Impact of a longitudinal student-initiated home visit programme on interprofessional education

Submitted: 22 September 2021

Accepted: 27 April 2022

Published online: 4 October, TAPS 2022, 7(4), 1-21

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-4/OA2785

Yao Chi Gloria Leung1*, Kennedy Yao Yi Ng2*, Ka Shing Yow3*, Nerice Heng Wen Ngiam4, Dillon Guo Dong Yeo4, Angeline Jie-Yin Tey5, Melanie Si Rui Lim6, Aaron Kai Wen Tang7, Bi Hui Chew8, Celine Tham9, Jia Qi Yeo10, Tang Ching Lau11,12, Sweet Fun Wong13,14, Gerald Choon-Huat Koh15,16** & Chek Hooi Wong14,17**

1Department of Anaesthesiology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 2Department of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore; 3Department of General Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 4Department of General Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 5Department of General Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; 6Department of General Paediatrics, Kandang Kerbau Hospital, Singapore, 7Department of Psychiatry, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 8Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; 9Ng Teng Fong General Hospital, Singapore, 10National Healthcare Group Pharmacy, Singapore, 11Department of Medicine, NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Singapore; 12Division of Rheumatology, University Medicine Cluster, National University Hospital, Singapore; 13Medical Board and Population Health & Community Transformation, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore; 14Department of Geriatrics, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore; 15Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 16Future Primary Care, Ministry of Health Office of Healthcare Transformation, Singapore; 17Health Services and Systems Research, Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, Singapore

*Co-first authors

**Co-last authors

Abstract

Introduction: Tri-Generational HomeCare (TriGen) is a student-initiated home visit programme for patients with a key focus on undergraduate interprofessional education (IPE). We sought to validate the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) and evaluate TriGen’s efficacy by investigating healthcare undergraduates’ attitude towards IPE.

Methods: Teams of healthcare undergraduates performed home visits for patients fortnightly over six months, trained by professionals from a regional hospital and a social service organisation. The RIPLS was validated using exploratory factor analysis. Evaluation of TriGen’s efficacy was performed via the administration of the RIPLS pre- and post-intervention, analysis of qualitative survey results and thematic analysis of written feedback.

Results: 79.6% of 226 undergraduate participants from 2015-2018 were enrolled. Exploratory factor analysis revealed four factors accounting for 64.9% of total variance. One item loaded poorly and was removed. There was no difference in pre- and post-intervention RIPLS total and subscale scores. 91.6% of respondents agreed they better appreciated the importance of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) in patient care, and 72.8% said MDMs were important for their learning. Thematic analysis revealed takeaways including learning from and teaching one another, understanding one’s own and other healthcare professionals’ role, teamwork, and meeting undergraduates from different faculties.

Conclusion: We validated the RIPLS in Singapore and demonstrated the feasibility of an interprofessional, student-initiated home visit programme. While there was no change in RIPLS scores, the qualitative feedback suggests that there are participant-perceived benefits for IPE after undergoing this programme, even with the perceived barriers to IPE. Future programmes can work on addressing these barriers to IPE.

Keywords: Interprofessional Education, Student-Initiated Home Visit Programme, RIPLS, Validation

Practice Highlights

- We validated the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) in Singapore, a multi-ethnic Asian country.

- A student-initiated, interprofessional, longitudinal home visit program is feasible.

- While there was no significant change in RIPLS scores, participants reported qualitative benefits of the programme in their attitudes towards IPE.

- Qualitative feedback highlighted four main barriers to IPE: Time constraints, unmotivated teammates, administrative burden, and unsuitable patients.

I. INTRODUCTION

Interprofessional education (IPE) aims to prepare healthcare professionals for effective collaboration, and while becoming increasingly common, is challenging to initiate, implement, evaluate and sustain (Fahs et al., 2017). Key challenges include designing a curriculum that integrates IPE with traditional academic frameworks, active engagement of facilitators and students, and accommodating various professions (Sunguya et al., 2014). IPE is context-specific, evolving, and involves continuous interaction and interdependence, and many traditional top-down approaches such as forums and lectures do not effectively teach it (Briggs & McElhaney, 2015).

Experiential IPE programmes employ a ground-up approach and potentially tackle some of the aforementioned challenges. Students involved in on-the-ground interprofessional healthcare visits to older adults showed that such experiences improved student collaboration and students’ self-perception of interprofessional team care-related skills (Blythe & Spiring, 2020; Conti et al., 2016; McManus et al., 2017; Toth-Pal et al., 2020; Vaughn et al., 2014). Therefore, a group of undergraduates from the National University of Singapore (NUS) Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine initiated an experiential student-led IPE programme which is aimed at improving health outcomes in older people with frequent hospital readmissions. This longitudinal service-learning programme was anchored by several educational aims including enhancing students’ IPE outcomes and improving attitudes towards IPE.

Formal evaluation of such programmes and investigating student IPE attitudes after being involved in a longitudinal home visit programmes are lacking in the current IPE literature (Grice et al., 2018). This study aims to evaluate TriGen’s effectiveness by investigating student IPE attitudes through the use of the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS). Since the RIPLS has not been validated in the Singapore context, this study also aims to validate this scale.

II. METHODS

A. Programme Design

TriGen is a collaboration between NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, a Northern regional hospital in Singapore, and North West Community Development Council, a grassroots organisation (Ng et al., 2020a, 2020b). A non-profit ground-up social initiative by healthcare undergraduates, it has the dual aim of i) serving the medical and social needs of older patients by providing longitudinal home visits by interprofessional student teams; ii) educating and empowering undergraduate students through a service-learning approach, with a key focus on improving attitudes towards IPE. The programme was designed under the mentorship of university faculty members, and was earmarked as a co-curricular activity aimed at improving students’ attitudes towards IPE and IPC. Older patients with frequent hospital readmissions (three or more times over six months) were followed up by healthcare undergraduates enrolled in Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Social Work, Physiotherapy or Occupational Therapy courses in Singapore.

The programme begins with healthcare undergraduates undergoing didactic, skill-based training and team-based simulation training covering possible scenarios encountered during home visits (Annex 1). Each team comprising 2-3 interdisciplinary undergraduates conduct fortnightly visits to 1-2 patients over 6 months. At the midpoint and endpoint of the programme, healthcare undergraduates assessed the patients’ needs and presented at multi-disciplinary meetings (MDMs) chaired by healthcare professionals and grassroots staff, who guided the undergraduates to execute a management plan.

This IPE programme was designed based on educational principles for adult learners outlined by Knowles (1984). First, it provided healthcare undergraduates with opportunities for experiential learning anchored in the service-learning approach. Second, it was largely problem-based group learning with most training sessions being team-based and scenario-based. MDMs were also problem-based and encouraged undergraduates to brainstorm ideas to address their patients’ issues. Third, the service they provided in this programme modelled the work they may engage in after graduation. What they learned in this programme was of immediate relevance to their current study and future practice. Lastly, the programme provided autonomy to healthcare undergraduates to direct their own learning. This programme was voluntary and allowed participants’ flexibility for further self-study of topics of interest. Key student outcomes include readiness for IPE (including teamwork and collaboration, professional identity, roles and responsibility), and a better appreciation for IPC.

B. Evaluation Approach

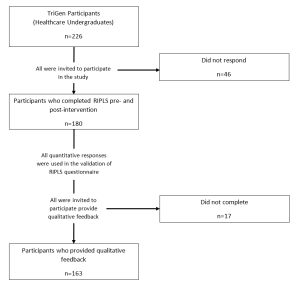

This study used the framework by Kirkpatrick (1959) expanded by Barr et al. (2005) to evaluate the effectiveness of TriGen in improving healthcare undergraduates’ attitudes towards IPE, particularly in evaluation levels 1, 2a and 2b, which centre on learner’s reactions, attitude perceptions, and acquisition of knowledge or skills (Table 1). The use of quantitative and qualitative data collection in a survey was thought to be most appropriate in capturing the data and making the evaluation richer, and was hence the approach utilised for this research (Figure 1).

|

Evaluation Level |

Methods and Measures |

Timeframe |

|

Level 1: Learners’ reactions Participants’ views of their learning experience and opinions about the program |

Participants’ self-reported feedback of IPE learning |

Post-intervention |

|

Qualitative feedback |

Post-intervention |

|

|

Level 2a: Modification of attitudes perceptions |

Participants’ self-reported feedback of IPE learning |

Post-intervention |

|

Qualitative feedback |

Post-intervention |

|

|

|

Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale |

Pre- and post-intervention |

|

Level 2b: Acquisition of knowledge/skills Concepts, procedures, principles, and skills |

Qualitative feedback |

Post-intervention |

Table 1: Components of Kirkpatrick/Barr et al. evaluation framework as applied to TriGen

Figure 1: Flowchart of study components

C. Quantitative Measures

The RIPLS (Parsell & Bligh, 1999) was among the first scales developed for measurement of attitudes towards interprofessional learning. It assesses student readiness for IPE and IPC with other health care professionals and has been reported to be sensitive to differences in the students’ attitude towards IPE (Berger-Estilita et al., 2020). While there are a few studies validating it in Asian countries (China, Indonesia, Japan), none have been performed in Singapore (a multi-ethnic Asian country with English language as a predominant language of instruction (Ganotice & Chan, 2018; Lestari et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Tamura et al., 2012).

The RIPLS, a 19-item questionnaire comprising 4 subscales (“Teamwork and Collaboration”; “Positive Professional Identity”; “Negative Professional Identity” and “Roles and Responsibilities”), was administered pre- and post-intervention (McFadyen et al., 2005). Higher RIPLS scores imply greater readiness for interprofessional learning. This study validates the RIPLS in the Singapore context for the first time, then employs it for quantitative evaluation of TriGen. Additionally, separate from the RIPLS, three questions were added as a direct measure of participants’ reaction (Level 1), “I better appreciate the importance of IPC in the care of patients through the programme”, “The multidisciplinary meetings organised were important for my learning”, and “I would recommend the programme to my friends.”

1) Statistical Analysis: The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess if the data followed a normal distribution (Shapiro & Wilk, 1965). Factor analysis was conducted to explore the construct validity of the RIPLS, and Cronbach’s alpha was computed to determine internal consistency. The suitability of the correlation matrix was determined by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The numbers of factors retained for the initial solutions and entered into the rotation were determined with the application of Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalues >1). The initial factor extraction was performed using principal component analysis. Exploratory factor analysis was then conducted based on the RIPLS four-subscale structure. A paired t-test comparing baseline and post-intervention responses was computed for each survey item to determine significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). One-way ANOVA was performed to assess for demographic factors that correlated with pre-intervention and magnitude of change in RIPLS scores; if it demonstrated an overall difference between groups, post-hoc Tukey’s HSD was performed. For all statistical analyses, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 23.0, Chicago, Illinois) was used.

D. Qualitative Measures

Post-intervention qualitative feedback regarding participants’ learning experiences was collected through online surveys. Questions include: What did you learn about interprofessional collaboration? What are your learning points after completing the project? Would you recommend this project to your peers, and what are your reasons? These questions were chosen to better understand participants’ reaction to the programme, their attitudes toward IPE and IPC, and other key learning points they may have.

1) Thematic Analysis: All survey participants were encouraged to participate in the qualitative research, with a total of 163 recruited to give written qualitative feedback on the programme. Given the relatively large sample of data, thematic analysis was chosen to explore and interpret the dataset, distilling it into recurring ideas (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Kiger & Varpio, 2020). Analysis was performed on participants’ qualitative descriptions of their learning experiences, with constant comparison analysis used to identify patterns in participants’ responses and develop a coding schema. Two coders independently identified major themes from the text within all transcripts, with reference to the research questions. They discussed and resolved any disagreements. No member checking was performed. A common coding schema was generated and applied to all the transcripts.

E. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the NUS institutional review board (B-15-272). Study participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was taken from participants before data collection commenced, and they were allowed to withdraw from the research at any point in time. No incentives were provided to study participants.

III. RESULTS

226 healthcare undergraduates participated in TriGen from 2015-2018. Response rate for the RIPLS was 79.6%.

A. Demographics

Median age was 21 (range 18-41). 62.2% of participants were female, 37.8% were male. 31.7% were medical students, 12.8% nursing students, 42.2% pharmacy students, 10.0% social work students, and 3.3% therapy students. First- and second-year students comprised 62.2% of participants, while third- to fifth-years comprised 37.8%. 65.0% participated in previous IPE activities.

B. Construct Validity

The KMO index was 0.902, indicating sampling adequacy. The chi-square index for Barlett’s test of sphericity was 1919.445 (df171, p<0.001), indicating suitability for factor analysis.

Principal component analysis yielded four components largely consistent with the four-subscale model of the RIPLS (Barr et al., 2005) (Annex 2). However, one item, “I am not sure what my professional role will be”, had a low loading value of 0.285 under the original subscale of “Roles and Responsibility” and a borderline low loading value of 0.459 under the subscale of “Negative Professional Identity”. It was removed from subsequent analyses in view of its poor fit into the theoretical construct (Table 2).

|

No |

Statements |

Teamwork and Collaboration |

Negative Professional Identity |

Positive Professional Identity |

Roles and Responsibilities |

|

1 |

Shared learning will help me to think positively about other healthcare professionals. |

0.794 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

Learning with other health and social care students before qualification would improve relationships after qualification. |

0.781 |

|

|

|

|

3 |

Team-working skills are essential for all health and social care students to learn. |

0.773 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

Shared learning will help me to understand my own limitations. |

0.767 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

Communication skills should be learnt with other health and social care students. |

0.746 |

|

|

|

|

6 |

Learning with other students/professionals will make me become a more effective member of a health and social care team. |

0.742 |

|

|

|

|

7 |

For small group learning to work, students need to trust and respect each other. |

0.739 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

Shared learning with other healthcare students will increase my ability to understand clinical problems. |

0.723 |

|

|

|

|

9 |

Patients would ultimately benefit if health and social care students/professionals worked together to solve patient problems. |

0.650 |

|

|

|

|

10 |

It is not necessary for undergraduate health and social care students to learn together. |

|

0.882 |

|

|

|

11 |

I don’t want to waste time learning with other health and social care students. |

|

0.854 |

|

|

|

12 |

Clinical problem-solving skills can only be learnt with students from my own department. |

|

0.799 |

|

|

|

13 |

Shared learning will help to clarify the nature of patient problems. |

|

|

0.658 |

|

|

14 |

Shared learning before qualification will help me become a better team worker. |

|

|

0.642 |

|

|

15 |

I would welcome the opportunity to work on small group projects with other health and social care students. |

|

|

0.614 |

|

|

16 |

Shared learning with other health and social care professionals will help me to communicate better with patients and other healthcare professionals. |

|

|

0.567 |

|

|

17 |

The function of nurses and therapists is mainly to provide support for doctors. |

|

|

|

0.836 |

|

18 |

I am not sure what my professional role will be. |

|

0.459* |

|

0.285 |

|

19 |

I have to acquire much more knowledge and skills than other health or social care students. |

|

|

|

0.517 |

Table 2: Exploratory Factor Analysis of the RIPLS – Contribution of Items to Each Component

*The highest loading value of each item under the four subscales are shown (except for item 18). A loading value of >0.5 was taken to be satisfactory. Item 18, “I am not sure what my professional role will be.”, was deemed borderline satisfactory at a loading value of 0.459 in the subscale Negative Professional Identity. Its loading value was lower at 0.285 in its original subscale Roles and Responsibility.

C. Internal Consistency

Cronbach’s alpha is 0.848 for RIPLS total score, suggesting good internal consistency.

D. Baseline RIPLS Score

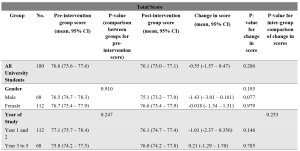

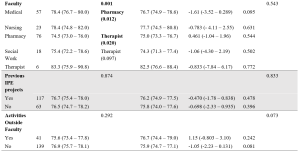

Table 3: Total RIPLS scores.

Subscale scores can be found in Annexes 3 to 6.

The mean baseline total RIPLS score was 76.6 (95% CI 75.6 – 77.6). There was a baseline difference between faculties (p=0.001), with medical and therapy undergraduates having higher scores as compared to pharmacy students (mean difference 3.85, 0.59–7.11, p=0.012 and mean difference 8.83, 0.94–16.7, p=0.020, respectively) (Table 3). As for subscales, there was a difference in “Teamwork and Collaboration” baseline scores between years of study, with Year 1–2 undergraduates had a higher baseline score of 40.8 (40.0–41.5) versus Year 3–5 undergraduates with a score of 39.5 (38.6–40.4) (p=0.038) (Annex 3). Medical undergraduates had higher baseline scores for the “Teamwork and Collaboration” 41.2 (40.2–42.2)) and “Positive Professional Identity” 17.9 (17.4–18.5) subscales compared to pharmacy undergraduates 39.3 (38.4–40.1) (p=0.034), and 17.0 (16.6–17.4) (p=0.036) respectively (Annexes 3-4). Social work undergraduates have the lowest baseline “Roles and Responsibility” score, averaging 4.94 (4.34–5.55) compared to all other faculties (Annex 6).

E. Change in RIPLS Score Post-Intervention

There was no significant difference between the pre- and post-intervention RIPLS total score and the subscale score under the “Teamwork and Collaboration” subscale (Table 3, Annex 3). Under the “Positive Professional Identity” subscale, there was a decrease in post-intervention scores of Year 1-2 students (mean difference -0.500 (-0.931– -0.069), p=0.023) and students with no participation in activities outside of the faculty (mean difference -0.403 (-0.768 – -0.037), p=0.031) (Annex 4). Under the “Negative Professional Identity” subscale, there was a decrease in post-intervention score in medical students (mean difference -0.667 (-1.31– – 0.020), p=0.44) and social work students (-0.889 (-1.70– -0.073), p=0.035) (Annex 5). There was an increase in the post-intervention score amongst female students under the “Roles and Responsibility” subscale (mean difference 0.384 (0.065–0.703), p=0.019) (Annex 6).

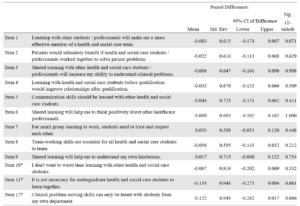

F. Individual Item Analysis

Negatively coded statements like “the function of nurses and therapists is mainly to provide support for doctors” (Item 17) and “I am not sure what my professional role will be” (Item 18) showed significant increases in scores post-intervention (0.23, p=0.005 and 0.17, p=0.016 respectively). Other significant findings include a decrease in scores for the statements “Shared learning with other health and social care professionals will help me to communicate better with patients and other healthcare professionals” (Item 13) (-0.14, p=0.013), and “Shared learning will help to clarify the nature of patient problems (Item 15) (-0.10, p=0.034) (Table 4).

Table 4: RIPLS (Individual items analysis)

G. Self-Reported Feedback on Interprofessional Learning

91.6% participants agreed they could “better appreciate the importance of interprofessional collaboration in the care of patients”. 72.8% said MDMs were important for their learning and 91.9% of respondents would recommend the programme to their friends.

H. Qualitative Feedback

163 of 180 survey respondents participated in the qualitative research (response rate 90.6%). (Fig 1) 34.4% of respondents were male and 65.6% female. 33.1% of respondents were studying Medicine, 12.3% Nursing, 40.5% Pharmacy, 11.0% Social Work and 3.1% Therapy. 54.6% of respondents were in early years of study (Year 1–2). 74.8% had previous exposure to IPE. Thematic analysis yielded the following themes:

1) Learning and teaching one another: Healthcare undergraduates found value in learning from one another. They shared knowledge and skills gained from their respective curriculum with one another.

“I feel more equipped and prepared to teach and learn from other healthcare professionals”

21-year-old female third-year medical student

“I learnt a lot from my social work team leader and how to consider the social aspects of issues the elderly face”

20-year-old male first-year medical student

2) Understanding the role of other healthcare professionals: Healthcare undergraduates learned the role of other healthcare professionals and gained new insights into how different healthcare professionals contributed to the care of the patient.

[I have] learn[ed] … how we can tap on each other[’s] strengths to come up with a care plan for the patients

21-year-old female third-year pharmacy student

Understanding what medicine, nursing [and] pharmacy does make quite a lot of difference to how we perceive and thus, work with them.

23-year-old female second-year social work student

3) Understanding one’s own role: Healthcare undergraduates reported developing a greater understanding of the roles and responsibilities they played as a part of a multi-disciplinary team.

I am now more aware of the role and responsibility I have as a healthcare professional.

21-year-old female first-year pharmacy student

Working in a multi-disciplinary team gave me a feel of how it may be like caring for a patient as a team in my future career.

20-year-old female first-year social work student

4) Teamwork: Healthcare undergraduates appreciated the need for collaboration and teamwork within a multi-disciplinary team. They learned about the importance of compromise.

Working with different people, in terms of personality, faculty, etcetera – I learnt to give and take and be more understanding towards the others.

21-year-old second-year social work student

It has allowed me to better understand … how the different professions can come together to better serve the needs of patients.

20-year-old female second-year pharmacy student

5) Opportunity to meet people from other faculties: Healthcare undergraduates valued meeting people from other faculties and developing collaborative relationships they would otherwise not have had the opportunity to.

I got to know seniors in medicine and peers from pharmacy.

20-year-old female first-year nursing student

It is a very unique experience, having the chance to interact with … other university students from different healthcare faculties.

20-year-old female second-year pharmacy student

6) Factors limiting learning: Factors limiting learning included time constraints, unmotivated teammates, administrative burden and lack of suitable patients. For the latter, some undergraduates felt that their care was restricted to companionship for patients who were already able to manage their own chronic conditions well and did not require further help from the healthcare undergraduates.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Validation of the RIPLS in Singapore

This study validated the RIPLS in the Singapore context. The final model is the same as proposed by McFadyen et al. (2005). without item 18 “I am not sure what my professional role will be”, from “Roles and Responsibility” subscale. The poor fit of this item into this study’s theoretical construct could be because participants are mostly in their pre-clinical years and may not understand professional roles and responsibilities due to their limited on-job experience, a reason also proposed by McFadyen et al. (2005) and Tyastuti et al. (2014). Tyastuti et al. (2014) found this item, along with “I have to acquire much more knowledge and skills than other healthcare students” (item 19) from the same subscale had loading factors of <0.5 and removed the entire “Roles and Responsibility” subscale from the Indonesian version of the RIPLS. Other studies validating the RIPLS also experienced issues with this subscale (Lauffs et al., 2008; Lestari et al., 2016; McFadyen et al., 2005).

B. Baseline RIPLS score

The mean baseline RIPLS score is comparable with that by Chua et al. (2015), another study conducted in Singapore which measured change in the RIPLS after a one-day IPE conference. They also found higher baseline RIPLS scores for medical undergraduates versus other faculties, a finding also noted in this study and another done in a culturally similar country (Lestari et al., 2016). However, this finding seems inconsistent as other studies (Aziz et al., 2011; de Oliveira et al., 2018) have found the contrary.

Chua et al. (2015) also found that prior IPE experience resulted in higher baseline RIPLS scores, a finding not replicated in this study. We hypothesise that while 65.0% of this study’s participants had previous IPE exposure (versus 10.6% in Chua et al. (2015)), the heterogenous nature of IPE programmes they previously participated in may have had differing efficacy in improving IPE attitudes.

This study found undergraduates in their later years had a lower baseline “Teamwork and Collaboration” subscale score, versus those in their early years. We postulate that undergraduates with more clinical experience better understand the challenges of IPE in practice, a finding echoed by Judge et al. (2015).

That pharmacy students, but not medical students, were mandated by their curriculum to fulfil volunteering hours which could explain the former’s lower baseline scores for total RIPLS and subscales “Teamwork and Collaboration” and “Positive Professional Identity” since they are likely less motivated by IPE when choosing to participate.

Social work undergraduates’ low baseline “Roles and Responsibility” score likely reflects their minimal exposure to medical social work unless they elected for healthcare modules in their senior years of study.

C. Change in Pre- and Post-intervention RIPLS Scores

Our study did not show a significant difference between the pre- and post-intervention RIPLS total score and the “Teamwork and Collaboration” subscale. Additionally, there was a decrease seen in post-intervention scores under the “Positive Professional Identity” subscale for Year 1-2 students and the “Negative Professional Identity” subscale in medical students and social work students. This is in contrast with the literature, where previous studies involving conferences (Chua et al., 2015) or solitary learning modules (Wakely et al., 2013; Zaudke et al., 2016) demonstrated a significant difference in the total RIPLS score pre- and post- intervention. Possible reasons for this are further discussed in section E.

There was a significant increase in the post-intervention score amongst female students under the “Roles and Responsibility” subscale. Previous studies have suggested that there are gender specific differences in perception towards IPE with female students having a more positive attitude towards IPE (Hansson et al., 2010; Wilhelmsson et al., 2011). In addition, the individual item analysis showed that negatively coded statements relating to the subscale of “Roles and Responsibility” such as “the function of nurses and therapists is mainly to provide support for doctors” (Item 17) and “I am not sure what my professional role will be” (Item 18) had significant increases in scores post-intervention. This is encouraging and demonstrates the success of the programme in helping students understand the respective roles and responsibility of each profession which is a crucial part of IPE and eventually IPC.

Other significant findings in the individual item analysis include a decrease in scores for the statements “Shared learning with other health and social care professionals will help me to communicate better with patients and other healthcare professionals” (Item 13), and “Shared learning will help to clarify the nature of patient problems” (Item 15). These findings suggest that the programme can be improved by incorporating more modules on communication between healthcare professionals and shared problem-solving.

D. Qualitative Feedback

While the lack of a significant difference between the pre- and post-intervention RIPLS scores suggest no changes in attitudes, the qualitative data revealed that the majority of undergraduates better appreciated the importance of IPC for patient care and many felt that that MDMs were useful for their learning.

Qualitative analysis revealed five major themes in the undergraduates’ learning pertaining to IPE. Participants learned from and taught each other. Being able to freely learn from and teach one another requires mutual trust and respect which are key elements of collaborative practices (de Oliveira et al., 2018). Participants reported better understanding of their own and other healthcare professionals’ roles; these are recognised as crucial components of collaborative practice (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative, 2010). Undergraduates also shared that they learned about teamwork, specifically, conflict resolution and compromise. Finally, undergraduates appreciated the opportunities to meet fellow undergraduates from different faculties. It has been observed in many successful IPE programmes that informal social interactions are potentially as important as the actual IPE activities (Lie et al., 2016). We observed that the relationships built between participants of the programme often persisted beyond the completion of the programme; these relationships could benefit the institution and healthcare system (Hoffman et al., 2008).

E. Possible Reasons Underlying Lack of Improvement in RIPLS Scores

First, as mentioned earlier, the RIPLS has been described to have psychometrics issues, with multiple researchers modifying the subscales (Mahler et al., 2015). Second, Schmitz and Brandt (2015) suggested that RIPLS is insensitive to course improvements and to pre- versus post-intervention change in attitudes. We chose the RIPLS at the start of 2014 as it had been widely used and validated and simple to administer, and we also sought to validate it in Singapore for the first time. Unfortunately, few studies on its potential issues had been published at the time to inform the design of this study. Third, the longitudinal nature of the programme may have permitted undergraduates greater insight to the challenges of IPE and realities of collaborating within interprofessional teams, tampering their idealism.

Lestari et al. (2016) described how nursing and midwifery undergraduates had lower RIPLS scores as compared to medical and dentistry undergraduates as they had prior clinical experience and likely observed less than exemplary interactions amongst members of healthcare teams. Similarly, Makino et al. (2013) found that graduates of an IPE programme had a lower mean score on the Modified Attitudes Toward Health Care Teams Scale (ATHCTS) as compared to current students. The authors suggested that the alumni’s negative attitude may be due to their real-world experience. Several structural issues in clinical practice have been identified that contribute to this trend, for example competition between professionals (Tremblay et al., 2010) and power struggles (Paradis & Whitehead, 2015).

F. Barriers to IPE

Undergraduates reported four main barriers: time constraints, unmotivated teammates, administrative burden, unsuitable patients. Other studies including Alexandraki et al. (2017) and West et al. (2016) have also faced time constraints. As this programme is voluntary, undergraduates had to take time off their already packed curriculum to participate, and the selection of volunteers was not a stringent process. Additionally, as participants were contributing to clinical care, documentation of visits is required. Multiple studies showed that physicians deemed documentation and administrative work burdensome and excessive time spent on these may be associated with physicians’ burnout (Patel et al., 2018; Wright & Katz, 2018).

In addressing these barriers, incorporating academic credits for participation, a more stringent selection of participants, streamlining administrative work and prudent choice of patients may be considered. These measures are already being implemented by the programme organisers to improve the programme.

G. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study lies in the use of both quantitative and qualitative data grounded on an established framework by Kirkpatrick (1959) for the evaluation of a novel experiential IPE programme. The limitations of our study include it being single-institution and that the participants are volunteers which thus form a self-selected group. Hence, the results may not be generalisable. There was also no control arm for the intervention. In addition, there was a large variation in baseline RIPLS score seen in the programme, which can be potentially improved with a more robust study design that controls for baseline differences. Lastly, the use of only a survey for data collection may limit the depth of qualitative data obtained. Further studies could include qualitative interviews.

V. CONCLUSION

We validated the RIPLS in Singapore and demonstrated the feasibility of an interprofessional student-initiated home visit programme. While there was no significant change in RIPLS scores, the qualitative feedback suggests that there are participant-perceived benefits for IPE after undergoing this programme, even with the perceived barriers to IPE. Future programmes can work on addressing these barriers to IPE.

Notes on Contributors

Gloria Yao Chi Leung contributed to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Kennedy Yao Yi Ng contributed to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Yow Ka Shing contributed to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition and interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Nerice Heng Wen Ngiam contributed to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition of data for the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Dillon Guo Dong Yeo contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Angeline Jie-Yin Tey contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Melanie Si Rui Lim contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Aaron Kai Wen Tang contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Chew Bi Hui contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Celine Yi Xin Tham contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Yeo Jia Qi contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Lau Tang Ching contributed to the conception and design of the work, critical revision of the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Wong Sweet Fun contributed to the conception and design of the work, critical revision of the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Gerald Choon Huat Koh contributed to the conception and design of the work, interpretation of the data for the work, critical revision of the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Wong Chek Hooi contributed to the conception and design of the work, interpretation of the data for the work, critical revision of the manuscript, approves of the publishing of the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the NUS institutional review board (B-15-272). Study participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was taken from participants before data collection commenced, and they were allowed to withdraw from the research at any point in time. No incentives were provided to study participants.

Data Availability

According to institutional policy, research dataset is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Tri-Generational HomeCare Organising Committee from 2014 to 2018 for supporting the study. They would like to extend their thanks to the National University of Singapore, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Dean’s Office; the North West Community Development Council; Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore; Geriatric Education and Research Institute, Singapore. Finally, they would like to thank the volunteers for their generosity and the patients for their hospitality.

Funding

National University of Singapore, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Dean’s Office; the North West Community Development Council; Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore provided funding support for the purchase of medical consumables, refreshments and logistics for the program.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

Alexandraki, I., Hernandez, C. A., Torre, D. M., & Chretien, K. C. (2017). Interprofessional education in the internal medicine clerkship post-LCME standard issuance: Results of a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(8), 871–876.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4004-3

Aziz, Z., Teck, L. C., & Yen, P. Y. (2011). The attitudes of medical, nursing and pharmacy students to inter-professional learning. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 29, 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.287

Barr, H., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., Hammick, M., & Freeth, D. (2005). Effective interprofessional education: argument, assumption, and evidence (1st edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

Berger-Estilita, J., Fuchs, A., Hahn, M., Chiang, H., & Greif, R. (2020). Attitudes towards interprofessional education in the medical curriculum: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), Article 254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02176-4

Blythe, J., & Spiring, R. (2020). The virtual home visit. Education for Primary Care, 31(4), 244–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1772119

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briggs, M. C. E., & McElhaney, J. E. (2015). Frailty and interprofessional collaboration. Interdisciplinary Topics in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 41, 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381204

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010). A national interprofessional competency framework. https://phabc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CIHC-National-Interprofessional-Competency-Framework.pdf

Chua, A. Z., Lo, D. Y., Ho, W. H., Koh, Y. Q., Lim, D. S., Tam, J. K., Liaw, S. Y., & Koh, G. C. (2015). The effectiveness of a shared conference experience in improving undergraduate medical and nursing students’ attitudes towards inter-professional education in an Asian country: A before and after study. BMC Medical Education, 15, Article 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0509-9

Conti, G., Bowers, C., O’Connell, M. B., Bruer, S., Bugdalski-Stutrud, C., Smith, G., Bickes, J., & Mendez, J. (2016). Examining the effects of an experiential interprofessional education activity with older adults. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(2), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1092428

de Oliveira, V. F., Bittencourt, M. F., Navarro Pinto, Í. F., Lucchetti, A. L. G., da Silva Ezequiel, O., & Lucchetti, G. (2018). Comparison of the readiness for interprofessional learning and the rate of contact among students from nine different healthcare courses. Nurse Education Today, 63, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.013

Fahs, D. B., Honan, L., Gonzalez-Colaso, R., & Colson, E. R. (2017). Interprofessional education development: Not for the faint of heart. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 8, 329–336. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S133426

Ganotice, F. A., & Chan, L. K. (2018). Construct validation of the English version of Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS): Are Chinese undergraduate students ready for ‘shared learning’? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1359508

Grice, G. R., Thomason, A. R., Meny, L. M., Pinelli, N. R., Martello, J. L., & Zorek, J. A. (2018). Intentional interprofessional experiential education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 82(3), Article 6502. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6502

Hansson, A., Foldevi, M., & Mattsson, B. (2010). Medical students’ attitudes toward collaboration between doctors and nurses – A comparison between two Swedish universities. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(3), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903163439

Hoffman, S. J., Rosenfield, D., Gilbert, J. H. V., & Oandasan, I. F. (2008). Student leadership in interprofessional education: Benefits, challenges and implications for educators, researchers and policymakers. Medical Education, 42(7), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03042.x

Judge, M. P., Polifroni, E. C., & Zhu, S. (2015). Influence of student attributes on readiness for interprofessional learning across multiple healthcare disciplines: Identifying factors to inform educational development. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 2(3), 248–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2015.07.007

Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1959). Techniques for Evaluation Training Programs. Journal of the American Society of Training Directors, 13, 21–26.

Knowles, M. S. (1984). Andragogy in Action: Applying Modern Principles of Adult Learning (1st edition). Jossey-Bass.

Lauffs, M., Ponzer, S., Saboonchi, F., Lonka, K., Hylin, U., & Mattiasson, A.-C. (2008). Cross-cultural adaptation of the Swedish version of Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS). Medical Education, 42(4), 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03017.x

Lestari, E., Stalmeijer, R. E., Widyandana, D., & Scherpbier, A. (2016). Understanding students’ readiness for interprofessional learning in an Asian context: A mixed-methods study. BMC Medical Education, 16, Article 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0704-3

Li, Z., Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Adaptation and reliability of the Readiness for Inter Professional Learning Scale (RIPLS) in the Chinese health care students setting. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), Article 309. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1423-8

Lie, D. A., Forest, C. P., Walsh, A., Banzali, Y., & Lohenry, K. (2016). What and how do students learn in an interprofessional student-run clinic? An educational framework for team-based care. Medical Education Online, 21(1), Article 31900. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.31900

Mahler, C., Berger, S., & Reeves, S. (2015). The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS): A problematic evaluative scale for the interprofessional field. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(4), 289–291. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1059652

Makino, T., Shinozaki, H., Hayashi, K., Lee, B., Matsui, H., Kururi, N., Kazama, H., Ogawara, H., Tozato, F., Iwasaki, K., Asakawa, Y., Abe, Y., Uchida, Y., Kanaizumi, S., Sakou, K., & Watanabe, H. (2013). Attitudes toward interprofessional healthcare teams: A comparison between undergraduate students and alumni. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(3), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.751901

McFadyen, A. K., Webster, V., Strachan, K., Figgins, E., Brown, H., & McKechnie, J. (2005). The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale: A possible more stable sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(6), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500430157

McManus, K., Shannon, K., Rhodes, D. L., Edgar, J. D., & Cox, C. (2017). An interprofessional education program’s impact on attitudes toward and desire to work with older adults. Education for Health, 30(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.4103/efh.EfH_2_15

Ng, K. Y. Y., Leung, G. Y. C., Tey, A. J.-Y., Chaung, J. Q., Lee, S. M., Soundararajan, A., Yow, K. S., Ngiam, N. H. W., Lau, T. C., Wong, S. F., Wong, C. H., & Koh, G. C.-H. (2020a). Bridging the intergenerational gap: The outcomes of a student-initiated, longitudinal, inter-professional, inter-generational home visit program. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), Article 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02064-x

Ng, K. Y. Y., Leung, G. Y. C., Yow, K. S., Ngiam, N. H. W., Yeo, D. G. D., Tey, A. J.-Y., Lim, M. S. R., Tang, A. K. W., Chew, B. H., Tham, C. Y. X., Yeo, J. Q., Lau, T. C., Wong, S. F., Wong, C. H., & Koh, G. C.-H. (2020b). Impact of an interprofessional, longitudinal, undergraduate student-initiated home visit program towards interprofessional education. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-23744/v1

Paradis, E., & Whitehead, C. R. (2015). Louder than words: Power and conflict in interprofessional education articles, 1954-2013. Medical Education, 49(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12668

Parsell, G., & Bligh, J. (1999). The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Medical Education, 33(2), 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x

Patel, R. S., Bachu, R., Adikey, A., Malik, M., & Shah, M. (2018). Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: A review. Behavioural Sciences, 8(11), Article 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8110098

Schmitz, C. C., & Brandt, B. F. (2015). The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale: To RIPLS or not to RIPLS? That is only part of the question. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(6), 525–526. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1108719

Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, M. B. (1965). an analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3/4), 591–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2333709

Sunguya, B. F., Hinthong, W., Jimba, M., & Yasuoka, J. (2014). Interprofessional education for whom? – Challenges and lessons learned from its implementation in developed countries and their application to developing countries: A systematic review. PloS One, 9(5), Article e96724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096724

Tamura, Y., Seki, K., Usami, M., Taku, S., Bontje, P., Ando, H., Taru, C., & Ishikawa, Y. (2012). Cultural adaptation and validating a Japanese version of the readiness for interprofessional learning scale (RIPLS). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(1), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2011.595848

Toth-Pal, E., Fridén, C., Asenjo, S. T., & Olsson, C. B. (2020). Home visits as an interprofessional learning activity for students in primary healthcare. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 21, Article e59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423620000572

Tremblay, D., Drouin, D., Lang, A., Roberge, D., Ritchie, J., & Plante, A. (2010). Interprofessional collaborative practice within cancer teams: Translating evidence into action. A mixed methods study protocol. Implementation Science, 5, Article 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-53

Tyastuti, D., Onishi, H., Ekayanti, F., & Kitamura, K. (2014). Psychometric item analysis and validation of the Indonesian version of the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(5), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.907778

Vaughn, L. M., Cross, B., Bossaer, L., Flores, E. K., Moore, J., & Click, I. (2014). Analysis of an interprofessional home visit assignment: Student perceptions of team-based care, home visits, and medication-related problems. Family Medicine, 46(7), 522–526

Wakely, L., Brown, L., & Burrows, J. (2013). Evaluating interprofessional learning modules: Health students’ attitudes to interprofessional practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(5), 424–425. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.784730

West, C., Graham, L., Palmer, R. T., Miller, M. F., Thayer, E. K., Stuber, M. L., Awdishu, L., Umoren, R. A., Wamsley, M. A., Nelson, E. A., Joo, P. A., Tysinger, J. W., George, P., & Carney, P. A. (2016). Implementation of interprofessional education (IPE) in 16 U.S. medical schools: Common practices, barriers and facilitators. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 4, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2016.05.002

Wilhelmsson, M., Ponzer, S., Dahlgren, L. O., Timpka, T., & Faresjö, T. (2011). Are female students in general and nursing students more ready for teamwork and interprofessional collaboration in healthcare? BMC Medical Education, 11, Article 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-15

Wright, A. A., & Katz, I. T. (2018). Beyond burnout — Redesigning care to restore meaning and sanity for physicians. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(4), 309–311. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1716845

Zaudke, J. K., Paolo, A., Kleoppel, J., Phillips, C., & Shrader, S. (2016). The impact of an interprofessional practice experience on readiness for interprofessional learning. Family Medicine, 48(5), 371–376.

*Chek Hooi WONG

90 Yishun Central,

Khoo Teck Puat Hospital,

Singapore 768828

9 Lower Kent Ridge Rd, Level 10,

+65 6807 8001

Email: wong.chek.hooi@ktph.com.sg

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.