Implicit leadership theories and followership informs understanding of doctors’ professional identity formation: A new model

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2017, 2(2), 18-23

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-2/OA1022

Judy McKimm, Claire Vogan & Hester Mannion

Swansea University Medical School, Swansea University, United Kingdom

Abstract

Aims: The process of becoming a professional is a lifelong, constantly mediated journey. Professionals work hard to maintain their professional and social identities which are enmeshed in strongly held beliefs relating to ‘selfhood’. The idea of implicit leadership theories (ILT) can be applied to professional identity formation (PIF) and development, including self-efficacy. Recent literature on followership suggests that leaders and followers co-create a dynamic relationship and we suggest this occurs commonly in the clinical setting. The aim of this paper is to describe a new model which utilises ILT and followership theory to inform our understanding of doctors’ PIF.

Methods: Following a literature review, we applied the core concepts of ILT and followership theories to theories underlying PIF by developing a mapping framework. We identified core themes, similarities and differences between the three perspectives and constructed a new model of PIF incorporating elements from ILT and followership. The model can be used to explain and inform understanding of medical practice and leadership situations.

Conclusion: The model offers insight into how concepts such as self-efficacy, prototypicality, implicit theories of self, power, authority and control and cultural competence result in PIF. Bringing together the theoretical frameworks of ILT and followership theory with PIF theories helps us understand and explain the unique dynamic of the clinical environment in a new light; prompting new ways of thinking about teams, interprofessional working, leadership and social identity in medicine. It also offers the potential for new ways of teaching, curriculum design, learning and assessment.

Keywords: Followership; Leadership; Professional Identity; Self Efficacy

Practice Highlights

- Doctors have a deep rooted professional and social identity that is closely connected with notions of leadership.

- New insight into professional identity formation can be achieved by applying the theoretical frameworks of implicit leadership theories, followership, and self efficacy.

- A better understanding of professional identity formation could potentiate new ways of approaching medical education and curriculum design.

I. INTRODUCTION

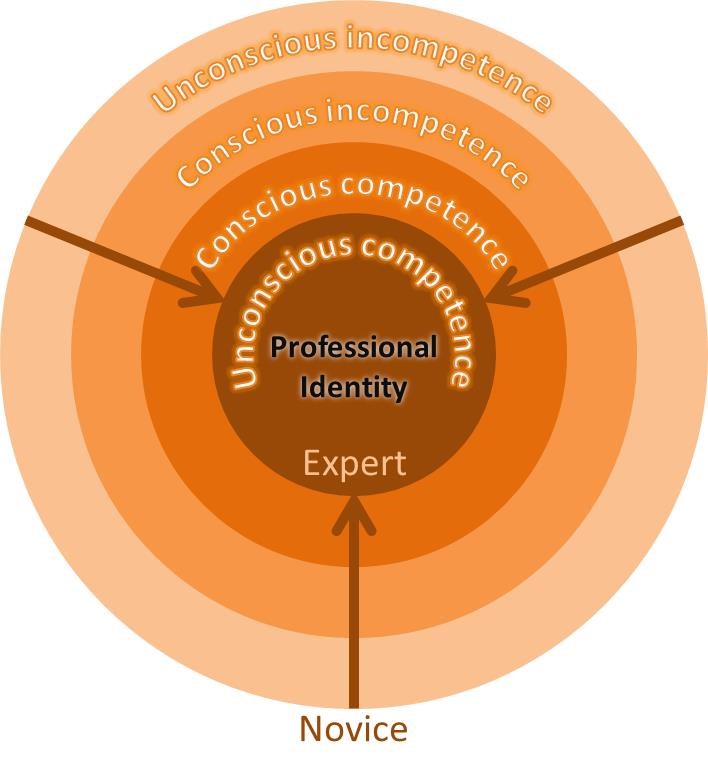

Doctors’ professional identity formation (PIF) is informed by many factors in the professional environment and is also inextricably linked to social status and personal identity. The professional identity of a doctor is a personal one before it is a group one. The emphasis on personal career progression, competition with peer group and relative autonomy in senior positions starts at medical school, this risks a prevailing attitude amongst physicians that they are ‘lone healers’ (Lee, 2010), causing inevitable problems with team-working. An understanding of how professional identity formation comes about is vital to an understanding of how doctors function in leadership, followership and team-working roles. Our model aligns this for practical developmental purposes with the ‘inbound trajectory’ adapted from the ‘novice to expert model of professional competence’ (Flower, 1999) (see Fig 1).

This model identifies that professional competence develops over time with feedback and reflection. Individuals become part of a ‘community of practice’ as they move along an ‘inbound trajectory’ towards being ‘expert’ (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015). In terms of professional identity formation in ‘becoming a doctor’, a ‘novice’ would not be really aware of the ‘reality’ of medicine, what being a doctor is about or how medicine is positioned vis a vis other professionals. Gradually, through trial and error, observation, conversations and ‘heat experiences’ (significant learning events)(Petrie, 2014), a more rounded and mature professional identity develops so that by the time the doctor is seen as ‘expert’ by others, they also see themselves as proficient, competent professionals distinct from other health workers. The following sections discuss followership theory; implicit leadership theory and implicit theories of the self and conclude by offering suggestions as to how our integrated model of professional identity formation can be used to develop doctors’ leadership, followership and team working skills.

Figure 1. Development of professional identity: A diagrammatic representation of desired inbound trajectory along the ‘novice to expert model of professional competence’ (Flower, 1999).

Figure 1. Development of professional identity: A diagrammatic representation of desired inbound trajectory along the ‘novice to expert model of professional competence’ (Flower, 1999).

II. FOLLOWERSHIP THEORY

Followership theory provides a much needed alternative perspective in a world of leadership-centric models. Leadership, management and followership form an interlinked triad of activities (Till & McKimm, 2016). A consideration of followership informs our understanding of leadership by describing the influence that followers have on their leaders and the process of ‘co-creation’ that occurs as a result of the impact that followers have on leaders and leadership styles (Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe & Carsten, 2014). In leadership-centric thinking, followers are often described in terms of subordination or even derogation. Followership thinking, by contrast, highlights the importance of followership behaviour in facilitating and forming leadership. Followership describes individuals who are more than just those who are ‘not-leading’ or ‘not-leading right now’. Followership practice varies as much as leadership practice, ranging from star-followers who represent an engaged and dynamic influence to those who make effort to be obstructive to team progress and challenge leaders’ authority. Followers can therefore have positive or negative powerful impact on the direction of a team and leadership efficacy. The identity of ‘leader’ and ‘follower’ must be considered fluid, all followers lead and all leaders follow in different contexts.

Doctors who follow are often seen (and see themselves) as ‘leaders in waiting’, ready to move along the ‘inbound trajectory’ by engaging in ‘small ‘l’’ activities (Bohmer, 2012) and moving up the medical hierarchy. Medical schools encourage students to compete with one another, to stand out and win prizes. This continues in the working environment where recognition and reward is for those who can show their personal contribution to service provision and improvement. As a result, it becomes culturally acceptable and desirable to aspire to leadership roles and to place personal career progression over team success, this has profound implications for team working in health services. Real team working in UK hospitals has been described as no more than an ‘illusion’ (West & Lyubovnikova, 2013), with groups of people working in ‘pseudo-teams’. Effective team work requires clear, defined and shared goals, when there is no meaningful team dynamic, quality of patient care must suffer. Although many Medical Councils highlight the importance of team-working in their professional standards, the notion of aspiring to outstanding followership is countercultural in medicine, partly because it is potentially threatening to professional identity.

III. IMPLICIT LEADERSHIP SOCIAL IDENTITY THEORY

One follower-centric approach encompasses the Implicit Leadership Theories (ILTs), which state that followers hold pre-conceived beliefs (almost stereotypes) about what makes a good or a bad leader. The ILTs are often based on a range of generic characteristics (such as height, gender, ethnic or professional background) and played out in practice through unconscious biases. Given the central role that followers play in creating and facilitating leadership, those leaders whose ‘faces don’t fit’ (for whatever reason) may have a difficulty persuading their followership to follow. Those who do not fit the pre-conceived implicit criteria may have to work much harder to gain the trust of a followership, this is regardless of the leader’s expertise and ability to lead. A followership of doctors has deep-seated pre-conceived beliefs about what their clinical leaders should look like. On an individual level these are created by past experiences and personal needs, on a group level these are created by professional culture, which, in turn, creates and is created by professional identity. Celebrated leaders in the world of medicine are usually those who are clinically excellent or high flying researchers, and who have personal charisma (the stereotypical ‘hero leader’), not necessarily those who display exceptional leadership, management and followership qualities in an everyday context. This may be because of the centrality of clinical ability in the professional and personal identity of doctors and may also help explain the relative reluctance of many doctors to move to the ‘dark side’ of healthcare management.

Social identity theory describes followers who identify closely with a leader as ‘high-identifiers’, the extent to which the leader represents the group they lead is referred to as their ‘prototypicality’.

Doctors, who commonly have aspirations to lead, are likely to be ‘high-identifiers’, closely identifying with the leader and the rest of the group, both socially and professionally. High-identifiers are more likely to be affected by group level behaviour but also have high expectations of procedural fairness in their leader and are more likely to be openly critical of leadership decisions. Prototypicality is also very important in clinical leadership, as doctors who follow identify closely with their leaders, they also expect them to look and sound like them, and most importantly they expect them to maintain a successful clinical role. Leaders in health services who do not have a clinical role are often viewed by doctors as an ‘out-group’, a good example of this might be non-clinical managers who are frequently mistrusted and blamed for health service failings. Problems may also arise in multi-disciplinary team settings where doctors, nurses and allied health professionals are required to work closely together. Doctors in this context may struggle to take leadership initiatives from those who are not doctors, however appropriate it is for that person to lead and how ever well qualified they are to do so (Barrow, McKimm & Gasquoine, 2011). Doctors who lead with the full support of their followership may not, therefore, be the most appropriate or able to lead, as their leadership expertise and ability is rarely that which is under scrutiny, rather it is their prototypicality that ensures loyalty. From this perspective, professional identity formation is therefore tied very closely to identifying with prototypical doctors and learning how to be like them. Whilst it can be helpful for individuals who ‘fit’, it can perpetuate a ‘people like us’ mentality and reluctance to welcome people seen as part of an ‘out-group’ into the profession (McKimm & Wilkinson, 2015) or into teams, which runs counter to inclusive leadership and celebration of diverse communities of practice.

IV. IMPLICIT THEORIES OF THE SELF AND SELF-EFFICACY

Implicit theories of the self-relate to domain specific ideas about identity and ability (Molden & Dweck, 2006). This framework divides people into two groups: ‘entity’ theorists who see their professional or social identity as rigid and fixed, and ‘incremental’ theorists who view their professional or social identity as malleable and developmental. In the clinical environment, doctors who hold entity theories regarding their professional identity are likely to find challenges to their professional identity difficult to manage. Such challenges may come in the form of non-doctors taking leadership roles, making a mistake or having a poor clinical outcome. Conversely, a doctor who holds incremental theories regarding professional identity is more likely to embrace and engage with challenges to preconceived identities, whether that is with new ways of working or in looking critically at long established systems. The question of whether doctors are more likely to be entity or incremental theorists in their professional lives is important. The study and practice of medicine can be lucrative and rewarding, but the lengthy training is rigid and prescriptive in many ways. It is reasonable to suggest that there may by a higher percentage of entity theorists amongst doctors than in other professions, not least because of the solid professional and social identity that it conveys. How fixed or fluid a follower feels about their own professional identity will directly impact how fixed or fluid they might feel about their leader, those who hold entity theories about their own professional identity are more likely to have a fixed idea about whether their leaders are fit for the job with little tolerance of those that do not meet their expectations. They are also likely not to appreciate the fluid nature of followership and leadership, with certain ‘types’ being deemed appropriate for simply one or the other.

‘Self-efficacy’ is a domain specific description of self-esteem (which can be understood as global) (Burnette, Pollack & Hoyt, 2010), high self-efficacy in the professional environment implies high professional self-confidence. For doctors with entity theories, high or low self-efficacy will impact their response to their own failings in the clinical environment. For example, those with inflexible entity theories and high self-efficacy (or high professional self-esteem) are likely to view mistakes as somebody else’s fault, alternatively, a doctor with low self-efficacy will be badly affected and possibly debilitated by a mistake. An incremental theorist is more likely to turn their attention to the detail of mistakes made, address them head on without fear and change future practice in light of them. Self-efficacy also effects desired protoypicality. If a doctor has low professional self-efficacy, they will desire leaders who do not look like them, those with high self-efficacy will be a high-identifier and the more prototypical the leader, the more effective they will be perceived to be.

V. AN INTEGRATED MODEL OF PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY FORMATION

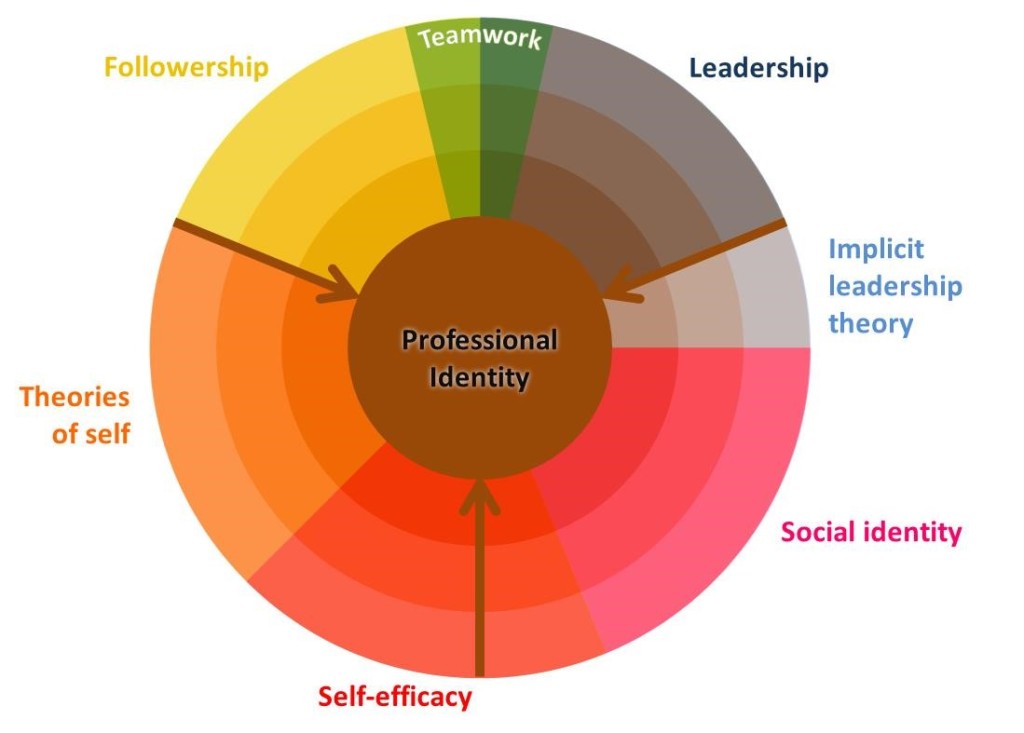

So, how do these theories help our understanding of doctors’ professional identity formation in terms of their leadership, followership and team working approaches and skills? The model (Fig 2) maps the theoretical domains discussed in this paper onto the ‘novice to expert model’ which we suggest can be aligned with ‘becoming a doctor’. We have discussed how engagement in a range of activities can help doctors move along the inbound trajectory towards expertise. Such expertise has at its centre a professional identity which is fully aligned with social and self-identity, underpinned by accurate understanding of self-efficacy. These ‘experts’ belong firmly in their community of practice, however that is defined. We suggest also that an explicit focus on specific development activities, underpinned by the theories discussed here, will help develop doctors to function more effectively in multi-cultural and diverse health services and in interprofessional teams. An example of this in undergraduate training would be to give medical students opportunities to work with nursing students early on, this would help both groups to better understand each other and ‘normalize’ interprofessional teamwork at a formative stage.

Specifically, the model provides a framework for educators, supervisors and individuals to plan activities and development opportunities in three key areas of activity: leadership, followership and team working to support students and doctors to become ‘expert professionals’. Whilst some of the techniques are similar to that used in coaching, education or mentoring, the theoretical perspectives described here integrate the literature on team working, followership, leadership, (including implicit leadership theories), theories of self (including self-efficacy) and social and professional identity theory in a unique way. For example, when working with students and doctors in groups and teams (in real or simulated environments), teachers could set activities aimed towards developing shared team goals, ensuring leadership happens and the outcomes are effective. As part of the process, teachers should make explicit reference to and facilitate discussion about team roles, personality preferences and how to take both leadership and followership roles. Educational leaders might facilitate activities that focus on exploring and surfacing unconscious biases about other professional groups, patients or families or by giving and obtaining multi-source feedback on self-efficacy in interprofessional groups and teams. Such activities need to be carefully facilitated in an inclusive environment as much of this work relates directly to people’s views and feelings about ‘self’. This can be quite threatening if not carried out in a safe psychological and physical environment. Using structured debriefs, role modelling inclusive leadership behaviours, sharing appropriate aspects of teachers’ own development, experiences and difficulties will help learners gain self-knowledge and interpersonal skills and reap great benefits for practice.

Within the model, reflective practice plays a key role in challenging unhelpful behaviours and restrictive ways of thinking. As reflection becomes a normal part of training, so might doctors become more comfortable with the process of critically examining choices and learning needs. Universities and post-graduate training programmes can highlight the importance of reflective practice in the development of a well-rounded practitioner by rewarding personal development as well as attainment. Recognizing and rewarding those who show the ability to adapt and evolve will raise the profile of the softer but vital skill of reflection.

Figure 2. An integrated model that shows the development of a doctors’ professional identity formation, on an inbound trajectory (see Fig 1), through experience and gaining knowledge and understanding of leadership, followership, team working, implicit leadership theory, social identity, self-efficacy and theories of self

Figure 2. An integrated model that shows the development of a doctors’ professional identity formation, on an inbound trajectory (see Fig 1), through experience and gaining knowledge and understanding of leadership, followership, team working, implicit leadership theory, social identity, self-efficacy and theories of self

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Followership, leadership and team-working in medicine are all directly impacted by professional identity formation. Doctors develop as professionals to hold respected positions, to aspire to a degree of autonomous decision making and leadership roles; they are encouraged to compete with their peers and to put their energies in to personal career progression. A better understanding of the culture within medicine and professional identity formation may not only help us to understand the complex dynamic between leaders and followers, but also enable better team working among health professionals. Providing doctors at all stages of training with specific development opportunities designed to enable the acquisition of team working, leadership and followership skills will help more effective team working and improve healthcare. This model provides a structured framework for designing such development activities.

Notes on Contributors

Judy McKimm is Professor of Medical Education, Director of Strategic Educational Development and Director of the MSc in Leadership for the Health Professions at Swansea University. She runs clinical and educational leadership programmes around the world and publishes widely on leadership and education.

Claire Vogan is an Associate Professor at Swansea University Medical School and the Director of Student Support and Guidance for Graduate Entry Medicine. She specialises in the support of students in difficulty and teaches on the Leadership, Medical Education and Graduate Entry Medicine programmes in Swansea.

Hester Mannion graduated from the University of Exeter with a 1st class degree in English Literature and went on to gain a PGCE from King’s College London. She has graduated from Swansea University Medical School in 2016 and now working as a doctor in Wales.

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest, including no financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

References

Barrow, M., McKimm, J., & Gasquoine, S. (2011). The policy and the practice: Early-career doctors and nurses as leaders and followers in the delivery of health care. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 16(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9239-2.

Bohmer, R. (2012). The instrumental value of medical leadership. White Paper-The King’s Fund, London, England. Retrieved from

http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/instrumental-value-medical-leadership-richard-bohmer-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., & Hoyt, C. L. (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of leadership ability and self‐efficacy: Predicting responses to stereotype threat. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 46-56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.20138.

Flower, J. (1999). In the Mush. Physician Executive, 25(1), 64–66.

Lee, T.H. (2010). Turning doctors into leaders. Harvard Business Review, 88(4), 50-58.

McKimm, J., & Wilkinson, T. (2015). “Doctors on the move”: Exploring professionalism in the light of cultural transitions. Medical Teacher, 37(9), 837-843. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1044953.

Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Finding “meaning” in psychology: a lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192.

Petrie, N. (2014). Future trends in leadership development. Center for Creative Leadership white paper. Retrieved from http://insights.ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/futureTrends.pdf

Till, A, & McKimm, J. (2016). Leading from the frontline. BMJ, in press.

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 83-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007.

Wenger-Trayner, E, & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice a brief introduction. Retrieved from http://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

West, M. A., & Lyubovnikova, J. (2013). Illusions of team working in health care. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 27(1), 134-142. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777261311311843.

*Judy McKimm

Grove Building, Swansea University

Singleton Park, Swansea, SA2 8PP

Tel: (01792) 606854

Email: j.mckimm@swansea.ac.uk

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.