Minor tweaks to tutorial presentation improved students’ perceptions of our mass tutorial

Submitted: 15 August 2022

Accepted: 20 December 2022

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 54-57

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/SC2867

Seow Chong Lee & Foong May Yeong

Department of Biochemistry, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: In the first weeks of medical school, students learn fundamental cell biology in a series of lectures taught by five lecturers, followed by a mass tutorial session. In this exploratory study, we examined students’ perceptions of the mass tutorial session over two academic years to find out if they viewed the tutorials differently after minor tweaks were introduced.

Methods: Reflective questions were posted to the undergraduate Year 1 Medical students at the end of each mass tutorial session in 2019 and 2020. Content analysis was conducted on students’ anonymous responses, using each response as the unit of analysis. The responses were categorised under the learning objectives, with responses coded under multiple categories where appropriate. The distribution of the counts from responses in 2019 and 2020 was compared, and the tutorial slides used over the two years were reviewed in conjunction with students’ perceptions to identify changes.

Results: In 2019, we collected 122 responses which coded into 127 unique counts, while in 2020, 119 responses coded into 143 unique counts. Compared to 2019, we noted increases in the percentage of counts under “Link concepts” and “Apply knowledge”, with concomitant decreases in percentage of counts in “Recall contents”. We also found that the 2020 tutorial contained additional slides, including a summary slide and lecture slides in their explanations of answers to the tutorial questions.

Conclusion: Minor tweaks in the tutorial presentation could improve students’ perceptions of our mass tutorials.

Keywords: Mass Tutorials, Students’ Reflections, Apply Knowledge, Link Concepts, Minor Tweaks

I. INTRODUCTION

In the first few weeks of medical school, students learn about cell biology which is fundamental to what they need to know about tissues, organs, and the whole body in a series of lectures co-taught by five lecturers. In the lectures, efforts are made to highlight basic cellular processes, and illustrate how these are inter-connected in a cell. Where appropriate, how knowledge in the biomedical sciences underpins applications in clinical settings is also illustrated by the lecturers. At the end of the series of lectures, the lecturers will co-facilitate a mass tutorial session aimed at summing up the topics.

The mass tutorial session has several learning objectives. These include basic levels of learning such as recalling concepts, preparing for assessments, and building knowledge on topics, to higher levels of learning such as applying concepts to solve real life problems, and linking concepts between topics. Being the only teaching and learning activity that all lecturers co-teach, the mass tutorial provides the best opportunity to demonstrate links and apply the consolidated knowledge learnt during the different lectures.

Once the teaching and learning activities are completed, the coordinator of the lectures Foong May Yeong (YFM) reviews the curriculum to ensure that the teaching and learning activities delivered the intended learning objectives. Such reviews include students’ experiences of the curriculum (Erickson et al., 2008), which the coordinator (YFM) routinely collect through posting reflective questions at the end of the tutorial. In this exploratory study, we analysed students’ reflections from 2019 and 2020, and categorised them under different learning objectives of the tutorial. We noted an increase in percentage counts under “Apply knowledge” and “Link concepts” in 2020 compared to 2019. A review of the tutorial slides revealed the addition of summary and lecture slides in 2020. Our results suggest that minor tweaks to the tutorial presentation are sufficient to help students see the intended usefulness and relevance of tutorials.

II. METHODS

A. Format of Mass Tutorials

The mass tutorial was conducted after completion of the cell lectures. For 2019, this was a face-to-face session. For 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the tutorial was conducted online via Microsoft Teams. The class size was 281 for 2019, and 280 for 2020. Four out of five lecturers taught the same topics for both years. For both years, during the mass tutorial, each lecturer used Poll Everywhere to pose a mix of five to six recall and application questions linked to their topic. Identical questions were used in 2019 and 2020. Students discussed among themselves before answering these questions. The class responses were then revealed, after which the lecturer explained the solutions to their questions. The cycle was repeated until all the lecturers completed their parts.

B. Collection of Student Reflections

After each tutorial, the coordinator (YFM) posted two reflection questions on Poll Everywhere. The two questions were: 1. “What were the key points you learned in this session?”, 2. “Any questions?”. Answering these reflection questions were voluntary and anonymous. A waiver of informed consent was approved by Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Medical Sciences Departmental Ethics Review Committee. The responses to question 1 obtained from students in 2019 and 2020 were analysed in this study.

C. Content Analysis

The responses to question 1 were coded and categorized into the different learning objectives of the mass tutorial, using each response as a unit of analysis. Each response could be coded into multiple categories when appropriate. The counts under each category were represented as a percentage of all counts coded from the responses. The tutorial slides used in 2019 and 2020 were also reviewed to understand students’ perceptions.

III. RESULTS

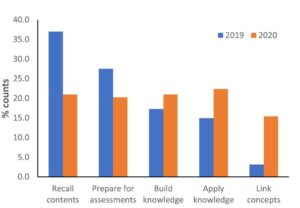

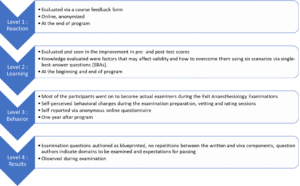

In 2019, we collected 122 responses which were coded into 127 unique counts. In 2020, we collected 119 responses which were coded into 143 unique counts. The number of responses and unique counts coded were largely similar between the two years. The unique counts were categorised into the five learning objectives and their percentage counts were presented in Figure 1. Supplemental data containing an overview of the categories and samples of students’ responses, as well as the counts under each category, are openly available in Tables 1 and 2 shared at Figshare at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20484498 (Lee & Yeong, 2022). The distribution of the counts differed between the two years. In 2019, majority of the counts were categorized to “Recall contents” (37.0%), with low numbers categorized as “Apply knowledge” and “Link concepts” (15.0% and 3.1% respectively). In comparison, in 2020, we observed a decrease in percentage of counts in “Recall contents” (to 21.0%), with an increased percentage in counts in “Apply knowledge” and “Link concepts” (to 22.4% and 15.4% respectively). Overall, there is a shift in distribution of counts, from a skewed distribution in 2019, to an even distribution in 2020.

Figure 1. Categorisation of students’ responses into the learning objectives

Given that tutorial questions used in the two years were largely identical, we reviewed the tutorial slides used in these two years to look for possible differences. In 2020, firstly, a summary slide detailing the different aspects of the cell was added to the start of the tutorial slides. Secondly, lecture slides were included in the tutorial slides to explain the answers to the tutorial questions. The lecture slides could come from the lecturer teaching the topic of interest, or from other lecturers if connections across topics were important. These additions could have altered students’ perceptions of the mass tutorial session in 2020.

IV. DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined students’ reflections collected across two academic years to understand their perceptions of the mass tutorial sessions that capped the teaching of cell biology. One of the intentions of the lecturers when designing the tutorial questions was to demonstrate links across topics, and illustrate how questions can be solved using connections across topics. The decrease in percentage of counts under “Recall contents” in 2020 suggested an increase in students’ awareness of the usefulness and relevance of the tutorial sessions when minor changes were made in the presentation of the overview of the cell biology topic and the answers to the tutorial questions.

Both lecture and summary slides likely promoted links in different ways. The lecture slides represent theoretical knowledge for each topic, and also add visuals to the explanations of tutorial questions. Inclusion of lecture slides allow students to use both visual and audio channels to process the explanations, instead of using only the audio channel to listen to explanations when they were delivered verbally without visuals (Mayer, 2014). Using both channels could lower the cognitive load for students to learn and construct meaningful frameworks to solve problems. Summary slides juxtaposed different topics within a slide, allowing students to visualize connections between topics in the proper functioning of a cell (Bae & Watson, 2014). Adding these slides require little effort from the lecturers as the slides are readily available. Such small changes in improving the instructional approach could result in improvements in student learning (Lang, 2016).

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, we only reviewed the tutorial slides, which covers part of the enacted curriculum. Secondly, the tutorial in 2019 was conducted face-to-face while the one in 2020 was conducted online. Online learning normally is not something students view positively, hence the improvements in student perceptions was surprising. Students prefer the social aspects of learning, which is abundant in face-to-face learning but greatly diminished in online learning (Siah et al., 2022). However, the diminished opportunities for peer-learning in online environment might contribute to increased attention diverted to lecturers for explanations.

V. CONCLUSION

Surveying and analysing students’ reflections at the end of mass tutorial proved to be informative in evaluating and improving our tutorials. In our preliminary analysis, a change in students’ perceptions of the tutorial from recalling of concepts to application of knowledge and linking concepts corresponded to minor tweaks in our tutorial presentation slides. Such minor tweaks, requiring little time, but yet are effective in helping students see the usefulness and relevance of tutorials, is an approach that even busy academics can do.

Notes on Contributors

Seow Chong Lee contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising of the manuscript.

Foong May Yeong contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting and revising of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Medical Sciences Departmental Ethics Review Committee (Reference code: MSDERC-2022-006).

Data Availability

An overview of the categorization of responses into categories and samples of students’ responses, as well as the counts under each category are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20484498.

Funding

This paper receives no funding from outside sources.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Bae, J., & Watson, B. (2014). Toward a better understanding and application of the principles of visual communication. In W. Huang (Ed.), Handbook of Human Centric Visualization (pp. 179-201). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7485-2_7

Erickson, F., Bagrodia, R., Gook-Sather, A., Espinoza, M., Jurow, S., Shultz, J. J., & Spencer, J. (2008). Students’ experience of school curriculum: the everyday circumstances of granting and withholding assent to learn. In F. M. Connelly, M. F. He, & J. Phillion. (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Curriculum and Instruction (pp. 198-218). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976572.n10

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Lee, S. C., & Yeong, F. M. (2022). Minor tweaks to tutorial presentation improved students’ perceptions of our mass tutorial. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20484498

Mayer, R. E. (2014). Multimedia instruction. In M. Spector, D. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. J. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 385-399). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_31

Siah, C. R., Huang, C. M., Poon, Y. S. R., & Koh, S. S. (2022). Nursing students’ perceptions of online learning and its impact on knowledge level. Nurse Education Today, 112, Article 105327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105327

*Foong May Yeong

MD4, 5 Science Drive 2,

S117545

+65 6516 8866

Email: bchyfm@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 28 April 2022

Accepted: 9 February 2023

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 50-53

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/SC2798

Olivia MY Ngan1,2, Jasmine YN Hui3 & Sihan Sun4

1Medical Ethics and Humanities Unit, School of Clinical Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, HKSAR; 2Centre for Medical Ethics and Law, Faculty of Law and LKS School of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong; 3Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR; 4CUHK Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Abstract

Introduction: Didactic pedagogy and passive learning in bioethics and medical humanities teaching are ineffective in engaging students and gauging learning interests. As a result, medical students are unaware of why and how bioethics and medical humanities relate to their learning and thus prioritising acquiring clinical knowledge in their medical education.

Methods: This project involves a teacher-student collaboration to develop a teaching approach, which bridges historical events and contemporary issues, acknowledging how ethics and humanities are interwoven in clinical and everyday life. The objectives are to (1) highlight landmark historical events in bioethics and medical humanities and (2) recognise the evolving nature of values and social norms that inform current practice.

Results: The three activities include the use of historical narratives, annual newsletter publications, and social media to augment didactic classroom teaching and learning. Video narratives of landmark events in bioethics were developed to strengthen historical knowledge and encourage self-reflection. The newsletter invited students to write about any topic in bioethics and medical humanities and enabled them to experience a peer-review process. It allowed students to critically appraise everyday issues. Social media engagement via Instagram offered a flexible and informal medium to diversify the traditional bioethics content taught in the classroom. The advantages and obstacles of each element are discussed.

Conclusion: A holistic approach using historical narratives, newsletters, and social media engages students’ learning and allows students to become conscious of how past events shape the present.

Keywords: Bioethics, Medical Ethics, Medical Humanities, Education, History, Curriculum Development, Social Media, Student as Partner, Newsletter

I. INTRODUCTION

With modern bioethics taking shape in the late 1960s, the introduction of formal bioethics teaching in medical schools developed slowly in Europe and Northern America over the subsequent decades. It was recognised that professional ability not only encompassed scientific knowledge and clinical skills, but also embodied a high standard of professional ethics, values, and moral conduct. A paradigm shift in how medical education shaped students’ moral compasses and holistic decision-making abilities was needed. In 1987, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education stated that medical schools must incorporate bioethics and medical humanities teaching into their curricula (Carrese et al., 2015). In 1993, the British General Medical Council published a white paper, Tomorrow’s Doctors, which outlined a blueprint for reforming the curriculum and affirmed that teaching ethics and law was an integral part of medical education (Mattick & Bligh, 2006).

Bioethics teaching started relatively late in Asia-Pacific and is strategically less developed in its teaching content, methodology, and assessment (Qian et al., 2018; Sim et al., 2019). There is little discussion on how to best deliver bioethics education through a multidisciplinary lens, as the disciplines of humanities (e.g., philosophy, history, and law), social sciences (e.g., anthropology and sociology), and arts (e.g., literature) are extensive. Our team recognised that passive learning using conventional pedagogy (e.g., didactic lectures and tutorials) had significant drawbacks. Earlier studies showed that teachers adopting these methods struggled to engage and stimulate students’ reception to ethics learning (Ganguly et al., 2022; Ngan & Sim, 2021). They were unaware of why and how bioethics and medical humanities were related to their science background, called them “soft” subject, and thus prioritised acquiring clinical knowledge (Leo & Eagen, 2008).

This paper describes a new teaching approach that draws reference from the philosophy of history teaching, using the past to understand and predict present and future actions. We describe three activities, including using historical narratives, annual newsletter publications, and social media to augment classroom teaching and learning in hopes of promoting ethical sensitivity to students’ clinical and everyday life experiences. Our learners are medical students undertaking a six-year undergraduate medical degree programme. These activities were implemented to support pre-clinical year teaching, though also applicable to clinical year students.

II. DESCRIPTIONS OF THREE TEACHING ACTIVITIES

A. Historical Narratives

The adoption of historical narratives in bioethics teaching draws reference from the philosophy of history teaching, using the past to appreciate the present and the future. But its history is often neglected in the curriculum due to time constraints. Students perceived a disconnection between themselves and unethical events, struggling to understand the significance and effects specific past events may have had on present society (Ngan & Sim, 2021). Gerald L. Gutek (1995), History Educator, advocated that “[teaching] should illuminate the past in order to provide the perspective in time and place that we need to make reflective decisions on the [medical] education choices that face us today. Understanding the importance of bioethics history reminds ourselves about the wrongdoings in science, either due to procedural insensitivity or limited guidelines, and may also improve individual behaviour and organisational culture, re-enforcing a high standard of professional conduct. The video narratives reinforce historical knowledge and the ability to discern and scrutinize the similarities and differences between the past and present.

In this pilot project supported by the faculty’s teaching development grant, landmark historical events were developed as short video narratives that complemented the teaching curriculum topic. Table 1 is a non-exhaustive list of examples describing key events in ethics and how they relate to contemporary issues. In our experience, the video productions were well-received by students’ feedback evaluation. The high cost, however, would be a concern. Should the video improve students’ sensitivity towards bioethics, a comprehensive development of bioethics history video should be invested as an educational media to support teaching.

|

Historical Events |

Related Ethical Concerns |

Contemporary Issues |

|

Eugenics measures in the United States (1896- 1940), Germany (1933-45), and Japan (1948-1996) |

Eugenics |

Emerging technologies (e.g., gene-editing technologies, preimplantation diagnosis, and prenatal diagnosis) |

|

The “God” Committee: Rationing dialysis machines (1961) |

Equity, fair allocation approach, transplantation ethics |

Allocation of scarce resources (e.g., vaccine, ICU bed, funds) |

|

Tuskegee Syphilis Study, (1972) |

Research ethics (e.g., informed consent, exploitation of vulnerable populations) |

Research involving vulnerable populations (e.g., homeless, inmates) |

|

Stanford Prison Experiment (1971)

Milgram’s “destructive obedience” Study (1974) |

Unethical research conduct was uncovered (e.g., psychological harms, deception) |

Social and behaviour research illuminates the need for participant protection beyond the scope of biomedical studies. |

|

Table 1. Implications of Landmark Events on Present-day |

||

B. Bioethics Newsletter

In this pilot project, our team incepted a student-led bioethics newsletter aiming to draw ethical sensitivity in everyday life. Medical students were invited to contribute and write a commentary based on a topical issue of their interest; stimuli may have ranged from the news, movies, dramas, documentaries, plays, clinical ward experiences, and overseas observations. The opportunity provided students with a platform to voice and elucidate their opinions. It also allowed students to be more receptive to opposing ideas, developing a greater awareness of ethical dilemmas.

We published three annual newsletters and reflected on our experience. In the first issue, there was no peer-review process. We felt that the absence of a communication medium between the student writers and student editors hindered the quality of submissions. A peer-review process was implemented starting from the second issue, which was perceived to be beneficial as students were able to receive feedback and enhance intellectual rigour. More importantly, students were also exposed to the peer-reviewing process, which is useful for their future professional career development in academia.

Several obstacles relating to the submission process and the future sustainability of the newsletter were also met. In the first issue, interest was generated primarily through word-of-mouth and promotion on social media. In the second issue, prize incentives were given to best-written submissions. Participation gained momentum in the second and third issues, where we saw an average of 15-20 submissions. Sustainability was also a concern in terms of reader engagement and recruiting altruistic junior students to take over the project. To encourage multidisciplinary engagement, we aim to call for submissions in both written Chinese and English and accept entries from all students within the medicine faculty. We have a long-term goal of fostering a multidisciplinary collaboration across the Faculties.

C. Social Media

Given the generational influx of physicians and medical educators, the use of social media in medical education has seen rising popularity in recent years. Platforms like Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn are easily accessible, user-friendly and encourage users’ interaction in a local and international setting. The flexibility of social media may also promote active learning pedagogies and personalised education, allowing students to build upon the knowledge they perceive to be interesting.

We started an Instagram page (IG: cubioethics) in June 2020 and curated content on a monthly basis. Content covered a broad range of bioethical topics, including several themed series: a news roundup named “Ethics in the News” and a series based on biotechnology seen in the sci-fi television series, Black Mirror. Each post consisted of a short synopsis on the topic and multiple discussion points were raised to incite critical thinking and reflection.

The flexibility and informal nature of Instagram allowed us to diversify the traditional bioethics content taught in the classroom. For example, it offered an experimental opportunity to teach through television and film. Moreover, the Instagram page allowed us to connect with students and professionals from local and international institutes. Engagement was reflected in post shares, likes, comments, and page follows. As the bioethics community on Instagram remains relatively small, it was easy to establish rapport. This community was able to help expand our audience via mutual post sharing and furthered the ethical debate raised in our posts.

Maintaining an Instagram page was not easy – content creation, the design process, and engaging with readers required careful planning and time. Also, from a cultural standpoint, it seemed as if there was a stronger tendency for international users to publicly participate in the conversation by commenting rather than local students. This may be due to worries about online criticism or the pervasive nature of social media and how it may no longer be viewed as a “safe space” for controversial discourse.

III. CONCLUSION

We reflected on our experience refining traditional didactic pedagogy by adopting three activities: historical narratives, newsletters, and social media. Each component presents unique educational benefits (e.g., recounting the evolution of today’s achievements, exposing students to peer-review publishing experience, cultivating sensitivities to everyday life) and operational barriers (e.g., budget constraints, altruistic students’ recruitment, time- and labour-intensive). Our teaching pedagogy may also be adopted in bioethics teaching in other disciplines, including biomedical and life sciences.

Notes on Contributors

OMYN conceived the study, developed the narration scripts, facilitated the newsletter peer-review as a teacher editor, reviewed the literature, and drafted the intellectual content of the manuscript.

JYNH led the newsletter peer-review as a student editor, managed the social media platform, and drafted the intellectual content of the manuscript.

SS reviewed newsletter entries and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and approve the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study involves a theoretical discussion only and does not require ethical approval.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Figshare repository. http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19768264

Funding

The study is supported by the Teaching Development and Language Enhancement Grant (TDLEG) for the 2019-22 Triennium. The funders had no role in the content review of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Carrese, J. A., Malek, J., Watson, K., Lehmann, L. S., Green, M. J., McCullough, L. B., Geller, G., Braddock III, C. H., & Doukas, D. J. (2015). The essential role of medical ethics education in achieving professionalism: The Romanell Report. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 744–752. http://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000715

Ganguly, B., D’Souza, R., & Nunes, R. (2022). Challenges in the teaching–learning process of the newly implemented module on bioethics in the undergraduate medical curriculum in India. Asian Bioethics Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-022-00225-2

Gutek, G. L. (1995). A history of the western educational experience (2nd ed.). Waveland Press, Inc.

Leo, T., & Eagen, K. (2008). Professionalism education: The medical student response. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 51(4), 508–516. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0058

Mattick, K., & Bligh, J. (2006). Teaching and assessing medical ethics: Where are we now? Journal of Medical Ethics, 32(3), 181–185. http://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2005.014597

Ngan, O. M. Y., & Sim, J. H. (2021). Evolution of bioethics education in the medical programme: A tale of two medical schools. International Journal of Ethics Education, 6, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-020-00112-0

Qian, Y., Han, Q., Yuan, W., & Fan, C. (2018). Insights into medical humanities education in China and the West. Journal of International Medical Research, 46(9), 3507–3517.

Sim, J. H., Ngan, O. M. Y., & Ng, H. K. (2019). Bioethics education in the medical programme among Malaysian medical schools: Where are we now? Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 6.

*Olivia M.Y Ngan

Medical Ethics and Humanities Unit,

School of Clinical Medicine,

Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine,

The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam,

Hong Kong Island, Hong Kong SAR

Email: olivian1@hku.hk

Submitted: 30 Nov 2022

Accepted: 30 Jan 2023

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 45-49

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/SC2921

Sasikala Devi Amirthalingam1, Shamala Ramasamy2 & Sharifah Sulaiha Hj Syed Aznal3

1Department of Family Medicine, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2Department for Psychology, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: Introduction to Health Profession (IHP) was designed to teach first-year medical students the importance of self-directed learning, accountability, and teamwork in healthcare. Due to the COVID 19 pandemic, the course was delivered virtually, incorporating elements of gamification.

Methods: Gamification features included collaborative teamwork to simulate and record the roleplay for assignments based on crisis management scenarios. The syllabus involves knowledge checks to promote self-directed learning and personal accountability as well as online questionnaires to identify personality traits followed by discussion. Games like Chinese whispers and charades were introduced to identify listening skills. Additional gamification features include progress mechanics for collecting badges upon successful completion of knowledge checks / assessments and completing collaborative teamwork activities.

Results: Results from the descriptive study on the educational usefulness of the IHP module was found to be satisfactory. The feedback was encouraging as >95% of students gave positive feedback that the IHP activities enabled them to understand the value of teamwork, effective communication, professional behavior and enabled them to be resilient and adaptable. 92% agreed that the IHP activities helped to make connections and network with their peers during the pandemic

Conclusion: Gamification of IHP course was successful in terms of practicality and usefulness in promoting communication, collaborative work, experiential learning, and teamwork. Students were empowered to take charge of their own learning of both content and development of interpersonal skills and teamwork through gamification. The isolation caused by the pandemic was alleviated by the networking that occurred during collaborative group activities.

Keywords: Gamification, Self-directed Learning, Collaborative Learning

I. INTRODUCTION

Introduction to Health Profession (IHP) course was initiated during Covid-19 pandemic and conducted at the beginning of our medical program enrolment to introduce freshmen to the real world and value systems of health professional. The learning activities were designed to provide real life experiences, exposing to communication skills within the community and peers, professionalism including teamwork and ethics, and the value of self-reflecting practice. The isolation caused by the pandemic was alleviated by networking that occurred during collaborative group activities and online interactive discussion with invited speakers of health professionals. The group activities were gamified to make learning fun, memorable, engaging and motivating. It is designed to promote a sense of accomplishment while learning through discovery and during the social interaction.

Gamification in education has existed since time immemorial but with the advent of wireless technology, it has given rise to unique ways to improve student engagement (Dodson, 2021) in learning. Gamification is defined as “the craft of deriving all the fun and addicting elements found in games and applying them to real-world or productive activities” (Chou, 2012). There is growing evidence for gamification in a wider pedagogical context and the concept is gaining traction within the medical education community. These “fun and addicting elements” include progress mechanics such as badges, narrative structure and immediate feedback. The gamification features introduced in the IHP module are badges, immediate feedback, challenges in the form of knowledge checks and roleplay in virtual reality in crisis management scenarios.

II. METHODS

Collaborative group activities were conducted by dividing 171 first year students into 16 small groups. Activities were carried out using synchronous and asynchronous virtual platforms to accommodate about 40 % of international students who were still in their home countries. Lessons in IHP consisted of recognising personality traits, application of communication skills, ethics and professionalism and recognising teamwork as intrinsic requirements for delivery of effective healthcare.

Asynchronous sessions required students to individually go through the prepared learning materials followed by knowledge checks. Test repetition without penalty is allowed within an allotted time frame until learners reach a satisfactory result. Following successful completion of knowledge check, students would earn their badge of completion.

Activities like ‘discovering personality traits’ are conducted as online synchronous workshops and facilitated by a group of psychologists. Self-administered questionnaire was administered to determine personality traits, followed by a psychologist-led group discussion to share feedback and reflection. Having the session on a virtual platform provided the students with a degree of anonymity, which enabled them to share profound reflections and feedback. Through the questionnaire responses, the psychologists were able to identify red flags and reach out to the students.

During the online ‘communication skills’ workshop, games such as Chinese whispers and charades were used to cultivate active listening skills and understand nonverbal communication. Students were assigned to group works comprising of preparing oral presentations on scenarios involving ethics and professionalism. In addition, they were tasked to solve issues in selected crisis management scenarios using role-plays and virtual reality. Creativity is highly encouraged and weighted with high percentage. This encourages social interaction and influences learning by creating a subjective sense of presence to facilitate virtual experiential learning.

Upon completion of the IHP activities, students are required to complete a self-administered questionnaire to feedback on the efficacy of the module, hence implied consent is given. The questionnaire measured whether the gamification of IHP achieved the learning outcomes of enabling the understanding of the value of teamwork, effective communication, professional behaviour and to be adaptable and resilient. In addition, the questionnaire inquired if participation in IHP activities helped them create contacts and network with their peers. Open comments are sought after for thematic analysis.

III. RESULTS

51.4% of the cohort responded to the self-administered online questionnaire. Feedback was encouraging as >95% of students gave positive feedback. They felt IHP activities enabled them to understand the value of teamwork, effective communication, professional behaviour and being resilient and adaptable. Most agreed IHP activities helped to make connections and network with peers during the pandemic. Many agreed they developed some insight about themselves during IHP activities. Several themes were drawn from the collected feedback. The primary theme is teamwork where students demonstrate co-operation in working together in teams to attain mutual goals and learn leadership qualities. Majority felt they developed skills in active listening, organisation, patience, self-confidence, and showing empathy. Other characteristics learnt were resilience building, controlling emotions, adaptation, overcoming challenges, professionalism and ethical behaviour.

Common comments on areas to improve are their lack of confidence and discomfort in expressing one’s thoughts. Both being too rigid and overly flexible were commented. Other comments were not feeling at ease with working in a team, becoming overwhelmed, paying excessive attention to detail, and becoming frustrated. Being shy and quiet as well as not being assertive were among the constructive feedback (See Table 1). A copy of the survey questions and the additional tables of survey results are openly available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21656864.

|

Student Feedback for the Introduction to Health Profession (IHP) module Total number of respondents: 88 |

|||

|

NO. |

THEMES |

OPEN FEEDBACK FROM STUDENTS |

|

|

Majority of the positive responses are as follows: |

Common comments on areas to improve self: |

||

|

1 |

Teamwork |

|

|

|

2 |

Effective Communication |

|

|

|

3 |

Professional Behavior |

|

|

|

4 |

Adaptability and resilience |

|

|

|

5 |

Making connections and networking with peers |

|

|

|

6 |

Insight to self |

|

|

|

Table 1. Student Feedback from IHP Cohort ME121 |

|||

IV. DISCUSSION

IHP is a new course with the objectives of introducing students to the real world and value systems of the health professional, focusing on communication skills, medical ethics, teamwork, and the importance of self-reflective practice. The learning is mainly facilitated by group work and formative assessment through immediate provision of feedback and self-reflection. Due to pandemic-related restrictions, the initial plans for real life experience and exposure in IHP course had to be converted to the online platform. An instructional method such as gamification was selected to help retain student engagement and encourage participation (Chou, 2012). Applying the design elements and principles found in games to education was useful in sparking student interest and motivation (Chou, 2012).

Knowledge checks challenged the minds, improved cognition and knowledge retention (Singhal et al., 2019). Progress mechanics in the form of earning ‘a badge on completion’ of assigned activities, going through the provided learning material and completing the knowledge check to an acceptable level, promoted self-directed learning, created a sense of achievement and retained student engagement. This reward system fosters student participation, as it is a tangible reward (Dodson, 2021).

The seclusion from real life interaction is feared to mentally and psychologically affect students. A study in Switzerland has shown a significant impact on the mental health of learners due to the lockdown in 2020 (Elmer et al., 2020). In another study, social interaction is recognised as an important factor for enhancing learning especially in areas of critical thinking and problem solving (Hurst et al., 2013). The group works in the IHP course, though set virtually, have assisted students in networking and socialising during the pandemic. This was agreed by majority of the students who participated in IHP activities.

Effective leadership is essential in delivering high standards of clinical practice. The students learnt leadership skills through organising group work, delegating roles and responsibilities among team members. Among the examples of group work are problem- solving scenarios like managing a fire in CCU or multiple vehicle accident on the highway. The instructional content was related to the teamwork and roles and responsibilities of the different health professionals involved in managing the crisis and it was gamified by adding elements of game fiction such as the different themes, settings and characters. As students had to self- produce scripts after some brief research of relevant contents, they had some autonomy over the depth and breadth of their learning. Working in teams towards common goals lead to improved productivity and self-esteem and created supportive relationships during the collaborative learning (Singhal et al., 2019). Narrative synthesis and role playing in scenarios managing crisis situations stimulated reflective practice whilst integration of cause and effect enabled experiential learning.

Overall feedback was encouraging as almost all students enjoyed the activities and found them both educational and engaging. They discovered characteristics in themselves that helped them to improve team spirit and communication. The groupwork on the various projects developed learning communities and promoted interpersonal skills, integrating diverse learner types with a wide range of knowledge, skills, past experiences and personal attributes. This was effectively utilized in the groupwork and collaborative learning.

Some setbacks occurred when both the faculty and students were unfamiliar with online gamification. The synchronous sessions with international students in different time zones, made group discussions challenging. Support from the Information Technology team is valuable but poses an exorbitant cost. Students having expectations of medical school learning to be more didactive, instead had to adapt to being adult learners, for more extensive self- directed learning and reflective practice.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, gamification of IHP module encouraged student engagement, teamwork and collaborative learning. IHP course was accessible virtually, which was a boon for our international students who could interact virtually with peers and access and take part in the lessons. The gamification features used were reproducible. Gamification is useful in medical education and can be pursued as a method to deliver lessons and engage students. It is a tool to allow learning in depth and for experiential learning on the virtual platform.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Sasikala Devi Amirthalingam is the first author, contributing to the abstract, introduction, discussion and literature review. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Shamala Ramasamy is the second author, contributing to methodology, results and literature review. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prof Sharifah Sulaiha Hj Syed Aznal is the third author, contributing to abstract, introduction, discussion and revising it critically for important intellectual content. She agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

The dean of School of Medicine, International Medical University has given a letter to say that there is no objection to sharing of findings for educational purpose.

Data Availability

The data that support the finding are openly available in the Figshare repository. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21656864

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Fareeza Marican Bt Abu Backer and Norhasliza Binti Hashim from E Learning Department from International Medical University for the technical assistance in the gamification features to the module.

Funding

There is no financial support or any financial relationships that may pose a conflict of interest.

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflicting interest to any parties concerned.

References

Chou, Y. K. (2012). What is gamification. Yukai Chou: Gamification and Behavioral Design. https://yukaichou.com/gamification-examples/what-is-gamification/

Dodson, K. R. (2021). Can gamification drive increased student engagement? Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/sponsored/2021/10/can-gamification-drive-increased-student-engagement

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15(7), Article e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Hurst, B., Wallace, R., & Nixon, S. B. (2013). The impact of social interaction on student learning. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 52(4), Article 5. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol52/iss4/5

Singhal, S., Hough, J., & Cripps, D. (2019). Twelve tips for incorporating gamification into medical education. MedEdPublish, 8(3), Article 216.

*Sasikala Devi Amirthalingam

International Medical University,

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

+60133513435

Email: SasikalaDevi@imu.edu.my

Submitted: 30 May 2022

Accepted: 7 December 2022

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 35-44

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/OA2876

Rachel Jiayu Lee1*, Jeannie Jing Yi Yap1*, Abhiram Kanneganti1, Carly Yanlin Wu1, Grace Ming Fen Chan1, Citra Nurfarah Zaini Mattar1,2, Pearl Shuang Ye Tong1,2, Susan Jane Sinclair Logan1,2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, National University Hospital, Singapore; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

*Co-first authors

Abstract

Introduction: Disruptions of the postgraduate (PG) teaching programmes by COVID-19 have encouraged a transition to virtual methods of content delivery. This provided an impetus to evaluate the coverage of key learning goals by a pre-existing PG didactic programme in an Obstetrics and Gynaecology Specialty Training Programme. We describe a three-phase audit methodology that was developed for this

Methods: We performed a retrospective audit of the PG programme conducted by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at National University Hospital, Singapore between January and December 2019 utilising a ten-step Training Needs Analysis (TNA). Content of each session was reviewed and mapped against components of the 15 core Knowledge Areas (KA) of the Royal College of Obstetrics & Gynaecology membership (MRCOG) examination syllabus.

Results: Out of 71 PG sessions, there was a 64.9% coverage of the MRCOG syllabus. Four out of the 15 KAs were inadequately covered, achieving less than 50% of knowledge requirements. More procedural KAs such as “Gynaecological Problems” and those related to labour were poorly (less than 30%) covered. Following the audit, these identified gaps were addressed with targeted strategies.

Conclusion: Our audit demonstrated that our pre-pandemic PG programme poorly covered core educational objectives i.e. the MRCOG syllabus, and required a systematic realignment. The COVID-19 pandemic, while disruptive to our PG programme, created an opportunity to analyse our training needs and revamp our virtual PG programme.

Keywords: Medical Education; Residency; Postgraduate Education; Obstetrics and Gynaecology; Training Needs Analysis; COVID-19; Auditing Medical Education

Practice Highlights

- Regular audits of PG programmes ensure relevance to key educational objectives.

- Training Needs Analysis facilitates identification of learning goals, deficits & corrective change.

- Mapping against a milestone examination syllabus & using Delphi technique helps identify learning gaps.

- Procedural-heavy learning goals are poorly served by didactic PG and need individualised assessment.

- A central committee is needed to balance the learning needs of all departmental CME participants.

I. INTRODUCTION

Postgraduate medical education (PG) programmes are an important aspect in meeting core Specialty Trainees’ (ST) learning goals in addition to other modalities of instruction such as practical training (e.g. supervised patient-care or simulator-based training) (Bryant‐Smith et al., 2019) and workplace-based assessments (e.g. case-based discussions and Objective Structured Clinical Examinations [OSCEs] (Chan et al., 2020; Parry-Smith et al., 2014). In academic medical centres, PG education may often be nestled within a wider departmental or hospital Continuing Medical Education (CME) programme. While both PG and CME programmes indirectly improve patient outcomes by keeping clinicians abreast with the latest updates, reinforcing important concepts, and changing practice (Burr & Johanson, 1998; Forsetlund et al., 2021; Marinopoulos et al., 2007; Norman et al., 2004; Raza et al., 2009; Sibley et al., 1982), it is important to balance the learning needs of STs with that of other learners (E.g. senior clinicians, scientists and allied healthcare professionals). This can be challenging as multiple objectives need be fulfilled amongst various learners. Nevertheless, just as with any other component of good quality patient care, it is amenable to audit and quality improvement initiatives (Davies, 1981; Norman et al., 2004; Palmer & Brackwell, 2014).

The protracted COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the way we deliver healthcare and conduct non-clinical services (Lim et al., 2009; Wong & Bandello, 2020). In response, the academic medical community has globally embraced the use of teleconferencing platforms such as ZoomⓇ, Microsoft TeamsⓇ and WebexⓇ (Kanneganti, Sia, et al., 2020; Renaud et al., 2021) as well as other custom-built solutions for the synchronous delivery of didactics and group discourse (Khamees et al., 2022). While surgical disciplines have suffered a decline in the quality of “hands-on” training due to reduced elective surgical load and safe distancing (English et al., 2020), the use of simulators (Bienstock & Heuer, 2022; Chan et al., 2020; Hoopes et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2022), remote surgical preceptorship, and teaching through surgical videos (Chick et al., 2020; Juprasert et al., 2020; Mishra et al., 2020) have helped mitigate some of these. Virtual options that that have been reproducibly utilised during the pandemic and will be a part of the regular armamentarium of post-graduate medical educationists include online didactic lectures, livestreaming or video repositories of surgical procedures, (Grafton-Clarke et al., 2022) and virtual case discussions and grand ward rounds (Sparkes et al., 2021). Notably, they facilitate the inclusion of a physically wider audience, be it trainer or trainee, and allow participants to tune in from different geographical locations.

At the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, National University Hospital, Singapore, the forced, rapid transition to a virtual CME format (vCME) (Chan et al., 2020; Kanneganti, Lim, et al., 2020) provided an impetus to critically review and revamp the didactic component of our PG programmes. A large component of this had been traditionally baked into our departmental CME programme which comprises daily morning meetings covering recent specialty and scientific updates, journal clubs, guideline reviews, grand round presentations, surgical videos, exam preparation, topic modular series, and research and quality improvement presentations. The schedule and topics were previously arbitrarily decided by a lead consultant one month prior and were presented by a supervised ST or invited speaker. While attendance by STs at these sessions was mandatory and comprised the bulk of protected ST teaching time, no prior attempt had been made to assess its coverage of core ST learning objectives and in particular, the syllabus for milestone ST exams.

Our main aim was to conduct an audit on the coverage of our previous PG didactic sessions on the most important learning goals with the aim of subsequently restructuring them to better meet these goals.

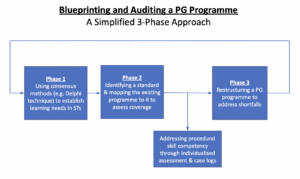

II. METHODS

We audited and assessed our departmental CME programme’s relevance to the core learning goals of our STs by utilising a Training Needs Analysis (TNA) methodology. While there are various types of TNA used in healthcare and management (Donovan & Townsend, 2019; Gould et al., 2004; Hicks & Hennessy, 1996, 1997; Johnston et al., 2018; Markaki et al., 2021), in general they represent systematic approaches towards developing and implementing a training plan. The common attributes can be distilled into three common phases (Figure 1). Importantly for surgical and procedurally-heavy disciplines, an dimension that is not well covered by didactic sessions alone are assessments for procedural skill competency. These require separate attention that is beyond the scope of this audit.

Figure 1. A simplified three phase approach to blueprinting, mapping, and auditing a Postgraduate (PG) Education Programme

A. Phase 1: Identifying Organisational Goals and Specific Objectives

The overarching goal of a specialty PG education programme is to produce well-balanced clinicians with a strong knowledge base. Singapore’s Obstetrics and Gynaecology specialty training programmes have adopted the membership examinations for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (MRCOG) (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2021) of the United Kingdom as the milestone examination for progression from junior to senior ST.

First, we adapted a ten-step TNA proposed by Donovan & Townsend (Table 1) to crystallise our our core learning goals, identify deficiencies, and subsequently propose steps to address these gaps in a systematic fashion that is catered to our specific context. While most aspects were followed without change, we adapted the last aspect i.e. Cost Benefit Analysis. As a general organisational and management tool, the original TNA primarily looked at the financial costs of implementing a training programme. At an academic medical institution, the “cost” is mainly non-financial and mainly refers to time taken away from important clinical service roles.

As part of formulating what were deemed to be core learning goals of an ideal PG programme (i.e. Steps 1 to 4), we had a focused group discussion comprising key stakeholders in postgraduate education, including core faculty (CF), physician faculty (PF), and representative STs. The discussions identified 18 goals specific to our department. We then used a modified Delphi method (Hasson et al., 2000; Humphrey-Murto et al., 2017) to distil what CF, PFs, and STs felt were important priorities for grooming future specialists. Three rounds of priority ranking were undertaken via an anonymised online voting form. At each round, these 18 goals were progressively ranked and distilled until five remained. These were then ranked from highest to lowest priority and comprised 1) exam preparedness, 2) clinical competency, 3) in-depth understanding of professional clinical guidelines, 4) interpretation of medical research literature, and 5) ability to conduct basic clinical research and audits.

|

Training Needs Analysis |

||

|

1 |

Strategic objectives |

|

|

2 |

Operational outcome |

|

|

3 |

Employee Behaviours |

|

|

4 |

Learnable Capabilities |

|

|

5 |

Gap Assessment |

|

|

6 |

Prioritise Learning and Training Needs |

|

|

7 |

Learning Approaches |

|

|

8 |

Roll-out Plan |

|

|

9 |

Evaluation Criteria |

|

|

10 |

Cost Benefit Analysis |

|

Table 1. 10-step Training Needs Analysis

Table adapted from Donovan, Paul and Townsend, John, Learning Needs Analysis (United Kingdom, Management Pocketbooks, 2019)

MRCOG: Member of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, O&G: Obstetrics and Gynaecology

CREOG: Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology

ACGME: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education,

PG: Post-Graduate Education

B. Phase 2: Identifying a Standard and Assessing for Coverage against This Standard

As with any audit, a “gold-standard” should be identified. As the focus group discussion and Delphi method identified exam preparedness as the highest priority, we created a “blueprint” based on the syllabus of the MRCOG examination (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2019). This comprised more than 200 Knowledge Requirements organised more than 200 knowledge requirements into 15 Knowledge Areas (KAs) (Table 2). We mapped the old CME programme against this blueprint to understand the extent of coverage of these KAs. We analyse the session contents between January and December 2019. We felt the best way to ensure systematic coverage of these KAs would be through sessions with pre-identified areas of topical focus conducted during protected teaching time as opposed to opportunistic and voluntary learning opportunities that may not be widely available to all STs. In our department, this applied to morning CME sessions which indeed formed the bulk of protected teaching time for STs, required mandatory attendance, and comprised sessions covering pre-defined topics. Thus, we excluded didactic sessions where 1) the content of the presentations was unavailable for audit, 2) they covered administrative aspects and did not have a pre-identified topical focus where learning was opportunistic (e.g. risk management meetings, labour ward audits), and 3) where the attendance was optional.

Mapping was conducted independently by two members of the study team (JJYY and CYW) with conflict resolved by a third member (RJL). The number of knowledge requirements fulfilled within a KA were expressed as a percentage.

|

Core knowledge areas |

|

Clinical skills |

|

Teaching and research |

|

Core surgical skills |

|

Post operative care |

|

Antenatal care |

|

Maternal Medicine |

|

Management of Labour |

|

Management of delivery |

|

Postpartum problems |

|

Gynaecological problems |

|

Subfertility |

|

Sexual and reproductive health |

|

Early pregnancy care |

|

Gynaecological Oncology |

|

Urogynaecology & pelvic floor problems |

Table 2. RCOG Core Knowledge Areas (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2019)

C. Phase 3: Restructuring a PG Programme

The final phase i.e. the restructuring of a PG programme, is directed by responses to Steps 7-10 of the 10-step TNA (Table 1). As the focus of our article is on the methodology of auditing the extent of coverage of our departmental didactic sessions over our core ST learning goals i.e. the MRCOG KAs, these subsequent efforts are detailed in the discussion section.

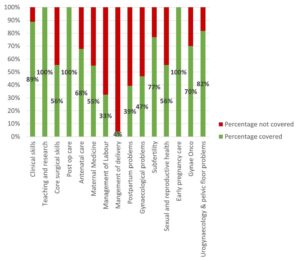

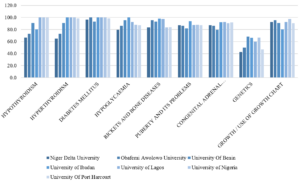

III. RESULTS

Altogether, 71 presentations were identified (Table 3) of which 12 CME sessions (16.9%) were unavailable and, thus, excluded from the mapping exercise. The most common types of CME sessions presented clinical updates (31.0%), original research (29.6%), journal clubs (16.9%), and exam-preparation sessions (e.g. Case Based Discussion and OSCE simulations) (12.6%). The overall coverage of the entire syllabus was 64.9% (Figure 2). The KAs demonstrating complete coverage (i.e. 100% of all requirements) were “Teaching and Research”, “Postoperative Care” and “Early Pregnancy Care”. Three KAs had a coverage of 75-100% in the CME programme i.e. “Clinical Skills” (89%), “Urogynaecology and Pelvic Floor” (82%), and “Subfertility” (77%) while three were covered below 50% i.e. “Management of Labour”, “Management of Delivery”, “Postpartum Problems”, and “Gynaecological Problems”. These were more practical KAs that were usually covered during ward covers, operating theatre, clinics, and labour ward as well as during practical skills training workshops and grand ward rounds where clinical vignettes were opportunistically discussed depending on in-patient case mix. Nevertheless, this “on-the-ground” training is often unplanned, unstructured and ‘bite-sized’, thus complicating integration with the deep and broad guideline and knowledge proficiency that may be needed to train STs to adapt to complex situations.

|

Type of presentation |

Number of sessions |

Percentage breakdown |

|

Clinical Updates |

22 |

31.0% |

|

Presentation of Original Research |

21 |

29.6% |

|

Journal Club |

12 |

16.9% |

|

Case Based Discussion |

5 |

7.0% |

|

OSCE practice |

4 |

5.6% |

|

Others* |

2 |

2.8% |

|

Audit |

2 |

2.8% |

|

Workshops |

3 |

3.0% |

|

Total |

71 |

100% |

|

*Others: ST Sharing of Overseas Experiences and Trainee Wellbeing |

||

Table 3. Type of CME presentations

Figure 2. Graph showing the percentage coverage of knowledge areas

IV. DISCUSSION

Our audit revealed a relatively low coverage of the MRCOG KAs with only 64.9% of the syllabus covered. While the morning CME programme caters to all members of the department, the sessions are an important didactic component for ST education and exam preparation as they are deemed “protected” teaching time. There had been no prior formal review assessing whether it catered to this very important section of the department’s workforce. We were also able to recognise those KAs which had exceptionally low coverage were those with a large amount of practical and “hands-on” skills (i.e. “Gynaecological Problems”, “Management of Labour”, “Management of Delivery”, and “Postpartum Problems”). As a surgical discipline, this highlighted that these areas needed directed solutions through other forms of practical instruction and evaluation. In the pandemic environment, this may involve virtual or home-based means (Hoopes et al., 2020). These “hands-on” KAs likely require at least semi-annual individualised assessment by the CF through verified case logs, Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills, Direct Observation of Procedural Skills, and Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS) (Bisson et al., 2006; Parry-Smith et al., 2014). This targeted assessment was even more crucial during the recovery “catch-up” phase due to de-skilling because of reduced elective surgical caseload (Amparore et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2020) and facilitated the redistributing of surgical training material to cover training deficits.

While there is significant literature on how to organise a robust PG didactic programme (Colman et al., 2020; Harden, 2001; Willett, 2008), little has been published on how to evaluate an established didactic programme’s coverage of its learner’s educational requirements (Davies, 1981). Most studies evaluating the efficacy of such programmes typically assess the effects of individual CME sessions on physician knowledge or performance and patient outcomes after a suitable interval (Davis et al., 1992; Mansouri & Lockyer, 2007), with most citing a small to medium effect. We believe, however, that our audit process permits a more holistic, reproducible, and structured means of evaluating an existing didactic programme and finding deficits that can be improve upon to brings value to any specialty training programme.

At our institution, safe distancing requirements brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic required a rapid transition to a video-conferencing-based approach i.e. vCME. As milestone examinations were still being held, the first six months were primarily focused on STs as examination preparation remained a high and undisputed priority and learning opportunities had been significantly disrupted by the pandemic. During this phase, our vCME programme was re-organised into three to four sessions per week which were peer-led and supervised by a faculty member. Video-conferencing platforms encouraged audience participation through live feedback, questions posed via the chat box, instantaneous online polling, and directed case-based discussions with ST participants. These facilitated real time feedback to the presenter in a way that was not possible in previous face-to-face sessions due to reasons such as shyness and difficulty conducting polls. Other useful features included being able to record presentations for digital storage in a hospital-based server for access on-demand for revision purposes by STs.

A previously published anonymised questionnaire within our department (Chan et al., 2020) found very favourable opinions of vCME as an effective mode of learning amongst 28 junior doctors (85.7%) and nine presenters (100%) with 75% hoping for it to continue even after normalisation of social distancing policies. Nevertheless, common issues reported included a lack of personal interaction, difficulties in engaging with speakers, technical difficulties, and inaccurate attendance confirmation as shared devices for participating on these vCME sessions sometimes failed to identify who was present. While there is altered teacher and learner engagement due to physical separation across a digital medium, studies have also found that the virtual platform provided a useful means of communication and feedback and created a psychologically safe learning environment (Dong et al., 2021; Wasfy et al., 2021).

While our audit focused primarily on STs, departmental CME programmes need to find balanced in catering to the educational outcome of various groups of participants within a clinical department (e.g. senior clinicians, nursing staff, allied healthcare professionals, clinical scientists). Indeed, as these groups started to return to the CME programme after about six months following the vCME transition, we created a core postgraduate committee comprising members representing the learning interests of each party i.e. Department research director, ST Programme Director and Assistant Director, and a representative senior ST in the fifth or sixth year of training, so that we could continue to meet the recommendations set in our TNA while rebalancing the programme to meet the needs of all participants. Out of an average of 20 CME sessions per month, four were dedicated to departmental and hospital grand rounds each. Of the remaining 12 sessions, two were dedicated towards covering KAs, four scientific presentations, three clinical governance aspects, and one journal club. The remaining two sessions would be “faculty wildcard” sessions to be used at the committee’s discretion of the committee to cover poorly covered, more contemporary, “breaking news” topics, or serve as a buffer in the event of cancellations of other topics. Indeed, the same TNA-based audit methodology can be employed any other group of CME participants.

A key limitation in our audit method is that it focused on the breadth of coverage of learning objectives, but not the quality of the teaching and its depth. Teaching efficacy is also important in the delivery of learning objectives (Bakar et al., 2012) and needs more specific assessment tools (Metheny et al., 2005). Evaluating the quality of PG training could take several forms and may be direct e.g. an evaluation by the learner (Gillan et al., 2011), or could be indirect e.g. charting the learner’s progress through OSCEs and CEXs, scheduled competency reviews, and ST examination pass rates (Pinnell et al., 2021). Importantly, despite the rise of virtual learning platforms, there is little consensus on the best way to evaluate e-learning methods (De Leeuw et al., 2019). Nevertheless, our main audit goal was to assess the extent of coverage of the MRCOG syllabus which is a key training outcome. Future audits, however, should incorporate this element to provide additional qualitative feedback to assess this dimension as well. Further research should be carried out in terms of evaluating the effects of optimising a PG didactic programme on key outcomes such as ST behaviour, perceptions, and objective outcomes such as examination results.

Finally, while these were the results of an audit conducted in a single hospital department and used a morning CME programme as a basis for evaluation, we believe that this audit methodology based on a ten-step TNA and also utilising the Delphi method and syllabus mapping techniques (Harden, 2001) can be reproduced to any academic department that has a regular didactic programme as long as a suitable standard is selected. The Delphi method can easily be conducted via online survey platforms (e.g. Google Forms) to crystallise the PG programme goals. Our audit shows that without a systematic evaluation of past didactic sessions, it is possible for even mature CME programme to fall significantly short of ameeting the needs of its learners and that PG didactic sessions need deliberate planning.

V. CONCLUSION

Just as any other aspect of healthcare delivery, CME and PG programmes are amenable to audits and must adjust to an ever-changing delivery landscape. Rather than curse the darkness during the COVID-19 pandemic, we explored the potential of reformatting the PG programme and adjusting course to better suit the needs of our STs. We demonstrate a method of auditing an existing programme, distilling important learning goals, comparing it against an appropriate standard (i.e. coverage of the MRCOG KAs), and implementing changes utilising reproducible techniques such as the Delphi method (Humphrey-Murto et al., 2017). This process should be a regular mainstay of any mature ST programme to ensure continued relevancy. As continual outbreaks, even amongst vaccinated populations (Amit et al., 2021; Bar-On et al., 2021; Bergwerk et al., 2021) auger a future of COVID-19 endemicity, we must accept a “new-normal” comprising of intermittent workplace infection control policies such as segregation, shift work, and restrictions for in-person meetings (Kwon et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020). Through our experience, we have shown that this auditing methodology can also be applied to vCME programmes.

Notes on Contributors

Rachel Jiayu Lee participated in the data collection and review, the writing of the paper, and the formatting for publication.

Jeannie Jing Yi Yap participated in the data collection and review, the writing of the paper, and the formatting for publication.

Carly Yanlin Wu participated in data collection and review.

Grace Chan Ming Fen participated in data collection and review.

Abhiram Kanneganti was involved in the writing of the paper, editing, and formatting for publication. Citra Nurfarah Zaini Mattar participated in the editing and direction of the paper.

Pearl Shuang Ye Tong participated in the editing and direction of the paper.

Susan Jane Sinclair Logan participated in the editing and direction of the paper.

Ethical Approval

IRB approval for waiver of consent (National Healthcare Group DSRB 2020/00360) was obtained for the questionnaire assessing attitudes towards vCME.

Data Availability

There is no relevant data available for sharing in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the roles of Mr Xiu Cai Wong Edwin, Mr Lee Boon Kai and Ms Teo Xin Yue in the administrative roles behind auditing and reformatting the PG medical education programme.

Funding

There was no funding for this article.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

References

Amit, S., Beni, S. A., Biber, A., Grinberg, A., Leshem, E., & Regev-Yochay, G. (2021). Postvaccination COVID-19 among healthcare workers, Israel. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(4), 1220. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2704.210016

Amparore, D., Claps, F., Cacciamani, G. E., Esperto, F., Fiori, C., Liguori, G., Serni, S., Trombetta, C., Carini, M., Porpiglia, F., Checcucci, E., & Campi, R. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urology residency training in Italy. Minerva Urologica e Nefrologica, 72(4), 505-509. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0393-2249.20.03868-0

Bakar, A. R., Mohamed, S., & Zakaria, N. S. (2012). They are trained to teach, but how confident are they? A study of student teachers’ sense of efficacy. Journal of Social Sciences, 8(4), 497-504. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2012.497.504

Bar-On, Y. M., Goldberg, Y., Mandel, M., Bodenheimer, O., Freedman, L., Kalkstein, N., Mizrahi, B., Alroy-Preis, S., Ash, N., Milo, R., & Huppert, A. (2021). Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(15), 1393-1400. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2114255

Bergwerk, M., Gonen, T., Lustig, Y., Amit, S., Lipsitch, M., Cohen, C., Mandelboim, M., Levin, E. G., Rubin, C., Indenbaum, V., Tal, I., Zavitan, M., Zuckerman, N., Bar-Chaim, A., Kreiss, Y., & Regev-Yochay, G. (2021). Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(16), 1474-1484. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2109072

Bienstock, J., & Heuer, A. (2022). A review on the evolution of simulation-based training to help build a safer future. Medicine, 101(25), Article e29503. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029503

Bisson, D. L., Hyde, J. P., & Mears, J. E. (2006). Assessing practical skills in obstetrics and gynaecology: Educational issues and practical implications. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, 8(2), 107-112. https://doi.org/10.1576/toag.8.2.107.27230

Bryant‐Smith, A., Rymer, J., Holland, T., & Brincat, M. (2019). ‘Perfect practice makes perfect’: The role of laparoscopic simulation training in modern gynaecological training. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, 22(1), 69-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/tog.12619

Burr, R., & Johanson, R. (1998). Continuing medical education: An opportunity for bringing about change in clinical practice. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 105(9), 940-945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10255.x

Chan, G. M. F., Kanneganti, A., Yasin, N., Ismail-Pratt, I., & Logan, S. J. S. (2020). Well-being, obstetrics and gynaecology and COVID-19: Leaving no trainee behind. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 60(6), 983-986. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13249

Chick, R. C., Clifton, G. T., Peace, K. M., Propper, B. W., Hale, D. F., Alseidi, A. A., & Vreeland, T. J. (2020). Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(4), 729-732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Colman, S., Wong, L., Wong, A. H. C., Agrawal, S., Darani, S. A., Beder, M., Sharpe, K., & Soklaridis, S. (2020). Curriculum mapping: an innovative approach to mapping the didactic lecture series at the University of Toronto postgraduate psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry, 44(3), 335-339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-020-01186-0

Davies, I. J. T. (1981). The assessment of continuing medical education. Scottish Medical Journal, 26(2), 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/003693308102600208

Davis, D. A., Thomson, M. A., Oxman, A. D., & Haynes, R. B. (1992). Evidence for the effectiveness of CME: A Rreview of 50 randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association, 268(9), 1111-1117. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03490090053014

De Leeuw, R., De Soet, A., Van Der Horst, S., Walsh, K., Westerman, M., & Scheele, F. (2019). How we evaluate postgraduate medical e-learning: systematic review. JMIR medical education, 5(1), e13128.

Dong, C., Lee, D. W.-C., & Aw, D. C.-W. (2021). Tips for medical educators on how to conduct effective online teaching in times of social distancing. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 30(1), 59-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/2010105820943907

Donovan, P., & Townsend, J. (2019). Learning Needs Analysis. Management Pocketbooks.

English, W., Vulliamy, P., Banerjee, S., & Arya, S. (2020). Surgical training during the COVID-19 pandemic – The cloud with a silver lining? British Journal of Surgery, 107(9), e343-e344. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11801

Forsetlund, L., O’Brien, M. A., Forsén, L., Mwai, L., Reinar, L. M., Okwen, M. P., Horsley, T., & Rose, C. J. (2021). Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(9), CD003030. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub3

Gillan, C., Lovrics, E., Halpern, E., Wiljer, D., & Harnett, N. (2011). The evaluation of learner outcomes in interprofessional continuing education: A literature review and an analysis of survey instruments. Medical Teacher, 33(9), e461-e470. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.587915

Gould, D., Kelly, D., White, I., & Chidgey, J. (2004). Training needs analysis. A literature review and reappraisal. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(5), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.12.003

Grafton-Clarke, C., Uraiby, H., Gordon, M., Clarke, N., Rees, E., Park, S., Pammi, M., Alston, S., Khamees, D., Peterson, W., Stojan, J., Pawlik, C., Hider, A., & Daniel, M. (2022). Pivot to online learning for adapting or continuing workplace-based clinical learning in medical education following the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 70. Medical Teacher, 44(3), 227-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1992372

Harden, R. M. (2001). AMEE Guide No. 21: Curriculum mapping: A tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Medical Teacher, 23(2), 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590120036547

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008-1015. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x

Hicks, C., & Hennessy, D. (1996). Applying psychometric principles to the development of a training needs analysis questionnaire for use with health visitors, district and practice nurses. NT Research, 1(6), 442-454. https://doi.org/10.1177/174498719600100608

Hicks, C., & Hennessy, D. (1997). The use of a customized training needs analysis tool for nurse practitioner development. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(2), 389-398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.199702 6389.x