Faculty’s perception of their role as a tutor during Problem-Based Learning activity in undergraduate medical education

Submitted: 17 August 2023

Accepted: 21 December 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 87-91

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/SC3114

Isharyah Sunarno1,2, Budu Mannyu2,3, Suryani As’ad2,4, Sri Asriyani2,5, Irawan Yusuf 2,6, Rina Masadah2,7 & Agussalim Bukhari2,4

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 2Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 3Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 4Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 5Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 6Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; 7Department of Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction: The study aimed to ascertain how the faculty at the Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University perceived their role as a tutor during a problem-based learning activity during the academic phase of medical education, based on the length of time they acted as a tutor.

Methods: This was prospective observational research with an explanatory sequential mixed-method design, which was performed at the Undergraduate Medical Study Program, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, from January 2023 until May 2023. Research subjects were divided into two groups: a) the Novice group and b) the Expert group. Quantitative data were collected by giving a questionnaire containing six categories with 35 questions and distributed by Google form. An independent t-test was used to compare the faculty’s perception, with a p-value <.05 significant. Followed by Focus Group Discussion (FGD) for qualitative data, which then were analysed by thematic analysis. The last stage is integrating quantitative and qualitative data.

Results: There were statistically significant differences in seven issues between the two groups. Most of the tutors in both groups had favorable opinions, except for the expert group’s disagreement with the passive role of the tutor in the tutorial group. Eight positive and twelve negative perceptions were found in the FGD.

Conclusion: Most tutors positively perceived their role in PBL, with the expert group having more dependable opinions and well-reasoned suggestions.

Keywords: Problem-Based Learning, Undergraduate Medical Education, Focus Group Discussion

I. INTRODUCTION

The transition from teacher-centered to student-centered learning occurs with the introduction of active learning based on the needs of the students. The majority of effective active learning activities in the classroom were created in small groups using the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) approach. PBL has no worse outcomes in terms of academic performance and is more effective than conventional methods at enhancing social and communication skills, problem-solving abilities, and self-learning abilities, and allows the students to collaborate while integrating science, theory, and practice (Trullàs et al., 2022; Wiggins et al., 2017). A tutor or a facilitator is a pertinent element for the success of tutorial activities in PBL, thus evaluating periodically their perception and understanding about PBL activities, will help determine the need for resource development at the faculty level. Based on the aforementioned background, the author is intrigued to understand how the faculty at the Undergraduate Faculty of Medicine at Hasanuddin University perceived their role as a tutor during a PBL activity based on the duration they acted as a tutor.

II. METHODS

Short-case PBL tutorial is the model being implemented in our institution. An explanatory sequential mixed-methods observational prospective design study was carried out from January 2023 to May 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants (ethics approval recommendation number: 99/UN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2022). The study was conducted in three stages (Figure 1):

A. Stage 1

Gathering quantitative data via a survey disseminated using Google form, after which the information was analysed using SPSS version 25. The Likert scale, which ranged from 1 (extremely disagree) to 5 (extremely agree), was used to evaluate the 35 items in the questionnaire that served as the study’s primary data collection tool (Table 1 which is openly available on Figshare). The validity and reliability test for the study’s questionnaire was carried out as the first step and the Pearson Correlation was used to examine the outcome; all questions were valid with Cronbach’s α .951. The next step was to collect data through convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria were lecturers who: have attended training to become PBL tutors, are actively involved in PBL activities, and are willing to participate in the research projects to completion. Exclusion criteria were lecturers who were not familiar with the Google form application. Subjects with other commitments that prevented them from finishing the research activities and with a conflict of interest in continuing the study were considered dropouts. The research participants were split into two groups: the novice group (participants who served as tutors for less than five years) and the expert group (participants who served as tutors for five years or more). The Slovin formula was used to determine the minimum sample size, and the result was 32 people for each group. Characteristics of the study subjects were presented descriptively. An independent t-test was used to compare the faculty’s perception of their role as a tutor during a problem-based learning activity, with a p-value <.05 significant.

B. Stage 2

Focus Group Discussions (FGD) were held to collect qualitative data. The participants in the FGD were divided into two groups using the identical criteria utilised for the quantitative group categorisation, and each group consisted of six subjects. Each participant received a set of open-ended questions to be discussed during the FGD. All events and discussions were recorded, and then all conversations were transcribed using the VERBATIM app. MAXQDA 2020 was then used to tag and categorise the data. Thematic analysis was used to assess qualitative data. We used an audit trail and triangulation during data collection and conducted a peer review during data analysis to ensure the validity of the qualitative data.

C. Stage 3

Integrating quantitative and qualitative data was performed by linking data, followed by integration at the interpretation and reporting level which was conducted by integration through a narrative with a weaving approach.

III. RESULTS

A. Characteristics of the Subjects

The subjects in the novice groups were all under 45 years old, but the expert group was predominately made up of older faculty members. Both groups were predominately female. At the time of the research, medical doctors dominated the novice group, but the expert group included people with a range of educational backgrounds. Characteristics of the study subjects are openly available in Table 2 on Figshare.

B. Quantitative Data

Seven question items from four categories significantly differed between the novice and expert groups as shown in Table 3 which is openly available on Figshare.

C. Qualitative Data

Thematic analysis from the FGD revealed that the expert group only has negative perceptions, whereas the novice group has both negative and positive perceptions. The data are openly available in Table 4 on Figshare.

D. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

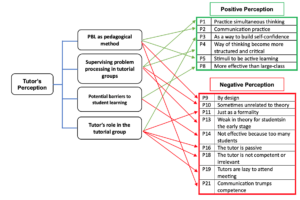

Faculty staff has the same perception about almost all concepts about the role of a PBL tutor, except for seven concepts that were statistically significantly different (Figure 1):

1) PBL as Pedagogical Method: Q5 (group tutorials help students share experiences) and Q9 (PBL is a great tool for student learning) were significantly different, with the majority of the novice group agreeing with it while the majority of the expert group were extremely agreeable. Nevertheless, while the novice had a positive perspective shown in the discussion, the expert expressly stated that “(PBL) increased the (student’s) ability to discuss but not the depth of knowledge.”

2) Supervising Problem Processing in Tutorial Groups: Q12 (I function as a resource person in the group) and Q13 (I participate in creating a positive work environment for the group) were significantly different, with most of the novice group agreeing to the concept while the majority of the expert group were extremely agreeable. The novice group stated in the FGD that “PBL is very effective for building students’ analytical skills because the students can interact with each other to express their opinions and find key problem-solving strategies.” Both groups had the same perception that some tutors attended the PBL activities “just as a formality.” Q17 (I am sensitive to the wishes of the students regarding their need for support) was also significantly different, with most participants in both groups agreeing that tutors are sensitive to the student’s need for support, but 5.71% of the novices extremely disagreed. In contrast, none of the experts in the expert group disagreed with the concept. From the FGD results, the expert group suggested that the “tutor should give feedback and guidance to the students”.

3) Potential Barriers to Student Learning in PBL: the majority of both groups agreed that the group size is just right from a tutorial point of view (Q24), but the novice group had a wide range of responses (from extremely disagree to extremely agree), while 77.14% of the expert group agreed. “Six to eight students in one PBL group” is an elaborate suggestion made by the expert group as a result of the FGD.

4) There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the role of the tutor, which is usually passive in the tutorial group (Q29), with the expert group’s consensus on the matter being unfavorable, whereas the novice group’s responses were evenly split between neutral and disagree. The FGD’s results revealed that the novice merely stated, “If the students had a misleading concept, the tutor could not be kept silent,” whereas the expert suggested, “The tutor should be the chairman of the group discussion,” and “Questions and keywords must be made by the tutor.”

Figure 1. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

IV. DISCUSSION

PBL can be regarded as a multidisciplinary method that allows the learners to resolve real-life problems and situations in every aspect, learn how to construct new information meaningfully, put away the understanding of ready-to-use knowledge, and acquire critical thinking skills. Problem processing or facilitation is a challenging task (Aydogmus & Mutlu, 2019). Since PBL can be used in specific topics and can break up the monotony of traditional didactic teaching, it has become a popular alternative teaching strategy for undergraduate medical students. It can also be used as a method of integrated teaching. Overall, it is a great tool for students learning (Gadicherla et al., 2022).

The group size is one of the possible obstacles to students’ learning in PBL. All students will not be able to participate in a team that is too big. A team that is too small could not have enough members to address the learning objectives or enough diverse opinions to guarantee a robust discussion. The tutor should be aware of how the participants play their roles, noting those who do not contribute to debates or who are silent. Therefore, they must pay close attention to what is happening in the group process to intervene and provide feedback, promoting the participants’ individual and group progress. The tutor can assist the student in identifying their requirements through motivated evaluations and simple feedback, fostering the growth of self-confidence, autonomy, and, ultimately, integration into group dynamics. PBL teams ideally consist of 6–10 students (Dent et al., 2017).

V. CONCLUSION

Aside from seven concepts, both groups mostly had positive perceptions about their role as tutors, with the expert group having more dependable opinions and well-reasoned suggestions.

Notes on Contributors

Isharyah Sunarno made the following contributions to the study: conceptualised, created the initial draft and study design, investigated and collected data, conducted formal analysis, looked for research references, performed critical revision of the article, reviewed and edited the article, and approved the study’s final published version.

The following are the contributions Budu Mannyu made to the study: provided insights into the methodology, suggested research references, served as a peer reviewer of the study’s findings, performed critical revision of the article, and gave his approval of the final draft to be published.

Suryani As’ad contributed the following to the study: she offered insights into the methodology, proposed research references, served as a peer reviewer of the study’s findings, revised the article critically, and approved the final draft of the manuscript to be published.

The study benefited from Sri Asriyani’s efforts, which included: suggestion for research references, peer review of the study’s findings, and performed critical revision of the article.

The following contributions were made to the study by Irawan Yusuf: peer reviewing of the result, supervising the research activities, and critical editing of the publication.

The following are the contributions Rina Masadah contributed to the study: provided ideas into the original draft, supervised the research activities, and edited the publication critically.

Agussalim Bukhari made the following contributions to the study: offered insights into the methodology, oversaw the research activities, critically revised the final version of the article.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee Faculty of Medicine Hasanuddin University with recommendation number: 99/UN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/ 2022.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary material for research instrument in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23646918

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the tutors who participated in this study. A special appreciation is given to Ichlas Nanang Affandi and A. Tenri Rustam from the Psychology Study Program, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University for their valuable support throughout the research process, including their role as the facilitator of the FGD. We also would like to thank Andriany Qanitha and the CRP team from Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University for their support in developing the manuscript. We are also grateful to the Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University for providing us with the resources and support we needed to complete this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Aydogmus, M., & Mutlu, A. (2019). Problem-based learning studies: A content analysis. Turkish Studies-Educational Sciences, 14(4), 1615–1630. https://doi.org/10.29228/turkishstudies.23012

Dent, J. A., Harden, R. M., & Hunt, D. (2017). A practical guide for medical teachers (5th ed.). Elsevier.

Gadicherla, S., Kulkarni, A., Rao, C., & Rao, M. Y. (2022). Perception and acceptance of problem-based learning as a teaching-learning method among undergraduate medical students and faculty. Azerbaijan Medical Journal, 62(03), 975–982.

Trullàs, J. C., Blay, C., Sarri, E., & Pujol, R. (2022). Effectiveness of problem-based learning methodology in undergraduate medical education: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03154-8

Wiggins, B. L., Eddy, S. L., Wener-Fligner, L., Freisem, K., Grunspan, D. Z., Theobald, E. J., Timbrook, J., & Crowe, A. J. (2017). ASPECT: A survey to assess student perspective of engagement in an active-learning classroom. CBE Life Sciences Education, 16(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-08-0244

*Isharyah Sunarno

Jl. Perintis Kemerdekaan Km. 11,

Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University

+62411-585859

Email: isharyahsunarno@gmail.com

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.