Impact of reflective writings on learning of core competencies in medical residents

Submitted: 16 January 2021

Accepted: 17 May 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 65-79

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/OA2447

Yee Cheun Chan1, Chi Hsien Tan1 & Jeroen Donkers2

1Department of Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore; 2Department of Educational Development and Research, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Abstract

Introduction: Reflection is a critical component of learning and improvement. It remains unclear as to how it can be effectively developed. We studied the impact of reflective writing in promoting deep reflection in the context of learning Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies among residents in an Internal Medicine Residency programme.

Methods: We used a convergent parallel mixed-methods design for this study in 2018. We analysed reflective writings for categories and frequencies of ACGME competencies covered and graded them for levels of reflection. We collected recently graduated residents’ perceptions of the value of reflective writings via individual semi-structured interviews.

Results: We interviewed nine (out of 27) (33%) participants and analysed 35 reflective writings. 30 (86%) of the writings showed a deep level (grade A or B) of reflection. Participants reflected on all six ACGME competencies, especially ‘patient care’. Participants were reluctant to write but found benefits of increased understanding, self-awareness and ability to deal with similar future situations, facilitation of self-evaluation and emotional regulation. Supervisors’ guidance and feedback were lacking.

Conclusion: We found that a reflective writing programme within an Internal Medicine Residency programme promoted deep reflection. Participants especially used self-reflection to enhance their skills in patient care. We recognised the important role of mentor guidance and feedback in enhancing reflective learning.

Keywords: Reflective Writing, ACGME Competencies, Internal Medicine, Residency

Practice Highlights

- Reflection is a critical component of learning and improvement.

- Written reflections offer theoretical advantages over other forms of reflections in requiring more commitment and ownership of experience, promoting critical thinking and offering more opportunities for feedback.

- Written reflections can be a record for mentored reflection, included in a portfolio, used in ongoing self-assessment and longitudinal integration of learning.

- Practitioners reported benefits of increased understanding, self-awareness and ability to deal with similar future situations, facilitation of self-evaluation and emotional regulation.

- Supervisors’ guidance and feedback are important for enhancing reflective learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical competencies are developed through experience and application, not just knowledge acquisition (Frank et al., 2010). Kolb (1984) conceptualises experiential learning in a four-stage cyclical process. An experience triggers a reflection on that experience that leads to the formation of abstract concepts and generalisations. These are then tested in future situations, resulting in new experiences. Reflection is an essential aspect of the learning experience. It remains unclear how it can be developed most effectively.

Reflection is a complex concept that has been defined in several ways. One definition describes it as the process of engaging self in attentive, critical, exploratory, and iterative interactions with one’s thoughts and actions, and their underlying conceptual frame, with a view on the change itself (Nguyen et al., 2014). Thus, reflection has an iterative dimension which describes a cyclic process with phases triggered by experience, which produces new understanding, and then an intention to act differently in future encounters of similar experience (Mann et al., 2009). There is also a vertical dimension correlating to the depth of reflection. The surface levels are more descriptive and less analytical than the deeper levels. For example, Boud et al. (1985) described iterative phases of returning to experience, attending to feelings, re-evaluation of experience and outcome/resolution. Mezirow (1991) described increasing depth of reflection as habitual action, thoughtful action/understanding, reflection, critical reflection. Evidence suggests that deeper levels of reflections are associated with deep approaches to learning (Leung & Kember, 2003).

Reflective writing is a commonly utilised method in developing reflective learning but evidence for its value remains limited. Theoretically, written reflections offer advantages over other types of reflections e.g. verbal discussions. Creating an artefact by writing involves a commitment to learning, ownership of experience, promotes critical thinking and offers more opportunities for feedback (Aronson, 2011). The writings can be a record for mentored reflection, included in a portfolio, used in ongoing self-assessment and longitudinal integration of learning. A systematic review (Winkel et al., 2017) looking at the impact of reflection in graduate medical education found only three studies (Epner & Baile, 2014; Levine et al., 2008; Winkel et al., 2010) that involved reflective writings. Levine et al. (2008) found that the process of narrative writings encouraged deepening of reflection leading to reconsideration of core values and priorities, improved self-awareness, provided an emotional outlet and motivation to improve. However, the study did not formally gauge the depth of reflections in the writings.

We aimed to further study the impact of reflective writing in promoting reflection and the learning of medical competencies. Better understanding this will guide the development of reflective learning skills in training programmes for medical trainees.

A. Research Question

Does reflective writing promote deep reflection in the context of learning core competencies defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2013)?

II. METHODS

A. Research Paradigm and Design

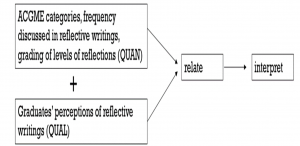

Our study adopted a phenomenological approach. We used a convergent parallel mixed-methods design (Figure 1). Quantitative data included the tabulation of the categories of ACGME competencies and the frequency they were covered in the reflective writings. Quantitative scoring of levels of reflections in the reflective writings was done using two grading scales. Qualitative data included graduates’ perceptions of the value and effects of reflective writings on learning ACGME competencies. The quantitative and qualitative data were analysed, compared and related together to answer the research question.

Figure 1. Convergent parallel mixed-methods design to study the role of reflective writing in promoting reflective learning of ACGME competencies

B. Study Setting and Subjects

The study setting was the Internal Medicine Residency of a single tertiary university hospital in 2018. We have used reflective writing as a tool for developing reflective learning and practice in our Internal Medicine Residency. Our programme has a competency-based curriculum using the ACGME framework. Residents are encouraged to write their reflections on how an encounter or situation helped them develop one or more of the competencies. They are required to include at least two such reflective writings in their portfolio each year. The reflective writings are not graded but are read by the residents’ supervisors as part of their portfolio’s content during regular reviews and by the competency review committee during 6-monthly meetings. They provide insight into the residents’ competencies development.

We invited all past residents (27) who graduated from the programme one year earlier to participate. We used a convenience sampling method. We determined the final number of participants after data saturation was reached in the analysis of the collected qualitative data.

The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (NHG DSRB) (Reference number: 2017/01219). We obtained informed consent from each participant.

C. Data Collection

We collected and analysed reflective writings from the participants’ three years of residency. We used individual semi-structured interviews to gather participants’ perceptions to avoid bias from others’ opinions. One researcher (YCC) conducted, recorded and transcribed the interviews. Box 1 shows the main questions that were asked. An interactive approach was used, and interviews conducted till thematic saturation was reached.

Box 1. Main questions asked during interviews

D. Data Analysis

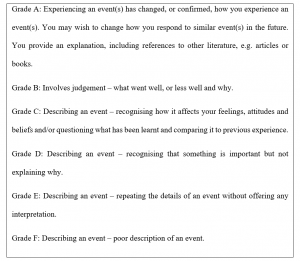

Reflective writings from participants were analysed for the categories as well as frequencies of ACGME competencies covered. They were graded for levels of reflection using grading rubrics. To reduce possible interpretation bias or conflicts related to confidentiality and power relationships, grading was done by an ‘external’ co-researcher (CHT) who was a faculty member of the Neurology residency programme. Two grading scales were used. The first (Box 2) had a simple grading scale from A to F (Moon, 2004). The other grading rubric provided more categorical details and was based on that used by Tsingos et al. (2015) (Supplementary Table 1). The rubric graded the reflective writings on seven stages of reflection based on the model by Boud et al. (1985) and categories of non-reflector, reflector or critical reflector according to Mezirow’s model (Mezirow, 1991). The co-researcher read through each reflective writing and first determined if stages of ‘returning to experience’, ‘attending to feelings’, ‘association’, ‘integration’, ‘validation’, ‘appropriation’ and ‘outcomes of reflection’ were present. He then assessed if the written content related to these stages fit the descriptors for non-reflector, reflector or critical reflector as given in the rubric. Finally, he graded the reflective writing on the simple grading scale of A to F according to the descriptors given (Box 2).

Qualitative data from interviews were transcribed in full, coded and thematically analysed (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Coding and analysis were independently done by two researchers (YCC, CHT) before discussions to reach consensus. Each interview was analysed after its completion and before subsequent interviews. Thematic saturation was determined by the absence of any new themes emerging from the analysis of the previous three interviews. This was reached after six interviews. Three further interviews were conducted after that. The participants were asked if the results of the thematic analysis were a fair interpretation of the discussions. Peer debriefing processes were employed to enhance the validity of the study. Validity was enhanced by triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data.

III. RESULTS

A. Demographic Data

There were nine participants in the study. This represented 33% of the study population (27). There were five males and four females. Five were Singaporean. The other four were from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Hong Kong in China and Myanmar. Five attended undergraduate medical school in Singapore, two in Australia, one in the United Kingdom and one in Myanmar. One participant, age 45, was more than ten years older than the others. The mean age of the other eight participants was 29.4 years, with ages ranging from 27 to 32. Apart from the oldest participant, the others were between four to seven years post medical school graduation. The gender ratio of the participants is similar to that of the study population while the proportion of international graduates among the participants was higher (44% vs 30%).

B. Grading of the Reflective Writings

35 reflective writings were reviewed, with a range of 2 to 8 writings from each participant. The number of writings was less than the expected minimum number of 6 for some participants because of ‘exemptions’ made for various reasons at certain points in the course of the 3 years of residency. These included periods away on electives or ‘substitution’ with audits, quality improvement projects etc.

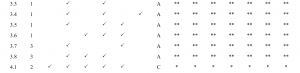

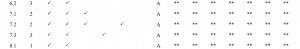

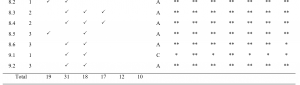

On the grading scale of A to F (Box 2), 30 (86%) of the writings were graded A or B. 4 (11%) were graded C while 1 (3%) was graded D. 13 (81%) of writings done in the first year of residency were graded A or B. For those written in the second and third year of residency, the corresponding numbers were 7 (88%) and 10 (91%) respectively. With only one exception, all writings involved all seven phases of reflection based on the model by Boud et al. (1985). The exceptional piece did not include the phase of ‘association’. The results are described in Table 1.

![]()

Table 1. Tabulation of competencies covered and grading of reflection level in writings

The writings covered all six ACGME competencies. Patient care was discussed in 31 (89%) of the writings. Medical knowledge, professionalism and communications were discussed in 19 (54%), 18 (51%) and 17 (49%) of the writings respectively while system-based practice and problem-based learning and improvement were discussed in 12 (34%) and 10 (29%) of the writings respectively.

C. Thematic Analysis of Interviews

Thematic analysis of the interviews revealed five themes relevant to the research question: (1) effect of the writings in motivating reflections on practice, (2) did the writings facilitate feedback or other learning activities, (3) perceived value of the writings, (4) limitations of the writing programme and (5) possible improvements or alternatives for the writing programme. These are discussed below. The anonymised interview transcripts are available on Figshare (Chan, 2021).

1) Effect of the writings in motivating reflections on practice: All residents conveyed that the main reason they did the writings was because it was a requirement that needed to be fulfilled (Supplementary table 2, A1). All, except one, did the writings just before the six-monthly deadlines (Supplementary Table 2, A2). The one exception usually wrote learning encounter diaries (LEDs) soon after significant events. Though reluctant, most residents were not resentful towards writing as it was deemed not difficult to do and they recognise, to varying extent, some value in doing it (Supplementary Table 2, A3).

Residents described having written on a wide variety of topics. These included reflections about patient care; diagnostic and management dilemmas, ethical issues, communication difficulties, professionalism, safety or inefficiencies in system practices and audit or quality improvement projects. All chose events or encounters that were atypical or non-routine. They used words like ‘special’, ‘interesting’, ‘stand out’, ‘struck my mind’, ‘memorable’, ‘stuck in my mind’ to describe such events or encounters (Supplementary Table 2, A4). Some of these events or encounters affected their emotions and were described as ‘emotionally-tied’, ‘traumatising’ or induced a sense of ‘helplessness’ (Supplementary Table 2, A5).

One was candid in expressing disinterest in the whole exercise (Supplementary Table 2, A6). A few residents felt that the writings involved only recollection of events (Supplementary Table 2, A7). However, most participants believed that the process of writing LEDs promoted additional reflections.

2) Did the writings facilitate feedback or other learning activities: The LEDs were part of the documents reviewed during formal 6-monthly progress review meetings between residents and supervisors. The amount of time spent discussing the contents of the LEDs, as well as residents’ value perception of such discussions varied. However, in general, they were considered of limited value, due to lack of time, supervisors’ disinterest, poor appreciation of or lack of connection with the events. Discussions at a proximate time to the event occurrence and feedback by peers or seniors involved in or familiar with the events or encounters were deemed more useful (Supplementary Table 2, B1).

Apart from reviewing the LEDs with supervisors, there was little that occurred after or as a result of the writings. One remembered that the writings triggered emotions. Another remembered an instance where he was prompted to research and learn more about the topic he wrote about after the writing. It was not common for residents to re-read the LEDs after writing them. In the few instances where this occurred, residents reported that there were some self-evaluation of change and progress in the time elapsed (Supplementary Table 2, B2).

3) Perceived value of the writings: Many residents said reflective writings helped increased self-awareness, recollection, reorganisation and consolidation of thoughts. The writings also served as records for facilitating self-evaluation and references for informing future actions (Supplementary Table 2, C1). A few also spoke about the writing being therapeutic, providing ‘emotional release’ and ‘closure’ to traumatising experiences (Supplementary Table 2, C2).

One resident offered that the LEDs provided him with a good means of communication with his supervisors. As he found it easier to write than to verbally describe, writing the LEDs helped him elicit feedback from his supervisor about the scenarios that he experienced (Supplementary Table 2, C3).

4) Limitations of the writing programme: Several residents pointed out limitations of the writing programme. There may be reluctance to share honestly in the writings for fear of embarrassment or creating a ‘bad impression’. A few felt that reflections can take place without the need for writing. Another opined that reflecting on unpleasant experiences may trigger unwanted emotions (Supplementary Table 2, D1).

5) Possible improvements or alternatives for the writing programme: Residents understood that potential benefits can only be fully realised if reflective writings become ‘routine process’, or ‘habit’ (Supplementary Table 2, E1). Residents also believed that discussions with and feedback from seniors enhance the value of self-reflection in reflective writing or may even replace the need for reflective writings. For such discussions to be useful, they need to occur soon after the events. Sufficient time, interest in participation and trust of confidentiality are also necessary (Supplementary Table 2, E2).

Instead of writing with pen and paper, reflections and discussions on digital platforms; blogging and group discussions online through a portal were suggested by some residents (Supplementary Table 2, E3).

IV. DISCUSSION

In our study, participants demonstrated deep levels of reflection in their writings, despite being reluctant with the task. They wrote on encounters they considered meaningful and covered all of the ACGME competencies. Evidence from the interviews suggested that the writings may not have taken place if they were not mandated. It was also likely that reflections on the topics written about would then not reach similar levels of depth. The percentage of writings with high grades (A and B) for the level of reflection was higher for writings done in year 3 than in year 1 (91% vs 81%) but the numbers were too small for any meaningful comparison to see if reflection depth improved in individuals over the years.

Given the freedom to choose what they write reflections on, our participants reflected most about patient care in their writings. System-based practice and problem-based learning and improvement were covered only in less than a third of the writings. This may reflect differential emphasis that the residents put on the different competencies. At the same time, there is evidence that diagnostic reasoning of complex and unusual cases can be improved by reflection (Mamede & Schmidt, 2017). Our residents may have intuitively recognised this and chose to reflect mainly on diagnostic and management dilemmas in patient care: ‘patients who are a little bit more special, either in terms of their presentations not being the most obvious, or patients who present with a diagnostic or management dilemma.’ (R1), ‘either difficult scenarios I’ve seen or interesting medical scenarios’ (R3). It is possible that our participants wrote less about system-based practice and problem-based learning and improvement because there were many alternative learning activities such as root-cause analysis discussions or participating in quality improvement projects.

The participants reported that the writings resulted in better understanding and increased ability to deal with similar encounters in the future. They also expressed other benefits such as increased self-awareness, facilitation of self-evaluation and having served as a method of coping with emotionally-charged encounters.

We had not provided specific training or detailed instructions on reflective writing for our residents. There was only general guidance that they should review prior experiences in order to learn from them. Nevertheless, our residents did not express difficulty in doing the reflective writings. There were a few possible reasons for this. Firstly, it was likely that the concept of reflective learning had been taught during undergraduate medical education. Secondly, the presence of the three sections with ‘prompt title/questions’: ‘scenario’, ‘what I have learnt from this’ and ‘what would I do differently in future’ provided some guidance. Thirdly, the residents were working in an environment where reflective learning and practice was part of daily practice and likely learned aspects of these in the process; they participated in root-cause analyses for incidents of medical error or adverse events and attended courses that teach clinical practice improvement methodology.

Reflective writing involves mainly self-reflection after an event. Learning is limited if the written self-reflection is not accompanied by discussion and feedback from peers or mentors (Sandars, 2009). Our study found that there was little guidance from supervisors on reflective techniques and limited feedback for the content of reflective writings. Several reasons emerged. Time was limited during scheduled supervisor-resident meetings and the reflective writings were only part of several documents reviewed by the supervisors. Supervisors were generally not involved in the events described and unfamiliar with the situational contexts. Residents’ interest in feedback on the events had also declined due to the lapse of time since the occurrences.

Literature shows that self-assessment is often inaccurate (Eva & Regehr, 2008). Feedback from others can provide multiple perspectives on experience, support integration of affective and cognitive experience and discourage uncritical acceptance of experience. Feedback from supervisors is not limited to the content of a reflection but should include the resident’s reflective skills as well. There had not been emphasis placed on teaching reflective techniques to residents. Supervisors can point out assumptions in the reflections, offer alternative interpretations and ask for clarifications of reasoning, omissions and conclusions. Faculty training for supervisors would be necessary to enable them to do these well.

Other limiting factors were discussed during the interviews. One participant expressed a reluctance to write honestly about incidents that showed one’s deficiencies for fear of giving a ‘bad impression’. This may reflect the resident’s goal orientation towards performance rather than mastery, the lack of a formative learning environment or inadequate trust towards a supervisor. Another participant pointed out the potential for reflection on events to trigger unwanted emotions. This highlighted the need for establishing in advance a plan for appropriate actions to ensure privacy and support for distressed residents.

A. Limitations of this Study

Our study described the outcomes from a programme of reflective writings in one institution. Differences in contextual factors may limit the transferability of our experience to settings elsewhere. Voluntary participation in this study may have resulted in a small, self-selected group of participants with strong opinions towards reflective writings. With graduates of the residency as participants, obtained opinions were based on memories that may have been altered by time and circumstances. Even though the writings were not included for any summative assessments, some participants may not have written accurate accounts of their thoughts and emotions due to concerns of creating a ‘bad impression’.

V. CONCLUSION

Our study found that a programme of reflective writings promoted deep reflection, with participants focusing especially on self-reflection to enhance their diagnostic and management skills in patient care. In general, the writings led to increased understanding, self-awareness and ability to deal with similar future situations. It also facilitated self-evaluation and emotional regulation. The important role of supervisor guidance and feedback in enhancing reflective learning was recognised. Providing this would require investment in faculty training, time resources and commitment of supervisors.

Notes on Contributors

YCC reviewed the literature, designed the study, conducted interviews, analysed interview transcripts and wrote the manuscript. CHT analysed and graded the reflective writings, analysed interview transcripts and developed the manuscript. JD advised on the design of the study and developed the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (NHG DSRB) (Reference number: 2017/01219).

Data Availability

The anonymised interview transcripts are available on Figshare (Chan, 2021). To protect the confidentiality of the participants, the reflective writings cannot be shared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Jocelyn Chan and Ms Alicia Chan for their assistance in transcribing the interviews.

Funding

No funding was received for this research study.

Declaration of Interest

YCC is a core faculty member of the Internal Medicine Residency Programme. To reduce possible bias or conflicts related to confidentiality and power relationships, grading of reflective writings was done by CHT, who is not a faculty member of the programme. There are no other conflicts of interest.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (2013, April 24). Implementing milestones and clinical competency committees. Retrieved December 16, 2016, from http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/ACGMEMilestones-CCC-AssesmentWebinar.pdf

Aronson, L. (2011). Twelve tips for teaching reflection at all levels of medical education. Medical Teacher, 33(3), 200-205. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.507714

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. Kogan Page.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chan, Y. C. (2021). Impact of Reflective Writings data [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14069369.v1

Epner, D. E., & Baile, W. F. (2014). Difficult conversations: Teaching medical oncology trainees communication skills one hour at a time. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 578-584. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000177

Eva, K. W., & Regehr, G. (2008). “I’ll never play professional football” and other fallacies of self-assessment. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 28(1), 14-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.150

Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., Cate, O. T., Holmboe, E. S., Carraccio, C., Swing, S. R., Harris, P., Glasgow, N. J., Campbell, C., Dath, D., Harden, R. M., Iobst, W., Long, D. M., Mungroo, R., Richardson, D. L., Sherbino, J., Silver, I., Taber, S., Talbot, M., & Harris, K. A. (2010). Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 638–645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning. Prentice-Hall.

Leung, D. Y. P., & Kember, D. (2003). The relationship between approaches to learning and reflection upon practice. Educational Psychology, 23(1), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410303221

Levine, R. B., Kern, D. E., & Wright, S. M. (2008). The impact of prompted narrative writing during internship on reflective practice: A qualitative study. Advanced Health Science Education Theory Practice, 13(5),723-733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9079-x

Mamede, S., & Schmidt, H. G. (2017). Reflection in Medical Diagnosis: A Literature Review. Health Professions Education, 3(1), 15-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2017.01.003

Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advanced Health Science Education Theory Practice, 14(4), 595-621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. Jossey-Bass.

Moon, J. A. (2004). A handbook of reflective and experiential learning: Theory and practice. Routledge Falmer.

Nguyen, Q. D., Fernandez, N., Karsenti, T., & Charlin, B. (2014). What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Medical Education, 48(12), 1176-1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12583

Sandars, J. (2009). The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Medical Teacher, 31(8), 685-95. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903050374

Tsingos, C., Bosnic-Anticevich, S., Lonie, J. M., & Smith, L. (2015). A Model for Assessing Reflective Practices in Pharmacy Education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 79(8), 124. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe798124

Winkel, A. F., Hermann, N., Graham, M. J., & Ratan, R. B. (2010). No time to think: Making room for reflection in obstetrics and gynecology residency. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 2(4), 610-615. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-10-00019.1

Winkel, A. F., Yingling, S., Jones, A. A., & Nicholson, J. (2017). Reflection as a Learning Tool in Graduate Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(4), 430-439. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

*Chan Yee Cheun

1E Kent Ridge Road

NUHS Tower Block, Level 10

Singapore 119228

Tel: +65 67795555

Email: yee_cheun_chan@nuhs.edu.sg

Announcements

- Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.