Digital badges: An evaluation of their use in a Psychiatry module

Submitted: 19 August 2022

Accepted: 5 December 2022

Published online: 4 April, TAPS 2023, 8(2), 47-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-2/OA2869

Edyta Truskowska1, Yvonne Emmett2 & Allys Guerandel1

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland; 2National College of Ireland, Ireland

Abstract

Introduction: Digital Badges have emerged as an alternative credentialing mechanism in higher education. They have data embedded in them and can be displayed online. Research in education suggests that they can facilitate student motivation and engagement. The authors introduced digital badges in a Psychiatry module in an Irish University. Completion of clinical tasks during the student’s clinical placements, which were previously recorded on a paper logbook, now triggers digital badges. The hope was to increase students’ engagement with the learning and assessment requirements of the module.

Methods: The badges – gold, silver and bronze level – were acquired on completion of specific clinical tasks and an MCQ. This was done online and student progress was monitored remotely. Data was collected from the students at the end of the module using a questionnaire adapted from validated questionnaires used in educational research.

Results: The response rate was 68%. 64% of students reported that badges helped them achieve learning outcomes. 68% agreed that digital badges helped them to meet the assessment requirements. 61% thought badges helped them to understand their performance. 61% were in favour of the continuing use of badges. Qualitative comments suggested that badges should contribute to a higher proportion of the summative mark, and identified that badges helped students to structure their work.

Conclusions: The findings are in keeping with the literature in that engagement and motivation have been facilitated. Further evaluation is required but the use of badges as an educational tool is promising.

Keywords: Medical Education, Digital Badges, Students’ Engagement, Continuous Assessment Gamification, Health Profession Education

Practice Highlights

- Digital badges may enhance student engagement.

- Digital badges may promote motivation for learning.

- Evaluation of digital badges using a questionnaire with ordinal analysis of data and coding of free comments.

- Majority of students reported working harder than in a non-gamified module.

- Digital badges provided structure and direction to the student’s learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

Educational research recognises student engagement as valuable and as having significant impact on their learning (Mandernach, 2015). While searching for tools impacting on engagement, educators observed that games have been good at engaging players for decades, through their ability to sustain players’ attention and keep them motivated throughout the games (Przybylski et al., 2010). This level of engagement is desirable to both students and educators. This achievable level of engagement in gaming strategies has led to the exploration of its use in education. Elements from game design applied in non-game contexts to influence, engage and motivate individuals and groups have resulted in the development of a new field known as gamification (Deterding et al., 2011).

Digital badges are common tools of gamification (Barata et al., 2013). They are frequently used by game designers and in recent years also by educators. A digital badge used in education can be a validated symbol of academic achievement, accomplishment, skill, quality or interest (HASTAC, n.d.). Digital badges are digital images obtained through the completion of some pre-specified goals that are annotated with metadata and that can be displayed online (Hensiek et al., 2017). In higher education badges have been used to recognise a student’s participation in a learning activity, to help students explicitly and visually capture and monitor progress made on learning tasks, to recognise the achievement of skills and competencies and to serve as a means of certifying these achievements. They are reported to have a positive effect on the learners’ motivation if they are considered as awards or if they trigger competition among peers (Yildirim et al., 2016).

It appears that the value of digital badges depends on their design (when awarded, for what, and what they mean). For example, the use of badges as credentials only, has been criticised for focusing exclusively on extrinsic motivating factors, which have less impact on engagement than intrinsic ones (Seaborn & Fels, 2015). This is why combining the use of badges, as credentials as well as using them within the assessment process appears to be a better idea. Considering, that assessment has proven to have the most impact on effective learning, the use of badges during structured assessment has been favoured by educators (Abramovich, 2016; Rolfe & McPherson, 1995). The assessments that have potential to generate formative and summative feedback are presented as particularly useful (Armour-Thomas & Gordon, 2013). Digital Badges represent a viable alternative to existing methods of assessment in educational institutions and in the work environment (Dowling-Hetherington & Glowatz, 2017). It was also noted that access to regular feedback (broadly available in games) is helpful to learners. Students that are given opportunities to complete a task and learn from their mistakes do better in overall assessment. Games are a great example of the design where a player learns through feedback, gets better and eventually becomes successful (McGonigal, 2011). Similarly, the literature states that the use of badges has potential to offer a sort of “covert assessment”, meaning that students can approach a task as if it was a game. This helps to maintain the benefits of assessment while minimizing the potential for unhelpful levels of test anxiety (McGonigal, 2011) (Abramovich et al., 2013).

Another advantage given for the use of digital badges is their potential for remote monitoring of students’ progress and their difficulties by instructors and tutors (Huang & Soman, 2013). There is a growing momentum for the use of digital badges as an innovative instruction and credentialling strategy in higher education (Noyes et al., 2020).

In our University, Psychiatry is taught as a 10-credit module to both undergraduate and graduate entry students in the final stage of their degree in medicine. Typically, approximately 240 students are taught the module in four different groups: two groups in the spring and two groups in autumn, for six weeks at a time. Face to face teaching is centralized on Mondays and Fridays. Clinical teaching is delivered during the rest of the week and takes place in multiple different clinical centres. The overall assessment of this module comprised a continuous assessment with specific formative and summative tasks recorded in a paper logbook. The summative tasks were worth 20% of their overall assessment.

Standardising the student clinical experience, engaging them in their clinical placements and monitoring their attendance and progress can be challenging. The paper logbook/portfolio we were using was inadequate in that it did not allow for central monitoring of progress and often the difficulties students were encountering came to the attention of the teaching staff only when the logbook was handed over at the end of the module. Provision of feedback on progress was also limited. We felt that, in particular, students that were slow to progress were missing potential remediation before the summative assessments. We also encountered practical difficulties such as lost logbooks that affected the continuous assessment process.

We felt that digital badges offered a way of monitoring attendance and participation in tasks remotely, providing feedback, facilitating remediation and allowing students’ gauge how they are doing in relation to their peers while optimizing engagement in the clinical placements and structuring the learning to sustain progress through the module. We introduced and piloted the use of digital badges in the Psychiatry module as part of the continuous assessment. We carried out a descriptive study to appraise the potential usefulness of digital badges as part of our teaching strategy.

II. METHODS

A. Course Design

Students taking the 6-week Psychiatry module start their clinical placement on day 2 of the Module. Each week, students participate in their continuous assessment in order to collect their weekly badge. To acquire a badge, they need to complete and upload specific clinical tasks including formative clinical cases scheduled for them, to upload a Clinical Placement Form signed by the consultant on the team they are attached to and do an online multiple-choice question test at the end of the week. As all of this is done online their progress can be monitored remotely by the teaching team independent of the location of their clinical placement. Collecting their weekly badges provides them with 5% of their continuous assessment mark. The other marks for continuous assessment come from a summative clinical case (90%) and a reflective assignment (5%). Continuous assessment contributes to 20% of overall assessment mark.

B. Badges Design

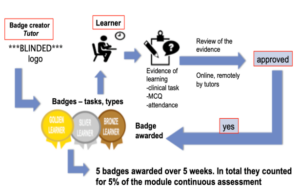

Tutors in Psychiatry in conjunction with the University’s Teaching and Learning Department created Badges. It was part of an institution-wide digital badging pilot project (UCD Teaching and learning, 2017). It was agreed that there would be three types of badges -bronze, silver and gold – obtained and displayed on the university’s virtual learning environment (currently, Brightspace). As noted above students receive a digital badge on completion of assigned tasks, which are part of their continuous assessment. The type of badge awarded depends on the MCQ score and it is displayed on the student’s Blackboard profile. Figure 1 depicts the process. It shows that all badges are contributing to 5% of the module continuous assessment. Every week students receive information as to what percentage of the group has acquired a bronze, silver or gold badge so they have an idea of their performance in relation to that of the rest of the group.

Figure 1. Step-by-step the process of getting/awarding a badge

C. Questionnaire

The ‘Digital Badges Experience Survey’ questionnaire was designed based on previously described surveys: the ARCS Badge Motivation Survey (Foli et al., 2016) and the Badge Opinion Survey (Abramovich et al., 2013) with some additional questions suggested by the literature on digital badges. The authors and faculty members identified and agreed on the following constructs as being relevant to our teaching delivery and our study: previous knowledge of digital badges (items 1 & 2), their meaning and relevance to students (items 22, 13, 14, 12, 8 & 5) motivation and engagement (items 3, 4 & 23), relevance to assessment and feedback (items 11, 9, 10, 24, 18 & 19), their use in structuring learning (items 15, 6, 7 & 16), self-efficacy (items 17, 20, 21 & 25), social context implication (items 26, 27 & 28). Under each construct, items from the above questionnaires were discussed and agreement reached on the ones to be used, altered or added assessing relevance and acceptability for our aims and teaching context.

Our survey consisted of 30 items with answers displayed on a seven-point Likert Scale. The 31st (final) question required dichotomous (yes/no) answer with space for respondents to explain their reasons for it. We also provided for free commenting from students (Questionnaire is available in Table 1).

Please rate your agreement with each of the statements using the following scale:

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Somewhat Agree |

Neutral |

Somewhat Disagree |

Disagree |

Strongly Disagree |

||

|

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

– 1 |

-2 |

-3 |

||

|

Please circle one number for each statement |

Strongly Agree |

|

|

Strongly Disagree |

||||

|

1. I knew what digital badges were before I began this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

2. I have earned digital badges before beginning this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

3. I felt motivated to complete the module because I was earning digital badges. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

4. Compared to other modules on my programme, the digital badges motivated me to work harder. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

5. The digital badges helped me to understand the learning outcomes for this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

6. The digital badges helped me to achieve the learning outcomes for this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

7. The badge helped draw my attention to the clinical seminars. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

8. The digital badges helped me to understand the content of this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

9. The digital badges helped me to understand the assessment requirements for this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

10. I was more aware of the module continuous assessment requirements because I would be earning digital badges. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

11. Because I was earning digital badges, I knew the continuous assessment requirements were important. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

12. Earning digital badges made a difference in how I viewed completing the continuous assessment requirements. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

13. Earning badges made the assignments more significant to me. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

14. The badges increased how relevant the assignments were. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

15. The digital badges helped me to structure my work in this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

16. The digital badges helped me to meet the assessment requirements of this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

17. The badges increased my confidence that I could demonstrate the content of my knowledge. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

18. The digital badges helped me to understand my performance in this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

19. The digital badges helped me to understand my progress through the module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

20. The badges were symbols that I had mastered content. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

21. The badges increased my overall level of satisfaction with completing the continuous assessment requirements. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

22. By earning the badges I was more fulfilled as a student by completing the assessment requirements. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

23. The digital badges made me want to keep on working. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

24. I understand why I earned all of my badges. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

25. The badges I earned represent what I learned on this module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

26. I talked to others about the badges I earned. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

27. I compared the badges I earned with others’ on the module. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

28. The potential to earn digital badges at gold, silver and bronze levels made me feel competitive. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

29. I think digital badges are a good addition to the programme. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

30. I would like to earn digital badges in other modules on my programme. |

+3 |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

|

31. I think the badges are helpful and should be used in the coming years: tick as appropriate and give 3 reasons why |

Yes ☐ |

No ☐ |

||||||

|

32. Any other comments |

||||||||

Thank you for your participation

Table 1. Digital Badges Experience Survey

D. Participants

The questionnaires were distributed to all the students of final year of Medicine in our university at the beginning of the final or sixth week of the module and collected by their tutors. Informed verbal consent was obtained from study participants. As described above, the course was run four times in one academic year, and we collected data from all four groups of students: two in the spring and two in the autumn.

E. Data Collection and Analysis

As noted above, questionnaires were distributed and collected by tutors at the beginning of the sixth (last) week of the Psychiatry Course. The level of student’s agreement with various statements was marked on the 7-point Likert-type scale. Those data were uploaded to Excel. Data from Likert scales can be analysed as ordinal as well as interval data (Sullivan & Artino 2013), (Norman, G. 2010) and we have considered both options. We concluded that using descriptive statistics such as the mean in relation to students’ opinions had limited value (Sullivan & Artino 2013), (Knapp 1990). This is why we decided to analyse our data as ordinal. To simplify the answers, we organised them into three groups: “agreed”, “neutral”, “disagreed”.

Students’ comments were entered into an excel sheet and analysed by two independent researchers. The comments relating to the use of badges in teaching of Psychiatry were coded according to topics, which were identified and agreed upon by the two independent researchers (Johnson & LaMontagne, 1993), (Sundler et al., 2019). Topics were further codified as positive or negative. This way of coding is described and performed in more details in other studies (Quesenberry et al., 2011).

III. RESULTS

A. Demographics

161 out of 237 students completed questionnaires giving a 68% response rate. The response rate was 75% in the first half (from springtime) of the students and 61% in the second (autumn rotation).

B. Analysis of Answers

65% of students had no previous knowledge of digital badges and 93% had never earned a badge before the module as per items 1 & 2 of questionnaire.

1) Meaning and relevance: Item 22: 48% of respondents agreed that by earning the badges they felt more fulfilled as a student when completing the assessment requirements. 31% disagreed. 45% agreed and 39% disagreed that earning badges made the assignments more significant to them (item 13) and similarly only 42% felt the badges increased the sense of how relevant the assignments were, while 40 % disagreed with this view as per item 14.

Earning digital badges made a difference in how 59% of students viewed completing the continuous assessment requirements, (item 12). 29% disagreed with this. 68% students felt that the digital badges helped them to understand the content of this module and 18% disagreed, (item 8). 66% students agreed and 24% disagreed about the fact that digital badges helped them to understand the learning outcomes for this module (item 5).

2) Motivation and engagement: 51% of students that responded felt motivated to complete the module because they earned a digital badge (item 3). 33% did not agree with this. The possibility of earning a digital badge motivated 43% of respondents to work harder (item 4). 39% disagreed with this. The digital badges made 45% of students want to keep on working, while 29% were not impacted (item 23).

3) Assessment and feedback: Item 11: 50% felt that because they were earning digital badges, they knew that the continuous assessment requirements were important. 36% disagreed. The digital badges also helped 69% respondents to understand the assessment requirements for this module but not so for the 15% respondents (item 9). Out of all respondents, 78% were more aware of the module continuous assessment requirements because of the digital badges, and only 15% disagreed with that (item 10). Item 24: As many as 74% of all respondents did and 14% did not understand why they earned their badges. The digital badges helped 61% of students to understand their performance in this module (item18). 27% did not find that badges helped in that way. Similarly, the digital badges helped 61% of students to understand their progress through the module. 22% disagreed with this (item 19).

4) Structure: Out of all respondents 50% agreed and 33% disagreed that the digital badges helped them to structure their work in the module (item 15). 64% of respondents agreed and 21% disagreed that the digital badges helped them to achieve the learning outcomes for this module (item 6). Similarly, the badge helped draw attention to the clinical seminars for 57% of respondents, but not so for 25%. 68% of students (vs 19% who have disagreed) felt that the digital badges helped them to meet the assessment requirements of this module (item 16).

5) Self-efficacy: Item 17: 48% of students agreed (vs 33% who disagreed) that earning the digital badges made them more confident that they could demonstrate the content of their knowledge. Item 20: 41% of all respondents agreed that the badges were symbols of mastering the content of the module. A similar number (40%) of students disagreed and 17% stayed neutral. 59% found the badges increased their overall level of satisfaction with completing the continuous assessment requirements (item 21). 27% disagreed with this. 44% of students agreed and 41% disagreed with the statement that the badges they earned represented their learning in the module (item 25).

6) Social context and competitiveness: 42% of students did and 44% did not talk to others about the badges they earned (item 26). The potential to earn digital badges at gold, silver and bronze levels made 49% of students more competitive (item 28). 39% disagreed with this. 29% of students did and 56% did not compare the badges they earned with others on the module (item 27).

7) Overall: 56% agreed that digital badges were a good addition to the program. 61% of students found digital badges helpful and felt that they should be used in the future. 31% did not agree with the statement and 8% did not answer.

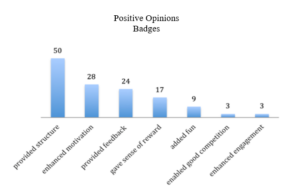

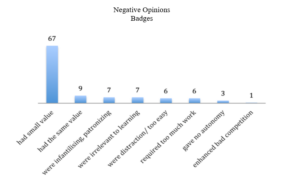

Students’ opinions: 136 students did and 25 students did not write any comment. Students’ comments related either to one or to several topics. Students were positive about the use of badges (in various topics) 134 times (See Figure 1) and negative/critical 106 times (See Figure 2). It is important to note however that as many as 67 out of the 106 negative comments related to the low value of the badges.

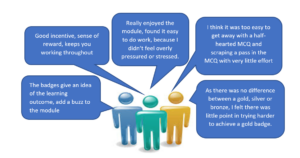

Figure 2 depicts information about positive topics included in students’ comments. 50 students liked the structure and focus that the badge system provided. Twenty-eight students found badges motivating and 24 valued feedback they received in the process. A number of students found the whole process enjoyable, rewarding and fun (See Figure 2). Figure 3 indicates the negative opinions. The most frequent topic of all was repeated 67 times as was related to the value of badges (See Figure 3). Figure 4 shows some comments made by students in the free comment box provided on the survey (See Figure 4).

Figure 2. Frequency of positive comment grouped by topic

Figure 3. Frequency of negative comment grouped by topic

Figure 4. Comments written by students

In summary, the majority of the students liked the way Digital Badges were used in the teaching of Psychiatry, however both groups (those that liked and those that dislike badges) criticized them for their low value of the overall assessment.

IV. DISCUSSION

Students met digital Badges piloted in the teaching of Psychiatry to Medical Students of our university originally with apprehension. The majority of the students had never heard of digital badges and have never earned a digital badge before this module. However, data from the study looking at students’ perception of the use of digital badges in medical education provided encouraging results.

A. Sense of Reward

Students found badges rewarding yet complained about the small value of the badges. This reflected our design intention in which we wanted to support and engage students rather than focus on extrinsic motivating factors such as sense of reward.

As mentioned above the badge was awarded for completion of weekly tasks, and the acquisition of a badge was functioning more as a method of feedback to students rather than for grading. However, a number of students complained about this, and reported a sense of frustration and a lack of motivation to try harder when the assessment value of the badge was so low.

Nevertheless, our design was supported by other studies. One such study concluded that achievement of badges could influence students’ behaviour even if they do not interfere with grading (Hakulinen & Auvinen, 2014). It seems that competitiveness was triggered in those who wanted to do better anyway.

We were pleased to see learners’ comments about reduced stress during the module. We wanted our award system to potentiate a sense of safety around assessment, giving participants freedom to learn from their mistakes without influencing their final grade. This is a well-recognized principle in gamification as a facilitator of students’ engagement (De Byl & Hooper, 2013).

In addition, our design was guided by the fact that the best use of badges was linked with the recognition of already occurred learning, therefore more viewed as an assessment tool, providing feedback and possibly self-reflection (Reid et al., 2015).

B. Impact on Structure, Assessment and Feedback

We were pleased to note that students in our study felt that digital badges provided direction and structure to their learning. This was also reflected in their comments: students mentioned how badges impacted on their study structure, helping them to focus attention on important aspects of the seminars. These findings are consistent with a study that reported that students who enjoyed badges, found them helpful in giving them the direction they needed to work in (Abramovich et al., 2013). These students also praised the alignment between badge topics and course content (Abramovich et al., 2013).

We were also hoping that badges designed, as part of an assessment that generates formative feedback would help students know if they are progressing enough to meet the requirements of their class (HASTAC n.d.). Based on responses to items 24, 18 and 19 it appeared that students benefited somewhat from the potential guidance and feedback provided by the digital badges system.

It is important to remember that students were asked about the badges at their review seminar and few days prior to their exams. This timing could have influenced their answers. For example, students’ opinion was divided on the statement that earning a badge gave them a sense that they have mastered the course content. Similarly, opinion was divided on whether badges increased students’ confidence that they could demonstrate their knowledge, nevertheless more students felt that they had an impact. It would be interesting to see if students’ responses had been different after their exams. We know gamification has already been described as a powerful strategy that can help achieve learning objectives by affecting the way students behave (Huang & Soman, 2013).

C. Impact on Motivation and Engagement

In our study, a majority of students responded that they worked harder in this module compared to non-gamified modules. Similarly, about 30% more students stated that they were more motivated to work harder through the module because they were earning digital badges. Interestingly when they were given space to provide free comment, many have noted that they did feel more motivated, and a few felt more engaged. Previous studies also reported that students were more likely to engage in the game-like tasks providing rapid feedback (Thamvichai & Supanakorn-Davila, 2012). In other publications students also considered gamified courses to be more motivating, interesting and easier to learn as compared to other courses (Barata et al., 2013), (Dicheva et al., 2015), (Hakulinen & Auvinen, 2014). It is suggested that badges are most valued by learners who are extrinsically motivated and value external validation (Foli et al., 2016).

D. Impact on Outcomes

We did not compare outcomes in overall performance in assessment between students before and after implementation of badges. Having considered this, we decided against it. We felt there were too many variables influencing students’ performance and it would be difficult to definitely attribute potential change to the implementation of digital badges.

E. View of Badges and Learner Type

The impact of an educational tool could also depend on characteristics of the student as a learner. It is reported that students with high expectation for learning and those that value their learning tasks may view the badge as validating if designed as a performance assessment (having impact on intrinsic motivation), but it may devalue their learning if it was viewed as an external reward (Reid et al., 2015). On the other hand, badges used as an assessment model can have a negative impact on students with low expectancy values (Reid et al., 2015). Another study concluded that engagement in the gamified classroom was dependent on students’ playfulness (De Byl & Hooper, 2013). In this study, we have not addressed the learner types and other such specifications of the individuals in our group of students.

In a systematic review of digital badges in health care education, it is mentioned that digital badges represent an innovative approach to learning and assessment and evidence in further education literature demonstrates that their use increases knowledge, retention and motivation to learn. However, they also report a lack of empirical research investigating digital badges within the health care education context (Noyes et al., 2020).

F. Limitations

Our study is limited by the lack of demographic data from all participants. This reduces the potential for comparison between genders and undergraduate vs postgraduate students. As mentioned above, we have not addressed learner characteristics and types (intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation, playfulness). The timing of the data collection (students completed questionnaires before their exams, rather than after) may also be limiting factors. It is also important to remember that this study allowed only for assessment of subjective impact (via students’ opinions and experience) of the badges on students learning and did not perform objective measures of students’ overall performance.

V. CONCLUSION

This study was performed at the start of the implementation of the digital badges in the module and at the time, it was the only module with elements of gamification throughout the whole undergraduate medical curriculum in our university. Like most changes in the assessment process, the students greeted this with a level of apprehension. It would be interesting to see if students’ opinion has evolved after a few years of digital badges being integrated in the module and when other modules are using them. Nevertheless, our data shows that our group of students felt, that they benefited from the learning structure provided by the digital badges. The online process of obtaining the badges enabled tutors to provide timely feedback and monitor students’ progress. In addition, our findings are in keeping with the literature in that engagement and motivation have been facilitated by introducing the digital badges and as such, they indicate that the use of digital badges is a promising tool in education.

The use of digital badges in Medical Education is only starting and would benefit from more research in its judicious integration in higher education curriculum as appropriate.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Edyta Truszkowska did the literature search, collected and analysed the data and gave feedback on methodology and questionaire developed and wrote paper.

Dr Yvonne Emmett designed the methodology and developed questionaire. She gave feedback on the data analysis and edited the writing of the paper.

Prof Allys Guerandel suggested the implementation of digital badges and research project. She gave feedback on data analysis and wrting of paper making revisions to same.

All three authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Our project has been exempted by ethics committee of our institution Human Research Ethics Committee – Sciences (Exemption number LS-E-17-56).

Data Availability

Data is available on reasonable request and data is shared in the institution.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge our institution psychiatry teaching team for their support in the implementation of the digital badges.

Funding

There are no sources of funding.

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

References

Abramovich, S. (2016). Understanding digital badges in higher education through assessment. On the Horizon, 24(1), 126-131. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-08-2015-0044

Abramovich, S., Schunn, C., & Higashi, R. M. (2013). Are badges useful in education? It depends upon the type of badge and expertise of learner. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(2), 217-232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9289-2

Armour-Thomas, E., & Gordon, E. (2013). Toward an Understanding of Assessment as a Dynamic Component of Pedagogy. https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/armour_thomas_gordon_understanding_assessment.pdf

Barata, G., Gama, S., Jorge, J., & Gonçalves, D. (2013, September). Engaging engineering students with gamification. In 2013 5th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications IEEE, UK (VS-GAMES) (pp. 1-8). https://doi.org/10.1109/VS-GAMES.2013.6624228

De Byl, P., & Hooper, J. (2013). Key attributes of engagement in a gamified learning environment. In ASCILITE-Australian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education Annual Conference, Australia (221-230). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/171232/

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011, September). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining” gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments (pp. 9-15). https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 75-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.18.3.75

Dowling-Hetherington, L., & Glowatz, M. (2017). The usefulness of digital badges in higher education: Exploring the student perspectives. Irish Journal of Academic Practice, 6(1), 1-28. https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/handle/10197/9691

Foli, K. J., Karagory, P., & Kirby, K. (2016). An exploratory study of undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of digital badges. Journal of Nursing Education, 55(11), 640-644. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20161011-06

Hakulinen, L., & Auvinen, T. (2014, April). The effect of gamification on students with different achievement goal orientations. In 2014 international conference on teaching and learning in computing and engineering, Malaysia (pp. 9-16). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/LaTiCE.2014.10

HASTAC. (n.d.). Digital Badges. http://www.hastac.org/digital-badges

Hensiek, S., DeKorver, B. K., Harwood, C. J., Fish, J., O’Shea, K., & Towns, M. (2017). Digital badges in science: A novel approach to the assessment of student learning. Journal of College Science Teaching, 46(3), 28. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/digital-badges-science-novel-approach-assessment/docview/1854234735/se-2

Huang, W. H. Y., & Soman, D. (2013). Gamification of education. Report Series: Behavioural Economics in Action, 29, 11 -12.

Johnson, L. J., & LaMontagne, M. J. (1993). Research methods using content analysis to examine the verbal or written communication of stakeholders within early intervention. Journal of Early Intervention, 17(1), 73-79.

Knapp, T. R. (1990). Treating ordinal scales as interval scales: An attempt to resolve the controversy. Nursing Research, 39(2), 121-123.

Mandernach, B. J. (2015). Assessment of student engagement in higher education: A synthesis of literature and assessment tools. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 12(2), 1-14.

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. Penguin.

Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in health sciences education, 15(5), 625-632.

Noyes, J. A., Welch, P. A., Johnson, J. W., & Carbonneau, K. J. (2020). A systematic review of digital badges in health care education Medical Education, 54(7), 600-615. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14060

Przybylski, A. K., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 154. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019440

Quesenberry, A. C., Hemmeter, M. L., & Ostrosky, M. M. (2011). Addressing challenging behaviors in Head Start: A closer look at program policies and procedures. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 30(4), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121410371985

Reid, A. J., Paster, D., & Abramovich, S. (2015). Digital Badges in undergraduate composition courses: effects on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Computers in Education, 2(4), 377-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-015-0042-1

Rolfe, I., & McPherson, J. (1995). Formative assessment: How am I doing? The Lancet, 345(8953), 837-839. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92968-1

Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human Computer Studies, 1(74), 14-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006

Sullivan, G. M., & Artino, A. R. (2013). Analyzing and interpreting data from likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5(4), 541-542 https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-5-4-18

Sundler, A. J., Lindberg, E., Nilssonn, C., & Palmer, L. (2019). Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nursing Open, 6(3), 733-739. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.275

Thamvichai, R., & Supanakorn-Davila, S. (2012). A pilot study: Motivating students to engage in programming using game-like instruction. Proceedings of Active Learning in Engineering Education. St Cloud University. https://nms.asee.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/47/2020/02/St_Cloud_2012_Conference_Proceedings.pdf#page=18

UCD Teaching and learning. (2017). UCD digital/open badges pilot 2016/2017. Implementation and evaluation report. UCD Teaching and Learning, 1-23. https://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/UCD%20Digital%20Badges%20Pilot%20Report.pdf

Yildirim, S., Kaban, A., Yildirim, G., & Celik, E. (2016). The effect of digital badges specialization level of the subject on the achievement, satisfaction and motivation levels of the students. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology- TOJET, 15(3), 169-182. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1106420

*Allys Guerandel

University College Dublin,

School of Medicine and Medical Sciences,

Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland D04V1W8.

00353868590063

Email: allys.guerandel@ucd.ie

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.