Preclinical medical student satisfaction of Team-based learning in Chiang Mai University

Submitted: 9 February 2023

Accepted: 22 March 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 36-39

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/SC3000

Komson Wannasai1, Wisanu Rottuntikarn1, Atiporn Sae-ung2, Kwankamol Limsopatham2, Wiyada Dankai1

1Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Abstract

Introduction: Global medical and healthcare education systems are increasingly adopting team-based learning (TBL). TBL is an interactive teaching programme for improving the performance, clinical knowledge, and communication skills of students. The aim of this study is to report the learning experience and satisfaction of participants with the TBL programme in the preclinical years of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University.

Methods: Following the implementation of TBL in the academic year 2022, we asked 387 preclinical medical students, consisting of 222 Year 2 and 165 Year 3 medical students who attended the TBL class to voluntarily complete a self-assessment survey.

Results: Overall, 95.35% of the students were satisfied with the structure of the TBL course and agreed to attend the next TBL class. The overall satisfaction score was also high (4.44 ± 0.627). In addition, the students strongly agreed that the TBL programme improved their communication skills (4.50 ± 0.796), learning improvement (4.41 ± 0.781), and enthusiasm for learning (4.46 ± 0.795).

Conclusion: The survey findings indicated that students valued TBL-based learning since it enabled them to collaborate and embrace learning while perhaps enhancing their study abilities. However, since this is a pilot study, further investigations are warranted.

Keywords: Team-based Learning, Small Group Interaction, Medical Education, Implementation

I. INTRODUCTION

Team-based learning (TBL) is a form of small-group teaching which can improve student performance, clinical knowledge, and communication skills. It has been employed in medical and healthcare education in the US, Australia, Austria, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore (Burgess et al., 2014; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). Since 2000s, this model has been used in medical education to foster deep learning across a variety of subjects and educational contexts, benefiting teachers and helping academically weak and strong students achieve the same or better results than with conventional methods (Parmelee et al., 2012). In addition, it is more effective for engaging students than lecturing in a large class with few teachers (Burgess et al., 2020b).

The key elements of TBL include pre-class preparation to encourage self-study, teamwork, and instant feedback. These key elements promote active learning and critical thinking (Burgess et al., 2020a; Parmelee et al., 2012). The steps in TBL include pre-class preparation, individual readiness assurance test (iRAT), team readiness assurance test (tRAT), feedback, and team application (Burgess et al., 2014). In the tRAT and team application phase, students work in small groups to demonstrate the use of teamwork for problem-solving. Clinical problem-solving exercises by students lead to class discussions and instructor comments (Burgess et al., 2020a; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). The teacher’s feedback can help clarify students’ responses by discussing their answers. In the academic year 2022, TBL was implemented on second- and third-year medical students in the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, and self-assessment questionnaires were used to assess students’ satisfaction with the TBL model. This research aims to examine the impact of team-based learning on whether or not students were able to build their own learning processes, as well as to measure student satisfaction with teaching and learning in the TBL paradigm in order to improve further TBL classrooms in the faculty.

II. METHODS

A. Sampling and Participants

In 2022, 387 pre-clinic medical students from Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Medicine were studied (222 from Year 2 and 165 from Year 3). Year 2 medical students studied human skin and the connective tissue system, while Year 3 medical students studied human haematology. Each TBL class consisted of 50 teams of mixed-gender and grades. Each team contained five members.

B. Structure and Components of TBL

The TBL programme was first implemented in the 2022 academic year, covering preclinical academic Years 2 and 3 at the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. The TBL structure comprised two major phases: pre-class and in-class. The TBL topics included automated haematology and venomous snakes for Year 3 medical students. The skin infection topic was selected for Year 2 medical students.

After TBL, the non-researcher academic team informed medical students about the study and sought volunteers to avoid a conflict of interest between the instructors and the medical students. The non-researchers urged students interested in the experiment to complete a Google Forms questionnaire outlining the study’s relevance, including an explanation of the topic, data gathering, and the pros and cons of participation. If participants agreed to answer the questionnaire, they could complete the Google Form to consent and submit the questionnaire, with their personal information remaining anonymous.

For validity, a questionnaire to explore students’ views on TBL was prepared via a literature study, student review (two students), peer review (faculty members from two departments), and expert opinion (a TBL expert). It also examined students’ perceptions of teams and their beliefs and values in collaboration. The outcomes of the different years of student were then compared.

C. Data Collection and Analysis

Upon completing the TBL class, participant students were invited to voluntarily take the self-assessment survey to explore their thoughts on the assertions made in the TBL literature. The questionnaire was in Thai and we used a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly dissatisfied, 2 = unsatisfied, 3 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4 = satisfied, 5 = strongly satisfied). Students were asked about the preparation for the TBL class, including student material, classroom, teaching content, self-preparation, orientation programme, class material, and the overall programme. The self-assessment survey also asked about promoting self-understanding, including communication skills, learning improvement, and enthusiasm in learning using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

The TBL self-assessment survey data were analysed according to mean and standard deviation (SD) using STATA version 16 (STATA Corp., Texas, USA). The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to analyze the difference between second- and third-year medical students’ percentages of satisfaction or agreement in each aspect. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. The reliability of the questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha.

III. RESULTS

In years 2 and 3, Cronbach’s alpha of the medical students’ questionnaire was 0.869. In total, 369/387 (95.35%) participants appreciated the course structure and agreed to attend the next TBL session. Students rated the TBL class 4.44 ± 0.627 on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 being severely dissatisfied and 5 very pleased. Students also liked the classroom (4.48 ± 0.738), TBL structure (4.41 ± 0.771), and self-preparation (4.28 ± 0.780). The orientation programme, instructional material, pre-recorded video, and handouts were also well-received. Most students (69.25%, 268/387) spent 1–2 days self-preparing before the TBL class, followed by 3–4 days (24.55%, 95/387) and 5–7 days (5.43%, 21/387), while 0.78% (3/387) did not self-prepare.

On a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 5, students assessed their self-understanding progress, stating that TBL increased their communication, learning, and enthusiasm (4.50 ± 0.796, 4.41 ± 0.781, 4.46 ± 0.795).

The student t-tests revealed no significant differences between students in years 2 and 3. Except time for preparation (Pearson’s Chi-square test; p < 0.005), medical students in years 2 and 3 had similar self-assessment survey scores. In addition, Year 3 medical students also scored better in enthusiasm for studying than Year 2 medical students in increasing self-understanding (Student t-test; p = 0.023) (Table 1).

|

|

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

p-value |

|

Student satisfaction towards the TBL class |

|||

|

Agree to attend the next TBL class: % (n) |

95.95% (213/222) |

94.55% (156/165) |

0.519 |

|

Classroom: mean (SD) |

4.49 (0.671) |

4.47 (0.823) |

0.903 |

|

TBL structure: mean (SD) |

4.38 (0.73) |

4.45 (0.822) |

0.377 |

|

Orientation programme: mean (SD) |

4.46 (0.628) |

4.40 (0.810) |

0.417 |

|

Teaching material: mean (SD) |

4.67 (0.568) |

4.56 (0.578) |

0.064 |

|

Student preparation time: mean (SD) |

4.20 (0.788) |

4.40 (0.755) |

0.012 |

|

Time for preparation: % (n) 1–2 days 3–4 days 5–7 days No preparation |

80.18% (178/222) 14.41% (32/222) 4.50% (10/222) 0.90% (2/222) |

54.55% (90/165) 38.18% (63/165) 6.67% (11/165) 0.61% (1/165) |

< 0.005 |

|

Promotion of learning skills |

|||

|

Communication skills: mean (SD) |

4.46 (0.734) |

4.56 (0.674) |

0.154 |

|

Understanding of the topics: mean (SD) |

4.36 (0.729) |

4.47 (0.845) |

0.180 |

|

Enthusiasm for learning: mean (SD) |

4.38 (0.797) |

4.56 (0.783) |

0.023 |

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0.869 |

0.869 |

|

Table 1. Comparison between the satisfaction of medical students in years 2 and 3 towards the TBL class and agreement to the promotion of self-understanding

IV. DISCUSSION

TBL changes how students learn by encouraging them to become more accountable by preparing for the team assurance test and application exercise (Burgess et al., 2020a). Teacher-directed pre-class preparation for advanced tasks may involve reading textbooks, reference articles, or instructor-created material while the readiness assurance test enhances students’ enthusiasm for TBL (Parmelee et al., 2012). However, students may resist TBL or active learning because it varies from passive lecture-based learning. Teachers must be aware of this and advocate TBL-style learning to improve ability and encourage students to be more prepared. This research examines the attitudes of medical students towards the two courses post-TBL and provides valuable input on TBL strategies, regardless of the course schedule.

Student feedback can improve teaching and student satisfaction. Students agreed that TBL can improve communication, learning, and passion. Second-year medical students were less motivated than third-year (p = 0.023), implying they need to focus on the core content of the preclinical module rather than TBL preparation, while third years have more time management experience for pre-class self-study. Students liked the teaching material because, in addition to textbooks, the instructors prepared PowerPoint presentations, recorded VDOs, and documentation, allowing those with different learning styles to make the appropriate choice.

Interestingly, both classes found the TBL structure and location less satisfying, possibly because first-time students could not comprehend group activities. Students can further grasp the TBL framework and enjoy the structured process with a revamped instructional layout and additional classes. As for the classroom, the seat layout may prevent suitable group conversations, with a small-group or smart classroom being more appropriate for TBL.

The preparation time satisfaction results are significantly difference, with Year 2 students being considerably less satisfied than Year 3 (p = 0.012). Most second-year medical students spent one to two days planning, and third years one to four (p = 0.005), primarily because the third-year course was longer. Second-year medical students attended a two-week course on human skin and the connective tissue system with a TBL class in the second week, whereas third years took a five-week haematological system course with a TBL class in the fourth week. Both classes received course material on Mondays, while the TBL was on Fridays in the same week. Second-year medical students may need to study the basic science aspects and be unable to independently assess the pre-class material, whereas third-year students had more time. Accordingly, a TBL course should last at least three to four weeks to allow medical students to understand the basic TBL instructional material and independently assess it.

This study has limitations. The questionnaire was expert-evaluated without instructor facilitation. In addition, our study focused on students’ satisfaction with TBL, hence we didn’t include academic outcomes to prove the value of TBL.

V. CONCLUSION

The survey showed that students appreciated TBL-based learning since it helped them to work together and embrace learning, while potentially improving their study skills. A diversity of pre-class material allows students to choose learning tactics depending on their individual abilities. Students found the activity venue inadequate and classroom improvements would boost their satisfaction level.

Notes on Contributors

KW reviewed the literature, designed the study, analysed data, co-wrote the manuscript, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, and then read it through prior to final approval.

WD reviewed the literature, analysed the data, co-wrote the manuscript, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

WR gave critical feedback on the writing of the manuscript.

AS and KL provided scientific insight and advice, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This research was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Chiang Mai University (Study code: PAT-2565-09243).

Data Availability

On reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide data to support the conclusions of this study. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the data cannot be made public.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to express their sincere appreciation to Ms. Naorn Sriwangdang for assisting with the preparation of the research proposal.

Funding

This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, grant no. 062-2566.

Declaration of Interest

The authors confirm they have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Burgess, A., Bleasel, J., Hickson, J., Guler, C., Kalman, E., & Haq, I. (2020a). Team-based learning replaces problem-based learning at a large medical school. BMC Medical Education, 20, Article 492. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02362-4

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., Roberts, C., & Mellis, C. (2020b). Team-based learning: Design, facilitation and participation. BMC Medical Education, 20(Suppl 2), Article 461. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02287-y

Burgess, A. W., McGregor, D. M., & Mellis, C. M. (2014). Applying established guidelines to team-based learning programs in medical schools: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 678–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000162

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(116), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.330

Parmelee, D., Michaelsen, L. K., Cook, S., & Hudes, P. D. (2012). Team-based learning: A practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. Medical Teacher, 34(5), e275–e287. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179

*Komson Wannasai

Department of Pathology,

Faculty of Medicine,

Chiang Mai University,

110 Inthavaroros road, Sriphume

Meaung, Chiang Mai, 50200

+6653935442

Email: komson.wanna@gmail.com

Submitted: 9 February 2023

Accepted: 15 May 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 23-35

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/OA3006

Sethapong Lertsakulbunlue1, Kaophiphat Thammasoon2, Kanlaya Jongcherdchootrakul3, Boonsub Sakboonyarat3 & Anupong Kantiwong1

1Department of Pharmacology, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Thailand; 2Department of Personnel Administration Division, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Thailand; 3Department of Military and Community Medicine, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Thailand

Abstract

Introduction: Although medical research (MR) is constantly promoted, a global deficit of medical researchers has been noted. We aimed to explore the relationship among practice, perceptions, attitudes, barriers and motivation toward MR and its impacts on MR publication.

Methods: A cross-sectional study included 262 senior medical students and interns. An electronic, standardised Likert scale questionnaire was used to collect the data. Binary logistic regression was used to determine the odds ratio between characteristics and MR publication. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to confirm the loading factor of each question, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to investigate the relationship between latent variables and MR publication.

Results: Cronbach’s alpha revealed a good internal reliability of 0.93. The accumulated grade point average did not differ between those who had published and those who had not. MR presentations were strongly associated with MR publication. SEM showed that attitudes (0.71, p<0.001) and perceptions (0.27, p<0.001) had a direct effect on practices. Practices (0.49, p<0.001) and attitudes (0.30, p<0.001) had a direct effect on motivation, while motivation had a total effect = 0.36, p<0.001 on MR publication through MR presentation as a mediator.

Conclusion: Positive attitudes and perceptions might lead to positivity in the intention to practice MR, which would lead to motivation and finally increase the odds of MR publication. Different approaches to promote excitement and perceptions in MR learning should be encouraged by teachers and faculty members.

Keywords: Medical Research, Students, Perceptions, Attitudes, Barriers, Motivation

Practice Highlights

- Enjoyment and excitement should be promoted while learning medical research.

- Medical research experiences enhanced publication, particularly medical research presentations.

- Extracurricular medical research activities should be routinely promoted.

- Facilitators in medical research might be tailor-made for each individual.

- Regular meetings regarding medical research with mentors or role models should be held.

I. INTRODUCTION

Health-related research is constantly promoted and has gained great importance over time (Sobczuk et al., 2022). However, a global shortage of medical researchers was noted despite an increasing demand for them (Funston et al., 2016). For example, in the US, the proportion of medical researchers has declined from approximately 4.7% to 1.5% in the 1980s and 2014, respectively (Carberry et al., 2021; Davila, 2016; Puljak, 2007). Several barriers toward conducting medical research (MR) have been reported among undergrads and postgraduates. For instance, lack of allotted time, lack of physician engagement in research early during medical students’ training, and lack of mentoring and guidance (Bonilla-Escobar et al., 2017; El Achi et al., 2020; Habineza et al., 2019; Okoduwa et al., 2018). To resolve these problems, medical education has globally incorporated research methods and epidemiology into its curriculum (Carberry et al., 2021). Nevertheless, only a minority of medical students had reached the primary goal of research, namely publishing (Bonilla-Escobar et al., 2017; Carberry et al., 2021; Laidlaw et al., 2012).

Factors associated with MR publication have been identified. Students from highly ranked undergraduate institutions were more likely to achieve publication. Mentors also played an important role in increasing the likelihood of publication. For example, a student working with a mentor with a PhD degree or a mentor with prior publication(s) with prior mentee(s) increases the chance of achieving publication (Parker et al., 2021). Medical students participating in an extracurricular scientific activity, such as the Scientific Society of Medical Students, or who take a scientific writing skills course, were also associated with greater odds of producing a scientific publication (Valladares-Garrido et al., 2022).

One of the main reasons researchers conduct a study is because of what they believe (Lev et al., 2010). Attitudes toward and barriers against health research influence research success (Lev et al., 2010; Memarpour et al., 2015; Osman, 2016). Attitudes and motivations toward a particular type of study also showed a positive relationship with achievement (Ma & Xu, 2004; Özer, 2020; Simpson & Oliver, 1990). Furthermore, a theory of success describes perception leading to passion, and the continuation of passion leading to obsession, which drives an individual to succeed (Dange, 2016; Schellenberg et al., 2022).

Previously, several studies reported descriptive data on attitudes, practices, knowledge levels, perceptions, motivation and barriers involving research among medical and science students (AlGhamdi et al., 2014; Al-Shalawy & Haleem, 2015; Arif et al., 2018; El Achi et al., 2020; Habineza et al., 2019; Memarpour et al., 2015; Osman, 2016; Pallamparthy & Basavareddy, 2019). Even though these factors are known to affect one’s behaviour, to our knowledge, research on whether these factors are associated with research publications among medical students is scarce.

Without research, no breakthroughs can be achieved in managing disease. Therefore, strategies to enhance medical students’ appreciation of research and publication should be promoted. As a step toward this goal, our study aimed to determine the relations between MR practices, perceptions, attitudes, barriers and motivation toward medical research and their effect on MR publications among senior medical students and internists graduated from Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Thailand. Furthermore, we also explore the differences in the characteristics and MR experiences of the participants between the publishing group and the non-publishing group. The goal involved influencing future research and actions to increase research publications among physicians in the country and contribute to medical practices.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design and Subjects

A cross-sectional study based on a self-administered survey was conducted at Phramongkutklao College of Medicine (PCM), Bangkok, Thailand. The survey was distributed among senior medical students, including fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-year students and internists who graduated from PCM. The total number of senior medical students and internists was 292 and approximately 250 interns, respectively. The curriculum at PCM is spread out over six years, with the first three being pre-clinical years spent studying basic science and the last three being clinical years spent developing clinical experiences. An introductory module about MR is mandatory in three years of the curriculum in the third, fourth, and sixth years of medical school. Firstly, third-year medical students learn the basics of MR, such as basic study designs focusing on quantitative methods, data analysis, and research proposal development. Furthermore, students learn about public health aspects, including community participation. Secondly, fourth-year medical students learn more about advanced study designs and are more focused on conducting a study and multivariate analysis. Fourth-year students were divided into eight groups of approximately twelve to conduct a community-based research proposal before finalizing their project as a report. Finally, sixth-year medical students were divided into pairs or a group of three to conduct medical research to improve medical care in a community hospital setting. Then the research is presented, and a manuscript report is submitted. However, an MR publication was not mandatory. After they graduated, the students were sent to both Thai Army hospitals and government hospitals run by the Ministry of Public Health to work as interns.

The present study included senior medical students and internists due to their similar MR experiences. First, both groups were enrolled within the same curriculum paradigm. Second, the MR presentation and publications are according to the willingness of the student, as MR publications and presentations are not mundane. Finally, almost all the published research among the population is from projects developed during their fourth and sixth years as medical students. Therefore, several projects were published during the internship.

B. Data Collection

We used an electronic standardised questionnaire, including six parts: short answer questions for obtaining demographic data; a 5-score Likert scale questionnaire on practice, perceptions, attitudes, barriers, and motivation toward MR. The questionnaire was translated using related published work that is relevant to this paper, as well as the investigators’ experience and context of PCM (El Achi et al., 2020; Funston et al., 2016; Habineza et al., 2019; Ichsan et al., 2018; Kamwendo, 2002; Okoduwa et al., 2018; Pallamparthy & Basavareddy, 2019). In addition, five expert professors examinedthe content validity and reliability of the questionnaire; pilot testing was conducted among 66 first year medical students and Cronbach’s alpha score ranged from 0.74-0.93.Then the questionnaire was launched in November and December of 2022 as a Google Form and advertised via social media to the study population. Information sheets, objectives, and methods of the study were provided on the first page of the Google Form, which participants were asked to read carefully before agreeing to participate. The questionnaire was then self-completed and took, on average, about 10–15 minutes to complete. The finalised Cronbach’s alphas were 0.83, 0.84, 0.74, 0.89, 0.88, and 0.93 for practices, perceptions, attitudes, barriers, motivation and overall questions, respectively.

Practice was defined as their willingness or intention to practice MR (El Achi et al., 2020). Perceptions are how the student perceives the importance of MR, while attitude is how they feel about conducting MR (El Achi et al., 2020; Funston et al., 2016). Barriers are defined as what the students perceive as being resistant to conducting MR; on the other hand, motivations are what they perceive as facilitating conducting MR (Habineza et al., 2019; Okoduwa et al., 2018).

C. Statistical Analysis

All data were downloaded from Google Forms, and data analyses were performed using StataCorp, 2021, Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. A frequency distribution of demographic characteristics was performed to describe the study subjects. Categorical data were presented as percentages, and continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of the association between the characteristics and MR experiences of the participants and the MR publication. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The structural equation modeling (SEM) using maximum likelihood extraction was done to find out how the latent variables, including practice, perceptions, attitudes, barriers, and motivation, were related and what effect it had on MR publications. The procedure is comprised of two steps. The first is validating the measurement model, which is carried out primarily using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the other is fitting the structural model, which is achieved primarily through path analysis of latent variables. CFA was applied to demonstrate the impact of each question (observed variable) on different beliefs toward MR (latent variable) and presented as a lambda. Questions with a low factor loading (below 0.60) were excluded from the SEM. During the SEM construction, questions with factor loadings below 0.60 were also removed. In the final model, there are 17 observed variables included within the SEM. The samples/observed variable were 15.41, which is more than 10, indicating adequate sample size for SEM (Wolf et al., 2013). The SEM was carried out to investigate the relationship among latent variables and their impact on MR publication in our study population.The six following indices were used to evaluate model fit: (1) the chi-square test, χ2; (2) the chi-square test over degree of freedom (df), χ2/df (3) the comparative fit index, CFI; (4) the Tucker–Lewis index, TLI (5) the root-mean square error of approximation, RMSEA; and (6) the root-mean square residual, (SRMR). All these indices indicated a proposed fit for SEM data. A χ2/df lower than 2, CFI greater than 0.95, TLI greater than 0.95, RMSEA less than 0.06 and SRMR less than 0.06 each indicated a good fit between the data and the hypothesised model.

III. RESULTS

A. Characteristic of Participants

Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of participants stratified by MR publishing. A total of 139 senior medical students and 123 interns participated in the survey. The response rate was 47.6% and 49.2% for senior medical students and interns, respectively. Over one-fifth (22.1%) of the participants had published MR and were mostly internists (81.0%). Approximately 60% of the participants were male, corresponding to an enrolment at PCM of 60 male and 40 female students. The accumulated grade point average (GPAX) was approximately the same at 3.4±0.3 among both published and those who had not published. Regarding, MR experience or roles served during medical student years, being a group leader (AOR: 2.12, 95% CI: 0.97 to 4.64, p=0.06) was associated with MR publishing. Finally, those having experience in MR presentation, whether oral or poster, and international or national presentation, were strongly associated with MR publishing, with adjusted odds ratios of 4.34 (p<0.001) shown in Table 2.

|

Characteristics |

Non-Published |

Published |

|

n (% of 204) |

n (% of 58) |

|

|

Demographics |

||

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

119 (58.3) |

37 (63.8) |

|

Female |

85 (41.7) |

21 (36.2) |

|

Educational level |

||

|

Clinical year |

128 (62.7) |

11 (19.0) |

|

Intern |

76 (37.3) |

47 (81.0) |

|

Accumulated grade point average (GPAX) |

||

|

Mean ± SD |

3.4±0.3 |

3.4±0.3 |

|

Medical research participation |

||

|

MR elective |

59 (28.9) |

15 (25.9) |

|

Time spent on MR (hours/week) |

||

|

<1 |

119 (58.3) |

27 (46.6) |

|

1-5 |

56 (27.5) |

17 (29.3) |

|

5-10 |

15 (7.4) |

7 (12.1) |

|

>10 |

14 (6.9) |

7 (12.0) |

|

Extra curriculum research activity |

39 (19.1) |

23 (39.7) |

|

Academic club activity |

30 (14.7) |

13 (22.4) |

|

MR experience during medical student |

||

|

Group leader |

45 (22.1) |

24 (41.4) |

|

Design MR |

89 (43.6) |

34 (58.6) |

|

Proposal writing |

142 (69.6) |

45 (77.6) |

|

Data enter |

126 (51.5) |

41 (70.7) |

|

Data analysis |

99 (48.5) |

34 (58.6) |

|

Literature review |

125 (61.3) |

42 (72.4) |

|

Manuscript writing |

76 (37.3) |

33 (56.9) |

|

None |

7 (3.4) |

2 (3.4) |

|

National MR presentation |

||

|

Oral presentation |

23 (11.3) |

22 (37.9) |

|

Poster presentation |

22 (10.8) |

22 (37.9) |

|

International MR presentation |

||

|

Oral presentation |

7 (3.4) |

8 (13.8) |

|

Poster presentation |

9 (4.4) |

15 (25.9) |

|

Published national MR |

0 (0) |

29 (50.0) |

|

Published international MR |

0 (0) |

37 (63.8) |

MR: Medical Research

Table 1. Characteristics of participants stratified by medical research publishing experience (N=262)

|

Characteristics |

Non-Published |

Published |

OR |

95% CI |

p-value |

AOR |

95% CI |

p-value |

|

n (% of 204) |

n (% of 58) |

|||||||

|

Sex |

||||||||

|

Male |

119 (58.3) |

37 (63.8) |

ref |

ref |

||||

|

Female |

85 (41.7) |

21 (36.2) |

0.79 |

0.43-1.45 |

0.455 |

0.76 |

0.37-1.56 |

0.458 |

|

Educational level |

||||||||

|

Clinical year |

128 (62.7) |

11 (19.0) |

ref |

ref |

||||

|

Intern |

76 (37.3) |

47 (81.0) |

3.09 |

1.74-5.50 |

<0.001 |

6.67 |

3.12-14.28 |

<0.001 |

|

Accumulated grade point average (GPAX) |

||||||||

|

Mean±SD |

3.4±0.3 |

3.4±0.3 |

1.02 |

0.40-2.59 |

0.971 |

0.417 |

0.12-1.41 |

0.159 |

|

Extra curriculum research activity |

39 (19.1) |

23 (39.7) |

2.78 |

1.48-5.23 |

0.002 |

1.47 |

0.62-3.46 |

0.379 |

|

MR experience during medical student |

||||||||

|

Group Leader |

45 (22.1) |

24 (41.4) |

2.49 |

1.34-4.63 |

0.004 |

2.12 |

0.97-4.64 |

0.060 |

|

MR presentation |

||||||||

|

No |

170 (83.3) |

27 (46.6) |

ref |

ref |

||||

|

Yes |

34 (16.7) |

31 (53.5) |

5.74 |

3.05-10.82 |

<0.001 |

4.34 |

1.99-9.47 |

<0.001 |

MR: Medical Research, OR: Odds Ratio, AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable analysis of characteristics and medical research experiences by medical research publishing experience (N=262)

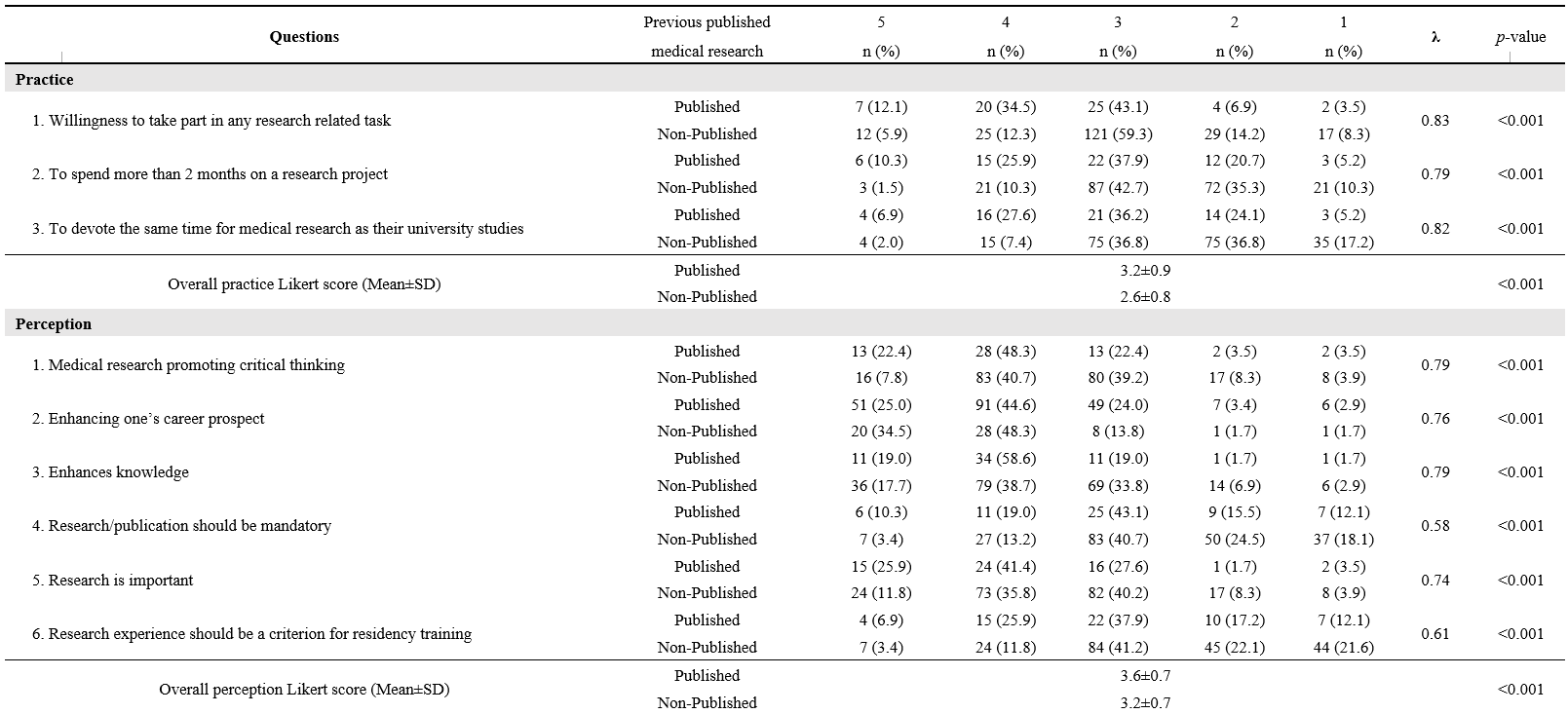

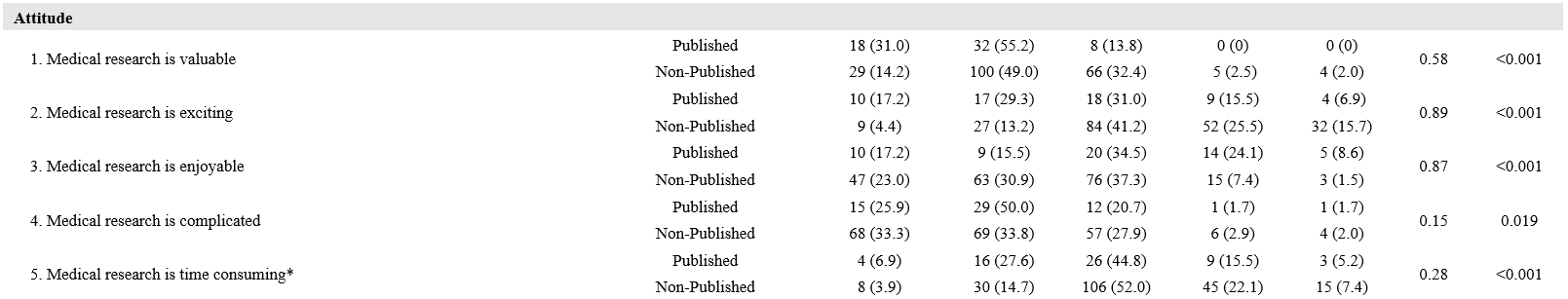

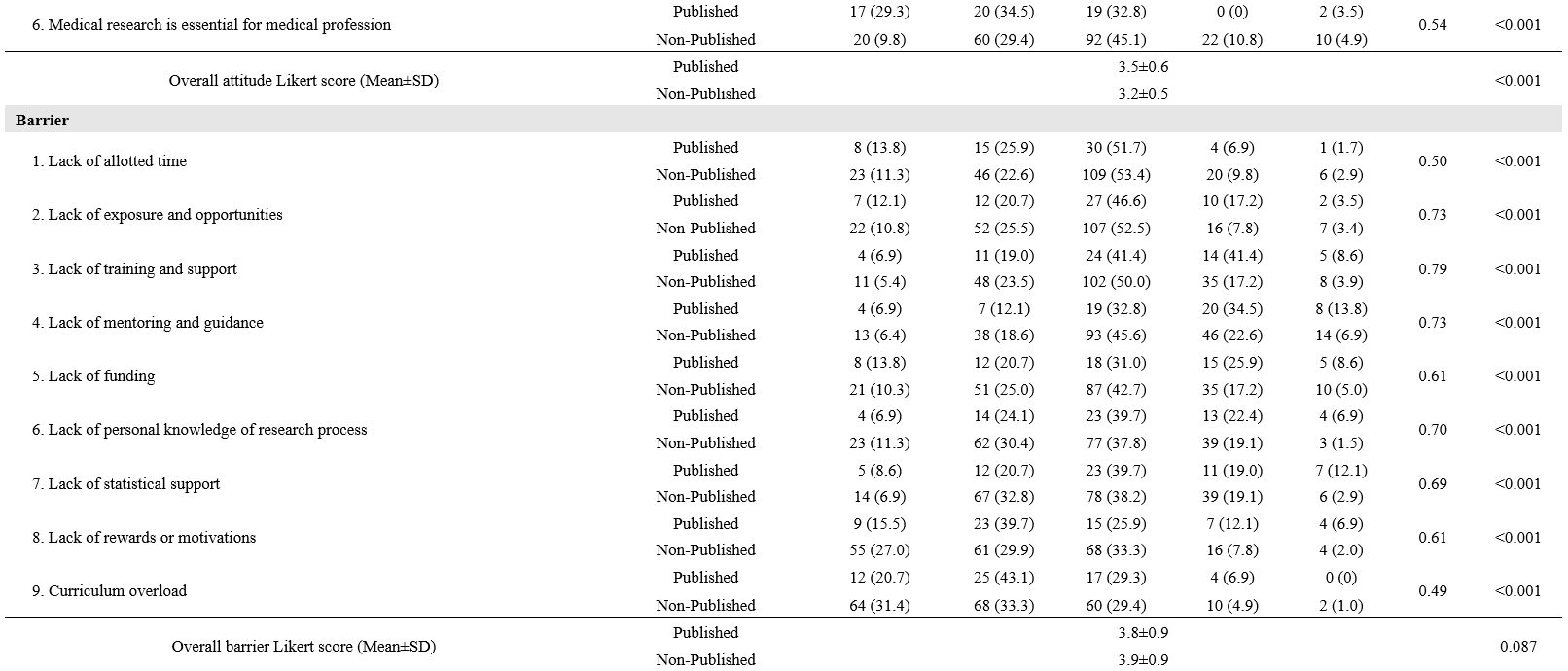

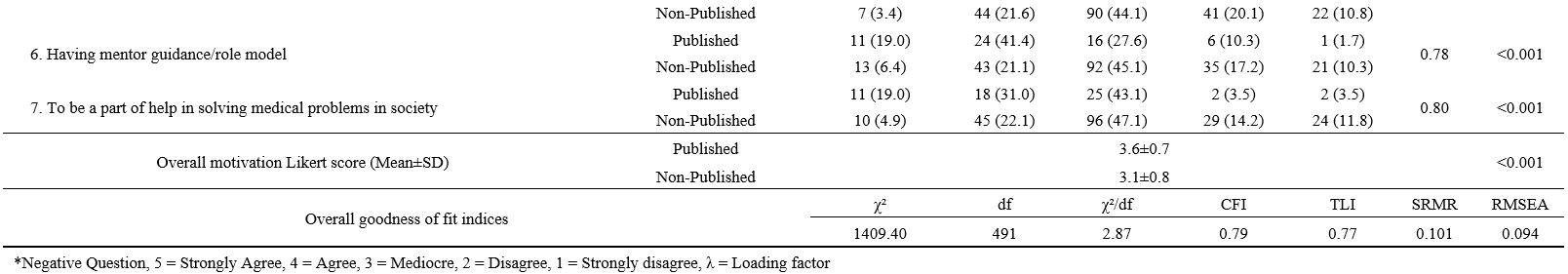

B. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Practices, Perceptions, Attitudes, Barriers and Motivation toward Medical Research

Table 3 demonstrates the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of practices, perceptions, attitudes, barriers and motivation Likert scores and MR publishing experience. In the practice section, all questions had a loading factor of approximately 0.80. The loading factors for perception range from 0.74 to 0.79, except for two questions: (1) research or publication should be mandatory and (2) research experience should be a criterion for residency training. For the attitude section, the CFA found that MR is exciting and MR is enjoyable, with high impacts of 0.89 and 0.87, respectively, followed by MR being valuable and essential for the medical profession, with loading factors of 0.58 and 0.54, respectively. However, for the questions where MR is complicated and time-consuming, the loading factor was relatively low, under 0.30. Regarding barriers, lack of exposure and opportunities, training and support, mentoring and guidance, and lack of personal knowledge of the research process all had a high loading factor of over 0.70. Lack of statistical support, funding, and lack of rewards or motivations had relatively lower loading factors between 0.60 and 0.69. For motivation, pursuit of further education, pursuit of personal interest, improving their potential in research skills, having mentor guidance/role model and to be a part of solving medical problems in society had high loading factors over 0.70.

Table 3. Confirmatory factor analysis of practice, perception, attitude, barrier and motivation Likert-score and medical research publishing experience

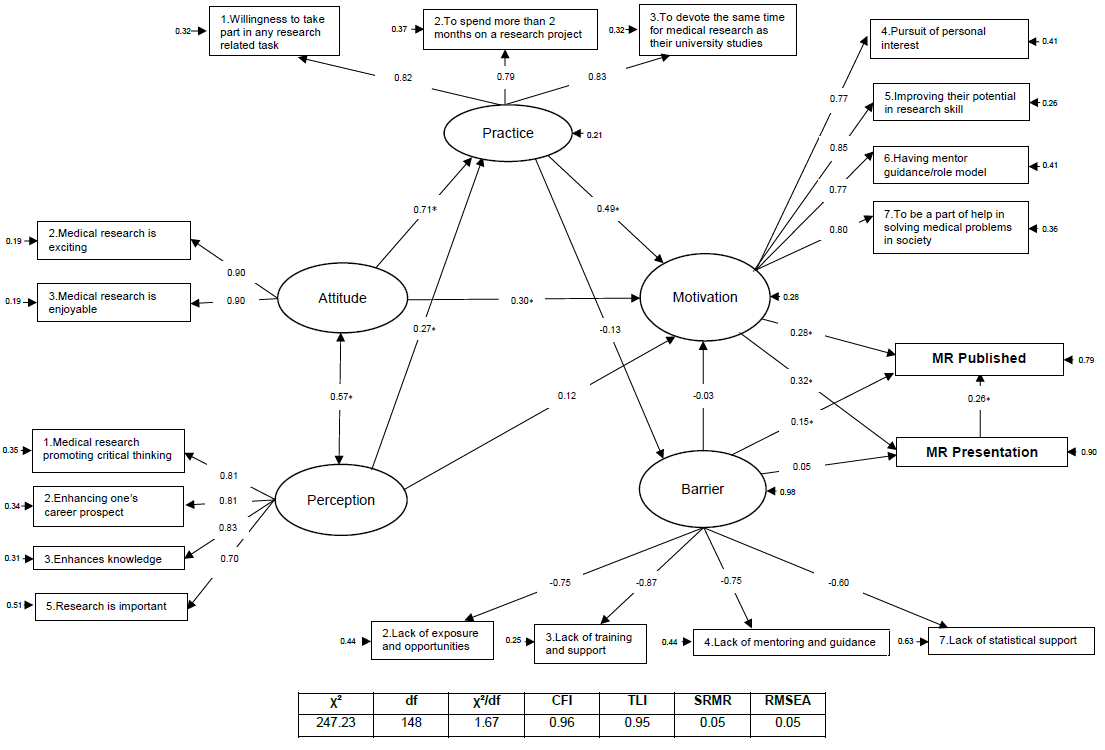

C. SEM of Practices, Perceptions, Attitudes, Barriers and Motivation and MR Publishing

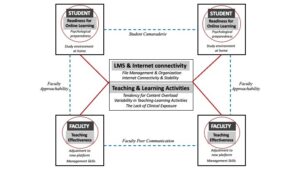

The SEM is developed from five latent variables, leading to the outcome, including medical research presentation and publication (Figure 1). We found that perception has a direct effect on both practices (0.27, p<0.001) and motivation (0.12, p= 0.087). Perceptions and attitudes also correlated (0.57, p<0.001). Practices and attitudes have a direct effect on motivation, 0.49 and 0.30, respectively (p<0.001 for both). The indirect effect of attitudes through practices on motivation was 0.71 * 0.49 = 0.35, all coefficients p<0.001. Practices also exhibited a direct negative effect on barriers (-0.13, p= 0.072). Regarding our primary outcome, both motivation and, surprisingly, barriers also revealed a positive direct effect on MR publishing (0.28, p<0.001 for motivation and 0.15, p= 0.014 for barriers). The MR presentation experience also showed a direct effect on MR publication (0.26, p<0.001). Furthermore, MR presentation also acted as a mediator for motivation, with an indirect effect of 0.08 and a total effect of motivation on MR publication of 0.36. The SEM model provided a good fit for the data (χ²/df= 1.67, CFI= 0.96, TLI= 0.95, RMSEA= 0.05, SRMR= 0.05).

*= P<0.05

Figure 1. SEM of practices, perceptions, attitudes, barriers and motivation and MR publishing

IV. DISCUSSION

We successfully enrolled 139 PCM senior medical students, and 123 interns graduated from PCM. This study is the first to formulate a SEM on the relationship between practices, perceptions, attitudes, motivation and barriers to MR publication and presentation. We found that attitudes, practices and motivation significantly contribute to MR publication and presentation. The roles and experiences that medical students have in medical research during their medical student years are also important to the success of MR publications. However, because our population only includes those who have studied or are studying at PCM, additional external validation may be required.

This study described how baseline characteristics and MR experiences were associated with MR publication. Unsurprisingly, a higher proportion of interns had published MR. GPAX, on the other hand, were not associated with MR publication, which is a common factor in a relative study with positive associations toward perceptions, attitudes and practices (El Achi et al., 2020). A large study in China also reported that research engagement was associated with improving overall learning outcomes (Zhang et al., 2022). This controversy may be explained by two reasons. First, the time required for developing MR and publications is large and might interfere with normal curriculum activity. A study in Colombia noted that their students believed that they could obtain higher GPAs if they were not involved in research (Bonilla-Escobar et al., 2017). The latter is that MR skills and academic skills might not completely overlap. While MR engagement might improve science, scholarship, and professionalism, other domains, such as clinical practice, require more time and effort to learn (Zhang et al., 2022).

MR experiences and roles during MR learning also play an important part in MR publication. Experience in MR presentation was strongly associated with MR publication. This may be partially explained by the student’s readiness before the research presentation; students need to be highly knowledgeable about their own research, and knowledge is a key to success and behavioural change (Bettinghaus, 1986; Pengpid et al., 2016). Furthermore, presentation requires planning, preparation, creating visual aids, and practicing one’s presentation skills. The effort and time spent on this process might be motivation to achieve a higher goal, namely publication. Our study demonstrates that MR presentations, whether nationally, internationally, oral, or poster, are highly associated with MR publication. Thus, MR presentations should be promoted.

Those who had been group leaders had a higher chance of MR publication. During the PCM curriculum, the group leader for MR conduct was never assigned and was elected in each group. Northouse mentioned two forms of leadership: assigned and emergent. Those assigned leadership positions were given the role of group leader. When an individual is perceived as one of the most influential members of a group or organization, that person is exhibiting emergent leadership (Northouse, 2021). Medical leadership development was seen to improve outcomes at the individual, organizational and clinical levels (Lyons et al., 2021). Several leadership training programs in medicine and clinical practices were widely visible. However, to our knowledge, no curriculum focusing on medical research leadership was available.

Perception is described as a method for identifying and interpreting the environment and the meaning of sensual motivations. Cognition may influence perception, which can also occur subconsciously and without cognizance (Saini et al., 2020). Some literature has been carried out showing perceptions, attitudes, and motivation toward research among medical students, in which those with positive perceptions mostly had positive attitudes and motivation (AlGhamdi et al., 2014; El Achi et al., 2020; Osman, 2016). These were similar to our research showing that perception impacts positively on practices and motivation.

In line with the current study, the theory of planned behaviour describes that one’s attitude and how they perceive the behaviour directly affect their intention to perform the behaviour (Bosnjak et al., 2020). The SEM also demonstrated that perception and attitude directly affect the population’s intention to conduct MR (practice). Moreover, a study in Turkey on the predictiveness of attitude and motivation on achievement (vocational English course scores) found a significant positive relationship between attitude and motivation, attitude and achievement, and motivation and achievement (Özer, 2020). Therefore, a positive attitude may positively impact their motivation and their willingness to practice MR. The feeling that MR is exciting and enjoyable had the greatest impact on the attitude domain. Hence, activities that increase the excitement and joy of conducting MR should be encouraged.

The main factors impacting MR publication are motivation, practices, attitudes and perceived barriers. Based on the health-belief model (HBM), providing motivation as needed might help students overcome the triggers of MR barriers so that correct thoughts and perceptions about MR will arise. Thus, techniques derived from motivational interviews might be a useful option for encouraging students toward MR publication (Tober, 2013). One of the most important motivations in our study is having a mentor or role model, and the lack of a mentor constitutes a high-impact barrier. Therefore, mentors should play an important role in guiding their students toward research success. Based on motivational interview techniques, active listening might be the key skill for mentors to better understand their students’ motivations and empower them toward success (Rollnick et al., 2010).

Surprisingly, our study showed that perceived barriers had a positive impact on MR publication. The perception of a barrier greatly influences the likelihood of an individual’s uptake of that behaviour (Becker & Maiman, 1975). Usually, a barrier is a resistance to achieving a goal, which negatively affects achievement. However, the barriers included in our study consisted of a lack of exposure and opportunities, training and support, mentoring and guidance, and statistical support. As a result, those who had not yet published any medical research may not have had the prestige of encountering these barriers, which is why they are perceived as insignificant.

The practice domain included three questions: (1) willingness to participate in any research-related task; (2) willingness to spend more than two months on a research project; and (3) willingness to devote the same amount of time to medical research as they did to their university studies, indicating a willingness to practice medical research. Willingness is the quality or state of being prepared to accomplish something. A study in China about speaking English demonstrated that the willingness to communicate is directly related to motivation and mastery approach (Turner et al., 2021). Furthermore, passion and obsession are what drive an individual to succeed (Dange, 2016).

In view of all the factors presented, mentors have an important role to play in guiding and facilitating the students’ acquisition of adequate experience in medical research during their medical school years. A good extracurricular MR learning environment might be needed to ensure statistical confidence and exposure to conducting research. Actively listening to students and empowering and motivating them to break through barriers may result in successful MR publications. In addition, a different approach to learning MR might be needed to promote attitudes, perceptions and motivations toward MR. According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), when students perceive that the primary purpose of learning is to obtain external rewards, such as exam grades, they may perform less well due to a detrimental effect on their intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999).

SDT revealed that three basic needs must be fulfilled to empower one’s attitude and motivation, including autonomy, competence, and a feeling of belonging (Deci et al., 1999). To promote these basic needs, faculty members could provide extracurricular research time, give choice to research topics and mentors, and hire students to be research assistants, if possible, to promote their autonomy (Rosenkranz et al., 2015). Competence could be enhanced by early research skills introduction and practical training (Rosenkranz et al., 2015). Research mentors may play a crucial role in fostering a sense of belonging toward MR by promoting well-functioning group work through guidance and evaluation (Dorrance et al., 2008). Furthermore, portfolios, logbooks and reflective journals are particularly useful to improve the students’ attitude and motivation (Taylor & Hamdy, 2013). Constant positive feedback from mentors during MR activities is encouraged to improve the learning environment (Peifer et al., 2020). A different approach to learning MR might also benefits the MR learning environment, for example, through game-based learning and other collaborative learning models (Blakely et al., 2009).

The present study encountered several limitations. First, the study included only senior medical students and interns who graduated from PCM, so the model might not be accurately applied to other universities with different curricula and further validation might be needed. Even though most participants who had published a MR were interns (81%), the medical research published was composed while they were medical students. Second, the study was a cross-sectional study, and causal relationships were unavailable. However, according to PCM curricula, for most participants, the MR presentation and their experience with medical research came before the MR publication. Furthermore, personal beliefs change over time, and recall bias might have affected the study results. (Seitz et al., 2017). The beliefs elicited by the questionnaire comprised the participants’ current beliefs, rather than beliefs formed during their participation in medical research publications. As a result, our study investigated only the participants’ current beliefs and their impact on the publication of medical research. A further prospective cohort or qualitative study on whether the students’ current beliefs toward MR are related to successful MR publication is encouraged. Finally, because only participants who volunteered to take part in the study were included, selection bias may also be a significant limitation of this study. Our study had considerable strengths, there had been no reports describing practices, perceptions, attitudes, motivation and barriers toward medical research. However, this is the first study to formulate a SEM model displaying factors related to MR publication.

V. CONCLUSION

Medical research experience and positive practices or willingness, perception, attitude, and motivation in medical research might pave the road to a successful MR publication. Medical research experience and extracurricular activities should be supported by both teachers and faculties through active policies. A different approach to medical research learning might also be needed to promote enjoyment and excitement. Finally, external validation needs to be explored to generalise the model.

Notes on Contributors

SL reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected the data, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. KT, KJ and BS collected the data, developed the methodology framework and developed the manuscript. AK reviewed the literature, designed the study, data analysis and wrote the first draft.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Medical Department Ethics Review Committee for Research in Human Subjects, Institutional Review Board, Royal Thai Army (Approval no. S060q/65_Exp), according to the international guidelines including the Declaration of Helsinki, the Belmont Report, CIOMS Guidelines, and the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). A documentation of informed consent was used, and was granted permission by the Institutional Review Board, RTA Medical Department.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current are available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22128725

Acknowledgement

We thank professors Mathirut Mungthin, Ram Rangsin Panadda Hattachote, Phunlerd Piyaraj and Picha Suwannahitatorn for validating our questionnaire and providing support. This work would not have been possible without the active support of Phramongkutklao College of Medicine and its academic leaders.

Funding

The authors report that there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

References

AlGhamdi, K. M., Moussa, N. A., AlEssa, D. S., AlOthimeen, N., & Al–Saud, A. S. (2014). Perceptions, attitudes and practices toward research among senior medical students. Saudi Pharma- ceutical Journal, 22(2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2013.02.006

Al–Shalawy, F. A.-N., & Haleem, A. (2015). Knowledge, attitudes and perceived barriers towards scientific research among undergraduate health sciences students in the central province of Saudi Arabia. Education in Medicine Journal, 7(1), e16-e21. https://doi.org/10.5959/eimj.v7i1.266

Arif, A., Siddiqui, M. A., Aziz, K., Shahid, G., Shiekh, A., & Fahim, M.F. (2018). Perception towards research among undergraduate physical therapy students. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 7(3), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2018.07.00206

Becker, M. H., & Maiman, L. A. (1975). Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Medical Care, 13(1), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650–197501000–00002

Bettinghaus, E. P. (1986). Health promotion and the knowledge–attitude–behavior continuum. Preventive Medicine, 15(5), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091–7435(86)90025–3

Blakely, G., Skirton, H., Cooper, S., Allum, P., & Nelmes, P. (2009). Educational gaming in the health sciences: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04843.x

Bonilla–Escobar, F. J., Bonilla–Velez, J., Tobón–García, D., & Ángel–Isaza, A. M. (2017). Medical student researchers in Colombia and associated factors with publication: A cross–sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), Article 254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909–017–1087–9

Bosnjak, M., Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107

Carberry, C., McCombe, G., Tobin, H., Stokes, D., Last, J., Bury, G., & Cullen, W. (2021). Curriculum initiatives to enhance research skills acquisition by medical students: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), Article 312. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909–021–02754–0

Dange, J. K. (2016). Perception, passion and obsession: The three elements of theory of success. International Journal of Advanced Education and Research, 1(7), 1–3.

Davila, J. R. (2016). The physician–scientist: Past trends and future directions. Michigan Journal of Medicine, 1(1), 66-73. https://doi.org/10.3998/mjm.13761231.0001.112

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Dorrance, K. A., Denton, G. D., Proemba, J., La Rochelle, J., Nasir, J., Argyros, G., & Durning, S. J. (2008). An internal medicine interest group research program can improve scholarly productivity of medical students and foster mentoring relationships with internists. Teaching and Learning in Medicine,20(2), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330801991857

El Achi, D., Al Hakim, L., Makki, M., Mokaddem, M., Khalil, P. A., Kaafarani, B. R., & Tamim, H. (2020). Perception, attitude, practice and barriers towards medical research among undergraduate students. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), Article 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909–020–02104–6

Funston, G., Piper, R. J., Connell, C., Foden, P., Young, A. M. H., & O’Neill, P. (2016). Medical student perceptions of research and research–orientated careers: An international questionnaire study. Medical Teacher, 38(10), 1041–1048. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1150981

Habineza, H., Nsanzabaganwa, C., Nyirimanzi, N., Umuhoza, C., Cartledge, K., Conard, C., & Cartledge, P. (2019). Perceived attitudes of the importance and barriers to research amongst Rwandan interns and pediatric residents – A cross–sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909–018–1425–6

Ichsan, I., Wahyuniati, N., McKee, R., Lobo, L., Lancaster, K., & Redwood–Campbell, L. (2018). Attitudes, barriers, and enablers towards conducting primary care research in Banda Aceh, Indonesia: A qualitative research study. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 17(1), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12930–018–0045–y

Kamwendo, K. (2002). What do Swedish physiotherapists feel about research? A survey of perceptions, attitudes, intentions and engagement. Physiotherapy Research International, 7(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.238

Laidlaw, A., Aiton, J., Struthers, J., & Guild, S. (2012). Developing research skills in medical students: AMEE Guide No. 69. Medical Teacher, 34(9), 754–771. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.704438

Lev, E. L., Kolassa, J., & Bakken, L. L. (2010). Faculty mentors’ and students’ perceptions of students’ research self-efficacy. Nurse Education Today, 30(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.07.007

Lyons, O., George, R., Galante, J. R., Mafi, A., Fordwoh, T., Frich, J., & Geerts, J. M. (2021). Evidence–based medical leadership development: A systematic review. BMJ Leader, 5(3), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1136/leader–2020–000360

Ma, X., & Xu, J. (2004). Determining the causal ordering between attitude toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics. American Journal of Education, 110(3), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1086/383074

Memarpour, M., Fard, A. P., & Ghasemi, R. (2015). Evaluation of attitude to, knowledge of and barriers toward research among medical science students. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 14(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12930–015–0019–2

Northouse, P. G. (2021). Leadership: Theory and practice (9th ed.). SAGE publications.

Okoduwa, S. I. R., Abe, J. O., Samuel, B. I., Chris, A. O., Oladimeji, R. A., Idowu, O. O., & Okoduwa, U. J. (2018). Attitudes, perceptions, and barriers to research and publishing among research and teaching staff in a Nigerian research institute. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 3, Article 26. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2018.00026

Osman, T. (2016). Medical students’ perceptions towards research at a Sudanese University. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), Article 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909–016–0776–0

Özer, S. (2020). The predictiveness of attitude and motivation on achievement in ESP: The mediating role of anxiety. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 12(2), 25-41.

Pallamparthy, S., & Basavareddy, A. (2019). Knowledge, attitude, practice, and barriers toward research among medical students: A cross–sectional questionnaire–based survey. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 10(2), 73.

Parker, S. M., Vona-Davis, L. C., & Mattes, M. D. (2021). Factors predictive of publication among medical students participating in school-sponsored research programs. Cureus, 13(9), e18176. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18176

Peifer, C., Schönfeld, P., Wolters, G., Aust, F., & Margraf, J. (2020). Well done! Effects of positive feedback on perceived self-efficacy, flow and performance in a mental arithmetic task. Frontiers in Psychology,11, Article 1008. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01008

Pengpid, S., Peltzer, K., Puckpinyo, A., Tiraphat, S., Viripiromgool, S., Apidechkul, T., Sathirapanya, C., Leethongdee, S., Chompikul, J., & Mongkolchati, A. (2016). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices about tuberculosis and choice of communication channels in Thailand. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 10(7), 694-703. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.6963

Puljak, L. (2007). An overlooked source of physician–scientists. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 55(8), 402–405. https://doi.org/10.2310/6650.2007.00029

Rollnick, S., Butler, C. C., Kinnersley, P., Gregory, J., & Mash, B. (2010). Motivational interviewing. BMJ, 340, c1900. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c1900

Rosenkranz, S. K., Wang, S., & Hu, W. (2015). Motivating medical students to do research: A mixed methods study using self-determination theory. BMC Medical Education, 15, Article 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0379-1

Saini, M., Kumar, A., & Kaur, G. (2020). Research perception, motivation and attitude among undergraduate students: A factor analysis approach. Procedia Computer Science, 167, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.210

Schellenberg, B. J. I., Gaudreau, P., & Bailis, D. S. (2022). Lay theories of obsessive passion and performance: It all depends on the bottom line. Personality and Individual Differences, 190, Article 111528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111528

Seitz, R. J., Paloutzian, R. F., & Angel, H.-F. (2017). Processes of believing: Where do they come from? What are they good for? F1000Research, 5, Article 2573. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.9773.2

Simpson, R. D., & Oliver, J. S. (1990). A summary of major influences on attitude toward and achievement in science among adolescent students. Science Education, 74(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730740102

Sobczuk, P., Dziedziak, J., Bierezowicz, N., Kiziak, M., Znajdek, Z., Puchalska, L., Mirowska–Guzel, D., & Cudnoch–Jędrzejewska, A. (2022). Are medical students interested in research? – Students’ attitudes towards research. Annals of Medicine, 54(1), 1538–1547. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2076900

Taylor, D. C. M., & Hamdy, H. (2013). Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Medical Teacher, 35(11), e1561–e1572. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.828153

Tober, G. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 48(3), 376–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt010

Turner, J. E., Li, B., & Wei, M. (2021). Exploring effects of culture on students’ achievement motives and goals, self–efficacy, and willingness for public performances: The case of Chinese students’ speaking English in class. Learning and Individual Differences, 85, Article 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101943

Valladares–Garrido, M. J., Mejia, C. R., Rojas–Alvarado, A. B., Araujo–Chumacero, M. M., Córdova–Agurto, J. S., Fiestas, J., Rojas–Vilar, F. J., & Culquichicón, C. (2022). Factors associated with producing a scientific publication during medical training: Evidence from a cross–sectional study of 40 medical schools in Latin America. F1000Research, 9, Article 1365. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.26596.2

Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(6), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

Zhang, G., Wu, H., Xie, A., & Cheng, H. (2022). The association between medical student research engagement with learning outcomes. Medical Education Online, 27(1), Article 2100039. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2022.2100039

*Anupong Kantiwong

317 Ratchawithi Rd,

Thung Phaya Thai,

Ratchathewi, Bangkok 10400

+66909838338

E-mail: anupongpcm31@gmail.com

Submitted: 2 December 2022

Accepted: 24 July 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 13-22

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/OA3093

Julie Yun Chen1,2, Tai Pong Lam1, Ivan Fan Ngai Hung3, Albert Chi Yan Chan4, Weng-Yee Chin1, Christopher See5 & Joyce Pui Yan Tsang1

1Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 2Bau Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 3Department of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 4Department of Surgery, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 5School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Abstract

Introduction: Medical students have long provided informal, structured academic support for their peers in parallel with the institution’s formal curriculum, demonstrating a high degree of motivation and engagement for peer teaching. This qualitative descriptive study aimed to examine the perspectives of participants in a pilot peer teaching programme on the effectiveness and feasibility of adapting existing student-initiated peer bedside teaching into formal bedside teaching.

Methods: Study participants were senior medical students who were already providing self-initiated peer-led bedside clinical teaching, clinicians who co-taught bedside clinical skills teaching sessions with the peer teachers and junior students allocated to the bedside teaching sessions led by peer teachers. Qualitative data were gathered via evaluation form, peer teacher and clinician interviews, as well as the observational field notes made by the research assistant who attended the teaching sessions as an independent observer. Additionally, a single Likert-scale question on the evaluation form was used to rate teaching effectiveness.

Results: All three peer teachers, three clinicians and 12 students completed the interviews and/or questionnaires. The main themes identified were teaching effectiveness, teaching competency and feasibility. Teaching effectiveness related to the creation of a positive learning environment and a tailored approach. Teaching competency reflected confidence or doubts about peer-teaching, and feasibility subthemes comprised barriers and facilitators.

Conclusion: Students perceived peer teaching effectiveness to be comparable to clinicians’ teaching. Clinical peer teaching in the formal curriculum may be most feasible in a hybrid curriculum that includes both peer teaching and clinician-led teaching with structured training and coordinated timetabling.

Keywords: Peer Teaching, Undergraduate Medical Education, Bedside Teaching, Medical Students

Practice Highlights

- Peer-led teaching environment facilitates questions and answers from learners to strengthen learning.

- Training on specific skills and pre-case preparation can help improve peer teacher effectiveness.

- Clear understanding of the logistics and expectations is necessary to optimise the process.

- Formal peer teacher training may help quality assurance and encourage more participation.

I. INTRODUCTION

In accordance with the longstanding apprenticeship model of medical training, senior doctors and trainees have been responsible for teaching their junior colleagues across the continuum of medical education. Despite this accepted practice, peer teaching has not become widely formalised in undergraduate medical curricula.

Peer teaching has been shown to be beneficial at multiple levels. For students who are being taught by peers, learning is enabled by social and cognitive congruence because of the near-peer demographic which allows for a more comfortable learning environment for free flow of discussion and better understanding of the learner’s challenges including awareness of the primacy for exam success (Benè & Bergus, 2014; Rees et al., 2016). The peer teacher develops and hones teaching skills that will be useful in internship (Haber et al., 2006) and through teaching, develops higher motivation and deeper understanding of concepts and perhaps also improve their own exam performance (Burgess et al., 2014). The institution derives some practical benefit from the supplementary manpower (Tayler et al., 2015) due to the comparable effectiveness of peer teachers in teaching in certain areas such as physical examination and communication skills (Rees et al., 2016) but perhaps most importantly, it benefits from building a collaborative relationship with students in their learning process. Though the benefits of peer teaching have been noted, students remain an untapped resource as training provided for students to serve as teachers is inconsistent (Soriano et al., 2010).

Undergraduate medical curricula aim to provide a foundation for future training and the framework for such curricula are guided by the recognition that medical students must achieve certain outcomes, including being able to teach, to be prepared for future practice. Well-accepted frameworks such as the ‘Outcomes for Graduates’, from the UK General Medical Council (2015) and the ‘CanMEDS Framework’ from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (2015) expect medical graduate to teach others. In Hong Kong, similar guidance is provided in the document ‘Hong Kong Doctors’ published by the Medical Council of Hong Kong, which states that undergraduate medical education must prepare graduates to fulfil the roles of ‘medical practitioner, communicator, educator…’ (Medical Council of Hong Kong, 2017).

It is common in medical schools to have informal peer teaching, where senior students coach junior students on an ad hoc basis or organise revision sessions before exams. Zhang et al. (2011) revealed that a majority of medical students believed that informal learning approaches, including the use of past student notes, and participation in self-organised study groups and peer-led tutorials, helped them pass examinations and be a good doctor. Similarly, in our institution, these kinds of informal peer teaching are popular among students and include sharing sessions on study and exam tips, bedside sessions, and sharing of organised study notes. These activities are not subject to any formal oversight.

With the documented benefits of peer teaching, the availability of enthusiastic senior students who are willing to coach their junior peers, and the demand from junior students to learn from their seniors, there is an opportunity to harness the potential peer teaching that is already taking place. This pilot project is important as it aimed to adapt existing student-initiated peer bedside teaching into the formal bedside teaching curriculum and to examine the perspectives of participants on the effectiveness and feasibility of this initiative. It will be helpful to understand the benefits and drawbacks of formal peer bedside teaching in order to further develop this pedagogical approach in medical education.

II. METHODS

This was a descriptive qualitative study of participants in a pilot peer-teaching initiative for bedside teaching implemented in the first clinical year of study for medical students.

A. Setting

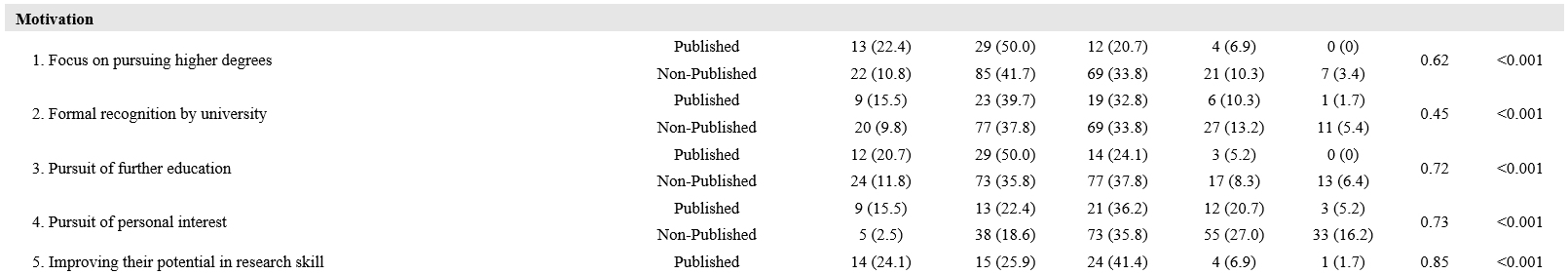

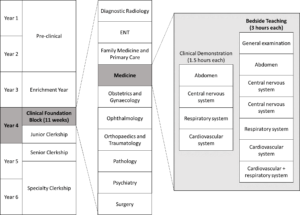

1) Small group bedside teaching for Year 4 medical students in the Clinical Foundation Block: The 11-week Clinical Foundation Block (CFB) of the MBBS Year 4 curriculum at The University of Hong Kong runs from August to October and is the first block of the first clinical year of study. It serves to prepare students for the ward- and clinic-based teaching to follow in the clinical clerkships (Figure 1). Year 4 medical students were selected for the study because it is the first clinical year of study when clinical bedside teaching begins. In addition, as the most junior clinical students, they would benefit most from learning from their senior peers. During the CFB, all Year 4 students learn basic history taking, physical examination and clinical skills as well as common clinical problems of 10 key specialty disciplines. In internal medicine, students attend whole class sessions in which the proper clinical examination of each body system is demonstrated followed by seven small group sessions at the bedside for hands-on practice led by a clinician.

Figure 1. Teaching activities under Medicine within the Clinical Foundation Block in the medical curriculum

Each small group bedside teaching session is comprised of six to eight CFB students who follow the same clinical teacher to examine 3 pre-selected ward patients over a two-hour period. In this pilot study, a peer teacher joined the clinical teacher for the bedside teaching with the first patient case taught by the clinician, the second case taught by the peer teacher under the supervision of the clinician and the final case taught by the peer teacher alone.

2) Peer teaching recruitment and training: Over the years, medical students have been organising bedside peer-teaching on their own and we identified these peer-teaching leaders to help recruit peer teachers for this initiative. Peer teachers recruited in July 2018 and comprised Year 5 students in Senior Clerkship, who were enthusiastic in teaching, and were available to join the training tutorial and take up a subsequent Year 4 CFB bedside teaching session. During the 2.5-hour tutorial, the CFB Coordinator explained the project, and three clinicians then provided a briefing on cardiovascular, neurological, respiratory and abdominal physical examination, common pitfalls, and how to give feedback. There was also time for students to raise questions both on the project and bedside teaching techniques.

B. Participants

The target participants included the three peer teachers who were recruited for this study, together with the three clinician partners and the 24 CFB students in the corresponding three bedside teaching groups. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection.

C. Data Collection

The qualitative data were collected using a dual subjective (peer teachers, clinicians and students) and objective (independent observer) approach was taken to provide a more holistic perspective of the peer teaching experience. A research assistant not involved in the teaching followed one (of the three) peer teachers as the independent observer. All peer teachers and clinicians were interviewed in-person, by phone or by email, using an interview guide (Appendix 1) by the research assistant after the session where field notes were taken and transcribed. CFB students were invited to complete an evaluation form comprised of open-ended questions and a single Likert-scale question (Appendix 2) immediately after the bedside session, to rate effectiveness and to give general feedback about the peer teaching session.

D. Data Analysis

The qualitative data comprising interview field notes, interview transcripts, email transcripts and open-ended questions from the evaluation form collected from CFB students were analysed thematically by the authors JC and JPYT. The Likert-scale question from the evaluation form was analysed using descriptive statistics. All data were anonymised.

III. RESULTS

All three peer teachers and three clinicians who participated in the pilot peer teaching sessions were interviewed. Eighteen out of 24 CFB students consented to participate and 12 completed questionnaires were collected. Three main themes were identified with two corresponding subthemes for each.

A. Teaching Effectiveness

Peer teachers were rated favourably in terms of their teaching effectiveness. From the evaluation form completed by CFB students, the mean peer teaching effectiveness rating was 4.5/5. While a few students felt the teaching effectiveness of clinicians and peer teachers was comparable, many of them felt less intimidated being taught by the peer teachers. Students also appreciated that the peer teachers understood their current level of understanding and therefore were able to make the teaching more effective by tailoring it to their needs. Students found the experience-sharing by the peer teachers an added-value as shown in Table 1 (Item 1-4). All clinicians agreed that the CFB students appeared more relaxed while the peer teachers were teaching, and the peer teachers met their standard of professionalism as shown in Table 1 (Item 3).

|

Subtheme: Learning environment |

|

1. ‘I was more willing to ask questions.’ – CFB Student 8 |

|

2. ‘I felt more comfortable and less intimidate[ed] with the peer teacher.’ – CFB Student 12 |

|

3.‘I think it is pretty well received among the CFB students – they looked like they are more comfortable and less stressed.’ – Clinician B |

|

Subtheme: Tailoring to needs |

|

4.‘We were told her past experience.’ – CFB Student 9 |

|

5.‘More exam advice from peer tutor.’ – CFB student 10 |

Table 1. Exemplar quotes from participants on teaching effectiveness

These comments were congruent with the observations of the independent observer. When the clinician was teaching, students appeared to be cautious when performing physical examination and answering questions from the clinician. On the other hand, when the peer teacher was teaching, students were asking for reassurance while performing physical examination, and appeared less hesitant when attempting to answer the questions. The peer teacher sometimes also asked the students how they would do a certain examination before they actually performed it. He also shared his own bedside experience. After the clinician ended the bedside session and left, the peer teachers stayed behind and answered further questions from the students regarding physical examination skills and examination tips.

B. Teaching Competence

For students, the teaching on physical examination skills by peer teacher appeared to be comparable to that by clinicians, with the perceived benefit of tailored instructions to student’s current level, and additional personal experience sharing as shown in Table 2 (Item 1-2).

After co-teaching with the peer teacher, clinicians had different opinions about the competency of an undergraduate student as a formal peer teacher. Two stated that it was more appropriate for senior students to do sharing instead of teaching, while the other was satisfied with the ability of the peer teachers to teach, and appreciate the opportunity to exchange ideas with peer teachers. One clinician also suggested that peer teachers might need more practice on teaching to build up confidence as shown in Table 2 (Item 3, 6 and 7).

On the other hand, all the peer teachers expressed that they felt stressed being observed by the clinicians. Two of them felt confident to teach, while one was less confident and prefer to co-teach with a clinician as shown in Table 2 (Item 4, 5 and 8).

The peer teachers also questioned their role as a peer teacher in the regular curriculum. They were unsure to teach in place of clinicians in the regular bedside sessions for the CFB students, yet were more comfortable to co-teach with the clinicians, or to teach in unofficial or supplementary peer-led sessions as shown in Table 2 (Item 4, 8 and 9).

|

Subtheme: Confidence in teaching competence |

|

1. ‘Very comprehensive teaching; detailed explanation on how to report findings.’ – CFB Student 1 |

|

2. ‘Senior students know what we need to know and what we don’t know at this stage.’ – CFB Student 5 |

|

3. ‘The peer teacher was sufficiently prepared on content knowledge and teaching skills.’ – Clinician A |

|

4. ‘I am confident with my knowledge and teaching skills. The CFB cases were easy enough for me to handle. I have been teaching student-initiated sessions anyway.’ – Peer Teacher A |

|

5. ‘Are we going to replace the clinicians? The student-initiated sessions worked just fine.’ – Peer Teacher B |

|

Subtheme: Doubts on teaching competence |

|

1. ‘It is too early for the current peer teachers to teach as they lack competency and confidence in teaching.’ – Clinician B |

|

2. ‘Tutors should be at least medical graduates who have shown evidence of proficiency and knowledge in the areas that they teach. Senior students can share their experience of learning, but not to teach.’ – Clinician C |

|

3. ‘The clinicians are definitely better at teaching and has better skills… It would work better if I was to co-teach with a clinician but not to teach solo.’ – Peer Teacher C |

|