What dress code do we teach students and residents? A survey of patients’ and their families’ preferences regarding physicians’ appearance

Submitted: 1 September 2023

Accepted: 29 January 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 32-40

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/OA3127

Michiko Goto1, Ryota Sakamoto2, Hideki Wakabayashi3 & Yousuke Takemura4

1Department of General Medicine, Mie University School of Medicine, Japan; 2Department of Medical Informatics, Mie University Hospital, Japan; 3Department of Community Medicine, Mie University School of Medicine, Japan; 4Department of General Medicine, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Japan

Abstract

Introduction: From the late 1960s to the present, physicians’ dress codes have been actively studied in Western countries. Until the early 21st century, patients tended to prefer a conservative dress style, such as “shirt and tie or skirt” with white coats for physicians. However, as attitudes toward dress codes have changed, knowledge regarding this issue needs to be updated. A variety of colours of scrubs are currently commonly used by medical professionals, but it is not known whether all colours are acceptable to patients. The current study sought to investigate the acceptability of various dress codes for physicians from the patients’ perspective, to inform medical education.

Methods: Outpatients and their family members at a university hospital and a small-to-medium-sized hospital were surveyed. We inquired about which of the different styles of white coats and different colours of scrubs were most desirable for male and female physicians. We used Scheffe’s paired comparison method to determine rankings.

Results: Patients and their family members expected their physicians to wear white coats rather than scrubs. Furthermore, a more traditional and formal dress code was preferred. The least preferred colour of scrubs was yellow.

Conclusion: The current results indicated that patients’ preference for a traditional, conservative appearance has not changed over time. This finding does not match current perspectives on infection prevention. Both patient preferences and infection prevention are important for informing education and gaining patient trust.

Keywords: White Coat, Scrub Colour, Physicians’ Appearance, Medical Education, Doctor-Patient Communication

Practice Highlights

- The physician’s traditional white coat may be associated with a sense of trust, and is most preferred by patients and their family members. This trend has not changed over time.

- Among the scrub colours, bright colours are not preferred, and black and red may have a negative meaning for patients and their family members.

- Regarding dress code education, patient/family perspectives, infection prevention, and sociocultural background should all be considered.

I. INTRODUCTION

Hippocrates proposed that physicians should “be clean in person, well dressed, and anointed with sweet smelling unguents” (Hippocrates, 1923). However, it has not been proven that physicians’ appearance affects their competence or patients’ satisfaction (Hennessy et al., 1993; Neinstein et al., 1985; Takemura et al., 2008). Nevertheless, some researchers have reported that a physician’s appearance is “important” (Brandt, 2003) as a surrogate for proof of physicians’ competence among unfamiliar patients (Jacob, 2007), and others have given credence to this notion (Baxter et al., 2010). While the white coat is considered to be a symbol of power and authority (Bond et al., 2010), it has also been reported to be a sign of trust and credibility (Brandt, 2003; Gherardi et al., 2009; Nair et al., 2002; Rehman et al., 2005). Additionally, an unkempt appearance may be interpreted as reflecting a lack of skill and care (Gjerdingen et al., 1987).

As lifestyles have changed with the development of new materials, attitudes toward clothing have also changed. However, patients’ viewpoints regarding physicians’ clothing have not been evaluated since the end of the “formal dress: shirt and tie” era (Toquero et al., 2011). Therefore, there is a need to conduct dress code surveys to update current knowledge regarding the consequences of these changes. From the late 1960s to the present, dress codes have been actively studied in the West (Blumhagen, 1979; Gledhill et al., 1997; Menahem & Shvaretzman, 1998). Studies conducted at the beginning of the 21st century reported that patients tended to prefer physicians wearing white coats over formal attire (Keenum et al., 2003; Nair et al., 2002). In Japan, there have been very few studies of physicians’ dress codes (Ikusaka et al., 1999; Yamada et al., 2010). However, in a survey of more than 2,000 patients, Yamada et al. (2010) reported that white coats and ties worn by male physicians and knee-length skirts and white coats worn by female physicians were the dress codes considered most acceptable by patients.

The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome mainly in Canada and Asian countries east of India substantially changed the medical environment and the dress code for physicians (Au-Yeung, 2005). The “scrub,” a surgical garment that can be easily worn in medical settings, is used by many healthcare professionals as daily medical clothing, and its use has continued to increase even after the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic ended, thus making scrubs an important focus of dress code research (Gherardi et al., 2009). The bare below the elbows (BBE) policy specifies that sleeves should be rolled up to avoid infection, and research has been conducted to determine the extent to which patients are willing to accept this attire (Aitken et al., 2014; Bond et al., 2010). In 2005, Japan’s Ministry of the Environment promoted the Cool Biz initiative, which encourages workplaces to use “appropriate room temperature settings and encourage employees to wear light clothing appropriate to those temperatures during the summer months” (Ministry of the Environment, 2017). In 2011, as these changes began to spread among the general public, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, resulting in the Fukushima power plant meltdown. Emergency national energy-saving measures were implemented, which accelerated the adoption of the Cool Biz approach. The concept of Cool Biz, as promoted by the Japan government, spread rapidly, with several surveys reporting a sharp decline in the wearing of ties in offices (Nishihara et al., 2010; Nishina et al., 2007). Many hospital directors of medical institutions asked patients to accept their staff wearing light clothing during the summer, such as dressing without neckties; thus, we assume that dressing without a tie also became widespread in medical settings (Keio University Hospital, 2014). We speculate that the number of physicians who dress formally was reduced following this trend. Moreover, although no systematic evidence has been reported, as noted in a study by Kurihara et al. (2014), more doctors began to wear scrubs and Crocs-style shoes, possibly because of the influence of American TV dramas and medical films.

As a result, these changes in the environment led to confusion in medical education, with different teachers providing different dress instructions, and students having difficulty understanding the rationale for teachers’ dress instructions.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the acceptability of dress codes from the patients’ perspectives, and to inform medical education. The findings of this study may be useful for medical teachers, doctors, and medical institutions as a reference when instructing medical students and doctors regarding how to choose clothing.

II. METHODS

Convenience sampling was conducted among outpatients and their family members while they were waiting for treatment at two medical institutions: a university hospital with 655 beds in a central area of Tsu city, and a primary care centre with 82 beds in a rural area on the outskirts of Tsu city, Japan. Tsu has a population of 270,000 people, and is located 400 km south-west of Tokyo. The main industries in the city are the manufacturing of transport machinery, information and communication equipment, and foodstuffs, but there are also many agricultural workers in the surrounding area, making it a typical regional city in Japan in many respects. The study period was 3 years, from April 2012 to August 2015. The subjects were asked about their sex, age, and the department in which they were treated. The surveyed items included various styles of dress mentioned in previous studies (formal, casual, and scrubs) and variations in wearing practices that have been observed in the field (open-front white coats, masks, slippers, rolled-up sleeves, Casey [A short white coat with a closed front] short sleeves, and open-front scrubs). This ultimately resulted in nine different styles for men and seven different styles for women (excluding ties and Casey short sleeves). Moreover, 15 different colours of scrubs were selected to cover most of the available colours ones on the market (Figure 1) for a survey on undesirable colours for physician’s wear.

A. Survey

For Question 1, participants were asked to compare pictures of two doctors and to choose one of four levels of response (completely A, more like A, or more like B, completely B). Participants were instructed to choose one of them, even if it was difficult to decide.

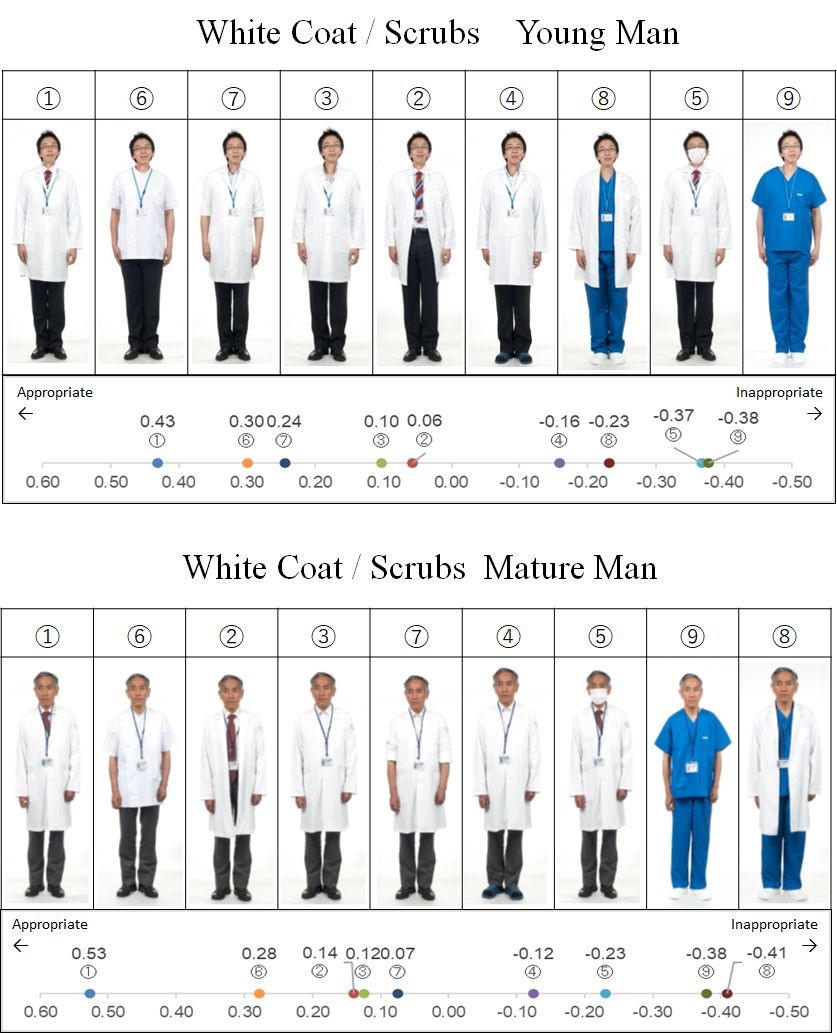

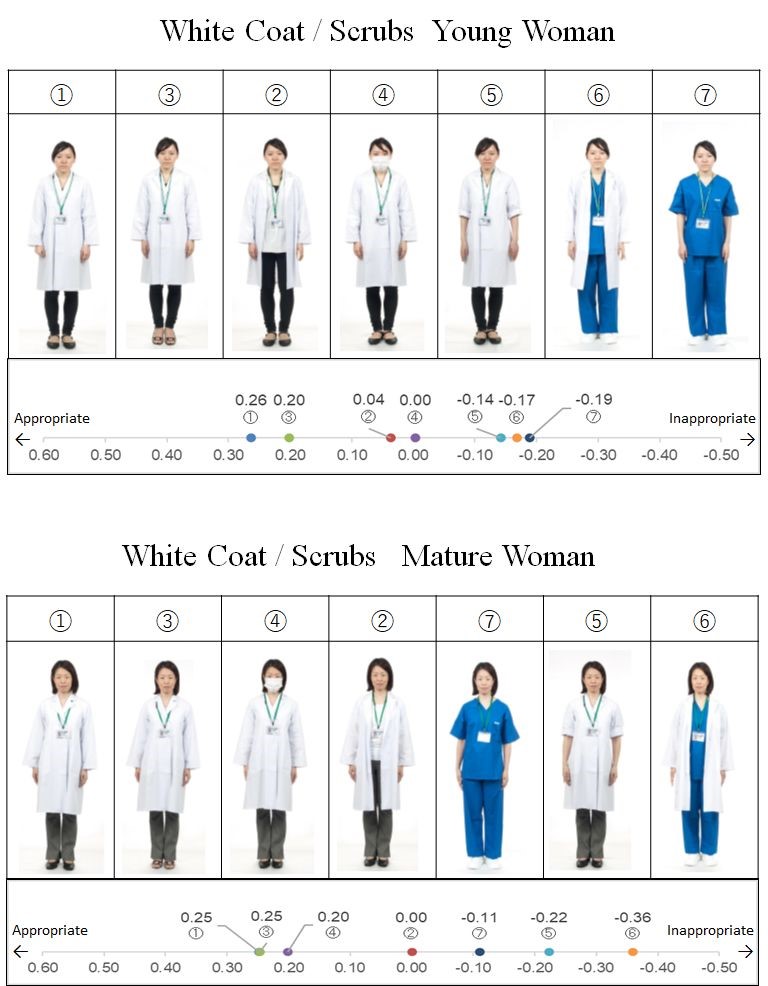

Images of nine different types of attire for male physicians and seven different types of attire for female physicians were prepared, in mature and younger versions. The nine types of attire for men were as follows: ① tie + white coat with front closed, ② tie + white coat with front open, ③ white coat with no tie, ④ slippers, ⑤ mask, ⑥ Casey, ⑦ rolled-up sleeves, ⑧ scrubs + white coat, and ⑨ scrubs. The seven types for women were as follows: ① white coat with front closed, ② white coat with front open, ③ rolled-up sleeves, ④ sandals, ⑤ mask, ⑥ scrubs + white coat, and ⑦ scrubs.

Nine photos of men in pairs (one adult version and one young version) were presented in a round-robin fashion on an iPad. Seven photos of pairs of women (one adult version and one young version) were shown in the same way. Patients and their family members were asked to compare the two photos and to select the one that they felt was more appropriate as their physician’s appearance, using four levels of response. We also asked participants to identify any images showing an “unacceptable appearance.”

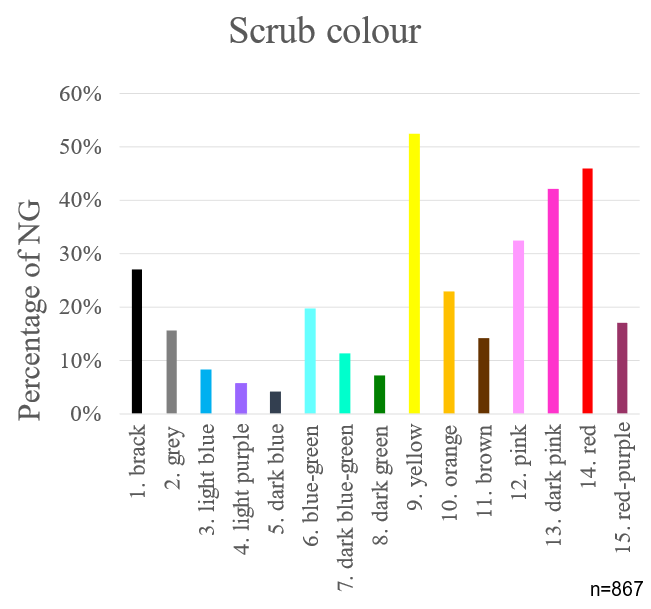

For Question 2, patients were instructed to identify any colours that they felt were not desirable for a doctor to wear. The commercially available colours used were a mix of cold and warm colours. Fifteen images of scrubs (black, grey, light blue, light purple, dark blue, blue-green, dark blue-green, dark green, yellow, orange, brown, pink, dark pink, red, and red-purple) were shown on an iPad to the subjects, who were then asked to indicate any unacceptable colours (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scrubs in 15 different colours

1: black, 2: grey, 3: light blue, 4: light purple, 5: dark blue, 6: blue-green, 7: dark blue-green, 8: dark green, 9: yellow, 10: orange, 11: brown, 12: pink, 13: dark pink, 14: red, 15: red-purple

B. Statistical analysis

For Question 1, we used Scheffe’s paired comparison method (Nakaya’s variant) to rank data as completely A +2, more like A +1; unanswered/invalid 0, more like B −1; and completely B −2, as fitted. A one-way analysis of variance was performed within subjects.

III. RESULTS

We received 869 responses regarding the appearance of young men and women, 824 responses regarding the appearance of mature men and women, and 867 responses regarding unacceptable scrub colours.

A. Question 1

1) Young men: The descending order of preference for young men was as follows: ① tie + white coat, ⑥ Casey, ⑦ rolled-up sleeves, ③ no tie + white coat, ② tie + open-front white coat, ④ slippers, ⑧ scrubs + white coat, ⑤ mask, and ⑨ scrubs (Figure 2). Clearly, ④ slippers and below constituted the subgroups, and there was no significant difference between ⑤ mask and ⑨ scrubs (Figure 2).

A total of 300 individuals reported 427 images showing unacceptable appearances, of which 42% showed the physician wearing scrubs (Table 1).

2) Mature men: The descending order of preference for mature men was as follows: ① tie + white coat, ⑥ Casey, ② tie + white coat with front opening, ③ no tie + white coat, ⑦ rolled-up sleeves, ④ slippers, ⑤ mask, ⑨ scrubs, and ⑧ scrubs + white coat. As in the case of the young men, ④ slippers and below constituted a lower group, and there was no significant difference between ⑨ scrubs and ⑧ scrubs + white coat (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nine types of attire for mature and young male physicians, each in order of patient preference with scale chart of average degree of preference

*The yard stick values were Y0.05=0.052 for young men and 0.054 for mature men

A total of 264 individuals reported 354 images showing unacceptable appearances, of which 40% showed the physician wearing scrubs (Table 1).

3) Young women: The descending order of preference for images of young women was as follows: ① white coat, ③ sandals, ② open-front white coat, ④ mask, ⑤ rolled-up sleeves, ⑥ scrubs + white coat, and ⑦ scrubs (Figure 3). Moreover, ① white coat and ③ sandals formed the top group; ② open-front white coat and ④ mask formed the middle group; and ⑤ rolled-up sleeves, ⑥ scrubs + white coat and ⑦ scrubs formed the lower group. There were no significant differences between the groups (Figure 3).

A total of 403 individuals reported 535 images showing unacceptable appearances, of which 57% featured rolled-up sleeves and 33% featured scrubs (Table 1).

|

Physician’s Appearances |

Young man n = 300 |

Mature man n = 403 |

Young woman n = 264 |

Mature woman n = 172 |

|

Tie + white coat |

0% |

2% |

|

|

|

No tie + white coat |

5% |

7% |

|

|

|

White coat |

|

|

2% |

1% |

|

Tie + open-front white coat |

18% |

17% |

|

|

|

Open-front white coat |

|

|

8% |

16% |

|

Slippers |

20% |

9% |

18% |

23% |

|

Mask |

28% |

20% |

2% |

2% |

|

Casey |

3% |

4% |

|

|

|

Rolled-up sleeves |

5% |

9% |

57% |

15% |

|

Scrub + white coat |

21% |

26% |

12% |

25% |

|

Scrub |

42% |

40% |

33% |

48% |

Table 1. The characteristics of images that were identified as showing an unacceptable appearance by patients and their family members, and the percentage of respondents that deemed the image unacceptable

4) Mature women: The descending order of preference for images of mature women was as follows: ① white coat, ③ sandals, ④ mask, ② open-front white coat, ⑦ scrubs, ⑤ rolled-up sleeves, and ⑥ scrubs + white coat (Figure 3). There was no significant difference between the components ① white coat and ③ sandals in the top group. Moreover, ① white coat and ③ sandals were components of the top group, similar to the case for images of young women, and there was no significant difference between them (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Seven types of attire for mature and young female physicians, each in order of patient preference with scale chart of average preference

*The yard stick values are Y0.05=0.054 for young women and 0.061 for mature women

A total of 172 individuals reported 222 images showing unacceptable appearances, of which 48% featured scrubs (Table 1).

We examined the trends by participants’ gender and age. The results revealed no differences between men and women and in each age group. However, participants over 70 years old tended to prefer tie + closed- and open-front white coat compared with participants under 70, and tended not to favour female doctors with rolled-up sleeves.

B. Question 2

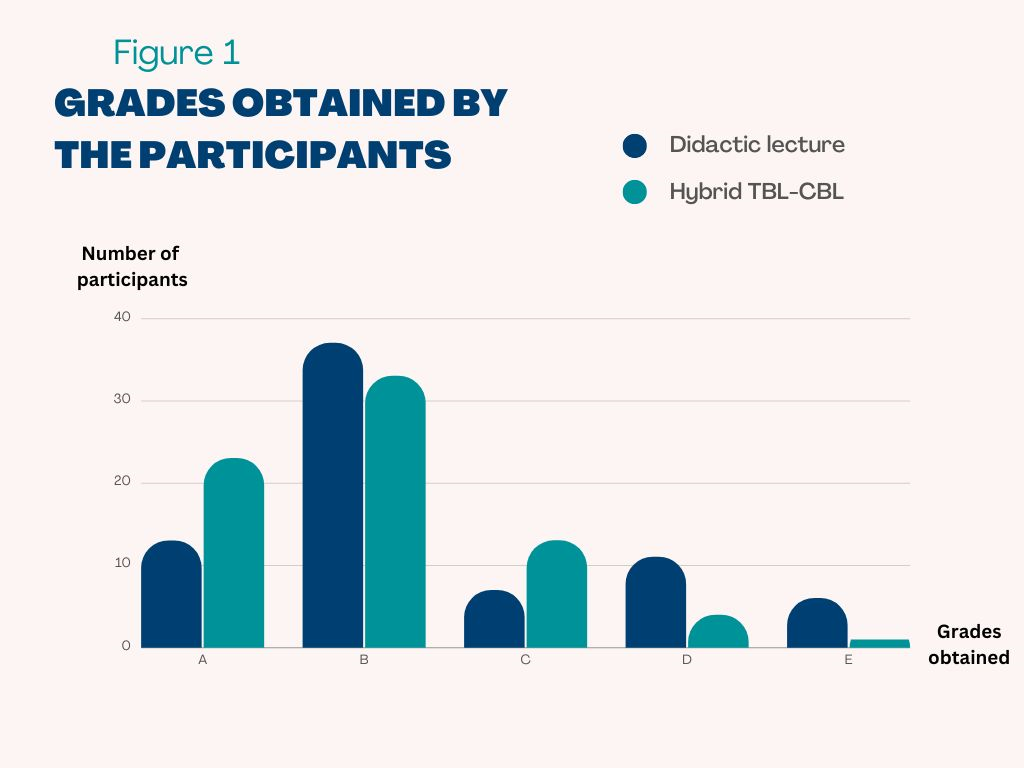

1) Scrub colour: The colours and percentages of scrubs that were identified as unacceptable were, in descending order, as follows: 52%, yellow; 46%, red; 42%, dark pink; 33%, pink; 27%, black; 23%, orange; 20%, blue-green; 16%, grey; 17%, red-purple; 14% brown; 11%, dark blue-green; 8%, light blue; 7%, dark green; 6%, light purple; and 4%, dark blue (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percentage of scrub colours not preferred by patients and their family members.

IV. DISCUSSION

Many patients and their family members expected their physicians to wear white coats rather than scrubs. On average, a traditional and formal dress style was most preferred by patients and their family members (buttoned white coat and tie for men, leather shoes, and buttoned white coat for women). In a 2010 study conducted in Japan by Yamada et al., the most favoured formality attire by patients was white coats (but skirts for women). Pronchik, who investigated the benefits of neckties prior to the BBE policy (King & Infection Prevention and Control Nurse, 2022), concluded that in an emergency room in the United States (US), patients preferred their physicians to wear ties, and patient satisfaction was high (Pronchik et al., 1998). The survey found that people in older age groups in particular preferred doctors to wear ties.

The results suggest that patients’ preferences regarding physicians’ appearance have not changed substantially. One study found that patients in the United Kingdom (UK) who were briefed on the BBE policy felt that conservatively dressed doctors looked more professional (Toquero et al., 2011).

The second-most preferred attire for male physicians was the Casey, followed by the white coat with rolled-up sleeves for younger men. However, this attire was not ranked highly for women or mature men. This indicates that patients perceived the Casey as a traditional style of dress for men, and that the preference was not necessarily based on the prevalence of the BBE concept or concerns about cleanliness. The pros and cons of rolling up the sleeves of white coats are often discussed in medical student dress guidance, including in a study by Bond (Bond et al., 2010). In the current study, rolled-up sleeves were not preferred by patients. However, it is known that the sleeves of white coats can become contaminated (Banu et al., 2012), and Wong et al. pointed out that the risk of contamination may be increased by pathogens in ties, cuffs, and pockets (Wong et al., 1991). The current results indicated that patients in their 70s and older were not comfortable with female doctors rolling up the sleeves of their white coats. Although this finding may be related to cultural factors, to the best of our knowledge, this phenomenon has not been previously reported in the literature. The results suggest that patients’ concepts of professionalism and infection prevention are not directly connected. When instructing students about dress code, they should be told that patients may not approve of rolling up their sleeves.

Men wearing masks were rated less favourably, while women wearing masks were not rated less favourably. For women, there may be something to compensate for the facial expressions hidden by masks. Because wearing a mask and other prophylactic devices has been essential for physicians since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the impressions of patients and family members should be examined in future studies.

Although scrubs are often rated as hygienic (Bond et al., 2010; Lightbody & Wilkie, 2013), the current survey revealed that scrubs were not rated as a preferred attire for physicians by patients and their family members. In the survey by Aitkin et al. mentioned above, scrubs also received the lowest ratings. However, previous studies in the US reported no influence of scrubs and other types of attire on patient satisfaction and perceptions of professionalism (Fischer et al., 2007; Li & Haber, 2005). Additionally, a recent survey in the UK reported a clear downward trend in resistance to scrubs, with a survey by Palazzo and Hocken reporting that white coats and ties are no longer expected by patients (Palazzo & Hocken, 2010). In a study in the US, patients undergoing surgery reported that scrubs were most favoured in outpatient settings (Edwards et al., 2012). These findings suggest that the resistance to scrubs in Japan may disappear in the near future.

Brightly coloured (yellow, red, and pink) and black scrubs were considered to be less acceptable than others, and those in pale and cold colours, such as dark blue and light blue, were preferred. This may have occurred because red and black are associated with negative emotions such as anger, anxiety and fear, whereas cold colours are associated with calm and quiet (Oyama et al., 1963). Some patients commented that black reminded them of death and red reminded them of blood. Bright colours may be irritating to patients. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined colour preferences for scrubs among patients, suggesting that these findings are novel.

In the 20th century, physicians in many countries were required to wear white coats (Gooden et al., 2001; Harnette, 2001). It is not surprising that preferences regarding physicians’ appearance have changed in the 21st century, as many people have started to become more familiar with the threat of infection and changes in the global medical environment. However, the concept of BBE is still not pervasive, and the appearance of attire required to be worn by physicians has not changed significantly. The current results are consistent with the findings of the largest study of this issue conducted in the UK (Jacob, 2007), which reported the following: “if there is deemed to be no significant infection risk from any given variation of workwear, our patients would like us to wear a shirt and tie.” Patients’ awareness regarding infection needs to be investigated, but patients will accept physicians’ suggestions if they understand the need for them (Collins et al., 2013).

Shelton et al. conducted an experiment in the UK to reduce cross-infection between doctors and patients, and reported that there was no significant difference in patient preferences between different types of attire before explaining the importance of clothing to patients; however, after the explanation, scrubs and short-sleeved shirts were most preferred (Shelton et al., 2010). When considering physicians’ dress code, we need to understand both the patient’s preferences and infection control factors. We propose that a dress code should be developed that does not compromise patients’ trust and confidence, but also takes safety into consideration.

A. Limitations

Although the types of clothing shown in the photos in the current study were based on a prior survey, it may not have been comprehensive. Moreover, using different models in the photographs may have influenced the results, and the potential effects of measurement bias cannot be excluded. It is unclear from the current findings why certain appearances were preferred or deemed unacceptable. Furthermore, the current study did not examine doctors’ preferences. Medical practitioners’ preferences need to be taken into account when making workplace attire choices in hospitals. Further research will be needed to identify the preferred attire for both patients and doctors.

V. CONCLUSION

The current findings indicated that patients exhibited a preference for physicians dressed in traditional attire. Even though times have changed, people may still associate trust, credibility, and respect with the formal appearance of their physicians. The current findings also suggested that patients were not aware of the BBE policy. The results of this study may be helpful for informing teaching approaches regarding the appearance of medical students and residents.

Notes on Contributors

MG developed the research idea and design with YT. The data collection was performed by MG. The data were analysed by RS. HW performed the data interpretation with MG. MG wrote the article with revision by HW. All the authors read and agreed with the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants for publication and this procedure was approved by the Mie University Ethics Committee. The Ethical Review Committee of Mie University committee approved this study (No. 1237). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this RCT study are openly available at a Figshare repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23936379.v1

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the models for their cooperation in creating the photograph stimuli, and to Goto F, Makita H, Yin M, Kasyo K, Sakaguchi R, Masukawa E, Tsunoda K, Shimada K, and Tanaka K, for collecting the data. We thank Benjamin Knight, MSc., from Edanz (https://edanz.com) for editing a draft of this manuscript. This paper has been preprinted. M Goto et al. What dress code do we teach students and residents? A survey of patients’ and their families’ preferences regarding physicians’ appearance. 23 Mar, 2022(Version 1)available at Research Square (https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1430222/v1).

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Kameyama City Department of Community Medicine [No. J12061L005] and the Tsu City Department of Community Medicine [No. J12061L008].

Declaration of Interest

No conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, exists.

References

Aitken, S. A., Tinning, C. G., Gupta, S., Medlock, G., Wood, A. M., & Aitken, M. A. (2014). The importance of the orthopaedic doctors’ appearance: A cross-regional questionnaire-based study. The Surgeon, 12(1), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2013. 07.002

Au-Yeung, P. K. K. (2005). SARS changed medical dress code. BMJ, 330(7505), 1450. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7505.14 50-b

Banu, A., Anand, M., & Nagi, N. (2012). White coats as a vehicle for bacterial dissemination. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 6(8), 1381-1384. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2012/42 86.2364

Baxter, J. A., Dale, O., Morritt, A., & Pollock, J. C. (2010). Bare below the elbows: Professionalism vs infection risk. The Royal College of Surgeons of England Bulletin, 92(7), 248-251. https://doi.org/10.1308/147363510X510581

Blumhagen, D. W. (1979). The doctor’s white coat. The image of the physician in modern America. Annals of Internal Medicine, 91(1), 111-116. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-91-1-111

Bond, L., Clamp, P. J., Gray, K., & Van Dam, V. (2010). Patients’ perception of doctors clothing: Should we really be ‘bare below the elbow’? The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 124(9), 963-966. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215110001167

Brandt, L. J. (2003). On the value of old dress code in the new millennium. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(11), 1277-1281. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.11.1277

Collins, A. M., Connaughton, J., & Ridgway, P. F. (2013). Bare below the elbows: A comparative study of a tertiary and district general hospital. Irish Medical Journal, 106(9), 272-275.

Edwards, R. D., Saladyga, A. T., Schriver, J. P., & Davis, K. G. (2012). Patient attitudes to surgeons’ attire in outpatient clinical setting: Substance over style. American Journal of Surgery, 204(5), 663-665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.001

Fischer, R. L., Hansen, C. E., Hunter, R. L., & Veloski, M. S. (2007). Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 196(2), e1-e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ajog.2006.09.043

Gherardi, G., Cameron, J., West, A., & Crossley, M. (2009). Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patient’s preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clinal Medicine, 9(6), 519-524. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.9-6-519

Gjerdingen, D. K., Simpson, D. E., & Titus, S. L. (1987). Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the physician’s professional appearance. Archives of Internal Medicine, 147(7), 1209-1212.

Gledhill, J. A., Warner, J. P., & King, M. (1997). Psychiatrists and their patients: Views on forms of dress and address. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 228-232. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp. 171.3.228

Gooden, B. R., Smith, M. J., Tattersall, S. J. N., & Stockler, M. R. (2001). Hospital patients’ views on doctors and white coat. The Medical Journal of Australia, 175(4), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143103.x

Harnette, P. R. (2001). Should doctors wear white coat? The Medical Journal of Australia, 174(7), 343–344. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143310.x

Hennessy, N., Harrison, D. A., & Aitkenhead, A. R. (1993). The effect of the anaesthetist’s attire on patient attitudes. The influence of dress on patient perception of the anaesthetist’s prestige. Anesthesia, 48(3), 219-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044 1 993.tb06905.x

Hippocrates. (1923). Hippocrates (W. H. S. Jones, Trans.) (Vol. 2). Harvard University Press.

Ikusaka, M., Kamegai, M., Sunaga, T., Narita, N., Kobayashi, H., Yonenami, K., & Watanabe, M. (1999). Patients’ attitude toward consultations by a physician without a white coat in Japan. Internal Medicine, 38(7), 533–536. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedici ne.38.533

Jacob, G. (2007). Uniform and workwear: An evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service. https://data.parliament.uk/DepositedPapers/Files/DEP2009-0656/DEP2009-0656.pdf

Keenum, A. J., Wallace, L. S., & Stevens, A. R. (2003). Patients’ attitude regarding physical characteristics of family practice physicians. Southern Medical Journal, 96(12), 1190-1194. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.smj.0000077011.58103.c1

Keio University Hospital. (2014, May 20). Cool Biz no jisshi ni tsuite [About the implementation of Cool Biz]. Keio University Hospital. https://www.hosp.keio.ac.jp/oshirase/hosp/detail/38033/

King, C., & Infection Prevention and Control Nurse. (2022). Hand hygiene policy: Including bare below the elbows (Ver.9). Leicestershire Partnership National Health Service Trust. https://www.leicspart.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Hand-Hygiene-Policy-inc-bare-below-the-elbows.pdf

Kurihara, H., Maeno, T., & Maeno, T. (2014). Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 13(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056x-13-2

Li, S. F., & Haber, M. (2005). Patient attitude toward emergency physician attire. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 29(1), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.12.014

Lightbody, K. A., & Wilkie, M. D. (2013). Perceptions of doctors’ dress code: ENT patients’ perspective. Clinical Otolaryngology, 38(2), 188-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12084

Menahem, S., & Shvaretzman, P. (1998). Is our appearance important to our patients? Family Practice, 15(5), 391-397. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/15.5.391

Ministry of the Environment. (2017, April 25). Heisei 29 nendo Cool Biz ni tsuite [About Cool Biz in 2017]. Ministry of the Environment, Japan. https://www.env.go.jp/press/103993.html

Nair, B. R., Mears, S. R., Hitchcock, K. I., & Attia, J. R. (2002). Evidence-based physicians’ dressing: A crossover trial. The medical Journal of Australia, 177(11-12), 681-682. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb05017.x

Neinstein, L. S., Stewart, D., & Gordon, N. (1985). Effect of physician dress style on patient-physician relationship. Journal of Adolescent Health Car, 6(6), 456-459. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0 197-0070(85)80053-X

Nishihara, N., Haneda, M., & Tanabe, S. (2010). A study of office workers’ clothes and subjective evaluations in an office with a preset air-conditioning temperature of 28°C in summer. Journal of Home Economics of Japan, 61(3), 169-175. https://doi.org/10.114 28/jhej.61.169

Nishina, D., Murakawa, S., & Uemura, Y. (2007). A Study on the Effects of the Cool Biz introduced into the Regional Joint Government Buildings in Hiroshima. Technical papers of annual meeting, the Society of Heating, Air-Conditioning and Sanitary Engineers of Japan. 1463-1466. https://doi.org/10.18948/shasetai kai.2007.2.0_1463

Oyama, T., Tanaka, Y., & Haga, J. (1963). Color-affection and color-symbolism in Japanese and American students. The Japanese Journal of. Psychology, 34(3), 109-121. https://doi.org/ 10.4992/JJPSY.34.109

Palazzo, S., & Hocken, D. B. (2010). Patients’ perspectives on how doctors dress. The Journal of Hospital Infection, 74(1), 30-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2009.08.021

Pronchik, D. J., Sexton, J. D., Melanson, S. W., Patterson, J. W., & Heller, M. B. (1998). Does wearing a necktie influence patient perceptions of emergency department care? The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16(4), 541-543. https://doi.org/10.1016/s07 36-4679(98)00036-5

Rehman, S. U., Nietert, P. J., Cope, D. W., & Kilpatrick, A. O. (2005). What wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patient. The American Journal of Medicine, 118(11), 1279-1286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.026

Shelton, C. L., Raistrick, C., Warburton, K., & Siddiqui, K. H. (2010). Can changes in clinical attire reduce likelihood of cross-infection without jeopardizing the doctor-patient relationship? The Journal of Hospital Infection, 74(1), 22-29. https://doi.org/10.10 16/j.jhin.2009.07.031

Takemura, Y., Atsumi, R., & Tsuda, T. (2008). Which medical interview behaviours are associated with patient satisfaction? Family Medicine, 40(4), 253-258. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18382837/

Toquero, L., Aboumarzouk, O., Owers, C., Chiang, R., Thiagarajah, S., & Amin, S. (2011, April 02). Bare below the elbows-The patient’s perspective. Webmed Central. WebmedCentral. https://www.webmedcentral.com/article_view/1401

Wong, D., Nye, K., & Hollis, P. (1991). Microbial flora on doctors’ white coats. British Medical Journal, 303(6817), 1602-1604. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.303.6817.1602

Yamada, Y., Takahashi, O., Ohde, S., Deshpande, G. A., & Fukui, T. (2010). Patient’s preference for doctor’s attire in Japan. Internal Medicine, 49(15), 1521–1526. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalme dicine.49.3572

*Hideki Wakabayashi

Department of Community Medicine,

Mie University School of Medicine,

2-174, Edobashi,

Tsu, Mie,

514-8507, Japan

+81-59-231-5290

Email address: hidekiwaka@med.mie-u.ac.jp

Submitted: 8 August 2023

Accepted: 9 January 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 50-54

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/SC3107

Chuu Ling Chan1, Russell Lee2, Lih Ing Goh1, Nathanael Hao Kai Chong1, Li Neng Lee2 & Jun-Hong Ch’ng1

1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: We frequently associate microbes with infection, rarely expounding on their usefulness and importance to healthy development. For humanity to leverage these microbial “super powers”, learners from all backgrounds need to appreciate their utility and consider how microbes could help solve some of the most critical problems we face. However, learners are frequently uninterested or intimidated by microbiology. The card game “No Guts No Glory” was created to engage students by piquing curiosity and encouraging informal learning to change perceptions and advocate the value of microbes to good health.

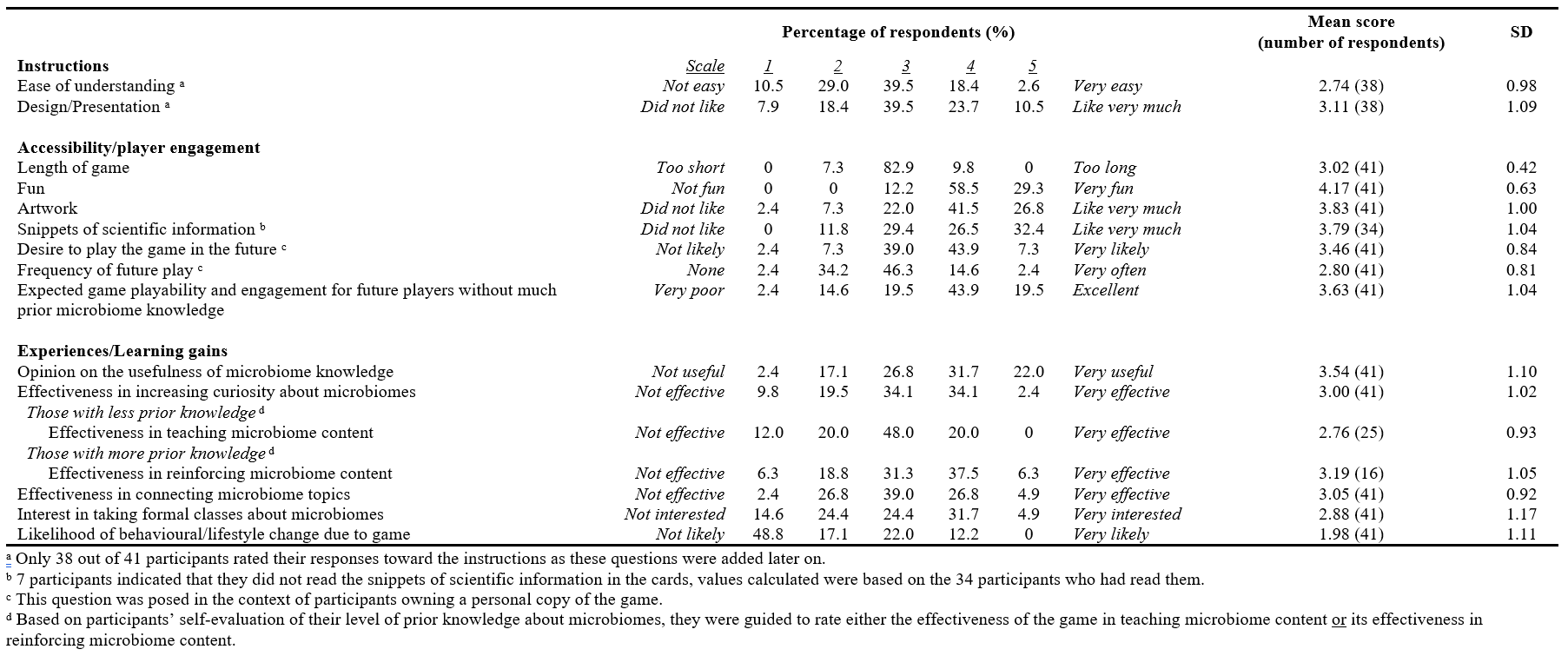

Methods: Undergraduates from various faculties in the National University of Singapore were invited to play and give feedback on accessibility, engagement and self-reported learning gains.

Results: The game was well-received across disciplinary backgrounds with positive feedback (5-point scale) on game mechanics being fun (4.17±0.63), attractive artwork (3.83±1.00) and scientific snippets (3.79±1.04), positive re-playability (3.46±0.84), player engagement for those without foundational knowledge in microbiology (3.63±1.04), and usefulness of knowledge taught (3.54±1.10). Areas for improvement evidenced from feedback included unclear instructions (2.74±0.98), limited content taught (2.76±0.93), not generating interest to attend formal microbiome classes (2.88±1.17) and not prompting lifestyle changes (1.98±1.11).

Conclusion: This pilot study provided valuable insights from the target demographic, with concrete ideas on how to improve the educational potential of “No Guts No Glory”. Findings further lay the groundwork for the design of future instruments to objectively quantify learning gains from gameplay.

Keywords: Game-based Learning, Microbiome, Microbiology, Card Game, No Guts No Glory

I. INTRODUCTION

Though responsible for infection and disease, microbes are also necessary for promoting and maintaining good health and are remarkably useful in many industries. Microbes are crucial and versatile tools which can be used to tackle some of the world’s most complex problems ranging from pandemics and climate change to sustainable foods and environmental remediation (Akinsemolu, 2018). Recognising the true potential of microbes could encourage their use in impactful problem-solving. However, students may perceive microbiology as a difficult subject and not associate microbes with anything positive. To address this, we developed the card game “No Guts No Glory” that focuses on the positive aspects of microbes, particularly in the context of the gut microbiome which is closely tied to many aspects of our health and development (Lynch & Pedersen, 2016). We sought to engage learners from diverse disciplines by reducing the psychological barrier to learning microbiology, sparking curiosity and encouraging self-directed exploration.

Previous studies on card games, including one involving immunology (a related and equally complicated subject), have demonstrated the benefits of game-based learning (Barnes, 2022; Su et al., 2014): (a) games provide an attractive, innocuous entry point for individuals to explore complex subjects in a fun and enjoyable manner; (b) they remove barriers associated with traditional learning approaches, making it easier for learners to get started and actively participate; (c) additionally, game-based learning promotes active engagement; (d) through interactive gameplay, players become immersed in theoretical concepts which fosters deeper understanding of the subject and enhances retention.

In this study, we examined the impact of playing “No Guts No Glory” on participants’ interest in microbiology and garnered feedback for optimising game mechanics, instructions and artwork in preparation for future studies on the game’s impact on learning gains.

II. METHODS

Undergraduate students from various academic backgrounds were invited to participate in this pilot study on version 1 of the microbiome card game “No Guts No Glory”. Students were briefed on the details of the study and implied consent was given with their participation. Documentation of informed consent was waived as the collection of personal, sensitive information was kept to a minimum. A total of 41 participants were recruited – 29% from Medicine, 46% from Life Sciences, 20% from Psychology and 5% from other majors. Although not enforced, most participants played the game with others from the same discipline due to the way participants were recruited and how gameplay sessions were organised.

Participants first read through the game instructions and provided feedback on the instructions before playing two rounds of the game in groups of three or four. During the first round of gameplay, participants discussed and negotiated the rules among themselves based on what they had read, without input from the session facilitator. There was a break between the two rounds when the session facilitator highlighted deviations from the intended gameplay and answered questions about the game, before proceeding to the second round of gameplay. Participants then gave feedback via Qualtrics on their experience with the game. Throughout the two rounds of gameplay, the session facilitator also recorded observations of questions about instructions, disagreements about rules, deviations in gameplay and comments about game mechanisms, artwork, experiences and learning gains.

For quantitative feedback, participants rated the clarity and presentation of the instructions, the accessibility of the game, player engagement level and perceived learning gains, based on 5-point rating scales. Open-ended qualitative questions included: 1) suggestions to improve the instructions or the game, 2) elaboration on likely lifestyle/behavioural changes after playing and 3) key ideas they had learnt about the gut microbiome.

III. RESULTS

Quantitative feedback from participants after playing “No Guts No Glory” is summarised in Table 1 and qualitative feedback (individual comments and suggestions) is accessible at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23735211

Table 1. Participants’ quantitative feedback (5-point rating scales) on the microbiome card game “No Guts No Glory”

A. Instructions

Participants rated the ease of understanding and the presentation of the instructions near average (2.74±0.98 and 3.11±1.09 respectively). Qualitative feedback on the instructions revealed that many participants felt uncertain of game components, rules and mechanics (19 participants), that phrasing and overall wordiness of the instructions could be improved (14 participants), and that the instructions lacked emphasis on the goals of the game (3 participants). They suggested the need for more examples, visuals or even a demonstration video (10 participants) and reformatting the instructions (3 participants).

B. Game Accessibility and Player Engagement

Participants agreed that the length of one game was just right (3.02±0.42) and felt that the game was fun (4.17±0.63). They also had a good impression of the artwork (3.83±1.00) and scientific snippets included on the game cards (3.79±1.04), although 7 participants did not manage to read these snippets. Most participants responded positively regarding the replayability of the game, with a likelihood of playing the game if they owned it scoring 3.46±0.84, at an average frequency of 2.80±0.8. They perceived that players without any prior microbiome knowledge would be able to play and find the game engaging (3.63±1.04). Suggestions were given to enhance the game by changing the game mechanics to enrich learning (17 participants), improving the quality of game components (7 participants), including visual aids in the instructions (6 participants), and refining the artwork aesthetics (4 participants).

C. Experiences and Learning Gains

Gameplay helped participants to recognise the usefulness of microbiome knowledge (3.54±1.10), and to a lesser degree, connect topics (3.05±0.92) and raise curiosity (3.00±1.02). Participants who indicated more prior knowledge reported that the game was moderately effective in reinforcing existing content (3.19±1.05) while those with less prior knowledge indicated that the game was less effective in teaching content (2.76±0.93). In the qualitative feedback, suggestions for improving learning gains involved linking the scientific snippets found on the cards to gameplay (4 participants), and including a quiz component in the game mechanics (3 participants). Participants showed little interest in taking formal microbiome classes after gameplay (2.88±1.17), and only half (51.2%) indicated potential behavioural or lifestyle changes: 14 mentioned changes in their diet, two mentioned an increased curiosity in microbiome-related topics while one reflected on blindly chasing lifestyle/dietary trends.

D. Key Lessons Learnt by Students from Playing the Game

Drawing on open-ended feedback from participants, the top three ideas drawn from gameplay were the importance of the gut microbiome in health (8 out of 36 responses, 22%), how our microbiome is affected by multiple factors (19.4%), and the importance and definitions of pre/pro/syn-biotics (16.6%).

IV. DISCUSSION

Based on the feedback received, the game was enjoyable, with the inclusion of both attractive artwork and intriguing scientific snippets being crucial in generating interest. Participants acknowledged the value of the information presented in the game, which could inspire them to further explore specific areas of interest on their own. Participants also agreed that the game’s entry barrier was low enough, such that even individuals without a microbiology background could comprehend the gameplay and find it engaging. Positive replayability of the game could aid learning through increased exposure to information on the cards and instructions. Notably, the game’s effectiveness in reinforcing existing knowledge received higher ratings compared to its ability to teach new content in this study, aligning with similar findings published by others (Spandler, 2016; Su et al., 2014). While positive, these outcomes need to be viewed with caution as some of the students were likely to have been from classes taught by the researchers. Although feedback was anonymous and collected in the absence of their teachers, we acknowledge that this student-teacher/researcher relationship may have inadvertently introduced bias in this study.

This study also revealed four shortcomings of the game: 1) unclear instructions, 2) ineffectiveness at teaching new content, 3) generating little interest to enrol in microbiology classes and 4) low possibility of changing lifestyles. The latter three points allude to current game mechanics being ineffective in highlighting the relevance of microbiomes to students’ lives. To assess the concordance between the game’s intended learning objectives and students’ actual learning outcomes, self-reported key takeaways were examined. Although many of the mentioned themes corresponded to the learning objectives that were established during the game development phase, it was evident that certain learning objectives were insufficiently emphasised.

With valuable suggestions provided by participants to enhance learning impact, we anticipate that the revised game (version 2), which further integrates learning outcomes with game mechanics, will better showcase the importance and relevance of microbiomes. Furthermore, student insights from the current study have facilitated the development of assessment tools for quantifying learning gains in future studies through pre- and post-play testing methodologies. Also, since “No Guts No Glory” emphasises the beneficial impact of microbes on our health, future studies could compare the impact of this game to others which emphasise disease-causing pathogens and antimicrobial resistance, especially in how they shape perceptions about microbes.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our pilot study of “No Guts No Glory” highlighted its strengths in terms of accessibility and player engagement. However, it also brought to attention areas requiring improvement. These include simplifying the instructions to enhance clarity, ensuring that learning is effectively integrated with gameplay and better aligning game mechanics with the science.

Furthermore, we have identified key learning outcomes from unsupervised gameplay which will guide the development of assessment instruments in future studies, via pre- and post-play testing. Such testing will allow us to evaluate learning gains more effectively in subsequent studies involving both microbiology and non-microbiology undergraduates.

Notes on Contributors

Chuu Ling Chan was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, project administration and supervision, data analysis and writing (original draft and editing).

Russell Lee was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, project administration and supervision, data analysis and writing (editing).

Lih Ing Goh was involved in methodology, project administration and supervision, data analysis and writing (editing).

Nathanael Hao Kai Chong was involved in project administration and supervision.

Li Neng Lee was involved in conceptualisation, methodology and writing (editing).

Jun-Hong Ch’ng was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, data analysis and writing (editing).

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed by the Learning and Analytics Committee on Ethics- Departmental Ethics Review Committee (LACE-DERC) from the National University of Singapore (NUS) Institute for Applied Learning Sciences and Educational Technology (ALSET) and Centre for Development of Teaching & Learning (CDTL), with an exemption from IRB review and the approval to conduct research at NUS (LACE Reference Code: L2021-12-01).

Data Availability

Qualitative study data can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23735211.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge all the students who participated in this study.

Funding

This study is funded by the Teaching Enhancement Grant (TEG FY2023) from the Centre for Development of Teaching and Learning (CDTL), National University of Singapore (E-571-00-0001-01).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Akinsemolu, A. A. (2018). The role of microorganisms in achieving the sustainable development goals. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018. 02.081

Barnes, R. L. (2022). A protein purification card game develops subject knowledge and transferable skills. Journal of Biological Education, 56(4), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.20 20.1799844

Lynch, S. V., & Pedersen, O. (2016). The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(24), 2369–2379. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra16 00266

Spandler, C. (2016). Mineral supertrumps: A new card game to assist learning of mineralogy. Journal of Geoscience Education, 64(2), 108–114. https://doi.org/10.5408/15-095.1

Su, T., Cheng, M.-T., & Lin, S.-H. (2014). Investigating the effectiveness of an educational card game for learning how human immunology is regulated. CBE Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 504–515. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-10-0197

*Jun-Hong Ch’ng

MD4, 5 Science Drive 2,

Singapore 117545

Email: micchn@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 9 September 2023

Accepted: 29 January 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 55-57

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/PV3134

Sean B Maurice

Northern Medical Program, Division of Medical Sciences, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, Canada; Cellular and Physiological Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

I. INTRODUCTION

Risk management is a skillset that is embedded within clinical practice. Clinicians use protective equipment to safeguard themselves from pathogens carried by patients, learn de-escalation techniques to manage violent patients, and learn to ask for help. Patients of course are also at risk, because they present with illness or injury that may get worse despite our best efforts, and because there’s always a chance of iatrogenic injury or disease. Healthcare providers dedicate themselves to healing injury and illness, and to not causing further harm. In contrast, risk management is rarely considered with regards to teaching and learning, as they are not commonly understood to involve risk. When a teaching or learning experience feels risky, but we don’t think it should, then we don’t talk about it, and this can create cognitive dissonance and discourage us from engaging in teaching and learning.

Health systems around the world need more healthcare providers, at a time when they are dealing with very significant burnout (Office of the Surgeon General, 2022). In the face of this burnout, we may not be inclined to innovate, but Eva (2022) encourages us to step up and embrace the opportunity to make change, as during challenging times, “… it is critical that every stakeholder in the medical profession strive for excellence by adapting to modern realities rather than clinging to the seemingly safe status quo.” If we need to train more healthcare providers at a challenging time, when not making change is potentially more dangerous than innovating, then we should consider the metaphor of adventure to inspire our innovations and help us think about risk management in teaching and learning.

II. RISKS IN OUTDOOR ADVENTURE

In self-propelled outdoor adventure (hiking, mountaineering, kayaking), risks are largely obvious, and consequences can be very serious, so talking about risk management is both natural and normalised. Participants engage in ‘calculated risk-taking,’ which involves identifying risks and managing them as well as possible to keep the risk at a level considered reasonable by all who partake. Prior to the adventure, risks are managed by ensuring that the team have the right skills, training, and equipment; and judgement is used in choosing the objective and monitoring conditions like the weather, or snow conditions. During the adventure, participants need to make decisions in response to changes that occur over time, including changes in the weather, or the group condition (fatigue, minor ailments like blisters); along with the unpredictable (weather that washes out a key bridge, a bear stole all your food). Additionally, in self-propelled outdoor adventures, the team are limited by the resources that they brought with them, so working as a team to overcome challenges with limited resources is inherent.

For those who choose to embark on self-propelled outdoor adventures as a leisure activity, the idea that fun can involve hard/tedious work and a degree of suffering, is not foreign. Some mountaineers proudly talk about “Type II fun,” with phrases like “It doesn’t have to be fun, to be fun” – an acknowledgement that a challenging adventure can be worthwhile even though it involves hard/tedious work, risk, and some discomfort. In fact, the reward is often greater because of the effort required (within reason). The motivation for these adventures is intrinsic, and the journey is as important as the destination.

Adventure leaders must ensure all members of the group are appropriately prepared for the challenge ahead and stay safe and engaged. This involves having the ability to teach the physical skills required, ensuring the group has appropriate equipment for the conditions, and making judgement calls as conditions change. In addition, adventure leaders need to care deeply for the wellness of participants, watching for non-verbal cues that a participant might be suffering physically or mentally, and use wisdom to decide when and how to intervene, to improve participant satisfaction, and reduce the chances of a problem escalating.

III. RISKS IN HEALTH PROFESSIONS EDUCATION

Risks in teaching and learning include the fear of public speaking (common, though rarely acknowledged), the risk of embarrassment (from getting something wrong in front of others), and the risk of losing control (if you hand over too much control to the learners and can’t reign them back in). In the clinical environment, there’s a risk of learner harm and loss of empathy if we don’t prepare and support them adequately during their training, there’s a risk of losing clinical faculty if we make unreasonable requests of them, and there’s a risk of compromised patient outcomes if we don’t consider impact on patients due to our innovations, or lack thereof.

IV. IMPLICATIONS OF AN ADVENTURE METAPHOR

A. Academic Teaching

For academic faculty, an adventure mindset might encourage learning about teaching practices and experimenting with new techniques with some risk that they might not be successful. It also encourages innovations in teaching and scholarship to meet important social needs, even if these don’t seem like the most fruitful or safe endeavours from the perspective of traditional tenure and promotion metrics. If the academy would acknowledge the importance of unconventional approaches to scholarship and teaching to meet social needs, then it would need to reconsider how it evaluates performance.

B. Clinical Teaching

There’s a growing recognition that demonstrating vulnerability and empathy, can lead to more effective patient care and more effective clinical education, while also being more rewarding for preceptors. Many physicians have long since given up wearing a lab coat, and some are comfortable being on a first-name basis with medical trainees, as part of “an ethic of caring” which ensures learners feel safe and are better able to learn (Balmer et al., 2016). When teaching while providing clinical care, the clinician needs to think about how they are perceived by the patient, as well as by the trainee. It may be possible to balance the need to maintain credibility, while being vulnerable and modelling the clinical reasoning process for both student and patient, by exhibiting “Intellectual Candour” (Molloy & Bearman, 2019). Showing vulnerability and empathy might seem like a loss of formality, and this might feel risky, yet if this is a calculated risk, with opportunities for gain in the form of a more meaningful teaching experience and more impactful learning for students, then this might be a worthwhile adventure to embark on.

C. Underserved Populations

Some of the most medically underserved people in Canada (and globally), are rural and Indigenous peoples. If we are trying to train more healthcare providers to meet the needs of equity deserving groups, we need to consider how we are currently discouraging this. If cultural safety is not always experienced by Indigenous peoples (especially on their own, colonized lands), we need to keep cultural safety at the top of our list of priorities and we need to invest in it. If we currently provide a largely specialist curriculum which discourages rural generalist practice, we need to look at how we can make the curriculum more of a generalist curriculum. If we acknowledge that family practice has become less appealing as many family physicians now work in clinics with more limited scope, and less longitudinal relationships with patients (albeit more reasonable hours), then we should consider how to better support learners to consider full scope family practice.

In discussions about the characteristics of rural family physicians who provide full scope care, people often talk about ‘rational risk takers,’ as physicians who are more willing to accept risk, because they work in locations where timely access to specialist and subspecialist care is often not available, and working near or beyond the limit of their training is the alternate to seeing some patients not receive care at all. This is a form of calculated risk-taking and has recently been described as “Clinical Courage” (Konkin et al., 2020). If clinical courage is necessary for care providers serving our most underserved populations, then we need to encourage it, to reduce the healthcare provider maldistribution. This means ensuring that characteristics of clinical courage are embedded: when admitting students to our programs, in both our pre-clinical and clinical curricula, and in our assessments, for all learners.

V. CONCLUSION

Teaching and learning in the health professions should be fun, though a serious sort of fun. Our learners are now much more diverse than in the past, and they are advocating for needed changes in the healthcare system, while our clinicians are struggling. If we must innovate to sustain and improve what we do, then an adventure metaphor will encourage and inform how we approach this.

Health professions programs should ensure that working as a team, managing risks, and overcoming challenges with limited resources, are embedded within our curricula. We should also focus on intrinsic motivations of learners and faculty, and emphasise the importance of the journey, alongside the destination. Our systems need to ensure that clinical faculty have the capacity to care about the wellbeing of learners, alongside providing patient care. Embracing the metaphor of adventure should help invigorate our teaching and learning, and counteract burnout, while we work towards needed change in our health systems.

Notes on Contributors

The author conceived and wrote this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The idea for this manuscript came from the author’s teaching philosophy and teaching dossier prepared for the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 3M National Teaching Fellowship (2022 recipient). The idea has been shared at the Centre for Health Education Scholarship (CHES) Day of Scholarship (October 2022), the International Congress on Academic Medicine (ICAM, April 2023), and the Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC, May 2023) and the idea has been improved and clarified through the critical feedback of peers at these meetings.

Funding

No funding was required for this study.

Declaration of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest, including financial, institutional, or other relationship that might lead to bias.

References

Balmer, D. F., Hirsh, D. A., Monie, D., Weil, H., & Richards, B. F. (2016). Caring to care: Applying Noddings’ philosophy to medical education. Academic Medicine, 91(12), 1618-1621. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001207

Eva, K. W. (2022). An open letter to all stakeholders involved in medicine and medical education in Canada. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 13(4), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.75549

Konkin, J., Grave, L., Cockburn, E., Couper, I., Stewart, R. A., Campbell, D., & Walters, L. (2020). Exploration of rural physicians’ lived experience of practising outside their usual scope of practice to provide access to essential medical care (clinical courage): An international phenomenological study. BMJ Open, 10, Article e037705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037 705

Molloy, E., & Bearman, M. (2019). Embracing the tension between vulnerability and credibility: ‘Intellectual candour’ in health professions education. Medical Education, 53(1), 32-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13649

Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). (2022). Addressing health worker burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on building a thriving health workforce. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf

*Sean B Maurice

3333 University Way,

Prince George, BC,

Canada, V2N 4Z9

1-250-960-5443

Email: sean.maurice@unbc.ca

Submitted: 19 October 2023

Accepted: 25 March 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 58-60

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/CS3159

Wing Yee Tong1, Bin Huey Quek1, Arif Tyebally2 & Cristelle Chow3

1Department of Neonatology, KK Women and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 2Emergency Medicine, KK Women and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 3Department of Paediatrics, KK Women and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Neonatology is considered a ‘niche’ paediatric subspecialty. Most junior doctors posted to the department have limited prior exposure to the neonatal population, and require quick and effective training to help them function safely on the clinical floor. In recent years, postgraduate medical teaching has found the use of blended learning to be effective (Liu et al., 2016). Blended learning is defined as a combination of classroom face-time with online teaching approaches, and there is currently paucity of literature on its efficacy in ‘up-skilling’ relatively inexperienced healthcare professionals in a subspecialty setting. Hence, the aim of this study was to design and evaluate the efficacy of a blended-learning orientation programme in improving neonatal clinical knowledge and procedural skills amongst junior doctors.

II. METHODS

A. Study Setting and Participants

This study was set in the largest academic tertiary paediatric hospital in Singapore.

B. Curriculum Development

We adopted the Kern’s six-step approach for curriculum development (Thomas et al., 2022), as it systematically identifies and addresses learner needs, and its cyclical nature also allows for constant modifications and improvements.

1) Step 1: Problem identification and general needs assessment

We conducted a quantitative survey to identify the general issues with our current programme, which consisted of daily face-to-face, largely didactic lectures over the first month of the posting. We noticed that many junior doctors missed teaching sessions due to work obligations, resulting in ‘piecemeal’ and ineffective learning. The one-month programme was also considered excessively lengthy.

2) Step 2: Targeted needs assessment

Most junior doctors considered themselves to be ‘novice’ learners in neonatology. This emphasised the importance of starting with foundational teaching concepts to avoid overwhelming them. Junior doctors also preferred interactive learning methods.

3) Step 3: Goals and objectives

Our main objective was for the junior doctors to be competent and safe members of the clinical team, with basic neonatal clinical knowledge and the ability to perform and assist in neonatal procedures.

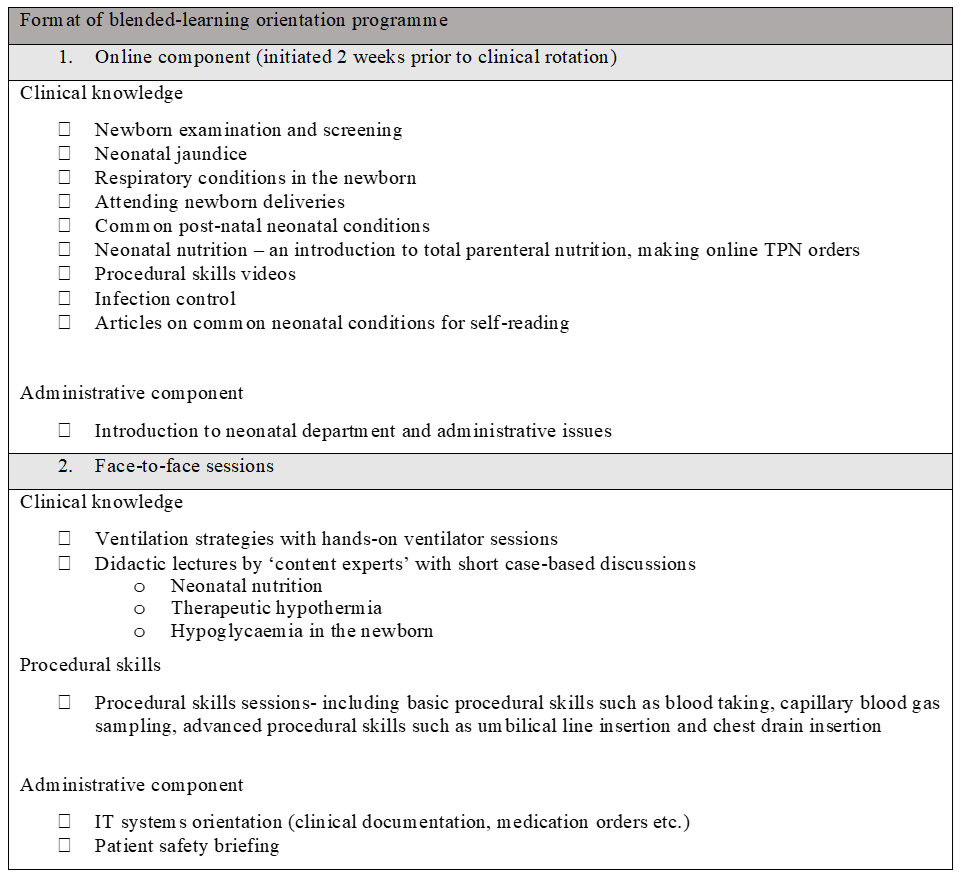

4) Step 4: Educational strategies: Course content development

We identified a list of core topics and procedural skills which formed the programme curriculum (Figure 1).

The teaching format was changed from mainly didactic lectures to case-based scenarios in both online and face-to-face sessions, as this has been shown to better motivate students towards self-directed learning and develop problem-solving skills. Case-based scenarios would also facilitate greater peer discussion and interactivity amongst learners in the face-to-face sessions.

We worked with IT specialists to convert specific topics to six online learning modules, and included interactive components such as clickable elements and narration to better engage learners (Choules, 2007). Each module was designed to be completed within 30 minutes.

For neonatal procedural skills, learners were expected to watch online demonstration videos created by the department prior to attending hands-on practical sessions.

Figure 1. Outline of blended-learning orientation programme

5) Step 5: Implementation

The blended learning programme was implemented with junior doctors across two batches from July 2022 to January 2023. Majority were from post-graduate year three to five, with approximately half having no prior working experience in neonatology. All participated in the face-to-face sessions and completed the online modules.

We used our institution’s online learning management system to deliver the e-learning modules, and department faculty members conducted the face-to-face sessions. Designated ‘protected teaching time’ was implemented to facilitate attendance during office hours.

6) Step 6: Evaluation and feedback

We designed a pre-and-post-programme assessment consisting of 24 multiple-choice questions covering the following aspects – (1) clinical scenarios with interpretation of laboratory and radiological results, (2) factual knowledge and (3) questions on procedural skills.

The junior doctors also completed an online survey which assessed the learners’ perceptions on blended learning. Consent for the survey data to be used for research was implied in their participation.

III. RESULTS

The junior doctors had a positive experience with blended learning. All participants agreed that the learning content was relevant and appropriate for their level of experience. Almost all participants felt that there was ease of access to the online learning modules, with minimal technical issues. Learners also found specific online modules such as respiratory conditions ‘useful’, but enjoyed the face-to-face nature of sessions such as ventilatory strategies, as it gave them the opportunity to clarify doubts with their facilitator. Overall, the duration of the face-to-face orientation sessions was halved, and there was a significant improvement in the mean MCQ score.

IV. DISCUSSION

A blended learning programme designed for novice learners in Neonatology is effective in preparing junior doctors for clinical work.

Learning theories suggest that adult learners are motivated to invest time in learning if they understand its relevance (Taylor & Hamdy, 2013). The shift towards case-based learning bridges theory and practice, and motivates participation in clinical decision-making. This is an effective form of learning as demonstrated by an improvement in the mean post-test MCQ score of the participants. The experience was also deemed a positive one in qualitative feedback. In addition, the accessibility of online modules provided learners with autonomy to control their pace of learning. However, it is important to strike the right balance between online and classroom teaching, as learners still value the interactivity offered by face-to-face teaching.

We should work to create a supportive infrastructure to support blended learning methods by training more clinician-educators in online learning approaches and designing ‘reusable’ learning resources, which can be modified and integrated into other medical courses in future (Singh et al., 2021).

The limitations of our study include reliance on multiple choice tests to assess knowledge, and a lack of formal evaluation of procedural skills. Competency-based evaluations, as well as practical skills evaluations can be implemented in future runs to evaluate the efficacy of the courses.

V. CONCLUSION

Technology enhanced learning is fast becoming an integral part of medical education. Through this study, we demonstrate that blended learning programmes can be successfully integrated into the training of junior doctors in a subspecialty setting.

Notes on Contributors

WT led the design and conceptualisation of this work, implemented the education programme, and drafted the manuscript. BQ provided feedback and guidance on creating the content of the education programme. CC provided guidance on the evaluation of teaching programme. CC, AT and BQ provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors approve the publishing of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors received a Singhealth Duke-NUS Academic Medicine Education Institute Education Grant 2021 (funding number EING2205) to support the development of curriculum content for our programme.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Choules, A. P. (2007). The use of elearning in medical education: A review of the current situation. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 83(978), 212-216. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.05 4189

Liu, Q., Peng, W., Zhang, F., Hu, R., Li, Y., & Yan, W. (2016). The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), e2.

Singh, J., Steele, K., & Singh, L. (2021). Combining the best of online and face-to-face learning: Hybrid and blended learning approach for COVID-19, post vaccine, & post-pandemic world. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(2), 140-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472395211047865

Taylor, D. C., & Hamdy, H. (2013). Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Medical Teacher, 35(11), e1561-e1572. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2013.828153

Thomas, P. A., Kern, D. E., Hughes, M. T., Tackett, S. A., & Chen, B. Y. (Eds.). (2022). Curriculum development for medical education: A six-step approach. Johns Hopkins University Press.

*Tong Wing Yee

100 Bukit Timah Road

Singapore 229899

Email: tong.wing.yee@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 19 September 2023

Accepted: 9 January 2024

Published online: 2 July, TAPS 2024, 9(3), 61-63

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-3/CS3137

Yoshikazu Asada1, Chikusa Muraoka2, Katsuhisa Waseda3 & Chikako Kawahara4

1Medical Education Center, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 2School of Health Sciences, Fujita Health University, Japan; 3Medical Education Center, Aichi Medical University, Japan; 4Department of Medical Education, Showa University, Japan

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 epidemic has prompted the spread of ICT-based education, with many university classes being conducted remotely. Some education systems use asynchronous tools such as learning management systems (LMSs); others use synchronous tools such as web conference systems. This trend has affected not only lectures but also exercises among students and clinical practice. Game-based education is no exception, and classes that require direct face-to-face interaction have become difficult to implement. Escape rooms (ERs) are one example of game-based education.

ERs are defined as “live-action team-based games where players discover clues, solve puzzles, and accomplish tasks in one or more rooms in order to accomplish a specific goal (usually escaping from the room) in a limited amount of time” (Nicholson, 2015). Originally intended for entertainment purposes, ERs now also serve educational purposes (Davis et al., 2022). As an educational tool, ERs are mainly used for teaching specific content knowledge and content-related skills, general skills, and affective goals (Veldkamp et al., 2020). In addition, since ERs are categorised as game-based education, they are also useful for motivating students.

ERs may be conducted either face-to-face or online. Online-based ERs, known as “Digital Educational Escape Rooms” (DEERs), have become common since the COVID-19 pandemic (Makri et al., 2021). DEERs combine the (1) possibility of digital and analog hybrid style, (2) the potential to provide immediate feedback, and (3) the suitability for some learning objectives such as social skills.

This study is intended to design and develop DEERs based on Moodle and Zoom for teaching basic professionalism, with a focus on peer collaboration for medical students.

II. METHODS

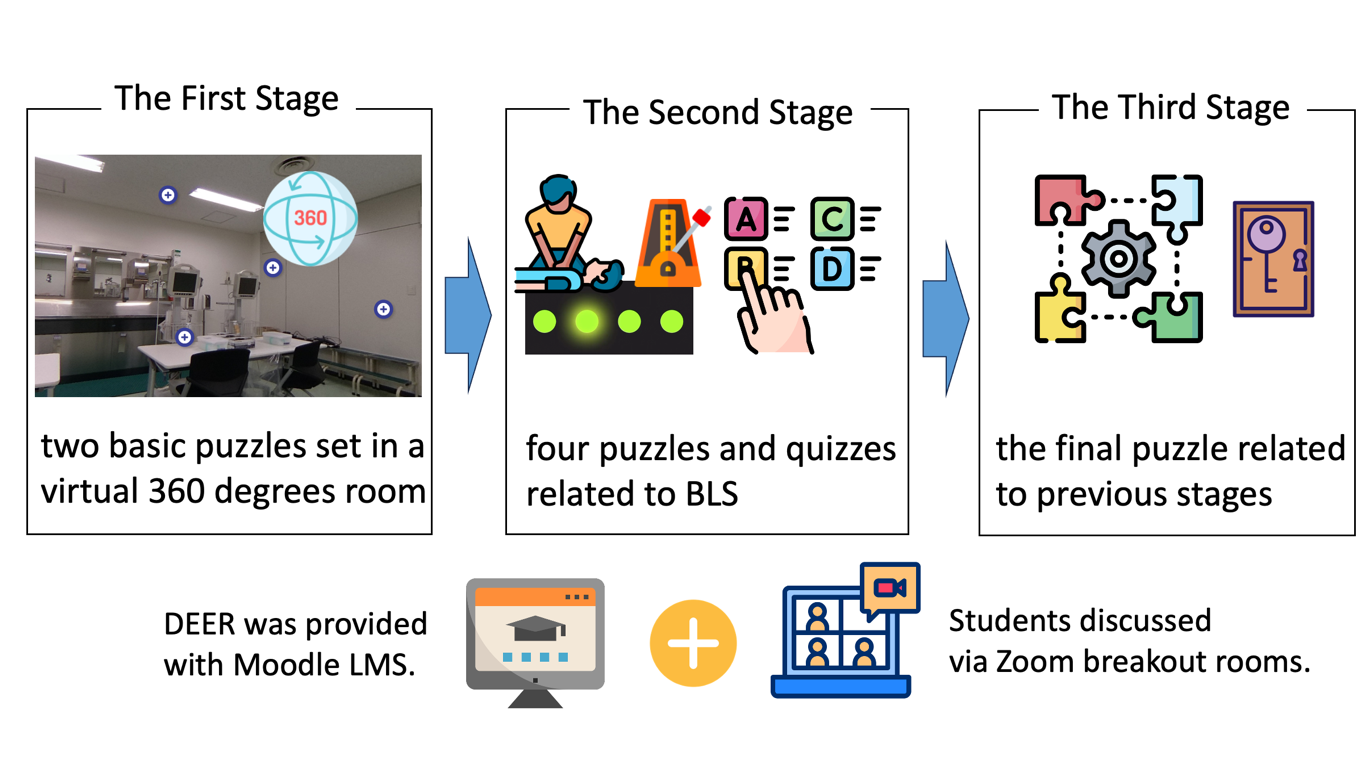

The authors made an online-based DEER with Moodle LMS and used it for teaching team communication and reviewing basic CPR knowledge for second-year undergraduate medical students. In this case, students solve asynchronous DEER challenges in Moodle through synchronous discussion in Zoom breakout rooms.

The learning objectives were to “learn collaboratively with peers” and to “understand concepts related to interpersonal relationships and interpersonal behaviour.” Before the class, students submitted a short report on the important elements that are required for team medicine, which they had learned as first-year students. The class was 100 minutes in length. The first 10 minutes were used for orientation. The next 60 minutes were used for DEERs. Within 60 minutes, a hint for solving DEERs was provided via Google Documents; authors added the hint as time went on. After the game, 30 minutes were used for reflection, including the explanation of the DEER answers and the basic lectures. Despite the existence of two aforementioned learning objectives, the time limits made it particularly hard to assess students’ achievement. Therefore, after the class, a report was assigned on the topic “points to keep in mind when sharing information and communicating with your team online through the game experience.”

There were three stages to the DEER. A total game design is shown in Figure 1. The first stage consisted of a 360o virtual room. Students had to explore the virtual room and solve two riddles. In this stage, some hints were hidden on the ceiling or the floor. Students had to find them by looking around the room. After solving the riddles, students inputted the answer to Moodle. If the answer was wrong, they had to wait one minute before inputting another answer. The second stage began after the two riddles. This stage had four puzzles related to CPR, such as concerning the placement of AED or metronome tempo of chest compression. Since the students learned about CPR when they were first-year students, these four puzzles were reviewed their understanding. The third stage was after the four CPR puzzles. In the third stage, students had to gather all the clues to clear the game.

Figure 1. A total game design

Program evaluation was based on students’ achievement results from the Moodle log and their comments from the questionnaires.

III. RESULTS

There were 29 groups, and each one had three to four students. While five groups were able to solve the riddle completely, one group could not even reach stage two. Moodle log data and questionnaires suggested that the difficulty of the riddles was appropriate, since only 8% of participants answered that the first stage was difficult, and other groups used about 15 minutes for the first stage from the logs.

In some groups, students turned off their cameras and solved the riddles individually. In this case, they shared almost nothing but the answers, and very little about the process for solving puzzles and riddles. In other groups, students turned on their cameras and shared the screen. In contrast to the previous groups, they solved the puzzles and riddles through live discussions.

IV. DISCUSSION

Some groups could not complete the DEERs, and one group could not reach stage two. In the group that could not finish stage one, students did not share the process of solving riddles. Moreover, they turned off their cameras, which made it difficult to define how they were approaching the tasks. The communication style of students potentially affects their achievement level. It is also connected to their learning objectives.

Despite the difficulty of teaching skills and attitude only with asynchronous distance learning, some scope exists for interactive content, for example, by having the students choose the correct tempo for chest compressions by sound with live discussion and feedback from others. Of course, it will be more effective to use face-to-face simulations to check psychomotor skills.