Abstracts of the Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC) 2026

Published online: 9 January, TAPS 2026, 11(Suppl.1)

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2026-11-Suppl.1

This supplementary issue of The Asia Pacific Scholar presents the abstracts accepted for the Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC) 2026. APMEC 2026 serves as a platform for meaningful dialogue, collaboration, and the co-creation of strategies that will help us navigate the evolving challenges of healthcare education.

The theme for this conference is “Harmony in Diversity Through Collaboration in Health Professions Education – Trends ● Issues ● Priorities ● Strategies”. In an increasingly complex and interconnected world, this theme underscores the vital role of embracing diverse socio-cultural backgrounds, disciplinary expertise, and lived experiences in health professions education. By integrating varied perspectives, we enrich learning, strengthen teamwork, and foster professional growth all of which ultimately enhance patient care and contribute to better global health outcomes.

Click “Download PDF” to view or download the list of abstracts.

Submitted: 24 September 2024

Accepted: 3 June 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 81-83

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/II3527

Nathasha Luke, Shing Chuan Hooi & Celestial T. Yap

Department of Physiology, Yong Loo Ling School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Lifelong learning is an essential skill for a successful medical practitioner to keep pace with rapidly advancing medical knowledge and technologies. Artificial intelligence(AI) has a potential in developing and promoting the skill of lifelong learning among medical undergraduates. AI can facilitate adaptive learning, collaborative learning, coaching, and incorporating evidence-based learning in undergraduate education as measures promoting lifelong learning. Users should be aware of the capabilities and limitations of the technology to promote effective incorporation in education. Medical undergraduates should receive a basic AI education to harness its’ potential in the best possible ways in lifelong learning.

Modern-day medical practice is rapidly revolutionising. The increasing content and complexity of medical knowledge are often beyond the human capacity to process and synthesise. A study in 2019 revealed there was an overall 2620% increase in the number of knowledge syntheses published over 20 years, from 1999 to 2019 (Maggio et al., 2020). Medical students and doctors struggle to stay updated with the expanding knowledge and find it difficult to cope with information overload. A successful practitioner should have excellent foundational knowledge, be up-to-date, know when and where to seek additional information, and understand optimal practices in the work environment. Such practitioners will adopt technologies to make their lifelong learning more effective and targeted toward improving patient care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is at exponential growth, particularly in the field of medicine. AI inventions span across multiple dimensions such as AI-aided diagnostic systems, image interpretation, medical records, patient communication, and community-based care. Future practice environments are likely to be heavily AI-integrated. AI-based knowledge management systems and search engines will streamline the process of practitioners keeping themselves up to date with evolving medicine.

Developing lifelong learning among students is an important domain of medical education, that will them to keep abreast of rapid advances in medicine. Medical schools foster the development of lifelong learning habits through strategies such as (1) adaptive learning (2) collaborative learning (3) coaching and (4) incorporating evidence-based learning into the curriculum. This article focuses on how AI could be harnessed to facilitate and enhance these strategies to inculcate lifelong learning among medical undergraduates.

II. HOW COULD AI ENHANCE THE PROCESS OF ADAPTIVE LEARNING?

Adaptive learning is a process that customises individual learning experiences by determining an individual’s strengths and weaknesses and specifically addressing them. The concept of adaptive learning has become popular in recent years. However, this concept was originally highlighted more than a century ago. In 1912, Edward Thorndike introduced the idea of the learning machine, where the machine could ask questions from the learner and suggest areas that need improvement. With the rise of Generative AI, this concept is coming to reality. Generative AI, which produced content like text, videos and music in response to user prompts, powers adaptive learning tools that assess student knowledge, offer personalised feedback, and pinpoint areas for improvement to help guide their learning process toward mastery (Luke & Hooi, 2024).

Rapid advancements in generative AI have made this technology accessible to many users, allowing learning institutions to customise adaptive AI platforms at a relatively lower cost. Such tools may not only facilitate the learning journey of medical students but also make them strive for continuous feedback-driven improvement as practitioners. In the future, AI-driven adaptive learning may revolutionise continuous professional development (CPD) to pinpoint and address learning gaps, allowing efficient and relevant learning for busy clinicians.

III. WILL AI-DRIVEN LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS PROMOTE COLLABORATION?

Collaboration is defined as the mutual engagement of participants in a coordinated effort to solve the problem together (Roschelle & Teasley, 1995). Collaborative learning by means of peer learning, interdisciplinary learning, and interprofessional learning should be promoted to ensure students develop the skills and confidence to collaborate as clinicians in the future. In clinical environments, doctors learn from each other in both formal and informal ways. This type of learning is particularly important in learning new skills and encourages self-learning behaviours in individuals. In medical school, collaborative learning skills are enhanced through group work, simulations, and collaborative activities among students from different related streams such as medicine, nursing, and pharmacy. These approaches strengthen interprofessional communication, knowledge sharing, and enhance learning.

AI-based virtual reality simulated clinical environments are adopted by multiple medical schools to promote experiential learning. Promoting collaboration should be incorporated as a learning outcome when possible into such simulations. For example, simulations can focus on students’ decision-making skills as what team members are to be activated in a simulated encounter and developing communication skills for effective collaboration. In addition, in the future, AI-based platforms may allow more widespread collaboration crossing boundaries, such as enabling clinicians to find the ‘expert’ to seek opinions on a particular condition, where AI-based systems can facilitate collaboration.

IV. COACHING FOR LIFE-LONG LEARNING – CAN AI DO THIS?

Coaching is a development process that enables a person to identify and enhance their own capabilities to reach personal and professional goals. This process has been demonstrated to be beneficial for students in educational settings (Breslin et al., 2023). How does coaching promote lifelong learning? Coaching, which allows the person to learn about self, enables one to identify own impediments towards learning. This will enhance behaviours facilitating learning. AI coaching or virtual coaching is now being explored. The advantages of AI coaching are accessibility, lack of bias, and convenience. Human coaching is still believed to be superior due to the aspects of the ability to express empathy, pick up non-verbal cues during conversation, and be more adaptive. Though the current technology of AI is unable to surpass an experienced human coach (Terblanche et al., 2022), these hurdles may be overcome with future advancements of the technology.

V. EMPHASISE EVIDENCE-BASED APPROACHES WITHIN THE CURRICULUM

Reading journals, critically appraising relevant publications, and adopting them in one’s own practice are essential elements of the lifelong learning process for doctors, which should be developed from undergraduate days themselves. The main hurdle for such incorporations is the tight schedule within the curriculum and the content load. Despite traditional teaching being replaced by integrated teaching, the content load covered within the curriculum remains substantial. The depth and breadth of the content taught in medical school have not proportionately evolved over the years, despite major changes happening in clinical environments with AI integration. AI acts as an instant source of knowledge, aiding clinical decision-making and patient care. Bearing this in mind, educators should revise their curricula to reduce the depth of certain elements that could be easily retrieved digitally. However, students should have a sound knowledge on foundational principles on which advanced concepts can build on.

Re-evaluating the curriculum to reduce the content load would free more time in the schedule to promote critical appraisal of scientific literature, enabling students to wisely use scientific literature to stay up to date. A thoughtful and pragmatic approach to curriculum revaluation for lifelong learning involves embedding core competencies such as critical thinking, adaptability, self-directed learning, and interdisciplinary collaboration instead of overloading content.

VI. EQUIP UNDERGRADUATES WITH BASIC AI KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS

Some medical schools, including NUS Medicine, have incorporated AI into the curricula. Exposing medical undergraduates to the foundations of AI technology can help them foresee the revolutionisation of future practice and equip themselves to embrace the technology. In addition, this will enable them to pursue new career pathways combining AI and Medicine. With regards to lifelong learning, clinicians may be equipped with AI-based tools to learn from real-time patient data for clinical decision-making, rather than waiting for prospective clinical trials or research. For example, students with foundational knowledge of AI will be able to use AI analytical skills to draw conclusions based on real-time and latest clinical data, as well as to detect trends of emerging diseases and antibiotic resistance, promoting early intervention.

Equipping future generations with AI knowledge will improve the quality of care and reduce diagnostic errors. Also, AI knowledge will guide practitioners to remain vigilant about data privacy and algorithmic bias when using AI. A future-ready curriculum will not only prepare students to use AI responsibly but also to question and enhance the tools.

AI comes with challenges and opportunities. The risk of bias, data quality and security issues, risk of over-reliance, AI relying on historical rather than real-time data, and lack of transparency in decision-making processes are some of the limitations. Still, AI has a vast potential to augment healthcare and health professions’ education as discussed above. AI should augment clinical decision making, and not replace. Ethical considerations, including patient consent, data security, and accountability, must remain central to any AI integration in healthcare practice.

In summary, AI has huge potential to enhance the strategies implemented in medical education to promote lifelong learning in medical undergraduates. The users should be aware of the limitations of the technology, and incorporate it cautiously to harness the maximum benefit of the technology in the process of transforming our undergraduates to better clinicians and lifelong learners.

Notes on Contributors

NL conceptualised the article, created the first draft, and revised subsequent versions. In addition, approved the final version of the article for submission.

HSC conceptualised the article, revised the draft versions, and approved the final version of the article for submission.

CTY conceptualised the article, revised the draft versions, and approved the final version of the article for submission.

Funding

We did not receive any funding for this publication.

Declaration of Interest

We do not have any conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional, or other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Luke, W. N. V., & Hooi, S. C. (2024). The role of artificial intelligence in knowledge management for medical students and doctors. Medical Teacher, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2024.2336065

Maggio, L. A., Costello, J. A., Norton, C., Driessen, E. W., & Artino, A. R., Jr. (2020). Knowledge syntheses in medical education: A bibliometric analysis. Perspectives on Medical Education, 10(2), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-020-00626-9

Roschelle, J., & Teasley, S. D. (1995). The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving (pp. 69–97). Springer eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-85098-1_5

Terblanche, N., Molyn, J., De Haan, E., & Nilsson, V. O. (2022). Comparing artificial intelligence and human coaching goal attainment efficacy. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0270255. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270255

*Nathasha Luke

2 Medical Drive, MD 9,

National University of Singapore, 117593

+6596204104, +6566013506

Email: nathasha@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 6 February 2025

Accepted: 14 May 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 94-96

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/II3664

Charlene Tan1 & Ruth Neo2

1College of Arts, Humanities and Languages, Life University, Cambodia; 2UNSW Medicine & Health, University of New South Wales, Australia

I. INTRODUCTION

This article proposes a Chinese philosophical approach to well-being for medical education by drawing on the thought of Mencius (372-289 B.C.E.). As it is not possible to cover all areas of Mencius’ philosophy within this short essay, our focus is on Mencius’ idea of interpersonal joy, as recorded in the classic Mengzi. This paper shall explain how interpersonal joy, from a Mencian perspective, centres on the shared delight from benefiting others while cultivating personal virtue.

II. MENCIUS ON WELL-BEING AND INTERPERSONAL JOY

Well-being is used synonymously or in conjunction with related terms such as welfare, happiness, prudential value, the good life, prudential good life, quality of life, flourishing, self-interest, fulfilment, utility and pastoral care (Fletcher, 2016). Mencius’ approach to well-being is encapsulated in his idea of interpersonal joy, which harmonises personal and communal delight. A representative passage is 7A20.1 in the Mengzi:

Mengzi said, “An exemplary person [Junzi] takes joy in three things, and being King of the world is not one of them. The person’s first joy is that one’s parents are both alive and one’s siblings have no difficulties. The second joy is that looking up one is not disgraced before Heaven, and looking down on one is not ashamed before humans. The third joy is getting assistance and cultivating the brave and talented people of the world. An exemplary person takes joy in three things, and being King of the world is not one of them (Van Norden, 2008, p. 176).

This passage is about a Junzi which literally means ‘son of a noble’. Confucius appropriated this historical term and infused it with moral import, thereby changing its meaning to denote an exemplary person. That the exemplary person embodies Confucian well-being is evidenced by passages in the Mengzi that describe such a person as having “no anxieties” (4B28.7) and experiencing “joy” (7A20.1, 7A21.2).

With respect to 7A20.1, the passage begins by stating that an exemplary person does not derive joy from being King of the world. Mencius is not asserting that holding political power is wrong or detrimental to one’s well-being. On the contrary, he acknowledges in the next passage that an exemplary person, like all rulers, “desires a large territory and numerous people” (7A21.1). Mencius’ point is that Kingship, in itself, does not give satisfaction to an exemplary person; instead, such a person “takes joy in taking one’s place in the middle of the world and making all the people within the Four Seas settled” (7A21.1) (Van Norden, 2008, p. 176). We see here how an exemplary person obtains personal joy by bringing joy to others (“making all the people within the Four Seas settled”).

All people can become exemplary people by developing the four sprouts within them, namely the mind-and-heart of compassion, the shame of evil in oneself and hatred of evil in others, humility and deference, and right and wrong (2A.6). These four sprouts, when consistently cultivated, will grow into the virtues of benevolence, propriety, righteousness and wisdom, all of which contribute to interpersonal joy. Retuning to 7A20.1, Mencius’ message is that an exemplary person does not obtain pleasures and life satisfaction from prudential desires, which are manifested in egoistic ambitions with little regard for others. Instead, joy is felt when a person immerses oneself in social interactions and builds strong connections with others. An exemplary person also derives delight by treating others well and developing their potential for the common good. The end result is “making all the people within the Four Seas settled” (7A21.1) (Van Norden, 2008, p. 176).

To sum up, Mencian well-being is indicated by interpersonal joy which integrates individual and collective happiness, as demonstrated by the exemplary person. Communal joy engenders collective well-being, illustrated by the King “sharing the same delight as the people” (1B1.4) (Van Norden, 2008, p. 16).

III. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MEDICAL EDUCATION

A major implication of Mencian well-being is for medical schools to promote interpersonal joy in the curriculum and assessment. Two suggestions are elaborated in this section: a shift from summative assessment and competition to formative assessment and collaboration; and the introduction of a wellness curriculum that pivots on interpersonal joy.

First, medical schools need to review their curriculum and assessment so as to remove any hindrances to the realisation of interpersonal joy in their students. A specific recommendation is to replace summative assessment and competition with formative assessment and collaboration. Mencius’ call for collective well-being is difficult to achieve if students are fixated with outperforming one another due to the pressures of high-stakes exams. Kachel et al. (2020) report that “during medical school interpersonal skills linked to being an active member of an institution are underrepresented in curricula” (p. 11). It is a challenge for medical students to care for the well-being of others and be open about their mental health needs if they are circumscribed by a culture of competition, distrust and judgement (Canadian Federation of Medical Students, 2021). Cooperation and interdependence can be enhanced by reducing or removing pen-and-paper examination and norm-referenced assessments, and introducing (more) collaborative projects and criterion-referenced assessments. The assessment mode for the cultivation of interpersonal joy should be formative, where students are given continuous feedback and find enjoyment in learning and sharing.

A pedagogical approach to foster interpersonal joy is group projects, where students collaborate for shared success. Anchored upon the principles of cooperation and harmony, group projects foreground interpersonal joy and competencies that are underrepresented in the curricula (Kachel et al., 2020). Termly group projects nurture communication and teamwork skills, spanning a wide range of topics from the basic clinical sciences to medical ethics and public health. The group projects can be evaluated via negotiated assignment, where students develop their own research questions and set their own assessment criteria that are aligned with the course themes. The goal is to foster student-driven learning that gives students the opportunity to explore common topics of interest beyond the confines of standard, end-of-course examinations. A related pedagogical approach is encouraging students to participate in service learning, community involvement as well as local and overseas volunteer projects, so as to generate communal interactions and bonding. By serving others, the students’ sprout of compassion is cultivated and manifested through empathy, beneficence and concern for others (Van Norden, 2008).

The second recommendation is for medical schools to enact a wellness curriculum that pivots on interpersonal joy. Medical schools could adapt the wellness curriculum for medical students in a Canadian university; students there were asked to “define their core values and beliefs while respecting those of others, and apply them in the context of their developing physician identity and that of the medical profession” (Canadian Federation of Medical Students, 2021, p. 22). Mencian ideas can be integrated into the before-mentioned wellness curriculum through reflective questions such as: What does an exemplary person (junzi) mean to me? How can Mencian interpersonal joy be part of my core values as a medical professional? How can I obtain interpersonal joy through interacting with and serving others? The self-reflection activity can be undertaken in various formats such as group discussions, journalling and multi-media presentations.

Mencian ideas of well-being and related suggestions may face challenges in medical schools where individualism and competition are often culturally entrenched. In this regard, Mencian well-being may be more appropriate for medical education in Confucian heritage cultures. Significantly, studies have shown that Asian adolescents experience a strong sense of well-being when they partake in collective activities; in contrast, adolescents in Anglo-American societies typically enjoy higher well-being when they engage in more individualistic activities (Chue, 2023). Relatedly, Mencian well-being’s focus on moral cultivation sets it apart from two dominant models in Anglophone societies, namely Seligman’s PERMA (Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning & Accomplishment) and Ryff’s six aspects of psychological well-being, which are autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. As noted earlier, Mencius advocates for the development of our innate goodness in the form of the four sprouts, which in turn contributes to interpersonal joy. In contrast, the theories of Seligman and Ryff generally de-emphasise moral education.

In individualistic societies, interpersonal joy can complement the existing wellness frameworks by underscoring collaborative learning, such as group projects and service learning (Bourcier et al., 2021). Staff development is also critical, where faculty members are introduced to Mencian principles and practical ways to promote them, such as organising service learning and designing wellness curricula. Ultimately, the successful implementation of interpersonal joy necessitates faculty development, which should be strategically incorporated into the staff training programmes (Canadian Federation of Medical Students, 2021).

IV. CONCLUSION

Mencius’ approach to well-being is encapsulated in his idea of interpersonal joy, which harmonises personal and communal delight. Mencian well-being supports collective well-being by twinning self-interests and other interests. This paper has also suggested that medical schools revamp the curriculum and assessment modes to shift from summative assessment and competition to formative assessment and collaboration. Medical schools should also explore pedagogical methods that incorporate Mencian idea of interpersonal joy into the curriculum.

Notes on Contributors

Charlene Tan conceptualised the topic, provided philosophical ideas and drafted the manuscript. Ruth Neo gave inputs that pertained to medical student well-being and co-drafted the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval is not relevant as this is a conceptual paper that does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions to earlier drafts.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organisation for the submitted work.

Declaration of Interest

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

Canadian Federation of Medical Students. (2021). Canadian federation of medical students wellness curriculum framework. https://www.cfms.org/files/wellness-resources/CFMS-Wellness-Curriculum-Framework_FINAL.pdf

Chue, K. L. (2023). Cultural issues in measuring flourishing of adolescents. In R. B. King, I. S. Caleon, & A. B. I. Bernardo (Eds.), Positive psychology and positive education in Asia: Understanding and fostering well-being in schools (pp. 329-342). Springer.

Fletcher, G. (Ed.). (2016). The Routledge handbook of philosophy of well-being. Routledge.

Kachel, T., Huber, A., Strecker, C., Höge, T., & Höfer, S. (2020). Development of cynicism in medical students: Exploring the role of signature character strengths and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(328), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00328

Van Norden, B. W. (2008). Mengzi. With selections from traditional commentaries. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

*Charlene Tan

Life University, Phreah Sihanouk,

Sihanoukville, Cambodia

Email: chptan@u.nus.edu

Submitted: 18 November 2024

Accepted: 14 May 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 5-25

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/RA3572

Matthew Jian Wen Low1, Han Ting Jillian Yeo2, Dujeepa D. Samarasekera2, Gene Wai Han Chan1 & Lee Shuh Shing2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 2Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Effective and actionable instructional design features improve return on investment in Technology enhanced simulation (TES). Previous reviews on instructional design features for TES that improve clinical outcomes covered studies up to 2011, but updated, consolidated guidance has been lacking since then. This review aims to provide such updated guidance to inform educators and researchers.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted on instructional design features in TES in medical education. Original research articles published between 2011 to 2022 that examined outcomes at Kirkpatrick level three and above were included.

Results: A total of 30,491 citations were identified. After screening, 31 articles were included in this review. Most instructional design features had a limited evidence base with only one to four studies each, except 11 studies for simulator modality. Improved outcomes were observed with error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training. Mixed results were seen with different simulation modalities, isolated components of mastery learning, just-in-time training, and part versus whole task practice.

Conclusion: There is limited evidence for instructional design features in TES that improve clinical outcomes. Within these limits, error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training appear beneficial. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness and generalisability of these features.

Keywords: Simulation, Instructional Design, Clinical Outcomes, Review

Practice Highlights

- This review pinpoints additional beneficial instructional design features emerging since 2011.

- These include error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training.

- Further evidence from diverse task and learner contexts is needed to establish generalisability.

- Current evidence continues to suggest no clear superiority of one simulator modality over the other.

I. INTRODUCTION

Technology enhanced simulation (TES) training has been shown to be effective for skills, behaviour, and patient-related outcomes (Cook et al., 2011; McGaghie et al., 2011). Instructional design features in simulation refer to variations in aspects of simulation design that act as active ingredients or mechanisms that make simulation effective, with examples including distributed practice, mastery learning, and range of difficulty (Cook, Hamstra, et al., 2013). Effective instructional design features for TES are actionable for educators because they offer specific, implementable guidance, and an area of research interest (Issenberg et al., 2005; Nestel et al., 2011; Schaefer et al., 2011), including those that lead to transfer to authentic clinical practice (Frerejean et al., 2023; Zendejas et al., 2013).

While it is acknowledged that conducting a study to establish a causal relationship between an educational intervention and subsequent patient and clinical process outcomes is challenging (Cook & West, 2013), such studies become particularly valuable when appropriately executed (Dauphinee, 2012). These studies represent the apex of impact in Kirkpatrick’s model for program evaluation (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006), holding the highest clinical significance and representing the ultimate goal of health professions education which is to enhance patient outcomes by equipping the healthcare workforce to effectively address societal needs (Carraccio et al., 2016). Additionally, the examination of clinical outcomes, when coupled with a consideration of costs, contributes to the informed allocation of limited institutional resources to such educational approaches (Lin et al., 2018).

In prior reviews of TES including studies up to 2011, the vast majority of studies examined outcomes at the levels of reaction and learning demonstrated in written or simulation tests, with only a small body of evidence studying outcomes in workplace contexts (Cook, Hamstra, et al., 2013; Nestel et al., 2011; Zendejas et al., 2013) suggesting that clinical variation, multiple learning strategies, and increased time learning are beneficial variations. This limited evidence base for transfer to workplace contexts hinders educators in fully harnessing the potential of TES to improve patient and system outcomes and obtain the best returns on investments in simulation technology. Given the time interval since these prior reviews, further evidence would have accrued regarding these and other instructional design features.

Given the time elapsed since the last comprehensive review of TES instructional design features, the scarcity of prior studies on clinical outcomes, and the importance of these outcomes, we conducted this narrative review. The objective was to provide an updated understanding of the instructional design features in TES that are associated with enhanced clinical outcomes, thereby addressing a significant gap in the existing literature, to guide educators seeking to optimise instructional design, and provide researchers with an overview of the current state of this literature and guide further inquiry.

II. METHODS

We conducted a narrative review based on the framework proposed by Ferrari (2015). We searched MEDLINE, ERIC, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science databases for articles published from 2012 January 01 to 2022 December 06. We translated abstracts and articles not in English into English using Google Translate.

The following search terms were used: (Medical education) AND (Simulation OR Cadaver OR Simulator OR Augmented Reality OR Virtual reality OR Mixed reality).

Studies were included if they were original research articles examining instructional design variations in TES with at least one outcome at Kirkpatrick levels three or above, as described and utilised by the Best Evidence Medical Education Collaboration (Steinert et al., 2006). We included a broad range of TES modalities, such as computer based virtual reality simulators, high fidelity and static mannequins, plastic models, live animals, inert animal products, and human cadavers as stipulated in the review by Cook et al. (2011). We included augmented reality and mixed reality as they satisfied the prior definition of “materials and devices created or adapted to solve practical problems” in simulation established by Cook et al (2011). Studies where TES was utilised together with human patient actors were included. We included studies with observational, experimental, and qualitative designs.

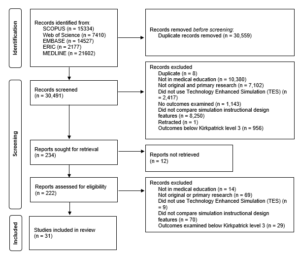

Studies were excluded if they involved only human patient actors as the sole modality of simulation, used simulation outside of health professions education, used simulation for noneducation purposes such as procedural planning or patient education, or only compared simulation with no simulation. We excluded studies involving only nurses given that there are recent and ongoing reviews addressing a similar research question (El Hussein & Cuncannon, 2022; Jackson et al., 2022), but included interprofessional studies. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review and selection process.

Three researchers (MJWL, SSL, JHTY) independently read the full text of articles that met the inclusion criteria and extracted study information including geographical origin, specialty context, type of skill studied, level of the learner, simulation modalities used, instructional design variations studied, and outcomes categorised into the highest Kirkpatrick level studied. Any differences were resolved by a discussion among researchers to arrive at a consensus.

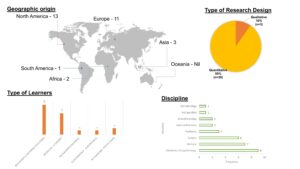

III. RESULTS

A total of 30,491 records were identified using the search strategy. From these, 31 eligible studies were identified and reviewed (Figure 1 and Table 1). Figure 2 summarises basic information on these studies. The number of studies from each geographic region were 13 from North America (42%), 11 from Europe (35%), three from Asia (10%), two from Africa (6%), and one from South America (3%). One study did not clearly state the countries involved.

28 out of 31 (90%) of the studies adopted a quantitative research design focusing on experimental design. Most simulation interventions were conducted among residents/fellows/interns, followed by medical students.

The results reported in the studies are divided into two groups:

- Evidence suggests improved outcomes

- Evidence shows mixed results

A. Improved Outcomes

Error management training was associated with improved obstetric ultrasound skills compared to error avoidance training in novices (Dyre et al., 2017). Frequent brief on-site simulation, at 40 minutes a month and three minutes a week, was associated with reduced infant mortality compared to a single day course (Mduma et al., 2015). Integrating non-technical skills (NTS) training into a colonoscopy skills curriculum with TES, without increasing time spent teaching, improved observed performance during colonoscopies on real patients, although it was unclear whether this was driven by changes in observed NTS only, or both NTS and technical skills (Walsh et al., 2020).

One qualitative study found that in situ training had greater organisational impact and provided more information for practical organisational changes (Sørensen et al., 2015). One qualitative study found that multi-professional training led to improved communication, leadership, and clinical management of post-partum haemorrhage (Egenberg et al., 2017).

1. Dyad Training

In one study of obstetric ultrasound skills (Tolsgaard et al., 2015) a larger proportion of the dyad training group (71%) scored above the criterion referenced pass fail level than the individual training group (30%) on the objective structured assessment of ultrasound skills, though the difference in mean scores on did not reach statistical significance. Other benefits included increased efficiency from greater faculty to learner ratios.

2. Complex Bundles

Three studies found improvements with complex bundles comprising multiple instructional design variations.

Medical students performed the correct sequence of steps for endotracheal intubation measured by a checklist more often when practice with a mannequin was augmented by a 10-question pre-test, hand held tablets containing scenarios, checklists, and learning algorithms, 24-hour access to the simulation laboratory, and remote review of practice recordings with feedback from teachers via email (Mankute et al., 2022).

Residents had improved observed performance in laparoscopic salpingectomy with lectures, videos, reading materials, a box trainer with pre-set proficiency benchmarks, a VR simulator for technical skills, and non-technical skills training with scripted confederates, compared to a conventional curriculum including simulation with minimal further description (Shore et al., 2016).

In one qualitative study of obstetric residents, there was improved transfer of communication and team work skills and situational awareness with simulation aligned to multiple principles including authenticity, psychological fidelity, engineering fidelity, Paivio’s dual coding, feedback, variability, and increasing complexity (de Melo et al., 2018).

B. Mixed Results

1. Simulation Modality

Eleven studies examined whether outcomes differed when different simulation modalities were used. Examples include higher versus lower technological complexity in a physical simulator (DeStephano et al., 2015; Sharara-Chami et al., 2014), cadaveric versus synthetic models (Lal et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2018; Tchorz et al., 2015), virtual reality (VR) versus physical simulators (Daly et al., 2013; Gomez et al., 2015; Orzech et al., 2012; O’Sullivan et al., 2014), and a computer based versus physical simulated operating room for student orientation (Patel et al., 2012).

Overall, there no clear pattern of superiority of a particular type of simulator. Most studies found no difference, with three exceptions: Gomez et al (2012) found that VR alone, and VR with physical simulator, led to superior performance in observed colonoscopic skills in real patients, compared to physical simulator alone; Chunharas et al (2013) found that adding practice on fellow students on top of mannequin practice improved observed performance in subcutaneous and intramuscular injection skills; Patel et al (2012) found that using a physical simulated operating room was superior to an online computer based operating room for training novice medical students in appropriate behaviour in the operating room.

To view Table 1 click here.

Abbreviations. ACS/APDS: American College of Surgeons / Association of Program Directors in Surgery; EAT: Error avoidance training; EMT: Error management training; GAGES-C: Global Assessment of Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Skills-Colonoscopy; GOALS: Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills; ISS: In situ simulation; JAG DOPS: Joint Advisory Group Direct Observation of Procedural Skills; JIT: Just in time; OSA-LS: objective structured assessment of laparoscopic salpingectomy; NTS: Non-technical skills. OSAUS: objective structured assessment of ultrasound; OSS: Off-site simulation; PGY: Post graduate year; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; VR: Virtual reality.

Kirkpatrick levels. 1: Reaction e.g. participants’ views on learning experience; 2a: Learning – Change in attitudes; 2b: Learning – Modification of knowledge or skills; 3: Behaviour – Change in behaviours; 4a: Results – Change in the system/organisational practice; 4b: Results – Change in patient outcomes.

Table 1. List of included studies and skills, instructional design variations and outcomes examined

Figure 1. Flow of studies through identification process

Figure 2. Summary of geographical origin, type of research, type of learners and disciplines studied

2. Components of Mastery Learning

Four studies examined components of mastery learning, such as progressive task difficulty and proficiency-based progression. Progressive task difficulty for TES was associated with improved rater observed colonoscopic performance on real patients (Grover et al., 2017), while the evidence was mixed for proficiency-based progression for TES, with studies finding reduced epidural failure rates (Srinivasan et al., 2018) and fewer adverse events in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (De Win et al., 2016), while another found no difference in operative performance for bowel anastomosis in real patients (Naples et al., 2022).

3. Part Versus Whole Task

Two studies compared part versus whole task training. Both found no difference, in rater observed performance in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (Hernández-Irizarry et al., 2016), and intraoperative camera navigation skills (Nilsson et al., 2017), though randomised part task training led to faster skills mastery with greater cost effectiveness compared to whole task training.

4. Increased Time Spent in Simulation Training

Two studies examined amount of time spent in simulation training. One study showed reduced incidence of malpractice claims (Schaffer et al., 2021), while another study found no difference in successful deep biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (Liao et al., 2013).

5. Just in Time (JIT) Training

Overall, there was mostly no benefit seen with JIT training with TES, across three studies. One study examined the addition of JIT video after prior TES (Todsen et al., 2013), and one study compared JIT practice alone, JIT practice with feedback from this practice, and feedback alone derived from baseline testing (Kroft et al., 2017). JIT and just-in-place physical simulator training did not improve first pass lumbar puncture success, but improved mean number of attempts and process measures such as early stylet removal (Kessler et al., 2015).

IV. DISCUSSION

We sought to provide an updated synthesis on effective instructional design features in simulation in medical education, focusing on those that produce higher level outcomes at Kirkpatrick levels three and above. A prior review searching until 2011 identified only 18 studies that examined outcomes at Kirkpatrick level three and above, out of their pool of 10,297 studies. Our review reveals a notable rise in the number of studies over the past ten years, exploring instructional design and clinical outcomes. In the discussion that follows, we synthesise the findings with existing literature and theory to extract valuable insights for medical educators.

A. Implications for Current Practice

This review underscores the necessity of directing resources towards effective instructional design features, emphasising that these need not be strictly tied to specific simulator types, as advocated by Norman. Despite the ongoing evolution and incorporation of an expanding array of TES modalities, including Virtual Reality (VR) in this review, we observed mixed results concerning simulation modality as an instructional design variation. Upon closer examination of interventions outlined in studies comparing simulation modalities, it becomes evident that confounding factors may arise due to variations in the application of training to proficiency criteria (a characteristic of mastery learning) or differences in the quality of measurement.

In the study conducted by Gomez et al (2015), training to proficiency criteria was incorporated in study arms demonstrating benefit (VR and VR plus physical simulator) and not incorporated in the remaining arm (physical simulator alone). Similarly, in the study by Orzech et al (2012) where training until proficiency criteria were reached was a shared feature of both arms, no significant difference between groups was observed. It remains unclear whether observed differences were attributable to the application of training until proficiency criteria were met or to the varied simulation modalities.

Chunharas et al (2013) and Patel et al (2012) also noted outcome differences when comparing different simulation modalities. However, the robustness of these findings is constrained using a checklist observation scale developed for individual studies with minimal validity evidence. Clinical and task variations, recognised as beneficial in prior reviews (Zendejas et al., 2013), may elucidate the advantages identified by Chunharas et al and the VR plus physical simulator arm in the study by Gomez et al.

Components of mastery learning appear mostly effective, although isolated implementation of a component without the whole may erode effectiveness. The inconsistent evidence for effectiveness of components of mastery learning in this review is surprising, given prior evidence for the effectiveness of mastery learning for translational outcomes (Griswold-Theodorson et al., 2015). The difference may lie in piecemeal rather than holistic implementation of mastery learning as a complex intervention, with seven complementary components working together (McGaghie, 2015).

Another difference is that our review only included studies comparing different TES interventions, while the review by Griswold-Theodorson et al included studies that compared mastery learning with a wider range of comparators, including no TES. Notably, a separate systematic review and meta-analysis of mastery learning found only three studies from 1984-2010 comparing mastery learning to other TES interventions for patient outcomes, with no statistically significant benefit overall and substantial heterogeneity (Cook, Brydges, et al., 2013).

Methodological issues may be another contributory factor. Naples et al (2022) postulate in their study the reasons for the lack of observed difference, including a long duration between intervention and outcome assessment, which was longer in the intervention group than the control group, biasing towards the null, and surprisingly high baseline performance with an insufficiently sensitive rater observation tool. This study had only nine participants, limiting statistical power. These represent important methodological considerations for researchers designing educational intervention studies.

The effectiveness of increased time spent in simulation training is associated with incorporation of learning conversations. Discrepancies in outcomes between the two studies assessing the impact of time spent in simulation training may be attributed to the presence of debriefing in the study conducted by Schaffer et al (2021), as opposed to un-coached practice without feedback in the study by Liao et al (2013). It is crucial to note that the advantages derived from extended training periods are not solely attributed to prolonged duration but are also influenced by the integration of learning conversations. These conversations encompass both debriefing and feedback (Tavares et al., 2020), both of which have demonstrated efficacy, as supported by existing research (Cheng et al., 2014; Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

In a systematic review by Hatala and colleagues (Hatala et al., 2014), feedback emerged as moderately effective for procedural skills simulation training. Notably, feedback from multiple sources, including instructors, proved more effective than feedback from a single source.

Distributed practice is preferred over blocked practice for TES. Frequent brief simulation (Mduma et al., 2015) essentially describes distributed rather than blocked practice. The increased effectiveness seen with distributed practice here is consistent with existing literature within (Cecilio-Fernandes et al., 2023) and outside (Dunlosky et al., 2013) of health professions education.

Dyad training is notable for being efficient with similar or better outcomes, and is consistent with existing literature on motor skills learning (Wulf et al., 2010). The optimal group size has not been clearly determined, beyond single versus dyad, and would be a productive avenue of inquiry for evidence-based determination of learner to faculty ratios, accounting for contextual factors such as task complexity and stage of learner’s development.

In situ simulation may be beneficial in generating participant insights that feed into systems-based improvements through quality improvement mechanisms (Calhoun et al., 2024; Nickson et al., 2021). This combines multiple mechanisms by which TES can produce meaningful impact: through changing individual learner behaviour and changing systems processes.

Error management training appears beneficial for transfer outcomes in novices. This is congruent with literature outside of medical education (Keith & Frese, 2008). The limited evidence base within medical education makes this ripe for further study across task and learner types.

In summary, the features mentioned above are predominantly drawn from previous studies, primarily conducted at Kirkpatrick level two. This review contributes by offering an updated synthesis of evidence, outlining the extent to which this evidence can be extrapolated to higher Kirkpatrick levels, and highlighting features that were previously unexplored at clinical process and outcome levels. Collectively, evidence spanning these levels serves as a guide for those designing TES with the goal of achieving educational and clinical impact.

B. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Studies that examine Kirkpatrick levels three and above continue to constitute a relatively small fraction of the overall research landscape. Furthermore, this limited body of research is dispersed among various instructional design features, with only a small number of studies investigating each specific feature. Consequently, drawing definitive conclusions about effectiveness becomes challenging, representing a primary constraint of this review. Despite these limitations, we have tried to extract valuable insights for health professions educators by synthesising the findings with existing literature and theory.

The limited evidence bases for most individual instructional design features, especially those demonstrating benefits at Kirkpatrick levels three and four, limits the strength of conclusions that can be drawn about their effectiveness. Further studies replicating these results would strengthen the argument that a particular instructional design feature is able to achieve clinical impact. The evidence base is also limited in the variety of task and learner contexts studied for each individual instructional design feature. Determining the generalisability of these findings requires further research applying these features across diverse TES contexts with different skills and learner groups. Future research should also continue to explore novel and promising instructional design features, such as hybrid simulations where mannequins are overlayed with animal tissue or gel-based phantoms (Balakrishnan et al., 2025).

V. CONCLUSION

There is limited evidence for instructional design features in TES that translate to improved clinical outcomes. Within these limits, error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training appear beneficial. Given the limited evidence base for these individual features, definitive determination of effectiveness and generalisability requires further research applying promising target features across different task and learner contexts.

Notes on Contributors

Matthew Low is an emergency physician at National University Hospital, Singapore, and adjunct assistant professor at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Jillian Yeo is a medical educationalist at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Dujeepa Samarasekera is senior director at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Gene Chan is an emergency physician at National University Hospital, Singapore, and adjunct assistant professor at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Shuh Shing Lee is a medical educationalist at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Matthew Low, Jillian Yeo and Shuh Shing Lee conceived of the work, collected and analysed data, and drafted the work. Gene Chan and Dujeepa Samarasekera conceived of the work and reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. All contributors gave final approval of the version to be published and are agreeable to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not applicable as this is a review paper.

Funding

There was no funding for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

Balakrishnan, A., Law, L. S.-C., Areti, A., Burckett-St Laurent, D., Zuercher, R. O., Chin, K.-J., & Ramlogan, R. (2025). Educational outcomes of simulation-based training in regional anaesthesia: A scoping review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 134(2), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.07.037

Calhoun, A. W., Cook, D. A., Genova, G., Motamedi, S. M. K., Waseem, M., Carey, R., Hanson, A., Chan, J. C. K., Camacho, C., Harwayne-Gidansky, I., Walsh, B., White, M., Geis, G., Monachino, A. M., Maa, T., Posner, G., Li, D. L., & Lin, Y. (2024). Educational and patient care impacts of in situ simulation in healthcare: A systematic review. Simulation in Healthcare, 19(1S), S23–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000773

Carraccio, C., Englander, R., Van Melle, E., Ten Cate, O., Lockyer, J., Chan, M.-K., Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., & International Competency-Based Medical Education Collaborators. (2016). Advancing competency-based medical education: A charter for clinician-educators. Academic Medicine, 91(5), 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001048

Cecilio-Fernandes, D., Patel, R., & Sandars, J. (2023). Using insights from cognitive science for the teaching of clinical skills: AMEE Guide No. 155. Medical Teacher, 45(11), 1214–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2168528

Cheng, A., Eppich, W., Grant, V., Sherbino, J., Zendejas, B., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Debriefing for technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education, 48(7), 657–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12432

Chunharas, A., Hetrakul, P., Boonyobol, R., Udomkitti, T., Tassanapitikul, T., & Wattanasirichaigoon, D. (2013). Medical students themselves as surrogate patients increased satisfaction, confidence, and performance in practicing injection skill. Medical Teacher, 35(4), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.746453

Cook, D. A., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Hamstra, S. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Mastery learning for health professionals using technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1178–1186. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a365d

Cook, D. A., Hamstra, S. J., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-based education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Teacher, 35(1), e867-898. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.714886

Cook, D. A., Hatala, R., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hamstra, S. J. (2011). Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 306(9), 978–988. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1234

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2013). Perspective: Reconsidering the focus on “outcomes research” in medical education: A cautionary note. Academic Medicine, 88(2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78

Daly, M. K., Gonzalez, E., Siracuse-Lee, D., & Legutko, P. A. (2013). Efficacy of surgical simulator training versus traditional wet-lab training on operating room performance of ophthalmology residents during the capsulorhexis in cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 39(11), 1734–1741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.05.044

Dauphinee, W. D. (2012). Educators must consider patient outcomes when assessing the impact of clinical training. Medical Education, 46(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04144.x

de Melo, B. C. P., Rodrigues Falbo, A., Sorensen, J. L., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & van der Vleuten, C. (2018). Self-perceived long-term transfer of learning after postpartum haemorrhage simulation training. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 141(2), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12442

De Win, G., Van Bruwaene, S., Kulkarni, J., Van Calster, B., Aggarwal, R., Allen, C., Lissens, A., De Ridder, D., & Miserez, M. (2016). An evidence-based laparoscopic simulation curriculum shortens the clinical learning curve and reduces surgical adverse events. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 7, 357–370. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S102000

DeStephano, C. C., Chou, B., Patel, S., Slattery, R., & Hueppchen, N. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of birth simulation for medical students. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 213(1), 91.e1-91.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.024

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Dyre, L., Tabor, A., Ringsted, C., & Tolsgaard, M. G. (2017). Imperfect practice makes perfect: Error management training improves transfer of learning. Medical Education, 51(2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13208

Egenberg, S., Karlsen, B., Massay, D., Kimaro, H., & Bru, L. E. (2017). “No patient should die of PPH just for the lack of training!” Experiences from multi-professional simulation training on postpartum haemorrhage in northern Tanzania: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0957-5

El Hussein, M. T., & Cuncannon, A. (2022). Nursing students’ transfer of learning from simulated clinical experiences into clinical practice: A scoping review. Nurse Education Today, 116, 105449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105449

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Frerejean, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Condron, C., Strauch, U., & Eppich, W. (2023). Critical design choices in healthcare simulation education: A 4C/ID perspective on design that leads to transfer. Advances in Simulation (London, England), 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-023-00242-7

Gomez, P. P., Willis, R. E., & Van Sickle, K. (2015). Evaluation of two flexible colonoscopy simulators and transfer of skills into clinical practice. Journal of Surgical Education, 72(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.08.010

Griswold-Theodorson, S., Ponnuru, S., Dong, C., Szyld, D., Reed, T., & McGaghie, W. C. (2015). Beyond the simulation laboratory: A realist synthesis review of clinical outcomes of simulation-based mastery learning. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1553–1560. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000938

Grover, S. C., Scaffidi, M. A., Khan, R., Garg, A., Al-Mazroui, A., Alomani, T., Yu, J. J., Plener, I. S., Al-Awamy, M., Yong, E. L., Cino, M., Ravindran, N. C., Zasowski, M., Grantcharov, T. P., & Walsh, C. M. (2017). Progressive learning in endoscopy simulation training improves clinical performance: A blinded randomized trial. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 86(5), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1529

Hatala, R., Cook, D. A., Zendejas, B., Hamstra, S. J., & Brydges, R. (2014). Feedback for simulation-based procedural skills training: A meta-analysis and critical narrative synthesis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 19(2), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-013-9462-8

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hernández-Irizarry, R., Zendejas, B., Ali, S. M., & Farley, D. R. (2016). Optimizing training cost-effectiveness of simulation-based laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. American Journal of Surgery, 211(2), 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.027

Issenberg, S. B., McGaghie, W. C., Petrusa, E. R., Lee Gordon, D., & Scalese, R. J. (2005). Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher, 27(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046924

Jackson, M., McTier, L., Brooks, L. A., & Wynne, R. (2022). The impact of design elements on undergraduate nursing students’ educational outcomes in simulation education: Protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01926-3

Keith, N., & Frese, M. (2008). Effectiveness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.59

Kessler, D., Pusic, M., Chang, T. P., Fein, D. M., Grossman, D., Mehta, R., White, M., Jang, J., Whitfill, T., Auerbach, M., & INSPIRE LP investigators. (2015). Impact of just-in-time and just-in-place simulation on intern success with infant lumbar puncture. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1237-1246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014 -1911

Kirkpatrick, D., & Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kroft, J., Ordon, M., Po, L., Zwingerman, N., Waters, K., Lee, J. Y., & Pittini, R. (2017). Preoperative practice paired with instructor feedback may not improve obstetrics-gynaecology residents’ operative performance. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(2), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00238.1

Lal, B. K., Cambria, R., Moore, W., Mayorga-Carlin, M., Shutze, W., Stout, C. L., Broussard, H., Garrett, H. E., Nelson, W., Titus, J. M., Macdonald, S., Lake, R., & Sorkin, J. D. (2022). Evaluating the optimal training paradigm for transcarotid artery revascularization based on worldwide experience. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 75(2), 581-589.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.08.085

Liao, W.-C., Leung, J. W., Wang, H.-P., Chang, W.-H., Chu, C.-H., Lin, J.-T., Wilson, R. E., Lim, B. S., & Leung, F. W. (2013). Coached practice using ERCP mechanical simulator improves trainees’ ERCP performance: A randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy, 45(10), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1344224

Lin, Y., Cheng, A., Hecker, K., Grant, V., & Currie, G. R. (2018). Implementing economic evaluation in simulation-based medical education: Challenges and opportunities. Medical Education, 52(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13411

Mankute, A., Juozapaviciene, L., Stucinskas, J., Dambrauskas, Z., Dobozinskas, P., Sinz, E., Rodgers, D. L., Giedraitis, M., & Vaitkaitis, D. (2022). A novel algorithm-driven hybrid simulation learning method to improve acquisition of endotracheal intubation skills: A randomized controlled study. BMC Anaesthesiology, 22(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01557-6

McGaghie, W. C. (2015). Mastery learning: It is time for medical education to join the 21st century. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1438–1441. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000911

McGaghie, W. C., Issenberg, S. B., Cohen, E. R., Barsuk, J. H., & Wayne, D. B. (2011). Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 86(6), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

Mduma, E., Ersdal, H., Svensen, E., Kidanto, H., Auestad, B., & Perlman, J. (2015). Frequent brief on-site simulation training and reduction in 24-h neonatal mortality—An educational intervention study. Resuscitation, 93, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.019

Naples, R., French, J. C., Han, A. Y., Lipman, J. M., & Awad, M. M. (2022). The impact of simulation training on operative performance in general surgery: Lessons learned from a prospective randomized trial. Journal of Surgical Research, 270, 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.10.003

Nestel, D., Groom, J., Eikeland-Husebø, S., & O’Donnell, J. M. (2011). Simulation for learning and teaching procedural skills: The state of the science. Simulation in Healthcare, 6 Suppl, S10-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e318227ce96

Nickson, C. P., Petrosoniak, A., Barwick, S., & Brazil, V. (2021). Translational simulation: From description to action. Advances in Simulation (London, England), 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-021-00160-6

Nilsson, C., Sorensen, J. L., Konge, L., Westen, M., Stadeager, M., Ottesen, B., & Bjerrum, F. (2017). Simulation-based camera navigation training in laparoscopy—A randomized trial. Surgical Endoscopy, 31(5), 2131–2139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5210-5

Orzech, N., Palter, V. N., Reznick, R. K., Aggarwal, R., & Grantcharov, T. P. (2012). A comparison of 2 ex vivo training curricula for advanced laparoscopic skills: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 255(5), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824aca09

O’Sullivan, O., Iohom, G., O’Donnell, B. D., & Shorten, G. D. (2014). The effect of simulation-based training on initial performance of ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus blockade in a clinical setting—A pilot study. BMC Anaesthesiology, 14, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2253-14-110

Patel, V., Aggarwal, R., Osinibi, E., Taylor, D., Arora, S., & Darzi, A. (2012). Operating room introduction for the novice. American Journal of Surgery, 203(2), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.03.003

Schaefer, J. J., Vanderbilt, A. A., Cason, C. L., Bauman, E. B., Glavin, R. J., Lee, F. W., & Navedo, D. D. (2011). Literature review: Instructional design and pedagogy science in healthcare simulation. Simulation in Healthcare, 6 Suppl, S30-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e31822237b4

Schaffer, A. C., Babayan, A., Einbinder, J. S., Sato, L., & Gardner, R. (2021). Association of simulation training with rates of medical malpractice claims among obstetrician-gynaecologists. Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 138(2), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004464

Sharara-Chami, R., Taher, S., Kaddoum, R., Tamim, H., & Charafeddine, L. (2014). Simulation training in endotracheal intubation in a paediatric residency. Middle East Journal of Anaesthesiology, 22(5), 477–485.

Shore, E. M., Grantcharov, T. P., Husslein, H., Shirreff, L., Dedy, N. J., McDermott, C. D., & Lefebvre, G. G. (2016). Validating a standardized laparoscopy curriculum for gynaecology residents: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 215(2), 204.e1-204.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.037

Sørensen, J. L., Navne, L. E., Martin, H. M., Ottesen, B., Albrecthsen, C. K., Pedersen, B. W., Kjærgaard, H., & van der Vleuten, C. (2015). Clarifying the learning experiences of healthcare professionals with in situ and off-site simulation-based medical education: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 5(10), e008345. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008345

Srinivasan, K. K., Gallagher, A., O’Brien, N., Sudir, V., Barrett, N., O’Connor, R., Holt, F., Lee, P., O’Donnell, B., & Shorten, G. (2018). Proficiency-based progression training: An “end to end” model for decreasing error applied to achievement of effective epidural analgesia during labour: A randomised control study. BMJ Open, 8(10), e020099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020099

Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Centeno, A., Dolmans, D., Spencer, J., Gelula, M., & Prideaux, D. (2006). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Medical Teacher, 28(6), 497–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600902976

Tan, T. X., Buchanan, P., & Quattromani, E. (2018). Teaching residents chest tubes: Simulation task trainer or cadaver model? Emergency Medicine International, 2018, 9179042. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9179042

Tavares, W., Eppich, W., Cheng, A., Miller, S., Teunissen, P. W., Watling, C. J., & Sargeant, J. (2020). Learning conversations: An analysis of the theoretical roots and their manifestations of feedback and debriefing in medical education. Academic Medicine, 95(7), 1020–1025. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002932

Tchorz, J. P., Brandl, M., Ganter, P. A., Karygianni, L., Polydorou, O., Vach, K., Hellwig, E., & Altenburger, M. J. (2015). Pre-clinical endodontic training with artificial instead of extracted human teeth: Does the type of exercise have an influence on clinical endodontic outcomes? International Endodontic Journal, 48(9), 888–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12385

Todsen, T., Henriksen, M. V., Kromann, C. B., Konge, L., Eldrup, J., & Ringsted, C. (2013). Short- and long-term transfer of urethral catheterization skills from simulation training to performance on patients. BMC Medical Education, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-29

Tolsgaard, M. G., Madsen, M. E., Ringsted, C., Oxlund, B. S., Oldenburg, A., Sorensen, J. L., Ottesen, B., & Tabor, A. (2015). The effect of dyad versus individual simulation-based ultrasound training on skills transfer. Medical Education, 49(3), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12624

Walsh, C. M., Scaffidi, M. A., Khan, R., Arora, A., Gimpaya, N., Lin, P., Satchwell, J., Al-Mazroui, A., Zarghom, O., Sharma, S., Kamani, A., Genis, S., Kalaichandran, R., & Grover, S. C. (2020). Non-technical skills curriculum incorporating simulation-based training improves performance in colonoscopy among novice endoscopists: Randomized controlled trial. Digestive Endoscopy, 32(6), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.13623

Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Motor skill learning and performance: A review of influential factors. Medical Education, 44(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03421.x

Zendejas, B., Brydges, R., Wang, A. T., & Cook, D. A. (2013). Patient outcomes in simulation-based medical education: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(8), 1078–1089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2264-5

*Matthew Low

Emergency Medicine Department,

National University Hospital

9 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Level 4,

Singapore 119085

Email: mlow@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 24 October 2024

Accepted: 5 July 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 26-34

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/OA3552

Shoko Horita1,2, Masashi Izumiya2, Satoshi Kondo2,3,4, Junki Mizumoto2,5,6, Hiroko Mori6,7 & Masato Eto2

1Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, Teikyo University, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan; 2Department of Medical Education Studies, International Research Centre for Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan; 3Department of Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan; 4Center for Medical Education and Career Development, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan; 5Department of Family Practice, Ehime Seikyo Hospital, Matsuyama, Ehime, Japan; 6Center for General Medicine Education, School of Medicine, Keio University, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan; 7Professional Development Centre, The University of Tokyo Hospital, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Abstract

Introduction: Conventionally, face-to-face education has been prevalent in medical education because it can help medical students learn interpersonal skills, including medical interviews and physical examination. However, because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, face-to-face education was suspended to prevent the spread of the infection. As face-to-face classes in Japan were discontinued when the pandemic began in the spring of 2020, we developed an online education program to develop medical interview skills. We were interested in determining the educational outcomes between face-to-face and online medical interview classes. Therefore, we compared them before and after the pandemic.

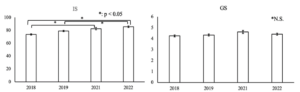

Methods: Fourth-year students of the University of Tokyo Medical School took medical interview classes. Under consent, the score of the medical interview area of the preclinical clerkship, Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), as a high-stakes examination, which falls at the top level of the Kirkpatrick’s model, was compared by year or before and after the pandemic.

Results: The online group showed higher item-wise scores of the medical interview of the preclinical clerkship OSCE than the face-to-face group. In terms of the global score, no significant difference was observed. In the computer-based test (CBT), the online group had higher scores compared with the face-to-face group.

Conclusion: The educational outcomes of online medical interview classes were not inferior to those of conventional face-to-face classes, as revealed by high-stakes examination preclinical clerkship OSCE. Similar to face-to-face education, online education is a viable option for developing interpersonal skills.

Keywords: COVID-19 Pandemic, Medical Interview, OSCE, Educational Outcome, Online Education, Interpersonal Skills, Communication Skills

Practice Highlights

- Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we shifted medical interview classes from face-to-face to online.

- The online group had interview global OSCE scores non-inferior to those of the face-to-face group.

- The online group had higher interview elementary OSCE scores than the face-to-face group.

I. INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic severely restricted face-to-face teaching and affected almost all levels and fields of education, including undergraduate preclinical medical education (Bastos et al., 2022; Crawford et al., 2020). Moreover, it resulted in drastic changes in medical education. Globally, face-to-face learning was forcibly discontinued as part of infection control. Thus, to continue medical education, online or remote learning was rapidly introduced (Daniel et al., 2021; Gordon et al., 2020). Various instrumental trans communication devices, including video conferencing tools, simulation, virtual reality, and augmented reality, were used to facilitate online learning. However, this rather hasty shift from face-to-face to online learning brought some confusion into the field of medical education. In the UK, Dost et al. (2020) reported that medical students were unsatisfied with online classes compared with face-to-face classes.

Globally, tele-education is increasingly being encouraged around the world (American Medical Association, 2016). In the field of medical interview (Budakoğlu et al., 2021; Hammersley et al., 2019; Zaccariah et al., 2022), telemedicine is gradually becoming common, showing favourable results. However, because of technical problems, tele-education did not spread smoothly (Zaccariah et al., 2022). Additionally, the educational outcomes of both strategies have not been satisfactorily studied (Khamees et al., 2022). Recently, some reports showing that the educational outcome of online classes are equal or more effective than traditional face-to-face education, however, they are restricted mainly in knowledge-based education (Alshaibani et al., 2023; Basuodan, 2024; Saad et al., 2023). Furthermore, few studies have compared high-stakes examination, including the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), and no study has compared the educational results between face-to-face classes and tele-education (online) using the top level of Kirkpatrick’s model (Kirkpatrick, 1996).

The OSCE (Harden et al., 1975) has been widely accepted as a form to assess clinical performance in medical education. Currently, OSCEs are used worldwide to appraise medical students’ communication and clinical skills. Various educational methods have been evaluated using OSCE as one of the indicators of educational outcomes (Guetterman et al., 2019). In Japan, passing the preclinical clerkship (pre-CC) OSCE has become legally obligatory as one of the elements for promotion to the CC course since the spring of 2023. In 2023, the pre-CC OSCE in Japan is conducted in at least eight areas, which are medical interview, “Basic Clinical Procedure”, “Basic Life Support”, and physical examinations of “head and neck”, “chest”, “vital signs”, “abdomen”, and “neurological examinations”.

In the present study, we aimed to determine the educational outcomes between face-to-face and online medical interview classes. We provided medical interview classes to fourth-year medical students before taking the pre-CC OSCE, face-to-face classes before 2019, and tele-education (online) after 2020. We decided to conduct research in medical interview, other than the other areas of the pre-CC OSCE, because of the importance of the medical interview as the basis of medical practice. Moreover, it was inevitable that the medical interview classes had to be implemented as online classes to protect the simulated patients form the risk of infection, which was another main reason for selecting medical interview for this research. In another point of view, medical interview classes were able to implement via online. As mentioned above, no prior studies have compared face-to-face and online medical interview training using both high-stakes OSCE score and Kirkpatrick’s top-level outcomes, our study would have significant importance.

II. METHOD

A. Participants

This study was approved in 2021 by the ethics committee of the University of Tokyo (UTokyo) Faculty of Medicine (Approval No. 2021005NI). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Moreover, the data of students who provided consent for the secondary use of their data (Approval No. 11763) in another research approved in 2017 were included.

B. Sample Population