Scholarship in Health Professions Education-Development from the Past to Future Possibilities

Submitted: 4 November 2023

Accepted: 20 November 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2),98-100

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/PV3165

John Norcini

Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, United States of America

I. INTRODUCTION

Over the past 25 years, the Asia Pacific region has seen striking growth in the scholarship of health professions education, and it is poised to continue its development. A window into the past and a glimpse of the future can be found in the meetings of the Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC), which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary. To frame my personal observations, a word cloud was created using the titles of the plenaries, keynotes, and symposia of the 2003, 2004, and 2006 conferences and another was created using the titles from 2021, 2022, and 2023. When comparing these two clouds (an exercise akin to interpreting inkblots), three themes emerged: interprofessional education and practice (IPEP), the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), and the growing role of technology.

Interprofessional Education and Practice. In the first three conferences, the most common word was ‘medical’ and in the last three it was ‘education’. This parallels developments in the field, which started with a focus entirely on medical education, expanded to all the health professions, and in its most recent iteration, turned to interprofessional education. The reason for this latest development is research showing that interprofessional practice results in better patient outcomes, improved efficiency of care, and increased satisfaction among providers (Reeves et al., 2017).

One of the biggest barriers to IPEP is social closure, defined by Mackert (2012) as the “process of drawing boundaries, constructing identities, and building communities in order to monopolize scarce resources for one’s own group, thereby excluding others from using them.” (Mackert, 2012). Each profession has an educational model that encompasses as much of practice as possible, and they compete over ownership at the boundaries. This limits interprofessional cooperation and the opportunity for joint training.

Social closure has been institutionalised through the regulatory processes (i.e., accreditation and licensure/registration) used in many countries. These fix the boundaries of the professions and the nature of training and practice. Regulation ensures initial competence but makes it challenging to develop shared competencies across the professions. Moreover, there are few regulatory requirements for keeping up with changing practice and even fewer ways to acknowledge the acquisition of additional competencies after formal training.

Digital badges or micro-credentials are one way to approach the issue of social closure. They are circumscribed credentials based on shorter educational experiences followed by assessment. They can be part of existing broad educational and regulatory processes, complement them, or replace them in part. These credentials can be applied across professions and throughout careers.

Micro-credentials can support the development of IPEP by increasing access and shifting the focus from what the professions can do, to what patients and healthcare systems need. The fact that different professions experience the same educational process leads to comparability across providers regardless of discipline, less siloed regulation, and increased interprofessional collaboration. Furthermore, it offers a pathway for practitioners who seek to upgrade their skills or acquire new competencies.

The scholarship of teaching and learning. The second theme that emerged from a comparison of the word clouds was the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL). ‘Curriculum’ and ‘assessment’ were prominent in the first APMEC conferences, but they vanished recently, with ‘learning’, ‘scholarship’, and ‘educator’ being more prominent. In my view, this shift signifies the growing role of SoTL.

The goal of SOTL is to improve student learning by identifying effective teaching practices and disseminating those practices. It is a relatively new field of scholarship that has nine attributes: “committed engagement in action, critique-based, disciplinary, context-oriented, critical enquiry process, continuous deep reflection, dynamic process, shared publicly, and learning focused.” (Mirhosseini et al., 2018).

A recent edition of the Asia Pacific Scholar exemplifies this work (Lee & Norcini, 2023). It included studies that addressed topics such as community based interprofessional education, cultural awareness training in the emergency room, approaches to vaccine hesitancy, innovative oral exams for occupational therapy students, and coaching programs for faculty members.

Technology. The third theme that emerged from the comparison of the word clouds was technology. ‘eLearning’, prevalent in the early days of the conference, has disappeared to be replaced by ‘technology’. In my view, this signifies its growing role in health professions education and assessment. To pursue this further, Bard (Google’s AI chatbot) was asked, “What effect will technology have on education in the health professions?” Below is Bard’s response, edited for British spelling and for length by removing examples.

“Technology is already having a significant impact on education in the health professions, and this trend is only going to accelerate in the coming years. Here are some of the key ways in which technology is transforming health professions education

- Increased use of e-learning and simulation provides students access to high-quality educational resources and experiences, regardless of location or time constraints.

- Technology can be used to create personalised learning experiences for each student.

- Technology can be used to facilitate interprofessional collaboration between students and healthcare professionals from different disciplines.

- Technology can be used to collect and analyse data on student learning and performance.

Overall, technology is making health professions education more accessible, personalised, and effective.

Here are some of the potential benefits of using technology in health professions education:

- Improved access to education: Technology can help to break down barriers to access to education, such as distance, time constraints, and financial resources.

- Increased student engagement: Technology can be used to create more engaging and interactive learning experiences.

- Improved learning outcomes: Technology can be used to personalise learning, provide feedback, and track student progress.

- Better preparation for practice: Technology can be used to simulate real-world clinical scenarios and help students to develop the skills they need to be successful practitioners.

However, there are also some potential challenges associated with the use of technology in health professions education, such as:

- Cost: Technology can be expensive to purchase and maintain

- Digital divide: Not all students have equal access to technology resources

- Technical challenges: Technology can be complex and difficult to use

- Quality control: It is important to ensure that technology-enhanced learning resources are high-quality and effective

Overall, the benefits of using technology in health professions education outweigh the challenges. However, it is important to use technology thoughtfully and strategically to ensure that it is used to enhance learning, not replace it.” (Bard, 10/30/2023)

This is an impressive performance by Bard, and it offers a small preview of what technology may do. The ideas are not novel, but a wide range of thinking was summarised in a systematic fashion within seconds. This is just the beginning for generative artificial intelligence but it is clear that technology will reshape educational practice and scholarship. It also raises important questions about how we interact with it going forward.

II. SUMMARY

APMEC’s history provides a means of describing the dramatic growth in health professions education in the Asia Pacific region. The past 25 years have seen the focus of research expand from its start in medical education through all the health professions to IPEP. To drive this growth, new forms of scholarship have taken root. With its strong emphasis on context, SoTL enhances the relevance of this research to the cultures and practices of the region. Finally, technology, and our relationship with it, will have profound effects going forward. Taken together, these trends lay the groundwork for future work that will serve the needs of the region and have sizeable influences beyond it.

Note on Contributor

John Norcini wrote the paper.

Funding

No funding was involved.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

Lee, S. S., & Norcini, J. (2023). Celebrating excellence in the scholarship of teaching and learning. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 8(2), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/EV8N2

Mackert, J. (2012). Social Closure. Oxford University Press.

Mirhosseini, F., Mehrdad, N., Bigdeli, S., Peyravi, H., Khoddam, H. (2018). Exploring the concept of scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL): Concept analysis. Medical Journal of The Islamic Republic of Iran, 32(1), 553-560. https://doi.org/10.14196/mjiri. 32.96

Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Harrison, R., Goldman, J., & Zwarenstein, M. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD0000 72.pub3

*John Norcini

Upstate University Hospital

750 East Adams Street

Syracuse, NY 13210

Email: John.norcini@gmail.com

Submitted: 30 June 2023

Accepted: 19 October 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 95-97

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/PV3075

Gabriel Tse Feng Chong1,2

1Singapore Armed Forces HQ Medical Corps, Singapore; 2Dental Specialist Accreditation Committee (Dental Public Health), Singapore

There is growing awareness of the need to include humanities in educating dental students at the undergraduate/pre-doctoral level (Marti et al., 2019). However, there appears to be no literature discussing or advocating the inclusion of humanities for the training of dental specialists. Dental Public Health (DPH) is one such dental specialty where its trainees and practitioners would benefit from an inclusion of humanities in its pedagogy.

This author opines that exposure to humanities (which includes, but is not limited to, literature – both fiction and non-fiction, art, history, narrative dentistry/medicine, philosophy, ethics, and medical anthropology) that touch on dental themes can make a DPH trainee/practitioner more rounded; able to empathise better with the individuals that his/her policies and programs would affect; become even more persuasive in health promotion efforts; and more articulate in their advocacy efforts with stakeholders and policy makers.

Unfortunately, the curriculum of most DPH training programs (in English speaking jurisdictions) do not include humanities apart from the inclusion of ethics in North American programs. Perhaps the roots of this problem can be traced back to the dental undergraduate/pre-doctoral level where the typical training is predominately focused on biomedical subjects. The result is “few dental schools have implemented humanities in their dental education” and where humanities are taught, ethics tend to form the bulk (Marti et al., 2019). At the postgraduate specialty-training level, this traditional segregation between what are considered ‘sciences’ on one hand, and ‘humanities’ on the other hand, are already ingrained for most dental specialties. However, the DPH curriculum is different from the sister dental specialties because the trainee is required to understand for instance: sociology, health-related behaviors, the interactions of social, cultural and political variables (including age, gender, socioeconomic status, culture, religion, ethnicity and globalisation) on public health, health inequities, and the provision of health services. In essence, the DPH curriculum aims to re-orientate the trainee from a biomedical model of care to a biopsychosocial model of care. As such, the DPH curriculum is a natural starting point for the inclusion of humanities in the training of dental specialists.

There are some foreseeable barriers to implement humanities in the DPH training curriculum – (i) the possible lack of DPH educators and practitioners who are well-versed or at least comfortable with humanities and this itself may be a barrier to even commencing the addition of humanities into the pedagogy, and (ii) finding the time and space to include humanities into the voluminous curriculum that the DPH trainee is expected to cover in a relatively short amount of time. One suggestion to resolve the former barrier is cross-disciplinary training, where dental and/or public health schools can reach across to educators and researchers in the humanities departments to co-develop the DPH-humanities curriculum and training materials. The latter barrier can perhaps be tackled by infusing readings and discussions on humanities into the DPH curriculum that already require the trainee to adopt a biopsychosocial approach to healthcare and where humanities would be natural additional skillsets for inclusion in the DPH trainees’/practitioners’ toolbox.

Oral health inequities exist in most, if not all, societies. The burden and resultant impact of dental caries is largely borne by those who are disadvantaged and underserved. This is true even of an affluent country in Asia-Pacific like Singapore with a highly educated populace with very good healthcare system, infrastructure, and policies. Singapore enjoys (i) an universal community water fluoridation program covering 100% of Singapore’s population, (ii) public health education to increase awareness and health literacy by actors, such as, the Ministry of Health (MOH) and Health Promotion Board (HPB), (iii) free dental care to school children up to 18 years of age, and (iv) an extensive network of dental clinics in the private and public sector (Chong & Tseng, 2011). Despite all these benefits, the burden of poor oral health is mainly carried by members of lower socioeconomic groups and certain racial groups (Chong & Tseng, 2011).

Humanities can also challenge the lens through which a DPH trainee/practitioner views oral health problems. For instance, even the current epidemiological trends of dental caries was not always the case. For example, if we were to go back in time to about the late 18th century, dental caries in Europe was largely a disease of the affluent. This is even mentioned in a gastronomical literature text ‘The Physiology of Taste’, written by Brillat-Savarin (published in 1825), in which the author describes the poor oral health of his fellow diners. He writes “what then if the mouth is neither fresh nor pretty? And what shall be said of those monstrous chasms which open up to reveal pits that would seem bottomless, if it were not for the sight of shapeless, time-corroded stumps?” (Chong, 2012).

What caused the epidemiological shift such that dental caries was no longer a disease of the affluent but became one of the poor? This is because until about the late 18th century, sugar was not yet widely available to the masses for consumption frequently and/or in large quantities so as to cause widespread decay. For example, in England, the annual consumption of sugar per capita increased from almost zero in the 17th century to 1.8kg in 1704 to 8.2kg in 1800, and finally to 40.8kg by the mid-19th century (Chong, 2012). Several factors have been identified as the causes of increased consumption of sugar during this period: increased disposable income due to the industrial revolution; the availability of processed foods and beverages; and the change in dietary habits to add sugar as a sweetener to tea and coffee (Chong, 2012).

This historical trend is important for the modern DPH trainee/practitioner because it approximates ecological studies and supports our modern understanding that the intake of dietary sugars is the most important risk factor for developing dental caries. This should focus DPH trainees’/practitioners’ efforts to tackle the Social Determinants of Health (including the commercial determinants, such as the health risks posed by the sugar and fast-food industries). Furthermore, the 180-degree shift in the epidemiology of dental caries should serve as a reminder that what is the norm of today can be changed drastically in the future, and therefore improvements at a societal-level are possible.

Despite being the most prevalent chronic disease condition globally, dental caries is seldom reported in the news save for the rare occasions where it is extremely headlines worthy, such as the case where a 12-year old American boy (Deamonte Driver) passed away because of an untreated tooth abscess arising from dental caries (Otto, 2017). In this regard, DPH trainees and practitioners can utilise the humanities (in the form of literature, narrative dentistry, and art) as useful media to showcase the plight of the poor and the injustice of oral health inequities. This is needful because sometimes key stakeholders and policy makers (who usually do not have healthcare backgrounds) may not quite comprehend or relate to quantitative data, whereas the narrative aspects such as the description of the individuals’ experience can be very emotive to nudge those stakeholders and policy makers towards the right direction. Editors and reporters of traditional media channels are more likely to publish articles and editorial pieces that are deemed ‘headlines worthy’ with a compelling story to tell.

To highlight the potential power of humanities in telling a story, the author would like to quote a passage from the novel ‘Les Miserables’ by Victor Hugo (originally published in 1862), that depicts the emotional and physical pain of those who were forced to sell their teeth out of dire economic circumstances; which was a fairly common practice in European society of that time.

Excerpt from Les Miserables (Hugo, 1982, p. 177 – 178):

He was an itinerant dentist selling sets of false teeth, opiates, powders, and elixirs… seeing Fantine laugh, the dentist cried:

‘You’ve got a fine set of teeth, my lass. If you’d care to sell me your two incisors I’ll pay you a gold napoleon for each.’

‘What are my incisors?’

‘Your two top front teeth.’

‘How horrible!’ exclaimed Fantine.

‘Two napoleons,’ grumbled a toothless old woman standing near. ‘She’s in luck!’

Fantine fled, covering her ears to shut out the man’s hoarse voice as he shouted after her:

‘Think it over, my girl. Two napoleons are worth having. If you change your mind you’ll find me this evening at the Tillac d’argent.’…

When Marguerite entered Fantine’s room next morning… she found her seated cold and shivering on her bed… and it seemed that she had aged ten years overnight.

‘Lord preserve us!’ cried Marguerite, ‘What’s the matter with you?’

‘Nothing is the matter with me,’ said Fantine, ‘I’m happy. My baby isn’t going to die of that dreadful disease for lack of medicine.’

She pointed to two napoleons that lay gleaming on the table.

‘A fortune,’ murmured Marguerite. ‘A fortune! Where did you get them?’

‘I earned them,’ said Fantine.

She smiled as she said it, and the candle lighted her face. It was a bloodstained smile. There were flecks of blood at the corners of her mouth and a wide gap beneath her upper lip.

Notes on Contributors

The author conceived the ideas stated in this personal review article and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for this personal view article.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares that there is no potential conflict of interest.

References

Chong, G. T. F. (2012). Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s 1825 treatise on the mouth and ingestion. Singapore Dental Journal, 33(1), 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdj.2012.10.002

Chong, G. T. F., & Tseng, P. (2011). A review of the uses of fluoride and outcomes of dental caries control in Singapore. Singapore Dental Journal, 32(1), 14-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0377-5291(12)70011-1

Hugo, V. (1982). Les Miserables. Penguin Classics.

Marti, K. C., Mylonas, A. I., MacEacher, M., & Gruppen, L. (2019). Humanities in predoctoral dental education: A scoping review. Journal of Dental Education, 83(10), 1174-1198. https://doi.org/10.21815/JDE.019.126

Otto, M. (2017, June 13). How can a child die of toothache in the US? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017 /jun/13/healthcare-gap-how-can-a-child-die-of-toothache-in-the-us

*Gabriel Chong

Singapore Armed Forces HQ Medical Corps,

701 Transit Rd,

Singapore 778910

Email: g.chong@mail.com

Submitted: 6 May 2023

Accepted: 12 September 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 92-94

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/PV3054

Bhuvan KC1 & Pathiyil Ravi Shankar2

1School of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Australia; 2IMU Centre for Education, International Medical University, Malaysia

I. INTRODUCTION

Learning spaces can be physical, virtual, or hybrid spaces where students engage with the learning material and interact with peers and facilitators. Traditionally, learning spaces used to be classrooms, lecture halls, laboratories, and libraries and would include a teacher and students working inside a fixed space using a blackboard/whiteboard, PowerPoint projector, boards, and flexible/fixed seating arrangements. With the advancement in educational methodologies and incorporation of technology and newer applications, learning spaces now include simulated laboratories, online learning platforms, and virtual and augmented reality-based platforms. Using virtual spaces students can interact and learn from wherever they are living/staying.

The healthcare sector has a demand for personalised and precision medicine, teleconsultation, artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted devices and programs, health/clinical applications, health informatics, and robotics along with the need for healthcare and clinical services and medicines. However, there has not been enough research and discussion around the built-in environment i.e., learning spaces in health sciences education and the activities of teaching and learning (Temple, 2007). Against this backdrop, we need to examine how students use learning spaces to interact and engage with the learning material in our current environment and think about how we can optimise the learning spaces for active learning and make them more impactful and future-ready.

II. LEARNING SPACES

Learning spaces in health sciences must consider the unique needs of these subjects in terms of teaching and learning activities, student engagement, and hands-on sessions. Learning spaces design are domain specific and must cater to the teaching and learning needs of the discipline. Designing learning spaces for health sciences is challenging. Learning space can have a significant impact on teaching and learning experiences. A well-designed learning space can help students in many ways:

- It can promote student engagement, is always inviting and comfortable, and stimulating for students. They can sit together and discuss a case or work on a project (Wilson & Randall, 2012).

- A nice and comfortable multi-purpose space can help students engage in project work. They can move the seating to suit their group’s needs, write on the table surface, and whiteboards and discuss, charge their laptops, and use the internet to interact in virtual spaces. Interactive classrooms could make instruction more efficient and effective. More research is needed on the effect of learning space design on students’ engagement and the outcomes of teaching and learning. Health sciences students engage in formal and informal learning, peer support and discussion, clinical case practice and use different diagnostic equipment.

- A well-designed and well-equipped classroom can allow teachers to design workshops and activities that engage students in groups. A flexible learning space can help teachers be more creative and innovative in their approach. Flexible learning spaces provide pedagogical opportunities and support innovative practices that are not easily provided by traditional learning spaces (Benade, 2019). Health Sciences schools must think of ways to design and use learning spaces to promote active learning and help students learn clinical decision-making, required skills, therapeutic reasoning, clinical examinations, and other important practical skills.

- A well-designed learning space can promote collaboration and enhance creativity among the students. A learning space where students can interact face to face, bring their devices, and use tables, boards, and other tools will promote better collaboration and learning. However, one significant challenge is to have enough collaborative learning rooms to accommodate students; multipurpose tables, boards, and other teaching aids and devices are important given that space is at a premium, especially in urban centres (Jamieson, 2003; Van Joolingen et al., 2005). Hybrid learning spaces may partly address this problem.

III. DESIGNING A COLLABORATIVE LEARNING SPACE

To design a collaborative learning space for health sciences we must examine how learning occurs. Active learning plays an important role. There is extensive use of technology in learning. We use interactive whiteboards, create personalised learning environments, wireless networks and the internet, interactive software such as PollEverywhere, Slido and MyDispense, games, applications, etc. to engage with learners in a physical, virtual, or hybrid environment. So, our first consideration is to have a learning space that is flexible, accommodative, supports technologies used for teaching and learning, and is sustainable. Some steps that we can include in our planning and design of learning space can be:

1) Define the learning objectives: The first key consideration while designing a learning space is to look at the programme learning objective. We need to evaluate what students want to achieve in terms of learning outcomes and what skills do they need to acquire for that programme/subject. For campuses running multiple programmes collaboration across the discipline is needed during the planning stage to look at learning spaces that can work for multiple disciplines. Health sciences students gain specialised skills for patient care, including clinical competence, interdisciplinary collaboration, ethics, cultural sensitivity, and patient communication.

2) Consider the size and layout: The learning space must have adequate room to fit all the pupils in the group, necessary furnishings, and equipment. Consider the programme’s enrolment and the activities that the learners will take part in. The layout should encourage student collaboration and active learning.

3) Utilise technology: Technology plays a significant role in modern-day learning. Our subjects/programmes are managed via online platforms like Moodle, CANVAS, Blackboard, etc. Post-COVID Universities/ Schools are running their programmes in a hybrid fashion. Integrating the latest technology, especially the information and communication technology (ICT) based applications and built-in system seems to be vital when we deliver our programmes through online platforms. Tests are run via online quizzes and electronic assessment platforms.

4) Flexibility in learning spaces: Flexibility is the key consideration when designing a learning space in modern classrooms. These learning spaces must be customisable to accommodate the various learning requirements of the students in a flexible learning environment.

5) Optimise lighting and acoustics: Lighting and acoustics are critical factors that can impact learning. It is important when we want to use a virtual environment for immersive learning or play a video to demonstrate 3D- anatomical illustrations. Ensure the learning space has adequate lighting, and acoustics are optimised to minimise noise levels and distractions.

6) Emphasise sustainability: When designing the learning space, sustainability should be a top priority. To lessen the environmental impact and foster a healthy learning environment, incorporate sustainable materials and designs.

7) Encourage collaboration: Active learning requires collaboration, which is a crucial component. Think about including group tables, breakout rooms, and collaborative learning spaces.

8) Customisation of learning spaces: Learning spaces (formal or informal) must be accommodative. For example, a learning space must fit multiple activities like workshops, lectures, problem-based learning, small group discussions, simulation activities, etc. Thus, having flexible elements like collapsible walls, movable desks and chairs, computers on wheels, and foldable furniture and equipment will be ideal from a customisation perspective.

IV. CHALLENGES IN DESIGNING LEARNING SPACES

Learning space design is challenging especially for health and medical sciences programmes because of the specialisation and the complexities of the curriculum and its requirements. It is even more challenging for resource limited settings where universities and schools are struggling to deliver high quality teaching and learning even in traditional environments. These challenges are manifold:

1) Health sciences curricula are content-rich but traditionally taught didactically. Designing learning spaces, crucial for activities like problem-based learning, clinical skill practice, and immersive anatomy learning, presents challenges due to their specialised requirements. Altering spaces to these needs is complex.

2) Keeping the learning spaces human centred is another challenge given the rapidly changing teaching and learning delivery methods brought about by information technology. The pedagogy must be the priority and technology must support it and make it more efficient.

3) Designing learning spaces involves multiple priorities. There are elements like curriculum/content requirement, disability access, collaborative learning, and use of technology. Creating a learning space balancing these elements is a challenge, especially for educational institutions in low resource settings.

4) Designing adaptable learning environments that embrace evolving technologies and teaching methods is complex. A versatile collaborative space, equipped with tables, chairs, digital tools, and virtual platforms, must serve diverse students and activities. This challenge is intensified in resource-limited settings, where maintaining physical and virtual elements, costly online resources, and internet quality pose additional hurdles.

V. CONCLUSION

Learning spaces need proper focus. Health science programs are undergoing major structural transformations. Thus, our learning space must be coordinated with active learning pedagogy and philosophy. While designing learning spaces we must consider flexibility, comfort, technology, collaboration, and safety to build a collaborative and futuristic learning space that allows students to engage with their learning content and achieve the required learning outcomes.

Notes on Contributors

BKC contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript, wrote the first draft, revised the subsequent draft, and contributed to the final draft. PRS contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript and critically revised the first draft. He contributed to the subsequent revision and finalisation of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this article.

Declaration of Interest

The authors would like to declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

References

Benade, L. (2019). Flexible learning spaces: Designed for inclusion? New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 54(1), 53-68.

Jamieson, P. (2003). Designing more effective on‐campus teaching and learning spaces: a role for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 8(1-2), 119-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144042000277991

Temple, P. (2007). Learning spaces for the 21st century: A review of the literature. Retrieved from https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/learning-spaces-21st-century

Van Joolingen, W. R., de Jong, T., Lazonder, A. W., Savelsbergh, E. R., & Manlove, S. (2005). Co-Lab: Research and development of an online learning environment for collaborative scientific discovery learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(4), 671-688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.10.039

Wilson, G., & Randall, M. (2012). The implementation and evaluation of a new learning space: a pilot study. Research in Learning Technology, 20(2), 14431. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.14431

*Bhuvan KC

Discipline of Pharmacy, School of Clinical Sciences,

Queensland University of Technology,

2 George Street, Brisbane, Qld, Australia

Email: kc.bhuvan@qut.edu.au

Submitted: 17 August 2023

Accepted: 21 December 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 87-91

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/SC3114

Isharyah Sunarno1,2, Budu Mannyu2,3, Suryani As’ad2,4, Sri Asriyani2,5, Irawan Yusuf 2,6, Rina Masadah2,7 & Agussalim Bukhari2,4

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 2Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 3Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 4Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 5Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 6Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 7Department of Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction: The study aimed to ascertain how the faculty at the Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University perceived their role as a tutor during a problem-based learning activity during the academic phase of medical education, based on the length of time they acted as a tutor.

Methods: This was prospective observational research with an explanatory sequential mixed-method design, which was performed at the Undergraduate Medical Study Program, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, from January 2023 until May 2023. Research subjects were divided into two groups: a) the Novice group and b) the Expert group. Quantitative data were collected by giving a questionnaire containing six categories with 35 questions and distributed by Google form. An independent t-test was used to compare the faculty’s perception, with a p-value <.05 significant. Followed by Focus Group Discussion (FGD) for qualitative data, which then were analysed by thematic analysis. The last stage is integrating quantitative and qualitative data.

Results: There were statistically significant differences in seven issues between the two groups. Most of the tutors in both groups had favorable opinions, except for the expert group’s disagreement with the passive role of the tutor in the tutorial group. Eight positive and twelve negative perceptions were found in the FGD.

Conclusion: Most tutors positively perceived their role in PBL, with the expert group having more dependable opinions and well-reasoned suggestions.

Keywords: Problem-Based Learning, Undergraduate Medical Education, Focus Group Discussion

I. INTRODUCTION

The transition from teacher-centered to student-centered learning occurs with the introduction of active learning based on the needs of the students. The majority of effective active learning activities in the classroom were created in small groups using the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) approach. PBL has no worse outcomes in terms of academic performance and is more effective than conventional methods at enhancing social and communication skills, problem-solving abilities, and self-learning abilities, and allows the students to collaborate while integrating science, theory, and practice (Trullàs et al., 2022; Wiggins et al., 2017). A tutor or a facilitator is a pertinent element for the success of tutorial activities in PBL, thus evaluating periodically their perception and understanding about PBL activities, will help determine the need for resource development at the faculty level. Based on the aforementioned background, the author is intrigued to understand how the faculty at the Undergraduate Faculty of Medicine at Hasanuddin University perceived their role as a tutor during a PBL activity based on the duration they acted as a tutor.

II. METHODS

Short-case PBL tutorial is the model being implemented in our institution. An explanatory sequential mixed-methods observational prospective design study was carried out from January 2023 to May 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants (ethics approval recommendation number: 99/UN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2022). The study was conducted in three stages (Figure 1):

A. Stage 1

Gathering quantitative data via a survey disseminated using Google form, after which the information was analysed using SPSS version 25. The Likert scale, which ranged from 1 (extremely disagree) to 5 (extremely agree), was used to evaluate the 35 items in the questionnaire that served as the study’s primary data collection tool (Table 1 which is openly available on Figshare). The validity and reliability test for the study’s questionnaire was carried out as the first step and the Pearson Correlation was used to examine the outcome; all questions were valid with Cronbach’s α .951. The next step was to collect data through convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria were lecturers who: have attended training to become PBL tutors, are actively involved in PBL activities, and are willing to participate in the research projects to completion. Exclusion criteria were lecturers who were not familiar with the Google form application. Subjects with other commitments that prevented them from finishing the research activities and with a conflict of interest in continuing the study were considered dropouts. The research participants were split into two groups: the novice group (participants who served as tutors for less than five years) and the expert group (participants who served as tutors for five years or more). The Slovin formula was used to determine the minimum sample size, and the result was 32 people for each group. Characteristics of the study subjects were presented descriptively. An independent t-test was used to compare the faculty’s perception of their role as a tutor during a problem-based learning activity, with a p-value <.05 significant.

B. Stage 2

Focus Group Discussions (FGD) were held to collect qualitative data. The participants in the FGD were divided into two groups using the identical criteria utilised for the quantitative group categorisation, and each group consisted of six subjects. Each participant received a set of open-ended questions to be discussed during the FGD. All events and discussions were recorded, and then all conversations were transcribed using the VERBATIM app. MAXQDA 2020 was then used to tag and categorise the data. Thematic analysis was used to assess qualitative data. We used an audit trail and triangulation during data collection and conducted a peer review during data analysis to ensure the validity of the qualitative data.

C. Stage 3

Integrating quantitative and qualitative data was performed by linking data, followed by integration at the interpretation and reporting level which was conducted by integration through a narrative with a weaving approach.

III. RESULTS

A. Characteristics of the Subjects

The subjects in the novice groups were all under 45 years old, but the expert group was predominately made up of older faculty members. Both groups were predominately female. At the time of the research, medical doctors dominated the novice group, but the expert group included people with a range of educational backgrounds. Characteristics of the study subjects are openly available in Table 2 on Figshare.

B. Quantitative Data

Seven question items from four categories significantly differed between the novice and expert groups as shown in Table 3 which is openly available on Figshare.

C. Qualitative Data

Thematic analysis from the FGD revealed that the expert group only has negative perceptions, whereas the novice group has both negative and positive perceptions. The data are openly available in Table 4 on Figshare.

D. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

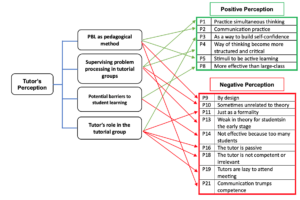

Faculty staff has the same perception about almost all concepts about the role of a PBL tutor, except for seven concepts that were statistically significantly different (Figure 1):

1) PBL as Pedagogical Method: Q5 (group tutorials help students share experiences) and Q9 (PBL is a great tool for student learning) were significantly different, with the majority of the novice group agreeing with it while the majority of the expert group were extremely agreeable. Nevertheless, while the novice had a positive perspective shown in the discussion, the expert expressly stated that “(PBL) increased the (student’s) ability to discuss but not the depth of knowledge.”

2) Supervising Problem Processing in Tutorial Groups: Q12 (I function as a resource person in the group) and Q13 (I participate in creating a positive work environment for the group) were significantly different, with most of the novice group agreeing to the concept while the majority of the expert group were extremely agreeable. The novice group stated in the FGD that “PBL is very effective for building students’ analytical skills because the students can interact with each other to express their opinions and find key problem-solving strategies.” Both groups had the same perception that some tutors attended the PBL activities “just as a formality.” Q17 (I am sensitive to the wishes of the students regarding their need for support) was also significantly different, with most participants in both groups agreeing that tutors are sensitive to the student’s need for support, but 5.71% of the novices extremely disagreed. In contrast, none of the experts in the expert group disagreed with the concept. From the FGD results, the expert group suggested that the “tutor should give feedback and guidance to the students”.

3) Potential Barriers to Student Learning in PBL: the majority of both groups agreed that the group size is just right from a tutorial point of view (Q24), but the novice group had a wide range of responses (from extremely disagree to extremely agree), while 77.14% of the expert group agreed. “Six to eight students in one PBL group” is an elaborate suggestion made by the expert group as a result of the FGD.

4) There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the role of the tutor, which is usually passive in the tutorial group (Q29), with the expert group’s consensus on the matter being unfavorable, whereas the novice group’s responses were evenly split between neutral and disagree. The FGD’s results revealed that the novice merely stated, “If the students had a misleading concept, the tutor could not be kept silent,” whereas the expert suggested, “The tutor should be the chairman of the group discussion,” and “Questions and keywords must be made by the tutor.”

Figure 1. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

IV. DISCUSSION

PBL can be regarded as a multidisciplinary method that allows the learners to resolve real-life problems and situations in every aspect, learn how to construct new information meaningfully, put away the understanding of ready-to-use knowledge, and acquire critical thinking skills. Problem processing or facilitation is a challenging task (Aydogmus & Mutlu, 2019). Since PBL can be used in specific topics and can break up the monotony of traditional didactic teaching, it has become a popular alternative teaching strategy for undergraduate medical students. It can also be used as a method of integrated teaching. Overall, it is a great tool for students learning (Gadicherla et al., 2022).

The group size is one of the possible obstacles to students’ learning in PBL. All students will not be able to participate in a team that is too big. A team that is too small could not have enough members to address the learning objectives or enough diverse opinions to guarantee a robust discussion. The tutor should be aware of how the participants play their roles, noting those who do not contribute to debates or who are silent. Therefore, they must pay close attention to what is happening in the group process to intervene and provide feedback, promoting the participants’ individual and group progress. The tutor can assist the student in identifying their requirements through motivated evaluations and simple feedback, fostering the growth of self-confidence, autonomy, and, ultimately, integration into group dynamics. PBL teams ideally consist of 6–10 students (Dent et al., 2017).

V. CONCLUSION

Aside from seven concepts, both groups mostly had positive perceptions about their role as tutors, with the expert group having more dependable opinions and well-reasoned suggestions.

Notes on Contributors

Isharyah Sunarno made the following contributions to the study: conceptualised, created the initial draft and study design, investigated and collected data, conducted formal analysis, looked for research references, performed critical revision of the article, reviewed and edited the article, and approved the study’s final published version.

The following are the contributions Budu Mannyu made to the study: provided insights into the methodology, suggested research references, served as a peer reviewer of the study’s findings, performed critical revision of the article, and gave his approval of the final draft to be published.

Suryani As’ad contributed the following to the study: she offered insights into the methodology, proposed research references, served as a peer reviewer of the study’s findings, revised the article critically, and approved the final draft of the manuscript to be published.

The study benefited from Sri Asriyani’s efforts, which included: suggestion for research references, peer review of the study’s findings, and performed critical revision of the article.

The following contributions were made to the study by Irawan Yusuf: peer reviewing of the result, supervising the research activities, and critical editing of the publication.

The following are the contributions Rina Masadah contributed to the study: provided ideas into the original draft, supervised the research activities, and edited the publication critically.

Agussalim Bukhari made the following contributions to the study: offered insights into the methodology, oversaw the research activities, critically revised the final version of the article.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee Faculty of Medicine Hasanuddin University with recommendation number: 99/UN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/ 2022.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary material for research instrument in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23646918

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the tutors who participated in this study. A special appreciation is given to Ichlas Nanang Affandi and A. Tenri Rustam from the Psychology Study Program, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University for their valuable support throughout the research process, including their role as the facilitator of the FGD. We also would like to thank Andriany Qanitha and the CRP team from Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University for their support in developing the manuscript. We are also grateful to the Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University for providing us with the resources and support we needed to complete this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Aydogmus, M., & Mutlu, A. (2019). Problem-based learning studies: A content analysis. Turkish Studies-Educational Sciences, 14(4), 1615–1630. https://doi.org/10.29228/turkishstudies.23012

Dent, J. A., Harden, R. M., & Hunt, D. (2017). A practical guide for medical teachers (5th ed.). Elsevier.

Gadicherla, S., Kulkarni, A., Rao, C., & Rao, M. Y. (2022). Perception and acceptance of problem-based learning as a teaching-learning method among undergraduate medical students and faculty. Azerbaijan Medical Journal, 62(03), 975–982.

Trullàs, J. C., Blay, C., Sarri, E., & Pujol, R. (2022). Effectiveness of problem-based learning methodology in undergraduate medical education: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03154-8

Wiggins, B. L., Eddy, S. L., Wener-Fligner, L., Freisem, K., Grunspan, D. Z., Theobald, E. J., Timbrook, J., & Crowe, A. J. (2017). ASPECT: A survey to assess student perspective of engagement in an active-learning classroom. CBE Life Sciences Education, 16(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-08-0244

*Isharyah Sunarno

Jl. Perintis Kemerdekaan Km. 11,

Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University

+62411-585859

Email: isharyahsunarno@gmail.com

Submitted: 20 April 2023

Accepted: 19 October 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 70-80

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/OA3044

Xiang Ren Tan1,2, Anthony J Goff1 & Li Whye Cindy Ng1,3

1Health and Social Sciences, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2Human Potential Translational Research Programme, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Department of Physiotherapy, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Objective structured clinical examinations have traditionally been used to assess clinical skills. However, these face-to-face clinical assessments were hindered by physical and social restrictions imposed during COVID-19. This created a need to develop novel approaches for reliable assessment of clinical skills. We explored and evaluated a virtual exercise teleconsultation assessment (VETA) to replicate a teleconsultation setting where physiotherapy students were assessed on exercise prescription and coaching skills.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional mixed-methods study using convenience sampling. A VETA was implemented for 172 physiotherapy students via Zoom to allow synchronous interaction with standardised patients (SPs). 67 students and 9 SPs completed two separate post evaluation surveys on themes relating to administration, support, authenticity, effectiveness, and value of the VETA. Likert-type responses were categorised as positive, neutral, or negative while coded qualitative responses were consolidated into themes by inductive content analysis.

Results: 76% of students agreed that the assessment was authentic while 93% felt that the SPs were realistic and believable. Responders also highlighted important challenges including the limited camera viewing angle, time and space constraint, adequacy of equipment and reliability of connectivity. Exploratory factor analysis of responses revealed three latent constructs: (1) clarity of assessment, (2) clinical relevance, and (3) value of assessment.

Conclusion: Despite the technical challenges, VETA demonstrated clarity and value as an alternative assessment and showed relevance to future telehealth practice, which is increasingly pervasive in clinical settings. This paper demonstrates a feasible approach for the virtual assessment of clinical competencies.

Keywords: Health Sciences Education, Virtual Assessment, Clinical Skills, OSCE, Physiotherapy, Exercise Prescription

Practice Highlights

- The ability to assess students non-obtrusively allows for fair assessment with reduced anxiety.

- Despite several technical challenges, VETA demonstrated value as an alternative assessment.

- An appropriate context of use, content validity and authenticity of virtual assessment are crucial.

- VETA format may be used for distant learning and remote assessment of clinical competency.

- Virtual care delivery should be included as part of healthcare professionals’ formal training.

I. INTRODUCTION

Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) have traditionally been used to assess clinical competencies and skills important for registration, licensing, and certification with professional bodies. OSCEs were first developed by Harden (Harden et al., 1975) and have commonly been used as an assessment tool for clinical competency in both medical (Gormley, 2011; Jo & An, 2014; Shirwaikar, 2015) and allied health professions (Barra-Ortiz et al., 2021; Edwards & Martin, 1989; Silva et al., 2011; Wessel et al., 2003). OSCEs can be conducted as a formative or summative assessment (Chisnall et al., 2015) and have been described as the gold standard for clinical assessment (Norman, 2002) due to its objective, precise, and reproducible nature which allows for standardised testing across a wide range of clinical skills (Zayyan, 2011). OSCEs can strengthen links between theory and practice, improving the professionalism and readiness of allied health students to perform clinical work (Farahat et al., 2015). Hence, OSCEs form vital assessments in structured health sciences programs.

However, the recent COVID-19 pandemic with strict social distancing measures and lockdowns have posed great challenges to the delivery of teaching and authentic assessments (Kumar et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2020). This is especially pertinent to health sciences education where the use of OSCEs has been limited by physical and social restrictions imposed in response to COVID-19. Therefore, there was a need to explore novel ways to create authentic settings for objective, precise and reproducible assessments of clinical skills, despite the lack of physical contact. Virtual assessments, including virtual OSCEs, have been widely implemented across many educational institutions due to COVID-19 lockdown and restrictions (Pettit et al., 2021). Importantly, virtual OSCEs appear to be effective assessments for clinical skills, notwithstanding some limitations, in medical and pharmacy courses (Blythe et al., 2021; Deville et al., 2021; Grover et al., 2022; Hannan et al., 2021; Major et al., 2020; Prettyman et al., 2018). Virtual OSCEs have been performed using common web-based teleconferencing platform such as Zoom due to its familiarity, convenient features, and stability (Grover et al., 2022; Hannan et al., 2021; Major et al., 2020; Prettyman et al., 2018). Remote proctoring and lock-down browsers can also be employed in virtual OSCEs to ensure integrity of assessment (Deville et al., 2021). However, the conduct of virtual OSCEs varies across institutions and there are no standardised guidelines or format to date.

Virtual OSCEs can be useful to assess some but not all clinical skills required of allied health students ranging from health assessment, diagnostic skills, physical and manual therapy to patient education. During the pandemic, we conceptualised an online synchronous approach, Virtual Exercise Teleconsultation Assessment (VETA), to assess the exercise prescription and coaching skills in undergraduate physiotherapy students (Tan & Ng, 2022). The intention is to replicate a teleconsultation setting where students remotely interact with standardised patients (SPs) to prescribe and coach exercises. Teleconsultation has been defined as “synchronous or asynchronous consultation using information and communication technology to omit geographical and functional distance” (Deldar et al., 2016). With the rapid and drastic changes in COVID-19 restrictions, VETA was designed with streamlined focus on three key guiding principles: (1) validity and authenticity, (2) ease of conduct, and (3) safety. These principles are aligned to the educational principles of OSCE set out in the AMEE guide (Khan et al., 2013) encompassing construct validity, reliability (with the use of rubrics, experienced examiners, and trained SPs), feasibility, and educational impact (relating to authenticity).

To ensure (1) assessment validity and authenticity, the use of standardised patients was retained in the assessment process, as opposed to replacing with case scenarios only or role-play by faculty. The live interactions with trained SPs promote realism and allow students to navigate the complexities of effective patient communication (Lovink et al., 2021; Rickles et al., 2009). The use of trained SPs also enhances the consistency and reliability of testing and at the same time, provides a safe, learner-centred environment (Cleland et al., 2009). Simulating a real clinical setting, the students interacted with the SPs independently without visible presence of examiners. To provide a uniform examination environment, VETA was entirely conducted on campus instead of relying on home-based virtual assessment.

In addition, emphasis has been placed on the (2) ease of conduct where Zoom teleconferencing was used as this is familiar to both the faculty and students who have used the platform extensively for online learning purposes. All assessment-related resources including laptop and exercise equipment were duly provided. This helped to eliminate any potential test anxiety arising from inexperience with the use of new technology or unfamiliar teleconferencing platform. Lastly, the (3) safety of students, SPs and examiners was prioritised under the COVID-19 climate. Students and SPs resided in different parts of the campus during the assessment, and the students followed a prearranged schedule for the exam to avoid any physical interactions. All personnel wore their masks at all times, even when interacting in Zoom. The SPs and examiners were situated in the same room during the assessment, with the examiner seated a safe distance away from the SP while allowing observation. These measures ensured the least interactions across all groups and minimised risk of disease transmission.

VETA was implemented as a summative assessment in an exercise physiology module within the BSc Physiotherapy programme at Singapore Institute of Technology to assess the exercise prescription and coaching skills of physiotherapy students in a simulated teleconsultation setting. We aim to evaluate the perceptions and overall experience of students and SPs towards VETA as a virtual assessment to evaluate its potential strengths and limitations. We further explored latent constructs from students’ responses to understand our survey tool’s characteristics and its reliability in evaluating themes in clinical assessments. In this study, we examined the feasibility and value of an online synchronous approach for assessing clinical skills critical to allied health students, which may provide key insights on the future transformation of clinical skills assessments.

II. METHODS

A. VETA Procedures

As part of the necessary measures to adopt new assessment methods during the COVID-19 pandemic, a convenience sample of Year 1 B.Sc Physiotherapy students underwent a VETA in July 2021. All exam procedures were conducted at the Singapore Institute of Technology Dover campus. Students and SPs situated in two different venues where separate laptops have been set up to connect on Zoom platform for facilitating interactions across the two venues.

Students were instructed to report to the exam venue at their allocated timing where they were ushered to a reading station for 10 minutes. A case scenario was provided for students to conduct planning of exercise prescription for the SP (representing the same patient in the case scenario). After the reading station, the students proceeded to an enclosed room with the laptop connected to the SP. They were given a total of 10 minutes to interact with the SP to (1) conduct Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) to ascertain the patient’s fitness to exercise, (2) provide a cycling exercise prescription and instruct him/her how to use a cycling ergometer bike, and (3) provide a resistance exercise prescription and coach them on how to perform the stated exercise safely. For the latter, similar resistance exercise equipment (resistance bands and dumbbells of different weights) was provided in both venues to facilitate the coaching of exercise. The amount of time left in the assessment (e.g., 5 minutes left), and the end of the assessment were indicated by different ringing bells.

SPs were allowed to seek clarification on the exercise prescription or coaching as necessary. The examiner was seated in the same room as the SP but was out-of-sight from the laptop web camera viewing angle. This is to replicate an authentic teleconsultation environment during the assessment. As compared to other similar virtual OSCE (Grover et al., 2022; Major et al., 2020), VETA goes beyond basic patient communication and consultation as it additionally includes an intervention aspect where SPs follow students’ instructions to perform a prescribed exercise safely.

Students’ performance was evaluated by three trained examiners (teaching faculty) who were experienced assessors for face-to-face OSCE for at least three consecutive years. All examiners used a standardised marking schema which was modelled closely to the existing schema used for physical OSCEs to maintain the same rigour and intent in the assessment of clinical skills.

B. Evaluation of VETA

After the assessment, the students and SPs completed two separate self-administered questionnaires. The students completed the survey on the Qualtrics® platform while SPs were provided with hardcopy forms to fill. Both mixed-methods surveys consist of 5-point Likert-type questions, and open-ended questions to gather qualitative responses. Participation in the surveys was voluntary and anonymous.

Initial design of the surveys was modelled after a recent paper (Fouad et al., 2019) that has conducted similar survey-based evaluation of students, staff and SPs’ perceptions towards an OSCE. After refinement of themes relevant to our VETA format, the student’s survey contained 26 items (23 Likert-type, 3 open-ended) which evaluated their overall experience and perceived difficulty of VETA, and five themes including the (1) administration, (2) support or resources provided, (3) authenticity, (4) effectiveness, and (5) value of VETA as a novel assessment mode. The open-ended questions gathered students’ qualitative inputs on their challenges faced, opinions on effectiveness of VETA and the potential areas of improvement. The SP’s survey contained 10 items (6 Likert-type, 4 open-ended) evaluating their overall experience and three themes including (1) administration, (2) student performance and (3) acceptability of VETA. The open-ended questions gathered SPs’ qualitative inputs on their challenges faced and the potential areas of improvement.

C. Statistical Analysis

Survey responses were coded and exported from Qualtrics® platform or manually input into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation). For 5-point Likert-type questions, responses such as “strongly agree/disagree” and “somewhat agree/disagree” were combined during analysis to represent a consensus perception (agree, neutral or disagree) towards a subject statement. Descriptive statistics of survey responses in percentages was compiled and displayed in summary tables. Individual open-ended responses were condensed into codes and eventually consolidated into common categorical themes using the inductive content analysis approach (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Categorical themes were identified from the codes and were subsequently grouped into two overarching themes of VETA strengths and limitations.

Exploratory factor analysis was performed using SPSS software Version 20 to explore the underlying latent conceptual structure (Watkins, 2018) present in the student’s responses to the survey variables. This allows the assessment of congruency between the pre-identified themes in the survey and the latent constructs. Factor extraction was performed with Principal Axis Factoring analysis with varimax rotation. There were no missing data. Criteria on factor extraction was based on the Kaiser rule with eigenvalues > 1.0. Only subsets of unique factors with individual loadings above 0.4 were retained. Internal consistency of the items was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient with an alpha value between 0.7 and 0.9 representing a measure of satisfactory internal consistency (Downing, 2004).

III. RESULTS

A total of 172 students completed the VETA. 67 students (39% of cohort) and 9 SPs (100%) completed the respective surveys. Out of all responders, 93% of the students and all SPs expressed an overall positive experience for VETA. 60% of the students felt that the assessment was of moderate difficulty. 22% of the students have expressed that VETA was somewhat difficult while 17% felt it was somewhat easy, with 1 student (1%) responded that it was extremely easy.

A. Perceptions Towards VETA

A summary of response statistics for Likert-type items can be found in Table 1. More than 90% of students agreed that the instructions to perform each activity were clear and that they were aware of the assessment requirements. However, only 77% agreed that the time allocated for teleconsultation was sufficient, with 16% who felt that the time was insufficient. The majority of the students were satisfied with the assessment environment and Zoom setup, however 10% felt that resources and equipment provided were inadequate.

76% of them agreed that the assessment was an authentic reflection of clinical setting while 93% of students felt that the SPs were realistic and believable. More than 90% of the students agreed that VETA was a fair and valid assessment. Most students (79%) concurred that VETA should remain as a form of assessment. 61% of the students agreed that VETA offered more learning opportunities than other exams, with 11% who disagreed with the statement.

All SPs agreed that the administration of VETA (briefing instructions and Zoom setup) was adequate, and they were comfortable with the new VETA format. However, only 78% agree that instructions given by students were clear and they were able to follow the instructions without difficulty. 89% of the SPs felt confident to perform the activities independently with the given instructions. This suggests the inadequacy of some students to effectively communicate, prescribe and coach exercises to the SPs.

|

Items (For Students; n=67) |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Themes |

|

1. Briefing instructions and information given prior to the assessment were helpful. |

88 |

8 |

4 |

|

|

2. Instructions to perform each activity were clear. |

91 |

3 |

6 |

|

|

3. I was aware of the information needed for each task in the assessment. |

93 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

4. Tasks asked to perform were fair. |

97 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

5. Time allocated for reading and planning (10 min) was sufficient. |

94 |

6 |

0 |

|

|

6. Time allocated for teleconsultation (10 min) was sufficient. |

78 |

6 |

16 |

|

|

7. The environment where the assessment was conducted was conducive. |

90 |

4 |

6 |

Support |

|

8. The audio/video quality of the Zoom session was adequate. |

94 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

9. Resources and equipment provided for the assessment were adequate. |

82 |

8 |

10 |

|

|

10. The standardised “patients” were believable and realistic. |

93 |

3 |

4 |

Authenticity |

|

11. Settings and context of given case scenario were authentic. |

97 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

12. The interaction with the standardised patient was authentic. |

91 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

13. VETA without the presence of an assessor was helpful. |

90 |

9 |

5 |

|

|

14. The VETA was an authentic reflection of clinical setting. |

76 |

19 |

5 |

|

|

15. The VETA helped to identify gaps in knowledge. |

85 |

12 |

3 |

Effectiveness |

|

16. The VETA helped to identify weaknesses in communication and patient-care skills. |

93 |

6 |

1 |

|

|

17. The VETA tested appropriate skills required for a Physiotherapist. |

87 |

9 |

4 |

|

|

18. The VETA covered a wide knowledge range. |

88 |

9 |

3 |

|

|

19. The VETA should remain as a form of assessment. |

79 |

15 |

6 |

Value |

|

20. The VETA offered more learning opportunities than other exams. |

61 |

28 |

11 |

|

|

21. The VETA was a valuable practice and learning experience. |

93 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

Items (For Standardised Patients; n=9) |

|

|

|

Themes |

|

1. Briefing instructions given before the assessment were helpful and sufficient. |

100 |

0 |

0 |

Administration |

|

2. The quality of the audio/video was adequate. |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

3. Instructions given by students to perform each activity were clear and I was able to follow the instructions without difficulty. |

78 |

22 |

0 |

Student |

|

4. I am confident to perform the activities independently with the given instructions. |

89 |

11 |

0 |

|

|

5. Communication by the students were appropriate and professional. |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

6. I am comfortable to receive instructions from a teleconsult session by a student in an exam setting. |

100 |

0 |

0 |

Acceptability |

Table 1. Response frequency for Likert-type questions

B. Strengths and Limitations

From the inductive content analysis of qualitative responses (Table 2), the VETA strengths were (1) reduced student anxiety, (2) relevance to practice and (3) assessment effectiveness. These were identified from students’ responses where they expressed that having the examiner off-screen helps to reduce their level of anxiety during assessment and they felt that VETA was relevant to their future practice where they may be required to conduct telehealth or telerehabilitation sessions. One key highlight is the authenticity of VETA where a student mentioned that he or she felt like a real physiotherapist giving the prescription, which affirmed that VETA replicates an authentic teleconsultation setting.

The limitations were identified to be related to (1) time and space allocation, (2) environment & equipment provided, (3) assessment effectiveness and (4) technical issues. There were similar sentiments from the SPs and students that the space provided for performing exercise was constrained. Students preferred more time allocated for teleconsultation. Furthermore, the students hoped to have visual feedback on timing during assessment and more exercise equipment to be provided. For assessment effectiveness, some students expressed that more clarity can be provided regarding the assessment rubric and expectations. Some of them felt that VETA was not reflective of a physical clinical setting. Last but not least, there were technical issues faced including the muffling of voices due to mask-wearing, connectivity issues that led to delays, and limited viewing angle of the laptop camera.

|

Themes |

Sub Themes |

|

|

VETA |

Reduced Student Anxiety |

|

|

“Having the assessor off-screen and not physically beside me really helped me focus on what I wanted to deliver to the patient. It also makes me feel less nervous and anxious and it has definitely helped me perform better” |

Students’ |

|

|

“Don’t see any invigilator, not so scary” |

||

|

Relevance to Practice |

||

|

“It is a good alternative assessment especially during Covid or future epidemics…open another option for both clients and PTs to conduct sessions remotely” |

||

|

“It is good to train us in telehealth because it gives us the opportunity to help patients who may have difficulty coming to the clinic even after the pandemic” |

||

|

“VETA was a great innovation with COVID-19… we might have to do telerehab for our patient and this would actually equip us with the skills to do so” |

||

|

Assessment Effectiveness |

||

|

“Felt that the zoom VETA was well organised and helped us cover the main objective of the module” |

||

|

“It is an effective examination tool as it is going to be a very practical thing to do in the near future” |

||

|

“The patients were great. The fact that I’ve never seen them before, coupled with how they responded and interacted with me during the VETA made this “consultation” more believable and I really felt like a physiotherapist giving an exercise prescription” |

||

|

VETA |

Time & Space Allocation |

|

|

“More time can be given to have more interactions with the patient. It felt like i was just instructing the patient without time for the patient to reply back.” |

Students’ |

|

|

“Would have liked more space to move backwards to demo exercise to patient, but chair was a bit in the way” |

||

|

“Maybe allocate more space in student’s room so that if they need to move in order to demo…. they are not restricted by the room size” |

SPs’ quotes |

|

|

“I have to adjust a few times in order to get my whole body into the screen for the candidate to see properly and complete the task assigned” |

||

|

Environment & Equipment |

||

|

“A clock timer to keep track of time would have been helpful” |

Students’ |

|

|

“Put a timer so that students are able to track how much time they have left. the bell was quite soft and some students might have missed it” |

||

|

“The environment can be slightly better as it was rather dark and the papers were messy” |

||

|

“More weights to cater exercises that require two arms” |

||

|

Assessment Effectiveness |

||

|

“Would be nice if rubric was released earlier” |

Students’ |

|

|

“Would be beneficial to give a sample case study…so that we have a clearer expectation of the exam” |

||

|

“…resistance training component of Zoom VETA was limited to upper limb exercises only” |

||

|

“It does not feel reflective of a real clinical setting as physically, we would have to consider many other factors such as conducting proper handrub before and after the activity, cleaning the equipment as well” |

||

Table 2. Qualitative responses for perceptions towards VETA

C. Common Constructs in Survey Evaluation

From the original questionnaire (21 Likert-type items categorised into 5 themes), a smaller subset of 13 items were retained after factor analysis and they were categorised and defined as 3 main latent constructs: (1) Clarity in assessment, (2) Clinical relevance, and (3) Value of assessment. The loadings of individual factor (>0.4) and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (>0.7) are displayed in Table 3. It was noted that some of the items previously grouped under the topic of “effectiveness” has been subsumed under either the clinical relevance or value of assessment constructs. Other items were omitted as their loadings were <0.4 or they were not unique in representing any of the latent constructs.

|

Items (n=13) |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

Constructs |

|

1. Briefing instructions and information given prior to the assessment were helpful. |

0.743 |

Clarity of Assessment |

||

|

2. Instructions to perform each activity were clear. |

0.785 |

|||

|

3. I was aware of the information needed for each task in the assessment. |

0.796 |

|||

|

10. The standardised “patients” were believable and realistic. |

0.754 |

Clinical |

||

|

11. Settings and context of given case scenario were authentic. |

0.782 |

|||

|

12. The interaction with the standardised patient was authentic. |

0.790 |

|||

|

15. The VETA helped to identify gaps in knowledge. |

0.548 |

|||

|

16. The VETA helped to identify weaknesses in communication and patient-care skills. |

0.681 |

|||

|

14. The VETA was an authentic reflection of clinical setting. |

0.741 |

Value of |

||

|

18. The VETA covered a wide knowledge range. |

0.803 |

|||

|

19. The VETA should remain as a form of assessment. |

0.518 |

|||

|

20. The VETA offered more learning opportunities than other exams. |

0.788 |

|||

|

21. The VETA was a valuable practice and learning experience. |

0.607 |

Table 3. Latent constructs from exploratory factor analysis

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Keeping Pace with the Digital World