Defining undergraduate medical students’ physician identity: Learning from Indonesian experience

Submitted: 16 July 2023

Accepted: 21 December 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 18-27

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/OA3098

Natalia Puspadewi

Medical Education Unit, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction: Developing a professional identity involves understanding what it means to be a professional in a certain sociocultural context. Hence, defining the characteristics and/or attributes of a professional (ideal) physician is an important step in developing educational strategies that support professional identity formation. To date, there are still limited studies that explore undergraduate medical students’ professional identity. This study aimed to define the characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal physician from five first-year and three fourth-year undergraduate medical students.

Methods: Qualitative case studies were conducted with eight undergraduate medical students from a private Catholic medical school in Jakarta, Indonesia. The study findings were generated from participants’ in-depth interviews using in vivo coding and thematic analysis. Findings were triangulated with supporting evidence obtained from classroom observations and faculty interviews.

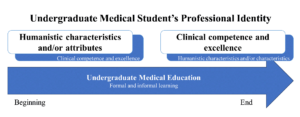

Results: First-year participants modeled their professional identities based on their memorable prior interactions with one or more physicians. They mainly cited humanistic attributes as a part of their professional identity. Fourth-year participants emphasised clinical competence and excellence as a major part of their professional identities, while maintaining humanistic and social responsibilities as supporting attributes. Several characteristics unique to Indonesian’s physician identity were ‘Pengayom’ and ‘Jiwa Sosial’.

Conclusion: Study participants defined their professional identities based on Indonesian societal perceptions of physicians, prior interactions with healthcare, and interactions with medical educators during formal and informal learning activities.

Keywords: Professional Identity Formation, Indonesia Undergraduate Medical Students, Physician Identity

Practice Highlights

- Defining the attributes of ideal physicians is important for developing strategies that support PI.

- Prior interactions with healthcare and formal/informal learning activities influence PI definition.

I. INTRODUCTION

Supporting the (trans)formation of a medical student’s identity, from a layperson to a professional, is an important process in preparing future physicians (Cruess et al., 2014; Goldie, 2012; Wald, 2015). This process includes professional identity formation (PIF) throughout their medical education continuum. Professional identity (PI) refers to how someone represents their profession’s characteristics, values, and attributes through thoughts, actions, and behaviors (Cruess et al., 2014; Gee, 2003; Luehmann, 2011). It is highly related to professionalism, which influences and shapes one’s identity in a professional context (Forouzadeh et al., 2018). The formation of PI involves developing one’s understanding of their professional roles, responsibilities, and expectations that are socio-culturally dependent (Siebert & Siebert, 2007). Therefore, the process of forming one’s PI also involves developing one’s cultural identity (Forouzadeh et al., 2018).

Studies on PI formation in medical education tend to focus on educational strategies that support PI formation during medical training (Adema et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2018; Cruess et al., 2015; Foster & Roberts, 2016). These studies provide insights on how to support PI formation without really addressing what needs to be taught to support medical students’ PI formation. Several theories on identity and PI formation suggest that one’s identity is formed through dialectical conversations that facilitate the acceptance, rejection, or modification of the profession’s characteristics and/or attributes into one’s core identity (Cruess et al., 2015; Gee, 2003; Siebert & Siebert, 2007; Stets & Burke, 2000). These characteristics and/or attributes are usually context-dependent (Cruess et al., 2014). Thus, defining and understanding what it means to be a professional physician in a certain socio-cultural context is as important as finding out how best to facilitate its formation in an educational setting (Wacquant, 2013).

Altruism and humanism are the two most cited values expected from a physician, along with integrity and accountability, honesty, and morality (Cruess et al., 2014; Edgar et al., 2020; Hall, 2021). Additionally, care providers, researchers, and teachers are some professional roles of physicians often mentioned in the literature (Ahmad et al., 2018; Branch & Frankel, 2016; Carlberg-Racich et al., 2018; Hatem & Halpin, 2019). Nevertheless, there might be other roles and characteristics that have yet to be fully elucidated, especially considering that the current literature on PI formation is mainly dominated by the Western representation of the medical profession.

This study aimed to describe the characteristics and/or attributes of ideal (professional) physicians in Indonesia as defined by undergraduate medical students. Undergraduate medical students are unique as they have limited opportunities to interact with real patients in a real workplace. Through this study, we hope to gain new insights from undergraduate medical students on what it means to be a professional physician.

II. METHODS

This was a qualitative phenomenology research using case studies design at a private Catholic medical school in Jakarta, Indonesia. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling method. Transitional phases in one’s life are often associated with identity renegotiation as they are exposed to changes in their roles, responsibilities, and expectations (Kay et al., 2019). Therefore, we sought to explore how Indonesian undergraduate medical students defined their professional identity at the beginning (first-year) and end (fourth-year) of their preclinical years. Ethical clearance was obtained from the school’s Research Ethics Committee prior to the study.

We set a quota of 5 participants for each study year (with a total of 10 study participants) to account for any possible socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religion, and gender variations. We recruited five first-year and five fourth-year preclinical students at the beginning of the study; however, two of the fourth-year participants dropped out during data collection; hence, only eight case studies constructed to depict the characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal Indonesian physician.

Each case study participant was interviewed twice using semi-structured interviews. The first interview was conducted at the beginning of school semester (August 2021) and the follow up interview was conducted one month after. The purpose of the first interview was to determined participants’ current understanding and views of what it meant to be a physician, while the second interview aimed to determine if there were any changes in their understanding or views and what precipitated the changes. Interview questions include: What kind of physician do you aspire to be? Was there one or more specific moment that prompted you to become a physician (if so, please describe it)? What characteristics and/or attributes should an ideal physician possess? Please explain. At the follow-up interviews, participants were asked to re-describe the characteristics and/or attributes of physicians that they aspired to be and what prompted the changes. Furthermore, participants were also asked to describe any specific learning moments that might influence their understanding of what it means to be a professional physician. Because of the COVID-19 physical distancing policy during the data collection phase, all data were obtained virtually or through electronic exchange via secured online platforms. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed in vivo using abductive thematic analysis with Atlas.Ti 8

In addition to from the interviews, we also conducted several classroom observations. We observed the first- and fourth-year’s large classroom lecture, problem-based learning, and skills laboratory session once, focusing on the teacher-student interactions and made note on how, if any, the faculty member facilitated students’ PI formation in the classroom. We also interviewed several faculty members who interacted with the participants in teaching capacity during the data collection phase. Faculty members were asked to describe what kind of physicians they wanted their students to be based on institutional values and their own beliefs about what constitutes an ideal physician. They were also asked to elaborate on their efforts to facilitate those characteristics and/or attributes in the formal and informal curriculum.

Data obtained from classroom observation and faculty interviews were used to triangulate the findings from the participants’ interviews. Permission was obtained from all related parties to record and use the interviews and classroom interactions in the data analysis. Individual case study reports were generated by combining the data obtained from interviews and field notes. These case study reports were then cross-analysed to find commonalities across the case studies to define the characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal physician that the participants aspired to be at their current stage of education.

III. RESULTS

The majority of participants were either Chinese or of Chinese descent. Five participants were Christian Protestants, one was a Buddhist, and two refused to disclose their ethnicity and religion. Note that the names used in these case studies are pseudonyms.

A. Case Study #1: Celine (First-year Student)

Celine, a female of Chinese-Betawi descent from West Java, was raised in a devout Christian-Protestant family. Being a physician was not her childhood aspiration. Initially, she thought physicians tended to be “rude, bossy, had too much pride, unwilling to listen to suggestions” (Celine, Interview 1, Line 42-43), which contradicted her personal values to being humble and helping others as a form of service and manifestation of her faith. Nevertheless, she developed a new appreciation toward physicians when she found out that there were physicians who gave back to the surrounding community by providing free healthcare (see Appendix No. 1).

Humility, and self-reflectiveness—which Celine called “openness to criticism” (Celine, Interview 1, Line 39-44) were the characteristics she deemed important as a physician. She believed that a physician should engage in social actions and put the patient first. Furthermore, a physician should consider the patient’s personal circumstances while providing individualised healthcare based on the patient’s needs. A good physician should also believe that their most important role is to provide credible health information and educate the community to improve their health and well-being. Good communication skills, including active listening, empathy, building trust, and the ability to break bad news, were essential in supporting this role (see Appendix No. 2).

B. Case Study #2: Dimitri (First-year Student)

Dimitri, a Christian-Protestant female of Chinese descent, was quite familiar with medicine and the medical profession as she was surrounded by people who either worked as or studied to become a physician. Additionally, she helped caring for her visually impaired sibling since she was young, which gave her opportunities to interact with various care providers as she accompanied her sibling for treatment. Being a physician naturally became her aspiration since childhood. Dimitri was appointed as a ‘Dokter Kecil’ (or, ‘little doctor’) in elementary school, assigned to provide first aid treatment to fellow students and promote health efforts conducted by the school. Before entering medical school, Dimitri’s grandfather fell critically ill; therefore, she helped her family to care for him in the hospital. There, she met a cardiologist whom she respected. She recalled that she appreciated the way this cardiologist relayed which information could be shared with her grandfather to keep his spirit up and which information should be disclosed to her family to prepare for the worst possible outcome. She mentioned that her grandfather looked “calm and comfortable” in his last days, which helped the family to accept his departure peacefully (Dimitri, Interview 1, Line 77-80).

Dimitri highlighted a physician’s ability to handle the distribution of information as an important part of her ideal physician identity (See Appendix No. 3). She believed that it was acceptable for a physician to keep certain information from the patient if that information could add unnecessary stress or cause them to stop following the treatment (Dimitri, Interview 1, Line 90-98). Regardless, the physician should disclose all information to the patient’s relatives as the patient’s decision-maker. Dimitri aspired to be a caring and compassionate physician with good communication skills who can be held accountable for her actions. Aside from being a care provider, Dimitri believed that a physician should take on a role as ‘Pengayom’ (protector). She believed that patients were in vulnerable positions due to their health issues, and therefore the physician was responsible for protecting them like a parent would when their child was sick. Implied in the Pengayom role was the leader whose responsibility was to make the best decision for the patient’s health and well-being (See Appendix No. 4).

C. Case Study #3: Faustine (First-year Student)

Faustine, a Christian-Protestant female of Chinese descent, was born and raised in a remote area in Riau province, in the southern part of Sumatra Island. Her interest in biology and life sciences prompted her to browse online videos related to healthcare since she was young. She tended to feel sad if the people closest to her were suffering and she could not do anything to help. She made up her mind to study medicine when one of her high school friends was forced to seek treatment abroad because of limited healthcare access in her region. Prior to this, her father was misdiagnosed with a malignant tumor, which caused tremendous distress for her family. These incidents drove her to be a physician who could provide good quality care, especially to those closest to her (See Appendix No. 5).

Faustine aspired to be an empathetic physician, taking patients’ mental or psychological state into consideration when planning for their treatment. She did not want to be a physician who focused on financial gain at the cost of the patient’s wellbeing. Being aware of her limitations in providing care and continuously updating her knowledge and skills were characteristics she hoped to develop once she became a physician (Faustine, Interview 1, Line 103-115). Faustine also mentioned that a physician was responsible for being a reliable source of information and improving community wellbeing through education (See Appendix No. 6).

D. Case Study #4: Jasmine (First-year Student)

Jasmine originated from Rembang, a small regency on the northeast coast of Central Java. Being a physician had always been her childhood aspiration because she loved helping people and interacting with others. Jasmine tended to her grandmother’s health needs during middle school. This event confirmed her passion and desire to serve others. Putting others’ needs above herself was a value instilled by her father since she was young. She wanted to be a physician who focused on social services, and was driven to help others sincerely without expecting anything in return.

As Jasmine mentioned, an ideal physician should be honest, disciplined, possess high ‘Jiwa Sosial’ (an attitude that shows concern to perform actions that are beneficial for humanity and social community), and always put the patient’s needs first (Jasmine, Interview 1, Line 50-53). Jasmine viewed her work as an extension of her faith, and she wanted to reflect Christian values, particularly the value of servitude, in her professional life (See Appendix No. 7-8).

E. Case Study #5: Rose (First-year Student)

Rose, a Christian-Protestant female of Chinese descent, was born and raised in Ambon city, Maluku province, Eastern Indonesia. She was the oldest child in her family. Rose became interested in medicine when her mother was diagnosed with a serious illness and could not receive appropriate treatment. She disclosed that her mother ignored the early signs and symptoms of her illness until her condition became so severe that she could not be treated fully. From this experience, Rose was motivated to become a physician so that she could take better care of her family (See Appendix No. 9).

Growing up, Rose heard several stories in which a patient did not receive appropriate healthcare due to their socioeconomic status. She aspired to be a competent and non-discriminative physician. Putting the patient’s needs first, being responsible, helpful, patient, disciplined, and continuously improving her knowledge and skills were the characteristics that she hoped to develop by the time she became a physician. Aside from being a care provider, Rose believed that a physician was responsible for improving the wellbeing of the community through education (See Appendix No. 10).

F. Case Study #6: *Anton (Fourth-year Student)

*Anton, a Christian-Protestant male of Chinese-descent, had an interest in biology since childhood. He was dissatisfied with Indonesian healthcare services, particularly with the healthcare workers’ communication skills when treating his father. This incident occurred when he was in middle school. *Anton observed a power imbalance between the patients and physicians, where the healthcare providers held more power over their patients. As a patient, he felt disadvantaged because he could not demand a better quality of care nor asked for a lower cost of the care he received (See Appendix No. 11). He described the two roles of physicians: as a healthcare provider and educator. As a healthcare provider, one should be able to help patients understand what is best for them while still respecting their autonomy. As educators, physicians have the responsibility to provide valid evidence-based information for patients.

For *Anton, an ideal physician’s fundamental values and skills included providing good quality care that kept the patients’ best interest, respecting patients’ autonomy, doing no harm, having all necessary medical competencies as listed in the Competence Standards of Indonesian Physician, the drive to learn for a lifetime, patience, humility, competence, and the ability to engage in interprofessional collaboration (See Appendix No. 12).

G. Case Study #7: *R (Fourth-year Student)

*R is a Chinese Buddhist female from Sintang, central Indonesia. *R wanted to pursue medicine because physician was portrayed as a noble profession in Indonesia and as a ‘role model’ in her family. She wanted to serve marginalised areas in East Indonesia after hearing about the poor health situation in those areas from several alumni and fellow students who served there in various capacities. This experience, along with her formal learning experiences, shaped her ideal physician image, which included being detail-oriented, confident, honest, thorough, and caring. She believed that physicians should be able to fulfill the roles and responsibilities of a healthcare provider, which required good proficiency in medical competencies, based on several fundamental values such as honesty, willingness to serve marginalised and under-served communities, and being sensitive to patients’ needs (See Appendix No. 13).

H. Case Study #8: *Anastasia (Fourth-year Student)

*Anastasia, who identified as a female, wanted to be a physician since elementary school. She did not have a specific motivation to enter a medical school when she first started. Nevertheless, there were several past experiences that she claimed to have influenced her image of ideal physicians. She mentioned feeling comfortable being examined by her pediatrician during her childhood. This made her consider the pediatrician as her role model. She also followed several healthcare professionals’ whom she admired on their social media accounts. She claimed that these figures influenced her to be selfless and put the patients’ needs above her own. She acknowledged the importance of entrepreneurial skills in aiding her goal of being selfless yet still able to make a living for herself. Her ideal physician image is someone who has good communication skills, clinical competence, and willingness to learn continuously. She identified healthcare provider as the essential role of a physician, who was responsible for providing physical and mental healthcare, as well as participating in preventive and promotive healthcare. She particularly considered female medical teachers at her school as her role models because she admired the way these figures divide their time and energy to work professionally–both as healthcare practitioners and teachers–and keeping up with their personal and family time. She aspired to be someone who could divide her focus like these figures once she graduated (See Appendix No. 14).

IV. CROSS-CASE ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Cross-case analysis revealed four major attributes of physician identity as defined by the first- and fourth-year participants (indicated by * behind their pseudonyms), including characteristics, values, roles and responsibilities, and skills. First-year participants drew their ideal image of a physician based on their interactions with one or more healthcare provider whom they met in their earlier lives. These interactions left a significant impression that further strengthened their motivation to study medicine and influenced the kind of values or other things that they held important and were willing to stand for as future physicians.

First-year participants mainly mentioned humanistic and altruistic values as the characteristics and/or attributes that define their professional identity. Honesty, humbleness/humility, accountability, patience, jiwa social, prioritising patients’ needs, empathy, care, and compassion are some of the characteristics mentioned by the first-year participants as characteristics of an ideal physician. These characteristics correspond to society’s expectations of professional physicians to put patient’s interest above all else, which is then further translated into medical professionalism and professional responsibilities (Alrumayyan et al., 2017; Elaine Saraiva Feitosa et al., 2019).

Different from their counterparts, fourth-year participants focused on clinical excellence and competence when citing the ideal characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal physician based on the national Competence Standards for Indonesian Physician. This indicates that fourth-year participants were aware of the standards as well as the ethical principles and physician’s code of conduct that were being enforced in Indonesia (See Appendix 15-16).

The way fourth-year participants described their physician identity aligned with the image of a professional physician painted by the school’s teaching faculty. According to interviews with several key faculty members, meeting the minimal standard of competence, being aware of one’s limitations, practicing evidence-based medicine, honesty, and discipline were some of the fundamental physician attributes/values/characteristics that they tried to instill in their students during education. These institutional values were most notably found in the way first-year participants described their physician identity during their second interview (See Appendix No. 17-18).

The attributes of Indonesian physicians mentioned by all case studies participants closely resemble China’s framework of professionalism, where they emphasise altruism, integrity and accountability, excellence, and religion/moral values (Al-Rumayyan et al., 2017). Possessing jiwa sosial (inherent sense of social responsibility, empathy, and engagement) and being a pengayom (mentor/guardian/protector) are two unique attributes that represent the Indonesian ideal physician.

There were minimal overlaps between the first- and fourth-year participants’ ideal physician images. First-year participants placed humanism/altruism and social responsibility as the focal points of their physician identity, whereas fourth-year participants chose clinical excellence and competence to represent their physician identities. Social interactions play a major role in identity formation (Thomas et al., 2016). This may explain the shift in the first- and fourth-year participants’ definition of an ideal physician. First-year participants modeled their ideal physician identity after their memorable interactions with physicians who provided care for them or their family members. Positive past interactions with healthcare providers shaped the characteristics and/or attributes that participants aspired to be, whereas negative past interactions motivated them to develop the opposite of observed characteristics and/or attributes. Fourth-year participants also integrated the characteristics and/or attributes they identified from the formal and informal learning experiences with their evolving understanding of an ideal physician. In these case studies, fourth-year participants cited clinical competencies and excellence, as well as discipline and honesty—which were emphasised by the teachers during their undergraduate medical training—as the major characteristics and/or attributes that defined their physician identity.

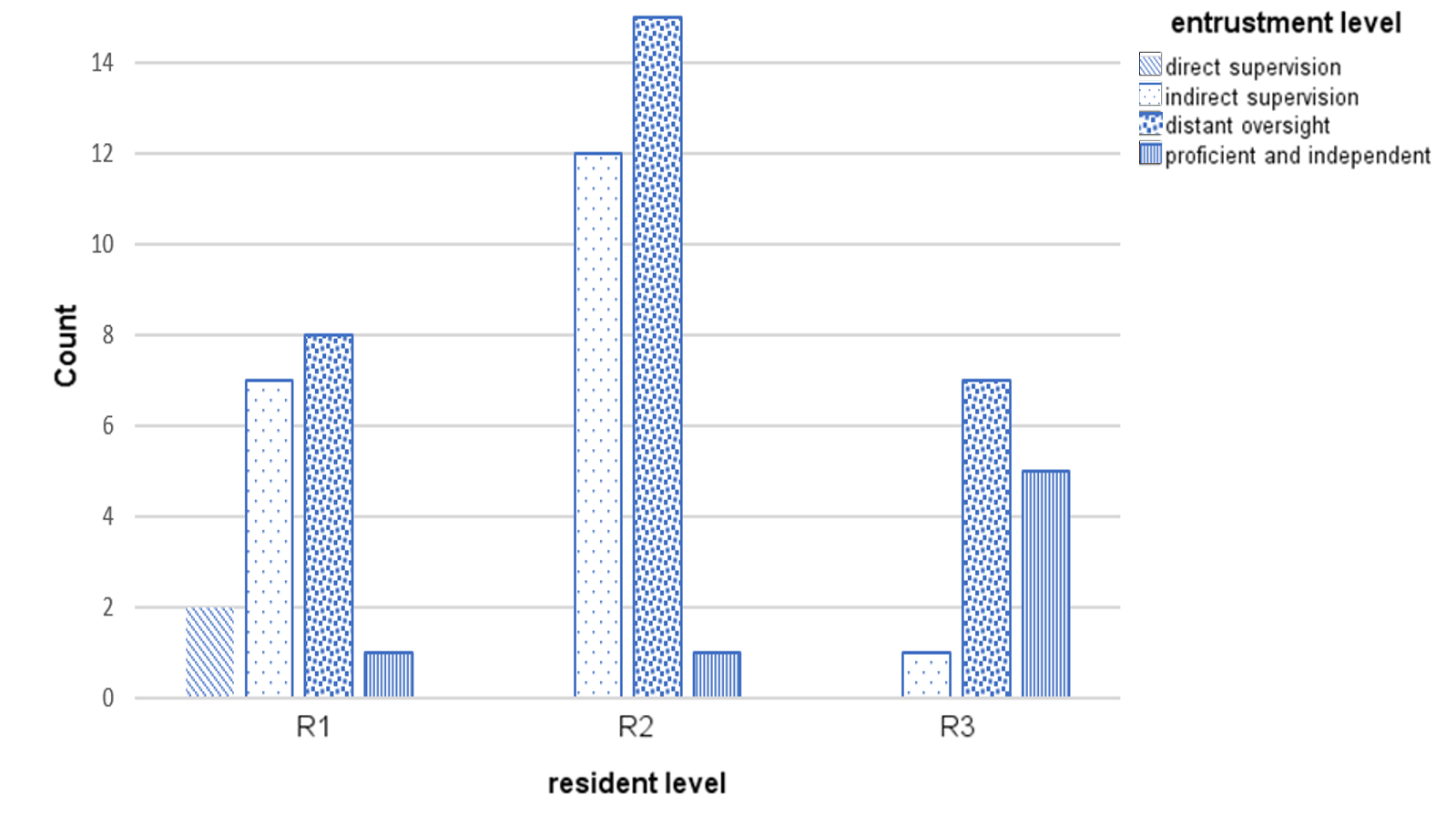

Figure 1. Shift in First-Year and Fourth-Year Participants’ Definition of Physician Identity

The first year of the medical curriculum was indicated to be an important transition point that shaped all participants’ PI. In particular, all participants mentioned the school orientation as one of the learning moments that triggered their identity negotiation. Participants were introduced to the school’s expectations of them as medical students and future physicians. These expectations include the characteristics of self-regulated and life-long learners and those of professional physicians (See Appendix No. 19-20). For example, Jasmine “learned to be disciplined and responsible and she believed that the school orientation “helped shape [her] basic personality as a physician [who needs] to be disciplined and responsible [as well as] trustworthy.” (Jasmine, Interview 1, Line 115-118).

The shifts in participants’ physician identity definition indicated that participants engaged in a dialectical conversation that stimulated them to merge their core or personal identity with the institution’s perception of ideal physicians (“virtual/ideal identity) as interpreted in their curriculum, which was a part of one’s identity negotiation process (Gee, 2003). In the cross-case analysis, we found that participants’ reactions toward the values, characteristics, and attributes instilled by the faculty varied. For example, some participants saw the importance of being on time (‘discipline’) as well as being academically honest by avoiding plagiarism and cheating during exams (‘honesty’), which they accepted as a part of their physician identity. On the other hand, other participants struggled to understand the relevance of being on time and academically honest with their future physician roles or aspirations. This became a major challenge for these participants in incorporating those values into their physician identity. Nevertheless, no participants rejected any characteristics/attributes instilled by the institution even if those characteristics/attributes were distinctly different from their personal beliefs system (See Appendix No. 21-23).

Any new or contradictory characteristics or attributes to one’s core identity pose a professional dilemma that triggers an identity negotiation (Spencer et al., 1997). During this identity negotiation process, the study participants tried to merge their core identity, which was represented by their definition of the ideal physician that they aspired to be, either by accepting, rejecting, or integrating the new characteristics/attributes into their core identity (Cruess et al., 2015).

The acceptance of new characteristics/attributes into one’s physician identity will be easier if it is consistent with one’s core identity; however, it is still possible to instill characteristics/attributes that contradict one’s core identity if they are provided with the long-term benefit of accepting those characteristics/attributes (Guillemot et al., 2022). This underlined the importance of providing students with the relevancy of developing certain characteristics/attributes desired from a professional physician during their educational phase to support their PIF.

V. CONCLUSION

This case study found that first-year participants prioritised humanistic characteristics as the foreground of their professional identity, and medical professionalism as their background. Meanwhile, fourth-year participants developed a projected identity that embodied the general values of the medical profession and those promoted by their institution. The perceived image of ideal physicians as constructed by the Indonesian society’s ideal image of a physician, prior interactions with Indonesian physicians that influenced their decisions to study medicine, and interactions with the medical teachers during formal and informal learning activities influenced the way participants defined their professional identity.

Notes on Contributors

Natalia Puspadewi contributed to the work’s conception and design by developing the study proposal, protocols and instruments, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Further, Natalia also drafted and revised the manuscript and ensured that all aspects of the work were accountable, and followed all procedures to ensure data security and anonymity.

Ethical Approval

This study was a part of a doctoral dissertation. The University of Rochester acted as the author’s host institution, and Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, was the research site. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Rochester RSRB (a letter of exempt determination was obtained on July 8th, 2021 for Study ID 00006273) and the Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, School of Medicine and Health Sciences Ethics Committee (ethical clearance certificate No. 08/07/KEP-FKUAJ/2021).

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the Figshare repository

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23684235. The data were not translated into English to preserve the Indonesian sociocultural nuances captured in the interviews. All data were coded and analysed in vivo in Bahasa Indonesia before being translated into English for presentation in this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to those who have contributed to this study and article development: Dr. Rafaella Borasi as the head of the dissertation committee and advisor, Dr. Sarah Peyre as dissertation committee member, and Gracia Amanta, MD and Cristopher David, MD who helped with manuscript organisation and layouts.

Funding

This study was funded by the Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia and American Indonesian Cultural and Education Foundation.

Declaration of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Adema, M., Dolmans, D., Raat, J. a. N., Scheele, F., Jaarsma, D., & Helmich, E. (2019). Social interactions of clerks: The role of engagement, imagination, and alignment as sources for professional identity formation. Academic Medicine, 94(10), 1567. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002781

Ahmad, A., Yusoff, M. S. B., Mohammad, W. M. Z. W., & Nor, M. Z. M. (2018). Nurturing professional identity through a community based education program: Medical students experience. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 13(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.12.001

Alrumayyan, A., Van Mook, W. N. K. A., Magzoub, M., Al-Eraky, M. M., Ferwana, M., Khan, M. A., & Dolmans, D. (2017). Medical professionalism frameworks across non-Western cultures: A narrative overview. Medical Teacher, 39(sup1), S8–S14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1254740

Branch, W. T., & Frankel, R. M. (2016). Not all stories of professional identity formation are equal: An analysis of formation narratives of highly humanistic physicians. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(8), 1394–1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016 .03.018

Carlberg-Racich, S., Wagner, C. M. J., Alabduljabbar, S. A., Rivero, R., Hasnain, M., Sherer, R., & Linsk, N. L. (2018). Professional identity formation in HIV care: Development of clinician scholars in a longitudinal, mentored training program. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 38(3), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000214

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2014). Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Academic Medicine, 89(11), 1446-1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2015). A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialisation of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 718-725. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

Edgar, L., McLean, S., Hogan, S. O., Hamstra, S., & Holmboe, E. S. (2020). The milestones guidebook. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

Feitosa, E. S., Brilhante, A. V. M., De Melo Cunha, S., Sá, R. B., Nunes, R. R., Carneiro, M. A., De Sousa Araújo Santos, Z. M., & Catrib, A. M. F. (2019). Professionalism in the training of medical specialists: An integrative literature review. Revista Brasileira De Educação Médica, 43(1), 692–699. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v43suplemento1-20190143.ING

Forouzadeh, M., Kiani, M., & Bazmi, S. (2018). Professionalism and its role in the formation of medical professional identity. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 32(1), 765–768. https://doi.org/10.14196/mjiri.32.130

Foster, K., & Roberts, C. (2016). The heroic and the villainous: A qualitative study characterising the role models that shaped senior doctors’ professional identity. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0731-0

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment, 1(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1145/950566.950595

Goldie, J. (2012). The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Medical Teacher, 34(9), e641–e648. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476

Guillemot, S., Dyen, M., & Tamaro, A. (2022). Vital service captivity: Coping strategies and identity negotiation. Journal of Service Research, 25(1), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/10946705 211044838

Hall, C. (2021). Professional identity in nursing. In R. Ellis & E. Hogard (Eds.), Professional identity in the caring professions: Meaning, measurement and mastery. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781003025610

Hatem, D. S., & Halpin, T. (2019). Becoming doctors: Examining student narratives to understand the process of professional identity formation within a learning community. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519834546

Kay, D., Berry, A., & Coles, N. A. (2019). What experiences in medical school trigger professional identity development? Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 31(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1444487

Luehmann, A. (2011). The lens through which we looked. In A. Luehmann & R. Borasi (Eds.), Blogging as change: Transforming science & math education through new media literacies. Peter Lang Inc.

Siebert, D. C., & Siebert, C. F. (2007). Help seeking among helping professionals: A role identity perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432 .77.1.49

Spencer, M. B., Dupree, D., & Hartmann, T. (1997). A Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST): A self-organisation perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579497001454

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., & Mavor, K. (2016). Group interaction as the crucible of social identity formation: A glimpse at the foundations of social identities for collective action. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215612217

Wacquant, L. (2013). Homines in extremis: What fighting scholars teach us about habitus. Body & Society, 20(2), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X13501348

Wald, H. S. (2015). Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: Reflection, relationship, resilience. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 701. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.00000000000 00731

*Natalia Puspadewi

School of Medicine and Health Sciences,

Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia,

Jl. Pluit Selatan Raya No. 19, Penjaringan,

Jakarta Utara, 14440

Email: natalia.puspadewi@atmajaya.ac.id

Submitted: 1 May 2023

Accepted: 21 December 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 5-17

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/OA3053

WCD Karunaratne1, Madawa Chandratilake2, Kosala Marambe3

1Centre for Medical Education, School of Medicine, University of Dundee, United Kingdom; 2Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka; 3Department of Medical Education, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Introduction: The literature confirms the challenges of learning clinical reasoning experienced by junior doctors during their transition into the workplace. This study was conducted to explore junior doctors’ experiences of clinical reasoning development and recognise the necessary adjustments required to improve the development of clinical reasoning skills.

Methods: A hermeneutic phenomenological study was conducted using multiple methods of data collection, including semi-structured and narrative interviews (n=18) and post-consultation discussions (n=48). All interviews and post-consultation discussions were analysed to generate themes and identify patterns and associations to explain the dataset.

Results: During the transition, junior doctors’ approach to clinical reasoning changed from a ‘disease-oriented’ to a ‘practice-oriented’ approach, giving rise to the ‘Practice-oriented clinical skills development framework’ helpful in developing clinical reasoning skills. The freedom to reason within a supportive work environment, the trainees’ emotional commitment to patient care, and their early integration into the healthcare team were identified as particularly supportive. The service-oriented nature of the internship, the interrupted supervisory relationships, and early exposure to acute care settings posed challenges for learning clinical reasoning. These findings highlighted the clinical teachers’ role, possible teaching strategies, and the specific changes required at the system level to develop clinical reasoning skills among junior doctors.

Conclusion: The ‘Practice-oriented clinical skills development framework’ is a valuable reference point for clinical teachers to facilitate the development of clinical reasoning skills among junior doctors. In addition, this research has provided insights into the responsibilities of clinical teachers, teaching strategies, and the system-related changes that may be necessary to facilitate this process.

Keywords: Clinical Reasoning, Medical Decision Making, Medical Graduates, Junior Doctor Transition, Hermeneutic Phenomenology, Qualitative Research

Practice Highlights

- A safe environment and early healthcare team integration facilitate learning clinical reasoning.

- Adopting a comprehensive approach to reasoning can overcome specialty-specific reasoning challenges.

- Trainees’ emotional commitment toward patients could help them learn clinical reasoning skills.

- Interrupted supervisory relationships and early acute care exposure can hamper learning reasoning.

- Ensuring junior doctor training is both service and learning oriented is of paramount importance.

I. INTRODUCTION

Clinical reasoning is composed of cognitive processes, metacognitive processors, and behaviour during the application of critical thinking to a clinical situation and is heavily influenced by numerous contextual factors related to the doctor, patient, and the clinical environment (Durning et al., 2011; Durning et al., 2013; Norman, 2005).

The clinical reasoning of learners evolves along the continuum of medical education with unique challenges associated with major transition phases, the progression from non-clinical to clinical stage, medical graduate to junior doctor, and specialist trainee to medical specialist (Teunissen & Westerman, 2011). Notably, the medical graduate to junior doctor transition presents more pronounced difficulties (Brennan et al., 2010), primarily due to changing roles and responsibilities towards patient care, limited experience in navigating clinical uncertainties, and the need to work within multi-professional teams with limited support. Consequently, these factors have contributed to a steep learning curve for developing clinical reasoning skills (Brennan et al., 2010; Lempp et al., 2005; Prince et al., 2004; Tallentire et al., 2017). The challenges in developing reasoning skills are associated with the reduced applicability of undergraduate training in clinical practice (Cave et al., 2009; Monrouxe et al., 2017), coordinating and organising clinical and administrative responsibilities (Cameron et al., 2014; Teunissen & Westerman, 2011), and dealing with diverse contextual factors in practice. These factors encompass navigating hierarchical relationships and meeting the expectations of seniors, difficulties in recognising disease severity, uncertainty regarding their role, and tension in interpersonal relationships with team members (Cameron et al., 2014; Tallentire et al., 2011, 2017). When these challenges are not resolved, they could boil down to deficits in clinical reasoning and diagnostic error leading to adverse patient outcomes (Graber et al., 2005; Huckman & Barro, 2005; Jen et al., 2009).

The challenging nature of the junior doctor transition is shared across many similar contexts globally (Prince et al., 2000; Teunissen & Westerman, 2011) calling for a coherent approach to facilitate learning clinical reasoning. Concerns around clinical reasoning deficits of doctors continue to soar even today in resourceful developed countries (Health Services Safety Investigation Body, 2022; Huckman & Barro, 2005; Jen et al., 2009), emphasising the need for faculty to take decisive actions to resolve it! Unless for the limited research on clinical reasoning outside the western region (Lee et al., 2021), the situation could have been the same elsewhere.

There is ample evidence of numerous factors that may improve the development of clinical reasoning skills. Accordingly, work experience (Ericsson, 2004; Norman, 2005; Norman et al., 2007), a strong foundation on basic biomedical concepts (Woods, 2007), reflective practice (Mamede et al., 2008, 2012), feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007), learning from others during practice, and conducive organisational context for learning (Goldacre et al., 2003; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lempp et al., 2005) are found to be central in learning clinical reasoning. This evidence, however, is not specific to junior doctors. The learning needs of junior doctors in transition may vary from other trainee doctors and other health professions staff. Therefore, it has become critical that the clinical reasoning experiences, challenges, and practices of junior doctors as a vulnerable group of trainees are understood well to be able to better support their development of clinical reasoning.

When exploring this period of transition, the five-stage model of adult skill acquisition from novice to expert (Dreyfus, 2004), can help understand how junior doctors progress in relation to these stages. The situated learning theory (S. J. Durning & Artino, 2011; Lave, 1991) can provide the basis for understanding the social nature of learning clinical reasoning. The influence of contextual factors on mediating internal motivation for learning clinical reasoning can be understood through the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Taylor & Hamdy, 2013). Therefore, to gain a better understanding of the transition experiences from medical graduates to junior doctors, a longitudinal study was designed using the above theoretical models as the conceptual framework to explore the following research questions:

(1) How do junior doctors evaluate their learning experiences of clinical reasoning development?

(2) What adjustments in the application of different educational means into the learning environment are necessary to improve the development of clinical reasoning skills?

II. METHODS

A. Methodology

The methodological approach of hermeneutic phenomenology (Crotty, 1998; Laverty, 2003) was employed in this study (Kafle, 2011; Laverty, 2003). Such an approach to clinical reasoning was adopted by other researchers exploring clinical reasoning (Ajjawi & Higgs, 2007; Langridge et al., 2015; Robertson, 2012).

B. Study Setting

The study was conducted at the North Colombo Teaching Hospital, Ragama, Sri Lanka with ethical clearance (P/11/01/16) from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya.

In Sri Lanka, medical undergraduate training is a five-year programme with two pre-clinical and three clinical years. After graduation, medical graduates follow a 12-month internship where they work under a consultant for six months each in any of the two main clinical specialities, namely, Medicine, Surgery, Paediatrics, and Gynaecology & Obstetrics before obtaining full registration as a medical doctor.

C. Study Design and Sampling

The study participants were junior doctors during the 12 months of internship following graduation. Maximum variation sampling (Cohen et al., 2017), which enabled purposefully selecting the widest range of variation on dimensions of interest relevant to learning and practicing clinical reasoning was employed. The concept of ‘information power’ which sought not theoretical saturation but sufficient information to address the research questions informed the sample size (Malterud et al., 2016; Varpio et al., 2017). Hence, junior doctors working in the four main clinical specialties, in both university clinical wards staffed by university clinical academics and other clinical wards composed of medical consultants under the Ministry of Health and according to gender were enrolled in the study following informed consent.

Accordingly, eighteen junior doctors (n=18, males=8, females=10) from the four main clinical specialities (Medicine-4, Surgery-5, Paediatrics-4, Obstetrics and Gynaecology-5) were enrolled in the first stage of the study. The second stage of the study imposed heavy demands on the study participants because it involved recording multiple doctor-patient encounters and subsequent discussions based on stimulated recall. Therefore, out of the initially recruited participants, only the well-articulated consenting participants (n=8), who could proficiently express their thoughts and reasoning to obtain a good insight into the nature of practicing clinical reasoning were enrolled in this stage.

D. Data Collection

The data collection proceeded in two stages.

During the first stage, a combination of individual semi-structured interviews with narrative interviews were conducted. Semi-structured interviews allowed probing where necessary (Cohen et al., 2017), while the narratives allowed participants to tell their stories of clinical reasoning (Muylaert et al., 2014). Each lasted for 45-50 minutes.

The second stage included audio-recording the patient consultations of the selected participants on predefined dates during the first and second six months of their internship. The consultations were replayed, and post-consultation discussions were conducted soon afterward by employing a stimulated recall method, to account for a total of 48 post-consultation discussions. As clinical reasoning is a concept revealed only in action (Charlin et al., 2000), employing such an approach was considered essential during this study.

E. Data Analysis

All interviews and discussions were transcribed verbatim. The data analysis followed phenomenological and hermeneutic strategies, which required a thorough description of lived experiences (Ajjawi & Higgs, 2007) and employing a hermeneutic circle for data interpretation by moving back and forth between the parts and the whole of the experience to reach a deeper understanding of the experience (Laverty, 2003).

Thematic data analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012) was conducted to generate themes explaining the data set as a whole.

The principal researcher developed two thematic frameworks for the two stages of the study. The two supervisors of the project re-coded selected transcripts from each stage. These independently derived frameworks were discussed, themes refined, and new themes identified until an agreement was reached. The finalised thematic framework was employed to code all the transcripts using the Atlas.ti qualitative data analysis tool.

III. RESULTS

A total of 18 individual interviews and 48 post-consultation discussions were analysed giving rise to seven themes. During analysis, it was noted that the factors that inform the development of clinical reasoning could be condensed together as a model. This is presented later in the text.

Each theme is elaborated below with quotations. When more than one quotation is required to describe a theme, these are presented within a table. Additional supportive quotations are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23536548.v2 (Karunaratne et al., 2023).

A. A Safe and Supportive Working Environment Empowers Junior Doctors to Develop Clinical Reasoning Skills

It was the collective view that a ‘safe’ work environment is characterised by easy access to more experienced doctors, and the presence of a safety net of seniors who review junior doctors’ work and understand their reasoning challenges. It provided junior doctors the opportunity and freedom to practice clinical reasoning independently, learn from errors, and arrive at their own reasoning decisions.

Such a conducive work environment also provided them with opportunities to emulate seniors and receive real-time feedback while actively participating in authentic tasks and applying knowledge and skills acquired during their undergraduate training.

“I’m working in a unit where each admission is clerked by the registrar. So, in that case, we are always in feedback…What I usually do is sometimes I clerk the patients first, and after that, I compare it with the registrar’s clerking. So, in that case, we can easily adapt their clerking.”

(MP3, Medicine, Male, Phase-1)

B. Learning to Reason with Clinical Problems is Situated and Facilitated by Work Experience

Work experience provided the opportunity to learn from repeated exposure to clinical presentations and their variations, learn from seniors, and lapses of reasoning. However, work experience alone is not solely sufficient, and it is the collective influence of many other factors that help learn clinical reasoning. These factors are captured by the model developed from this study.

With work experience, junior doctors’ approach to reasoning changed from a ‘disease-oriented approach’ developed through undergraduate education to a ‘practice-oriented approach’. In the practice-oriented approach, junior doctors actively analyse clinical problems instead of matching them with memorised configurations of disease presentations.

They also developed ‘instincts’ for swift decision-making, sharpened through experience in recognising contextual factors in patient presentations. This was especially valuable for identifying acute cases requiring urgent care. In addition, they recognised the impact of the previous disease burden in formulating differential diagnoses, leading to a broader approach in their clinical reasoning.

Table 1 illustrates participant quotations that shed light on the role of work experience in learning clinical reasoning skills.

|

“…This approach in the ward is always problem-based. We’re dealing with problems. We try to solve the problems. That approach as a student was trying to fit the history into one of the long cases we have studied…Now we are not worried about that broad category. We will instead deal with the different problems that they have.” (MP2, Medicine, Male, Phase-1) |

|

“I think it’s just being with the patients. You realise that … it’s not just what’s written in the book…I mean now, if you’re just walking past a patient, you realise that this patient is not well. Whereas initially, you would have to go through the ward round and… go through the records, and then only you’ll see it. I don’t know how you get that but…” (MP2, Medicine, Male, Phase-1) |

|

“…Once a child with hypovolemic shock came to the ward. I was in the ward alone. I was very afraid at that time as I was in my first week of internship. So, nothing was on my mind, and I called my senior and he asked me to give (fluid) boluses until he came…. (There was another emergency at the same time). An Angioedema child came to the ward. I thought of (laughing)… running away from the ward. Because it was the initial period, it was very difficult, and our clinical knowledge was also poor. But now, we can manage any emergencies until the senior comes.” (PP, Paediatrics, Female, Phase-1) |

|

(When enquired on the reasons for commencing consultations with comorbidities?) “… Even the presenting complaint may be related to past medical conditions as well…and even this patient has diabetes… so, they can present in various ways… As an intern, I developed that. As an undergraduate, we are asking for name, age, where are you from, and then go on to take the history first…” (MP4, Medicine, Female, Phase-2) |

Table 1. Quotes illuminating that learning clinical reasoning is situated and facilitated by work experience

C. Internal Motivation and the Ability to Reflect and Employ Self-directed Learning are Powerful Tools for Developing Clinical Reasoning Skills

Learning clinical reasoning necessitated junior doctors to be internally driven for learning. Such internal motivation made them willing to learn from any source and be self-directed in their own learning. These individuals progressed rapidly in learning to reason with clinical problems compared to others who were not internally motivated.

Maintenance of internal motivation throughout the internship necessitated external encouragement even for the motivated particularly from the senior staff. There was a similar effect when the work environment fostered a culture of learning with the inclusion and recognition of junior doctors as a group of learners.

Table 2 presents participant quotations that highlight the significance of internal motivation in developing clinical reasoning skills.

|

“(reasoning with a complicated presentation) …With this kind of patient, it’ll refresh our memory. Going through how to take the history, how to use the basics, and how you investigate and manage…It is not like people coming with gastritis, or headache. Those are just simple things. (MP3, Medicine, Male, Phase-2) |

|

“I think you don’t need people who are good at what they do, I mean, you need people who are competent, but er…, you need a pleasant environment. Even if, there are, like 50 patients, if the people you work with are good, you can go through it. But then, if someone is really unpleasant, then that day is ruined.” (MP1, Medicine, Female, Phase-1) |

Table 2. Quotes illuminating internal motivation, reflective practice, and being self-directed as central to learning clinical reasoning skills

D. Caring and Compassionate Attitudes towards Patients Facilitate Developing Clinical Reasoning Skills

The individual caring and compassionate attitudes towards patients and the positive role modeling of senior doctors motivated junior doctors to learn clinical reasoning. Work experience nurtured these attitudes irrespective of gender, reflecting the potential to learn them during practice. However, a heavy workload and orientation towards efficiency in practice hindered the development of such attitudes among junior doctors.

“We’ve realised that although we’re members of a team, even individually, we can always do something for the patients. So, we always try to do something at our level. But we’re always willing to take the feeling from everyone above us to help.”

(MP1, Medicine, Female, Phase-1)

E. Collaborating within a Healthcare Team and Engaging in Ward Activities and Procedures Help Expedite the Development of Clinical Reasoning Skills

Junior doctors learn mostly from registrars, who are the immediate seniors and near-peers. In addition, peers and other healthcare staff contribute to their learning by timely sharing of information and working as a team. Patients’ unique characteristics which demand variation in reasoning also provide learning opportunities.

“I think the main influence is probably the registrars. Because we’re mostly in contact with them…So, in a way through working with them, I think I have learned quite a lot. Different ones will teach you different skills. Some are good at acute medicine and how to do that, and some are very willing to teach us how to do a pleural tap… So, from different people, we have learned different things.”

(MP2, Medicine, Male, Phase-1)

F. The Increasing Recognition of Professional Responsibility and Accountability towards Patient Care Drives Learning Clinical Reasoning

This was a strong theme commonly experienced by all junior doctors. During this transition, junior doctors recognised the patient care responsibilities vested in them and experienced a change of role from an undergraduate to a medical doctor. This led them to internalise their role and work towards meeting these expectations, whilst learning from all opportunities.

“We realise that somehow, we’ve got to do something. It wasn’t like that as students. (Now, as doctors) If we can’t take an ABG (Arterial Blood Gas) once, we will try ten times and somehow take the ABG. We realise- we have that ownership, “This is my patient. I will do something for her.” So, I think that’s a good thing. We didn’t have that as students.”

(MP1, Medicine, Female, Phase-1)

Parallel to the change of role, they were accepted as members of a community of doctors actively involved in providing patient care, which gave them a sense of inclusion and prestige and they worked hard towards meeting the expectations, which in turn helped them learn clinical reasoning.

G. Diversity of Personal, Interpersonal, and Contextual Factors Impede the Development of Clinical Reasoning Skills

Several negative influences on learning clinical reasoning exist.

The personal factors that can diminish learning clinical reasoning are related to a lack of internal motivation to learn and limited use of reflective practice.

In addition, external factors such as lack of encouragement and limited recognition of their contribution as doctors further demotivate junior doctors. Settings supervised by several senior clinicians provide better learning opportunities, but they also expose them to experience individual variations of reasoning due to staff working patterns and hinder their ability to appreciate the continuity of care.

Moreover, as junior doctors, they handle a heavy workload and work under time constraints, which gives them limited opportunity to reflect and learn from experience. Junior doctors also experience the presence of a power gap between juniors and seniors within the healthcare team and maintenance of this hierarchy is a barrier to learning during practice.

Table 3 presents participant quotes highlighting the diversity of contextual factors that hinder learning clinical reasoning skills.

|

“…usually hiccups occur with failures of… all types of failures… I do not have much knowledge about those things. Actually, I got to know that hiccups occur due to organ failure also, after this patient… (laughs)” (no intentions to learn more expressed) (SP2, Medicine, Male, Phase-2) |

|

“…here I think, in our unit, because the consultant changes daily, I think that is a negative point. The fact that you don’t have that connection with one person, and the fact that there is no continuity in care…” (MP1, Medicine, Female, Phase-1) |

|

“…I mean, there are too many admissions some days and you’re just trying to get through from one patient to the next one. So, you don’t really have that much time to analyse the problem as such. I mean, when the ward is less heavy, I’m trying to figure out what’s wrong but some days it’s a little bit… like going through.” (MP2, Medicine, Male) |

Table 3. Quotes illuminating contextual factors that impede the development of clinical reasoning skills

In addition, the discussions with junior doctors revealed that their main goal during the internship was to arrive at a diagnosis and/or manage patients’ clinical problems. No learning-related goals were readily verbalised.

(When enquired about the goals of reasoning during the internship)

“That…..err…is… coming to a final diagnosis and starting the treatment…Basically, we are supposed to recognise life-threatening conditions and treat them.”

(MP3, Medicine, Male, Phase-2)

Similarly, the informal discussions with senior clinicians revealed their limited expectations of the contribution of the internship towards facilitating the development of clinical reasoning skills among juniors. This could be due to the service orientation of the internship leaving ‘learning to happen’ concurrently without being actively encouraged. This is not conducive to learning clinical reasoning.

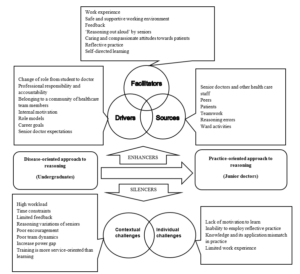

H. The Construction of the ‘practice-oriented clinical reasoning skills development framework’

Embedded within the seven themes were a multitude of factors that could be clearly categorised as ‘Facilitators’, ‘Drivers’, ‘Sources’, and ‘Challenges’ of developing clinical reasoning skills. These factors helped junior doctors to migrate from a disease-oriented to a practice-oriented approach to clinical reasoning (Figure 1).

The categorisation was informed by how these factors influenced the development of clinical reasoning skills. ‘Facilitators’ actively support learning, while ‘drivers’ exert strong internal pressure to motivate learning clinical reasoning. A ‘source’ is an individual or an activity, that helps learn clinical reasoning through interacting with them. ‘Challenges’ are either internal or external to an individual and negatively influence the development of clinical reasoning skills.

Figure 1. ‘Practice-oriented clinical reasoning skills development framework’ highlighting the factors that influence the development of clinical reasoning skills during the transition from medical graduates to junior doctors

IV. DISCUSSION

Aligned with existing literature (Brennan et al., 2010; Lempp et al., 2005; Prince et al., 2000; Teunissen & Westerman, 2011), this study identified a steep learning curve for junior doctors in developing clinical reasoning skills upon commencing the internship. A ‘disjunction’ (Koufidis et al., 2020) was evident between knowledge acquired during medical undergraduate education and the demands of effective reasoning in clinical practice (Cave et al., 2009; Monrouxe et al., 2017). The ‘practice-oriented clinical reasoning skills development framework’ derived from this study shed light on the factors serving as ‘enhancers’ and ‘silencers’ of learning clinical reasoning skills during this critical period. This classification helps consolidate existing knowledge specific to this period and offers insights for addressing disconnections and facilitating the development of clinical reasoning skills.

In this study, novice doctors initially faced clinical reasoning challenges due to limited contextual understanding and reliance on rule-based reasoning comparable to the Dreyfus model of adult skill acquisition (2004). With increased work experience, they were able to promptly recognise contextual features distinguishing acute from non-acute presentations requiring urgent care. Additionally, they acknowledged the significance of the patient’s past medical history in forming a broader approach to reasoning. Some even acquired instincts for prompt clinical decision-making, a form of non-analytic reasoning identified by clinical experts (Norman et al., 2007) and blending non-analytic reasoning with occasional rule-based confirmation (analytic reasoning). This dual-process approach (Croskerry, 2009; Eva, 2004; Pelaccia et al., 2011), incorporating both analytic and non-analytic reasoning is recognised to overcome challenges associated with each approach. Such development of clinical reasoning skills with work experience is reflective of the advancement of reasoning skills along the first four stages of the Dreyfus model, from novice to proficiency stages. This contrasts with the limited value placed on the internship for developing clinical reasoning skills among some clinical supervisors and needs addressing during staff development initiatives.

It was also noted that junior doctors revert to the novice stage using more analytical rule-based reasoning with uncommon presentations or at the start of a new rotation in another specialty (Groves, 2012). This highlights the complexity of developing clinical reasoning skills, varying with the nature of the presentation and the clinical specialty, requiring more support for its development. This aligns with the ‘context-specific nature’ of clinical reasoning (Eva et al., 1998), the variation of reasoning outcomes of an individual due to contextual factors unique to clinical situations. The study revealed a clear influence of clinical specialty on reasoning, confining the development of clinical reasoning to a few focused clinical problems common to a particular specialty. This limits the overall development of clinical reasoning and hinders the momentum of clinical reasoning development entering a new clinical specialty. Therefore, clinical teachers should promote a comprehensive approach, considering differential diagnoses beyond a single specialty. Given the need for promptly recognising contextual features of disease severity in acute care settings coupled with early internship challenges, delaying trainees’ placement in acute care settings until later in a clinical rotation is a reasonable approach, contrary to current clinical practice.

Work experience was central to developing clinical reasoning skills (Charlin et al., 2007; Schmidt & Rikers, 2007; Schmidt & Boshuizen, 1993), but benefiting from experience required junior doctors to be internally motivated. According to the self-determination theory, when an individual experiences a feeling of being able to do something successfully (competence), when their actions are controlled internally or self-determined (autonomy), and when there is a sense of safety, belonging, and supportive relationships (relatedness), it enhances the intrinsic motivation of an individual (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and this was clearly noted during this study. The ‘drivers’, ‘facilitators’, and ‘sources’ of learning clinical reasoning identified during this study enabled fulfilling these three basic psychological needs required to be motivated to learn clinical reasoning. Hence, the ‘practice-oriented clinical skills development framework’ could serve as a valuable reference for clinical teachers supporting junior doctors in developing clinical reasoning skills during their transition to the workplace.

Echoing the evidence in the field (Ajjawi & Higgs, 2008; Gruppetta & Mallia, 2020), junior doctors recognised the change in their role from student to medical doctor and subsequent absorption into the healthcare team which made them internalise their responsibility and accountability towards patient care. Their engagement in patient care gradually increased to finally becoming valued members of this community, collaborating with other like-minded colleagues to develop a more deliberate understanding of reasoning and methods of using it. This aligns with the principles of legitimate peripheral participation and community of practice of the Situated Learning Theory (O’Brien & Battista, 2020). The community of practice created a safe learning environment, motivating junior doctors to learn clinical reasoning actively. This emphasises the significance of early integration of junior doctors as valued members of the healthcare team. A team-oriented approach to patient care, acknowledging every team member’s contribution, proves more beneficial here than an individual-focused hierarchical approach.

The junior doctors of this study learned through their interactions with senior doctors, peers, and other healthcare staff, as well as by actively participating in ward activities, revealing learning as a dynamic social act. The opportunity to observe, listen to, and emulate senior colleagues as they engaged in clinical reasoning with authentic patient presentations, followed by the application of the newly acquired skills, significantly influenced the development of their clinical reasoning skills. This highlights the continued relevance of apprenticeship as a pedagogical tool today (Dornan, 2005), facilitating the ongoing development of clinical reasoning skills among junior doctors. It also provides a unique opportunity to witness firsthand the decision-making processes of junior doctors operating independently in clinical practice, aligning with the highest level of clinical skills assessment in Miller’s pyramid (Miller, 1990). This presents a potential opening for formative assessment of clinical reasoning, whether conducted formally or informally, as part of junior doctor training.

Junior doctors also constructed knowledge through interpersonal interactions in the workplace by engaging in an iterative process of learning, application, and consolidation of knowledge with each experience contributing to the refinement of their clinical reasoning skills. Learning from these experiences required them to reflect on these experiences and arrive at new understandings by integrating and building on previous knowledge. This is aligned with the principles of experiential learning theory (Morris, 2020; Yardley et al., 2012) and the constructivism learning theory (Olusegun, 2015). This highlights the importance of encouraging reflection by proactively including junior doctors in all pertinent patient-related discussions. Also, the value of implementing a reflective portfolio to acknowledge junior doctors’ learning needs at the outset of the internship, with formative assessments conducted midway and at its conclusion by clinical supervisors. This could also introduce a learning orientation to the already service-focused internship placement.

Junior doctors found collaborative learning, including referrals to other specialties and engaging in those discussions or working in partnerships with peers, beneficial for developing clinical reasoning (Laal & Laal, 2012; Tolsgaard et al., 2016). This highlights the value of involving junior doctors in collaborative work within or across disciplines. Simulation-based training (Khan et al., 2011) offers similar opportunities for collaborative learning within a safe environment, without compromising patient safety. Integrating simulation-based training for junior doctors immediately after graduation or before the internship can equip them with reasoning skills for authentic practice, addressing challenges during their transition to the workplace.

The caring and compassionate attitudes instilled in junior doctors by their seniors and further nurtured through close patient interactions, served as indirect motivators for learning clinical reasoning skills. This is an area not widely discussed in literature. While there is acknowledgment of the potential influence of clinicians’ emotions on clinical reasoning (Kozlowski et al., 2017), the specific impact of emotional closeness in patient care, and whether it aligns with the conventions of a more objective, rule-based healthcare delivery system, remains an area that merits more comprehensive investigation (Dreyfus, 2004). However, the study findings support that the more emotionally closer the junior doctors are to their patients, the more they are invested in learning clinical reasoning to ensure healthier outcomes for their patients. Clinical teachers could nurture such attitudes through role modeling as noted in this study.

The interrupted supervisory relationships due to work rotations of the senior staff challenged learning clinical reasoning. Such system-related factors deprived junior doctors of learning by emulating senior practice. It also hampered their ability to appreciate the continuity of patient care due to individual variations of reasoning among senior staff and prevented developing closer relationships with seniors, which could have been more emotionally satisfying (Ryan & Deci, 2000). This underlines the need to take necessary steps to prevent any adverse effects of staff working patterns on trainee doctors, while simultaneously ensuring extended periods of supervision within a consistent healthcare team.

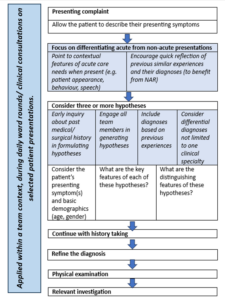

The collective findings of this study not only confirm but also add valuable insights to the clinical reasoning pathway for teaching clinical reasoning skills (Linn et al., 2012). According to this framework, the teaching of clinical reasoning occurs in three stages through three consultations. Stage 1- Demonstration and deconstruction, Stage 2- Comprehension, and Stage 3- Performance. The transition in focus from the teacher’s approach to the student’s performance occurs in the last stage. In junior doctor training, this framework is ideally applied within a team context during daily clinical ward rounds focusing on selected patient presentations as afforded by the time constraints. The three stages of the framework can be combined, and the reasoning discussions can be brief and can take place within the ward round after the selected presentations with increasing junior doctors’ involvement as they gain experience. This could allow junior doctors to learn from verbalised reasoning from the team, reflect and actively contribute to the discussion, and feel valued as team members. They can apply newly acquired reasoning skills in subsequent patient consultations independently, in addition to the opportunity to demonstrate these during the ward rounds. Based on the study findings, additional considerations for analysing patient presentations could be proposed as enhancements to the clinical reasoning pathway (Linn et al., 2012). These aspects are detailed within the overall structure of this framework in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Proposed additions to the deconstructed consultation according to the clinical reasoning pathway (Linn et al., 2012) for teaching clinical reasoning to junior doctors as part of daily clinical ward rounds

Additions are presented in italics and highlighted. (NAR- non-analytic reasoning)

V. CONCLUSION

The ‘practice-oriented clinical skills development framework’ has brought together factors that act as ‘enhancers’ and ‘silencers’ of learning clinical reasoning specific to this period of transition from medical graduates to junior doctors. These findings offer practical insights that can prove invaluable for clinical educators in their teaching practices to facilitate the development of clinical reasoning skills.

This research also offers insights into the responsibilities of clinical teachers in supporting the development of clinical reasoning skills among junior doctors during their internship. It provides suggestions for teaching these skills in practice and highlights potential system-related changes needed to facilitate this process.

A. Limitations of the Study

The reader needs to determine the applicability of the findings to their context to overcome the limitations of qualitative research. To facilitate this process, the methodology and the data analysis are appropriately detailed.

The study focused on immediate medical graduates, and therefore, it did not delve into the clinical reasoning experiences of junior doctors at different levels of seniority and training, although this could have added to our understanding. This lack of comparative analysis is another limitation of this study.

Notes on Contributors

Dr WCD Karunaratne conceptualised the study, prepared the study proposal, conducted all interviews, analysed them and developed the manuscript for this submission.

Professor Madawa Chandratilake was a supervisor of this study and he contributed to the study design, guided initial interviews, and analysed selected transcripts to finalise the final coding framework for the study. He also reviewed and provided feedback on different versions of the manuscript.

Professor Kosala Marambe was also a supervisor of the study. She contributed to the study design and analysis of selected transcripts to finalise the final coding framework for the study and provided feedback on different versions of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance (P/11/01/16) was obtained from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

Data Availability