How do healthcare professionals and lay people learn interactively? A case of transprofessional education

Published online: 5 September, TAPS 2017, 2(3), 1-7

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-3/OA1033

Junji Haruta1, Kiyoshi Kitamura2 & Hiroshi Nishigori3

1Department of General Medicine and Primary Care, University of Tsukuba Hospital, Japan; 2International Research Center for Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Japan; 3Center for Medical Education, Kyoto University, Japan

Abstract

Lay people without a body of specialty knowledge, like the professionals, have not been able to partake in interprofessional education (IPE). Transprofessional education (TPE), which was defined as IPE with non-professionals /lay people, is an important extension of (IPE). A TPE programme was developed to explore how health professionals and lay people learn with, from and about each other in a Japanese community. The present study was conducted in a hospital and the surrounding community in Japan. An ethnographic study design was adopted, and the study participants were six lay individuals from the community and five professionals working in the community-based hospital. During the health education classes, the first author acted as a facilitator and an observer. On reviewing interview data and field notes using a thematic analysis approach, findings showed that healthcare professionals and lay participants progressed through uniprofessional and interprofessional before achieving transprofessional learning. Both type of participants became to transcend boundaries after sharing their viewpoints in a series of classes and recognized that they were important partners in their local community step by step, which increased their sense of belonging to the community. The transformation was driven by dynamic interaction of the following four factors: reflection, dialogue, reinforcement of ties, and expanding roles. We believe this process led both groups to come to feel collective efficacy and inspire healthcare professionals to reflect on their transprofessional learning. We clarified how healthcare professionals and lay people achieved transprofessional learning in a TPE programme where participants advanced through uniprofessional, interprofessional stage before achieving transprofessional learning.

Keywords: Interprofessional Education; Transprofessional Education; Ethnography; Health Education

Practice Highlights

- Healthcare professionals and lay participants became to transcend boundaries and recognized their sense of belonging to their community in a TPE program.

- The transformation was driven by dynamic interaction of the following four factors: reflection, dialogue, reinforcement of ties, and expanding roles.

- Both type of participants proceeded through uniprofessional and interprofessional learning before transprofessionally.

I. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the need for interprofessional education (IPE) has been underscored by challenges associated with expanding medical knowledge and technologies, such as the compartmentalization of medical specialties, increased need for ensuring patient safety, and assurance of healthcare quality (Frenk et al., 2010). In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasized the importance of IPE to mitigate the global workforce crisis and identified mechanisms for shaping successful collaborative teamwork, presenting possible action steps that policy-makers could take in their respective health systems. IPE is undoubtedly essential for promoting collaborative practice (Gilbert, Yan, & Hoffman, 2010).

Increasing emphasis has also been placed on patient involvement in the education of healthcare professionals, based on the concept that “patients are experts on their own personal and cultural context and their own stories of illness” (Centre For The Advancement Of Interprofessional Education, 2002). “Patient involvement” has a great potential to promote the learning of patient-centred practice, interprofessional collaboration, community involvement, shared decision making and how to support self-care (Towle et al., 2010). In this vein, Frenk et al. suggested that teamwork involving non-professional health workers, administrators and leaders of the local community, was vital to the smooth running of complex health systems (Frenk et al., 2010). In the field of interprofessional education, however, lay people without a body of specialty knowledge, like the professionals, have not been able to partake in IPE, as the term “interprofessional” might lead to the exclusion of lay people from active collaborative care (Vyt, Pahor, & Tervaskanto-Maentausta, 2015). They argued that transprofessional education (TPE), defined as IPE transcend traditional discipline boundaries (Stepans, Thompson, & Buchanan, 2002), was an important model that should be promoted as vigorously as IPE (Frenk et al., 2010), as it leads boundaries between professionals and lay people/patients to be blurred or vanish (Paul & Peterson, 2002). To encourage involvement of lay people beyond IPE, we developed a TPE programme, the details of which are described and explained herein.

Through this programme, we explored how lay people and multi-health professionals learned. Our research question was how healthcare professionals and lay people in a community learned with, from, and about each other in a TPE programme.

II. METHODS

A. Health education programme

In 2010, a TPE programme for lay people and healthcare professionals was developed and delivered to a hospital in Tokyo, Japan, as well as to the local community residing within easy visiting distance of the hospital. The first author (JH), an academic general practitioner, organized this TPE programme consisting of seven health education classes adapting social interdependence theory (Bruffee, 1998; Deutsch, 1949; Deutsch, 1962; Johnson, 2003). The term “health education” is used in accordance with the WHO definition: “any combination of learning experiences designed to help individuals and communities improve their health, by increasing their knowledge or influencing their attitudes” (World Health Organization, 2014).

Five healthcare professionals working in the hospital and six lay people living in the local area participated in this programme which was developed based on Harden’s 10-step approach (Harden & Davis, 1995). The learning outcome was first set to deliver information about well-being to lay people in the community. We hoped both lay and healthcare professional participants work and learn interactively through developing a series of health education class. Learning contents and methods were established through discussion between both groups.

Each health education class in our TPE programme was delivered in the following cycle, based on the Kolb’s experiential learning style theory (Kolb, 1984) and active learning theory (Graffam, 2007): pre-meeting, public bulletin, session, and two debriefing meetings. In the pre-meeting, healthcare professionals participants decided on session contents with lay participants, who then drafted an advertising leaflet about the session and distributed it to the community to recruit other community members to the class. Approximately 10 lay people participated in each session and were engaged in simulation (e.g. participants cut nails on clay fingers) or small group discussion (e.g. about their end-of-life plans). Debriefing meetings to share participants’ perspectives and values were organized a few days after each session, the conduct of which was facilitated by JH. Through these iterative cycles of developing each health education class, we incorporated both lay and healthcare professional participants’ interactions. We conducted the reflection session after completing six health education classes. The TPE programme is described in full in Table 1.

| Date | Main instructor | Session’s theme | Leaning methods | |

| 1 | June 9, 2010

2 hours |

First author (JH) (Physician) | Communication for connection

|

Interactive lecture and workshop |

| 2 | July 25, 2010

2 hours |

Nurse | Nail care

– Tinea pedis and ingrown nails |

Interactive lecture and simulation |

| 3 | August 29, 2010

2 hours |

Physical therapist | How to select the right shoes and how to walk correctly | Interactive lecture and demonstration |

| 4

|

November 23, 2010

2 hours |

Physician | End-of-life care | Narrative session and workshop |

| 5 | December 12, 2010

2hours |

|||

| 6 | February 6, 2011

3 hours |

Pharmacist, dietician | Efficacy of supplements and complementary foods | Interactive lecture and workshop |

| 7 | March 5, 2011 2 hours | All lay participants and health professionals | Reflection session | Small-group work |

Table 1: A Summary of the TPE Programme

B. Study participants

Lay candidates who lived within easy visiting distance of the hospital and healthcare professionals from the hospital were recruited to the TPE programme using convenience sampling (Babbie, 2007). The backgrounds of lay candidates varied; some had worked as nursery school teachers before, while others had been housewives. Some had chronic disease, and others had experienced being admitted to the hospital. JH then sent these candidates letters to confirm their willingness to participate in the study. The healthcare professional candidates were selected from each professional section (e.g. pharmacy section) using convenience sampling. JH sent them letters to confirm their willingness to participate in the study.

C. Methodology

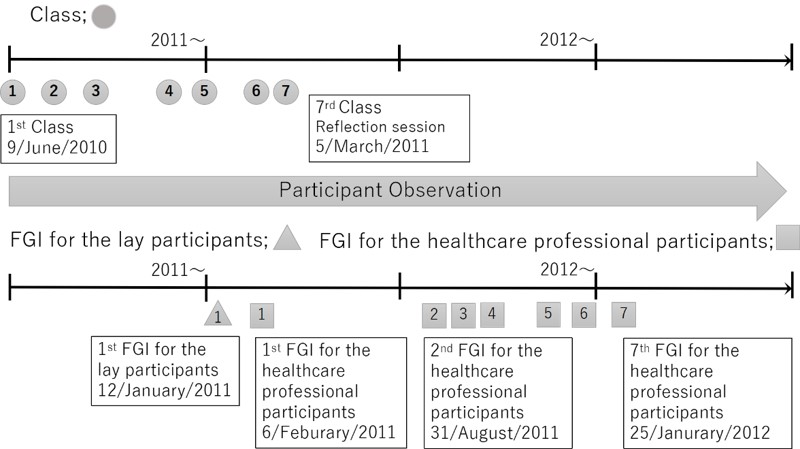

We used ethnography as the methodology for this study. Ethnography is a social research methodology “occurring in natural settings characterized by learning the culture of the group under study and experiencing their way of life before attempting to derive explanations of their attitudes or behaviour” (Goodson & Vassar, 2011). Ethnography is usually used in a single setting, and data collection is mainly conducted through participant observation and interviews (Atkinson & Pugsley, 2005). In our study, we conducted participant observation during the health education classes and in clinical settings as well as focus group interviews (FGIs) over the course of 2 years to clarify participants’ behaviour and understanding in regard to the health education classes. (Figure 1)

D. Data collection

JH observed participants by recording the class events, participants’ dialogues, responses to the health education sessions, and group interactions in each health education session. JH took field notes during the classes and then asked the healthcare professional participants through e-mail whether or not they thought the data were credible. The field notes were modified or supplemented as necessary based on the healthcare professional participants’ responses. In addition, after completion of the programme, we conducted a 90-minute FGI session for the 6 lay participants and a 120-minute FGI session for the 5 healthcare professional participants in January and February 2011, respectively. In the FGIs, participants were asked about their behavioural changes subsequent to the class.

JH continued to observe participants’ behaviours in the hospital and in the community until March 2012, and he also conducted monthly FGIs for the healthcare professional participants from August 2011 to January 2012. In the FGIs, we asked how participants’ behaviours had changed after completion of the TPE programme and how they perceived these changes. The FGIs were terminated in January 2012 on recognition that data had been saturated (Morse, 1994). In addition, we asked the participating nurse to write a reflective document that we also used as data, since she had not attended most of the FGIs. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: The flow of data collection

E. Analysis

All of the FGIs were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by JH. A thematic analysis method was used to analyse the interview data and field notes, in which the data were iteratively read and coded for emergent themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). First, JH and the last author (HN) read the transcripts separately. Second, the data were coded deductively based on the research questions, and inductive codes were created by JH. HN checked the inductive codes and modified as necessary. Third, JH and HN cooperatively identified and discussed the themes together from January 2011 to October 2014 for over 100 hours. This process was adopted to achieve richer interpretation of the data.

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the hospital, which considered sampling, informed consent, and the confidentiality of participants. All participants provided written informed consent for the observation and FGIs.

III. RESULTS

The lay participants who agreed to participate in this study were six females between 60 and 80 years of age; we suspect that only females agreed to participate because women tend to stay home whereas men tend to work outside of the home in Japan. The healthcare professional participants were five 24- to 30-year-old females’ healthcare professionals (a physician, a nurse, a pharmacist, a dietician, and a physical therapist) working in the hospital.

Analysing the themes and subthemes emerged by the thematic analysis, we found that healthcare professionals and lay participants needed to progress through two stages—uniprofessional and interprofessional stages—before learning transprofessionally. Participants displayed enhanced mutual understanding only in the interprofessional and transprofessional stages. Representative data of each stage are described below. Of note, once healthcare professionals and lay participants reached the transprofessional stage, they became advocates of inter/transprofessional learning within and beyond their community.

A. Uniprofessional stage

1) Healthcare professionals:

Healthcare professionals were used to working within their professions and did not even fully understand what the other healthcare professionals did. This lack of understanding was a typical uniprofessional perspective.

“I thought nurses and doctors would know more about pharmacists.” (Pharmacist)

“Nurses looked stern, so I did not feel able to ask questions.” (Dietician)

“I thought only doctors did health education, not us.” (Nurse)

[Healthcare professional participants felt annoyed because they were not used to dealing with questions that were difficult to understand, asked suddenly, or not contextualized.](Participant observation August 2010)

2) Lay participants:

Lay participants were used to paternalistic relationships with healthcare professionals. The lay participants, who had not known one another before the programme, had hierarchical relationships or else had no connections within their own group, so a few participants led the group while the rest followed. Their perspectives might be similar to the uniprofessional perspective observed among healthcare professionals.

[When the lay participants were asked by the researcher (as a participant observer) what they wanted to do (learn), no one answered anything. They said, “We would like YOU to tell us what you want to do, then we will consider how we can help.” A few led the group of lay participants, and others just followed.] (Participant observation in May 2010)

[We could not identify the needs of lay participants through questions. However, when the author gave examples, the lay participants started to show interest by nodding in response to the author’s comments. Although the lay participants had latent needs, these were not yet tangible or the lay participants were unable to verbalize them.](Participant observation May 2010)

B. Interprofessional stage

1) Healthcare professionals:

Discussion of specialty-boundary themes in the health education classes, where multiple specialties intersect, enhanced mutual learning between professionals, which helped them to understand their own speciality and their roles within the organization. In this stage, professionals learned with, from, and about each other to improve collaboration. Discovering perceptions of their profession by other professionals also strengthened their own professional roles.

“As I was listening to the pharmacist explaining the difference between acetaminophen and NSAIDs, I came to understand why a certain painkiller was used for a certain patient, and now I understand my patients more.” (Physiotherapist)

“For the first time, I understood that terms I thought of as standard (as a professional in my field) were unfamiliar to other professionals when they asked me what a word meant.” (Physiotherapist)

“Through discussion, we should record information in clearly understandable terms to share with other professionals, as many healthcare professionals are involved in patient care.” (Pharmacist)

2) Lay participants:

The lay participants discovered unique characteristics of their local community through the health education classes, which helped them to recognize their own roles and responsibilities in their community. In addition, they played a role as health advocates for the community by reporting discussion about health-related topics that they encountered in their daily lives with those who did not participate in health education classes. These classes provided opportunities for the participants to engage with other lay people and strengthened the relationships among them. They learned together how to improve their quality of life.

“When I was handing out an advertising leaflet for health education class, I found a unit of an apartment building smelling awful. I called the police, and they found one elderly person dead and another starving.” (Interview with lay participants)

[Lay participants shared their own understanding about the community with other participants after the event <in which they found an elderly person dead>. I felt that this prompted them to consider their role and responsibility in their community in order to avoid dying alone.] (Participant observation in January 2011)

“I have seen someone teaching his friend how to clip nails properly. The impact of the classes seems to have spread among the participants.” (Interview with lay participants)

“(First) it was hard to encourage others to attend a health education classes, but as we continued, people came to sessions regularly. As the number of attendees increased, trust was nurtured, which led to more attendees.” (Interview with lay participants)

C. Transprofessional Stage

Through the debriefing meetings in each health education class, the healthcare professionals came to view the lay people’s problems like their own affairs as if their boundaries was blurred, and the lay participants began noticing the healthcare professionals’ roles in their own community. In the seventh health education class (reflection session) in particular, the participants shared their perspectives and understanding of each other’s roles, values, positions, and problems. Through the interactions in these health education classes, they came to feel a partnership and an emotional attachment with each other. At this stage, they could transcend traditional disciplinary, and their boundaries be blurred. That is transprofessional learning. They also came to advocate for interprofessional and transprofessional learning within and beyond their community.

1) Healthcare professionals:

“[Lay participants] wanted to solve the issues and change our community. So, together, we made it happen.” (Interview with healthcare professionals)

“Attending a health education class for healthy individuals was a good experience, as I was able to learn about things I did not think of before, such as what lay participants are interested in or what they want to know.” (Nurse’s report)

“These classes stimulated both the lay participants and [healthcare professions] to be more energetic” (Interview with healthcare professionals)

[The healthcare professionals set up an IPE committee in their hospital as a hub of people in different professions which served as to promote collaboration.] (Participant observation after TPE programme)

[The physicians and pharmacists actively participated in academic conferences to publicize this programme. The nurse wrote articles (about their activities).] (Participant observation after TPE programme)

2) Lay participants:

“We would not have achieved such (work) without [the healthcare professionals’] cooperation. We worked together.” (Interview with lay participants)

“We felt very close to [the healthcare professionals]. When we saw some [of them] on other occasions, we felt like cheering.” (Participant observation in the reflection session)

[Since then, lay people have actively participated in a series of classes. They gave their opinions about not only the contents but also the order of the sessions.] (Participant observation November 2010)

[To let other people know about the programme, the lay participants made a poster presentation at a local networking event and published community papers (about their activities), which helped to enhance their sense of self-efficacy.] (Participant observation after TPE programme)

IV. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we clarified how healthcare professionals and lay people achieved transprofessional learning in a TPE programme where participants advanced through uniprofessional, interprofessional stage before achieving transprofessional learning.

In the uniprofessional stage, participants tended to reflect positively on groups they belonged to (in-group favouritism) and negatively on external groups (prejudice by selective perception) (Paradis et al., 2014). In our study, little to no interaction between these groups of participants meant they lacked tangible ties, as the previous study revealed (Granovetter, 1973). Participants had limited perspectives and had not categorized themselves as belonging to their own group, which hindered recognition of problems within their own groups.

In the interprofessional stage, healthcare professional participants came to have greater understanding of other professional roles and overcame the lack of interprofessional collaboration through dialogue. Lay participants expanded their perspectives by interacting among themselves and sharing the health-related topics discussed in health education classes. This interaction might strengthen ties among participants and increase feelings of equality among members within each group. In this stage, both groups of participants began learning beyond their uniprofessional outlook.

After previous two stages, participants transcended boundaries after sharing their viewpoints in a series of classes; step-by-step, participants learned more interactively. Healthcare professionals enriched their understanding of lay people’s problems, which they had not recognized before the programme. In addition, both types of participants recognized that they were important partners in their local community, which increased their sense of belonging to the community. They developed strong ties with each other that constituted a base of trust. In this transprofessional stage, participants learned with, from, and about each other beyond the viewpoints of the interprofessional stage.

Several aspects of the transformation between stages of learning warrant mention. First, we found that reflection was key to promoting transprofessional learning. Many participants clarified their agendas by sharing their experiences mainly in the reflection sessions, and this process allowed all participants to learn interactively. Second, we identified that participants became aware of other professional and lay perspectives through dialogue. Some participants compared their perspective with others, recognized differences, and came to respect others. This encouraged participants to explore new possible selves and integrate alternative perspectives, which could be explained as transformative learning by Mezirow (Freire, 2013; Mezirow, 1991) Third, the participants’ learning experiences strengthened the ties among healthcare professionals and lay participants. Their strong ties also motivated them to band together and contribute to their own community (Krackhardt, 1992). Finally, we recognized that both types of participants expanded their roles in our programme. This experience gave them confidence and motivation, which in turn strengthened them to promote transprofessional learning (e.g. from IPE to TPE).

Thus we argued that the transprofessional learning in this programme was driven by dynamic interaction of the following four factors: reflection, dialogue, reinforcement of ties, and expanding roles. Through this process, both groups came to feel collective efficacy, which is a group’s shared belief in its joint capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments (Bandura, 1997). They thus came to share the burden of responsibility for their community across boundaries and advocated for transprofessional learning.

One strength of the present study was the involvement of non-professionals in the education of healthcare professionals. As noted in the introduction, TPE is a theme in the field of medical education that merits further research. Another strength of the study was asking, as Cook suggested, not only “Did it work?” but clarifying “How did it work?” (Cook, Bordage, & Schmidt, 2008). We described the process of how healthcare professionals and lay people learn together through ethnography. However, several limitations to the present study also warrant mention. First, the data were obtained from a single programme implemented in a single region in Japan with a relatively small population. A multi-centred study with a larger population is therefore warranted. Second, the data were collected only for two years. Studies examining the long-term effects of such a programme should be conducted. Third, the author’s role (JH) as a facilitator might have influenced participants’ responses.

V. CONCLUSION

In this study, we clarified how healthcare professionals and lay people in a community learned interactively in a TPE programme. Our participants proceeded first through uniprofessional and interprofessional stages before being able to learn transprofessionally. We described an example of how healthcare professionals and lay people promoted collaborative learning. We hope that our study will encourage healthcare practitioners involved in transprofessional education to reflect on and improve their programmes.

Notes on Contributors

Junji Haruta is an Assistant Professor in Department of General Medicine and Primary Care, University of Tsukuba Hospital, Japan. He holds PhD of Medical Education in the University of Tokyo. His areas of interest and research are in the interprofessional and transprofessional education /collaboration. He formalized in his PhD (2011-2015) on this subject.

Kiyoshi Kitamura is a Professor in International Research Center for Medical Education, Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo, Japan.

Hiroshi Nishigori is an Associate Professor in Center for Medical Education, Kyoto University, Japan.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Helena Law for reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 2459062 Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C).

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the hospital, which considered sampling, informed consent, and the confidentiality of participants. All participants provided written informed consent for the observation and FGIs.

Declaration of Interest

The all authors have no declarations of interest.

References

Atkinson, P., & Pugsley, L. (2005). Making sense of ethnography and medical education. Medical Education, 39(2), 228–34.

Babbie, E. (2007). The Ethics and Politics of Social Research. In E. Babbie (Ed.), The Practice of Social Research. Thomson Wadsworth.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. (W.H.Freeman, Ed.). New york: Worth Publishers.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematica Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Bruffee, K. A. (1998). Collaborative Learning: Higher Education, Interdependence, and the Authority of Knowledge (2nd ed.). London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. (2002). CAIPE. Retrieved from http://caipe.org.uk/resources/defining-ipe/

Cook, D. A., Bordage, G., & Schmidt, H. G. (2008). Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education. Medical Education, 42(2), 128–133.

Deutsch, M. (1949). A Theory of Co-operation and Competition. Human Relations, 2(2), 129–152.

Deutsch, M. (1962). Cooperation and trust: Some theoretical notes. In I. M. R. .Jones (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 275–319). Lincoln, NE:University of Nebraska Press.

Freire, P. (2013). Education for Critical Consciousness (Bloomsbury Revelations). Bloomsbury Academic.

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., … Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376(9756), 1923–1958.

Gilbert, J. H. V, Yan, J., & Hoffman, S. J. (2010). A WHO Report: Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Journal of Allied Health, 39, 196–197.

Goodson, L., & Vassar, M. (2011). An overview of ethnography in healthcare and medical education research. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 8(4).

Graffam, B. (2007). Active learning in medical education: strategies for beginning implementation. Medical Teacher, 29(1), 38–42.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Jounal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Harden, R. M., & Davis, M. H. (1995). AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 5. The core curriculum with options or special study modules. Medical Teacher, 17(2), 125–148.

Johnson, D. W. (2003). Social interdependence: interrelationships among theory, research, and practice. The American Psychologist, 58(11), 934–45.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development.

Krackhardt, D. (1992). The Strength of Strong Ties: The Importance of Philos in Organizations. In N. Nohria & R. Eccles (eds.), Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Adult learning (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In Y. S. Lincoln (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., p. 220–235.). Denzin, New York: Thousand Oaks, Sage.

Paradis, E., Reeves, S., Leslie, M., Aboumatar, H., Chesluk, B., Clark, P., … Kitto, S. (2014). Exploring the nature of interprofessional collaboration and family member involvement in an intensive care context. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(1), 74–5.

Paul, S., & Peterson, C. Q. (2002). Interprofessional collaboration: issues for practice and research. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 15(3–4), 1–12.

Stepans, M. B., Thompson, C. L., & Buchanan, M. L. (2002). The role of the nurse on a transdisciplinary early intervention assessment team. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 19(4), 238–45.

Towle, A., Bainbridge, L., Godolphin, W., Katz, A., Kline, C., Lown, B., … Thistlethwaite, J. (2010). Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Medical Education, 44(1), 64–74.

Vyt, A., Pahor, M., & Tervaskanto-Maentausta, T. (2015). Interprofessional education in Europe: Policy and practice. Garant Uitgevers N V.

World Health Organization (2014). Health education. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/topics/health_education/en/

*Junji Haruta

2-1-1 Amakubo Tsukuba Ibaraki

Japan

Tel: +81-29-853-3189

Fax: +81-29-853-3189

Email: junharujp@gmail.com

Announcements

- Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.