. R., Sreelatha, P., & Premlal, L. (2018). Burnout and coping strategies among residents of a private medical college in South India: A cross-sectional study. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 27(2), 213-218. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_53_18

Shanafelt, T. D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Dyrbye, L. N., Sotile, W., Satele, D., West, C. P., Sloan, J., & Oreskovich, M. R. (2012). Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(18), 1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

Smith, D. W. (2021). Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu.

Sum, M. Y., Chew, Q. H., & Sim, K. (2019). Perceptions of the learning environment on the relationship between stress and burnout for residents in an ACGME-I accredited national psychiatry residency program. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 11(4s), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-18-00795

Talih, F., Daher, M., Daou, D., & Ajaltouni, J. (2018). Examining burnout, depression, and attitudes regarding drug use among Lebanese medical students during the 4 years of medical school. Academic Psychiatry, 42(2), 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0879-x

Tan, M. Y., Ng, N. B. H., Aw, M. M., & Lin, J. B. (2022). Perceived stress & sentiments of housemen starting work during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Singapore. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 7(2), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2022-7-2/sc2686

Tuffour, I. (2017). A critical overview of interpretative phenomenological analysis: A contemporary qualitative research approach. Journal of Healthcare Communications, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1654.10009

Watson, A. G., Saggar, V., MacDowell, C., & McCoy, J. V. (2019). Self-reported modifying effects of resilience factors on perceptions of workload, patient outcomes, and burnout in physician-attendees of an international emergency medicine conference. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 24(10), 1220–1234. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1619785