Vertical integration of anatomy and women’s health: Cross campus blended learning

Submitted: 9 May 2022

Accepted: 11 October 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 89-92

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/CS2806

Vidya Kushare1,2, Bharti M K1, Narendra Pamidi1, Lakshmi Selvaratnam1, Arkendu Sen1 & Nisha Angela Dominic3

1Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine & Health Sciences (JCSMHS), Monash University, Malaysia; 2Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 3Clinical School Johor Bahru (CSJB), Monash University, Malaysia

I. INTRODUCTION

For safe practice of medicine, proficiency in anatomy is important. Anatomy is mainly taught in the pre-clinical years. Knowledge retention decreases over time and this will affect clinical and practical application during clinical years (Jurjus et al., 2014; Zumwalt et al., 2007). Literature shows that integrating relevant anatomy with clinical teaching will reinforce the basic concepts and fill these knowledge gaps. Rajan et al. (2016) in their study show that integrating neuroanatomy refresher sessions to clinical neurological case discussions was effective in building relevant knowledge.

Monash University practices a vertically integrated curriculum to promote meaningful learning. In a vertically integrated curriculum, clinical and basic sciences are integrated throughout the program, to provide relevance to basic sciences for clinical practice (Malik & Malik, 2010; Wijnen-Meijer et al., 2020).

As part of the clinical skills development, the Women’s Health (WH) team at Monash university Malaysia in 2010 started episiotomy workshops. Episiotomy is a procedural skill, as future doctors working in Malaysia are expected to know. To perform and repair this surgical procedure safely as well as to identify potential complications, an in-depth knowledge of perineal anatomy is essential.

In 2019, the Anatomy and WH team came together to integrate a refresher anatomy component to the ongoing episiotomy workshops. The objective was to reinforce anatomy relevant to the episiotomy procedure to promote meaningful and lifelong learning.

The anatomy component was integrated virtually because the clinical and preclinical campus are located at different sites about 300km apart. The preclinical Sunway campus is located at Bandar Sunway and the Clinical School Johor Bharu (CSJB) campus is located at Johor Bahru.

Our aim was to see if this approach of virtually integrating refresher anatomy components with the episiotomy workshops will be relevant and beneficial to student learning.

II. METHODS

This cross-campus, blended learning approach, a combination of online (anatomy review session) and face-to-face (episiotomy workshops) sessions, was started in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic. These integrated sessions were conducted for year 5 medical students during their O&G rotation with each group attending the session only once. The anatomy sessions were remotely conducted by the anatomy team. All practical hands-on training workshops were conducted in the clinical skills lab (CSJB campus) by the WH team for the students attending onsite. The two sites were connected via a web conferencing platform/ application (Zoom).

Before the pandemic, the online anatomy sessions and the hand-on workshops were conducted synchronously. The anatomy session was in the form of a 30-minute lecture demo-presentation using various models, cadaveric plastinated specimens and images. This lecture-demo was broadcast virtually from the Monash Anatomy and Pathology e-Learning (MAPEL) Lab in Sunway campus to the clinical skills lab at CSJB. This was followed by the practical training on performing and repairing episiotomy on mannequins supervised by the WH team (see Appendix A).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we altered the delivery format of the anatomy component due to the restrictions. The real time virtual anatomy demo-presentation was replaced by a pre-recorded video lecture uploaded to a Moodle learning management system for students to view asynchronously, before attending the workshop. During the workshop, a knowledge assessment quiz (using online polling application) was remotely conducted by the anatomy team. Each question was discussed in detail with explanation and feedback provided by both teams. This was followed by the practical, hands-on training for students attending onsite in the clinical skills lab at CSJB (see Appendix A).

At the end of the sessions, students responded to a voluntary, anonymised online survey questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of both quantitative questions based on 5-point Likert scale and qualitative open-ended questions.

III. RESULTS

In 2021, we conducted seven integrated workshops, with a total of 59 students attending. Thirty-two students (54%) responded to the survey questionnaire, out of whom the majority (87.5%) had either observed or assisted an episiotomy procedure on real patients. Based on their feedback, most students had viewed the pre-recorded video lectures and found them useful.

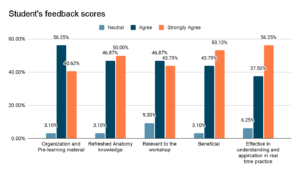

As shown in Figure 1 below, 96% agreed that organization and content of pre-learning materials were effective in achieving the learning outcomes, 96% agreed that this approach refreshed their anatomy knowledge, 91% felt that the anatomy sessions were relevant to the episiotomy workshop, 96% agreed that this approach of integrating anatomy was beneficial and 93% found that this approach was effective in their understanding and application in real time practice.

Figure 1. Student responses in evaluating impact (based on a 5-point Likert scale) of virtual integration of relevant anatomy in the episiotomy workshop

Qualitatively, the responses to open-ended questions were grouped as either most or least beneficial. Most beneficial to the students was that it helped them to revise and correlate relevant anatomy, consolidate and highlight the important concepts. Least beneficial to students were the non-clinical aspects, overlapping content between the uploaded lecture video and the real time zoom session, insufficient models and the lack of online engagement. Overall, the students responded positively towards this learning approach.

IV. DISCUSSION

Based on student feedback, more than 90% responded positively towards this virtual integrated approach of reviewing relevant anatomy during the hands-on workshop. This just-in-time’ review approach, even when conducted virtually, allows them to focus on applying only pertinent knowledge to the hands-on session and subsequently when dealing with real-time episiotomy repair on patients.

The limitations of the study include the internet network bandwidth at the two distant sites and the restrictions posed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Replacing the live anatomy demonstrations, time constraints, social distancing and the use of face shields/face masks made online interactions more challenging.

V. CONCLUSION

This is an ongoing project, requiring further evaluation to assess the impact of this pre-internship training strategy on key procedural skills learning and future practice that is expected in obstetrics.

To conclude, incorporating relevant, refresher anatomy sessions into clinical teaching, even when held virtually, can benefit students to review the core concepts of basic sciences and apply it to clinical practice. This allows for the development of clinical skill competency and ultimately safe patient care.

Notes on Contributors

Vidya Kushare initiated and designed the project, conducted the virtual anatomy review sessions, prepared the video, the quiz and the feedback questionnaire, performed the data collection and data analysis, wrote the manuscript and presented this in a conference.

Bharti M K was involved in the design of the project, conducted the virtual anatomy review sessions, prepared the video and edited the manuscript.

Narendra Pamidi was involved in the design of the project, editing the manuscript and providing references.

Lakshmi Selvaratnam was involved in the planning and development of the project, providing references, providing feedback, writing and editing the manuscript.

Arkendu Sen was involved in the design of the project, providing feedback, editing the manuscript and providing references.

Nisha Angela Dominic initiated and designed the project, conducted the hands-on workshop sessions, prepared the quiz and the feedback questionnaire, performed the data collection, editing the manuscript and providing references.

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the technical teams from both campuses: Mr Mah, Ms Nurul, Ms Zafrizal & Mr Abisina.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

Jurjus, R. A., Lee, J., Ahle, S., Brown, K. M., Butera, G., Goldman, E. F., & Krapf, J. M. (2014). Anatomical knowledge retention in third-year medical students prior to obstetrics and gynecology and surgery rotations. Anatomical Sciences Education, 7(6), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1441

Malik, A. S., & Malik, R. H. (2010). Twelve tips for developing an integrated curriculum. Medical Teacher, 33(2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.507711

Rajan, S. J., Jacob, T. M., & Sathyendra, S. (2016). Vertical integration of basic science in final year of medical education. International Journal of Applied & Basic Medical Research, 6(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516X.186958

Wijnen-Meijer, M., van den Broek, S., Koens, F., & ten Cate, O. (2020). Vertical integration in medical education: The broader perspective. BMC Medical Education, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02433-6

Zumwalt, A. C., Marks, L., & Halperin, E. C. (2007). Integrating gross anatomy into a clinical oncology curriculum: The oncoanatomy course at Duke University School of Medicine. Academic Medicine, 82(5), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31803ea96a

*Vidya Kushare

Jln Profesor Diraja Ungku Aziz,

50603 Kuala Lumpur,

Wilayah Persekutuan, Malaysia

+60162440142

Email: vidyakusharee@gmail.com / vidyakushare@um.edu.my

Submitted: 4 May 2022

Accepted: 16 August 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 86-88

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/SC2804

Sok Mui Lim1,2 & Chun Yi Lim2,3

1Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD), Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2 Health and Social Sciences, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 3Department of Child Development, KKH Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Interactive oral assessment has been identified as a form of authentic assessment that enables students to develop their professional identity, communications skills, and helps promote employability (Sotiriadou et al., 2020). It simulates authentic scenarios where assessors can engage students in genuine and unscripted interactions that represents workplace experiences (Sotiriadou et al., 2020). Unlike written examinations, interactive oral questions are not rigidly standardised as students and assessors role-play using workplace scenarios, enabling students to respond to the conversational flow and achieve authenticity (Tan et al., 2021). Using Villarroel et al. (2018) four-step ‘Model to Build Authentic Assessment’, this paper will present the use of oral interactive with first year occupational therapy students. This is within the context of a module named “Occupational Performance Across Lifespan” and students learn about children’s developmental milestones.

II. METHODS

The first step of the Model by Villarroel et al. (2018) is to consider the workplace context. It is important to identify key transferable skills that are needed at typical workplace scenarios. In the job of occupational therapists, they need to meet with caregivers and address their concerns. The key transferable skills include determining whether there is delay in a child’s developmental milestones, communicating with empathy and articulating practical suggestions for caregivers. Thinking critically and communicating persuasively and empathetically, especially in dynamic situations, are important graduate attributes for our students to prepare themselves for the clinical workforce.

The second step of the Model is to design authentic assessment, which involves (1) drafting a rich context; (2) creating a worthwhile task; and (3) requiring higher order skills. In our assessment, students were given a scenario and asked to discuss developmental milestones with parents, identify whether there were areas of concerns from what was reported and provide suggestions if appropriate.

To do this, we trained standardised “actors” / “parents” to share their concerns and correspond with the student individually. As the assessment took place during the pandemic, we used Zoom for corresponding, like therapists conducting teleconsultations. To promote employment opportunities, we included persons with disability as standardised parents. The students were unaware of the disability such as spinal cord injury, as it was conducted on an online platform. We followed the guide on inclusion of persons with disabilities as standardised patients (Lim et al., 2020). The academic staff took the role of the examiner and focused on listening in to the answers provided and writing down feedback for each student.

The third step involves developing the assessment criteria and standard in the form of rubrics and familiarising students with them. To prepare the students, five weeks before the actual assessment, we explained what oral interactive assessments were and introduced the rubrics. They watched videos of one high performing student and one who struggled from previous cohort (with permission sought). They discussed what went well and where the gaps were, followed by pairing up to practice. This helped the students to understand the expected standard, visualise how the oral interactive will take place and learn to evaluate. Three weeks before the assessment, students were given some mock scenarios to practice, and suggestions from the previous cohort on how best to prepare for the assessment.

The fourth step relates to feedback. Feedback can enable students to judge future performances and make improvements within the context of individual assessment. After the assessment, each student was given individual written feedback. The cohort was given group feedback on what they did well and some of the common mistakes. Students who needed more detailed feedback were also given the opportunity to be coached by the Module Lead. At coaching-feedback sessions, the student will watch their video, pause, coached on what they notice, what was done well, and how they can do differently in future. Such feedback sessions are viewed as a coachable moment for educators to develop students in their competency (Lim, 2021).

III. RESULTS

We conducted oral interactive assessments with persons with disability as standardised parents for two cohorts of students (n>200). From the anonymous module feedback, we learnt that students appreciated the assessment as it has real world relevance and enable them to gain professional skills. Some appreciated the opportunity to experience what it felt like interacting with caregivers at their future workplaces. We also noted some students expressed they were more anxious preparing for the oral interactive compared to other forms of assessments. Students shared that they prepared the assessment by remembering the developmental milestones and practise verbalising the concepts out loud with their peers.

IV. DISCUSSION

Students need time to be prepared for a new form of assessment as they may be more familiar with pen and paper examination or report. A few recommendations are suggested:

1) To reduce their anxiety, early preparation is important. Performance anxiety was a common stumbling block. Supporting students in learning strategies to manage performance anxiety can help.

2) For the assessment conversation to be natural, it is important to train the standardised actors on reactions for hit and missed responses from the students.

3) To maintain integrity of the assessment, different scenarios of similar level of difficulties were needed. Educators emphasised the value of learning from the assessment and individualised feedback, such that experience itself becomes intrinsically rewarding.

4) The educator plays the role of the examiner and concentrates to note down the quality of the answers and writes down feedback for each student.

5) Scaffolding students for continuous practice towards workplace competence is important. It is recommended to plan other authentic assessments in the later years of the curriculum such as OSCE.

V. CONCLUSION

Oral interactive assessment provides students with the opportunity to practice and be assessed on workplace competency. While students find themselves more anxious in preparing, they appreciate the real-world relevance and the opportunity to gain professional skills. It is worthwhile to spend effort in designing the assessment in detail, planning authentic scenarios, and preparing students for the experience. As an educator, it is rewarding to witness students developing the ability to demonstrate their competency in a professional manner.

Notes on Contributors

Associate Professor Lim Sok Mui (May) contributed to the conception, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Dr Lim Chun Yi contributed to the execution of the assessment, drafting and reviewing the manuscript.

All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the help of Mr Lim Li Siong, Dr Shamini d/o Logannathan and Miss Elisa Chong for their help in supporting the oral interactive assessments and Miss Hannah Goh for assisting to proofread this manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Lim, S. M. (2021, May 27). The answer is not always the solution: Using coaching in higher education. THE Campus Learn, Share, Connect. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/answer-not-always-solution-using-coaching-higher-education

Lim, S. M., Goh, Z. A. G., & Tan, B. L. (2020). Eight tips for inclusion of persons with disabilities as standardised patients. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 5(2), 41-44. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/SC2134

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., & Guest, R. (2020). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skill development and employability. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 2132–2148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Tan, C. P., Howes, D., Tan, R. K., & Dancza, K. M. (2021). Developing interactive oral assessments to foster graduate attributes in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.2020722

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., & Herrera-Seda, C. (2018). Authentic assessment: Creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5): 840–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

*May Lim Sok Mui

Singapore Institute of Technology,

10 Dover Drive,

Singapore 138683

+65 6592 1171

Email: may.lim@singaporetech.edu.sg

Submitted: 31 August 2022

Accepted: 27 September 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2022, 8(2), 83-85

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/PV2874

Janet Grant1,2

1Centre for Medical Education in Context (CenMEDIC), United Kingdom; 2University College London Medical School, United Kingdom

I. TO BEGIN WITH MY VIEW

Medical education is a social science which addresses how people learn and teach medicine. The practice of education and training is therefore fundamental to its epistemology, whereby knowledge, and so scholarship, derives from practice. Where that practice is subject to social, contextual and cultural factors, we must question whether the tenets that are put forward are generalisable beyond the context from which they were derived (Fendler & Cole, 2006). This lack of automatic generalisability has implications for both the scholarship of the medical educationalist, and for the relationship between medical educationalist and teacher. Where educational practice is primary, and is contextually informed, then the teacher, the practitioner of medical education, must be the leader in developing scholarship, while the medical educationalist can support that development by enabling each teacher, context or culture, to tell their own truth well (Grant & Grant, 2022).

II. WHY IS THIS MY VIEW?

A. Scholarship and the Primacy of Practice

The term ‘scholarship’ implies special knowledge that is derived from research or academic analysis. While we can argue that learning has a research basis in educational and cognitive psychology, the same cannot be said of teaching. We can think, for example, of the churn of new teaching methods (sometimes erroneously presented as new ideas about learning) that sweep into medical education, find little evidence of consistent effect, and fade into the ever-expanding menu of teaching options. We can think of problem-based, task-based, case-based, resource-based, peer-assisted, blended, team-based, and e-learning, the flipped classroom, and more broadly, active learning and learner-centred learning. And there are more, changing with fashion and social values.

Are these changes based on generalisable knowledge derived from robust research? Although there might be published papers, they rarely constitute a consistent body of scholarly knowledge that enables claims about predictable effects of different teaching methods in different contexts. That is the nature of social science (Fendler & Cole, 2006). It is this lack of generalisability of the social practice of teaching that places the epistemology of medical education not in theories or fashion, but in widely variable, and contextually tailored, practice.

Although the practice of teaching is socially bound, we can say that the fundamental cognitive basis of learning, how knowledge is effectively organised in memory and accessed when needed, is the same for everyone. Knowing that short-term, working memory should not be overloaded, and that long-term memory should be well-organised with structured, generalisable and accessible knowledge, is the simple baseline against which a medical educationalist can ensure that teaching and learning methods are designed and judged. Many which demand complex processes (sometimes termed ‘learner-centred’) would fail that test.

There is a parallel literature demonstrating that the social, personal and interpersonal processes that cause knowledge to be stored and used effectively, and motor and cognitive skills to develop, are different depending on culture, content and context. Teaching that seems applicable and relevant in one cultural or content context may not apply in another. So it seems important to begin from practice, observe successes and problems, and build theories, if that seems helpful.

These uncertainties underpin our practice-based epistemology, where the teacher is the key person. Accordingly, we have argued (Grant & Grant, 2022) that medical education is not an academic discipline at all, but is an examination of instrumental practice, trying to relate educational activities to purposes, making its means relate to its ends, and making decisions about that on the basis of context and judgement.

This view places the teacher at the heart and in the vanguard of relevant medical education development. This is social science where generalisable scholarship in teaching is difficult to attain. So, there is an ethical responsibility borne by those who claim to know what effective teaching is.

This leads to the next question.

B. What might be the Relationship Between the Teacher and the Medical Educationalist?

Definitionally, I take a medical educationalist to be someone who claims special expertise by virtue of, for example, having completed a Master’s degree in health professions education. Some teachers have done this too, but most have not. Teachers, here, are the subject specialists who actively help others to acquire necessary knowledge and skill.

What might be the relationship between these two?

To answer this, we turn to Lawrence Stenhouse, a British educational thinker who sought to promote an active role for teachers in educational research and curriculum development. Stenhouse argued that the teacher might lead quality development, becoming an ‘extended professional’, supported by trained technical expertise: ‘It is not enough that teachers’ work should be studied: they need to study it themselves’ (Stenhouse, 1976, p143).

In this endeavour, the medical education specialist is a resource, knowing the theories and fashions, and their critiques, summarising where there is and is not evidence, guiding analysis, offering options in relation to the teacher’s practice. The teacher is an equal partner in this ‘mutually supportive co-operative research’ (Stenhouse, 1976, p159), learning to be a researcher, simply because knowledge comes from and is tested in its performance. The medical educationalist will be a crucial support in this process.

To hold this supporting role demands being critically informed about medical education theory and practice. Medical education seems replete with largely unexamined terms such as ‘adult learning’, ‘learner-centred’ or the oxymoronic ‘passive learning’; or with handy mnemonics, and frameworks that have ever-decreasing academic credibility such as ’learning styles’. Medical educationalists must be more securely rooted in the critical approach of social science, beyond the constantly metamorphosing rhetoric of medical education. That authenticity will be gained in equal partnership with teachers.

Stenhouse’s position is unequivocal: the expert is the teacher, the practitioner who understands the individual context. The ‘teacher as researcher’ was Stenhouse’s ground-breaking view of the basis of rational educational development (Stenhouse, 1976, pp. 142-165).

How different is the implication of this view of the teacher, not as a person to be studied or developed, but the person who should be the scholar, reaching, and sharing, their own conclusions in their own classroom. Agency then belongs to the teacher who enacts the curriculum.

In this model, the role of the medical education specialist is to provide knowledge of developmental potential, and of how to develop practice-based, contextual scholarship around methods of reflective action research, perhaps. The medical educationalist is no longer the primary source of knowledge, or the impartial researcher, but is the means of supporting authentic practice development, helping each teacher to find their own truth.

C. And What of the Scholarship of Teaching?

The literature on the scholarship of teaching addresses its derivation in research and reflection on practice, and its use in theory building and educational development. In that literature, the meaning of scholarship in relation to actual teaching is ill-defined.

The importance of this for medical education is that scholarship can easily be thought of as the domain of those who have taken medical education as their speciality, rather than the domain of the teacher who is primarily a scientist or a clinician. This creates a particular relationship where ideas such as ‘faculty development’ suggest that the scholarship of teaching is garnered elsewhere and then shared with the teacher.

But I have argued that the scholarship of teaching will come from the experience of the teachers. Others argued, before me, that knowledge comes from social practice, and then returns to serve and enhance that practice (Mao, 1937). In that, there must be a mechanism for gathering that knowledge derived from social practice and returning it to practice. This may be the role of the medical educationalist, or of medical educationalists collectively, pooling their knowledge gained through working with teachers, reflecting their experience.

This role of gathering together knowledge generated in practice, is especially important in these days when the controversial idea of ‘globalisation of education’ often passes without critique. But ‘Globalisation initiatives must be tempered by ‘cultural humility’ in recognition of the likelihood that, rather than there being one exclusive, universal and ‘superior’ model, there may be many models of effective teaching and learning in medical education around the world’ (Wong, 2011, p. 1218). For Wong, in opposition to the neo-institutionalist, perhaps neo-colonialist, view, ‘…the culturalist perspective focuses on the enduring ability of different cultures and ways of knowing to re-interpret, transform and hybridise education practices to best suit local context’ (Wong, 2011, p. 2010).

This view recognises those contextual imperatives: scholarship must derive from the domain of the teacher, supported, not driven, by the medical education specialist. This is true both of ideas on teaching methods, and of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks that shine and fade in parallel.

In this view, the teacher would become an extended professional who has ‘a capacity for autonomous professional self-development through a systematic self-study, through the study of the work of other teachers and through the testing of ideas by classroom research procedures’ (Stenhouse, 1976, p. 144). In other words, scholarship reverts to the teacher. Support for that scholarship belongs to the medical education specialist, working by the practitioner’s side, in the classroom, enabling that person to advance the contextual practice of medical education.

Note on Contributor

Janet Grant wrote the script, discussed it with Leo Grant and Professor Ahmed Rashid, and wrote the final version.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Leo Grant of CenMEDIC, London, and Professor Ahmed Rashid, of University College London Medical School, for their comments on this paper which helped me to express my personal view so much better than I could have done by myself.

Funding

There was no funding support accorded for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Fendler, L., & Cole, J. (2006). Why Generalisability is not Generalisable. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 40(4), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2006.00520.x

Grant, J., & Grant, L. (2022). Quality and constructed knowledge: Truth, paradigms, and the state of the science. Medical Education. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14871

Mao, Z. (1937). On Practice. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-1/mswv1_16.htm

Stenhouse, L. (1976). An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. Heinemann.

Wong, A. K. (2011). Culture in medical education: Comparing a Thai and a Canadian residency programme. Medical Education, 45(12), 1209–1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04059.x

*Janet Grant

27 Church Street,

Hampton, Middlesex

TW12 2EB,

United Kingdom

Email: janet@cenmedic.net

Submitted: 15 July 2022

Accepted: 21 September 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 80-82

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/PV2842

Kevin Tan1,2, Yang Yann Foo2 & Nigel Choon Kiat Tan1,2

1Office of Neurological Education, Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore; 2Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

A program director of a one-year-old Singapore surgical residency programme reads a publication about a new model of feedback. The paper describes how a US medical school successfully trialled and implemented this new feedback model. Excited, she then tries to implement this new model in her residency programme. Unfortunately, this fails to change faculty and resident behaviour, with disgruntled faculty and residents, and poor take-up by the various surgical departments within her programme. Disappointed, she stops using the new feedback model after a year.

What happened? Why would an educational intervention about feedback, published as part of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) (Steinert, 2017), and successfully implemented in a US medical school, fail to take root in a Singapore surgical residency programme? Might failure to consider context have contributed? A review of the publication showed that while descriptions of the feedback model and the educational outcomes were rich, descriptions of the medical school environment and the broader educational context of the US were sparse.

Might a richer description of context in the publication have helped readers understand the social and educational milieu from which the novel feedback model developed? And with that understanding of context, might a subsequent analysis of contextual differences between the publication and the residency programme’s dissimilar contexts have helped avoid this education setback? Fundamentally, did the lack of contextual descriptions lead to a myopic view of the educational intervention?

Let’s first examine SoTL, which is defined as “the description and dissemination of effective and novel teaching methods and strategies, in a research presentation or publication” (Steinert, 2017). While standards for SoTL in health professions education (HPE) have been proposed (Glassick, 2000), including the need to describe goals, preparation, methods and results, there is scant mention of the need to describe the context within which the novel methods or strategies were operationalised or implemented. So while SoTL remains effective for disseminating novel teaching methods, the variable extent to which context is described (Bates & Ellaway, 2016) may result in challenges in implementing such methods in a different environment; key contextual enablers for successful implementation may have been inadequately described within the HPE SoTL literature. In contrast, the general education literature has long been aware of the importance of context in SoTL (Felten, 2013). There is therefore a blind spot in the HPE SoTL literature.

We next examine context. While we highlight rich descriptions of context for the value it brings to SoTL, we pause to reflect: how do we define context? Context can be difficult to define. A scoping review (Bates & Ellaway, 2016) concluded that one perspective was context as a “surrounding”, much like the layers of an onion, with a particular context playing a role as a mechanism influencing education outcomes. Employing these twin perspectives of “context as an environment surrounding an education activity”, and “context as a mechanism” (Bates & Ellaway, 2016) influencing said activity, we can then view context as surrounding and influencing the educational method, its implementation and its outcomes.

Given the many elements within the context that may influence outcomes, how do we then systematically identify and dissect these disparate elements? The analogy of an onion with surrounding layers (Bates & Ellaway, 2016) led us to consider Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems theory (EST) (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). In EST, multiple systems (micro-, meso-, exo-, macro- and chrono-), much like layers of an onion, influence an individual’s learning. EST can be used to identify, dissect, and categorise contextual influences, and determine if they enable or inhibit educational activities.

In our scenario, the original SoTL work did not fully describe the context. Let us now imagine that the situation was clarified by us writing to the authors to learn more about their context. We are then rewarded with a rich, three-page description of their context. Using EST to dissect the differences between the US context of the intervention, versus the Singapore context of the residency programme, we now realise there were differences at multiple EST system levels, for example:

- Microsystem: medical students vs residents as learners and feedback recipients, university faculty vs clinician faculty as feedback providers

- Mesosystem: uniprofessional vs multiprofessional peers and colleagues, undergraduate vs postgraduate curricula

- Exosystem: university vs clinical training environment, academic workload vs clinical workload

- Macrosystem: cultures of medical school vs residency, cultures of university vs medical profession, societal cultures of the US vs Singapore

- Chronosystem: historical perceptions of feedback and utility of feedback in the US vs Singapore

With these different EST system levels in mind, one can identify enablers and inhibitors to successful implementation of the published feedback model in Singapore:

- Microsystem: residents and/or clinician faculty may be busy or distracted by concurrent clinical duties, thus less willing or able to deliver actionable feedback using the model, vs university lecturers who had dedicated time for feedback sessions

- Mesosystem: while feedback was institutionalised in the US medical school as a longitudinal aspect of the curriculum since 10 years ago, allowing easier integration of a new model into a mature curricular element, adding a new feedback model into a one-year-old programme’s curriculum and implementing it added more stress to a new programme still in flux

- Exosystem: the US medical school had several resources that the local programme did not. The American researchers had many dedicated teaching rooms for feedback provision to the medical students. In contrast, the surgical residents had to compete with other residents and users for fewer rooms in the local hospital that were also used for multiple clinical, administrative and research purposes. The university also had a mature e-portfolio system where faculty and students could review goals, milestones and progress to facilitate feedback provision, while the new residency programme did not.

- Macrosystem: feedback was viewed positively by university faculty and students as a key learning activity, with the school taking pride in providing actionable feedback as part of its culture and values. The school’s Dean also publicly affirmed support for the new feedback model. In contrast, the new residency faculty were still unused to providing structured feedback, or inviting reflection as part of feedback; some even viewed feedback as a chore rather than as a vehicle for learning and improvement. The nascent feedback culture of the residency faculty had not fully taken root yet, unlike in the US school.

- Chronosystem: Historical perceptions of feedback differed in the US vs Singapore, with feedback considered valuable for learning and improvement in the US. In Singapore however, feedback was viewed by some senior surgical faculty members as being useful only when mistakes were made by residents, whereupon forceful negative feedback was given by faculty to the resident in the name of patient safety, rather than for learning. These views from the local senior faculty were informed by their prior experiences as trainees in earlier training systems, leading to their rejection of the new feedback model as being “soft” and compromising patient safety.

With a rich description of context, and using EST as a tool, one can now see how the different system layers surround and envelope the faculty, residents and their feedback interaction. One can also see how contextual differences in these system layers (in the US vs Singapore) influenced the success or failure in implementation of the new feedback model. If rich contextual information was provided in the SoTL literature at the start then this information, considered with EST, might have helped the residency programme director avoid the implementation failure.

Successful understanding and application of SoTL in HPE thus relies not only on the six goals espoused by Glassick (Glassick, 2000), but also requires adequate descriptions of context. Readers can then understand contextual differences, use EST to compare and contrast it to their context, identify differences at various EST system layers and determine the potential influence of these differences.

Conversely, the general education literature emphasises that SoTL should be “grounded in context” (Felten, 2013). Felten explicitly states “… all SoTL is rooted in particular classroom, disciplinary, institutional, and cultural contexts” and that “any measure of good practice must account for both the scholarly and the local context where that work is being done” (Felten, 2013). The primacy of context is stated, clearly and unambiguously.

In summary, while we have made progress in SoTL in HPE, we have not adequately considered context in our SoTL guidance (Glassick, 2000) compared to our general education colleagues (Felten, 2013). This underemphasis on context may result in sparse descriptions of context in the HPE SoTL literature, leading HPE readers to be myopic and failing to see the myriad contextual influences affecting understanding and translation of the described SoTL methods to the reader’s context. If we had richer descriptions of context in the SoTL literature, however, we can then use the ‘context lenses’ to clearly view the surrounding layers that influence education outcomes (Bates & Ellaway, 2016). Finally, with visual clarity, we can then dissect and analyse these layers via mapping them to systems levels using EST (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), so that effective translation and implementation of the described SoTL methods can take place. It is time to correct our myopia by collectively advocating for the rich descriptions of context in our HPE SoTL literature.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Kevin Tan reviewed the literature and developed the manuscript. Dr Foo Yang Yann reviewed the literature and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript. Dr Nigel Choon Kiat Tan reviewed the literature and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interest, including financial, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

References

Bates, J., & Ellaway, R. H. (2016). Mapping the dark matter of context: A conceptual scoping review. Medical Education, 50(8), 807-816. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13034

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723-742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.2 2.6.723

Felten, P. (2013). Principles of Good Practice in SoTL. Teaching & Learning Inquiry: The ISSOTL Journal, 1(1), 121-125. https://doi.org/10.2979/teachlearninqu.1.1.121

Glassick, C. E. (2000). Boyerʼs expanded definitions of scholarship, the standards for assessing scholarship, and the elusiveness of the scholarship of teaching. Academic Medicine, 75(9), 877-880. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200009000-00007

Steinert, Y. (2017). Scholarship in medical education. International Journal of Education and Health, 1(1), 3-4. https://doi.org/10.17267/2594-7907ijhe.v1i1.1657

*Kevin Tan

Office of Neurological Education,

Department of Neurology,

National Neuroscience Institute

11 Jalan Tan Tock Seng,

Singapore 308433

Email: kevin.tan@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 5 August 2022

Accepted: 2 November 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 76-79

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/SC2861

Poh-Sun Goh1 & Elisabeth Frieda Maria Schlegel2

1Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Science Education, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hofstra University, United States

Abstract

Introduction: The aim of this short communication is to examine the journey of scholarship in health professions education (HPE).

Methods: We will focus on tangible small steps to start, sustain, and succeed along this journey. Through a proposed innovation in scholarship – micro-scholarship – we will describe how this is similar to and an extension of bite-size or micro-learning, and workplace micro-practice related to just-in-time (JiT) learning settings.

Results: We will demonstrate how the small steps for generating and engaging with micro-content can be similarly applied to micro-scholarship. Then, progressive and iterative refinement of output and practice of micro-scholarship can be combined and result in macro-scholarship after cycles of public engagement for final digital or print publication. This stepwise approach creates an accessible, sustainable strategy to achieve success as a scholar in HPE. We will elaborate on micro, macro, and meta matters and celebrate how these small steps encourage and allow broad participation in the creation, critique, and progressive refinement of scholarship.

Conclusion: Small, sustainable, steps leads to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Keywords: Micro-Scholarship, Micro-Learning, Just-In-Time (JiT) Learning, Community of Practice (CoP), Technology, Network Effects, Post-Publication Peer Review (PPPR)

I. INTRODUCTION

Modern changes in the pace and way we conduct and experience teaching and learning have resulted in production and consumption of smaller chunks of content. Succinct, bite-size content is easier to remember and consumes less cognitive bandwidth with reduced cognitive load. In addition, it is also significantly easier to share and engage with within a professional community of practice (CoP). Compact modular, bite-size content is also ideal for just-in-time (JiT) micro-learning and workplace micro-practice (Yilmaz et al., 2022), or on-demand learning and practice, with which we are all familiar. In this paper, we will extend this idea of micro-learning and micro-practice to scholarship, by examining the “new” idea of micro-scholarship – defined as “the process of making visible the smallest accessible and assessable steps that document a scholarly journey, which can then be assembled and presented as an outcome of academic scholarship” (Goh et al., 2021). Mobile technology tools and platforms support open display, access to, and iterative engagement with this content by a community of practice (CoP), both in learning and scholarship (Goh et al., 2021; Goh & Sandars, 2020; Schlegel, 2021).

II. MICRO-MATTERS

Just as a musical composition is made up of individual notes, a construction from its individual parts, and a meal of its individual ingredients, commonly accepted and acknowledged finished works of scholarship in HPE are composed of its individual parts. A conference presentation or journal paper, peer reviewed, read by and engaged with by a CoP, contains core components – e.g., the title (which includes key ideas); key words (which are defined and illustrated in the presentation or paper); and cited published work by earlier authors (from a review of the field, including takeaways from the author(s) that are relevant and that the authors intend to discuss, elaborate, and build upon). However, a close examination and reflection of these core parts of finished works of scholarship show that they not only form the ingredients of the final work, but that they also fall within the categories of scholarship proposed by Boyer, with evaluation criteria described by Hutchings and Shulman; (Goh et al., 2021; Goh & Sandars, 2020). Boyer’s model for scholarship includes (1) integration, (2) application, (3) teaching and learning, and (4) discovery.

Innovative JiT micro-content on mobile platforms is easily accessible for members of a CoP to engage with, evaluate, critique, and build upon. All online content, including, e.g., on Twitter, blogs, or modular courses, is subject to creative reader collectives, which post comments, repost, reshare, and create new meaning and value from individual posts of content, contributing to group engagement, which has many of the characteristics of scholarship (Schlegel & Primacio, 2021). We propose that these artefacts and activities illustrate examples of Boyer’s Scholarship categories, including demonstrating the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning SoTL. Digital and online content and platforms support and scale our efforts as learners and scholars, no different yet more facile as compared to in-person activities, with increased importance placed on being a public professional, and respecting intellectual property, shown by proper citation of digital content, and use of this content with permission where applicable, followed by data-driven dissemination (Arrington & Cohen, 2015; Kern et al., 2015). This public reaction and appraisal of content compares to wide audience post-publication peer review (PPPR) with the added value of a feedback-loop through responses on comments. Just as developing bite-size, short format, JiT digital, online content, has transformed and continues to transform our educational and professional practices, a similar process can now facilitate and support granular, open digital display and engagement of both our initial and subsequent steps when engaging in scholarship in HPE, similar to and an extension of micro-learning. Practicing micro-scholarship involves encountering a “new idea”; researching its meaning; adding relevance to specific discussion themes and takeaways; discovering key published and presented work; and then both taking note of and making notes on these findings during reflection and discussions within a local CoP. This micro-scholarship is subsequently made open and visible to a global readership or a CoP, through private, semi-private, and public engagement platforms. Micro-scholarship content gets progressively refined through iterative engagement with members of a CoP, through discussion, feedback, critique, and personal reflection. The relevance and usefulness of this content, as well as confidence in the authors of this micro- scholarship content, is progressively enhanced. We also learn how and where this content is best disseminated and presented, and best ways this might be combined and stacked. The iterative in- person and scalable digital conversations amplifying the spread and engagement with this material to create meaning, in step-by-step fashion, form the core practices of both micro-scholarship (Goh et al., 2021) and bite-size engagement with material (Schlegel, 2021). After refinement, these pieces can be combined into larger pieces of finished work of macro-scholarship. Thus, activities undertaken as part of micro-learning or micro-scholarship are accessible, independent, and sustainable small, step-wise efforts that can and do add-up. Progression along the developmental path of a scholar will include a variety of conversations within a CoP, such as the supportive networks of peers, senior practitioners, mentors and coaches, including collaborative (team)work and initially supervised instruction as part of a successful scholar’s journey. Conversations and engagement within a CoP do range from positive and helpful to (those that are or perceived to be) occasionally provocative and challenging. However, professional and good-natured discussion generally guide scholarly development similar to trial and error, and progressive improvement and iterative steps enable learning and growth.

III. MACRO-MATTERS

Simply put, a finished larger work is made up small pieces that have been selected and refined, through an iterative process of reflection and feedback, by engaging with a CoP or specialised collective of readers. Open (digital) practice from an early stage, the platforms (places and readers) we engage in, and our active participation in professional CoP of global specialised readers provide both “informed” and “critical” feedback – and review of these “early” and “small” or “micro” pieces of work – from a (much wider) audience. The key distinction is who engages with this work, from as wide a spectrum of professional practice, experience, and expertise as possible, and from a diversity of points of view. Digital tools and practices facilitate and scale this process. This is similar to the work of artists, who engage in open sketching, including showcasing early drafts and ideas, prototyping, drawing, and artistic creation in open studios. When members of a CoP engage through digital platforms the impact from their individual and collective input can scale exponentially through network effects (Azhar, 2021).

IV. META-MATTERS

The process of scholarship mirrors the stepwise, sequential, cumulative process of learning, and training for proficiency and mastery in any area of practice. Our roles as practitioners, educators and scholars are all informed by learning science. Digital devices, tools, platforms, and practices exponentially scale up the impact of our efforts through applied network theory and interactions. Ultimately, we live and practice professionally within our CoP, which provides both the audience and peer reviewers of our public work, thus driving a fruitful evolution of our profession. Our ultimate aim is to engage a CoP in conversations, including broader participation in the production, refinement, and consumption of products of scholarship, in form and format, and through processes accessible for all. Micro-scholarship is a starting point that allows wider participation and engagement in the process of scholarship. The components of micro-scholarship, when refined and confidently presented, are contained within published finished macro-scholarship outputs. Then, micro-scholarship and macro-scholarship add collaboration and value within a larger scholarship ecosystem and professional CoP, a meta-level practice or meta-system, within which micro- and macro- level activities occur. An explicit example of the outputs and process of moving from micro, through macro, to meta practice illustrated https://www.slideshare.net/dnrgohps/illustrated-stacked-microscholarship-steps-along-academic-path-of-educational-scholar.

Another example of enhancing scholarship of teaching and learning SoTL across different levels might include, e.g. a remote consultation with members of scholarly project teams, prompting to publish a themed blog post, which, in return, becomes now a generalizable, transferrable offering to the global CoP, moving from the meta-system to the macro-level, as evidenced by comments from different institutions and subsequent implementation of ideas (Arrington & Cohen, 2015).

V. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we have examined, showcased, and celebrated the small sustainable steps to success as a scholar in HPE, describing micro, macro, and meta matters and illustrating how combining small components of scholarship is an effective strategy for dissemination, access, engagement, conversation and collaboration within a CoP in HPE.

Notes on Contributors

Poh-Sun Goh pitched initial idea, was involved in active discussion and brainstormed with co-author iterative refinement of core message(s), wrote first draft, and actively revised series of subsequent drafts, and submitted final draft. This manuscript built on previous collaborative work, cited in article on Micro-Scholarship and Digital Scholarship.

Elisabeth Schlegel was involved in active discussion and brainstormed with co-author iterative refinement of core message(s), and actively revised series of subsequent drafts, and including and approving final draft. This manuscript built on previous work, cited in article including on bite-sized learning.

Ethical Approval

As this manuscript is a description of an innovative approach to scholarship, ethical approval and IRB application was not required.

Data Availability

There is no additional data separate from available in cited references.

Acknowledgement

No technical help and/or financial and material support or contributions was received in preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Both authors have no funding source to declare.

Declaration of Interest

Both authors declare that there are no possible conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Arrington, N. M., & Cohen, A. L. (2015). Enhancing scholarship of teaching and learning through micro-level collaboration across two disciplines. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 27(2), 194.

Azhar, A. (2021). The exponential age: How accelerating technology is transforming business, politics and society. Diversion Books.

Goh, P. S., Roberts-Lieb, S., & Sandars, J. (2021). Definition of Micro-Scholarship. https://microscholarship.blogspot.com/

Goh, P. S., & Sandars, J. (2020). Rethinking scholarship in medical education during the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish, 9(97). https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000097.1

Kern, B., Mettetal, G., Dixson, M., & Morgan, R. K. (2015). The role of SoTL in the academy: Upon the 25th anniversary of Boyer’s scholarship reconsidered. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 15(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v15i3.13623

Schlegel, E. (2021). (Not only) for medical students: Get involved in medical education research & scholarship. https://elisabeth-fm-schlegel.weebly.com/elearning-bites/not-only-for-medical-students-get-involved-in-medical-education-research-scholarship

Schlegel, E., & Primacio, J. (2021). Blogging for the continuum of medical education: Engaging diverse communities of learners. MedEdPublish, 10, Article 136. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2021.000136.1

Yilmaz, Y., Papanagnou, D., Fornari, A., & Chan, T. M. (2022). The learning loop: Conceptualizing Just-in-Time faculty development. AEM Education and Training, 6(1), e10722. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10722

*Poh-Sun Goh

Department of Diagnostic Radiology

National University Hospital,

Main Building, Lobby F, Level 4

#04-398, DDI Library

5 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119074

+6567724211

Email: dnrgohps@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 28 April 2022

Accepted: 19 August 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 70-75

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/SC2802

Sok Mui Lim, Ramesh Shahdadpuri & Ching Yee Pua

Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD), Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Coaching has gained acceptance in the education field as a way to enable learners to achieve their fullest potential. In the endeavor to set up a coaching ecosystem in our university, we started by equipping our educators with fundamental coaching skills and techniques. Our training workshop, Coaching As An SIT Educator, covers the key coaching competencies and is highly practice focused. Participants get hands-on skills practice using contextualised scenarios that are based on realistic academic, workplace and clinical placement settings.

Methods: To address concerns on time-effectiveness, we adopt a solution-focused approach to coaching. We want to create a mindset shift for educators, from subject experts providing advice and solutions, to coaches asking powerful coaching questions that help students make discoveries and work towards their goals. We encourage our educators to engage students holistically by finding coachable moments in their daily student interactions.

Results: Competency-based assessments are conducted to determine achievement of the learning outcomes, articulated by the knowledge, attitude, and demonstration of coaching skills with students. Assessments consist of a reflection, multiple-choice question (MCQ) quiz, and scenario-based coaching role plays. Participants achieved the learning outcomes as demonstrated from the assessments.

Conclusion: The coach training workshop is the major pillar of our coaching initiative. Beyond the workshop, ongoing coaching development is supported through other activities and resources, including community of practice, coaching circle and knowledge repository. Opportunities for continuous learning and conversation platforms for sharing coaching experiences are part of the growing coaching ecosystem at SIT.

Keywords: Assessments, Coaching Competencies, Coaching Conversations, Coaching Ecosystem, Coachable Moments, Faculty Development, Feedback, Holistic Development, Solution-Focused

I. INTRODUCTION

Coaching has gained greater awareness and wider acceptance in the education field in the past decade, led by the efforts of innovative educators and more evidence-based research. Coaching has been described as a very powerful approach that facilitates personal and professional change through deep level listening, questioning, setting the right challenges and providing support along the process (Griffiths, 2005). More specifically, academic coaching is defined as individualised practice of asking students reflective, motivation-based questions, providing opportunities for formal self-assessment, sharing effective strategies, and co-creating a tangible plan that promotes accountability (Deiorio et al., 2017).

In traditional educational settings, communication tends to be mostly directive, where the educator is the subject expert who gives instructions, solutions or advice to students. From this “telling” or “pushing” stance where the focus is on problem solving and advice giving, shifting to coaching conversations requires an “asking” or “pulling” communication approach. Engaging in coaching conversations involves the educator coaching students through powerful questioning, active listening and guiding them to explore possibilities so as to discover new ideas and find solutions for themselves.

In 2020, Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) introduced internal coach training for all academic staff with the aim to build educators’ capability to work with students at a deeper level. This highly contextualised academic coaching training was made mandatory for all educators. This was essential for the creation of a strong coaching ecosystem in the university and adopting coaching practices across a variety of learning contexts, such as providing assignment feedback, consultations on projects and supervising students at the workplace. In working with students towards their preferred futures, SIT educators can help the students develop confidence and self-efficacy, enabling them to achieve their fullest potential.

II. METHODS

This section highlights the critical elements of the faculty development programme.

A. Solution-focused Approach

One of the top concerns of many educators is time. There are underlying concerns on whether coaching students will take up too much time, and what happens if they uncover student issues that they cannot deal with. A solution-focused coaching approach alleviates some of these concerns. The basic principle of the solution-focused approach is to help coachees reflect and design their solutions, rather than go down the path of root cause analysis. Its forward-oriented solution approach contrasts with other traditional psychological techniques, which tend to look back at the past or are problem-focused (Grant & Gerrard, 2020).

The solution-focused approach is known for its simplicity, attention to language and time effectiveness. The conversation is steered to a preferred future of the issue at hand without dwelling on the troubled past. The coach encourages the coachee to focus on their strengths and positive resources, to think about their resourceful past, and to draw on positive lessons from when they have been at their best. After identifying their desired outcomes and considering their options in the context of present realities, the coach guides the coachee to think about the next steps to progress towards their preferred future.

B. Mindset Shift

In higher education, many coachable opportunities outside the formal contact hours can be easily missed. For example, instead of merely deducting marks for repeated late submissions of assignments, the educator could coach the student on improving time management. In clinical fieldwork, when a student complains about limited interaction with the busy clinical educator, the university supervisor can coach the student on how best to schedule time for feedback. Our daily encounters and interactions with students present many coachable moments that offer just-in-time and authentic learning opportunities to support students in their development to become work-ready graduates.

Students may initially find coaching sessions difficult as it is easier to just ask for solutions than to discover solutions for oneself. However, with time, students will realise the value of coaching as they witness their progress. In an Asian context, where many students are respectful and value advice from authoritative figures, such as professors, coaching can require a mindset shift for both students and faculty (Lim, 2021).

C. Tailoring the Coaching Training to Education Context

The Coaching As An SIT Educator workshop is an in-house designed 2-day program. It is highly contextualised for the needs of SIT academic staff, to equip them to be versatile and agile educators, performing the role of Teacher-Coach-Mentor. The workshop covers the key coaching fundamentals and is highly practice-oriented. The programme design was intended for participants to develop hands-on coaching skills with contextualised role play scenarios (see Appendix A for an example), so that they can apply what they have learnt with their students immediately after the workshop.

While we do not intend to train credentialed professional coaches, the key International Coaching Federation (ICF) coaching competencies were referenced to guide the design of the SIT workshop. The GROW model (Whitmore, 2019) was introduced as a framework for the participants to organise and manage the flow of the coaching conversation. Drawing on inputs from academic staff, realistic student-centric scenarios were created for class discussions and role plays. The coaching practice sessions are conducted in dyad, triad, and hot seat formats. The workshop design and facilitation ensure that there is psychological safety, providing a trusting space for constructive debriefing, feedback sharing and open questions and answers to take place.

To manage the workshop time and resources effectively, e-learning content was developed in-house, specifically to complement the interactive classroom session. A week before the start of the workshop, the participants can access materials in the form of an asynchronous pre-recorded webinar. The webinar consists of five micromodules, covering topics such as Mindset, Motivation, Emotional Intelligence, and Feedback Skills (refer to Appendix B for more details). As many participants may already be familiar with these topics, this self-learning component serves as a good refresher to prepare participants for the coaching workshop.

Please refer to Table 1 for details of the Coaching as An SIT Educator workshop.

|

Workshop: Coaching As An SIT Educator |

|

|

Learning Outcomes By the end of this course, participants will be able to:

|

|

|

Topics Covered |

|

|

Pre-Workshop: eLearning

|

Workshop Day 1:

Workshop Day 2:

|

|

Assessments (Day 2) |

|

|

Role Plays: Standardised Students & Assessors Scenarios (each – 20 minutes):

|

Quiz: Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs)

|

Table 1. Coaching As An SIT Educator Workshop

III. EVALUATION OF COACHING COMPETENCY

To assess the attainment of the learning outcomes and development of the participants’ coaching competence (knowledge, skills, attitude), assessments and reflection exercises are incorporated into the workshop. As this is not a certification program, assessments are formative in nature, with focus on providing the educators quality feedback. Coaching knowledge is assessed through a multiple-choice question (MCQ) quiz. Attitude and mindset shift is evaluated through pre- and post- workshop surveys, and reflection questions.

Coaching skills are assessed via role plays (with standardised students). The role play format involves two 20-minute coaching sessions with the participant (playing the role of an educator) having a coaching conversation with standardised students (who act as coachees) and are conducted virtually in real time over the Zoom platform, using breakout rooms. The role plays that are based on common scenarios in university and workplace supervision settings. An invaluable part of the learning in this assessment comes from the feedback conversation between the participant (coach) and assessor, who observes the coaching conversation. Many participants regard the skills assessment and individualised feedback on their coaching skills as the highlight of the training programme.

IV. DISCUSSION

Many readily available coaching materials or vendor-run workshops are geared towards executive or corporate scenarios. While the skills of coaching may be transferable, it is difficult for educators to draw relevance to student engagement. Therefore, Coaching As An SIT Educator workshop focuses on case studies of university scenarios, and supervision for work-integrated learning (e.g., internship, clinical placement). Participants get to work with fellow learners in group work and discussions, to engage in personal reflection, and takeaway practical knowledge and skills on their learnings in a safe space.

For a sustained effort to practice coaching and build an on-going coaching culture, a mandatory workshop is inadequate. Other coaching resources are available to support coaching practice and promote continuous learning in SIT:

- Community of Practice: Coaching Conversations @SIT (offered to any interested academic staff)

- Coaching Circle (offered to all alumni of the coaching workshop)

- Coach Academy (knowledge repository with academic and coaching industry resources).

V. CONCLUSION

In coaching, there lies great potential for students to be developed holistically if we tap on coachable moments in higher education. A contextualised, well-developed coaching development programme is an enabler for this potential to be fulfilled. Drawing on evidence-based research from academia and professional practice, a practice-oriented programme which focuses on developing hands-on coaching skills will be impactful, as educators can put these skills into action in their interaction with students.

Notes on Contributors

Associate Professor Lim Sok Mui (May) led the Center for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD) and spearheaded the coaching initiative in the university, contributed to the conception, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Ramesh Shahdadpuri is the senior educational developer in CoLEAD and plays the role of the coaching trainer for the faculty training program. reviewed the literature, contributed to the conception and assisted in revising the manuscript.

Pua Ching Yee is the learning analyst in CoLEAD and plays the role of coordinating the coaching training and assessment of the participants. She assisted in critically reviewing, revising and formatting the manuscript.

All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

This is a narrative review related to coaching training program with no data presented and no ethical approval is required.

Data Availability

This paper is a narrative review with no data analysis.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Miss Cherine Foo for her significant contribution of the coaching program.

Funding

There is no funding involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Deiorio, N. M., Skye, E., & Sheu, L. (2017). Introduction and definition of academic coaching. In N. M. Deiorio & M. M. Hammoud (Eds.), Coaching in medical education: A faculty handbook (pp. 1-5). American Medical Association.

Grant, A. M., & Gerrard, B. (2020). Comparing problem-focused, solution-focused and combined problem-focused/solution-focused coaching approach: solution-focused coaching questions mitigate the negative impact of dysfunctional attitudes. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 13(1), 61-77. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2019.1599030

Griffiths, K. (2005). Personal coaching: A model for effective learning. Journal of Learning Design, 1(2), 55–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.5204/jld.v1i2.17

Lim, S. M. (2021, May 27). The answer is not always the solution: using coaching in higher education. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/answer-not-always-solution-using-coaching-higher-education

Whitmore, J. (2019). Coaching for performance: The principles and practice of coaching and leadership (5th ed.). Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

*Lim Sok Mui

Singapore Institute of Technology,

10 Dover Drive, Singapore 138683

+65 65921171

Email: may.lim@singaporetech.edu.sg

Submitted: 4 October 2022

Accepted: 5 December 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 66-69

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/SC2894

Simon Field1, Pat Croskerry2, Susan Love3, & Peggy Alexiadis Brown4

1Undergraduate Medical Education and Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; 2Critical Thinking Program, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; 3Faculty Development, Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; 4Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Abstract

Introduction: For all clinical providers in healthcare, decision-making is a critical feature of everything they do. Every day physicians engage in clinical decision-making where knowledge, evidence, experience, and interpretation of clinical data are used to produce decisions, yet, it is fair to say that most do not have an explicit insight or understanding of this complex process. In particular, few will have training in teaching and assessing the cognitive and affective factors that underlie clinical decision-making.

Methods: To foster an increased awareness and understanding of these factors, the Dalhousie Critical Thinking Program was established with the mandate to develop and deliver curriculum for critical thinking in the 4-year undergraduate program. To assist teaching faculty with the goal and objectives of the program, the Teaching and Assessing Critical Thinking Program (TACT) was introduced.

Results: Using the dual process model as a platform for decision-making, this program introduces general principles of critical thinking and provides tools to teach learners how to strengthen their critical thinking skills. To offer flexible learning, an online approach was chosen for delivery of the program.

Conclusion: To date, we have offered eleven iterations of Part 1 to a total of 261 participants and six iterations of Part 2 to a total of 89 participants. Evaluations show the online approach to content delivery was well received and the content to be of practical use.

Keywords: Critical Thinking, Clinical Decision-Making, Faculty Development, Asynchronous Learning

I. INTRODUCTION

This paper provides a review of a two-part Teaching and Assessing Critical Thinking (TACT) program which was developed to help faculty understand vulnerability to bias and the role of metacognitive processes in clinical decision-making. The objective of the TACT program is to better prepare faculty to teach learners these important skills. In this paper, we describe how it was implemented, how participants perceived the program, and what changes were needed to address this important hidden ‘soft’ skill within the clinical setting.

II. METHODS

Physicians are constantly required to interpret information when they interact with patients, communicate with colleagues, review medical histories and laboratory reports, conduct physical exams, review the medical literature, and attend rounds. All of these clinical activities demand a sustained level of accuracy, clarity, and especially rationality. Critical thinking (CT) does not guarantee rationality but is one of its more important features and is essential for the role of physician.

Reliable and accurate diagnosis is the barometer of good clinical decision-making and will have a direct impact on treatment outcomes and patient safety. One in 20 (or roughly 12 million) American adult outpatients are affected by diagnostic errors every year. The overall number of fatalities associated with diagnostic failure is not known, but it is estimated that 40,000 – 80,000 deaths occur annually in hospitalised patients in the USA due to diagnostic failure.

A number of studies have shown that training in the development of CT skills in undergraduate students is effective. (Abrami et al., 2015) However, given that most faculty in medical schools today will not have had explicit CT training, specific initiatives in teaching it seem appropriate, not only for the faculty themselves but, importantly, for the students they teach.