Defining undergraduate medical students’ physician identity: Learning from Indonesian experience

Submitted: 16 July 2023

Accepted: 21 December 2023

Published online: 2 April, TAPS 2024, 9(2), 18-27

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-2/OA3098

Natalia Puspadewi

Medical Education Unit, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction: Developing a professional identity involves understanding what it means to be a professional in a certain sociocultural context. Hence, defining the characteristics and/or attributes of a professional (ideal) physician is an important step in developing educational strategies that support professional identity formation. To date, there are still limited studies that explore undergraduate medical students’ professional identity. This study aimed to define the characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal physician from five first-year and three fourth-year undergraduate medical students.

Methods: Qualitative case studies were conducted with eight undergraduate medical students from a private Catholic medical school in Jakarta, Indonesia. The study findings were generated from participants’ in-depth interviews using in vivo coding and thematic analysis. Findings were triangulated with supporting evidence obtained from classroom observations and faculty interviews.

Results: First-year participants modeled their professional identities based on their memorable prior interactions with one or more physicians. They mainly cited humanistic attributes as a part of their professional identity. Fourth-year participants emphasised clinical competence and excellence as a major part of their professional identities, while maintaining humanistic and social responsibilities as supporting attributes. Several characteristics unique to Indonesian’s physician identity were ‘Pengayom’ and ‘Jiwa Sosial’.

Conclusion: Study participants defined their professional identities based on Indonesian societal perceptions of physicians, prior interactions with healthcare, and interactions with medical educators during formal and informal learning activities.

Keywords: Professional Identity Formation, Indonesia Undergraduate Medical Students, Physician Identity

Practice Highlights

- Defining the attributes of ideal physicians is important for developing strategies that support PI.

- Prior interactions with healthcare and formal/informal learning activities influence PI definition.

I. INTRODUCTION

Supporting the (trans)formation of a medical student’s identity, from a layperson to a professional, is an important process in preparing future physicians (Cruess et al., 2014; Goldie, 2012; Wald, 2015). This process includes professional identity formation (PIF) throughout their medical education continuum. Professional identity (PI) refers to how someone represents their profession’s characteristics, values, and attributes through thoughts, actions, and behaviors (Cruess et al., 2014; Gee, 2003; Luehmann, 2011). It is highly related to professionalism, which influences and shapes one’s identity in a professional context (Forouzadeh et al., 2018). The formation of PI involves developing one’s understanding of their professional roles, responsibilities, and expectations that are socio-culturally dependent (Siebert & Siebert, 2007). Therefore, the process of forming one’s PI also involves developing one’s cultural identity (Forouzadeh et al., 2018).

Studies on PI formation in medical education tend to focus on educational strategies that support PI formation during medical training (Adema et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2018; Cruess et al., 2015; Foster & Roberts, 2016). These studies provide insights on how to support PI formation without really addressing what needs to be taught to support medical students’ PI formation. Several theories on identity and PI formation suggest that one’s identity is formed through dialectical conversations that facilitate the acceptance, rejection, or modification of the profession’s characteristics and/or attributes into one’s core identity (Cruess et al., 2015; Gee, 2003; Siebert & Siebert, 2007; Stets & Burke, 2000). These characteristics and/or attributes are usually context-dependent (Cruess et al., 2014). Thus, defining and understanding what it means to be a professional physician in a certain socio-cultural context is as important as finding out how best to facilitate its formation in an educational setting (Wacquant, 2013).

Altruism and humanism are the two most cited values expected from a physician, along with integrity and accountability, honesty, and morality (Cruess et al., 2014; Edgar et al., 2020; Hall, 2021). Additionally, care providers, researchers, and teachers are some professional roles of physicians often mentioned in the literature (Ahmad et al., 2018; Branch & Frankel, 2016; Carlberg-Racich et al., 2018; Hatem & Halpin, 2019). Nevertheless, there might be other roles and characteristics that have yet to be fully elucidated, especially considering that the current literature on PI formation is mainly dominated by the Western representation of the medical profession.

This study aimed to describe the characteristics and/or attributes of ideal (professional) physicians in Indonesia as defined by undergraduate medical students. Undergraduate medical students are unique as they have limited opportunities to interact with real patients in a real workplace. Through this study, we hope to gain new insights from undergraduate medical students on what it means to be a professional physician.

II. METHODS

This was a qualitative phenomenology research using case studies design at a private Catholic medical school in Jakarta, Indonesia. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling method. Transitional phases in one’s life are often associated with identity renegotiation as they are exposed to changes in their roles, responsibilities, and expectations (Kay et al., 2019). Therefore, we sought to explore how Indonesian undergraduate medical students defined their professional identity at the beginning (first-year) and end (fourth-year) of their preclinical years. Ethical clearance was obtained from the school’s Research Ethics Committee prior to the study.

We set a quota of 5 participants for each study year (with a total of 10 study participants) to account for any possible socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religion, and gender variations. We recruited five first-year and five fourth-year preclinical students at the beginning of the study; however, two of the fourth-year participants dropped out during data collection; hence, only eight case studies constructed to depict the characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal Indonesian physician.

Each case study participant was interviewed twice using semi-structured interviews. The first interview was conducted at the beginning of school semester (August 2021) and the follow up interview was conducted one month after. The purpose of the first interview was to determined participants’ current understanding and views of what it meant to be a physician, while the second interview aimed to determine if there were any changes in their understanding or views and what precipitated the changes. Interview questions include: What kind of physician do you aspire to be? Was there one or more specific moment that prompted you to become a physician (if so, please describe it)? What characteristics and/or attributes should an ideal physician possess? Please explain. At the follow-up interviews, participants were asked to re-describe the characteristics and/or attributes of physicians that they aspired to be and what prompted the changes. Furthermore, participants were also asked to describe any specific learning moments that might influence their understanding of what it means to be a professional physician. Because of the COVID-19 physical distancing policy during the data collection phase, all data were obtained virtually or through electronic exchange via secured online platforms. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed in vivo using abductive thematic analysis with Atlas.Ti 8

In addition to from the interviews, we also conducted several classroom observations. We observed the first- and fourth-year’s large classroom lecture, problem-based learning, and skills laboratory session once, focusing on the teacher-student interactions and made note on how, if any, the faculty member facilitated students’ PI formation in the classroom. We also interviewed several faculty members who interacted with the participants in teaching capacity during the data collection phase. Faculty members were asked to describe what kind of physicians they wanted their students to be based on institutional values and their own beliefs about what constitutes an ideal physician. They were also asked to elaborate on their efforts to facilitate those characteristics and/or attributes in the formal and informal curriculum.

Data obtained from classroom observation and faculty interviews were used to triangulate the findings from the participants’ interviews. Permission was obtained from all related parties to record and use the interviews and classroom interactions in the data analysis. Individual case study reports were generated by combining the data obtained from interviews and field notes. These case study reports were then cross-analysed to find commonalities across the case studies to define the characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal physician that the participants aspired to be at their current stage of education.

III. RESULTS

The majority of participants were either Chinese or of Chinese descent. Five participants were Christian Protestants, one was a Buddhist, and two refused to disclose their ethnicity and religion. Note that the names used in these case studies are pseudonyms.

A. Case Study #1: Celine (First-year Student)

Celine, a female of Chinese-Betawi descent from West Java, was raised in a devout Christian-Protestant family. Being a physician was not her childhood aspiration. Initially, she thought physicians tended to be “rude, bossy, had too much pride, unwilling to listen to suggestions” (Celine, Interview 1, Line 42-43), which contradicted her personal values to being humble and helping others as a form of service and manifestation of her faith. Nevertheless, she developed a new appreciation toward physicians when she found out that there were physicians who gave back to the surrounding community by providing free healthcare (see Appendix No. 1).

Humility, and self-reflectiveness—which Celine called “openness to criticism” (Celine, Interview 1, Line 39-44) were the characteristics she deemed important as a physician. She believed that a physician should engage in social actions and put the patient first. Furthermore, a physician should consider the patient’s personal circumstances while providing individualised healthcare based on the patient’s needs. A good physician should also believe that their most important role is to provide credible health information and educate the community to improve their health and well-being. Good communication skills, including active listening, empathy, building trust, and the ability to break bad news, were essential in supporting this role (see Appendix No. 2).

B. Case Study #2: Dimitri (First-year Student)

Dimitri, a Christian-Protestant female of Chinese descent, was quite familiar with medicine and the medical profession as she was surrounded by people who either worked as or studied to become a physician. Additionally, she helped caring for her visually impaired sibling since she was young, which gave her opportunities to interact with various care providers as she accompanied her sibling for treatment. Being a physician naturally became her aspiration since childhood. Dimitri was appointed as a ‘Dokter Kecil’ (or, ‘little doctor’) in elementary school, assigned to provide first aid treatment to fellow students and promote health efforts conducted by the school. Before entering medical school, Dimitri’s grandfather fell critically ill; therefore, she helped her family to care for him in the hospital. There, she met a cardiologist whom she respected. She recalled that she appreciated the way this cardiologist relayed which information could be shared with her grandfather to keep his spirit up and which information should be disclosed to her family to prepare for the worst possible outcome. She mentioned that her grandfather looked “calm and comfortable” in his last days, which helped the family to accept his departure peacefully (Dimitri, Interview 1, Line 77-80).

Dimitri highlighted a physician’s ability to handle the distribution of information as an important part of her ideal physician identity (See Appendix No. 3). She believed that it was acceptable for a physician to keep certain information from the patient if that information could add unnecessary stress or cause them to stop following the treatment (Dimitri, Interview 1, Line 90-98). Regardless, the physician should disclose all information to the patient’s relatives as the patient’s decision-maker. Dimitri aspired to be a caring and compassionate physician with good communication skills who can be held accountable for her actions. Aside from being a care provider, Dimitri believed that a physician should take on a role as ‘Pengayom’ (protector). She believed that patients were in vulnerable positions due to their health issues, and therefore the physician was responsible for protecting them like a parent would when their child was sick. Implied in the Pengayom role was the leader whose responsibility was to make the best decision for the patient’s health and well-being (See Appendix No. 4).

C. Case Study #3: Faustine (First-year Student)

Faustine, a Christian-Protestant female of Chinese descent, was born and raised in a remote area in Riau province, in the southern part of Sumatra Island. Her interest in biology and life sciences prompted her to browse online videos related to healthcare since she was young. She tended to feel sad if the people closest to her were suffering and she could not do anything to help. She made up her mind to study medicine when one of her high school friends was forced to seek treatment abroad because of limited healthcare access in her region. Prior to this, her father was misdiagnosed with a malignant tumor, which caused tremendous distress for her family. These incidents drove her to be a physician who could provide good quality care, especially to those closest to her (See Appendix No. 5).

Faustine aspired to be an empathetic physician, taking patients’ mental or psychological state into consideration when planning for their treatment. She did not want to be a physician who focused on financial gain at the cost of the patient’s wellbeing. Being aware of her limitations in providing care and continuously updating her knowledge and skills were characteristics she hoped to develop once she became a physician (Faustine, Interview 1, Line 103-115). Faustine also mentioned that a physician was responsible for being a reliable source of information and improving community wellbeing through education (See Appendix No. 6).

D. Case Study #4: Jasmine (First-year Student)

Jasmine originated from Rembang, a small regency on the northeast coast of Central Java. Being a physician had always been her childhood aspiration because she loved helping people and interacting with others. Jasmine tended to her grandmother’s health needs during middle school. This event confirmed her passion and desire to serve others. Putting others’ needs above herself was a value instilled by her father since she was young. She wanted to be a physician who focused on social services, and was driven to help others sincerely without expecting anything in return.

As Jasmine mentioned, an ideal physician should be honest, disciplined, possess high ‘Jiwa Sosial’ (an attitude that shows concern to perform actions that are beneficial for humanity and social community), and always put the patient’s needs first (Jasmine, Interview 1, Line 50-53). Jasmine viewed her work as an extension of her faith, and she wanted to reflect Christian values, particularly the value of servitude, in her professional life (See Appendix No. 7-8).

E. Case Study #5: Rose (First-year Student)

Rose, a Christian-Protestant female of Chinese descent, was born and raised in Ambon city, Maluku province, Eastern Indonesia. She was the oldest child in her family. Rose became interested in medicine when her mother was diagnosed with a serious illness and could not receive appropriate treatment. She disclosed that her mother ignored the early signs and symptoms of her illness until her condition became so severe that she could not be treated fully. From this experience, Rose was motivated to become a physician so that she could take better care of her family (See Appendix No. 9).

Growing up, Rose heard several stories in which a patient did not receive appropriate healthcare due to their socioeconomic status. She aspired to be a competent and non-discriminative physician. Putting the patient’s needs first, being responsible, helpful, patient, disciplined, and continuously improving her knowledge and skills were the characteristics that she hoped to develop by the time she became a physician. Aside from being a care provider, Rose believed that a physician was responsible for improving the wellbeing of the community through education (See Appendix No. 10).

F. Case Study #6: *Anton (Fourth-year Student)

*Anton, a Christian-Protestant male of Chinese-descent, had an interest in biology since childhood. He was dissatisfied with Indonesian healthcare services, particularly with the healthcare workers’ communication skills when treating his father. This incident occurred when he was in middle school. *Anton observed a power imbalance between the patients and physicians, where the healthcare providers held more power over their patients. As a patient, he felt disadvantaged because he could not demand a better quality of care nor asked for a lower cost of the care he received (See Appendix No. 11). He described the two roles of physicians: as a healthcare provider and educator. As a healthcare provider, one should be able to help patients understand what is best for them while still respecting their autonomy. As educators, physicians have the responsibility to provide valid evidence-based information for patients.

For *Anton, an ideal physician’s fundamental values and skills included providing good quality care that kept the patients’ best interest, respecting patients’ autonomy, doing no harm, having all necessary medical competencies as listed in the Competence Standards of Indonesian Physician, the drive to learn for a lifetime, patience, humility, competence, and the ability to engage in interprofessional collaboration (See Appendix No. 12).

G. Case Study #7: *R (Fourth-year Student)

*R is a Chinese Buddhist female from Sintang, central Indonesia. *R wanted to pursue medicine because physician was portrayed as a noble profession in Indonesia and as a ‘role model’ in her family. She wanted to serve marginalised areas in East Indonesia after hearing about the poor health situation in those areas from several alumni and fellow students who served there in various capacities. This experience, along with her formal learning experiences, shaped her ideal physician image, which included being detail-oriented, confident, honest, thorough, and caring. She believed that physicians should be able to fulfill the roles and responsibilities of a healthcare provider, which required good proficiency in medical competencies, based on several fundamental values such as honesty, willingness to serve marginalised and under-served communities, and being sensitive to patients’ needs (See Appendix No. 13).

H. Case Study #8: *Anastasia (Fourth-year Student)

*Anastasia, who identified as a female, wanted to be a physician since elementary school. She did not have a specific motivation to enter a medical school when she first started. Nevertheless, there were several past experiences that she claimed to have influenced her image of ideal physicians. She mentioned feeling comfortable being examined by her pediatrician during her childhood. This made her consider the pediatrician as her role model. She also followed several healthcare professionals’ whom she admired on their social media accounts. She claimed that these figures influenced her to be selfless and put the patients’ needs above her own. She acknowledged the importance of entrepreneurial skills in aiding her goal of being selfless yet still able to make a living for herself. Her ideal physician image is someone who has good communication skills, clinical competence, and willingness to learn continuously. She identified healthcare provider as the essential role of a physician, who was responsible for providing physical and mental healthcare, as well as participating in preventive and promotive healthcare. She particularly considered female medical teachers at her school as her role models because she admired the way these figures divide their time and energy to work professionally–both as healthcare practitioners and teachers–and keeping up with their personal and family time. She aspired to be someone who could divide her focus like these figures once she graduated (See Appendix No. 14).

IV. CROSS-CASE ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Cross-case analysis revealed four major attributes of physician identity as defined by the first- and fourth-year participants (indicated by * behind their pseudonyms), including characteristics, values, roles and responsibilities, and skills. First-year participants drew their ideal image of a physician based on their interactions with one or more healthcare provider whom they met in their earlier lives. These interactions left a significant impression that further strengthened their motivation to study medicine and influenced the kind of values or other things that they held important and were willing to stand for as future physicians.

First-year participants mainly mentioned humanistic and altruistic values as the characteristics and/or attributes that define their professional identity. Honesty, humbleness/humility, accountability, patience, jiwa social, prioritising patients’ needs, empathy, care, and compassion are some of the characteristics mentioned by the first-year participants as characteristics of an ideal physician. These characteristics correspond to society’s expectations of professional physicians to put patient’s interest above all else, which is then further translated into medical professionalism and professional responsibilities (Alrumayyan et al., 2017; Elaine Saraiva Feitosa et al., 2019).

Different from their counterparts, fourth-year participants focused on clinical excellence and competence when citing the ideal characteristics and/or attributes of an ideal physician based on the national Competence Standards for Indonesian Physician. This indicates that fourth-year participants were aware of the standards as well as the ethical principles and physician’s code of conduct that were being enforced in Indonesia (See Appendix 15-16).

The way fourth-year participants described their physician identity aligned with the image of a professional physician painted by the school’s teaching faculty. According to interviews with several key faculty members, meeting the minimal standard of competence, being aware of one’s limitations, practicing evidence-based medicine, honesty, and discipline were some of the fundamental physician attributes/values/characteristics that they tried to instill in their students during education. These institutional values were most notably found in the way first-year participants described their physician identity during their second interview (See Appendix No. 17-18).

The attributes of Indonesian physicians mentioned by all case studies participants closely resemble China’s framework of professionalism, where they emphasise altruism, integrity and accountability, excellence, and religion/moral values (Al-Rumayyan et al., 2017). Possessing jiwa sosial (inherent sense of social responsibility, empathy, and engagement) and being a pengayom (mentor/guardian/protector) are two unique attributes that represent the Indonesian ideal physician.

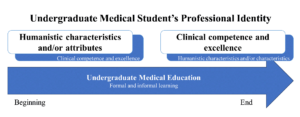

There were minimal overlaps between the first- and fourth-year participants’ ideal physician images. First-year participants placed humanism/altruism and social responsibility as the focal points of their physician identity, whereas fourth-year participants chose clinical excellence and competence to represent their physician identities. Social interactions play a major role in identity formation (Thomas et al., 2016). This may explain the shift in the first- and fourth-year participants’ definition of an ideal physician. First-year participants modeled their ideal physician identity after their memorable interactions with physicians who provided care for them or their family members. Positive past interactions with healthcare providers shaped the characteristics and/or attributes that participants aspired to be, whereas negative past interactions motivated them to develop the opposite of observed characteristics and/or attributes. Fourth-year participants also integrated the characteristics and/or attributes they identified from the formal and informal learning experiences with their evolving understanding of an ideal physician. In these case studies, fourth-year participants cited clinical competencies and excellence, as well as discipline and honesty—which were emphasised by the teachers during their undergraduate medical training—as the major characteristics and/or attributes that defined their physician identity.

Figure 1. Shift in First-Year and Fourth-Year Participants’ Definition of Physician Identity

The first year of the medical curriculum was indicated to be an important transition point that shaped all participants’ PI. In particular, all participants mentioned the school orientation as one of the learning moments that triggered their identity negotiation. Participants were introduced to the school’s expectations of them as medical students and future physicians. These expectations include the characteristics of self-regulated and life-long learners and those of professional physicians (See Appendix No. 19-20). For example, Jasmine “learned to be disciplined and responsible and she believed that the school orientation “helped shape [her] basic personality as a physician [who needs] to be disciplined and responsible [as well as] trustworthy.” (Jasmine, Interview 1, Line 115-118).

The shifts in participants’ physician identity definition indicated that participants engaged in a dialectical conversation that stimulated them to merge their core or personal identity with the institution’s perception of ideal physicians (“virtual/ideal identity) as interpreted in their curriculum, which was a part of one’s identity negotiation process (Gee, 2003). In the cross-case analysis, we found that participants’ reactions toward the values, characteristics, and attributes instilled by the faculty varied. For example, some participants saw the importance of being on time (‘discipline’) as well as being academically honest by avoiding plagiarism and cheating during exams (‘honesty’), which they accepted as a part of their physician identity. On the other hand, other participants struggled to understand the relevance of being on time and academically honest with their future physician roles or aspirations. This became a major challenge for these participants in incorporating those values into their physician identity. Nevertheless, no participants rejected any characteristics/attributes instilled by the institution even if those characteristics/attributes were distinctly different from their personal beliefs system (See Appendix No. 21-23).

Any new or contradictory characteristics or attributes to one’s core identity pose a professional dilemma that triggers an identity negotiation (Spencer et al., 1997). During this identity negotiation process, the study participants tried to merge their core identity, which was represented by their definition of the ideal physician that they aspired to be, either by accepting, rejecting, or integrating the new characteristics/attributes into their core identity (Cruess et al., 2015).

The acceptance of new characteristics/attributes into one’s physician identity will be easier if it is consistent with one’s core identity; however, it is still possible to instill characteristics/attributes that contradict one’s core identity if they are provided with the long-term benefit of accepting those characteristics/attributes (Guillemot et al., 2022). This underlined the importance of providing students with the relevancy of developing certain characteristics/attributes desired from a professional physician during their educational phase to support their PIF.

V. CONCLUSION

This case study found that first-year participants prioritised humanistic characteristics as the foreground of their professional identity, and medical professionalism as their background. Meanwhile, fourth-year participants developed a projected identity that embodied the general values of the medical profession and those promoted by their institution. The perceived image of ideal physicians as constructed by the Indonesian society’s ideal image of a physician, prior interactions with Indonesian physicians that influenced their decisions to study medicine, and interactions with the medical teachers during formal and informal learning activities influenced the way participants defined their professional identity.

Notes on Contributors

Natalia Puspadewi contributed to the work’s conception and design by developing the study proposal, protocols and instruments, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Further, Natalia also drafted and revised the manuscript and ensured that all aspects of the work were accountable, and followed all procedures to ensure data security and anonymity.

Ethical Approval

This study was a part of a doctoral dissertation. The University of Rochester acted as the author’s host institution, and Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, was the research site. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Rochester RSRB (a letter of exempt determination was obtained on July 8th, 2021 for Study ID 00006273) and the Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, School of Medicine and Health Sciences Ethics Committee (ethical clearance certificate No. 08/07/KEP-FKUAJ/2021).

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the Figshare repository

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23684235. The data were not translated into English to preserve the Indonesian sociocultural nuances captured in the interviews. All data were coded and analysed in vivo in Bahasa Indonesia before being translated into English for presentation in this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to those who have contributed to this study and article development: Dr. Rafaella Borasi as the head of the dissertation committee and advisor, Dr. Sarah Peyre as dissertation committee member, and Gracia Amanta, MD and Cristopher David, MD who helped with manuscript organisation and layouts.

Funding

This study was funded by the Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia and American Indonesian Cultural and Education Foundation.

Declaration of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Adema, M., Dolmans, D., Raat, J. a. N., Scheele, F., Jaarsma, D., & Helmich, E. (2019). Social interactions of clerks: The role of engagement, imagination, and alignment as sources for professional identity formation. Academic Medicine, 94(10), 1567. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002781

Ahmad, A., Yusoff, M. S. B., Mohammad, W. M. Z. W., & Nor, M. Z. M. (2018). Nurturing professional identity through a community based education program: Medical students experience. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 13(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.12.001

Alrumayyan, A., Van Mook, W. N. K. A., Magzoub, M., Al-Eraky, M. M., Ferwana, M., Khan, M. A., & Dolmans, D. (2017). Medical professionalism frameworks across non-Western cultures: A narrative overview. Medical Teacher, 39(sup1), S8–S14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1254740

Branch, W. T., & Frankel, R. M. (2016). Not all stories of professional identity formation are equal: An analysis of formation narratives of highly humanistic physicians. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(8), 1394–1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016 .03.018

Carlberg-Racich, S., Wagner, C. M. J., Alabduljabbar, S. A., Rivero, R., Hasnain, M., Sherer, R., & Linsk, N. L. (2018). Professional identity formation in HIV care: Development of clinician scholars in a longitudinal, mentored training program. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 38(3), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000214

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2014). Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Academic Medicine, 89(11), 1446-1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2015). A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialisation of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 718-725. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

Edgar, L., McLean, S., Hogan, S. O., Hamstra, S., & Holmboe, E. S. (2020). The milestones guidebook. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

Feitosa, E. S., Brilhante, A. V. M., De Melo Cunha, S., Sá, R. B., Nunes, R. R., Carneiro, M. A., De Sousa Araújo Santos, Z. M., & Catrib, A. M. F. (2019). Professionalism in the training of medical specialists: An integrative literature review. Revista Brasileira De Educação Médica, 43(1), 692–699. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v43suplemento1-20190143.ING

Forouzadeh, M., Kiani, M., & Bazmi, S. (2018). Professionalism and its role in the formation of medical professional identity. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 32(1), 765–768. https://doi.org/10.14196/mjiri.32.130

Foster, K., & Roberts, C. (2016). The heroic and the villainous: A qualitative study characterising the role models that shaped senior doctors’ professional identity. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0731-0

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment, 1(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1145/950566.950595

Goldie, J. (2012). The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Medical Teacher, 34(9), e641–e648. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476

Guillemot, S., Dyen, M., & Tamaro, A. (2022). Vital service captivity: Coping strategies and identity negotiation. Journal of Service Research, 25(1), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/10946705 211044838

Hall, C. (2021). Professional identity in nursing. In R. Ellis & E. Hogard (Eds.), Professional identity in the caring professions: Meaning, measurement and mastery. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781003025610

Hatem, D. S., & Halpin, T. (2019). Becoming doctors: Examining student narratives to understand the process of professional identity formation within a learning community. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519834546

Kay, D., Berry, A., & Coles, N. A. (2019). What experiences in medical school trigger professional identity development? Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 31(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1444487

Luehmann, A. (2011). The lens through which we looked. In A. Luehmann & R. Borasi (Eds.), Blogging as change: Transforming science & math education through new media literacies. Peter Lang Inc.

Siebert, D. C., & Siebert, C. F. (2007). Help seeking among helping professionals: A role identity perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432 .77.1.49

Spencer, M. B., Dupree, D., & Hartmann, T. (1997). A Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST): A self-organisation perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579497001454

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., & Mavor, K. (2016). Group interaction as the crucible of social identity formation: A glimpse at the foundations of social identities for collective action. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215612217

Wacquant, L. (2013). Homines in extremis: What fighting scholars teach us about habitus. Body & Society, 20(2), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X13501348

Wald, H. S. (2015). Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: Reflection, relationship, resilience. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 701. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.00000000000 00731

*Natalia Puspadewi

School of Medicine and Health Sciences,

Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia,

Jl. Pluit Selatan Raya No. 19, Penjaringan,

Jakarta Utara, 14440

Email: natalia.puspadewi@atmajaya.ac.id

Announcements

- Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.